UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF KINESIOLOGY | FALL 2025

In the course of researching people to name her title after, Sandra Hunter rediscovered iconic track star and coach Francie Kraker Goodridge.

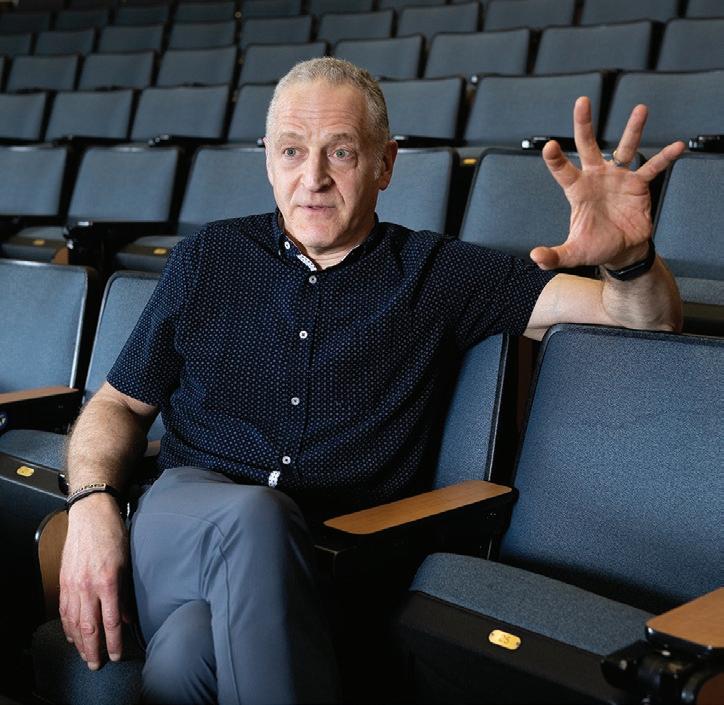

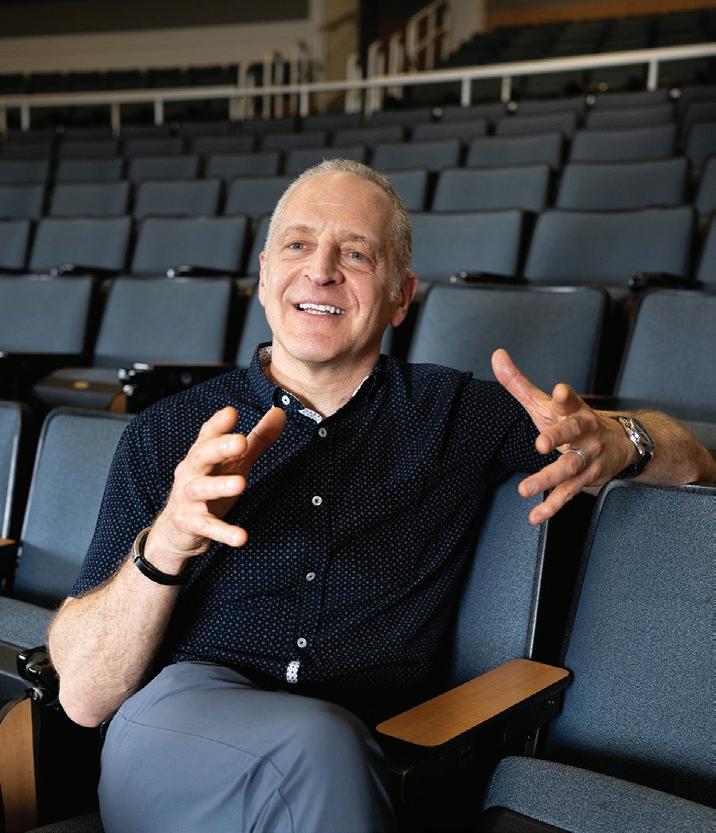

Jeff Horowitz explains how he translates his research for the public.

The Human Performance & Sport Science Center is using data to help college athletes level up their training and students level up their expertise.

Kara Palmer asked her motor behavior students to apply a semester’s worth of knowledge to an unexpected setting.

Steven Broglio and his team at the University of Michigan Concussion Center are creating opportunities for education and dialogue with the public.

The U-M Sport Management Program has planted the flag as a leader in sports venues research. A senior seminar shows why.

Learn how to keep patients safe during complex surgeries through our new intraoperative neurophysiology master's program.

Global Ambitions

How Kines is trying to give more students access to international experiences.

In the Zone

Students translated their notes and memories from their trips to Italy and Greece into creative works that challenged them to think differently.

Learning By Doing

In the donor-funded Jones Movement Scholars Program, students have enough time, money, and support to see what a research-focused career is really like. 24 Against the Odds

Two students who competed in the 2023 Paris Olympics shared some of their slidingdoors moments.

Courting Conflict

A student group based on inclusion re-envisions a future where difficult conversations are normalized.

This Is Our America

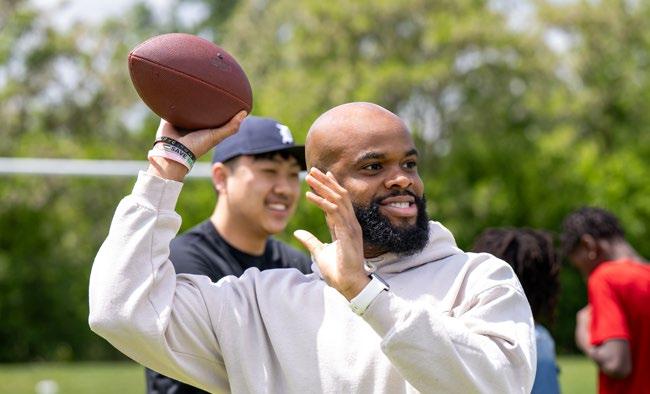

PhD student Leesi George-Komi applies his family's experiences to help the next generation of Black and immigrant youth cope with stress.

32 Mother Figure

Mother and daughter alums Colleen Scrivano and Katelyn Darkangelo on passing down a culture of physical activity to the next generation.

34 Tales From the Broadcast Booth

Retracing the career paths of two sport management alums who snagged broadcasting roles for professional sports teams.

36 Role Model

Alexa Poplawski's knowledge of movement has elevated her eye-catching looks as a model.

38 Split Time

Two days in the life of Jesse von Arx, who switches between roles as a surgical assistant and athletic trainer for a foot and ankle surgeon.

40 Winner's Circle

The recipients of the School of Kinesiology annual alumni awards.

Everyone should have access to safe, joyful movement, including people with disabilities. Here’s how we're working together to build more inclusive environments so anyone who wants to can move.

is published by the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology. Visit us online at kines.umich.edu/movement

Dean

Lori Ploutz-Snyder

Editor

Mary Clare Fischer

Writers

Mary Clare Fischer

Leesi George-Komi

Aaron Kasinitz

Ashlyn Perry

Jesse von Arx

Art Direction & Design

Stacy Getz

Additional Designers

Linette Lao

Matthew Sturm

Photographers

Jessica Bone

Eric Bronson

Mark Clague

Isaiah Downing

Isaiah Joseph

Erin Kirkland

Daryl Marshke

Christina Merrill

Scott Soderberg

Matthew Stephens

Leisa Thompson

© 2025 Regents of the University of Michigan

The Regents of the University of Michigan Jordan B. Acker, Michael J. Behm, Mark J. Bernstein, Paul W. Brown, Sarah Hubbard, Denise Ilitch, Carl J. Meyers, Katherine E. White, Domenico Grasso, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/ affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office for Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, institutional. equity@umich.edu. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

Read more about Kraker Goodridge and why we’re giving her our Lifetime Achievement Award on page 41.

when Francie Kraker Goodridge (PE minor '74) received a letter in the mail letting her know that a University of Michigan professorship had been named after her, she thought it was a scam. But once she researched Sandra Hunter — the new Francie Kraker Goodridge Collegiate Professor of Kinesiology at U-M — Kraker Goodridge realized this was no trick. She learned that Hunter, an international expert on sex differences in athletic performance, had been given the opportunity to name her title after a “deserving recipient” when she joined Kines. Hunter had turned to the U-M and Michigan Women’s halls of fame for inspiration and came across Kraker Goodridge — an Ann Arbor native, a U-M alum, a track star who’d participated in the 1968 and 1972 Olympics (pictured), and the first female track and field coach at her alma mater. “Your name and achievements rose to the top,” Hunter wrote in her letter. “She’s just phenomenal,” Hunter says now. “This is such a fitting way to honor Francie’s accomplishments and career as a former elite athlete, coach, and advocate for women and set the tone for the research I will continue to do here at Kines in high-level sports.”

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Photos by Christina Merrill/Michigan Photography

In the last year alone, movement science professor Jeff Horowitz has amassed enough quality media hits to make any researcher proud: The New York Times, NPR, CNN, NBC News, WebMD, Scientific American. Nearly all of these interviews stemmed from a Nature Metabolism study for which he was the senior author, finding that several years of endurance training remodeled abdominal fat to make it healthier in adults who were considered overweight or obese. Horowitz has a long history as a go-to source for science reporters, so we sat down with him to hear how he tries to translate his research for the public and why he’s passing that knowledge along to the next generation.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Q: There are a lot of researchers who, even though they probably know that their work has an impact on society, don't take the steps you do to make sure the layperson understands their research. Why is that important to you?

A: Well, I don't seek out opportunities to get the megaphone and say, Look, this is what we found

But the work that we do in my lab — working with humans, studying fat tissue — a lot of people are very interested in. It’s a topic that’s ripe for the lay press to cover. When approached, I'm very eager to share the information and also help clarify misunderstandings.

Q: What have been some of the most frequent misunderstandings around the work that you do?

A: The most recent work we did that got all that media attention focused on what exercise does to fat tissue. In this research, we found that exercise makes the fat “healthier.” Importantly, this doesn’t mean that exercise will reverse the health complications that are common in people with obesity. Instead, the effects of exercise on fat can protect against health complications if people gain more weight in the future.

We’ve done other studies that looked at how exercise improves “insulin resistance” (when the body doesn’t respond properly to the hormone insulin). Most people with obesity have some degree of insulin resistance, which is a hallmark of many chronic health problems, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and many forms of cancer.

We’ll have people with obesity train for three months. We measure their insulin resistance the day after their most recent session of exercise, and it is typically much improved compared with before they started training. Then we have them avoid exercising for a few days — and when we measure their insulin resistance again just three days later, it's as if they never exercised. What we’ve found is that today's exercise makes them more sensitive to insulin today and into tomorrow, but then it peters out. So, we think of it like a drug — you have to get your “dose” of exercise most days to help maintain your sensitivity to insulin.

Q: That was such a good exercise (pun intended) to see how you explain your research. What methods do you use to make sure you’re coming across clearly in an interview?

A: I try to put myself in other people's shoes — if I were interested in someone else’s science but didn’t understand it on a deep level, what would be helpful? For me, that’s trying not to speak in jargon, helping put things in context, and reframing the question. If someone's asking a question that may be leading to a misunderstanding or a misinterpretation, I pull back and add context. As I’m explaining, I check in with them often to ask, Does that make sense?

I get excited about the work that we do and I try to share that excitement but also not to oversell.

Q: I think being exposed to someone with different knowledge than our own can also help us understand that people have different types of knowledge. And in terms of the media and your interactions with reporters, it sounds like you respect the reporter’s knowledge.

A: Absolutely. I work in a very focused area of research. In contrast, a science reporter has to have this wide breadth of ability to chew on things — and some of these things are very complex. So I go into those conversations with that level of respect to understand that, Hey, this is probably a person who's pretty bright and probably has this job because they can absorb information and integrate it quite effectively. So let me help them.

Q: I’ve heard you incorporate science communication into the courses you teach at Kines. In what classes do you emphasize these principles and how do you do it?

A: I teach a graduate course called “Advanced Exercise Physiology” in the fall. In the winter term, I co-teach a course called “Physical Activity and Nutrition” with a colleague in the nutrition department. Most of the assignments for these classes are focused on different ways to interpret and communicate science.

For example, in my fall class, I ask the students to find a story covering findings from a newly published research paper and then critique the accuracy. They also assess whether the article felt biased or not and whether the writer provided other scientific evidence on the topic, or if they interviewed other researchers, to get a sense of how effective these stories really are at relaying the scientific findings.

In a different assignment, they read a newly published research article and then they become the lay press “journalist,” where they create the 1,500-word article as if it were to be published in a media outlet like Self magazine or The New York Times.

Q: That’s amazing. Why do you feel that it’s critical to give so many of these types of assignments?

A: I do it because communicating and learning how to communicate science — especially in this world of social media dominance, where we have all these influencers — is really important.

Students who are going into this field need to be able to dissect crap from reality. In the world more broadly, we need a lot more people who can do that better.

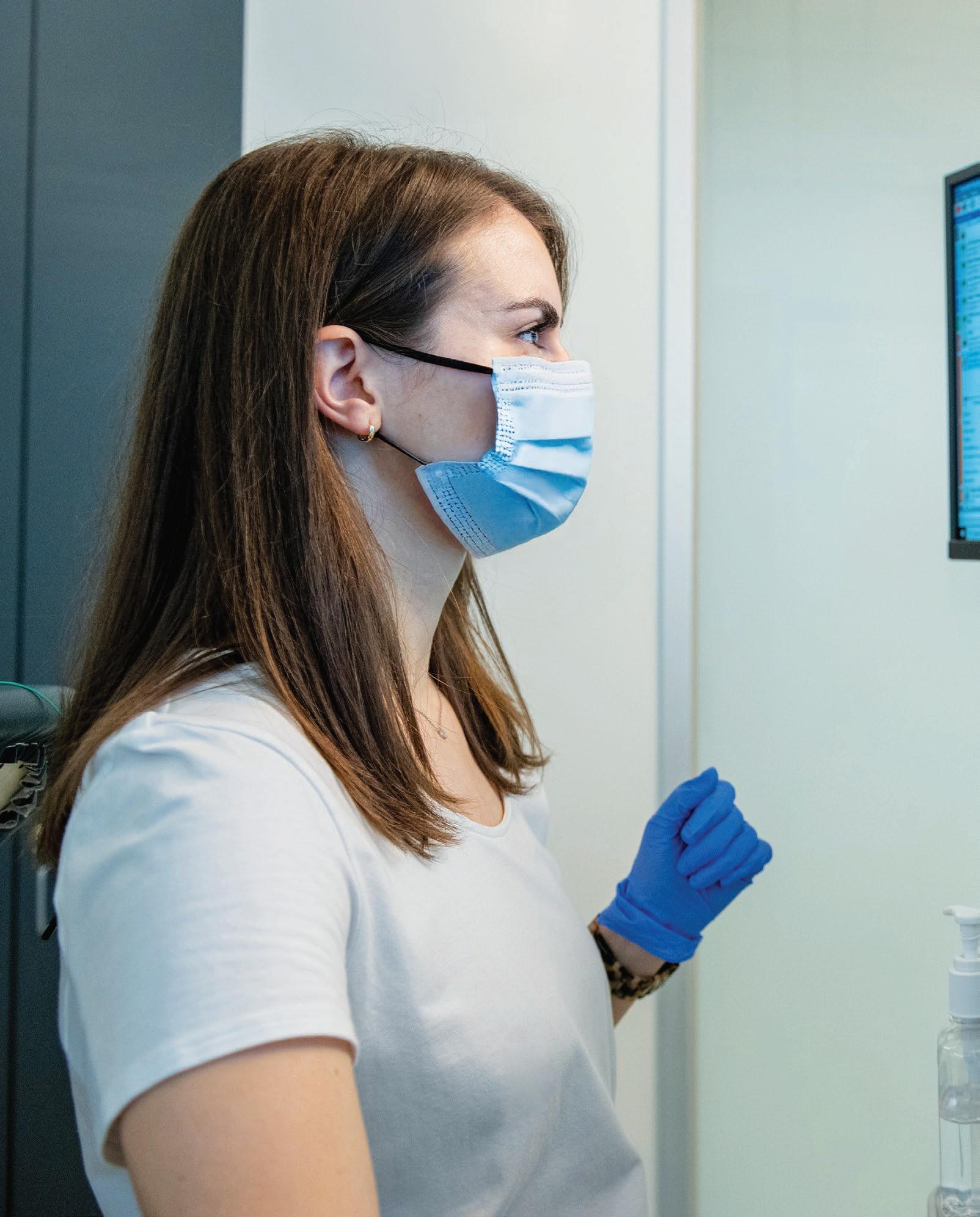

Students conduct exercise testing for student-athlete Ian Hill through the Human Performance & Sport Science Center.

The Human Performance & Sport Science Center is using data to help college athletes level up their training and students level up their career preparation.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

Inside the Human Performance & Sport Science Center (HPSSC)’s newest lab, Ian Hill is running.

The treadmill’s eight-mile-an-hour pace is easy for the senior cross country runner compared to the speeds he’s used to clocking on the track or the cross country course. But that’s the point: The staff at the HPSSC Athlete Innovation Lab (HAIL) are testing Hill’s running economy, or how efficiently he uses oxygen while running at different speeds.

From a bright blue mask strapped to Hill’s face, wires wind toward a pair of monitors on a mobile workstation. Waveforms frolic across one of the screens, communicating Hill’s rate of oxygen uptake in the language of sport science.

HPSSC’s athlete innovation program coordinator, John Chase, is peering at the shifting lines, as are the two students next to him.

The students understand the principles of exercise physiology, but they’re here — as part of HPSSC's new experiential learning program, the Athlete Innovation Initiative — to learn how to apply that knowledge to elite athletes.

Thanks to funding from the Office of the Provost and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Michigan Medicine, plus a partnership between HPSSC and the Athletics Department, University of Michigan students interested in sport science can now apply for semester- or year-long experiential learning opportunities either: 1) conducting and interpreting tests assessing student-athletes’ athletic capacity in the controlled environment of the lab or 2) monitoring the student-athletes’ performance during practice and games, using wearable devices that measure metrics like player load (how much effort an athlete is exerting in a given time period).

by

“We’re trying to create meaningful training opportunities for students who are interested in pursuing a career in sport science,” says Ken Kozloff, a professor of kinesiology, orthopaedic surgery, and biomedical engineering and the co-director of HPSSC. “These experiences provide students with not only a technical skillset but also exposure to the highly collaborative and cross-disciplinary elite sport environment, which can only be learned through direct interaction with teams and coaches and student-athletes themselves."

The Athlete Innovation Initiative is the latest iteration of HPSSC’s efforts to cultivate an inclusive, human performance-centric community and to develop innovative academic frameworks for students interested in sport science.

For example, if a team sees an increase in lower limb soft tissue injuries, Chase and some of HAIL’s 13 student assistants might recommend a gait analysis to see whether certain players show asymmetries that could place them at higher risk for that type of injury.

Once the students working with the wearable devices (called “applied sport science technology assistants”) compile a season’s worth of on-field, in-game data for those players, “we can assess potential relationships between device-based measures and the student-athletes' on-field performance," Chase says. "Then we can provide teams with additional data-driven context to help guide their training decisions.”

“My goal is to let these students learn on their own with a little bit of a push here and there, whether it’s kicking things up a notch or letting them know if they’re getting a little too comfortable — because if you’re comfortable, you’re not really learning.”

“I’ve always been more of a proponent of experiential learning than being in a lecture room,” says Ivan Palomares-Gonzalez, HPSSC’s athlete innovation lab specialist. “My goal is to let these students learn on their own with a little bit of a push here and there...letting them know if they’re getting a little too comfortable — because if you’re comfortable, you’re not really learning.”

- IVAN PALOMARES-GONZALEZ

Ideally, the partnership will help optimize training for the student-athletes while minimizing disruptions to their busy schedules. HAIL is located on the lower level of the Stephen M. Ross Athletic Campus’ Performance Center, which houses training facilities for nearly two-thirds of Michigan’s student athletes, so it’s easy for many athletes to get to the lab for testing without interfering with time spent in class or on the playing field.

In both the lab and on the field, students participating in the Athlete Innovation Initiative are providing data to U-M’s athletic teams that could help shape individualized training, recovery, and return-to-play plans according to the student-athlete’s individual needs.

“There is great potential for Athletics and Kinesiology together to be at the forefront of sport science in collegiate athletics,” Chase says. “Not many places are doing this.”

To start, Chase has been meeting with the staff for each team to determine their current needs, and then tailoring assessments accordingly.

“None of this would be possible without the studentathletes,” Kozloff says. “One of the things that we’re constantly trying to remember and remind others of is that they’re students, too. And they have this massive amount of time that they are on the field or in the training room. So we’re trying to gather the most actionable data in the least burdensome way, so that they can still get to class, practice as they want to, and perform at their best in all aspects of their life.”

Above, the Human Performance & Sport Science Center team, from left to right: Ivan Palomares-Gonzalez, Susan Rinaldi, Ken Kozloff, Ron Zernicke, and John Chase.

Faculty member Kara Palmer asked her motor behavior students to apply a semester’s worth of knowledge to an unexpected setting.

Kara Palmer likes to experiment. So when the clinical assistant professor started receiving a lot of accommodation requests from students for final exams (and was brainstorming how to better design effective exams in the age of generative AI), she decided to switch things up, starting with her Applied Exercise Science 332: “The Principles of Motor Behavior”course. Instead of a traditional exam, she reserved U-M’s Yost Ice Arena for one and a half hours and took the AES 332 class ice skating.

The students were then required to write a series of five essays reflecting on the activity, applying concepts and theories they’d learned about in class to their experience, and laying out how they could further their skating abilities using motor learning concepts. “I wasn’t sure how it would go,” Palmer says, “but I was so pleased and impressed with how the students were able to showcase their course knowledge, from both theoretical and applied lenses.”

Keep reading for a few samples of the students’ explorations — both physical and cerebral.

—

MARY CLARE FISCHER

“In order to ice skate, I had to control several degrees of freedom (DOF)* like joint angles, muscles, and motor units to get across the rink. This range of DOFs comes with a dilemma, which is that it creates a large calculative burden on me to determine the most efficient DOFs to lock and unlock. For example, how well am I able to skate with my hips internally vs externally rotated? With my shoulders abducted or adducted? With trial and error...I was able to determine the most appropriate DOFs to control.”

–Elly Lynch, junior, pictured above, middle

“In order to successfully ice skate around the beautiful Yost Ice Arena, myself, my classmates, and Dr. Palmer all had to spontaneously adapt our motor patterns to achieve metabolically efficient movements within the relevant… constraints.”

–Will Haley, junior

*Degrees of freedom: The multitude of ways to achieve a desired movement.

“I, along with other beginners in the class, was in the cognitive stage, where performance is inconsistent and requires conscious thought and intense focus...When my focus wavered, even for just a moment, I came extremely close to losing my balance. Every stride required conscious effort and self-talk such as How far apart should my feet be? [and] How hard should I push compared to when I’m on skis?"

–Will Barhite, senior

“I’ve only skated a couple times in my life, so I tried to stay upright and move slowly. Meanwhile, Garrett [a skater on U-M’s varsity ice hockey team] was able to move effortlessly and powerfully, even performing a one-legged hockey stop.

[The] conceptual model of foundational movement skills… includes a socio-cultural and geographical filter, which helps explain the difference between my experience and Garrett’s experience. He grew up in a city in Minnesota where skating and hockey is a part of local culture. So, he had early exposure to the ice because he played hockey at a very young age. This led to the development of strong foundational skating skills, allowing him to move into the specialized skill stage…I grew up skiing, but not many individuals played hockey in my city so I never got into skating.” –Will Endres, junior, pictured left; junior Garrett Schifsky is pictured right

For the University of Michigan Concussion Center, outreach and engagement is just as critical as research and patient care.

“The people who need this information the most aren't in this space 24-7,”says

Steven Broglio, director of the U-M Concussion Center. “We have to share our knowledge beyond the university and with the broader community.” Read on to see how Broglio and his team are passing along their expertise and creating opportunities for dialogue with the wider public.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

In November 2024, the U-M Concussion Center unveiled a new addition to its fourth-floor suite in the School of Kinesiology Building: a striking mural featuring swoops of purplish-blue and yellow, light pink and lime green, that are overlaid with various markings, like groups of dots that look like footprints and eyelid-shaped curves in threes.

The mural was created by Avery Williamson, an Ypsilanti-based artist who spoke to previously concussed patients and caregivers, asking them to choose the colors and patterns that evoked different stages of their recovery.

The result was compelling, so much so that Katie Gunning, an administrative assistant for the U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance (SMTD), thought the mural could be a jumping-off point for further creative exploration. What if SMTD students performed solos based on their concussion experiences in front of the mural? she thought after reading a story about the mural’s artistic process.

In February 2025, five students did just that — one wearing black because of the black spots she saw after her concussion, another spinning around to communicate the dizziness she’d felt. “They were really trying to pull in how they were feeling with their movements, with their body positioning,” says Kristen Schuyten, a physical therapist with the SMTD Wellness Initiative who helped find eligible students for the performance. “Having it paint a whole picture in front of this amazing mural that already gave you a visual display.”

It’s the kind of work that Broglio wants to do more of, to help more people understand what it’s really like to undergo head trauma. “As a scientist, I can put a number to a lot of things, but that doesn’t describe the emotional journey of having a concussion,” he says. Scan the code below to watch the performance.

Safety Towns, with their makeshift streets and perennial orange cones, were a staple of suburban childhood for decades. But the camps are expensive to host and require a lot of staff, so many communities have struggled to offer them lately amid high inflation and tight budgets.

Enter Pop-Up Safety Town, a condensed, one-day version of the classic safety education program that U-M Concussion Center associate director and Michigan Medicine pediatric emergency medicine physician Andrew Hashikawa launched in 2017.

Hashikawa partners with school districts that have a Head Start center — a federally funded program that provides early learning, health, and support services to kids ages 3 to 5 from low-income families — to teach preschoolers about injury prevention concepts like helmet safety, medication safety, what to do in fires and floods, and how to interact with dogs. (He brings life-size stuffed dogs to help the kids practice the latter.)

Because some regions remain out of reasonable driving distance, Hashikawa and the U-M Concussion Center team launched a new initiative this past year, shipping Pop-Up Safety Town materials to designated resource centers across Michigan. Early care providers and preschool teachers can now borrow the kits for use in their classrooms. “It’s one of the ways the Concussion Center can really engage with the community,” Hashikawa says of Pop-Up Safety Town and his new Pop-Up Safety Town in a Box initiative. “We can continue to send a clear message that injury prevention is for everybody.”

“Pop-Up Safety Town in a Box” was made possible by one of Kines’ Donor Innovation Grants, which puts money given to our annual fund toward innovative projects. If you’re interested in supporting the U-M Concussion Center, contact chief development officer Robin Stock at rmstock@umich.edu

If your child hit their head during a Saturday morning soccer game, would you know what to do or where to seek care? There’s a new resource for that.

In partnership with the Toyota Move Forward Fund — which aims to strengthen access to care and injury recovery support — the U-M Concussion Center team developed the Concussion Navigator (concussionnavigator.org). The website provides guidance for parents, coaches, and administrators through an easy-to-follow education module, a symptom tracking tool, and a map with concussion care providers in Michigan.

“In Ann Arbor, we have access to some of the best medical care in the country,” Broglio says. “But a lot of the state is reasonably rural — you get into the thumb or by the Bridge, and they don’t have the same resources that we do here. So we want to make sure people have the relevant information at hand [when someone they know gets a concussion] and they know where to go to seek out expert help.”

There was a time when sports venues simply housed sports (and maybe a few concession stands). Now, the narrative — and strategy — has changed. Stadiums are seen as hubs of all types of entertainment, with teams using creative methods to draw a variety of fans and cities investing in sports venues as ways to build community and boost economic activity.

“One of the biggest ways in which the global sports industry is changing is the function of professional sports venues as real estate assets,” says Judith Grant Long, an associate professor of sport management (SM) and the co-director of the University of Michigan Center for Sports Venues & Real Estate Development. “There’s a lot of money and thinking going on in this particular realm.”

The U-M Sport Management Program has planted the flag as a leader in sports venues research and education. The applied research seminar for seniors shows why.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

The U-M School of Kinesiology has been ahead of the curve(ball) in this area, with Long and SM professor Mark Rosentraub teaching a five-class sequence on sports venues for more than a decade. Compared to classes in this specialty at other universities, U-M’s focus more on the development and community impact of sports venues compared to just facility management.

“U-M offered the first courses to consider sports venues as a real estate asset and to examine the whys and hows of their development, alongside the more traditional focus on facility operations,” Long says. “Ours is the most intensive sequence that students can take in this subject area in the world, and we're very proud of that."

The sports venue track culminates in SM 443/543: “Sports Venues Applied Research Seminar, ” an optional capstone where a small number of seniors — and occasionally master’s students — work alongside Long to pinpoint a problem in the sports venue realm, collect or analyze data, and model a solution.

Long's winter 2024 class examined the state of venues across all four levels of minor league baseball, documenting information like when each venue was built, how much it cost, who paid for it, where it’s located, and whether it’s part of a mixed-use district (where a sports venue co-exists with retail, residential, and/or office space as part of a larger, planned district).

“We did this incredible inventory of data that’s not collectively available anywhere else,” Long says. “That coincides with our mission as an educational institution, but it also coincides with our mission as a public university to create or, in this case, assemble knowledge that is useful to people in the United States and beyond.”

The data will be published, hopefully by spring 2026, as part of a new, research-oriented book series focused on professional sports venues that Long is helming for Springer Publishing. Once it’s available, the information could be used by minor-league operations leaders, city planners, other sport management researchers, students, and journalists, Long says.

The project has already given the students tangible benefits. They learned how to gather information from primary sources like the minor-league teams and host cities (instead of relying on questionable Internet pages or often inaccurate generative AI summaries). They used software like Google Earth to conduct measurements of the minor-league sites and bring spatial considerations into their problem-solving. And they visited the minorleague Toledo Mud Hens’ Fifth Third Field to see how the data they’d tracked down translated to a real-life experience at the ballpark.

Long envisions the experience becoming even better over time. Once the Dr. Jonathan D. Rose Innovation Hub — an emerging and immersive technology lab currently being built out on the second floor of the School of Kinesiology Building — is up and running, she hopes to integrate the hub’s virtual reality software into the seminar.

“In a perfect world, our students who are interested in venues would be able to configure a stadium, determine its capacity, determine the percentage of premium seating, whether or not it has a roof, what location it's in, and then pair that up with a financial model of how the venue delivers a particular return on investment relative to changes in design of the venue,” Long says. “We’ve needed additional infrastructure and software to make that happen, and it will be really exciting for some of it to get under way with the Rose Innovation Hub.”

Read Judith Grant Long’s upcoming book.

So far, no book has outlined how sports venues get built. So sport management associate professor Judith Grant Long, an expert in the real estate development of sports venues, thought she’d write one — or several. Developing NFL stadiums: The business of stadium planning, finance, design, and delivery, out this fall, will be the first book in a series covering the development of professional sports stadiums. Compared to Long’s first book, Public-private partnerships for major league sports facilities, this one takes a broader view, using a blend of research and real-world examples to trace the development process all the way from the initial idea for a new stadium to the day its doors first open to the public.

Scan

When movement science faculty member Josh Mergos launched U-M’s Intraoperative Neuromonitoring (IONM) Program in 2012, it was the first time a university had offered accredited courses in the burgeoning field — a landmark step in education for those who wanted to pursue careers monitoring patients’ nervous systems during complex surgeries.

More than a decade later, there’s a growing need for more (and more highly skilled) surgical neurophysiologists, especially because the field has become much more sophisticated in its techniques and approaches. “We’ve found better and more robust ways to monitor cases, and that takes a lot more skill and knowledge,” Mergos says. To prepare graduates to operate at the highest level, Mergos decided to launch a master’s program (now called intraoperative neurophysiology, or IONP, to better reflect the dynamic nature of the job) under the Kines umbrella. The biggest draw of the IONP Master's Program: Students will spend their final semester completing a full-time capstone experience at one of several top-tier medical centers around the country. “We’re looking for committed, hardworking students who are eager to do hands-on, meaningful work from day one,” Mergos says. Already sold? Submit your application by Feb. 1 to be considered for the first cohort starting in fall 2026.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

The University of Michigan is on a mission to give more students access to international experiences. Here are some of the steps Kines has taken to expand their worlds, one trip at a time.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

Traveling out of the United States allows students to immerse themselves in new cultures, broaden their perspectives, make meaningful friendships and connections…the list of possible benefits goes on and on.

In fact, the University of Michigan considers global engagement such a transformative part of the college experience that the vice provost for engaged learning developed a strategic plan to increase the proportion of U-M students going abroad, with a particular focus on first-generation students (those who are the first in their family to attend college).

The School of Kinesiology has been very much on board, with our (newly named!) Warsaw Family Office of Global Engagement working hard to meet the goals. See how in the following pages.

STRATEGY: LAUNCH EQUITABLE AND ACCESSIBLE PROGRAMMING TO DIVERSIFY STUDENT PARTICIPATION

TACTIC: FIRST-TIME TRAVELER’S KIT

10 students were given kits with:

• Hard-sided suitcase sized for international travel with TSA-approved locks

• Insulated water bottle

• Travel pillow

• Luggage strap

• First aid kit

• Wall plug adapter

• Kinesiology-branded luggage tag

• Kinesiology flag

15 more kits will be given out this fall, with priority for students who have never traveled abroad.

Apply for a first-time traveler’s kit:

Traveler's Kit photos by Daryl Marshke/ Michigan Photography

TACTIC: BOOST AVAILABLE FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR KINES STUDENTS’ INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCES

$250,000: gift from Warsaw family

2x: the amount Kines’ funding for global engagement support has risen thanks to this gift

“Giving to a cause like this — that could allow students to be even sharper when they're engaging with other cultures — was really important for me. That will not only better them as a person and help them grow, but it is also going to give them an edge. These days, it's very competitive out there. So it’s important to have all the right tools at your disposal.” —Josh Warsaw, naming donor for the Warsaw Family Office of Global Engagement

STRATEGY: PROMOTE EARLY AWARENESS OF EDUCATION ABROAD OPPORTUNITIES

TACTIC: FIRST-TIME TRAVELER’S KIT EVENT

Date: March 28

Location: Distance Learning Classroom, SoK Building

Programming: For 10 students who received first-time traveler’s kits: passport application assistance from county clerks; passport photo station; study abroad fair with vendors sharing information about available programs; Japanese, Indian, and Mexican food from local restaurants

“Ultimately, the First-Time Traveler’s Kit award is more than just a chance to travel…The language skills, new experiences, and global culture I develop will not only advance my ability to manage a diverse team but also help me create an inclusive environment that celebrates everyone in professional baseball, which will help me take another step toward breaking barriers as the first female MLB manager!” —Sport management sophomore Dana Tritz

STRATEGY: DIVERSIFY OFFERINGS ACROSS THE INSTITUTION BY LOCATION AND FORMAT

TACTIC: FACULTY-LED EDUCATION ABROAD PROGRAM GRANTS

Date: July 18-Aug. 6

Faculty member: Clinical assistant professor Kara Palmer

Location: Johannesburg, South Africa

Program: 12 juniors and seniors worked at child care centers and learned about child health and movement development from a South African perspective

• Cost per student without grant: $8,000

• Cost per student with grant: $3,500

“The goal was to hopefully remove barriers so these students would self-select to travel — or at least that it felt like more of a real possibility because they had some of the required things to go on a trip.” —Elena Viñales, Kines' manager of culture, equity & community

STRATEGY: DEVELOP AND ENHANCE PRE-DEPARTURE ORIENTATION AND POSTEXPERIENCE REFLECTIONS

TACTIC: EDUCATION ABROAD RESOURCE GRANT

Project: Analyzing what students have learned from global engagement experiences

Team: Staff representing School of Kinesiology, Ross School of Business, Center for Global and Intercultural Study, UM-Dearborn Global Engagement, School of Information, and Center for Research on Learning and Teaching

Plan: Document the current evaluation process for students returning from abroad and analyze what these assessments are measuring — Is it students’ global perspectives? Their intercultural competence? How they expect their global experience to contribute to their career outcomes? — to eventually inform a university-wide tool that will assess global engagement.

In October 2024, Kines faculty members Laura Richardson and Erin Giles took 18 applied exercise science and movement science students to small towns in Italy and Greece that are purported to be “blue zones” (where a high concentration of residents live for a long time, sometimes upward of 100 years). They asked the students to journal throughout their trip and, upon their return to America, to translate those notes and memories into a creative work that encapsulated their experience. At first, many of the students were intimidated, unsure how to take such an artistic approach to a final project. But the results were incredible — reflective of a trip that everyone on it called “life-changing.” Here are just a few examples of the students’ creations.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Before: “I’m going into a line of work with a lifestyle that is often the opposite of what these little magic pockets of the world have to offer. I was curious to see if I could somehow take some lessons from the blue zone lifestyles, apply them to my future career as a physician, and improve my quality of life long-term.”

Beginning: “When we arrived, I took lots of pictures of the food and the way people eat. I was thinking, Maybe that’s the one thing. I was trying to find this one secret to their happiness.”

Middle: “At one point, we took a dance lesson, and all of us were looking at the instructor’s feet very closely thinking, OK, is this it? We were so focused on trying to get it right.

Later that night, we were eating dinner together, and there was a live band playing. We all slowly merged onto the dance floor and started doing what we learned. As the song progressed and more people came out, everyone relaxed a bit and got more into the music. There was this sense of community, where I’d never met most of these people before but I was dancing with them.”

End: “I started taking a lot more photos of the people — not even just the residents of the blue zones but the people I went on the trip with. All of us had never really talked before, but we became best friends.”

After: “What I took away was how everyone interacted with each other. They make the effort to be a friend to everyone. I realized that I could probably still live a long and happy life because it’s less about the type of beans in the food you eat and more about the people you surround yourself with.”

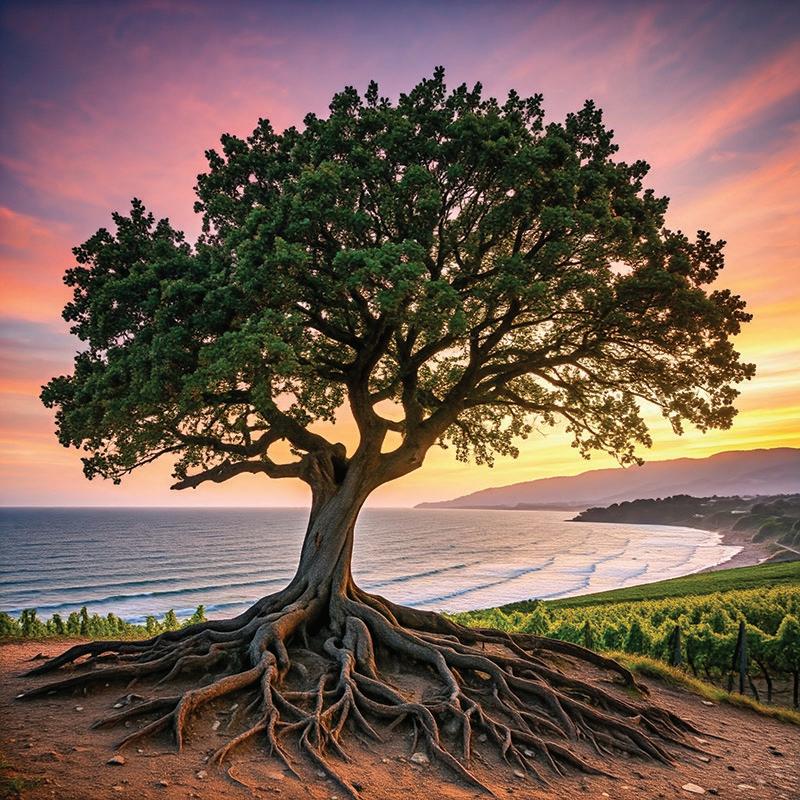

LEAVES

Theme: Living in the moment, one of the key attitudes shared by the centenarians

“The people of Sardinia and Ikaria are masters of this. They aren’t worried about the next day, the next week, or even the next year. That, I believe, is one of the secrets to happiness and to a long, fulfilling life.”

BRANCHES

Theme: Growth and resilience

“When winter hits, the people in these blue zones don't always get much food because they depend on their local crops and what's able to grow. I’ve learned from them that longevity isn't just about living without adversity; it's about enduring through it.”

ROOTS

Theme: Interconnectedness, both within family and the broader community of each blue zone

“At the dinner table one night, I shared that my grandmother and great aunt recently passed away. They both had chronic diseases. In this class, we learned about the fact that a lot of the people living in these blue zones don't experience chronic diseases the same way because of their health and lifestyle. I’m pre-med, and that’s pushed me down the path to want to treat people in a more holistic way. That’s a deep thing to share with people you just met, but we all got so close that we were willing to talk about things like that.”

THE SONG OF OUR FATE (EXCERPTED), SET TO JASON MRAZ’S “I’M YOURS”

So this was my favorite trip by far

All thanks to you, to you

Well, what’d we learn, you’re asking me?

Eat some barley and fish ovaries [Side note from Edwards: That was really weird]

Look into your gut and you’ll find long-gevi-ty

Listen to the nonnas on how to roll and knead

We ate like family

And it’s our godforsaken right to live long, long, longly

So this was my favorite trip, by far

All thanks to you, to you

And it’s so surreal, all the inside jokes we’ve shared

This trip was fate, I’m sure

We had breathtaking views while doin’ yoga

Made some Greek food with Athina our fave, yeah

We learned how to count six [Side note: This is a dance we learned]

Danced after too many sips

Friday was the saddest ‘cuz it suddenly hit me

The joy I’d felt was finally ending

But we went out with a sunset view

‘The pool was heated’ NOT true! [Side note: Our friend Sawyer jumped in the pool and we told her it was heated, but it was ice cold]

I can’t even put into words

Though our time was short

This, oh this, oh this, was our fate, I’m sure

Listen to Edwards’ full rendition of his song

In the donor-funded Jones Movement Scholars Program, students have enough time, money, and support to see what a research-focused career is really like.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

When Tom Jones walked into his first meeting at the U-M School of Kinesiology, he brought along a principle: The best philanthropy follows people, not plans.

The retired insurance executive and U-M alum — who’d already given sizable gifts to the U-M Ross School of Business and Michigan Medicine’s neurology department — had enough experience to know that the best results come, as he says, when you “find out where people are going and try to help them go there — not tell them where to go.”

So, when Jones met with Jacob Haus (associate professor, movement science), Michael Vesia (assistant professor, movement science), and Dominique Kinnett-Hopkins (assistant professor, applied exercise science), and they told him about their research on movement disorders and the needs of their students, he asked, “What would you need to be successful?”

A little over a year later, in April 2025, the Jones Movement Scholars Program launched off the back of a $300,000 gift from Jones.

The program provides a stipend for select students to work in the lab of one of the three involved faculty members full-time for a summer, with ongoing mentorship for one to two years. Additional funding is available for conference attendance or other professional development, and there’s a community engagement requirement to ensure the students better understand the experiences of the patients they’re interacting with, who often have movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis.

“As faculty, our responsibilities extend beyond our frontfacing roles in the classroom,” Kinnett-Hopkins says. “Through this program, we’re able to share more about what research really involves, and students are able to experience the ups and downs, the challenges, and the excitement.”

In its first year, the Jones Movement Scholars Program is supporting three students: movement science and neuroscience senior Sophie Chong (who’s working with Haus), movement science senior Levi Kopald (whose mentor is Vesia), and movement science junior Brooke Bailey (who’s part of Kinnett-Hopkins’ team).

With the funds allocated through the program, all three were able to work on research full-time this past summer — a rare opportunity for undergrads.

“I’ve been working on a clinical trial, and a lot of the meetings with the participants are four or five hours long or even all day,” Chong says. “Being able to be in Dr. Haus’ lab all summer allowed me to go to every single one of those sessions, which I wouldn’t be able to do otherwise.”

This immersive research experience gives students more than just technical know-how — it deepens their understanding of complex scientific questions and the methods used to answer them, preparing them to take more advanced roles in the lab.

For Kopald, that has meant leading a project alongside one of Vesia’s PhD students; so far, he’s conducted the data analysis and worked on the abstract for a recent poster submission at an international neuroscience meeting.

“Because of the depth of their training, students like Levi aren’t just assisting — they’re truly contributing,” Vesia says.

Both Chong and Bailey said that no one in their family has worked in medicine or research, and they weren’t sure how to navigate these fields as a result.

“Pursuing a PhD or whatever I want to do in my future is like stepping into uncharted waters,” Bailey says. “But Dr. Dom’s been the best for that. She always sends me opportunities that I probably never would have found. Wherever I want to go, I know she will have my back.”

Jones’ gift is divided across six years, and the plan is to add three new Jones Movement Scholars each year, ideally overlapping the previous cohort so the new scholars can learn from the more experienced students as well as the faculty.

Kinnett-Hopkins, Vesia, and Haus have also discussed the possibility of expanding the program to include more Kines faculty members (and thus, more students) if all goes well.

Jones hopes his gift will ultimately serve as a gateway for more Kines donors to support experiential learning.

“I have big expectations for experiential learning at Michigan and what that means for the distinction between Michigan education and other education at this level,” Jones says. “In most cases, you have to be changing virtually all the time if you want to be a winner in terms of the marketplace or an educational institution, and I hope more people can help the university look forward and create a vision of the future.”

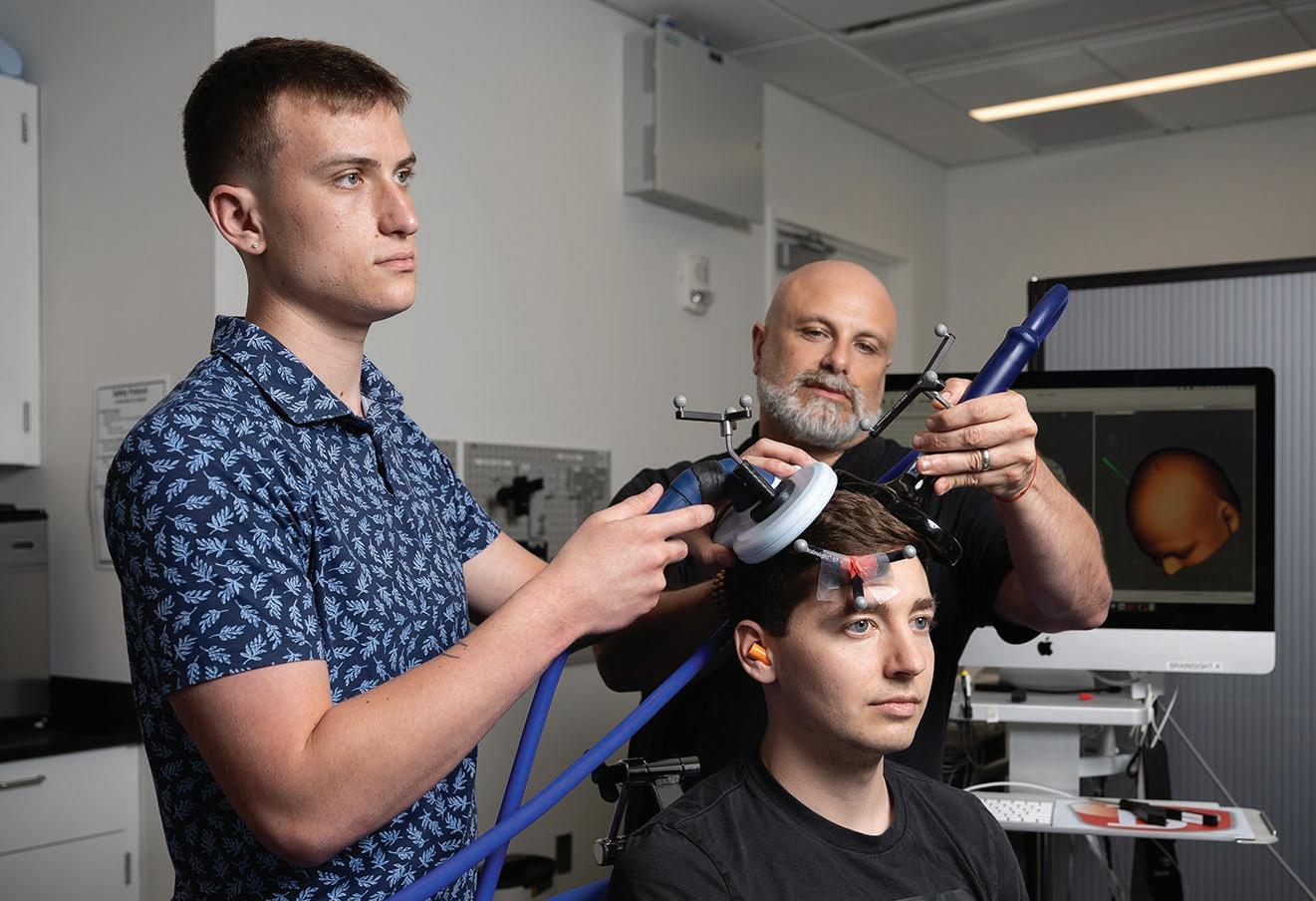

Clockwise from left: Faculty member Dominique Kinnett-Hopkins and Jones Movement Scholar Brooke Bailey (pictured right); Faculty member Michael Vesia and Jones Movement Scholar Levi Kopald (pictured left); Faculty member Jacob Haus and Jones Movement Scholar Sophie Chong (pictured left). All are demonstrating their research.

A quick summary of the research projects that the Jones Movement Scholars worked on over the summer.

Chong: Study in Parkinson Disease of Exercise Phase 3 Clinical Trial (SPARX3) — A large, multi-site clinical trial investigating the effects of moderate- and high-intensity aerobic exercise on disease progression in untreated patients with Parkinson’s disease

Kopald: Personalizing Multifocal Transcranial Direct Stimulation Dose to Target the Motor Network in Older Adults — A federally funded study aimed at understanding how the brain controls movement and how non-invasive brain stimulation can help reshape brain circuits to improve movement in people affected by stroke or Parkinson’s disease

Bailey: Promotion of Exercise through Physical Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis (PromPT-MS) — A pilot study investigating a new delivery model of physical therapy for increasing exercise and improving symptoms among people with multiple sclerosis; Multiple Sclerosis and Upper Extremity Function (MSUE) — A study investigating differences between patients’ self-perceptions of their hand function and their results on clinical assessments

Tom Jones’ gift supports the School of Kinesiology’s Every Move Matters campaign, which invests in initiatives focused on student success, faculty excellence, and innovation. Scan to see how you, too, can be a part of the movement.

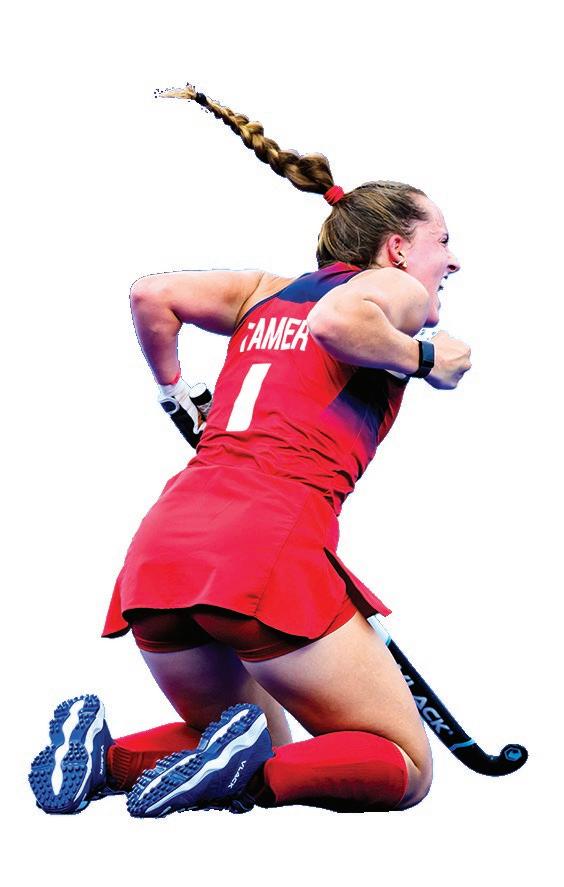

STUDIED: APPLIED EXERCISE SCIENCE (CLASS OF ‘25), NOW A SPORT MANAGEMENT MASTER’S STUDENT

COMPETED IN: FIELD HOCKEY

REPRESENTED: UNITED STATES

CHALLENGE: Coach asked her to commit to moving to Charlotte, North Carolina, to train before knowing whether she would make the roster

WIN: “I realized that the fear of failure was not enough for me to say no. I didn't want to get to the next summer when the Olympics was happening and feel like I should have been there.”

STUDIED: SPORT MANAGEMENT (CLASS OF ‘25)

COMPETED IN: SWIMMING (4X100M FREESTYLE RELAY, 4X100M MEDLEY RELAY)

REPRESENTED: HONG KONG

CHALLENGE: Tried to qualify for Tokyo Olympics — and missed the cutoff by less than a millisecond

WIN: “I remember I got out of the pool and stared at the scoreboard. I was like, Wow, is this what I get after training all these years? But my coach was like, Well, now you have another four years to train for the Paris Olympics. I didn't let the disappointment drag me down. The whole thing made me stronger.”

CHALLENGE: Got drenched during the opening ceremonies the day before her first race

WIN: “They gave us these plastic umbrellas that are transparent so everyone could see us. But then the staff were like, OK, guys, you have to put down your umbrellas when you're on camera, even though it's gonna pour and you're gonna be soaking wet. But it was actually a lot of fun. I didn't realize how many people were going to watch us. We went back and forth waving for half an hour straight.”

To be one of the approximately 10,700 athletes competing at the Summer Olympics every four years, you need skill, of course. But to succeed at this elite level of global sport, perseverance and willpower are a must, too. Two Kines students who breathed that rare Olympian air in Paris shared with us some of their sliding-doors moments, when they were faced with challenging situations in which they could have crumpled — but instead showed off their champion mentality.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

CHALLENGE: Broke her hand eight weeks before the Games

WIN: “That night, I was the most anxious I had ever been. I didn’t know if my coach was going to still name me to the roster, and that was frustrating because I’d felt pretty confident in my spot until then. But the next day, he told me I was making the roster anyway. I wore a bone stimulator for 10 hours a day to get my hand healed in time.”

CHALLENGE: Whirlwind of attention once the team qualified that worsened during the Games

WIN: “I sent messages before the tournament to anyone I thought would text me and, in a nice way, said, Hey, I’m not going to respond during this time. As a team, we collaborated on a post saying, Thank you for all your support, but we’re not going to be on social media. We had to shut it all out to focus.”

CHALLENGE: Knew the U.S. wasn’t progressing out of pool play once the team lost its fourth match — but still had to play the fifth and final match afterward

WIN: “To stay switched on when we knew we weren’t playing for a medal anymore, we had to frame it as: There’s points on the table. This is going to help our world ranking and help us in the long run. We ended up winning that fifth game and took a lot of pride in that.”

CHALLENGE: Had to deal with the pressure and attention that came with being one of just 35 athletes set to represent Hong Kong at the Paris Summer Games

WIN: “Right before the Olympics, I tried not to read the news or the comments because they can get kind of negative, and I knew that was going to impact me and my teammates. But then once I was there and looking at the stands and seeing how many people from back home traveled all that way to support Hong Kong — it felt surreal.”

CHALLENGE: Started getting tired and sick more often after Olympics

WIN: “Mentally and physically, I wasn't in the best shape, and I knew why — the break between the Olympics and coming back to school just wasn’t long enough. So I started seeing an athletic counselor through the U-M Athletics Department, and that helped me a lot. Now I understand how much time my body needs to recover and how important rest is to me.”

What do you do when the name of your student group includes a word that falls on the federal government’s banned words list? We sat down with the current student leaders of SBIC (founded as the Sport Business Inclusion Community) to talk about their perspectives amid the tense political climate, their vision for their group’s future, and how the sports industry could learn from the example they’re trying to set.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Given that SBIC was only founded in 2021, can you give our readers a quick rundown of the gap the group was intended to fill on campus?

Sharrow: The founders developed SBIC to create a more welcoming environment in the world of sport business for people of minority backgrounds. Our main goal now is to be a community for students interested in sport management to feel welcome and have a community of people they can bond with, while gaining knowledge and tools and networking opportunities in the world of sport business.

What has the group been up to the last couple of years?

Hamdan-Hashem: We do professional development events where we bring in speakers and go on treks. We also have mentorship programs, where we connect our members with industry professionals based on their career interests, and we work a lot in the philanthropy space.

For example, this year The SunBundle [an organization that upcycles athletic gear and provides resources to underserved communities] received the proceeds from Hoops for All, our annual basketball tournament.

There’s been significant political turmoil lately, and I’m wondering how you’ve reacted to some of the recent administrative changes that have occurred as a result.

Hamdan-Hashem: Historically, the University of Michigan has usually complied when it comes to the public political landscape. But the people that make up U-M are the ones who stand for justice or stand against those inequalities. It’s up to us — the students, the faculty — to try to make the tide turn. We want to unite people. We don’t want to divide people.

Hamdan-Hashem: We want to foster a tight-knit group of individuals based on different opinions. It's about diversity of thought, not diversity of individuals.

Sharrow: A lot of people are uncomfortable with perspectives that aren’t their own, and that needs to change. When you’re put in a place where there are people with differing opinions, it makes you grow. We’re hoping to institute discussions about sensitive topics within the sports industry — among us as a group but also with other clubs — so we can bring people to the table and hear those differing opinions. I think that will be beneficial for everyone.

Hamdan-Hashem: To his point: Human nature is to interact with one another, but it’s also to have disagreements with one another. We’re human beings, not human agreeings. This is literally how real life works. You’re going to be part of a lot of collaborative efforts, and people will have different things to say. At the end of the day, it is your job as an individual and as a collective to work it out.

Chung: I feel like people forget that you always have these disagreements in everyday life. I might think that LeBron [James] is the GOAT [greatest of all time], and maybe Milin thinks MJ [Michael Jordan] is the GOAT, but that doesn’t stop us from being good friends. Those are the little things in life that get forgotten in the broader landscape where people have different political opinions and all of a sudden they’re fighting because of that.

There’s been this perception that’s snowballed over time where you’re only allowed to share your opinions if they’re politically correct. To me, that just means you can say what you want as long as you’re not putting down another group. But some folks have now said they don’t feel safe to voice their opinion because somebody might take it the wrong way. What do you think?

Hamdan-Hashem: Constitutionally, we are allowed to voice our concerns and opinions. But if it comes with violence or putting other people down, at that point you’re not disagreeing. You’re insulting. That’s the fine line people have to follow.

If Hank were to come up to me and say, ‘MJ’s the GOAT,’ and I’m like, ‘No, you’re stupid, it’s LeBron,’ that’s missing logic; it’s all about emotional disagreement. If people use the logical processing that we’re all capable of, then a lot of arguments can be saved.

Sharrow: I think it’s hard because a lot of times with disagreements, you’re very emotionally attached to the topic. People do get really fired up about MJ versus LeBron. You’ve got to sit back and realize that while this opinion may seem stupid to you, it’s what they believe and you should respect that.

Chung: A lot of times, people nowadays forget that their conversation is about a topic, not the people or the person they’re talking to or engaging with. Like Milin said, you’re always emotionally attached to the things you support, which is a good thing. It’s a powerful thing. But I think people need to sit back sometimes and realize that it’s just a thing we’re talking about.

Do you think the sports industry is an opportune space to develop a level of fundamental respect while also disagreeing?

Sharrow: I think sports is a very good place for [civil] debates because there are so many different things you can debate. It can be something like who the top five quarterbacks are right now, but it could also be, say, if you want to build a new stadium: Where? How big will it be? What should we offer there? Debates are everywhere in sports.

Hamdan-Hashem: The only reason I’m pursuing a career in the sports world is because it’s so progressive and creative. But it’s about what’s at stake. In the NFL, if they want to try something out, they turn to the XFL or the UFL [United Football League] to have them pilot it and see how it works. If it works out in that low-stake area, then they bring it up. The sports world is progressive — but it’s only progressive on precedent. We’re interested in creating that precedent.

by

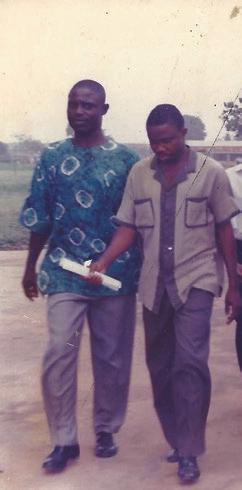

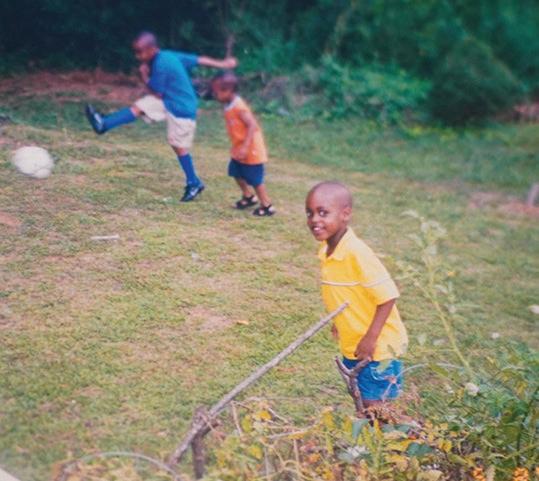

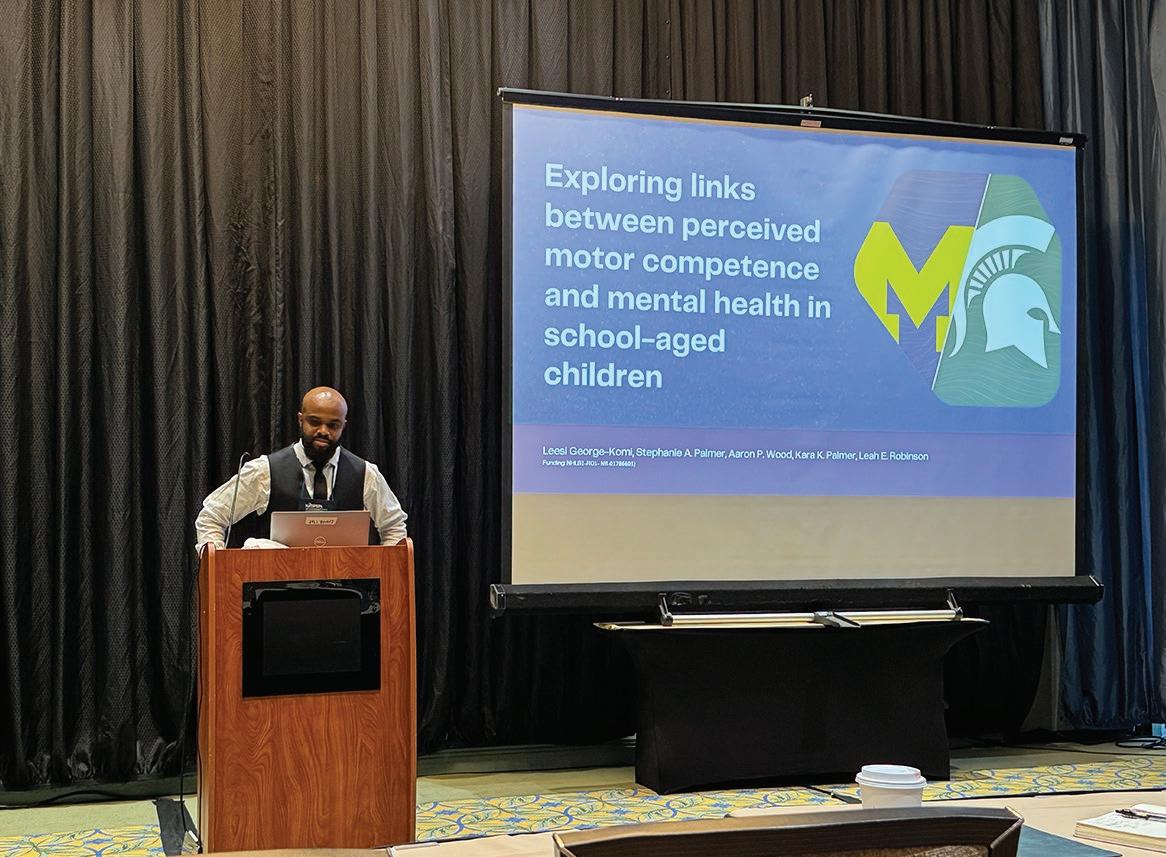

PhD student Leesi George-Komi is the son of Nigerian refugees who have persevered through political and environmental terror in their home country and racism in their adopted one. One of his responsibilities, as is Nigerian tradition, is to tell his parents’ story. But he’d like to go further than that — and use the lessons learned from his family’s experiences to change the next generation’s stories.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER AND LEESI GEORGE-KOMI

University of Michigan doctoral student Leesi George-Komi (pronounced LEH-see jorj CO-mee) sits on the floor of his parents’ home in Stone Mountain, Georgia, looking into the past.

A photo book lies open on Leesi’s lap. Three suitcases — blue, with a brown leather band around them — surround him, all full of more photos and historical ephemera. The luggage is clearly high quality; there are no obvious snags or stains. But they have no wheels, so they're old enough that their original owners must have carried them by hand.

“The three suitcases around, that’s what my parents were given when they came here,” Leesi says.

Leesi’s parents, George and Monica, fled Nigeria as refugees in 1996. They are Ogoni, one of the oldest ethnic groups in the resource-rich Niger Delta region. Some of the assets that came from their land were oil and natural gas.

But the Ogoni did not benefit from this wealth. Instead, the community had to advocate for basic rights, through a nonviolent civil justice movement. The crusade culminated in government-ordered murders of Ogoni leaders. If George hadn’t escaped, he could have been next.

“They now move very, very cautiously,” says Tombari, George and Monica’s middle child, of his parents. “The expectations were that we also move very cautiously.”

The photos stored in these old blue suitcases provide a time machine for Leesi, sending him back to the days when he and his parents were learning how to succeed in a foreign land.

He remembers LOGOS, a once-a-week after-school program run by the family’s church, where he was the only Black kid in his age group and regularly tried to play down traits that could be perceived as stereotypically Black, including physical traits and tropes.

I know you're my friend, his inner voice worried as he looked around at the other kids, but I don't want you not to be my friend in the future. And if I continue to beat you in these sports and games that we're playing — relay races, tug-ofwar — and make you feel bad…

The ruminating became a pattern. It was his sophomore year of high school when he first googled “anxiety symptoms.”

“I would start worrying about how I was saying something and how the other person is going to interpret it and then that consistent worry about the next steps of the conversation would stop me from even engaging in conversations,” Leesi says.

“And then after that, you get the physical signs of sweating and shortness of breath, and you’re thinking, Oh, shit. Now they know I’m nervous.”

Understanding that there was a name for what he’d been dealing with was helpful, but he didn’t know what to do with the information.

What do I…Who do I… he remembers thinking. I guess I can go to my parents and tell them, but I know how we view our society. I know how things go.

Being the firstborn male in the Ogoni tradition comes with added duress — you may inherit more money and land but you'll also have the responsibility of taking care of the family and the burden of blame if something goes wrong.

By the time he was in high school, Leesi felt like he served as an additional parent, trying to set a good example for Tombari and their younger brother, Bariture, while mediating between the two of them.

“I put a lot of pressure on myself to be the model first child,” Leesi says. “That’s Nigerian culture. And so, if people don’t get me, then I’m doing a disservice to my family.”

Every day when Leesi had finished his homework, he and Tombari would knock on neighbors’ doors, gathering their friends for the best part of the day. Together, they’d all walk to a basketball court or a football field, gabbing about their favorite sports stars: LeBron, Kobe, Atlanta Falcons wide receiver Roddy White.

“We were walking everywhere to play a sport, farther than our parents would have ever allowed us to go,” Leesi says. “It was all just because we liked our friends, we liked the people in our neighborhood. I wasn’t particularly good at basketball at the time.

But I was going to stick around to play because this was my social mechanism. This is how we coped with our life. That was such a large component of my childhood and how I built relationships with people that I cared about.”

Bariture was five years younger than Tombari and seven years younger than Leesi. Playing basketball with his brothers would become one of his favorite sports memories.

“I felt like nobody could touch me during those times,” Bariture says. “We’d trash talk, but I knew for sure my brothers would never let anyone try to disrespect me.”

“As emotional as sports are, they’re also cathartic,” Leesi says. “After it’s over, you guys can just be friends and wash away the issues you had. I realized that physical activity makes you feel good not just in physical ways but psychologically as well.”

After earning a bachelor’s degree in exercise and sports science at the University of Georgia, Leesi worked as a tech for an ophthalmology clinic in Atlanta in preparation for medical school. He wanted to specialize in orthopedic surgery or sports medicine long-term but figured he could gain from any experience in a medical setting.

Yet the clinic instead opened his eyes to the reality of American healthcare. It served neighborhoods that were primarily home to minority and/or low-income Atlantans, and the endless bureaucracy and inanities of insurance frequently kept these patients from getting the help they needed.

Leesi thought he could be a good doctor. But given the time and money to become one, coupled with the systemic problems that built up barriers to care, he realized he wouldn’t be able to have the immediate impact he’d been hoping for.

On a whim, he applied to a UGA master’s program in kinesiology so he could continue learning as he figured out a new career.

There, as a graduate teaching assistant, Leesi designed and taught sport courses to UGA undergrads, including “Beginner Volleyball,” “Beginner Tennis,” “Ultimate Frisbee,” and “Introduction to Weight Training.”

“He saw that he loved teaching,” Monica, Leesi's mother says.

“Physical activity is something I like to do, and kids love to do,” Leesi says. “I knew it made me feel good and made kids feel good. I always wanted to be a positive light for them.”

When Leesi spoke with his advisor, clinical associate professor Christopher Mojock, about the future, Mojock broached the possibility of a PhD. He pointed to Leesi’s work as a research assistant for Mojock’s doctoral student during undergrad, when Leesi ran a 10-week exercise class for older adults.

If you care about education and teaching, if you care about research and you enjoy creating a program to help people, this could be an option, he said.

The first year of Leesi’s PhD at the University of Michigan had allowed him to connect many themes — discrimination, mental health, childhood experiences, physical activity — and gave him ideas to apply to his own research and dissertation.

But it had also been a grind. There were a lot of late nights as he tried to prove he was worthy of his status as a U-M doctoral student.

And he felt lonely, away from all the community support, both friends and family, that he’d had in Georgia. There were a lot of thoughts of: Damn, am I good enough to be here? and Is this a place where I can really thrive?

Then he had a conversation with Jackie Goodway, the president of the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity (NASPSPA) at the time.

We need you in this field, she reminded him.

“She believed in me,” Leesi says. I can do this, he thought afterwards.

Leesi stands at the front of a conference room on the fourth floor of the U-M School of Kinesiology Building. All the seats are taken as U-M faculty, staff, and fellow PhD students crowd in to hear what Leesi has planned to propose for his dissertation research.

He comes off confident, fist bumping and hugging a few people as he gathers his notes. In reality, he’s sweating so much that the notes he’s holding become soggy.

“Good afternoon, everyone,” Leesi says. “Thank you for being here today.”

Leesi talks about the ways that marginalized people often protect themselves against mental distress, highlighting the importance of a strong ethnic-racial identity and supportive relationships with peers, siblings, and/or parents.

“But few studies have centered children’s voices to understand their perspectives on sports,” he says, “and how sports can be used to buffer the impact of stress on their mental health.”

In a gym at an Ypsilanti charter school on a Saturday morning, children ages 5-14 are shooting basketballs and chucking Nerf footballs at each other.

As parents and guardians bring more children in, they’re greeted by Justin Harper, a bald man with a scraggly beard whose eyes light up when he talks to kids. Next to chat with them is often Leesi, who hands them a flyer with the title, “Wondering if youth sports helps decrease diabetes risk?” and tells them about the study he’s conducting.

As part of his dissertation, Leesi has secured a grant through the American Diabetes Association to examine whether physical activity decreases risk factors for diabetes, which include obesity as well as anxiety and depression.

Here at CLR Academy (CLR), a youth program that primarily focuses on giving minority students in the Ypsilanti region a place to be active, he’s looking at whether CLR participants improve in any of those risk factors and how many sessions are needed to have an effect.

“All right, huddle up,” says Justin Green, a CLR coach, and all the children and a few adults form a large circle.

The kids are squirming, ready to get into the day’s activities. But he asks them to wait as he poses the day’s question: “What is stress?”

“Where you’re going under a lot of pressure,” one kid says.

“Yes,” Green nods in affirmation. “Now we’re going to split up into two groups and talk more about that.”

The kids form two smaller circles, separating naturally into age brackets, each with two adult coaches. Everyone says their name, most in whispers that are difficult to hear. A coach asks what situations might cause stress, and the answers become a little louder: tests, tryouts.

By the time the conversation turns to ways to cope with stress, the older kids’ voices have become more confident.

“Take deep breaths,” one says.

“ASMR videos,” another pipes up.

“Fidgets,” a third offers. “I have stress problems sometimes, and my teacher gives me fidgets.”

The children then scatter for warm-ups: lunges, high knees, butt kicks. Leesi shouts out praise to one child, who’d kept to himself in past sessions — but is now hanging with some other kids.

This is a condensed version of "This Is Our America." To read the full story, including about the harrowing journey of Leesi's parents fleeing Nigeria, scan here.

while other female students in the ‘90s were getting their steps in on the U-M gym’s new Stair Master, Colleen Scrivano (MVS ‘91) was out-benching the men. “They’d bench next to me and say, Wow, I failed,” Scrivano recalls. “I’d be thinking, No, you’re just not that strong.” Scrivano, a high school gymnast, taught herself how to lift from magazines like Muscle and Fitness. She made sure her children didn’t need to seek out fitness guidance by building an in-house gym with her husband and working out with her family, even on vacation.

In fact, Scrivano’s daughter, Katelyn Darkangelo (MVS ‘17), thought everyone worked out every day until she herself went to school at U-M, where her sorority sisters marveled at the amount of activewear in her laundry basket. Now Darkangelo, who owns the gym FIGR in South Lyon, is passing this culture of physical activity down to her 3-year-old daughter, Amelia. “Amelia already knows how to do squats and burpees and lunges, and she’ll go do the moves in my strength and conditioning classes,” Darkangelo says. “Fitness is so naturally embedded in our DNA that I’ve never thought to teach it to her. Since the time she could talk, it’s been part of her vocabulary.”

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Jedd Fisch, the U-M quarterbacks coach, helped Rogers land an internship with the Los Angeles Rams, through which she was able to chat with everyone who came through Rams training camp.

"I still can't believe how many people I know in the football world because of that one internship," Rogers says.

T HE G A M E O F

Two sport management alums rolled the dice to get into U-M then used their experience working in the U-M Athletic Department to land on the payday square, snagging broadcasting roles for professional sports teams at young ages. Follow our players along the board as we retrace the unlucky rolls and strategic success that has helped them win the ultimate game.

— AARON KASINITZ

Once Rogers enrolled in the U-M Sport Management Program, she hunted for job opportunities in the Athletic Department. Soon, she was serving as a manager for men's lacrosse; reporting for the Big Ten Network’s Student U initiative (through which students produce work for live television); and creating social media content for the football team.

PLAYER

Dannie Rogers (SM '17)

TH E G A M

PLAYER

Zach Linfield (SM '23)

Dannie Rogers tore her ACL during a high school basketball game her sophomore season. After surgery, she traveled from her home in rural Monroe County, Michigan, to a rehab facility in Ann Arbor three times a week for treatment — and fell deeper in love with the city and nearby campus during each trip.

A few months before high school graduation, Zach Linfield collapsed playing basketball with his friends. Tests revealed a benign tumor in his left shin. Instead of trying to walk onto the football team at a small school as he’d hoped, he applied to U-M’s Sport Management Program. But on his 18th birthday, he received a rejection letter.

After graduating in three and a half years, Rogers hosted high school sports shows and reported on games for a TV station in Toledo, Ohio. On her off days, she reported for the University of Toledo’s men and women’s basketball teams free of charge to boost her experience.

When the pandemic left her without full-time work, she worked as a nanny during the week and snagged any on-air broadcasting opportunities she could find on nights and weekends.

In January 2021, Rogers’ fortunes changed. Fisch had accepted a role at the University of Arizona, and he called to offer her a spot as the lead reporter for the football program. “He was like, It's time to go,” Rogers says.

But a few months after Rogers moved to Arizona, a job as a Lions reporter opened up. The role included creating content for the team’s website and social channels and sideline reporting during the preseason. Rogers couldn’t turn down the chance to work in the NFL, especially with her hometown team.

Linfield was accepted to U-M’s flagship campus after his first year of college and began calling baseball games for the student-run radio station. By his junior year, he was the station’s play-by-play football broadcaster. “At this point, I knew I was calling games not only as a hobby,” he says, “but to do it as a career.”

In 2022, more than 200,000 listeners tuned in to Linfield’s radio calls for U-M’s College Football Playoff semifinal, and his social media following picked up steam. When the Detroit Tigers needed a public address announcer for a charity softball game that same year, Jake Stocker, the director of fan experience at U-M, connected him with the team.

Rogers’ eyes grew wide when she stepped onto the sideline during her first road game with the Lions in August 2021. She took a deep breath and glanced around the Steelers’ iconic riverfront stadium as the national anthem rang out. Holy crap, she thought. I cannot believe this is my job.

After graduating from U-M, Linfield was working a manufacturing job in April 2024 when he received a call from the Tigers. Their normal public address announcer had fallen ill, and the backup was busy. Could Linfield fill in on short notice to announce his first Major League game?

In January, Linfield auditioned for the job as the Tigers’ regular public address announcer. The team gave him a much better birthday present than U-M had just a few years before: They called to say he got the gig. “I feel like everything [at U-M] had such a big impact on where I've landed today,” Linfield says.

Six months later, Linfield was in North Carolina working for a broadcasting company when his hometown baseball team called again. They needed a fill-in PA announcer for two playoff games. He hopped in the car and drove more than 10 hours to Detroit.

A photographer once asked Poplawski to run from one corner of a room to another but to make it look high fashion. "Honestly, I think it’s one of my best pictures,” Poplawski says. "And it’s probably because I thought about where my body should be in different parts of the running position, like I’d had to do in class.”

Alexa Poplawski (AES ‘25) has excelled at both elite academics and haute couture, in part because her knowledge of movement has elevated her eye-catching looks as a model.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

You’re lucky you’re pretty.

I don’t understand how you got into Michigan.

Oh, you model! And you do school? So do you just not care about school as much?

These are the types of disarming comments that Alexa Poplawski (AES ‘25) has had to deal with since her first year of high school, when she walked in her debut New York Fashion Week.

It’s been difficult for many to comprehend how Poplawski’s CV can include both a shot in Elle magazine and the Kines award for “Applied Exercise Science Major of the Year.”

But the recent graduate, who’s now off to Columbia University for a pre-med program, hasn’t let the frustration of other people’s assumptions hold her back from doing everything she enjoys.

“I love learning in an academic setting,” Poplawski says. “But modeling makes me feel like my most confident self. You can love both things.”

To that end, Poplawski’s found that her exercise science education has enhanced her modeling work and vice

Sometimes the prejudice from the people who can give her jobs — but to her, that just means they’re not the right partners. “I've had agencies tell me I'm too muscular for them,” Poplawski says. “I can’t help that I have big shoulders. Arms is my favorite day of the week. Since I'm in high school, I did sports, and I'm not going to change. If I'm too muscular for you, I'm not the look for you.”

This year, Poplawski worked on building up her “book,” or portfolio of looks. As she worked through 12 photo shoots in 10 days, she began to run out of poses. “I thought about what muscles I'd already used,” Poplawski says. “Because then I was able to be like, Oh, I haven’t used my tricep; I should do something with my upper arm. Or calves? Do I need to go up on my toes? slightest movement can make the next picture different than the one before.”