BROWNSVILLE RISING

This project, “Brownsville Rising,” is an elevated pathway that creates connections in a troubled area of New York City. The pathway connects the subway stations with ramps through five anchor buildings that are located in strategic corners of the historic neighborhood to expedite travel and opportunity for residents. The ramps cut through the buildings with cantilevers that pinch the building to separate the programmatic possibilities.

This efficient elevated network of pathways and mass transportation through the anchor buildings will bring Brownsville residents into the city and bring the amenities of the city into Brownsville. Located along the elevated pathways are day care centers, startup incubators, community kitchens and gardens, and other public amenities.

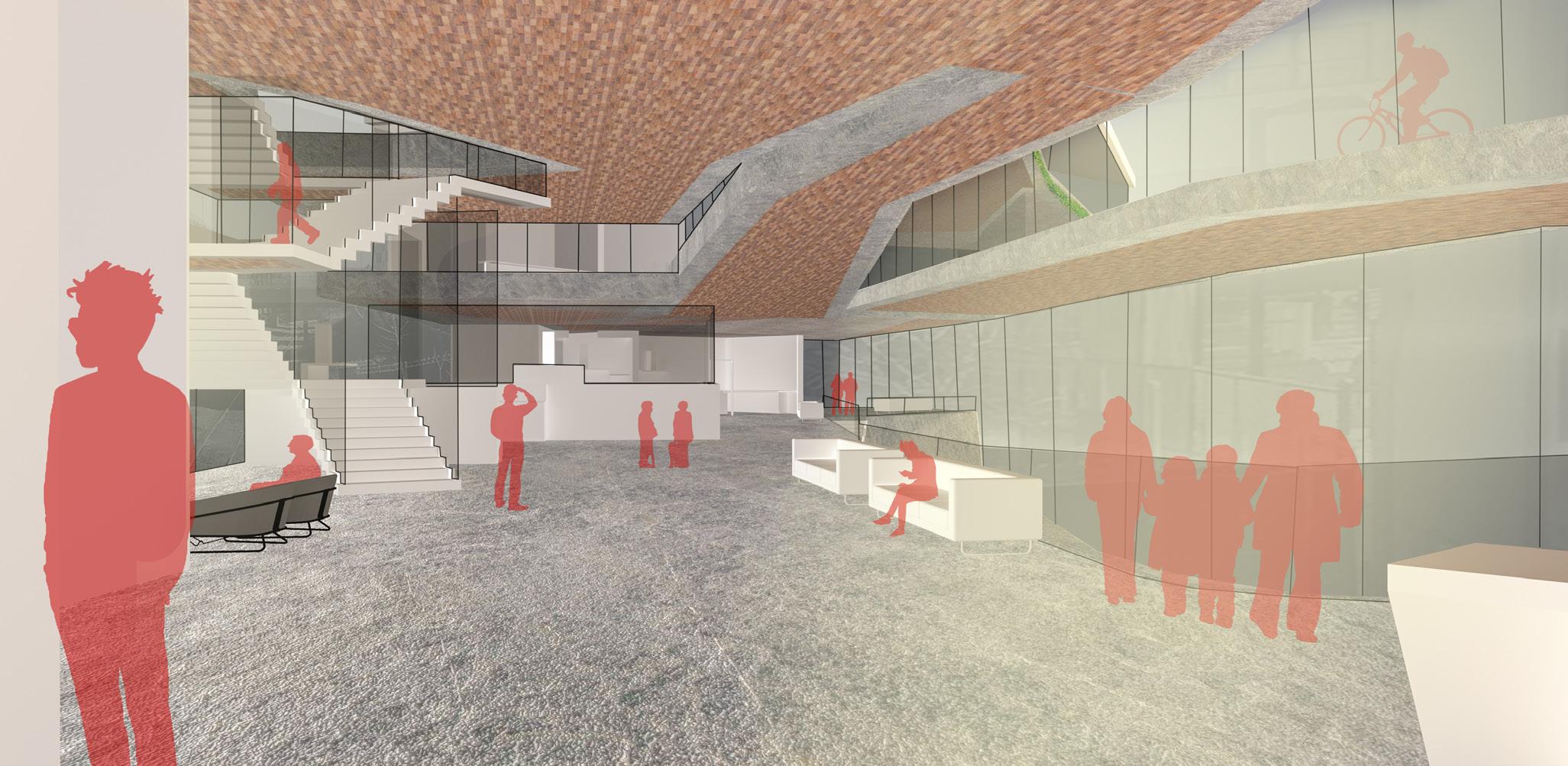

Brownsville is an iconic African American neighborhood with a history of food and music and activism and the largest concentration of public housing in New York City. The Brownsville Rising project circulates residents back into their neighborhood and into New York City. This town is filled with empty green lots with potential to provide usable space for its members. There are several community programs in place that fill capacity and require space for other community functions as well. The anchor buildings are strategically placed near these existing community programs to act partially as extra space for those that utilize those programs. By looking at the most complex anchor building location that must deal with intersecting trains at the Atlantic Avenue L stop, both above grade and below grade, many resolutions must be made for a better experience of the site. The anchor building provides safe passage from the elevated train to the street level and pulls people into a station with an experience like no other. Once a modern building is inserted into the site, the perception of an industrial overlooked space is altered to one that creates beautiful gathering spaces for community members. It is the introduction to the city, as a representation of how this is a community that supports one another and works together to strive forward.

The project promotes the social interaction and collaboration of the members of Brownsville and additionally provides them an economic ignitor with the startup incubator at the anchors. It also creates a connection between north and south so that people can use the ramps as a means of travelling at night safely and having a view of their growing neighborhood. The first anchor acts as an example of the other four buildings as well as an example for the adjacent neighborhood thats are similarly historically rich in culture yet impoverished economically. This proposal is unique as it looks at areas that lack certain services for various reasons, largely due to economies, which can be seen as trigger for growth. Architecture can facilitate this growth as it can provide a space for community members to use in a way that best fits their needs.

Brownsville, the oldest African-American neighborhood in Brooklyn, is on the southeastern side of the borough. This neighborhood is on the lower income bracket and has not been growing in a way that helps the community. Community members and city planners have been continually speaking about what the neighborhood needs and are attempting to address it. Many people recognize that this is a site that requires an intervention to this degree to promote the welfare of the community members.

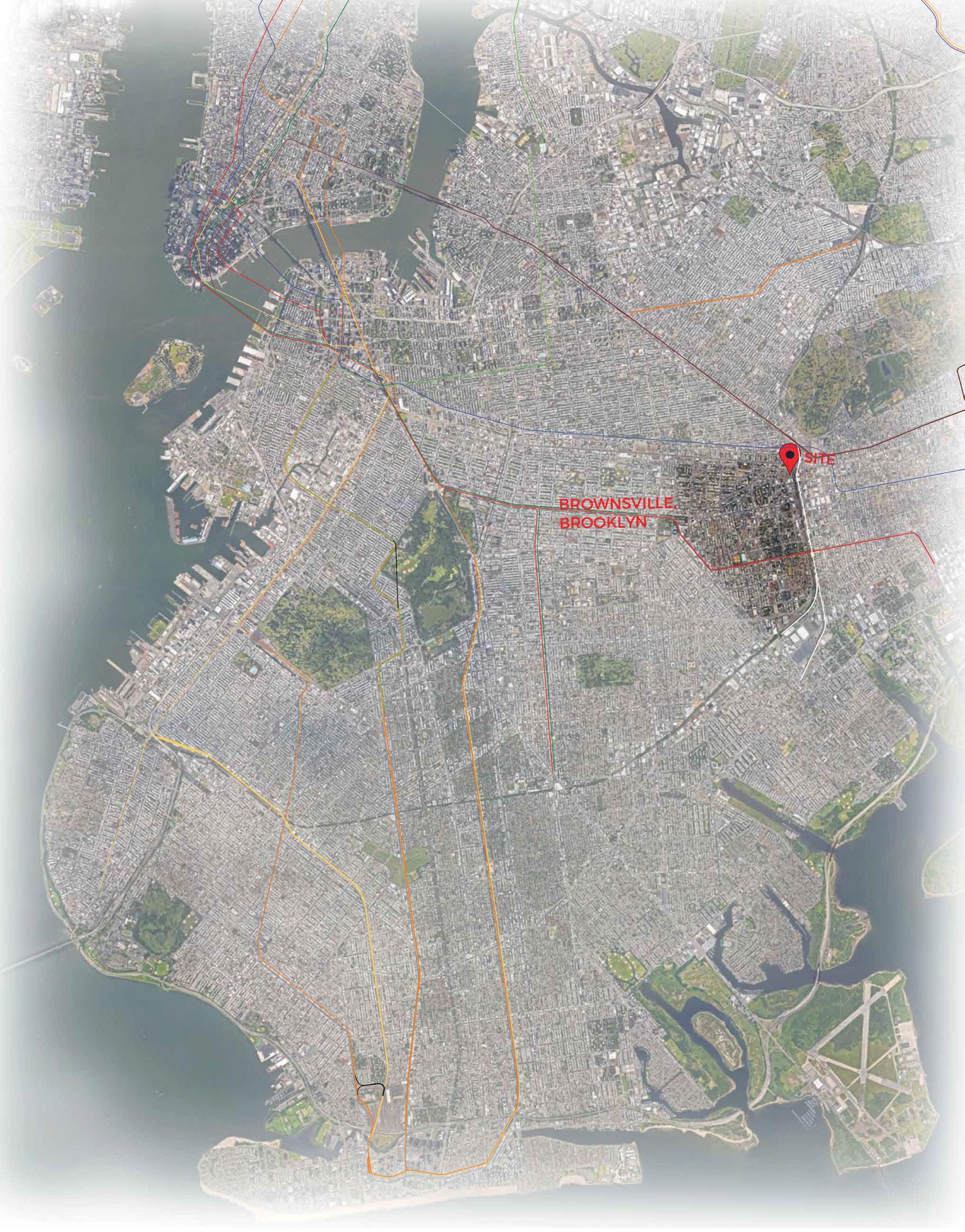

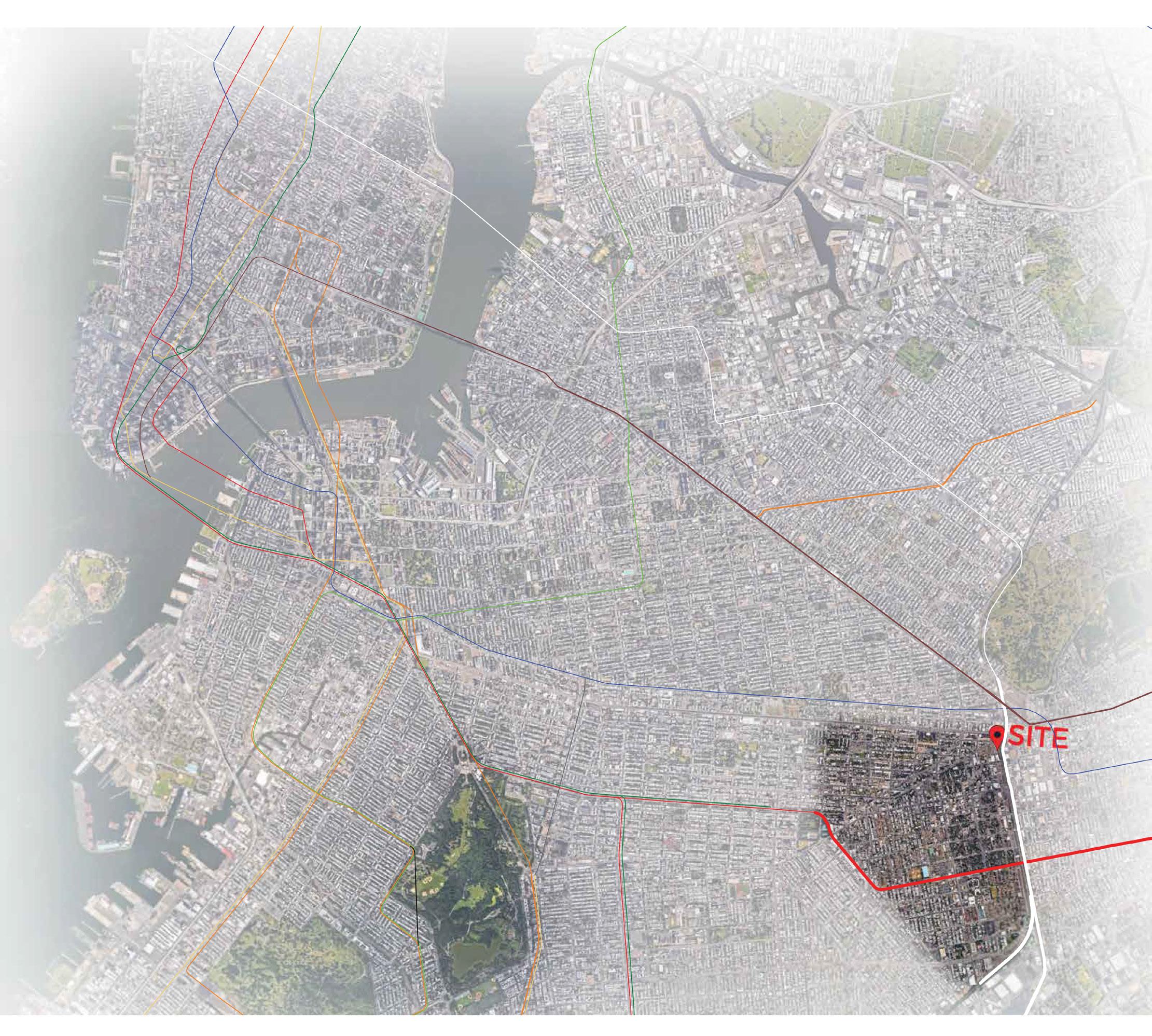

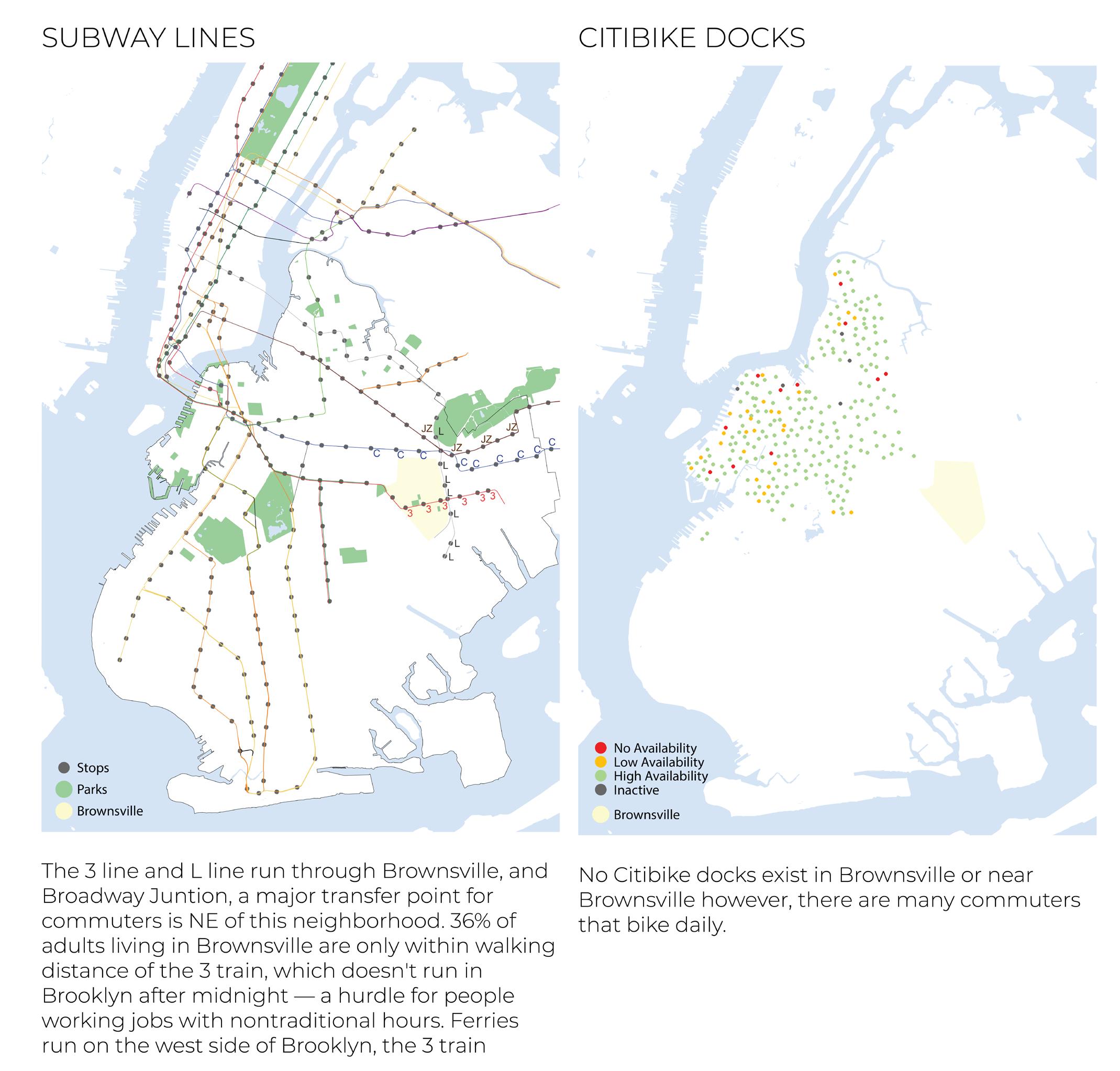

In order to see the relationship of this city to the surrounding areas of the larger city, we must begin with a view of the Brooklyn borough. Subway lines are mapped so that we can see how major public transit intersects at Brownsville. This neighborhood is east of Prospect Park, close to the edge of Brooklyn and Queens, with the 3 line and L line running through it. As we zoom in we can get closer to the site at which begins the Brownsville Rising proposal.

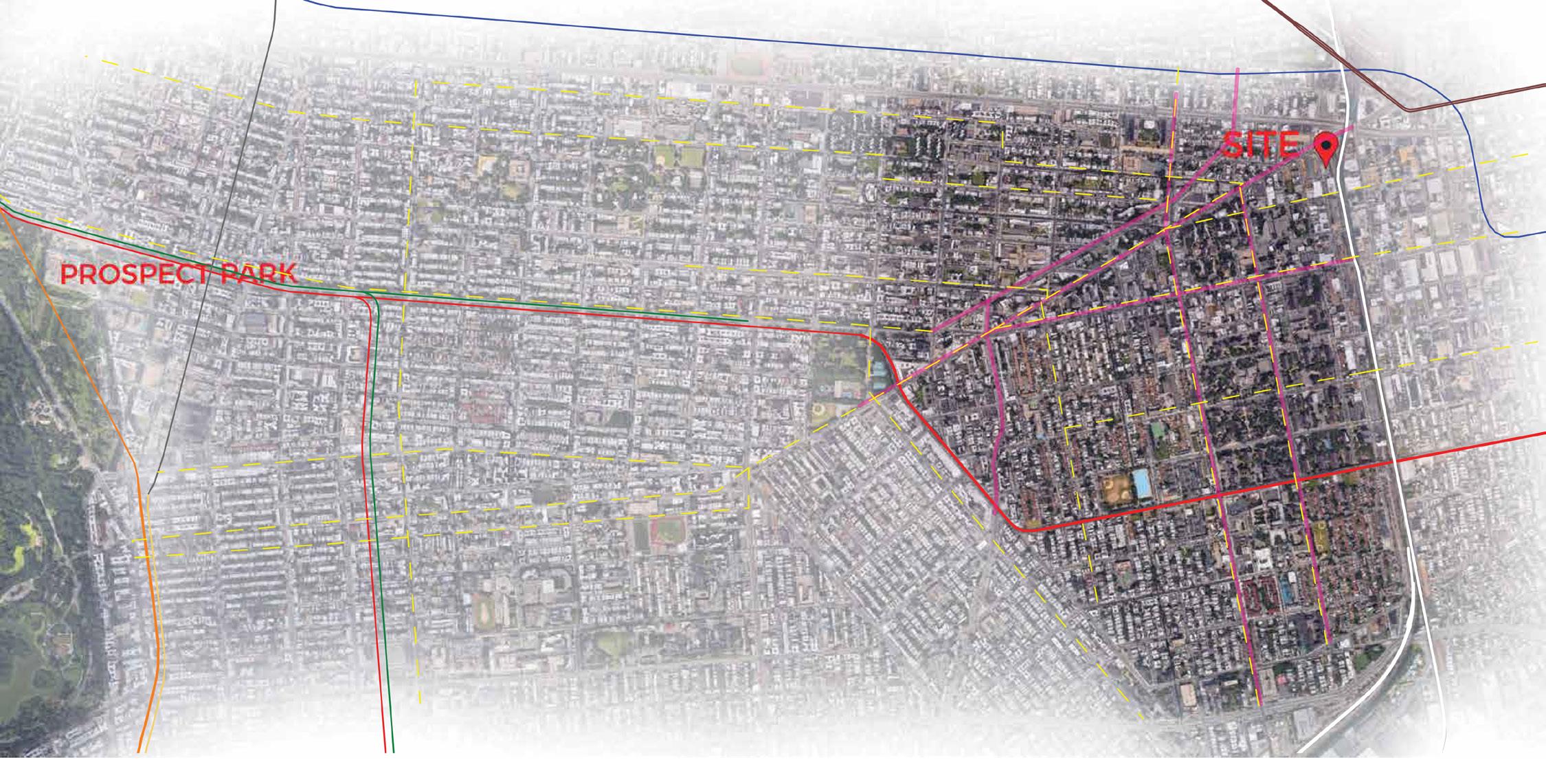

As we zoom in further we can begin to incorporate the distinguishing features of major roads and bike lanes to further understand Brownsville. Near the neighborhood is the AC and JZ lines, and a single stop away is Broadway Junction, a major station in this area.

There are a few bike lanes distributed through Brownsville, primarily along major roads. None of these bike lanes are protected bike lanes, meaning they are not seperated from car lanes with a 3 foot buffer, a safer lane for bikes. Rather these are bike lanes and shared bike routes.

Protected Bike Path

Protected Bike Path

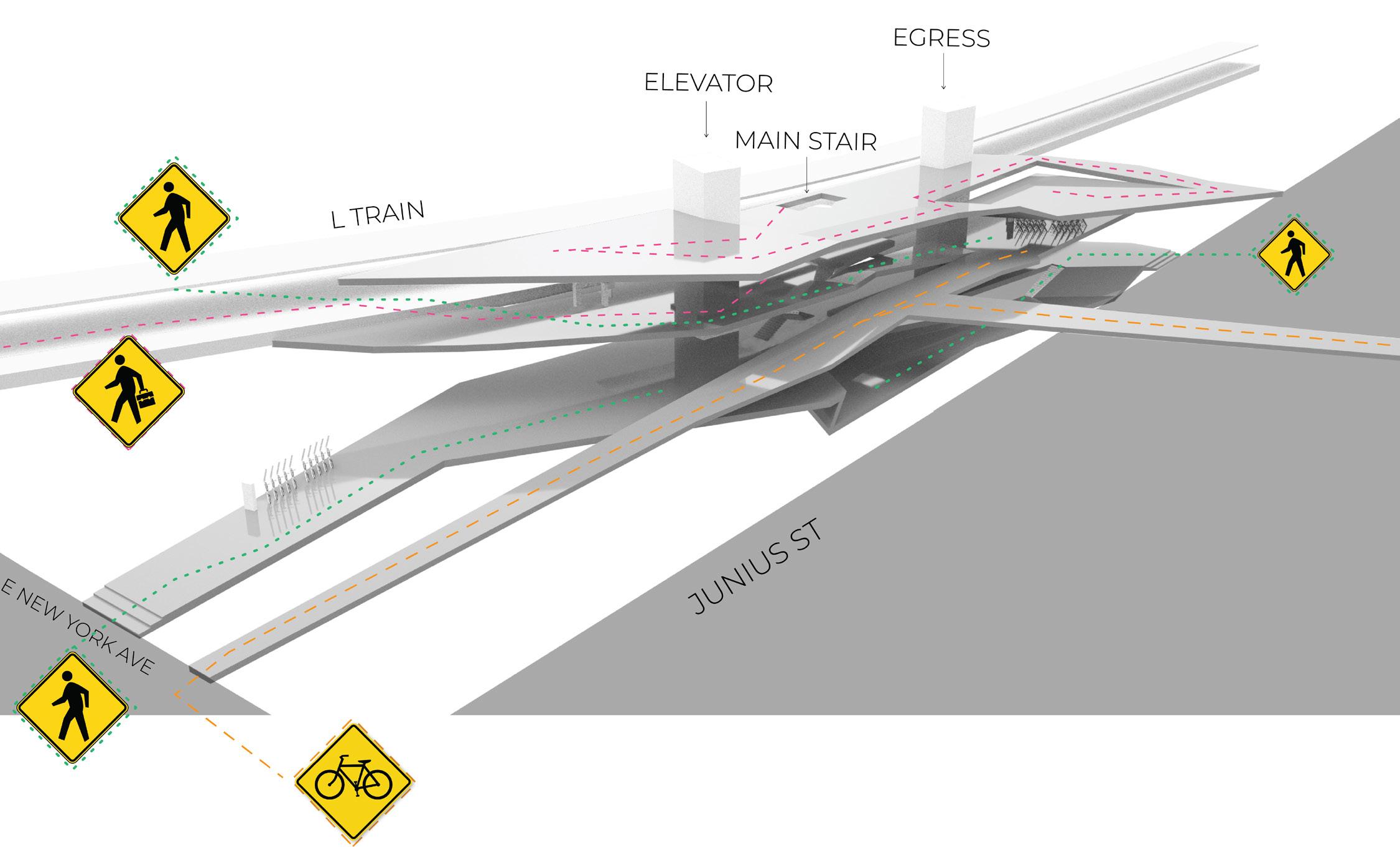

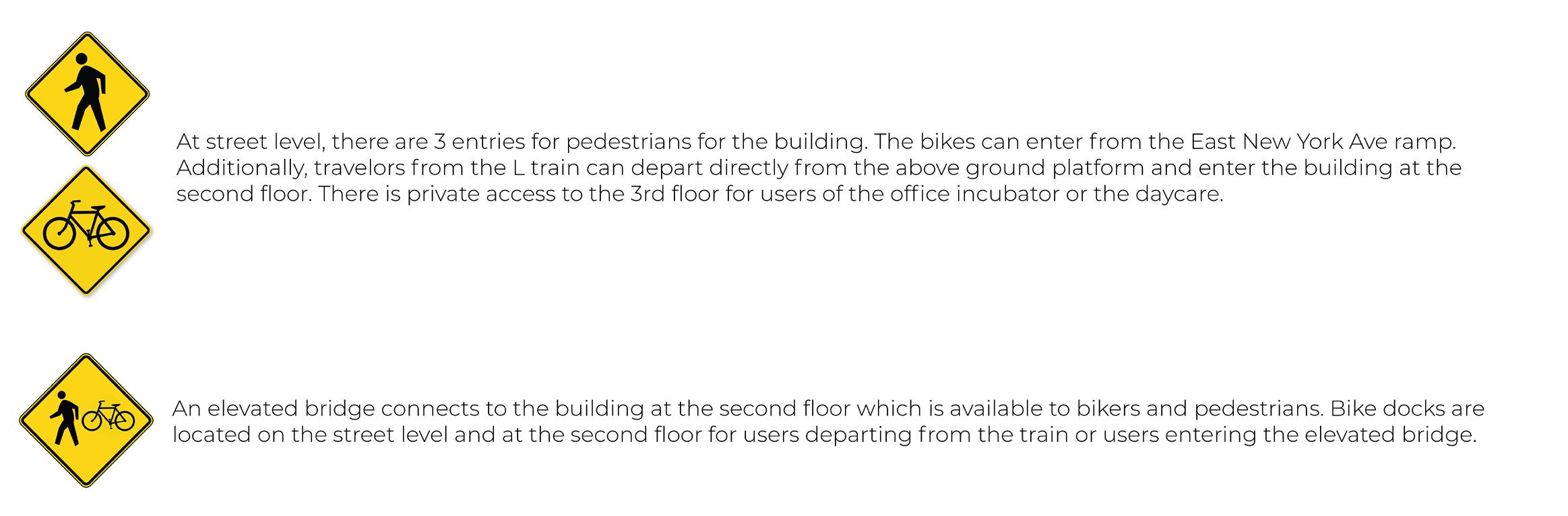

The proposal is for a community building that connects to the Atlantic Ave L elevated subway stop. Bike ramps that extend to the larger city as well as to the street connect into the building for better access to the subway. Community programs are strategically dispersed inside and outside of the building for a space that facilitates the growth of this micro-city.

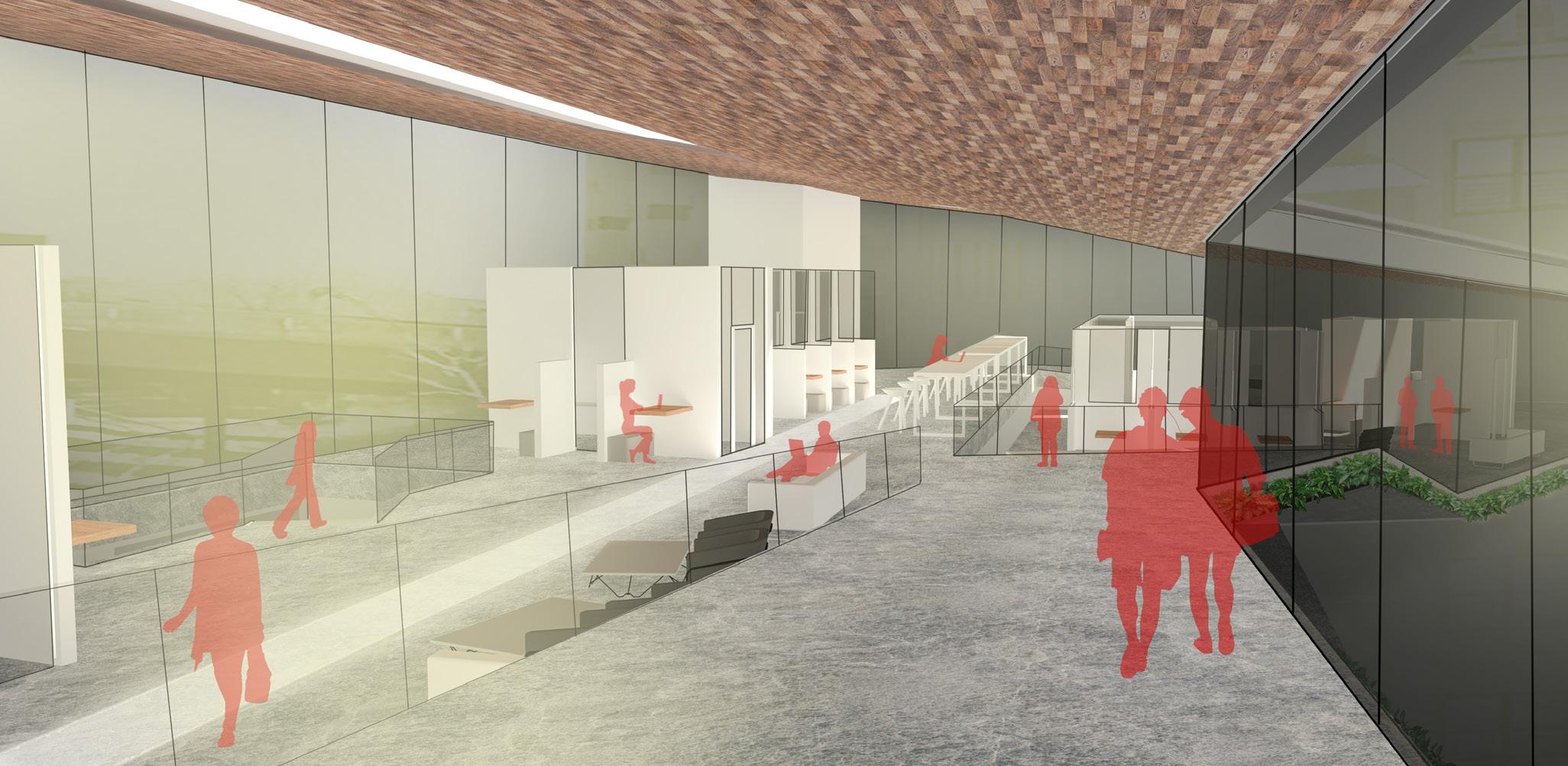

Each floor contains programs that relate to one another, extending from the outside into the inside.

The first floor connects to a community garden where produce can be grown for use in the community kitchens. A large seating area provides dining space and accomodation for parents to view their children playing in the playground. There are citibike docks near the street for pedestrians to rent or make use of the exterior seating.

The second floor connects the open elevated subway platform into the building with a cafe and book stacks for slowing down. One can use this space when entering or exiting the train. On the lower part of this level there are citibike docks and a bike repair center. Two ramps connect at this level for bikes and pedestrians to access the building from the street.

On the third floor, there are open and closed work spaces for start up business along with a community run daycare on the higher level.

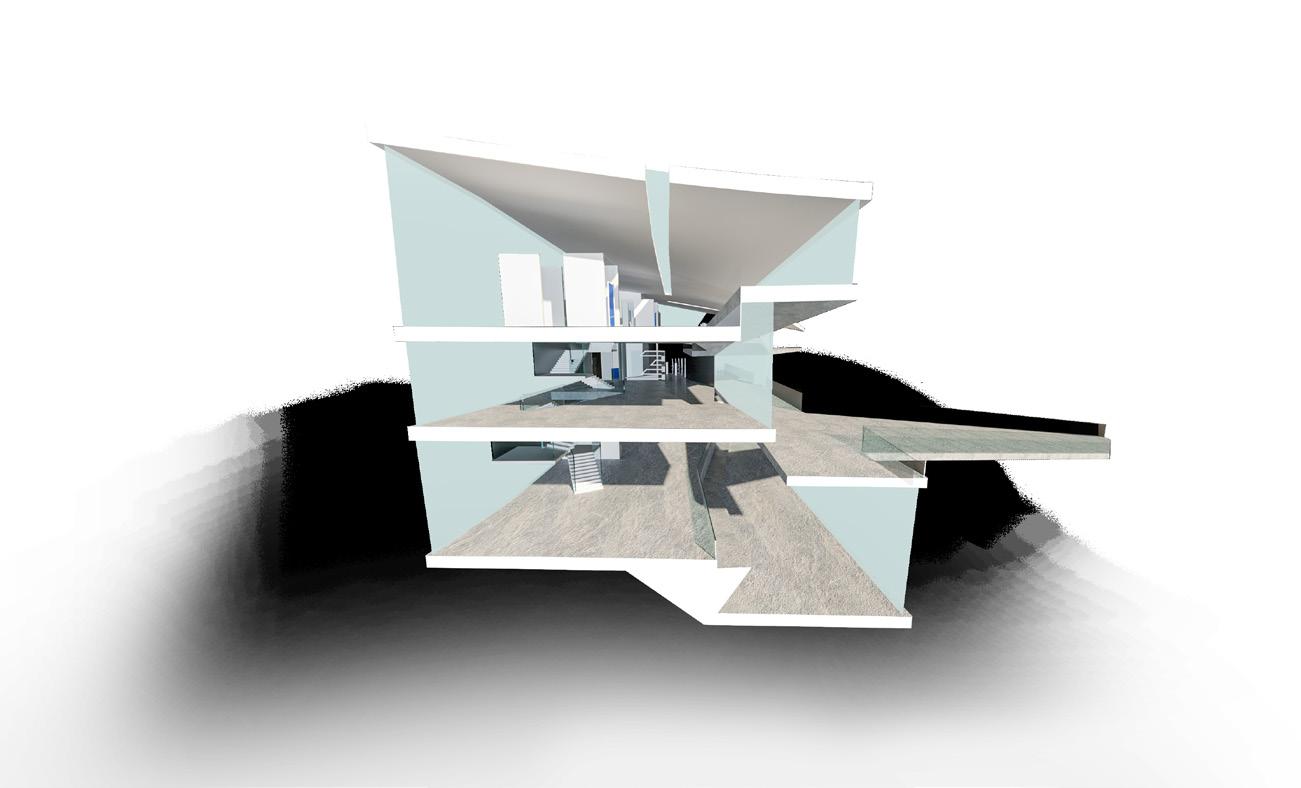

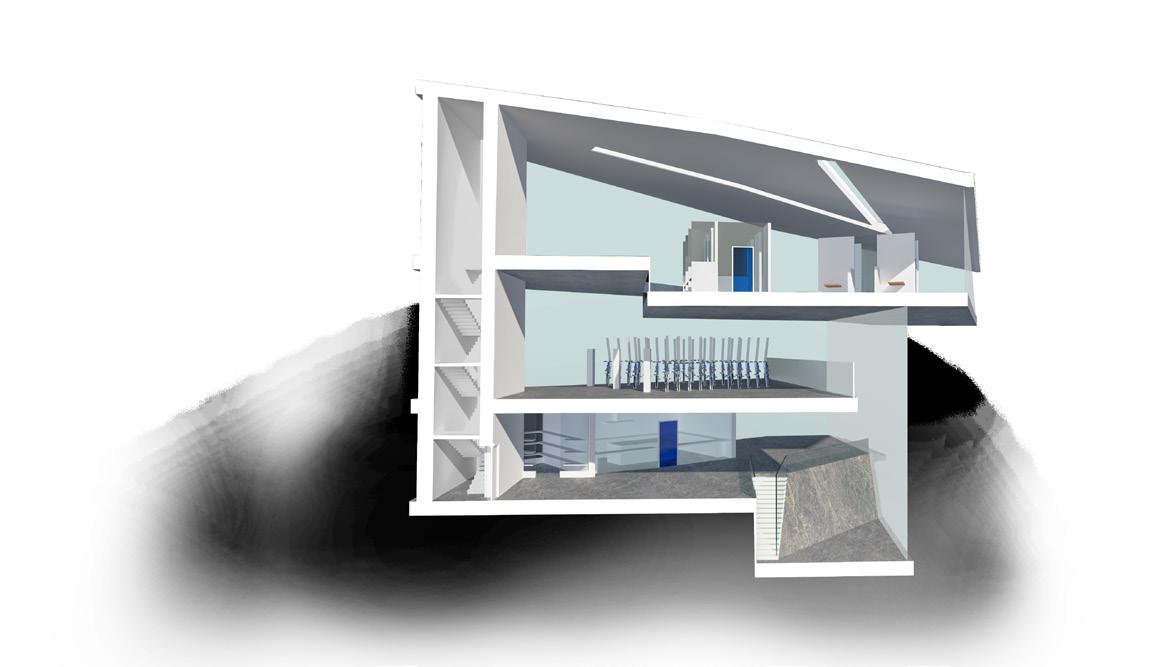

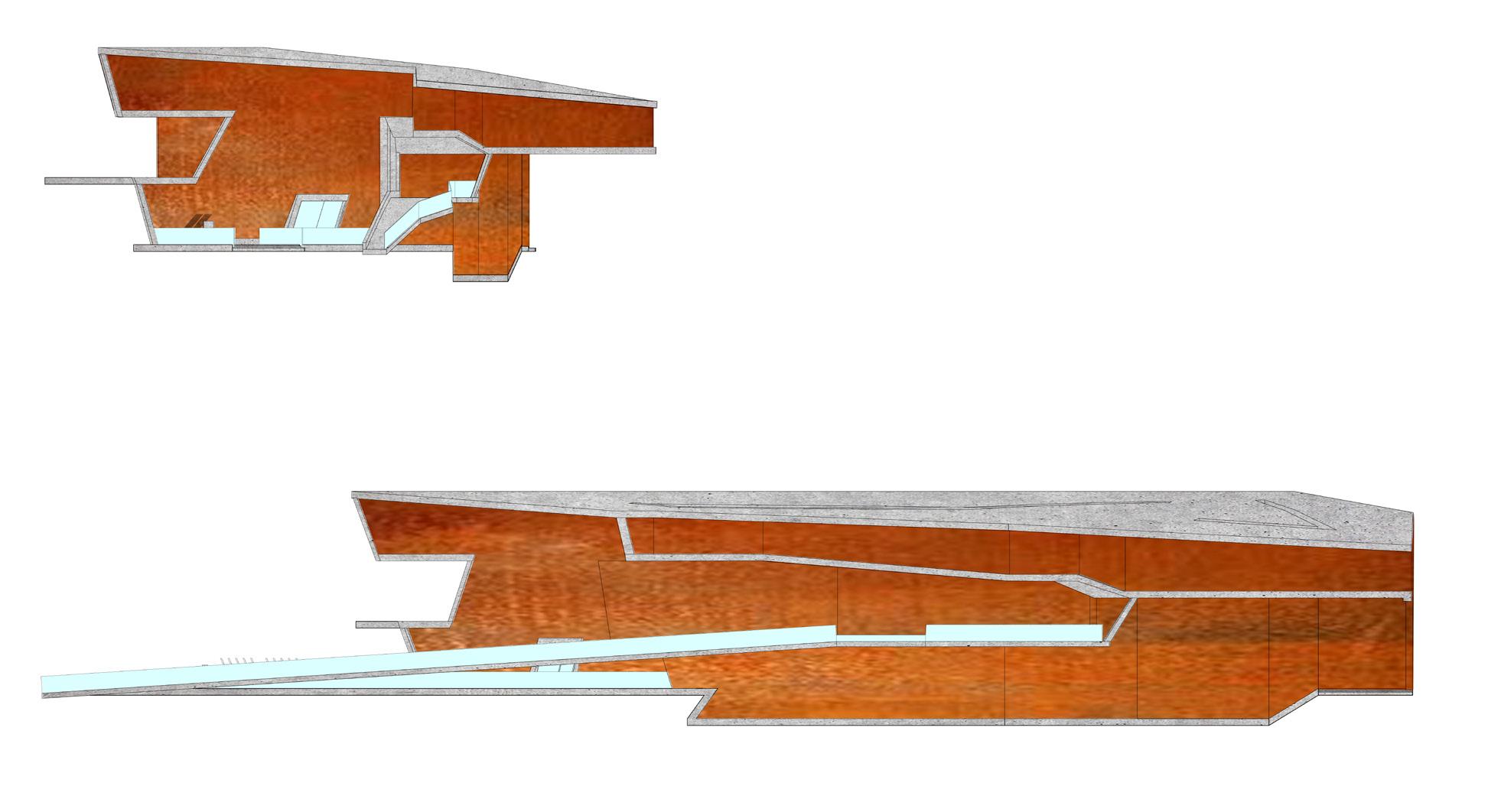

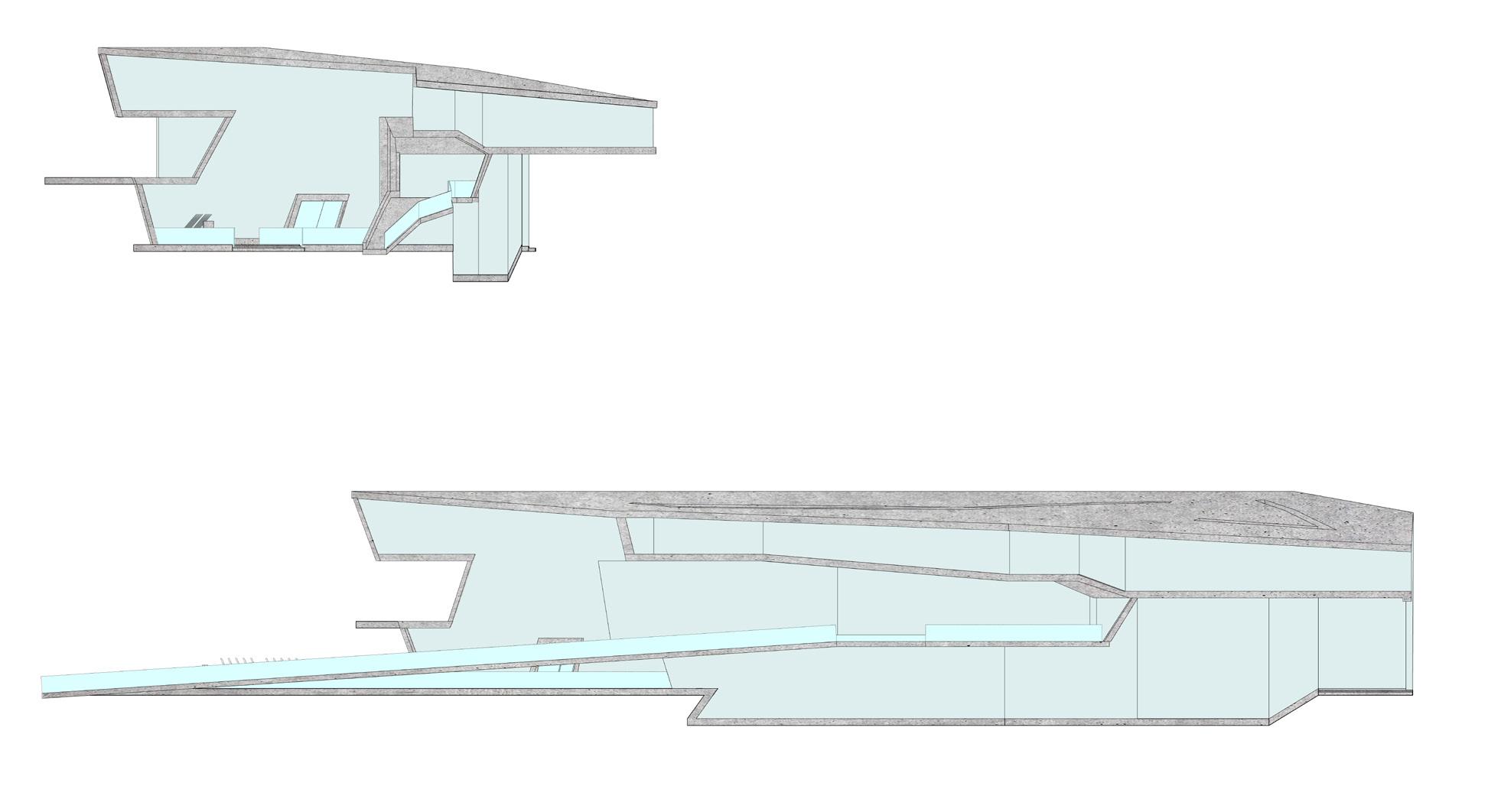

The sections are displaying the relationships of the 3 floors, exterior and interior, and the elevated subway platform to hovering over the freight train tracks. Shifting floor plates and different levels within a 3-story building are seen through the sections

The building resolves itself as it passes over the freight train below the first floor as well as dipping next to the train, maintaining clearance for the freight cars. It also creates a connection to the elevated subway platform at the second floor for immediate entry to the building and protection from harsh weather. The building contains citibike docks and other programs for the community as it hovers in the inbetween space of below grade and above grade.

ROOF EL + 65.00 FT

ROOF EL + 50.82 FT

FLOOR 3 EL + 41.00 FT FLOOR 3 EL + 35.00 FT

FLOOR 2 EL + 21.00 FT

BIKE PATH RAMP EL + 13.82 FT

FLOOR 1 EL 1.00 FT (0.00 @ E NEW YORK AVE) SEATING (FLOOR 1) EL - 9.00 FT

FLOOR

FLOOR

FLOOR 3 EL + 29.00 FT

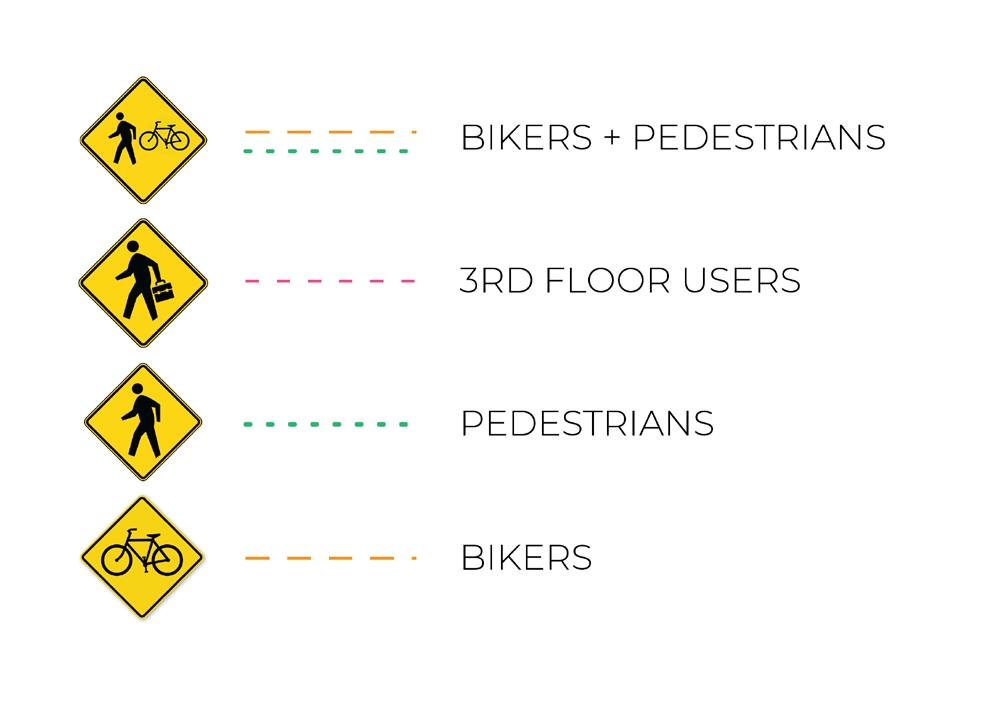

Flow patterns from the street and elevated train platform, in addition to types of users can be seen in an abstracted view of the building.

The building is a series of plates that shift in the z axis to provide seperation and view above, below and through the building. Access to the building is very public and promotes the integration of all ages and types of users to collaborate together or facilitate their own endeavors.

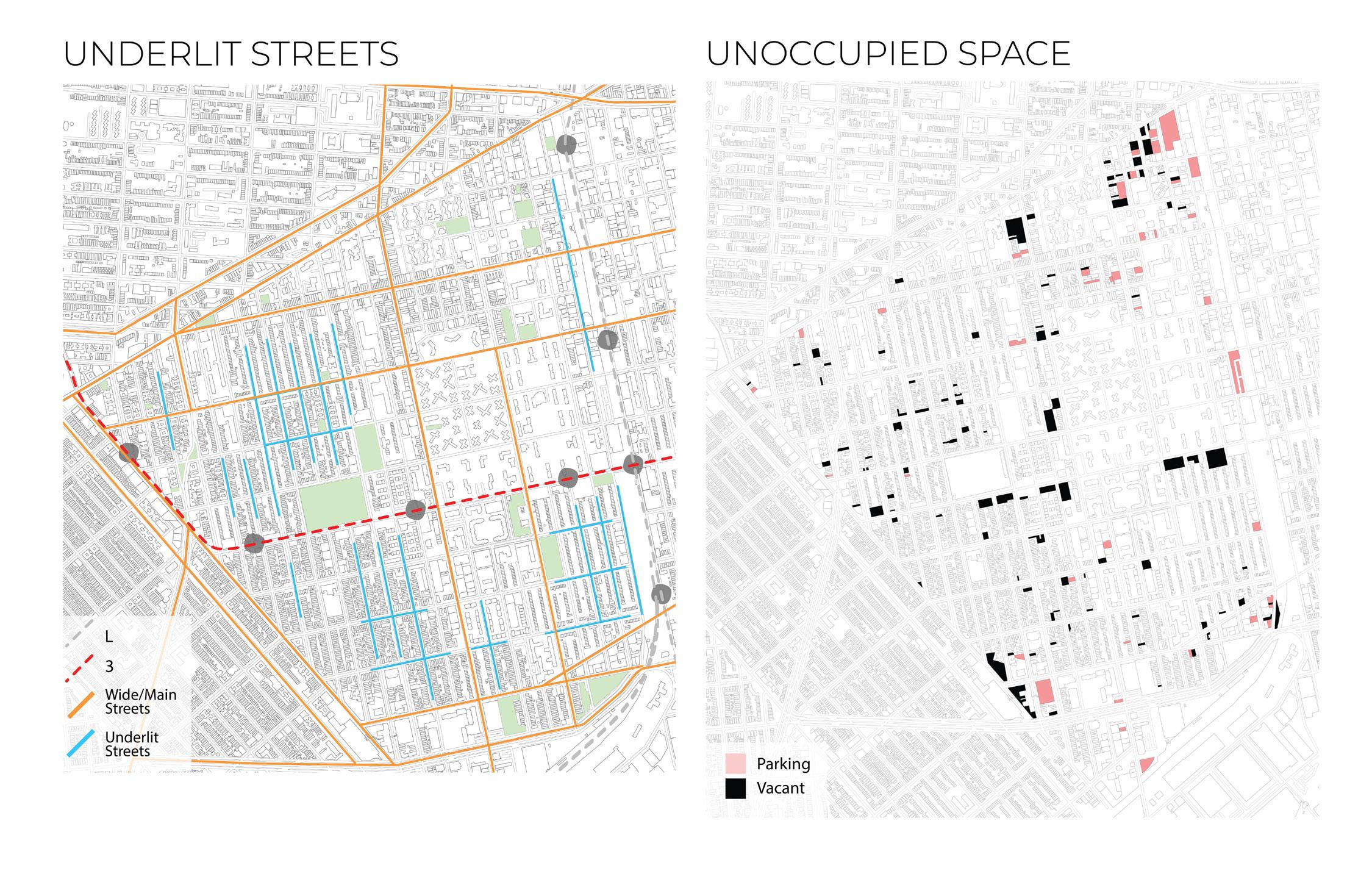

A longer bike path will connect the city at 5 points where riders and community members can enter or exit. Bike paths and buildings will provide street lighting for underlit streets, making walking at late hours safer and more comfortable.

For 4 other locations placed near existing community programs the first building can be connected to the others through the elevated path.

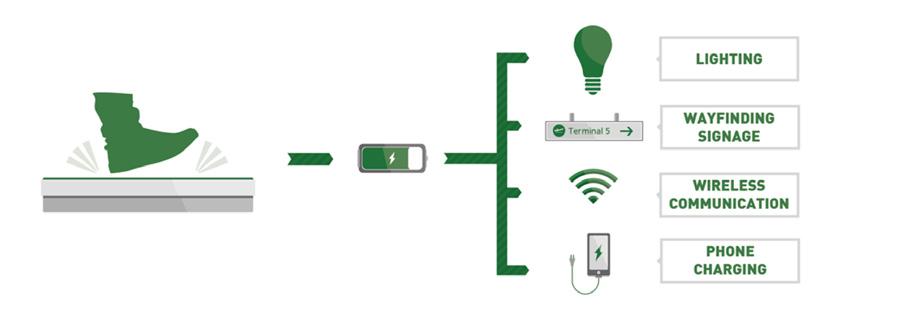

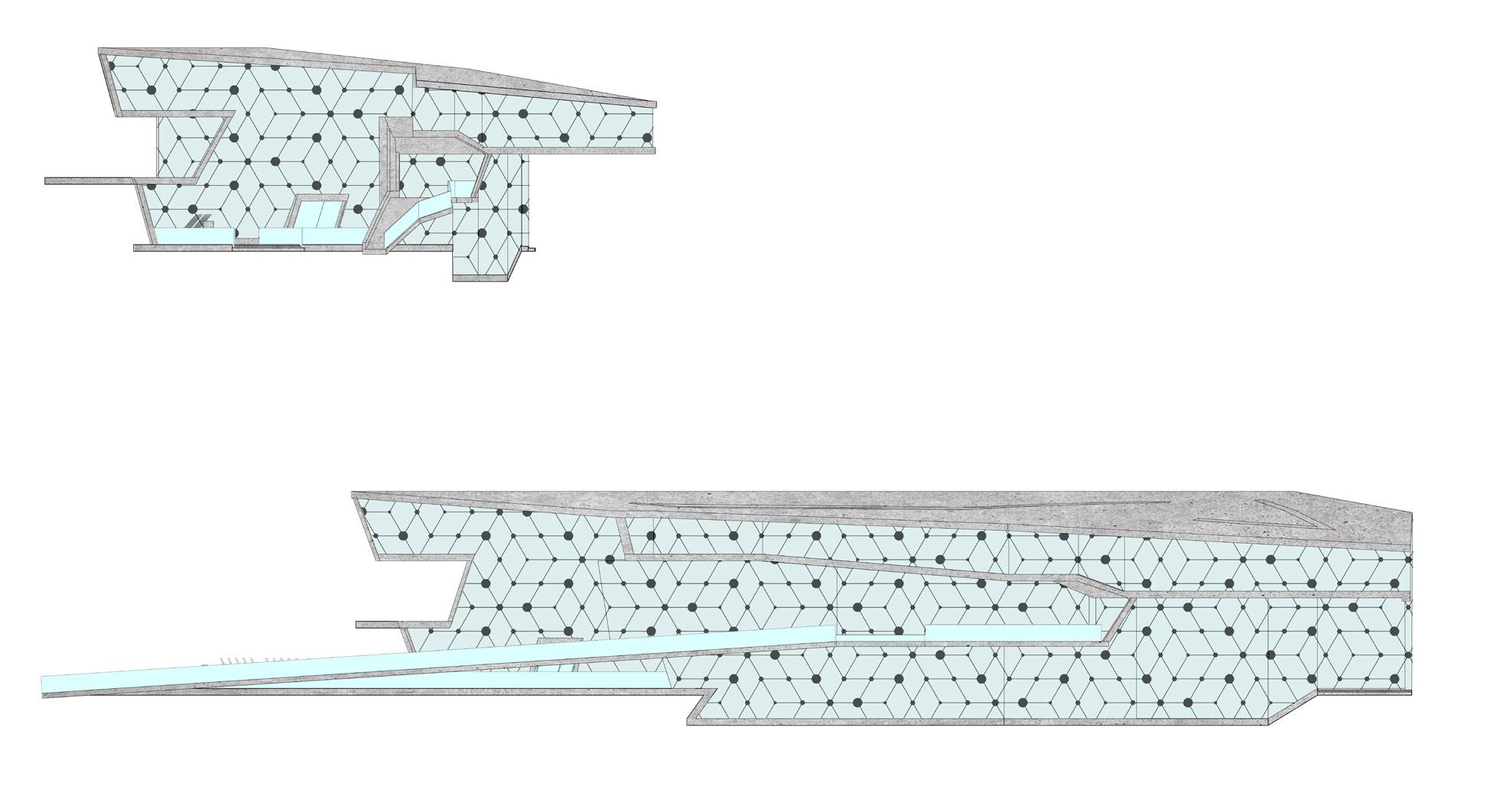

In the most traffic heavy areas, technologically advanced tiles are laid, that generate energy for the building itself, with potential to generate energy for other parts of the city.

The “recycled rubber ‘PaveGen’ tiles compress electromagnetic generators below when pressure is applied, producing 2 to 4 joules of off-grid electrical energy per step.

If there aren’t enough walkers during the day, the lights would be a little dimmer at night. Low-Power Bluetooth beacons connect to smartphone apps and the system can also communicate with building management systems.The slabs can also store energy for up to three days in an on-board battery.

This material, when applied at the entry paths, train platform, playground, and on elevated bike paths, would be generating a great deal of energy, lighting the building and parts of the city at night for safer travel at odd hours for the members of this community.

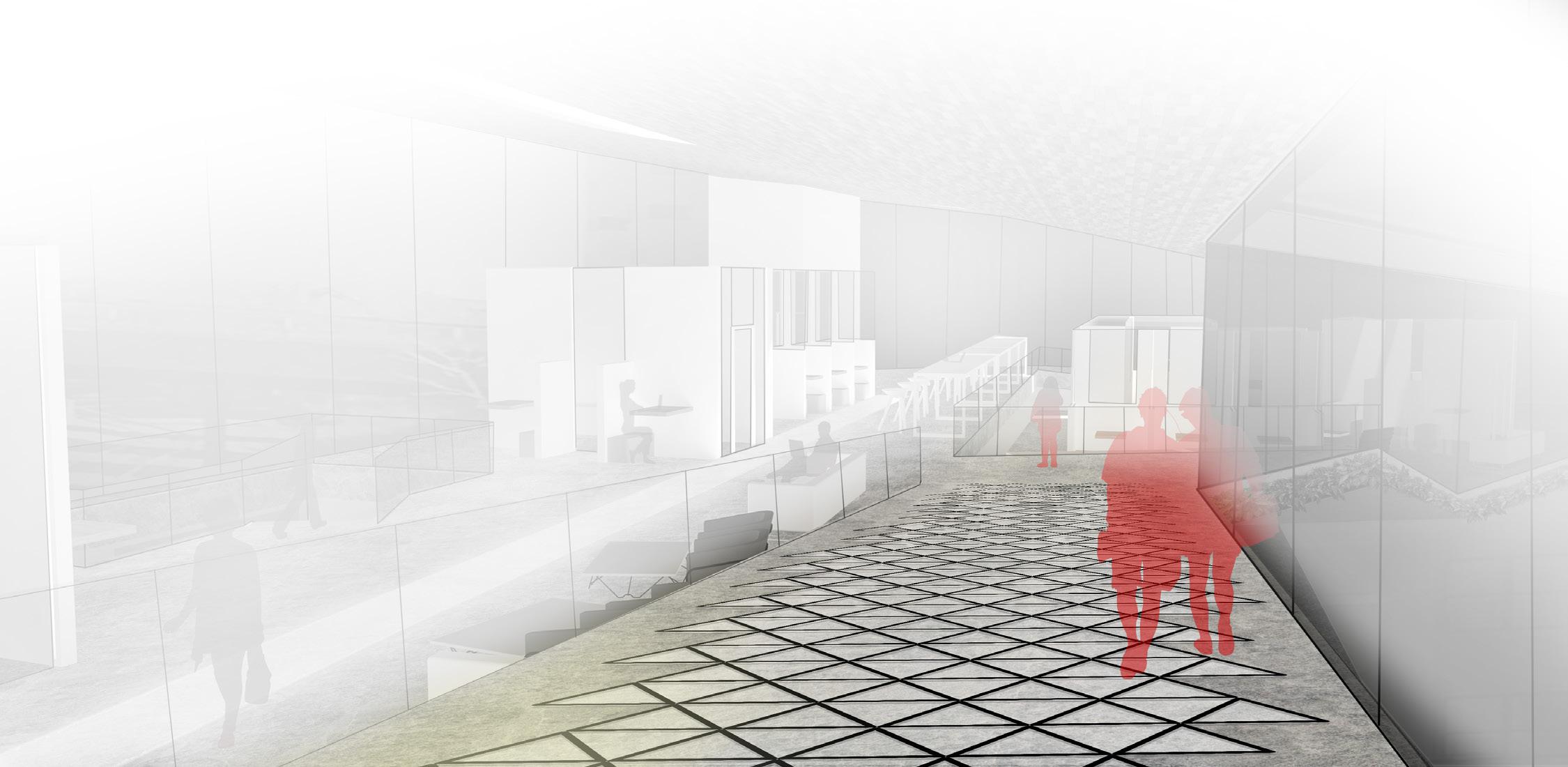

SUBWAY PLATFORM TO FLOOR 2 (VIEW FROM ATLANTIC AVE.)

(VIEW FROM ATLANTIC AVE.)

FLOOR 1 LOOKING SW (VIEW FROM RECEPTION)

FLOOR 3 LOOKING SE TO OFFICE (VIEW FROM DAYCARE)

Front E New York Ave.

The facade can begin as frosted glass, representing the transparency of the building and displaying the movement of the users.

Junius St. Elevation

Front E New York Ave.

In order to study an aesthic that situates the building closer to the look that is more relevant to Brownsville, a brick facade, weathering steel is used to cover the glazing.

Junius St. Elevation

Front E New York Ave.

This pattern can serve as an opaque overlay onto the frosted glass.

Junius St. Elevation

Front E New York Ave.

This pattern in this iteration can serve as holes in the weathering steel for light to enter the building.

Junius St. Elevation

Brownsville is a neighborhood with distinct and vibrant cultures and a network of individuals and organizations that are working in innovative ways to strengthen their community. A family-oriented neighborhood, Brownsville has a unique spirit of creativity, entrepreneurship, resilience, and pride in history and place. In addition to active social service and community-based organizations, Brownsville is home to a multitude of community gardens and urban farms, small locally-owned businesses, and dozens of murals, largely painted and designed by neighborhood youth.

While Brownsville is unique, many of the challenges it faces are all too common in American cities due in part to historical patterns of residential racial segregation and income inequality. Seventyeight percent of Brownsville residents are black, 19 percent are Hispanic, and one in three residents are foreign born.1 Brownsville residents face some of the worst health outcomes in the city and suffer from cycles of violence and trauma.2 Many in this community struggle to find work and realize economic advancement. It is in pursuit of more equitable health, social, and economic outcomes that the City of New York, led by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) and in collaboration with community partners, has created the Brownsville Plan.

In the 1880s, the Brownsville neighborhood was initially developed as a residential area of lowscale, wood-frame homes. By the 1940s, Brownsville’s housing stock had fallen into severe disrepair, with high vacancy rates and poor sanitation. Urban renewal policies were implemented in the neighborhood in an effort to address poverty and blight. Tenements were replaced with public housing towers in the 1950s and 1960s, which remain prominent features in the neighborhood. By the 1970s, many academics and public officials hypothesized that the architecture of public housing was itself a cause of poverty and that a new solution was needed. This led to the idea of “defensible space,” where lower-scale buildings with private entrances were situated around open spaces. In Brownsville, Marcus Garvey Village was developed based on these principles. By the 1980s, large parcels of vacant land spread across the neighborhood, partly as a result of continued urban renewal. Community leaders worked with the City to redevelop many of these sites with affordable for-sale homes under the Nehemiah Program.

Despite these waves of redevelopment, vacant City-owned land remains a common backdrop throughout much of the neighborhood. While it is a reminder of the City’s unfulfilled efforts from the past, it also presents a rare and critical opportunity to develop much-needed affordable housing and achieve shared community goals today.

Brownsville is a neighborhood with many boundaries. It is bordered by imposing transportation infrastructure that isolates it from neighboring communities. Large NYCHA housing developments, wide streets, and vacant spaces segregate certain parts of the neighborhood from each other and create perceptions of an unsafe environment that discourages gathering. Improving connections— both through physical and programmatic interventions—can build social connectedness, positively impact mental and physical health, and improve economic outcomes.

The physical design of neighborhoods can have a significant effect on crime rates, and in turn crime can influence the physical design of a neighborhood. In Brownsville, NYCHA developments are close to one another, but each development is a campus of its own with separate community facilities and often with no adjoining pathways to travel from one to the next. Other multifamily housing developments in the neighborhood have been designed around security—with single points of entry to a whole block of residential buildings. Through a series of physical and programmatic interventions, the City will work to break down this neighborhood isolation. Underlying this approach is a series of design principles called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), which emphasizes a variety of people-centric techniques to design and activate the built environment to reduce crime.

The Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (MOCJ) has launched a new CPTED initiative to conduct comprehensive surveys of NYCHA developments and surrounding neighborhoods to identify ways in which the built environment can help prevent crime. Safer crossings will encourage pedestrian safety and better connect NYCHA developments to surrounding streets and amenities. All residents of the neighborhood, as well as local businesses, will benefit from greater physical connectedness, improved transportation access, and a more pleasant walking environment.

Streets and sidewalks are the public spaces New Yorkers use most, whether to access services and public transit or connect with their neighbors. The main corridors in the neighborhood, however, are often disconnected from each other and contain vacant lots and storefronts. Livonia Avenue, for example, has excellent transit access but also a number of large vacant lots that impact safety and deprive the area of much-needed retail, entertainment, and other activities. The Department of Transportation (DOT) will release a Livonia Avenue Streetscape Plan to identify ways to make the corridor safer and more attractive, such as with enhanced lighting and sidewalks.

During the community planning process, residents of southern Brownsville spoke of their isolation from the many services and amenities that exist in the northern portion of the neighborhood. New mixed-use affordable housing projects will bring services and activities to this area. City-financed, mixed-use developments along New Lots and Hegeman Avenues will activate longunderutilized sites through new development; these projects include the Ebenezer Plaza project, which will create more than 500 new affordable rental apartments, integrated with new retail and community facilities. Along the historic north-south corridor of Mother Gaston Boulevard, HPD and NYCHA are planning new mixed-use affordable housing developments on City-owned vacant land, which can help to promote street activity and safety, while creating new spaces to bring people together.

By: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

By: NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development

The Brownsville Plan will lead to the creation of over 2,500 new affordable homes, representing more than $1 billion of investment. New development on vacant City-owned land will support community goals around health, economic opportunity, and the arts with a new cultural center, a new hub for innovation and entrepreneurship, and new neighborhood retail and community space.

The plan will also coordinate over $150 million in critical neighborhood investments, including improvements to Brownsville’s parks, NYCHA developments, and surrounding street, and more.

01 Promote active mixed-use corridors

Increase access to services and amenities that bring activity to Brownsville’s streets

02 Improve connections throughout the neighborhood

Implement physical, design, and programmatic interventions that reduce social isolation and improve safety

03 Create active and safe public spaces

Improve safety and health by creating high quality places for gathering, programming, and community building

04 Provide resources to support healthy lifestyles

Expand City and community programming and create new policies to support healthy Living, eating, gardening, and exercise to reduce health inequities

05 Connect Brownsville residents to jobs and job training

Pair city investments with opportunities for economic advancement

06 Support small businesses and aspiring entrepreneurs

Enable local businesses to grow and thrive

07 Improve housing stability and support residents at risk of displacement

Ensure that residents have opportunities to stay in the neighborhood, including those facing foreclosure or homelessness, or those seeking to buy a home

08 Provide Support and capacity building opportunities

Prepare local organizations to continue the work of this plan into the future

*** Brownsville Rising can be seen as an interpretation of the The Brownsville Plan, as it aims to meet the same goals that the plan has in place with the primary goal of supporting community. With many housing developments already in place, the proposal for Brownsville Rising is a means of fulfilling the other goals of The Brownsville Plan at the community level.

“About Us.” SUS. Services for the Underserved. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://sus.org/about-us/.

We drive scalable solutions to transform the lives of people with disabilities, people in poverty and people facing homelessness: solutions that contribute to righting societal imbalances. This community program has a location in Brownsville and helps community members daily with a multitude of needs.

“About WIN.” WIN. Women In Need. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://winnyc.org/#trans.

For more than 35 years, Win has provided safe housing, critical services, and ground-breaking programs to help homeless women and their children rebuild their lives. An adjacent community program to the site which provides housing to women and children daily.

Anderson, Deonna. “In New York, a Neighborhood Makes a Pre-Gentrification Plan.” Next City. Next City, June 27, 2017. https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/new-york-brownsville-jobs-businesses-arts-hub-economic-development.

We need a reason for people to come into our community. We’ve been going outside of our community for so long. A community member speaks about how they should not have to leave their community, it should be improved in such a way that people want to come to it without pushing those that are already there out.

Al-Kodmany, K. (2018). PLANNING GUIDELINES FOR ENHANCING PLACEMAKING WITH TALL BUILDINGS. ArchNet-IJAR : International Journal of Architectural Research, 12(2), 5. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.pratt.edu:2048/10.26687/archnetijar.v12i2.1493

The paper discusses the placemaking problems created by tall buildings, and simultaneously attempts to harness the potential of tall buildings to enhance placemaking. The research contends that instead of contributing to the problem of placelessness, well-designed tall buildings can rejuvenate cities, ignite economic activity, support social life and boost city pride through the science, engineering and craftsmanship embodied in these buildings.

By studying a typology that facilitates all the same things that this community needs, we can discuss the best way to build.

Allen, Stan. “Mapping the Unmappable: On Notation”. Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation. London: Routledge, 2009 (40)

The city today is a place where visible and invisible streams of information, capital and subjects interact in complex formations. They form a dispersed field, a network of flows.

This speaks to the idea of transit connections and accessibility in this proposal.

Bellafante, Ginia. “No ‘Inner City’ in Brownsville, Brooklyn, Just Overlooked Strengths.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 30, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/30/nyregion/nadia-lopez-brownsville-brooklyn.html.

Part of the challenge of working in low-income urban communities is the fight against the perception that they are doomed and immiserating, an exercise that has required more energy in the age of President Trump, who has made use of the loaded term “inner city” to invoke the image of nightmare places where death always comes at gunpoint and schools are always synonymous with failure.

Looking at the story of a member of the community who helps the youth of the city and speaks for them so that one may understand a different perspective.

Bloomer, Kent C., and Charles W. Moore. “Body, Memory and Architecture.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 71-74. Academy Editions, 1997.

[We Start with the house (or palace or cathedral) staked out in close homage to the human (or the divine) body and note how the choreography of arrival at the house (the path to it) can send out messages and induce experiences which heighten its importance as a place.] pg. 71-72

This excerpt is about how buildings are experienced, placing the human body at the center of our understanding of architectural form.

This led to an idea about how architecture is a space, but it is also about the spaces around. Our bodies effect the space and the space affects our bodies. In addition, this is a continuous cycle, as the interactions are constantly occurring.

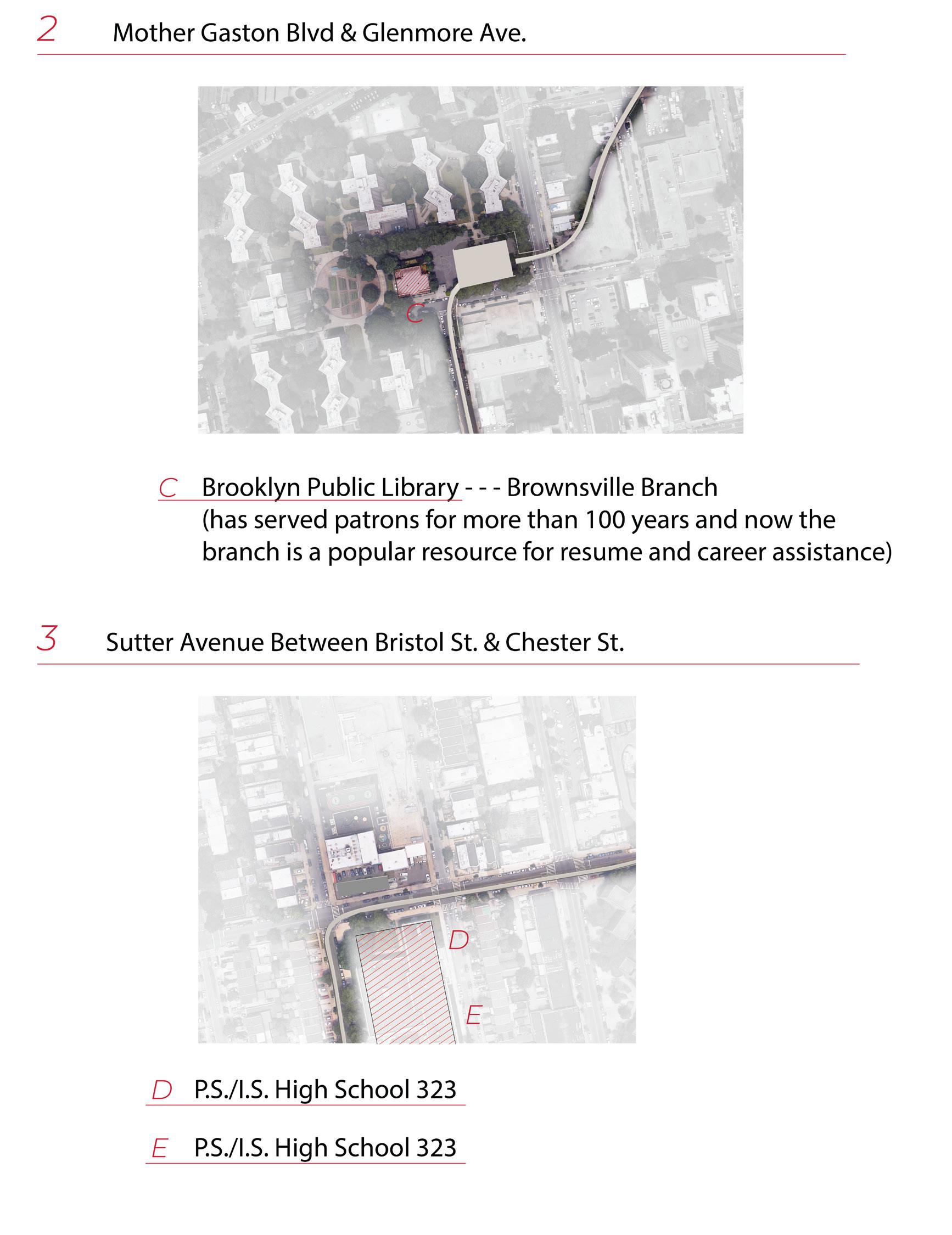

“Brownsville Library.” Brooklyn Public Library, July 4, 2018. https://www.bklynlibrary.org/locations/brownsville.

Brownsville Library has served patrons for more than 100 years. Today, the branch is a popular resource for resume and career help. Its laptops are always in high demand, and children frequent the library’s Homework Help and ProjectArt programs, among others, when school is out.

A historic center that reaches people of all ages in this community and serves as a location for students and adults.

Brueck, Hilary. “In Washington, DC, People Are Using Their Feet To Turn On The Lights.” Forbes. November 18, 2016. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hilarybrueck/2016/11/18/pavegen-energy-generatingsidewalk/#4d1ed3fc78da. “The 68 springy tiles, from British tech startup Pavegen, feel like a stiffer brand of bouncy astroturf, and use people’s steps to fuel a system of magnets below – creating just enough power to turn on the lights nearby.”

Concrete begins to be replaced with recycled car tire tiles that can convert kinetic energy into electrical energy. This material when in application to an area with a lot of pedestrians can give way for helping the building and some surrounding technologies, sustain themselves. The space where applied can transform into one that serves a greater purpose, a sustainable one.

“Build New Subway Lines to Underserved Areas of the City.” The Fourth Regional Plan. Accessed March 5, 2019. http:// fourthplan.org/action/new-subways.

Brooklyn has experienced tremendous growth over the past two decades, mostly in areas already served by the subway. The next wave of growth is likely to occur in Crown Heights, Brownsville, East New York, Flatbush, Midwood, and the Flatlands, which will put tremendous stress on the existing subway system.

We can see which areas are expected to grow next and what data determines this prediction.

BUILDING FEATURE: PLANNING STRATEGIES. (1991). The Architects’ Journal (Archive : 1929-2005), 193(22), 38-41. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.pratt.edu/docview/1427112575?accountid=27668

This article discusses strategies for building air train systems and resolving the congestion of airport traffic from occupants heading to their gate before boarding. The examples help to understand the problems that architecture can work to solve better for users.

Looking at the way people move through this network that is constantly in motion, we can use the similar strategies in the proposal.

Certeau, Michel De. “Spatial Stories.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 115-30. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

(Oral descriptions of places, narrations concerning the home, stories about the streets, represent a first and enormous corpus. The first is of the type: ‘The girl’s room is the next to the kitchen.’ The second: ‘You turn right and come into the living room.’ Now, in the New York corpus, only three percent of the descriptions are of the ‘map’ type.) pg. 118-119

Spatial Stories talks about how form is fragmented and not unique and whole. There are two descriptions of a space and those are the ways by which people understand direction. However, one way of description is more commonly used. What happens when you remove the whole? When you remove the whole, the subject becomes that of the author. Maybe the author becomes the occupant who then destroys or activates the space. At the same time, the author is essential to how we perceive the same thing in different contexts.

Certeau, Michel De. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 91-110. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

(The paths that correspond in his intertwining, unrecognized poems in which each body is an element signed by many others, elude legibility.) pg. 93

Walking in the City exemplifies the various components of a city. There is a sidewalk, but it is activated once people walk on it and how they walk on it. It only becomes the space between the building and the street when it is used as that.

The topography of the city can be abstracted to tell a story about the different trajectories within it. There can be layers to discuss how these components work together or separately. On a sidewalk, one can observe many things but the way in which these can be represented doesn’t have to be so rudimentary.

Certeau, Michel De. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 91-110. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

(Their story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together.) pg. 97

Walking in the City exemplifies the various components of a city. There is a sidewalk, but it is activated once people walk on it and how they walk on it. It only becomes the space between the building and the street when it is used as that. How do people move and to what extent does walking become impossible? Walking connects locations that could otherwise not be linked however walking a great distance is a difficult task. It can be a leisurely stroll through the park, or it can be the only way to access the nearest subway stop.

“Countermeasures and Safety Effectiveness.” Pedestrian & Bicycle Information Center. Accessed April 4, 2019. http://www. pedbikeinfo.org/topics/countermeasuressafetyeffectiveness.cfm.

PEDBIKESAFE describes the process for selecting and implementing countermeasures and each includes an interactive selection tool and case studies.

This resources tells us at the national level, safety measures and crash data on pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers.

Fitzsimmons, Emma G., and Tyler Blint-welsh. “Subway Delays Hit Low-Income New Yorkers the Hardest, Report Says.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/nyregion/mta-subway-delaysincome-neighborhoods.html.

Apartments and homes with good subway access tend to cost more. That means higher incomes are linked to shorter commutes and lower incomes to longer commutes, according to the report. So when the system inevitably melts down, low-income New Yorkers are more likely to be swept up in delays.

Transit data that relates to income levels explains the impact on commuters like those living in Brownsville and alike neighborhoods.

Gannon, Devin. “Interactive Map Identifies the New York City Neighborhoods Most Underserved by Transit.” Maps, Transportation. 6sqft, February 12, 2018. https://www.6sqft.com/interactive-map-identifies-the-new-york-city-neighborhoodsmost-underserved-by-transit/.

A transit gap exists when there is an imbalance between the demand on the market and the quality of service. The map allows users to enter an address, city, state or zip code to discover which areas do not have equitable access to public transportation.

This map can allow the gathering of data to determine what are the most problematic areas of the city in terms of transportation.

Goodyear, Sarah. “A Very Different Reception for Bike Lanes in Brooklyn’s Poorest Neighborhood.” CityLab, April 18, 2014. https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2013/07/very-different-reception-bike-lanes-brooklyns-poorest-neighborhood/6309/.

The new bike lanes are just one of many efforts by neighborhood partners to increase opportunities for healthier living in Brownsville, including walking groups for seniors and a program that brings fresh produce to the neighborhood. This example of community working together to provide the city its needs is an embodiment of the everyday efforts the members of this city.

Green, Larissan Danielle. “Energy from Your Feet: When Sidewalks and Dance Floors Become Energy Sources.” TED Blog. June 05, 2013. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://blog.ted.com/energy-from-your-feet-when-sidewalks-and-dance-floorsbecome-energy-sources/. “a groovy company based in Rotterdam that has used dancefloor power to create more than 8 billion joules of electricity so far.”

A European company begins applying a new floor material technology in dancefloors to generate electricity. There is so much potential for the application of this conversion of energy in a place like New York, where hundreds of thousands of people always have somewhere to be.

Holl, Steven. “Anchoring.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 109-10. Academy Editions, 1997. (Building transcends physical and functional requirements by fusing with a place, by gathering the meaning of a situation.) pg. 109

This section is Steven Holl’s concern with both the metaphysical and phenomenological connection between architecture and its location.

What is the meaning of site? Many factors are associated with site because they are the components of the area. Architecture has to respond to those and work with the factors.

Hu, Winnie. “A Tired Brooklyn Transit Hub Is Finally Getting Attention.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 26, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/26/nyregion/a-tired-brooklyn-transit-hub-finally-getting-attention.html?register=ema il&auth=register-email.

Julie Locke, 43, said she would rather see the city focus on adding more affordable housing and reducing crime than on bringing in upscale amenities that would be out of reach for many residents. “This is not a destination,” she said. “This is a very poor neighborhood — s ome people are lucky to have $5 to spend.

A community member accounts for how they wish to see the city grow and what it needs as well as what is not needed.

Hunter College, UAP. “BROWNSVILLE WORKS! a Strategic Economic Development Plan.” NYC: Hunter College Department of Urban Affairs and Planning Graduate Urban Planning Studio 2011-2012, 2011. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/community/uap-studio-brownsville-works.pdf

Although Community District 16 is advantageously located near a transportation hub (Broadway Junction), the primary retail corridors, Pitkin and Rockaway Avenues, are not well served by subways and bike lanes. In addition, subway stations located in the middle of industrial parks are not conducive to directing pedestrian traffic towards the retail corridors, which limits the customer base.

This is a display of the prevailing problems in the city outside of housing issues.

Libeskind, Daniel. “End Space.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 274-75. Academy Editions, 1997.

(I am a fascinated observer and a perplexed participant of that mysterious desire which seeks a radical elucidation of the original precomprehension of forms - an ambition which I think is implicit in all architecture.) pg. 275

Libeskind carries out a fundamentally theoretical endeavor, using text and drawings to explore the tensions between experience, intuition and formalization, the voluntary and involuntary.

There is a separation in experience and understanding that is different for everyone but what is being investigated is creating a singular condition for all occupants whether they know what they are experiencing or not.

Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. (The transition from one transportation channel to another seems to mark the transition between major structural units.) pg. 74

The book is the result of a five-year study of Boston, Jersey City and Los Angeles on how observers take in information of the city and use it to make mental maps.

This book provides necessary data needed in order to understand further the insights of occupants in particular cities, adding to the already existing personal insights of New York City and Brooklyn. Experiences between these cities are fundamentally similar and the piece about nodes has a strong connection to points of reference within a city.

Miller, Stephen. “Street Seats and Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville and East New York.” Streetsblog New York City, August 12, 2015. https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2015/08/12/street-seats-and-bike-lanes-come-to-brownsville-and-east-new-york/.

The neighborhood also got its first Street Seats, installations that convert a curbside parking space into seating and greenery maintained by a local organization or business.

People are making use of the streetscape and want to engage with one another to different degree by being with their community.

Nagel, Till. “United Cities of America.” Senseable City Lab. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/ unitedcities/.

This study analyzes commuter patterns across The United States using telecommunication data.

To further the investigation of representing patterns in the movement of people, this data assisted in thinking about how public transport systems and walking are connected. The representation of a radius depicts data of how far an individual would walk after leaving public transport or to arrive at public transport.

Nyhan, Marguerite. “Urban Exposures.” Senseable City Lab. 2016. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/ urban-exposures/.

This group of researchers analyzed “How Cell Phone Data Helps Us Better Understand Human Exposure To Air Pollution.”

The maps displayed by this group look like redline maps, areas of a city colored to represent a set of data. Some of the data they gathered, specifically the population data is used to further the analysis of Brooklyn. This way of representing the data also reinforces the de-familiarization of how the data is initially read, as the popularly known redline map to further investigation revealing the map to be about population.

Polansky, Chris. “Will Brooklyn’s Freight Trains Get Rolling Again?” The Bridge. Brooklyn Business News, February 19, 2019. https://thebridgebk.com/will-brooklyns-freight-trains-get-rolling-again/.

The answer is that a few freight trains still roll along the Bay Ridge Branch of the New York & Atlantic Railway, typically carrying goods bound for points east.

By looking at the possibility to build on the tracks, this article displays that the trains are still in use although less frequently than before.

Raby, Sam. “Interactive: Mapping New York’s Affordability Gap.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, December 21, 2017. https://ny.curbed. com/2017/12/21/16752942/affordable-housing-new-york-ami-interactive-map.

To categorize affordable housing—and give subsidies to developers for creating it—New York specifies different income ranges that determine which rents certain affordable units can charge, and who can apply to live there.

In order to better understand the economic state of this neighborhood, we must look at the recent AMI calculations of this area.

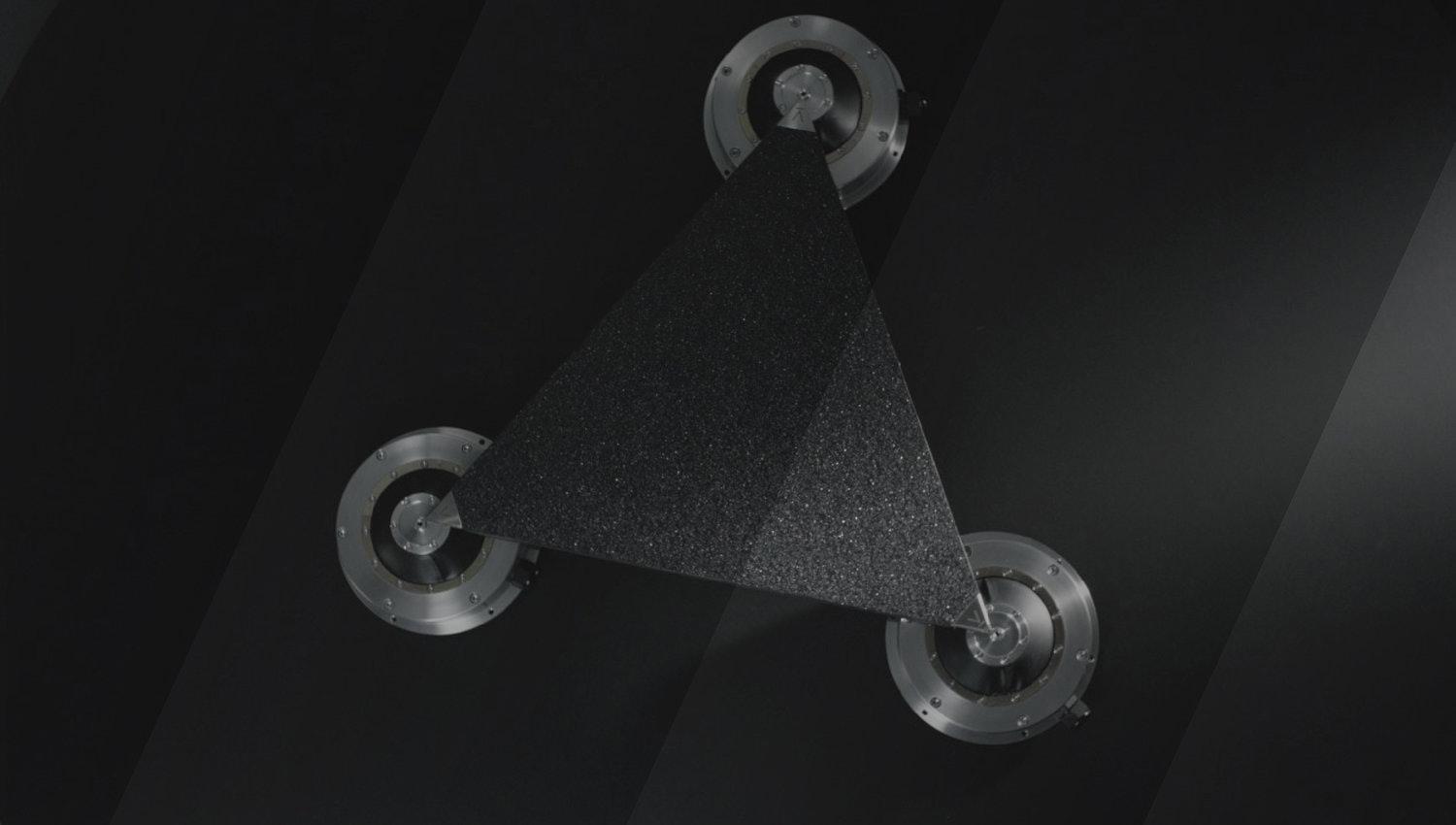

Ratti, Carlo. “The Copenhagen Wheel.” Senseable City Lab. 2009. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/ copenhagenwheel/index.html.

This site is introducing a product for bicycles connected to a mobile app that transforms the bicycle into a hybrid e-bike, recording information as one rides a bike.

This product is about how transport systems that people frequently use within a particular city can enhance travel for the user as well as the city as a whole. In addition, certain technologies can be applied to transport systems to be integrated into cities with different densities of transport methods to record and enhance the city.

Reyna, Rikki, and Erin Durkin. “Brownsville Is Brooklyn’s Worst Neighborhood for Children Due to High Poverty, Lousy Access to Fresh Food and Day Care.” nydailynews.com. New York Daily News, April 8, 2018. https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/ brooklyn/brownsville-brooklyn-worst-neighborhood-children-article-1.3009978.

“What makes Brownsville unique is you have a scarcity of a whole slew of assets. It’s not a mild scarcity,” said Citizens’ Committee for Children research director Apurva Mehrotra. “I really don’t think there are many — or any — other neighborhoods in the city, even those that are economically distressed, that are in that kind of situation.”

There is a lack of resources for the people that live in this city and there is simply a need to provide better accessibility all together throughout the city.

Salomon, David. “Experimental Cultures: On the “End” of the Design Thesis and the Rise of the Research Studio.” Journal of Architectural Education65, no. 1 (November 22, 2011): 33-44. Accessed September 2, 2018. (The emphasis on a plurality of research methods reinforces the notion that research cannot be limited to science or the scientific method.) pg. 34

This essay locates the rise of the research studio in the United States within the historically changing definition and role of thesis in professional degree programs.

We must explore new ideas in different methods since there is not a certainty like science in architecture. Architecture aims to answer a question to its best ability but by no means is that answer the only one. It doesn’t solve the problem, it merely reframes the question.

Salomon, David. “Experimental Cultures: On the “End” of the Design Thesis and the Rise of the Research Studio.” Journal of Architectural Education65, no. 1 (November 22, 2011): 33-44. Accessed September 2, 2018. (. . . In order for your design to be significant - you must first research the context it operates in and on.) pg. 36

This essay locates the rise of the research studio in the United States within the historically changing definition and role of thesis in professional degree programs.

There are important factors to architecture that are beyond the site that the construction occurs on or even the secondary data about neighboring structures. There are social, political and economic factors about the larger surrounding area and even further zoomed out to the borough. These are the things that once analyzed can truly create a project that can change what architecture can do for people.

Sanders, Alex. “Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville.” Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville | Community Solutions. Community Solutions, February 27, 2013. https://www.community.solutions/blog/bike-lanes-come-brownsville.

After more than two years of discussion and planning, Brooklyn Community Board 16 voted last night to install a network of bike lanes on Brownsville’s streets. The lanes will open up new opportunities for healthy activity for Brownsville residents.

This intervention by the community was the beginning of members asking for change in transportation needs, and more.

Stremple, Paul. “Billion Dollar Development Project Brings Affordable Units, Cultural Space to Brownsville.” BKLYNER, July 30, 2018. https://bklyner.com/brownsville-development/.

All the development is part of the city’s Brownsville Plan, which represents a $1 billion investment into the Brooklyn neighborhood. While it isn’t a rezoning like neighboring East New York, the plan will develop city-owned land to add affordable housing and homes for sale, along with other neighborhood investments.

This is a push towards redeveloping the city and a lot of money is being poured into these types of projects.

Sun, Feifei. “Brownsville: Inside One of Brooklyn’s Most Dangerous Neighborhoods.” Time. Time USA, January 30, 2012. http://time.com/3785609/brownsville-brooklyn/.

I found out that Brownsville has similar crime rates to a place like East New York, but is almost a third of its size. Brownsville is one square mile of public housing, basically change happens really slowly there. An overlooked city is in need of an intervention that facilitates growth for its members.

Tempey, Nathan. “Interactive Map Exposes NYC’s Sprawling Subway Deserts.” Gothamist. WNYC, July 12, 2016. http:// gothamist.com/2016/07/12/subway_desert_map.php.

Chris Whong works for the Department of City Planning. Whong decided to draw a map that showed the areas of New York further than 10 minutes from a subway station as floating islands.

The map could serve as a prompt for exploring lesser-known parts of the city.

V, Matt A. “New York’s LED Streetlights: A Crime Deterrent to Some, a Nuisance to Others.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 12, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/12/nyregion/new-yorks-led-streetlights-receive-a-lukewarmreception.html.

The city undertook the changeover less to eliminate the jack-o’-lantern glow of the old high-pressure sodium lights and more for the benefits of LEDs. They are not only more efficient, but they also have a 15-year life span, which means less maintenance.

The beginnings of street lighting changes are occurring in this city in order to introduce safety and accessibility.

Velsey, Kim. “In Brooklyn, the Weeksville Neighborhood Stirs.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, July 14, 2015. https://www.wsj.com/articles/once-forgotten-weeksville-area-stirs-in-brooklyn-1436522402.

You might say Weeksville is hiding in plain sight. The neighborhood, in the easternmost section of Brooklyn’s Crown Heights, was founded in 1838 as one of the country’s first free black settlements.

Looking at a nearby town that has revitalized recently to embrace its historic background for others to learn and experience.

Warerkar, Tanay. “Brownsville Will Get Nearly 900 New Affordable Apartments.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, July 27, 2018. https:// ny.curbed.com/2018/7/27/17621370/brownsville-brooklyn-affordable-housing-nyc.

The largest of the three developments, Livonia 4, will bring 420 apartments to a series of sites along Livonia Avenue between Powell Street and Mother Gaston Boulevard. This health-focused development will also include a supermarket, a cafe, a rooftop greenhouse, community gardens, a new senior center, and a family recreation center.

As housing grows in this neighborhood, there is a need for community space that is open to those distinct from these new housing developments and the existing ones.

Webster, George. “Green Sidewalk Makes Electricity -- One Footstep at a Time.” CNN. October 13, 2011. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2011/10/13/tech/innovation/pavegen-kinetic-pavements/index.html. “Although each step produces only enough electricity to keep an LED-powered street lamp lit for 30 seconds, Kemball-Cook says that the tiles are a real-world ‘crowdsourcing’ application, harnessing small contributions from a large number of individuals. ‘We recently came back from a big outdoor festival where we got over 250,000 footsteps -- that was enough to charge 10,000 mobile phones,’ said Kemball-Cook.”

Data shows that this technology is 25 footsteps to 1 charged cell phone, which is a very attainable equation since on average most Americans take 5000 steps in a day.

Since most areas in Brooklyn have a population density of 200,000 to 700,000 people, there is much potential to generate a significant amount of energy.

Wiggins, Glenn E. “Methodology in Architectural Design.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept. of Architecture. January 01, 1989. Accessed January 19, 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/14498.

This thesis attempts to demystify the process of architectural design. Through a close scrutiny of existing literature, incorporation of personal experience as an architect, and testing of theories with lay, novice, and expert designers a theory of design methodology is proposed.

Using various techniques in the process of design we can divulge in the manner that we experience space and testing its variations.

“About Us.” SUS. Services for the Underserved. Accessed April 15, 2019. https://sus.org/about-us/.

“About WIN.” WIN. Women In Need. Accessed April 14, 2019. https://winnyc.org/#trans.

Anderson, Deonna. “In New York, a Neighborhood Makes a Pre-Gentrification Plan.” Next City. Next City, June 27, 2017. https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/new-york-brownsville-jobs-businesses-arts-hub-economic-development.

Al-Kodmany, K. (2018). PLANNING GUIDELINES FOR ENHANCING PLACEMAKING WITH TALL BUILDINGS. ArchNet-IJAR : International Journal of Architectural Research, 12(2), 5. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.pratt.edu:2048/10.26687/archnetijar.v12i2.1493

Allen, Stan. “Mapping the Unmappable: On Notation”. Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation. London: Routledge, 2009 (40)

Bellafante, Ginia. “No ‘Inner City’ in Brownsville, Brooklyn, Just Overlooked Strengths.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 30, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/30/nyregion/nadia-lopez-brownsville-brooklyn.html.

Bloomer, Kent C., and Charles W. Moore. “Body, Memory and Architecture.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 71-74. Academy Editions, 1997.

“Brownsville Library.” Brooklyn Public Library, July 4, 2018. https://www.bklynlibrary.org/locations/brownsville.

Brueck, Hilary. “In Washington, DC, People Are Using Their Feet To Turn On The Lights.” Forbes. November 18, 2016. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hilarybrueck/2016/11/18/pavegen-energy-generatingsidewalk/#4d1ed3fc78da.

“Build New Subway Lines to Underserved Areas of the City.” The Fourth Regional Plan. Accessed March 5, 2019. http:// fourthplan.org/action/new-subways.

BUILDING FEATURE: PLANNING STRATEGIES. (1991). The Architects’ Journal (Archive : 1929-2005), 193(22), 38-41. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.pratt.edu/docview/1427112575?accountid=27668

Certeau, Michel De. “Spatial Stories.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 115-30. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

Certeau, Michel De. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 91-110. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

Certeau, Michel De. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life, translated by Steven Rendall, 91-110. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1984.

“Countermeasures and Safety Effectiveness.” Pedestrian & Bicycle Information Center. Accessed April 4, 2019. http://www. pedbikeinfo.org/topics/countermeasuressafetyeffectiveness.cfm.

Fitzsimmons, Emma G., and Tyler Blint-welsh. “Subway Delays Hit Low-Income New Yorkers the Hardest, Report Says.” The New York Times. The New York Times, June 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/nyregion/mta-subway-delaysincome-neighborhoods.html.

Gannon, Devin. “Interactive Map Identifies the New York City Neighborhoods Most Underserved by Transit.” Maps, Transportation. 6sqft, February 12, 2018.

Goodyear, Sarah. “A Very Different Reception for Bike Lanes in Brooklyn’s Poorest Neighborhood.” CityLab, April 18, 2014.

Green, Larissan Danielle. “Energy from Your Feet: When Sidewalks and Dance Floors Become Energy Sources.” TED Blog. June 05, 2013. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://blog.ted.com/energy-from-your-feet-when-sidewalks-and-dance-floorsbecome-energy-sources/.

Han, G. (2015). Futuristic transport. Metropolis, 34(8), 116-121. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.pratt.edu/ docview/1688475729?accountid=27668

Holl, Steven. “Anchoring.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 109-10. Academy Editions, 1997.

Hu, Winnie. “A Tired Brooklyn Transit Hub Is Finally Getting Attention.” The New York Times. The New York Times, November 26, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/26/nyregion/a-tired-brooklyn-transit-hub-finally-getting-attention.html?register=em ail&auth=register-email.

Hunter College, UAP. “BROWNSVILLE WORKS! a Strategic Economic Development Plan.” NYC: Hunter College Department of Urban Affairs and Planning Graduate Urban Planning Studio 2011-2012, 2011. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/community/uap-studio-brownsville-works.pdf

Libeskind, Daniel. “End Space.” In Theories and Manifestoes, edited by Charles Jencks and Karl Kropf, 274-75. Academy Editions, 1997.

Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Miller, Stephen. “Street Seats and Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville and East New York.” Streetsblog New York City, August 12, 2015. https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2015/08/12/street-seats-and-bike-lanes-come-to-brownsville-and-east-new-york/.

Nagel, Till. “United Cities of America.” Senseable City Lab. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/unitedcities/.

Nyhan, Marguerite. “Urban Exposures.” Senseable City Lab. 2016. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/urbanexposures/.

Polansky, Chris. “Will Brooklyn’s Freight Trains Get Rolling Again?” The Bridge. Brooklyn Business News, February 19, 2019. https://thebridgebk.com/will-brooklyns-freight-trains-get-rolling-again/.

Raby, Sam. “Interactive: Mapping New York’s Affordability Gap.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, December 21, 2017. https://ny.curbed. com/2017/12/21/16752942/affordable-housing-new-york-ami-interactive-map.

Ratti, Carlo. “The Copenhagen Wheel.” Senseable City Lab. 2009. Accessed October 21, 2018. http://senseable.mit.edu/ copenhagenwheel/index.html.

Reyna, Rikki, and Erin Durkin. “Brownsville Is Brooklyn’s Worst Neighborhood for Children Due to High Poverty, Lousy Access to Fresh Food and Day Care.” nydailynews.com. New York Daily News, April 8, 2018. https://www.nydailynews.com/ new-york/brooklyn/brownsville-brooklyn-worst-neighborhood-children-article-1.3009978.

Salomon, David. “Experimental Cultures: On the “End” of the Design Thesis and the Rise of the Research Studio.” Journal of Architectural Education65, no. 1 (November 22, 2011): 33-44. Accessed September 2, 2018.

Salomon, David. “Experimental Cultures: On the “End” of the Design Thesis and the Rise of the Research Studio.” Journal of Architectural Education65, no. 1 (November 22, 2011): 33-44. Accessed September 2, 2018.

Sanders, Alex. “Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville.” Bike Lanes Come to Brownsville | Community Solutions. Community Solutions, February 27, 2013. https://www.community.solutions/blog/bike-lanes-come-brownsville.

Stremple, Paul. “Billion Dollar Development Project Brings Affordable Units, Cultural Space to Brownsville.” BKLYNER, July 30, 2018. https://bklyner.com/brownsville-development/.

Sun, Feifei. “Brownsville: Inside One of Brooklyn’s Most Dangerous Neighborhoods.” Time. Time USA, January 30, 2012. http://time.com/3785609/brownsville-brooklyn/.

Tempey, Nathan. “Interactive Map Exposes NYC’s Sprawling Subway Deserts.” Gothamist. WNYC, July 12, 2016. http:// gothamist.com/2016/07/12/subway_desert_map.php.

V, Matt A. “New York’s LED Streetlights: A Crime Deterrent to Some, a Nuisance to Others.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 12, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/12/nyregion/new-yorks-led-streetlights-receive-a-lukewarmreception.html.

Velsey, Kim. “In Brooklyn, the Weeksville Neighborhood Stirs.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, July 14, 2015. https://www.wsj.com/articles/once-forgotten-weeksville-area-stirs-in-brooklyn-1436522402.

Warerkar, Tanay. “Brownsville Will Get Nearly 900 New Affordable Apartments.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, July 27, 2018. https://ny.curbed.com/2018/7/27/17621370/brownsville-brooklyn-affordable-housing-nyc.

Webster, George. “Green Sidewalk Makes Electricity -- One Footstep at a Time.” CNN. October 13, 2011. Accessed November 21, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2011/10/13/tech/innovation/pavegen-kinetic-pavements/index.html.

Wiggins, Glenn E. “Methodology in Architectural Design.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept. of Architecture. January 01, 1989. Accessed January 19, 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/14498.