UFLPA's BIG IMPACT

The U.S. forced labor ban is bringing visibility and accountability to the supply chain— though its implementation and circularity repercussions are in the spotlight

VOLUME THREE SPRING 2024

Fashion’s Big Shift

Fifty years ago, when I started in this business, the garment factories were all located in the Western hemisphere. American factories owned American fashion brands and fabric vendors sold to the garment factories whose products they sold to department stores. No store wanted to see fabrics.

Levi Strauss, Wrangler and Lee all had their own factories and one of their challenges in expanding to new countries was the investment (capital and management) in new garment factory locations. I believe Canada was Levi’s first foreign jean factory. Foreign denim mills in Italy or Japan were built to supply the big three as they expanded internationally.

Fast forward to the days when brands started calling themselves marketing companies, ditching their local garment factories and relying primarily on foreign factories to produce for them. Faded Glory and Brittania were two of the first companies that entered the jeans industry factory-less, producing their products in what was then labeled as “the British Colony of Hong Kong”.

Others followed rather successfully, including Jordache, Sasson, Sergio Valente, Gloria Vanderbilt, and so on. Finally, even Levi’s and the other older jeans brands started to produce in Asian factories they did not own.

Now almost 40 years later, we have returned to “GO” and the time is ripe for the jean factories to own the brands that are every day relinquishing the responsibilities and skill in owning a brand.

More and more we hear brands are relying on their factories for design, for financing, for production and logistics— not just wash development and amazing fabric development.

One way to look at all that’s going on is to lament change and wistfully force yourself to accept the new world. But another perspective is to see the opportunity. Now more than ever, Kingpins exhibitors have to be as creative as they can. They need to forget how it used to be and start to give the customers direction and lead fashion, rather than follow it. It’s time for mills and garment factories to hire the best in the industry.

Yes, we are all caught up in a commodity-driven world. Yes, price is the dominant factor of our existence — but fashion is never going away. If we make things people love, price can turn into the B factor — which is what it should be. Consumers need to be fans the way the New York Yankees have fans or Manchester United has fans. Price does not make fans. Great products do.

Best,

Andrew Olah Founder, Kingpins

6 Blue Blood

Jerome Dahan, founder of Citizens of Humanity and 7 for All Mankind, on the thrill of building brands and the bewildering state of the market.

9 Intentions vs. Impact

As the two-year mark approaches and stakeholders push for more, UFLPA’s effectiveness depends on who you ask.

15 Beat the Clock

Many of the denim industry’s 2025 sustainability commitments are not aging well. How can we accelerate ahead of 2030?

18 Egypt's Denim Evolution

Diverse sourcing is a necessary industry trend and investors see Egypt as the next denim production hotspot.

23 Legler's Legacy

One Italian denim mill that saw a boom and then bust as the denim industry’s fate evolved with the rise of jeans and the introduction of free trade

29 On the Show Floor

Your first look at the top news, notes and highlights from Kingpins Amsterdam exhibitors.

4 KINGPINS QUARTERLY

VOLUME THREE, SPRING 2024

FOUNDER'S LETTER

KINGPINS QUARTERLY.COM ANDREW OLAH Founder CALETHA CRAWFORD Editorial Director COLIN BEAUCHEMIN Creative Director VIVIAN WANG Managing Director/ Global Sales Manager GORDON HEFFNER Director, Media & Retail FOR ADVERTISING INQUIRIES Contact Vivian Wang at vivian@kingpinsshow.com

BLUE BLOOD

Jerome Dahan, founder of Citizens of Humanity and 7 for All Mankind, on the thrill of building brands and the bewildering state of the market.

If anyone can shed light on what’s happening in denim today, it would be Jerome Dahan. For the founder of both Citizens of Humanity and 7 for All Mankind the focus on price points is undermining the industry, allowing denim to drift too far away from the creativity that propelled brands like his to success.

Andrew Olah, founder of the Kingpins trade show and the Olah Inc. agency, has known Dahan for decades and credits him for bringing innovation to what had been a stale category. “Part of it is timing. Timing is everything. He had the perfect comprehension of the customer at the

moment,” Olah said. “There was no slub denim, no differentiation. There were a few at the time: AG, Paper [Denim & Cloth], True Religion and Paige, each with a different take. It was a moment when jeans went from $50 to $180.”

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 6

KPQ DENIM MASTERS

Those pricey jeans helped make denim fashion. “That was a huge moment of history where everything changed,” Olah said. “It’s difficult to replicate now. No one understands the consumer and the consumer doesn’t have a propensity to want to wear jeans.”

Leveraging experience at his first company, Circa, as well as a stint at Lucky Brand, he launched 7 for All Mankind with Michael Glaser in 2000. Next, he created Citizens of Humanity in 2002, which he said in some ways was an even bigger feat. “When I started Citizens, it was a challenge because I left 7 for all Mankind, and I was like, ‘Okay, am I gonna be able to do it again? It’s like, you don’t know until you do it.’” And he did.

Here, Olah and Dahan sit down to discuss the industry, how it’s evolved and their shared love of denim.

AO: What was it that made you think that it was no big deal to go from being someone’s designer to being your own company? How was that mentally?

JD: I say it happened late. Late and not late because if you remember I had Circa that I started like 25 or 30 years ago. And that was just because I was very inspired by things that were not in the market. At this time, I was looking at the European market, and I was like, ‘Europeans are advanced. The U.S. market is not yet working on washes, development, fabrications, fit and all those kinds of things.’ So, I knew when I closed Circa how tough

THE DAY [BARNEYS] CLOSED, I KNEW THE MARKET WAS GOING TO CHANGE.

it was to have a company, and when I left Circa I worked for Lucky Brand. And working for Lucky Brand, I had a green light and I was doing a lot more than design. Gene Montesano was living in Santa Barbara so he was coming in once a week. I was spending a lot of time with Barry Perlman, and I was working with production. I was working with everything and that opened my eyes because I was doing it for a company but I was doing 80 percent of the work or 75 percent of the work. So that helped me a lot. So it was like, ‘Okay, if I start something, I just have to choose the right people to start with to help me, to surround myself with the right people and being able to build a company.’

Did I know that I was building something like 7? No, I didn’t know. And I tell you the truth, when I started 7, we opened, I would say, 20 stores or 25 stores back East and in Europe and in France. But when I shipped the product, right away I knew that I had something because the product was selling out so fast. So, I knew that I had something that meant something to a lot of people. Maybe a few weeks later one morning I go to King’s Road Cafe and I see these two girls [who] are wearing 7 for All Mankind. And I’m like, this is big. If you can see your jeans on someone, it means they’re really starting to sell. And that got me super excited.

And in the same time, I remember there was a store in Paris and Los Angeles—I can’t remember the name—but… they didn’t carry jeans. And I came back from Europe and I was driving at night on Robertson, and I saw the store and saw my jeans in the window. I was like, it means something. It means that the market is open. The contemporary market is opening. There was one company before that that did a very good job. It was Earl Jeans. I don’t know if you remember Earl.

AO: Totally because it’s actually a funny story. I went to see Earl in the late… I don’t remember what year but they told me that I would never be successful because all my fabrics had slubs, and they said slubs would never take off. The best jean company, the hottest jean company in Los Angeles rejected me for the very nature of the best product that I have to sell. And here we are all these years later and slubs were everywhere, and [the store brand is] gone.

JD: Yeah, exactly. Some people think they know, and at the end of the day, they don’t get it. They don’t make the research.

AO: Are there any jeans out there in the marketplace that you like because our industry is kind of struggling? It’s really commoditized for the most part. Is there anything that you like for women, especially. Women’s is worse than men’s, I think.

JD: Women’s is worse than men’s because men’s didn’t enter the market like women’s did over the past 20 years. Men’s was the first guys to make jeans and then women’s became popular. And after being popular, there were brands left and right that opened up, and jeans didn’t mean really anything anymore. It was about price point, and it was about picking a basic, and I didn’t even understand the market after.

AO: Do you understand it right now? Because I don’t.

JD: I don’t. I understand that people are not creative and because the people are not creative, they work with price point.

AO: When you started your brands there were all these stores in Los Angeles like Kitson and Fred Segal. They’re all gone. Why do you think they’re gone, and what’s going to happen after that?

JD: Stores like Kitson wanted to make more money [on] the product. And when you think about that..., you don’t think of a product anymore, and a lot of brands that were sold in those stores didn’t give the image of the store anymore. And business became tough, very tough, especially for department stores. Look at Barneys. Barneys was the first department store to close, and [I knew] this is going to be a big deal… Barneys was a store that was a landmark. People used to come to LA and where did they go? They’d go to these kinds of stores. The day it closed, I knew the market was going to change.

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 7

TEXTIL SANTANDERINA INTRODUCES YARN DERIVED FROM PINEAPPLE FIBER

Vertically integrated fabric manufacturer Textil Santanderina partnered with Ananas Anam to develop new sustainable pineapple fiber-based products.

Spanish textile maker Textil Santanderina has developed a new Piñayarn® product that relies on fibers from pineapple-plant waste. The new pineapple leaf fiber—or PALF—offerings were developed through a collaboration with Ananas Anam and will be introduced during Kingpins Amsterdam, April 24-25, at SugarFactory.

“We are very happy with the result, soft touch, and beautiful, natural appearance and behavior very similar to the linen fiber,” said Laura Torroba, head of the fashion department for Textil Santanderina. “Until now, they were marketing a type of vegan leather alternative named Piñatex®, made with pineapple fiber, with which they have had a lot of success, and now they want to take another step in collaboration with Textil Santanderina to produce a yarn and fabrics made from pineapple fiber and their blends.”

The vertically integrated Textil Santanderina boasts its own spinning, weaving, dyeing, printing, coating and finishing. It is also known for its innovative approaches to responsible textile development, which made Textil Santanderina perfectly positioned to work with Piñayarn® and Piñatex’s® London-based parent company Ananas Anam, whose European production center is located in Spain. At more than 100 years old, Textil Santanderina counts European and U.S. brands among its clients and boasts an annual capacity of more than 27.3 million yards.

“On one hand, we collaborate with our customers with their sustainability strategies within the circular economy, to join forces and increase the use of recycled fibers inside our 360 Degrees Sustainable policy,” explained Torroba. “And, on the other hand, we guarantee through Textile Exchange or Global Organic Textile Standard certifications, the transparency and traceability of

our processes, with an open supply chain, real and certified from all angles.”

Piñayarn’s® supply of pineapple leaves is a byproduct of farming the fruit. Textil Santanderina uses this resource as the foundation for the plasticfree, vegan, 100 percent plant-based Piñayarn®. No additional land, water or pesticides are required to cultivate the raw material. Piñayarn® is recyclable, biodegradable and compostable. The traceable production process is water and energy efficient, and uses zero harmful chemicals. For every 2 lbs. of yarn produced, the equivalent of up to 13 lbs. of CO2 is prevented from being released into the atmosphere, according to studies conducted by the company that produces this fiber.

“After the pineapples have been harvested for food, the leaves of the plant are waste and are either left behind to rot or are burned,” Torroba said. “By creating new materials from these waste leaves, Ananas Anam has saved 264 tons of CO2 from being released into the atmosphere in 2020 alone—this is equivalent to charging more than 33 million smart phones!”

Textil Santanderina is also fulfilling important social commitments with its Piñayarn® products. Through its work with Piñayarn®, Textil Santanderina helps workers develop skills, promotes a safe workplace and empowers women.

“In addition to saving CO2 , using the pineapple leaves to create textiles also provides a second stream of income to the pineapple farmers, creating more jobs in rural communities,” said Torroba. “This fiber was developed for use as a sustainable alternative to mass-produced materials, offering a better choice for a better future. It offers a high-performing, quality plant-based textile solution without compromising the health of people and the planet.”

Piñayarn’s® ability to yield textiles with a luxurious hand and alluring appearance position it as an ideal sustainable option for brands and fashion houses that serve the luxury consumer. According to Torroba, Textil Santanderina’s clients are attracted to the company’s commitment to producing goods that are not only traceable to ensure authenticity but also made responsibly regarding their environmental and social impacts.

“More and more of our customers are concerned about the environment and ask us to offer them real sustainable solutions so they can offer these products to their customers,” revealed Torroba. “In this case, the pineapple fiber is a global social, environmental and product response.”

ADVERTISEMENT KINGPINS QUARTERLY 8

INTENTIONS VS. IMPACT

As the two-year mark approaches and stakeholders push for more, UFLPA’s effectiveness depends on who you ask

BY DEBRA COBB AND CALETHA CRAWFORD

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act has had a profound impact on U.S. brands, retailers and sourcing partners, especially in the denim segment. The law, which prohibits goods originating wholly or in part from China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) from entering the U.S., places the burden of proof on importers— a fact that’s proven costly and onerous for this traditionally opaque industry. In response, brands and retailers continue to upend supply chains, standup new technology and shore up reporting. Meanwhile, calls for tighter controls at home and additional legislation in the European Union are raising questions around UFLPA’s enforcement and effectiveness.

“There is a degree of fear in the brand community, translated into sourcing trying very hard to avoid Xinjiang,” said Robert Antoshak, partner and consultant with the Gherzi Textile Organization. “But it’s like trying to stop water going through a screen door.”

From June 2022 through January 2024, the CBP scrutinized 1,275 shipments of suspect apparel, footwear, and textile goods with a total value of $51.13 million. Of that number, 333 shipments were released; 694 shipments were denied; and 248 shipments are pending.

“Our members make every effort to identify, prevent, and eradicate slave labor,” said Nate Herman, senior VP/policy for the American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA). “They are working hard to identify the source of their cotton.”

That’s a tall order given the length and complexity of most supply chains and the fact that cotton fibers can end up comingled at several points in their textile journey.

9 KINGPINS QUARTERLY

FEATURE

Adding up the costs

“The UFLPA is unique and it kind of shocked the industry because you need to prove yourself of being innocent,” said Pauline God, policy and partnership manager for traceability software provider TrusTrace. “The necessary documents then for conducting this analysis includes everything from payment records, shipping records, production records, all kinds of information.”

For those who have had goods detained, it doesn’t take long for costs to mount.

Herman explains that while CBP allows importers only 30 days to petition for release when they believe CBP is incorrectly detaining a shipment having no connection with XUAR, the agency can take up to twelve weeks to reach a decision.

“For seasonal products such as apparel, this is a big problem,” he said. Storage fees for containers awaiting CBP’s decision can also add up. Both reasons can prompt importers to re-export their goods to another country—or even abandon their shipment.

“The CBP is overwhelmed with the hundreds of documents they require importers to file as part of their petition,” Herman said. “CBP is looking for documentation that goes all the way back to the cotton bale. Many companies can’t get past the yarn spinner.”

While brands and retailers are frustrated with the UFLPA requirements, the U.S. textile industry thinks it does not go far enough. The National Council of Textile Organizations (NCTO), along with members of Congress, are calling for tougher enforcement. In January, the U.S. House of Representatives Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sent a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas, urging expansion of UFLPA’s Entity List of Chinese companies suspected of dealing in forced labor products.

The letter from the Select Committee also addressed the de minimis provision, which allows importation of goods less than $800 direct to consumers, without tax or duty. The loophole has facilitated the growth of Chinese fast-fashion online retailers such as Shein and Temu, allowing them to dodge UFLPA compliance.

But these calls for stricter enforcement have come at a time when CBP’s actions have already signaled that the agency is stepping up its efforts, said Ethan Woolley, account executive at risk analytics provider Kharon during a webinar the company hosted in October.

“The UFLPA entity list, as first conceived 15-16 months ago, contained companies that were either taken from being on the BIS Entity List, because of their complicity in human rights violations in Xinjiang, or already were companies with WROs being enforced against them by CBP. These companies that have been added more recently aren’t coming from those existing government lists,” he said, adding he expects to see the entity list continue to expand per the Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force’s mandate. Woolley also pointed

to a “significant increase in CBP funding” for the enforcement of UFLPA as cues to CBP’s ramp up.

Making traceability a priority

Increased scrutiny means the industry will need to be even more vigilant.

“Physical forensic testing is important. You can’t rely solely on digital tracking or documentation,” said MeiLin Wan, VP Textile Sales for Applied DNA Sciences, Inc. Applied DNA combines multiple technologies in its CertainT Supply Chain program: tagging raw materials with molecular DNA, testing for identity throughout the supply chain, and tracking the chain of custody.

“The CBP may not necessarily utilize all the tech

INTENTIONS VS. IMPACT KINGPINS QUARTERLY 10

credit: Olivia Repaci opener credit: Kuzzat Altay on Unsplash

that’s available,” said Wan, who attended last year’s Forced Labor Technical Expo, where CBP introduced a select group of service providers to assist importers with their rebuttal documentation. “They prefer to track documents digitally. If they are using specific tech and tools, they should disclose them to the industry.”

The Department of Homeland Security and CBP recognize Oritain, which uses isotopic testing to create identifiable fingerprints for products that are traceable through the supply chain to their origin.

CBP also contracted with Kharon, giving CBP access to Kharon’s global risk analytics platform. However, China has since sanctioned the company and frozen its assets, though the company calls this “symbolic” given it has “no presence in China.”

Legitimate off-shore suppliers of denim textiles and apparel are using a number of tagging and tracing technologies to certify their yarns and fibers.

Triarchy, a high-end responsible denim label from Los Angeles, uses certified organic cotton, as well as recycled and regenerative cotton fibers, and Candiani’s plastic-free stretch denim. Third-party auditor Renoon supplies transparency to the brand via embedded QR codes.

The Renoon platform maps and verifies the supply chain via blockchain from raw material sources. According to co-founder/creative director Adam Taubenfligel, Triarchy does not use fibers that would run afoul of UFLPA.

Kipaş, a vertically integrated textile company in

TRACEABILITY SYSTEMS ARE WORKING, BUT HOW DO WE MAKE THEM MORE ACCESSIBLE TO FARMERS, MERCHANTS, AND BROKERS?

Turkey, spins its own yarn with fibers of regenerative Good Earth Cotton, grown in Australia and certified via FibreTrace. The technology embeds non-toxic, luminescent pigments into the fibers, which are scanned and read with a hand-held device.

“The benefit of initiatives such as the UFLPA and the initiatives that are going on in Europe are that they put the pressure on for brands to move faster than they may otherwise have done in terms of investing in these traceability initiatives and platforms,” Parker said.

“Traceability is a good thing,” the AAFA’s Herman said. “Visibility assists sustainability goals, such as reduction of CO2e and harmful chemicals.”

“Traceability systems are working, but how do we make them more accessible to farmers, merchants, and brokers?” asked LaRhea Pepper, co-founder and former CEO of Textile Exchange. “It’s going to require a dynamic shift in the industry. You can legislate, but that doesn’t make it so. It must be an industry solution.”

Shannon Mercer, CEO of FibreTrace, agrees, stating the industry needs to take a lesson ahead of broader pending environmental and social regulations, which will call for more of the same. “Achieving compliance requires a combined effort and a united goal across diverse stakeholders. It also necessitates robust enforcement mechanisms, transparency measures, and capacity-building initiatives to address systemic issues effectively.”

Mercer hopes that lawmakers have learned from their experience with UFLPA. Overall, he said, there’s a “rising need for clear standards and guidance, the importance of enforcement and accountability, and the need to invest in technologies that will assist.”

Measuring the success of the UFLPA

While UFLPA will likely have many net benefits for the industry, its impact on forced labor specifically is hard to pinpoint. Imports from China declined in 2023, still it is difficult to know if anything has changed for the Uyghurs.

According to the South China Morning Post, China’s

exports of all commodities to the U.S. fell by 13.1 percent in 2023 from the previous year, the steepest decline in almost three decades. China is also losing its position as the top exporter to the U.S. for the first time in 17 years. However, the decline is likely the result of the hefty tariffs in effect.

“The CBP is making every effort to be effective, but the Chinese programs are continuing,” said Pepper.

Cotton and other products from XUAR continue to be transshipped to U.S. supply chain heavyweights such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The CBP dashboard shows that out of the 402 shipments from Vietnam to the U.S., only 115 were released.

There are reports that cotton fibers and yarns from Xinjiang with counterfeit documentation are finding their way into Central America and Mexico. China is also sending an increasing amount of forced labor apparel to the EU, according to the Guardian newspaper in Britain.

Additionally, China runs state-sponsored labor transfer programs to circumvent the UFLPA. Uyghur workers are transferred against their will out of XUAR to factories and farms in other regions. Although these goods do not originate in XUAR, they are made with forced labor.

These efforts to circumvent the law demonstrate the difficulty of eradicating forced labor through trade regulations, but John M. Foote, partner at law firm Kelley Drye, said that’s not the right metric to use when evaluating UFLPA. “I think the way to think about trade law, like the UFLPA, like section 307, is, is it incentivizing the kind of activity that you want it to incentivize? And I think what you want it to incentivize is mapping of the supply chain, tracing of the supply chain, and the assessment of the exposure to forced labor within the supply chain, specifically for those goods that are coming across the border into the U.S. market,” he said. “In that regard, I do think the law is a success.”

To reduce exposure, U.S. brands are reassessing their sourcing scenarios, but those we contacted declined to comment.

“Brands are making a definite move away from Xinjiang’s lovely long-staple cotton,” said Pepper,

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 11

who now works as a brand consultant. “They are looking for new sources of Pima in South America and Mexico, and at different varieties of longerstaple cotton in Turkey and India.”

Addressing what this means for recycled cotton

Any successes associated with UFLPA could come at the expense of another major denim initiative.

Inspired by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Jeans Redesign project, denim brands and suppliers are focusing on circular economy principles, including the use of recycled cotton. But the UFLPA has put a freeze on imports containing recycled fibers from textile waste, because it is impossible to prove their provenance.

“I have not done much denim business for the U.S. since they started enforcing the UFLPA. Buyers don’t want to take chances,” said Cyclo Recycled Fibers CEO Mustafain Munir. The company mechanically recycles cotton-based textiles from pre-consumer cutting waste. The resulting fibers are spun into yarn by Simco Spinning & Textile Limited and embedded with tracer particles from the Aware Integrity Solution, which enables traceability from yarn to finished product.

However, the nature of “waste management” means the origin of the original textiles is difficult to certify. “I can provide the documentation for the yarn, but how can you prove where the batch [of cutting waste] is coming from?” asked Munir. He prefers to source the cutting waste from vertical operations.

Europe has become Cyclo’s biggest market. “The

EU already has a mandate for recycled cotton. They have a more comprehensive view of sustainability beyond forced labor.”

At Kipaş’ denim operations, “We mostly recycle the pre-consumer wastes of our own production,” explained Mustafa Güleken, general manager. “We have our own recycling and shredding unit in Kipaş Textiles, which has 30 tons per day capacity for 100 percent cotton waste.”

For companies that are not vertical in this way, Cyclo’s situation illustrates the unintended consequences of regulation.

“There are already many hurdles when it comes to scaling innovation [including] price, performance, and quantifying the environmental impact. If you layer on top of that the barriers that come with customs and specific regulations, it can make it harder for innovations like textile to textile recycling to scale. That is why it’s important that these customs and regulations are nuanced, taking into account these innovations,” said Georgia Parker, innovation director for Fashion for Good.

To address this latest barrier by the UFLPA, the organization, which helps scale innovation across the apparel supply chain, is working on several projects designed to leverage traceability to ensure companies have compliant feedstock. The organization’s Tracing Textile Waste project, which will launch soon, is an open data standard to provide a central place for collecting and sharing information about where textile waste comes from so it can be used in the GRS standard.

Fashion for Good is also lobbying the EU for clarity around the language used in the regulations, specifically, what’s considered in and out of scope. For instance, currently fibers, yarn and pulp are not classified as waste, while monomers and polymers often are, which impacts recycling efforts and what can and can’t be imported.

Looking ahead for forced labor regulations

ESG commitments and the moral imperative are inspiring other countries to consider banning forced labor imports.

The EU has proposed a forced labor ban, placing burden of proof on companies importing from problem areas; and hopes to pass the legislation before EU elections in early June. However, the EU will need to consider the potential impact on the use of recycled products already mandated by the European Green Deal.

Canada’s recent legislation requires businesses to annually report their efforts to ban forced labor from their supply chains. Mexico is aligning with its North American neighbors, although with weaker rules of enforcement. In Japan, many businesses have voluntarily adopted the government’s guidelines regarding due diligence in human rights, including forced labor.

In effect for less than two years, the UFLPA is still in transition. “In the long run the UFLPA is a good thing,” said Herman. “The problem is with its implementation.”

Foote said the implementation, which he characterizes as “a byzantine mess of unpredictable action” is a direct result of the age and brevity of the forced labor import ban, which falls under a decades-old law. “[The Tariff Act] was written in 1929. The forced labor import ban is a total of 54 words. You cannot pass a statute that has 54 words that makes it illegal to do a single act, and then just sort of trust all the rest of the decision making, especially when it’s so complicated,” he said. “What do you have to prove? What are you going to focus on?

Who’s going to make those decisions? According to what standards? All of that is extremely ambiguous and unspecified.”

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 12

INTENTIONS VS. IMPACT

credit: Igor Ovsyannykov on Pixabay

X

SUSTAINABILITY AND DURABILITY LEAD CALIK'S MATERIAL INNOVATION

The Turkish denim mill leans into innovation to accelerate denim’s movement toward responsible production.

Calik Denim is committed to reducing the textile industry’s waste problem. The Turkish denim mill’s innovations give new life to recycled fibers, produce yarns that biodegrade quickly and create finishing that extends clothing life.

Calik’s commitment to sustainability is perfectly aligned with the slate of new environmental protection regulations coming from both the EU and U.S.

The EU has put forth recommendations for textiles to be more durable and easier to reuse, repair and recycle, and it will likely revise the EU’s Waste Framework Directive to include specific targets for textile waste prevention, collection, reuse and recycling. Meanwhile, legislators in the U.S. have unveiled similar bills at the state level. The NY Fashion Act would require companies to map their supply chains, set and meet emissions reductions in line with the Paris Agreement and work with suppliers to manage their chemical use. In California, the Responsible Textile Recovery Act is designed to require fashion to establish a stewardship program for the collection and recycling of their products, mirroring the extended producer responsibility rules enacted in the Netherlands, France and Sweden.

Against this backdrop, Calik will highlight its B210 and RE/J concepts at this month’s Kingpins show. The B210 technology, which represents years of R&D, ensures garments will reach more than 99 percent biodegradation in just 210 days, a number it has verified using ASTM’s Standard Test Method for Determining Anaerobic Biodegradation of Plastic

Materials Under High-Solids Anaerobic-Digestion Conditions. B210 is applied in the yarn and finishing process and can be combined with synthetic fibers, as well as all of Calik Denim’s stretch technologies, with no impact on elasticity. Furthermore, the more times the end consumer washes a B210 garment, the faster the item will eventually biodegrade.

In the denim fabric industry, there is a demand for recycled cotton due to sustainability awareness among consumers and brands. Circular economy initiatives, consumer preferences for recycled materials, and industry collaboration contribute to the adoption of recycled cotton. Technological innovations, traceability systems and blending techniques are advancing the use of recycled cotton in denim production.

RE/J is Calik’s answer to the growing demand for recycled fibers, as the industry looks for ways to reduce its environmental impact. Manufactured on an open-end spinning system with both pre- and post-consumer recycled cotton, it can combine with fibers like Lycra EcoMade and Lycra T400 EcoMade, as well as Lenzing’s Refibra technology. Calik offers its RE/J concept across a range of styles, including lighter-weight options, rigid articles and comfort stretch fits. All RE/J fabrics are also created with Calik’s Dyepro technology, which eliminates the use of water in indigo dyeing and prevents chemical waste.

In addition to utilizing circular materials, Calik is giving end consumers reason to hold onto their garments

longer with E-Last. The finishing process promises a flawless premium look, with garments fitting like the first time every time. The technology boosts durability by ensuring clothes don’t develop a baggy and saggy look over time while also preventing puckering. On the manufacturing side, E-Last boasts an almost 0 percent weft shrinkage rate, which reduces time and labor by eliminating the need for the pattern optimization and conditioning time in pattern laying needed for conventional fabrics.

A key component of many of the pending sustainability regulations will be accurate data collection and reporting. To provide its clients with the visibility they need into its resource and energy usage, Calik communicates transparently and efficiently through its customers’ preferred platforms. Additionally, the mill developed its Transparency Monitoring System in 2019 as a central resource to monitor and measure inputs in production and optimize resource use in the production process. The online tracking system also identifies and categorizes the most sustainable energy types through continuous monitoring.

After the earthquake in Turkey, the country has demonstrated resilience and recovery, with the denim sector addressing human resource challenges through government and company measures.

Supply chain partners can assist industries post-natural disasters through collaboration, assessing disruptions, financial and logistical support, technology adoption, and long-term planning.

10 14 KINGPINS QUARTERLY

ADVERTISEMENT

FEATURE

BEAT THE CLOCK

Many of the denim industry’s 2025 sustainability commitments are not aging well. How can we accelerate ahead of 2030?

BY CALETHA CRAWFORD

KINGPINS QUARTERLY

15

As the climate crisis worsens, apparel companies are in a race to beat the clock. As it stands now, it seems clear time will run out on at least some of the industry’s 2025 goals. But, it’s not all bad news. Things are moving, mindsets are shifting and priorities are reshuffling—just slower than anyone would have hoped. The good news for 2030 targets is government intervention is on the horizon, and with it there’s the expectation that progress will accelerate. In the meantime, denim is grappling with the expectation of a mixed bag of wins and losses next year. As we look ahead, it’s time to analyze how this industry is pacing, how incoming regulations will transform operations, and the challenges even legislation alone won’t fix.

“The main reason for the industry to miss its targets is because adhering to them is not the priority in a growth fueled industry where prices are more important than value,” said Ebru Debbag, executive director of global sales and marketing for Pakistan-based denim mill Soorty. “Currently, there are no obvious detrimental consequences for not adhering to the mostly voluntary goals, however the EU proposal for a Directive Green Claims, Extended Producer Responsibility, the 35 new sustainability-related laws that will go in effect in the coming two to four years are on everybody’s radar.”

Debbag credits denim on its increased awareness and momentum around recycled content and next-gen materials but said the lack of a globally recognized set of rules and universal commitments to science-based targets is holding the industry back. Despite this, Soorty is moving forward with commitments to SBTs and a goal to reduce GHG emissions by 54.6 percent by 2030.

Abhishek Bansal, head of sustainability at Indiabased textile manufacturer Arvind, too applauds denim on its use of sustainable raw materials but he points out other areas of concern.

“Many leading brands and manufacturers are using up to 100 percent more sustainable materials. The denim industry has also made good progress in recycled materials in both cotton and polyester,” he said. “However, when it comes to a few other aspects, like decarbonization, the industry is still far

away from reaching its 2025 goals, and at this pace, likely to miss even [reaching its] 2030 goals. Progress on adoption of renewable energy needs to become broader based, both geographically as well as across different brands and suppliers.”

As Bansal illustrates, outcomes in 2025 will vary with some aspects of sustainability faring better than others. Similarly, every company is on its own journey, moving at its own pace.

“It’s a case-by-case basis if we were to look at the individual goals these companies are setting around their 2025 targets. Collectively, I would say the industry is behind towards reaching the 2030 goals in terms of where they should be by 2025,”

DIRECT INVESTMENTS IN SUPPLY CHAIN, AS WELL AS OUTCOMESBASED INCENTIVES WOULD HELP IN RAPID ACTION ON THE GROUND.

said Lewis Perkins, president/CEO, climate solutions company Apparel Impact Institute (Aii), which is focused on helping the industry reduce its carbon emissions by half by 2030.

Specifically, he said, apparel is running behind on improving resource efficiencies and reducing carbon footprints. According to Perkins, the industry needs to be in the implementation phase throughout the supply chain. “Assessment, carbon calculation, roadmapping, and benchmarking… really was the work that started happening with some a decade ago, others five years ago. If you’re just getting started at that level, you need to play catch up,” he said.

V. Besim Ozek, strategy and business development director for Turkey-based denim mill Bossa, said his company is on track with its goals, which he

attributes to the company’s recognition that committing to ESG improvements shores up its financial sustainability. “Whenever we decrease the carbon footprint, that means we are paying less for energy,” he said.

Overall, Ozek said for all its shortfalls, denim is leading the apparel industry. “Denim industry awareness is a lot better than other textile products,” he said “In my previous career, I used to work in other textile areas. I can easily say that denim has the most green production.”

Even within the denim category, there are “bright spots,” according to Frank Zambrelli, managing director, global ESG retail at business consultancy Accenture.

“We’ve seen a significant acceleration of actual publicly facing commitments; science-based targets that have increased hundreds fold in just the last two years; the adoption of some more advanced pilots in certain areas of some of that value chain activity, specifically on GHG reduction; dynamic progress—and the brightest spot of course—in the scope one and scope two,” he said.

Zambrelli said regulation will be the next major accelerant.

Regulation Impact

Until now, goals have been voluntary, with few realworld business ramifications if they were missed, including reputational damage at the consumer level and greater scrutiny from those investors that are attempting to decarbonize their portfolios. With the tidal wave of sustainability laws making their way through their respective legislatures in the U.S. and EU, that’s about to change. There will be punitive consequences for businesses that don’t meet at least the minimum mandated requirements.

As with any new law, there’s a fear factor, but Zambrelli said these new regulations are also validating, and already they’re helping to justify sustainability efforts. “What we’re starting to see is that it’s almost giving a freedom and elasticity— the flexibility to invest, the flexibility to actually change the processes that were long held, and the

BEAT THE CLOCK KINGPINS QUARTERLY 16

freedom with their boards to say, ‘we actually have to do this’,” he said.

Zambrelli said in the near future, companies will need to report their remediation outcomes to the investor community just as they answer to Wall Street on revenue. “So, what we’re starting to see is this shift to accountability in the operating model, and actually even some compensation structures tied to some of these larger, more publicly facing goals.”

Moving sustainability goals from voluntary to mandatory will also open the door to new investments, Perkins said.

“It’s going to bring more partners to the table. It’s going to incentivize a lot of philanthropic funders who can participate in lowering debt stacks or interest rates related to lending capital,” he said. “If we can signal the market towards the investments that need to be made in the supply chain, and there’s a de-risking of those relationships between brand/retailers and the suppliers, there are plenty of other financiers, funders, private equity, banks that are ready to step in.”

When it comes to regulation, Ozek of Bossa said governments should consider leading with the carrot and not the stick.

“We definitely need some governmental support. Governments may decrease the VAT ration if the final garment has got minimum 20 percent postconsumer recycled fiber content in the blending,” he said. “This will motivate all the brands for sure.”

Collective Action

Getting every brand, supplier and partner motivated and contributing to change could have the biggest impact on how denim will measure up to its commitments—and currently, that’s among the industry’s biggest challenges.

“There is significant collaboration across the global denim industry between individual companies that is driving the overall effort of the industry,” said Jimmy Summers, vice president –environment, health, safety, and sustainability and chief sustainability officer for Elevate Textiles, which

is comprised of a portfolio of brands including U.S.-based Cone Denim, which is on track to meet its 2025 goals. “We need to continue to collaborate and share information and approaches in ways and spaces that are mutually beneficial and positively advance the industry.”

While Bansal said Arvind has a few partnerships with customers that share the investment burden, the practice is not widespread enough to accelerate change.

“Collective action and burden sharing are lacking in the industry. Coupled with lack of aspirational goals, it makes the implementation slower,” Bansal said. “This is a global and collective problem; hence it needs collective action from all industry stakeholders, and collective investments and risk sharing. The problem is that it’s seen in many cases as a manufacturing problem, and burden to improve falls on the manufacturing industry.”

Bansal said pricing pressure and transactional sourcing relationships are major hinderances. “Direct investments in supply chain, as well as outcomes-based incentives would help in rapid action on the ground,” he said.

Debbag of Soorty agrees that the burden must be shared across supply partners. “Off-setting needs

to transform into in-setting, where the funding goes directly to the operations linked to the supply chain,” she said, pointing to the collaboration between Bestseller and H&M for an offshore wind power project in Bangladesh as an example of what can be achieved. “The supply chain needs to transform into an understanding of supply system, where investments enable goals of individual partners as well as the whole.”

Zambrelli said his team is seeing more thinking along these lines, particularly from organizations that are on track with their own goals. They recognize their efforts alone won’t mitigate risk or bring on complete decarbonization.

“From the large organizations, from the public organizations, we’re seeing much greater collaboration, co-benefit models that are being created, investments that are being made, but also a level of conversation beyond just the supplier-brand partnership… to engage in elements that can help the system shift,” he said. “That’s just good business. If you don’t get involved in changing tier four as a major denim company, you’re going to risk volatility and supply in a very short number of years.”

Perkins said there are still some CFOs who fail to recognize the need for investing in the supply chain. To that end, Aii has established the Fashion Climate Fund, which allocates resources toward decarbonization by region and by clusters so brands are investing in suppliers that they have a direct interest in.

“The companies that aren’t [participating], it does tend to be a lack of either understanding or just their philosophy on whether or not they believe it’s their role to subsidize suppliers in this work,” Perkins said, adding incentives can take on a lot of different forms, including being recognized as a preferred vendor based on achieving pre-set goals. “Sure, [suppliers] would love lower interest rate loans… but ultimately, they’d be willing to take on a lot of personal investment from their own corporate treasury or partner with financial institutions if they have that line of sight towards longer-term purchasing agreements or commitments to volume.”

1 7 KINGPINS QUARTERLY 17

EGYPT'S DENIM EVOLUTION

Diverse sourcing is a necessary industry trend and investors see Egypt as the next denim production hotspot.

BY DOROTHY CROUCH

Egypt’s emergence in the denim category— bolstered by infrastructure investments and trade deals—is coming at a time when other regions are struggling. Denim producers in Asia struggled amid COVID-19 challenges and Turkey continues to navigate hurdles surrounding political instability, inflation and an energy crisis exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Egypt is taking the opportunity to shine as an affordable, geographically desirable resource with major investments supporting growth.

All that Egypt Offers

Egypt’s population totals nearly 110 million people with 60 percent between 15-64 years old. Denim producers offering relatively well-paying jobs with on-the-job training for members of this young population attract candidates who are interested in starting a career in this trade.

“Many members of the population are young,” said Emessa Denim founder Anis Trabulsi. “These are mainly machine workers. Egypt is a very appropriate country if you need this type of employment—not always a high university degree or higher. “

Emessa is a full-service operation located near

Cairo Egypt’s Beni Suef Governorate, with capacity to produce 2 million pieces annually. Trabulsi noted the highest demand for his products from Egypt came during 2022 and 2023, during COVID-19 recovery.

The monthly minimum wage for these workers in Egypt’s private sector jobs rose Jan. 1 to E£ 3,500, or $113.28. Though wages are up, the value of the currency is down. The current exchange rate is E£ 30.90 for every $1.

“If you live in Sadat City, where our factory is located, it’s a very good amount because the cost of living is not very expensive,” said Dilek Erik, marketing director for Sharabati Denim, a 46-year-old company that also provides employee benefits such as healthcare and reduced-cost housing.

Egypt’s cost of labor falls on the lower end among major denim producing countries, alongside Bangladesh, Tunisia and Pakistan. Turkey, the denim-producing country with the highest labor costs among major denim producers increased its minimum wage by 49 percent beginning Jan. 1 ₺to ₺17,002.12 or $551.88.

While Egypt-based employees can be trained to create goods that rival their counterparts in leading denim-producing countries, this

evolution takes time—and money. Semih Erinc co-founded denim maker Chantuque in 2004 in Istanbul and expanded to Cairo in 2009. Erinc said the quality of products from denim mills in Turkey came as a result of a lot of investment, which Chantuque is committed to in Egypt as well. “We see Egypt as the future. Last year, we made $4 million in investments and we will invest more.” he said.

Egypt’s energy resources have also remained stable. According to Sedat Sualp, sales and marketing director at DNM DENIM Mill, Egypt’s energy independence is an asset.

“Egypt is a natural gas-producing country. It’s not obligated to import energy from other countries,” Sualp said.

Many producers in Egypt are also positioned to be ahead of sustainability goals. DNM DENIM, which has an Istanbul office and Egyptbased spinning, weaving and dyeing facilities in Damietta, Egypt, has monthly capacity for 2,700,000 meters.

“DNM DENIM Mill has already invested in solar energy panels and a co-generation facility and is able to produce its own energy,” said Sualp. The growing denim industry in Egypt allows

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 18

FEATURE

credit: DNM DENIM Mill

producers to build a sustainable industry as they grow their businesses by relying on the latest clean innovations and materials.

“These factories [in Egypt] are quite new, so in terms of sustainability, development is quite conscious. As they build new, they are building in the most sustainable way,” said Erinc.

Although Egypt is centrally located to easily transport goods to Europe and the U.S., recent challenges have included attacks on ships by Houthi militants from Yemeni in the Red Sea. This threat has led some transporters to refuse routes through these regions. According to Erinc, shipments to New Jersey in the U.S. arrived from Egypt in two weeks under typical conditions, faster than goods shipped from Turkey. “At the moment, there are some rough times because of the crisis, but apart from that it is easy to find vessels to the U.S.,” said Erinc. “Egypt is good regarding transportation because of logistics where they are based geographically, the Suez Canal and the ports like Port Said and Alexandria are quite busy.”

Ongoing Challenges

Inflationary pressures have caused economic headwinds across the globe and Egypt is no exception. The country’s core inflation skyrocketed from 6.269 percent in January 2022 to 31.241 percent in January 2023.

“Egypt is not facing any other different challenges than the rest of the world,” noted Rabia Kabal who manages U.S. sales for Sharabati.

fell to 29 percent in January after a high of 38.1 percent in October 2023. Certain manufacturers also conduct business in a currency other than the Egyptian pound.

“As we are in the free zone, all our trade is with U.S. dollar and euro,” explained Sualp. “That’s why we are not affected by fluctuations in currency rates.”

Designated free zones in Egypt are areas within the country that allow companies to conduct business under regulations designed to promote economic growth. These considerations include special taxation, exemptions and privileges. Additionally, through the Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ) initiative, products exported to the U.S. from Egypt remain dutyfree if the goods contain components from Israel.

The country’s geographic location is often viewed as an asset, but the Israel-Gaza conflict continues just beyond Egypt’s border. Despite the war, denim companies that operate within the North African country are confident in Egypt’s political stability. “Egypt is not ready to risk a new revolution or disorder,” said Trabulsi.

Egypt’s Denim Evolution

Continued investments by Egypt’s government and foreign investors are cultivating strong opportunities for manufacturing in the country.

In October, the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZONE) signed agreements with Chinese textile firms for more than $100 million in investments within Egypt’s West Qantara Industrial zone. The agreements were made ahead of Egypt’s 2024 admission into the BRICS bloc of major emerging economies including Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Investors in the SCZONE deal included Shanghai Shengda; Zhejiang Hengsheng Dyeing and Finishing Co., Ltd.; Shengzhou Captain Industrial & Trading Co. Ltd.; Indochine Holdings Pty Ltd.; and Shaoxing Yuding Textile Co., which seeks to establish a new factory as DINGHANG Egypt Co. The factory is projected to export 90 percent of its total production to American and European markets.

have been built up, while new investments are also in works,” noted Sualp. “As a small example, 10 years ago, driving from Cairo Airport to DNM Mill took 4.5 hours, while today it just takes 2.5 hours.”

According to Erik, Sharabati is preparing to increase its capacity to approximately 108 million meters from 100 million meters annually in Egypt where it produces denim and denim-relative nondenims in different weights and hues. Erik believes Egypt must grow on the garment-production side.

“If they have more denim garment manufacturing in Egypt, the denim fabric will be in greater demand,” explained Erik. “You get the nice denim fabric here but if the garment manufacturing is not supporting it, that is still a difficult.”

There is hope on the horizon, as core inflation consistently

“For the last five years, Egypt has made major investments in its infrastructure. New motorways, bridges, and ports

For Magdi Tolba, founder of T&C Garments, a joint venture company founded by Egyptian Tolba Group and Turkish Tay Group, one solution for growth is to invite outside investment, particularly from Turkey. “As Turkey continues to move toward the high-tech sector, Turkey will be looking to invest in operations abroad, especially as the cost of labor continues to increase. I think it’s in the best interest for both countries to get closer,” he said, noting the strategic advantage this would create as the industry looks for options outside of Asia. “Egypt’s textile exports are modest compared to Turkey’s so it would be a win-win for Turkish companies to invest here.”

19 KINGPINS QUARTERLY

credit: Sharabati Denim

credit: Emessa Denim (top); Chantuque (bottom)

AT DNM, RESPECTING NATURE COMES FIRST

A denim mill committed to continuous improvement across a broad spectrum of environmental goals.

At DNM Denim, every collection has a story behind it. The overarching narrative of our denim mill, since its inception, has been protecting the planet, people and its partners’ best interests. Established in 2011 in Egypt with Turkish capital, the company was founded on the twin principles of product innovation and respecting nature.

The company’s environmental production approach has led it to implement a ZLD closed treatment Plant, minimize electricity consumption, and use solar and thermal energy sources such as solar panels. DNM is also doing its part to clean up denim’s dirty little secret when it comes to water.

“Water is life! It is estimated that in conventional denim production, over 80% of wastewater is

released into the environment without adequate treatment. Therefore, we believe that reducing water consumption and protecting natural water resources are crucial steps,” said Sedat Sualp, sales and marketing director, DNM.

DNM uses the ZLD System (Zero Liquid Discharge) to prevent the discharge of industrial wastewater into the environment. All of the water used at DNM goes through the ZLD system. This enables the company to recycle 90.2% of all water used back into our system. To measure these efforts, DNM regularly carries out water and carbon footprint measurements every year.

DNM’s commitment to water efficiency and re-use means the company enables its supply chain

HOW EMESSA DENIM TAKES RISK OUT OF THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Through a flexible business model and a stable sourcing location, the trouser supplier enables retail partners to execute on small-order, quick-turn strategies.

With so much uncertainty threatening the apparel industry, sourcing executives are prioritizing resources, partners and production locations that provide stability. Emessa Denim, which has just entered the U.S. market after years of success in Europe, checks all of those boxes.

The Egypt-based denim resource is set up to help its partners minimize the risk inherent in placing large orders months in advance. “We have the right system and set up for small orders. It’s about material, inventory and production planning,” said founder Anis Trabulsi. “We work very easily with medium-size, higher end fashion brands in the EU that require frequent reorders, so we can accommodate these needs.”

Emessa’s factory is designed with flexibility in mind, with a variety of machines in the production line to cater to an array of styles. Additionally, workers and line supervisors are all cross trained so they can switch tasks, as needed. It’s not uncommon for the company to hold inputs in its warehouse for clients executing a postponement production model. Beyond that, Emessa’s proximity to fabric manufacturers like DNM and Sharabati is ideal for quick samples and reorders.

Add to that a 20-day maximum shipping time to the U.S. and 9 days to the EU, and Emessa is ideally positioned for slashing timelines and enabling partners to execute a chase model.

partners to meet their goals. Together with its brand and retail clients, DNM is working to increase its use of natural energy sources, increase the use of sustainable fibers and work towards zero carbon targets. It is a continuous evolution that allows the company to enrich its product offerings with fabrics that are fashionable and responsible.

Looking ahead to the next five years, circularity is at the center of the DNM’s goals, while also addressing energy, chemicals, waste, efficiency, and processes to reduce its environmental footprint.

BOOTH: BLUE 30

For buyers not familiar with Egypt, Trabulsi urges them to take a second look—the country hosts a variety of suppliers that offer products like t-shirts, sweatshirts and sweater knits that Emessa can help facilitate connections to. “Egypt is a very stable and safe country. The president has made many investments in infrastructure, which means Egypt rivals some parts of Europe,” Trabulsi said, adding the country boasts four international ports, superhighways connecting major cities and a consistent supply of natural gas. Egypt’s young, English-speaking population of more than 100 million equals a strong workforce, he added.

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 20

ADVERTISEMENT

EGYPT'S OPPORTUNITY: KEY PRODUCERS IN THE EMERGING PRODUCTION DESTINATION

EMESSA DENIM – THE GREEN FACTORY

EMESSA DENIM is a leading sustainable garment manufacturer in North Africa, occupying 20,000 square meters with 1,700 employees. Producing 2.5 million garments yearly for men, women, and kids, including denim and flat bottoms, it utilizes cutting-edge technology like automatic cutters, advanced sewing , embroidery, printing, laundry, and eco-friendly processes such as ozone treatment and manual craftsmanship. Certified by GOTS , BSCI, and ISO, it signifies the factory’s commitment to sustainability and quality.

our new website: www.emessadenim.com

DEVELOPING PROJECTS ACHIEVING EFFICIENCY & SUSTAINABILITY. Visit

BRINGING LARGE SCALE PRODUCTION INTO FASHION

Keeping the numbers up while making an impact in high fashion and sustainable production, leading denim and flat fabric producer Sharabati shows how it is done.

From cotton bale to finished fabric, the Sharabati company takes care of it all. Since its foundation in Syria in 1978 and relocation to Egypt in 1998, Sharabati has enjoyed steady growth, including expansion to Turkey in 2005. The company prides itself on its ability to produce more than 140 million meters annually, while strengthening its commitment to sustainability and at the same time collaborating with prestigious names in the world of fashion.

With its workforce of more than 5,000, modern factories in Egypt and Turkey, and vast network of sales offices, Sharabati is a major player both with mass retailers and high fashion brands. Its export portfolio boasts 27 countries.

The company’s focus on sustainability is perhaps best

represented by Tadweer, Sharabati’s state-of-theart recycling plant that recycles 22 tons of production process waste daily in Egypt. Also, Sharabati’s Re-live collection, which includes 100% regenerative cotton fabrics, recycled yarns and natural indigo dyes, is summarizing just a few of the sustainable fiber and processes used. At Sharabati every single production step is conceived and geared to maximum efficiency, so is sustainable both in terms of savings, recycling and reduction of resources.

Along with regular expansion and modernization, Sharabati stands out from large-scale competitors through its partnerships. Sharabati supplies over 100 globally recognized brands but also establishes more exclusive partnerships that still manage to have mass appeal, including a recent collaboration

FOR T&C GARMENTS, THE KEY IS CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT

The heart of denim in Egypt focuses on maintaining facilities, training and services at a world class level

T&C, a joint venture company founded by Egyptian Tolba Group and Turkish Tay Group, launched in 2010 with 500 workers producing 5,000 pieces per day. Today, the company is one of the biggest denim producers in Egypt, with 7,300 employees producing up to 65,000 pieces a day, up from 18,000 pieces in 2000. T&C offers cutting, sewing, laundry, finishing and design and has an onsite accredited lab to save both time and money.

The company’s growth was strategic. As chairman Magdi Tolba saw business moving out of Asia and the demand for shorter lead times borne from the pandemic, he decided to triple the investment in machinery, staffing and construction. Now, the company ships to 35 international destinations a week, primarily to the

U.S. with just under a third bound for the EU.

T&C operates on a principle of continuous improvement. “We have a policy: if you don’t innovate and upgrade your machinery almost every year the factory will become like an old sick man,” said Magdi. “Every couple of years, we make a complete evaluation of the factory. We replace old machines with new ones as they come out, which means that the factory is young and modern.”

To that end, T&C is investing 120 million pounds to boost its sustainability. The first is water treatment that recycles 80 percent of the company’s water usage. T&C is also leaning into solar energy, with the goal of covering 50 percent of its overall energy usage.

with Italian expert fine printers Delago, whose exclusive designs are produced at Sharabati’s factories. Additionally, Sharabati’s Dream of Nile collection uses high quality Egyptian Giza 94 cotton resulting in lustrous drapey, super soft fabrics with a luxurious feel and all the durability of denim.

Sharabati’s ability to evolve, anticipate and meet the needs of the ever-growing fabric market will ensure its strong position among the industry’s top producers.

BOOTH: BLUE 31

“We work hand in hand with our clients on construction and design, and we host them in their own offices here,” Magdi said. “Working that closely and having personal communication with them daily is a major aspect for long-term cooperation and success.”

Magdi credits the company’s success to its workforce, which it works hard to retain and train. Recently, T&C implemented a system to measure the efficiency of the workers, which translates into monthly bonuses and furthers its goal of improving efficiency by 20 percent.

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 22

ADVERTISEMENT

EGYPT'S OPPORTUNITY: KEY PRODUCERS IN THE EMERGING PRODUCTION DESTINATION

FEATURE

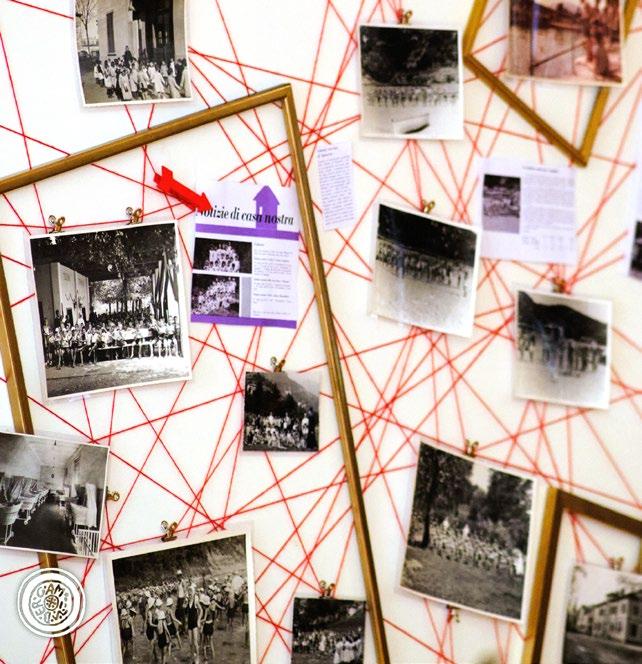

LEGLER'S LEGACY

One Italian denim mill that saw a boom and then bust as the denim industry’s fate evolved with the rise of jeans and the introduction of free trade

BY ALDEN WICKER

KINGPINS QUARTERLY

23

Crespi D’Adda is unlike any other Italian village you’ve seen. Laid out on a neat grid reminiscent of a 1960s American suburb, the Italian-style homes, which used to house the employees of the cotton mill, get grander as they move south, culminating in the large villas for the upper management.

This World Unesco Heritage site is a popular day trip from Milan for Italians interested in the region’s rich textile history. It’s also a pleasant walk around the quiet town, its homes and gardens in various states of disrepair.

“It was the leader probably for 25 years, in Europe for sure, maybe in the world,” said Mauritzio Baldi, one of the premier denim designers in the world, who now works for Diamond Denim in Pakistan.

Elisabetta Benagli, who worked in sales for Legler from 1974 to 2007, points out the office in which she worked, inside the renovated headquarters of the cotton mill, which was originally built in the late 1800s.

“I used to come early, before I had to be in the office, just to have a walk. It was so refreshing.”

Now the brick smokestack leans precipitously over the road. The mill, with its star-shaped brickwork around the windows, is too dangerous to go inside. The clocktower behind the locked gate is stopped at 4:52 pm, the moment when the fate of this mill town, and, arguably, the fate of a textile dynasty stretching back to the 1700s, was sealed.

130 Years of Swiss-Italian Cotton

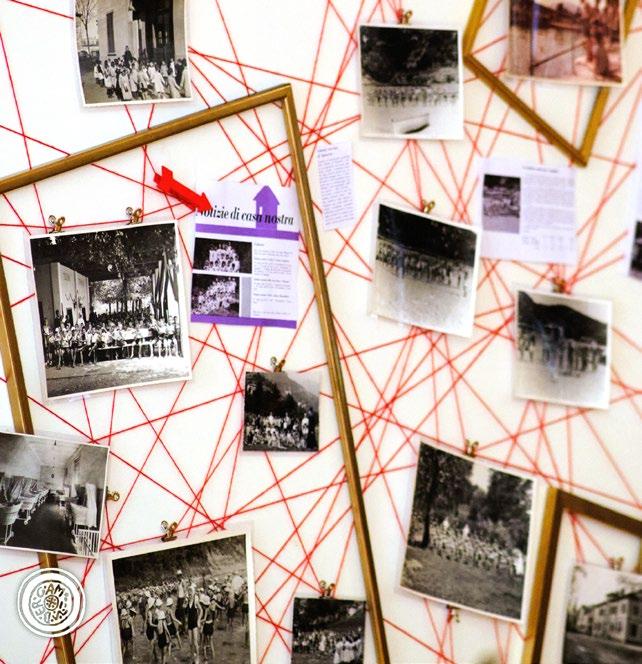

The Legler Foundation, housed in the former headquarters of the Legler textile firm, is putting on an event to celebrate Legler’s crucial role in Ponte San Pietro’s history. Middle-aged and elderly people, many of them former employees, peruse the exhibit of cotton fabric samples, plus marketing materials for something called Quikoton, a non-iron cotton from the 60s.

“This thing touched so many families,” said Marco Bonzanni, a respected denim professional who now works at Candiani Denim, looking around.

During speeches by the incoming mayor and a local economist, black-and-white footage plays behind them, showing the old factories running at full tilt. In one, a man inspects the bolts of cotton, while another man with a typewriter on wheels follows him to take notes. In another scene, young men pour steaming dye from buckets into old dye baths with cloth rollers.

It’s a rare day in which the public can enter the archives and get a tour. We dive into the library with rows of leatherbound books, then up the stairs to the old offices, where the tour guide opens up locked cabinets stuffed with rows of colorful mid-century fabric swatches. Binders are open on the tables, full of fashion ads and editorials featuring models wearing summer dresses using Legler cotton.

By the time the Legler family set up shop in Ponte San Pietro, it had been in the business of cotton spinning and weaving in their home country of Switzerland since the 1730s, according to an Italianlanguage biography of Fredy Legler (1916-2002) published in 2021 by the Fondazione per la Storia Economica e Sociale Di Bergamo.

In the 1870s, the Legler cotton mill was outgrowing its hometown of Diesbach, a sleepy and small

village in the Canton of Glarus. When Italy was unified in 1861 and imposed tariffs on imported textiles, the village of Ponte San Pietro outside of Milan beckoned. Swiss manufacturers had been in the Bergamo area since the 17th century, which was famous for its silks. Ponte San Pietro, about 9 kilometers away, population 2,700, had a rushing mountain river to provide power to a mill, a railway connection, proximity to Milan, and – familiar story –low wages.

So in September of 1875, Matteo Legler purchased land on the bank of the Brembo River just above the Ponte San Pietro railway crossing. Swiss technicians built the new factories in 1876. By 1887, Matteo had added a small dyeing and then bleaching department, and in 1894 built a small iron bridge over the river to connect the Legler buildings on either side.

From almost the beginning, the Legler family and its eponymous company were an example of a community-oriented business – at least, for its time. The Legler company built housing for employees, opened a Swiss school, contributed to the founding of a worker cooperative store where employees could get basics at below the market rate, and opened an old age and sickness fund for employees. In 1906, it had 1,600 workers: half of

KINGPINS QUARTERLY LEGLER'S LEGACY 24

them women and 20 percent of them children. (Child labor laws weren’t instituted in Europe and America until the late 1930s.)

Matteo upgraded his company’s product from cheap calico and moleskin – a cotton fabric that is brushed to make it fuzzy – to higher-end cotton

textiles like velvet, a complex textile cut by hand that had a production cycle of 60 days.

In the 1910s, textile firms provided two-thirds of the employment in the Bergamo region. The Legler firm, guided by the second generation of the Swiss family, survived the financial crisis of 1907, both World

Wars and the bombing of Bergamo’s factories, and recurring cotton shortages, to become famous for its quality cotton textiles.

In 1950, when it celebrated 75 years, Legler had 2,730 employees –– equal to the entire population of Pon San Pietro the year of its founding. By all accounts, it was a great place to work. Legler provided marriage and childbirth bonuses, subsidies for funerals and health services, subsidized housing, a retirement home, a kindergarten, an infirmary, sports equipment and courts, and education scholarships.

All was not perfect, of course. As at all textile companies, the mill produced cotton dust which can cause lung disease; the noise of the shuttle looms was deafening; and fumes pervaded the dye house. Still, employees often remained in the company for 30, 40, even 50 years, with multiple generations of the same family entering the firm –including the Leglers themselves.

Fredy Legler, the third generation, moved into management of the Italian firm in the 1950s, though he wasn’t handed the reigns until the mid-1960s. Fredy had his work cut out for him. The heyday of textile production in the Bergamo area was on the decline.

In September 1968, Fredy shared in a speech at the International Federation of Cotton and Allied Textile Industries a familiar complaint to those in the industry even today:

It’s a fact that textiles really get bad press. This mediocre image reflects a vicious circle: the instability of the industry causes a general lack of trust, so that it risks attracting above all mediocre personnel, which, in turn, only increases this instability... If the textile industry were presented as a modern industry, up to date with the most modern techniques, and investing confidently in the future, much would be done to correct the current image, and young and capable managers could be attracted.”

His first big move was to convince French couture designers, including Hubert de Givenchy, Pierre Balmain and Pierre Cardin, that Legler cotton was just as glamorous as silk for their dresses. Balmain and Cardin would frequently travel to Ponte San Pietro to discuss

KINGPINS QUARTERLY

25

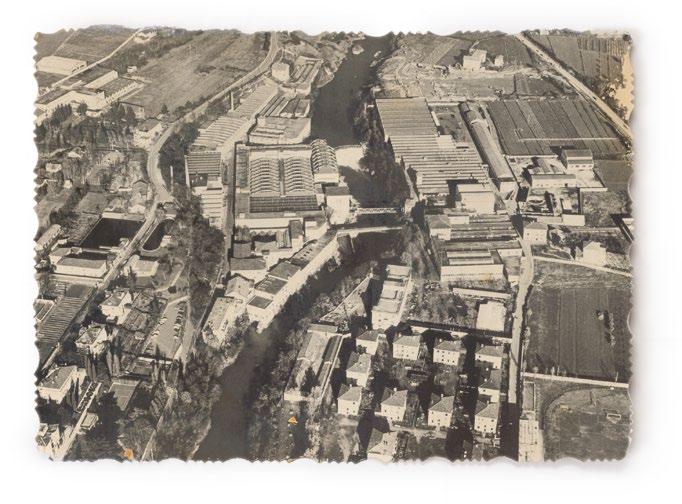

A weaver (left), an aerial view of the factory (top) and external views of the offices (above); Carding mill 1956 (opener) Credit: Fondazione Legler

fabrics for the next season. The 1968 budget report said that 21 percent of Italian cotton exports were from Legler. That rose in the following years to a third of all cotton exports.

But with the upcoming renewal of the textile union labor contract in 1970, Legler faced higher labor costs. Making such small runs of all different types of cotton in all different prints and colors was inefficient. Fredy was looking for a way to simplify.

Denim to the Rescue

Denim was exploding in popularity in the United States, and that fervor had invaded Europe, leading American denim brands like Lee and Wrangler to open up cut-and-sew factories in Belgium and import denim fabric from the U.S.

Legler knew its cotton. But it would have to install new equipment to make the 150-centimeter-wide fabric (as opposed to the 90-centimeter-wide fabric it had been making) and to switch from jigger dyeing to continuous wide dyeing. The benefit to making it in Europe was that it would cut the shipping and tariff cost of importing denim by 25 percent.

Legler formed a partnership with an old cotton textile mill 14 kilometers away in Crespi d’Adda and called it Inditex (no relation to Zara). With the help of an American consultant, Legler set up a new factory system within nine months to dye and weave 15 million meters of blue denim. Raw fabric flowed from Crespi D’Adda to the finishing plants in Ponte San Pietro. By the beginning of 1972, Legler was shipping denim fabric to factories in Belgium, surprising the American brands with its speed and success, and making it one of the first denim mills in Europe. (Italdenim started shipping denim the same year.)

As more denim brands set up cut-and-sew factories in Europe, Legler expanded production. Turnover increased from 35 billion Lire in 1969 to 150 billion Lire in 1975. According to professor Giuseppe De Luca, president of the Legler Foundation, in the 1970s, Legler provided denim for a quarter of all jeans made in Europe.

“One of the main advantages of denim production by Legler was that it could supply the Belgium mills with a great quantity of denim of the same quality in one shot,” De Luca said. “So from the point of view of the producer, you have a reduction in the cost of negotiating with a lot of suppliers.”

Elisabetta Benagli joined right out of school in 1974, managing accounts first in Scandinavia and then in America. She had an apartment to live in during the week in Ponte San Pietro. In the morning, she would play tennis with another employee on the company courts. In the evening, clients and employees from all over the world – Germany, Japan – would gather in the kitchen for a meal and conversation. “I loved working for that company. I think I never ‘worked.’ Work is something hard.”

The secret sauce, according to the former Legler employees I talked to, was Legler’s mixing pot

of international people, who kept the company dynamic and creative. “They hired managers and people from all around the world,” Benagli said. “We had managers coming from India, the States, quite a lot from England, from Germany, Switzerland…”

Many called Legler a denim university, which trained up some of the best denim professionals in the world in everything from sales, to dying, and designing. “The people coming out of it were really well trained,” Bonzanni said. Despite being in Italy for a century, the Legler management still hewed to Swiss precision and efficiency, plus Italian creativity, heavily salted with quality control and management techniques Fredy had brought back from a visit to America in the late 1950s.

During those heady days of denim domination, Fredy Legler and his executives and salespeople

KINGPINS QUARTERLY 26

LEGLER'S LEGACY

Memory board credit: Fondazione Legler

(including Benagli) lived large, traveling by private plane to meetings and trade shows all over Europe.

As the company moved into the 1980s, denim proved to be the only truly profitable product Legler was making – cotton corduroy was trending down. In 1988, an article in the publication Tinctoria said that there were 1,944 Italian and 406 Swiss employees, with 313 billion Lire in turnover. But it was a fickle success. Others had rushed into Europe, and

especially Turkey, to set up denim mills, crowding the market with overproduction. “In the 1980s it had become increasingly clear that investments aimed at reducing costs and making production more efficient were no longer enough,” Fredy Legler’s biography says.

A short-lived partnership with a mill in Pakistan was attempted and abandoned. By 1997, Edoardo had left his nephew Vincenzo in charge of Legler. Vincenzo died at age 37 in 2002, leaving the company without a head.

IN THE MID TO LATE ‘90S, AS THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION BROKE DOWN TRADE BARRIERS, MORE LOWCOST COMPETITION CAME ONLINE FROM EGYPT, PAKISTAN, BANGLADESH AND CHINA.

Ideally, Fredy Legler would pass the company on to the fourth generation and let them innovate, but neither his children nor his nieces and nephews were interested in taking over. So in 1989, he sold it to a fellow Italian businessman, Edoardo Polli. The Polli family renovated the old headquarters in the cotton mill in Crespi D’Adda and moved many of the employees there in 1992.