FRAGMENTSFRAGMENTS

FRAGMENTS FRAGMENTS FRAGMENTS FRAGMENTS FRAGMENTS

FRAGMENTSFRAGMENTS

FRAGMENTSFRAGMENTSFRAGMENTS

FRAGMENTSFRAGMENTS

Letter from the Editor

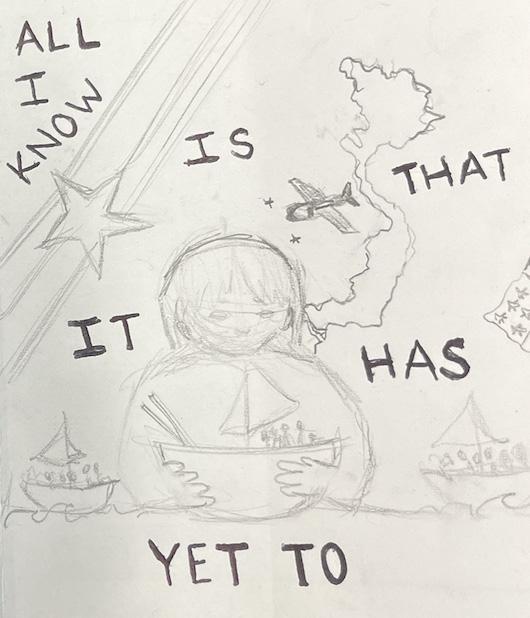

Fragments was born out of my wish to see the artistic work of my friends and family. As a result, I have compiled visual art, a screenplay, and an article from my loved ones. These Asian artists cover deeply personal topics that are nearly universal experiences for our commuity -- like how colorism affects body image or how mental health can be impacted by decades-old wars. But sometimes our art can be a lighthearted script, and I wanted to show it all through Fragments.

-Julianne Le

“untitled”

by allie estepa

Ever since I was a small girl, I was always acutely aware of my own skin — its color, its texture, its thickness, its smoothness. Conversations between my aunts and the neighborhood women always obsessively revolved around skin, as if its condition and the appearance was a marker of a person’s entire being. My mother has repeatedly recounted to me the impact her skin had on her childhood. She was taunted and called names, for her skin was the color of wet sand and this was largely looked down upon in the provincial town she had grown up in. Although her

skin lightened as she aged – now closer to the color of a white sand shore, entirely untouched by the waves – she associates stories of her childhood to each of the scars on her legs. Resembling the mysterious craters of the moon, the scars traced the routes she would walk and the branches of the mango trees that she climbed. She recounted spending the simple days rolling around in the dirt and grass with her brothers and sister. Despite the cruelty from the playground kids and the judgmental insults from critical aunties, the freedom of childhood remained rosy in her memory.

In adulthood, my mother was always extremely self-conscious about her scars. She never wore shorts or skirts out, never exposed the texture of the skin on her legs to the judgmental eyes of others. As a result, my own childhood looked rather different from hers. From infancy to age six, I grew up in the same neighborhood where the mango trees she climbed and the dusty streets she roamed still stood. My memories from that age, however, took place inside – in the cool of my air-conditioned bedroom, playing video games, reading storybooks and

“Green Mango Fruits Hanging on Tree” by Drift Shutterbug is licensed

watching the same movies over and over. She never allowed me to ride a bike or do anything that might cause some sort of injury to me – more specifically, my skin. It never occurred to me back then to fight against it, especially when I knew the importance of keeping my precious skin intact. Perhaps a part of me knew that she was just protecting me from the cruelty she knew all too well. As time went on and we migrated to the States, however, my mother found it impossible to continue shielding me from the sun and the dirt and the outdoors. She was rightfully busy building a life in a new country. I began to spend more time outside on the playground, under the often unforgiving sunshine of the San Fernando Valley and as a result, my skin darkened. I found it

confusing how my ability to quickly tan was now being praised, the glow of my brown, unblemished skin garnering compliments constantly. No matter where I was, no matter how much the cultural standard for beauty differed, I knew that skin was universally important – that it would always be the aspect which determined my worth. Despite my lack of scars, however, I quickly grew up, and my skin displayed the passing years. As bumps and textures riddled my face and my upper arms, I became increasingly self-conscious. I did not feel contempt for my deep complexion, nor did I have scars to hide, but I knew for a fact that I had inherited my mother’s desire to escape her own skin. I wondered if I would ever be free from the cage that was my own body,

encased by this shell that I was never able to sand smooth. If I did away with my skin — if I peeled it away like the membrane around a bright yellow mango, would the sweetness of my flesh and the power at my core finally be revealed? Would doing away with the burden of smoothness and perfection finally set me free? I blamed my mother. I blamed my aunts. I blamed the neighborhood women. And I should not have. Because we were all just fruits from the same tree, unaware that beneath the bark, the trunk was rotting from the inside. Could a fruit tainted by its decaying tree be saved? Could its pit one day produce another tree liberated from its sickly past? I will let you know when my first fruit grows.

I did not feel contempt for my deep complexion, nor did I have scars to hide, but I knew for a fact that I had inherited my mother’s desire to escape her own skin.