JOHN ENGLISH

Fresno, California

Notable Woodworkers Since the 1600s by John English

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

© Linden Publishing Co. Inc.

Cover design by James Goold Book design by Clarity Designworks

ISBN: 9781610354097

135798642

Linden Publishing titles may be purchased in quantity at special discounts for educational, business, or promotional use. To inquire about discount pricing, please refer to the contact information below. For permission to use any portion of this book for academic purposes, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at www.copyright.com

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data on file.

The Woodworker’s Library ® Linden Publishing, Inc. 2006 S. Mary Fresno, CA 93721 www.lindenpub.com

SECTION

Woodworkers Born in the 1600s

SECTION 2

Woodworkers Born in the 1700s

SECTION 3

Woodworkers Born in the 1800s

Woodworkers

Foreword

A cold December afternoon. The light was fading, and I had finished the day’s deliveries—getting stuck in the snow not once, but twice. Now, with an hour to spare before the woodshop closed, I was given a chance as a young apprentice to plane parts for some custom furniture at one of the battered maple benches.

Erickson’s was a small, old-fashioned workshop. Nothing had changed since the 1950s, and its glory days had passed. I was the new kid, hired to drive the delivery truck, sweep the floor (there was no dust collection other than a broom), and occasionally help out in the shop. I learned mostly by sweeping very slowly while watching the two veteran cabinetmakers work.

The shop was known for high-quality walnut furniture, made one piece at a time. But it was all one style, French provincial, because that’s what the local upper crust had wanted in the ’50s. Now, some thirty years later, big cars with tail fins were out and boxy Japanese compacts were in. Planing, scraping, and sanding by hand were gone, replaced by random orbit sanders. But not at Erickson’s. We still used a World War II era 6-inch jointer, planed every piece by hand (“two passes only,” barked old man Erickson), scraped the tear-out, and sanded with a cork-backed block of wood.

Time stood still.

After a few years, I was promoted to be a journeyman cabinetmaker because one of the two vets had passed away and the other had retired. I loved the old ways of working wood, but eventually realized that there had to be a better solution, a change in method and style that would keep this failing business going.

There had to be a way to keep ahead of the design curve.

This book is about furnituremakers who did just that. Many of them were taught in the same way that I had learned. Respect tradition. Don’t make waves. But they rocked the boat, created new styles, introduced new forms, and adopted new technology.

They were pioneers.

As you read these pages and look back on the long evolution of furniture design, imagine these masters as apprentices, struggling to break free.

Work at their bench. Walk in their shoes.

And remember this: all that’s old was once new . . .

—Tom Caspar, editor emeritus, American Woodworker and Woodwork magazines, Minneapolis, March 2025

But it was in the later Middle Ages in Europe (1200 to 1500 AD), long after the Viking threat had faded and cities began to take root, that modern woodworking was really born. This was during and in the wake of the crusades when both ecclesiastical and political power grew more centralized, and taxation became widespread. The ensuing wealth gave rise to palaces, cathedrals and fortified castles across the continent. To build them, guilds of carpenters and joiners were formed and organized, and intensive training was instituted.

The guilds had their origins in the legacy of Charlemagne (Charles I, 747-814 AD), who was a man ahead of his time. This king of what is now essentially France surrounded himself with the most gifted and talented craftsmen, scholars and intellectuals in Europe. By standardizing measurements and currency, he made universal taxation and trade possible. His empire eventually extended through much of what we now call Western Europe, and the cultural and intellectual rebirth he inspired and fostered changed the face of the continent.

At the end of the Dark Ages, the Renaissance washed across Europe. Beginning in Italy in the 1300s it took two hundred years to finally crest on the beaches of Britain. With this ‘rebirth’ came a new architecture, executed in wood, metal, glass and stone by now flourishing guilds. Part of their philosophy was that artisans were required to travel for about three years after their formalized apprenticeship training ended. These ‘journeymen’ would work at various sites to hone their skills and learn regional techniques and methodology, before becoming accepted as masters of their trade. Among the effects of this practice was the spreading of skills over a larger geographical area, and the standardizing of various practices. Another was to raise the quality of work to the level found in pieces produced by the guild masters (hence the use of the word masterpieces), and to continually seek new standards of achievement.

Craft guilds gradually created monopolies in the various trades, and often extended their reach into the political arena. Indeed, some guilds became strong political entities themselves, taking control of the government of several major towns in what are now southern Germany, Belgium and Holland. They also began to specialize from general carpentry into specific guilds for carvers, luthiers, joiners, turners and gilders, who decorated wooden pieces with gold leaf.

As with many of the undertakings of men, increased wealth and power contributed to the decline of cooperation. While the guild masters filled

their coffers and restricted recruitment to maintain their monopolies, the skilled journeymen began falling away from the institution and opening their own shops.

By the early 1600s, many of these highly skilled woodworkers were working under their own names, and that is where our story begins. The seventeenth century was a busy time for woodworkers. This was a golden age of architecture, as fantastic new buildings appeared all around the world. These included such familiar structures as the Palace at Versailles which was designed by André Le Nôtre; the Piazza of St. Peter in the Vatican by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (beside the Basilica, which had been started back in 1506); the Blue Mosque of Sultan Ahmed in Istanbul by Sedefkar Mehmed Agha; Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London by Christopher Wren; the Taj Mahal in Agra by Shah Jahan; and the completion of the Louvre in Paris by Pierre Lescot. Some of these structures took more than a lifetime to complete. For example, Lescot died in 1578, when only the southwest wing of his vision had been realized and it would be almost a century before it was completed. What is notable here is that for the first time in history, the architects and designers on those projects achieved a level of notoriety that has outlasted that of the potentates and clerics who engaged them.

This was also a generative age for the British merchant navy, as the seeds of a new empire were being scattered along the eastern coasts of both American continents. Over the next four centuries, the British Empire would become the largest in history and by the outbreak of the first World War it would include fully one quarter of the planet’s entire population. So, it’s no surprise that British woodworkers, and in those early days the ships’ carpenters, would have a significant impact on the design of furniture and millwork, the species used and available, and the industrialization and mechanization of the trade.

While working with wood is by no means restricted to Europe and North America, the focus of this somewhat empirical survey of notable woodworkers has relied upon archival, photographic, and custodial resources that primarily document a Western tradition. It’s essential, however, to acknowledge the influence of other cultures such as Japan and Egypt on modern methodology, practices and design.

SECTION 1

Woodworkers Born in the 1600s

lives. During its course, England formed its first national army of full-time, professional soldiers.

We know something of the skill and genius of Thomas Simpson because of notes made in the diary of Samuel Pepys, who was Chief Secretary to the Admiralty in the wake of the war, and also through the survival of some of Simpson’s work. Pepys wrote prolifically over a ten-year period and has often been described as the greatest diarist in British history. His tome is over a million words, and he went into great detail about many different aspects of contemporary life and work. He had witnessed the execution of Charles I as a boy of fifteen, lived through the republican years under the dictatorship of Cromwell, found himself imprisoned in the Tower of London for a couple of months in 1679, and interviewed Charles II in later years.

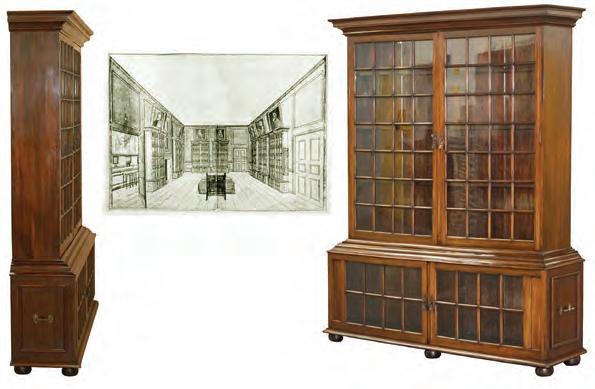

On July 23, 1666, Pepys records his involvement in the design of library cases that he was commissioning to have built: “… and then comes Sympson, the Joyner: and he and I with great pains contriving presses to put my books up in: they now growing numerous, and lying one upon another on my chairs…”

Simpson apparently worked fast, which suggests that he probably had apprentices although we have no record of that. On August 17, just three weeks after the design stage, Pepys wrote that he and his wife needed to hurry home to meet “with Simpson, the joyner… to put together the press he hath brought me for my books this day, which pleases me exceedingly”. This first large bookcase was delivered in pieces, where the base and upper were separated and the doors removed. This modular design, which included strategically located handles for hauling, would have been borrowed from shipboard practices, where confined spaces meant that moving large items required clever engineering that broke big projects into subassemblies.

The Simpson bookcases are unusual because of this mobility. Before this, the only evidence we have of library cases were built-ins. And the use of glass in the doors was another Simpson innovation, designed to allow his sponsor to view, access and organize the books within while keeping them dust-free. The doors are inset rather than overlay, which may be a nod to the need to save every inch of space on a ship, and the cases are supported in the corners and centers by lathe-turned bun feet. This non-maritime feature elevated the books to reduce the risk of deterioration from damp and rodents, which were both serious challenges in the Restoration era (a name that refers not to furniture, but rather to the restoration of the monarchy after England’s civil war).

Despite the fire, Pepys noted a year later (August 14, 1668) that he had hired Simpson to build and install a fireplace surround in his master bedroom. He recorded in his diary that this mantelpiece was expensive yet worth the price, which is a noble goal for any professional woodworker.

The original library cabinets built by Thomas Simpson for Samuel Pepys in 1666 (these are reproductions) now reside at the Pepys Library at Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge.

2. André Charles Boulle France, 1642-1732

The year that the Civil Wars began in England was also the year that France saw the birth of one of the most celebrated furniture artists of all time. André Charles Boulle was far more than a woodworker, but the core of his creative genius was a profound understanding of the nature and potential of this most malleable of natural materials. He raised the embellishment of wooden furniture to a high art that often involved applying a tortoiseshell coating and then inlaying that with options such as brass, pewter and precious metals.

A member of a Protestant family in what at the time was an intolerantly Catholic France, Boulle intentionally made it difficult to definitively say when, and even where he was born. Being Catholic and French were essential to advancement at court, and both his father and grandfather had

been cabinetmakers to the king. There is a suggestion that his grandfather had been born in Holland, but André claimed long lineage in Paris.

We do know that Boulle grew up in the Louvre palace (now the national art museum), which was home to a chosen few of the king’s artists, and that he apprenticed under his father.

The Sun King, Louis XIV, ascended to the throne a year after André Charles claims he was born. Louis ruled for more than 72 years, the longest reign of any European royal including Elizabeth II (70 years). He presided over and sponsored an era of unimaginable grandeur in the arts, and Boulle was among the king’s favorites. He was granted his own apartment in the Louvre under a royal charter that described him as a chaser, gilder and maker of marquetry. His official title was Premier ébéniste du Roi (first cabinetmaker, or literally ‘ebony worker’ to the king). His primary task was working on the embellishment of the fixtures and furniture of the Palace of Versailles, which included everything from free-standing pieces to inlaid floors, doors and wall panels.

A good example of the hundreds of pieces by André-Charles Boulle, this commode (or set of drawers) was completed in 1708 and delivered to a residence on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles called the Grand Trianon. It was a house where the king could distance himself from his court, and entertain his mistresses. Over the years, Boulle built at least five copies of this walnut piece that is veneered with ebony and includes marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell. It has gilt-bronze mounts, a verd antique (ancient green marble) top, and four extra spiral legs to support its weight.

Boulle collected great art and rare woods, and went broke several times doing so. His three workshops were filled with both, along with an endless procession of works in progress. Many great works by predecessors such as Raphael and Michelangelo were destroyed in a fire at his Louvre workshop in 1720.

He designed and built a vast array of furniture, from lamps and clocks to bedroom and dressing room pieces, all of which were

more sumptuous and lavish than anything else that was available to this, the most cosseted and spoiled court in history. He advanced the arts and techniques of inlay, marquetry, on-lay and gilding in ways that still startle practitioners today. His favorite woods were ebony and kingwood, which is a species of rosewood, and he used many other hard, dense tropical species in his inlays.

Boulle popularized the technique of sandwiching two layers of wood, one light and one dark, and then sawing or knifing a pattern through both. The result, when reassembled, was a superior inlay and a secondary one, which were named the primary and counterpart. He often used both on the same job, placing the better pattern in the more obvious area and the secondary on, perhaps, a side panel. He would also make matching cabinets with inverse patterns. To offset the tropical woods, he made extensive use of tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, stained horn and bone, brass and pewter. He ran his own foundry in later years, and worked in bronze. But first and foremost, André Charles Boulle was a cabinetmaker, carver and marquetry cutter.

3. Grinling Gibbons

England,

Holland, 1648-1721

Across the English Channel in the halls of Windsor Castle and Hampton Court Palace, another master craftsman was at work. The wood carver Grinling Gibbons was born in Rotterdam of English parents, and he is known for projects in St Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Hospital in Chelsea, and the universities at both Oxford and Cambridge among others.

Gibbons spent most of his life releasing art from blocks of limewood, which has nothing to do with the citrus fruit. It describes several species in the Tilia genus, and is also known as linden (Europe) and basswood (US). Gibbons had access to northern European winter lime, southern summer lime, and a hybrid of the two called Dutch lime. The wood is physically soft, fine-grained, and of a whitish-yellow hue. It is an exquisite species for carving, and can also be turned well. Its bark has been used for centuries to make rope, and there is not much drama in the transition between its sapwood and heartwood.

Gibbons would most probably have been known to Thomas Simpson (above) as he was in residence in Deptford, home to the Navy shipyard, at the

time of the Great Fire or within a year thereafter. He was accepted at Court and appointed by King Charles II as a master carver, and spent his creative years augmenting royal and public buildings with exquisite portrayals of floral and other highly decorative carvings. He is particularly noted for garlands, frames, and some requiem statues. His name is familiar still in England, as is that of one of his frequent employers, the architect Sir Christopher Wren. There are myriad examples of their genius all across the old city in its churches and great houses, and Gibbons’ talents also found their way to Florence and Modena. He worked in stone, marble and bronze, but his work in wood is what earned him an enduring reputation among those who appreciate great craft.

This intricate floral and fruit panel by Grinling Gibbons is from Petworth House in West Sussex, England. The manor was constructed in 1688 by Charles Seymour, the 6th Duke of Somerset, and for most of its existence it was a summer home for the Percy family, the earls of Northumberland. The carving includes a variety of vegetation including apples, wheat, pears, acorns and what appear to be peaches but are more likely plums, given that this was seventeenth century England. There is a classical acanthus leaf carving along the broad crown molding above. And Gibbons liked to include a little fauna in these panels too, such as the cockerel at left and the squirrel at right.

SECTION 3

Woodworkers Born in the 1800s

mahogany, his choice of species was often hardwoods from North America such as the heartwood of black walnut and cherry, with pine or yellow poplar as a secondary wood. One of his surviving pieces, a sideboard with masterfully carved hunting and fishing motifs, is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue, in Gallery 736. It was a combined gift from the Friends of the American Wing Fund, and the David Schwartz Foundation, Inc. According to The Met, “Roux displayed the prototype for this piece at the 1853 New York Crystal Palace Exhibition, prompting a commission to make a pair of related sideboards for the Astor family—this one and its mate, now at the Newark Museum”.

Roux grew with the times and sailed seamlessly through the Gothic to Renaissance, Rococo and Néo-grec as the market demanded. There’s an excellent example of his later work (also at The Met) which is an 1866 cabinet that is described as an “Italian Renaissance credenza, and its ornament, with delicate incising, gilt-metal mounts, rich marquetry panels, and porcelain plaques encircled by ormolu ribbons, is an eclectic combination of Louis XVI and classical motifs”.

It is worth noting that Roux, who had escaped the cataclysm of Paris, delivered this piece within a few months of the end of the American Civil War. However, his new city had only half the population of Paris (515,000 in 1850), and was in the midst of ordered growth that included the Erie Railroad, the new Central Park which had been started in 1853, horse-drawn

Another Roux piece, this is a Neo-Greco cabinet from 1866 that shows how he moved through styles and interpreted them. Typical of his time, Roux adapted European originals to American species and techniques. This is a rosewood, tulipwood, cherry, poplar and pine cabinet with roots that stretch from the Italian Renaissance to the court of Louis XVI. But it is smaller (just 53 -3/8” tall), and while highly ornate with extensive marquetry and porcelain panels, it somehow strives for simplicity.

omnibuses downtown, the first public telegraph office in America, the new Metropolitan Police Force, and the incorporation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) on April 13, 1870.

34. Charles Locke Eastlake England, 1836-1906

Many homes that Americans regard as Victorian architecture, which can be found in late nineteenth century residential areas across the continent, could perhaps be more accurately described as ‘Eastlake movement’. That’s because Charles Eastlake, the author of an 1868 book titled Hints on Household Taste

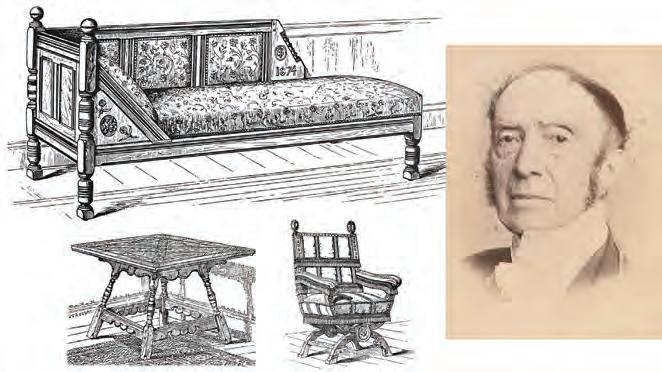

The Eastlake movement was a Victorian style developed by British architect Charles Eastlake, which became very popular in America. This plate shows the designer in a posed photograph taken by John & Charles Watkins in the 1860s. Also shown are three typical pieces, one of which includes the date 1874. The furniture was rudimentary but well-made, with simple lathe work and minor carving. Eastlake lived until 1906 and over time his style gained traction with American woodworkers whose shops were beginning to use new machinery. Thomas Edison’s New York generating station opened in 1882 and Nikola Tesla electrified the city of Buffalo, New York in 1896. Electric power tools soon followed, with the first drill being invented in 1895 in Germany by Emil Fein.

53. Lilly Reich

Germany, 1885-1947

A designer who worked primarily in metal and leather, Lilly Reich was an influential artist who collaborated with Mies van der Rohe (head of the Bauhaus during the 1930s) over several years. She is known for chair designs using tubular chromed steel that influenced many wood designs in the postWar years, and for her industrial bookcases in steel and wood.

54. Paul T. Frankl

Austria, America, 1887-1958

The most influential of the American modernism designers between the two World Wars, Paul Frankl was born into wealth in Austria and studied at the Polytechnic Institute in Berlin. After moving to New York, he opened a gallery on 48th Street in 1922 and two years later added a showroom on Madison Avenue. The woodshop built objects such as desks, bookcases and lamps in a simple, clean style that was inspired in part by the New York skyline. Over time, the pieces grew taller and thinner and began to resemble specific skyscrapers in the city. His bookcases were easy to move between apartments

In the 1920s, Paul Frankl brought a sense of humor and creativity to woodworking by building pieces in his unique Skyscraper Style that mirrored elements of the New York skyline. Shown here is a combination desk/bookcase that was photographed by Ohio resident Tim Evanson when it was part of a Jazz Age exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2017. The piece was built in 1928 and is built in California redwood with black lacquered accents and base trim.

as they would fit into small elevators and maneuver around bends in stairwells, so they quickly became popular in that most mobile of communities. As a result, he rebranded his galley as Skyscraper Furniture and almost overnight it leaped to the forefront of American modernism.

After a move to Los Angeles in 1934, where he opened a gallery on Rodeo Drive, he was discovered by the stars of Hollywood and his work became highly demanded. Frankl’s furniture was built in the woodshops of Brown & Salzman in California (aka Brown Saltman), and the Johnson Furniture Co. in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

55. Wharton Esherick

America, 1887-1970

Wharton Esherick was more than a woodworker. While he viewed himself simply as an artist, posterity describes him as a poet, painter, printmaker, and sculptor in wood. A Philadelphia boy, he trained at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art and the Academy of Fine Arts. He took up woodcarving in 1920 and created woodcuts to illustrate books, along with

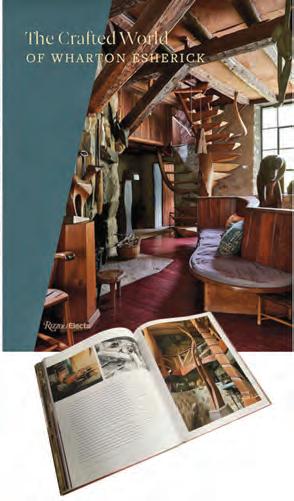

Poet, painter, printmaker, furniture builder and sculptor in wood, Wharton Esherick created a body of work that has over time become a national treasure. In 2024, the Wharton Esherick Museum in Malvern, Pennsylvania introduced a new book that was published by Rizzoli International Publications titles The Crafted World Of Wharton Esherick. It is a 224-page illustrated study with essays by Sarah Archer, Colin Fanning, Ann Glasscock, Holly Gore, and Emily Zilber. The images are by renowned architectural photographer Joshua McHugh. The Museum notes that Esherick is recognized as a leader of the studio furniture movement who saw himself as an artist, not a craftsman.

carving in three dimensions on furniture. Among those who influenced him was Henry David Thoreau, and indeed Esherick took Walden so literally that he and his wife settled in a rural spot with enough land to grow their own food, should his furniture fail to find a market. His first showing was at the Whitney in 1926, and over the next forty-four years he explored wood as an artistic material through A&C, expressionism, and eventually his own very recognizable, fluid, well-engineered and quite delicate style. Esherick melded an artistic vision with his woodshop skills to create something more than craft. His ‘sculptures’ have earned a place in numerous internationally celebrated museums and galleries, including the Wharton Esherick Museum that sits atop Valley Forge Mountain in his native Pennsylvania, and is a National Historic Landmark.

Perhaps the most resonant attribute of this accomplished woodworker was the inspiration and encouragement that he provided to other artisans and fine craftsmen. His furniture is lightweight, energetic, imaginative, and worthy of response—it’s difficult to merely glance at, and demands interaction. It led a revival of craft in the 1960s, and the modern museum that was once his home now celebrates that heritage.

56. Gerrit Rietveld

Holland, 1888-1964

Best known for his Red-Blue Chair, Gerrit Rietveld was a Dutch builder and designer who came to the fore in the early 1920s. His archetypal chair was built with standard dimensional lumber of the time (approximately 2x2s and 2x4s) along with flat panels, and it was intended for mass production.

Rietveld was much more than the chair. In 1918, at the end of the first World War, he became part of an art and design movement in Leiden known as De Stijl, which translates from the Dutch as ‘The Style’, and is also recognized as Neoplasticism. It was an expression of pure geometry that relied only on primary colors, in addition to black and white. The abstract painter Piet Mondrian was also part of the movement, and he had a significant influence on Rietveld. Gerrit turned Mondrian’s two-dimensional art into three-dimensional furniture, objects and even buildings, and his body of work in turn influenced modernists on both sides of the Atlantic in the years

between the wars. Other pieces of note were his Zig-Zag Chair, Crate pieces, and Press Room Chair.

Gerrit Rietveld, a leading light in the Dutch art and design movement that was known as De Stijl, encouraged woodworkers to think about basic materials in a different way. This chair, which resides at the Toledo Museum of Art, was built with flat panels and what was standard dimensional lumber at the time in Holland (between 1918 and 1923). It was intended for mass production as a covered porch chair, or perhaps in a reading nook. In addition to a low budget, it also featured geometric shapes and primary colors at a time when curves and French polishing were still very much in vogue.

57. Thomas C. Molesworth Holland, 1890-1977

The father of Cowboy Furniture, Tom Molesworth was a Kansan with a particular vision of the American West. After graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago, he went to work in a furniture factory but WWI interrupted his early career. He found himself in France in 1917, where he served as a corporal and watched mutineering French soldiers who were being slaughtered in the trench lines along the Western Front.

After the war he spent a little time working at a South Dakota bank, and then became the manager of a furniture retailer in nearby Billings, Montana. In 1931, he and his wife, LaVerne, moved to Cody, Wyoming and established the Shoshone Furniture Company, which he would run for the next thirty years.

In 1933, Molesworth was hired to create the furniture for Ranch A, a romantic getaway in a valley along a stream in eastern Wyoming. The owner, Moses Annenberg, owned several significant publications including the Philadelphia Enquirer. The ranch house is now owned by the state of Wyoming, and is operated as a retreat center. Molesworth created a total of 245 furnishings for the interior, most of which are now the property of the Wyoming State Museum. From there, his fame grew and he created interiors for many notable Western hotels and venues, including Dwight Eisenhower’s home in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and the Rockefeller ranch in Jackson, just south of Yellowstone.

Molesworth used logs, twigs, hides and horns in his woodshop, along with other ‘found’ materials, Native fabrics, and a lot of standard hardwoods. He blurred the lines between craft and art, as many leading woodworkers have done, and there was a major retrospective exhibition of his life’s work at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody twelve years after his death. It was titled “Interior West: The Craft and Style of Thomas Molesworth”.

From 1992 until 2007, Cody was home to the Western Design Conference, an annual show of furniture made in the American West. It has since moved to Jackson Hole, but even now the show still exudes a strong Molesworth influence in the furniture category, where the current work of a couple of dozen major studio furniture builders is exhibited each year.

Thomas Molesworth was a woodworking pioneer in a land of Pioneers. His Wyoming based Shoshone Furniture Company built upon a romantic core that included both Western and Native American cultural iconography. His materials were sourced locally for the most part—among them were standing dead timber along with antlers and hides from the high plains. Terry Winchell’s book, Molesworth, The Pioneer of Western Design, paints a concise and accurate picture of the contributions of this extraordinary woodworker to American interior design.

58. René Herbst

France,

1891-1982

One of the more important Modernists, René Herbst was another avantgarde designer who influenced the direction of the woodworking world without being part of it. He was a founding member of the Union des Artistes Modernes in Paris in 1929, and designed many pieces for the Aga Khan and his family. He made extensive use of metal such as chromed steel, along with leather and fabric. His stacking industrial chairs had metal frames and plywood seats, and he built desks and stools using hardwood elements.

Though he built hardwood furniture too, these stacking chairs by René Herbst were one of the earliest uses of plywood as a complementary material to steel in furniture design. The seats were attached with five screws, which allowed them to be easily replaced when worn or damaged. The seats were often used at outdoor events, so this was a solution for weathering.

59. Stephen and Lemuel Ward

America, 1895-1976 and 1896-1984

These two brothers in Maryland began carving decoys in their early twenties, when their father’s death left the family in poor circumstances. They supplemented a barbershop income by creating wooden carvings of birds that they observed on the Chesapeake Bay. The brothers were among the first to give their decoys realistic poses, such as turned heads, and while Steve carved,

Lem painted. They were awarded honorary doctorates in 1974 by Salisbury State College. In 1979, the governor of Maryland designated Lem as a ‘Living State Treasure’ and in 1983 he was awarded a Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts.

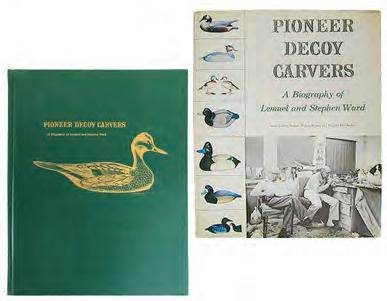

The subjects of a 1977 biography by Barry Berkey, the brothers Stephen and Lemuel Ward were renowned wood carvers who specialized in bird decoys. They pioneered the transition of wooden decoys from hunting accessories to a high art form that is now prized and collected. The Ward Foundation in Salisbury honors their memory and the work they did in the quiet backwater of Crisfield, two hours south on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay.

60. Roycroft America, 1897

Roycroft was more than a man: it was a business that became a movement and lasted beyond one generation. It brought a new aesthetic to Arts & Crafts, adding delicate aspects of Art Deco and Art Nouveau. Among the crafters at Roycroft were the sculptor Jerome Connor, and the artists William Denslow and Alexis Fournier. But the furniture is the most defining aspect of the movement, immediately recognizable even when its distinctive Orb trademark isn’t visible.

Founded by Elbert Hubbard, the Roycroft Campus was a community of craftsmen and artists in East Aurora, New York, that became an integral part of the Arts & Crafts movement. In 1894, Hubbard had traveled to England where he visited William Morris’s shop at Kelmscott. He returned to America and, in 1897, opened the Roycroft Print Shop next to his home. Two years later, he published A Message to Garcia, which was a short story about working habits that gained immense popularity, made him a household name,

and provided funds to explore new creative avenues. He built an expanded print shop and an inn, and while doing so discovered both woodworking and metalworking.

Elbert died on the Lusitania in 1915 when it was torpedoed by a German U-boat. His son, Elbert II, took over the Roycroft Campus and managed it well until the crash of 1929, when things began to go sour. In 1938, the business declared bankruptcy and the assets were sold. In 1986, it became a National Historic Landmark, and it is now a museum, school, retail outlet, restaurant, and home to several artist studios. Roycroft continues to be an inspiring influence for art furniture builders today.

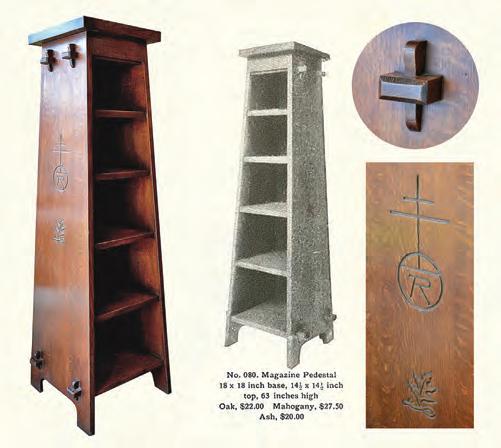

This iconic Roycroft bookcase (it was actually called a ‘magazine pedestal’) was one of the least complicated pieces to come out of the community’s shops in East Aurora, New York. That may explain why it has become one of the more popular projects in hobby shops ever since. The wedged tusk tenons offer fast and sturdy assembly, and the splayed legs lower the center of gravity so the piece is stable no matter how much it is loaded. Note the carved Roycroft logo in the side panel, the profiles of the wedges, and the small and inconspicuous drawer at the top. The image was supplied by Dave Rudd and Debbie Goldwein of Dalton’s American Decorative Arts in Syracuse, New York. At the time of writing, Rudd was the president of the Board at the Gustav Stickley House Foundation, and Goldwein was on the Board of Trustees of the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms in Morris Plains, New Jersey. Such experts in the field preserve the history of woodworking and make it possible for new generations to learn what their forebears have discovered, and thereby build upon the knowledge.

62. Charles H. Hayward

England,1898-1998

Beyond editing The Woodworker magazine in the U.K. from 1939 until 1967, Charles Hayward was a distinguished cabinetmaker in his own right, a gifted illustrator, and the author of more than thirty books on woodworking. He was a major figure in the popularization of woodworking as a hobby on both shores of the Atlantic, and a witness to the evolution from hand planes and push saws to motorized machinery.

Hayward was born in Pimlico, an upscale neighborhood in London which is home to the Tate gallery and many quiet streets of stately homes. After secondary school, he apprenticed at the Old Times Furniture Company which operated in Victoria Street from 1910 until 1950. It was an antique furniture dealership that, among other tasks, repaired and restored notable pieces. Still a teenager, his apprenticeship was interrupted by World War I when he served as a horse driver in the Royal Artillery. He opened his own woodshop in 1923, where he built cabinets and began drafting and illustrating. This was also the time when he started his long association with The Woodworker magazine, albeit then as a contributing writer and illustrator. Two years later, he submitted work to Handicrafts magazine, and in 1930 he became the editor of that journal. The ownership of The Woodworker took note, and in 1935 they offered him the position of associate editor. When war broke out in 1939, he replaced the editor and held that seat until his retirement in 1968. There are stories of candlelight print runs during the war. Hayward was particularly prolific during his years at the magazine, and wrote the majority of his books during that time. Among his titles are English Period Furniture (1936), Practical Veneering (1937), Charles Hayward’s Carpentry Book (1938), Tools for Woodwork (1946), Cabinet Making for Beginners (1947), The Woodworkers’ Pocketbook (1949), Woodwork Joints (1950), and The Complete Book of Woodwork (1955). Many of these were, and sometimes still are, used in classrooms around the world. Hayward taught at Shoreditch College in 1938-9.

Lost Art press (lostartpress.com) has published five volumes on the life and work of Charles Hayward including Tools, Techniques, Joinery, The Shop & Furniture, and Honest Labour.

63. Alma Siedhoff-Buscher

German, 1899-1944

Another name associated with the Bauhaus, Alma Buscher designed and built children’s furniture that was exceptionally popular. She was a minimalist who came to the public eye in her first year at the Bauhaus in 1923, when her nursery furniture was a big hit at an exhibition in the new Haus am Horn (this was a domestic home in Weimar, Germany that was designed by the architect Georg Muche for the show). Buscher’s room included a wardrobe, changing table, chest, cot/bed, linen cupboard, play cupboards with big blocks, a chair on castors, and a bench. The changing table becomes a writing desk when needed, and the dresser a puppet theater. One of her inspirations was Maria Montessori, an Italian physician who contributed much to early childhood education and living. And worth noting is that Buscher was the only woman to be granted access to the carpentry workshop at the decidedly misogynistic Bauhaus of the early 1920s. The influence of Buscher and other Bauhaus minimalists is still being felt in today’s cabinet making industry, where foils and laminates and water-based paints deliver the stark colors and hardware-free rectangles of many modern kitchens.

To modern woodworkers this Montessori-inspired children’s toy closet by Alma Siedhoff-Buscher may seem rudimentary and perhaps even bland, but in the early 1920s it represented a new direction in multi-functionalism.

A product of the Bauhaus, Buscher was a minimalist who made furniture that served more than one use. A changing table might become a writing desk when needed, or a dresser a puppet theater. She is also notable as the only female who was allowed to use the woodshop at the Bauhaus during her time there.

64. Mart Stam

Holland, 1899-1986

Born in the last months of the nineteenth century, Mart Stam was an architect and furniture designer who trained as a joiner and became an important pioneer of modern furniture design. Hand-on woodshop experience gave him both practical and intellectual advantages over pure theorists. He turned down an opportunity to join the Bauhaus in 1926, the same year he developed his cantilever chair that lacks rear legs. That went into production by the German manufacturer Thonet as a tubular steel frame and a bent plywood seat that is still copied today.

In 1928, Stam became an honorary member of the Bauhaus, and taught on the Dessau campus from 1928 to 1930. In 1939 he became the director of the Amsterdam School of Artistic Crafts, and in 1950 director of the Higher Institute of Applied Arts in Berlin-Weissensee. He spent most of the next two decades in Amsterdam, and retired to Switzerland in 1977.

The German furniture manufacturer Thonet GmbH has been making its S 40 garden chair since 1935. The distinctive design has a tubular steel frame and wooden slats. The latest version uses Iroko, an African wood with high density and weather resistance that’s similar to teak in appearance. The chair was designed by Mart Stam during the Bauhaus period, and it was on the cusp of modernism in furniture design. A similar chair was developed by Stam’s fellow Bauhaus teacher Marcel Breuer, and the two ended up in court in 1932 where it was decided that Stam was not only the designer, but also the inventor of the fundamental concept of the cantilevered tubular chair. The Bauhaus was a design school founded by Walter Gropius in 1919 that combined art and technology, and was the instigator of many changes in woodworking and furniture building. Stam, who was trained in a woodshop in traditional joinery, helped teach a generation of skilled woodworkers at the Bauhaus and later at advanced technical schools in both Amsterdam and Berlin.

SECTION 4

Woodworkers Born after 1900

A New Kind of Woodworking

Woodworkers who were born in the twentieth century saw a number of fundamental changes in the woodshop. Starting their careers between the wars, the earliest of this group were the first artisans who had wide access to relatively inexpensive small machines such as table saws, band saws, shapers and a huge array of portable power tools. They were the first to see the emergence of global styles and mass markets in furniture, and the first to watch millions of hobbyists emerge from other trades and professions to delve into woodworking as something other than a career.

These ‘modern’ woodworkers were also the beneficiaries of seismic changes in materials during their lifetimes, moving from shellac and hide glue to sprayed plastic-based coatings and aliphatic resin adhesives; hand-cut boards to hardwood-veneered plywood, new cores and laminates; and clever joinery techniques such as biscuits and mechanical fasteners. All aspects of the trade could now be automated to any degree, and while some tasks were still performed with hand tools, the emergence of power tools and, later on, CNC controls opened floodgates of creativity and an egalitarian approach that turned cabinet and furniture building into inclusive, rather than exclusive crafts.

One key ingredient in this new force was the mass dissemination of knowledge. It was heralded by the publication of hobbyist and semi-professional magazines, along with how-to books. Other forms of media came to bear as this generation matured, including woodworking shows on television and eventually online with the birth of YouTube™. But the early printed magazines were crucial as they appealed directly to a nascent middle class that, for the first time in history, had the financial resources and leisure time to partake in woodworking as a hobby. A byproduct of this was the advent of professional woodshop writers, photographers, graphic artists and joinery experts who guided and encouraged their followers. Among the first was shop teacher Charles Wheeler, who published a book in 1924 that included a chapter on power tools. And in 1930, the premier edition of Popular Homecraft magazine claimed that there were more than seventy thousand home workshops in America that had at least one major power tool. The magazine was introduced by General Publishing Co. in Chicago, and saw sound growth before and after the war years. (A 1937 issue can be viewed online as a flip-book at archive.org/details/phc-193710.)

the U.K. Today, the Edward Barnsley Workshop (barnsley-furniture.co.uk) continues to design and build fine furniture in the original woodshop in Froxfield, Hampshire.

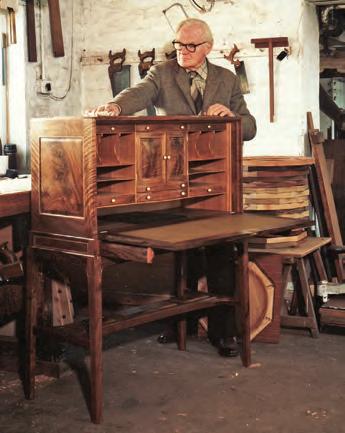

Although he is not very wellknown in North America, Edward Barnsley is revered in the U.K. as one of the great educators and innovators in this field. In a career that began in 1923 after he completed his training, he created a new woodworking style over time that built on his impeccable A&C heritage but transcended the simplicity of Morris and the work of the notable woodworkers in his own family. His pieces exhibit the highest level of craft, with delicate inlays and sensitive geometry, and an acute understanding of grain and color. His career perhaps climaxed with the Jubilee Cabinet, a writing desk that was built in 1977 to coincide with the twenty-fifth anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. It was exhibited in London at a masterworks exhibition hosted by the Crafts Advisory Committee, and it is an exquisite example of fine furniture building. Serious woodworkers and admirers of skilled artisanship may indulge their curiosities with an online visit to barnsley-furniture.co.uk, or perhaps attend classes at the woodshop.

66. Paul László Hungary, America, 1900-1993

Although the spelling was simplified to Laszlo in his California years, Paul László never forgot his roots as a Jewish Hungarian. His parents and two of his sisters were murdered in the Holocaust.

After graduating from college in Vienna, he became an admired interior designer in Stuttgart at a time that coincided with the emergence of the Nazi movement. In 1936 he managed to get passage on a liner to New York, and

continued on from there to Beverly Hills in California. His reputation had preceded him, so there was no shortage of commissions.

During his years in Germany, he made the acquaintance of Salvador Dalí, for whom he designed a unique console table. Ironically, some of his work also found its way to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest, near Berchtesgaden.

After the war, in 1948, he joined the Herman Miller Company where he worked with Charles Eames and others to create a new American modernism style. It is still going strong with twenty retail stores nationwide, but Laszlo was too much of an individualist and soon returned to his own workshop on Rodeo Drive. From there he designed interiors for some of his adopted homeland’s greatest retail names including Saks Fifth Avenue and Hudson’s Bay, plus casinos in Las Vegas.

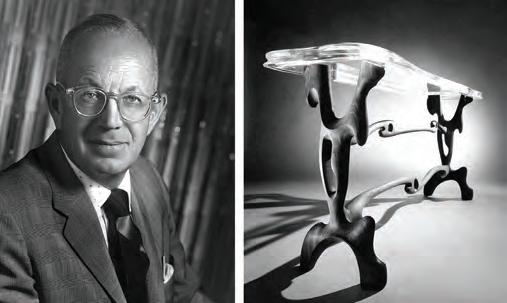

The sculpted console table shown here was designed by Paul László as a tribute to Salvador Dalí, whom he knew in Germany between the wars. The woodworker and

designer was a Hungarian Jew who fled the Nazis in 1936 and ended up in Beverly Hills. He had served with the Hungarian military in World War I and enlisted in the U.S. Army during World War II but was not posted overseas. He worked for Herman Miller after the war and was in part responsible, in collaboration with Charles Eames, for the inception of American modernism. His work can be seen in the homes of Hollywood stars, the casinos of Las Vegas, and some of the most exclusive retail outlets in California. The 1953 console table was probably inspired by Dalí’s 1931 painting, The Persistence of Memory, where three clocks are melting in the foreground and the cliffs of Dalí’s Spanish Catalan homeland are shown in the distance.

68. Greta Hopkinson

England, 1901-1993

The daughter of an English marine engineer and a Swedish songstress, Greta Hopkinson (née Stromeyer) grew up in Manchester and graduated from Cambridge. She sculpted in wood, and had some notable exhibitions including the Southampton Art Gallery exhibition Dead Wood Alive, in 1977. In the early 1990s, her work was exhibited in the New Forest in conjunction with pieces by Royal Academy painter Barry Peckham. She used a lot of found wood that was harvested from the New Forest, and often incorporated it in its naturally sculpted form.

69. Arne Jacobsen

Denmark, 1902-1971

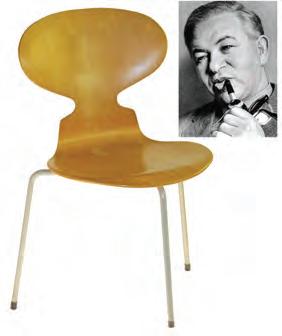

Primarily known for simple chair designs, Arne Jacobsen is especially remembered for the Ant Chair, which was designed in 1952 for use in the cafeteria of the Danish pharmaceutical manufacturer Novo Nordisk. The seat was bent plywood created on a form, and it is important to the history of woodworking because Jacobsen was a pioneer in using wood as a fluid material that didn’t need to remain in the plane in which it was harvested.

As every chairmaker knows, three feet rather than four will stop wobble. The trick is to build a stable piece that can be adequately supported by only three legs. Arne Jacobsen’s Ant Chair may be the ultimate answer. Its formed plywood seat and back carry the user in a comfortable pose that offers the stability of two rear legs. More than five million of these chairs have sold worldwide.

70. Marcel Breuer

Hungary, Germany, England, America, 1902-1981

After leaving Hungary at eighteen, Marcel Breuer soon found himself at the Bauhaus where his natural talents eventually turned into a teaching position. He built wooden furniture at first and also worked with tubular steel. Breuer developed several metal and fabric chairs, among the more noted being the Wassily. A Jew by birth, he relocated to London in 1935 after the Nazis closed the Bauhaus, and among other commissions while in the U.K., he designed the Isokon Long Chair for a property company of that name. The bent plywood chaise longue is still regarded as one of the more important inter-War designs, as it used bent plywood in the tradition of Alvar Aalto (61, above). Breuer modeled the chair on an aluminum version he had completed three years prior to executing the British design.

In 1937, he moved to the U.S. and formed a partnership with architect Walter Gropius, who had been appointed chairperson of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. In 1946, Breuer moved to New York and opened a design practice that over the ensuing decades created buildings such as UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris; the Whitney Museum of American Art; and the less popular headquarters of HUD in Washington, D.C.

Marcel Breuer’s elegant Isokon chaise lounge was created between 1935 after he had fled Germany when the Nazis shut down the Bauhaus, and 1937 when he arrived in the United States. The chair measures 31-3/4” x 24” x 51” and is an excellent early example of bending laminated birch ply in forms. Note the subtle arch in the legs that reduces two long skids to four pressure points akin to feet. The arms are also laid up in layers, and the headrest offers support without a pillow. Breuer became an important U.S. designer and architect, and Isokon Plus is a British manufacturer of wooden furniture that still builds his designs.

71. Charlotte Perriand

France, 1903-1999

After studying in Paris and exhibiting successfully at several important venues in her early twenties, Charlotte Perriand began a ten-year collaboration in 1927 with Pierre Jeanneret (see 67, above), and his cousin the architect Le Corbusier. That was also the year she exhibited a violet wood (purpleheart) cabinet at the Salon of Decorative Arts, and the Ospite Extending Table in lacquered wood.

Just ahead of the German occupation of France, Perriand moved to Japan in 1940 and remained there for two years through the outbreak of war with the United States. She had a connection in Tokyo through Le Corbusier’s firm, in the personage of an architect named Junzo Sakakura, and she became an advisor to the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. In 1942 she moved to French Indochina (now Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and

Born in 1903, Charlotte Perriand was a major connection between Western and Japanese woodworkers for much of the twentieth century. The photograph here shows several of her pieces at an exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris that helped launch the book Charlotte Perriand et Le Japon by Jacques Barsac in 2009 (Norma Editions). This was his second book on the life of Perriand, who was invited in 1940 by the Japanese government to guide the country’s industrial art production. She “discovered a way of thinking, a way of life and an architecture that conformed to the modernist precepts she had defended with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret”. Over the ensuing decades she organized exhibitions in Japan, published work, built furniture, and created a bridge between the two cultures. “Of all the Westerners who worked in Japan,” noted designer Sôri Yanagi, “she is probably the one who had the greatest influence on the world of Japanese design.”