download ebook at ebookgate.com

PoemsofloveandwarfromtheEight anthologiesandtheTenlongpoemsof classicalTamilA.K.Ramanujan

https://ebookgate.com/product/poems-of-love-andwar-from-the-eight-anthologies-and-the-ten-longpoems-of-classical-tamil-a-k-ramanujan/

Download more ebook from https://ebookgate.com

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

The Collected Essays of A K Ramanujan A. K. Ramanujan

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-collected-essays-of-a-kramanujan-a-k-ramanujan/

The Poems of Sextus Propertius Sextus Propertius

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-poems-of-sextus-propertiussextus-propertius/

The Poems of Catullus A Bilingual Edition Gaius

Valerius Catullus

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-poems-of-catullus-a-bilingualedition-gaius-valerius-catullus/

The Oxford India Ramanujan Oxford India Collection 1st Edition A. K. Ramanujan

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-oxford-india-ramanujan-oxfordindia-collection-1st-edition-a-k-ramanujan/

The Collected Poems of Barbara Guest Barbara Guest

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-collected-poems-of-barbaraguest-barbara-guest/

Companion of Life Poems from Zimbabwe 1st Edition

Munyaradzi Mawere

https://ebookgate.com/product/companion-of-life-poems-fromzimbabwe-1st-edition-munyaradzi-mawere/

Selections from the Poems of Paulinus of Nola Including the Correspondence with Ausonius 1st Edition Alex Dressler

https://ebookgate.com/product/selections-from-the-poems-ofpaulinus-of-nola-including-the-correspondence-with-ausonius-1stedition-alex-dressler/

The Poems of Mao Zedong 1st Edition Mao Zedong

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-poems-of-mao-zedong-1stedition-mao-zedong/

The Collected Poems of Philip Lamantia First Edition

Philip Lamantia

https://ebookgate.com/product/the-collected-poems-of-philiplamantia-first-edition-philip-lamantia/

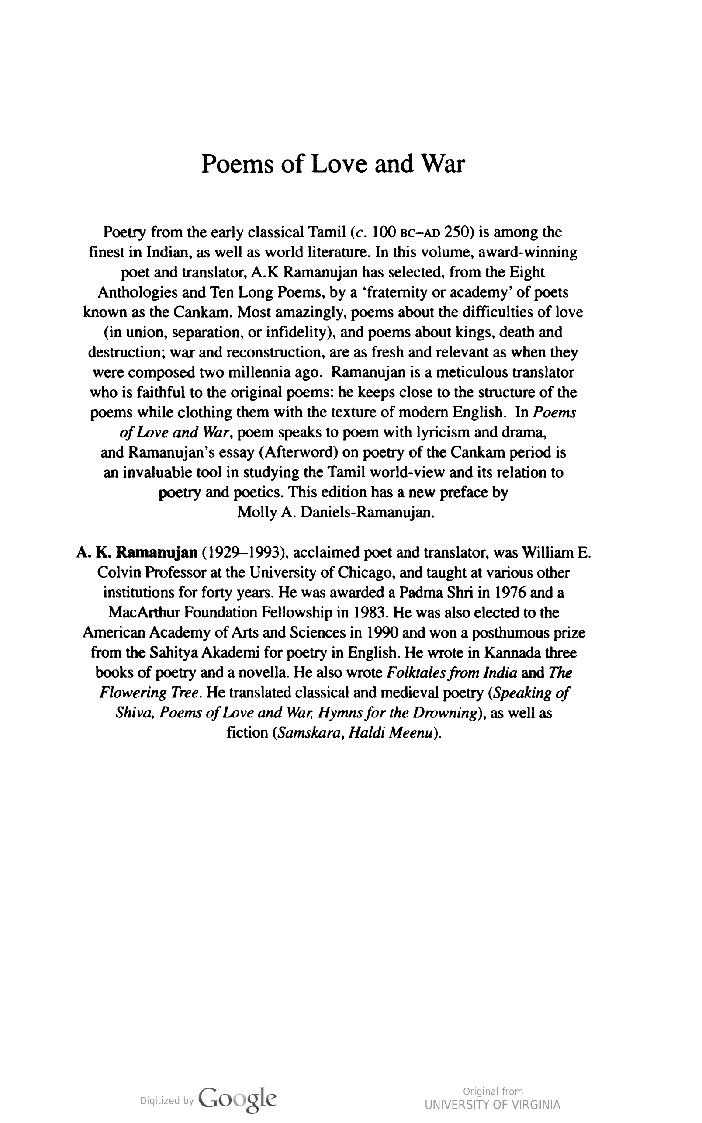

Poetry from the early classical Tamil ( c . 100 BC - AD 250 ) is among the finest in Indian , as well as world literature . In this volume , award - winning

poet and translator , A . K Ramanujan has selected , from the Eight Anthologies and Ten Long Poems , by a ‘ fraternity or academy ' of poets known as the

esh and relevant as when they were e structure of the poems while

of Love and War , poem speaks to poem with lyricism and drama , and Ramanujan ' s essay ( Afterword ) on poetry of the Cankam period is an invaluable tool in dma Shri in 1976 and a

o the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1990 and won a posthumous prize from the Sahitya Akademi for poetry in English . He wrote in Kannada three books of poetry and a novella . He also wrote Folktales from India and The Flowering Tree .

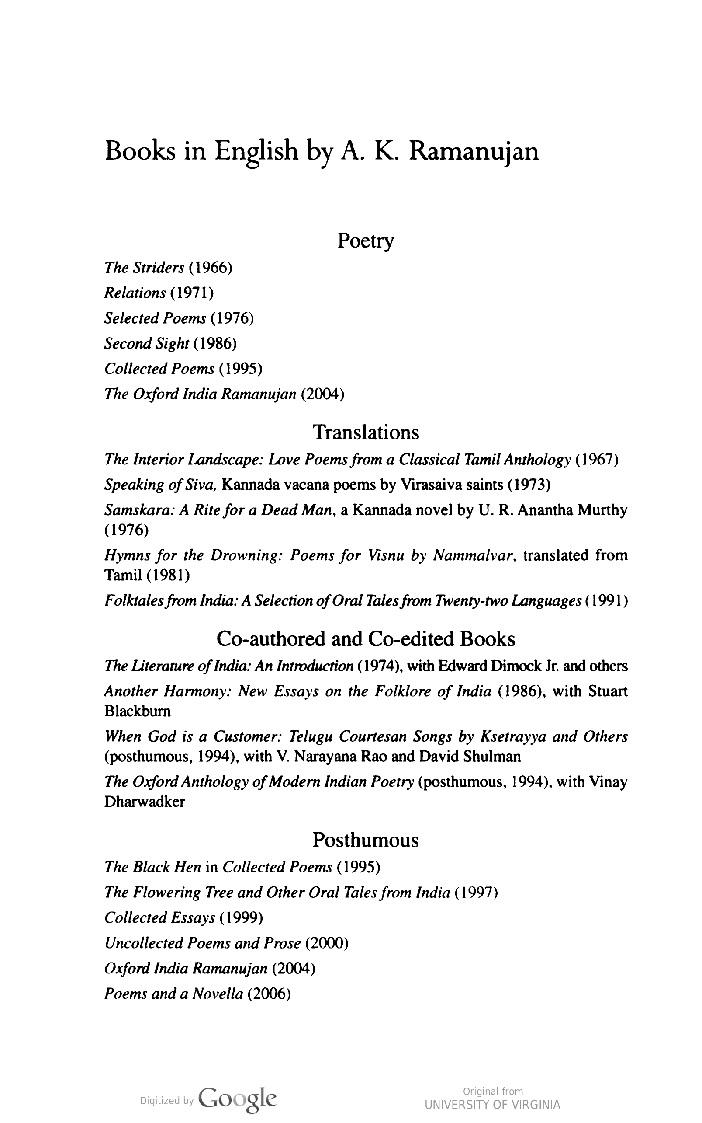

Poetry The Striders ( 1966 ) Relations ( 1971 ) Selected Poems ( 1976 ) Second Sight ( 1986 ) Collected Poems ( 1995 ) The Oxford India Ramanujan ( 2004 )

Translations The Interior Landscape : Love Poems from a Classical Tamil Anthology ( 1967 ) Speaking of Siva , Kannada vacana poems by Virasaiva saints ( 1973 ) Samskara : A Rite for a Dead Man , a Kannada novel by U . R . Anantha Murthy ( 1976 ) Hymns for the Drowning : Poems for Visnu by Nammalvar ,

Co - authored and Co - edited Books The Literature of India : An Introduction ( 1974 ) , with Edward Dimock Jr . and others Another Harmony : New Essays on the Folklore of India ( 1986 ) , with Stuart Blackburn When God is a Customer : Telugu Courtesan Songs by Ksetrayya and Others ( posthumous , 1994 ) , with

Posthumous The Black Hen in Collected Poems ( 1995 ) The Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India ( 1997 ) Collected Essays ( 1999 ) Uncollected

ord University Press . Enquiries

A great translator has the gift of two languages , as well as a third language , the language of the heart . He must also have an intimate knowledge of the known r time , and another place ; he must ed ignominy ; he must learn to

A translator has to be a poet in training . He must find mentors growing on every bush . In 1961 , Ramanujan attended Samuel Yellen ' s poetry writing workshop . One assignment required rhymed couplets , but then Yellen would say , " Now throw out the rhymes . ' In case a rhyme refused to budge , it could be buried ing in verse with end - words , as William Blake did , but it was equally important to be listening to one ' s own spoken voice . With the exception of Robert Frost , modern poets found English to be notoriously deficient in rhymes ; they compensated by opening

st anthologies of love and war (

2 when he started translating the love

as to a clarion to the sage instructions in Tolkapiyum , a grammar of rhetoric , written by Tolkappiyar ( second century AD ) . The Cankam ( academy ) became his alma mater . As he worked on into middle age , the Poems of Love and War , from the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil , renewed him many times . Ramanujan has described how he came to receive this gift from his

' s sake , especially as he was far from

) love poems from the classical Tamil Anthology ( The Interior Landscape , 1967 ) ; 2 ) medieval Kannada metaphysical poems by four Virasaiva saints ( Speaking of Siva , 1973 ) ; 3 ) Tamil ng , 1981 ) ; and 4 ) the present volume from the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long

an experience the same alchemy ugh these four books would find his own rom Colonial to Pre - Colonial ,

. A few archaic attempts existed , but those yellowing pages were hard to read . Unlike the earlier a poem rather than translating at

e . Though Ramanujan was not by any means a brilliant linguist , linguistics also served him well ,

r figurative language . Added to this , he was at home with a wide range of poets ; in his Chicago ( Shakespeare , the metaphysical poets , the Augustans , and the poetry of W . B . Yeats ) , new ones ( Wallace Stevens , William Carlos Williams , and Cesar Vallejo ) . Actually , he read most lapidarian , but he could be tutored

With the marriage of traditional form and the language of modern usage the greatness of classical Tamil literature became evident to readers . In Ramanujan ' s lly it might have been a myrobalan . I

As he continued to work on Poems of Love and War , his own poems began to be able to say the most complicated things with a minimum of words . He learned es . He learned to use the telling

Poetry or of War Poetry to match

Tamil , one of the two classical languages of India , is a Dravidian language spoken today by 50 million Indians , mainly in Tamilnadu State ( formerly Madras )

In this book , Poems of Love and War , I attempt trans lations of old Tamil poems selected from anthologies com piled about two millennia ago . Today we have 00 poets . These poems are “ classical , ” i . e . , early , ancient ; they are also “ classics , " i . e e and major poetic achievement of

Early classical Tamil literature ( c . 100 B . C . - A . D . 250 ) consists of the Eight Anthologies ( Ettuttokai ) , the Ten Long Poems ( Pattuppattu ) , and a

yam or the “ Old Composition . ” ' 3 The poems in this book are selected from the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems ; sections of the Tolkāppiyam are used to develop a commentary on Tamil poetry and poetics . Apart from some epigraphic and archaeological evidence , the classical liter ature is the most

The literature of classical Tamil later came to be known as Cankam ( pronounced Sangam ) literature . The word does not occur in the poems . Cankam means " s , lasting 4 , 440 , 3 , 700 , and s , and kings as poets . A whole my thology grew around the poems and poets ; especially pop ular oms and a large body of literature . Such myths certainly point to a long poetic tradition , with much of it lost in the great flood of time . All the works of the first Cankam are said to be lost ; only the grammar Tolkāppiyam remains of the second ; the Eight

Cankam poems vary in length from 3 to over 800 lines . There are 2 , 381 Cankam poems , of which 102 are anony mous ( Vaiyāpuri Piļļai 1940 ) . Nearly half oets are known by proper names or by epithets . The largest number assigned to any poet is 235 , to Kapilar ; next to him stands Ammüvaņar with 127 poems . Five poets are represented by over 100 poems ; 293 poets are represented by a single poem .

p . 102 ) is by Villakavirali ņār , “ The Poet of the Fingers Around the Bow . ” Poets were known by

These classics were not always known to the Tamils themselves . They were dramatically rediscovered in the later decades of the nineteenth century , a period of ma terials . The great texts of classical Tamil literature , includ ing the Eight Anthologies and the Twin Epics ( Cilappati kāram and Manimekalai ) were inaccessible to most scholars all through the early nineteenth century , though they were known and had u scholars , devout worshipers of Śiva or Vişņu , had tabooed as irreligious all secular and non Hindu texts , which included the classical Tamil antholo gies . They also disallowed the study of Jain and Buddhist texts , which included the Twin Epics . Under

tion and taboo , even the finest of Tamil scholars , such as Cămināta Aiyar ( who is the hero of this section ) , had to give their days and nights of impassioned

Cāmināta Aiyar ( 1855 – 1942 ) , a man of vast learning , was entirely unaware even of the existence of the breath taking epics and anthologies of early Tamil , macuvāmi Mutaliyār , in a small temple town , Kumpakāņam . Aiyar records the date of this Thursday . To him , as to all students of Tamil literature , this date is " etched in red letters . ” The munsif had just been transferred to that small town . When Aiyar met him , the judge asked him what he had studied and under whom . Aiyar named his well d commentaries he had labored over . The judge , unimpressed , asked him , " That ' s all ? What . Aiyar , one of the most erudite and thoroughgoing of Tamil scholars , was ' aghast that he had not even heard of them . The judge then gave him a handwrit ten manuscript to take home and read . In his autobiogra phy ( the chapter is called “ What Is the Use ? ” ) , Aiyar says the good fortune of his past lives took him there that Thursday and opened a new life for him . Cāmināta Aiyar , who was 44 then , devoted thing , editing , and printing classical

It is to him and to his peers , such as Ci . Vay . Tāmo taram Pilļai ( 1832 – 1901 ) , that we owe our knowledge of this major tradition . They rescued manuscripts

mains ; even of that , termites and the bug named Rama ' s Ar row take a toll ; the third element , earth , has its share . . . . When you untie a knot , the leaf cracks . When you turn a leaf , it breaks in half . . . . Old manuscripts are crumbling and there is no one

and interpolations . Texts differed greatly from copy to copy . ( The work of rigorous modern re vered . Each community studied a Jain text , important emen dations were likely to be made . A few kings and rich men arranged for copies to be made when the old manuscripts fell apart . The scribes had to be well chosen and well paid . If someone wished to read a book , he had to go in od reason . They were guarded like treasures and passed from generation to generation in the

the Tamil area ( with one famous exception , Manimekalai ) , is that no one preserved them or copied them after the Hindu Saivites and Vaişņavites triumphed over Buddhism . Jain manuscripts survived very well , because of a ritual practice called ons like weddings . Regarding the

Written texts , and among them the very classics that are the pride of Tamils today , were thus precariously , ex pensively , often only accidentally , transmitted . The story of Cămināta Aiyar dramatizes the transition from palm leaf to print , from a period of private sectarian ownership of texts to a period of free access to

ified by their themes as akam and puram . Akam ( pro nounced aham ) meant “ interior , " puram “ exterior . ” Akam poems were love poems ; puram poems were poems on war , kings , death , etc . The two types of poems had differing properties . Three te both kinds of poems .

and one of puram . The akam poems are presented in five sections , as they are in several of the s , and the wilderness ( or desert ) . Each n : kuriñci , a mountain flower ; neytal

thologies , though such a classification is often implied . As foci for poems , certain situations (

. So I have arranged these poems under five themes : Kings at War , Poets and Dancers , assical poems ( c . fifth to sixth century ) , poems in a different key . The third offers some comic , n unusual poem on the bull fight contests of the time . The fourth and last book includes a long hymn to Vişnu , one of the earliest examples of its kind in Indian literature , and two pieces from the long poem , " A Guide to Lord Murukan ” ( Tirumurukār ruppațai ) . The erotic and heroic motifs of akam and puram are imaginatively reworked in these kan , who appear earlier in Tamil poetry than anywhere else , appear as gods of love and war . In

oetry comes first ) : an essay on the Tamil world picture and its relation to Tamil poetry and several times that I had finished it . Translations too , being poems , are “ never finished , only

r who gave me more than a

vice have been a mainstay , and not ending with the Tamil scholars past and present , and fellow workers in different parts of the world , such as Kamil Zvelebil , K . Kailasapathy , and George Hart . The latest of these debts is to two colleagues , Rajam ainst her deep and meticulous knowledge of the Tamil texts , offered many suggestions , corrected many er rors . Keith Harrison , poet and translator , read them all in more than one version , cience that often spoke more clearly to their expert advice . The notes and er , Paula Richman , Vinay Dharwadker , and Robert Tis dale were helpful in reworking these

Dimock , Jr . and Paul Wheatley , and Dean Karl Weintraub have been infinitely helpful in difficult mo ments , and they supported me even on ordinary days . Their friendship , as that of colleagues in the Department of South Asian Languages and the Committee on Social Thought ( especially of Wendy O ' Flaherty and David Grene ) , has been a source of pleasure , ideas , energy . I worked on the last drafts in a third - floor office of the Department of English at Carleton College where I sat unsociably day after day agonizing over Tamil particles and English

o be earned , repossessed . The old bards earned it by ap prenticing themselves to the masters . One it some times in faraway places , as I ibrary in search of an elementary grammar of Old Tamil , which I had never learned . The University had just acquired a large collection • of books from a famous South Indian historian . It was still uncatalogued , even undusted . As I searched , hoping to find a school grammar , I came upon an early anthology of clas sical Tamil poems , edited in 1937 by U . Vē . Cāminātaiyar . It carried his Tamil signature , dated 1937 , on its flyleaf . That edition , I later learned , was a landmark in its own right . I sat down on the floor between the stacks and began to browse . To my amazement , I found the prose commentary transparent ; it soon unlocked the old poems for me . As age and culture , to which I had been

That collection of Tamil books was there thanks to Milton Singer and his colleagues , who had decided to bring South Asia to Chicago . It is but fitting that I

not only in a variety of anthologies but in wedding services . The ancient poets composed in Tamil for their Tamil corner of the world of antiquity ; but , as noth ing human is alien , they have

ght beetle - holes in the waving bamboos . The sweet sound of waterfalls is continuous , dense as drums . The urgent lowing voices of a herd of stags are oboes , the bees on the flowering slopes become lutes . Excited by such teeming voices , an audience

h an arrow buried in its side . He

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Slaves—a male slave is worth in Cashna, from 3l. 10s. to 5l.—a female slave is worth two-thirds of the amount, or from 2l. 6s. 8d. to 3l. 6s. 8d.

Cotton Cloths—of various colours, principally blue and white, of which in the Empire of Cashna, and in the Negro States to the South of the Niger, great quantities are made:

Goat Skins—dyed red or yellow, Ox and Buffalo Hides—for tents,

Senna from Agadez a province of the Cashna Empire; the Agadez senna is worth at Tripoli, from fourteen to fifteen mahaboobs (4l. 4s. to 4l. 10s. sterling) per hundred weight; that which the Fezzanners obtain at Tibesti is only worth per hundred weight, from nine to ten mahaboobs, or from 2l. 14s. to 3l. sterling.

Civet.

To such of the various nations inhabiting the Country on the SouthoftheNigeras they are accustomed to visit, the Merchants of Fezzan convey the following articles:

Sabre Blades, Dutch Knives, Carpets, Coral, Beads, Looking-Glasses, Brass, Imperial Dollars, Civet.

In returnthe Merchants receive— Gold Dust, Slaves,

Cotton Cloths—of various colours.

Goat Skins—red and yellow.

Ox and Buffalo Hides,

Gooroo Nuts—for sale in Cashna, Bornou, and Fezzan, where they are purchased at the rate of 12s. for one hundred pods:

Cowries—for sale in Cashna.

Ivory, though very common in the country to the South of the Niger, is not considered by the Merchants of Fezzan, as an article of profitable transport, the demand for it on the Coast being such as induces them to sell to the Negros who traffic there, the teeth which in the course of their journey, they often find in the woods.[34]

Such are the principal branches of the extensive commerce of the Merchants of Fezzan; from a view of which it appears, that, vast as their concerns are, they have little communication with any of the States that are situated to the West of the Empire of Cashna; a circumstance which the Shereef ascribes to the want of a proper conveyance for their goods; for the country on the West of Cashna furnishes but few camels, and even horses and mules are singularly scarce and dear.

CHAPTER X.

RoutfromMourzouktoGrandCairo,accordingtoHadgeeAbdalah Benmileitan,thepresentGovernorofMesurata.

PLACED in a situation which affords an easy intercourse with the Mediterranean, and therefore with the States of Europe, on the one hand, and on the other with the extensive Empires of Bornou and Cashna, the dominions of Tombuctou, and the various nations of Negros to the South of the Niger, the Merchants of Fezzan are happily possessed of the farther advantage of communicating by a safe and comparatively commodious passage with the Cities of Grand Cairo and of Mecca. A pilgrimage to the latter, the object, from time immemorial, of veneration in Arabia, is prescribed to every Musselman; and though the greatest part of the believers in Mahomet, deterred by distance, or restrained by the avocations of business and the feelings of domestic attachment, content themselves with imperfect resolutions of performing at some future period this arduous journey, yet there are persons, even from the innermost recesses of Africa, who think, that a positive injunction of their faith is too solemn for excuses, and too momentous for delay. Prompted by this urgent consideration, or allured by the honourable distinction which attends upon the title of Hadgee, the envied appellation of those who have visited the sacred Temple, a number of the faithful from the Empires of Bornou and Cashna, from the extensive kingdom of Caffaba, and from several of the Negro States, resort to Fezzan, and proceed from thence, with the caravan, which in the Autumn of every second or third year takes its departure for Mecca. The caravan, which seldom consists of less than one hundred, or of more than three hundred Travellers, assembles at

Mourzouk, and begins its journey in the last week of October, or in the first of the succeeding month.

Temissa, a town in the dominions of Fezzan, and situated to the East North East of Mourzouk, receives them at the close of the seventh day; and in two days more, of easy travelling, they arrive at a lofty mountain, rocky, uninhabited, and barren, of the name of Xanibba. Having recruited their goat-skin bags from the only well which these sullen heights afford, they descend to a vast and dreary desart, whose hilly surface, for four successive days, presents nothing to the eye but one continued extent of black and naked rock; to which, for three days more, the equally barren view of a soft and sandy stone succeeds. Through all this wide expanse of varied nakedness no trace of animal or vegetable life, not even the desart thorn, is seen. On the eighth day, the vast mountain of Ziltan, the rugged sides of which are marked with scanty spots of brushwood, and are enriched with stores of water, increases the labour of the journey. Four days are devoted to the toils of this stupendous passage; four others are employed in crossing the sultry plain that stretches its barren sands from the foot of the mountain to the verdant heights of Sibbeel, where the wells of water and the chearing view of multitudes of antelopes suspend their fatigues, and anticipate the refreshments that await them on the next evening; for the close of the following day conducts them to the town of Augéla.

From that place, which is subject to Tripoli, and is famed for the abundance and excellent flavour of its dates, they proceed in one day to the little village of Gui Xarrah; another brings them to the long ascent of the broad mountain of Gerdóbah, from whose inflexible barrenness the Traveller, in the course of a five days passage, can only collect a scanty supply of unpalatable water. Descending from these mournful highlands, he enters the narrow plain of Gegabib, sandy and uninhabited, yet fertile in dates, which the people of Duna (a town dependant on Tripoli, and situated on the Coast at the distance of eight days journey from Gegabib) annually gather.

From this scene of gladsome contrast to the inveterate rocks of Gerdóbah, a three days march conducts the caravan to another desolate mountain of the name of Buselema, that furnishes only water; and in three days more they enter the dominions of the independent Republic of See-wah.

Governed by a Council of six or eight Elders, whose lasting dissentions divide the opinions and distract the allegiance of the people, this unfortunate State is constantly involved in the miseries of intestine war. Its chief produce is the date tree; for the lands, though not destitute of water, furnish but little corn.

From See-wah, the capital, the caravan proceeds in a single day to the miserable village of Umseguér, which is one of the dependencies of the State, and is situated at the foot of the mountainous Desart of Le Mágra, where, in the long course of a seven days passage, the Traveller is scarcely sensible that a few spots of thin and meagre brushwood slightly interrupt the vast expanse of sterility, and diminish the amplitude of desolation. The eighth day terminates with his arrival at the hill of Huaddy L’Ottrón, which is distinguished by a small convent, of three Christian Monks, who reside there under the protection of Cairo, and to whose hospitable entertainment the Traveller is largely indebted. Buildings, surrounded with high walls, and erected in the neighbourhood of the convent, are opened for his reception; and for three successive days, if he chuses to be their guest so long, his wants, as far as their means extend, are chearfully and liberally supplied.

Their garden, in which is a well of excellent and never-failing water, affords an ample store of vegetables of various kinds; the maintenance of a few sheep is furnished by an adjoining pasture; and they raise, without difficulty, a numerous breed of fowls. All other articles, except their bread, which they manufacture themselves, they receive from Cairo.

Respected by the Arabs, who revere their hospitality more than they hate their religion, these venerable men are apparently secure. —Yet as too much confidence might invite the meanest plunderers to

invade their peaceful dwelling, they have cautiously guarded their convent by a separate and lofty inclosure from an opening in which a ladder of ropes furnishes the means of descent.

Leaving this hospitable hill with such refreshments as the generous Fathers could supply, the caravan continues its course, and on the fifth day arrives at the City of Cairo, from whence, at the usual season, it proceeds by the customary rout to Mecca.