OUR MISSION.

Through our zine, we aim to uplift and highlight Asian American athletes by covering all aspects of the athletic experience: from growing up as a youth athlete, to attending professional games as a dedicated fan.

Our zine is a culmination and analysis of Asian Americans in the world of athletics, working to combat the overwhelming lack of representation in mainstream media. We serve as a space for Asian American athletes to share their stories, both as a celebration of the success of our athletes, and as a validation of the experiences faced as a result.

We welcome all forms of content and hope to capture the diverse experience of Asian American athletes.

IT SWIMS IN THE FAMILY.

By Chloe Nimpoeno

MATCH POINT: FINDING MYSELF ON THE COURT.

By Gary Chang

By Maya Salvitti

EDITOR’S NOTE.

By Elle Hatamiya, Chloe Nimpoeno, & Isaac Cheng

LIGHTS OUT.

BY EMILY HSI

Emily Hsi is a first year English major and Professional Writing minor hoping to also minor in Creative Writing. She loves poetry, matcha, and yelling at her computer screen when her favorite teams aren't winning

When I was little, I never paid much attention to sports. Perhaps I was falling into the Asian stereotypes, but I was much more concerned with schoolwork and band performances instead of sports, even though I went through a cycle of gymnastics, cheerleading, and ballet when I was younger.

After a certain point, I accepted that there was no place for me in sports, even insisting on bringing my tablet to my brother’s little league games so I could write instead of having to yawn through what I considered a waste of my night. I even ended up attending a high school where football was the most prominent after school activity, and since I was in marching band, I was forced to perform at every game not that I ever paid attention to what was going on. I’ve skied since I was in preschool, but I hardly considered that a competitive sport, hardly following along with the winter Olympics whenever they broadcasted freestyle skiing.

Funnily enough, I made an online friend who lives in Singapore, and she convinced me to watch one video for Formula One, a sport made up of twenty drivers, ten teams, and high-tech cars. It was the last thing I expected to become invested in. I spent most of my time lying in my bed while writing on my computer or baking sweet treats for my family, and a Euro-centric, seemingly male-dominated sport seemed like an obviously chaotic match-up.

But I loved it. After my first race I stayed up until four in the morning just to watch it live I was completely hooked. Since then, I’ve watched every race as it happens, am a proud owner of two Lego F1 cars, and annoy my friends on a regular basis by talking about my favorite drivers. I’ve even been tuning into MotoGP races as I grow more curious about motorsports in general. Despite my own beliefs that I would never be a “sports person, ” I fell, and I fell hard

In an ironic twist of fate, I’m going to be attending the Formula One race in Singapore. I initially applied to study abroad in the fall as a way to broaden my horizons and become more in touch with my Asian heritage, but now it’s also an opportunity to bridge two of my interests: being Asian American, and Formula One racing.

THE POWER OF REPRESENTATION.

BY

FORD HATAMIYA

I was a Japanese American kid coming of age in the 80s in Marysville, California, a sansei in a rural farm town. Back then, Marysville’s population was 4% Asian, mainly descendants of turnof-the-century Chinese and Japanese immigrants. The Hatamiyas were an archetypal JA family that farmed, were unjustly incarcerated, and farmed again.

In small towns in the good ol' US of A, the focus is on boys football, basketball, with girls as cheerleaders or second class athletes. The traditional misogyny on display and unchallenged. The claustrophobia and suffocation as seen in Friday Night Lights was present in Marysville.

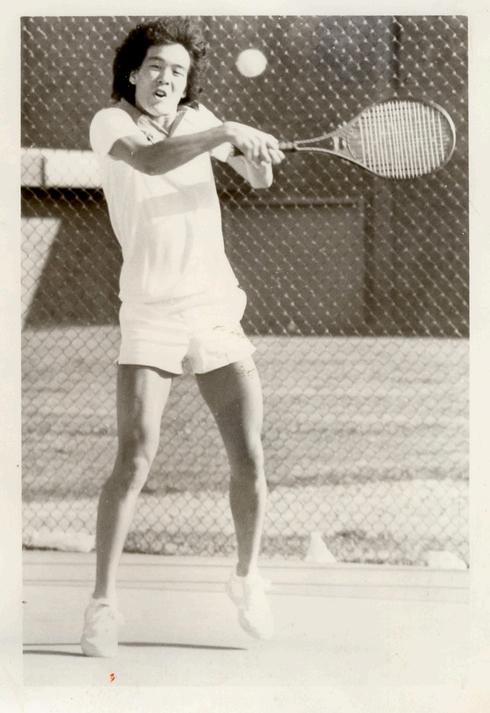

Tennis was my sport Like being Asian American in opposition to whiteness, maybe tennis was a protest against football. Elegance against brutality. Tennis seemed beyond Marysville. It was played in other places by other people, in big cities and by Europeans.

From the ages of 10 to 18 the years 1975-1983 my focus was tennis. My parents had the means to belong to the local racket club. In summertime, the adult members reserved courts for the cooler times of day They relegated youth lessons and matches to peak scorch, when the heat waves visibly rose off the painted asphalt. I thrived in the punishing Marysville summers, driving farm machinery or striking tennis balls.

In retrospect, it was pivotal for me as a young athlete to choose a hero. It set a developmental path. I wanted to be Bjorn Borg. I copied his game: a twohanded backhand, infinite groundstrokes, few unforced errors, and rarely charging the net. I wanted Fila fits, Diadora shoes, and a Donnay racket. My hair couldn't mimic Borg's headbanded Jesus-like locks.

Borg’s persona guided me. He was so cool, stoic, unexpressive His subtle joy only appeared after winning a championship point. His rivals were Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe. They were both fist-pumping, egotistical, loud American players. Always arguing with line judges and sometimes yelling at fans and journalists. They were embarrassing assholes. They weren’t me.

In contrast to Marysville yokels, football, and McEnroe, I chose tennis and Borg. Was this the model minority option?

As someone from a group that is marginal and minor, the paucity of representation requires choosing a hero that is center and major. It wasn’t necessarily hard to do I had already identified with characters in the Waltons, Oakland A’s players, and the Bee Gees. Because we weren’t in the frame, I've had a lifetime in relating to the humanity of others who aren’t Asian. It’s a muscle I still flex. I’m proud of my minority-born empathy.

And yet, real representation is powerful.

Michael Chang won the 1989 French Open. He sounded like me when he spoke. His parents in the stands could have been mine. He had the physical build of many of my Asian American college buddies. In fact, his brother Carl Chang and I were students at UC Berkeley together. This familiarity made me believe that WE won the French Open and that WE would win the US Open, the Australian Open, and Wimbledon. Every championship felt accessible. Representation breeds a confidence in heightened access, and confidence contributes to access.

I needed Naomi Osaka in 1983 Her recent championship wins and her bold advocacy for mental health have inspired. The connection she creates is beyond celebrity to fan, more than champion to aspiring athlete. She is fam. We see her and he sees us. We love her and she loves us back. She can win and struggle as a dimensional human. She allows us to see what we can become.

That’s the power of representation. It is access actualized This is my testimony to a long-standing notion.

Ford is a management consultant that lives in Albany, CA. He minored in African American Studies as an undergrad and has an MA in Ethnic Studies, both at UC Berkeley.

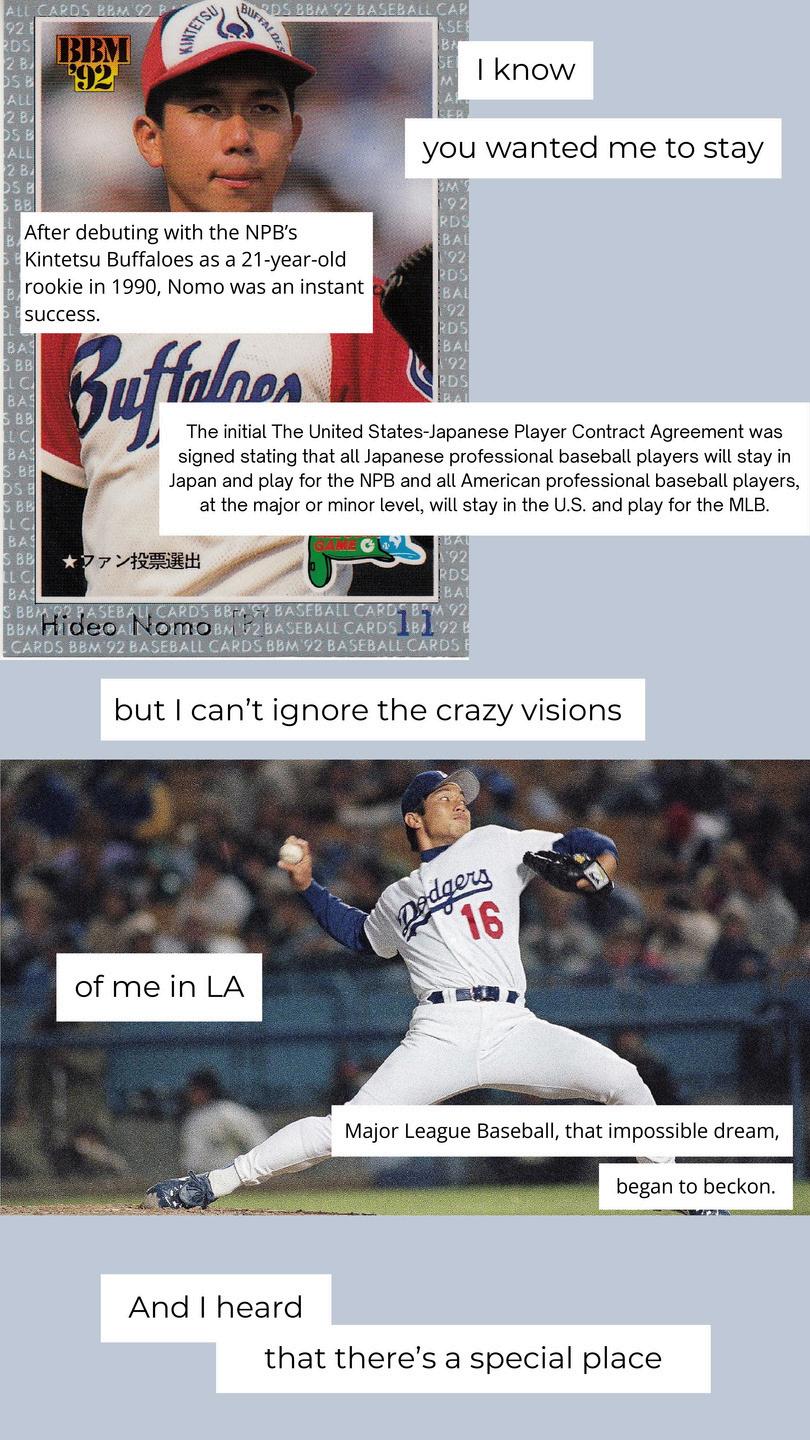

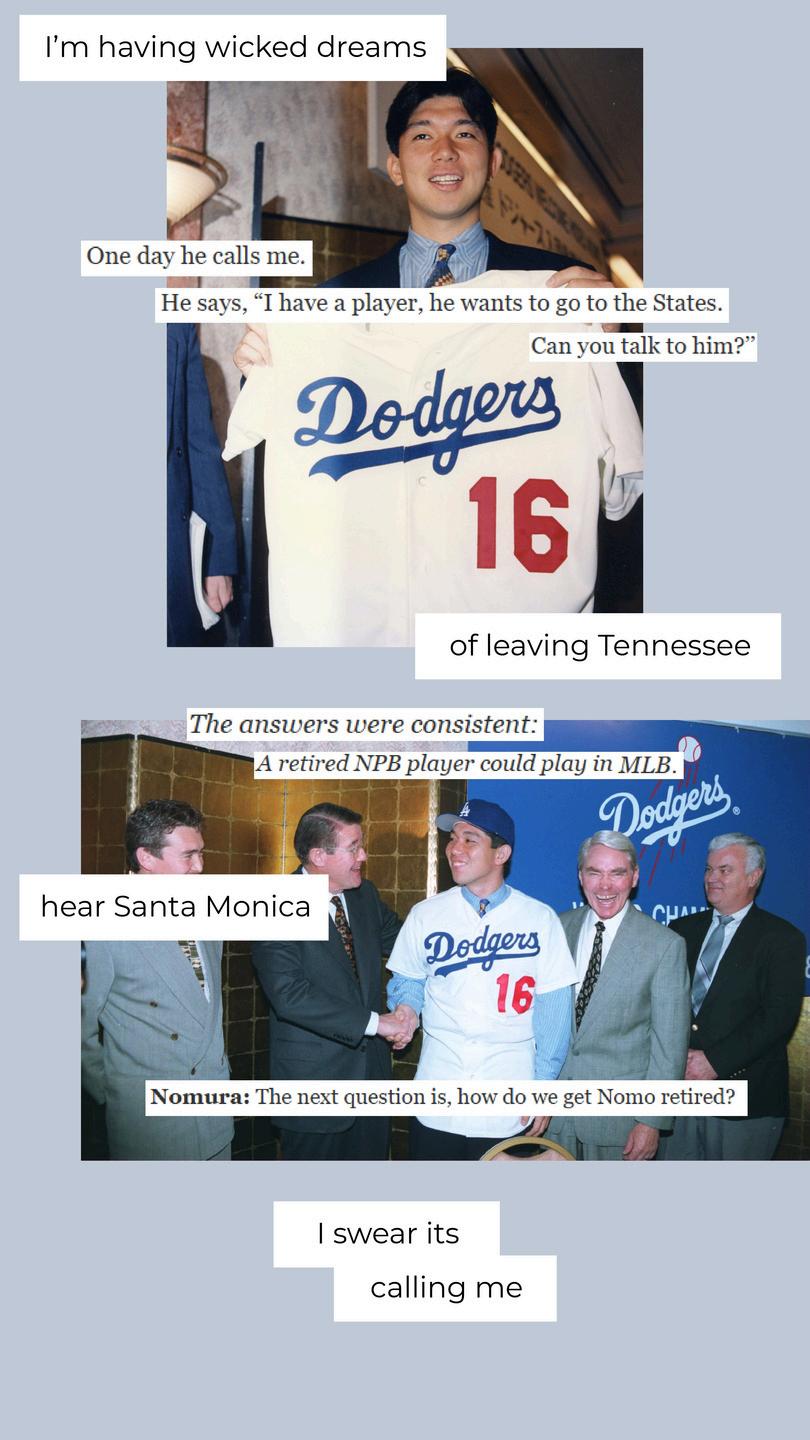

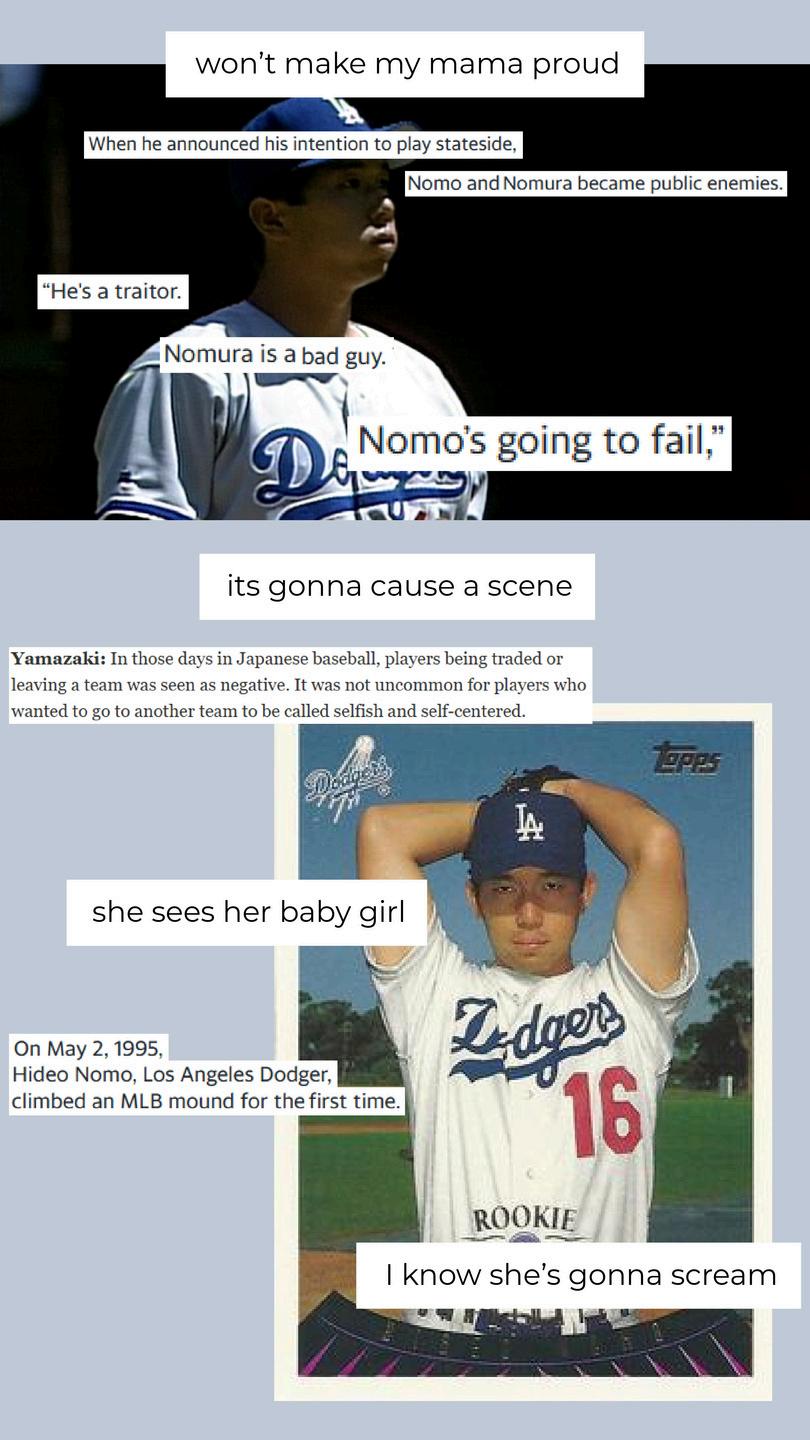

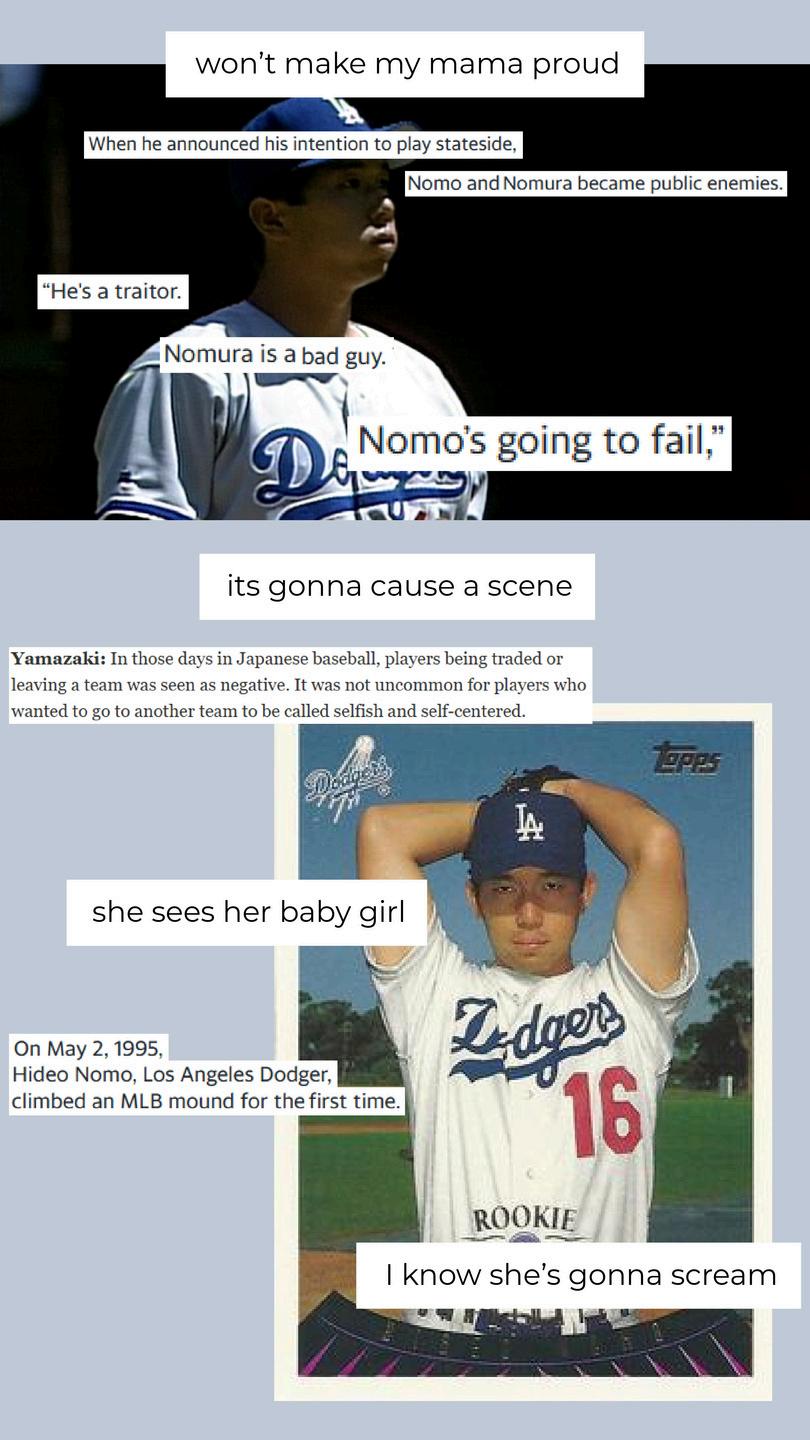

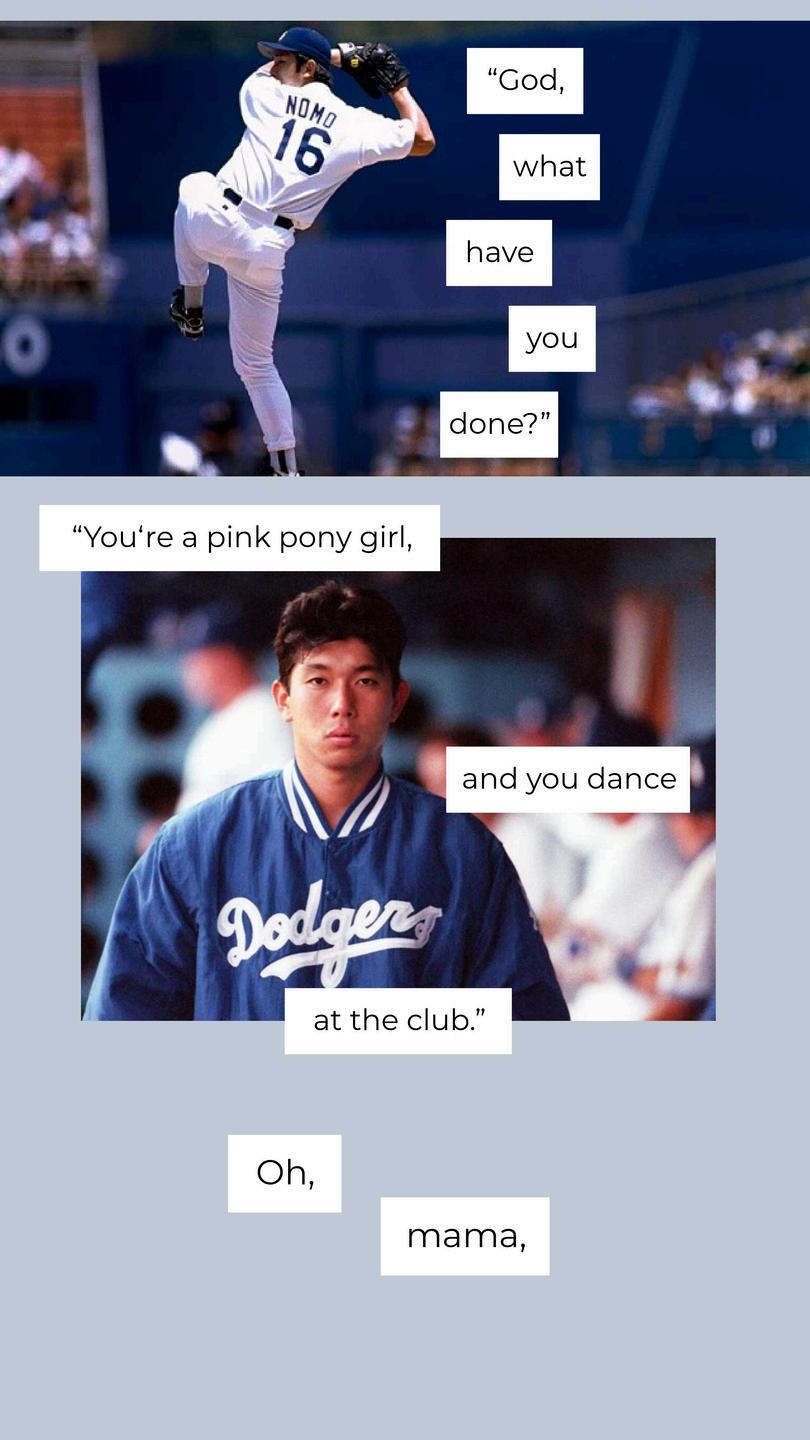

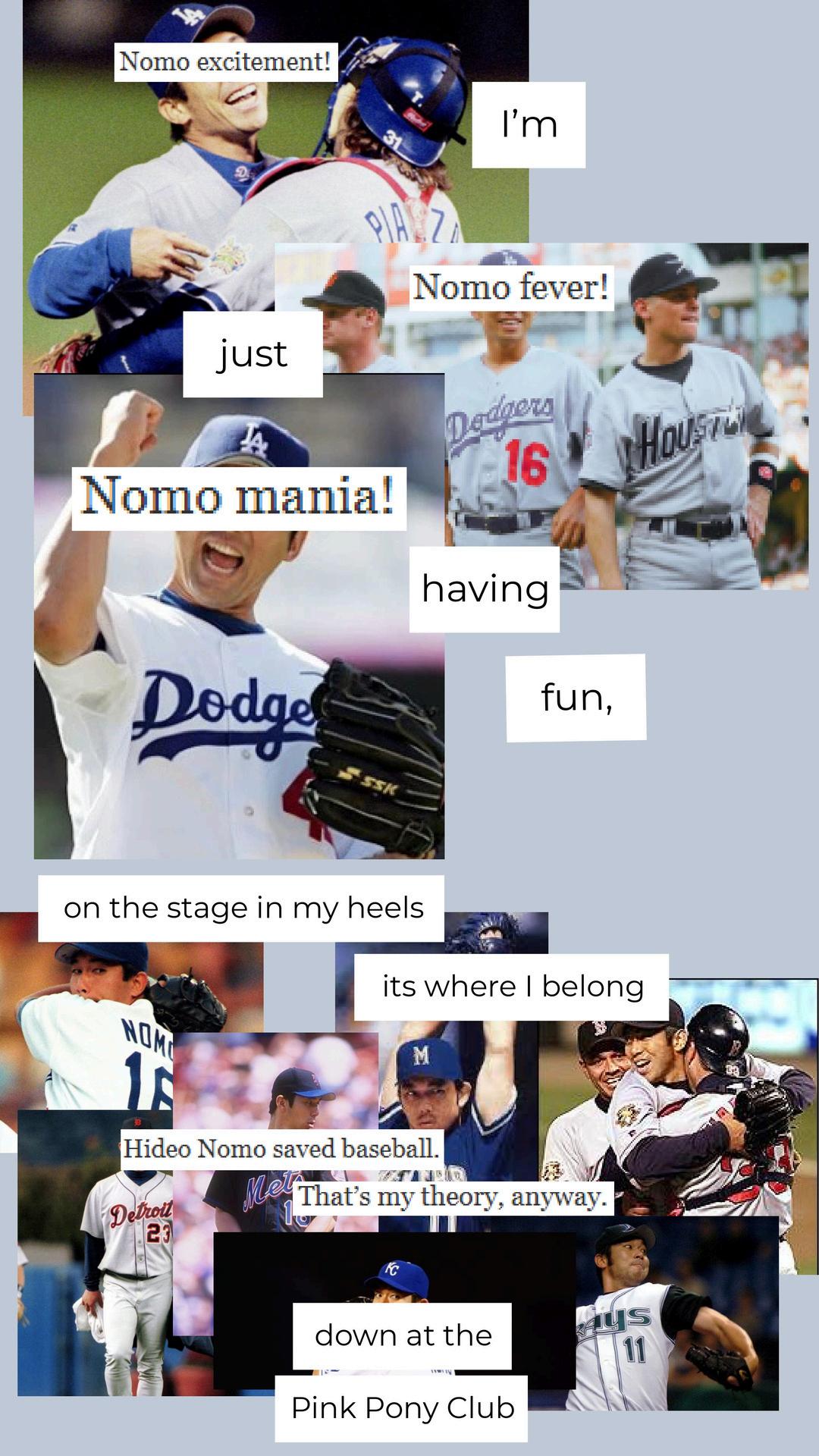

HIDEO NOMO: PINK PONY CLUB.

This piece uses both imagery, lyrics from the song “Pink Pony Club” by Chappell Roan, as well as snippets from articles by the New York Times, LA Times, and Yahoo Sports in order to explore how Hideo Nomo broke the barriers that existed between American professional baseball and Japanese professional baseball that lead to the rise of various stars such as Ichiro Suzuki and Shohei Ohtani in the MLB today.

Zoe Nimpoeno is a former Asian American athlete She is currently a freshman in college, but has been on a swim team from middle school until high school. While Zoe has been a swimmer since grade school, she didn’t become interested in watching sports as a whole until the pandemic in eighth grade. Since then, she’s grown to love watching a variety of sports and has always been interested in the stories that follow each individual player.

MIRACLES AND MEDALS.

BY CHEZ PONDEVIDA

MANY FILIPINOS ARE DEVOUT CATHOLICS, WITH THEIR FAITH SERVING AS A SOURCE OF STRENGTH. NOWHERE IS THIS MORE APPARENT – AND LITERAL –THAN IN THE REALM OF SPORTS.

In the summer of 2020, Hidilyn Diaz heaved 127 kg over her head in a clean and jerk move that would secure her a gold medal the first ever for the Philippines in their nearly 100 year history of participating in the Olympics. As my family and I witnessed this feat on TV, my mom whispered to me, “There’s a moment before she lifts the weights, where you can see God giving her a hand.” Later during the awards ceremony, an emotional Diaz cried, “Thank you Lord!” while holding up her new hardware My goodness, I had thought. What a Filipino way to celebrate.

Catholicism is the predominant religion in the Philippines, and like many Filipino-Americans, I was raised Catholic. While I don’t consider myself very religious nowadays, I was still moved by Diaz’s display of faith.

She had just ended the Philippines' gold medal drought, and the first thing she did was thank God! She humbly attributed her victory not to her own effort and skill, but to the divine. I thought of my mom ’ s words. You can see God giving her a hand. To Diaz and Filipinos all across the globe, her Herculean performance wasn’t just an incredible display of athletic power. It was something much holier than that. It was a confirmation of their faith of God’s love. When Diaz lifted up the weights, she was touched by the divine. For a brief moment, she became Atlas holding up the heavens. She transcended her human limits and went somewhere beyond. She became a miracle. And is that not what having faith is all about? To believe in a world in which miracles can occur?

Chez Pondevida is a 23 year old Filipino-American living in Los Angeles. She is a lover of all things sports, and would die for Stephen Curry.

PHOTO CREDIT:

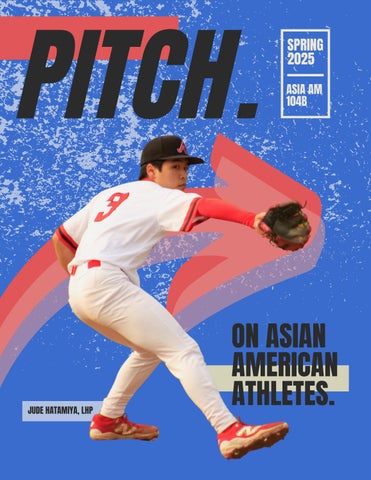

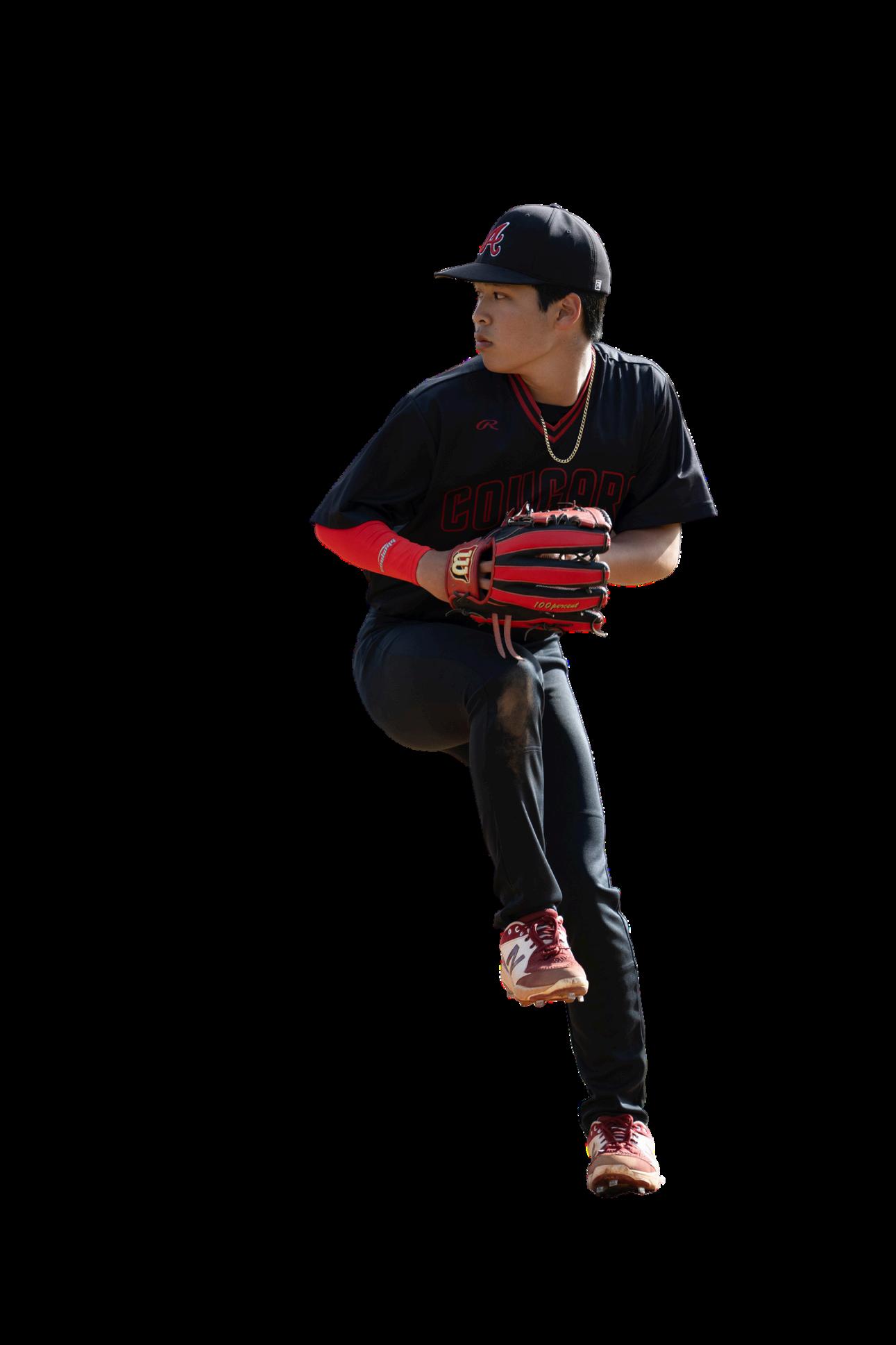

ON THE MOUND.

BY JUDE HATAMIYA

Growing up as an Asian American baseball player, I often searched for athletes who looked like me on the field. I found my biggest inspiration when I discovered Shohei Ohtani. He was the first player who truly inspired me. Not just due to his talent, but due to the fact that he shattered all the stereotypes about what Asian players can do in baseball Ohtani, throwing off the mound at 100 mph and then stepping to the plate and hitting home runs was almost impossible to believe, and never done before in the sport. He was an all star caliber player at not just one position, but two. He proved that players of Asian descent are able to take over the sport completely.

Seeing Ohtani succeed at the highest level made me believe that I could too. His power, work ethic, and passion for the game reminded me that if I stay dedicated to the sport, I can accomplish anything. But while Ohtani was my first big inspiration, it was Yoshinobu Yamamoto who I relate to the most. Standing at 5'10" and weighing 176 pounds, Yamamoto is nowhere near the biggest or tallest player on the field, especially for a pitcher. Yet when he takes the mound, he's electric. His pinpoint location, nasty pitch mix, and confidence on the mound show that dominance is not about size.

Standing at 5'9" and weighing only 155 myself, seeing Yamamoto excel in Major League Baseball shows that size isn't all that matters. Yamamoto's masterful skill helps me to believe in myself and surpass any physical expectation that others may have because of my height.

Not only have these players provided us with good role models, but they have also established the benchmark for Asian players and what’s possible in baseball. Their accomplishments make it a privilege to be an Asian American baseball player and encourage me every day to work even harder. My goal is to emulate them and hopefully inspire people as they have influenced me.

Jude Hatamiya, High School/College Baseball Player

A NON-ELITE ATHLETE’S ASIAN AMERICAN SPORTS EXPERIENCE.

BY GARY CHANG

Just your 3rd generation Onewheel riding Chinese grandpa loving on his four hellahapa grandkids

Unlike my elite athlete kids and grandkids, this 1960’s undersized 5’5”, 120 lb. Chinese high school nerd found solace and sanctuary as a role player, immersing myself in Nisei league basketball.

My Asian American, non-elite athlete’s experience was all encompassing and got me through my otherwise boring and mundane early and late teen years.

Let’s put this all in perspective.

As a 13 year old junior high school student, I made a decision that was to change my life forever. I was invited to play basketball for Berkeley Methodist United church team (they needed players to round out the roster) as one of 3 permitted Chinese players and I eagerly agreed.

At Garfield Junior High School and at Berkeley High School, I took part in zero activities went to school and came home threw my books down (no backpacks then) and over to the outdoor courts up the block and across the street. I played with friends fooling ourselves that we were getting better; no guidance, no

tutoring, reinforcing all the wrong techniques, the wrong shooting form it was so fun!

I loved basketball and still do

Yes, I was the model minority guy, invisible to white students, black students and administrators; I was a student worker drone. Better than getting jumped in the bathrooms like the white kids…

Friday was Basketball Practice Night!

I tolerated the drudgery of the school week for weekends. Dads would give us rides to the gym and we were coached by…dads. They might not have known much about basketball but they loved their sons and they tried their best for us, even after a long day at work. We developed friendships, learned sportsmanship, how to win, how to lose, to respect the game and how to play the “right” way.

Mike Yatabe, a Sansei who played basketball in the 1970s and younger contemporary of mine recalls:

“The Japanese league was so popular and so

huge when I was playing in the 1970s that we (Mike and his friends) made the decision… do we want to make the high school team and sit the bench or do we want to play and be one of the better players on the team. And so most of us played church ball … We used to fill gyms with fans and there would be wall-to-wall people at our tournaments ”

Steven D. Chin, in his article for the Nichi Bee Weekly, says:

“The attendance at games were at an all-time high as basketball was a premier social event for the Japanese American community, often drawing standing room only crowds in the hundreds at Garfield Gym in Berkeley (now Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School).”

Saturdays and Sundays were “ game days” and it was the opportunity to put on our church basketball uniforms and compete against our primarily. Japanese American peers. Sangha, Ohtani, Diablo, Free Methodist, BMU, Troop 26… We kept track of opposing players and teams and the league standings. I always looked forward to seeing the better “AA” teams play each other

The Garfield Junior High gym would be packed with parents, players and girls, yes girls, to see the best and most popular teams and the cutest guys.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Nisei League basketball games were the place to be

Nisei League invitational basketball tournaments - pre-season, holiday and postseason held in Sacramento, San Francisco, Fresno and Los Angeles were a highlight for young basketball players like myself. The requisite tournament dances were not to be missed for the live contemporary soul music. I reluctantly admit, my time was spent with the fellas…gotta focus on the next morning’s 9:00 AM “Friendship Game” you know…

Fast forward and I had the privilege of playing basketball for AOAC (Alameda Oakland Athletic Club) and later on with the Inner Circle Gamblers. These teammates are my lifetime friends, some going back 60 years. We go on Zoom weekly, we sometimes vacation together and we are always there for each other in a time of need.

Though we were not always an elite team, we have a bond with each other that transcends victories, losses and Father Time.

Our sworn opponents are now heartfelt friends because we share the love of basketball and competition. We laugh together and pick each other up as our former glory years skills diminish to clumsy pratfalls on the hardwood court we love.

How many of you share my thankfulness and gratitude for all those who provided us with our Asian American sports experience?

https://www.nichibei.org/2019/05/a-brief-history-of-japanese-american-basketball-in-the-bay-area/ https://www.flickr.com/people/187313507@N04/ JA Tournamentprograms | Flickr SOURCES:

SLOPES AND STEREOTYPES: NAVIGATING SKI CULTURE AS AN ASIAN AMERICAN.

It is no secret that skiing is a sport dominated by the wealthy and white, and outside of your springbreakers, president’s weekend warriors, and rich Chinese tourists, I was among the few asian faces seen on the mountain. For the three years I participated, I was the only person of Asian descent on the Squaw Valley (now Palisades Tahoe) Youth Big Mountain Competition Team. Across all those seasons, I never saw another Asian face not among my teammates, coaches, or even at competitions. Coming from the Bay Area, where I had grown up surrounded by a large Asian American community, it felt especially jarring.

At first, I didn’t think much of it I was just excited to ski, to throw myself down steep terrain, and to be part of a team that shared my love for the mountains. But over time, the differences became apparent to me. My teammates were almost all white and local to the Tahoe area. Many had grown up skiing these slopes together, and the tight-knit dynamic was hard to break into. I often felt like an outsider not because anyone was overtly unkind, but because I didn’t share their cultural shorthand, their inside jokes, or their unspoken sense of belonging. Group chats, carpool invites, and off-the-hill hangouts seemed to circulate without me. It wasn’t just about social exclusion; it was about feeling invisible in a space where no one else looked like me or came from a similar background. I realized that simply looking different was enough to set me apart, and there wasn’t anything I could do about it.

There were moments that felt more openly uncomfortable. One tradition among some teammates was something they called a "Chinese Downhill," where they would straight-line recklessly through the most crowded green trails on the mountain, laughing and joking in a way that clearly mocked the inexperienced, often Asian, tourists who could frequently be seen wildly out of control on beginner terrain. Watching them make light of people who looked like me, even if indirectly, made me feel even more isolated—like my identity was something to be laughed at.

Despite the isolation, I stayed. I kept showing up early, dropping into lines that scared me, and pushing myself to grow as an athlete. The mountain became both a sanctuary and a proving ground, and my persistence paid off when I won third place at a local freeride competition. That podium finish felt like a validation not just of my skiing, but of my place in a community where I often felt invisible. It reminded me that even when I didn't fully belong socially, I earned my spot through grit, resilience, and love for the sport. Being the only Asian athlete across those three years forced me to grow in ways I hadn’t expected. It taught me how to find pride in my identity even when it set me apart, and how to stay true to myself in environments where I might always stand out.

BY AIDAN SETO

Aidan is a rising senior at Emory university and has been skiing since he was 3 years old. He was a member of the squaw valley big mountain competition team from 2017 to 2019 While he is no longer skiing competitively, skiing is still a big part of his life and he tries to go as often as possible, despite going to school in the southeast.

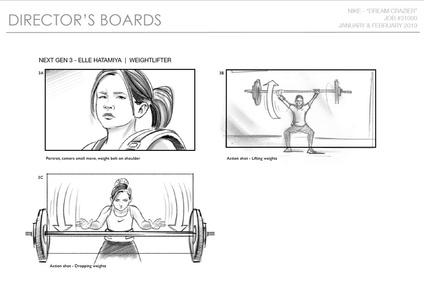

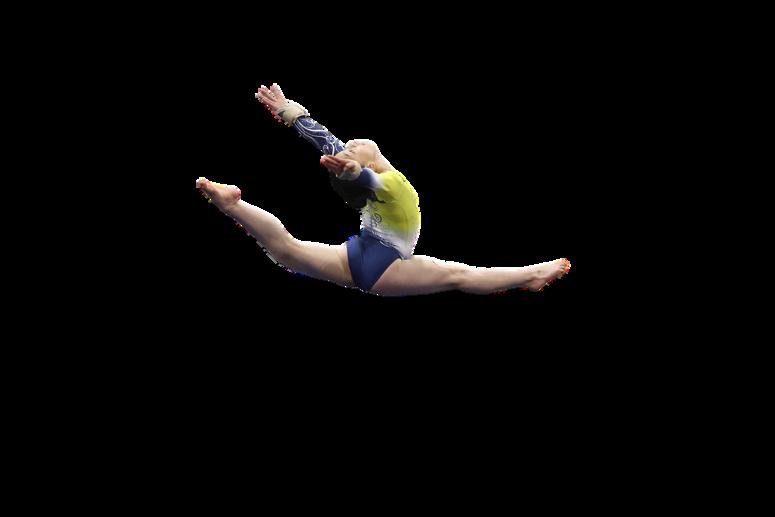

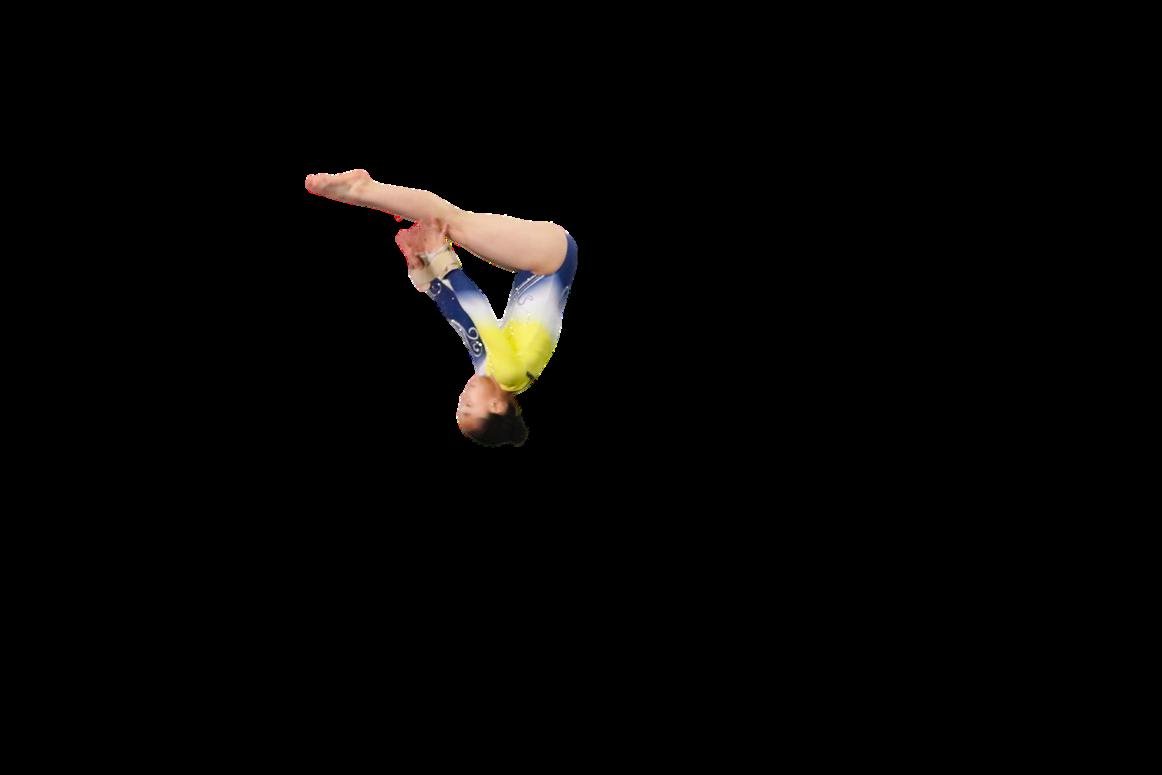

#ELLEISFORLIMITLESS. MY

JOURNEY IN RETROSPECT

Growing up, I was always shy. I didn’t raise my hand, I didn’t initiate new friendships, and I didn’t express my feelings in public. But, while silent, I could still shine on the stage

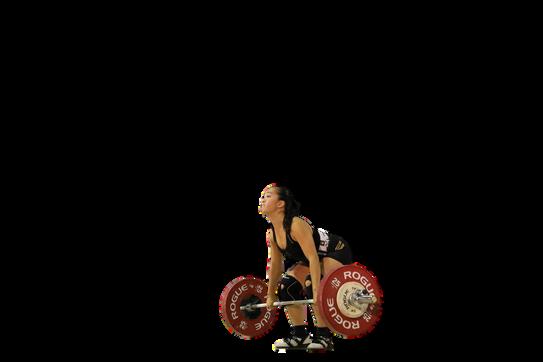

In 2013, I joined the Golden Bear Gymnastics JO (Junior Olympic) Team at UC Berkeley, where I spent the majority of my time for the next six years. In 2014, I began CrossFit at my mom ’ s gym. While it was supposed to help with my gymnastics training, I didn’t like it very much I hated cardio (I still do) What did I enjoy? The Snatch and the Clean & Jerk. The combination of my strength, flexibility, and body awareness made them easy to learn. But I trained alone, or occasionally with my 8 year old brother. Lifting in Oakland felt very lackluster compared to the exciting, harsh, and intense atmosphere within the hills of Berkeley.

Gymnastics was where my heart was 5 times a week, 4 hours a day, I marched into the gym, doing my best no matter how I felt. My best friends were in the gym, perhaps bonded through the trauma of doing hollow holds for minutes on end, or simply as a method of coping with our extensive time spent together. I loved training; I loved competing; I was infinitely obsessed with the sport.

In 2016, a few months before my win at the USA Weightlifting Youth National Championship, followed by the best gymnastics season of my life, everything changed.

Suddenly, the 30 Instagram likes I got from my mom ’ s friends turned into thousands of views and hundreds of comments, many of which mysteriously happened to this attention, promoting h known as #elleisforlimitles

My feature in the Nike “Dream Crazier” commercial!

2016 Youth Nationals: Snatch

My social media presence quickly grew. Still today, I’m not aware of everything that was going on. My mom managed everything; at the time, I didn’t even have a phone. I honestly didn’t care about any of it. All I wanted was to practice gymnastics with my friends; the two hours a week I spent weightlifting felt meaningless.

I became the face of C-Tier news: the type of articles that pop up when you ’ re searching for something else. I was portrayed in a variety of ways (none of which were accurate). My mom would respond to interviews for me, presenting me as a well-spoken 10 year old with a welldefined weightlifting dream (not true).

New York Post, USA Today, and Business Insider took a different approach: formulating their own videos as compilations of my content, with captions based off of assumptions and outdated information.

I was also featured in several international articles, ranging from Poland to Argentina, and Hungary to Indonesia (I cannot verify the accuracy of their contents due to language barriers). And of course, a few features on underground websites built for predators and pedophiles. But I was unaware of nearly all of this while it was occuring.

The perpetual misrepresentation continued. I was flown out to be on the Harry Connick Jr. show. I didn’t know who he was and he didn’t know who I was. He asked me if I knew any jokes.

But finally, I hit the athletic big leagues: my family and I got to tour the Lululemon headquarters, Bleacher Report sent a team to produce a video on me, and Nike reached out.

In February 2019, my mom and I flew to LA for a day (I didn’t want to miss my math test the day before). The experience was surreal, and I

2017 Youth Nationals

couldn’t even take it all in. I thought that I was normal, and I found it funny that they picked me I didn’t see my accomplishments as impressive or noteworthy. Nonetheless, the producers drenched me in fake sweat, and I lifted an embarrassingly light weight as 8 actors pretended to work out behind me It aired during the Oscars.

Online, and now at school, I was “that little Asian girl who weight-lifts.” Not entirely inaccurate. At ten, I was 66lbs and 4’5”. But inside, I was still just a gymnast.

Back at gymnastics, I quickly became overwhelmed with injuries: chronic knee issues, unexplainably debilitating back pain, sprained ankles, and broken toes, to name a few. My knee pain and back problems still persist today, despite surgery, thousands of dollars spent on treatment, and a few too many sketchy “healers.”

In retrospect, the injuries are what kept me in the sport for so long. The constant setbacks kept me from burning out and distracted me from the chaos at the gym

In 2020, my gymnastics team moved to a new location and I got knee surgery. For a year, I loved being there. I was a college recruit in training, and my coaches at my gym loved me (a little too much). Shortly, everything went downhill.

I was the favorite of the gym. I could do no wrong in my coaches eyes, and I was constantly compared to my teammates. They had a completely different experience Eventually, enough was enough. Despite the gym being our home, we could no longer handle the overt sexism, homophobia, racism, and bullying from our coaches. Not to mention the body shaming, anti-science, and sexual assault; this was only the tip of the iceberg. But that’s a story for another day.

We switched teams, to a gym 5 minutes from our old gym, but a 40 minute drive from my house. Now, the grooming I faced became emotional abuse, which, to be frank, was much less enjoyable I didn’t last long After 6 months, I finally quit. It should have only taken 6 days.

When I quit gymnastics, I felt so free only for a couple of weeks. I hated the feeling of aimlessness. I needed to be back on my goaldirected mindset. So I turned to weightlifting. But this time, everything would be on my terms.

I joined a team: Max’s Gym. Filled with about a dozen 30-something year-olds, the gym was an isolating place. I had just escaped an environment where adults had betrayed their promise to help me become a better athlete Even though I pretended not to be, I was still broken.

While I didn’t make any friends at first, I loved lifting there. It was a safe space, where I could work hard and push myself, but this time, safely. My once 30,000 Instagram followers dwindled, and I finally began to post for myself.

A year and a half later, I began lifting at UCLA. The day I moved in, I made lifting friends. Finally, for the first time ever, I had people my own age I could lift with. I was overjoyed.

USA Weightlifting National University Championship

The work wasn’t over. Last spring, we decided to start an official UCLA Club Sport team It was difficult. I was supposed to be president. None of us knew how the process worked. We struggled through building a coaching structure, managing a surge of 20 athletes who had never lifted before, fundraising $5,000, and running a club with no foundation. The only training space we were provided was on the outdoor track, in the cold night.

But we succeeded. This year, we ’ ve run a team of 40 athletes, including 8 competitors at the USA Weightlifting National University Championships Our team placed 11th 15 of our athletes competed last month for the first time as well. We held our end of year banquet the next day, finally getting to celebrate our success as a team.

Now, I laugh while I train with my team on the UCLA track At home, I joke around with my older teammates, no longer feeling fear. I cheer for my teammates, and I coach my athletes. I lift for myself. I no longer need to be stoic. I smile on the platform when I compete, sharing my happiness with the world.

Maybe Elle (really) is for Limitless.

UCLA Club Olympic Weightlifting First Annual Banquet

TKD: THE IMPORTANCE OF STUDENT ATHLETES.

Whether it be over the summer or as a part time job, a majority of my peers are also student athletes who work by teaching their sports to others. During Covid, when K-12 students were unable to socialize and do their sports, taekwondo acted as a way for kids to understand self control and discipline. Having high school and college students teach kids was helpful for their socializing and communication skills. They stood as a role model to these young students and could empathize with them due to their close age, compared to older teachers and instructors.

Being a student athlete has also helped me manage my time and self awareness. Especially in a college environment where sometimes it feels like everybody for themselves, being a student athlete has helped me be a part of a supportive community and avoid myself from feeling too focused on my own success. YAERY MIN KOREAN AMERICAN TAEKWONDO ATHLETE AND INSTRUCTOR. FULL TIME STUDENT.

I am an athlete, assistant coach, and instructor I teach students of all ages, starting from ages 4 to 75. I assist classes with around 20-30 students and help them learn basic self defense like sparring and forms (basic hand and feet movements). I help plan trips for out of state and international competitions, manage finances, and ensure students are prepared for major competitions Aside from coaching, I am currently an athlete training for Nationals and Team Trials.

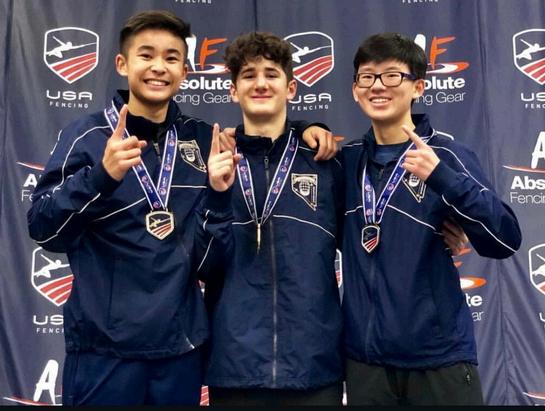

ON THE STRIP.

BY ALEX LEE

I still remember the first time I stepped onto the fencing strip in Las Vegas, gripping my epee tighter than I probably should have. The referee’s call echoed in the giant convention center: “En garde. Prêt. Allez.” And just like that, the bout began. Fencing is actually one of the few sports where Asian American athletes are highly visible. From local clubs to national competitions, I was surrounded by athletes who looked like me. It was one of the first places where being Asian American didn’t feel like an exception, it felt almost expected. I didn’t grow up speaking another language. I didn’t have a dramatic story of proving people wrong about my identity. But what I did have was a front-row seat to the power of seeing athletes like me succeed on the world stage. Park Sang-young, the 2016 Olympic gold medalist in men ’ s epee, became one of my biggest inspirations. Watching him make an incredible comeback to win gold for South Korea wasn’t just exciting, it was something I held onto every time I stepped onto the strip. He fenced with energy, confidence, and heart. It reminded me that fencing wasn’t just about physical skill, but about believing in yourself even when the score is against you. Of course, it wasn’t always easy. It’s still a sport where individual performance can feel isolating. You’re out there alone, face hidden behind a mask, trying to outthink your opponent with every move. There were tournaments where I doubted myself, where losses weighed heavier than they should have. But I kept coming back, not to chase medals, but to keep pushing my limits.

Fencing taught me focus, resilience, and strategy. But more than that, it taught me how important it is to have role models you can see yourself in. Seeing athletes like Park on the Olympic stage showed me what was possible, and being surrounded by other Asian American fencers reminded me that I wasn’t doing this alone. I never became a national champion. I didn’t fence in college. But every time I suited up and stepped on the strip, I carried the quiet confidence that I belonged there. And I hope that in some small way, I added to the story of Asian American athletes making their mark on the strip, and beyond.

Alex is a rising senior at UCLA that is currently studying Psychobiology He is originally from Las Vegas, Nevada and has lived there most of his life. Alex has only lived outside the city while attending college in Los Angeles He started fencing since a young age and competed in many competition. One fun fact about Alex is that he can whistle any song.

MASTER

OF THE BLADE.

MASTER OF THE BLADE. LUNG

BY BRANDON LEE

E FASTER.

FAST BLA

as Vegas, Nevada, before moving to San Marino, UCLA Fencing Club Team and West Coast Fencing ification, a milestone that reflects the dedication and

RAISING ATHLETES: A LIFETIME OF LEARNING.

BY TRACY HATAMIYA

Raising our kids, we prioritized giving them exposure to all kinds of experiences at young ages. For my two kids, this meant activities such as dance, carpentry, soccer, cooking, guitar, and martial arts. I didn’t have any investment in which activities they grew to love. I wasn’t trying to create a ballerina, a musician, or even an athlete. I just wanted my kids to find what they loved and pursue their interests as far as they choose to take them. As it turns out, what spoke most to their passions were gymnastics, Olympic Weightlifting, and baseball.

Raising athletes necessitates learning. I’ve picked up the rules and standards for judging skills and proper form for gymnastics and weightlifting competitions. I’ve absorbed the ins and outs of baseball rules, and an endless stream of the minute details of baseball I.Q. and game strategy.

Another aspect of my breadth of knowledge is recovery and rehabilitation Gymnastics and baseball have caused innumerable injuries in my kids. My collection of x-rays in my phone album is way too big.

Once, an orthopedist told my daughter that if she kept doing gymnastics, she’d keep getting injured. She eventually did retire from gymnastics in 2021, and her injuries have stopped. Thank goodness Olympic Weightlifting is one of the lowest injury sports.

My son is a left-handed pitcher, and this has caused a lot of injuries, as well. Baseball is not a contact sport, but that doesn’t stop the players from having collisions, getting hit with a baseball or a bat, jamming their cleats in the turf and wrenching their ankle, or

gymnastics world for so blowing out their elbow from the immense torque of throwing the ball at high velocities. Over the years, we ’ ve developed a routine for arm care, comprising Epsom salt baths, twice daily Tiger balm massages, supplements, and osteopathy treatments. This is all in addition to the stretching, workouts, band warmups, and throwing programming that my son does while at the baseball field and in the gym.

Mental strength and mental health is another aspect of sports from which we have learned. I’ve always told my kids the most important thing is that they enjoy their sport and want to keep doing it. Seeing how hard they train, there’s nothing worse to imagine than them doing it against their will. Besides that being a sad prospect, you need to be locked in, or you’ll get hurt. So when my daughter became unenthusiastic and

unhappy about her daily gymnastics practices, I knew it was time for her to stop. She had been ensconced in the many years, I knew she couldn’t imagine stopping. But a combination of mean coaches and burnout conspired to steal from her the joy of flying through the air and improving her considerable skills. Weightlifting is a more supportive and positive atmosphere for her. As a youth lifter, my daughter trained alone, but as an adult she has friends to train with and teams to compete with. She created a weightlifting community at UCLA by founding the Olympic Weightlifting Club Sport team.

In contrast, my son has never wavered in his love for pitching. Over time, he’s taken more and more agency over his training, choosing his coaches, and pursuing his long-held goal of playing at the highest

levels This past fall, he committed to pitch in college, as the exciting culmination of 12 years of developing his craft.

Competitive sports have enriched our family immensely over the past two decades. Our kids have learned body awareness and discipline, teamwork and leadership, the importance of food and rest, and how to coach. As well as boundaries such as the limits of their bodies when training, what bad coaching looks like, and sportsmanship versus trash talk. They have both been fortunate to continue competing in their chosen sports in college. As parents we ’ ve prioritized sports as quality time we spend together, learned the ins and outs of the sports, discovered how to best support our athletes to reach their potentials in their sports, and gained friendships with team families and coaches.

I am an Asian American mom who has raised two athletes with my Asian American husband in Albany, California. I’m obsessed with knitting and spinning my own yarn, and I love watching my kids grow into full people and compete in their sports.

EAT SLEEP SWIM REPEAT.

BY JASMINE VO

Being an Asian American athlete was one of the most challenging yet rewarding experiences of my life. In the beginning, I often felt invisible. I was overlooked during practices and competitions, and it was hard to feel like I truly belonged.

That began to change when I found a group of teammates who were also Asian American. Being around people who shared similar experiences helped me find my voice and gain confidence. Their support pushed me to grow, not just as an athlete, but as a leader. For the first time, I felt like I could show my full potential without holding back.

We built a strong bond through shared experiences and cultural understanding. One of my favorite memories was after we won league finals during our senior year We all decided to celebrate by going out for Korean BBQ, and we ended up spending hours reminiscing about our time on the team and the moments that brought us closer together.

Without these teammates, I don't think I would have had the courage to become team captain or earn the Coach’s Award. They made me feel seen, and that sense of belonging helped me succeed in more ways than I ever expected.

Jasmine Vo is a Vietnamese-American first year transfer at UCLA. All through middle and high school she did competitive swimming, and won several awards while being on the swim team, including the Coach's Award and Scholar Athletic Award. She loves being in or around the water, whether it is a pool or ocean. In my free time, she likes to try new coffee shops and hang out with friends

A BRIEF ESCAPADE INTO EUROPEAN ATHLETICS AS AN ASIAN AMERICAN DURING STUDY ABROAD.

THE AFTERMATH OF WINNING THE DANISH ULTIMATE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS

IT SWIMS IN THE FAMILY.

SPORTS ALWAYS GLUED MY FAMILY TOGETHER.

I started swimming only because I was a young child and all I knew was that whatever my best friend at school did, I wanted to do. I HATED swimming; I was completely afraid of the water. And yet I swam on, and my fear of the water turned into a deep love for the sport. I would go on to swim throughout middle school and high school, on club and school teams.

My younger sister, Zoe, started swimming around the same time as me, and we share a lot of fond memories in the pool. We had one special year of crossover on our high school team. As the sister closest to me in age, we did a lot of things together, especially sports, from ice skating to soccer. Swimming was what really stuck. My other younger sister, Sofie, also started swimming on our city’s club team before joining the same high school team as a freshman this year. My little brother, Jasper, is now swimming on the city team. In short swimming runs (or swims) in the family.

Swimming will always be something I hold close to my heart. I loved the sport for what it was, but it had always been more about the people it connected me to. From my coaches to my school friends to my siblings, swimming was a place where I cultivated care for others and learned work ethic and sportsmanship. Although I haven’t swam on a team since starting college, being in the water boosts my serotonin levels like nothing else. My love for swimming lives on in my siblings.

My siblings and I at a Dodgers game in summer of 2023.

In the last five years, a new sport has cemented itself as glue in my family: baseball

When the world went on lockdown in 2020, my dad would turn on the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball games on our living room TV. It was a consistent source of entertainment, and soon enough Zoe and I were asking my dad to explain the sport to us. Zoe and I grew to love not only the sport, but the team, its players, and the fan culture. Becoming a Dodgers fan was one of the best things that came out of the pandemic. The team helped me grow closer to my father, and when it was announced that Dodgers Stadium was going to be open for attendance during the 2021 season, my sister, dad, and I immeditately bought tickets to attend a game together.

Since then, my family has been to countless Dodgers games, whether it be just my sister, dad, and I, or with other family members. The Dodgers and baseball continues to be something me and my dad can always talk about, and I am thankful for what the sport has done to bring me closer to my family.

While the Dodgers continue to gain more and more popularity and tickets become more and more expensive, the team will always mean a lot to me personally. The sport has birthed some of the best memories, got me through lockdown, led me to get into other sports, helped me meet some great people, and inspired me to pursue sports journalism at UCLA.

I am happy to say I have witnessed two World Series wins with the team, and I look forward to being here with my family for many, many, more. Go Dodgers!

Chloe Nimpoeno loves all things family and sports She has strong opinions on the Dodgers and Formula 1 and occasionally writes about them.

MATCH POINT: FINDING MYSELF ON THE COURT.

BY MELANIE NARCISO

My experience as an Asian American athlete was one of the most defining parts of my high school years and has had a lasting impact on how I see myself today. Playing tennis both as an individual and a team sport, has taught me discipline, perseverance, and most importantly, the value of community and support. Being on a tennis team that was made up mostly of other Asian American girls made me feel seen and understood in a way I hadn’t always felt in other spaces. We connected so naturally from sharing inside jokes about childhood snacks like Hi-Chew and Pocky, to cheering each other on during long matches.

We weren’t just teammates we were each other's support systems. Whether someone won or lost their set, we were always on the sidelines encouraging and lifting each other up. Those moments built a bond that went far

beyond the court. Competing against schools across Southern California, we saw a wide range of team cultures and demographics, and it made me appreciate how special it was to have a team where I felt culturally and emotionally connected.

Tennis wasn’t just an extracurricular or a way to skip P.E. it was where I grew, where I built confidence, and where I found some of my closest friendships. Being an Asian American athlete helped me embrace both my identity and my strength, and that experience will always stay with me.

Melanie Narciso is a third year nursing major. She is a former Asian American athlete who plays tennis casually Although her love for the sport came later in her teenage years, the passion and ambition to grow within the sport was strong enough to keep her playing currently.

TO BE OR NOT TO BE AN APIDA ATHLETE.

A humorous pros/cons list of being an Asian American athlete.

BY MAYA SALVITTI

If you, like me, have found yourself thrust into a life of competitive sports starting all the way from mommy-and-me classes, and if you, like me, have found yourself to be Asian American, then you may have also found that you don’t look like the vast majority of your teammates or role models. Sure, we have our Naomi Osakas, our Suni Lees, and Shohei Ohtani’s, and they’re nothing to sneeze at, but we ’ re putting an awful lot on their shoulders. Think of the thousands of Asian American children forced to share the few Asian role models who were tall enough to become high-level athletes. If you play ping pong, you ’ re probably set, but hopefully you don’t play basketball because you’d be lucky to even get a hapa to look up to and tack on your wall.

If you are Asian American and were not thrust upon sports but are questioning entering that world, here is a list of pros and cons of being an Asian American athlete (specifically in the college setting) that I have conveniently laid out for you.

Maya Salvitti is a half-Japanese athlete on the UCLA diving team. She did about seven years of competitive gymnastics before switching to diving at 11 years old, and she has been diving ever since. Maya is about to graduate from UCLA and do a final year of diving at University of Idaho to obtain her masters.

PROS CONS

Your shorter-than-average height comes in handy for gymnastics and other acrobatic sports where height is actually a disadvantage and could be grounds to get you kicked off the team

The lack of Asian American representation in sports means that if you find yourself to be successful in this realm, you will feel even more special.

Your shorter-than-average height will make the vast majority of sports unavailable to you.

The lack of Asian American representation in sports.

Your Asian skin will largely stay unblemished by the elements, and if you are an athlete in a water sport as I am, chlorine’s crusade against healthy skin will be unsuccessful.

Your Asian skin will stay unblemished by the elements, resulting in many a teammate (and coach on some occasions) requesting a skin care routine to which you can reply with only a shrug and what hopefully comes off as a comiserating grimace as you suggest that they may try incorporating a few Asian genes into their genetic makeup.

Stereotypes such as the model minority myth mean that you will generally be seen by teammates and coaches as a model citizen and hardworking athlete. This means that you will be less likely to be selected for 5 am drug testing.

You have at least one Asian parent, meaning that you were likely trained in either violin or piano. This means you will have something to fall back on if your height becomes too high an obstacle to overcome (pun intended).

Stereotypes such as the model minority myth.

You have at least one Asian parent, meaning that you were likely trained in either violin or piano. If you answered yes to both, the addition of rigorous physical exercise on top of these other pursuits could lead to adverse health issues.

If you have a name remotely similar to another asian athlete (i.e. Chang and Cheng, Wang or Wong, Lee and Lee), you will likely be mixed up, allowing you to pass the blame for your mistakes onto your fellow Lee.

If you have a name remotely similar to another asian athlete (i.e. Chang and Cheng, Wang or Wong, Lee and Lee), you will likely have your pictures mixed up on the roster (and yes, this really happened).

You know all the best post-practice restaurants because Asian food is superior.

If you are lucky to have an Asian coach who speaks your home language, you have the pleasure of being spoken to in a language you ’ re comfortable with and that only you can understand, fostering a deeper connection with your coach.

Unfortunately, you are not in charge of team catering, so you will find yourself inundated with American food from the likes of Chili’s and Red Robin Even on the off chance that “Asian” has been selected as the flavor of the day, it will be American Asian food, which you and I both know is not the same.

If you are lucky to have an Asian coach who speaks your home language, you have the pleasure of being cussed at in a language you ’ re comfortable with and that only you can understand while your teammates look on, puzzled and concerned.

People will assume your major is within the realm of STEM, which will impress people with your ability to juggle a rigorous academic load with a rigorous practice schedule.

People will assume your major is within the realm of STEM, and if it is, that’s punishment enough. On the other hand, if you ’ re an English major like me, you will lack the ability to calculate the most optimal velocity and angle to throw a ball or lau yourself off a spri Your ability to an Shakespeare will not be advantage in a sports setting

I hope this list was helpful in aiding your decision. As you can see, there are many ups and downs to being an APIDA member of an athletic team, but all in all, it is an experience that I wouldn’t trade for anything, and who knows? Maybe you’ll be the next Naomi Osaka or Shohei Ohtani, and for their sakes, I hope you do They need someone to lighten the load.

EDITOR’S NOTE.

ELLE HATAMIYA

Elle Hatamiya is a 19-year-old Psychology and Asian American Studies student at UCLA. As an ex-gymnast and current competitive weightlifter, she is passionate about the athlete experience, mental health, and coaching. At UCLA, along with being the president and founder of the Club Sport Olympic Weightlifting Team, Elle one of the managing editors for Pacific Ties, UCLA’s APIDA newsmagazine. She describes herself as an advocator, a creator, an athlete, and an artist.

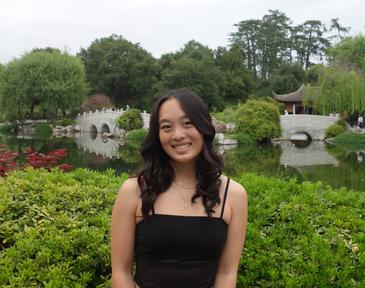

CHLOE NIMPOENO

Chloe Nimpoeno is a 21-year-old English and Asian American Studies student at UCLA. Chloe spent most of her childhood and teenage years in the pool, from swim lessons to the high school varsity team to lifeguarding. Out of the water, she spends her time supporting the Los Angeles Dodgers and Formula 1, covering UCLA sports for BruinLife, and writing. As a former athlete, current sports journalist, and forever fan, Chloe hopes to strengthen the connection between identity, community, and sports.

ISAAC CHENG

Isaac Cheng is a 20-year-old Economics Major at UCLA, As an previous multi-sports athlete in high school, He loves talking about his athletic experience in the bay area. Growing up both in Hong Kong and Bay Area, Isaac was able to experience the perspectives of living in different countries. As a huge sport fan as well, Isaac hopes to showcase and promote more of Asian American athletes to a bigger audience and teach others about their experience.