with Kentucky Explorer

with Kentucky Explorer

Writer John Mitchell Johnson fondly recalls a formidable figure from his childhood

The Heinous Harpe Brothers Kentucky Mountain Workshops Spooky Sites in the Commonwealth

The Potential for Maple Syrup Production in Kentucky

14 In Their Own Words The Mountain Workshops help young photojournalists hone their craft while giving “ordinary” people a platform to tell their stories

20 Mindless Mayhem The notorious Harpe Brothers embarked on a bloody odyssey primarily in frontier Kentucky

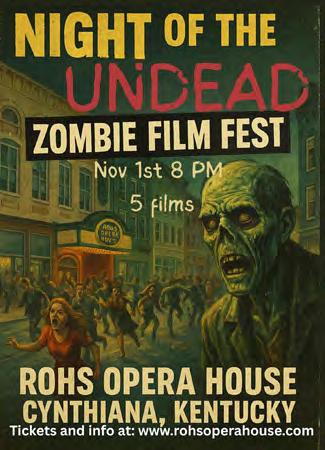

24 Spooky Sites With the scary season approaching, it’s a great time to tour these creepy locales and attend haunted happenings across Kentucky

30 Look Out, Vermont Kentucky’s maple syrup industry has untapped potential

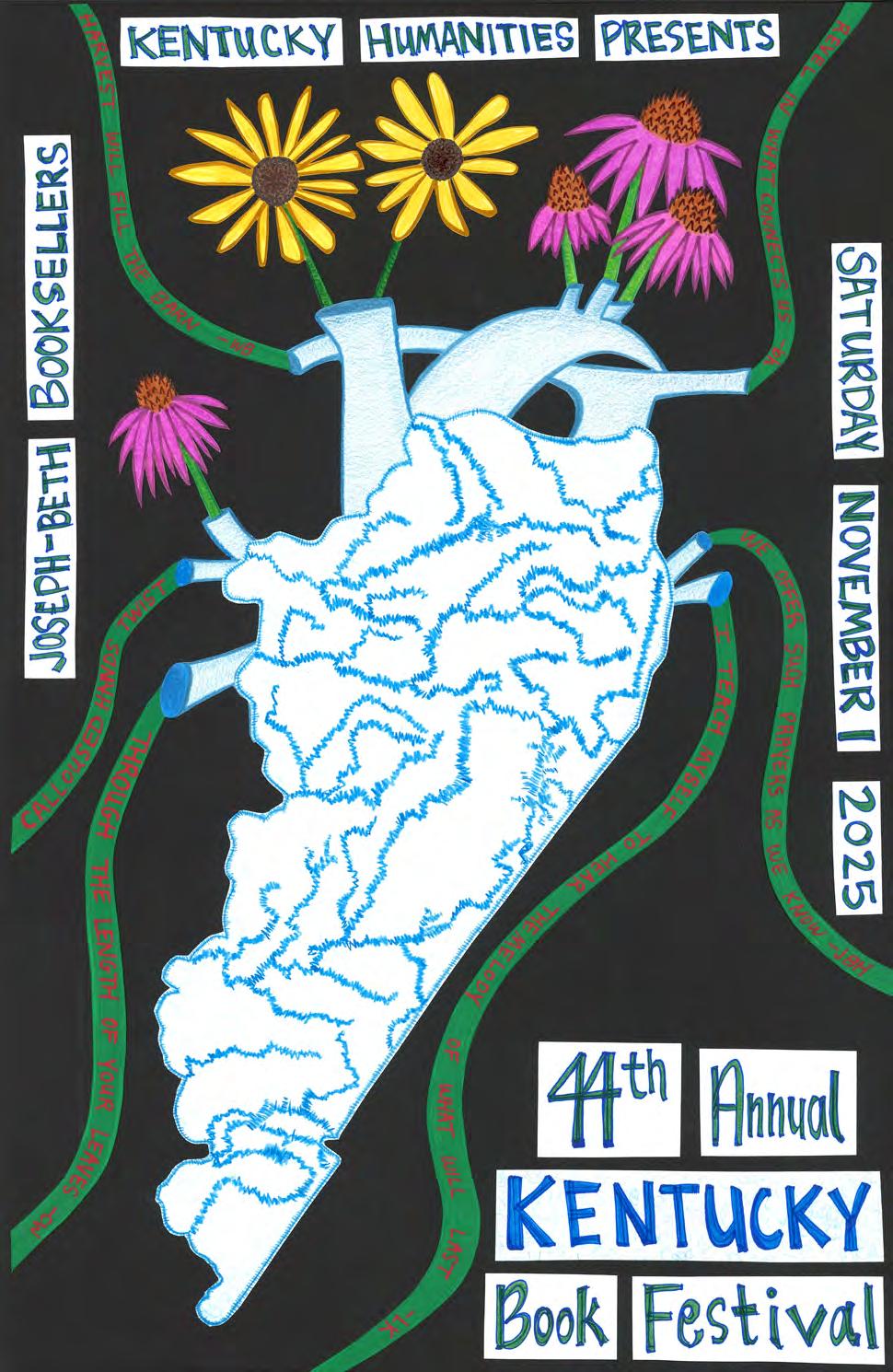

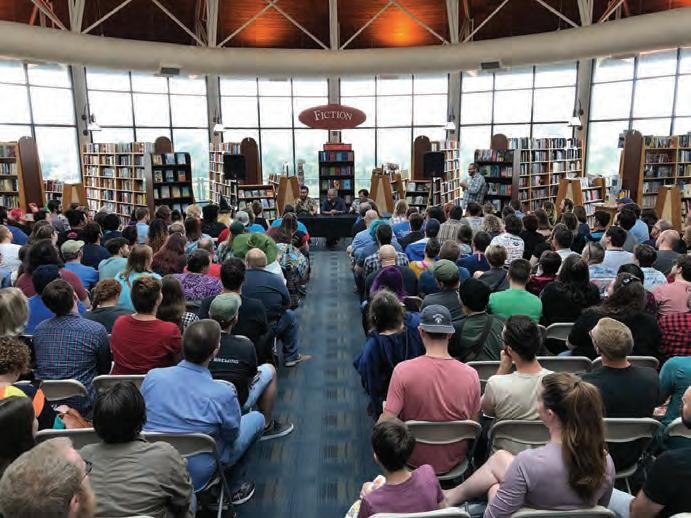

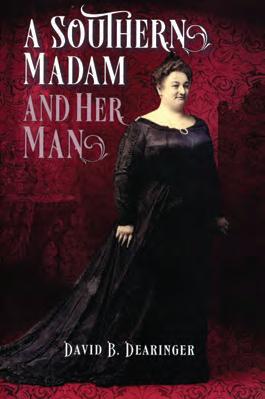

33 Kentucky Book Festival The Kentucky Humanities presents the 44th edition of the event at JosephBeth Booksellers in Lexington

Test your knowledge of our beloved Commonwealth. To find out how you fared, see page 5.

1. Which tavern in Northern Kentucky is thought to house “spirits” aside from those of the wine, beer and bourbon varieties?

A. Mansion Hill Tavern in Newport

B. Blinkers Tavern in Covington

C. Three Spirits Tavern in Bellevue

2. The spirit of J. Graham Brown is said to linger frequently on the mezzanine of which Louisville hotel?

A. The Galt House

B. The Seelbach Hilton

C. The Brown Hotel

3. With a variety of ghostly activity— including footsteps, whispers and spectral sightings—which Western Kentucky University building is thought to be haunted by the spirit of a man who fell through a skylight in the early 1900s?

A. Van Meter Hall

B. Potter Hall

C. Ivan Wilson Fine Arts Center

4. Two Louisville Police pilots, responding by helicopter to a possible break-in, encountered what object flying in the night sky in February 1993?

A. A thunderbird

B. A UFO (now known as a UAP)

C. A flock of seagulls

5. Though not known as haunted, the life-sized statues of 15 members of the Wooldridge family at which cemetery was considered creepy enough to be listed on the Kentucky After Dark passport program?

A. Riverside Cemetery, Hopkinsville

B. Eastern Cemetery, Louisville

C. Maplewood Cemetery, Mayfield

6. Paranormal activity has been reported in several areas of Louisville’s Cave Hill Cemetery, including around the graves of Mildred Jane Hill and Patty Smith Hill, the two women who wrote what popular tune?

A. “My Old Kentucky Home”

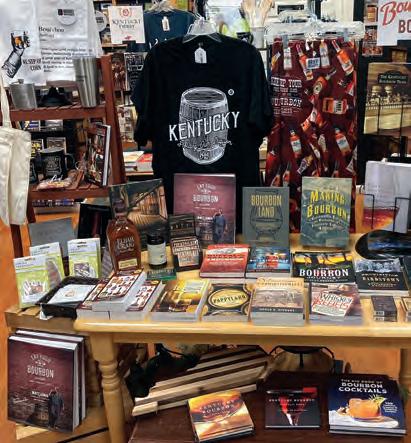

B. “Happy Birthday”

C. “Blue Moon of Kentucky”

7. What lake in Central Kentucky is said to be the home of a creature nicknamed the “Eel-Pig?”

A. Herrington Lake

B. Taylorsville Lake

C. Lake Linville

8. According to the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization, people in approximately how many Kentucky counties have reported sightings of Bigfoot, a creature typically said to be more than 7 feet tall and covered in fur?

A. 0

B. 20

C. 50

9. Whose spirit is alleged to most frequently haunt the Pikeville Cemetery in Pikeville?

A. Octavia Hatcher, who was buried alive accidentally and then suffocated in the grave

B. William Howard, a Confederate soldier

C. Devil Anse Hatfield

10. What state correctional facility is said to be one of the most haunted locations in Kentucky?

A. Kentucky State Penitentiary, Lyon County

B. Old Jailers Inn, Nelson County

C. Eastern Kentucky Correctional Complex, Morgan County

Contributed by Dr. Tamela Williams Smith, CEO & Founder of Dr. Smith’s Spooky Stories, LLC.

© 2025, VESTED INTEREST PUBLICATIONS

VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT, ISSUE 8, OCTOBER 2025

Stephen M. Vest Publisher + Editor-in-Chief

Patricia Ranft Associate Editor

Rebecca Redding Creative Director

Deborah Kohl Kremer Assistant Editor

Ted Sloan Contributing Editor

Cait A. Smith Copy Editor

SENIOR KENTRIBUTORS

Jackie Hollenkamp Bentley, Jack Brammer, Bill Ellis, Steve Flairty, Gary Garth, Kim Kobersmith, Brigitte Prather, Walt Reichert, Tracey Teo, Janine Washle and Gary P. West

BUSINESS AND CIRCULATION

Barbara Kay Vest Business Manager

Katherine King Circulation Assistant

Lindsey Collins Senior Account Executive and Coordinator

Kelley Burchell Account Executive

Laura Ray Account Executive

Teresa Revlett Account Executive For advertising information, call 888.329.0053 or 502.227.0053

KENTUCKY MONTHLY (ISSN 1542-0507) is published 10 times per year (monthly with combined December/January and June/ July issues) for $25 per year by Vested Interest Publications, Inc., 100 Consumer Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601. Periodicals Postage Paid at Frankfort, KY and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to KENTUCKY MONTHLY, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602-0559. Vested Interest Publications: Stephen M. Vest, president; Patricia Ranft, vice president; Barbara Kay Vest, secretary/ treasurer. Board of directors: James W. Adams Jr., Dr. Gene Burch, Gregory N. Carnes, Barbara and Pete Chiericozzi, Kellee Dicks, Maj. Jack E. Dixon, Mary and Michael Embry, Judy M. Harris, Jan and John Higginbotham, Frank Martin, Bill Noel, Walter B. Norris, Kasia Pater, Dr. Mary Jo Ratliff, Randy and Rebecca Sandell, Kendall Carr Shelton and Ted M. Sloan.

Kentucky Monthly invites queries but accepts no responsibility for unsolicited material; submissions will not be returned.

KENTUCKYMONTHLY.COM

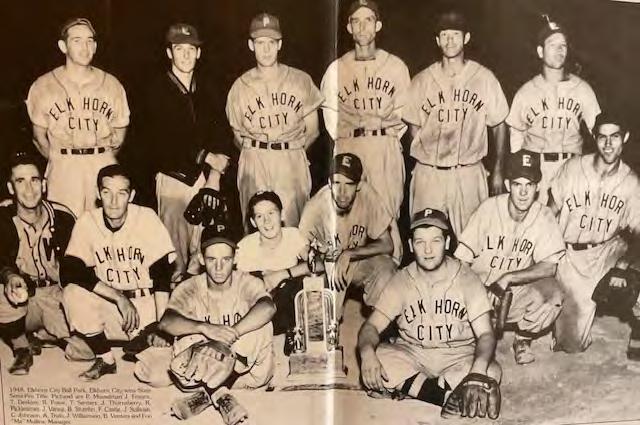

I enjoyed the April issue’s article on baseball in Kentucky (page 36) but was disappointed that there was no mention of the semi-pro mountain baseball leagues of the 1940s. Until 1951, 22 semipro baseball clubs graced the Big Sandy Valley, many sponsored by coal companies.

In 1949, more than 120,000 attended the clubs’ games. For the four state tournaments played in Pikeville and Elkhorn City, attendance was more than 100,000. Unfortunately,

the disappearance of the prosperity of the war years ended these clubs.

Below is a photo of the Elkhorn City Club, the 1948 winners of the State Semi-Pro Title and one of six teams in the Elkhorn League, which included Wheelwright, Drift, Weeksbury, Wayland and Pikeville.

Pat Caudill Cole, Elkhorn City

Thanks to Bill Ellis for his article on old farms (August issue, page 58). It reminded me of my

grandparents farm that we visited when we were young.

Donna Bresser, Edgewood

I enjoy your magazine, especially Bill Ellis. I am from Shelbyville and fondly recall the way of life he writes about.

Please check out the articles on online about my son-in-law, Cole Stamper (of Wheatley, Owen County), as he [and his brother, Forest] won the SPEC MIX Bricklayer 500 World Championship twice. They laid 730 bricks in an hour to claim the title “World’s Best Bricklayer.”

Cole supervised and laid the stone at Keeneland and recently got back from winning the Super Trowel brick competition in England.

Teresa Biagi, Worthville (Carroll County)

We Love to Hear from You! Kentucky Monthly welcomes letters from all readers. Email us your comments at editor@kentuckymonthly.com, send a letter through our website at kentuckymonthly.com, or message us on Facebook. Letters may be edited for clarification and brevity.

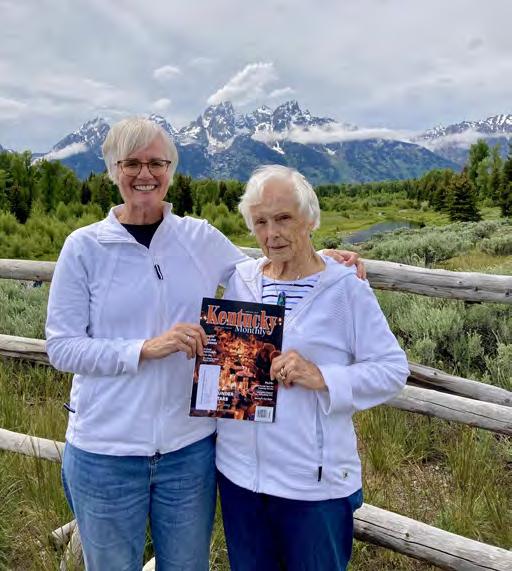

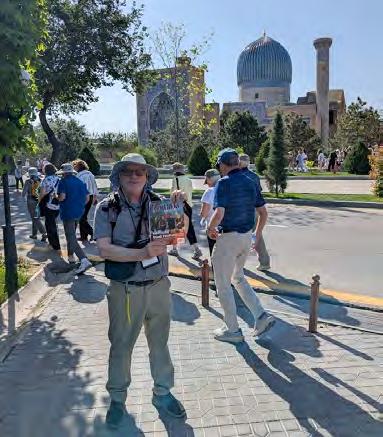

Even when you’re far away, you can take the spirit of your Kentucky home with you. And when you do, we want to see it!

Marsha Nauman, left, and her mother, Nadine Brown—both of Bowling Green—visited and took in the majestic views of Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park.

Isaac Joyner of Lexington traveled to Uzbekistan, where he is pictured in Samarkand, one of the stunning cities on the historical Silk Road.

Ginny and Brad Logan of Harrodsburg took a little piece of Kentucky on their trip to The Big Apple. They are pictured in Times Square.

submit your photo

Take a copy of the magazine with you and get snapping! Send your high-resolution photos (usually 1 MB or higher) to editor@kentuckymonthly.com or visit kentuckymonthly. com to submit your photo.

KWIZ ANSWER: 1. C. The three spirits are thought to be members of the Funken family, who built the Bellevue house and lived there in the 1880s; 2. C. The Brown Hotel was built by J. Graham Brown in 1923, and apparently, he is still watching over it; 3. A. Legend has it that a worker was killed during construction, but the death actually was that of a student from another school who fell in 1918 while looking for an airplane; 4. B. The two experienced pilots observed a UFO that fired three fireballs at their helicopter. No one was harmed. Louisville Police officers on the ground also observed the object; 5. C. Nicknamed “The Strange Procession That Never Moves,” the statues were commissioned by Col. Henry G. Wooldridge to honor his family; 6. B. “Happy Birthday” was written by the Hill sisters in 1893; 7. A. Reports of the Herrington Lake monster have existed since the lake was created in 1925, with the best-known sighting occurring in 1972 by a University of Kentucky professor; 8. C. Bigfoot reporting organizations list varying numbers, but at least 50 Kentucky counties have reported activity; 9. A. Hatcher fell into a coma and was believed dead. After others became ill in a similar manner, she was exhumed, and her coffin showed scratching and tearing on the inside lining, indicating that she had awakened in the grave; 10. A. Completed in 1886, the prison houses maximumsecurity and death-row inmates. With the number of deaths there, including murders and suicides, it is not surprising prisoners and staff have reported ghostly activity.

Bob and Martina Durrett of Crestview Hills and their daughter and son-in-law, Sue and Andy Weibel, of Fort Mitchell enjoyed an American Cruise Line river cruise of the Columbia River Gorge.

When funding for public radio was severely cut last summer, Daniel Martin Moore and other Kentucky musicians stepped in to help. Moore is a musician, singer, songwriter and producer originally from Cold Spring in Campbell County.

A federal bill was signed into law that cut approximately $1.1 billion of funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which supports local public radio and public television stations. Some stations are predicted to close due to lack of funding.

Louisville Public Media (LPM) has three radio stations—WFPK, WUOL and WFPL—and after the bill passed, LPM faced a $376,000 deficit. Knowing how damaging that would be to the stations, Moore asked musician friends to contribute songs to a collection that public radio stations across the state can use as membership incentives. The only requirement to get the download of the songs is to be a current or new member of a Kentucky public radio station.

“I think we all recognize how important it is to have media that comes from our communities,” he said.

“Congress rescinded funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting on Friday, July 18, around 1 a.m.,” said Kelly Wilkinson, membership director for LPM. “We went on air with an emergency fundraising campaign that same morning at 6 a.m. Donations flooded in over the next 36 hours.

“The immediate need for us was $376,000 … We hit that goal on Saturday morning, July 19. We stopped asking for donations on-air on Saturday around noon, when the tally was just above $400,000. Over the next week or so, people continued to donate. The final total raised was around $500,000.”

“When Laura Shine [senior host and producer at WFPK] needs something, we’re there,” Moore said.

“Everyone I contacted wanted to help,” Moore said. He said Ben Sollee, Joan Shelley, Jim James and the members of My Morning Jacket agreed right away.

“Almost everything here has never been heard before,” Moore said of the collection.

Artists of all ages and genres are represented. The only requirement to be included was that the musicians had to be from Kentucky or built their careers in Kentucky. Moore said My Morning Jacket contributed a cover of a Bob Marley song. Jecorey Arthur did a spiritual, while Teddy Abrams, the director of the Louisville Orchestra, contributed an original piano piece.

Moore said the musicians wanted to help because of their love of public radio. He talked about WFPK, the independent music station at LPM, and its relation to local musicians. “They have supported us to an incredible degree over the years,” he said. “We deeply appreciate that.”

While the idea originated with a Louisville musician, the project is available to any public radio station in the state that would like to use the music collection for their membership drives. Moore pointed out that public radio stations in smaller communities cover music, local and national news and even weather alerts for their community.

“It was so moving. I’ve been the local music liaison for over a decade, making sure we support our musicians,” Shine said. “I rarely ask for anything from them. It truly felt like an unsolicited gift to us all, and I’m feeling tears swell up right now as I’m thinking about it.”

It almost felt like the last scene of the Christmas film classic It’s a Wonderful Life. Not exactly, according to Moore. “Mr. Potter’s still out there,” he said. “He’s not done.”

Shine said that the day Congress rescinded funding was important to her. “I’ve never felt the support as much as I did that day. What started out as the worst day in public radio turned into the best day, ever,” she said. “When Daniel gathered all of those musicians to pledge their support to not just us but to all of the public radio stations in Kentucky, it blew my mind.”

Moore said that 26 tracks have been gathered, are being engineered by Kevin Ratterman, and should be ready for downloads by press time.

Moore also said he headed the project because he’s “just trying to resist the slow creep of cynicism.” Moore toured with British musician Billy Bragg throughout the United Kingdom several years ago, and Bragg believes in being positive and doing good.

Bragg’s outlook rubbed off on Moore, who is following Bragg’s advice of “trying to stay focused on what you want to achieve and not just throw up your hands. Keep your spirit alive.”

In her new book, The Modern Mountain Cookbook, Eastern Kentucky native Jan A. Brandenburg takes beloved recipes from her childhood and substitutes ingredients to conform to her vegan lifestyle. Following years of trial and error, she presents these timeless Appalachian classics with a health-conscious, plant-based twist to be enjoyed by vegans and carnivores alike.

SERVES 8-10

1 7-ounce block vegan cheddar, cut into a medium dice

8 ounces vegan cream cheese

1 tablespoon minced garlic

1 tablespoon hot sauce (I use the Kentucky-based Screamin’ Mimi’s Pepper Sauce)

1 teaspoon vegan Worcestershire sauce

½ cup flat IPA

¼ teaspoon cayenne

1. Allow the cheese to come to room temperature. Place all the ingredients in a food processor or high-speed blender (the soup speed works well) and process until completely smooth.

2. Pour into a container, cover with plastic wrap, and press the wrap onto the top of the mixture.

3. Refrigerate overnight or for several hours prior to serving.

Recipes and images courtesy of Jan A. Brandenburg’s The Modern Mountain Cookbook: A Plant-Based Celebration of Appalachia, © 2025 The University Press of Kentucky. Used by permission.

MAKES 24 LARGE OR 36 SMALL COOKIES

¾ cup sugar

¾ cup brown sugar

1 cup vegan butter, softened

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

1/3 cup applesauce

1 tablespoon vegan egg replacer powder

2¼ cups unbleached all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

1 12-ounce bag vegan semisweet chocolate chips

½ cup old-fashioned rolled oats

½ cup chopped pecans or walnuts (optional)

Flaky sea salt for garnish (optional)

1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Line a baking sheet with parchment paper and set aside.

2. With an electric mixer, cream together both sugars and the vegan butter. Add the vanilla, applesauce and vegan egg replacer. Beat at medium-high speed until fluffy and creamy, 2-3 minutes.

3. Sift together the flour, baking soda and salt and add to the butter mixture. Mix at low speed until fully incorporated.

4. Fold in the chocolate chips, oats and nuts. Drop by rounded tablespoons onto the baking sheet.

5. Bake for 12-15 minutes or until golden brown. Cool on a wire rack. Garnish with flaky sea salt if desired.

2 pints vegan sour cream

1 cup powdered sugar

1½ teaspoons vanilla extract

1/8 teaspoon salt

42 vegan chocolate wafers

1 pound strawberries, rinsed, hulled and sliced

1/3 cup granulated sugar

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1. Line a 9- by 5-inch loaf pan with plastic wrap. Place one sheet vertically and one horizontally, leaving a few inches hanging over the sides.

2. In a medium bowl, whisk together the vegan sour cream, powdered sugar, vanilla and salt until smooth.

3. Arrange a layer of wafers on the bottom of the pan, keeping the layer as level as possible. Spread with 1 cup of the sour cream mixture. Repeat with 2 more layers of wafers and sour cream, ending with the sour cream mixture.

4. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate at least 12 hours.

5. In a medium saucepan, combine the strawberries, granulated sugar and lemon juice. Bring the mixture to a boil, stirring frequently. Reduce heat and simmer 20-25 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the sauce thickens. Remove from heat and cool to room temperature before refrigerating.

6. To serve, carefully lift the chilled icebox cake from the pan using the overhanging plastic wrap. Flip the cake onto a cutting board with the wafer side up and gently peel away the wrap. Spoon a couple tablespoons of strawberry sauce on each serving plate. Using a sharp serrated knife, slice the cake into 10 portions. Arrange the slices on the serving plates and top with additional strawberry sauce if desired.

SERVES 8

½ stick vegan butter

2 cups chopped celery

1 onion, chopped

3 tablespoons chopped green pepper

1 14.5-ounce can stewed tomatoes, puréed

2 cups fresh corn

1 teaspoon sea salt

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ teaspoon paprika

½ cup whole cashews

½ cup filtered water

1½ cups vegetable broth

½ cup shredded vegan cheddar

3 tablespoons unbleached all-purpose flour

½ cup chopped pimento

1. Melt the vegan butter in a large pot over medium heat. Add the celery, onion and green pepper and sauté for 10 minutes or until onion is translucent.

2. Stir in the puréed tomatoes, corn, salt, pepper and paprika. Simmer 30 minutes. Remove from the heat and set aside.

3. In a high-speed blender, combine the cashews, filtered water and vegetable broth. Blend at high speed for 1-2 minutes or until smooth. Add the shredded cheddar and blend an additional 1 minute. Add the flour and blend for 1-2 minutes until smooth and creamy.

4. Stir the cheese mixture into the soup, along with the pimento. Return to the heat and stir until the soup is heated through and thick. Serve immediately.

1. Preheat oven to 400 degrees. Toss chick’n with 1 tablespoon olive oil and bake on nonstick aluminum foil for 20 minutes. Set aside to cool, then chop into cubes.

2. To make the crust, place the flour, sugar and salt in the bowl of a food processor and pulse to combine. Cut the vegan butter into small pieces and add to the bowl. Pulse about 10 times, or until the mixture looks like coarse meal.

3. Slowly drizzle the water into the mixture while pulsing until the dough holds together when pressed between two fingers. Shape into a large disc, wrap in wax paper, and refrigerate at least 1 hour.

4. While dough is chilling, heat 3 tablespoons olive oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Add the shallots and cook 4-5 minutes. Add the carrots, potatoes and peas, and stir to combine. Continue to cook for another 10 minutes,

Chick’n

10 ounces nonbreaded chick’n (a plant-based chicken alternative)

1 tablespoon olive oil

Crust

2½ cups unbleached all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt

2 sticks (1 cup) vegan butter

¼-½ cup ice water

Filling

3 tablespoons olive oil

2 small shallots, finely chopped

3 carrots, thinly sliced on the bias

2 large potatoes, cubed

½ cup fresh or frozen peas

½ cup dry white wine or white cooking wine

2 cups no-chicken broth

1 teaspoon dried thyme

5 teaspoons cornstarch whisked with 2 tablespoons cold water

¾ cup vegan half-and-half

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh parsley

until the vegetables begin to soften.

5. Stir in the wine and simmer until the liquid is reduced by half. Add the broth, thyme and browned chick’n and cook another 4 minutes.

6. Add the cornstarch mixture and vegan half-and-half. Cook an additional 5 minutes, stirring occasionally, until the mixture is thick and bubbly. Stir in the salt, pepper and parsley and pour into a casserole dish.

7. Place the chilled dough on floured wax paper and roll into a rectangle. Place dough on top of the casserole to cover completely and use a sharp knife to trim the edges. Pierce the crust with a fork 10-15 times. Bake on the middle rack of the oven for 40 minutes or until the crust is golden brown and the mixture is bubbly. Serve hot.

Meet author Jan A. Brandenburg and purchase a copy of The Modern Mountain Cookbook:

A Plant-Based Celebration of Appalachia at the Kentucky Book Festival on Nov. 1 at Joseph-Beth Booksellers in Lexington. For more on the Book Festival, see page 33.

The Mountain Workshops help young photojournalists hone their craft while giving “ordinary” people a platform to tell their stories

BY TOM EBLEN

On the third Saturday in October, a rented truck will pull up to the Cox Building in downtown Maysville, where Western Kentucky University students will unload dozens of computers and connect them with thousands of feet of ethernet and fiber networking cable. Tables, chairs and a big screen will be set up, and the historic convention center will be transformed into a temporary workspace—part classroom, part newsroom.

The 50th annual Mountain Workshops will be ready to roll in Mason County.

The workshops started in 1976 as a WKU class project to photograph the last one-room schoolhouses in Kentucky’s mountains. In the halfcentury since, it has become a nationally renowned seminar that trains visual storytellers by having them capture life in a community for a week. To date, the workshops have documented 40 Kentucky counties and five in Tennessee through pictures, words and—since 2007—short films.

“It started out as something we did for our students, but I don’t think we anticipated just how much impact we would have on the industry and the communities we

covered,” said James Kenney, who heads WKU’s visual journalism and photography program and has been the workshop’s director since 2000. “In the process, we have built a halfcentury history of life in Kentucky.”

On Oct. 21, about 70 student and professional photographers from across the country will gather in the transformed Cox Building. They will spend the next four days and nights learning skills from an all-volunteer

Opposite page, Allan “Casey” R. Read takes a nap after spending the day walking around Scottsville, 1986.

staff of 40 professionals that include Pulitzer Prize-winning photographers, Emmy Awardwinning filmmakers and Hall of Fame journalists.

“I’m in awe of it every year,” Kenney said. “I can’t believe what people in the industry give to the workshops because they believe in [them] so much.”

Recruiting world-class instructors has never been hard, said Tim Broekema, a WKU professor who oversees the video workshop. “I coldcall filmmakers who are Oscarnominated and have absolutely nothing to do with Western, and they immediately say, ‘I’ve been wanting to come to Mountain forever!’ ” he said.

The workshops begin at noon on Tuesday, when participants rush to pull a folded slip of paper from a hat during the chaotic opening ceremony. Each slip contains the name and phone number of a local person who has agreed to be a story subject: teachers, merchants, barbers, pastors, farmers, restaurant servers, veterinarians—seemingly ordinary people. But workshop lesson No. 1 is that seemingly ordinary people have fascinating stories if you take the time and effort to discover them.

The participants immediately call their subjects and head out to meet them. Over the next few days, they will become the subjects’ shadows, following them to work, play, meals and family moments big and small.

By the time the workshop ends in the wee hours of the following Sunday morning, video participants, with help from their coaches, will have made short films about their subjects. Photographers, working with both photo and writing coaches, will have told their subjects’ stories in 10 images and a written essay. All of this will be posted online at mountainworkshops.org

Professional filmmakers who are workshop alumni will have created a stunning documentary about Mason County using digital video they shot, as well as clips and images from participants. And a team of photo-editing students and coaches will have sorted through thousands of images to begin

assembling a 124-page book.

While some participants are WKU students, the Mountain Workshops’ fame has attracted students and working professionals from across the United States and as far away as Australia and Denmark. The event has helped make WKU’s photojournalism program one of the nation’s most respected.

WKU’s photojournalism majors are encouraged to begin attending the workshop as freshmen “labbies,” a title that recalls the pre-digital days, when their main job was processing and printing participants’ black-and-white film. Now, the labbies do most of the grunt work— from running errands to setting up all those computers and cables under the direction of a former newspaper photographer who runs an IT company.

“They get back [to campus], and they’re just on fire,” Kenney said of the labbies, who usually return the next year as participants. “They’ve seen what it’s all about.”

Award-winning photojournalists have found their callings at the Mountain Workshops. One is Jonathan Newton, who retired last year after a 24-year career as a staff photographer at the Washington Post and previous stints at newspapers in Tampa, Atlanta and Nashville.

In the spring of 1983, Newton was an unfocused WKU freshman from Louisville. Mike Morse and Jack Corn, two of the photojournalism program’s founding fathers, pulled him aside and told him he should consider another major. “They said I just wasn’t cutting it,” Newton said. “In hindsight, they were exactly right.”

After thinking it over all summer, Newton decided to give

director at the Washington Post. A year later, Elbert hired him.

Leslye Davis found her calling at the workshop a generation later. A Greensburg native, she is now a New York-based filmmaker and writer. As a videographer for The New York Times, she co-produced Father Soldier Son, an award-winning Netflix documentary, in 2020.

“I feel like the Mountain Workshops was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to me,” Davis said. While working with video coach Liz O. Baylen, now a senior audio editor at The New York Times , Davis was inspired to become a documentary filmmaker. “I saw the power of audio and video and letting people tell their own stories,” she said.

Davis has volunteered several years as a video coach. She would be in Maysville this year were she not studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on a prestigious Knight Fellowship.

photojournalism another shot. He came back to Western, attended the workshop in Celina, Tennessee, and drew a great story subject: Bud Garrett, a blues singer who handcrafted flint marbles—then a popular men’s sport in that town of 1,500 people. Newton also received encouragement from his photo coach, Tom Hardin, then photo director at

The Courier-Journal in Louisville.

“It all came together for me at the workshop—I learned how to shoot,” Newton said. “Tom Hardin gave me a ‘lightbulb award’ because he said he saw a light went on in my brain.”

Newton returned for many years after that as a volunteer. At the 1999 workshops in Muhlenberg County, he met coach Joe Elbert, then photo

Communities are changed by the workshops, too. That’s because the process of being story subjects, seeing themselves in photos and videos, or just seeing photojournalists all over town reminds people that their little towns are special.

“We didn’t know what to expect, but it was wonderful,” said Roddy Harrison, the mayor of Williamsburg, site of the 2024 workshops. “It brought the town to life, and it made everybody feel good … It gave them a voice. Any city that gets the opportunity would be crazy not to do this.”

Even with an all-volunteer staff, it costs a lot of money to put on the workshops. Budget cuts have eliminated most university funding. Many participants now pay their own way rather than being sponsored by an employer. As newspapers and magazines shut down or reduce staff, more photographers are becoming freelancers.

Host communities and corporate sponsors provide valuable financial and in-kind support, but organizers have started fundraising for an endowment to keep the workshop going for another half-century.

“The Mountain has always held on to a strong ethical approach,” Broekema said. “In an industry that is constantly under attack for its ethics, that’s still our guiding mandate … to teach young journalists the ethical process of gathering content and telling stories.” Q

For more information on the Mountain Workshops and to contribute to help them continue, visit mountainworkshops.org.

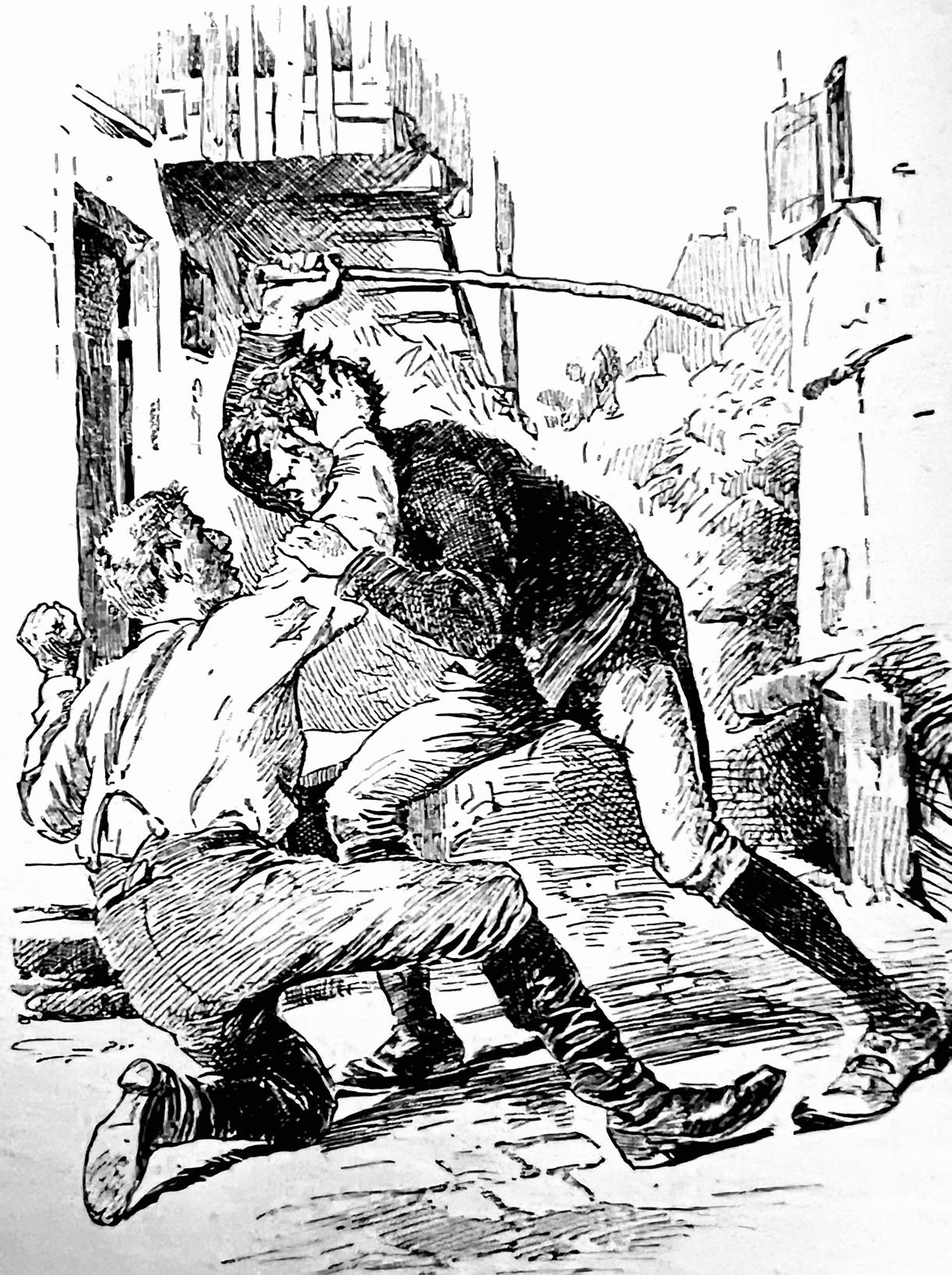

The notorious Harpe Brothers embarked on a bloody odyssey primarily in frontier Kentucky

BY RON SOODALTER

On a brisk day in December 1787, a wellappointed young man named Thomas Langford was breakfasting at an inn near the small settlement of Crab Orchard in Lincoln County when a ragged group of two men and three women appeared. Feeling sorry for the small band, Langford generously bought them breakfast, unwittingly showing a purse of silver coins. Bandits were common on the Wilderness Road, and when the time came to continue his journey, he joined them, for security.

It was the worst decision Langford ever made and his last. Unbeknownst to him, the two men were the notorious Harpe Brothers, and they had come to the inn after robbing and brutally murdering several travelers. Two days after Langford left the inn, two drovers found his body covered with leaves and hidden behind a log.

For years during the late 18th century, the Harpe Brothers ranged unimpeded throughout Kentucky and frontier regions from pre-state Illinois to Louisiana. Notorious as highwaymen and river pirates, they were

most specifically feared as wanton, indiscriminate murderers of men, women and children. So widespread and vicious were their depredations that historians have referred to them as America’s first serial killers.

According to most reliable sources, Micajah “Big” Harpe and Wiley “Little” Harpe were not brothers, but rather first cousins and the sons of Scottish immigrants. Big Harpe was born Joshua Harper, probably in the 1750s; Little Harpe was named William Harper and was about two years younger than his cousin. Arrest warrants and reward notices of the time include fairly detailed physical descriptions of the two, with Big Harpe depicted as a hulking 6-footer “of robust make” with wiry black hair, while Little Harpe was redheaded and, as the moniker suggests, considerably smaller than his cousin but no less psychopathic.

The two had sided with the British during the Revolutionary War and had purportedly fought against the Patriots alongside other Tories at the battles of Cowpens and King’s Mountain. For years after the British

surrendered, the two continued to raid Patriot homesteads, farms and settlements as members of Dragging Canoe’s renegade Chickamauga Cherokee raiding parties.

By this time, the Harpes had kidnapped two young women, both of whom Big Harpe claimed as his “wives.” In a short while, Little Harpe took a woman of his own, and the cousins freely shared their “brides” with each other. Three children were born out of this arrangement, one of whom Big Harpe killed simply for crying while he was trying to sleep. The women accompanied the Harpes on their murderous forays despite the brutal treatment that the men meted out.

There is no accurate account of the number of murders the Harpes committed. Estimates have ranged between 50 and 100. They first achieved notoriety when mangled bodies began to turn up in the wilds. The Harpes’ trademark manner of disposing of their victims was to eviscerate them, fill the body cavities with rocks, and sink them in the nearest stream or river. Since they made no secret of their depredations—often announcing, “We are the Harpes!”—their name spread rapidly through the tiny communities and lone farms on the frontier.

The people who chose to make their way in the wilderness were, of necessity, a hardy lot. Living lives that were, in the words of English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short,” they were accustomed to death in its many forms: disease, fire, freezing, starvation, childbirth loss, and attack by animals, Native tribes and bandits. Writes historian Henry Lincoln Keel, “[N]o Americans had witnessed more death than the backwoods pioneers had.”

In the absence of available law enforcement, those living on the frontier were accustomed to dealing with outlaws decisively. Resilient though they were, the threat of the Harpe Brothers instilled a terror that was unique among the settlements. Observes biographer Wallace Edwards, “In the wake of their wanderings around Kentucky, Tennessee and southern Illinois, [the Harpes] left a trail of dread among frontier families. This was a remarkable accomplishment.” Newspapers were few, and their circulation limited. Widespread rumors and gossip often blew the already-dreadful news out of proportion. Settlers knew, writes Keel, “the evil was out there somewhere and … it might blow over them like a foul wind at any time.”

Finally arrested and confined in the Danville jail, the

Harpes managed to escape, leaving their women and children behind. Freed for lack of evidence, the women were given an old mare by sympathetic citizens. With children in their arms, the Harpe women traded the horse for a boat and rowed down the Ohio River to rejoin their men.

By this time, the Harpes had joined the gang of the notorious river pirate Samuel Mason in his lair at Cave-inRock, a vast cavern situated above a bend in the Ohio River. The gang lured flatboat crews to shore, robbed them and often gave them the option of dying or joining the pirates.

The Harpes brought their own form of mayhem to the pirate lair. They clearly reveled in the act of killing, and they practiced it in ways that shocked even the pirates. On one occasion, they stripped a prisoner, tied him to a horse’s back, and whipped the horse off the cliff above the cave and onto the rocks below. The stunned pirates threw the Harpes out of the gang.

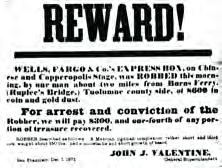

Accompanied by their women and children, the Harpes returned to their old killing grounds in Kentucky, murdering as they went. They left victims in Stockton’s Valley, Russellville, the Kingston area, present-day Montgomery County, the woods around Bowling Green, and on Wolf River near the Kentucky/Tennessee border. By this time, a huge reward had been posted, and “hunting parties” searched for the two without success.

• • •

Then came the act that ended their murder spree. On Aug. 21, 1799, after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate a local justice of the peace, the Harpes sought shelter at the home of Moses Stegall a few miles east of present-day Dixon (Webster County). Stegall, it turned out, was away, and the Harpes convinced his wife, Mary, to feed and house them for the night. They shared the loft with a surveyor who was there to meet with Stegall, and when the man’s snoring disturbed their sleep, the Harpes killed him. The next morning, they slew Mary and her 4-month-old son and burned the house to the ground. Taking two horses from Stegall’s stable, they rode what they considered a safe distance, slaying two local men along the way.

Moses Stegall returned later that day and was informed of the catastrophe. Bent on revenge, he joined a rapidly assembled posse, and—well armed and mounted—they pursued the Harpes to their camp. Wiley managed to escape capture, but Micajah was shot and mortally wounded. As he lay dying, he begged for water, which a posseman brought him. It was the only kindness afforded the killer. Bent on retribution, Stegall cut off Micajah’s head

with his knife to serve as both a trophy and a warning.

Given Stegall’s expressed thirst for vengeance, it is not known if he waited for Micajah to die of his wounds prior to removing his head. However, a macabre piece of folklore describing Harpe’s end has been passed down through generations of Kentuckians. In this iteration, he is still alive as Stegall applies his knife and growls midprocedure, “You are a God-damned rough butcher, but cut on and be damned!”

Harpe’s head was posted at a crossroads in Webster County on what is now known as Harpe’s Head Road, and there it remained for years as a grisly warning to would-be malefactors. Today, a Kentucky Historical Society highway sign marks the spot.

Meanwhile, having escaped capture, Wiley convinced Samuel Mason to take him back, and he soon rose to second in command. By now, Wiley and Sam were the two most wanted men in Mississippi, with Wiley heading the list nationwide.

Now calling himself John Setton, Wiley discovered that a $1,000 reward (worth more than $30,000 today) had been offered for Mason’s capture or death. He and an associate killed the pirate leader, and—presenting his head to the authorities at Natchez—claimed the reward. At some point, Wiley was recognized, and he and his accomplice were summarily tried. They were hanged on Feb. 8, 1804. Locals beheaded the two, and—as with Micajah four years before—posted their heads along the

America’s First Serial Killers: The Bloody Harpe Brothers

April 2025

America’s First Serial Killers: A Biography of the Harpe Brothers

Wallace Edwards

Anaheim, CA, Absolute Crime Press, 2020

roadside as a grisly warning.

After Micajah’s and Wiley’s deaths, their three women were taken to Russellville, tried as accessories to the Harpes’ crimes, and acquitted. Following their release, Wiley’s wife (he had legally married her) went to live with her father and eventually married a respectable citizen. One of Micajah’s “wives” settled in Russellville and, according to one chronicler, “lived a normal life.”

Living under an alias, the other married in 1823 and moved to Illinois. It is not known what became of the two surviving children. In all the time they were with the Harpes, the three women, who clearly suffered terrible abuse, never attempted to escape, even when the opportunity presented itself.

Various historians have attempted to link the Harpes’ murder spree to a bitter disappointment in the outcome of the American Revolution. In fact, as with such modernday serial killers as Ted Bundy and Kentucky’s “Angel of Death” Donald Harvey, their psychopathy calls for no justification at all. The Harpes simply enjoyed killing for the sake of killing. Writes biographer Edwards: “They were indiscriminate murderers dispatching people they came across with complete abandon. Their crimes were for the most part devoid of any detectable motive.”

One thing is certain: With the deaths of the Harpes, settlers throughout the frontier breathed a collective sigh of relief. Q

“The Harpe Brothers”

Karen Hart

Manuscripts and Folklife Archives, Library Special Collections, Western Kentucky University, 1971

Contains wonderful accounts of the Harpes as told through in-depth interviews with several older Kentuckians

Bloody Brothers: America’s First Serial Killers

Henry Lincoln Keel

Lafayette, TN, Deep Read Press, 2021

BY KIM KOBERSMITH

With the scary season approaching, it’s a great time to tour these creepy locales and attend haunted happenings across Kentucky

Some places in Kentucky are perfect for Halloween. They have a high level of paranormal activity, repeated sightings of unexplained figures, or gruesome histories that continue to be told. Many of these locations capitalize on the season with entertaining and sometimes unnerving events that might have you looking back over your shoulder with apprehension.

The forbidding Tudor Gothic structure in Jefferson County is unsettling even from the outside. Peeling paint and broken windows add to its sinister feel.

Completed in 1926, the facility was constructed in response to a severe tuberculosis outbreak in the county. Wetlands along the Ohio River were the perfect breeding ground for the bacteria responsible for the disease. This five-story building held up to 400 advanced pulmonary tuberculosis patients until its closure in 1961, after the antibiotic drug streptomycin drastically reduced the effects of tuberculosis.

For many patients, the sanatorium was their last earthly home. Tales abound of those whose spirits remain: a mysterious man in white who drifts through the corridors, a spectral boy who plays ball in the hallways. After its closure, Waverly Hills gained notoriety as a spot for ghost hunts and paranormal investigations. It is considered one of the world’s most haunted places.

Now on the National Register of Historic Places, the restored structure is open to the public for tours, paranormal evenings and overnight investigations throughout the year. The annual Haunted House event takes visitors to an even more thrilling level.

No reservations are needed for the Haunted House, held every Friday and Saturday through October.

By day, this uniquely shaped home museum in Simpson County is a place to learn antebellum history. But at night, it’s revealed as one of the most haunted places in the South. Stories of ghosts include those of resident family members, enslaved people and soldiers from both sides of the Civil War. Periodic ghost tours take place throughout the year. In October, these hunts will be offered every Friday and Saturday night, with the opportunity to participate in flashlight tours of the mansion during the week.

OCTAGONHALLMUSEUM.COM

Almost everyone who steps into this Johnson County museum has an experience of the unseen world—strange apparitions, “shadow people,” noises and even direct communication with those beyond the veil. The curious can arrange a specialized paranormal tour or get their spooky on at the Haunted Museum, held Fridays and Saturdays in October.

The Shakers were known for their adherence to pacifism, celibacy and honesty. But their intention to create a heavenly paradise on earth didn’t mean they escaped the more macabre realities of life. On Spirit Strolls, held Friday and Saturday evenings in September and October, tour guides recall tales from the darker side of Shaker Village in Mercer County.

Staff reworked the tour last year to add new and violent tales pulled straight from history. A sentence in an archived Shaker journal from 1872, for example, revealed that a probationary community member was arrested for murder. John Gunsawley, a strapping Lexington stonemason, was not pleased to hear that his wife’s family didn’t think well of him. The feud between him and his wife’s sister’s boyfriend reached its peak when Gunsawley’s threats and menacing door-knocking went unanswered. The bullet he shot through a window aimed true, and he spent the next nine months hiding out at Shaker Village under an assumed name.

“We filled out the story through court transcriptions and penitentiary records in the Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, even down to the words he was shouting as he ran down the street after the shooting,” said Becky Soules, the village program and collections director. “It’s not a surprise his time with the Shakers didn’t work out.”

The lantern-lit walk traverses the community’s main thoroughfare and ends in the graveyard. The vibe is gruesome rather than supernatural or spooky, with themes of painful injury and murder. Organizers recommend limiting the tour to those ages 16 and over. Sometimes the spooky history expands beyond one building...

SHAKERVILLAGEKY.ORG

Explore the historic buildings of La Grange. Visitors on a two-hour candlelit walk might meet some of the town’s previous inhabitants—hearing unidentified whispers or seeing the outlines of ghosts. All proceeds support the maintenance and restoration of the historic structures. Tours take place on Fridays and Saturdays in October and are not recommended for children under 12.

LAGRANGEMAINSTREET.ORG/SPIRITSOFLAGRANGE

Step into a spooky carriage for an hour-long ride and haunted tour of downtown and the Lower Town neighborhood of Paducah. Guests will hear stories of a Confederate soldier, a former newspaper owner, child spirits and local mummy legend Speedy. Rides are available during weekends in October.

Maybe events are more your thing—gathering with a crowd and sharing scary and wondrous aspects of the season together. Even better, ones that are uber-local experiences. An all-ages festival or a movie marathon might be just the ticket!

This all-night zombie film fest is set for Nov. 1 at 8 p.m. at the Rohs Opera House in Cynthiana. Visitors will view five films and spend the night in one of the most haunted buildings in Kentucky. Rohs Opera House recently was featured on the Biography Channel’s My Ghost Story. Or visitors can schedule their own paranormal investigation on a Friday or Saturday night to see what transpires.

The Kentucky Folklore Festival in West Point (Hardin County) Oct. 25 explores the Commonwealth’s deep roots in haunted history, magic, mysticism and storytelling. The fest began as a way to honor Leah Smock, a young herbalist and suspected witch from the 1800s who reportedly haunts this area southwest of Louisville. The festival, formerly the Battletown Witch Festival, has expanded its focus this year.

“It includes everything weird, wonderful and spooky across Kentucky, so people from all parts of the state are represented,” said organizer Annie Hamilton with Hearth and Hallows Creative Event Management. “The festival is absolutely family friendly and not about being scared but about having fun.”

Presenters at the fourth annual gathering include Packman Paranormal, the team behind The Hauntings of Fort Duffield. Explorations of the local Civil War-era earthworks have revealed a host of hauntings, which speakers will share with attendees. Also attending is Black Wolf Paranormal, known for its investigations of the legendary Bell Witch Cave in Tennessee.

Gray’s Taproom Podcast will serve up wicked laughs with its paranormal comedy act. Storytellers will weave tales of Kentucky urban legends and historical folklore. Also on tap: a Sasquatch-calling contest and a cryptid creature costume contest.

Hamilton said organizers are well on their way to selling 10,000 tickets for the event. Food trucks, themed handmade artisan booths, and a beer garden will accompany the programming.

The former Blue Heron coal camp in McCreary County usually is a ghost town. Historical plaques and oral histories recall stories of those who called it home in the mine’s heyday.

But in October, the historical site in the Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area plays host to the Blue Heron Ghost Mine. Guests can earn junior ranger badges, watch living history demonstrations, and listen to local tunes before hearing spine-tingling tales from the nearby hills and hollows.

BY JACKIE HOLLENKAMP BENTLEY

When one thinks of pure maple syrup— aside from the delicious image of the drizzled amber liquid cascading down a stack of pancakes—the prevailing assumption is that it’s produced in New England and Canada. But a new University of Kentucky study revealed what a few in the Commonwealth already had discovered: Kentucky has the potential to become a significant maple syrup producer, generating millions of dollars for local economies.

The study estimated that Kentucky could generate from $6-$25 million in

economic impact, not to mention upwards of 1,000 new jobs.

Thomas Ochuodho, associate professor of forest economics and policy in UK’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, said it began in 2019, when he and agents from UK’s Cooperative Extension Service visited with maple syrup producers in Letcher County.

“They took us through some of the challenges that they had, and one of those was basically just lack of information,” Ochuodho said. “So many landowners have maple trees on their lands, [and] they are not even aware this is something they could do.

Those who were aware don’t know how they could do it and … [wanted to know if it was] economically viable and at what scale.”

Ochuodho and fellow researchers from UK, Purdue University and the U.S. Forest Service collected and pored over data on tree density across the Commonwealth, sap yield, the length of Kentucky’s sap-tapping season, and the current price of maple syrup.

With that research, Ochuodho and his colleagues used economic impact models to determine just how much maple syrup production could benefit not only producers but Kentucky’s economy as a whole.

“Producers will purchase equipment … and it creates demand in the supply chain throughout the economy,” he said. “Those producers [then] use that income to make purchases in the economy, etcetera. We are looking at it from the very beginning to the end, where you have maple syrup at your dining table. That is the impact that you are seeing here.”

• • •

John Duvall, the president of the Kentucky Maple Syrup Association (KMSA) and horticulture technician at Eastern Kentucky University’s Department of Agriculture, said the study is a great way to show potential producers exactly how they can use this renewable resource year after year.

“We’re trying to help grow the

commodity, grow the industry here in Kentucky, so having that type of research come out just helps support what we’re doing,” Duvall said. “That’s what our association is all about— getting the word out there. There’re several of us who just found out in the last four or five years that it’s a possibility in Kentucky.”

Duvall said association membership has grown from more than a dozen participants to more than 40 in just two years.

“But there’re still lots of people I keep finding who are making maple syrup. They’re just not members yet,” he said.

For those who want to learn more about tapping into their land’s potential, the association is holding Kentucky Maple Syrup 101 workshops at county Extension

offices across the Commonwealth throughout October.

“If you want to get started, you can go and learn from somebody who has experience,” Duvall said.

For more in-depth education, KMSA is having its annual Kentucky Maple School on Nov. 1 at the Clark County Extension Office in Winchester.

Registration and information for both opportunities can be found on the association’s website, kymaplesyrup.com.

• • •

One of the first things interested landowners will discover is when their maple trees can be tapped. The key is weather: Freezing temperatures overnight pull the sap

Interested in learning more about how to make maple syrup from the trees on your land? The Kentucky Maple Syrup Association will hold beginner workshops at Extension offices across the Commonwealth through October. Attendees can meet maple syrup producers personally and discover the ins and outs of the process.

Here’s a list of workshop times and dates. Participants are asked to contact the local Extension office to register. More information can be found at KMSA’s website, kymaplesyrup.com

OCT 1

6PM Kenton County Ext. Office

OCT 7

6PM Calloway County Ext. Office

6PM Shelby County Ext. Office

OCT 8

6PM Metcalfe County Ext. Office

OCT 15

5PM Breathitt County Ext. Office

OCT 21

6PM Harlan County Ext. Office

6:30PM Madison County Ext. Office

6PM Pulaski County Ext. Office

OCT 23

6PM Henderson County Ext. Office

6PM Bath County Ext. Office

OCT 28

5:30PM Letcher County Ext. Office

OCT 29

9-11AM Nelson County Ext. Office

up the tree via osmotic pressure. Then, as temperatures climb above freezing during the day, the sap flows down to be captured, drawn and collected in either good oldfashioned buckets or a more elaborate piping system connecting multiple trees across the property.

In Kentucky, that optimal season is about six to eight weeks in December and January.

“It depends,” Duvall said. “The colder the better … We try to find which six to eight weeks during the winter you’re going to have the most days in a row” of freezing and thawing.

Once the sap is collected, the next step is to boil it down to evaporate the water content, caramelizing the remaining sugars into the familiar golden-brown syrup. While sugar content varies among trees, typically 43 gallons of sap can be reduced to 1 gallon of syrup, per KMSA.

In addition to KMSA’s education initiatives, the organization collaborates with UK’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources on its comprehensive maple syrup website. The site, ky-maplesyrup.ca.uky.edu, features a list of FAQs, study guides and even budget templates from the

Kentucky Center for Agriculture and Rural Development.

Ochuodho said these guides for landowners and potential producers are tangible tools born from the maple syrup study’s economic impact discoveries.

“Somebody’s producing so much, and he wants to expand his capacity, so what will he need, and how much would that cost him?” Ochuodho said. An individual landowner can look at the guide “on his screen and say, ‘I have how many trees here? OK, so how much do I need to invest here? OK, if I put in this much, I need this, and I need this, and I need this. So, what does that mean in terms of the returns that I can get?’”

For Duvall and those who have already discovered the benefits of maple syrup production, the returns go beyond financial gain.

“Maple syrup has been around for a long time. People just forgot about it, stopped making it around here,” Duvall said. “We’re trying to help bring it back—bring back that art of making maple syrup. I just started in 2020, and once you kind of get bitten by that sugar bug, you just want to keep doing more and more and more.” Q

We at Kentucky Humanities are thrilled to welcome you to the 44th edition of the Kentucky Book Festival! This year promises to be an unforgettable experience, and we can’t wait for you to join us on Saturday, November 1. We encourage you to sit in on one of the many panel discussions or stage conversations, browse the author’s gallery, listen in on a story time, and check out the fun activities for the next generation of readers. But don’t just come out on Saturday—join us for the added excitement throughout the week! There’s so much to see and do, and we want you to be a part of it all.

We are grateful to our partners at Joseph-Beth Booksellers for once again hosting and assisting with planning the festival. Generous contributions from countless individuals and organizations make this festival possible. We owe all our sponsors and partners an enduring thanks. In fact, because of our amazing sponsors, hundreds of children (age 14 and under) will receive vouchers for a free book of their choice at the festival again this year. It’s heartwarming to see the joy on their faces as they pick out their new favorite book.

We also want to express our deepest gratitude to our incredible volunteers. Their dedication and enthusiasm are the heartbeat of this festival, and we couldn’t do it without them. We hope that everyone who attends the Kentucky Book Festival finds an interesting book to enjoy, meets a new favorite author, and leaves enriched with the literary love that is so abundant in our Commonwealth. Looking forward to seeing you there!

Jay McCoy

ON BEHALF OF THE KENTUCKY BOOK FESTIVAL TEAM NOVEMBER 1 9:30AM–3:00PM

Joseph-Beth Booksellers 161 Lexington Green Circle Lexington, KY 40503

Kentucky Humanities will host several events during the week leading up to the Kentucky Book Festival (October 27–31). Additional conversations, discussions, and presentations will take place on various stages at the KBF on Saturday, November 1. On Saturday, authors will sign books on the lower level within Joseph-Beth Booksellers with access via escalator and elevator. Maps will be provided on the day of the festival. The schedule of events and author lineup are subject to change.

STAY UPDATED

For the most up-to-date author lineup and event schedule, follow us here:

CHAIR

Jennifer Cramer, Ph.D. Lexington

VICE CHAIR

Hope Wilden, CPFA Lexington

TREASURER

Jordan Parker Lexington

SECRETARY

Lou Anna Red Corn, JD Lexington

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEMBER

Penelope Peavler Louisville

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEMBER

Andrew Reed Pikeville

Aaron Asbury Ashcamp

Chelsea Brislin, Ph.D. Lexington

Teri Carter Lawrenceburg

Brian Clardy, Ph.D. Murray

Selena Sanderfer Doss, Ph.D. Bowling Green

Benjamin Fitzpatrick, Ph.D. Morehead

Clarence Glover Louisville

Nicholas Hartlep, Ph.D. Berea

Chris Hartman Louisville

Sara Hemingway Owensboro

Eric Jackson, Ph.D. Florence

Philip Lynch Louisville

Lois Mateus Harrodsburg

Keith McCutchen, Ph.D. Frankfort

Tom Owen, Ph.D. Louisville

Libby Parkinson Louisville

Wayne Glover Yates Princeton

Bill Goodman Executive Director

Marianne Stoess Assistant Director/ Editor, Kentucky Humanities

Kay Madrick Development Director

Derek Beaven Program Officer

Zoe Kaylor Grants Administrator

Jay McCoy

Kentucky Book Festival & Center for the Book Director

Joanna Murdock Administrative Assistant

Katerina Stoykova Director of Educational Outreach

Julie Klier Consultant - Event Production/ Logistics Manager

Kentucky Humanities is an independent, nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities in Washington, D.C. Kentucky Humanities is supported by the National Endowment and by private contributions. In addition to producing the Kentucky Book Festival, Kentucky Humanities offers Kentucky Humanities at the Schools programs, sponsors PRIME TIME Family Reading Time®, offers Kentucky Chatauqua® and Speakers Bureau programs, hosts Smithsonian traveling exhibits throughout the state, publishes Kentucky Humanities magazine, serves as the Kentucky affiliate for the Library of Congress Center for the Book, and awards grants for humanities programs. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NEH or Kentucky Humanities board and staff. Learn more at kyhumanities.org.

MON OCTOBER 27 at 7:00 PM

Gather your team and head over to Goodwood at Lexington Green for an evening dedicated to books and the Bluegrass! Test your literary knowledge, compete for exciting prizes, and savor delicious food and great company. It's a night full of good food & good times that you won't want to miss!

Free and open to the public—bring your friends, famil, and fellow book lovers for a fantastic time. See you there!

Goodwood • 200 Lexington Green Circle, Lexington

TUES OCTOBER 28 at 7:00 PM

Join us as we read and discuss the newest novel of the Port William series, titled Marce Catlett: The Force of a Story by prolific novelist, poet, essayist, environmental activist, cultural critic, farmer and Kentucky native Wendell Berry. This event will include readings from the book by Kentucky authors as well as a visual exploration of the beautiful setting of Port William (based upon Port Royal, Kentucky).

Tickets are required with online registration and book pre-order.

Joseph-Beth Booksellers, 161 Lexington Green Circle

Events and authors subject to change. Visit kybookfestival.org for updates, ticket information and schedule of events.

WED OCTOBER 29 at 7:00 PM

Silas House in conversation with Gwenda Bond about his new mystery, Dead Man Blues

Don't miss the chance to hear renowned Kentucky author Silas House read from his thrilling new mystery, Dead Man Blues. We will dive into the world of mystery and intrigue and join in a conversation between best-selling authors Silas House and Gwenda Bond. Nationally known for writing across genres, with a variety of novels from romantic comedies to historical fantasies to young adult adventures, Bond will discuss with the former Kentucky Poet Laureate his foray into writing a mystery as S.D. House. House’s debut historical crime novel is set in a small town on the Kentucky-Tennessee border.

Tickets are required with online registration and book pre-order of Dead Man Blues. Books by both authors will be available for sale at the event.

Joseph-Beth Booksellers, 161 Lexington Green Circle

THU OCTOBER 30

A Way With Words with Martha Barnette & Grant Barrett

Join us at JosephBeth Booksellers for a special event with A Way with Words, the upbeat and lively public radio show and podcast about language, culture and communication. Each week, listeners call in to discuss word origins, slang, regional dialects, grammar and more with co-hosts Martha Barnette (a Louisville native) and Grant Barrett. Since its launch in 1998, the popular show has gained a devoted nationwide audience and is broadcast in 43 states across the U.S. and beyond. At our event, the hosts will share behind-the-scenes stories, answer questions and engage the audience in a lively discussion about the ways language shapes our lives.

FRI OCTOBER 31

Tickets are required with online registration and book pre-order of Friends with Words Books by both authors will be available for sale at the event.

Joseph-Beth Booksellers, 161 Lexington Green Circle

A SPECIAL EVENT COMING SOON! Watch the KBF website and social media for an announcement with more details about a special guest and program.

ALL THESE GHOSTS DEAD MAN BLUES

Silas House is the New York Times bestselling author of novels, nonfiction, plays and poetry. A former Kentucky Poet Laureate and Grammy finalist, House has received the Duggins Prize, Southern Book Prize, E.B. White Award, Lee Smith Award and many others. He teaches at Berea College and at the NaslundMann Graduate School of Creative Writing. A native of Eastern Kentucky, he now lives in Lexington.

SYLVIA AHRENS Out on a Limb

B. ELIZABETH BECK Swan Songs

BILLY PARKS BURTON Turn a Blind Eye

CRYSTAL CAUDILL Written in Secret

LEE COLE Fulfillment

SUSAN COVENTRY Till Taught by Pain

CHRISTINA DOTSON Love You To Death

SHERRIE FLICK I Have Not Considered Consequences

JULIA FLINT

We Were Promised: How an Appalachian Grandmother Fought a Corporate Giant

ANN H. GABHART The Pursuit of Elena Bradford

KRISTEN GENTRY Mama Said

MATT GOLDMAN The Murder Show

CHRISTOPHER J. HELVEY Revolution

JULIE HENSLEY Five Oaks

SILAS HOUSE Dead Man Blues

NANCY JENSEN In Our Midst

WENDY JETT Woman

BOB JOHNSON The Continental Divide

CHRIS MCCLAIN JOHNSON Three Guesses

TONI ANN JOHNSON Light Skin Gone to Waste

SARAH LANDENWICH The Fire Concerto

DWAIN W. LEE Plausible Deception

MADGE MARIL Slipstream

JAMES MARKERT Spider to the Fly

LEE MARTIN The Evening Shades

T.J. MARTINSON Her New Eyes

CATHERINE MCKENZIE No One Was Supposed to Die at this Wedding

JOHN WINN MILLER Rescue Run: Capt. Jake Rogers’ Daring Return to Occupied Europe

ELIZABETH BASS PARMAN Bees in June

STEVEN PENN A Trunk in the Basement

CYNTHIA REEVES The Last Whaler

MARK RIGNEY Vinyl Wonderland

JULIA SEALES A Terribly Nasty Business

BENJAMIN RUE SILLIMAN Exiting the Bluegrass Turnpike

VIRGINIA SMITH Wed and Gone

ALLEGRA SOLOMON There’s Nothing Left for You Here

DAVID STARKEY

The Fairley Brothers in Japan

ERIN CECILIA THOMAS I Watched You from the Ocean Floor

GERALD TONER Christmas in Our Time

NATHAN VANDERFORD & HOLLY BURKE Cancer in Appalachia: A Collection of Youth-Told Stories Volume 2

LAWRENCE WEILL The Metaphysics Shoppe of Wylers Ford

TJ WEST Country Road Romance

MARTHA A BARNETTE Friends with Words: Adventures in Languageland

GRANT BARRETT Perfect English Grammar

MARVIN BARTLETT Spirit of the Bluegrass

JAN BRANDENBURG

The Modern Mountain Cookbook: A Plant-Based Celebration of Appalachia

JENNIFER BRIAN

Classic Cocktail Revival

BRYAN S. BUSH

Samuel One-Armed Berry: Shaker, Teacher, Ruthless Civil War Guerilla

DAVID CHAFFETZ

Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: the Horse and the Rise of Empires

ANGELA CORRELL

Village Life: Discover Tuscan-Inspired Hospitality and Intentional Living

TONY CRUNK Hopkinsville

DEEDEE CUMMINGS How To Dream

ALBERT DEGIACOMO

Awakening To Light. Three Plays

LOUIS S. DELUCA

Old-Time Kentucky Farmsteading Ways and Means From the Journals of Herbert Lee Clark

ELIZABETH DEWOLFE

Alias Agnes: The Notorious Tale of a Gilded Age Spy

ELIAS DORRIN EELLS

Cocktails and Consoles 75 Video Game-Inspired Drinks to Level Up Your Game Night

CHERYL L. ERIKSEN

Greyhound: The Remarkable Story of the Legendary Racehorse Who Inspired a Nation

GERALD FISCHER

Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Kentucky Volume II Legacy of the Irregulars

DENIS FLEMING JR. Thomas Jefferson and the Kentucky Constitution

LAURA GADDIS Mosaic

RAE GARRINGER

To Belong Here: A New Generation of Queer, Trans, and Two-Spirit Appalachian Writers

JACQUELINE

JANE HAMILTON

A Pencil Grows in Kentucky

BOB HILL Out Here

LISA HOFFMAN

STEM SMART

Parenting: A Practical Guide for Nurturing Innovative Thinkers

JANET HOLLOWAY Pathlights

MARTHA S. JONES

The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir

BRIGID KAELIN Lakeside

SONYA LEA

American Bloodlines: Reckoning with Lynch Culture

JOHNISHA LEVI

Number’s Up: Cracking the Code of an American Family

GEORGE ELLA LYON Don’t You Remember? (Revised & Updated)

ELIZA MCGRAW

Astride: Horses, Women, and a Partnership That Shaped America

KEVEN MCQUEEN

The Judge Mulligan Poisoning and Other Historic Lexington Crimes

MARIE MITCHELL

Paranormal Kentucky: An Uncommon Wealth of Close Encounters with Aliens, Ghosts, and Cryptids

CHRISTOPHER NEWMAN

Marion: The Marion Miley Story, 1914-1941

JAMES C. NICHOLSON Racing’s Return from the Brink: The Incredible Comeback of Old Rosebud and American Horse Racing

NANCY O’MALLEY

Kentucky Frontier to Commonwealth: Historical Archaeology at Daniel Boone’s and Hugh McGary’s Stations

LAURA A. PARÉ

See You in August: The Quilts of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival

SUSAN REIGLER

Kentucky Bourbon

SHARON ROGGENKAMP

The Life & Times of Hammerin’ Hank Ward: The Kentucky Park & Highway Commissioner Who Chased Riverfront Loan Sharks, Tangled with Arsonists in the Parks, and Banished Run Down Dump Trucks

GRETCHEN RUBIN

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives

SHAUNNA SCOTT Toward Just Transitions: Visions for Regenerative Communities in Appalachia

MANDI SHEFFEL

The Nature of Pain: Roots, Recovery, and Redemption amid the Opioid Crisis

DAVIS SHOULDERS Queer Communion: Religion in Appalachia

BELINDA SMITH-SULLIVAN Cocktails Southern Style

ELAINE F. WEISS

Spell Freedom: The Underground Schools that Built the Civil Rights Movement

JAMES WELLS

Because: A CIA Coverup and a Son’s Odyssey to Find the Father He Never Knew

JESSICA WHITEHEAD

Driftwood: The Life of Harlan Hubbard

BOB WILLCUTT Gratz Park: The Heart of Historic Lexington

FIONA YOUNG BROWN

Secret Lexington: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure

JOSEPH ANTHONY Playing Fair

DAVID B. CAZDEN New Stars And Constellations (Bainbridge Island Press, 2024)

JOHN COMPTON my husband holds my hand because i may drift away & be lost forever in the vortex of a crowded store

TONY CRUNK

Cosmogony: Night & Time

FRIENDS WITH WORDS: ADVENTURES IN LANGUAGELAND

Martha Barnette is a longtime journalist and co-host for two decades of the popular radio show and podcast A Way with Words. A Louisville native who did graduate work at the University of Kentucky, she has worked as a reporter for The Louisville Times and The Washington Post, and as an editorial writer for The Courier-Journal. She lives in San Diego, California.

RONALD W. DAVIS

The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife: Poems

KATHLEEN DRISKELL Goat-Footed Gods

WESLEY HOUP

Strung Out Along the Endless Branch

SILAS HOUSE All These Ghosts

REBECCA GAYLE HOWELL Erase Genesis

LIBBY FALK JONES Enchanting the Ordinary: Poems & Photographs

DANIEL LASSELL Frame Inside a Frame

DENTON LOVING Feller

ALESSANDRA LYNCH Wish Ave

LIGHT SKIN GONE TO WASTE

Toni Ann Johnson has won the Flannery O’Connor Award, been shortlisted for the Saroyan Prize, and been nominated for an NAACP Image Award. Johnson’s forthcoming linked story collection But Where’s Home? won The University Press of Kentucky’s Screen Door Press Prize and is scheduled for release in February 2026. She is the final judge for the James Baker Hall Foundation Book Award this year.

JOHN W. MCCAULEY Kentucky is My Home: A Journey Into the Life of Jesse Hilton Stuart

CHRISTOPHER MCCURRY The Gospel of God Boy

ROSALIE MOFFETT Making a Living

KEVIN NANCE Smoke

PAT OWEN The Crossroad

JEREMY PADEN how to recognize god’s chosen

MARIANNE PEEL Untamed Arabesque

AMY RICHARDSON Out of Places

ROBERTA SCHULTZ Deep Ends

GOAT-FOOTED GODS

An award-winning poet, essayist and teacher, Kathleen Driskell is the author of five collections of poetry. Her poems and essays have been published in The New Yorker, Southern Review, Appalachian Review and other literary magazines. She is chair of the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing at Spalding University. Driskell currently serves as Kentucky Poet Laureate.

Gretchen Rubin is one of today’s most influential observers of happiness and human nature. She’s the author of many books, including the blockbuster New York Times bestsellers The Four Tendencies and The Happiness Project, selling more than 3.5 million copies worldwide. She hosts the award-winning podcast Happier with Gretchen Rubin, where she explores practical solutions for living a happier life.

CARINE TOPAL Dear Blood, poems

ARTRESS WHITE A Black Doe in the Anthropocene: Poems

CECILIA G WOLOCH Labor: The Testimony of Ted Gall

ALFONSO ZAPATA To Pay for Our Next Breath: Poems

KASSIDY CAROLINE The Shadows We Hide

JAMIE D’AMATO The Good Vampire’s Guide to Blood & Boyfriends

DANI DIAZ Dreamover

KATHERINE ELIZABETH HALE-STRINGFIELD

The Mary Luck Tales: Witch’s Curse

MARIAMA J LOCKINGTON I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm

P. ANASTASIA POE Prophecies: Dream Within a Dream

CARLOTTA A BERRY

There’s A Robot in My Closet

LYNN CELDRÁN

The Tales of Javi Ramirez: Dumplings for Breakfast

JULIA LYNNE COTHRAN Does a Gaggle of Geese Giggle?

DAWN CUSICK

The Astrochimps: America’s First Astronauts

AMANDA DRISCOLL

Under Anna’s Umbrella

TRACEY FELTNER FRANCIS

The Fluffy Brown Pup That Met His New Family

CAROL JUNE FRANKS Sled Ride Down Unrue Street

LATRELL HALCOMB Ouch Mr. Bear

BETHANY HEGEDUS

Batter for the First Day of School

CHRISTINE HERREN

A Light in the Darkness

LYNDSEY HORN

When the Mountains Speak

AMY KAPOOR Into the Blue: A Counting Adventure

RACHEL TAWIL KENYON You Can Sit with Me

JASON LADY

The Pure Shore Club

NATHAN WILL LANDRUM The Specters of Mammoth Cave

RACHEL LOFTSPRING Mila the Maker and the 200 Piece Jigsaw Puzzle

SUSAN MILLS

Oliver, the Outstanding and Original Oviraptor

ELIZABETH MONGAR

A Glowhearts’ Christmas Tale

MIRANDA MONTOYA Petunia Moves Again

SHAWN PRYOR

Taekwondo Academy: New Kid at the Dojang

TAMMI JO REGAN

Be Like Hank

VALERIE M. REYNOLDS

The Twirl of Being a Little Black Girl/The Joys of Being a Little Black Boy (Second Edition)

DAVID RICKERT

Checkups, Shots, and Robots: True Stories Behind How Doctors Treat Us

SANDRA RIPPETOE

Which Bird is the Best: Wise Owl Knows

MISAKO ROCKS Sew Totally Nala (Bounce Back Vol.3)

KAY SAFFARI

Uno, Dos, Tres Means One, Two, Three!

CHUCK SAMBUCHINO Goodnight, Pickleball

MOLLIE P SAWYER

A Kentucky Adventure

STACY SCHILLING

The ABC’s of Wavy and Curly Hair Starring...The Frizz Girls

ALEX SCOTT

Chuckles the Cheese and The Midnight Thief: A Cheesy Tale of Sneaky Snacks

ANDREW SHAFFER Literary Cats Coloring Book

JENNIFER SOMMER Every Creature Eats

GIN NOON SPAULDING ERRNT

SAM SUBITY Valor Wings

ROBYN WALL I Worked Hard on That!

ALEX WILLAN Mermaids are the Worst!

TAYLOR WOOLLEY Earth Rover

JESSICA YOUNG Today at School with Yesterday and Tomorrow

2025 IMAGE ARTIST K. NICOLE WILSON

K. Nicole Wilson dwells in art, possibility and Lexington. Originally from Maysville, she’s Limestone filtered, over 100 proof and often rye. K. Nicole completed most of her undergraduate work at the University of Kentucky and later earned an MFA in poetry in Cardinal country.

Each year, the Kentucky Center for the Book, a part of Kentucky Humanities, selects two books to represent Kentucky as part of the Library of Congress’ Roadmap to Reading during the National Book Festival. This year, the center chose Alix E. Harrow’s Starling House as the Adult selection and Amanda Driscoll’s Under Anna’s Umbrella ad the Young Readers selection.

Alix E. Harrow is the bestselling author of The Ten Thousand Doors of January, The Once and Future Witches and Starling House. Her work has won a Hugo and a British Fantasy Award and been shortlisted for the Nebula, Southern Book Prize and Goodreads Choice awards. She’s from Kentucky but now lives in Charlottesville, Virginia, with her husband and their two semi-feral kids.

UNDER ANNA’S UMBRELLA

Amanda Driscoll’s newest picture book, Under Anna’s Umbrella, is her most personal and heartfelt story to date. She is also the author and illustrator of Duncan the Story Dragon and Little Grump Truck. Born and raised in Louisville, Amanda lives in Fisherville with her bunny, who thinks he’s a dog; her dog, who thinks he’s a human; and her husband, who thinks he’s a comedian.

The 1901 Kentucky Derby was the 27th running of the Kentucky Derby. The race took place on April 29, 1901.

Volume 40, Number 8 – October 2025 All About Kentucky

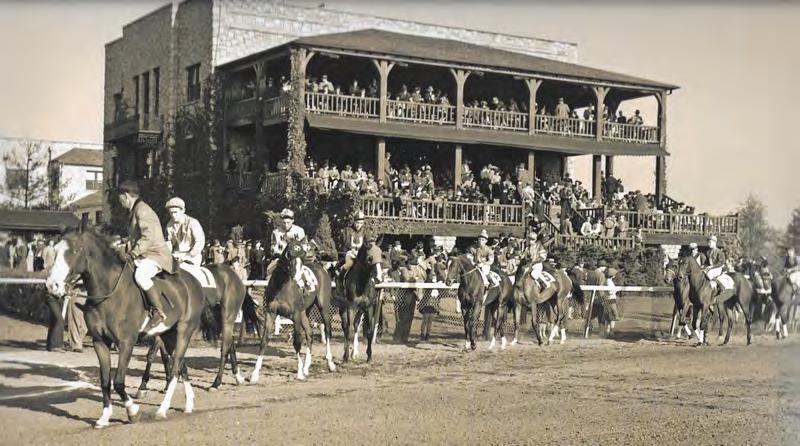

With a few exceptions, Keeneland Race Course in Lexington has hosted live race meets in April and October since 1936. This 1940 photo shows a post parade in front of the Keeneland Clubhouse. The stunning limestone buildings have evolved and been expanded over the years from this original version to the completion of the new paddock building this year.

This year’s fall meet runs Oct. 3-25.

Kentucky Log Cabins – page 45

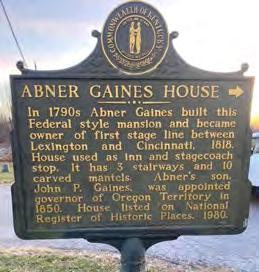

The Inn at Gaines Crossroads – page 48

Sweet Sorghum – page 60

One-Year Subscription to Kentucky Monthly: $25

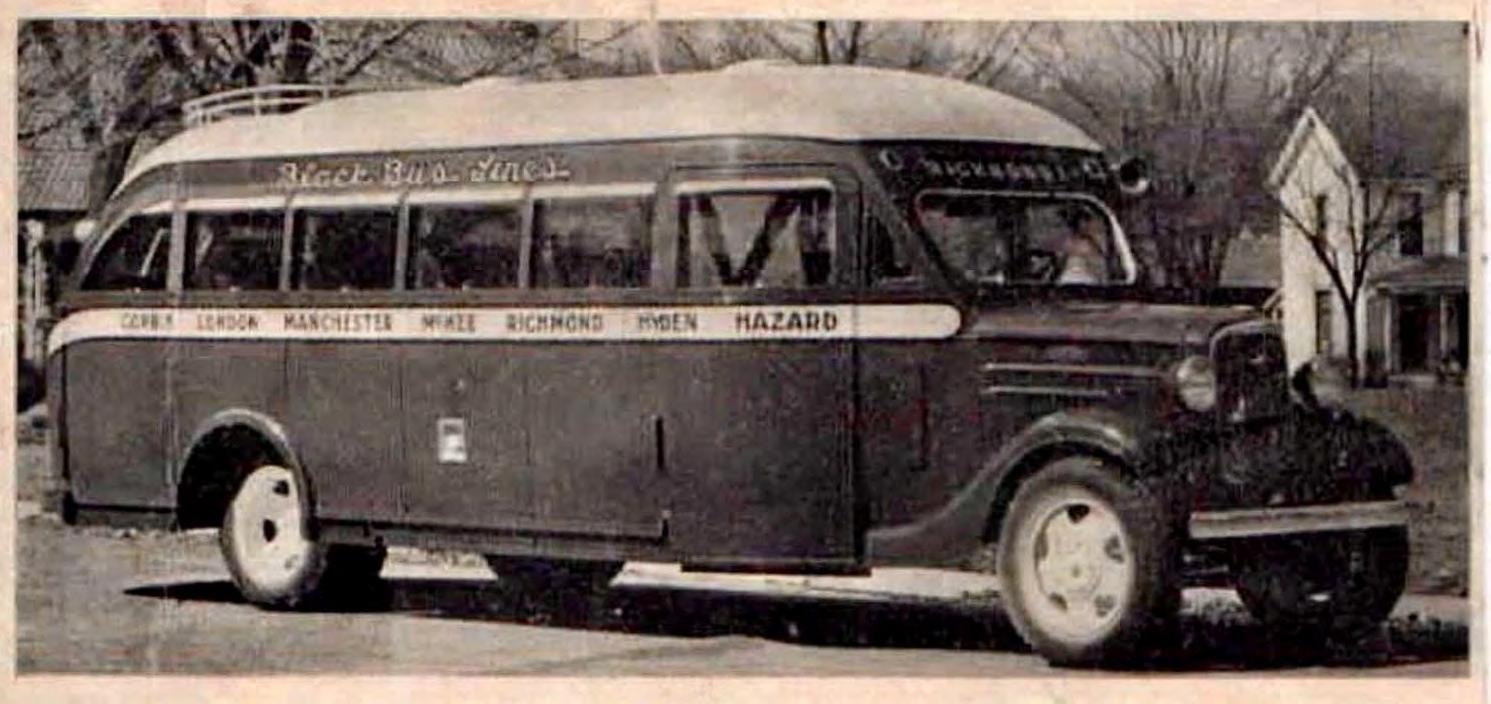

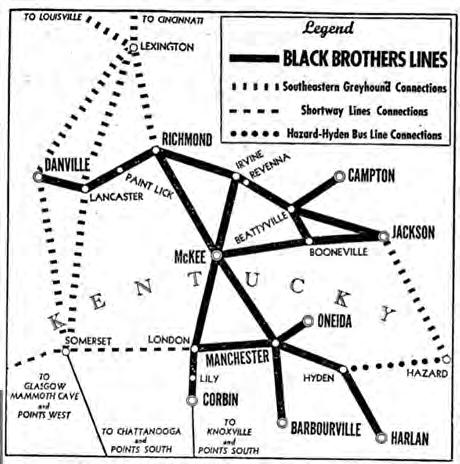

In1926, O.H. Black began a bus line that ran between London and Corbin, a distance of 14 miles. He owned Studebaker-style buses that had doors on both sides. Over the next few years, the line was successful, and his brothers, W.D.—known as Don—and Ramon, joined the company. They changed the name to Black Brothers Lines, expanded to more routes, and made their headquarters on Second Street in Richmond. By the 1940s, the brothers had a fleet of 30 buses, employed 50, and their buses traveled more than 1 million miles per year. The line opened up transportation among cities in Southeastern Kentucky, where transportation options were few.

Do you have memories of traveling via Black Brothers Lines? If so, share with our readers! Email Deb@ Kentuckymonthly.com or send by mail to P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602.

By Mark Mattmiller, Cynthiana

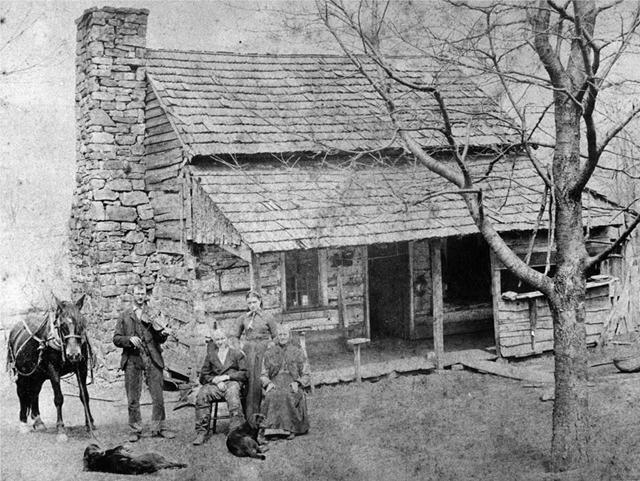

The earliest Kentucky settlers did not just plop down at the first place they came to. There were two things they absolutely had to have. The first was some kind of shelter, and the second was a source of water. The earliest houses almost always were built along the banks of rivers or creeks.

Another factor that often played into the settlers’ choice of location was making sure that they settled far enough away from other people to ensure there would always be the land that they needed for their own use.

The first houses were more shelters than what we would call a house today. Small poles with the bark removed were fitted and stacked together to make one square room. The poles were then chinked with clay. The result was a big improvement over the opened-faced lean-to in which they first sheltered. A fireplace was made from rocks somewhat skillfully fitted together, and the chimneys were made of even smaller pieces of stone. These structures were vulnerable to collapse from the elements of nature and, of course, fire. Few, if any, still stand in their original form today.