UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF KINESIOLOGY | FALL 2024

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF KINESIOLOGY | FALL 2024

The latest artificial intelligence tools have arrived at the U-M School of Kinesiology — and we're exploring how much the new bots on the block can (and can't) change our reality.

A local soccer club owner opens the gates — and the books — to SM students PLUS

The alum who's (strength) coaching the Silicon Valley set

How does a model of a body compare to the real thing? That’s the question the “Art of Anatomy” mini-course prompted its students to explore.

The School of Kinesiology is adding new faculty at a record pace as its student numbers climb and its standing grows.

a Mother

Applied exercise science assistant professor Abbi Lane wants to empower moms to exercise their way.

What Does it Take to Run a Sports Team?

Sport management faculty member Mike Lorenc is helping undergrads find out through a new partnership with a local soccer club.

When you’ve spent decades as a researcher and educator, the work doesn’t really stop once you retire, especially for these beloved faculty emeriti.

16 Links to Kinship

In 2023, a small group of graduate students was bonding before school had even started. 18 Off the Diamond, Into the Rough

A cancer diagnosis may have taken Kaylee America Rodriguez off the softball field, but it hasn’t struck the sport management student out. 19 A Whole New Ballgame

How first-year student Sarthak Subudhi organized Michigan’s first high school cricket tournament.

20 Beginning the Knowledge Journey

Athletic training students get a primer on how to understand and apply the latest research. 22 Kines-Customized Therapy

In-house clinical psychologist Brett Smith meets students where they’re at.

Move & Improve

The Mobility Initiative pairs Kines undergrads with patients in Michigan Medicine's short-stay unit. 26 Speaking from Experience

SoK's two winter-start programs get special access to our network of experts and facilities. Here's what students said about the experience.

28

Alum Christopher Kelley has helped U-M's Adaptive Sports & Fitness program take its game to the next level.

30 Where on Campus is Alice Palmer Freeman?

When Sheryl Szady discovered that an old bust of a fellow U-M alum had gone missing, the historian went on a quest to track down the artifact.

As a personal trainer with Exos@Google, alum Brooke Harrison coordinates in-office fitness for the Silicon Valley set.

Recent grad Elana Goldenkoff hopes to use her movement science degrees to improve the public’s perception of government and science.

34 And the Award Goes to...

For Michigan Kinesiology alums, there’s no higher honor from their alma mater than this recognition.

36

The latest artificial intelligence tools have arrived at the U-M School of Kinesiology — and we're exploring how much the new bots on the block can (and can't) change our reality.

is published by the University of Michigan School of Kinesiology. Visit us online at kines.umich.edu/movement

Dean

Lori Ploutz-Snyder

Editor

Mary Clare Fischer

Writers

Sarah Cahalan

Mary Clare Fischer

Heather Guenther

Alla Katsnelson

Sarah Kuta

Aimee Levitt

Design, Art Direction & Illustrations

Stacy Getz

Photographers

Eric Bronson

Mary Clare Fischer

Erin Kirkland

Daryl Marshke

Angel Rose Sajan

Scott Soderberg

Leisa Thompson

Austin Thomason

Sydney Verlinde

© 2024 Regents of the University of Michigan

The Regents of the University of Michigan Jordan B. Acker, Michael J. Behm, Mark J. Bernstein, Paul W. Brown, Sarah Hubbard, Denise Ilitch, Ron Weiser, Katherine E. White, Santa J. Ono, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/ affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office for Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, institutional. equity@umich.edu. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

How does a model of a body compare to the real thing? That’s the question the innovative “Art of Anatomy” mini-course prompted its students to explore.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

The first thing the students saw were the bones.

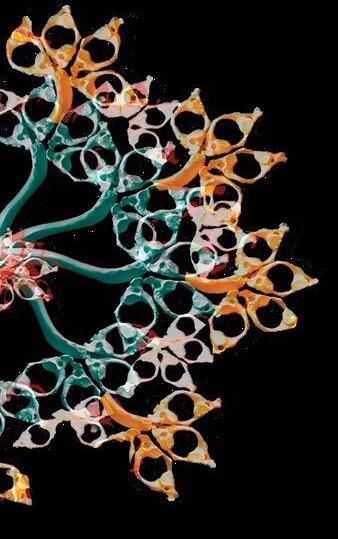

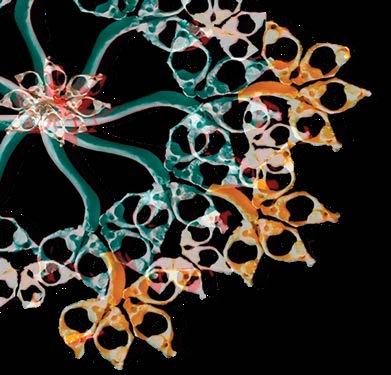

There were more than 100 of them, stacked neatly in plastic bins in the front of classroom 2060. From far away, they resembled china figurines. Up close, it was easier to tell they were 3D-printed versions of the same bones you’d find in a human pelvis or mouth or arm.

The students in the “Art of Anatomy” mini-course rummaged through the bins, deliberating. Their assignment that day was to create a sculptural arrangement. It could be anatomically correct; it could resemble nothing you’d typically find in a skeleton.

The activity was intended to explore the body from a different perspective, asking the question that lay at the core of the course: How does interacting with models of our anatomy, which try to approximate the experience of human bodies, compare to encountering the real thing?

The next hour or so was nearly silent, except for the clunking of the tiny bones. Maya Moufawad, a pre-dental and art major, had chosen two halves of a jaw, complete with teeth. She fit them together and affixed them to two smaller bones, as if the Flintstones had decided to display a dental mold as art.

Movement science student Abby Kramer went with a thoracic vertebra, a lumbar vertebra, and a sacral bone. She connected the lumbar vertebral bone directly with the sacrum, which was anatomically correct. But they were, both literally and figuratively, missing connective tissue.

Let’s

“I think everyone should see this,” she told movement science associate professor Melissa Gross, who’d brought Lee and other students to Italy as part of her “Art and Anatomy in the Italian Renaissance” course.

Gross had another idea.

“What if we made this a class?” she pondered. “Let’s have students make their own art with the bones they’re used to looking at.”

Gross had 3D printed a small number of bones for previous anatomy courses, so she knew it was possible. And she’d spent her career creating innovative interdisciplinary courses in an attempt to engage students in ways that worked better for them.

Together with Gear, she applied that paradigm of thinking to create the course. They wanted to ground it with an arts-based approach, using critical thinking to respectfully challenge assumptions and foster dialogue that valued different perspectives. “Our goal was to open the students’ minds to other ways of seeing, of moving, of experiencing,” Gross says.

have students make their own art with the bones they’re used to looking at.

– Melissa Gross

“We’re trying to get the students to understand that even the most factual anatomical model is still a fiction,” says Jennifer Gear, an art history and movement science lecturer who co-designed and taught the course. “It’s still removed from the body. In what ways and for what reasons? How do you stop thinking about these things as objective truths — but rather, to see them as believable fictions?”

When movement science student Regan Lee (MVS ’24) walked into the Capuchin Crypt in Rome, she was fascinated by the bones. The mausoleum is intentionally decorated with human remains from Catholic friars — skulls framing archways, tibias and femurs arranged in elaborate designs on the walls and ceilings.

Coincidentally, the U-M Arts Initiative was looking for proposals for its Arts & Curriculum grant, which promotes the integration of arts into course development and teaching, and gave Gross $19,611 to support the seven-week-long mini-course.

She and Gear used some of the funds to pay Lee, who began the arduous task of printing the bones. Even the smallest ones took hours, and the printers often malfunctioned.

But eventually, most of the bones made their way to classroom 2060, as did 20 students — some kinesiology majors, others specializing in engineering or art.

The students drew the bones. They paged through 16th-century books full of woodcut illustrations of bodies, their faces full of wonder. They manipulated a digital cadaver on the Anatomage table (a 3D anatomy visualization tool), working as a group to make decisions about how to examine the bones and muscles and tissues.

They talked about the ethics of using human bodies for research or education. In their reflection for that session, students discussed whether they would donate their own bodies to science, noting that it was rare for them to feel this comfortable talking about such a difficult topic.

It began to feel like a kind of alchemy was taking place on Fridays from noon to 2 p.m.

“Every single class, I found myself being encouraged to think deeper, within my own knowledge and with the help of my peers,” one student wrote in a reflection. “In fact, these discussions were so interesting to me that I always called my mom about them afterwards because I was so excited to continue the conversation.”

On the final day of class, the students had one last opportunity to see the bones in a new way.

The Emerging Technologies Group at the Duderstadt Center had taken the digital files used to 3D print the bones and uploaded them to their visualization platforms, including virtual and augmented reality set-ups.

Movement science student Gordon Luo held a VR controller in one hand, pressing a button that grabbed the bone on his computer screen and moved it around. Then he found a way to digitally measure the bone.

Art student Summer Pengelly and biomedical engineering student Angel Rose Sajan were wearing HoloLens headsets that projected the bones onto their surroundings.

In the back of the studio lay yet another digital environment to explore. Called MIDEN (Michigan Immersive Digital Experience Nexus), it projects images onto the walls and floor of a room. Users wear headsets that give them tools to manipulate the projections. In this case, students were able to slice a cadaver into different planes.

“MIDEN might be my favorite,” says Cece Crowther, now a biomedical engineering alum. “But I could call three different [sessions] my favorite in this class. Every class has been unique.”

As the students ate celebratory, bone-themed cake, they reflected on the course, sharing feedback like, “I will not stop recommending this class to people” and “I made my schedule around this class.” Several mentioned how much they’d gained by working alongside folks with different backgrounds.

“I appreciate this class so much because it normalizes the idea of art and science working together,” Moufawad, the art and pre-dental major, says. “There’s so much at the intersection of these two topics, and I love that this class celebrates that.”

Gross was giddy over the success of the course. Her eyes lit up and her tone became reverential as she talked about what she and Gear, with the help of committed students, had managed to achieve.

“This experience we spent so many hours designing and thinking about, it actually worked,” Gross says. “It’ll take time to unpack what was so empowering for so many students, but it’s a big fulfillment for us as teachers.”

“Delight,” she says, “is too soft a word.”

The Art of Anatomy course was made possible by a grant from the Arts Initiative at the University of Michigan to recipient Melissa Gross. Main bone art image by Angel Rose Sajan. Clockwise from top left: Movement science student Ariana Ravitz builds a sculpture out of 3D-printed bones; students use virtual reality tools to slice a cadaver into different planes; movement science associate professor Melissa Gross shares her infectious excitement.

The School of Kinesiology is adding new faculty at a record pace as its student numbers climb and its standing grows.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

The U-M School of Kinesiology had a plan to grow — steadily, organically, strategically.

Step one: Move into a historic yet beautifully redesigned space (the old Kraus Natural Science Building) on the Diag. This would not only allow the school to fit all its faculty and staff under one roof for the first time but also further increase its footprint to match its growing status on campus.

Step two: Hire more faculty, in part around specific research topics, like sports analytics and exercise and cancer, that current faculty members had proposed as areas where they’d like to raise the school’s profile.

“We were very intentional,” says SoK Dean Lori Ploutz-Snyder. “But lo and behold, if that wasn’t stymied by COVID.”

The hiring freeze that U-M initiated at the beginning of the pandemic meant SoK’s best-laid plans had to be paused. The delay was one of several factors that has created pent-up demand for more SoK faculty, including rising student applications, the transition or creation of select school programs, and the announcement of high-profile retirements.

But over the past few years, SoK hit play again. In 2023, the school hired a record four lecturers and eight faculty, many of whom specialized in the research areas in which SoK had wanted to expand.

And in 2024, SoK launched faculty searches for every program, including ones for an endowed position and a broad inquiry to find senior faculty who might fit into the SoK ethos in ways the school couldn’t yet envision when mapping out priorities five years before.

“We’ve interviewed more people this year than we ever have,” Ploutz-Snyder says. “We were hoping to get some real force multipliers that would elevate parts of the school or even the whole school.”

“It’s been a whirlwind,” says Lori Helvey, executive director of finance, planning and operations. “But we’re really trying to get ourselves up to the capacity we’ve been planning for over the last eight years.”

It’s become more and more competitive to get into the U-M School of Kinesiology over time.

Graduate applications have nearly doubled in the last four years. Less than 15% of first-year undergraduate applicants were accepted for the 2024 fall semester.

“People want to come here,” says Charlene Ruloff, graduate student affairs manager. “They recognize the value of a kinesiology degree from the University of Michigan.”

Despite the selectivity, SoK’s enrollment has grown. Although there are limits on the number of new undergraduates each fall because U-M guarantees

housing for first years, the school has found creative ways to expand.

In 2019 and 2022, SoK created winter-start programs (see more on page 26), inviting select applicants who were waitlisted in the fall to begin their U-M education in the winter and take spring and summer classes to catch up with their peers by their sophomore years. SoK’s athletic training program transitioned to a master’s program, as mandated nationally, in 2021, freeing up more undergrad spots in the other programs. And 2024 saw the highest number of new SoK transfer students in the last decade.

But more students means more class sections and thus more faculty required to teach the courses. Some of SoK’s 2023 hires were clinical faculty intended to focus mostly on teaching because the demand was so great.

The addition of more spring and summer classes for the winter-start and athletic training programs particularly affected logistics for the school, with the number of courses offered during those semesters rising from two in 2015 to 25 in 2024.

“We never used to ask about spring and summer when we were advertising positions,” says Jacquie Niven, SoK’s director of human resources. “Now we tell candidates they have the opportunity to earn some additional money in the spring and summer because we have that need.”

Retirement announcements from several long-tenured faculty have only added to the urgency in hiring; there became an imperative to find not only fresh faces but also experienced academics who could help lead SoK’s next phase of growth and innovation.

Yet the school looked at these upcoming transitions as an opportunity to go beyond filling veteran spots. By sending out calls for senior faculty in any area of kinesiology, SoK hoped to diversify — and further elevate — its expertise.

“We wanted to hire people who were doing more innovative, cutting-edge research,” says sport management associate professor Kate Heinze and one of the chairs of the search committee for the Bickner Chair, a prestigious endowed professorship position open to the senior-level candidates, “people who had ideas about the kinds of things they could do if they came to U-M with its resources and potential partnerships and interdisciplinary collaborations.”

“But it’s really tricky at the senior level to get folks to take a sincere interest because of family and all sorts of things,” she continued. “Our HR staff did a fabulous job.”

SoK manager of academic human resources Jess Jones is in charge of faculty searches. She and the rest of the team wanted to get as many people involved in the process as possible to help candidates understand SoK's culture right from their first interaction.

Staff from all areas of the school showed the candidates around. Students from different majors and degree levels sat in on candidates’ presentations and had lunch with them. Faculty from each program were on the search committee for the Bickner Chair to make sure that the candidates for that position could complement multiple areas.

“We’re all getting a say in the people that we bring here to define how we want to see U-M Kinesiology going forward,” Jones says. “It’s been more challenging to organize because there are more people involved, but I believe it's been valuable and demonstrated that we’re all invested in the growth and the vision.”

Besides being more inclusive, the approach was also effective. SoK hired three new program chairs (who are leading the movement science, applied exercise science, and sport management programs, respectively), including one who will serve as the Bickner Chair; an athletic training and movement science clinical faculty member; and the school’s first position through the Michigan Program for Advancing Cultural Transformation (M-PACT), which recruits faculty whose research, teaching, and service interests are underrepresented in health care.

“The growth has been explosive but in a good way,” says Niven.

“I hope the trend continues for the next couple of years, so we can continue to deliver our curriculum in a firstclass way,” says Ploutz-Snyder.

Applied exercise science assistant professor Abbi Lane wants to empower moms to exercise their way.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

When applied exercise science (AES) assistant professor Abbi Lane was working at the University of South Carolina, she conducted a study of new mothers’ heart and metabolic health. Some moms would come in laughing about the chaos of parenting while others were struggling with recovery after a difficult labor, pregnancy, or pregnancy loss. “We realized that no pregnancy is the same,” Lane says. “It was then that I stopped thinking of pregnancy as just a biological event. It’s a whole person life event. And the things we ask postpartum people to do need to respect that.”

Lane, a mother herself, has since made it her mission to understand not only how the pregnancy and childbirth experience affects maternal health but also how to use that information to help mothers re-prioritize exercise in ways that work for them. We sat down with Lane to talk about how her work as a committee member at the American Heart Association; in her new Kines lab, the Lifestyle, Exercise, and Arteries Lab; and through her conversations with media outlets, she’s trying to make exercise more accessible for mothers and society at large.

Q: How would you describe your research?

A: We’re studying changes in women’s heart and metabolic health around reproductive events. So we're thinking a lot about pregnancy (and dipping our toes into the water of menopause) as these are identifiable times in the lives of women where there is shock and change.

by

Having a baby changes you forever. Every mom knows this, right? But we're trying to understand what's happening to these women’s bodies and then how to get them on the right track to be healthy in this new phase of life, in ways that really work for them.

Q: You’ve served on the American Heart Association’s National Physical Activity Committee and worked on their scientific statements [public recommendations] around exercise. Why were you interested in that work?

A: The topics were very in line with what I was doing. Someone else in the group brought up this idea of life transitions and how to support physical activity for people going through those, and that spoke to me so much. We put so much burden on the individual to make exercise happen. But we need to consider how we can aid people in doing that.

And then we released another statement on resistance training. Before academia, I was a personal trainer and strength and conditioning coach. I look in the mirror and see a meathead. So it was lovely for me to marry heart health and weight training.

Q: I remember when you spoke to media outlets about that one. Why are those media appearances important to you?

A: My big problem with science is that it sometimes exists in its own little space that doesn't touch people in obvious ways. What I loved about being a personal trainer and strength coach was trying to help people be active and get stronger. The media is just an opportunity to reach more people and hopefully help them understand that they can exercise and then how to do it.

Q: This idea of making science more accessible seems to be a thread that runs through all the work you do.

A: Yeah, that’s a big gap, and it’s no longer OK with me. Our lab is working on implementing a resistance training intervention for postpartum people, and I’m very excited about this because resistance training is probably more doable than telling a new parent to go out and walk for 20 minutes. It’s something you can do in the corner of your home. If you don’t get through your full routine all at once because your baby is crying or you have to pick their sibling up from school, that’s OK.

Our other goal with the lab is to get more user-focused information. My mistake in the past has been telling people what they should do in a generic way, and it turns out people don’t always like that.

So, in the studies we’ll be doing, we’re going to ask focus groups of postpartum people what they want. Do they want to come into a gym? Could we let them use SoK’s Clinical Exercise Research Center? Do they need something they can do at home? Do they want to use bodyweight, resistance bands, milk jugs? We’ll design a program based on those responses, and we think that’ll lead to the best chance of success.

Q: It makes sense given your background that you have a different perspective on science. Why did you decide to make that transition to academia?

A: I was actually the assistant director for fitness and wellness at two major universities, including the University of Texas at San Antonio. They got into a bind and didn't have anyone to teach a kinesiology class one summer, and someone heard that I had a master's degree in exercise physiology. I taught the course, and the floodgates opened. I realized I missed exercise science so much. So I cold emailed a couple of professors at the University of Florida, where I got my master’s, and said, ‘How does one go about getting a PhD?’ And it’s been a crazy ride from there.

A: I never thought I would be at U-M because I’m from Columbus, Ohio. So my family is a little distressed. But during my career, I’ve looked at where the opportunity is and who I want to work with. And my U-M students are mind-bogglingly smart and creative. I think they’re going to grow my research because of their great ideas and the way they think about things. It feels like such a big deal to be here that I still pinch myself.

In this story, we have decided to use a variety of language, including “women,” “mothers,” and “postpartum people.” Federal grants that provide money for Lane’s type of research vary in their word choice, and we recognize that some folks identify strongly as mothers while others prefer to use different terms. We welcome this diversity of identities and believe in representing them accurately yet inclusively.

Sport management faculty member Mike Lorenc is helping undergrads find out through a new partnership with a local soccer club.

BY SARAH KUTA

Alejandro Echeverria (SM ‘23) has always loved soccer, whether he’s playing it himself or cheering for his favorite team, FC Barcelona.

So, when Echeverria heard about an opportunity to help out with AFC Ann Arbor during his senior year at the University of Michigan, he was immediately intrigued. The semi-pro soccer club is co-owned by Michal (Mike) Lorenc, who became a clinical assistant professor at the U-M School of Kinesiology in fall 2023.

Echeverria threw himself into volunteering, from creating videos for the club’s social media pages to landing new sponsors.

“It was such a valuable experience for me,” Echeverria says. "At the end of the day, actually going out and being proactive and gaining industry experience is the best way to learn."

Echeverria was one of close to 200 students who are putting sport management theory into practice, thanks to a new partnership between the university and both the men’s and women’s AFC Ann Arbor teams. As volunteers, students are coming up with new community outreach and marketing ideas, developing merchandising strategies, offering feedback on jersey design, organizing special themed games, and reviewing club finances. They’re writing fiveyear growth plans and helping the club re-launch its nonprofit arm, the AFC Ann Arbor Foundation. One student even served as the club’s mascot, Nutmeg the squirrel, at an event.

“We want to give students an in-depth look at the day-to-day operations of a smaller-scale sports entity,” Lorenc says. “The idea was to expose them to the actual, real-life business challenges, the community challenges, and then give them the opportunity to start solving those problems and gaining experience.”

Lorenc comes to the university after 20 years at Google, where he worked with ticketing, sports, music, and live events companies. Nearly a decade ago, he also co-founded AFC Ann Arbor, to bring more soccer into the community as well as help Division I and Division II college athletes improve their skills and move up into the professional ranks.

When Lorenc joined the SoK faculty last year, he saw AFC Ann Arbor as the perfect handson learning opportunity for students — especially first-years and sophomores, who are still learning the fundamentals of sport management.

Lorenc began mentioning the opportunity in his classes last fall; members from several student organizations, including the Michigan Sport Consulting Group, the Michigan Sport Business Conference, and the Michigan Sport Venture Group, were eager to get involved as well.

Lorenc began holding weekly meetings in the SoK Building, where students pitched ideas and brainstormed ways to help the club overcome its latest challenges. Throughout these discussions, Lorenc connected the dots between what was going on at the club and what students were learning in their classes.

“We discuss all aspects of the club’s operations so they have visibility into what it’s like to run a sports organization,” he says. “I’m trying to be as transparent as possible — they know our finances, they understand which players we’re trying to sign, they know the cost of traveling to different places. Providing that level of access can be very beneficial because it makes things much more tangible and real.”

Right now, students are volunteers. But, moving forward, Lorenc hopes to create an internship program that will, ideally, propel students to internships at other organizations and, later, to full-time jobs.

More broadly, he also hopes to open students’ eyes to soccer, one of the fastest growing sports in the United States. While many sport management students are focused on the “Big Four” — Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Hockey League, and the National Basketball Association — Lorenc wants them to expand their aspirations and think globally.

“If somebody is only thinking about working for the established leagues in the U.S., they don’t actually have the opportunity to innovate as much,” he says.

“If you can identify something in our industry or a new industry that will grow faster than others, this is the best opportunity to learn. Soccer and the growth in women’s and international sports offer that opportunity.”

When you’ve spent decades as a researcher and educator, the work doesn’t really stop once you retire, especially for these three beloved faculty emeriti. Even though they’re off the university’s payroll, they’ve continued to engage in research and publishing — amid golf games and gardening sessions, of course. We asked them to share a bit more of what they’ve taken with them from the U-M School of Kinesiology and what they feel they’ve left behind as their legacy.

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

Favorite memory as a professor: “Personal relationships with students assisting me in research. The most meaningful was with QingYun Zheng, a doctoral student from East China University. She figured out that I was born in the Year of the Dragon, and for my eighth such cycle in 2024, her 6-year-old son sent me a brass dragon statuette, and she gave me a red outfit (and socks!) to bring me luck.”

What you’ve left behind as your legacy: “Part of my legacy was creating the Katarina Borer Lectureship in Exercise Endocrinology and Metabolism in 2018. Physiologists have studied metabolism for years, but the role of hormones was considered incidental. With the lectureship, I wanted to facilitate discussions about the importance of hormones in metabolism that would continue even after I’d left.”

What you’re up to in retirement: “I continue to publish data that I collected as faculty, and I serve on editorial boards for three journals. As a biologist at heart, I am also planting common milkweed (to feed monarch butterflies!) and two fruit trees (I hand-pollinated a quince tree). Eventually, I hope to find time for some non-scientific writing, including chronicling my family’s history.”

Favorite memory as a professor: “When I was hired, the department was primarily a teacher education program. A few years later, new director Dee W. Edington was charged with transforming our vision and direction to be more research-oriented. There were about 50 departmental meetings that were fun, frustrating, and enlightening. We agreed to change fundamentally everything — including our name, from ‘Physical Education and Athletics’ to ‘Kinesiology.’ We were one of the first PE departments in the United States to do this and, essentially, usher in a whole new field.”

What you’ve left behind as your legacy: “I’m most proud of co-writing the textbook, Exercise Physiology: Nutrition, Energy and Human Performance, now in its ninth edition. Our book has been translated into five languages and is considered the leading textbook in its field worldwide.”

What you’re up to in retirement: “I continue to write my monthly column, ‘Health Yourself,’ for the U-M alumni newsletter Michigan Today and am currently compiling these columns into a book. I also consult for health and fitness companies and work on revising my three textbooks as needed. In my leisure time, I grow my own vegetables (my wife and I are plant-based eaters) and play golf, weather permitting.”

YEARS AS U-M FACULTY

Your favorite memories as a professor: “Working with graduate students, training professionals, and traveling domestically and internationally to present my research on motor development and pediatric disabilities. I always enjoyed having lunch with the staff, too; I learned so much by listening to them.”

YEARS AS U-M FACULTY

What you’ve left behind as your legacy: “I have trained many undergraduates who wanted to go into medicine, physical therapy, or occupational therapy. I discovered early on that they rarely had experience with pediatrics or disabilities. So I added a practicum where they worked with children and/or adults with disabilities for at least an hour and a half per week. The students often claimed this was one of their favorite Kinesiology experiences, and many became interested in pediatrics by the end. I was always amazed that taking this course had shifted their opinions about their future careers.”

What you’re up to in retirement: “I play a lot of tennis and golf. I continue to train researchers and professionals to use and adapt the test for gross motor development [now cited around the world] that I created in the ‘80s. I also volunteer one or two nights most weeks at an organization for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault.”

The week before the start of the 2023 fall semester, a small group of students was already bonding. It was team-building day for the Kinesiology LINKS (Leadership, Inclusion & Networking for Kinesiology Success) program, which provides social and cultural support to graduate students from communities or with identities that are typically underrepresented in kinesiology or at U-M. The students spent most of the time navigating the obstacles of a ropes course, often grabbing onto each other’s hands for balance. Many would later say it was a pivotal day — leading them to hold onto each other for much longer. “We were able to truly connect with each other and start building community,” one LINKS member said. Tahirah McIntosh and Elena Viñales, the program’s co-leaders, said this LINKS cohort was one of the most engaged they’ve seen. “We reworked the program postpandemic, so people understood it was about them having a small group where they could go to feel comfortable at this bigger university,” McIntosh says. Viñales says the “synergy” of the group was good from the start. “And then it just took off.”

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

WA

cancer diagnosis may have taken Kaylee America Rodriguez off the

softball field, but it hasn’t

struck her out.

BY SARAH CAHALAN

hen Kaylee America Rodriguez enrolled at the University of Michigan four years ago, she planned to spend her time studying and playing softball, as a sport management major and an infielder for the Wolverines.

By the end of her first year at U-M, though, her focus had shifted; her younger brother, Keanu, was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2021. She peppered her sophomore fall with calls and trips home to support Keanu, and he was declared cancer-free by November.

But less than a year later, the unthinkable happened when Rodriguez was diagnosed with an unrelated cancer: Ewing sarcoma, a rare bone cancer that had caused a massive tumor to envelop her left hip.

“Being an athlete, especially in a sport like softball, I always had the mentality of, you know, putting it all on my back,” she says. “But going through what I went through, being vulnerable in every way — they were there to pick me up.”

Rodriguez returned to U-M last fall, and she’s training daily in the hopes that she may play softball again before her eligibility expires in 2025.

Rodriguez’s diagnosis was life-changing. A few weeks into her junior year, she returned home to Miami to undergo several months of chemotherapy and a partial hip replacement. The treatment was successful at eliminating her cancer; in August, Rodriguez “rang the bell” to celebrate finishing chemo at the same facility where her brother had wrapped up treatment almost two years prior. But the experience took her out of softball indefinitely.

“Treatment ripped away my abilities,” Rodriguez says. “What I could do on the field, my ability to walk, my hair — just everything.”

Yet it also showed her the assets she still had, including the one she values most of all: her “village” of friends, family, and teammates.

I’m still learning my story as I go. I’d love to speak to thousands. That’s my goal: to just change the world as much as I can.

— Kaylee America Rodriguez

With the help of her sport management professors, though, she’s also started looking ahead to a life after cancer, after softball, and after college.

Her Kines classes have prompted her to consider pursuing program development, coaching, or marketing after graduation. But she’s also intrigued by motivational speaking. Rodriguez has a blog where she writes about her cancer journey, and her story has been picked up by enough media outlets that some mentors have suggested hiring a PR agent.

“I’m still learning my story as I go,” she says for now. But eventually, “I’d love to speak to thousands. That’s my goal: to just change the world as much as I can.”

While he was still in high school, Sarthak Subudhi organized Michigan’s first cricket tournament at that level. Now that he’s a Kinesiology student, he plans to keep the momentum rolling.

BY AIMEE LEVITT

Sarthak Subudhi was just five years old during the 2011 Cricket World Cup, but he remembers the final match of the tournament vividly. India and Sri Lanka were playing in Mumbai, so the game was broadcast early in the morning in the United States. Subudhi’s father, who grew up in India, was a fervent Team India fan and had invited friends over to watch.

“I remember the tension in the room,” says Subudhi, now in his first year at the U-M School of Kinesiology. “My parents and the other adults were circling the TV, and their eyes were glued to the screen. Fortunately, India happened to win. It was a thrilling and exciting moment. I still remember today the feeling of community I felt around the sport.”

That feeling stayed with Subudhi as he grew older and learned to play the game himself. When he was a junior in high school, it inspired him to start a cricket team at Washtenaw International High School in Ypsilanti.

With the aid of teacher/advisor Utkarsh Shah, who shared his passion for cricket, Subudhi assembled a roster of 30 players. The school has a large South Asian population, so most players were already familiar with the game, which is similar to baseball in that it has pitchers and batters, though the rules of fielding and base-running are different.

The harder part, says Subudhi, who served as captain, was molding them into a team.

(Subudhi also played: he was a fast-pace bowler, or pitcher, and a top order batsman, one of the first three batters.)

“Although there are individual stats, it’s a team game, and that’s more important,” he says. “Each player has to have an impact.”

Initially, the Washtenaw players scrimmaged amongst themselves, but when Subudhi learned of other high school cricket teams in metro Detroit, he reached out to their captains. In May 2023, four schools gathered at the Troy Community Center for the first Michigan High School Cricket Tournament.

“The teams were prepared,” Subudhi says. “It didn’t seem like amateurs playing.”

In fact, the event went so well that five teams convened in 2024 for a second tournament. (Subudhi’s team came in second.)

Although Subudhi is now in college, he plans to launch a campaign to make cricket an official high school sport in Michigan. The game is becoming increasingly popular in the U.S.; Major League Cricket made its debut in 2023 with six teams, and the U.S. and the West Indies cohosted the 2024 Cricket World Cup.

“If there were ever a time to expand cricket in Michigan,” Subudhi says, “it’s now.”

Athletic training students get a primer on how to understand and apply the latest research.

BY SARAH KUTA

In late November 2023, graduate athletic training students were in the U-M NeuroSport Clinic, practicing concussion evaluation. When they were done, they removed their virtual reality headsets — and resumed their class at the University of Michigan Center for Academic Innovation. They had been testing out a virtual module that could help health care practitioners better understand the nuances of concussion evaluation and diagnosis.

The experience is just one example of the constant evolution in sports medicine as new research emerges — and how U-M athletic training students get to learn to put these advancements into practice, guided by faculty who are prominent researchers in the field.

“We want our students to be the leaders and the best,” says Lindsey Lepley, an associate professor of athletic training and movement science and one of the faculty members who teaches the course. “And, to achieve that, they need to be implementing the newest insights into the clinic and becoming critical consumers of research.”

“Contemporary Issues in Sports Medicine,” which launched as a mandatory course in the Athletic Training Program in fall 2022, specifically focuses on new and emerging scientific evidence related to health care for an athletic population. Students hear about the latest developments in wearable tech, psychological wellness, heat illness, ACL rehab, neuroplasticity, training loads, biofeedback, and a wide array of other relevant subjects.

The course also covers practical topics, like what to do if an emergency occurs at a sporting event, which could range from a catastrophic injury on the field to an impending tornado.

“Most of them will go on to be practicing athletic trainers within six to 12 months, and they’ll be out in the workforce applying this information,” says Steven Broglio, a professor of athletic training and associate dean of graduate student affairs. “It prepares them before they launch.”

Students typically take the course during their second year, in the semester when they’re not involved in their immersive clinical experience. Many of the assignments involve reading research articles and engaging with scientists directly. Guest lectures — via Zoom or inperson — are often a key component of the class.

“We want to help demystify the people behind the papers,” Lepley says. “My hope is that students are not afraid to pick up a research article, develop their own opinions on it and reach out to the authors if they have follow-up questions.”

To complement the weekly research discussions, Broglio and Lepley add different elements each semester. Students may discuss how to handle a topic in the news, like Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin’s onfield cardiac arrest in January 2023 or Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa’s many concussions. Other times, they’re getting acquainted with new technology, like the VR headset to evaluate concussions, or making their own podcasts featuring experts in the field. During one semester, they even participated in a mock courtroom cross-examination while considering the legal aspects of sports medicine.

Above all else, the course embodies the program’s philosophy more broadly — that students should stay curious, long after they graduate.

“Every instructor within the program is trying to instill in the students that this is just the beginning of your knowledge journey, not the end,” Broglio says, “and this class is a part of that.”

In-house clinical psychologist Brett Smith meets students where they’re at to help them manage their stress.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

IF IT’S RAINING, WE CAN EMBRACE IT OR HIDE FROM IT. BUT WHAT WE DO DOESN’T CHANGE THE STATE OF THE WEATHER. — BRETT SMITH

by

Open the door of Brett Smith’s office in the U-M School of Kinesiology’s Student Affairs suite, and you’ll find all the trappings of a good therapist: two comfortable chairs, several lamps with soft light, a sound machine that protects the confidentiality of anyone talking inside.

But there are also glimpses of Smith’s identity as a person, beyond his role as SoK’s embedded clinical psychologist. (“If I’m not expecting myself to be authentic, I can’t expect the person across from me to be,” Smith says.)

Colorful soccer scarves are draped over a cabinet, hinting at Smith’s love for the sport and his past life as a collegiate soccer player. Blue fidget toys sit on a side table, ready to help him release the restlessness that his ADHD can bring on. Banksy knock-offs hang above his desk — the classic one of a girl letting go of a balloon and another of a man in a suit ducking under an umbrella while a girl delights in the rain.

For Smith, the art is a reminder of childhood and the elements of ourselves we often lose when we grow up. It’s his goal to help students become more themselves as they mature, including learning methods to manage stress that work for them individually.

“It’s figuring out how we can help you enjoy what you’re doing more,” he says. “What do you need to change to adapt to new environments? What can you step back from to allow more space for what you need?”

“Because if it’s raining,” he adds, “we can embrace it or hide from it. But what we do doesn’t change the state of the weather.”

Four days out of the week, Smith conducts sessions in this second-floor office at SoK. This is partially to make therapy more accessible to students; if they have a short window between classes, they can stop in for an appointment without disrupting their days. (Smith also offers virtual visits.)

But there’s more strategy behind the decision to base Smith in SoK instead of on the fourth floor of the Michigan Union, where U-M Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) is headquartered. He’s part of the half of CAPS staff who were intentionally embedded in a U-M school to “address the specific needs of each culture,” according to the CAPS website. Smith, who joined the Kines staff in fall 2023, seems like the ideal person to achieve this goal at SoK.

Having played soccer in college and then indoors professionally, he often looks at stress through a performance lens. Kinesiology students who are or have been athletes are used to pushing themselves to optimize their performance on the field or the court, and they could take that same mentality to set themselves up for success mentally, he says.

“However, that same background can lead these students to feel like they have to apply that same standard to other areas of their lives, especially if they no longer have organized sports as an outlet, and that self-expectation can then easily lead to stress and burnout,” Smith says. “Sometimes it can be detrimental, and other times, it can be that perfect thing to help them vault to where they want to be.”

Smith is trained and certified in several different modalities, and he says he doesn’t believe in just one approach. Sometimes the right strategy to help a student may actually involve setting them up with a provider outside of U-M, he says, especially if they need long-term support.

“There are students with so many diverse cultures and experiences here at U-M,” Smith says. “It’s my job to continue to expand my toolbox to help them.”

After all, Smith says the approach he personally needed during his doctoral studies was atypical. He has ADHD, and that manifested in difficulty keeping track of time and tasks.

“I would often try to match my study and learning approaches to mimic how others learned and realized it only created more stress for me,” Smith says. “I had to accept that I approach things very differently than most and although it wasn't what I perceived as ‘normal,’ it allowed me to explore what works for me without guilt or comparison.”

He now co-facilitates the weekly “Untapped Brilliance with ADHD” student group on campus during the fall and winter semesters to help students like himself learn more about their needs and come up with solutions to fulfill them within the higher education environment.

“What I realized in school was that stress itself is not a bad thing,” he says. “It’s asking how we can balance our responsibilities with our mental health. Maybe that means more physical exercise, maybe it’s therapy. It’s about changing the responsibility from a burden to opportunities you’ve earned.”

The Mobility Initiative pairs Kines undergrads with patients in the Medical Short-Stay Unit to keep them up and moving during their hospital stays.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

Movement science undergraduates Therese Campos and Meghan Tompkins were walking, like they did every Tuesday and Thursday between 3 and 7 p.m. Back and forth, back and forth, down the hallway of one of Michigan Medicine’s Medical Short-Stay Units (MSSU).

The patient they were escorting was very excited to be up and about.

“I haven’t been out of my bed yet,” she told them. “I want to walk.”

“Awesome,” they said. “That’s what we’re here for.”

Specifically, Campos and Tompkins were at Michigan Medicine as part of the Mobility Initiative. This partnership between the University of Michigan’s health care system and the U-M School of Kinesiology aims to provide patient experience for students interested in health care careers while supplying Michigan Medicine with additional personnel who could assist with an important element of care.

The patients in the MSSU aren’t often in the hospital for very long, two or three nights on average.

But even in that short time, they can become less conditioned, which can lengthen their stays and sometimes lead to other health concerns, like pressure sores or hospital-acquired infections.

“The initiative really started with a question,” says Chris Magnant, the former acute therapies director at Michigan Medicine (now retired), who came up with the idea for the program. “‘How do we prevent patients from losing strength and mobility during their hospital admission?’”

The answer: Twice a week during the winter semester, Campos, Tompkins, and two other kinesiology students, Kaleb June and John Han, headed over to the medical campus. They introduced themselves and asked patients in the MSSU to walk a short distance several times, accompanying them along the way to make sure they didn’t fall.

“It’s pretty surface-level in terms of what we did for them,” June says. “But I was still proud of what they were able to accomplish. It reaffirmed how much I want to be involved in health care in the future.”

The first thing the students had to do when they arrived at the hospital is figure out whom they could walk with.

The program used the Johns Hopkins Highest Level of Mobility Scale as a guide. The tool assigned numbers to patients from 1 to 8, depending on how much they could move. If a patient was at a 1, for instance, they could only lay in bed; if they were at a 3, they could sit on the edge of the bed. Patients deemed able to walk at least 10 steps were rated at a 6, and that’s the

minimum level of ability the students could work with.

The students kept track of the time, distance, and number of times the patients walked and documented the patients’ reaction to the movement.

Unless the patients said no, they didn’t want to walk.

Then the question became why. Is it because they were waiting for their pain medication to kick in? Is it because they needed mobility aids like a walker or a medical boot, which the students could assist with?

Or the most common reason: The patients were scared to walk. Once, there were eight patients on the unit, but only four said yes to walking because they were afraid.

“Sometimes it takes some convincing,” Campos says. “It’s going back and back and trying to help them understand that the nurses have cleared them to walk — and that they’ll feel better if they do.”

The persistence has been worth it.

Plenty were eager to walk from the outset. Tompkins recalled one man who was even speed walking and telling jokes.

“Getting out of your room and walking around like you're not stuck in a hospital room and talking to people who are just there to talk to you,” June says, “I think it definitely makes people feel better.”

The feedback about the program has been “wonderful,” says LaToya Freeman, director of quality safety and patient experience at Michigan Medicine, who manages the Mobility Initiative on the hospital side.

“We’ve seen the students be impactful even with patients that may have some cognitive delays or mental challenges,” Freeman says. “They’ve been able to be companions for those people who may not have family at the bedside. And patients that had reported pain and hadn’t been up walking, we’ve seen a decrease in their pain ratings.”

Getting out of your room and walking around like you're not stuck in a hospital room and talking to people who are just there to talk to you, I think it definitely makes people feel better.

— Kaleb June

The students tell plenty of stories about patients who were surprised at how long they could walk or were thrilled when they could walk farther than before. For instance, one patient who’d had spine surgery was nervous about walking. Then she walked a distance of 64 feet (a 7 on the Johns Hopkins scale) twice. She was so excited she called a loved one and recounted her triumphs.

“I was able to walk the circle twice!” she said.

“As someone who’s interested in physical therapy and occupational therapy, I want to see how rehabilitation can help patients improve,” Campos says. “So seeing how much better they feel when they’re walking is cool. But this experience has also reinforced that I like working with people, and that’s what I want to do in the future.”

This is a condensed version of our story about the Mobility Initiative. To read the full piece, including how the program came to be, scan this QR code.

The students in SoK's two winter-start programs get special access to experts and facilities that give them a glimpse of their many possible career options. Here's what they said about their immersive experiences.

“I came into the program completely unsure of what I wanted to do, but knew it likely wouldn’t be the traditional PT, pre-med, or AT route. This class gave me a deep dive into a multitude of career options that I didn’t even know existed, including performance nutrition. The speakers we met through this program really cemented that this was something I was interested in and wanted to pursue down the road, and gave me the opportunity for new connections.”

Emma Laredo, Movement & Applied Exercise Science program (MAES)

“I was most surprised about just how much goes into working for U-M Athletics. Everyone has a unique job and role that goes into successfully executing an optimal lifestyle for the athletes.”

Luke Ball, MAES

“The guest lecturer I looked up to the most was the strength and conditioning coach Lew Porchiazzo. His lecture was wonderful and introduced the basic knowledge of training and helped me to stay on the correct path of being a strength and conditioning coach in the future.”

Qufei Wen, MAES

Students in the MAES program take an exclusive course that focuses on careers in sport science and sport performance and gets them inside access to U-M Athletics facilities and staff.

“Certain treks opened my eyes to various jobs within the industry that I hadn’t previously considered, including data and statistics and event management. It was really cool to learn about all the avenues that are open to you.”

Ethan Gottlieb, Sport Management Immersion (SMI)

“I think a lot of people perceive kinesiology as a onedimensional field of study, or a straight shot to working as a physical therapist in a clinic. My experiences so far at Michigan have proven to me that there is so much more to this field, and there is truly a place for anybody who’s interested in the complexities of human physiology.”

Brady Onesti, MAES

“I have always been a big fan of all things sports since I can remember, but going into sport management at Michigan, I was thinking about how the major might prepare me to go work for a team in a limited number of roles. We’ve seen businesses from sports real estate to broadcasting companies, all the way to meeting with the GM of Toronto FC. I have been pleasantly surprised by how wide-ranging a career in the sports industry is and how many opportunities I have before me.”

Jonathan Karas, SMI

Scan this QR code to read more about Christopher Kelley and his work with U-M Adaptive Sports & Fitness.

In 2019, Christopher Kelley (MS ‘21) was debating where to attend graduate school. As a nationally ranked wheelchair tennis player, he hoped to find a university with an adaptive sports program. At the time, University of Michigan Adaptive Sports & Fitness (U-M ASF) had barely begun. But, assured that U-M ASF had grander goals, Kelley was interested in helping expand the program while completing his master’s. Five years later, Kelley is the program coordinator for U-M ASF. He’s hosted tournaments for four adaptive sports; traveled to 15 states with adaptive athletes; and fostered opportunities for adaptive athletes to compete at national and international levels. “The coolest thing, though,” Kelley says, “is that I work for a department that is changing the way para-sport is seen.”

— MARY CLARE FISCHER

When Sheryl Szady (PE ‘74, MA ‘75, PhD ‘87) discovered that an old bust of a U-M alum and early leader in women’s higher education had gone missing, the historian and amateur sleuth went on a quest to track down the artifact. Not only did she find it but she also gathered clues that helped piece together the whereabouts of Alice over the decades — and retraced the history of physical education at the university.

— HEATHER GUENTHER & MARY CLARE FISCHER

U-M president Marion LeRoy Burton writes that the new bust is moving from his personal library to its temporary home in the Barbour Gym, whose first-floor rooms house the offices of the Dean of Women and the Department of Physical Education for Women.

The Dean of Women suite relocates, and Alice ends up in the office of PE professor Ruth Harris, who does not know whom the bust depicts. (Only initials are inscribed on the back.)

The PE faculty move to the newly built Central Campus Recreation Building (CCRB), and Alice comes with them, eventually settling in a conference room.

PE separates from the School of Education, becoming its own division. School of Ed administrator Harry McLaughlin is brought over to manage the PE students, and Alice migrates to his CCRB office shortly after.

Having admired Alice’s poise and dignity, movement science professor Katarina Borer takes ownership of the statue when McLaughlin retires from what has become the Division of Kinesiology.

Borer retires and gifts the bust to new School of Kinesiology Dean Lori Ploutz-Snyder, who displays Alice in a conference room at Observatory Lodge (where Kines had moved some offices). There, Szady spots and correctly identifies Alice during a Kinesiology Alumni Society board meeting.

2023 Szady facilitates Alice’s move to the Michigan League, which, as the original student union for women, was always intended to be Alice’s final resting place. “It is great,” Szady said during the bust’s commemoration, “to see U-M history come alive.”

Brooke Harrison

As a personal trainer with Exos@Google, alum Brooke Harrison coordinates in-office fitness for the Silicon Valley set.

BY SARAH CAHALAN

Have you ever seen a job posting with “in-house fitness” as a benefit and wondered what, exactly, that entailed?

Brooke Harrison (AES ‘23) can tell you — at select Google offices around the Bay Area, she’s one of the trainers providing that service.

It wasn’t the path Harrison was expecting to take after graduating from the U-M School of Kinesiology. She’d thought she might pursue an MBA next since she’d minored in business. But applied exercise science lecturer Michael Stack (MVS ‘04), who’d become one of her mentors, suggested corporate wellness as an alternative. As the industry responsible for managing in-house health and fitness for large corporations, it represented a fusion of Harrison’s two interests.

An introduction to Schrimscher helped Harrison land an internship with Exos working for its biggest corporate client: Google. She spent a summer in California teaching workout classes and helping manage the gym at the tech giant’s Sunnyvale campus.

She loved the work, and a year later, she’s still with Exos@ Google — though these days as a certified personal trainer who helps employees with everything from establishing an exercise routine to improving their distance-running form.

The field also had plenty of open jobs. Though Harrison says corporate wellness is currently a “small, very niche” sector, the industry is growing quickly: It’s projected to double in market size by 2033, according to global market research firm Precedence Research.

“Corporate wellness came with all these opportunities,” Harrison says, “especially within the Michigan network.”

The Michigan connection is one reason Stack had suggested corporate wellness. He served on the Kinesiology Alumni Society Board with Scott Schrimscher (MVS ‘11), a longtime employee at one of the industry’s leading firms, Exos.

Without the Kines network, I would never have known about this role. There's this community of Michigan alums who just want to help each other out. That was huge for me.

— Brooke Harrison

Exos' mission — to make holistic health a part of the workplace experience — is one reason Harrison has stayed with the company. Seeing the benefits that Google employees get from their Exosrun office gyms is another.

“Every Googler can come in and use that space every day,” she says. “If they have questions, they can talk to the coaches who run the space.”

Harrison notes, though, that the benefits run both ways. Although Exos trainers aren’t Google employees, they do get to enjoy the perks of the company’s famously amenity-rich campuses, from free food to tech support. Following up a workout with networking at the office juice bar? Not a bad way to spend a Tuesday.

Recent grad Elana Goldenkoff hopes to use her movement science degrees to improve the public’s perception of government and science.

BY ALLA KATSNELSON

When it came time for the midterm elections in 2022, the University of Michigan showed up. Its student body — both undergraduate and graduate students — had the highest election turnout the campus had ever seen.

Elana Goldenkoff (MVS ’18, PhD ‘24) certainly doesn’t take credit for this achievement, but she is thrilled to know she played a part.

A couple years earlier, she had read that students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics tend to vote at lower rates than those in the social sciences and humanities. The disparity hadn’t sat right with her — and she was troubled when friends told her they didn’t plan to vote in 2022.

So Goldenkoff began working with a few campus groups to promote voter registration among STEM students, eventually launching Science at the Ballot Box, a campaign designed to encourage STEM

students to think about civic engagement, voting, and democracy, and about how science and policy relate.

“I was really proud of that,” she says.

Science policy has long held a draw for Goldenkoff, and it’s likely to become her career path in the future. As the world becomes increasingly complex, being able to straddle those worlds grows ever more important, she says.

Goldenkoff grew up in Fairfax, Va., in a family that prioritized education — her mom was an elementary school principal, and her grandmothers were a teacher and a librarian. She caught the neuroscience bug in high school; reading several books by Oliver Sacks about the brain got her own brain swirling with thoughts about “why we are the way we are and why we do the things we do.”

As a neuroscience undergraduate at U-M, she started out in a lab that studied flies but realized early on that she didn’t connect with cellular work in animal models.

Once she transferred to the School of Kinesiology her junior year, she focused on intraoperative neuromonitoring, a suite of techniques used to monitor the brain and spinal cord in human patients undergoing surgery, to ensure those organs aren’t damaged.

For graduate school, Goldenkoff says she “lucked out.”

Movement science assistant professor Michael Vesia had just arrived at U-M to launch the Brain Behavior Laboratory, and he was looking for a graduate student who could apply the techniques Goldenkoff had learned.

“I always knew science policy was an interest of mine, but I didn’t really know what the full range of options were,” she says. “So it was a good introduction to what this path might look like for me for the next couple years.”

Through the NSPN, Goldenkoff landed an internship working with the Office of Science and Technology at the Austrian Embassy in Washington, D.C. There, she worked on research about how immigrant and emigrant scientists around the world contribute to cultural diplomacy.

To boost her policy expertise further, she completed the Science, Technology, and Public Policy graduate certificate program through the U-M Ford School of Public Policy and became involved in a National

I’d love to help rehabilitate the trust between the public, scientists, and the government...to use science to promote public good and social change and to participate in creating an equitable and just world.

— ELANA GOLDENKOFF

She signed on for a PhD with Vesia to investigate the motor control networks in the brain using a brain activation method called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). Ultimately, that knowledge may be used to improve rehabilitation techniques for hand movement in people who have experienced a stroke or have other neurological impairments.

“I appreciated the societal implications,” Goldenkoff says. “I think that in general, science should be used for the public good — especially if we are getting public dollars to do it.”

Soon after, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. As Goldenkoff watched the world convulse with panic and uncertainty, she was struck by how the global public health emergency brought out people’s distrust in science — and on the flip side, how poorly scientists communicated crucial information about important issues such as masks and vaccines.

To explore the societal dimensions of all that she was observing, she joined an association called the National Science Policy Network (NSPN), becoming an active member of the group’s diplomacy and advocacy committees.

She quickly found herself engaging with and learning from early-career scientists across different disciplines who were pursuing careers in policy.

Science Foundation-funded project investigating how engineering students navigate the ethical responsibilities of their chosen profession, including how they view societally complex issues such as artificial intelligence.

Goldenkoff successfully defended her dissertation in March and recently began a stint in the New York State Science Policy Fellowship, which helps transition those with PhDs in science, technology, and engineering into public sector roles in the New York state government.

“I’d love to help rehabilitate the trust between the public, scientists, and the government,” she says, “and really, to use science to promote public good and social change and to participate in creating an equitable and just world.”

OK, so receiving one of the Kinesiology Alumni Society’s annual awards may not quite compare to winning an Oscar or a Grammy. But for Michigan Kinesiology alums, there’s not a higher honor from their alma mater than this recognition. This year’s five recipients have performed work in a wide range of categories, from physical therapy and athletic training to sport management and academia — and even the NFL.

Kelsey Nolan Shafer (MVS ‘14)

Physical therapist at Michigan Medicine

After being named an All-American in water polo at U-M, Shafer played the sport professionally in Australia for a season. She then received her doctor of physical therapy degree from the University of Saint Augustine for Health Sciences and eventually became a board-certified clinical specialist in sports physical therapy, one of about 3,500 in the United States. She currently works for MedSport Physical Therapy at Michigan Medicine, where she specializes in manual therapy, post-operative care, blood flow restriction training and return-to-sport testing.

Max Klepper (SM ‘14)

Director of partnership strategy and solutions at Ilitch Sports + Entertainment

Max Klepper began his career at the Detroit Lions as a community relations intern and later became the team’s partnership activation manager. After his tenure with the Lions, Klepper joined City Year Detroit as corporate & foundations partnership manager. In his current role at Ilitch Sports + Entertainment, Klepper oversees the development and execution of strategic partnerships that drive revenue, growth, and innovation for the Detroit Red Wings, Detroit Tigers, and the live entertainment company 313 Presents. In addition to his sport management degree from U-M Kinesiology, Klepper earned his MBA from Wayne State University’s Ilitch School of Business.

Jon Jansen (PE ‘98)

TV, radio, and podcast host

Jon Jansen played as an offensive tackle in the NFL for 11 years before retiring due to injuries. Afterward Jansen co-hosted studio shows, reported from the sidelines, served as a color analyst in the booth for the Big Ten Network, and made guest appearances on the NFL Network, The Jim Rome Show, and Golic and Wingo. He currently co-hosts U-M’s Michigan Football Tailgate pregame show; works with the U-M Athletic Department on various projects, including his top-rated podcast, “In the Trenches”; and co-hosts the morning radio show Costa & Jansen with Heather on 97.1 The Ticket.

Dawn P. Coe (MVS ‘97)

Associate professor of kinesiology, recreation & sport studies at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Dawn P. Coe has served as a kinesiology faculty member and pediatric exercise physiology researcher at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, since 2008. She specializes in assessing physical activity for youth, particularly in outdoor settings, as well as the impact of fitness on cognition and academic performance in young people. Coe has been involved with the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) as a fellow and as a member of ACSM’s Board of Trustees and its Task Force on Youth Fitness. She is also the immediate past president of the North American Society for Pediatric Exercise Medicine. In addition to her movement science degree from U-M Kinesiology, she earned a master’s in physical education & sport from Central Michigan University and a PhD in kinesiology from Michigan State University.

Head athletic trainer and physical therapist at Widener University, dean of athletic trainers in the Middle Atlantic Conference (honorary title)

At the end of September 2024, A.J. Duffy III will retire after 34 seasons as an athletic trainer and physical therapist at Widener University. Prior to arriving at Widener, Duffy worked at Temple University and his alma mater, U-M. In addition to his physical education degree from U-M, Duffy earned a master’s degree from the University of Arizona and a physical therapy certificate from Drexel University.

Over his 42 seasons in collegiate athletics, Duffy has served as the president of the Eastern Athletic Trainers’ Association and the Pennsylvania Athletic Trainers’ Society; a member of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA)’s Board of Directors; a member of the Board of Directors for the NATA Research & Education Foundation; and, as of this past June, the 16th president of NATA. (He will hold the latter post until June 2027.)

Duffy has received many awards for his years of service and excellence in the athletic training field, including the Pennsylvania Athletic Trainers’ Society’s Distinguished Merit Award and the NATA Most Distinguished Athletic Trainer award. He was inducted into the Pennsylvania Athletic Trainers’ Hall of Fame in 2015.

If you’re a Kines alum, tell us how you’d like to engage with our school and community in this brief survey. Scan the QR code or visit myumi.ch/JwEk7 to answer a few questions.

We decided to use a yellow robot as the personification of genAI arriving to U-M’s campus, inspired by U-M’s AI bot Maizey. SoK multimedia designer Stacy Getz imagined Maizey as a mid-sized, friendly yellow robot, but it's not yet possible to generate the same robot every time. You will see multiple iterations of Maizey, prompted in different AI platforms, throughout the feature.

The latest artificial intelligence tools have arrived at the U-M School of Kinesiology — and we're exploring how much the new bots on the block can (and can't) change our reality.

BY MARY CLARE FISCHER

In February, Zach Binkley received an email that confused him.

In his inbox was an article from the Michigan Daily, the student newspaper at the University of Michigan, about how U-M students were using ChatGPT. There was a section titled “Beware your future physical therapist” that stated 80 percent of students at the U-M School of Kinesiology were using the generative artificial intelligence (genAI) tool to complete assignments — the most of any school on campus.

Binkley, SoK’s director of innovative teaching and learning and a clinical assistant professor, was perplexed. But not because he assumed SoK students were cheating or letting a robot do their work for them.

“That poll should have said 100% of kinesiology students are using generative AI,” he exclaimed.

That’s because, over the past year, quite a few Kines faculty members have embraced genAI, permitting students to explore the technology and figure out the situations where it passes the grade, where it fails, and where it hovers around a C: adequate but plenty of room to improve.

“The general consensus is, it’s a helpful tool, but it is a tool that does not work by itself,” says assistant professor Jan Boehmer. “It still needs very well trained humans to judge what it is doing and what it isn’t doing.”

As much as it’s designed to mimic human conversation and behavior, artificial intelligence is still just that: artificial. So it’s probably not going to take your job (although it may change the skills needed for your position; more on page 45).

But, as our instructors and students have discovered, if you know how to use genAI, it could make your job easier — by saving you time (page 41), organizing your thoughts (page 43), generating ideas (page 43), and even improving the accessibility of your work (page 41). At their essence, these tools can help us create things we otherwise couldn’t create. As clinical assistant professor Mike Lorenc says, “It’s democratizing access for anyone to start creating.”

Yet that simple concept also surfaces questions around whether genAI’s creations are legal (page 44), biased, or samey, further reducing the amount of original and inspired work that goes out into the world.

As Lorenc says, too, “There’s a lot of junk out there, and we don’t need more.”

SoK faculty believe, though, that U-M provides the ideal environment to set precedents for this flawed yet powerful technology.

Instead of explaining the unique vocabulary of artificial intelligence ourselves, we thought we'd ask U-M GPT. Here are its responses, complete with annotations by U-M director of emerging technologies Don Lambert and writer Mary Clare Fischer

Lambert: “AI by itself is not a new technology; it's been around for about 50 years.”

“Our students are creative,” says teaching professor Kelli Donahue. “They are communicators. They are problem solvers. We’re doing our best to make sure they’re even better at that by the time they leave. So, with the very quick rise of AI, we decided to be as proactive and strategic as we could to help them understand how to use it effectively but also ethically.”

Read on to see how we're assessing the new bot on the block.

“There’s a lot of junk out there, and we don’t need more.”

— Mike Lorenc

New Chat

Prompt: What is artificial intelligence (AI)?

U-M GPT: The simulation of intelligence in machines that are programmed to think like humans and mimic their actions.

Prompt: What is generative AI ?

U-M GPT: A type of AI that can create new content, whether that be text, images, music, voice, or other forms of media that resemble human-generated content.

Prompt: What is a prompt in the context of genAI?

U-M GPT: The starting point from which the AI begins to create content. If the prompt is a question, the AI might provide an answer; if it’s a topic, the AI might compose related content; and if it’s the start of a story, the AI might continue the narrative.

Prompt: What is prompt engineering?

U-M GPT: The process of designing and refining the input given to an AI to produce the desired output. The way you phrase or structure a prompt can drastically affect the nature and quality of the response you get from the AI.

Prompt: What is ChatGPT?

U-M GPT: A version of genAI — developed by AI research organization OpenAI — that’s specifically fine-tuned for conversational responses. The responses are based on patterns it has learned during training rather than true comprehension, and users should be cautious about its factual accuracy and reliance on it for critical applications.

Prompt: What is DALL-E?

U-M GPT: DALL-E is an AI program developed by OpenAI that generates images from textual descriptions.

Prompt: What is U-M GPT?