september 18

—october 23 2025 portraits of india Blossom the The & Sword

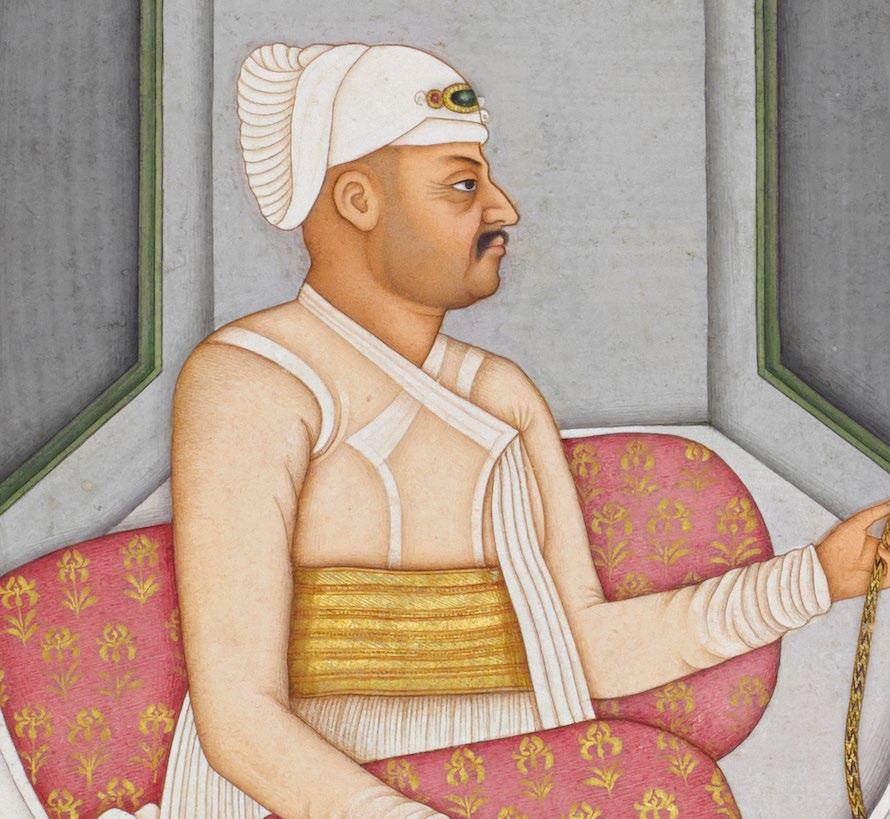

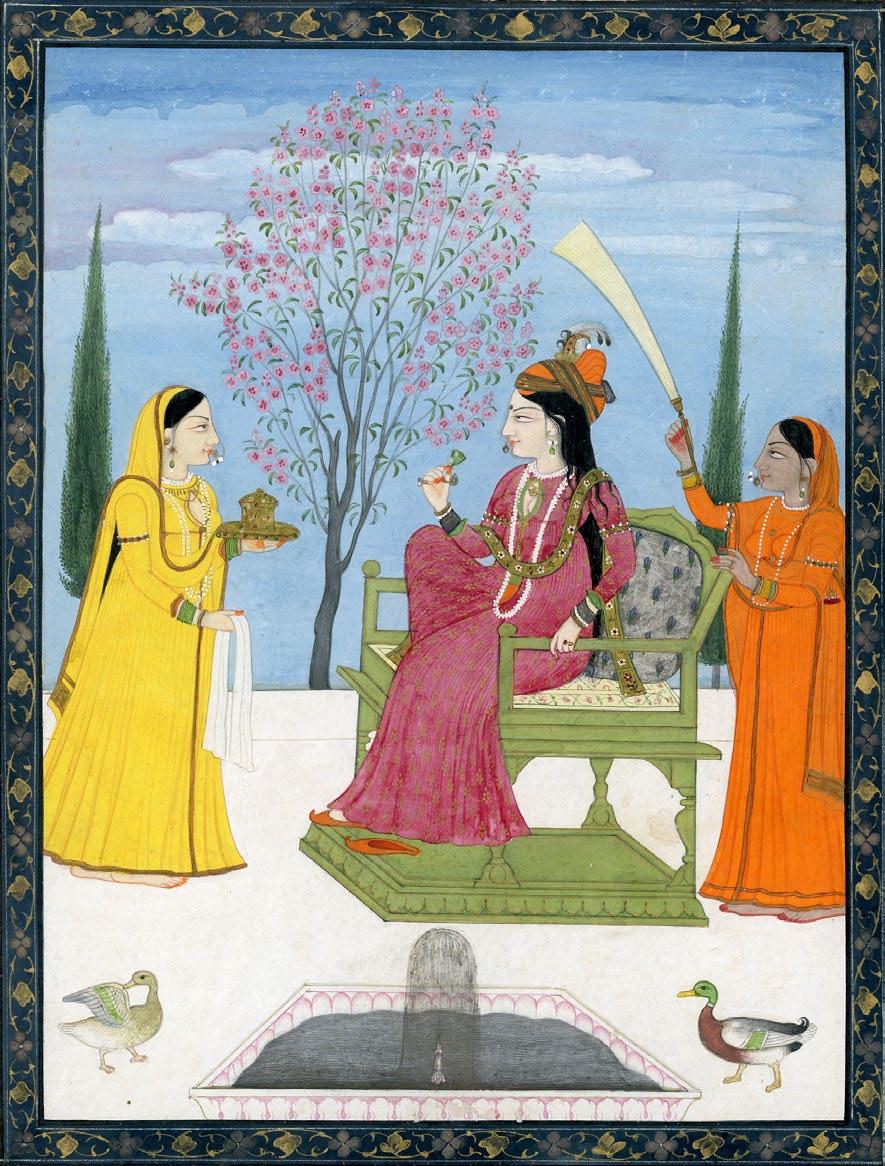

1 Cover

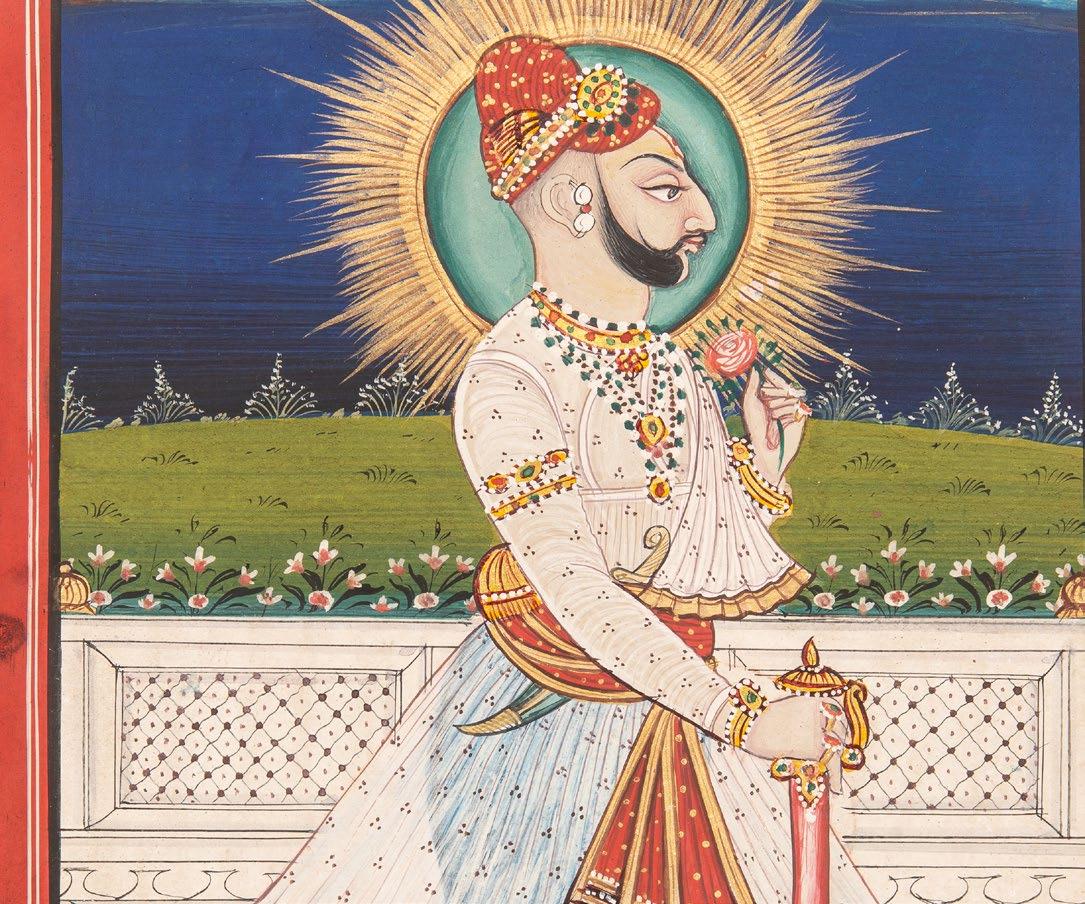

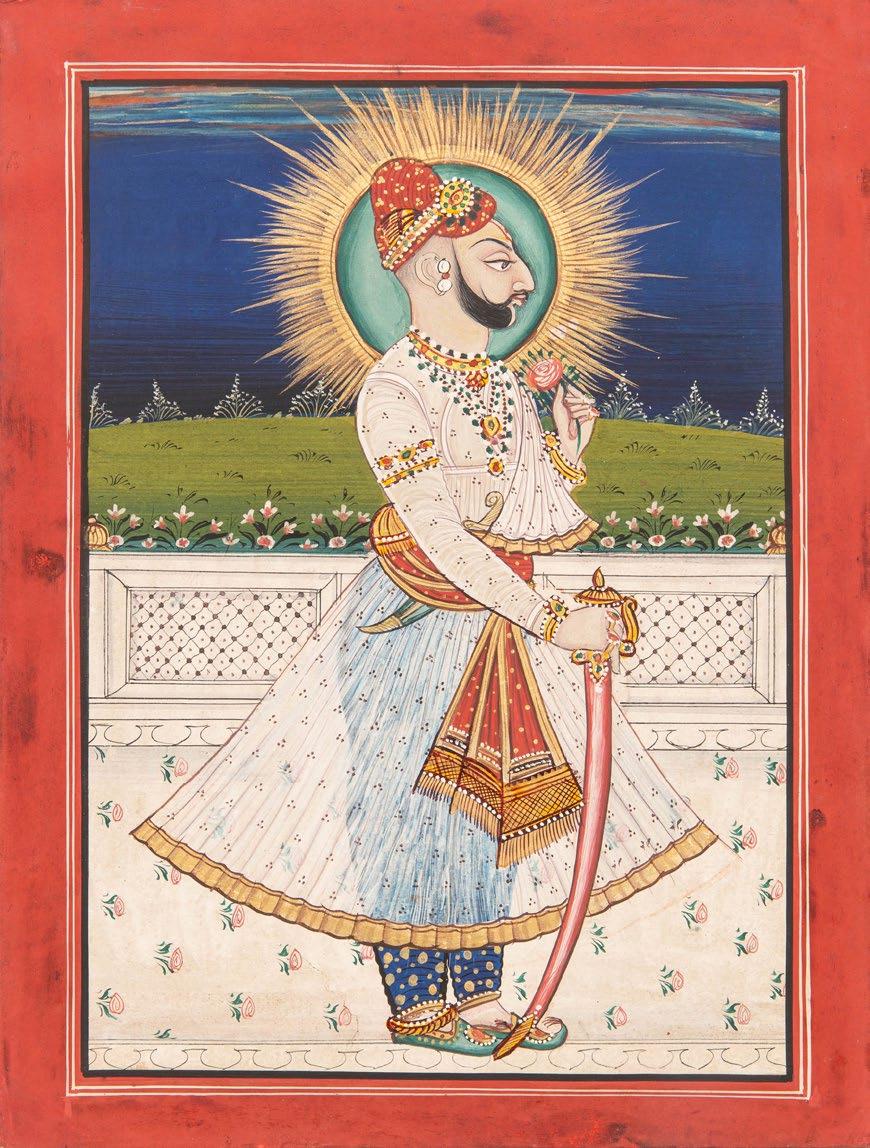

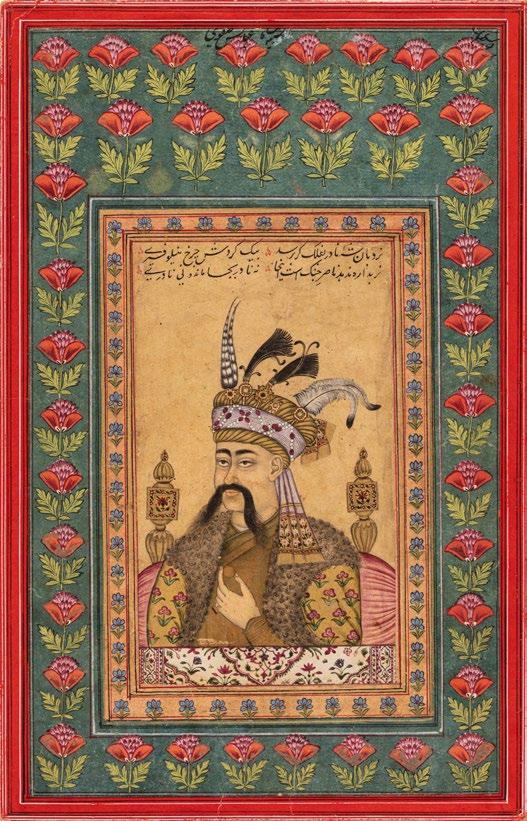

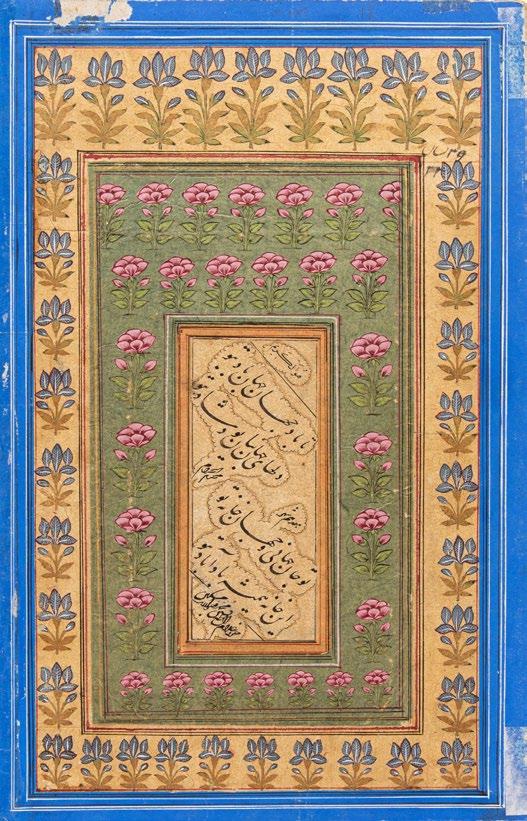

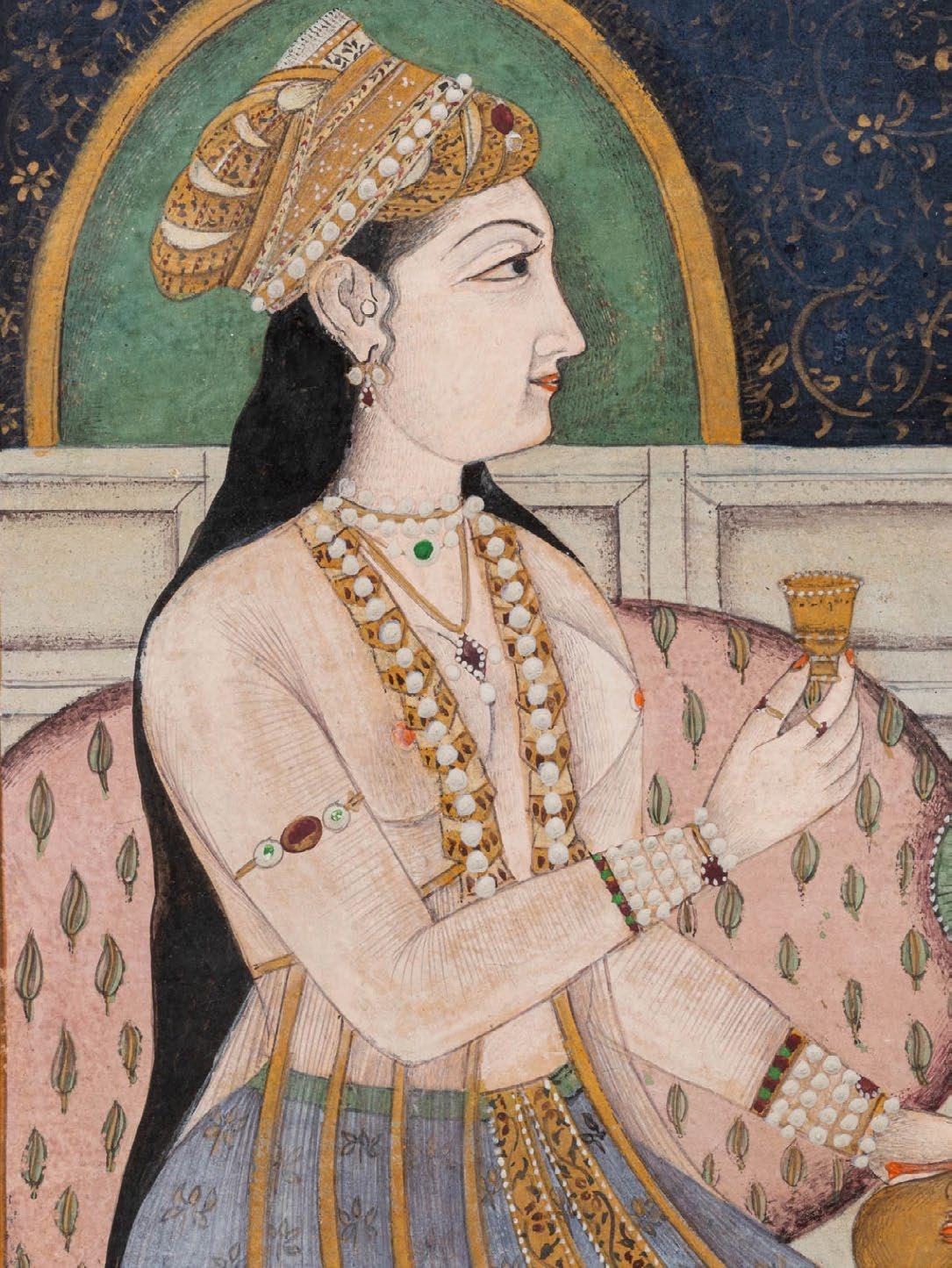

Bundi, Rajasthan, India, 19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 10 1/4 x 7 1/4 in. (26 x 18.5 cm.)

Folio: 12 x 9 in. (30.5 x 23 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

The motif of the ruler holding a blossom and a sword may be understood as emblematic of sensitive and martial qualities representing a king who can appreciate the delicate and ephemeral fragrance of a flower, but will fearlessly face his enemies when provoked.

Kapoor Galleries presents The Blossom and the Sword, a fall 2025 exhibition showcasing portraits from across the Indian subcontinent. These works depict individuals from all walks of life including noblemen and women, high-court officials, courtesans, and villagers. The paintings of nobility reveal how the courts of India aimed to convey a sense of refined elegance and an authoritative presence to their subjects, while the depictions of others offer glimpses into everyday life and society. Every element — from the details of the garments and colors used, to the posture, gaze, and objects in hand — offers insight into the individual, their social status, the culture of the time period, and the society in which they lived. Explore the portraits of India in The Blossom and the Sword, opening Thursday, September 18, 2025, at Kapoor Galleries.

TSeptember 18—October 23, 2025

Opening Reception: September 18, 6-8PM

Kapoor Galleries

34 E 67 ST, FL 3

New York, NY

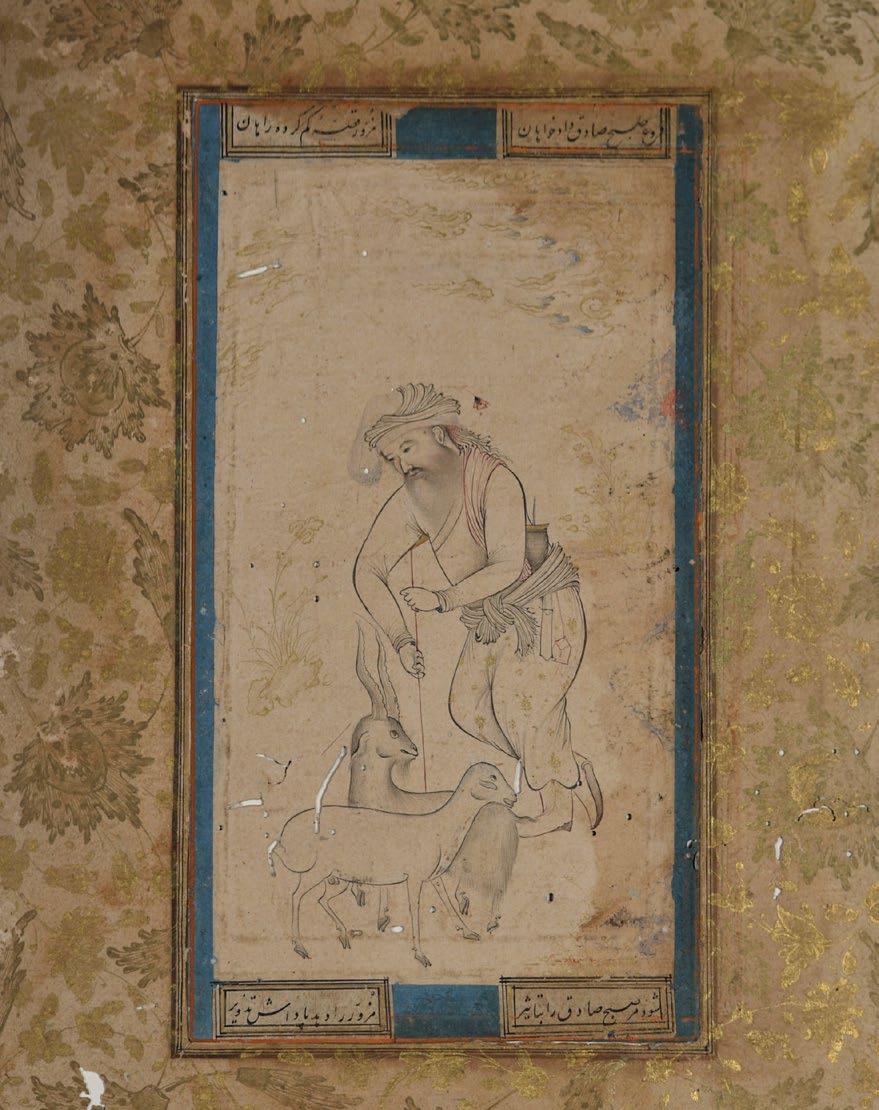

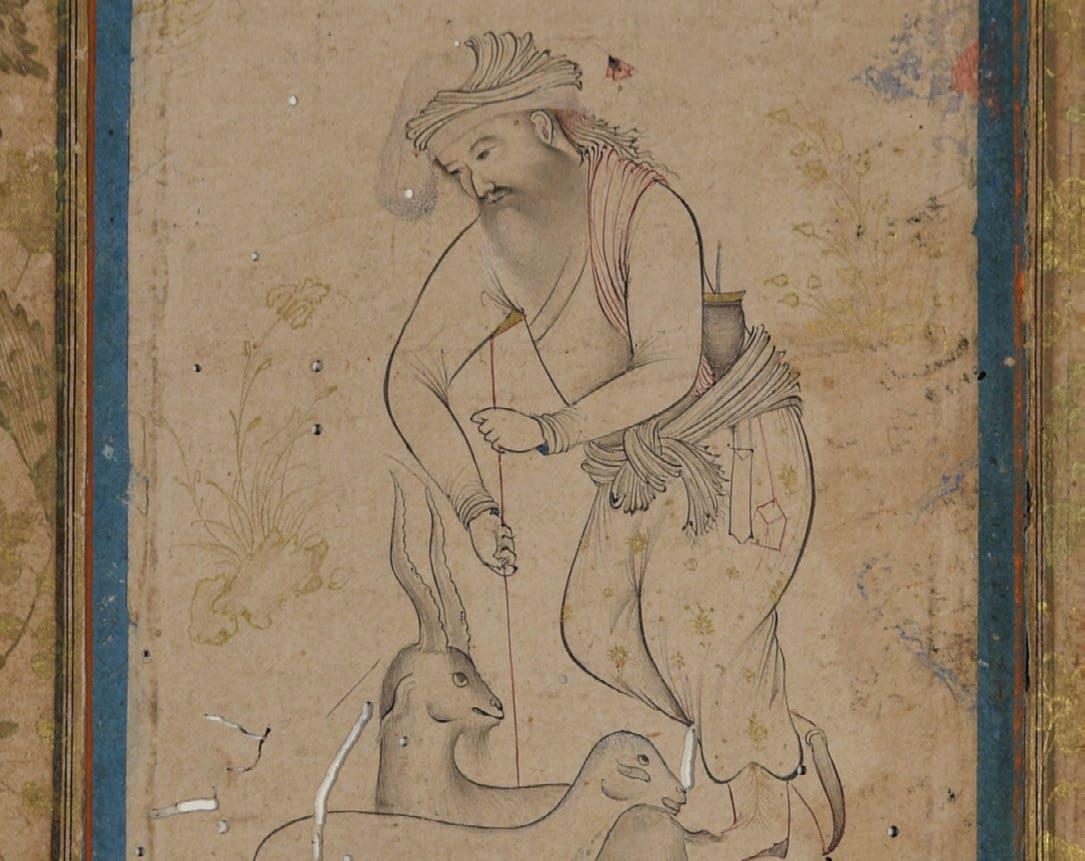

A Dervish with Two Goats Persian, Isfahan, Safavid era, mid-17th century (after 1620)

Pen and ink drawing with gold on paper

Image: 8 1/4 x 4 1/2 in. (21 x 11.4 cm.)

Folio: 12 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (31.8 x 21.6 cm.)

Provenance:

Saeed Motamed Collection.

Christie’s London, October 7, 2013, lot 118.

An old bearded goat herder, or dervish, leans on the crook of his walking stick as he looks wistfully beyond his two goats below. Hints of foliage suggesting landscape and stylized clouds in a gold wash swirl in the Background.

This fine pen drawing is attributable to Riza-yi ‘Abbasi (ca. 1565-1635), a highly influential and exalted artist in the atelier of Shah ‘Abbas I of Isfahan (r. 15881629) or his circle. Also called ‘Aqa Riza’, he received his early training from his father, the painter Maulana Ali Asghar, and joined the royal atelier at a young age. Abbasi abruptly left the Shah’s service around 1605, giving up his courtly existence for a life among the lower classes of Isfahan. Around 1610, however, he returned to the Shah’s atelier where he remained until the end of his life.

The present drawing demonstrates how Aqa Riza mastered calligraphic pen lines modulating from thick to thin, with minimal or no color (particularly in his later years), containing an aesthetic quality as expressive as it is economical in form and color. A drawing of an old man with a cane bearing an inscribed attribution to Riza-yi ‘Abbasi in the collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard (acc. 2002.50.16) shares these qualities. For another example from this later period see the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s The Old Man and the Youth (acc. 25.68.5) and the British Museum’s Hunters at a Stream (acc. 35.1027).

3

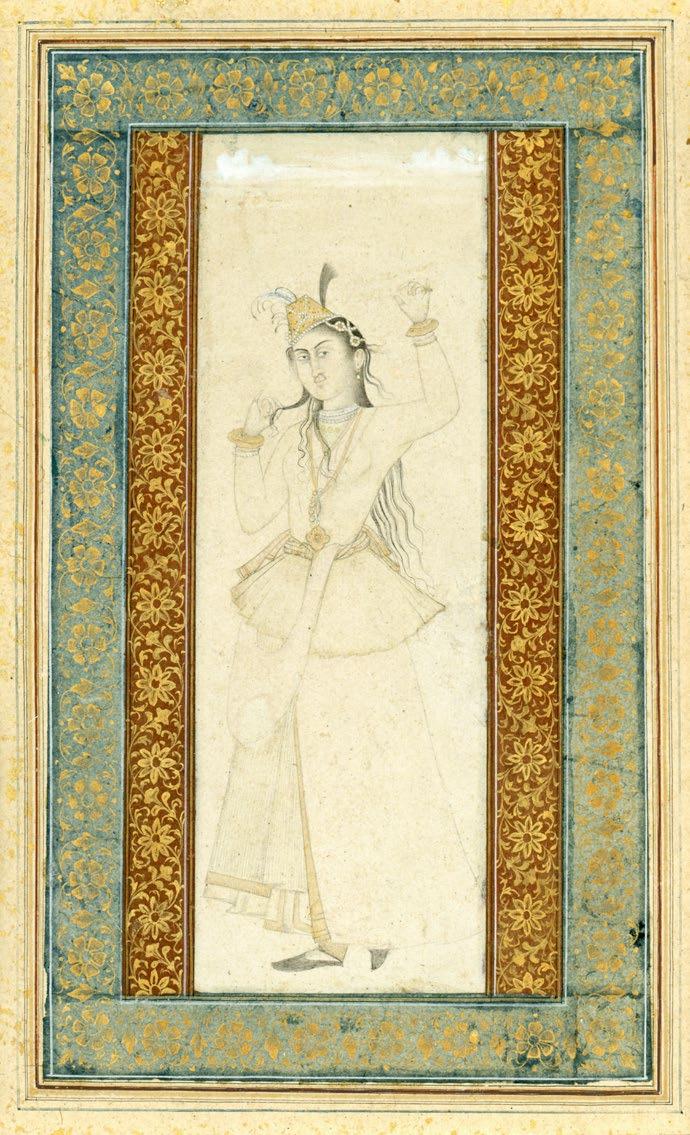

A Courtesan Dancer Deccan, Golconda or Hyderabad, India, last quarter of the 17th century

Ink with embellishments in gold on paper

Image: 7 3/4 x 2 5/8 in. (19.7 x 6.7 cm.)

Folio: 13 7/8 x 10 in. (35.2 x 25.4 cm.)

Provenance: Saeed Motamed Collection.

Christie’s London, 7 October 2013, lot 118.

The young dancer’s long wavy black hair falls in slender tresses down her back and over her shoulder. She is dressed in a Safavid Persianate manner and faces the viewer in three-quarter pose. She places her weight on one leg and twists rhythmically, her left hand raised up above her head and her right playfully pinching out a strand of hair. A feathered and gold cap with strands of pearls, gold bracelets and necklaces adorn her figure from head to foot.

Her near-frontal pose suggests that she is a courtesan—a princess, meanwhile, would typically be depicted in profile. Although the identity of this courtesan is unknown, she is depicted with realistic features, capturing a true representation of the sitter in a Mughal style. By this time, the Mughals conquered the Deccani Sultinate finalizing their triumph over the region. This portrait was executed when Mughal aesthetics dominated the Deccan, evident here in the realism and empty background with a carefully patterned outer border.

The present portrait is similar to a published painting of a Yogini with a Mynah Bird (Chester Beatty Museum, Dublin, Ireland, accession no. In 11A.31), depicted half length with a bold smile and full face. Both women project a similarly insouciant attitude. And for another painting of a similar style and subject, reference A Dancing Courtesan – Folio from the Colebrook Album, North India, possibly Delhi region, from the early 19th century, executed in opaque pigments heightened with gold on paper and laid down on an album page (folio: 33.1 x 24.4 cm.; painting: 21.5 x 14.4 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

This 18th-century painting from the North Deccan, India, captures the grandeur of a nobleman’s procession. The composition is steeped in both regal authority and artistic refinement to convey the visual language of power and prestige.

At the heart of the composition, a Maratha nobleman, likely a high-ranking courtier or military leader, is depicted riding a richly adorned horse. His ornate attire and pagadi (turban) on his head are embellished with gold detailing and reflect his elevated status.

The Maratha Empire (1647-1818), known for their military prowess and administrative acumen, cultivated a distinct visual culture that merged Persian courtly aesthetics with indigenous Deccan artistic traditions. The artist meticulously renders the hierarchical arrangement of the nobleman’s entourage, including spear-bearers and soldiers, reinforcing the structured and disciplined nature of Maratha governance. The soldiers’ synchronized movements and elaborate green-and-gold attire evoke a sense of military unity. Few attendants

follow behind his horse and hold ceremonial regalia like a chowerie (fly-whisk) to signal his sovereignty and protection under divine authority.

A striking feature of the painting is the lush lotus-filled lake in the background, punctuated by elegant waterfowl. This idyllic setting provides a symbolic contrast to the military grandeur in the foreground, alluding to the nobleman’s role as both a protector and a patron of prosperity. The lotus, an enduring symbol of purity and divinity, may also indicate the nobleman’s righteousness and legitimacy.

The naturalistic and refined palette heightened with gold and the meticulous attention to textile and flora-fauna detailing in the landscape reveals the hand of a skilled court painter. This portrait remains a testament to the artistic sophistication and imperial ambitions of the Maratha Confederacy.

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 1/2 x 6 in. (24 x 15.3 cm.)

Folio: 14 1/2 x 10 in. (37 x 25.5 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

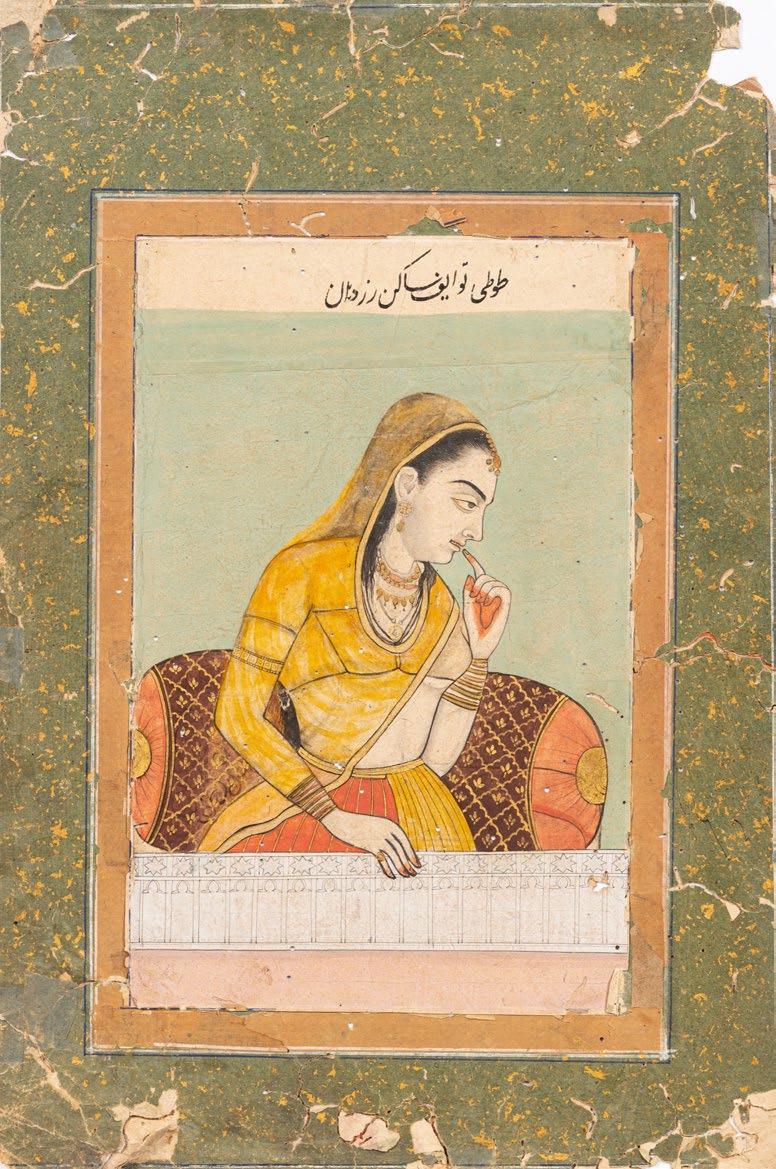

In this present image, a female courtesan is depicted in profile, looking out from her outdoor balcony. She is dressed in a cropped choli which leaves her lower breast exposed–her sheer golden dupatta doing little to cover her. She seductively lifts one finger to touch her parted lips, while the fingertips of her other hand graze the balcony walls. The inscription on the recto identifies her as Tuti Tawaife from Zardan, a small Iranian village near Afghanistan.

Much like the Japanese geisha, a tawaif was considered an authority on etiquette and was the epitome of high society in Mughal India. These high-class courtesans were well versed in literature, and often schooled from a young age in dance and music as well. Tawaif’s also retained a higher degree of freedom than many other Indian women, allowing them an education and the right to their own property. Their beauty and refined grace made them muses for Maharaja’s and artist’s alike, making them a popular subject for portraiture during this period.

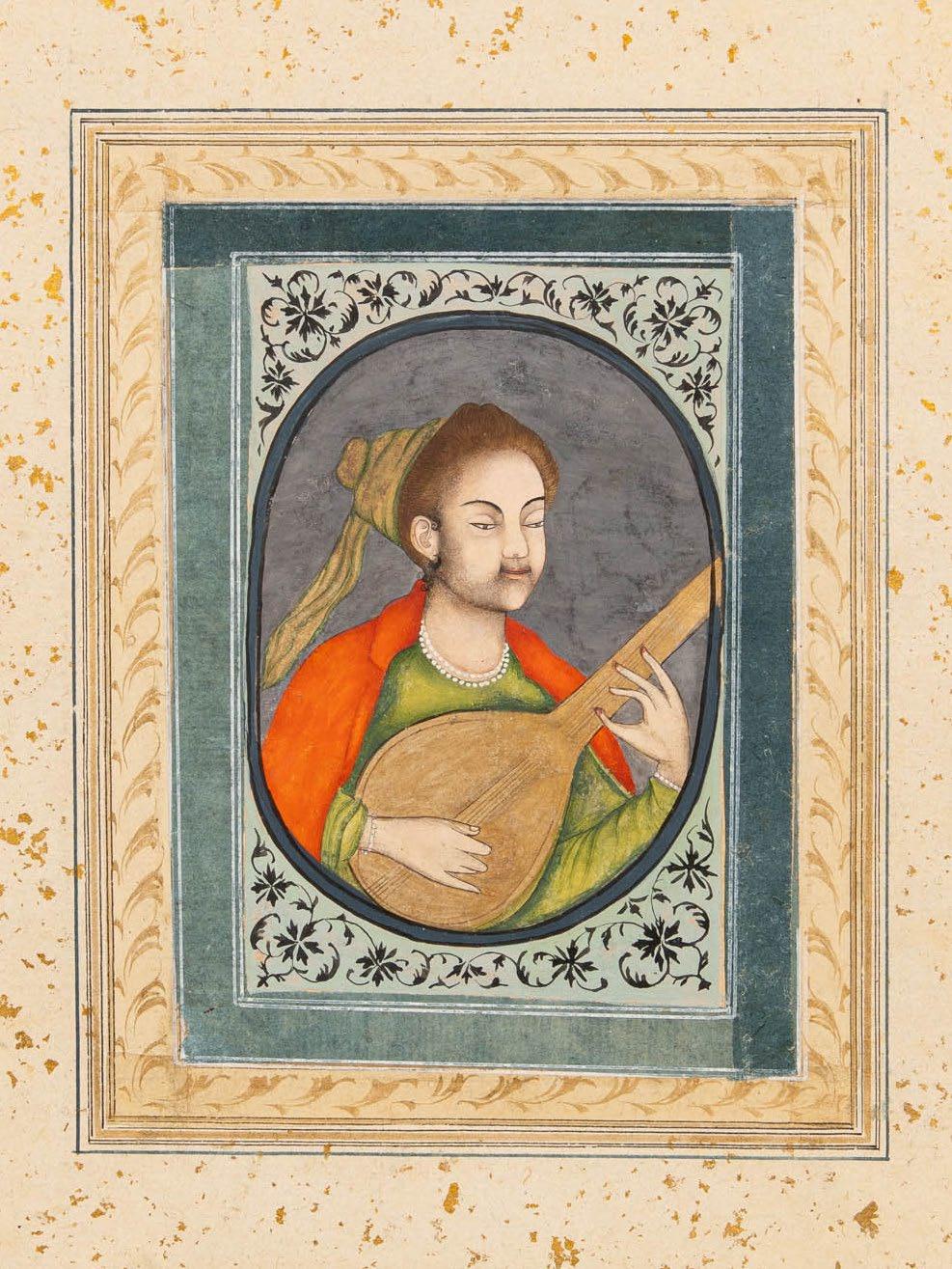

Naderzaman

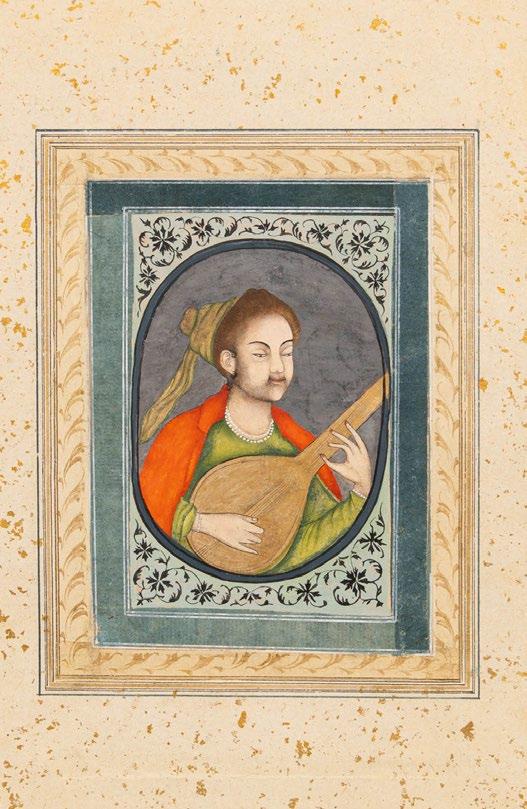

Female Musician Playing the Lute Pahari Hills, India, 18th century

Gouache and gold on paper

7 3/4 x 6 in.(19.7 x 15.3 cm.)

Signed by artist on verso in fine Persian calligraphy

Exhibited:

Olsen Traveling Exhibition, Olsen Foundation, Bridgeport, CT. North Carolina Museum of Art.

Provenance:

Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York. Olsen Foundation.

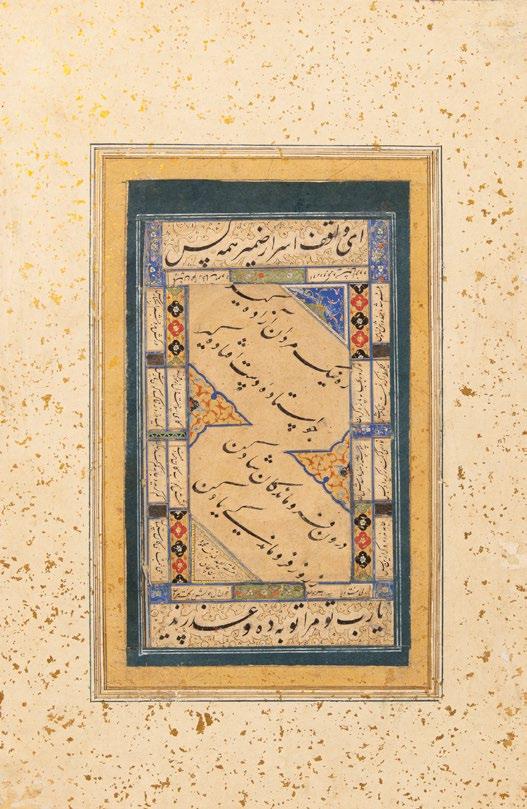

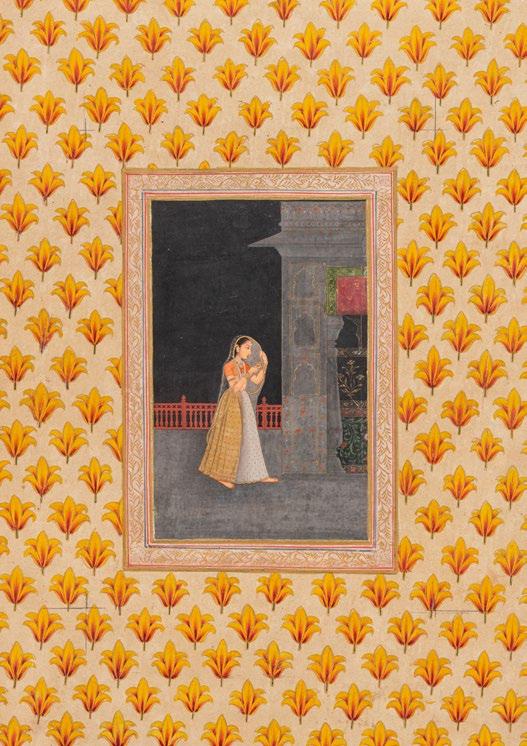

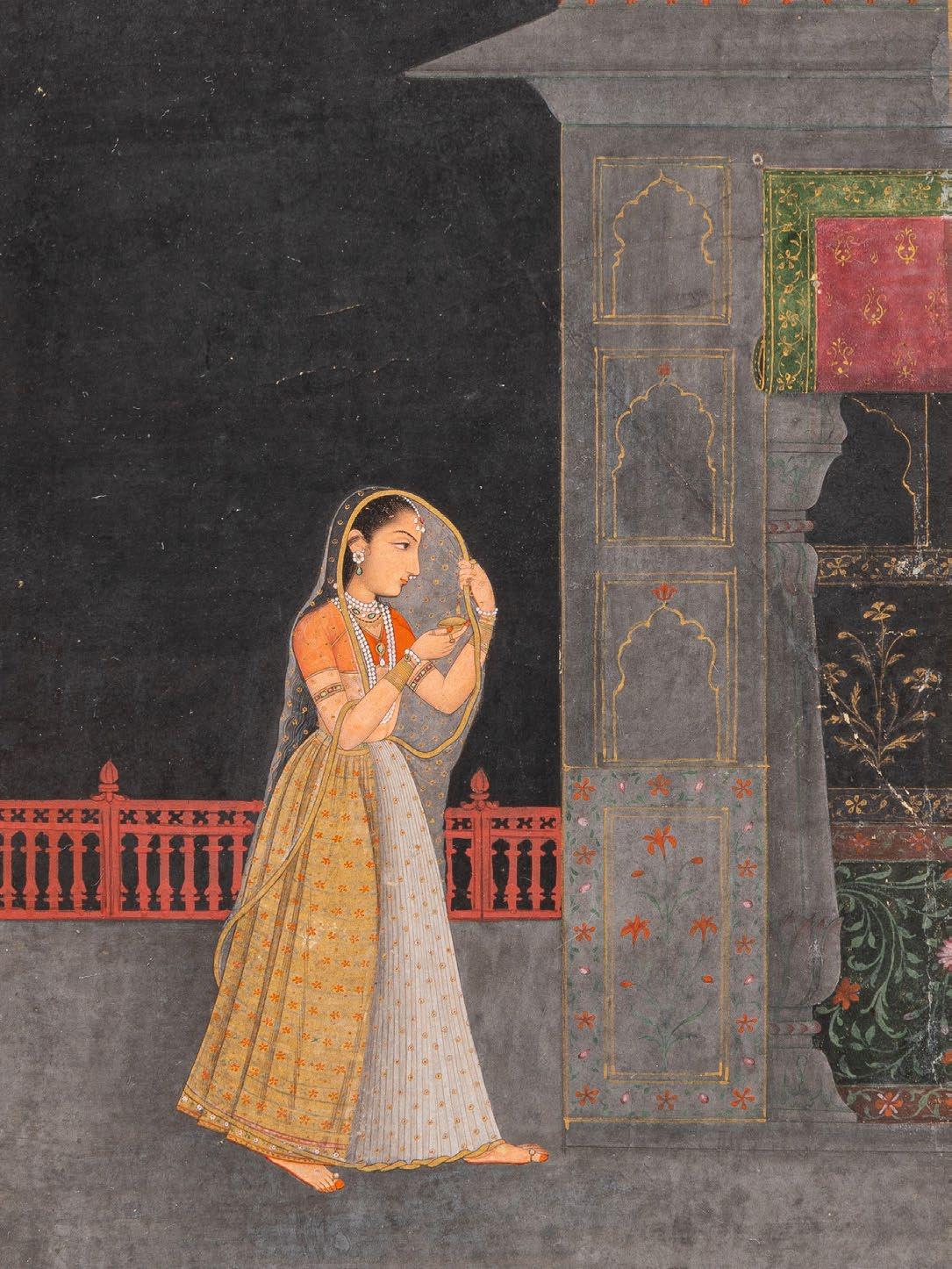

Princess Strolling Across a Palace Terrace at Night Lucknow, Awadh, India, circa 18th century

Gouache painting on paper heightened with gold leaf

Image: 7 1/8 x 4 7/8 in. (18.1 x 12.4 cm.)

Folio: 17 x 12 in. (43.2 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Doris Wiener Gallery, New York, September 30, 1969 (documentation available upon request).

This exquisite miniature painting from 18th-century Lucknow embodies the refinement and poetic sensibility of late-Mughal and Awadhi courtly aesthetics. The composition depicts a princess walking barefoot across a palace terrace late at night in an intimate moment, engaged in an act of quiet contemplation with a subtle sense of resolve. The artist employs a darkened background to evoke the enveloping night sky, enhancing the luminosity of the central figure whose delicate features, dress, and jewelry gleam in contrast. Awadhi miniatures often incorporate a diverse range of painting techniques, with specific interest in the interplay of light and shadow, as well as a more precise rendering of volume and spatial depth.

The princess is dressed in an elegantly pleated and embroidered golden skirt with a deep orange blouse. She gently draws her sheer dupatta (shawl) forward with one hand to partially veil her face, and perhaps wishing to remain hidden in the night. The fabric of her dress is rendered with an exquisite attention to textile detailing, showcasing the artist’s ability to convey the rich and graceful

qualities of the princess. Soft shading across her form brings a sense of volume and dimensionality to the central figure. She is also adorned with a string of pearls draped around her neck, wrists, forehead, and toes with various jewels embellished throughout, emphasizing her regal presence. Looking more closely, alta (red dye) decorates the tips of her fingers, toes, and the soles of her feet, denoting her status as a married woman. She also holds up a small diya (candle) to her face. Her ethereal presence in this scene is further accentuated by her serene expression and the soft upward curve of her lips.

A series of finely painted jharokhas (arched windows) frame the princess in the evening scene, and floral motifs decorate the structure on the right. A crimson red balustrade in the background anchors the composition spatially and adds a rhythmic contrast to the princess’s gentle stride. The restrained yet vibrant color palette, with the interplay of warm ochres, muted blues, verdant greens, and bold reds, reflects the refined sensibilities of the period. Such nocturnal vignettes, often laden with poetic and literary associations, were favored subjects in courtly ateliers, illustrating themes of solitude, anticipation, and the fleeting nature of beauty.

The miniature painting is encased by a large vibrant yellow and red floral border, its repeating pattern heightened with gold leaf. The verso of the painting includes a panel of Arabic-Persian calligraphy in Nastaliq script with a floral emblem at the top. The panel is surrounded by a dark green border speckled with gold leaf throughout. The lines of script are addressed to God (or the beloved, a royal figure, the benevolent, the calif, etc.) and reads as follows:

Oh, thou who has solved world’s problems with your benevolence; solve people’s problems with your benevolence.

No other but thou is the granter of prayers; all prayers are granted because of thou.

It’s only your benevolence that is heartwarming; grant us your benevolence to warm our hearts.

(Translation provided by Yass Alizadeh, PhD, Clinical Associate Professor, Persian Program Coordinator, Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, New York University.)

Refer to a painting for a comparable recto and verso of this piece at the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington (IS.14-1949). This painting is from a similar period and includes a floral border and calligraphy panel as well. See another comparable painting in The British Museum (1974,0617,0.21.77).

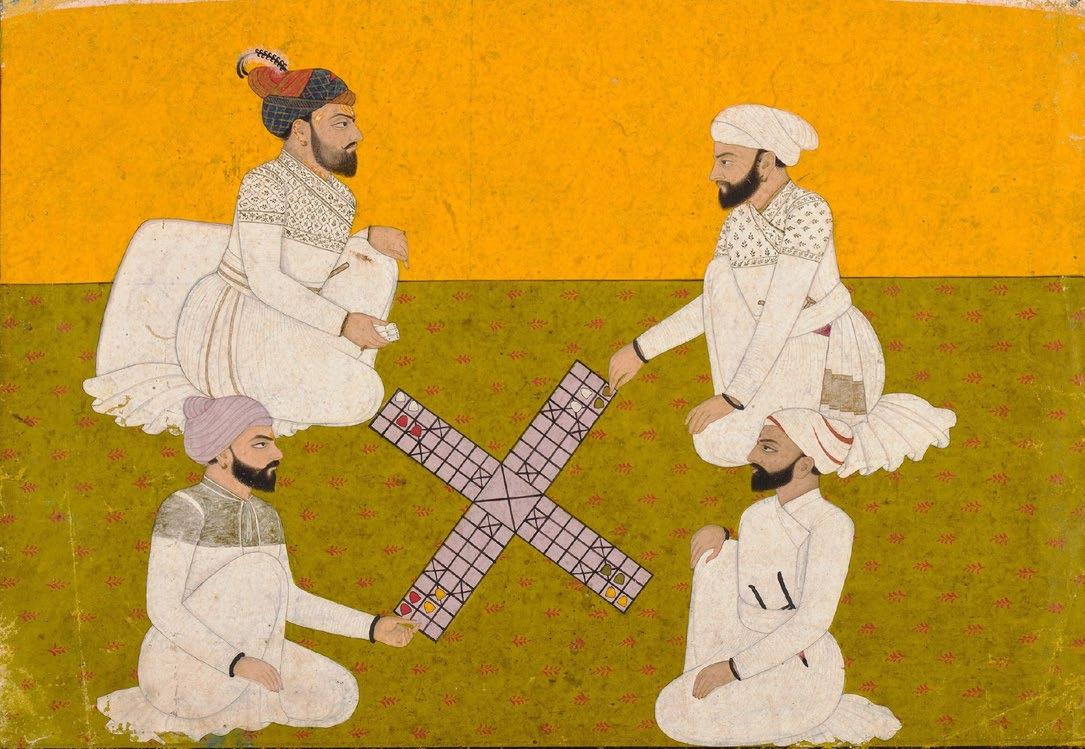

A Raja and His Courtiers Playing Chaupar Attributed to the Master at the Court of Mankot, possibly Meju (active 1690-1730)

Guler or Basohli, India, 1720-1750

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 1/4 x 6 1/2 in. (23.5 x 16.5 cm.)

Folio: 10 1/2 x 7 3/4 in. (26.7 x 19.7 cm.)

Provenance:

Collection of R. Hale, California, acquired by the family in the 1960s.

A raja leans forward into a game of chaupar with three courtiers. The player opposite him cautiously moves his small piece on the board while the raja holds long dice in his right hand, preparing to make his throw. An intensity pervades the scene which unfolds against a brilliant yellow background further heightening a palpable sense of competition. There seems to be more at stake here psychologically than the game alone as the raja and his teammate (just below him in the composition) display somewhat aggressive body-language; leaning forward and staring at their opponents. The two competitors are likely visiting vassals from a nearby fiefdom, and present a more respectful posture, perhaps as a reflection of courtly hierarchy. All the chaupar participants are dressed in white muslin jamas or coats, with no elaborate ornamentation aside from the katars or punch-daggers tucked into their waistbands. The principal raja, however, wears jama with elaborate embroidery and a colorful, feather-topped turban.

The fine quality of this painting is apparent in the minute level of detail within each pattern, adornment, and facial feature. The figures appear as if they are frozen mid-motion, despite the near-invisibility of the artist’s stroke. Such qualities are reminiscent of the Guler masters Pandit Seu, his son Nainsukh, and the generation that followed. The composition, moreover, is reminiscent of a painting of Mian Gopal Singh playing chess with Pandit Dinamani Raina attributed by Goswamy and Fischer to Pandit Seu in Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India, Zurich, 1992, p. 228-229, cat. no. 92.

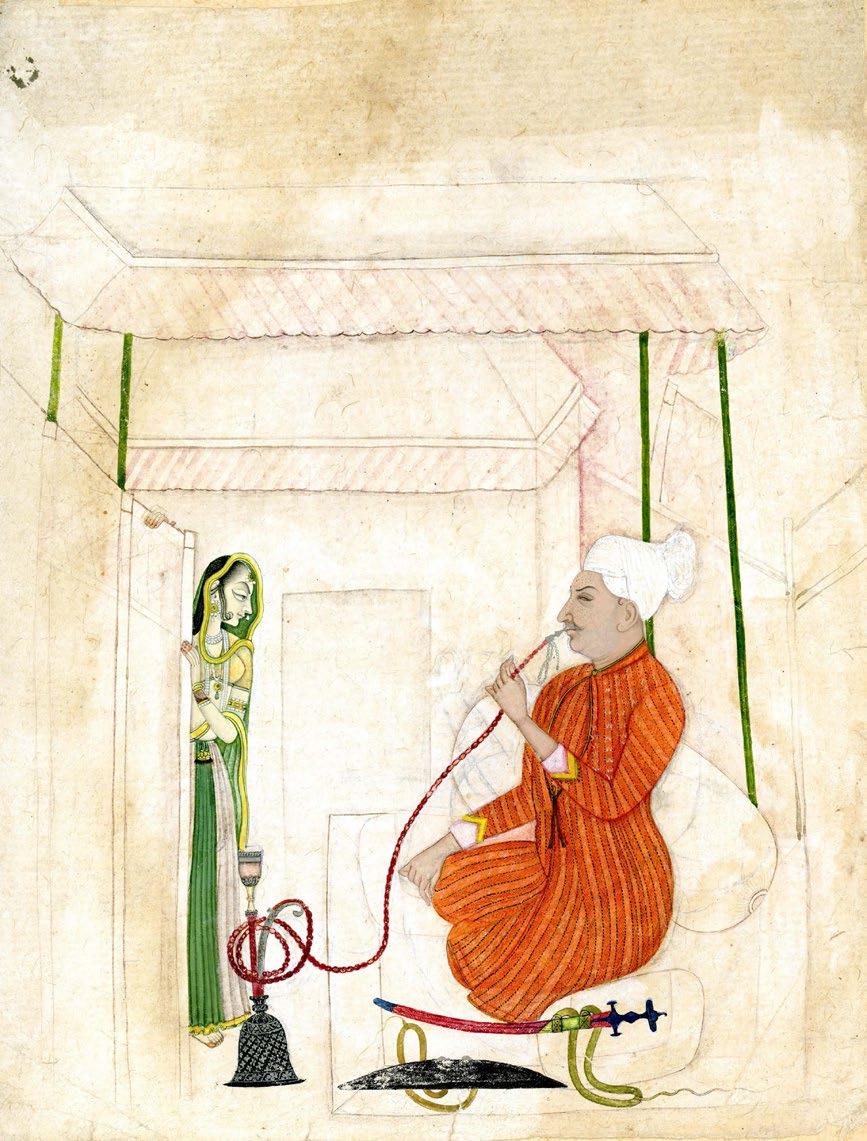

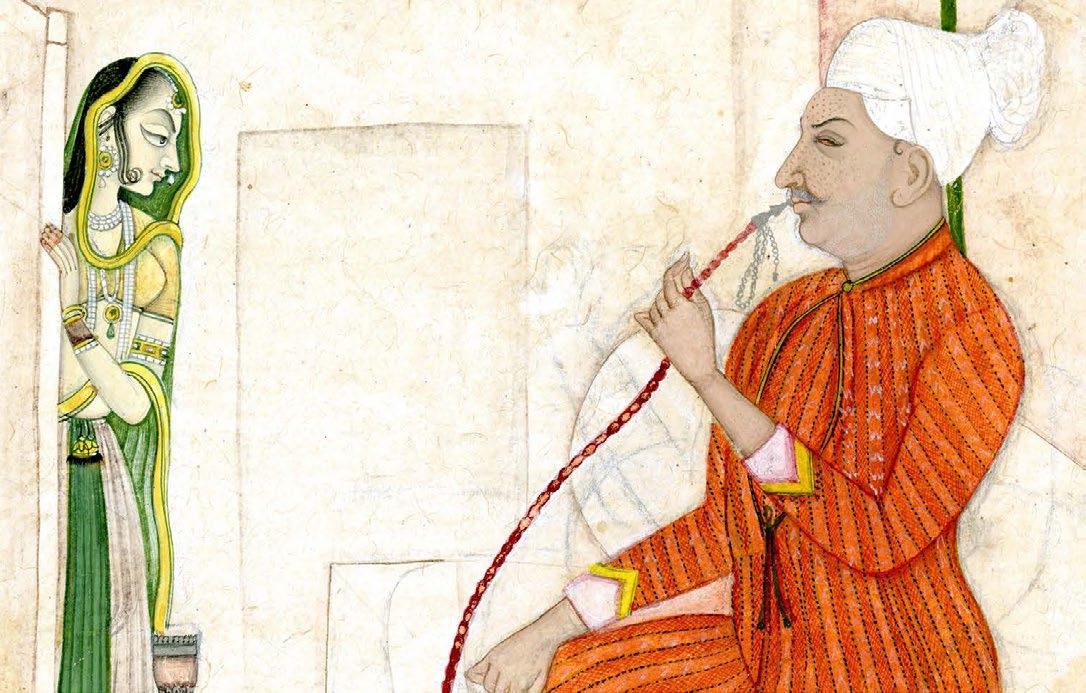

A Maiden Approaches a Nobleman Kishangarh, India, circa 1740

Ink drawing with opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

10 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (26.7 x 21 cm.)

Provenance:

Doris Wiener Gallery, New York, inventory no. 43439.

Dorothy and Alfred Siesel, Washington, D.C., acquired from the above 14 December 1976.

A naturalistically depicted elder noble man seated against a bolster puffs from the metal tip of a winding hookah stem, his eyes half shut with a sheathed sword and shield laid out before him. A beautiful young maiden looks intently out from behind a screen, coyly hiding part of her body as if trying to be careful not to be seen. Her angular face with its pointed nose and chin, pursed mouth, almondshaped eye and high brow, and black hair tied back with three curls placed over her cheek are reminiscent of Bani Thani—a poetess and courtesan, considered the epitome of idealized Kishangarh beauty.

The scene could be the old man’s intoxicated dream; a glimpse into the memory of a past love, now elevated to perfection in the noble’s thoughts. Conversely, the maiden could be taking the position of the archetypal seductress, a universal subject serving as a trope of the older man’s desire for a youthful woman.

This is an enigmatic scene often found in paintings from Kishangarh and particularly from the period of the artist Nihal Chand (ca. 1710-1782), whose training in the Imperial Mughal workshops at Delhi helped him create a popular new style that combined Mughal naturalism with the romantic, poetic idealization beloved at Kishangarh. The signature Kishangarh style began to develop under Raj Singh (r. 1706-1748), and reached full fledged actualization under Sawant Singh (r. 1748-1764). As the present painting dates to the mid-1700s, we know it was executed under one of these rulers’ reigns. As such, it is a delightful example of the evolution of Kishangarh painting during the century. This idyllic, amatory manner so-valued within the realm is well suited for the depiction of bhakti, the ecstatic longing for the divine often anthropomorphized as Radha’s love for Krishna.

Portrait of Shitab Rai, Naib Diwan of Bihar Murshidabad, India, late Mughal, 1770-1780

Opaque pigments with gold on paper

Image: 3 3/4 x 2 5/8 in. (9.5 x 6.7 cm.)

Folio: 9 x 5 3⁄8 in. (22.8 x 13.7 cm.)

Inscribed on the verso: Mahraja Setavroy Subah of Bahar

Provenance:

Françoise and Claude Bourelier Collection, Paris. Artcurial, Paris, November 4, 2014, no. 237.

This finely executed portrait presents Shitab Rai, the Naib Diwan (a deputy collecting revenue for the East India Company) of Bihar under the Mughal administration, seated in an intimate, enclosed space, holding the mouthpiece of a hookah. During this period, oval portraiture in the Mughal provincial style was becoming increasingly popular, likely influenced by European portrait miniatures. Despite the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765, which transferred revenue collection rights to the East India Company, the Mughal regime continued to oversee various administrative matters, particularly in Patna. Shitab Rai played a crucial role as an intermediary in negotiating the treaty between the Company, led by Robert Clive, and Mughal Emperor Shah ‘Alam II along with the Nawab of Awadh, Shuja’ alDaula. He is also remembered for organizing relief efforts during the devastating famine of 1770, publicly shaming the East India Company into taking similar action. However, he was later arrested and dismissed from his position, passing away shortly thereafter in 1773. (continued)

This oval portrait is set on a simple album page and is framed in white with rufflettes. It depicts Shitab Rai dressed in a white turban adorned with a jeweled ornament (sarpech) and a wide gold fabric belt over the center waist. The soft-pink color of his jama attire adds a touch of elegance. He reclines against decorative cushions embroidered with gold while holding one underneath his hand. The composition is distinctive as its compact setting creates a sense of closeness, almost confinement, between the viewer and figure. A simple enclosed room in the background is lined with frilled decorations that line the meeting point of the ceiling and walls. Shitab Rai’s expression remains neutral with a bold and unwavering look in his eyes as he possibly engages with an unseen guest to whom he graciously extends the hookah mouthpiece. His face and form are rendered with fine detailing that lend to the depth of his features—wrinkles and pronounced shading around his eyes, mouth and hands.

Compare this portrait of Shitab Rai to a similar portrait of him in Murshidabad ‘Company’ style album in the British Library (Archer 1972, no. 39xxvii, unillustrated).

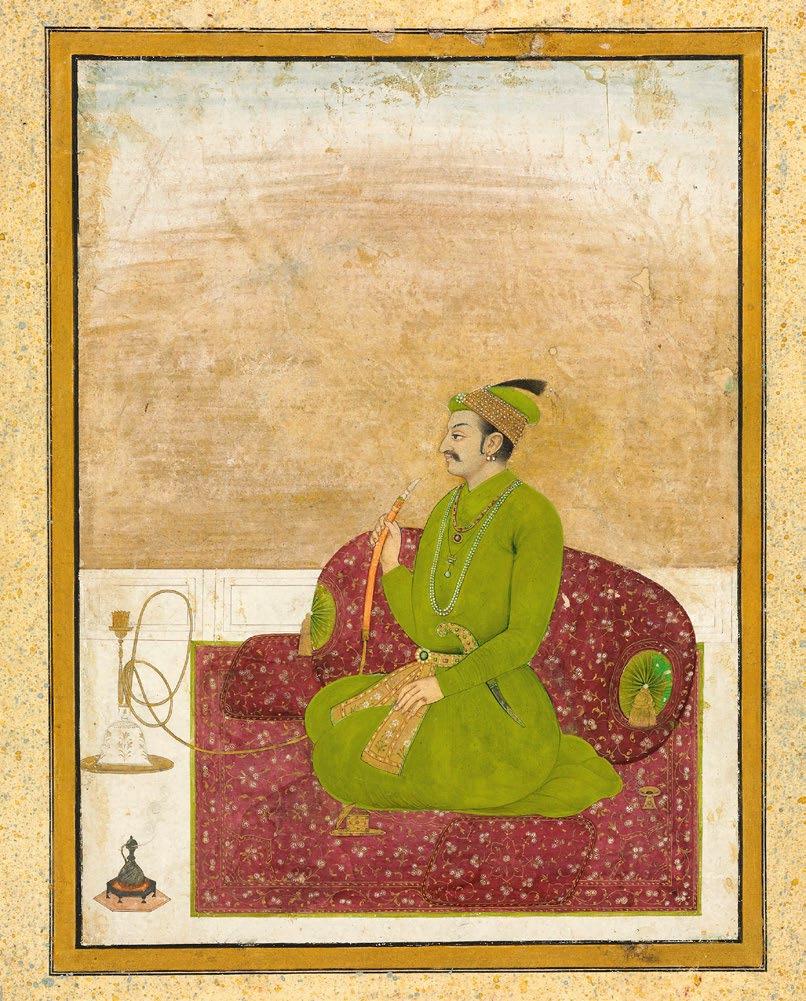

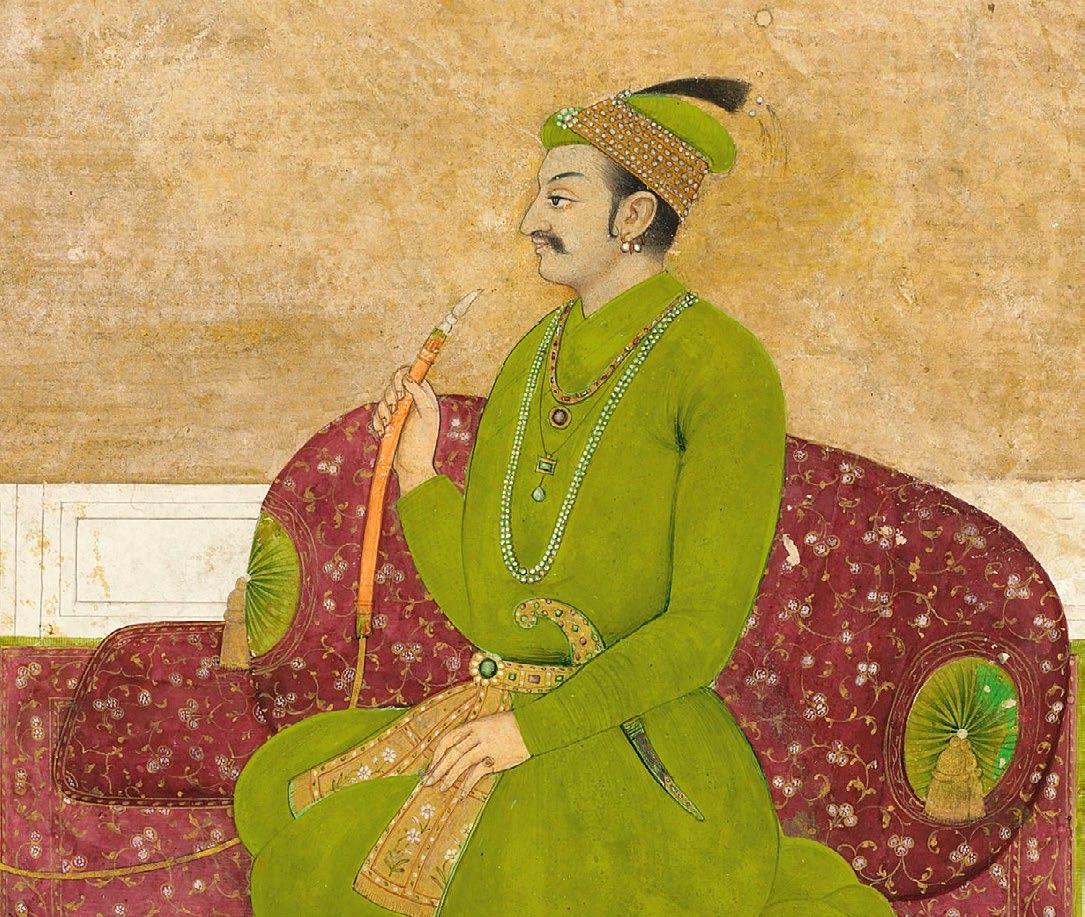

Seated Nobleman on a Terrace

Attributed to Pandit Seu and his Family Workshop Guler, India, circa 1750

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 1/8 x 5 3/8 in. (18.2 x 13.6 cm.)

Folio: 11 1/2 x 7 7/8 in. (29.1 x 20.1 cm.)

Exhibited:

Air India’s Maharaja: Advertising Gone Rogue, Poster House Museum, September 9, 2022 - February 12, 2024.

Provenance:

The collection of Carol Summers. Christie’s New York, 20 March 2019, lot 713.

A nobleman in a vivid green jama with an elaborate floral and jeweled belt, necklaces of rubies, emeralds and pearls that match his embellished turban surmounted by a feathered sarpech, appears dignified atop a white marble terrace. He relaxes before an elaborate drawstring bolster atop lavish textiles as he holds the end of a hookah, before which a heated vessel sits emitting wisps of smoke. The elegant composition is worthy of close comparison to a figure in the same posture, garb and environment as the present nobleman, attributed to the master painter Nainsukh: a drawing of Mir Mannu in the Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh (acc. no. B-60), illustrated by B.N. Goswamy in Nainsukh of Guler, Zurich, 1997, pp. 102-103, no. 27.

Since Akbar’s time, the Mughal Empire exerted suzerainty over the small principalities within the rich landscape of the Punjab Hills. The present painting is a result of that influence, as it was very likely painted from an imperial Mughal model. The painting is, nevertheless, of the highest quality and thus attributed to the famed atelier of Pandit Seu of Guler—an artist who credited with aiding in the shift to a more formal style with the transmission of Mughal techniques learned directly from disbanded artists from Aurungzeb’s former atelier.

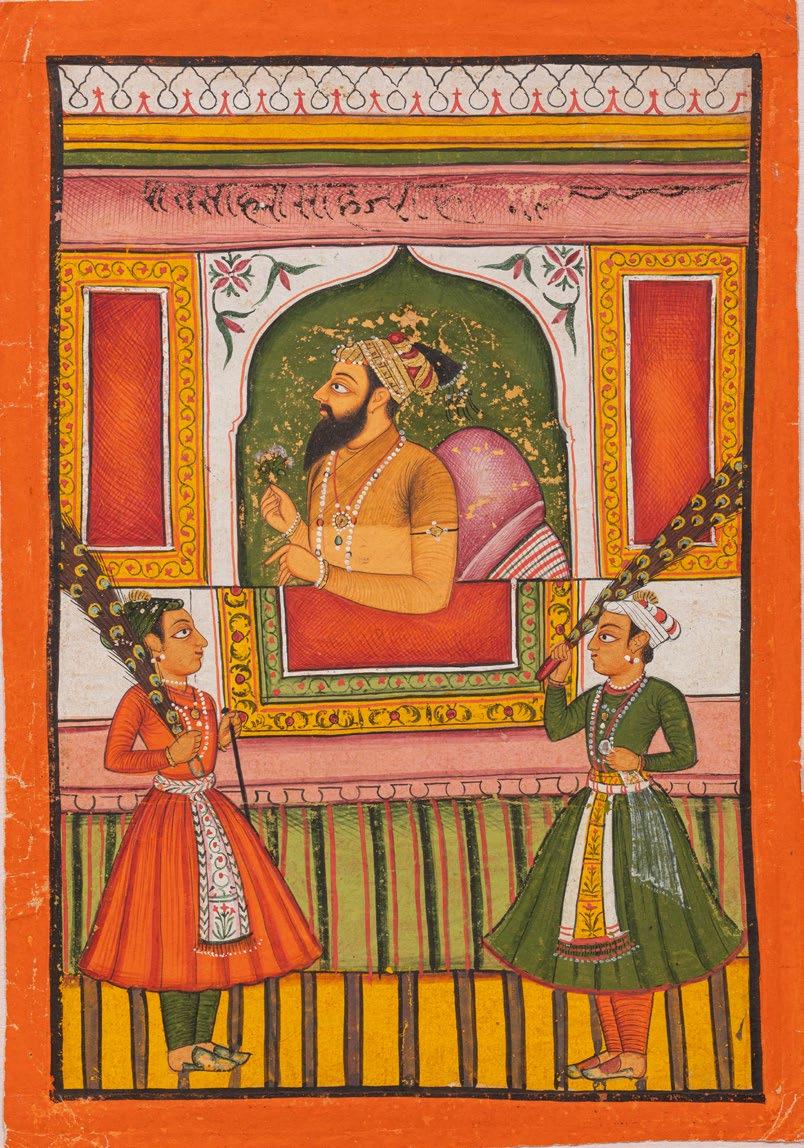

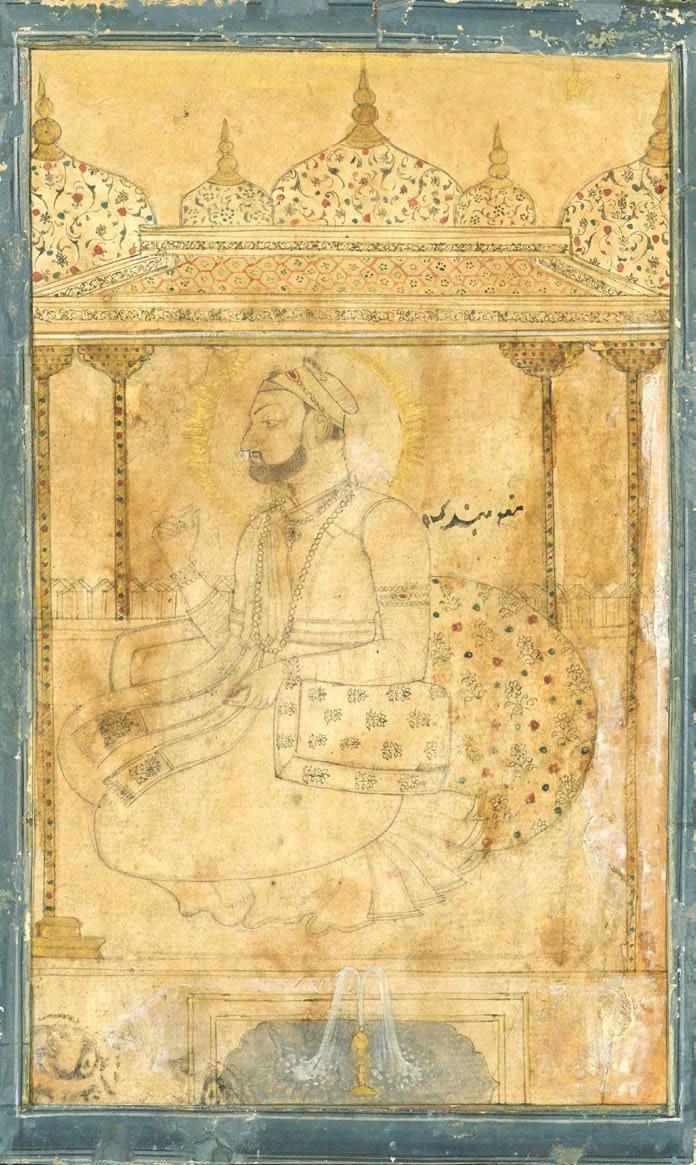

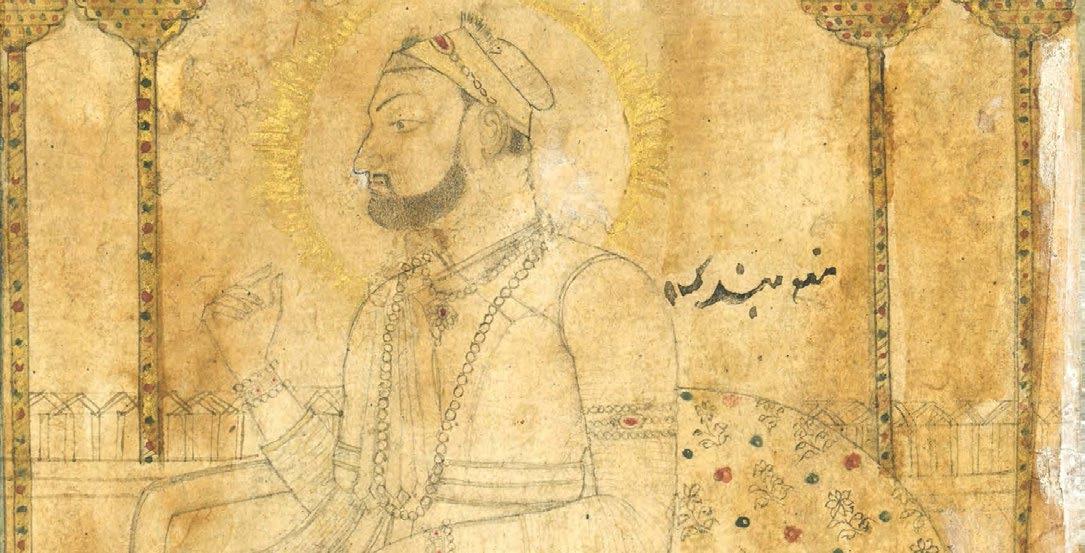

Shah Jahan at a Jharokha Window Mankot or Nurpur, mid-18th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 x 5 1/2 in. (20.3 x 14 cm.)

Folio: 9 x 6 in. (22.9 x 15.2 cm.)

Published: Pal, Pratapaditya, Romance of the Taj Mahal (Los Angeles County Museum of Art: 1989), p. 234-236, no. 254.

Emperor Shah Jahan is best known for commissioning the grand tomb of the Taj Mahal to memorialize his queen, Mumtaz Mahal, who died prematurely in 1631 from complications in childbirth. He himself was buried with her after his death in 1666.

Here, Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan sits in a half-length profile at an open window, gazing upward and holding a sprig of blossoms. He wears a transparent jama tied to the right and a gold, pearl and jeweled Mughal pagri with multiple necklaces of gold, pearls and precious gems. Two attendants stand to the left and right on striped carpets, waving peacock morchals.

The color palette of oranges, yellows and greens as well as the broad strokes may suggest a provincial origin in the Punjab Hills, possibly from the orbit of Mankot or Nurpur, as Dr. Pal suggests. Based on execution and color palette, one may discern some influences from folkish traditions in Rajasthan as well, and possibly Sirohi given its vibrant clashing of yellows and oranges.

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 7/8 x 7 1/8 in. (25 x 18.1 cm.)

Folio: 13 1/4 x 9 1/4 in. (33.7 x 22.9 cm.)

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 23 March 1999, lot 54. Christie’s London, 24 September 2003, lot 107. Christie’s New York, 14 September 2010, lot 194.

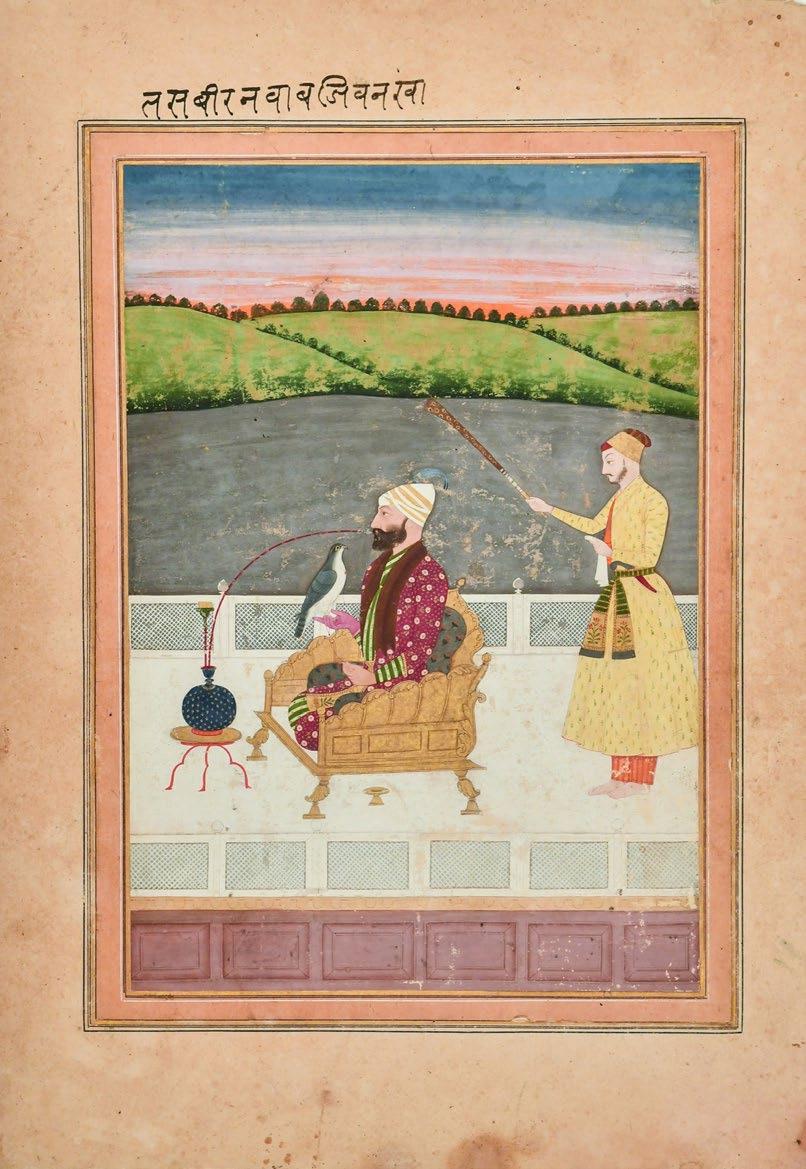

Nawab Jiwan Khan, identified by the Devanagari script in the top margin of the folio, sits in formal profile view on a low golden throne, holding his favorite falcon on a gloved hand, meditating as he calmly smokes from a long stemmed hookah balanced on a three-legged table atop a stark white marble terrace with a jali or lattice balustrade. An attendant stands silently behind him, waving a slender peacock-feathered fan symbolizing the nawab’s status and authority. The terrace overlooks a dark gray river and light green hills dotted with trees in the distance, the sun setting in vibrant red streaks.

Stylistically, the painting seems to stand at the intersection of Mughal naturalism and the Pahari style which became increasingly influenced by Mughal painting from the Muhammad Shah period (r. 1719-1748) forward. The Garhwal school, a lesser known Pahari-Rajput school of painting, can also be attributed to the influence of the Mughal Durbar: in 1658 two artists were brought there along with Mughal prince Sulaiman Sheikh who sought escape from his uncle Aurangzeb. The style developed thereafter, and increasingly so through interaction with neighboring Pahari ateliers.

Unfortunately, we know very little of Nawab Jiwan Khan, who was perhaps a Mughal governor based in the Punjab Hills. The following account of political events at Kangra, written in the nineteenth century, however, mentions him: “Raja Sansar Chand...was the most renowned of the Kangra princes. He flourished early in the present century, and was a contemporary of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. With the assistance of the Sikhs he regained possession of Fort Kangra from Nawab Jiwan Khan, son of Saif Ali; the (Mughal) Emperor Jahangir having some generations previously captured the place (Kangra) from Raja Chandrabhan.”

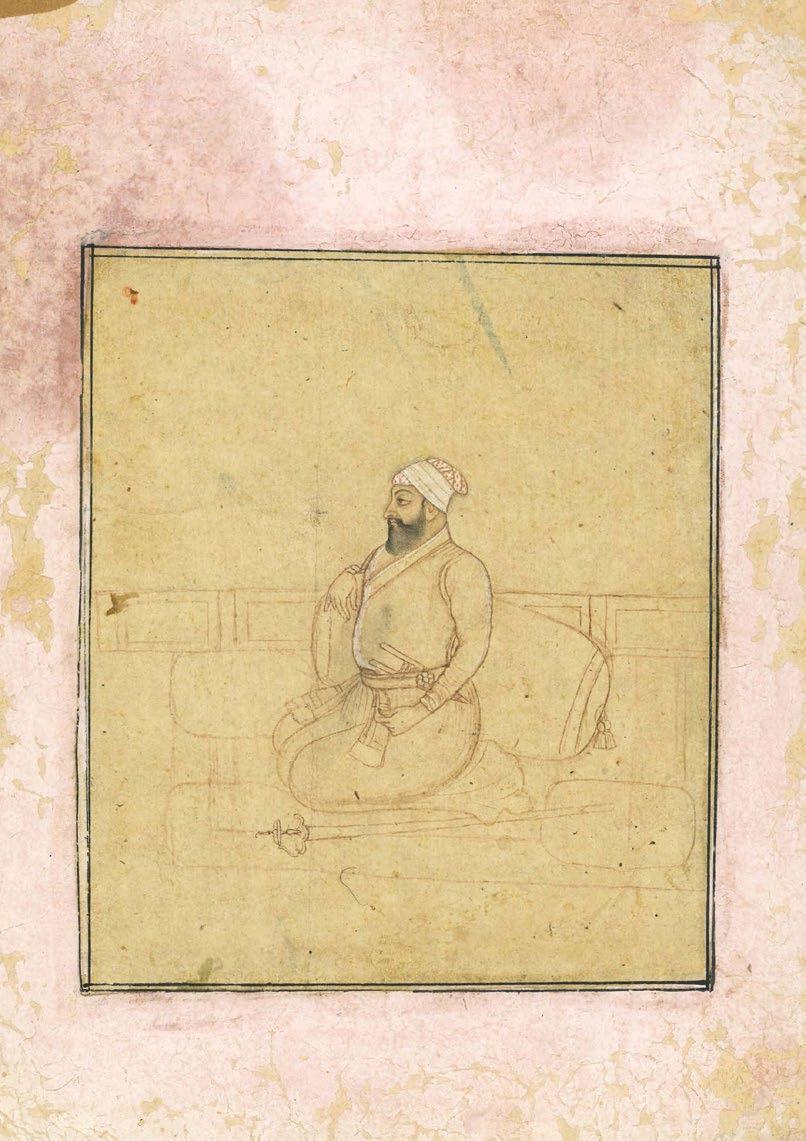

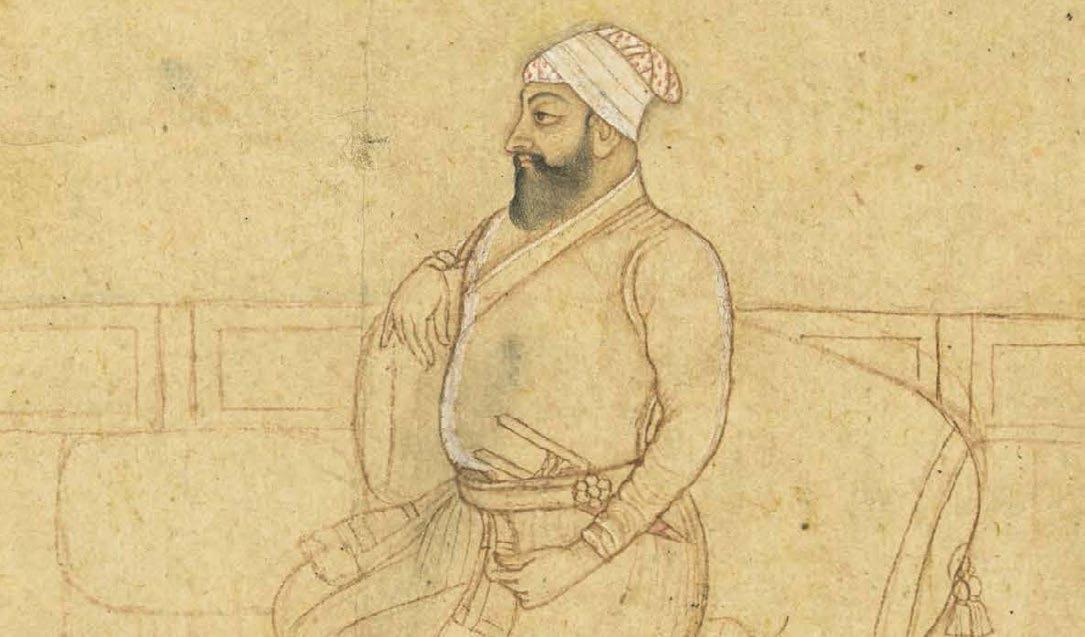

A Drawing of a Mughal Officer

Kishangarh, India, late 18th century

Ink drawing on paper

Image: 5 3/4 x 5 in. (14.6 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 9 1/2 x 7 1/4 in. (24.1 x 18.4 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

This lightly colored drawing depicts a Mughal nobleman seated against a bolster on a terrace, a katar tucked into his waistband and his sword below him. The portrait clearly depicts a real individual. Take note of his well-shaded face and portly physique as well as each hair of his beard and mustache, carefully delineated with minute brushstrokes.

The sitter resembles a nobleman in a similar drawing from Kishangarh inscribed with the name “Sa’id Musaffa,” which appeared at Sotheby’s in London in 1979.1 Sa’id Musaffa was described as an officer in the service of Asaf Khan, whom the figure in the drawing resembles and may, in fact, represent.

The painter Bhavanidas (ca. 1719-1748) was active at the Imperial Mughal workshops at Delhi until around 1719. Thereafter, he moved to the court of Maharaja Raj Singh (r. 1706-1748) at Kishangarh, and established a new painterly genre in the Kishangarh tradition based upon naturalistic techniques gleaned from the imperial ateliers. Bhavanidas specialized in depictions of horses and courtly personages, paving the way for his best student, Nihal Chand (1710-1782), to bring the Kishangarh style to full fruition. His student created images of Radha and Krishna in a highly-recognizable style, with angular facial features and famously elongated eyes.

Since the drawing is not inscribed, a specific artist or sitter cannot be identified. However, it is reasonable to ascribe the portrait to the circle of Bhavanidas; an artist from the Kishangarh workshop who utilized the techniques and training of the studio master. Thus, it is possible that this drawing was penned by Bhavanidas himself or by another artist working closely with him such as his son Dalchand, his nephew Kalyan Das, his famous student Nihal Chand or another member of the Maharaja’s atelier.

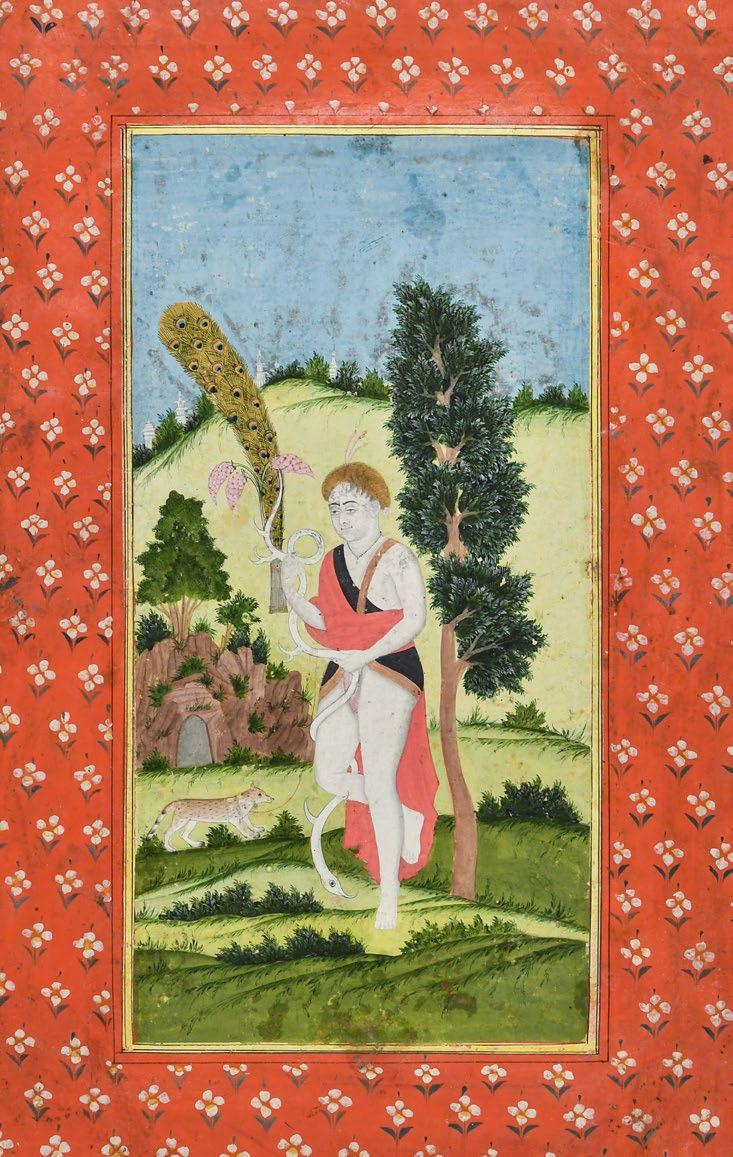

A Yogi in a Landscape

Hyderabad, Deccan, India, late 18th century

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 7/8 x 4 1/2 in. (22.51 x 11.4 cm.)

Folio: 14 3/4 x 9 7/8 in. (37.5 x 25 cm.)

Provenance:

From a private French collection, 2011.

A princely yogi stands balancing on tip-toe, one leg pendant, beside a leafy, slightly arched tree. The figure holds a winding branch as a crook, mounted with mauve blossoms at the top and a serpent’s head below. The branch twists around his leg, also acting as a leash for his tamed jackal. A grotto and a peacockfeathered tree sit behind him. A yellowish-green hilly landscape stretches out in the background with the marble turrets of a fortress peeking out behind.

This may be an image of the eleventh-century yogi Gorakhnath. However, there is no identifying inscription on the front or back of the painting to confirm the figure’s identity. A painting of a similarly-styled ascetic in Losty’s Indian Paintings 1590-1880, is inscribed with the name “Gorakhnath,” the founder of the Nath sect. Similarities include the landscape and the curiously winding staff. An important temple devoted to Gorakhnath is located in Ahmadnagar in the Northern Deccan. The present work likely originated south of this, in a location near Hyderabad.

A Princess Enjoying Paan on a Terrace Guler, India, circa 1790–1800

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 3/8 x 7 in. (18.7 x 17.8 cm.)

Folio: 9 1/8 x 8 3/8 in. (23.2 x 21.3 cm.)

Provenance:

Spink & Son Ltd., London, 1985.

Seated on an open white marble terrace before a blossoming tree and flanking cypresses, the princess strikes a ruler’s pose. She sits in a relaxed posture while wearing a courtly turban with an elaborate sarpech, atop a grand throne. The princess lifts a piece of paan to her mouth while two maids wait on her with a betel box and a chowrie. The ducks, captured in motion as they approach a small fountain in the foreground, highlight the fleeting moment frozen by this anonymous artist.

The painting is composed with a broad and vibrant color palette indicative of the Guler style. This naturalistic style of traditional Indian painting was developed by Hindu artists who were previously trained in the Mughal court. Paintings like this resulted from the patronage of Guler Rajas and typically possess a particular delicacy and spirituality, evidenced by the present composition.

Compare to four illustrations with similar female figures and vegetation published in Archer, Indian Paintings in the Punjab Hills, London, 1973, p.118, nos. 65–68.

Maharaja Prithi Singh of Ratanpur in Procession

Attributed to Pemji, Sawar

Madhya Pradesh, Ratanpur, circa 1790

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 14 ½ x 10 in. (36.8 x 25.4 cm.)

Folio: 16 1/2 x 12 in. (41.9 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

Maharaja Prithi Singh of Ratanpur is portrayed here smoking from a hookah as he holds the reins of a dignified white stallion, accompanied by an entourage of heavily armed troops, seemingly outfitted for battle. He wears a full length forest green jama enlivened with gold patterning and a fine gold and jeweled pagri with a gold and pearl sarpech . Multiple strands of pearls hang around his neck as a display of rank and a sheathed sword hangs by his side, a quiver of arrows on his opposite side. A double-handled katar peeks out below his right shoulder. Attendants surround the Maharaja–one waving a ceremonial fan, one holding up an orange thakur’s standard with a peacock design, and another holding the base of a silver hookah. The warriors carry matchlocks, arrows and other weapons while the procession slowly moves along on a low swath of green landscape. A blue-gray background ascends to a turbulent cloudy sky of dark blue and red, painted with vigorously applied brushstrokes.

The composition seems to define a visual case study in hierarchy as the imposing king and his elegant horse fill most of the page and lesser courtiers and lowly soldiers are depicted smaller, in accordance with their rank and importance. The identity of the royal figure is understood to be Prithi Singh, based upon inscriptions on the verso. His position is indicated by one honorific “shri,” probably indicating a rank of Thakur from the district of Ratanpur.

The artist Pemji is the most significant name associated with this later phase of painting at Sawar, one which has little stylistic connection to its earlier phase of the latter seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries. He was active at Sawar during the reign of Udai Singh (1752-1802), his son Ajit Singh (r.1802-12) and his successor Jaswant Singh (1812-1852). Pemji’s manner is vigorous, broadly painted and primal, casually rejecting the Mughal-influenced refinement sometimes associated with earlier Sawar paintings, a kingdom which allied itself politically with the Mughals since its founding in 1627. Pemji’s figures are puppet-like, yet ferocious. He employs a vibrant palette of occasionally clashing whites, oranges, blues and greens. There are few extant works attributable to Pemji (possibly less than a dozen) however, there are other collections with works ascribed to Pemji that include the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2004-149-52), Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Cambridge (1995.111), the San Diego Museum of Art (1990:639) and the Jagdish and Kamala Mittel Museum, Hyderabad (76.220), among others.

A Portrait of Munir-al-Mulk (called ‘Aristu Jah’)

Attributed to the circle of Rai Vekatchellam Deccan, Hyderabad, India, circa 1790-1810

Ink and gold on paper

8 x 4 3/4 in. (20.3 x 12 cm.)

Provenance: Private Belgian collection.

Under a gold and jewel-encrusted turreted canopy sits diwan Munir-al-Mulk, the prime minister of Nizam Sikandar Jah (r. 1803-1829), the ruler of Hyderabad. Munir-al-Mulk was often referred to by the name ‘Aristu Jah,’ which may cause some confusion due to the fact that the diwan to the previous Nizam, Ali Khan (r. 1762-1803), was also called ‘Aristu Jah’. The older diwan was an entirely different individual named Azim ul Umara, father of Saif al Mulk.

After the Subsidiary Alliance of 1800 between the British and Hyderabad and following the death of Ali Khan in 1803, his son Sikandar Jah rose to accept responsibility of the throne. The British had obtained fealty from his diwan, Shams ul Umara, but he died just five years into the Nizam’s reign. With the position of prime minister open again, the British tried to convince Sikandar Jah to appoint a candidate of their choosing. Instead, he appointed Munir-al-Mulk, despite not favoring him on a personal level. The Nizam knew he would be a capable leader and would stymie his colonial counterparts.

A painting in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (I.S. 163-1952) of Aristu Jah was attributed to the artist Rai Venkatchellam by Mark Zebrowski in his book Deccani Painting (1983). Therein, the Diwan is standing and smoking in the presence of petitioning courtiers. Similarities between that painting and the present drawing include the rounded head leaning slightly forward at the neck with an aquiline nose, neatly trimmed beard and the slightly smallish Deccani cap placed high on the brow. While the figure in the painting is identified as Aristu Jah in the museum’s archive, it is worth noting that it must be the present figure, Munir-al-Mulk (as Zebrowski states) and not Azim ul Umara; the painting is dated to 1810, six years after Azim ul Umara’s death.

Unfinished drawings of Munir-al Mulk appear to be scarce and this drawing –so archetypally Deccani with its depiction of lavish gold and jewels– is likely one of the very few extant drawings attributable to the artist (or circle of) Venkatchellam.

A Nobleman Holding a Hunting Falcon Kangra, India, circa 1790-1810

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 1/2 x 5 in. (19.1 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 9 2/3 x 6 2/3 in. (24.5 x 16.9 cm.)

Provenance: Rob Dean Art Ltd. (2010).

The nobleman stands with a tethered raptor perched on his hand, holding the stem of a silver-based hookah lifted waist high by an attendant. The falcon peers upwards, perhaps scanning the skies for possible prey.

This figure is not identified by an inscription but he strongly resembles Fateh Chand, brother of Maharaja Sansar Chand (r.1775-1823) of Kangra and uncle to Anirudh Chand (b. 1786), Sansar’s son and successor. He appears in numerous paintings standing or sitting behind the young Anirudh as the prince looks at pictures and plays at Holi. J.P. Losty has recently (2017) identified the Guler artist Kushala and his workshop active at Kangra as responsible for those portraits of Anirudh Chand and his court, which include depictions of Fateh Chand.

Based on elements of style, the origin of this painting may be placed at the ateliers of Maharaja Sansar Chand of Kangra and possibly thus to the workshop of Purkhu, the best-known artist (chitara) active at the Maharaja’s royal painting ateliers.

This miniature also recalls a painting once in the James Ivory Collection, of Bir Singh of Nurpur, and although the present painting is a portrait of a different nobleman, the style is similar with a flat expanse of yellow ground with arching skyline and similar figural composition.

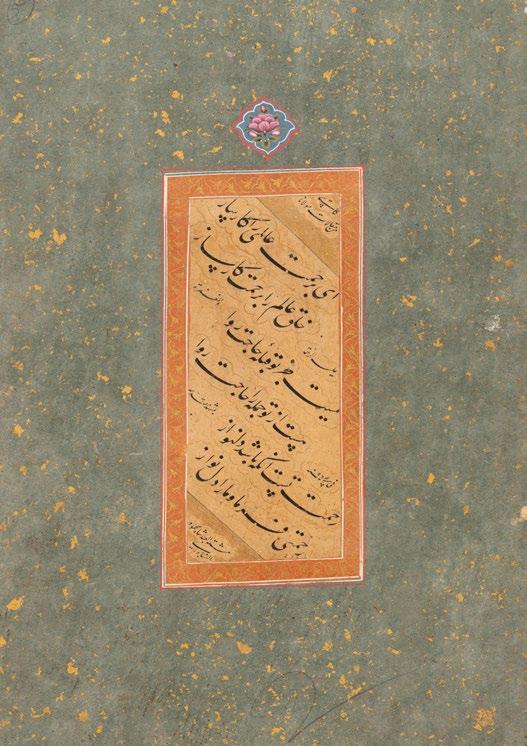

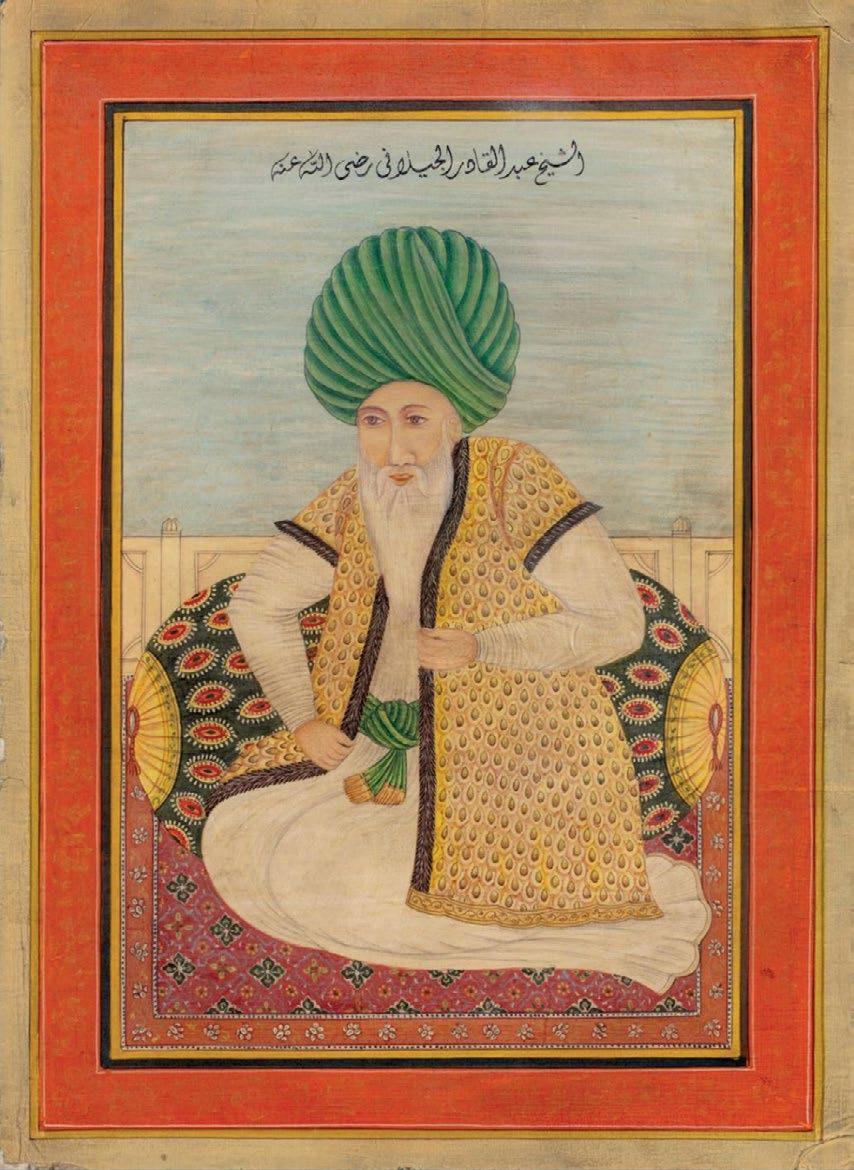

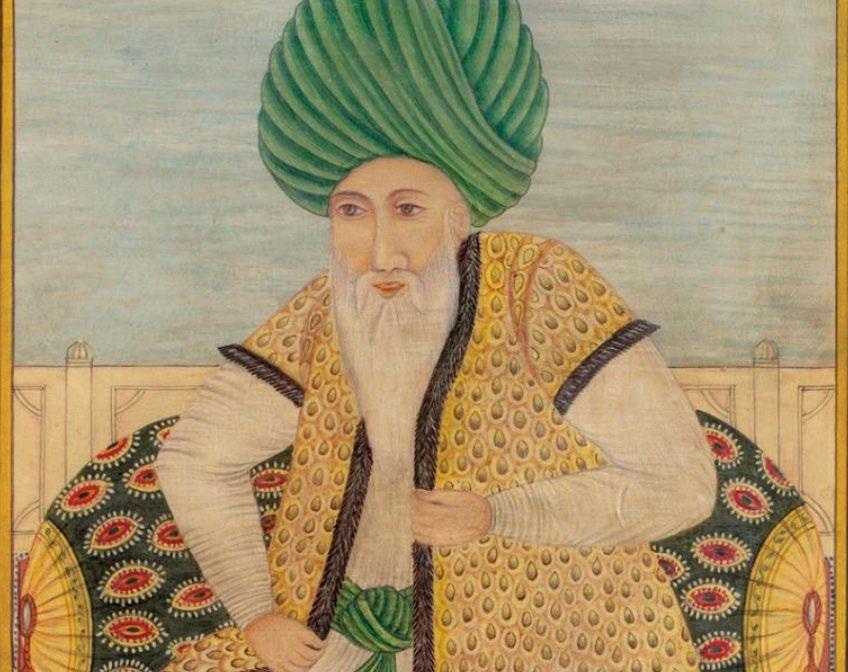

Master Sufi al-Shaykh Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani

Deccan, India, 19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 3/4 x 5 7/8 in. (22.2 x 14.9 cm.)

Folio: 11 1/4 x 8 1/4 in. (28.5 x 21 cm.)

Provenance: Private European collection.

Founder of the Qadiriyah order of the Sufi faction of Islam, Abd al-Qadir alJilani (1077/78-1166) is a highly venerated yet historically ambiguous figure. He is revered as a Sufi, or mystic follower of Islam whose purpose is to pursue truth of divine love and knowledge through a personal relationship with God. After wandering the Iraqi desert for twenty-five years in solitude, he came to Baghdad where he grew to be a known teacher, gaining followers from surrounding regions and converting a number of Jews and Christians.

Al-Jilani was fifty years-old when he started preaching in Baghdad, likely accounting for his advanced age in this and other miniature paintings. The reach of this Islamic sect was initially regional, but al Jilani’s forty-nine sons spread his philosophies through Central Asia, India, and parts of Africa. In the subcontinent, his name is still invoked when contagions like cholera or other epidemics run rampant. Devotees will parade al- Jilani’s dark green flag around and recite chants to the saint for relief.

The present painting depicts the Sufi master leaning against a large cushion and wearing a turban that identifies him as a descendant of the prophet. A Diwani inscription within the top border of the folio identifies him. On the verso is calligraphy of a Persian mystical text.

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

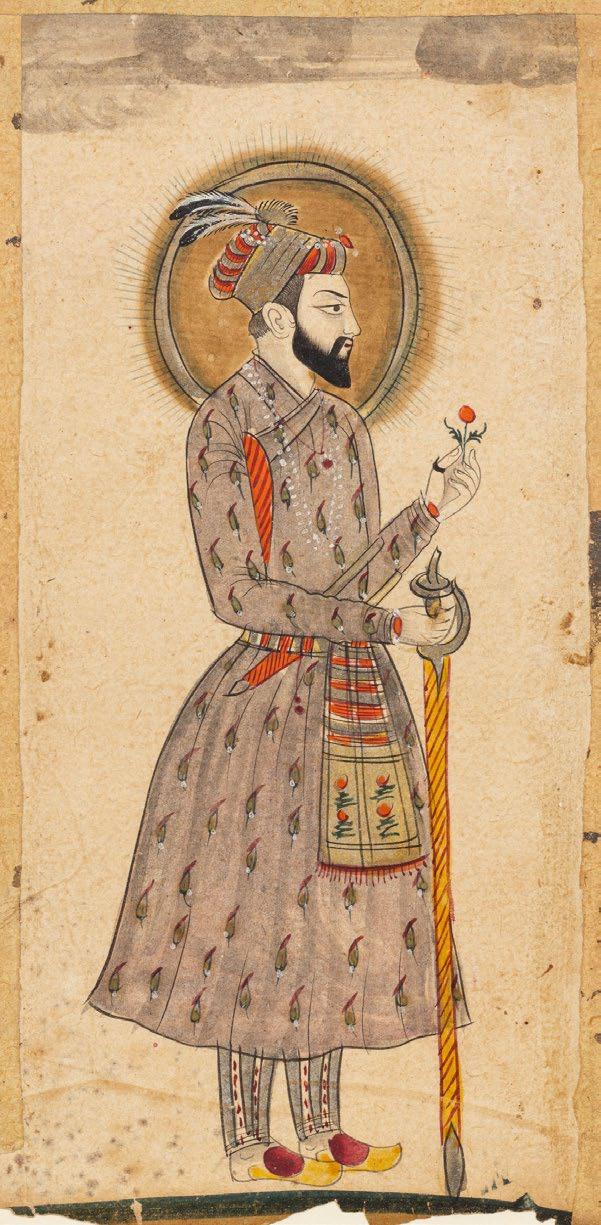

The Deccan artistic style first developed in the Muslim capitals of the Deccan sultanates. While it reached its height between the late sixteenth and midseventeenth centuries, the style experienced a revival in the eighteenth century, centered around Hyderabad.

In this portrait, the nimbate nobleman is shown in profile, ensuring that his full visage remains unseen. He holds a red rose in his left hand—a royal Mughal emblem symbolizing sovereignty, power, and dynastic authority—and a tulwar in his right, underscoring his martial prowess. The halo, full-length format, subtly narrowed shoulders, three-quarter body turn, and the unadorned background without a groundline all reflect Mughal portrait conventions. The figure wears pleated garments ornamented with florals, resembling traditional Deccani attire. The nobleman’s jeweled turban is topped with two feathers, while a string of pearls drapes across his chest and bracelets encircle his wrists, further emphasizing his elevated status.

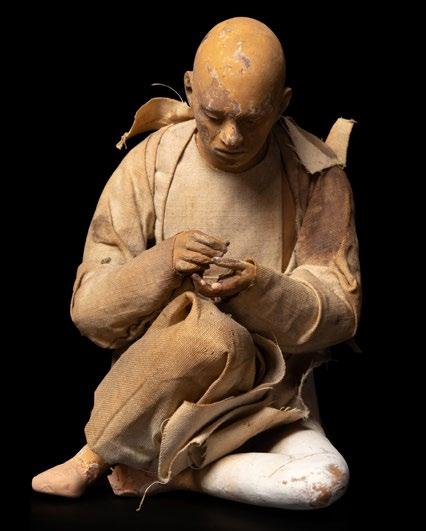

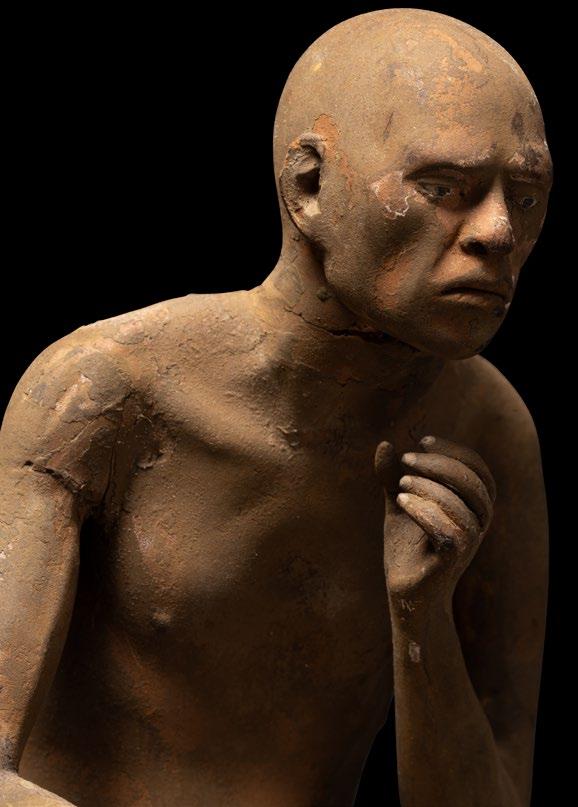

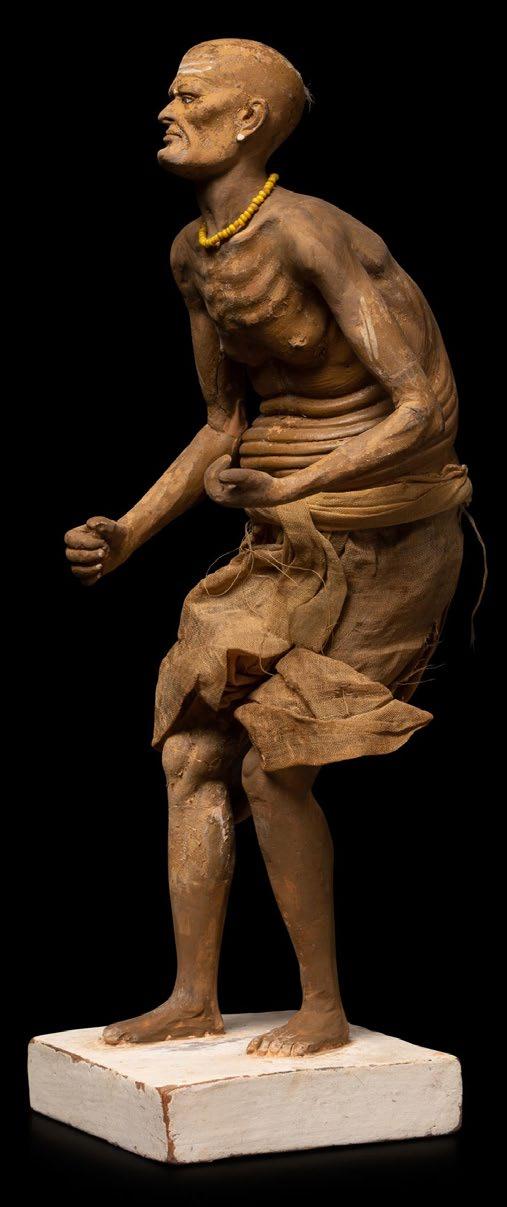

22 Indian Clay Figures

Attributed to Jadunath Pal Krishnanagar, India, 19th century Clay, hair, cloth 11 1/4 in. (28.6 cm.) and under high

Provenance: Private Ohio Collection.

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

Provenance:

Imam Kuli Khan Governor of Shiraz in a Feathered Headdress Deccan, India, early 19th century

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 1/2 x 4 1/2 in. (19.1 x 11.4 cm.)

Folio: 13 3/4 x 8 3/4 in. (34.9 x 22.2 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

The present portrait is painted in the nim qalam (half-painted) style. Kuli Khan is shown half-length, seated on a throne with gold jeweled finials as he leans against a mauve bolster. He holds a small, round nut in his left hand. The figure is dressed in a gold floral coat with a fur collar. He wears a distinctive turban with multiple plumes of black and white heron feathers (kalgi) set into a golden, bejeweled sarpech. Imam Kuli Khan’s lavish taste is evidenced by the sumptuousness of his costume.

The following was excerpted from an account of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier’s travels to Persia, circa 1632, as described by S. Richardson et al. (1759):

“This khan was prodigiously rich; and so very magnificent, that his expenses almost equalled those of the king, which occasioned Shah ‘Abbas I, who talked with him one day on that subject, to tell him that he desired him to spend one penny less than he every day, that there might be some difference between the expenses of a Shah and a khan.”

For a similar but fully painted depiction of Imam Kuli Khan from the Hagop Kevorkian Fund, see Sotheby’s, London, (3 April 1978, lot 89), a another portrait of the Khan and its period described as mid-seventeenth century. The present portrait, perhaps based upon this earlier example, has been inscribed in nasta’liq script, “Imam Kuli Khan of Shiraz.”

European Lady Drinking Wine

Kotah, India, circa 1800

Opaque watercolor with gold on paper

Image: 10 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (27 x 18.5 cm.)

Folio: 11 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (29 x 20.5 cm.)

Provenance:

Sotheby’s New York, September 17, 2009, lot 89.

A young woman holding a small cup of intoxicating drink looks at us coyly in a flirtatious three-quarter frontal pose. She wears attire fashionable with Europeans living in India in the latter eighteenth century, including a Portuguesestyle hat surmounted by a gold ornament. Her curly brown hair is a visual clue often employed in Indian paintings to indicate women of European descent, and suggests to us that she is probably indeed an actual European - a faranghi or foreigner - and not just a Rajput princess pretending to be one. Her bold frontal pose suggests that she is a courtesan while her layered necklaces, gold rings, bracelets and pearl nose ring remind us of her successful status.

Several other paintings of Portuguese ladies have been attributed to Kotah (see O.C. Gangolu, Critical Catalogue of Miniature Painting in the Baroda Museum, Baroda, 1971, pl. VIII, no. A; Sotheby Catalogues, Dec. 7, 1971, lot 98 and Dec. 12, 1972, lot 113). Two paintings in particular, one published in Indian Miniature Painting: Manifestation of a Creative Mind (Daljeet, et al. Brijbasi Art Press, 2006. p. 176-177), and the other in The Sensuous Line: Indian Drawings from the Paul F. Walter Collection. (Pal, Pratapaditya and Catherine Glynn. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976. cat. 22), are especially similar. Although stylistically divergent, all appear in almost the exact same pose, with identical hats, curled hair, undulating cloaks, and small cups pinched between two fingers.

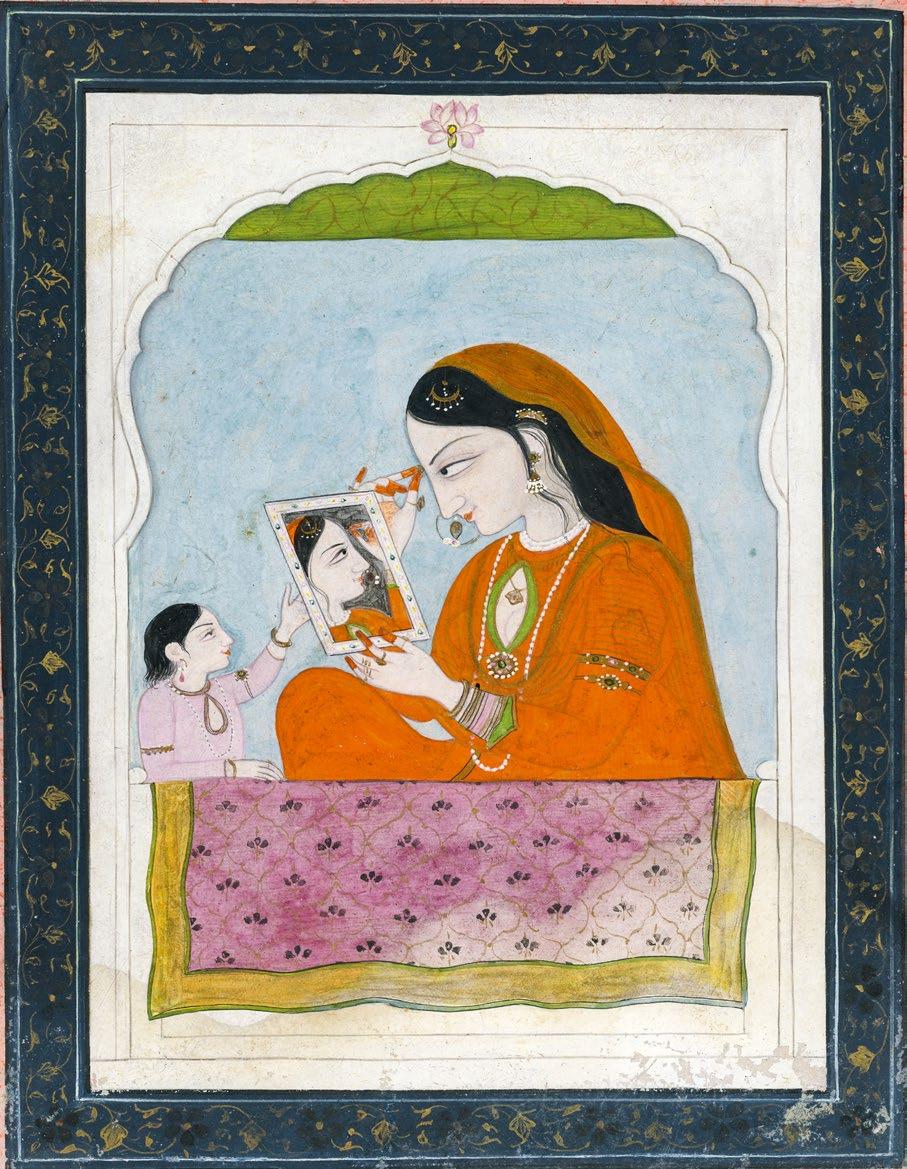

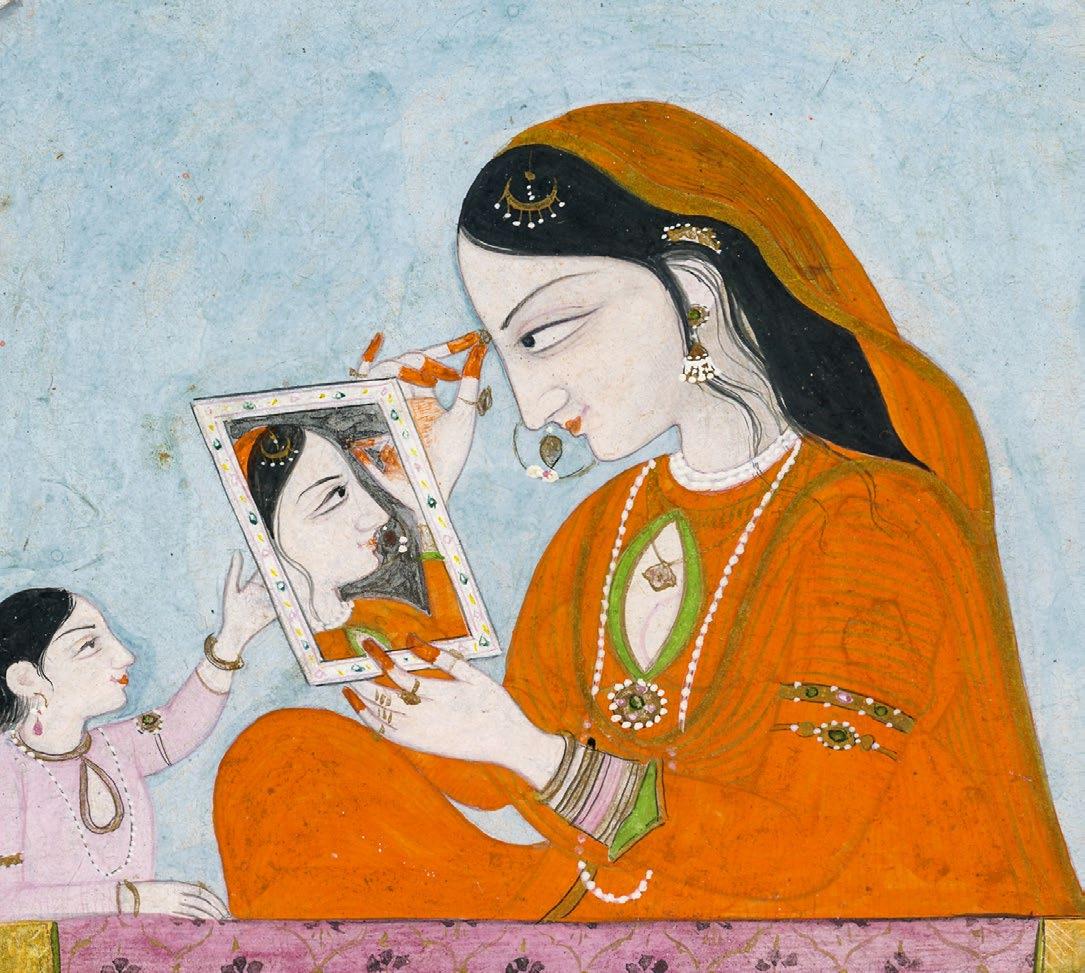

Maiden with a Mirror

Kangra, India, circa 1810

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 4 7/8 x 3 5/8 in. (12.4 x 9.2 cm.)

Folio: 6 x 4 7/8 in. (15.2 x 12.4 cm.)

Provenance:

The Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968 (no. 39).

The wide and focused eye of the young maiden directs the viewer’s gaze directly to the figure’s hand with which she applies kajal in a mirror held by an affectionate child. She has already adorned herself with a tikka (hair ornament), nath (nose ring), earrings, necklaces, armbands, and rings. The vermillion on each of her fingertips matches that of the three layers of her diaphanous garments, decorated with green edges matching the window valence above. She appears to be preparing herself for an important event for which the child below has already been groomed. The child’s lavender dress matches the magenta and yellow textile that hangs over the base of the window, creating a pleasingly cohesive color palette.

The charming portrait is unmistakably Pahari, epitomizing a bold and colorful tradition that embraces naturalistic Mughal techniques. This type of architectural framing (a view through a window) is typical among paintings from Kangra, in particular, as is the deep blue border with a gold foliate motif and a secondary support of speckled pink paper.

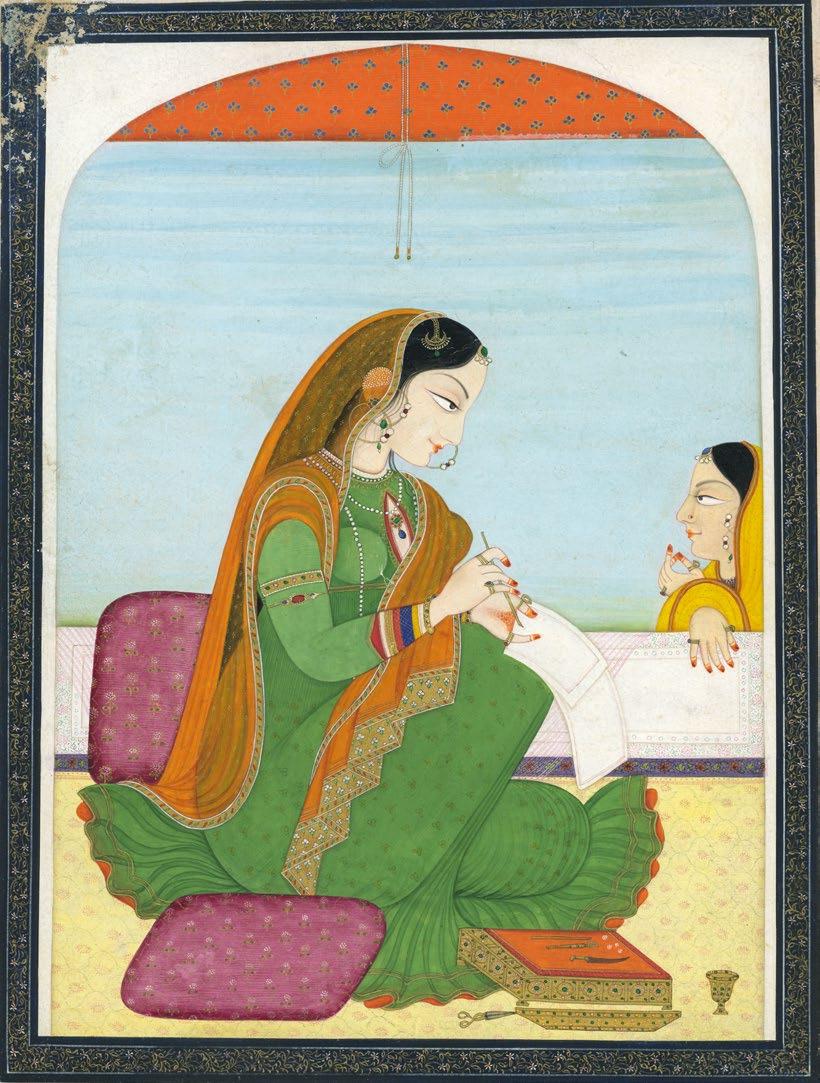

A Nayika Writing a Note

Kangra, India, circa 1810-1830

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 8 1/4 x 6 in. (21 x 15.2 cm.)

Folio: 9 3/4 x 7 3/4 in. (24.8 x 19.7 cm.)

Published: Sharma, Vijay. Painting Traditions of Kangra. p. 95.

Provenance:

The Collection of Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968.

Within the frame of an arched window, a nayika (heroine) sits on a carpeted terrace dressed in a flowing green sari and orange veil with gold trim. She wears large ear and nose rings, strands of pearls and numerous jewels and ornaments. Her female companion awaiting the finished note to deliver to her beloved. Below, writing implements on a covered gold and jeweled plinth appear along with a knife, scissors, a small gold cup and a bowl.

The central female represents the consummate Kangra heroine, with a demurely lowered gaze and an archetypal profile, sharply defined features and jet black hair. Her fine nose, small red lips and shapely chin are enhanced by her subtle smile. Whether the figure is a courtesan or princess, this is an idealized rendering of a nayika, her features displaying the classic look of a perfect Pahari heroine found in countless miniatures since the development of the Kangra style. The present painting is a wonderful example of the pan-Pahari style of Kangra originated at Guler as a response to the increasing influence of naturalistic Mughal painting.

Maharana Bhim Singh Riding a Caparisoned Elephant

Attributed to a follower of Chokha Mewar or Devgarh, India, circa 1820-1840

Gouache heightened with gold on paper 11 1/3 x 8 in. (29 x 20 cm.)

Provenance: Sas Cornette de Saint Cyr.

The portly Maharana Bhim Singh of Udaipur (r. 1778-1828) sits atop the center of a lumbering elephant, his sardars seated next to him waving chowries. His many attendants walk beside him holding a royal standard, a parasol, fan, a hookah and so forth. The majority of the ground is an empty, verdant landscape with only a small bit of foliage near the horizon line.

A respectful noble, probably a member of the royal Sisodia household, approaches the rana with hands in prayer as Bhim Singh looks impassively forward, his elephant’s stride also unhindered. A thin white crescent and dot symbol, the sign of the Sisodia clan’s devotion to the god Shiva Eklingji, hovers above the maharana on the green hillside above.

The present portrait was likely produced by a follower of the famed artist Chokha, who worked closely with Bhim Singh throughout his reign. Although works by Chokha tend to have much more elaborate backgrounds, his influence can be seen in the modeling of the figures. As elucidated by Topsfield, “The typical Chokha figures of the next twenty years—short, thickset, large-eyed and placidly sensuous, the men bullnecked and hirsute, the women comfortably rounded and somewhat bovine, all of them amiably languorous and inclined to pleasure—grew out of this unusual, earthy rapport between royal patron and painter” (Topsfield, A., Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar, Artibus Asiae, Zurich, 2002, p. 122).

8 5/8 x 8 5/8 in.

x 21.8 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

This portrait was likely once part of an album illustrating the various castes and professions of South India, comparable to a notebook of 26 paintings attributed to Pondicherry, dated circa 1830–40, now preserved in the National Library of France (Smith-Lesouëf 10105). Such albums, fashionable in the 19th century, were created in the so-called “Company School” style for a European clientele, initially connected with the East India Company.

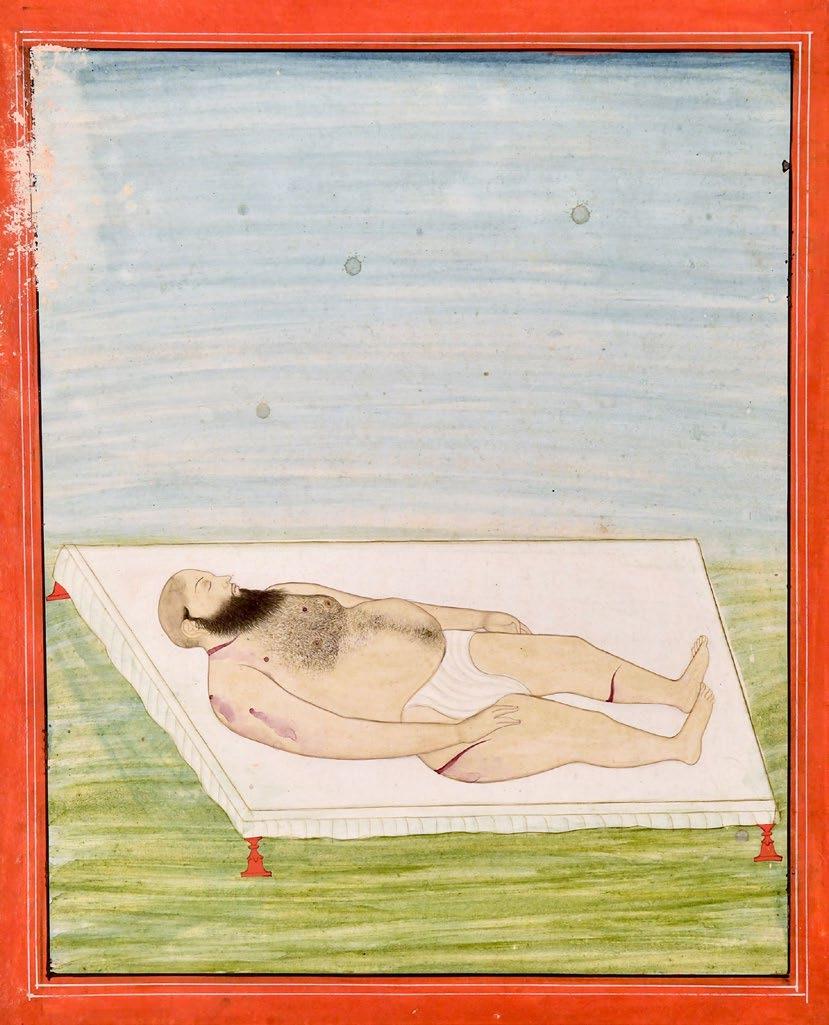

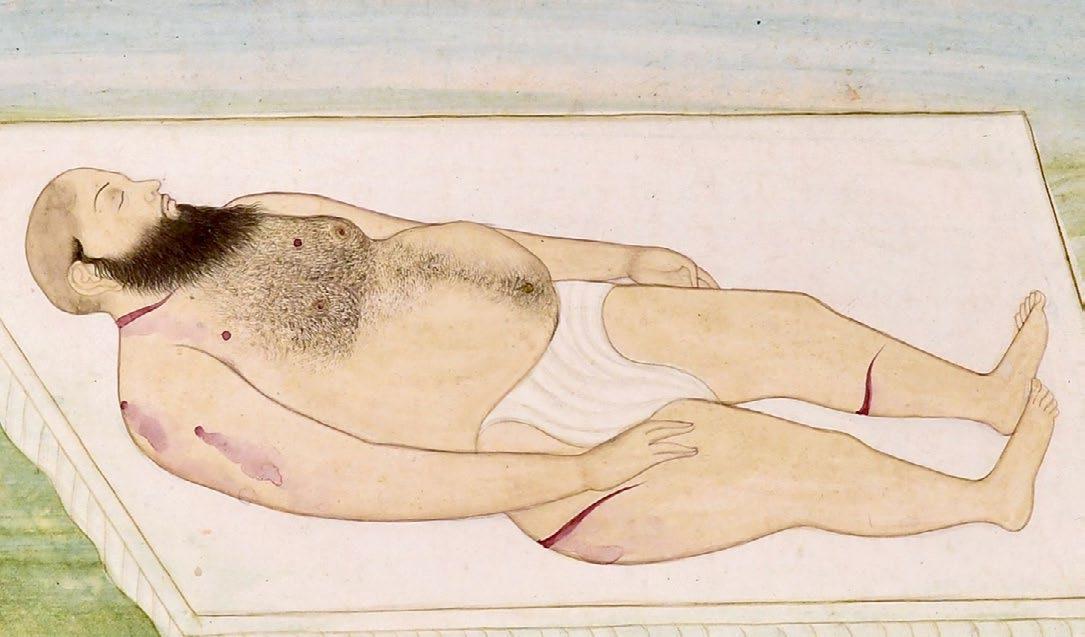

Khalifah Sayyid Ahmad Lies Dead Deccan, India, circa 1831-1850

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (24.1 x 19.1 cm.)

Folio: 11 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (29.8 x 24.8 cm.)

Inscribed verso in black ink Nasta’liq and below in an English hand: “Khalifa neer Saiyed Ahmed of Rai Barilly who fought against Ranjeet Singh in the Punjab at Balakoti and was ultimately murdered.”

Provenance:

The collection of Shri Ishwari Singh ji Chandila of Sirmur, no. 11 (as inscribed on the verso).

Sayyid Ahmad (1786-1831) was considered a Khalifah (or ‘Caliph’) by his conservative Sunni Muslim followers based in the Peshawar Valley, who called for jihad against those he perceived as enemies of Islam–first against the Sikhs led by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and then, the British. He fought to create an Islamic caliphate and his influence spread across Northern India all the way east to Bengal and south to the Deccan.

The Kalifah lies here naked except for a loincloth on a low bed covered with white linen. He has been shot several times and shows multiple sword slashes. The detail is so precise that each hair on his beard and chest can be counted and a sense of his girth and his weight are aptly conveyed. The scene is set against a ground and sky of lightly painted, thin washes of green and blue, drawing the eye straight to the corpse. This is an unusual and macabre image. The historical subject is also rarely depicted.

We do know that after the battle of Balakot in 1831, which the Khalifah led against the army of Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Sayyid Ahmed was killed and beheaded. In that battle, the Khalifah’s forces were decisively defeated by the larger, more professional Sikh army. Such is referenced in an English inscription on the painting’s verso, likely a contemporary account written by a member of the British Raj states. It follows that, here, his body appears lifeless in a loincloth.

Jacquemont, a French botanist who visited the Raja’s court in 1830 and 1831 provides a revealing personal impression of the Khalifah by his enemy Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh: “I have spent a couple of hours on several occasions conversing with Ranjit...but this model asiatic king is no saint, far from it. He cares nothing for law or good faith...but he is not cruel. He orders very great criminals to have their noses or hands cut off... but he never takes a life.”

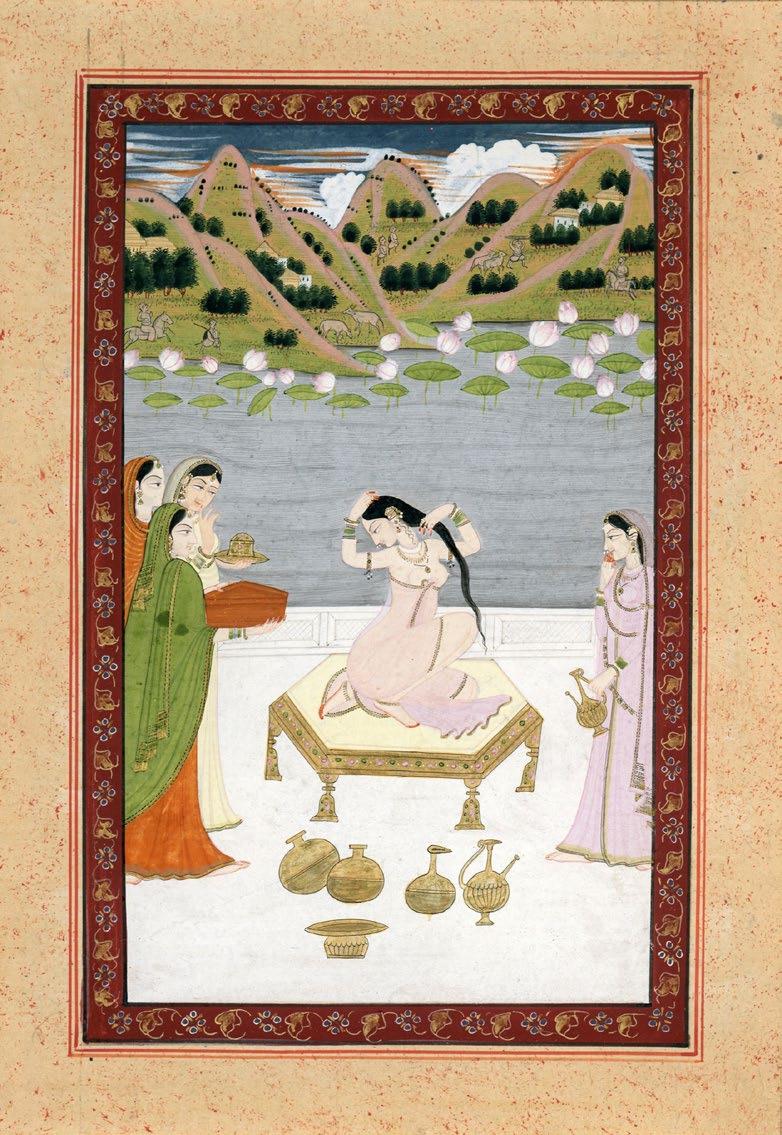

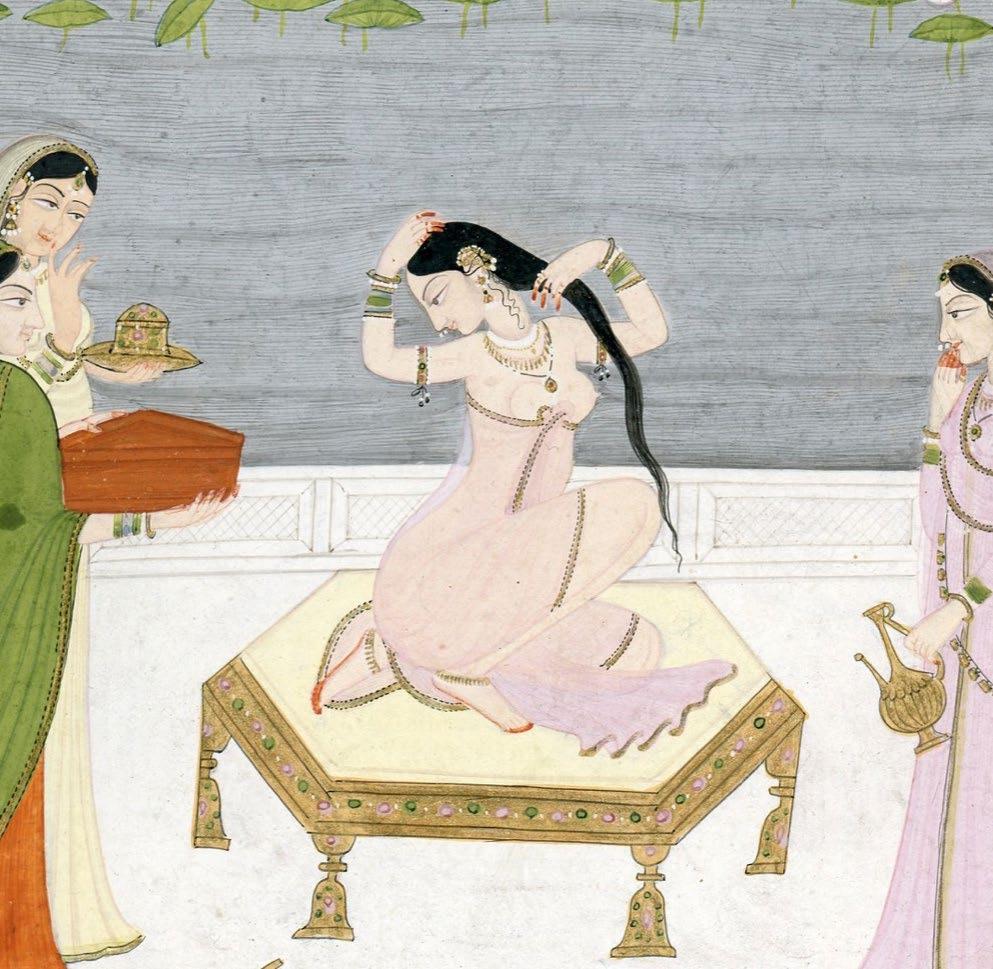

A Nayika Preparing to Meet her Beloved Kangra, India, mid-19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 7 2/3 x 5 in. (19.5 x 12.7 cm.)

Folio: 10 1/2 x 7 in. (26.7 x 17.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 6 July 1978, lot 64. The collection of Dr. Alec Simpson.

A nayika kneels on a gold and jeweled plinth, naked except for a transparent wrap and gold jewelry. Her lithe body turns as she wrings out her long black hair on the white marble terrace of the zenana. The woman is accompanied by four attentive handmaidens holding vessels that contain body oils, perfumes, ointments and lac for the palms of her hands and soles of her feet. As she prepares to greet her lover, the air is tense with anticipation. The blue, cloudy sky is streaked with red, rendering an evening sunset. In the middle distance rises a gray lotus-filled pond, the blossoms and leaves large and freshly blooming. In the far distance, a village set among steep hillsides is visible. Amidst its population of cowherds and small structures, two tiny mounted nobles gallop in from the left and right.

Compare these landscape features to a work signed by the artist Har Jaimal in W.G. Archer’s Visions of Courtly India, 1976, no. 73 and 74.

Image: 9 1/2 x 5 1/2 in. (24.1 x 14 cm.)

Folio: 10 1/4 x 6 1/4 in. (26 x 15.9 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

Maharao Ram Singh (1811-1889) of Bundi stands tall, dressed in a magnificent white and gold jama with an orange and gold patka or waistband, an ornate pagri and a radiant halo. The Maharao is identified by an Devanagari inscription on the painting’s verso. Here, he is depicted majestically as a dignified young king, perhaps thirty or so years-old and shown in a regal profile view. He holds a small flower in one hand while keeping his sheathed sword and katar at the ready. The motif of the ruler holding a blossom and a sword may be understood as emblematic of sensitive and martial qualities—representing a king who can appreciate the delicate and ephemeral fragrance of a flower but will fearlessly face his enemies when provoked.

According to James Tod in his Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, Ram Singh was “... the most conservative prince in conservative Rajputana and a grand specimen of a true Rajput gentleman.” He maintained an excellent reputation during his long reign (1821-1889) among both his direct subjects and the British. He was the son of Maharao Bishan Singh (1770-1821) and a member of the Hara family of the great Chauhan Rajput clan which inhabited the region around Bundi for centuries. Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah I conferred the honorific title ‘Maharao’ upon these rulers for their great service to the Mughal Empire.

Provenance:

Property from a Private Dutch Collection formed in the 1950s and 1960s.

Provenance:

From a Park Avenue Collection, acquired throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Image: 9 x 12 in. (22.9 x 37.5 cm.)

Folio: 12 x 14 3/4 in. (37.5 x 30.5 cm.)

Provenance: Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

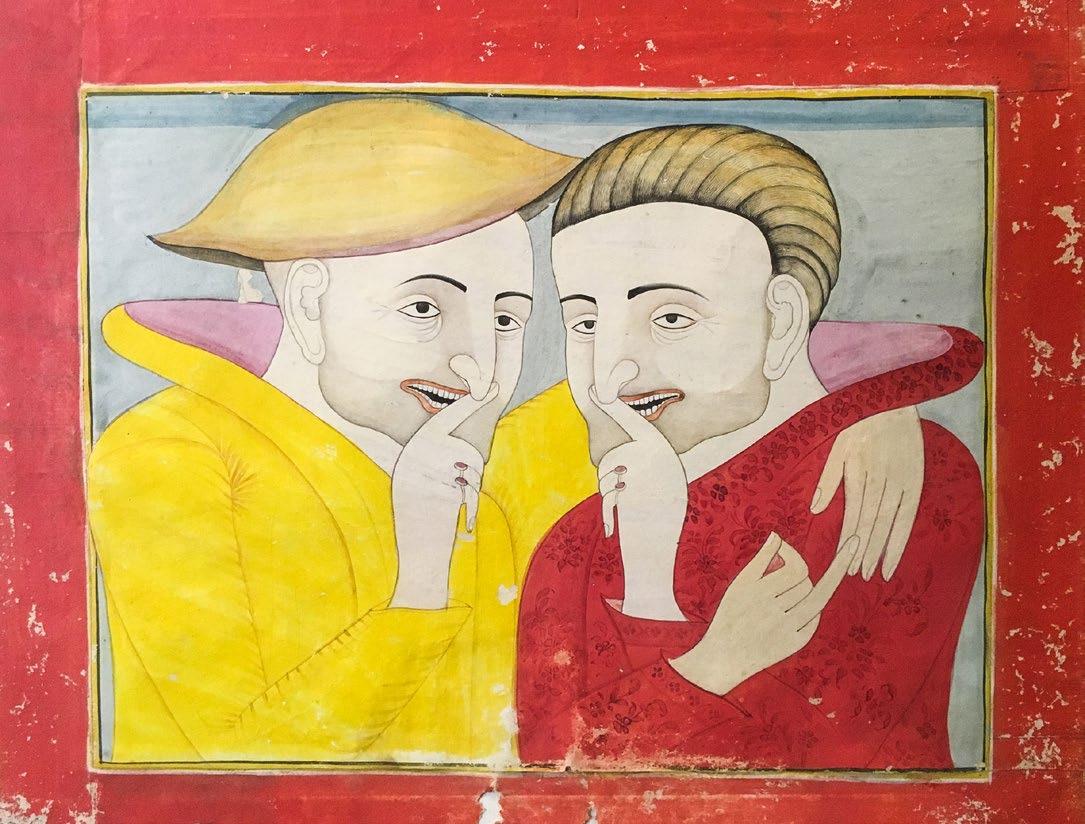

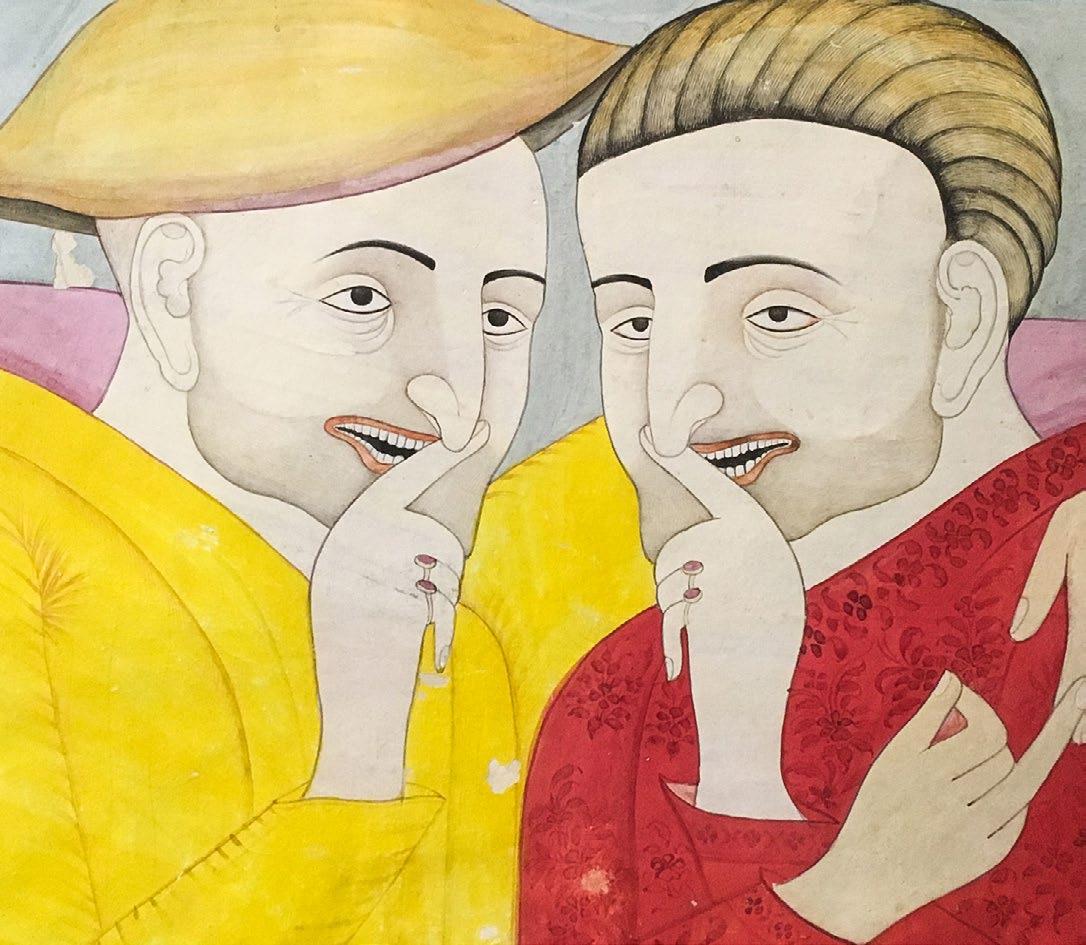

Firangi portraits were a popular subject for Indian painters who became enraptured by the exotic dress and strange customs of the European foreigners they encountered, either in person or through prints and reproductions of European artworks. This particular subset of the firangi genre, which was popular in Mewar, seems to have been modeled after a painting attributed to Pieter Balden, circa 1600, which illustrates the Dutch proverb “the world feeds many fools.” Reproduced in etchings that likely were brought to India via the Dutch East India Company trading mission led by Johan Ketelaar in 1711-1713, the painting inspired a host of unflattering Mewari caricatures depicting grinning fools.

The present portrait depicts two leering figures exposing mouths full of teeth–their fingers held to their noses in an allusion to the use of snuff. The man on the left has his arm outstretched to hold his friend in an embrace as the man on the right reciprocates the touch. The hooded robes, positioning of their hands, and hooked noses are particularly reminiscent of the Dutch engravings. For more examples of European caricatures from Mewar, see acc. M.2001.229.3 and M.85.147 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

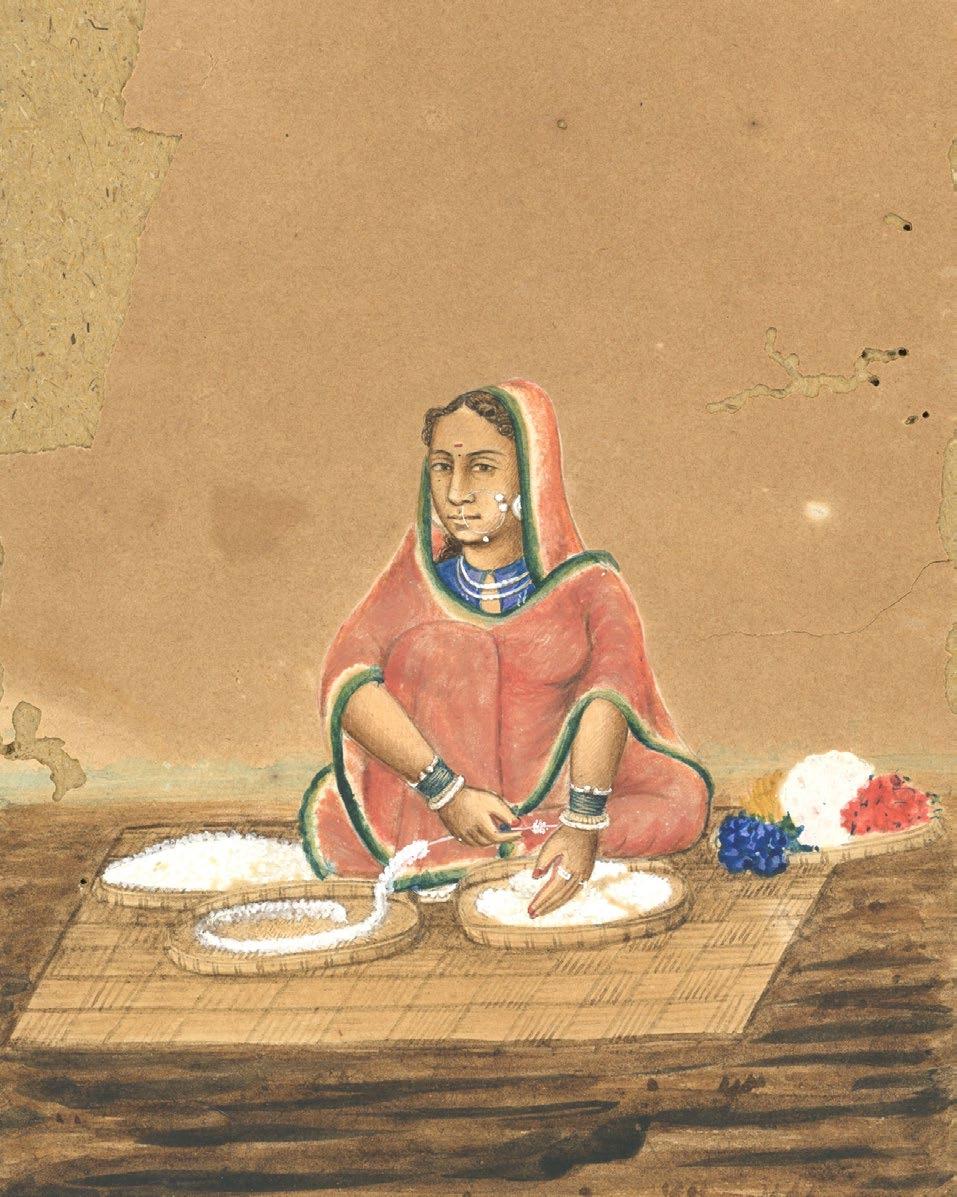

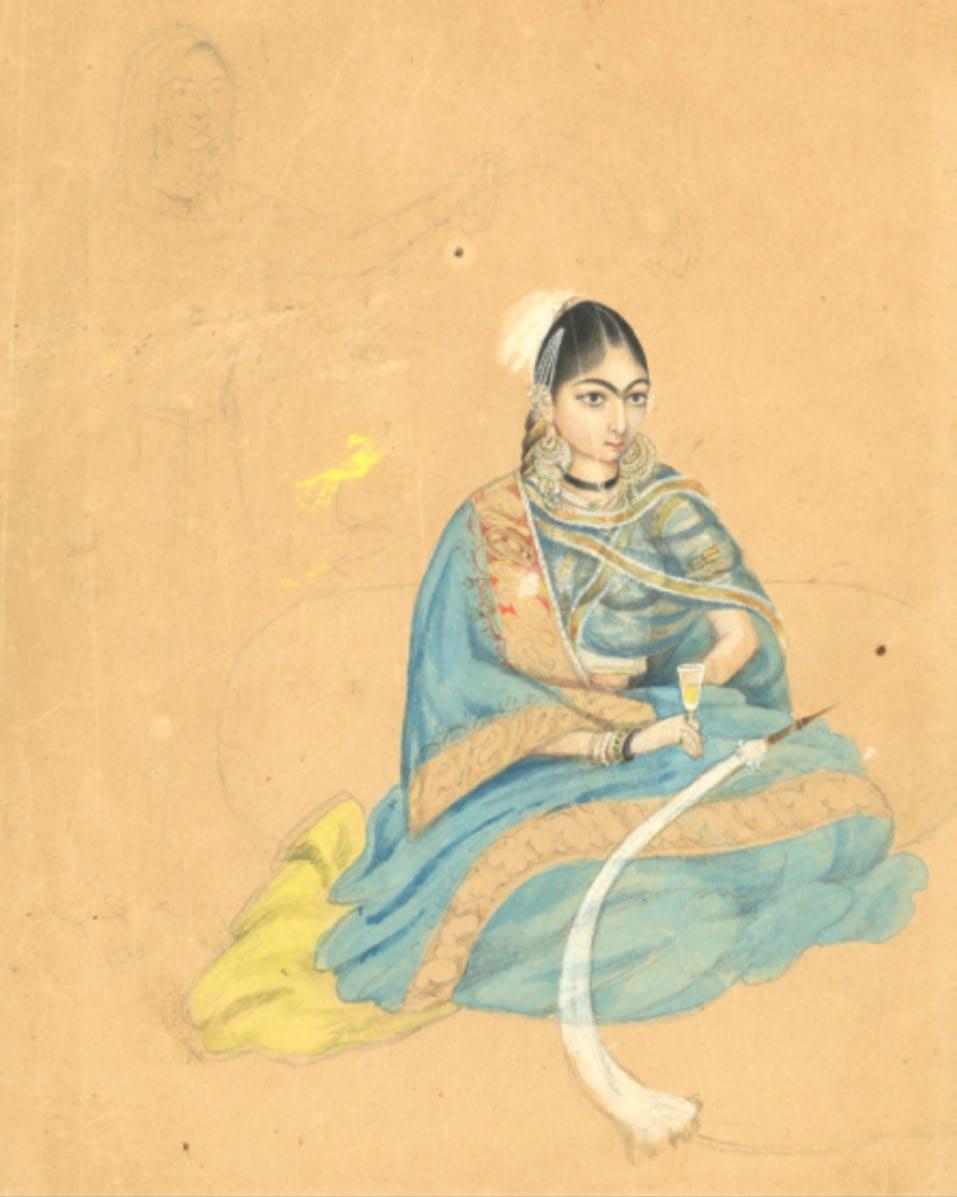

VOL I, Plate 8: A Bengali Woman PARKS, Fanny [Frances Susanna Archer] (1794-1875), PARLBY, Major Samuel (1789-1878, Lithographer), LUARD, John (1790-1875, Illustrator), D’OYLEY, Charles (1781-1845, Engraver)

Wanderings of a Pilgrim, in Search of the Picturesque, During Four-andTwenty Years in the East; with Revelations of Life in the Zenana Illustrated with Sketches from Nature Volumes I and II

London: Pelham Richardson, 23, Cornhill

Printed by Gilbert and Rivington, St. John’s Square, 1850

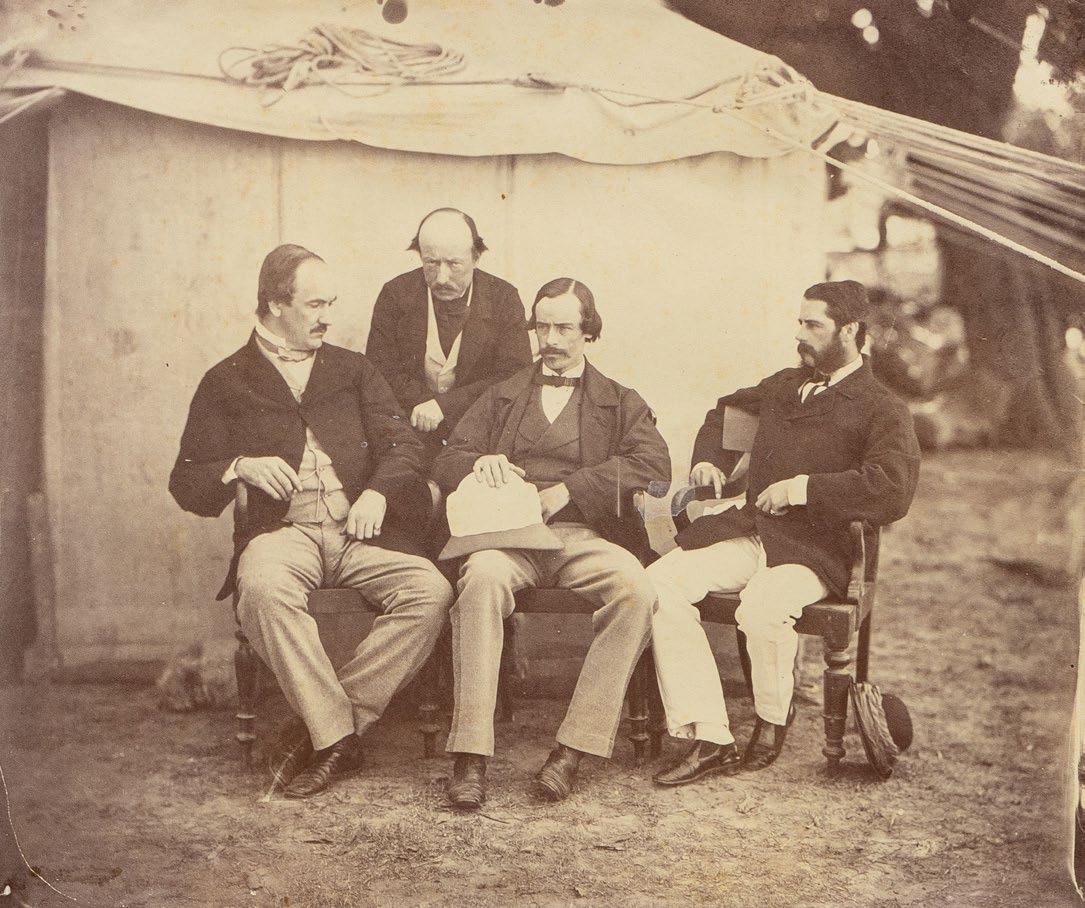

Oldfield (Henry Ambrose, 1822-1871), Rajman Singh Chitrakar (1797-1865) and Others

An India, Nepal, Kashmir & Afghanistan Album, circa 1850-1880

Photographs, watercolors, and drawings

15 1/2 x 17 in. (39.37 x 43.18 cm.)

Provenance:

Lieutenant General Sir James Hills-Johnes VC (1833-1919); thence by descent.

This is an important and extensive mid-19th century album documenting HillJohnes’ time in India, Nepal, Kashmir & Afghanistan. The album consists of 160 photographs and 13 original artworks, compiled by Lt. Gen. Sir James Hill-Johnes VC (1833-1919), including approximately 88 portrait and group photographs measuring from approx. 185 x 140 mm to 135 x 105 mm and smaller, 48 larger group, camp and landscape photographs approx. 175 x 235 mm, 24 large group and landscape photographs approx. 245 x 300mm, 12 large watercolours and drawings approx. 285 x 370 mm, and one smaller drawing approx. 115 x 190 mm, mounted on 66 leaves, contemporary black straight-grained half roan, sympathetically rebacked, label to upper cover with manuscript annotations, oblong folio.

Photographs include portraits of various officers, many with names captioned in ink; a group portrait of ‘G[overnor] G[eneral]’s Camp’, and below it a group shot of Col. Yule, Major Jones, Mr. Walters, Captain Stanley, Captain Baring, Captain Roberts V.C., Captain Hills V.C. and Sir E. Campbell Bart’, the latter attributed to Jean Baptiste Oscar Mallitte; a portrait of Lady Canning taken c.1861 by Josiah Rowe (British, c. 1809-1874); some Indian landscapes, such as the bridge over

Hindon River, Ghaziabad; stock photographs by Samuel Bourne of Government House, Calcutta; photographs by Clarence Comyn Taylor (1830-1879) of Maharaj Dhiraj Surendra Bikram Sah, King of Nepal (ruled 1846-1881); photographs of the family of Henry Ambrose Oldfield, doctor at the British Residency in Kathmandu, Nepal (1850-1863); portraits of Maharajah Jang Bahadur CB, Prime Minister & Commander-in-chief, Nepal; Raj Guru, the chief Hindu priest of Nepal and a brother of Jang Bahadur; and photographs from Kandahar, Afghanistan, amongst others.

Artworks include four large watercolours by Henry Ambrose Oldfield, including ‘A Gateway of Palace, Kathmandhoo,’ The Palace at Kathmandu’, ‘Interior of principal temple, Pashputty Nepal [sic, Pashupatinath]’ and ‘Swayambhunath Temple’; a group of 8 pencil landscape sketches in the style of Oldfield, but one is captioned “(Rajman)”, a likely attribution to the local artist from Patan, one of the first painters from Nepal to incorporate Western art practices, Rajman Singh Chitrakar (1797-1865); a “Company School” watercolour of a bison, also possibly by Rajman.

Maharana Sarup Singh of Udaipur Workshop of Tara Chand, likely by Parasuram Mewar, Udaipur, India, circa 1860

Gouache heightened with gold on paper

Image: 16 1/2 x 12 3/4 in. (41.9 x 32.4 cm.)

Folio: 18 3/4 x 14 1/2 in. (47.6 x 36.8 cm.)

Provenance:

Acquired in New York in the 1980s, by repute.

Maharana Sarup Singh (r. 1842-1861) of Udaipur stands nimbate in formal royal profile, holding a small betel nut or paan against a flat green ground with shrunken floral clusters at the forefront. He is dressed in a pleated, stark white muslin jama and transparent shirt with a matching orange and gold patka and pagri, adorned with aigrettes, pearls, gold and jewels. The Rana holds an upright sheathed sword and is posed regally in profile, like so many Rajput and Mughal nobles who preceded him. A katar can be seen tucked into his waistband.

Tara Chand was the principal master of the royal Udaipur painting workshops during the reign of Sarup Singh. Although Tara’s work was inherently conservative, recalling works from the ateliers of the earlier Maharanas of the eighteenth century, he introduced a new color palette, which includes some aniline colors brought in from Europe. These colors produced the arresting greens, oranges and teals that cannot be overlooked within the composition—the blue-green that fills the Rana’s golden nimbus stands in striking contrast with the emerald background. This blue-green halo color seems to have begun later in the activity of Tara’s workshop and becomes notably pronounced in paintings attributable to his colleague Parasuram (ca. 1860).

For comparison, refer to a similar painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, object number 2019.123.

H. H. The Nizam’s Daughter, 1890s

Image: 10 x 12 in. (25.4 x 30.48 cm.)

Framed: 15 1/2 x 17 in. (39.4 x 43.2 cm.)

Edition: 3/15

Exhibited: The Art Indus, New Delhi, India.