Koopman Rare Art

The Kildare Candelabra Koopman Rare Art 12 Dover Street London W1S 4LL Tel. +44 (0) 20 7242 7624 info@koopman.art www.koopman.art 2 KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

Credits

Copyright © Koopman Rare Art

Edited and designed by Giorgia Zen

‘Dining with Nymphs and Satyrs in an Irish Olympiad’

written and edited by Dr. Tessa Murdoch

Candelabra photographs by Karen Bengall

Foreword

To our clients and dear friends,

Rarely do we, as dealers and collectors, see an object that reaches the heights of the Kildare Candelabra. We are proud to present these beautiful objects for the second time in our history. The French influence on English silver, particularly George II Rococo silver, has always been exciting. It shows a significant crossover in taste and how the Huguenots remarkably influenced great artistic work.

At Koopman Rare Art, we take pride in having what we consider the finest silver available, and in presenting this pair of candelabra, we have the finest of the fine.

Please enjoy the hard work put into this catalogue by Tessa Murdoch, Giorgia Zen and all our other colleagues at Koopman Rare Art.

Lewis Smith and Timo Koopman

3 4 KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

The Kildare Candelabra

DETAILS

London, 1744-5

Supplied by George Wickes

Engraved on both bases with the coronet and crest of FitzGerald for James Fitzgerald (172273) who succeeded his father on the 20th February, 1744 as 20th Earl of Kildare

Height: 43.2 cm, 17 in,

Weight: 9,1827.8 g, 293 oz 10 dwt

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

On spreading circular bases each raised on four splayed scroll and shell feet, cast and chased with a band of pearled ribbon-guilloches, the circular broad wells chased with panels of basket weave with anthemion on a matted ground between, rising to fluted knobs supporting waisted pedestals chased with pastoral trophies and each supporting a male and female satyr holding aloft a campana-shaped socket applied with garlands of oak leaves, each with three swirling sunflower branches supporting everted foliate sockets, with removable serrated nozzles.

PROVENANCE

James Fitzgerald, 1st Duke of Leinster

Edward Fitzgerald, 7th Duke of Leinster, and by descent Christie’s, London, 12 May 1926, lot 162 (Property of His Grace the Duke of Leinster)

Lionel Crichton of Crichton Brothers, London

Thomas Lumley, London

S.J. Phillips, London

Mrs. Ortiz Linares (1900-1980) (purchased 5 June 1951)

Thence by descent to her son George Ortiz (1927-2013)

Sotheby’s, New York, 13 November 1996, lot 8

The Al Tajir Collection

Koopman Rare Art, London

The Al Thani Collection

Koopman Rare Art, London

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

© KOOPMAN RARE ART

“Fine chais’d candlesticks & branches & nozils”

The primary inspiration for these exceptionally sculptural candlesticks associated with Thomas Germain was a candlestick by Juste-Aurèle Meissonier incorporating entwined cherubs in its spirally twisted stem. Engraved by Louis Desplaces (1682-1739) the design was published in Deuxième livre de l’oeuvre de J.A. Meissonnier, Chandeliers de sculpture en argent in 1734.

Aware of the growing taste for Rococo in France, Thomas Germain cleverly replaced the cherubs with sensuous figures of satyrs and let the candelabra arms blossom like lush foliage from the bough of a tree. This design succeeds thanks to the vibrancy and fluid rending of the figural and non-figural components. This visual effect despite the solidity of the silver makes these candelabra the ‘peak’ of Rococo production, in France known as Genre Pittoresque. This term complements the interests of Germain, who initially devoted himself to pictorial studies despite being born into a family of silversmiths. Germain’s harmonious satyrs display proportions and movement derived from Classical art, that Arcadian serenity makes the design of the candelabra both intellectually and visually exciting.

The design was highly successful and was adopted several times, the most famous example was made in 1732 and sent to the king of Portugal in 1757. Another pair, with Paris hallmarks for 1732-3, now at the Detroit Institute of Arts, was commissioned by an English patron, Sir Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart (1708-1770), for Ham House in Richmond. Two pairs bearing the mark of Germain’s son François-Thomas are also known. Thomas Germain’s pride in this piece is shown in Nicolas de Largillière’s 1736 portrait , in which the arm of the goldsmith is stretching backwards to reach for a single candelabra of this design.

Charles Frederick Kandler was the first silversmith to adopt this French design in England. However, the candelabra supplied by Kandler in 1738, now housed at the V&A, while inspired by Germain’s design, was not an exact copy. Kandler replaced the mythological satyrs with human figures. The design was later adopted by John Hugh Le Sage in 1744 for a pair of candelabra which represent the arms of George II.

The present pair, marked for 1744-5, was made by George Wickes to commission from the Earl of Kildare.

Wickes’ client, the Earl of Kildare, knew the work of Meissonnier and Germain. Despite his youth Kildare spent more than two years between 1737 and 1739 on the Grand Tour when he acquired a natural feeling for the genre picturesque. In 1744, he became the 20th Earl of Kildare and began to give full rein to his Rococo tastes. He became a collector of impeccable taste who, according to the accounts of the Reverend William Harris, could have eclipsed that of the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cumberland. Carton House, James FitzGerald, the Earl of Kildare’s house in Ireland, was said to be the finest in the country. If the pair of candelabra were ordered for Carton, they could not have enjoyed a better and more luxurious setting.

Equally, these spectacular candelabra could have been intended for Kildare House, outside Dublin . Work on that house started in 1745, the year of the delivery of the candelabra, which corroborates this hypothesis.

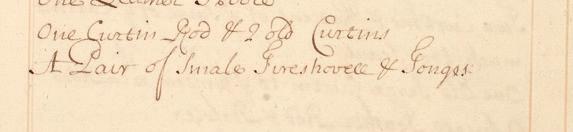

In Wickes’s ‘Gentlemen’s Ledgers’, there is incontrovertible proof that Kildare’s candelabra were delivered on May 27, 1745. However, there is no documentary evidence for those of Le Sage. On Lady Day (March 25), 1744, Wickes bought a second house, next door but one on Panton Street, and moved his workshop there from the first house, which he then used exclusively as a shop and home. The Kildare candelabra were made in the new workshop.

The ledger entry for the Kildare candelabra is brief and business-like. Two “fine chais’d candlesticks & branches & false nozils” appear against the date May 27, 1745. The Troy weight is given as 308 ozs. 13 dwts. The prime cost was £95 3s. 6d. which works out at approximately 6s. 5½d. per oz. To this figure was added a making or fashioning charge of 10s. per oz. Some idea of the expense involved in the interpretation of Germain’s design can be gained by comparing these figures with Wickes’s charges for the magnificent William Kent horse-head tureens made for Lord Montfort in 1744: here the basic cost was 6s. 2d. per oz. and the making charge 7s. 6d. per oz.

None of Wickes’s working drawings has survived, nor is there any trace of the eighteenth century equivalent of the modern worksheet. It is hardly likely that he would have made the candelabra from scratch. It is probable that Wickes moulded the candelabra directly from those supplied by Thomas Germain to Sir Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart (1708-1770), and which were brought to Ham House in Richmond.

However, given the dates of the George Wickes and John Hugh Le Sage candelabra, it is difficult to speculate which one was made first. On the one hand, the pair made by Le Sage was made for the Royal family, and may be the first version. If Le Sage’s version preceded that of Wickes, the Earl might have seen it and, with his predilection for the rococo, went posthaste to Wickes to order a copy.

However, George Wickes’ candelabra are slightly taller than the Le Sage ones. Given the moulding process would affect the size of the next model slightly, we can assume that the Thomas Germain model, measuring 44.5 cm., the first one, was followed by the George Wickes one, measuring 43.2 cm., subsequently followed by Le Sage’s version measuring 42.5 cm.

Then, the models and moulds for the Germain candelabra must have been carefully stored. Wickes’s successors, John Parker and Edward Wakelin, used them again in 1770 to make a further pair which is now in the Fairhaven Collection at Anglesey Abbey. The next known copy was fashioned under Paul Storr’s direction at Rundell, Bridge & Rundell in 1816 for the Duke of Leeds and differs slightly from Wickes’s version. George Wickes was also the supplier of the great dinner service made for Kildare between 1745 and 1747. It is very rare that such a service survives virtually intact. Known as the Leinster Service, it takes its name from the dukedom created for Kildare by George III in November 1766.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

7

8

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA 9 10

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA 11 12

Dining with Nymphs and Satyrs in an Irish Olympiad

by Tessa Murdoch

by Tessa Murdoch

Dining in Ireland

On 1st July 1747, the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Robert Jocelyn (c.1688-1756) hosted a dinner at his Dublin home in St Stephen’s Green to celebrate the anniversary of William III’s victory of the battle of the Boyne in 1690. Jocelyn entertained twelve peers of the realm with a menu consisting of more than forty separate dishes including badger flambé and fricassé of frogs. This information is recorded in Jocelyn’s dinner book that covers the years from 1740 to 1751 and includes table layouts and names of visitors. Amongst invited guests were the Earls of Bessborough and Kildare, the archbishop of Armagh and the Lord Mayor of Dublin. Such sophisticated feasting commanded a battalion of vessels in glass, silver and ceramics and the requisite silver cutlery all supported by linen napery. Contemporary inventories of great Irish households reveal the extent of such supplies; the 1818 inventory of Carton, the Kildare family home outside Maynooth, lists a Staffordshire dinner service and a French china service, the Steward’s Room housed some silver including ‘4 Silver candlesticks’, the Glass Pantry contained cut glass decanters and wine dinner glasses, there were linen damasks including those associated

with the Dublin house which the family sold in 1815. One pile of heraldic table linen is listed as Cromaboo; the war-cry which became the Kildare family motto and translates as ‘Crom for ever’ referring to their previous property, Croom Castle, Co. Limerick. Jocelyn’s menu reflects French influence both in the ingredients used and the desire to impress by serving rare, unmentionable or wild food in spectacular vessels. Service à la française meant that guests helped themselves to selected dishes. Such entertainments hosted by the elite Anglican ascendancy in Ireland competed with those given at Dublin Castle by the Viceroy, King George II’s representative, where State Dinners often consisted of thirty-four dishes and six removes with fourteen dishes of sweetmeats. Dining usually commenced at 3 p.m. and lasted for several hours. In winter, the room was lit with bees’ wax candles strategically placed in multi-branched candelabra which remained on the table throughout the meal. Like Jocelyn, many of his distinguished guests had great country houses in which they entertained lavishly and returned the Lord Chancellor’s hospitality.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

13 14

Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford. He trained as paintings conservator at the Tate Gallery and has practised as an artist and designer of historic interiors. His latest book, Birds, Bugs and Butterflies: Lady Betty Cobbe’s ‘Peacock’ China was published in 2019.

e d M und Joyce is lecturer at South East Technological University, Carlow. Since completing his M a in Historic House Studies at Maynooth University, he has published extensively on a wide range of topics relating to material culture and architectural history. His book, Borris House and Elite Regency Patronage was published in 2013.

John a da M son fsa has been publishing highly illustrated books in the decorative arts for more than twenty years.

nven T ories of four T een grea T Irish country houses, three Dublin town houses and one London town house yield remarkable insights into the lifestyle of leading families across Ireland and the households that supported them.

With startling directness, they record in detail the goods and chattels inherited, accumulated, or acquired for enjoyment or everyday use.

Two eight-page colour sections feature likenesses of most of the owners or householders of the properties at the time, including portraits by Pompeo Batoni, Michael Dahl, Thomas Gainsborough, Godfrey Kneller, Thomas Lawrence, Joshua

AJohn Adamson

c a M bridge johnadamsonbooks.com

The Earl of Kildare Estates

The value of inven T ories in charting how houses were arranged, furnished and used is now widely appreciated. Typically, the listings and valuations were occasioned by the death of an owner and the consequent need to deal with testamentary dispositions. That was not always so. The inventory for Castlecomer House, Co. Kilkenny, for example, was drawn up to make a claim following the house’s devastation in the 1798 uprising.

Mostly hitherto unpublished, the inventories chosen give new-found insights into the lifestyle and taste of some of the foremost families of the day. Above stairs, the inventories show the evolving collecting habits and tastes of eighteenth-century patrons across Ireland and how the interiors of great town and country houses were arranged or responded to new materials and new ideas. The meticulous recording of the contents of the kitchen and scullery likewise sheds light on life below stairs.

Itemized equipment required for the brewhouse, dairy, stables, garden and farmyard reflects the at times significant scale of the communities the houses supported and the remarkable degree of self-sufficiency at some of the demesnes. A comprehensive index facilitates access to the myriad items within the inventories, while the books listed at three of the houses are tentatively identified in separate appendices. A foreword, together with preambles to the inventories, sets the households in their historical context.

This book will appeal to historians of interiors, patronage, collecting and material culture, as well as to scholars, curators, collectors, creative designers, film directors, bibliographers, lexicographers and historical novelists.

AIn 1739, Robert, 19th Earl of Kildare acquired Carton House, Maynooth from Major General Richard Ingoldsby; it had previously belonged to the exiled Jacobite Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell (1630-91). The Kildares were an old English family, based at Maynooth Castle, who had held important offices in Ireland in medieval and Tudor times. Eclipsed during the 17th century they re-emerged in the 18th century to resume their social superiority. Carton was strategically placed fifteen miles west of Dublin. Kildare commissioned the leading architect Richard Castle or Cassel (1690–1751), who had settled in Dublin in the early 1730s, to rebuild the earlier house in the Neo-Palladian style.

Cassel was commissioned six years later to design a new family home in South East Dublin, Kildare House. That became Leinster House in 1766 when James Fitzgerald, 20th Earl of Kildare (1722-73) became 1st Duke of Leinster, then the unique Irish dukedom. Leinster House is now the seat of the Irish Parliament. At Carton, the Dining Room ceiling was modelled in 1739 in stucco by the Italian Lafrancini brothers, Paolo (1695-1770) and Filippo (1702-1779) with an elaborate figurative assembly representing the Courtship of the Gods. Painted stone colour, details were picked out in gold. They were paid £501 for this commission.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA GREAT IRISH HOUSEHOLDS GREAT IRISH HOUSEHOLDS Inventories from the Long Eighteenth Century Inventories from the Long Eighteenth Century foreword by toby barnard consultant editor t essa Murdoch consultant editor t essa Murdoch Contributors Toby arnard fba , is Emeritus Fellow in History at Hertford College, University of Oxford, and a specialist in the political, social and cultural histories of Ireland and England, c 1600–1800. leslie fi T zpaT rick was formerly the Samuel and M. Patricia Grober Associate Curator, European Decorative Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago. Tessa Murdoch fsa is an independent scholar. After forty years as curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum and Museum of London she is working with the British Museum on programme for Britain and Ireland to mark the bicentenary of Catholic Emancipation in 2029. Jessica c unningha M completed her doctorate at Maynooth University in 2016. Her research has been published in Irish Architectural and Decorative Studies the Journal of the History of Retailing and Consumption and Silver Studies: The Journal of the Silver Society r ebecca c a M pion graduate of the University of Cambridge, completed doctorate at Maynooth University in 2012. She is a teacher, occasional lecturer and independent scholar with particular interest in material culture, collecting, display and the Grand Tour. a lec c obbe was educated in Ireland and at

Reynolds, as well as the Irish artists Hugh Douglas Hamilton and Charles Robertson. Printed in Italy ron T Willia M van der h agen An extensive view of Carton House, County Kildare, with Maynooth in the distanc © 2017 Christie’s Images Limited back M peo a oni Robert Clements, 1st Earl of Leitrim 1754 © Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA Kilkenny Castle, An Inventory of his Grace Duke of Ormonds Goods Att Killkenny Taken, p. 5. Ormonde Papers courtesy of the National Library of Ireland Tessa Murdoch (ed.) Noble Households: EighteenthCentury Inventories of Great English Houses ‘This is a fascinating book, and not just for the specialist in English eighteenth-century houses. It is to be hoped that more inventories will now be published as they are the bedrock of the understanding of the taste of a particular period.’ Times Literary Supplement a lso of in T eres John Adamson, 2006

15

CARTON HOUSE, COUNTY KILDARE, DETAIL FROM A VIEW BY WILLIAM VAN DER HAGEN, WITH MAYNOOTH IN THE DISTANCE, OIL ON CANVAS, C.1730 ©CHRISTIE’S IMAGES LTD. COVER OF ‘ GREAT IRISH HOUSEHOLDS’ DESIGNED BY PHILIP LEWIS

16

This sophisticated double height interior was the setting for lavish hospitality. The laying of the dinner tables complemented the virtual company of gods and goddesses projecting from the ceiling above. Paired celestial lovers Venus and Mars, Neptune and Ceres and Apollo and Daphne are precariously placed on pillows of cloud that overlap the cornice. Above their heads, cavorting putti swing their legs over oak garlands. The craftsmen responsible for this sculptural assembly came from Ticino, close to the Swiss border with Italy. Their figures are modelled on prints by Pietro Aquila published in about 1685 after leading Italian artist Giovanni Lanfranco’s ceiling The Council of the Gods in the Gallery of the Villa Borghese, Rome, painted in 1624.

The architecture and interiors at Carton reflect the Kildare family’s engagement with European art and architecture, as successive generations visited Italy on the Grand Tour.Although a ‘Sett of Mahogany Pillar Tables (Consisting of 8)’ was recorded in the 1818 Carton inventory, that is when a new dining room was being built to the designs of architect Richard Morrison. Eighty years earlier there were probably two tables seating eight or ten people each as recorded at nearby Castletown, where Kildare was later to redesign the dining room for his sister-in-law Louisa Conolly in the 1760s.

In February 1744 James Fitzgerald succeeded his father as 20th Earl of Kildare. He promptly

acquired furnishings worthy of the inherited palatial family homes in Dublin and Maynooth. In anticipation of hosting lavish parties, Kildare commissioned from London-based George Wickes, royal goldsmith, a substantial dinner service. (When this sold at auction in 2012, it achieved a world record).

For the marble-topped mahogany sideboards and service of wine, Kildare added to the silver wine cistern supplied by Dublin goldsmith Thomas Sutton for his father in 1727, a silver wall fountain by Robert Calderwood, 1754, also from Dublin. This proudly displays the earl’s coronet as its lid whilst the spigot emanates from a shell picking up on a recurring motif on the dining room stucco ceiling. Both fountain and cistern bear the coat of arms of the 19th Earl and his wife Mary, daughter of the Earl of Inchiquin, the cistern was later used as a centrepiece on the dinner table, where it was flanked by two pairs of three light silver candelabra inspired by those invented by leading Paris goldsmith Juste Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750), designer to the French King, Louis XV. Meissonier’s collected designs for silver were published as a set of 118 plates by Gabriel Huquier from 1742-51. But many of the plates had previously been published in smaller sets.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

17

PLASTER CEILING OF THE SALOON (FORMERLY THE DINING ROOM) CARTON, COUNTY KILDARE ©JACQUELINE O BRIEN

18

NEPTUNE AND CERES, DETAIL OF THE CEILING BY PAOLO AND FILIPPO LAFRANCINI, CARTON, COUNTY KILDARE © COUNTRY LIFE

KOOPMAN RARE ART

LANFRANCO’S ‘THE COUNCIL OF THE GODS’, CEILING OF THE GALLERY, VILLA BORGHESE, ROME, ENGRAVING, PIETRO AQUILA, 1685 © COUNTRY LIFE

19

THE LEINSTER DINNER SERVICE, SILVER, SUPPLIED BY GEORGE WICKES, 1745-6 ©CHRISTIE’S IMAGES LTD.

JUSTE AURÈLE MEISSONNIER’S DESIGN FOR FIGURATIVE CANDELABRA, ETCHING, LOUIS DESPLACES, PARIS, 1728 © VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

The design for the Candelabra

Kildare’s sophisticated candlesticks with stems formed with figures of a nymph and satyr were supplied by London goldsmiths, one pair, those illustrated here, were marked for George Wickes; the other for John Hugh Le Sage. Wickes’s Gentleman’s Ledger records delivery to the Earl of Kildare on 27 May 1745: ‘fine chais’d candlesticks & branches & false nozils,’ 308oz. 12dwt. at a cost of the silver (£95 3s. 6d.) and fashioning (10s. per oz.), totalling £154.’ The figurative stems spiral with a fluidity which denies the rigid silver with which they are formed; the branches spring from the stem with effortless verve. The domed bases, chased with panels of basket-weave and reserves of shells on a matted background, rest on leaf-flanked shell feet. The oak-festooned sconces are chased with rococo cartouches. The detachable three-light branches with swirling berried foliate arms support multiple-petalled sunflower sconces. The figures of the nymphs pursued by satyrs provide a Rococo complement to the Baroque stucco gods and goddesses on the Carton dining room ceiling. These candelabra are identical to a pair that French royal goldsmith Thomas Germain made in Paris in 1732-3 for the 4th Earl of Dysart (1708-1770) for use at Ham House, Richmond. Now in the Detroit Museum of Fine Arts as part of the Firestone Collection, Kildare’s London-made versions may have been copied from those owned by Lord Dysart. In the

1736 portrait of Germain with his wife painted by Nicolas de Largillière in Paris, this candelabra model is proudly displayed in the background. In 1748 Germain produced a gold candelabra with sockets based on the calyx and petals of the sunflower for Louis XV. Germain supplied three other similar pairs; two pairs for the PenthièvreOrléans service, 1733-4 (one pair were recorded in a private collection; the location of the other pair is currently unknown). Another pair delivered in 1757 in Lisbon for King Joseph I had feet marked for Thomas Germain, 1734-5 and all other parts with marks for François Thomas Germain, 1756-7. (Formerly in the collection of George Ortiz, these were sold Sotheby’s 13 November 1996). Published in Paris in 1738-9 in ‘Livres de Chandeliers de Sculpture en Argent’ engraved by Gabriel Huquier, candlesticks to this design were ordered by Francophile Duke of Kingston from Meissonnier in Paris in 1737. Other versions produced in London in the 1740s were marked by Paul de Lamerie and Thomas Gilpin and in the 1750s by Edward Wakelin. This successful design remained in demand in Britain and Europe. Parker & Wakelin (Wickes’ successors) made a pair in 1770, now in the Fairhaven Collection at Anglesey Abbey. A further pair was supplied by Paul Storr for Rundell, Bridge & Rundell in 1816 for the Duke of Leeds.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

21

THOMAS GERMAIN AND HIS WIFE IN THEIR PARIS WORKSHOP, OIL ON CANVAS, NICOLAS DE LARGILLIÈRE, PARIS, 1736

© CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN MUSEUM, LISBON

In 1747 James Fitzgerald married Emily, younger daughter of the 2nd Duke of Richmond, a leading presence at the Hanoverian court. Emily grew up at Richmond House, Whitehall and at Goodwood, West Sussex, under the mature eyes of her French great grandmother Louise de Kerouaille, a former mistress of Charles II. Emily took a lively interest in art, contributing to the decoration of a shell house at Goodwood, and later overseeing the creation of its equivalent in the grounds at Carton.

The Kildare Candelabra thus epitomize FrancoBritish Rococo taste. Forming the human figure into the stem of a candelabra reflects the

contemporary focus on life drawing in the London and Paris Art Academies. Yet only the informal St Martin’s Lane Academy permitted drawing from the female model; the novelty had attracted the interest of the Prince of Wales, future George II, in 1722. Such opportunities were only introduced in Continental Europe after the French Revolution.

The design and candlesticks modelled by George Michael Moser, circa 1740, now in the V&A, incorporating single figures of Apollo and Daphne, reflect his teaching in St Martin’s Lane where his fellow tutor was the French-trained sculptor Louis François Roubiliac. Although separated as two

candelabra, the conceit of Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne unites the pair.

By 1743, Roubiliac was providing figurative models for bronzes to furnish sophisticated musical clocks, including interactive figures of Hercules and Atlas and seated figures representing the Four Grand Monarchies, Europe, Persia, Africa and America. Roubiliac may have also provided models for the figures of Venus and Adonis which adorn the silver sauceboats supplied by Nicholas Sprimont for Frederick, Prince of Wales’s Neptune dinner service.

By 1745, the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory was established by Liège goldsmith Sprimont in partnership with Dieppe jeweller Charles Gouyn. Chelsea porcelain figures were modelled and cast in the round as decoration for the dining table, replacing sugar sculpture that had served a similar purpose in the 17th century. In silver, the burnished surface of the sculpted human figures reflected the candlelight and provided a lively diversion for those dining with Kildare at Carton or Leinster House.

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

CANDLESTICKS WITH FIGURES OF APOLLO AND DAPHNE, SILVER, PAIR, C.1740 ©VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

23

DESIGN FOR A CANDLESTICK, PEN INK AND WASH, G.M.MOSER C.1740 ©VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

Tessa Murdoch

HERCULES AND ATLAS, BRONZE, L.F.ROUBILIAC FOR CHARLES CLAY, TEMPLE OF THE FOUR MONARCHIES, MUSICAL CLOCK, LONDON, 1743 KENSINGTON PALACE © HM CHARLES III

EUROPE, BRONZE, L.F.ROUBILIAC FOR CHARLES CLAY, TEMPLE OF THE FOUR MONARCHIES, MUSICAL CLOCK, LONDON, 1743 KENSINGTON PALACE © HM CHARLES III

24

PERSIA, BRONZE, L.F.ROUBILIAC FOR CHARLES CLAY, TEMPLE OF THE FOUR MONARCHIES, MUSICAL CLOCK, LONDON, 1743, KENSINGTON PALACE © HM CHARLES III

KOOPMAN RARE ART THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

25

NEPTUNE CENTREPIECE, SILVER, PAUL CRESPIN AND NICHOLAS SPRIMONT FOR FREDERICK PRINCE OF WALES, LONDON, 1744 © HM CHARLES III

SAUCEBOAT, SILVER, FEATURING FIGURE OF ADONIS, NICHOLAS SPRIMONT FOR FREDERICK, PRINCE OF WALES, LONDON, 1743 © HM CHARLES III

SAUCEBOAT, SILVER, FEATURING FIGURE OF VENUS, NICHOLAS SPRIMONT FOR FREDERICK, PRINCE OF WALES, LONDON, 1743 © HM CHARLES III

Further Reading

Christopher Hartop, The Huguenot Legacy, English Silver 1680-1760 from the Alan and Simon Hartman Collection (1996), pp126-131

Sotheby’s New York, Royal French Silver: The property of George Ortiz, Catalogue, (November 13, 1996), p 82-98

Christopher Hartop, Royal Goldsmiths: The Art of Rundell & Bridge 1797-1843, Koopman Rare Art (London, 2005), p 124

Elaine Barr, George Wickes, Royal Goldsmith, 1698-1761, (London, 1980), pp. 84-86

John Adamson, Great Irish Households: Inventories from the Long Eighteenth Century (John Adamson, Cambridge, 2022)

Toby Barnard, The Kingdom of Ireland, 1641-1760 (Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2004).

John Cornforth, ‘Sources for Irish Stuccowork’, Country Life, vol. 185, (4 April 1991), p. 100

Martina Droth, Taking Shape: Finding Sculpture in the Decorative Arts, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds and J.Paul Getty Museum, (Los Angeles, 2008)

Alison Fitzgerald, ‘Desiring to look ‘Sprucish’, Patrick Cosgrove, Terence Dooley, Karol Mullaney-Dignam ed., Aspects of Irish Aristocratic Life: Essays on the Fitzgeralds and Carton House, University College Dublin Press, (Dublin 2014), pp.118-127

Peter Fuhring, Just-Aurèle Meissonnier, un génie du rococo (Allemandi, Turin, 1999).

The Knight of Glyn and James Peill, Irish Furniture, Yale University Press, (New Haven and London, 2007)

William Laffan and Christopher Monkhouse, Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 16901740, Art Institute of Chicago, Yale University Press, (New Haven and London) 2015

Patricia McCarthy, Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland, Paul Mellon Centre, Yale University Press, (New Haven and London, 2016)

Joseph McDonnell, Irish Eighteenth-century Stuccowork and its European Sources, National Gallery of Ireland, (Dublin, 1991)

Tessa Murdoch, ‘Louis François Roubiliac and his Huguenot connections’, Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London (XXIV, no.1, 1983), pp.26-45

Tessa Murdoch, ‘From the Gate to the Hearth: Metalwork at Ham House’ in Ham House, 400 years of collecting and patronage, ed. Christopher Rowell, Yale University Press, (London and New Haven, 2013), pp.232-247

Tessa Murdoch, ‘Elite Gift Exchange: A Royal Christening gift for Lady Emily Lennox in the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection and Christening Gifts in the V&A Collections’in Studies in Irish Georgian Silver ed. Alison Fitzgerald at the National University of Ireland at Maynooth, Four Courts Press, (Dublin, 2020) pp.64-77

Tessa Murdoch, A Performance for the Service of a Table’: New Light on Eighteenth Century Dining,’ Getty Research Journal (no. 14, 2021) pp.181-190

Jacqueline O’Brien and Desmond Guinness, Great Irish Houses and Castles (London, 1992)

Michael Snodin edit. Rococo: Art and Design in Hogarth’s England, V&A, (london, 1984)

Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa and Sarah Lennox 1740-1832, (London, 1985)

KOOPMAN

THE KILDARE CANDELABRA

RARE ART

12 Dover Street London W1S 4LL, United Kinkdom info@koopman.art +44 (0) 20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art

by Tessa Murdoch

by Tessa Murdoch