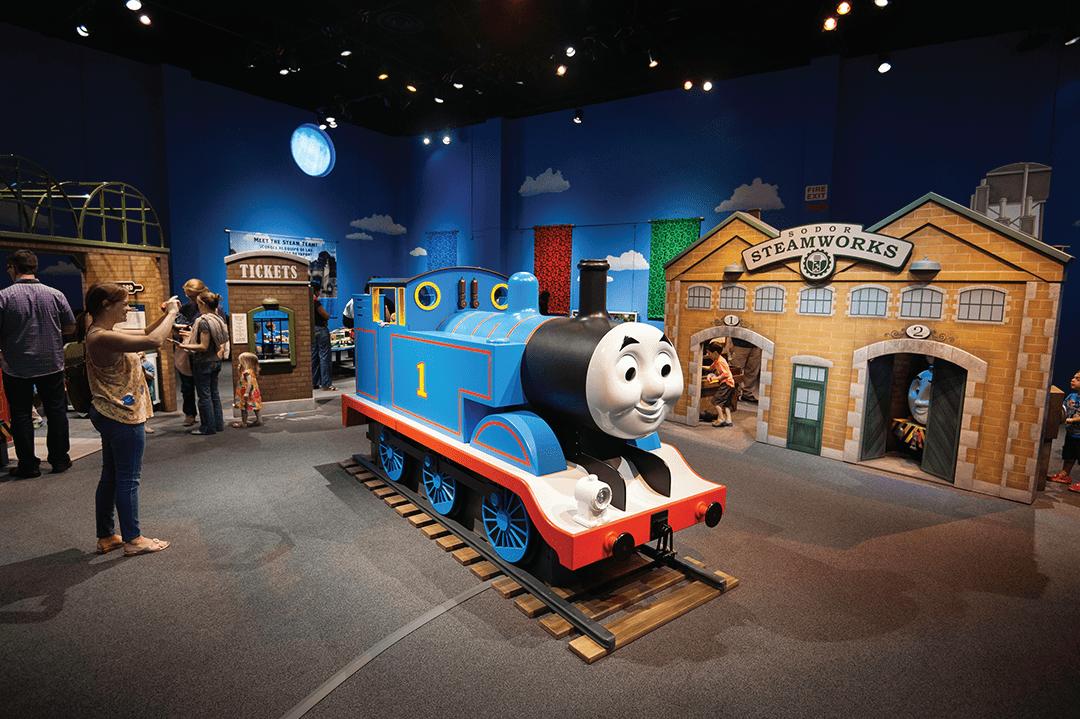

with Kentucky Explorer

with Kentucky Explorer

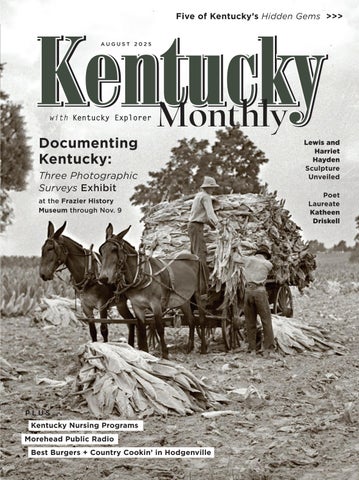

at the Frazier History Museum through Nov. 9 Three Photographic Surveys Exhibit

Loading cut tobacco to take to the barn, Fayette County, 1940. Marion Post Wolcott photo from Documenting Kentucky: Three Photographic Surveys.

14 Moments in History

A photographic exhibit displays scenes from the lives of everyday Kentuckians over more than 80 years

20 Towards Freedom A new Lexington monument honors Lewis and Harriet Hayden, who escaped slavery and returned to the U.S. to serve as conductors on the Underground Railroad

26 Access to the Sacred Kentucky’s new poet laureate aims to promote the virtues of creativity and connect the Commonwealth’s current and emerging artists

28 Off the Beaten Path Visit these hidden-gem Kentucky towns

34 Care, Compassion and Competence Kentucky’s 121 nursing programs train students to make a difference in the lives of their patients

38 Connecting With the Community For 60 years, Morehead State University’s WMKY-FM has served listeners in Eastern Kentucky

42 Food Fixtures Three Hodgenville eateries offer classic country cooking

Test your knowledge of our beloved Commonwealth. To find out how you fared, see page 4.

1. The Battle of Richmond, which took place Aug. 29-30, 1862, was considered a solid Confederate victory. Of the major players in the battle, who was born and raised in Kentucky?

A. Confederate Gen.

Edmund Kirby Smith

B. Union Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson

C. Brig. Gen. Stand Watie

2. Grammy Award-winning country music singer-songwriter Chris Stapleton graduated from Johnson Central High School in Paintsville. A football player, he was noted with which honor at graduation?

A. Most Likely to Succeed

B. Class Clown

C. Valedictorian

3. The 260-mile Kentucky River is formed by the confluence of the North, Middle and South Forks near Beattyville in Lee County and empties into the Ohio River at which city?

A. Warsaw

B. Carrollton

C. Milton

4. Beattyville resident Malcolm MacGregor “Mac” Kilduff Jr. (1927-2003) was the acting press secretary who announced the death of which dignitary?

A. Civil rights leader

Martin Luther King

B. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy

C. President John F. Kennedy

5. Owsley County native Earle Combs was the leadoff hitter on what legendary baseball team?

A. “The Hitless Wonders,” the 1906 Chicago White Sox, who shocked the 116-game-winning crosstown Cubs in the World Series

B. The 1919 “Black Sox,” whose players included eight who were found to have thrown the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds

C. The 1927 New York Yankees, led by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, which for decades was regarded as the greatest team of all time

6. Lindsey Wilson University in Columbia originally was a feeder school for which Southeastern Conference school?

A. Vanderbilt University

B. Auburn University

C. Georgia Tech

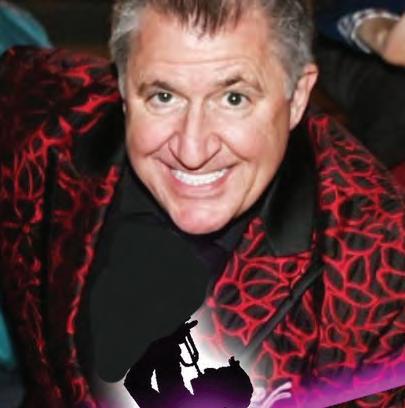

7. Randy Brooks—a nephew of the Lovable Lush, Louisville-born Foster Brooks—wrote which popular Christmas song?

A. “Now Christmas Is Going to Stink for Me”

B. “Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer”

C. “Rudolph the Redneck Cowboy”

8. It’s ironic that Kennedy Center honoree Irene Dunne is remembered for her part in Showboat (1936) because her father, Joseph, worked in which field?

A. Vaudeville performer

B. Steamboat captain and engineer

C. Lockmaster

9. Once an administrator at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Grady Nutt was best known for his three-year stint on which popular television show?

A. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour

B. The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson

C. Hee Haw

10. Famous madam Belle Brezing’s first “disorderly house” was once the home of whom?

A. Elizabeth Shatner (the wife of William Shatner)

B. Laura Bell Bundy

C. Mary Todd Lincoln

© 2025, VESTED INTEREST PUBLICATIONS

VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT, ISSUE 6, AUGUST 2025

Stephen M. Vest Publisher + Editor-in-Chief

Patricia Ranft Associate Editor

Rebecca Redding Creative Director

Deborah Kohl Kremer Assistant Editor

Ted Sloan Contributing Editor

Cait A. Smith Copy Editor

Jackie Hollenkamp Bentley, Jack Brammer, Bill Ellis, Steve Flairty, Gary Garth, Jessie Hendrix-Inman, Mick Jeffries, Kim Kobersmith, Brigitte Prather, Walt Reichert, Tracey Teo, Janine Washle and Gary P. West

AND CIRCULATION

Barbara Kay Vest Business Manager

Katherine King Circulation Assistant

Lindsey Collins Senior Account Executive and Coordinator

Kelley Burchell Account Executive

Kristina Dahl Account Executive

Hal Moss Account Executive

Laura Ray Account Executive

Teresa Revlett Account Executive

For advertising information, call 888.329.0053 or 502.227.0053

KENTUCKY MONTHLY (ISSN 1542-0507) is published 10 times per year (monthly with combined December/ January and June/July issues) for $25 per year by Vested Interest Publications, Inc., 100 Consumer Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601. Periodicals Postage Paid at Frankfort, KY and at additional mailing offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to KENTUCKY MONTHLY, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602-0559. Vested Interest Publications: Stephen M. Vest, president; Patricia Ranft, vice president; Barbara Kay Vest, secretary/treasurer. Board of directors: James W. Adams Jr., Dr. Gene Burch, Gregory N. Carnes, Barbara and Pete Chiericozzi, Kellee Dicks, Maj. Jack E. Dixon, Mary and Michael Embry, Judy M. Harris, Jan and John Higginbotham, Frank Martin, Bill Noel, Walter B. Norris, Kasia Pater, Dr. Mary Jo Ratliff, Randy and Rebecca Sandell, Kendall Carr Shelton and Ted M. Sloan.

Kentucky Monthly invites queries but accepts no responsibility for unsolicited material; submissions will not be returned.

KENTUCKYMONTHLY.COM

Thank you for your recent, article about Renfro Valley (March issue, page 36). One of my several talented aunts apparently performed there, circa 1943-44, as documented by the image above.

The stars of that performance were, from left, Lexingtonians Dora Lee Robertson, Larry Snedekar (partially visible, playing the accordion), Loralie Dearinger (later Howe, my aunt), Beulah McDonald and Juanita Robertson. According to my aunt’s annotation, the people in the background were part of the Renfro Valley Barn Dance Troupe, and the performance was

staged as part of the war effort for the U.S.O.

For me, it is a bittersweet image of a time when our nation was united—a time that, I fear, will not come again.

Dr. David B. Dearinger, Richmond, Virginia

All issues of Kentucky Monthly are a joy to read, but the June/July 2025 issue blew us away with the wonderful historical articles and insightful content.

Steve Vest’s “Collected Family” article for Vested Interest (page 64) was particularly touching to commemorate Father’s Day.

We had the pleasure of meeting Steve and Kay Vest a couple of years ago at a reception in downtown Louisville and were able to tour the Sons

of the American Revolution library. Every issue is greatly anticipated and never disappoints.

Thank you and your staff for such a wonderful publication.

Dave and Debbie Roberson, Nashville, Tennessee

I just finished reading Steve Vest’s recent Vested Interest, “Collected Family.” Love it! The article says so much about him. After fighting two bouts of breast cancer, I know we don’t have a guaranteed tomorrow. I live every day to make sure those I love will always know how much I cherish them. My goal is to leave a legacy of love for my “family” and to people I come in contact with.

Thank you for telling us about your “family.”

Sandy Ramsey, Pikeville

We Love to Hear from You! Kentucky Monthly welcomes letters from all readers. Email us your comments at editor@kentuckymonthly.com, send a letter through our website at kentuckymonthly.com, or message us on Facebook. Letters may be edited for clarification and brevity.

Even when you’re far away, you can take the spirit of your Kentucky home with you. And when you do, we want to see it!

Nancy Gall-Clayton and her husband Jan C. Morris, who live in Jeffersonville, Indiana, are pictured vacationing in Iceland.

The James and Janet McClain family of Madisonville visited iconic Windsor Castle. From left, James McClain, daughter-in-law Rhea Ashby, grandson Paul Ashby, Janet McClain, granddaughter Elizabeth Ashby and oldest son Joey Ashby

Louisville residents Nancy and Craig Schroeder traveled on a European river cruise from Amsterdam to Budapest. They are pictured with cruise friends Helen, Barbara, Denise and Don in Budapest.

KWIZ ANSWERS 1. B. Nelson was born in Maysville and murdered in Louisville; 2. C. Stapleton was top of his class and originally went to Nashville to study engineering at Vanderbilt; 3. B. Carrollton is known as the town “where rivers and people meet”; 4. C. Kilduff was in Dallas with JFK; 5. C. Combs hit a career-high .356 and led the majors with 23 triples in 1927; 6. A. Vanderbilt from 1904-1914; 7. B. Sung by Lexington native Elmo Shropshire (known as Dr. Elmo), the song was inspired by a “tipsy” member of the Brooks family; 8. B. He was captain of a steamboat much like The Cotton Palace that Irene’s family owns in the musical; 9. C. Nutt joined the regular cast in 1979, where he improvised most, if not all, of his lines; 10. C. Oddly enough, it was the home of Abraham Lincoln’s First Lady.

Arts Change Lives.” That’s the message on one of Kentucky’s newest specialty license plates.

The plate is sponsored by Kentuckians for the Arts, the Commonwealth’s arts advocacy and education organization. Funds raised through the purchase of the plate will be used to further KFTA’s mission of informing and educating about the impact and value of the arts.

The arts also are key to a thriving economy. Kentucky’s creative sector, encompassing arts of all disciplines, is a $6.9 billion industry representing 2.5 percent of the state’s GDP. The total compensation for the more than 51,000 jobs in the sector is more than $3.3 billion and represents 2.4 percent of the state’s workforce.

“The arts are vital to Kentucky’s heritage, economy and community life,” said Lori Meadows, chair of the KFTA board. “Our organization is made up of arts supporters from across the state who want to show their passion for the arts and help get the message out that the arts benefit Kentuckians in many ways.”

Arts strengthen communities socially, educationally and economically and are vital to many sectors of the Commonwealth, Meadows noted. “Participation in the arts contributes to greater social engagement, reducing isolation and strengthening mental health and well-being. The arts are critical to a well-rounded education, and academic performance is improved by involvement in the arts.”

In addition, the arts drive tourism across Kentucky, with arts travelers staying longer and spending more to seek out authentic cultural experiences.

Policies and funding that are supportive of the arts are necessary to maintain and grow Kentucky’s creative economy, Meadows added.

So far, more than 1,200 Kentuckians display the new license plate. “We hope Kentuckians in every county will see these plates on the road as a reminder that the arts benefit us all,” Meadows said.

Those wanting to demonstrate their support for the arts can purchase a plate at Drive.Ky.Gov or at their local County Clerk’s office.

For more information about Kentuckians for the Arts, visit kyforthearts.org

Brothers Wright Distilling Co. announced its acquisition of Dueling Barrels Brewery & Distillery, Pearse’s Place restaurant, welcome center and tasting room in downtown Pikeville. This marks a large expansion and investment for Brothers Wright Distilling in the region’s economy and the state’s already rich distilling industry. The 30,000-plus-squarefoot facility previously was owned and operated

by Alltech’s Lyons Brewing & Distilling Co.

“This acquisition represents more than just an expansion of our operations—it’s a deepening of our investment in Pikeville, Pike County, and the future of Eastern Kentucky,” said Shannon Wright, co-founder of Brothers Wright Distilling Co.

Dueling Barrels originally was envisioned by the late Dr. Pearse Lyons and his wife, Deirdre, co-founders of Alltech, who saw the Appalachian region’s landscape, people and rich traditions as reminiscent of their Irish heritage.

“We are honored to carry forward the vision the Lyons family brought to life in Pikeville,” said Kendall Wright, co-founder of Brothers Wright Distilling Co. “Dueling Barrels has become a symbol of pride for the community, and we’re excited to build on that legacy—infusing new energy and experiences while preserving the spirit and story that make this place so special.”

BY LAURA YOUNKIN

Taylor Hughes has a lot going on. A country music artist and songwriter living in Nashville, she’s a Lexington native who has nurtured her musical career in Music City for 12 years. Now, she is nurturing her newborn daughter, Kennedy, who came into the world July 1. Hughes hopes her daughter inherits her musical talent.

“I came out of the womb singing,” Hughes said. She also was an athletic girl, and volleyball was her joy. While in high school, she planned to attend college on a volleyball scholarship. Unfortunately, a severe knee injury her junior year ended that dream.

When Hughes asked her parents for guitar lessons, they thought learning guitar was a great idea. What they didn’t realize was how talented she was. After a handful of lessons, her guitar teacher invited her to sing in Nashville on the Comcast TV show Nashville Spotlight, a local broadcast produced quarterly at the Nashville Palace. She was so well-received at her debut that she became a regular.

Hughes’ parents were surprised. “They asked, ‘Was that actually you singing?’ ” she said. Hughes had a new dream—music.

“I started playing bars and venues around Lexington as soon as I was old enough to get in them,” Hughes said. She met her future husband, Drew Noble, in Lexington. The two married in 2017 and moved to Nashville.

“I was born, raised and lived [in Lexington] for 25 years before we moved to Nashville,” she said. “I’m very much to my core a Kentuckian.”

In case anyone questions her credentials, “Basketball is my

religion,” she said.

Kentucky musicians have influenced Hughes’ music, with one of her biggest influences being Johnson County native Chris Stapleton. She admires how he blends soul and country. Hughes also likes Ashlandborn Wynonna Judd and her bluesy, gutsy country sound. “The Judds influenced a lot of women in music,” she said.

“I love Carly Pearce. I’m a huge fan … She’s so vulnerable,” Hughes said of the Taylor Mill artist. Hughes appreciates Pearce’s openness about her emotional states in her songs.

“Country music is a boys’ club, but my voice is a lot deeper than a lot of women,” Hughes said, and she thinks that has opened some doors for her.

“I’ve been asked on a regular basis if I was a singer in a rock band.” She wasn’t. “I’ve always been country. My husband says I’m the blues.”

Hughes blends country, blues and country-fried rock in her sound. The Tennessee Star Magazine called her “country music’s answer to Adele.”

“I never try to sound like anybody. I think that’s cool about what I bring

to the table,” she said.

Hughes said it took her a while to find her niche in Nashville, but “I’ve got a good group of girls—and guys— that I write with,” she said. “I absolutely love being here. There’s music 24/7. It’s cool being here because it’s opened my eyes to all parts of the music business.”

Hughes’ schedule has meant touring on the weekends and songwriting in Nashville during the week. “My favorite part of what I do is performing,” she said.

Hughes loves meeting fans and feeling the energy of live shows. She tries to play as many shows that support veterans and the military as possible. “I have several family members who have served,” she said.

Hughes has won Lexington Music Awards such as Country Artist of the Year in 2023 and Female Vocalist of the Year and Song of the Year for “Jesus and Jail” in 2024.

The Josie Awards, which are for the independent music industry, deemed her Multi-Genre Vocalist of the Year in 2023 and Southern Rock/ Country Rock Female Vocalist of the Year in 2024. Hughes is a nominee for three more Josies this year.

Even as she enters a new phase of her life—motherhood—Hughes plans to continue her music career. “I have no plans of stopping,” she said.” This is what I live and breathe and eat. I can’t imagine not doing it.

“I want my daughter to grow up and see her mom chase her dreams.”

For more information on Taylor Hughes, go to taylorhughesmusic.com. You can also find her on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Steeped in tradition, The Trustees’ Table at Shaker Villag e in Harrodsburg has been “making you kindly welcome” since 1968. Today, Executive Chef Amber Hokams and Farm Manager H.P. Lovelace collaborate to bring the freshest food to guests every season. The menu recently was reimagined with a return to family-style dining. Each day brings a rotating selection of straight-from-the-garden side dishes that are shared around the table. Mainstays such as Mrs. Kremer’s fried chicken, country catfish and a 12-ounce hog chop leave diners satisfied, but you should save room for a slice of the famous Shaker lemon pie.

1 cup heavy cream

1 vanilla bean, pod scraped

3 egg yolks

¼ cup granulated sugar

2 teaspoons Maker’s Mark bourbon

1/8 teaspoon salt

Granulated sugar

1. Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

2. Over medium heat, simmer cream and vanilla bean in a saucepan.

3. In a bowl, whisk together egg yolks, bourbon and salt. Slowly whisk cream mixture into egg mixture and mix until combined.

4. Fill ramekins with mixture almost to the top and place ramekins in a deep-sided baking pan. Pour hot water around ramekins until water is halfway up the side of the ramekins.

5. Bake until the mixture has set, about 30 minutes.

6. Remove ramekins from the baking pan and transfer to a cooling rack. When cool, transfer ramekins to the refrigerator and chill overnight or 4-5 hours.

7. To serve, sprinkle a thin layer of granulated sugar on tops of ramekins. Using a kitchen torch, caramelize the sugar until it’s brown and will achieve the signature snap of a crème brûlée when tapped with a spoon.

Trained at Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Austin, Texas, Chef Amber has led the culinary team at Shaker Village since 2018. Using the bounty delivered from the farm and the certified-organic Shaker Garden, her menus highlight seasonal produce, allowing for a unique dining experience each time you pull up a chair at The Trustees’ Table.

Recipes and photos courtesy of Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill.

¼ pound butter

¼ cup bacon grease

1 sweet onion, thinly sliced

2 tablespoons garlic, minced

2 tablespoons ancho chile powder

5 pounds lacinato kale, stems removed, washed and spun dry

2 quarts homemade chicken stock

½ cup apple cider vinegar

½ cup light brown sugar

1. Melt butter and bacon grease over medium heat in a large pot. Sauté onions until golden.

2. Add garlic and ancho chile powder. Cook until garlic is fragrant, about 30 seconds.

3. Add remaining ingredients to pot. Cover with a lid until chicken stock comes to a boil, then turn heat to medium-low.

4. Allow to simmer until kale is tender.

YIELDS 10-12 CAKES

2 eggs

1 cup buttermilk

¼ cup water

¼ cup butter, melted

2 ears corn, roasted and removed from cob

2 tablespoons scallions, thinly sliced

1 cup flour

1 cup cornmeal

1½ teaspoons baking powder

¼ cup sugar

2 teaspoons salt

1 teaspoon smoked paprika

1 teaspoon garlic powder

Butter to cook

Basil-Lime Crema, recipe follows

Sauteed okra, tomatoes and zucchini

1. In a large bowl, whisk together eggs, buttermilk, water, melted butter, corn and scallions.

2. In a separate bowl, combine flour, cornmeal, baking powder, sugar, salt, paprika and garlic powder.

3. With a spatula, gently fold dry mixture into wet mixture.

4. Heat a large sauté pan or griddle over medium-high heat. Add butter, using a trigger scoop, and add johnny cakes to the pan.

5. Cook 2-3 minutes per side.

6. Finish with basil-lime crema and sauteed okra, tomatoes and zucchini.

BASIL-LIME CREMA

½ cup fresh basil, picked and roughly chopped

1 tablespoon lime juice

1 cup sour cream

¼ teaspoon ground cayenne pepper

¼ teaspoon kosher salt

¼ teaspoon black pepper

¼ teaspoon garlic, minced

Add all ingredients to a food processor and blend to combine well.

½ cup champagne vinegar

¾ cup Shaker Village honey

½ cup lemon juice, freshly squeezed

1 cup avocado oil

1 teaspoon kosher salt

1 teaspoon whole grain mustard

2 teaspoons poppy seeds

2 cups local spring salad mix

Sliced strawberries, blackberries, crumbled goat cheese and candied pecans to finish

1. Add first six ingredients to a blender and blend well to combine.

2. Add poppy seeds.

3. Add local spring mix to a large bowl, pour ¼ cup dressing over lettuce, and toss to combine.

4. Finish with strawberries, blackberries, crumbled goat cheese and candied pecans.

plan your trip

The Trustees’ Table

Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill

3501 Lexington Road, Harrodsburg

To view The Trustees’ Table menu and make a reservation, visit shakervillageky.org or call 859.734.5411.

¼ cup salted butter

8 ears of corn, roasted and removed from the cob

2 cups garden cherry tomatoes, halved

2 cups garden bell pepper, diced

1 cup fava beans (can substitute lima beans if fava beans are unavailable)

2 tablespoons fresh garlic, minced

¼ cup fresh basil, chiffonade

¼ cup green onions, thinly sliced

2 limes, zested and juiced

Salt and pepper, to taste

1. Over medium heat, add butter to a large sauté pan. Once butter has melted, add corn, cherry tomatoes and bell peppers. Sauté until peppers are tender.

2. Add fava beans and garlic. Sauté until fava beans are warmed.

3. Finish with basil, green onions and lime zest and juice.

4. Season with salt and pepper to your liking.

“Life isn’t a matter of milestones but moments.” Rose Kennedy

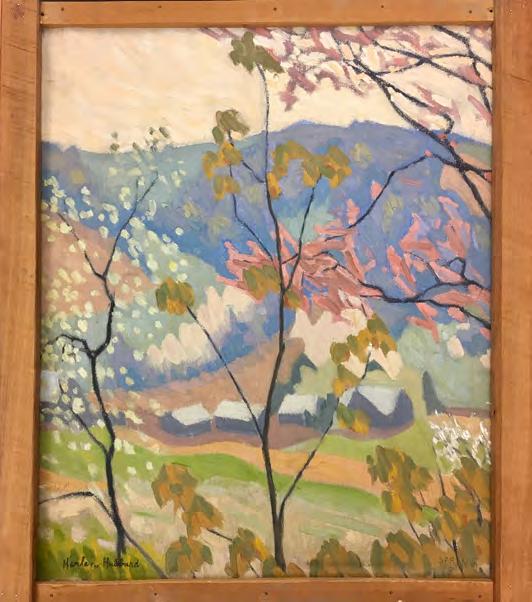

A photographic exhibit displays scenes from the lives of everyday Kentuckians over more than 80 years

BY JACKIE HOLLENKAMP BENTLEY

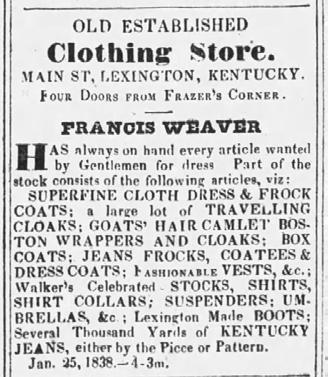

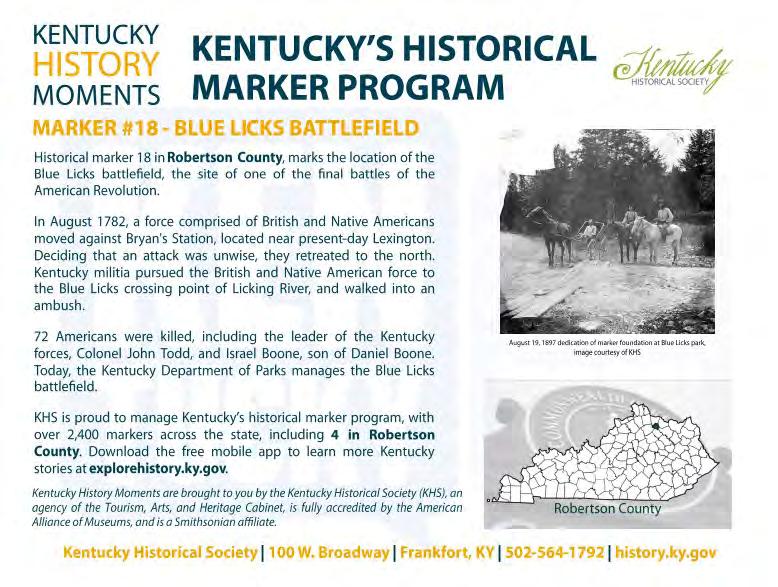

Across 2,000 square feet on the third floor of the Frazier History Museum in Louisville, roughly 150 photographs capture moments from three different eras in Kentucky that span nearly 100 years.

In one moment, it’s 1940 at the Shelby County Fair dirt track, where a dapper young man sporting wingtip shoes and a snazzy hat judges the health of a row of plump babies sitting comfortably in the laps of their well-dressed mamas.

Fast forward 76 years to the 2016 Shelby County Fair. Little Miss and Little Mister Shelby County sit next to the dirt track. He’s sporting shorts, flip-flops and an oversized crown. She is pretty in pink with a sparkling tiara.

Another moment portrays a couple getting baptized in a Morehead creek during the Great Depression. Roughly 80 years after that, a Leslie County woman rises from her baptismal submersion in a Hyden lake.

Standing alone in a 1977 moment is a young man using a payphone, his wife and baby hugged to his side.

•

All of these can be seen at the Frazier’s latest exhibit, Documenting Kentucky: Three Photographic Surveys, open through Nov. 9. “It’s so valuable for us to have here at the Frazier,” said Amanda Briede, the senior curator of exhibitions. “Not only does [the exhibit] represent all of Kentucky’s counties, it also shows the history of Kentucky and being able to visually see that history from all over the state. It’s really showing such a breadth of time and space and really what Kentucky is, and it’s such a beautiful exhibition.”

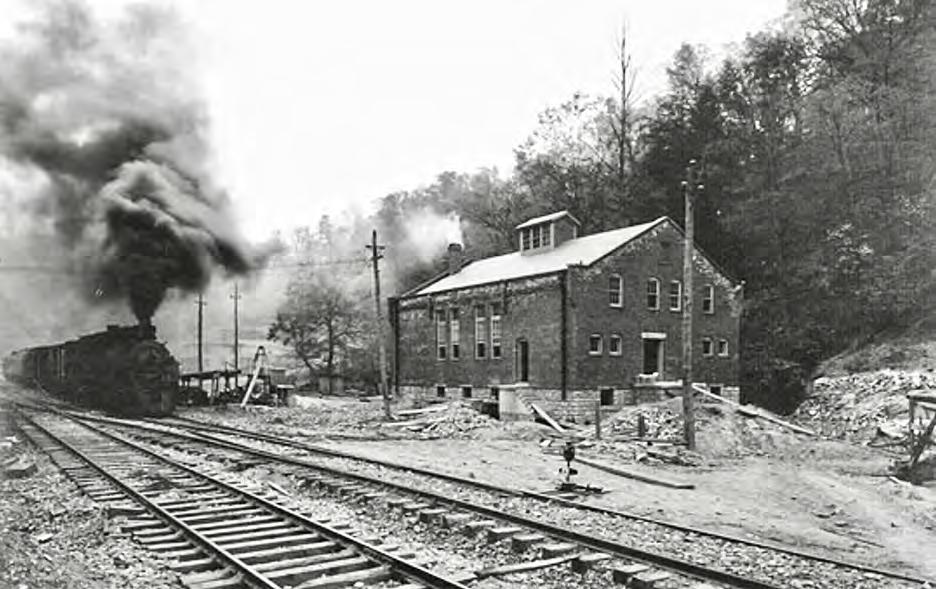

In the throes of the Great Depression, the National Farm Security Administration commissioned photographers to visually document rural America. The images, many taken in poverty-stricken rural Kentucky, were then used in newsreels and publications across the country.

• • •

In 1975, Louisville photographer Ted Wathen had the

idea to solely document Kentucky by capturing moments in every county in the Commonwealth. He brought on fellow photographers Bob Hower and Bill Burke, thanks to a small grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, for the Kentucky Documentary Photographic Project (KDPP).

Their work was exhibited at the Speed Museum in Louisville; the George Eastman House and International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York; and, ultimately, the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“Then it lay dormant for 30 years,” Wathen said. “We revived it at the Frazier in 2011, and the response to that show was just overwhelming. People kept saying you need to do it again; you need to do it again. So, we did it. We started it again.”

In 2014, the KDPP was reborn with a new grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a grant from the Kentucky Arts Council, and contributions from multiple donors.

Past and present— opposite page, plump baby contestants are judged at the 1940 Shelby County Fair; this page, pictured with their royal trappings, Little Miss and Little Mister Shelby County relax at the 2016 county fair.

Wathen said they went from three “upper-middle-class white guys with graduate degrees” in the 1970s, to more than two dozen photographers—many coming from different countries asking to be a part of something special, even if the pay wasn’t spectacular.

“It’s not generous. It wasn’t as much as they would make doing commercial work,” Wathen said. “But if you talk to them, they’ll all say this is the best thing they ever did.”

Arkansas photographer Rachel Boillot confirmed that in a blog post on KDPP’s website, kydocphoto.com

“As a member of the KDPP team, it is my great honor to record our present in order to contribute to this canon of visual history that I so revere,” she wrote. “It is this very conviction that keeps me going.”

Wathen said more than 200,000 photos were taken during the two periods, and they all weave a story of moments of stark change between 1975 and today.

“People ask the question, ‘What’s the difference between the ’70s and the project you see now?’ ” Wathen said. “If you were gay, you were in the closet … In the ’70s, I never saw

More information about the Kentucky Documentary Photographic Project can be found on its website at kydocphoto.com.

an interracial couple. Nobody was walking around with these little devices in their hands all the time.”

Wathen noted that even the demographics have changed.

“You drive through rural Kentucky now, and you see tobacco barns falling down all over the place. And because the small farms have disappeared, land prices in Kentucky are cheap,” he said. “So, the Mennonites have moved in. The Amish have moved in. In the 1970s, I never saw any Amish.”

The photos will be turned over to the University of

Louisville Photographic Archives once the exhibit ends in November.

The photos from the National Farm Security Administration’s Great Depression project are now preserved in the Library of Congress and available for public use.

Wathen said Kentucky’s moments of history are never over. “We would like some members of the current crop of photographers to take up the mantle and start the project anew in 2055, thus keeping the 40-year cycle intact,” he said. Q

Frazier History Museum

829 West Main Street, Louisville

502.753.5663

Monday-Saturday 10 a.m.-5 p.m.

Sunday 11 a.m.-4 p.m.

The exhibition will be on view through Nov. 9, 2025, and will include a series of public programs, including a collaboration with Louisville’s Photo Biennial.

Through nearly 150 photographs, visitors will gain new insight into the everyday lives of Kentuckians—how they lived, worked, celebrated and endured across decades of cultural and economic change.

“The stories these images tell—some stark, some joyful, all deeply human—remind us of the power of photography to record and reflect a place and its people,” Frazier Senior Curator of Exhibitions Amanda Briede said. “This exhibition is not just about Kentucky’s past. It’s also a mirror held up to its present and a conversation about its future.”

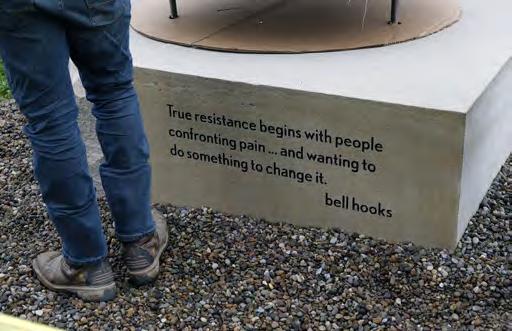

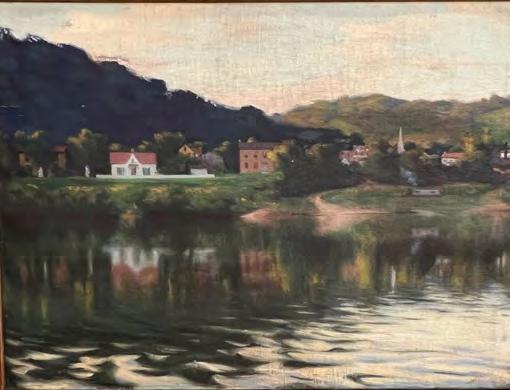

A new Lexington monument honors Lewis and Harriet Hayden, who escaped slavery and returned to the U.S. to serve as conductors on the Underground Railroad

STORY AND PHOTOS BY TOM EBLEN

Like many Southern cities, Lexington has removed century-old Confederate monuments from its public spaces in recent years. Bronze statues of Generals John Hunt Morgan and John C. Breckinridge were relocated in 2017 from the old courthouse square to Lexington Cemetery, where both men are buried. But last month, a new bronze statue was erected to honor two Lexington heroes from the other side of America’s fight over slavery. Their lives were amazing, and the grassroots effort to honor them is a good story, too.

Nearly 500 people crowded Lexington Traditional Magnet School’s lawn at the corner of North Limestone and Fourth streets on June 19 as a larger-than-life statue of Lewis and Harriet Hayden was unveiled. The couple escaped slavery in Lexington in 1844 and resettled in

Boston, where they became influential leaders in the Underground Railroad and abolitionist movement. The statue, by acclaimed Jamaican sculptor Basil Watson and titled “Towards Freedom,” depicts the Haydens striding north together, arms raised and hands clasped.

“It’s fitting that we’re unveiling this statue on Juneteenth, a day when we stand united in acknowledging our past and our nation’s greatest injustice,” Gov. Andy Beshear told the crowd. “We stand here with a recognition that there is still more progress to be made.”

Lewis Hayden was born in in 1814 in the block across North Limestone from the statue. He was enslaved to Presbyterian minister Adam Rankin. At 10, he was traded

to a cabinetmaker for a pair of horses, then had a series of masters. Hayden married an enslaved woman named Esther, and they had a son. But in a widely published letter in 1847, he wrote that statesman Henry Clay sold his wife and child, and he never saw them again. (Clay denied that.) Hayden later married Harriet Bell, who—with her son, Joseph—was enslaved to the owner of a Lexington hat factory.

In 1844, Lewis Hayden was owned by two businessmen who rented him out to the Phoenix Hotel, where he was a waiter. He met two abolitionists: Methodist minister Calvin Fairbank, a native of western New York, and Delia Webster, a schoolteacher from Vermont. On an October evening, Fairbank and Webster rented a carriage and spirited Lewis, Harriet and Joseph out of town. The Underground Railroad smuggled the Haydens to Canada, but they soon moved to Boston to join the fight against slavery. Lewis Hayden became a prominent speaker and activist. The Haydens used their home as a boardinghouse for escaped slaves, and Lewis let it be known that the cellar was packed with gunpowder in case any slavecatchers tried to storm the place.

Fairbank and Webster were less fortunate. They

returned to Lexington, where they were arrested and sent to prison. Gov. William Owsley pardoned Webster two months into her two-year sentence. Fairbank served five years at hard labor until Hayden won his release by raising $650 to compensate his former enslavers.

Hayden, who ran a Boston clothing store to support his activism, became more radical after the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which required people in free states to help return runaways. He helped organize a mob that sprung a captured runaway from a Boston jail, and he worked with abolitionist John Brown to raise money for his unsuccessful raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

During the Civil War, Hayden convinced Massachusetts Gov. John Andrew to persuade President Abraham Lincoln to allow Black men to fight in the Union Army. Hayden was instrumental in organizing the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, whose story was told in the Oscar-winning 1989 movie Glory

Hayden later served in the Massachusetts legislature. When he died in 1889, the New York Age newspaper described Hayden as “easily the most prominent colored

man in New England.”

Harriet Hayden became as well-known as her husband. After the Civil War, she was active in the temperance and women’s suffrage movements, and she organized Black Bostonians’ celebration of the nation’s centennial in 1876. When she died in 1893, she left Harvard University $5,000 to create scholarships for Black medical students.

The Haydens were largely forgotten in Lexington until two books were published in the late 1990s: Delia Webster and the Underground Railroad by Randolph Runyon (1996) and Lewis Hayden and the War Against Slavery by Joel Strangis (1999). The Haydens were just two of many examples of Black people in Kentucky who accomplished great things despite oppression before civil rights laws were passed in the 1960s.

• • •

Researching and telling those stories has become a second career for Yvonne Giles, a retired home extension

Above, sculptor Basil Watson gave a thumbs up to approve the positioning of his statue on its stone pedestal, which includes a quote from Kentucky author bell hooks, left.

agent. Over the past 25 years, Giles has become the go-to expert on Black history in Lexington. So, it was natural that Sherry Maddock, a white East End resident, would seek Giles’ advice in 2016 when she decided the neighborhood needed to commemorate its rich Black history. Giles suggested three possibilities, but it was the Haydens’ story that captured Maddock’s imagination.

“The story of Lewis and Harriet Hayden is a perfect example of enslaved people, their aspirations, their ambition and their courage,” Giles said. “Telling their joint story was very important. Harriet was as strong if not stronger than Lewis.”

Maddock’s vision for the monument quickly attracted support, but the effort stalled after she and her family moved to her husband’s native Australia.

Below, Larry Kezele spoke at an educational program in May about the effort to erect a statue to memorialize the Haydens and educate people about Lexington’s legacy of slavery; bottom, Yvonne Giles, a researcher and expert on Black history in Lexington, posed beside “Towards Freedom.”

Things got going again after the COVID-19 pandemic, thanks to Giles and a group of North Limestone neighbors and interested citizens led by Larry Kezele, who for 45 years has lived in a circa 1860 house across from the statue. “It was just such a compelling story,” said neighbor Linda Carroll, who with her husband, John Morgan, restored and live in the Rankin house, where Hayden was born.

The group formed a nonprofit organization, Lexington Freedom Train (lexfreedomtrain.org), and raised $450,000 for the statue, including the largest-ever grant of $245,000 from the city’s Public Art Commission. The statue and its future maintenance are paid for, and the group is working to raise another $275,000 to combine with $150,000 it has in the bank to build an informational garden around the statue ($300,000) and fund educational curricula and programming ($125,000).

Watson, the sculptor who now works from suburban Atlanta, said one of his goals was to emphasize that the

Haydens were equal partners. “The movement toward freedom or progress is always teamwork,” he said. “They say if you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.”

Frank X Walker, a former Kentucky poet laureate, said being a member of the Freedom Train committee inspired him to write a poem about Lewis Hayden in his latest book, Load in Nine Times. The poem’s title comes from what Fairbank wrote that Hayden told him when he asked why he wanted his help to escape slavery: “Because I am a man.”

It was great to have the governor, the mayor, City Council members and hundreds of people turn out for the statue’s dedication, Kezele said. But what has been more gratifying has been to look out his windows and see Black families stop, admire the statue and take joyful photos of themselves mimicking Lewis and Harriet Hayden, arms raised and hands clasped. “It opens up conversations for the people of the East End,” Kezele said. “So many stories have yet to be told.” Q

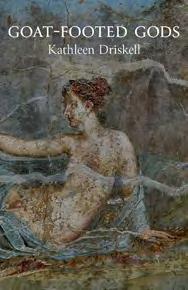

Kentucky’s new poet laureate aims to promote the virtues of creativity and connect the Commonwealth’s current and emerging artists

BY RICHARD TAYLOR

Kentucky has a new poet laureate.

Kathleen Driskell of Louisville will serve a two-year term traveling the Commonwealth to promote the literary arts, encouraging writers young and old through workshops and readings, and setting a good example for those who wish to express themselves creatively. On April 24—Kentucky Writers’ Day (the birthday of the nation’s first poet laureate, Todd County native Robert Penn Warren)—Driskell was inducted as the Commonwealth’s poet laureate in a ceremony presided over by Gov. Andy Beshear in the marble rotunda of the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort.

Before an assembly of former poets

laureate, state officials, lovers of Kentucky literature and the honoree’s family, the governor welcomed the new poet laureate and thanked her predecessor, novelist and poet Silas House, for his energetic performance during the past two years. In addition to Kentucky’s youth poet laureate, Maria Faisal, Driskell and House each read selections of their work under the towering statue of Kentucky’s Abraham Lincoln

Like Lincoln, Driskell grew up in a rural setting in a working-class family, her home being the Oldham County of nearly a half-century ago. She attended Murray State University and received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Louisville before earning a master of fine arts degree from the University of North Carolina

at Greensboro. She returned to Kentucky and began teaching at Spalding University’s low-residency creative writing program in Louisville, rising to the position of chair of the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing at the university. Driskell’s work has appeared in publications as diverse at The New Yorker, Appalachian Review, Southern Review, Shenandoah, and many small-press magazines, and she has received many writing awards.

•

• •

Writer, teacher and arts activist

Kathleen Driskell is the author of six collections of poetry, the most recent of which is Goat-Footed Gods. Her honor as poet laureate is a natural extension of what she has been doing for years, for Driskell sees her role as making

connections among writers and audiences, promoting all the arts— especially writing—in a state nationally known for its community of writers, living and dead. The quality of writing in Kentucky, she affirmed, rivals that of any state in America: “Writers and readers are working every day across the state to support and simplify what it means to be a Kentuckian in all our shapes and colors.” Their backgrounds and approaches are as diverse as the people and places they inhabit: “hills, hollers, glades, plateaus and prairies.”

Now, much of her work relating to place centers on a once-abandoned church that she and her husband, Terry, re-habbed in a square mile outside Louisville. Central to her attention to place is her collection Next Door to the Dead, a reference to the old cemetery in which many members of the church’s congregation are buried. Following the example of Edgar Lee Masters in his Spoon River Anthology written more than l00 years ago, through imagination and fact, Driskell ingeniously recreated the lives of those interred there, including a former slave, a Civil War infantryman and a snake handler.

When asked about her vision for her two years as poet laureate, she affirmed her rootedness in Kentucky. “I want to applaud our many and diverse Kentucky writers, especially contemporary Kentucky writers, as much as I can within and outside the state,” she said. “I’m proud to say that great writing in Kentucky is thriving across all genres, from poets to screenwriters.”

Driskell shared a kind of artistic

statement of faith that might be a credo for every serious artist. “I believe when we engage our creativity, we’re being given access to the sacred, the divine,” she said. “When we activate our imaginations, we are activating our capacity to love ourselves, to love one another. We create a world that demonstrates our shared humanity is strengthened through, paradoxically, writing about the differences among us.”

Driskell’s former service as chair of the board of a national network of writers, the Association of Writers & Writing Programs, has given her a perspective on Kentucky’s place in the forum of national literature in which Kentucky writers are prominently represented. Connecting, she said, is the key, recognizing the importance of connectedness among writers, especially between experienced and emerging writers. To promote this goal, she and friends founded the Kentucky Writers Coalition when she returned to the state from graduate school 30 years ago. The organization, which eventually had 2,500 members, provided a clearinghouse to share information about writing conferences, readings and publications across Kentucky. The internet eventually became a more favorable conduit for exchanging such information and bringing writers, teachers, librarians and bookstores together.

As poet laureate, Driskell said that she wants to connect with some of the existing writing groups within the state, such as the Kentucky Poetry Society, with master classes. Energetic and plain-spoken, she also wants to work with other writers who are also teachers, concentrating on Kentucky high schools, where the next generation of Kentucky writers is formed. This may involve readings and workshops, perhaps at state parks, as previous poets laureate House Frank X Walker and Crystal Wilkinson have done successfully, places in which writers have the opportunity to explore and write about the natural world. Q

Richard Taylor is a former Kentucky poet laureate (1999-2001) and the author of several books, including Elkhorn: Evolution of a Kentucky Landscape.

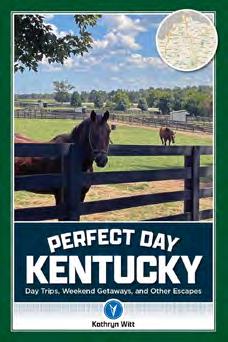

BY EDWARD ODONGO

When summer stretches and is nearing autumn in the Bluegrass State, it’s the optimal time to explore the quieter regions of Kentucky. Beyond the famous horse racing tracks and fried chicken lies a collection of small Kentucky towns rich in history, hospitality and surprise.

From Abraham Lincoln’s hometown to a wine-tasting

experience in one of the country’s oldest bourbon distilleries, these hidden Kentucky gems offer memorable moments and historical narratives worth discovering. Whether you’re learning about the historic trails, traveling the bourbon trails, or exploring the hiking trails, these Kentucky destinations are calling.

Every glass of the amber elixir in Bardstown represents 243 years of bourbon heritage. Named “Most Beautiful Small Town in America” by Rand McNally/USA Today in 2012, Bardstown is a historic treasure rich in character. With a small-town spirit, it has tantalizing Kentucky charm and historic architecture.

Tucked inside the town’s heart are lively taverns, boutique distilleries and museums, making history seem present and close enough to touch. Every visit is a blend of past and present, whether you are dashing into family-owned stops or getting lost in a giant bourbon distillery. Bardstown is the country’s bourbon gem, sitting at the center of Kentucky’s legendary Bourbon Trail. It features more than 10 distillery experiences within a short drive of downtown.

STEPHEN FOSTER STORY THEATER

Experience a slice of Kentucky’s rich musical history

411 East Stephen Foster Avenue

502.348.5971

stephenfoster.com

MY OLD KENTUCKY HOME STATE PARK

Historic Federal Hill mansion linked to Stephen Foster’s ballad

501 East Stephen Foster Avenue

502.348.3502

visitmyoldkyhome.com

HEAVEN HILL DISTILLERY BOURBON HERITAGE CENTER

The largest family-owned distillery in the country 1311 Gilkey Run Road

502.337.1000

heavenhilldistillery.com

OLD BARDSTOWN VILLAGE AND CIVIL WAR MUSEUM

Kentucky pioneer village highlighting 18th century history and the Civil War

310 East Broadway Street

502.349.0291

civilwarmuseumbardstown.com

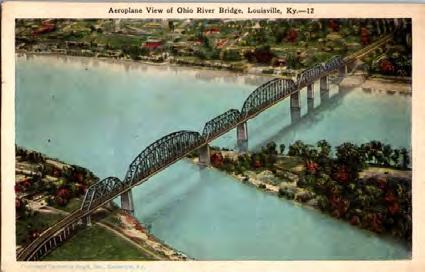

Augusta is a scenic community with a backdrop of the Ohio River. The town offers historical intrigue, stunning views and award-winning wineries and features a timeless charm blended with a dash of Hollywood. Augusta was home to legendary singer and actress Rosemary Clooney from 1980 until her 2002 death. Today, it is home to retired journalist and television host Nick Clooney and his wife, Nina, who raised their famous actor-filmmaker son, George Clooney, there. Lucky visitors might spot George in Augusta from time to time visiting his parents. Enjoy wine tasting in the country’s oldest cellars or catch the sunset while riding the Jenny Ann Ferry— one of the few remaining passenger ferries in the area. The highlight of an Augusta trip should be visiting The Rosemary Clooney House, a museum packed with memorabilia from the beloved film White Christmas

MUST-SEE ATTRACTIONS

1811 HISTORIC JAIL

West 2nd Street

606.756.2183

kentuckytourism.com/ explore/1811-historic-jail-521

BAKER-BIRD WINERY & DISTILLERY

A wine-tasting experience in a cellar dating back to the 1850s 4465 Augusta Chatham Road

606.756.3739

bakerbirdwinerydistillery.com

The largest repository of memorabilia and artifacts from the movie White Christmas 106 East Riverside Drive

502.383.9911

rosemaryclooney.org

AUGUSTA FERRY

Operating since 1798, it offers unbeatable views of the Ohio River 104 East Riverside Drive augustaky.gov/ferry

JOEL RAY’S LINCOLN JAMBOREE + RESTAURANT

Experience classic country variety shows

2579 Lincoln Farm Road

270.358.3545

thelincolnjamboree.com

LINCOLN’S BOYHOOD HOME AT KNOB CREEK

Follow the groundbreaking steps of a future president

7120 Bardstown Road

502.549.3741

nps.gov/abli/planyourvisit/ directions.htm

ABRAHAM LINCOLN BIRTHPLACE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

See the Lincoln Memorial Building in which a tiny “Symbolic Birth Cabin” is housed

2995 Lincoln Farm Road

270.358.3137

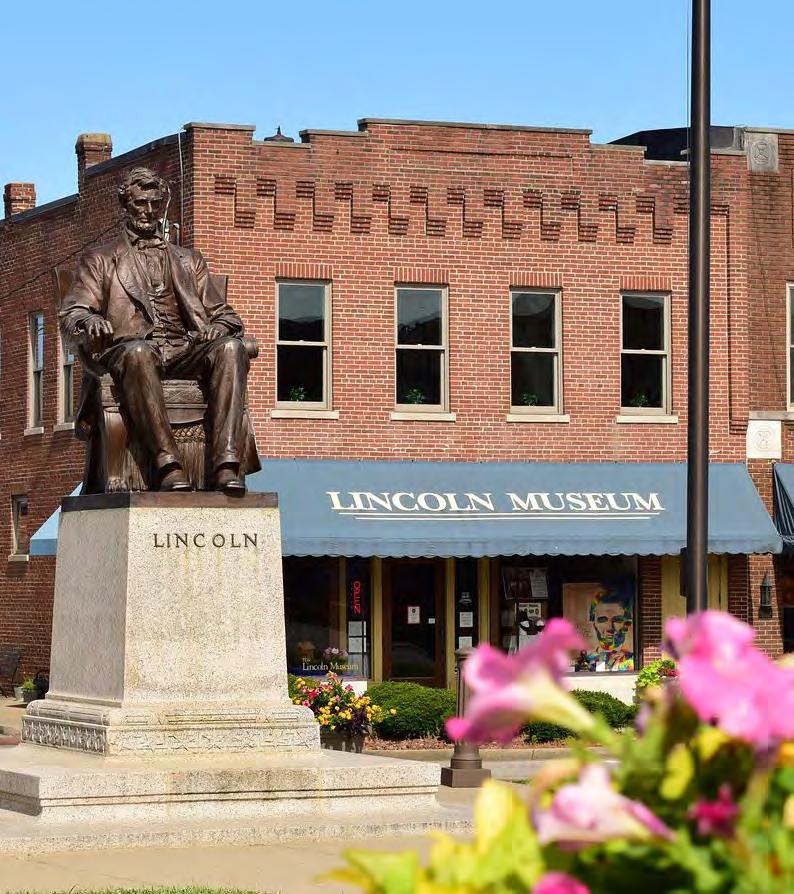

nps.gov/abli

THE LINCOLN MUSEUM

Enjoy immersive experiences and learn about rare artifacts

66 Lincoln Square

270.358.3163

lincolnmuseum-ky.org

Hodgenville’s identity is tied to Abraham Lincoln, who granted it immense popularity as a tourist destination. The town invites visitors to explore one of America’s most iconic origin stories, starting from the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park. Local legend Laha’s Red Castle has been flipping what many describe as Kentucky’s best burger for 90 years. Don’t miss Joel Ray’s Lincoln Jamboree or the Hodgenville Summer Concert Series. With food trucks, live music, bounce houses and, of course, spectacular fireworks, the Fourth of July is always a mind-blowing experience in Hodgenville. Finally, grab a coffee at Vibe Coffee and sample sweets at The Sweet Shoppe.

For more on Hodgenville, see page 42.

Get your feet wet this summer in the town of Grand Rivers. Whether kayaking across Lake Barkley, hiking forest trails, or casting a line on Kentucky Lake, outdoor excursions remain the main attraction. Local favorite Patti’s 1880’s Settlement is a must-visit locale, not just for its legendary 2-inch pork chops, but also for its Southern flair, whimsical gardens and gift shops. Dive into the Grand Rivers nightlife by heading to The Thirsty Turtle or Between the Lakes Tap House.

MUST-SEE ATTRACTIONS

THE BADGETT PLAYHOUSE

Catch a tribute show or musical revue in a cozy theater

1838 J.H. O’Bryan Avenue

270.362.4224

thebadgettplayhouse.com

PATTI’S 1880’S SETTLEMENT

A distinctive dining and shopping destination

1793 J.H. O’Bryan Avenue

270.362.8844

pattis1880s.com

LAND BETWEEN THE LAKES NATIONAL RECREATION AREA

170,000 acres of natural adventure, from planetariums to elk herds

238 Visitor Center Drive

Golden Pond 1.800.525.7077

landbetweenthelakes.us

FUN FACT: It is the only city in the world flanked by two massive dams—Kentucky Dam and Barkley Dam.

KENTUCKY DAM AND VISITOR CENTER

Enjoy scenic lake views as you learn about hydroelectric power

640 Kentucky Dam Road

270.362.4318

tva.com/energy/our-powersystem/hydroelectric/kentucky

Greenville offers a unique charm that features a perfect blend of history and hospitality. Founded in 1799, the Western Kentucky town boasts a beautiful, historic downtown square with a century-old courthouse, inviting cafés and locally owned shops.

Get lost in Brizendine Brothers Nature Park’s tranquil wooded paths. Get your feet wet as you paddle across Lake Malone State Park. Unwind at Sip&Spin Coffee & Records while enjoying some vinyl tunes, or visit the Muhlenberg Community Theatre to catch a local show.

MUST-SEE ATTRACTIONS

THISTLE COTTAGE

Local history museum and cultural center featuring rotating exhibits

122 South Cherry Street

270.338.4760

muhlenbergarts.org/ thistle-cottage

BRIZENDINE BROTHERS NATURE PARK

Outdoor lovers’ paradise, best for walking, picnics and birdwatching

Chatham Lane

kentuckytourism.com/explore/ brizendine-brothers-naturepark-5360

NORTH MAIN STREET HISTORIC DISTRICT

A sampling of late 19th and early 20th century American architecture

199-135 U.S. 62

MUHLENBERG COUNTY COURTHOUSE

A neoclassical Kentucky architectural gem

100 South Main Street

270.377.3970

muhlenbergcounty.org

Kentucky’s 121 nursing programs train students to make a difference in the lives of their patients

BY JACKIE HOLLENKAMP BENTLEY

Nursing can be a thankless job—12-hour shifts, cranky patients and less-thandesirable duties we’d rather not put in print. But then there are the countless rewards that go unmentioned.

“You have the best vantage point to make such a difference,” said J oy Pennington, an executive nurse and academic officer with the Kentucky Board of Nursing (KBN). “It’s not just about going in and starting an IV. It’s about showing [patients] care and compassion, a smile and the understanding that you truly do care about them, and that can make all the difference in the world for the family and for the patient. That is an amazing position to be in, as a nurse, to make such a difference.”

Kentucky colleges and universities operated 121 nursing programs, where students can attain these degrees: doctor of nursing practice (DNP), master of science in nursing (MSN), baccalaureate degree in

nursing (BSN), associate degree in nursing (ASN) and practical nursing diploma (PN).

Kelly Jenkins, KBN’s executive director, said the board’s job is to ensure Kentucky’s colleges and universities produce qualified nurses to continue making that difference.

“Kentucky does the best, from my board of nursing employees all the way through all of our programs and the faculty,” Jenkins said. “We have some excellent schools out there.”

Once they have completed a nursing degree, graduates must pass the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX).

On average, Kentucky’s nursing programs either have met or exceeded the national average for first-time test takers.

Pennington credited the programs’ faculty.

“They really get involved with the students on a

The Kentucky Board of Nursing protects the public by development and enforcement of state laws governing the safe practice of nurses, dialysis technicians, and licensed certified professional midwives.

LEARN MORE kbn.ky.gov

holistic level, and I think that a lot of your faculty invest heart and soul into those students,” she said. “They know that these individuals are going to take care of them or their family one day, and they take that very seriously.”

Jenkins agreed.

“You can’t have good students who can successfully pass the NCLEX without the great faculty that we have been blessed to have here in Kentucky,” she said. “It’s definitely a calling, because sometimes their students get out of school and they go to a hospital and they make more money from day one than our faculty who taught them how to become a nurse.”

A program occasionally may struggle to reach the board’s NCLEX performance benchmark of 80 percent pass rate, but Pennington said that’s when the board comes in with a proactive approach.

“We’ve changed all of our workshops … that literally show them exactly what we’re looking for and how to do it, and we even give them examples,” Pennington said. “We don’t leave them in the wind to just guess because how can a program succeed if you’re constantly struggling to figure out what to do to make that happen?”

The approach is making a difference. Since 2020, Kentucky’s NCLEX pass rate has ranged from 87.7 percent to 89.6 percent. Q

For a comprehensive look at all of the Commonwealth’s nursing programs, visit the Kentucky Board of Nursing’s website, kbn.ky.gov

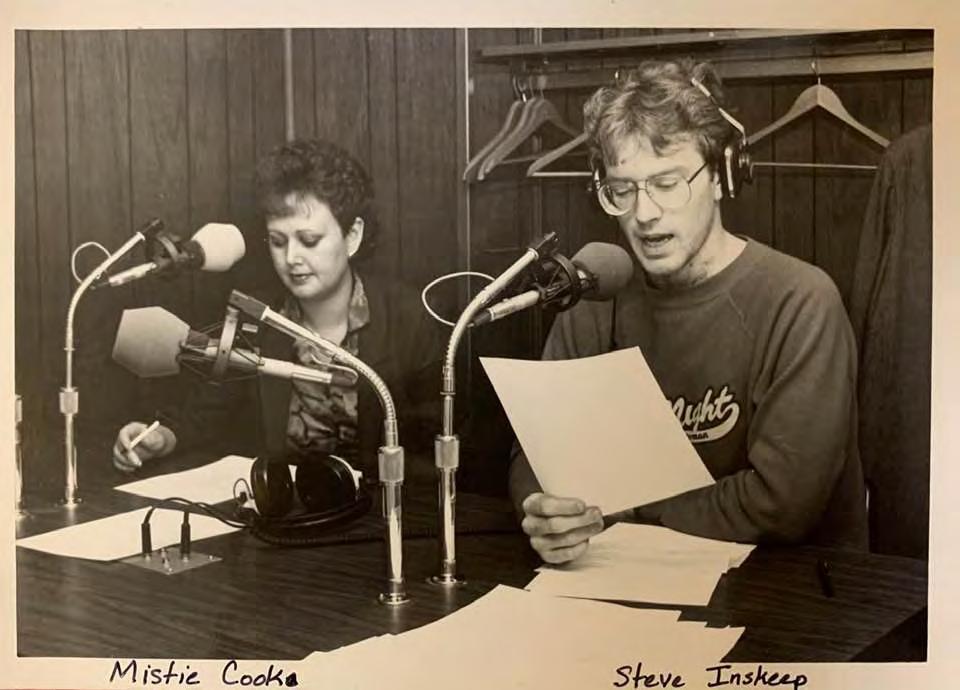

For 60 years, Morehead State University’s WMKY-FM has served listeners in Eastern Kentucky while training generations of students for broadcasting careers

BY JARRETT VAN METER

While growing up in Pattersonville, New York, Paul Hitchcock relied on the radio as his vessel for optimism. He listened to Wolfman Jack, Dick Clark and Casey Kasem on his portable AM/FM device and dreamed of being on the other side of the speaker. He longed to connect with an audience in the same manner, wielding clarity, brevity and assuredness. But a large hurdle stood before him: Hitchcock stuttered.

The speech impediment caused him to withdraw. He was shy. He didn’t answer the phone or the door. The radio provided company.

“I remember saying to myself, ‘If I ever get fixed or ever get healed … if they figure out why I can’t talk, I want to be a DJ,’ ” Hitchcock remembers.

He ultimately found relief working with a speech therapist. On his own time, Hitchcock bolstered his growing confidence by pretending to be a radio host. He recorded himself on cassette tapes, asking traditional interview questions to imaginary guests, then borrowing snippets of popular songs to use as the responses. The gag was fresh out of the Rick Dees playbook and served as his first taste of production. He sent the cassettes to his older sister, who was off at college.

Hitchcock’s family moved to Tennessee for his high school years. He chose to attend Kentucky’s Georgetown College “for the sole purpose” of working at the campus radio station, WRVG-FM. He never took a broadcasting class but learned by doing. He served as the station’s music director before becoming the program director. During his senior year at Georgetown and first year out of college, Hitchcock worked professionally for WTKC 1300 in Lexington, then spent a year in Knoxville before moving to Morehead in 1986 to get his master’s degree in communications from Morehead State University. Part of his work-study package was a role as the graduate assistant for sports at the campus radio station, WMKY-FM.

The station’s reputation preceded it. WMKY debuted in 1965 as a four-hour, 10-watt station. Four years later, it became the first station in the country to receive a Department of Health, Education, and Welfare grant to increase its broadcast power to 50,000 watts. In 1980, it became an NPR affiliate station. As Hitchcock walked in on his first day in 1986, he could feel the momentum. All the equipment was new, from the reel-to-reel recorders to the cart machines. Between full-time staff and students, roughly a dozen people buzzed about. The newsroom was active, the Associated Press machine ticking away: duh-duhduhduhduh-duh.

“It was the big time,” Hitchcock remembers.

WMKY, also known as Morehead State Public Radio (MSPR), is licensed to operate at 37,000 watts, according to its website.

Now the general manager, Hitchcock says the station’s secret sauce has been the roughly 1,000 students who have passed through the studio since 1965. Included in that number are all three members of the station’s current core team: Hitchcock, News Director Samantha Morrill and Operations Director Greg Jenkins

On Morrill’s first day as a sophomore in 2013, then-News Director Chuck Mraz handed her a press release from a local hospital about a new clinical service it was rolling out. Mraz told Morrill to write up a “voicer.” Afterward, he sent her into the recording booth to read what she had written.

“I was really shocked,” Morrill remembers. “Day one I was going to get to be on the radio. I was like, ‘This is wild and also very cool.’ I was excited to get in my car later and listen to it, and hear myself on the radio.”

After graduating in 2016, Morrill was hired by WYMT, a commercial television station based in Hazard. Getting internet installed in her Hazard apartment proved to be a lengthy process, during which Morrill resorted to other

means of entertainment. First, she ran through her DVDs of episodes of The X-Files and The Office. Then, she turned on her handheld radio, picking up Richmond’s WEKU-FM. The signal provided an unexpected thrill, and it dawned on her that the experience wasn’t isolated.

“There are people out there who, at any point in time, for whatever reason—they can’t get internet or their electricity is out … they can turn on a radio, and they can pick up a public broadcasting signal and their local NPR station to get news, entertainment, music and weather updates,” Morrill says.

Eventually, Morrill switched back to the medium, first working at WEKU in Richmond before returning to Morehead and WMKY. She was named news director in 2023.

“When you talk about audio, it’s very intimate,” Morrill says. “It’s right there in your ears, getting to experience all of the different stories and content, music, commentary—whatever it may be.”

•

While Hitchcock and Morrill come from broadcasting backgrounds, Jenkins found radio via his interest in music. He first heard WMKY while studying music as an undergraduate at MSU but didn’t begin helping out until he enrolled in a master’s program at the school and landed a graduate assistantship. He left briefly after graduation for

a stint as a high school music and band teacher but returned a few years later when a full-time position came open at WMKY.

Jenkins loves mentoring, learning from, and collaborating with the students.

“We’re producing stuff; we’re having fun doing it; we have deadlines; we have a job to do,” Jenkins says. “We have daily tasks to get done, and everybody on the team is just working together to make those things happen.”

As WMKY celebrates 60 years of public service, one of its principal sources of funding is on the brink. In June, the U.S. House of Representatives narrowly voted in favor of a rescissions package that would eliminate more than $1 billion of previously approved funds for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a primary means of support for local stations such as WMKY. As of this writing, it is pending in the Senate.

Despite the ominous cloud cast by the development, Hitchcock hopes people maintain faith in the work that his team, and others like it, do. Radio can serve as an ally to those who need it, as he did when he was a young boy.

“It’s a trusted companion, through good times and bad,” Hitchcock says of radio. “It’s being in touch with your community … They’re talking to you as you listen. It’s a one-on-one communication, and that’s how it should be. It’s making that connection on a one-on-one basis. As humans, we look for that.” Q

by Kentucky Monthly Magazine

BY GARY P. WEST

Only a few feet from the Abraham Lincoln statue on the public square in Hodgenville are two notto-miss eateries: The Sweet Shoppe and Laha’s Red Castle. About a half-mile down the road is Joel Ray’s Lincoln Jamboree, another restaurant visitors won’t want to overlook.

There are times when Patrick Durham has flashbacks to some 23 years ago, when his wife, Paula, encouraged him to start making fudge. She had seen her sister doing it and told her husband, “We can do that.”

And did they ever.

Today, The Sweet Shoppe boils up more than 42,000 pounds of fudge a year. Beginning with two kettles in what was a 1940s gas station, they have grown so much that they now have an off-site location to house their

eight double-boiler kettles.

“Each kettle makes 36 pounds of fudge,” Patrick said. “And making as many as 30 different flavors, we needed more space. At one time, we were selling at 50 festivals a year but have scaled back to about 12. Working a festival is demanding.”

This is where the Durhams’ son, Forrest, has joined in. At 27, he’s been around The Sweet Shoppe almost from its beginning.

“I was 6 when I started hanging around [the shop],” he said. “I’m pretty much doing most of it, as Dad has stepped back some. Anybody who has ever made fudge knows there’s a bit of an art to it.”

Patrick smiled when he recalled working at a factory in Elizabethtown, when he didn’t see much of his two kids and Paula, and then he found out that old service station—which, in the interim, was a garden center—might become vacant.

“When I got this spot, it gave me the confidence to think we could make it,” Patrick said. “Tourist after tourist drives by here on the way to Lincoln’s birthplace and on the Bourbon Trail.”

Two years after The Sweet Shoppe’s March 2002 opening, ice cream was added to the chalkboard menu. “We added Blue Bell and Velvet and, believe it or not, it now outsells the fudge,” Patrick said.

The Durhams constantly experiment with new flavors. “We take suggestions and try some of them,” Forrest said. “We have a maple bacon [flavor] and use real bacon we actually fry.”

Peanut butter fudge tops The Sweet Shoppe’s bestseller list. Tiger fudge is close behind. It is a vanilla fudge swirled with melted peanut butter and topped with a drizzle of chocolate fudge. The Durhams also make a Kentucky bourbon-flavored fudge.

Just when you thought it couldn’t get any better, they have added dessert pastries, along with cookies, brownies, chess bars and Rice Krispie treats.

• • •

Not far from The Sweet Shoppe is an iconic hamburger joint that has been selling its specialty for 91 years. Most who live in and around Hodgenville don’t remember when there wasn’t a Laha’s Red Castle sitting at the corner of the town square, with employees serving up burgers as fast as they could get them off the grill and onto a bun. That’s because Laha’s (pronounced “Layhays”) been at the same location since 1934, when William and Sally Laha started selling hamburgers from a little walk-up downtown. At the time, White Castle was already established, so Red Castle it was.

Today, Ryan Jeffries runs the show. “I’m a fourth generation,” he said. “My mother was a Laha, and I couldn’t wait to be big enough to work here. When I was 10, I was finally tall enough to cook on the grill and smash ’em out.”

That Vulcan grill is the same one that was installed when the present

building opened in the 1950s.

The only seating is 10 counter stools, and the four servers, plus Ryan, glide easily out of the way of each other in the 500-square-foot space.

Food service is classic at Laha’s. The burgers and chili dogs are served on wax paper, and drinks are served in cups or bottles of Coke and Ski. Bowls of chili and fries are popular items.

“We serve about 600 burgers a day, plus 75 to 80 chili dogs,” Jeffries said, as he easily manages up to 40 burgers with onions and cheese on the grill. “Our walk-up window and carryout orders make up 75 percent of our business.”

The word is out on Laha’s. No less than Food & Wine magazine honored its specialty as the best burger in Kentucky in 2021.

“We’ve had customers from South Africa and South Korea,” Jeffries said. “And one lady came in from St. Louis. Said she saw something on TV about us and had a dream about our hamburgers, and the next morning told her husband where they were going to each lunch—Laha’s. She said they drove six hours to get here.”

It’s not unusual for customers to be

lined up in front of the door before 10 a.m., when the eatery opens.

Tourists come to Hodgenville to visit Lincoln’s birthplace, and quite a few seek a place to eat. Laha’s pops up on an internet search, so the parking spots in the front and rear of the restaurant are occupied primarily by out-of-town cars.

“I’m doing what I always wanted to do,” Jeffries said. “But it’s harder than I thought it would be.” •

Down the road a bit, not far from the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Park, is Joel Ray’s Lincoln Jamboree. Even though owner and operator Joel Ray Sprowls died in 2020, the Lincoln Jamboree’s shows and restaurant have stayed the course.

Open since 1954, the Lincoln Jamboree hosts primarily country music acts. The showroom and restaurant recently have been updated. The restaurant serves up country cooking at its finest, including lunch and dinner specials, a Saturday night special and an “oldfashioned Sunday luncheon.” Q

The Kentucky State Fair was established in 1816 by a Fayette County farmer named Colonel Lewis Sanders, who is not known to be relative of Colonel Harland Sanders (actually an Indiana native) of fried chicken fame. The event became our official state fair in 1902. For many years, the fair moved from city to city, but in 1907, Louisville became the fair’s permanent home. This year’s fair takes place Aug.14-24. For more information, visit kystatefair.org

a magazine published for Kentuckians everywhere

Charles Hayes Jr. • Founder

Stephen M. Vest • Publisher

Deborah Kohl Kremer • Editor

Rebecca Redding • Typographist

One-Year Subscription to Kentucky Monthly: $25

Letters to the Kentucky Explorer

Letters may be edited for clarification and brevity.

Someone Lost Their Marbles

I enjoyed “Bully for Marbles” by P.K. Compton in the May issue of Kentucky Explorer. I’d like to share with him that our historic home in Madisonville was East Broadway School in the early 1900s. When we find marbles during our gardening, it thrills us. Some look very old and different.

Deb Allen, Madisonville

Abbreviations to Use to Find 50 Percent More Ancestors in Newspaper Articles

n Use an abbreviation instead of a full word.

n Typesetters used abbreviations to save space

n Enter the abbreviation in your search criteria

n Find hidden articles

Els for Elizabeth Wm for William Corp for Corporation

NYC for New York City

Jos for Joseph Margt for Margaret Saml for Samuel Deb for Deborah

Hy for Henry

My for Mary Agt for Agent

Ag for Agnes

Capt for Captain Co for Company

Pres for President Col for Colonel Chas for Charles

Benj for Benjamin Cpl for Corporal

Geo for George Robt for Robert Thos for Thomas

Genl for General Danl for Daniel Pvt for Private Theo for Theodore CPO for Chief Petty Officer

Courtesy of Kenneth Marks, The Ancestor Hunt, theancestorhunt.com.

FOUNDED 1986, VOLUME 40, NO. 6

Kentucky Explorer appears inside each issue of Kentucky Monthly magazine. Subscriptions can be purchased online at shopkentuckymonthly.com or by calling 1.888.329.0053.

In memory of Donna Jean Hayes, 1948-2019

Virginia was owned by England until after the Revolutionary War. Kentucky was owned by Virginia until it became a state on June 1, 1792.

1743—Frederick County, Virginia, was created. 1757—Loudon County, Virginia, was formed from Fairfax County, Virginia.

1770—Botetourt County, Virginia, was formed from Augusta County, Virginia.

1772—Fincastle County was created from part of Botetourt County.

1776—The United States declared its independence from Great Britain on July 4. It became a sovereign nation on Jan. 14, 1784.

1777—Montgomery, Washington and Kentucky counties were created from Fincastle County, which was abolished Dec. 31, 1776.

1780—Lincoln, Fayette and Jefferson counties were formed from Kentucky County.

1785—Nelson County was formed.

1786—Bourbon, Mercer and Madison counties were formed.

1789—Mason and Woodford counties were formed.

1792—Kentucky became a state with those counties mentioned above.

1792-1912—The remainder of the 120 counties were formed. The last one established was McCreary County on March 12, 1912.

Compiled primarily from An Historical Atlas of Kentucky and Her Counties by Wendell H. Rone Sr. This was part of the 1815-1965 Daviess County Sesquicentennial Edition.

By Paul Vaughn, Hopkinsville

The Southern Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Kentucky are a rugged and diverse mountain range. They are considered to be a temperate rainforest. During certain times of the year, the foliage will drip with water as if it had rained all night.

According to mountain lore, when the foliage drips extra large amounts of water, they are weeping for a Kentucky champion who has died. On Nov. 22, 2001, Dr. Adron Doran died, and the mountains wept. Truly, Adron Doran was a champion for the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

I first heard of Doran when I was a student at Maysville High School. At that time, he was president of Morehead State University. Articles about the university and the many changes taking place during that time of growth under Doran often appeared in the local newspaper, The Ledger Independent. It was during this time that Maysville High School re-established its football program through the work of Dr. James Tenery and Tom Browning of Browning Manufacturing. The equipment for this program was generously donated by Morehead State University.

Morehead grew from a small teachers’ college to a major university and stands as a respected educational institution in Eastern Kentucky because of the foundation laid by Doran.

Doran was a student of Restoration church history. He co-authored The Christian Scholar: A Biography of Hall Laurie Calhoun with J.E. Choate and, in 1997, he wrote a book titled Restoring New Testament Christianity. During his life, Doran wrote numerous articles on the Restoration Movement that will aid students of Restoration history for many years to come.

Doran was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1943 and served as speaker of the House in 1950. Many people viewed his educational achievements or his political efforts as the most important events in his life. However, he viewed his work as a Gospel preacher as more important than anything else. He faithfully preached the Gospel for many years in the churches of Christ.

Adron Doran was born on Sept. 1, 1909, in Western Kentucky in a three-room tenant house in Graves County. His father was Edward Conway Doran, and his mother was Mary Elizabeth (Clemons) Doran. Adron graduated from Cuba High School in Graves County. His first introduction to higher education was at Free-Hardeman College in Henderson, Tennessee. After receiving his Associate of Arts degree, he entered Murray State University, where he earned bachelor of science and master of arts degrees. He then entered the University of Kentucky, from which he graduated with a doctor of education degree. Doran’s progression as an educator spanned 45 years. His first work in education was as a high school teacher, principal and coach before becoming president of Morehead State University, where he served for 23 years (1954-77).

Doran accomplished many things in his life, but one could not have met him without recognizing that he viewed his marriage to Mignon as second only to his service to God. Doran married Mignon Louise McClain on Aug. 23, 1931. His love for his wife was one of the greatest lessons the students at Morehead State University could have learned during his time as president. He valued family as more important than even being a president of a university.

I will relate one example of the love this couple had for each other. Doran was invited to deliver a series of lessons on the New Testament at the Jackson Church of Christ in Jackson (Breathitt County). Just before the lectures, Mignon became ill. He did not want to leave her behind, and she did not want him to cancel the lectures. So she went with him but stayed in the motel while he delivered the lectures. As soon as each lesson was over, he rushed to the motel to see how his beloved wife was doing.

In his life, Doran was a great encourager to young people. He certainly was to me. He is greatly missed! The mountains were not the only things that wept at his passing.

Send memories to Deborah Kohl Kremer at deb@kentuckymonthly.com or mail to Kentucky Monthly, Attn: Deb Kremer, P.O. Box 559, Frankfort, KY 40602.

“I

By Peggy Patterson Mull, Louisville

In the 1940s, we lived far out in the country. There was no electricity or running water, but we children didn’t know that was a problem at the time! I was about 10 years old and my brother and sister were 6 and 2 when we were allowed to go berry picking with our mother.

She waited for a nice warm, sunny day in August, when the berries were at their peak. That day, she explained to us that we each would have a onequart bucket that we could fill with the fattest ripe berries we could find. First, though, we could eat as many as we wanted. When our stomachs were full, then we were to start picking in earnest. She told us our fingers would be stained with the juice along with the old clothes we wore, and that the stain would not wash off—it had to wear off—but we didn’t care. We were warned to watch for snakes because rattlers and copperheads were known to be in the area and loved to sun themselves wherever they found a patch of sunlight. If we ever smelled watermelon, we were to freeze in place and call her so that she could locate the snake and get us away safely. People in the area swore that the smell of watermelon was a sure sign a poisonous snake was nearby. Luckily, we never smelled watermelon or saw a snake, probably because three noisy children might have been enough to cause any snake within a mile to slither quickly and quietly away well in advance of our arrival.

When our buckets were filled with berries, they were emptied into one of my mother’s two 1-gallon buckets. When those were full, it was time to go home. Berry picking usually took a whole morning, and the afternoon was for making the jam.

In the dirt yard by the house, there was a permanent fire site. Three stacks of stones were piled about 12 inches high to allow for a wood fire under the washtub, where water was heated. The galvanized aluminum washtub was always hanging on a nail on the wall outside the house and taken down only to sterilize canning jars and for use on wash day.

Kindling was first placed under the tub, then lit. As it caught fire, larger pieces of wood were added so that a good fire was going. Water was drawn from a dug well close by using a winch to draw it up in a gallon bucket. The tub was filled about three-fourths full and heated to boiling. It was my 6-year-old brother’s job to make sure the fire was fed and kept going. The wood had been chopped by my father and stacked near the house for use both inside and outside. Ten to 12 pint jars were loaded into a wire rack, lowered into the boiling water, and left there for about 30 minutes. While the jars were being sterilized, my mother took the berries into the kitchen and looked through them to remove any bugs, sticks, bad berries or the occasional green berry that had slipped in. She rinsed them in cold water and placed them in a large pot that sat on the wood cookstove. There was no written recipe; my mother had learned from her mother how much sugar and Sure-Jell had to be added. The Sure-Jell was something containing gelatin that caused the jam to hold its shape. Otherwise, it would have been too runny or loose. Enough water was added to the pot so the berries cooked but did not burn. When they were cooked down to the proper consistency, the jam could be put into the sterilized jars and sealed with melted paraffin to keep it from molding. The jars were filled to within an inch of the top to leave room for the paraffin.

The paraffin was melted in an old 3-pound lard can used just for this purpose. Only a small amount could be melted at a time, since paraffin is highly flammable, and you couldn’t take a chance on an accident when you lived miles out in the country. Approximately a half-inch of paraffin was poured on top of each jar of jam. The jars were then placed on a 2-by-4 inch board, which was part of the wall in the house.

Nothing tasted as good as that homemade blackberry jam, seeds and all, on a homemade biscuit!

By Edwin Hall, Kennesaw, Georgia

The old guy had gray hair, a mean face and a paunch. His St. Louis Cardinals uniform looked official, but it was one or two sizes too small. There was no doubt he was in charge of the proceedings, and we huddled around home plate listening to his every word. There were about 30 of us boys, ranging in age from high school to college. Some wore baseball uniforms, but most of us were attired in some colorful combination of jeans and T-shirts. All were eager to show off our baseball skills at this St. Louis Cardinals tryout camp at Browning Ball Park in Harlan in the hot summer of 1959.