NJ PSYCHOLOGIST

A Publication of the New Jersey Psychological Association

In this issue...

Special Section: New Jersey Department of Human Services Response to the Opioid Crisis

2 CE Credits

Ethics: “It’s Confidential...” When a Client Dies by Suicide

Critical Conversations in Continuing Education for New Jersey Psychologists

Continuing Education Requirement: Why is There an Emphasis on Addressing Diversity in Every Program?

1 CE Credit

Fall 2019 | VOLUME 69 | NUMBER 4

Table of Contents

1 Who’s Who in NJPA 2019

2 President’s Message

3 NJPA Association Life-Cycle

4 Research Briefs

5 Classified Ad

6 2019 Critical Conversations in Continuing Education for New Jersey Psychologists

8 Continuing Education Requirement: Why is There an Emphasis on Addressing Diversity in Every Program? (1 CE)

10 Ethics Update: “It’s Confidential...” When a Client Dies by Suicide

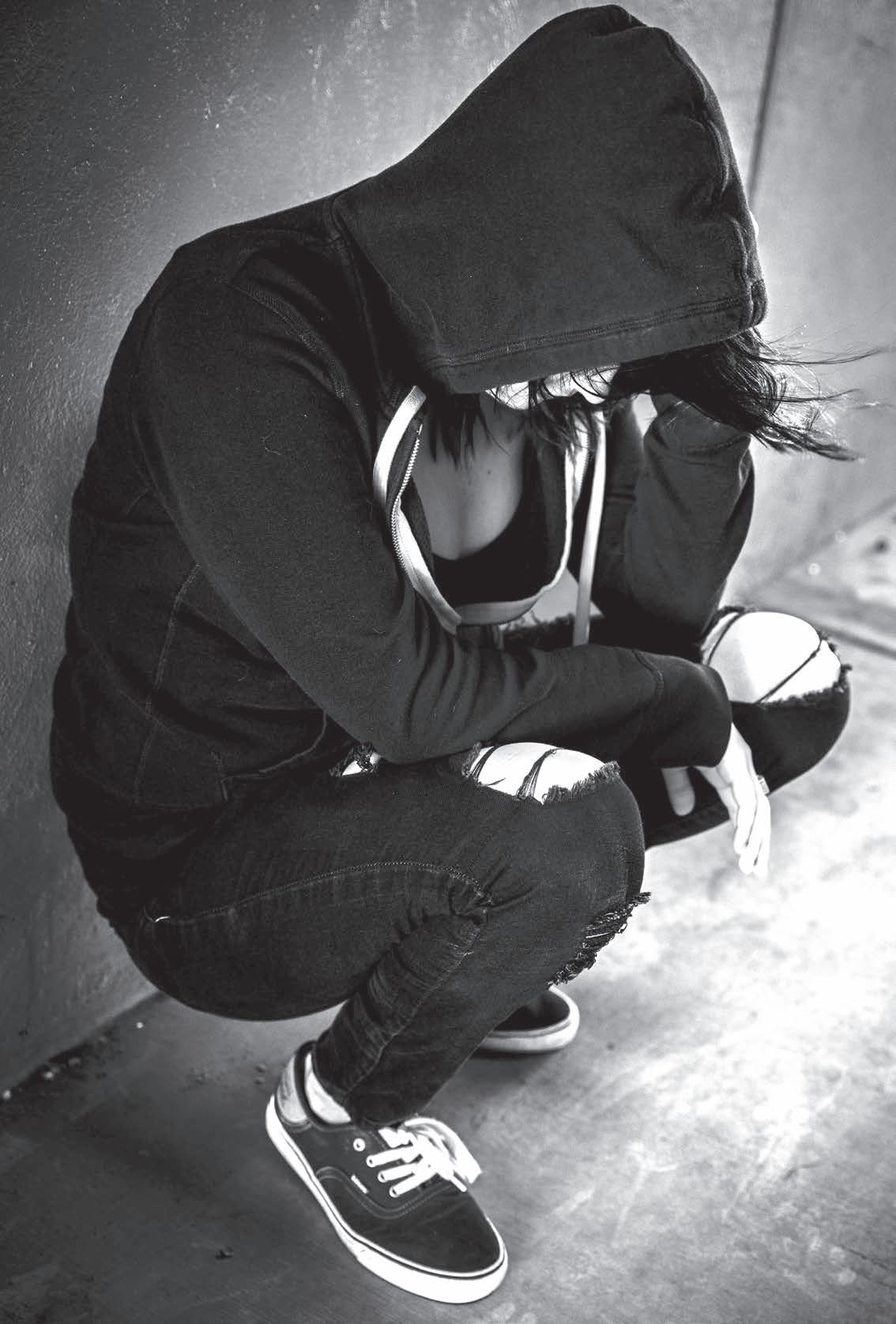

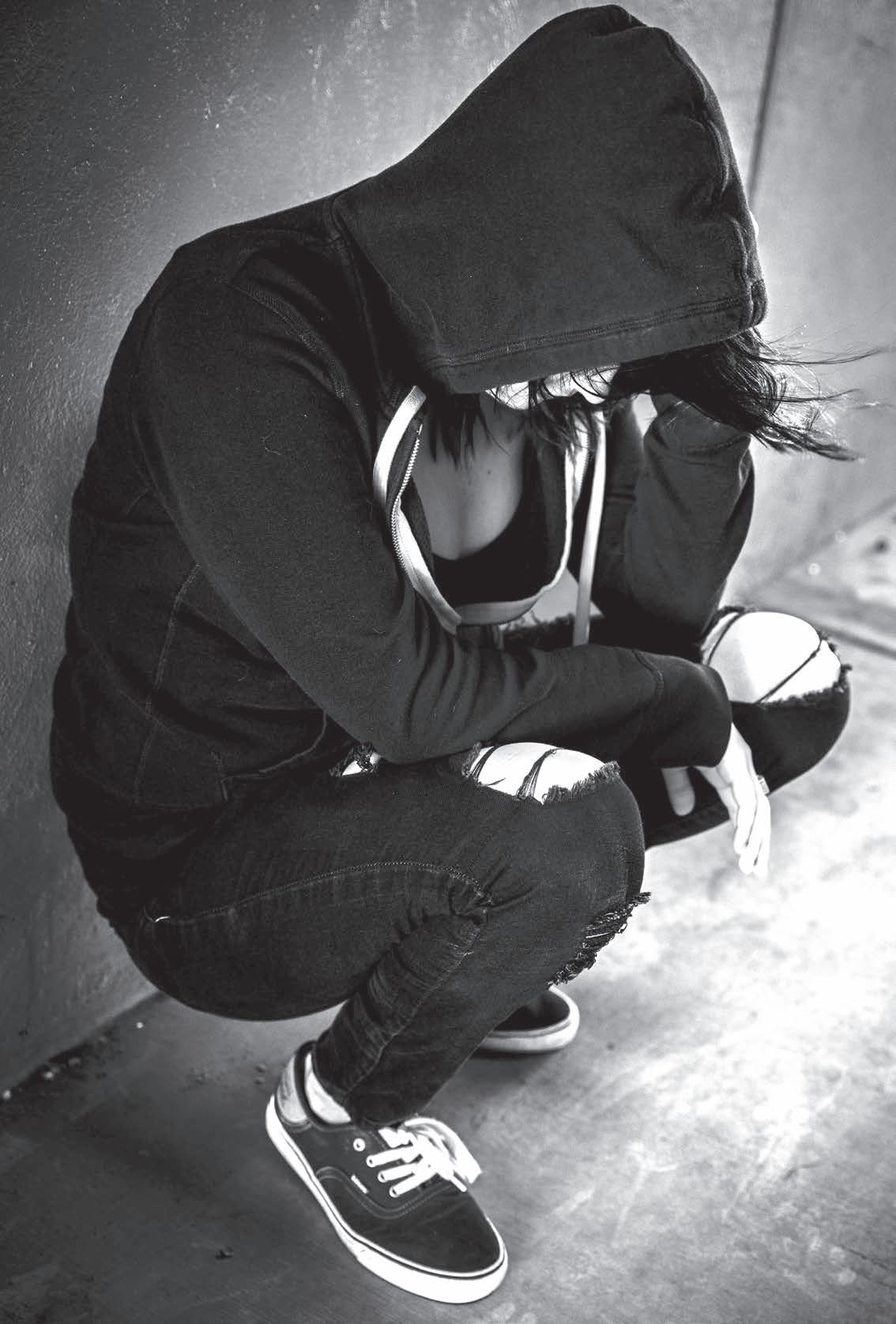

11 Welcome New Members!

12 Graduate Program: William Paterson University

13 Member News

14 Director of Professional Affairs: Scope of Practice

16 Foundation: Community Service Project Grants

19 Special Section: NJ Department of Human Services Response to the Opioid Crisis (2 CE)

25 Book Review: Howard Stern Comes Again (2019)

Who’s Who in NJPA 2019

www.PsychologyNJ.org

Editorial Board

Editor: Gianni Pirelli, PhD

Members:

Jack Aylward, EdD

Ashley Gorman, PhD

Eric Herschman, PsyD

Herman Huber, PhD

Maria Kirchner, PhD

Nathan McClelland, PhD

Anthony Tasso, PhD

Staff Liaison: Christine Gurriere

NJPA Executive Board

President: Morgan Murray, PhD

President-Elect: Lucy Sant’Anna Takagi, PsyD

Past-President: Stephanie Coyne, PhD

Treasurer: Daniel DaSilva, PhD

Secretary: Mary Blakeslee, PhD

Director of Academic Affairs: Francine Conway, PhD

APA Council Representative: Rhonda Allen, PhD

Member-At-Large:

(A) Elio Arrechea, PhD

(A) Phyllis Bolling, PhD

(A) Daniel Lee, PsyD

29

Preparation of Manuscripts

All manuscripts submitted for publication should follow APA style. Manuscripts should be edited, proofread, and ready for publication. Please prepare your manuscript in a word-processing program compatible with MS Word using Times New Roman font in 12 point type, left flush. Please submit your manuscript via e-mail to NJPA Central Office and to Gianni Pirelli at e-mail addresses below.

Editorial Policy

Articles accepted for publication will be copyrighted by the Publisher and the Publisher will have the exclusive right to publish, license, and allow others to license, the article in all languages and in all media; however, authors of articles will have the right, upon written consent of the Publisher, to freely use of their material in books or collections of readings authored by themselves. It is understood that authors will not receive remuneration for any articles submitted to or accepted by the New Jersey Psychologist

Any opinions that appear in material contributed by others are not necessarily those of the Editors, Advisors, or Publisher, nor of the particular organization with which an author is affiliated.

Manuscripts should be sent to the Editor: Gianni Pirelli, PhD

E-Mail: gpirelli@gmail.com or NJPA Central Office E-Mail: NJPA@PsychologyNJ.org

Published by:

New Jersey Psychological Association

354 Eisenhower Parkway, Plaza I

Suite 1150

Livingston, NJ 07039

973-243-9800 • FAX: 973-243-9818

E-Mail: NJPA@PsychologyNJ.org Web: www.PsychologyNJ.org

New Jersey Psychologist (USPS 7700, ISSN# 2326098X) is published quarterly by New Jersey Psychological Association, 354 Eisenhower Parkway, Plaza I, Suite 1150, Livingston, NJ 07039. Members receive New Jersey Psychologist as a membership benefit. Periodicals postage pending at West Orange, NJ and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to New Jersey Psychologist, 354 Eisenhower Parkway, Plaza I, Suite 1150, Livingston, NJ 07039.

(N) Randy Bressler, PsyD

(N) Alan Lee, PsyD

(N) Nicole Rafanello, PhD

Parliamentarian: Joseph Coyne, PhD

Affiliate Caucus Chair: Rosalie DiSimone-Weiss, PhD

ECP Chair: Michelle Pievsky, PhD

NJPAGS Chair: Christopher Thompson, MA, EdS

CODI Co-chairs: Phyllis Bolling, PhD and Aida Ismael-Lennon, PsyD

Affiliate Representatives

Northeast Counties Association of Psychologists: Nansie Ross, PsyD

Essex/Union County Association of Psychologists: Susan Esquilin, PhD

Mercer County Psychological Association: David Krauss, PhD

Middlesex County Association of Psychologists: Tammy Dorff, PsyD

Monmouth/Ocean County Psychological Association: Tamara Latawiec, PsyD

Morris County Psychological Association: Randy Bressler, PsyD

Somerset/Hunterdon/Warren Psychological Association: Janie Feldman, PsyD

South Jersey Psychological Association: Daniel Lee, PsyD

Central Office Staff

Executive Director: Keira Boertzel-Smith, JD

Director of Professional Affairs: Judith Glassgold, PsyD

Senior Communications Manager: Christine Gurriere

Continuing Education & Event Coordinator: Ana DeMeo

Membership Services Coordinator: Jennifer Cooper

Fall 2019 1

27 In Memoriam

28 NJPA Sustaining Members

from

Council

Report

APA

Efforts

30 NJPA Advocacy

Morgan Murray, PhD

Ihave much to be thankful for. Though I am writing this in early September and still have almost 4 months left in my time as NJPA president, this will be my last column in the NJ Psychologist and I feel compelled to say thank you. First to the general membership, without whose involvement there is no NJPA. Thank you to everyone that served on an NJPA committee, task force, or participated in the leadership of your local affiliate organization. It has been an exciting year, an incredible opportunity, and a privilege to do my part to advance the profession of psychology in New Jersey and our association. No endeavor like this can be accomplished alone, and I was blessed with a tremendous leadership team in our Executive Director, Keira Boertzel-Smith, JD, our President-Elect, Lucy Sant’Anna Takagi, PsyD, and our Past-President , Stephanie Coyne, PhD. I would add to this support team the tireless dedication

President’s Message

of the executive board that includes our Parliamentarian, Joe Coyne, PhD and, of course, the tireless efforts of Central Office staff, Christine Gurriere, Ana DeMeo, and Jennifer Cooper.

We moved forward on traditional guild issues this year. A prime example of this is the progress on our bill to allow graduate students and early career individuals, working to meet the requirements for licensure, to include all pre-doctoral supervision hours toward their license, and to no longer require that any must be acquired post-doctorly. Another example is that the Committee on Legislative Affairs (COLA), under Barry Katz’s leadership, worked hard to increase the transparency of NJPA’s legislative efforts, so that our membership can stay abreast of what bills we are following and where we are focusing our resources.

We also focused on efforts to expand beyond traditional guild issues (Murray, 2019) and looked at what psychology can say and do regarding many of the significant social issues that are faced in New Jersey. The Committee on Diversity and Inclusion (CODI) formed a subcommittee, Immigration Emergency Action Group (IEAG) to

to the humanitarian crisis created by the separation of immigrant families detained at four detention centers within New Jersey. The IEAG will look to collaborate with other agencies in its efforts to address the mental health needs of detained individuals. We also issued statements and endorsed statements that were based on psychological principles and consistent with the NJPA mission. This allows NJPA to use psychological science to enter into, and contribute more broadly to, the dialogue on issues related to the psychological well-being of the diverse residents of New Jersey. We also continued to develop our collaboration with the New Jersey Association of Black Psychologists (NJABPsi) and the Latinex Mental Health Association of New Jersey (LMNANJ). Our collaboration is accomplished through an affiliation of co-equals called the Inter-Mental Health and Psychological Association Coalition (IMPAC). This expansion beyond traditional guild issues is part of the changing face of professional psychology. Thank you! ❖

Reference

Murray, Morgan (Summer 2019). Expanding the Definition of Guild.

New Jersey Psychologist 2

NJPA Association Life-Cycle

Keira Boertzel-Smith, NJPA Executive Director

In May 2019, the NJPA Central Office staff boxed up NJPA documentation from the 1930s through 2019, awards we received, NJPA past presidents and Psychologist of the Year plaques, desks and chairs used by past executive directors, directors of professional affairs, and staff, and boardroom furniture used by the current and past executive boards, committees, and staff for meetings and continuing education programs. A huge thank you to the Central office team, Christine, Ana, Jennifer, and Marion, for helping me with the grimy and back breaking work of cleaning out cabinets, closets, and the kitchen, hauling items to the dumpster, as well as researching and utilizing the needed vendors to make the move happen. Thank you to the NJPA Capital Improvement Workgroup Chair, Ken Freundlich, PhD, and commercial real estate advisor and broker, Mark Twentyman, Kingsbridge Realty Advisors, for their hours of time put in on the road with me during the NJPA commercial real estate hunt.

This extensive 2019 NJPA moving process caused me to pause and reflect on the NJPA life-cycles: birth through the mature operational stages. As in all association life-cycles, there is the eventual decline in interest in the association “as is” that will either result in the association’s death or rebirth. I can report that NJPA is in a rebirth stage, with all hands on deck to ensure a new and improved NJPA identity that matches the needs and expectations of the evolving membership populations. This rebirth is clearly felt with the physical 2019 NJPA Central Office move, and we will be taking full advantage of the new space to host bigger and better meetings, continuing education events, and social gatherings.

Less visible rebirth manifestations are the updating of our internal association management policies and internal efforts to account for our members’ changing advocacy and outreach expectations, as well as the evolving NJPA communications, continuing education, financial, membership, and technology needs. NJPA continues to grow the statewide “Road Show” where the NJPA/NJPAF leadership team travel around the state to various NJPA affiliate organizations, universities, institutions, Board of Psychological Examiners meetings, and legislative appointments to discuss our mission and goals, topics of interest for graduate students and early, mid- and late-career psychologists in all work settings, state and federal legislative and social advocacy priorities and efforts, and the NJPA relationship with the American Psychological Association. Central Office is working on behalf of NJPA/NJPAF leadership, committees, and our members to promote the use of virtual meeting participation so members can incorporate NJPA and NJPAF into their busy lives.

In my current role as the chair of the APA Council of Executives of State, Provincial and Territorial Psychological Associations (CESPPA), I am working hard to advance the good reputation of New Jersey and NJPA, as well as promoting our rebirth efforts at the national level. On behalf of NJPA, I accepted APA CEO, Dr. Arthur Evans’ invitation to travel to state associations to talk about professional development of psychologists and the future of psychology (September 20, 2019 NJPA visit and CE program). In October, I organized a State, Provincial, and Territorial Psychological Association’s (SPTA) membership training with APA Chief of Strategic Implementation and Membership, Ian King, MBA, to discuss retention, recruitment, understanding member populations, and the relationship between SPTA and APA membership in these changing times for association membership. We are working to get Bradley K. Steinbrecher, JD, a representative from the APA Legal and Regulatory Department to host a continuing education program on HIPAA. CESPPA

is working to strengthen the relationship with the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB) leadership and the APA Continuing Education Committee to make sure that our associations stay up to date with their ongoing efforts. Also on behalf of NJPA, I have been sure to make use of APA’s Legal and Regulatory Affairs staff as valuable resources on NJPA advocacy and regulatory issues such as telepsychology, Medicaid reimbursement, and the New Jersey Licensure Act.

I look forward to carrying these growth opportunities and rebirth efforts into 2020 to ensure NJPA stays relevant to the profession, psychologists, and the public. I acknowledge and respect the around-the-clock work of the NJPA executive board, chairs, past NJPA leaders, NJPA staff, and members who all carry the load of the evolving association work, and I appreciate suggestions to improve my work as executive director.

This association provides, for all of us, invaluable lessons about life-cycles including rebirth, professional and personal grit, humility, and the need for healthy teamwork. NJPA should be very optimistic about its future! ❖

D E C 6 Save the Date!

Fall 2019 3

Research Briefs: Fall 2019 CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY

Treatment/Diagnostic

Goghari & Harrow (2019). Anxiety symptoms across twenty-years in schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 275, 310-314.

Goghari and Harrow examined the trajectory of self-reported and somaticrelated anxiety for patients diagnosed with Schizoaffective (n = 43), Bipolar (n = 47), and Major Depression (n = 109) Disorders, to explore if early reports of anxiety predicted later outcomes. Patients were assessed longitudinally, i.e., six times over 20 years. The authors found that self-reported anxiety in earlier years of illness was greater for those with Schizoaffective Disorder and Major Depression than those with Bipolar Disorder, but the three groups were similar with respect to their experience of anxiety-related symptoms across 20 years. For all patients, self-reported anxiety in early years predicted a recovery period and lower global functioning in the future.

Krajniak, Pievsky, Eisen, & McGrath (2018). The relationship between personality disorder traits, emotional intelligence, and college adjustment. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1160-1173.

Working with college first-year students (n = 246), Krajniak et al. examined the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI), personality disorder (PD) traits, and college adjustment to understand the reasons and protective factors related to dropout rates. They found that PD symptoms and EI were inversely related, and unique patterns of association emerged between PD clusters and EI deficits. Both variables were related to adjustment, but EI did not moderate the relationship between PD and adjustment, as previously theorized, but the study proposed a mediating model for future research.

Kudinova, Woody, James, & Burkhouse (2019). Maternal major depression and

synchrony of facial affect during motherchild interactions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 4, 284-294.

Kudinova et al. examined synchrony of facial displays of affect during positive and negative mother-child interactions (n = 341 dyads) to understand how it may be impacted by maternal history of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Maternal MDD history increases children’s risk of developing depression. Facial electromyography (EMG) indexed mother and child facial affect. Maternal history of MDD was associated with reduced synchrony of positive affect; reduced synchrony of positive affect was associated with an increase in the child’s self-reported sad affect after the interaction. Therefore, positive affect in motherchild interactions may be disrupted in families with maternal MDD history.

Sibrava, Bjornsson, Perez Benitez, Moitra, Weisberg, & Keller (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder in African American and Latinx adults: Clinical course and the role of racial and ethnic discrimination. American Psychologist, 74, 101-116.

Sibrava et al. explored the relationship between experiences of discrimination and risk for developing Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among African American and Latinx adults with Anxiety Disorders. This 5-year longitudinal study found that African American and Latinx participants had a 35% and 15% probability, respectively, of achieving full recovery and remission from PTSD symptoms after intake. Frequency of experiences of discrimination significantly predicted PTSD diagnostic status but did not predict any other anxiety or mood disorder. Thus, racial/ethnic discrimination may play a role in the development of PTSD and contribute to its chronic course.

Psychological Assessment

Helle & Mullins-Sweatt (2019). Maladaptive personality trait models: Validat-

ing the five-factor model maladaptive trait measures with the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 and NEO Personality Inventory. Assessment, 26, 375-385.

In the context of a convergent validity study, Helle & Mullins-Sweatt examined five-factor model (FFM) maladaptive trait scales specific to personality disorders in relation to the respective general personality traits of the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-PI-R) and the pathological personality traits of the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5). Results suggested that the FFM maladaptive trait scales converged with corresponding NEO-PI-R and PID5 traits. This provides validity-related evidence for these measures as extensions of general personality traits and their relation to pathological trait models as well as support for the theoretical basis of utilizing the FFM to describe DSM-5 personality disorders.

Reis, Namekata, Oehlert, & King (2019, March 14). A preliminary review of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDIII) in veterans: Are new norms and cut scores needed?. Psychological Services. Advance online publication.

Reis et al. examined Veterans Health Administration (VHA)-specific use of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) to establish normative data within this population and assess its psychometric properties (n = 152,260). These BDI-II scores were compared against Beck and colleagues’ original sample, normed on adult psychiatric outpatients and college students, as well as across veteran subgroups. Factor analyses found a 2-factor model provided best fit, supporting Beck’s original solution. However, veterans scored significantly higher on the BDI-II than the original comparison groups across diagnostic categories which may require future investigation for its use with veteran populations.

New Jersey Psychologist 4

Psychiatry/Pharmacotherapy

Abbasi, J. (2017). Ketamine minus the trip: New hope for treatment-resistant Depression. JAMA, 318(20), 1964.

Administering one dose of ketamine can cause an extreme antidepressant impact for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) without having side-effects of hallucinations. Current research is concentrating on ketamine as a treatment method for TRD and major depressive disorder (MDD) with imminent risk of suicide. The variety of traditional medications used to treat depression work solely on the monoamine neurotransmitter system and only treat a small number of patients, which results in low response to treatment and high remission rates. Clinical trials determined that ketamine is a valuable element in treatment-resistant depression by creating shorter response to treatment and lower remission rates, and it is effective for patients who have been unsuccessful with other antidepressant options.

Limandri, B. J. (2019). Pharmacogenetic testing: Why is it so disappointing? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 57(4), 9-12.

The benefits in current pharmacogenomic testing include reduced pricing, and in susceptible populations such as children and older adults, the testing can minimize polypharmacy or inaccurate drug trials. The limitations occur from the sole concentration on the metabolism of drugs. Pharmacogenomic testing cannot predict all possible outcomes that

a medication may have on an individual. As a result, clinicians’ question whether they should supply pharmacogenomic testing for their patients as standard protocol. Weighing the patient’s and their family’s medication use history against the strengths and weaknesses of pharmacogenomic testing can assist in determining an answer.

O’Brien, McNeil, et al. (2017). New fathers’ perinatal depression and anxiety— treatment options: An integrative review. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 863-876.

The authors created a conceptual model consisting of four categories in order to better understand paternal perinatal depression (PPND) and effective treatment methods. The first category pertains to the father’s responsibility in helping their significant other with perinatal depression (PND). The second factor suggests that the concept of perinatal mental health should be recreated to be viewed as a family concern as opposed to strictly a maternal issue. The third category concentrates on the male’s conversion into fatherhood, the absence of guidance, and the idea that father-oriented therapeutic methods are important. The fourth includes how fathers with PPND can consider the treatment options including cognitive behavioral therapy, group work, e-support strategies, and supplying a safe atmosphere designed using father-specific models of care.

Koek, Roach, Athanasiou, van ‘t WoutFrank, & Philip. Neuromodulatory treat-

Classified Ads

ments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 92(8), 148-160.

The is a review of published data involving the use of neuromodulation in PTSD. This study summarizes that the primary components include neural circuits associated with threat-sensitivity, safety learning, emotion regulation, and contextual learning. There is an increasing amount of technology-based neuromodulation methods that allow for concentrating focus on abnormal limbic circuitry, while previous approaches to neuromodulation were more non-specific.

Bushnell, Gaynes, Compton, Dusetzina, Brookhart, & Stürmer (2018). Incidence of mental health hospitalizations, treated self-harm, and emergency room visits following new anxiety disorder diagnoses in privately insured U.S. children. Depression and Anxiety, 36(2), 179-189.

In this large-scale study, the researchers identified 198,450 children from 20052014 and followed them for two-years following an initial outpatient diagnosis of an anxiety related disorder. Authors found that following this initial diagnosis, 2.0% of children had a mental health–related hospitalization, 0.08% inpatient hospitalization for self-harm, 1.4% had an anxiety-related ER visit, and 20% had any ER visit. The incidence was highest in older children with baseline comorbid depression. These incidence rates were significantly higher compared with children without an anxiety diagnosis. ❖

The NJ Psychologist accepts advertising of interest to the profession. The minimum rate for Classified Ads is $75 for up to 50 words, $1 for each additional word. For display ad information, email inquiries to NJPAcg@PsychologyNJ.org ATTN: Christine Gurriere, or call 973-243-9800. The NJ Psychologist is mailed on or about the 10th of February, May, and November. Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement by NJPA.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGIST/EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST/PSYCHOLOGIST

NEUROPSYCHOlOGICAL/IQ TESTING

Central NJ: Monmouth and Ocean County.

GREAT OPPORTUNITY!: for Part Time, Per Diem, Extra Income. Neuropsychological Testing Administration; Experience with Concussions, Auto Accidents and Work Injuries a plus.

(*) Bilingual (English/Spanish) preferred as well.

Long-Term, Stable Employment. Excellent working conditions. State Licensure/Permit preferred. Please e-mail your resume to: NRABP@AOL.com

Fall 2019 5

EDUCATION AFFAIRS

2019 Critical Conversations in Continuing Education for New Jersey Psychologists

Internal Efforts

The New Jersey Psychological Association (NJPA) is approved by the American Psychological Association (APA) to sponsor live and homestudy continuing education for psychologists. NJPA maintains responsibility of the live and homestudy NJPA and NJPA co-sponsored programs and content. We take our relationship with APA and our APA sponsorship seriously and strive to continue to work with APA in our shared ongoing commitment to excellence in continuing education.

APA as a CE Resource

In August, NJPA received a copy of a special issue of the APA Professional Psychology: Research and Practice dedicated to conversation around continuing education from Director of the APA Office of CE in Psychology, Greg Neimeyer, PhD. The publication addresses topics such as continuing education best practices, the relationship between continuing education and professional competence, and assessment and outcomes associated with continuing education and interprofessional continuing education. NJPA will continue to use APA resources, such as this recent publication, to further grow the NJPA continuing education programming and standards. NJPA Executive Director and APA Council of Executives of State, Provincial and Territorial Psychological Associations (CESPPA) Chair, Keira Boertzel-Smith, is currently working at the national association level to further define and develop the role of the CESPPA liaison to the APA Continuing Education Committee. The goal of this CESPPA liaison role is to ensure that all state associations understand the APA continuing education sponsorship approval and reporting process, and that they have the best chance at maintaining or gaining APA sponsorship approval.

Internally, NJPA created the NJPA Council on Continuing Education Affairs (CoCEA), pursuant to the NJPA mission and following the NJPA strategic plan goals, that is charged with managing NJPA’s continuing education development and program review. NJPA continues to find ways to use technology enhancements and platforms for program review, event management, and organizational tools for continuing education tracking. NJPA continuing education programs are created and provided for New Jersey psychologists to be applied towards the mandatory 40 credits of continuing education related to the practice of psychology; four credits of the 40 credits in topics related to domestic violence and one credit of the 40 credits addressing the risks and signs of opioid abuse, addiction, and diversion.

Statewide and Virtual Programs

NJPA and NJPA co-sponsored live programs are held across the state of New Jersey: North, Central, and South. NJPA moved its central office space to Livingston, NJ, partially to have access to larger continuing education venue space at a discounted cost to NJPA members. NJPA also provides homestudy learning options for credit in most of our quarterly NJ Psychologist journal publications and will host upcoming recorded programs. So far in 2019, NJPA hosted, or co-sponsored, approximately 35 live continuing education programs and four homestudy learning options.

How NJPA and NJPA Co-Sponsored Programs are Unique

NJPA has the challenge of ensuring that we remain competitive and relevant in the continuing education market for the profession of psychology. What NJPA and NJPA co-sponsored continuing education programs can uniquely offer you:

1. NJPA programs take advantage of our relationship with APA, such as the September 20, 2019 program An Emerging Framework for Healthcare: Opportunities for Psy-

chologists - A day with APA CEO, Arthur C. Evans Jr., PhD.

2. NJPA looks to our current NJPA advocacy initiatives to create programs related to current New Jersey advocacy issues, such as our planned 2020 continuing education programs on the New Jersey Duty to Warn Law, New Jersey Telemedicine, and the opioid article in this journal.

3. NJPA strives to highlight our collaborative partnership in the New Jersey Inter-Mental Health and Psychological Associations Coalition (IMPAC) through continuing education programs. The goal for IMPAC is for the New Jersey Chapter Association of Black Psychologists (NJABPsi), the Latino Mental Health Association of New Jersey (formerly the Latino Psychological Association of New Jersey), LMHANJ, and NJPA to join together as equal partners to contribute their unique educational acumen, expertise, experience, and perspectives to obtain synergy as a resource to promote equality in mental health care and to zealously advocate for the mental health needs for the diverse population of the state of New Jersey. An example of our efforts was the April 12, 2019 IMPAC Shine a Light on Multicultural Mental Health Awareness in New Jersey continuing education program.

4. NJPA and NJPA co-sponsored continuing education programs are produced, reviewed, and approved by the NJPA CoCEA Programming and Review Committees with the full NJPA membership in mind. I thank our NJPA CoCEA Programming, Homestudy, and Review Committees for their hard work and dedication to developing unique and customized continuing education opportunities that impact psychologists in New Jersey. Their hard work ensures that New Jersey

New Jersey Psychologist 6

COUNCIL ON CONTINUING

Dennis Finger, EdD, Council on Continuing Education Affairs (CoCEA) Chair

psychologists are enhancing their educational growth and improve their practices for their patients.

Council Members: Past-Chair, Marc Gironda, PsyD; Past Past-Chair, Phyllis Lakin, PhD; Ray Hanbury, PhD; Mark Lowenthal, PsyD; Nathan McClelland, PsyD; Leah Anne McGuire, PhD; Sharon Ryan Montgomery, PsyD; Membership Chair, Randy Bressler, PsyD; Treasurer, Daniel DaSilva, PhD; CODI Representatives, Susan Esquilin, PhD and Abisola Gallagher, EdD.

Programming Committee: CoChairs, Leah Anne McGuire, PhD, and Sharon Ryan Montgomery, PsyD; Phyllis Bolling, PhD; Caitlin Colandrea, PsyD; Peter DeNigris, PsyD; Cassandra Faraci, PsyD; Sangeetha Nayak, PhD; Marcy Pasternak, PhD.

Review Committee: Co-Chairs, Ray Hanbury, PhD and Mark Lowenthal, PsyD; William Coffey, PsyD; Julia Conrath, PhD; Osna Haller, PhD; Martin Krupnick, PsyD; Denise Ricciardi, PsyD; Nancie Senet, PhD.

Homestudy Committee: Chair, Nathan McClelland, PsyD.

On behalf of COCEA, we express our appreciation to our Executive Director, Keira Boertzel-Smith, JD, and to our CE Coordinator, Ana DeMeo and all of the NJPA staff for all of the hard work they do for NJPA’s continuing education. We also thank our current NJPA President, Morgan Murray, PhD, for all of his help and support during 2019.

5. Lastly, attendance at live NJPA and NJPA co-sponsored programs offer opportunities to network with

your New Jersey peers before, during, and after our continuing education programs.

We hope to see you soon at an NJPA or NJPA co- sponsored continuing education program. Learn, stay updated on New Jersey laws and regulations, meet your mandatory continuing education requirements, and network with your peers! ❖

Fall 2019 7

As featured in The New York Times Magazine! Anxiety, OCD, Intrusive Thoughts? We Get It! We Specialize in the Treatment of Adolescent Anxiety and OCD. Located in New Hampshire’s Upper Valley, we are a short-term, residential treatment center. Contact Admissions: 603-989-3500 www.mountainvalleytreatment.org

Continuing Education Requirement: Why Is There an Emphasis on Addressing Diversity in Every Program?

diversity is a critical consideration for all of us for two major reasons.

Susan Cohen Esquilin, PhD

CE Diversity Requirement

Last year, NJPA received a fiveyear authorization from APA to grant psychology continuing education (CE) credits. This was a major accomplishment, as the application for this authorization was detailed and complex, and not all applicants, including other state psychological associations, received such authorization. Among other requirements, NJPA had to demonstrate to APA that issues of diversity would be addressed in every program or publication for which we would grant CE credits. In addition, when APA reviews our programs at annual intervals, NJPA must present evidence that we did what was required, i.e., that issues of diversity were, in fact, addressed. Over the last few decades, APA drafted and redrafted guidelines for work with a variety of demographic groups. Most recently, the importance of attention to diversity has been underscored by new APA multicultural guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2017) and guidelines on practice with boys and men (American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group, 2018), as well as work this year in APA on the development of guidelines for work with people of low income and economic marginalization and of guidelines related to race and ethnicity.

Some of our colleagues have questioned both the need for a requirement about addressing diversity in every continuing education endeavor, as well as our routine inquiry in the evaluations of each presenter at the end of every program about whether each presenter met this requirement. Some feel this attention to the issue of diversity is excessive or irrelevant. However,

Addressing

Diversity Furthers the Scientific Basis of Our Professional Work

Psychology views itself as a science, and applied psychology prides itself on using research-based evidence as the undergirding of its assessment and treatment interventions. When we learn a new intervention technique, we want and need to hear about the evidence that supports its usefulness. The question is whether the individuals with whom this technique has been used represent our client in significant ways. Has this technique been examined with clients of a variety of racial or ethnic backgrounds, including the background of our specific client? Have studies found a difference in the way men and women respond to this technique? If the subjects who have been studied are primarily White, middle class Americans, should we try the technique anyway on a client who is different from that demographically? What might we want to consider if we apply this technique to a member of a group who has not been considered in any of the research? So, the current requirement for a program approved for CE is that, prior to the program, the presenter should research the question of the characteristics of the people on whom this technique has been developed and studied. And, in the absence of available research, the presenter should raise for consideration by participants the issues that they might expect would arise if the technique is used with a person from a demographic group that is not part of the sample studied. Similarly, a discussion about a new assessment instrument should make clear who was in the normative sample. There will always be limitations regarding this question, and those limitations should be identified. Those limitations may include the complete absence of certain groups (immigrants are often omitted) and the underrepresentation of certain groups

as compared with their numbers in the population (this has often happened regarding Black people). In addition, a new assessment should report whether there are differences in how the various groups performed on the assessment instrument and provide different tables for each group or make suggestions for how to adjust for such differences in scoring. The PAI manual, for example, points out that a difference is found between White and Black participants in the standardization sample regarding only the paranoia scale. The manual discusses the likely reason for that difference and recommends a strategy for adjusting for it. Any of these shortcomings should make us cautious about relying on such an instrument for conclusions about people who are inadequately accounted for in the validation studies, and anyone presenting about a new technique should be calling attention to those limitations. Again, it would be useful in a CE presentation to then engage in a discussion with participants about what further research is needed and/or about how to use the assessment technique cautiously.

Importance of Awareness of Diversity on Clinical Rapport

New Jersey is one of the most diverse states in the United States with regards to ethnicity and religion, so the issue of diversity is particularly relevant for professional work in New Jersey. Estimates made in late 2018 indicated that, racially, New Jersey is 68.1% White, 13.5% Black, 9.2% Asian, 6.4% other races, 2.5% two or more races. Almost 40% of the population speak languages other than English, with Spanish as the most common non-English language spoken by 16.4% of the population. New Jersey is the state with the second largest Jewish and Muslim populations. It has the most Peruvians, the second largest population of Cubans, with very high numbers of Portuguese, Brazilians, Arabs, Chinese, and Italian Americans. (New Jersey Population 2019, 2018).

New Jersey Psychologist 8

Representative

CE

CODI

1

Credit

The issues raised by diversity are omnipresent, whether we are aware of them or not. A lack of awareness on our part can easily disrupt developing therapeutic alliances with clients. The clients we evaluate and treat represent a vast array of human differences based upon a variety of variables, including race, gender, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, ability status, immigration status, and developmental stage. In addition, we are increasingly recognizing the importance of intersectionality, e.g., how race and gender may intersect to produce significant differences in the challenges people face, in how people experience the world, and in the difficulties they present. The experiences and difficulties of White women and Black women may be very different in significant ways, so it may not be sufficient to understand something about women or something about Black people to have a more nuanced understanding of the status of being a Black woman.

Some differences are obvious when we look at a client, but many differences are invisible. We learn about them only if we are open to hearing about them. If we do not entertain the possibility that this client has a significant hidden identity that is crucial to understanding the client, we may never hear about it and the client may, in fact, simply withdraw from treatment because the client senses that we are closed to his/her experience. These hidden identities may include membership in a subculture that endorses activities that are alien or unfamiliar to the psychologist or that the psychologists never even considered might exist (e.g., a gun subculture).

Conclusion

As individual psychologists, and as a profession, we are constantly learning. As we recognize the many ways that clients may differ from one another, we must learn to integrate this recognition into our work. If our treatment and assessment methods are not built on research inclusive of people from different backgrounds, then our work is limited in its applicability and effectiveness. The new CE requirement will broaden the scope of both our sensitivity to what we do not know as well as increase our

knowledge and skills about what the research has already found. Both our growing skills and sensitivity will improve our competency as individual clinicians and the esteem in which the public holds our profession. ❖

References:

American Psychological Association (2017). Multicultural Guidelines: An Ecological Approach to Context, Identity, and Intersectionality. Retrieved from <http://www.apa.org/about/policy/ multicultural-guidelines.pdf>

American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group. (2018). APA guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men. Retrieved from <http://www.apa.org/about/policy/ psychological-practice-boys-menguidelines.pdf>

New Jersey Population 2019 (2018, November 30). Retrieved from <http://worldpopulationreview.com/ states/new-jersey-population/>

About the Author

Susan Cohen Esquilin, PhD, is in independent practice. Trained as a clinical and developmental psychologist, she currently focuses her practice on forensic issues. Dr. Esquilin is president of the Essex-Union County Association of Psychologists, a member of the NJPA Committee on Diversity and Inclusion, co-chair of the Immigration Emergency Action Group, and a member of CoCEA (Council on Continuing Education Affairs).

Continuing Education Instructions: Visit <www.psychologynj.org> and find the CE Homestudy Library link under the Learn tab. This will take you to the online library where you will find the article and evaluation.

Fall 2019 9

When a Client Dies by Suicide

by the same provisions for living patients set forth in N.J.A.C. 13:428.3, 8.4, and 8.5; and

Sarah Dougherty, PsyD Ethics Committee Member

What happens when a client dies by suicide?

Hopefully you never experience such a loss. However, data shows that a therapist’s odds of losing a client to suicide, at some point in his or her career, are at least one in four, perhaps higher. And if a therapist works in a group practice or hospital setting with other therapists, the likelihood increases that, at some point, they will know a colleague who loses a patient.

What would you do?

Losing a patient to suicide is perhaps among a therapist’s greatest fears. For most clinicians, it is the outcome we dedicate our careers toward avoiding, the “termination” universally dreaded. The basic risk management considerations are learned early in clinical training: Alert and communicate with your supervisor, if you have one. Notify your insurer. Secure the client file. Do not, under any circumstances, alter the records. Each of these recommendations seems to underscore the perceived need to batten down the hatches, keep quiet, and hope for the best.

The statutes regarding confidentiality following a client’s death are equally clear. When a client dies, regardless of the cause, the therapist is bound by the same limits of confidentiality as for a living client.

Confidentiality survives the client’s death.

In the case of a client’s death:

1) Confidentiality survives the client’s death and a licensee shall preserve the confidentiality of information obtained from the client in the course of the licensee’s teaching, practice, or investigation;

2) The disclosure of information of a deceased client’s records is governed

3) A licensee shall retain a deceased client’s record for at least seven years from the date of last entry, unless otherwise provided by law.

Therapist-client confidentiality is among the cornerstones of ethical practice. Confidentiality engenders trust and reassures the client it is safe to talk about deeply personal matters without fear of exposure. However, in the aftermath of a client suicide, does “confidentiality” cast an overly legalistic shadow that potentially cultivates distrust between the therapist and the deceased client’s survivors?

Not surprisingly, following a suicide, when grieving family members know or learn of the deceased client’s mental health treatment history, they may reach out to the psychologist (and other treatment team members) as they struggle for some explanation for the death of their loved one. Often, family members are in shock, highly distraught, and possibly angry. However, unless the now-deceased client previously authorized the psychologist, in writing, to communicate or share information with the caller, the clinician is legally prohibited from sharing client information or even divulging the existence of a professional relationship with the deceased. Nor may the therapist reach out to the family, post-suicide, to express condolences or offer support. There are two exceptions available to survivors of the deceased: 1) A copy of the clinical record must be provided in response to a written court order signed by a judge; or 2) A copy of the clinical record must be provided in response to a written request from the documented executor of the deceased client’s estate, who is recognized as the deceased patient’s living “stand-in.” *

Records maintained as confidential pursuant to N.J.A.C. 13:42-8.1(c) shall be released:

2) Pursuant to an order of a court of competent jurisdiction;

3) Except as limited by N.J.A.C.

13:42-8.4, upon a waiver of the client or an authorized representative to release the client record to any person or entity, including to the Violent Crimes Compensation Board.2

The immediate aftermath of a suicide is emotionally charged and chaotic. Under the circumstances, a psychologist’s professional obligation of confidentiality may be interpreted by grieving family as stonewalling. Presumed “secrets” maintained by the treating therapist may take on disproportionate importance for the survivors, and client records, once obtained, may offer disappointingly little insight or comfort to the grieving family. Is confidentiality in the wake of a client suicide, followed to the letter, potentially harmful?

At the same time, the therapist may feel unduly burdened by his or her own feelings around the client’s death. Therapists are people, too, and feelings about a client’s suicide can be profound. It is not unusual, post-suicide, for a therapist to experience guilt, self-doubt, or shame, or to question his or her own clinical competence even when good care was provided. There may be financial concerns, fear of legal repercussions, worry about loss of professional reputation, and a reluctance to seek support from colleagues.

Who benefits from confidentiality, post-suicide?

At best, confidentiality may briefly postpone communication between the therapist and suicide survivors while the requisite release is obtained. This hiccup may give the therapist a bit more time to prepare for the encounter. More likely, however, the delay heightens anxiety for both the family and therapist and may further erode already dwindling trust.

While grief of any kind is painful, grief after suicide can be particularly complex. During “ordinary” grief, though there may be regrets, the primary tasks of grieving involve coming to terms with the absence of the person, and developing a new “relationship” with the memory of the person. In grief after suicide, the cause of death frequently eclipses memories of

New Jersey Psychologist 10 “It’s Confidential…”

ETHICS UPDATE

the life of the deceased, such that normal grieving is obstructed. Depending upon a survivor’s proximity to the actual suicide scene, the act of the suicide may constitute additional, bona fide trauma. Perceptions that a therapist is not being forthright may pose yet another barrier to processing of grief.

Perhaps there is an argument to be made for revisiting and possibly reconsidering the current parameters of confidentiality following client suicide. Potential benefits of greater openness between therapist and survivors include minimizing further trauma, reducing or deterring potential animosity, and promoting healthy grieving. Whereas it is not the therapist’s responsibility to treat family members (that would be frankly unethical), a therapist trained in grief triage could offer support and referrals to bereaved family, such that instead of being a lightning rod, the therapist could be a

resource. Being contacted by family postsuicide may be highly stressful, particularly when the therapist is feeling flummoxed about how to respond. However, training around post-suicide protocol could help prepare the therapist for survivor reaction, offer tips around self-care, and underscore the value of the therapist’s simply being present for the family. Also, hearing survivors’ perspectives about the deceased could help the therapist reach new understanding of the circumstances in which the client chose to take his or her life.

And finally, greater openness between therapist and survivors, post-suicide, is not tantamount to “spilling the beans.” Therapists are highly trained to exercise discretion and use good clinical judgment in all their professional endeavors. If confidentiality between a therapist and living client is intended to promote trust, perhaps a more open, more compassionate,

less legalistic posture with survivors in the aftermath of a client suicide could better serve us all. ❖

References

*Records also must be released 1) If requested or subpoenaed by the Board or the Office of the Attorney General in the course of any Board investigation; or 4) In order to contribute appropriate client information to the client record maintained by a hospital, nursing home, or similar licensed institution which is providing or has been asked to provide treatment to the client.

2NJ Administrative Code, Title 13, Law and Public Safety, Chapter 42, Board of Psychological Examiners (Last Revision Date 8/2018)

WELCOME NEW MEMBERS!

Licensed 5+ years

Valerie Brooks-Klein, PhD

Stacey Cohen-Meissner, PhD

Joseph Cooper, PsyD

Marilyn Denninger, PhD

Amy Dodds, PhD

Jennifer D’Ostilio, PsyD

Guillermo Gallegos, PhD

Roger Goddard, PhD

Paul Groenewal, PsyD

Michael Lindemann, PhD

Jamie Messina, PhD

Jami Messina, PhD

Elizabeth Midlarsky, PhD

John Miele, PhD

Thomas Morgan, PsyD

Maureen Nallly, PhD

Joseph Perzel, Jr, PsyD

Donna Rukin, PhD

Sandra Sabatini, PsyD

Michael Schubert, PhD

Eris Schleifer, PhD

Francis Schwoeri, PhD

Michael Shrem, PsyD

Karen Skean, PsyD

Margaret Van Sciver, PhD

Jennifer Weberman, PsyD

Licensed 2-5 years

Karen Donahue, PsyD

Mihaela Epurianu Dranoff, PhD

Michael Gross, PsyD

Aaron Gubi, PhD

Kristine Hodshon, PsyD

Jennifer Kennedy, PsyD

Natalie Nageeb, PsyD

Andrea Tesher, PsyD

Licensed less than 2 years

Kevin Giangrasso, PsyD

Corrinne Kalafut, PsyD

Amy Origlieri, PhD

Esther Reidler, PhD

Melany Rivera-Maldonado, PhD

Joshua Tal, PhD

2nd year Post-Doctoral

Juliana Claps, PsyD

Scott Thien, PsyD

Associate Member

Rachel Kalinsky, MEd

Students

Laura Betheil, MSEd

Cindy Chang, BA

Docia Demmin, MA

Mike Dikenson, BA

Beth Granet, PsyD

Gabrielle Guzman, PsyM

Molly Kammen, MA

Victoria Kealy

Marina Oganesova, MA

Yael Osman, MA

Lauren Rosenberg, MA

Phoebe Shepherd, PsyM

Anna Stadtmueller, MA

H. Gemma Stern

Fall 2019 11

PsyD program in Clinical Psychology

Our full-time, five-year, scholar-practitioner training program is accredited by the American Psychological Association When you enroll in the PsyD program at William Paterson University of New Jersey (WPUNJ), your studies will integrate academic coursework, supervised clinical training, and research experience in a small, supportive community of peers and mentors. Current and prospective students commonly say they choose WPUNJ because of the strong sense of community and care among the dedicated students and faculty.

A distinguished faculty of active scholars and practitioners, who have diverse interests in both clinical practice and research, will support your training in evidence-based assessment and intervention. The faculty offers individualized attention in our state-of-the-art complex that includes teaching and research facilities, as well as a psychology clinical training suite, featuring recording and monitoring equipment.

WPUNJ PsyD CORE FACULTY:

Michele Cascardi, PhD: Research aims to improve measurement of adolescent relationship abuse from early adolescence into young adulthood. Her work also focuses on bystander education to prevent sexual and relationship violence, as well as trauma, attachment, and social information processing theories that contribute to risk for aggressive behavior in romantic relationships. Dr. Cascardi is a consulting forensic psychologist.

Megan Chesin, PhD: Specializes in the study of impulsive-aggressive behavior and third-wave behavioral treatments, such as Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Dr. Chesin is a consulting psychologist on clinical trials testing treatments for depression and suicide prevention, providing supervision to

therapists and conducting psychosocial assessments.

Jan Mohlman, PhD: Research and clinical work focus on the etiology, course and treatment of anxiety disorders across adulthood (particularly in older adults), cognition and emotion, and in investigating brain-behavior relationships in psychopathology. Dr. Mohlman is a practicing clinician.

Bruce Diamond, PhD: Specializes in clinical neuropsychology, neurorehabilitation, and cognitive neuroscience. His research uses neuropsychological assessments and computer-based measures including brain imaging/autonomic techniques with neurologic, neuropsychiatric, and neurodevelopmental populations. Dr. Diamond is a practicing neuropsychologist.

Aileen Torres, PhD: Research interests include multicultural competency, trauma-informed treatment, child abuse/ neglect, cultural adaptation of recent immigrants, and ethnic identity development. Dr. Torres is a practicing clinician conducting individual and family therapy, as well as immigration-related and child maltreatment forensic psychological evaluations.

Greg Bartoszek, PhD: Investigates cognitive, psychophysiological, behavioral, and motivational aspects of emotions and affective psychopathology. His research interests include comorbidities among mental health problems and mechanisms of change in evidence-based psychotherapies. Dr. Bartoszek is a practicing clinician.

The program has been carefully designed to prepare graduates for pursuit of clinical, teaching, or research positions in a wide variety of professional settings. Graduates of the PsyD program who wish to become licensed clinical psychologists must additionally pass a national examination and fulfill all state licensing requirements.

Graduate assistantship opportunities are available to select students with outstanding credentials. The assistantships provide tuition waivers and a stipend. Students may obtain a Master’s in Clinical and Counseling Psychology en route to the PsyD degree. After earning a master’s degree, qualified graduate students are eligible to teach as adjunct faculty to gain undergraduate teaching experience and earn additional financial support.

For more information on our PsyD program in Clinical Psychology, please visit our website: <https://wpunj.edu/ cohss/departments/psychology/psyd/>.

Students may apply for admission through PsyCAS, the Centralized Application Service for graduate study in psychology: <https://psycas.liaisoncas. com/applicant-ux/#/login>.

Drs. Michele Cascardi, Program Director (cascardim@wpunj.edu) and Uzma Ali (aliu@wpunj.edu), Graduate Admissions Coordinator, are also available by email or phone (973) 7203500 to answer your questions and provide more information.

Master’s program in Clinical and Counseling Psychology

The Master’s program in Clinical and Counseling Psychology at William Paterson University in Wayne, NJ prepares students for careers as Master’s level mental health clinicians, researchers, or to work in various human services settings. The curriculum provides a solid grounding in both theories and interventions. We emphasize clinical skills, ethical responsibility, cultural competency, self-awareness, and current body of knowledge in the scientific, methodological, and theoretical foundations of practice. In addition, we are committed to social justice work and multiculturalism to serve disadvantaged or marginalized groups in our society. Our program faculty members are

New Jersey Psychologist 12

Graduate Program WPU

licensed psychologists actively involved in clinical practice and research in the field. They have research and clinical strengths in health psychology, trauma, resilience, racial and ethnic socialization, bilingual counseling with immigrant populations, school-based interventions, and neuropsychology. ❖

Citations of Recent Publication by WPU faculty and students

Ma, P-W., & Shea, M. (2019). FirstGeneration College Students’ Perceived Barriers and Career Outcome Expectations: Exploring Contextual and Cognitive Factors. Journal of Career Development. Online First: https://doi. org/10.1177/0894845319827650

Margolis, M. & Austin, J. & Wu, L. & Valdimarsdottir, H. & Stanton, A. & Rowley, S…& Rini, C. (2019). Effects of Social Support Source and Effectiveness on Stress Buffering After Stem Cell Transplant. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 10.1007/s12529-019-09787-2.

Raghavan, S. & Sandanapitchai, P. (2019). Correlates of Resilience to Trauma in a Multinational Sample. Frontiers in Psychology: Cultural Psychology, doi: 10.3389/ fpsyg.2019.00131

Raghavan, S. (2018). Cultural Considerations in the Assessment of Survivors of Torture: A Review. Journal of Im-

migrant and Minority Health, doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0787-5.

The MA in Clinical and Counseling Psychology program is accredited by the Masters in Psychology and Counseling Accreditation Council (MPCAC) under the psychology academic standards for the period of July, 2015 through July, 2025. The priority deadline is March 1st for the Fall semester but applications will be accepted until May 1st. Fall enrollment only. To Apply, please visit PSYCAS.

Les Barbanel, EdD has a new book Return to Harmony: Conflict Management for Couples that can be purchased online from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Archway Publishing. The book, intended for both professional and non-professional audiences, introduces the concept of “couple intelligence (CQ)” and provides an assessment scale in the appendix that yields a CQ score, analogous to traditional measures of intelligence (IQ). The book is reviewed in the Spring issue of NJ Psychologist, Vol. 69, and is targeted for both the professional and non-professional reader.

Ruth Lijtmaer, PhD presented the paper: Marie Lang, Her Life and Work in the panel: Liberation Psychology and Psychoanalysis as Social Revolution: The Clinical and Community Contributions of Marie Langer. International Psychohistory Association (IPA) Conference : The Intersection of Psychology and History: The Contributions of Michael Eigan to Human Understanding. 5-22-19 to 5-24-18. New York, NY. She also had published: Response to Peter Petschauer’s paper: The Flame of Trauma. (2019) Clio’s Psyche,25, 3, 246-249.

Christopher Lynch, PhD has a new book titled Anxiety Management for Kids on the Autism Spectrum: Your Guide to Preventing Meltdowns and Unlocking Potential from publisher Future Horizons. You can find a description of the book on amazon.com. This is his second published book and a companion to his first publication: Totally Chill My Complete Guide to Staying Cool: A Stress Management Workbook for Kids with Social, Emotional, or Sensory Sensitivities (AAPC Publishing, 2012).

Peggy Rothbaum, PhD (Spring, 2019). Evaluating Our Focus: The national move towards population health must include humane animal care/control law enforcement professionals. Animal Care & Control Today, 30-31. (June 27, 2019) Protecting the Protector: Who is Taking Care of You? Justice Clearing House (National Animal Care and Control Association): Webinar.

Fall 2019 13

PS Form 3526 Statement of Ownership, Management, and Circulation (Requester Publications Only) 1. Publication Title 2. Publication Number ISSN 3. Filing Date NEW JERSEY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION/NEW JERSEY PSYCHOLOGIST 7700 2326-098X 10/18/2019 4. Issue Frequency 5. Number of Issues Published Annually 6. Annual Subscription Price QUARTERLY 4 $ 40.00 7. Complete Mailing Address of Known Office of Publication 414 EAGLE ROCK AVE STE 211 WEST ORANGE, ESSEX, NJ 07052-0075 Contact Person CHRISTINE GURRIERE Telephone (973) 243-9800 8. Complete Mailing Address of Headquarters or General Business Office of Publisher 354 Eisenhower Pkwy Ste 1150 Livingston, NJ 07039 9. Full Names and Complete Mailing Addresses of Publisher, Editor, and Managing Editor Publisher (Name and complete mailing address) Hermitage Press 1595 Fifth St Trenton, NJ 08638 Editor (Name and complete mailing address) Gianni Pirelli, PhD Managing Editor (Name and complete mailing address) Hermitage Press 1595 Fifth St Trenton, NJ 08638 10. Owner (Do not leave blank. If the publication is owned by a corporation, give the name and address of the corporation immediately followed by the names and addresses of all stockholders owning or holding 1 percent or more of the total amount of stock. If not owned by a corporation, give names and addresses of the individual owners. If owned by a partnership or other unincorporated firm, give its name and address as well as those of each individual owner. If the publication is published by a nonprofit organization, give its name and address.) Full Name Complete Mailing Address New Jersey Psychological Assoc 354 Eisenhower Pkwy Ste 1150, Livingston, NJ 07039 11. Known Bondholders, Mortgagees, and Other Security Holders Owning or Hoding 1 Percent or More of Total Amount of Bonds. Mortgages, or Other Securities. If none, check box X None Full Name Complete Mailing Address PS Form 3526-R September 2007 (Page 1) PRIVACY NOTICE: See our privacy policy on www.usps.com 13. Publication Title 14. Issue Date for Circulation Data Below NEW JERSEY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION/NEW JERSEY PSYCHOLOGIST 09/10/2019 15. Extend and Nature of Circulation Average No. Copies Each Issue During Preceding 12 Months No. Copies of Single Issue Published Nearest to Filing Date a. Total Numbers of Copies (Net press run) 1650 1650 b. Legitimate Paid and/or Requested Distribution (By Mail and Outside the Mail) (1) Outside County Paid/Requested Mail Subscriptions stated on PS Form 3541. (Include direct written request from recipient, telemarketing and Internet requests from recipient, paid subscriptions including nominal rate subscriptions, employer requests, advertiser's proof copies, and exchange copies.) (2) In-County Paid/Requested Mail Subscriptions stated on PS Form 3541. (Include direct written request from recipient, telemarketing and Internet requests from recipient, paid subscriptions including nominal rate subscriptions, employer requests, advertiser's proof copies, and exchange copies.) (3) Sales through Dealers and Carriers, Street Vendors, Counter Sales, and Other Paid or Requested Distribution Outside USPS (4) Requested Copies Distributed by Other Mail Classes Through the USPS (e.g. First-Class Mail) 1630 1630 0 0 0 0 0 0 c. Total Paid and/or Requested Circulation (Sum of 15b (1), (2), (3), (4)) 1630 1630 d. Nonrequested Distribution (By Mail and Outside the Mail) (1) Outside County Nonrequested Copies stated on PS Form 3541 (include Sample copies, Requests Over 3 years old, Requests induced by a Premium, Bulk Sales and Requests including Association Requests, Names obtained from Business Directories, Lists, and other soruces) (2) In-County Nonrequested Copies stated on PS Form 3541 (include Sample copies, Requests Over 3 years old, Requests induced by a Premium, Bulk Sales and Requests including Association Requests, Names obtained from Business Directories, Lists, and other soruces) (3) Nonrequested Copies Distributed Through the USPS by Other Classes of Mail (e.g. First-Class Mail, Nonrequestor Copies mailed in excess of 10% Limit (4) Nonrequested Copies Distributed Outside the Mail (include Pickup Stands, Trade Shows, Showrooms and Other Sources) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Total Nonrequested Distribution (Sum of 15d (1), (2), (3), (4)) f. Total Distribution (Sum of 15c and 15e) g. Copies not Distributed h. Total (Sum of 15f and 15g) i. Percent Paid and/or Requested Circulation ((15c 15f) times 100) 0 0 1630 1630 20 20 1650 1650 100.00 % 100.00 % 16. If total circulation includes electronic copies, report that circulation on lines below. a. Requested and Paid Electronic Copies(Sum of 15c and 15e) b. Total Requested and Paid Print Copies(Line 15c) + Requested/Paid Electronic Copies c. Total Requested Copy Distribution(Line 15f)+ Requested/Paid Electronic Copies d. Percent Paid and/or Requested Circulation (Both print and Electronic Copies) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.00 % 0.00 % Certify that 50% of all my distributed copies (Electronic & Print) are legitimate requests. 17. Publication of Statement of Ownership for a Requester Publication is required and will be printed in the 09/10/2019 issue of this publication. 18. Signature and Title of Editor, Publisher, Business Manager, or Owner Title Date Keira Boertzel-Smith Executive Director 10/18/2019 14:47:01 PM certify that all information furnished on this form is true and complete. understand that anyone who furnishes false or misleading information on this form or who omits material or information requested on the form may be subject to criminal sanctions (including fines and imprisonment) and/or civil sanctions (including civil penalties). PS Form 3526-R September 2007 (Page 2) PRIVACY NOTICE: See our privacy policy on www.usps.com

MEMBER NEWS

OF

Judith Glassgold, PsyD

What is scope of practice?

Scope of practice defines the professional actions and treatments that a healthcare practitioner is permitted to perform under their professional license. The scope of practice is determined by the education, experience, and competencies associated with the profession. Each state jurisdiction has its own unique scope of practice for each profession.

Psychology’s scope of practice can be found here <https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/regulations/Chapter-42-Boardof-Psychological-Examiners.pdf> and at the end of this article.

Scope of practice defines the full range of possible interventions and treatments. Not all psychologists may have expertise in these areas (i.e., forensic psychology, developmental disabilities) and psychologists should practice only in areas where they can demonstrate competence. Further, there may be some areas where psychologists, due to specialized education and training, may be competent, but these areas are outside the scope of the practice in that particular state (i.e., psychopharmacology).

Why is Scope of Practice Important?

1. Ensuring scope of practice fits current breadth and depth of psychology training

As psychology advances and new techniques have been developed, psychological education and training have evolved and grown. The scope of practice should reflect these new areas and offer opportunities to practice all the potential interventions and techniques.

2. Ensuring scope of practice is relevant to modern settings

Scope of Practice

Scope of practice needs to be updated to ensure that psychologists can use their skills in all relevant settings, such as in integrated care (healthcare settings) and organizations (business, sports teams and organizations). Terms that describe certain principles may also evolve, and our scope of practice should reflect updated professional language.

3. Monitoring interaction with other professions’ scopes of practice

As new professions seek licensure, they may seek to define their own scope of practice. Sometimes these areas may overlap with ours or be subsets of principles developed by psychologists. Legislation defining other professionals should be scrutinized carefully to assess its impact on our profession. Clarifying the boundaries of their practices, and ensuring the wording of our scope of practice reflects new terminology is essential. While other professionals may have interventions and techniques such as psychotherapy or behavioral interventions in common with psychologists does not mean that the entire scope of practice is similar.

• Practice outside scope of practice. Psychologists should take care to practice within the scope of their current license. Additionally, these issues may become cross-profession concerns. Given the overlap across professionals in some activities (i.e., counseling), scope of practice issues can become confusing. Some professionals may not be aware of psychology’s scope of practice, or their own, and may provide services outside their scope of practice. In addition, some professionals may seek out additional training in areas such as testing that are part of psychology’s scope of practice; however, that does not mean that this activity is permitted under their scope of practice and professional license. Individuals who practice outside their scope of

practice and provide psychological services without a psychology license should be reported to the Board.

4.

Advocacy and Compliance

Psychology needs to pay attention to ongoing trends in legal and regulatory issues across the healthcare professions. Psychologists should remain alert to the scope of practice of other professionals, as well as proposed licensing acts. As a professional, we must ensure that our ability to practice to the full extent of our training is not impeded by other professionals or our own licensing act.

New Directions

Recently, the American Psychological Association updated its model licensing act that includes a scope of practice. This model act clearly delineates procedures psychologists are able to perform such as supervision and applied behavioral analysis. It also more explicitly addresses healthcare settings and organizations. It also creates new terms to define specialty practices such as applied psychology and health service provider.

“Practice of psychology” is defined as the observation, description, evaluation, interpretation, and modification of human behavior by the application of psychological principles, methods, and procedures, for the purposes of (a) preventing, eliminating, evaluating, assessing, or predicting symptomatic, maladaptive, or undesired behavior; (b) evaluating, assessing, and/or facilitating the enhancement of individual, group, and/or organizational effectiveness –including personal effectiveness, adaptive behavior, interpersonal relationships, work and life adjustment, health, and individual, group, and/or organizational performance, or (c) assisting in legal decision-making.

The practice of psychology includes, but is not limited to, (a) psychological testing and the evaluation or assessment of personal characteristics, such as intelligence; personality; cognitive, physical,

New Jersey Psychologist 14

DIRECTOR

PROFESSIONAL

AFFAIRS

and/or emotional abilities; skills; interests; aptitudes; and neuropsychological functioning; (b) counseling, psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, hypnosis, biofeedback, and behavior analysis and therapy; (c) diagnosis, treatment, and management of mental and emotional disorder or disability, substance use disorders, disorders of habit or conduct, as well as of the psychological aspects of physical illness, accident, injury, or disability; (d) psychoeducational evaluation, therapy, and remediation; (e) consultation with physicians, other health care professionals, and patients regarding all available treatment options, including medication, with respect to provision of care for a specific patient or client; (f) provision of direct services to individuals and/or groups for the purpose of enhancing individual and thereby organizational effectiveness, using psychological principles, methods, and/or procedures to assess and evaluate individuals on personal characteristics for individual development and/or behavior change or for making decisions about the individual, such as selection; and (g) the supervision of any of the above. The practice of psychology shall be construed within the meaning of this definition without regard to whether payment is received for services rendered.

5. “Applied psychologist” is one who provides services to individuals, groups, and/or organizations. Within this broad category there are two major groupings – those who provide health-related services to individuals and those who provide other services to individuals and/or services to organizations. Although licensure is generic, some of the Board’s Rules and Regulations need to account for variations in relevant training, supervision, and practice.

a. “Health service provider” (HSP) Psychologists are certified as health service providers if they are duly trained and experienced in the delivery of preventive, assessment, diagnostic, therapeutic intervention and management services relative to the psychological and physical health of consumers based on: 1) having completed scientific and professional training resulting in a doctoral degree in psychology; 2) having completed an internship and supervised experience in health care

settings; and 3) having been licensed as psychologists at the independent practice level.

b. “General applied psychologist” General applied psychologists provide psychological services outside of the health and mental health field and shall include: 1) the provision of direct services to individuals and groups, using psychological principles, methods, and/or procedures to assess and evaluate individuals on personal abilities and characteristics for individual development, behavior change, and/or for making decisions (e.g., selection, individual development, promotion, reassignment) about the individual, all for the purpose of enhancing individual and/or organizational effectiveness; and 2) the provision of services to organizations that are provided for the benefit of the organization and do not involve direct services to individuals, such as job analysis, attitude/opinion surveys, selection testing (group administration of standardized tests in which responses are mechanically scored and interpreted), selection validation studies, designing performance appraisal systems, training, organization design, advising management on human behavior in organizations, organizational assessment, diagnosis and intervention of organizational problems, and related services.

Compare this to our current scope of practice:

“13:42-1.1 SCOPE OF PRACTICE

a) The scope of practice of a licensed psychologist includes, but is not limited to, the use or advertisement of the use of theories, principles, procedures, techniques or devices of psychology, whether or not for a fee or other recompense. Psychological services include, but are not limited to:

1) Psychological assessment of a person or group including, but not limited to: administration or interpretation of psychological tests and devices for the purpose of educational placement, job placement, job suitability, personality evaluation, intelligence, psychodiagnosis, treatment planning and disposition; career and vocational planning and development; personal development; management development; institutional

placements; and assessments in connection with legal proceedings and the actions of governmental agencies including, but not limited to, cases involving education, divorce, child custody, disability issues and criminal matters;

2) Psychological intervention or consultation in the form of verbal, behavioral or written interaction to promote optimal development or growth or to ameliorate personality disturbances or maladjustments of an individual or group. Psychological intervention includes, but is not limited to, individual, couples, group and family psychotherapy, and psychological consultation includes consultation to or for private individuals, groups and organizations and to or for governmental agencies, police and any level of the judicial system;

3) Use of psychological principles, which are operating assumptions derived from the theories of psychology that include, but are not limited to: personality, motivation, learning and behavior systems, psychophysiological psychology including biofeedback, neuropsychology, cognitive psychology and psychological measurement; and

4) Use of psychological procedures, which are applications employing the principles of psychology and associated techniques, instruments and devices. These procedures include, but are not limited to, psychological interviews, counseling, psychotherapy, hypnotherapy, biofeedback, and psychological assessments.”

Question

What changes would you make to our current licensing act? What are your thoughts to APA’s model licensing act? Please send your feedback to our Director of Professional Affairs, Judith Glassgold, PsyD, njpadpa@psychologynj.org.

Conclusion

As the field of psychology advances, New Jersey psychologists have to ensure that our scope of practice stays abreast of new developments and trends in psychology, the marketplace, and other professions. This will ensure that our state licenses allow us to provide all the interventions and services that we are trained to provide. This will ensure that there is adequate access to services for patients well as employment opportunities for psychologists. ❖

Fall 2019 15

Announcing the Eight 2019-2020 NJPA Foundation Community Service Project Grants

by the NJPA Foundation Board of Trustees

President, Matt Hagovsky, PhD; Secretary, Toby Kaufman, PhD; Treasurer, Abby Rosen; Board Trustee, Regina Budesa, PsyD; Board Trustee, Richard Klein, EdD; Board Trustee, Ann Stainton, PhD; Board Trustee, Alyssa Austern, PsyD; Board Trustee, Belvin Williams, PhD; Board Trustee, Eileen Kohutis, PhD; NJPA President-Elect, Lucy Sant’Anna Takagi, PsyD; Executive Director, Keira Boertzel-Smith, JD

Each year, The NJPA Foundation identifies exemplary programs that provide psychological services to those who cannot afford it and trains doctoral students to work with these underserved populations. We invite applications from programs across the state of New Jersey, with the goal of identifying and supporting model programs from each county. Visit <www. psychologynj.org/njpa-foundation> to read more and make a donation to help us continue this important philanthropic work! We strongly encourage use of the 2020 dues bill for donations to the NJPA Foundation.