PASSING: A Tool for Analyzing Service Quality

According to Social Role Valorization Criteria, 2025 Abridged Version of the (3rd rev. 2007 ed.)

PASSING Ratings Manual

Wolf Wolfensberger and Susan Thomas

PASSING: A Tool for Analyzing Service Quality

According to Social Role Valorization Criteria, 2025 Abridged Version of the (3rd rev. 2007 ed.)

PASSING Ratings Manual

Wolf Wolfensberger and Susan Thomas

A Tool for Analyzing Service Quality

According to Social Role Valorization Criteria, 2025 Abridged Version of the (3rd rev. 2007 ed.)

PASSING Ratings Manual

A Tool for Analyzing Service Quality According to Social Role Valorization Criteria, 2025

Abridged Version of the (3rd rev. 2007 ed.)

PASSING Ratings Manual

Wolf Wolfensberger & Susan Thomas

ISBN 978-1-989991-08-4

Copyright 2025, Valor Press

Published by: by Valor Press Valor Solutions

860 Rue Caron Street Rockland ON Canada K4K 1H1

Telephone: +1 (613) 249-8593 https://presse.valorsolutions.ca/en/

The correct reference for this work in the style of the American Psychological Association (APA) is:

Wolfensberger, W., & Thomas, S. (2025). PASSING:AToolforAnalyzingService QualityAccordingtoSocialRoleValorizationCriteria,2025AbridgedVersionof the(3rdrev.2007ed.)PASSINGRatingsManual. Rockland, ON: Valor Press. iii

Introduction to the 2025 Abridged Version of the (3rd rev. 2007 ed.) PASSING Ratings Manual

The teaching and implementation of Social Role Valorization (SRV) and the use of PASSING have, since 2010, expanded beyond North America, Australasia and Western Europe into Eastern Europe and the Indian subcontinent and, increasingly, there is interest in using PASSING’s powerful framework in societies with diferent cultural tradition. The ratings and supportive text provide excellent guidance in the universals on which SRV is based, and a number of people from non-western countries have participated in both workshops to teach PASSING, as well as in bonafide evaluations.

All previous editions of PASSING, including the most recent 3rd edition (Wolfensberger & Thomas, 2007), frequently use both positive and negative examples to clarify ratings and illustrate the application of assessment criteria. Although these examples are intended to be helpful, they are almost entirely based on western service forms and situations which users from other countries may be unfamiliar with. Needing to explain and/or translate western examples to make them relevant for other cultures and societies has proven to be dificult and an added complication when teaching and using PASSING in non-western countries.

Moreover, even in the English-speaking PASSING experience, there has always been some controversy about some of the examples, and these have sometimes proven to be distractions in training sessions and in the application of the ratings in assessment activities. This should not be surprising, as what is valued or devalued in societies evolves over time, and human service practices are continuously changing. Thus, examples have a shelf-life and need to be adapted, replaced, or, as we have done here, edited out. However, examples can be useful teaching tools and thus some examples that are determined to have global relevance remain (about 34,000 words or 17% of the text have been edited out of the preceding edition of the Manual). Ultimately, what matters is the universal that underlies or is embodied in each rating and its criteria, not examples that attempt to concretize the universal concept. Senior PASSING trainers and assessment team leaders will likely continue to use relevant examples accumulated from their service and assessment experiences and will illustrate SRV concepts by relating them to the real-time practices of human services that are being assessed.

Unfortunately, the senior author of PASSING, Professor Wolf Wolfensberger, died in 2011 and therefore could not be consulted about this change to the Manual. However, we have operated with the assumption that the ratings themselves are robust, and the nature of each rating is made adequately clear in the remaining sections of the Manual.

This Abridged version of the 3rd edition 2007 PASSING Ratings Manual is being published to guide both PASSING workshop participants and PASSING evaluators. Some may want to label this version as "experimental," acknowledging that the removal of examples may introduce its own dificulties, even if resolves certain others. Each of the 42 ratings include:

i. General Statement of the Issue

ii. SRV Requirement (Selected Generic Examples; Clearly Positive Service Examples; and Examples of Violations, all of which appeared in previous editions, are removed)

iii. Diferentiation from Other Ratings

iv. Suggested Guidelines for Collecting and Using Evidence

v. Criteria for Level Assignments (most examples removed)

This new version has maintained the pagination of the 3rd edition (2007) of PASSING, allowing assessment participants to use either the 3rd edition or this Abridged edition.

This Abridged Manual was developed under the leadership of Betsy Neuville, the Executive Director of Keystone Institute, to aid in teaching and application of PASSING in India and Bangladesh; with the support and assistance of Susan Thomas, the co-author of PASSING and coordinator of the Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership, and Change Agentry. Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, and Raymond Lemay, the Editor of Valor Press and a board member of the International SRV Association; and with the support of the International SRV Association (ISRVA) as well as the All-India SRV Alliance (AISRV). It is our intention that this Manual helps promulgate the understanding and implementation of Social Role Valorization in dierent cultures working to bring the good things of life to all people.

The writers of PASSING would like to acknowledge and thank the following people and organizations for their contributions to the design and development of the instrument.

The contributors to the development of PASS (see footnote 2 on p. 4), the forerunner of PASSING, especially Linda Glenn and Sandy Leppan. Many concepts now in PASSING were first developed in PASS;

The County of Dane (Madison, Wisconsin) Developmental Disabilities Services Board which commissioned the first (1980, experimental) edition of PASSING;

The Easter Seal Research Foundation, which provided financial support for two years for the evolution and preparation of the second (1983) edition of PASSING, and for related research and material development;

John O’Brien, who assisted in the conceptualization of the original framework of PASSING, the format of ratings, rating foci and boundaries, and who consulted with the Dane County Developmental Disabilities Services Board on the development of the first (experimental) edition of PASSING;

Joe Osburn, who helped write some of the earlier ratings in the first edition, led several assessment teams through the process of applying the instrument during practice (“de-bugging”) assessments for the first and second editions, and conducted the majority of the negotiations and arrangements for instrument development and try-outs of the first edition with the Dane County Developmental Disabilities Services Board;

Carolyn Bardwell Wheeler, Judith Kurlander, Raymond Lemay, Al Marks, Darcy Miller Elks, and Jack Yates, who were team participants in early practice assessments with the experimental edition of the instrument, and who thereby provided us with helpful suggestions for structuring the instrument and revising several sections;

The administration, staff, and recipients of Jowonio School, and of the Onondaga Association for Retarded Citizens’ Highland Avenue group home, both in Syracuse, NY, who graciously allowed us to conduct practice assessments of their services with the first edition of PASSING, at some inconvenience to themselves;

Tom Doody, Susanne Hartfiel, Joe Osburn, David Race, and Jack Yates for reading through the third edition to catch errors, and/or to comment on revisions.

This book, called the PASSING Ratings Manual, is one of several volumes (as explained below) that make up, or are related to, an instrument for assessing the quality of a human service, and for teaching adaptive service practices. The previous edition of PASSING1 was published in 1983, and the acronym PASSING initially stood for Program Analysis of Service Systems’ Implementation of Normalization Goals, but no longer does. PASSING is distinct from, but partially inspired by, the PASS (Program Analysis of Service Systems)2 method of evaluation.

Both PASS and PASSING are tools for the objective quantitative measurement of the quality of a wide range of human service programs, agencies, and even entire service systems. PASS measures service quality in terms of the service’s adherence to (a) the principle of normalization,3,4 (b) certain other service ideologies, and (c) certain administrative desiderata, all believed to contribute to service quality. On the other hand, PASSING measures service quality almost entirely by criteria of Social Role Valorization, or SRV.5 Each instrument is comprised of “ratings,” i.e., statements of issues related to service quality, and criteria that a service must meet in regard to that issue in order to be of high quality. PASS has fifty ratings, of which thirty-four are based on normalization. In PASSING, there are forty-two ratings, all of which incorporate SRV implications to the quality of a service.

PASS and PASSING are both designed to be applied to just about any type of human service, be it formal or informal (educational, vocational, residential, medical/health, counseling, advocacy, rehabilitation, transportation, correctional, etc.). Further, both are meant to be used to assess services to any type of person, but especially to those who are societally devalued or at risk thereof (people who are mentally retarded, elderly, physically impaired, mentally disordered, impaired in a sense organ, racial or ethnic minority members, poor, illiterate, disordered in conduct/behavior, criminals, severely/chronically ill or dying, etc.).

How PASS and PASSING resemble each other, and how they differ, is spelled out in the Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality , 6 and can also be appreciated by examining the PASS Handbook For further information on how the two instruments differ, contact the Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership & Change Agentry; Room 309 Huntington Hall, Syracuse University; Syracuse, New York 13244 USA; phone 315.443.5257.

1Wolfensberger, W, & Thomas, S. (1983). PASSING (Program Analysis of Service Systems’ Implementation of Normalization Goals): Normalization criteria and ratings manual (2nd ed.). Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation. (A first experimental edition came out in 1980.)

2Wolfensberger, W., & Glenn, L. (1975, reprinted 1978). PASS (Program Analysis of Service Systems: A method for the quantitative evaluation of human services). Handbook & Field Manual (3rd ed.). Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation. (Earlier editions appeared in 1969 and 1973.)

3Wolfensberger, W. (1972). The principle of normalization in human services. Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation.

4Wolfensberger, W. (1980). The definition of normalization: Update, problems, disagreements, and misunderstandings. In R. J. Flynn, & K. E. Nitsch (Eds.), Normalization, social integration, and community services (pp. 71115). Baltimore: University Park Press.

5Wolfensberger, W. (1998). A brief introduction to Social Role Valorization: A high -order concept for addressing the plight of societally devalued people, and for structuring human services (3rd rev. ed.). Syracuse, NY: Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership & Change Agentry (Syracuse University). (Earlier editions appeared in 1991 and 1992.)

6Wolfensberger, W. (1983). Guidelines for evaluators during a PASS, PASSING, or similar assessment of human service quality. Downsview (Toronto), Ontario: National Institute on Mental Retardation.

In PASSING, some terms or phrases are printed in bold letters, some in italics , and some in bold italics . Bold, or italics, are used to indicate titles such as in headings and sub-headings for ratings and rating clusters, or names of publications and bold print in the text is also used to indicate emphasis. A combination of bold and italic lettering is used to indicate great emphasis or importance, especially in instances where short words, such as “if,” “or,” etc., would be difficult to see in bold letters only. Also, although PASSING is applied outside the United States, US spellings and usage have been used throughout.

Within ratings, we tried not to break paragraphs over two pages, but instead to have a paragraph end on a page, and the next paragraph start on a new page. For this reason, there are sometimes one or a few inches of blank space at the bottom of a page, and the text continues on the page following.

PASSING has three major purposes: to assess the quality of any human service according to SRV criteria; to teach SRV; and to plan and analyze services according to SRV.

As noted, as an evaluation tool, PASSING is meant to be applicable to just about any type of human service. Some render a direct form of service, others an indirect one. Teaching someone, providing someone with a place to live, or with medical treatment, are examples of direct serving. Making a referral to another body so that it can deliver the needed medical care, or giving someone guidance on how to apply for a job, or for welfare, are examples of indirect service. In applying PASSING, it is very important that raters be very clear what type of service(s) is/are being provided, as will become evident in the various ratings of PASSING.

The PASSING Ratings Manual (hereafter called Manual for short) contains the material that a trained evaluator (i.e., a “rater”) would need in order to assess the quality of a service in relation to the criteria of SRV, and/or that a student of SRV would need in order to study SRV via the PASSING service evaluation approach even if the person did not want to assess a specific service, or to learn the PASSING discipline of service assessment. The Manual contains the complete forty-two ratings of PASSING, as well as additional narrative that may provide background to the ratings and to rating “clusters” (a cluster is a group of two or more ratings that have some common elements). The Manual is the book that raters and students of SRV must study thoroughly in order to understand:

a. how the implications of SRV are embodied in PASSING;

b. how PASSING structures SRV into “ratings” to be applied in the assessment of the quality of a service;

c. what each rating (or SRV implication) addresses; and

d. how each rating (or SRV implication) differs from the others.

The Manual is also the book that raters must take with them “into the field” (i.e., when they go out to a service to conduct a PASSING assessment), and which they will constantly need to refer to during all stages of an assessment, e.g., during data gathering, while making their rating level assignments, and during the deliberations (“conciliation”) of an evaluation team. In fact, raters will use the Manual in detail and repeatedly at each step as they apply PASSING, in order to:

a. frame questions to guide their study, observations, and inquiry of the service being assessed;

b. guide them in deciding on a level of service performance for each rating every time they do a service assessment;

c. clarify team members’ understanding of each rating while a rating team engages in conciliation in order to come to a consensus decision on all the rating levels;

d. help decide what information is to be reported back to an assessed service.

However, even thorough knowledge of the PASSING Manual is not sufficient to enable a person to master PASSING as a tool, and to participate in the conduct of a valid PASSING assessment. To that end, even otherwise very learned people must still (a) attend an introductory SRV training workshop, in which SRV is taught systematically; (b) attend an introductory PASSING training workshop, in which participants go through supervised practice assessments using the tool;

and (c) read, study, and learn other publications, especially the major current text on SRV (see footnote 5 on page 4). Therefore, a reader should not feel discouraged if, after reading this Manual, many questions remain. A complex work such as this cannot be understood just by being read, but has to be studied . However, by thoroughly studying this volume, a reader can gain a solid basic understanding of most of the implications of SRV for any service.

Further, this Manual can be very useful even to people who never attend SRV training, nor PASSING training, nor ever use PASSING to assess a service. The reason is that just by reading and studying PASSING, one can learn an awful lot not only about SRV, but also about adaptive principles and strategies for human services in general, and especially services to devalued people. For instance, PASSING sets forth a systematic framework for designing a service to optimize role-valorization via such aspects as its: location; internal and external facility appearances; service language practices; juxtapositions, groupings, and interactions of service recipients with each other, with servers, and members of the public; program functions; timing and rhythms of service activities; image-related issues of rights and autonomy; balance between overprotection and underprotection; comfort of the facility; individualization of service arrangements; fostering of recipients’ socio-sexual identity; presence and use of possessions; effective use of program time; etc. For many readers, PASSING will be much more useful for designing a service properly from the beginning than evaluating its quality later on when a lot of things will no longer be readily changeable.

SRV can also be used to structure elements on the highest societal level, as well as on the level of informal personal relationships in the family, among friends and casual contacts, and in a person’s own life situations. People who use PASSING for purposes of service design and analysis can of course ignore the evaluation-specific parts of the book, namely the sections in each rating entitled “Suggested Guidelines for Collecting and Using Evidence” and “Criteria and Examples for Level Assignments.”

However, when used as an evaluation instrument, PASSING is meant to be applied only to human services, be they formal or informal ones. It is therefore a misunderstanding to say that PASSING somehow “fails” as an instrument when it is used for purposes other than those for which it was primarily designed, or even worse, that SRV fails as a theory. For instance, while PASSING is meant to be a tool for analyzing services, it is not sufficient as a tool for structuring a party’s life outside of services. For such a purpose it can be very useful, but it was not specifically designed for such applications. Thus, a distinction must be made first between the application of SRV versus the application of PASSING; and secondly between applications of PASSING for the purposes for which it was designed, and other kinds of applications.

This volume of PASSING contains the following (see Table of Contents for a quick overview): text;

a. a glossary of important and commonly-encountered terms and phrases in the PASSING

b. an overview of the issues of social image enhancement and personal competency enhancement, which are the two primary overall goals of SRV;

c. all forty-two ratings of PASSING, each of which embodies one or a few distinct SRV implications. Each rating contains the following:

c1. an explanation of the SRV rationale(s) for the rating, and of the issues at stake therein;

c2. a chart containing a very brief statement of the SRV issue in the rating;

c3. an explanation of the differences between the rating at hand, and any other ratings with which the rating might be confused;

c4. a chart containing a list of sources of evidence for making a judgment on the rating, a list of questions that might be asked in order to obtain information useful for judging the service’s performance on the rating, and brief summaries of some important and potentially difficult clarifications of the rating issue;

c5. criteria for five levels of quality and performance, from very low to very high. In an actual assessment, a rater would have to decide on which one of these levels the service being assessed falls.

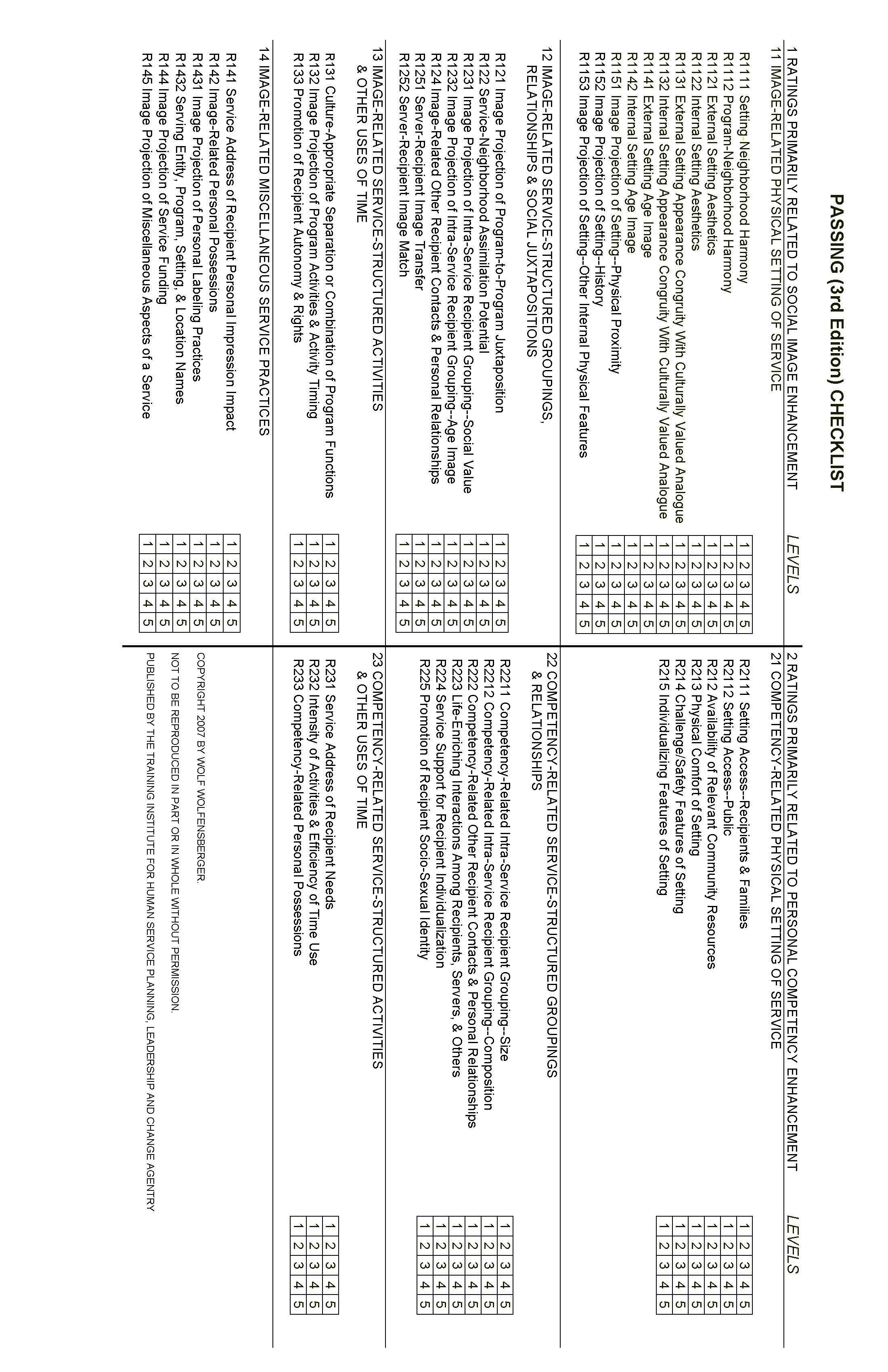

The forty-two ratings are allocated into two major categories: social image issues (twenty-seven ratings) and personal competency issues (fifteen ratings). Service practices that have more impact on recipients’ social image than on their competencies fall into the first category; service practices that have more of an impact on recipients’ personal competencies than on their social image are in the second category. Within both categories, ratings are subdivided as to whether they apply to: (a) the physical setting in which the service is located; (b) the ways in which the service groups its recipients and otherwise structures and supports relationships between them and other people; (c) the activities and programs that the service provides or arranges, and other ways in which it uses or structures its recipients’ time; and (d) (applicable only to the image category) miscellaneous other imagery associated with the service, and not covered by any of the other ratings. Thus, there are ratings that have to do with how the physical setting of a service affects the social image of recipients; there are ratings that look at how the physical setting of a service affects recipients’ competencies; there are ratings that look at how the service-structured groupings and relationships affect the image of recipients; there is another category which has to do with how the service-structured groupings and relationships affect recipients’ competencies; yet another group of ratings assesses the image impact of miscellaneous other service practices; and so on. Altogether, there are seven major cells of ratings, and a rating is placed in whichever of the seven categories it has the greatest relevance to, granted that some ratings have relevance to more than one category. The chart which follows illustrates this.

1 PROGRAM ELEMENTS RELATED PRIMARILY TO RECIPIENT SOCIAL IMAGE ENHANCEMENT

2 PROGRAM ELEMENTS RELATED PRIMARILY TO RECIPIENT COMPETENCY ENHANCEMENT

01 PHYSICAL SETTING OF SERVICE

02 SERVICE-STRUCTURED GROUPINGS, RELATIONSHIPS & SOCIAL JUXTAPOSITIONS

03 SERVICE-STRUCTURED ACTIVITIES & OTHER USES OF TIME

04 MISCELLANEOUS OTHER SERVICE PRACTICES

11 ratings, coded 11

7 ratings, coded 12

6 ratings, coded 21

6 ratings, coded 22

3 ratings, coded 13

6 ratings, coded 14

3 ratings, coded 23

no ratings not applicable

Even within the seven categories, the same service feature may be rated by more than one rating. For example, there are two ratings in the category coded 11 which both measure the beauty of a service setting, but one measures the beauty of the setting exterior, and the other that of its interior. Two or more ratings that separately measure different aspects of a service feature are called rating “clusters,” and such clusters may have anywhere from two to three ratings, or may be comprised themselves of two or more smaller clusters. For example, the rating cluster “11 Image-Related Physical Setting of Service” is comprised of five rating clusters, each of which in turn contains two or three ratings.

Every rating and rating cluster is preceded by a sequence of code numerals in front of its name. The first number in the sequence indicates whether a rating or rating cluster falls into the image or competency domain. All those ratings and rating clusters in the category of image enhancement are preceded by the code number 1, and those in the category of competency enhancement by the code number 2. Each subcategory is also numbered (see the chart above): physical setting of service is 01; service-structured groupings and relationships among people is 02; service-structured activities and other uses of time is 03; miscellaneous other service practices is 04. Thus, the second digit in the series of numerals that precedes a rating or rating cluster name indicates the sub-category into which it falls. For example, in the rating cluster “11 Image-Related Physical Setting of Service,” the first number 1 indicates that this cluster falls in the category of image enhancement, and the second number 1 indicates that it falls into the sub-category of physical setting of a service. Thus, all the ratings within that cluster would also have as their first two numerals “11.”

A rating is indicated by the capital letter “R” in front of the sequence of numbers at the start of its name, e.g., “R1122 Internal Setting Aesthetics.” This R distinguishes ratings from rating clusters.

Each PASSING rating has five “levels” of service quality, and each level of each rating is accorded a certain number of points; this number is called its weight or score. For example, the rating R1111 SettingNeighborhood Harmony has a weight of 16, meaning that a service could conceivably attain 16 points if it fully met the criteria of that rating. The sum of the weights of all the ratings in PASSING is 1000. However, as is explained in further detail in the aforementioned Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality, the weights for each rating are not shown in the Manual. This was done in order to avoid biasing a rater’s judgment of the performance of a service by knowing how many points the service could gain or lose on a particular rating. Instead, the rating weights are listed on a scoring form, called the Scoresheet/Overall Service Performance Form During the evaluation process, raters record their judgments on a Checklist that does not show the rating weights, and only after the completion of the evaluation team’s conciliation are the team’s final judgments transferred from the Checklist to a Scoresheet. A sample each of the PASSING Checklist and Scoresheet can be found in the back of the Guidelines , though in the 1983 edition of the Guidelines , these differ slightly in their language from this 2007 edition of the PASSING Manual. A sample Checklist can also be found at the back of this Ratings Manual, and both forms, being consumable, must be purchased separately from the publisher, since each rater will need at least one of each for every assessment.

Note that the wording of the text for all ratings and rating clusters ( starting with the text for “ 1 Ratings Primarily Related to Social Image Enhancement,” and ending with the last rating R 233 ) assumes that social role - valorization of service recipients is the desired outcome of a service. However, the larger SRV literature points out that SRV itself consists of a hierarchy of “if this, then that” propositions.7 The theory itself does not use a language that one should or should not do this or that, but that if one does or does not do this or that, then such-and-such an outcome can be expected to occur, and should not be surprising. PASSING does use “should” and “should not” language because it is based on the premise that at least overall, a service should be role-valorizing for its recipients, even if it cannot optimize all service quality dimensions.

The forty-two ratings in PASSING are not totally self-contained, in that the introduction to a given section or cluster of ratings contains material that is relevant to all the ratings within that section or cluster. Raters need to read, and become thoroughly familiar with, the introductory materials that precede a given rating or rating cluster in order to be able to master the rating itself, and especially when using only part of PASSING. For example, if raters are only applying some of the image-related physical setting ratings, they must know the introductory narratives to those ratings.

7Wolfensberger, W. (1995). An “if this, then that” formulation of decisions related to Social Role Valorization as a better way of interpreting it to people Mental Retardation, 33(3), 163-169.

Text that applies to more than one rating or rating cluster is inserted where it first comes up. For instance, some text applies to both some image-related and some competency-related ratings; therefore, it shows up where those image-related ratings are introduced, and its earlier appearance is crossreferenced where those competency-related ratings are introduced later on.

The conduct of a PASSING assessment follows a certain pattern. The instrument is applied by a team of no fewer than three people, called “raters.” Each team is under the direction and supervision of a person who is highly trained and skilled in PASSING, called a “team leader,” and each team does the following:

a. extensively review documentary materials (if available) regarding the program, including policy documents, statements of mission, recipient records, individual program plans, activity schedules, log books, position papers, job descriptions, regulations, publicity materials, etc.;

b. tour (usually by car and on foot) the neighborhood surrounding the service;

c. tour both the exterior and interior of the service setting itself;

d. conduct a lengthy, in-depth interview with service leaders, such as administrators and executives;

e. conduct interviews with servers, i.e., direct service providers, be they paid or unpaid;

f. observe the program/service in operation;

g. talk with the recipients, and possibly with recipients’ family members, advocates, and neighbors in the service neighborhood.

After the team has done the above, each rater individually assesses the program on each of the ratings in the instrument. This is done by deciding which level of performance on a rating the service merits. As mentioned, each PASSING rating has 5 levels, which represent different degrees of adherence of service practice to the issue at stake in the rating. The lower levels represent poor performance and the higher levels good performance. Each rating carries a certain weight (i.e., score), and so does each level of each rating. Once a rater has privately assigned a level for each rating to the service being assessed, the team meets at length in order to come to a consensus judgment as to the service’s performance on each rating. This process is called “conciliation.” At the end of it, the team (usually via a designated team member) reports back to the assessed service on its performance, usually in writing, often also orally. Rules for conciliation are given in the companion monograph for conducting an assessment mentioned before, namely the Guidelines (see footnote 6 on p. 4). The Guidelines also contain many instructions for assigning the different rating levels, but in addition, some more current, and some additional, guidelines for applying the PASSING ratings specifically are given in the section of this Manual entitled “The Rationales for the 5 Rating Levels, and Guidelines for Assigning Levels to Ratings” on pp. 12-15.

In all previous versions of PASSING, examples were used throughout, including in the five different levels for each rating. Examples are very useful for concretizing the abstract principles of each rating. However, as noted in "Introduction to the PASSING Ratings Manual: International Abridged Version," almost all the examples were intentionally excised from this version.

Once a rater has mastered the introductory and explanatory rationale narratives for a rating or rating cluster, he or she can take some or all of them out of the Manual, for easier use of the Manual while doing interviews and observations in the field. Some users hole-punch the Manual so as to put some or all of the contents into three-ring binders. In order to enable some such arrangement of sheets for different purposes, the Manual has been set up somewhat modularly, with each part of a rating starting on a separate page. This arrangement also makes it possible for a rater who plans to evaluate a service only on selected dimensions of SRV (i.e., using only some ratings) to leave the rest of the ratings out of the binder. A rater can thereby gain more rapid access to the pages that contain instructions for specific ratings, as well as lighten the material that must be taken into a service setting that is being assessed.

Raters will use the PASSING Manual over and over again. Consequently, there is no need to rigidly memorize any part of it. A rater will always have at least certain introductory parts, plus rating-specific parts, of the Manual with him or her all during an evaluation.

Of utmost importance in applying PASSING is to use it in certain standardized and consistent ways, as spelled out in the aforementioned Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality (see footnote 6 on p. 4). Following these prescribed procedures makes the results of different evaluations more comparable, and enables meaningful research to be conducted on the results. If the rules for assigning levels to a rating, spelled out in the Guidelines , are not followed, then the results will not be valid, and also not comparable to the results from other evaluations. Because the administration of PASSING to a service is very complex, evaluators need to have thoroughly studied the parts of the Guidelines that are relevant to PASSING, and to have the Guidelines book at hand throughout the evaluation, so as to be able to look up procedural points as needed. Also, raters need to distinguish those parts of the Guidelines intended for practicum evaluations (i.e., teaching and learning) from those that apply to “real” evaluations.

The 1983 Guidelines book also explains, on pp. 62-63, why PASSING generally rates service features without regard to the reasons why such features are present, or what the motives behind them are. All that matters is to what degree they contribute to the role-valorization or devalorization of service recipients.

When the 1983 edition of PASSING was published, the authors had hoped that other monographs on PASSING would also be developed, as had happened in part for PASS previously. However, so far aside from several published research studies only some informal unpublished user manuals have appeared, e.g., for assessment team leaders. Although unpublished, and circulated informally in the PASSING teaching culture, these can be very useful to members of PASSING evaluation teams. For information on obtaining any of these, contact the Training Institute, Room 309 Huntington Hall, Syracuse University; Syracuse, New York 13244 USA; phone 315/443-5257. Also useful to evaluators are certain passages in the PASS Handbook (3rd 1975 edition), such as the discussion of quantitative measurements of service quality (pp. 25-28, 30-31), and of the relevance or irrelevance of apparent recipient satisfaction with a service (pp. 3132).

In addition to the PASSING Ratings Manual, and the Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality , there are also a number of forms that are needed in order to conduct a PASSING assessment. These forms fall into three categories.

a. Those needed by each member of a rating team during each assessment. These are the Checklist and the Scoresheet/Overall Service Performance Form.

b. Those which would be very useful for a rater, but are not essential. So far, this includes only the Individual Rating Evidence Organization Sheet, of which a rater may want to use one for each rating during an assessment.

c. Those which only certain team members in specific roles (e.g., the team leader) need to have. These are the Findings and Comments for Specific PASSING Ratings form (of which one may be needed for each rating) and the Research Data Form (of which one is needed per assessment).

Actually, any team member might want to have copies even of those forms that he or she does not necessarily need, just to keep a complete record of the assessment. Also, the team leader will need several copies of the Checklist and Scoresheet/Overall Service Performance Form for each assessment.

As already noted, the forms are copyrighted, and therefore any forms that a team member needs or wants for an assessment should be purchased from the publisher, not copied from the samples in the Guidelines monograph.

Conclusion

Because PASSING is so big and complex, and because many distinctions must be made among the issues covered by different ratings, we have deliberately been a bit repetitive in explaining in different parts of the book what some of the distinctions are among ratings, and what are some of the more important rating points and principles. For instance, a point or distinction made early in the book may be mentioned later several more times. Also, the “Differentiation From Other Ratings” section within each rating has often been expanded from the earlier (2nd) edition. This also helps if only some sections of PASSING are used.

As noted, PASSING can also be read just to learn more about SRV, rather than to evaluate services. However, in that case, readers should be aware that there is a steady flow of SRV publications, and that some of these can also be read profitably to learn SRV better. As such publications appear, the list of the most recommendable items changes.

For information about upcoming SRV and PASSING training events, any active SRV or PASSING trainer can be contacted, as can the Training Coordinator at the above Training Institute.

As noted earlier, each rating in PASSING has five levels; for each rating, a service is assigned a level that reflects its performance on the issue assessed by that rating. The aforementioned 1983 Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality (see footnote 6 p. 4) contains many instructions for assigning levels during an assessment. Some are still valid, but this section contains some important new instructions, as well as some revised ones that supersede certain instructions applicable to PASSING in that companion monograph.

1. In all ratings, any vulnerabilities or risks of the recipients must be taken into account. Some practices inflict little or no harm unless recipients have a certain vulnerability. In other words, a service feature must not be considered in isolation (e.g., the service is located in a building that looks on the outside like a bar); what matters is the interaction between the feature and the vulnerability of the recipients (the recipients of the service in the setting that looks like a bar from the outside are valued adults, or are former and current drug addicts in a rehabilitation program, or are pre-school-aged children receiving day care there, etc.).

Devalued people are broadly vulnerable to further devaluation, as for instance through negative imagery, but different devalued classes are vastly more vulnerable to certain specific negative imagery than other such classes. For instance, death-imaging practices are particularly harmful to sick and elderly people because they are vulnerable to being seen as dead, dying, or better off dead. In the competency domain, confusing lay-outs of premises are bad for demented people who already are apt to be confused; etc. This issue of “heightened vulnerability” is elaborated on pp. 82-83 and 124-127 in Wolfensberger, W. (1998), A Brief Introduction to Social Role Valorization: A High-Order Concept For Addressing the Plight of Societally Devalued People, and For Structuring Human Services (see footnote 5 on p. 4), and in many narratives for specific ratings and rating clusters.

However, it must not be assumed that only devalued people have certain vulnerabilities. For instance, teenagers today are vulnerable to being suspected of all sorts of degeneracies even if they come from the most valued population sectors.

2. As noted in a previous section, some service quality issues assessed by a single rating have both image and competency implications, but were not split into two ratings, one in the image enhancement and the other in the competency enhancement domains. Where that is the case, the rating was assigned to only one of these categories, depending on whether the image or the competency factors were likely to be dominant. In applying such ratings, raters should consider both the image and competency impact of the service’s practices, despite the fact that the rating is carried in only one of these categories. For example, although the rating R231 Service Address of Recipient Needs has been placed into the competency enhancement category, it could happen that a major need of recipients is for enhancement of their social image, or of a particular image (e.g., as adults, as workers), and in that case, image issues would have to be taken into account.

3. Raters must only deal with whether service practices do or do not conform to the principles laid out by SRV theory in the descriptions of the specific ratings. If practices do so conform, they can be assumed to have positive role-valorizing effects, at least on a probabilistic basis i.e., for most recipients most of the time and the wording of the rating levels reflects this.

Raters do not have to have proof, or produce such proof themselves, that the dynamics at issue in a rating actually have positive or negative impact on the recipients, though if such evidence actually exists, it can be taken into account. In other words, raters are not allowed to deny credit for role-valorizing practices because they themselves have not seen the positive impact/outcome, nor can raters give credit for something positive apparently having happened to recipients that cannot reasonably be attributed to the service practice or feature at issue. For instance, if recipients attend very well to their personal appearance but are in no way influenced to do so by the service, then the service cannot be credited for it on R141 Service Address of Recipient Personal Impression Impact.

4. The purview that a service has (see p. 36 in “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms”) has a bearing on what the service can be credited or penalized for. There are three rules.

a. A service cannot be penalized for not doing something that is not within its purview.

b. A service is penalized if it does something that is not within its purview that is detrimental to recipients.

c. A service is credited if it does something beneficial for its recipients that is not within its purview. However, because exceeding purview almost always incurs some image cost, the service will probably be penalized for this on some image-related rating.

In trying to determine whether, and to what degree, an issue assessed by a rating falls within the purview of the service being assessed, it can also be very helpful to consider the service’s culturally valued analogues (see pp. 30-31 in “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms”). Whatever is the purview of a culturally valued analogue for a service to devalued people can be presumed to be the minimal purview of that service.

5. As far as we can tell, the issues in all image ratings are always under service purview except possibly in the case of certain services and certain service recipients on the four ratings of: R124 ImageRelated Other Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships; R133 Promotion of Recipient Autonomy & Rights; R141 Service Address of Recipient Personal Impression Impact; and R142 Image-Related Personal Possessions. For instance, an office that screens people applying for eligibility for welfare may have little or no purview to address issues covered by R124 and R141.

For the competency ratings, services always seem to have purview except possibly , as far as we can tell, for certain services and certain service recipients on the four ratings of: R222 Competency-Related Other Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships; R225 Promotion of Recipient Socio-Sexual Identity; R233 Competency-Related Personal Possessions; and in some instances R231 Service Address of Recipient Needs, as is explained in that particular rating.

Whenever raters encounter an instance where the issue assessed by a rating falls outside the purview of the service being assessed, then that rating should not be applied, and instead, the service’s score will be “pro-rated” once all ratings have been conciliated, as explained on pp. 82-84 of the 1983 Guidelines monograph (see footnote 6 on p. 4).

6. In a few of the image-related physical setting ratings, a Level 3 has to be assigned if a service setting is in “isolated dislocation,” and has no neighborhood, so to speak (see p. 34 in “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms”).

Specific Rating Level Principles

Levels should be assigned according to the following criteria, while keeping in mind all the above six points.

Level 1. The practices covered by the rating at issue, and that are within the purview of the service being assessed, are severely damaging to the image or competencies, and thereby the social roles, of all or most recipients, even if some practices do some good. The kinds and degrees of vulnerability of the recipients have to be taken into account, in that the same practice can have a much more deleterious impact on recipients with certain vulnerabilities than on recipients with other, lesser, or no vulnerabilities.

Level 2. The practices covered by the rating at issue, and that are within the purview of the service being assessed, can be assumed to do one of two things:

a. they inflict significant damage or impairment overall to the image or competency, and thereby the social roles, of all or most recipients, but less so than in Level 1, even if some of the practices may be somewhat positive (note the difference between severe damage in Level 1 and significant damage here); or

b. they inflict severe damage or impairment (as in Level 1) to the image or competency, and therefore the roles, of a significant minority of recipients, even if higher level conditions prevail for the other recipients. Such discrepancies in impact are often due to inappropriate groupings, showing how poor grouping can set constraints on other ratings.

Both Level 1 and Level 2 require a preponderance of negative conditions in the service being assessed, in regard to the issue covered by the rating.

Level 3 The effect of the service practices at issue on recipients’ image or competency, and therefore their roles, is neither as damaging as in Level 2, nor as beneficial as in Level 4. Level 3 is meant to capture a state where there is either a balance of slightly positive and slightly (but not very) negative features or practices; or where the effect of service practices on recipients’ image or competencies is, so to speak, neutral.

A Level 3 determination is often the most difficult to make. One of the following two scenarios must apply:

a. a service has some positive features and some negative features that in their totality of likely impact on image or competency, and therefore roles, seem to balance each other out. In other words, something enhancing is being done, and something negative is also being done, though none of the negative conditions may be as low as Level 1 for any recipients whatever; or

b. for other reasons, the service practices in regard to the rating issue neither significantly impair nor significantly enhance recipients’ image or competencies, and thereby their roles. A likely scenario here could be that recipients are not at significant image or competency risk, and what the service does neither significantly harms their image or competency, nor does it significantly enhance their image or competency. This might happen, for instance, if a service embraces a new craze that does not really do any good but neither does it do any harm, or at least not much of either.

Where image ratings are concerned, Level 3b is a fairly common scenario in services for ordinary citizens. So many services that such people receive neither add to their already positive image, nor detract from it.

In regard to Level 3a, it cannot be merely assumed that any program weakness can be offset or balanced out by a program strength. There are instances where even one single significant shortcoming may defeat or diminish any number of positive program features on the same rating issue. To further clarify: it is not the number of positive and negative features that must balance out (e.g., two good practices and two bad ones), but the totality of their likely impacts on service recipients, taking into account both the identities and image and/or competency risks of recipients, as well as the above proviso in Level 3a about no conditions being as low as Level 1 for any recipients. Conceivably, there could be instances where a single shortcoming could defeat, or seriously diminish, the impact of any number of positive program features on the same rating issue, perhaps even to the extent that a Level 1 must be assigned despite the presence of certain positive practices.

Level 4. This level can only be assigned under one of the following two conditions:

a. service conditions are mostly or nearly of Level 5 quality, but there are either some minor shortfalls for all recipients, or some shortfalls that affect a minority of recipients, but in either case none of these shortfalls can be lower than Level 3 for any recipients; or

b. recipients experience optimal conditions, as in Level 5, but relevant direct service personnel and service leaders lack consciousness of the importance of the issue, and thus a significant safeguard against future deterioration of service quality is lacking.

For a Level 4, there must be a preponderance or dominance of positive conditions in the service being assessed, in regard to the issue covered by the rating. Any negative conditions that do exist cannot be severely or significantly negative, as noted in Level 4a.

There are a very few ratings where an absence of any negative conditions whatever is required for a Level 4 or higher.

Level 5. This level is what has been called “the achievable ideal.” On this level, it is almost impossible to conceptualize further improvements except perhaps trivial and/or infinitesimally small ones; significant suboptimality is not allowed for even a minority of the recipients. In addition , consciousness of the importance of the rating issue must prevail among the service leadership and relevant direct service personnel, in order to safeguard against future loss of service quality.

A Level 5 is much more difficult to attain on some ratings than on others. For instance, it is easier to attain a Level 5 on R1431 Image Projection of Personal Labeling Practices, or R1432 Serving Entity, Program, Setting, & Location Names, than on R232 Intensity of Activities & Efficiency of Time Use.

The specific rating level principles laid out here should govern raters’ assignment of levels to the different ratings.

In applying the rating levels, one practice that PASSING team leaders and other users have found helpful is to first collect and review all the evidence relevant to the rating at issue, and then to characterize it overall, e.g., “very harmful to the image (or competencies) and therefore the roles of all recipients,” “not too bad,” “harmful to the image (or competencies) and thereby the roles of most recipients, but actually good for some of them,” “can’t imagine anything better.” This will help the assessment team to know whether to look at the low or high end, or the middle, of the levels.

If raters adhere faithfully to the rating criteria, and once they acquire some experience with PASSING, they will probably find that the determination of a Level 3 is the most difficult, followed by the determination of a Level 2. Level 5 should be the easiest to determine.

Even in the ratings that do not specifically assess service groupings, the nature of the grouping can account for services receiving a certain level. Namely, Level 2b and Level 4a both have provisos to the effect that different recipients are affected differently enough by the service feature being assessed as to warrant a Level 2 or Level 4. Usually, this would happen when a grouping is composed of people who do not have the same or similar identities, needs, and/or vulnerabilities.

This entire section will be of special interest to readers who have used the earlier (2nd, 1983) edition of PASSING, but it should also be read by all users because it explains certain rationales behind some of the contents and language of this edition.

This third edition is an extensive revision of the second (1983) one, but has not attempted to incorporate every conceivable revision that might have improved the text even more. Below, we explain eighteen changes that have been made, and three conceivable ones that have not.

1. The terms normalization and normalizing have been replaced throughout the text by Social Role Valorization, SRV, and role-valorizing. However, this is not merely a wording change, but also one of underlying theory, which the new text also reflects.

2. The authors decided to no longer use PASSING as an acronym, as in the previous edition in which PASSING stood for Program Analysis of Service Systems’ Implementation of Normalization Goals. So now PASSING is a name, rather than an acronym, and the book has a new subtitle: A Tool For Analyzing Service Quality According to Social Role Valorization Criteria. Ratings Manual This allows continuity with the previous edition, but without having to come up with a contrived new name to fit the pre-existing acronym.

3. Generally, the language has been changed so as to no longer imply that the service being assessed is necessarily run by a formal service agency, or that the servers are paid service workers. Accordingly, the term “service client” has been changed to “service recipient”; and the terms “service worker” and “service staff” have been changed to “server” in those instances where the text is meant to include both people who work for pay and can therefore be considered employed or hired staff, as well as people who serve voluntarily or for free and can therefore not be considered employees. In those instances where the text is meant to apply only to paid servers, or only to unpaid ones, this is now clearly stated. In some examples, the words “clients” and “staff” may still be found if they are fitting to the example.

4. There were also changes in the names of several ratings and rating clusters, so that the number of the rating or rating cluster is now more important than its name in relating PASSING to the 1983 edition of the Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality (see footnote 6 on p. 4). However, behind a few of the minor name changes are some significant content changes, especially in the cases of R124, R131, R222, and R223 (see points 8, 9 and 10 below).

What Was Called, in the 1983 2nd Edition… …is Now Called, in the 2007 3rd Edition:

12 Image-Related Service-Structured

12 Image-Related Service Structured Groupings & Relationships Among People Groupings, Relationships, & Social Juxtapositions

123 Image Projection of Intra-Service Client

123 Image Projection of Intra-Service Grouping Composition Recipient Grouping Composition

R1231 Image Projection of Intra-Service Client R1231 Image Projection of Intra-Service Grouping Social Value Recipient Grouping Social Value

R1232 Image Projection of Intra-Service

R1232 Image Projection of Intra-Service Client Grouping Age Image Recipient Grouping Age Image

R124 Image-Related Other Integrative Client R124 Image-Related Other Contacts & Personal Relationships Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships

What Was Called, in the 1983 2nd Edition…

125 Service Worker Image Issues

R1251 Service Worker-Client Image Transfer

R1252 Service Worker-Client Image Match

R131 Culture-Appropriate Separation of

…is Now Called, in the 2007 3rd Edition:

125 Server Image Issues

R1251 Server-Recipient Image Transfer

R1252 Server-Recipient Image Match

R131 Culture-Appropriate Separation or Program Functions Combination of Program Functions

R133 Promotion of Client Autonomy & Rights

14 Image-Related Miscellaneous Other Service

R133 Promotion of Recipient Autonomy & Rights

14 Image-Related Miscellaneous Other Language, Symbols & Images Service Practices

R141 Program Address of Client Personal

R141 Service Address of Recipient Personal Impression Impact Impression Impact

R1432 Agency, Program, Setting, & Location

R1432 Serving Entity, Program, Setting, & Name Location Name

211 Setting Accessibility

R2111 Setting Accessibility Clients &

211 Setting Access

R2111 Setting Access Recipients & Families Families

R2112 Setting Accessibility Public

22 Competency-Related Service-Structured

R2112 Setting Access Public

22 Competency-Related Service-Structured Groupings & Relationships Among People Groupings & Relationships

221 Competency-Related Intra-Service

221 Competency-Related Intra-Service Client Grouping Recipient Groupings

R2211 Competency-Related Intra-Service

R2211 Competency-Related Intra-Service Client Grouping Size Recipient Grouping Size

R2212 Competency-Related Intra-Service

R2212 Competency-Related Intra-Service Client Grouping Composition Recipient Grouping Composition

R222 Competency-Related Other Integrative

R222 Competency-Related Other Client Contacts & Personal Relationships Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships

R223 Life-Enriching Interactions Among

R223 Life-Enriching Interactions Among Clients, Service Personnel, & Others Recipients, Servers & Others

R224 Program Support for Client

R224 Service Support for Recipient Individualization Individualization

R225 Promotion of Client Socio-Sexual

R225 Promotion of Recipient Socio-Sexual Identity Identity

R231 Program Address of Clients’ Service

R231 Service Address of Recipient Needs Needs

5. Spelling, grammatical, punctuation, and similar typesetting errors have been corrected. These were minor. The authors fervently hope no new ones have been introduced.

6. The section formerly entitled “Suggestions on How to Read, Study and Use the PASSING Ratings Manual” has a slightly different title, and contains some content revisions as well.

7. A very significant amount of editing and changing of both text and examples was done, though this is more obvious in certain sections and ratings than in others. This includes cleaning up of a number of conceptual errors in the previous edition. Some improvements of text wording were major, some minor. However, some of what appear to be minor changes in wording have considerable impact, and could change (a)the rating by which a service feature is assessed, or (b) the level assignment it receives on that rating.

8. One of the differences between normalization and SRV is that normalization was ideology mixed with empiricism, whereas SRV is an attempt to be a more purely empirical theory, which a party may (or may not) decide to employ based on that party’s ideology (see also footnote 7 on p. 8). This has implications especially to the issue of social integration (see definition on p. 33 in “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms”). In this edition of PASSING, only SRV-derived rationales for integration are considered, and not any nonempirical/ideological ones, meritorious as the latter may be. This accounts for the fact that in this edition of PASSING, a service may receive credit in at least some situations where its recipients are grouped and/or juxtaposed to certain societally devalued people. The reason is that while competency and positive social valuation are highly correlated (so that the more competent people are, the more they are likely to be valued, and the more valued people are, the more they are likely to be afforded opportunities to enhance their competencies), nevertheless, marginal people, or even outright devalued ones, may have many competencies, even valued competencies, and can thereby serve as models in certain respects for recipients.

This distinction between valued competent parties and devalued competent ones also helps to clarify that the image benefits that accrue to devalued people from their social integration with valued people in valued activities and valued settings are not necessarily the same as the competency benefits that may or may not accrue to them from such integrative participation. Similarly, the distinction made above helps to differentiate the competency benefits that can accrue to devalued parties from their association with others who are more competent (even if these others are not highly valued), from the image transfers that come from such associations and such image transfers may actually be very negative even when the competency benefits are great.

These theoretical insights have had considerable effect on the reconceptualization of two grouping ratings (R1231 Image Projection of Intra-Service Recipient Grouping Social Value, and R2211 Competency-Related Intra-Service Recipient Grouping Composition); and on the reconceptualization and renaming of ratings R124 Image-Related Other Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships and R222 Competency-Related Other Recipient Contacts & Personal Relationships. In contrast to the previous edition, this edition of PASSING now makes clearer that both image-enhancement and competency-enhancement can derive from contacts that are not necessarily only with people who are highly valued. In other words, this edition of PASSING is clearer that while social integration with valued people in valued activities and valued settings tends to be the most image-enhancing for devalued people, and is often the most competency-enhancing strategy, it is nonetheless sometimes possible for the image and competencies of devalued people to be improved (sometimes greatly so) through social juxtapositions and contacts even if these are not, or are not always, with valued people.

9. In the 2nd (1983) edition of PASSING, the rating R131 looked only at whether a service inappropriately combined program functions that are normatively conducted separately in open society. However, as can be seen from its name change (R131 Culture-Appropriate Separation or Combination of Program Functions), the rating now also looks at whether the service inappropriately separates functions that are typically conducted jointly in valued society.

10. We realized that in the 1983 (2nd) PASSING edition, some of the elements of R223 LifeEnriching Interactions Among Servers, Recipients, Servers, & Others (which is one of the competencyrelated ratings) were not SRV issues at all, and that some were more image-related than competencyrelated. In good part, this was due to some unconscious inheritance from the predecessor rating in PASS (see footnote 2 on p. 4) called “R1154 Interactions.” There has therefore been a major revision of R223 in this edition, including in its rating levels.

11. Because the issue of service influence over recipient possessions comes up in three ratings (R133 Promotion of Recipient Autonomy & Rights, R142 Image-Related Personal Possessions, and R233 Competency-Related Personal Possessions), the relationship among these three ratings was clarified.

12. The theoretical developments in recent years around the construct of “model coherency” (see PASS, referenced in footnote 2 on p. 4) have been drawn on to make a better distinction between the ratings of R231 Service Address of Recipient Needs and R232 Intensity of Activities & Efficiency of Time Use.

13. One of the other major changes is that texts which apply to all the ratings in several rating clusters were consolidated, and moved to a spot where it is easier to tell that they do, in fact, apply to all ratings in a cluster. For instance, as shown on the Table of Contents, the text applying to all thirteen ratings under the rubrics “12 Image-Related Service-Structured Groupings, Relationships, & Social Juxtapositions,” and “22 Competency-Related Service-Structured Groupings & Relationships,” has been placed before the text that introduces the ratings that begin with 12…, on pp. 133-136. Similarly, as also shown on the Table of Contents, the text applying to all four ratings under the rubrics “123 Image Projection of Intra-Service Recipient Grouping Composition,” and “221 Competency-Related Intra-Service Recipient Groupings,” has been placed before the text that introduces the ratings that begin with 123, on pp. 155158.

14. All the statements of criteria for the five levels of each rating (called “Criteria and Examples for Level Assignments”) have been revised. While the essence of the levels is not changed thereby i.e., Level 1 is very poor service performance, Level 2 is somewhat poor service performance, Level 3 is “neutral” service performance, Level 4 is good service performance, and Level 5 is ideal service performance, all as before the level statements have all been reworded so as to make the principle of each level, and the distinctions among levels, clearer for raters.

Even more than before, the rating criteria imply that it will be easier for some services to get higher scores than others. Uncomplicated services with a single narrow function, and/or that serve recipients who are not devalued, are more likely to score higher, in part because they face fewer pitfalls, especially in the image domain.

15. In the original 2007 3rd edition, this point dealt with the examples used throughout the text. But since almost all the examples have been eliminated, we are not reproducing that point 15 in this version.

16. This edition contains some changes in the set-up of the book, in response to feedback from users. These format changes are a trade-off: they eliminate certain features of a practical nature, but reduce the bulk of the book, which is an advantage when it is carried around during an evaluation. However, while the Manual has been set up to be easier to use, the application of PASSING to service evaluation has not become easier. In fact, certain refinements in what is covered by certain ratings may even have added a bit of complexity.

17. In this edition of PASSING, there is no section that describes Social Role Valorization in detail as there was on pp. 23-29 of the 2nd (1983) edition of PASSING. This is because SRV has been refined and elaborated in several separate publications since 1983, especially in the following three items:

Wolfensberger, W. (1998). A brief introduction to Social Role Valorization: A high-order concept for addressing the plight of societally devalued people, and for structuring human services (3rd rev. ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Training Institute for Human Service Planning, Leadership & Change Agentry.

Wolfensberger, W. (2000). A brief overview of Social Role Valorization. Mental Retardation, 38 (2), 105-123.

Race, D. G. (1999). Social Role Valorization and the English experience. London: Whiting & Birch.

Instead of the lengthy previous section describing SRV, a much briefer description of SRV has been added in the “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms” on pp. 39-40.

18. Because the names of some of the ratings and rating clusters have been changed, various scoring and reporting forms (including the Checklist and Scoresheet/Overall Service Performance Form ) have been revised. As noted before, the forms are copyrighted, and therefore are not to be photocopied. They should be ordered from Valor Press: https://presse.valorsolutions.ca/en.

Among the things that this revision has not endeavored to do are the following three.

1. The text has not yet been edited so as to fully incorporate all developments in SRV theory since 1983, and especially since the mid-1990s. For instance, much of the text still speaks of people being valued or devalued rather than their roles being valued or devalued.

Also, while PASSING is the most extensive elaboration of SRV, it is not the most authoritative written statement on it (see No. 17 above). One reason is that PASSING contains some discourse and concepts which it inherited from its predecessor PASS, and PASS dealt with the predecessor of SRV, namely normalization. This inherited discourse deals with a few constructs either that are not part of SRV, that approach the limits of SRV, that SRV deals with only partially or indirectly, or at least whose relevance to SRV is debatable. For instance, there are PASSING passages that could be read to imply that a service recipient’s self-image is affected by a service practice. However, SRV is concerned primarily with a party’s image in the eyes of others who are in a position to do good or bad things to that party. Another example is the construct of need, which plays an especially large role in R231 Service Address of Recipient Needs. So far, SRV theory has not completely resolved to what degree the need construct fits into SRV theory.

Therefore, readers and users of this Manual should first obtain and read at least the above - listed 1998 publication (see point No. 17 above) before attempting to apply PASSING to a service. Additionally, in order to validly use PASSING, a person should first have attended an Introductory Workshop in Social Role Valorization of at least 3 days’ duration.

However, the PASSING Manual alone is sufficient to engage in service design and planning, though of course, additional reading and training in SRV would almost certainly enhance that process.

2. Though certain additional improvements in organizing the text have already been conceptualized and partially drafted, they have not yet been incorporated.

3. Readers will note that this edition of PASSING, just like the previous one, does not use so-called “people-first” language, i.e., it does not always put the words person, individual, or people before any modifying adjective. For instance, it uses the phrase “impaired person” rather than “person who has an impairment” (or person who is called, labeled, etc. as impaired). The reason this is mentioned is that since the previous edition of PASSING was published, so-called “people-first” language has become a practice that is considered progressive, and even mandatory, in many fields of service to impaired and otherwise devalued people. Some people are outright fanatical about this issue, and assign vastly exaggerated importance to it. Some potential users of PASSING might therefore be surprised to find in it what they consider to be out-dated and even offensive (maybe extremely offensive) language. Therefore, the authors of PASSING decided to briefly explain why such people-first language is not used in PASSING:

a. Those who advocate the practice often claim that putting the adjective after the words person, individual, people, etc., will improve people’s attitudes towards any such persons described. However, SRV strives to be an empirical theory, and we know of no empirical evidence of the validity of this language claim, and consider even its theoretical basis to be dubious.

b. Putting the adjective after rather than before the noun that it modifies violates what linguists call the “natural rules” of the English language, which can and does place the adjective in front of virtually all nouns (e.g., cloudy skies, pretty face, menacing intruder). Insisting that a different sentence construction be used only in regard to impaired and societally devalued people sets those people and classes linguistically apart from everyone else, and requires that people artificially and awkwardly refrain from speaking or writing in a way that is natural to their native tongue This can actually be “languagesegregative” and counterproductive.

c. Advocates of people-first language often claim that such language is what impaired and devalued people themselves want. However, we do not believe that what any person, group, or class wants should be the overriding determinant of what everyone else must do, in this case or in any other respect, and especially not if what people want violates morality, empiricism, or rationality. In this case, it certainly violates rationality, by violating the “natural rule” of English (noted in “b” above), and probably also empiricism as well.

Therefore, PASSING uses culturally normative and natural sentence constructions.

The minor changes in this edition over the previous one in what gets rated by the different ratings, plus the changes in how the level assignments are to be made, mean that it cannot be taken for granted that the research studies8,9 on the previous edition of PASSING are fully applicable to this new edition, though it is quite likely that new research would come up with comparable conclusions. However, we do not believe that a short form of this new edition of PASSING should be based on the ratings that Flynn (1999; see footnote 8) recommended for a short form of the 1983 edition, unless new cross-validated research on real assessments (rather than on training assessments) has shown that such a short form has sufficient predictive validity.

Overall, this edition of PASSING is not simpler than the previous one, but it is clearer, more accurate, and in at least some ways more “user-friendly.”

The PASSING instrument was more than 20 years old at the time of this revision. Still the authors believe that the concepts and ideas in it, and its structure, have stood the test of time very well, even if some of the examples had become slightly outdated.

People who have used, learned, and/or taught the previous edition of PASSING absolutely MUST make a careful and serious study of this new edition, and especially of the subtle changes, such as in the rating levels. Otherwise, they will carry over to this edition practices they learned with the previous edition that have changed, and are no longer valid.

All references to PASSING page numbers in the monograph entitled Guidelines for Evaluators During a PASS, PASSING, or Similar Assessment of Human Service Quality (see footnote 6, on p. 4) are to the 1983 edition of PASSING. This will be corrected when the Guidelines are revised. Further, the language of the 1983 Guidelines is still reflective of normalization rather than SRV.

8Flynn, R. J. (1999). A comprehensive review of research conducted with the program evaluation instruments PASS and PASSING. In R. J. Flynn, & R. A. Lemay (Eds.), A quarter-century of normalization and Social Role Valorization: Evolution and impact (pp. 317-349). Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa Press.

9Flynn, R. J., LaPointe, N., Wolfensberger, W., & Thomas, S. (1991). Quality of institutional and community human service programs in Canada and the United States. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 16, 146-153.

As mentioned, a reader should be able to get at least a basic understanding of SRV and its implications just by reading this Manual (though that alone is not sufficient to give anyone a complete understanding of SRV, nor mastery of the PASSING instrument).

The best way to start learning PASSING is to read through the Ratings Manual from beginning to end. However, to become expert at using the Manual for the evaluation of services, much further study and review is required. One possible regimen of study that some users may find useful and beneficial is sketched below, but others may prefer a different approach.

1. Keep in mind that you will probably have to make repeated recourse to the “Alphabetic Glossary of Special Terms” (pp. 29-40).

2. Read the explanation of the importance of social image enhancement (pp. 41-52).

3. Review the section you have just read on imagery and image enhancement. Now read all those ratings which have to do with social image enhancement, i.e., the twenty-seven ratings and their preceding introductions that have a code number beginning with “1...” or “R1.”

4. Read the explanation of the importance of personal competency enhancement (pp. 283286).

5. Review the discussion of competency enhancement that you have just read. Now read all those ratings which have to do with personal competency enhancement, i.e., the fifteen ratings and their preceding introductions that have a number beginning with “2...” or “R2.”

6. As you read each rating, follow this procedure:

a. Read the “General Statement of the Issue” section first. Then stop reading, and try to jot down very briefly (in one or two short, simple sentences) the issue at stake in the rating. For example, after having read the “General Statement of the Issue” for the rating R1111 Setting-Neighborhood Harmony, stop reading, and write a statement that captures the essence of that rating, such as the following: “In order to be role-valorizing, the appearance of a human service setting should blend in enhancingly with its neighborhood.” If you have trouble summarizing what you have read in the rating, then re-read the “General Statement of the Issue” again; if you continue to have difficulties, make a note to the authors to consider a future revision of the passage.

b. After you have read the “General Statement of the Issue” and have written your own brief statement of the issue, turn next to the “Rating Requirements Chart,” and read the statement of the rating issue in the column entitled “SRV Requirements.” See if the statement you just wrote comes close to the short statement of the issue in that column. If so, you probably understand fairly well what the rating is about.

10The authors are indebted to John O’Brien, whose similar guide for users of PASS was the model used to construct this guide.

If you are only trying to learn about SRV, but are not going to use PASSING to assess a service, you can skip step 6c, and proceed to number 6d