LOST AND FOUND

ARCHITECTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS

THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS, SCHOOLS OF ARCHITECTURE DESIGN AND CONSERVATION

THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS, SCHOOLS OF ARCHITECTURE DESIGN AND CONSERVATION

THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS, SCHOOLS OF ARCHITECTURE DESIGN AND CONSERVATION

Lost and Found

Architectural Transformations in Architecture

Edited and designed by Christoffer Harlang in collaboration with Charlie Steenberg, Nicolai Bo Andersen and Victor Boye Julebäk

English translation: Culturebites

Images © the authors

Photographs © the authors

Texts © the authors

Yearbook 2010-2012 Transformation

The Department for Cultural Heritage, Transformation & Conservation

The Royal Danish Academy, School of Architecture

Digital edition 2025, first published in print in 2013

This publication is published with generous support from The Dreyer Foundation. With this book we The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation wish you a happy New Year 2013.

© 2013 Transformation

Philip de Langes Allé 10 DK - 1435 Copenhagen www.kglakademi.dk

ISBN 978-87-7830-918-1

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation

The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation

Lene Dammand Lund, Rector

Today, the educational programmes in architecture, design and conservation are high-focus areas with a clear mandate to contribute to the development of our society. We have therefore decided to use our New Year’s publications to highlight the programmes that KADK has to offer. We begin with a topic that is high on our own agenda as well as the agenda of the Danish government and the rest of the world: transformation.

Around the world, we are facing certain challenges in maintaining our cultural heritage and updating its energy profile. We also need to integrate it into the present, which means embracing our cultural heritage as a basis for architectural design that is identity-forming today.

In quantitative terms, new construction accounts for only 1 percent of the total building mass, while more than 40 percent of Denmark’s total energy consumption goes to heating buildings. Thus, the bulk of future architectural assignments will lie within this field, which involves both building technology and talented design work. The industry has a demand for graduates specializing in this field, and KADK is happy to lead the way with examples illustrating how these significant and relevant challenges can be met. We are currently in the process of optimizing our organization and wish to strengthen our cooperation with engineers, building clients and the construction industry at large.

With this New Year’s publication, we offer a glimpse into KADK’s master’s programme in Architectural Heritage, Transformation and Conservation. The programme is still relatively new but nevertheless very popular. We hope that you will find this condensed look at one of KADK’s many fascinating fields rewarding. Last, but not least, we wish you a Happy New Year!

Christoffer Harlang

‘The voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.’ Marcel Proust

The world is changing and so are we. Along the way, there are things which will disappear from our lives forever; things which we will never see again. We may miss them, but this will not always be the case –the loss could feel like a relief. We may be replacing it with something better. But some things may reappear. Resurrected, perhaps altered in some way, transformed or damaged; it may become part of our lives once again. Perhaps through a stroke of fortune or due to a certain resilience or perseverance from it or ourselves; some things are destined to stay with us for a long time. As faithful moments of our everyday life or consistent characters of our culture amidst this dynamic world and it’s ever changing inhabitants.

A boy sits within the ruins of a bookshop following an air bombing of London on the 8th October 1940. He is reading a book entitled: “The History of London”. The world has gone to pieces around him and he is searching for an understanding which will bring it back together, to give it some meaning. It is a powerful photograph, both through its narrative of loss but also as a positive statement of our civilisation’s resilience and vitality. Whilst the development of modern architecture in the last century was a product of industrialism’s new technologies, the same era spawned new restoration and conservation strategies following the extensive damage inflicted on European cites during two world wars. The devastation required a re-evaluation, re-interpretation and action. This emerging Eu-

rope saw its memory, narrative and identity under constant threat. Today, we live within a fully realised Europe with most of the building being performed on existing structures and buildings. At the same time, a number of very serious challenges in the form of climate changes and imbalance have far-reaching implications on the way we live. The global challenge of restoring ecological balance will require a radical restructuring of our outlook and we will need to develop new strategies, tools and concepts if we are to continue the way we are. In a time where the concept of beauty is reduced to the idyllic and the pleasurable, and where the sole reason for beauty is determined through the framework of our market economy, we have seen a deprivation of our physical world. In recent decades we have lost a certain sensibility towards the qualitative nuances of our physical surroundings and forgotten a sense of the context and prestige given to us by past generations. The knowledge we need to survive is slowly slipping through our fingers. However, we also have a unique historical opportunity for change, to begin seeing the ethical and the aesthetic as two sides of the same coin in a new specific, contextual and sustainable architectural approach. Just like with the origins of the modern era, the challenges we face today are massive but also fascinating and inspirational. We need to develop new eyes.

This book is about how we at the School of Architecture have been working with transformations in architecture from 2010 to 2012. It is an anthology containing the collective efforts of our students, teachers and researchers on the Master’s programme Cultural Heritage, Transformation and Restoration. We have formulated a method which we strongly

believe in and which reflects our stance. It can be understood by itself or through the projects designed by our students. It reveals itself through a number of ideas, thoughts and realisations made by our colleagues in the department either in a constructed form, in project visions, sketches or in the form of texts.

We decided to name this book Lost & Found because we are seeking a familiarity with approaches and narratives which may not necessarily be new, but may have been forgotten. Methods and techniques, insights and knowledge which have been missing for some time or which have evaded the attention of architects; the use of space, forms and textual effects which have been ignored or overlooked in recent years. This is our attempt to identify some of these aspects once again. Not for sentimental reasons or as compulsory reading or for entertaining historical value, but for inspiration; as a refreshing perspective to challenge the current and future changes in our physical surroundings in a more qualified manner. But also as a vital consideration when we must repair, restore or transform sites of cultural heritage. We have also developed new specific methods and perspectives that can operationalise cultural heritage, both ideologically and physically. These methods are based on a set of declarations (ethical codes).

We aim to create a professional environment where students, researchers and teachers interact which typifies our commitment to harnessing a mutual synergy between a well-functioning educational environment and a dynamic, international research department.

In particular, issues such as time, sustainability, authenticity and materiality fascinate us as well as theories of the innate human sensibilities of the spaces and objects we live amongst. There are three main subject fields which we have identified as of particular importance, namely, the phenomenological perspective, the technical perspective and finally the historical perspective. We believe that this tripartite framework of understanding creates an inspirational space which has developed naturally from everything we have performed, both in practice, in teaching and through our research. We strive to deliver teaching and research that are closely linked and which are based on sound theoretical development and practice-oriented research and developmental work.

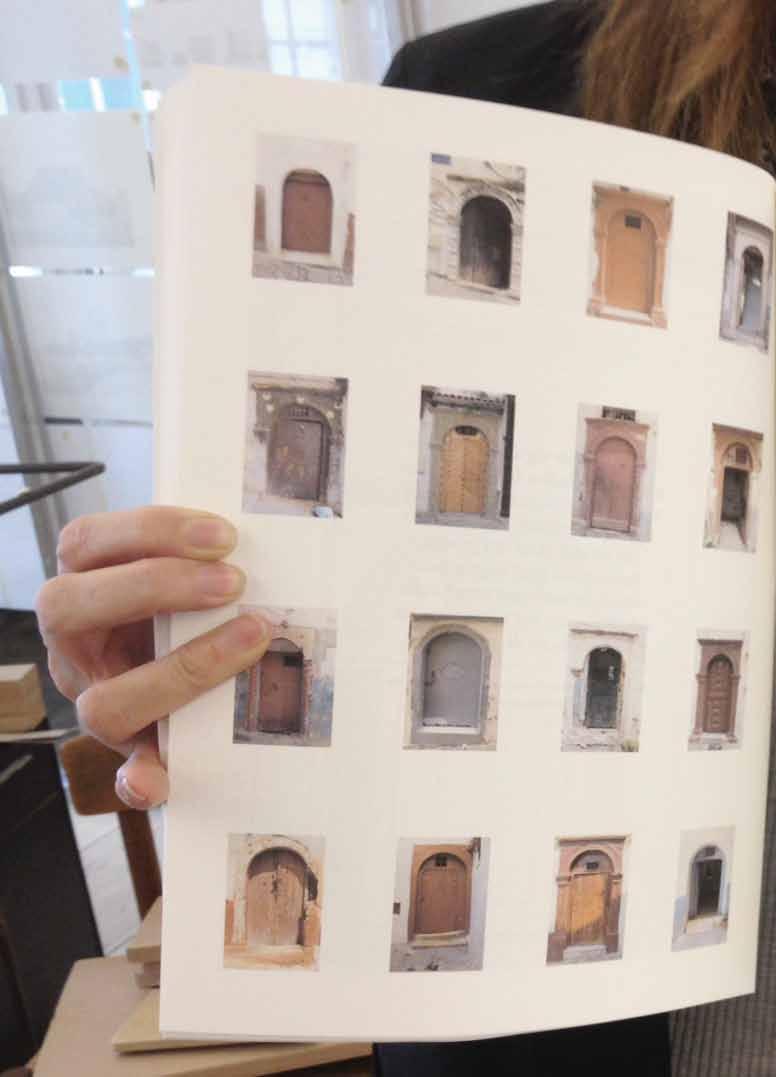

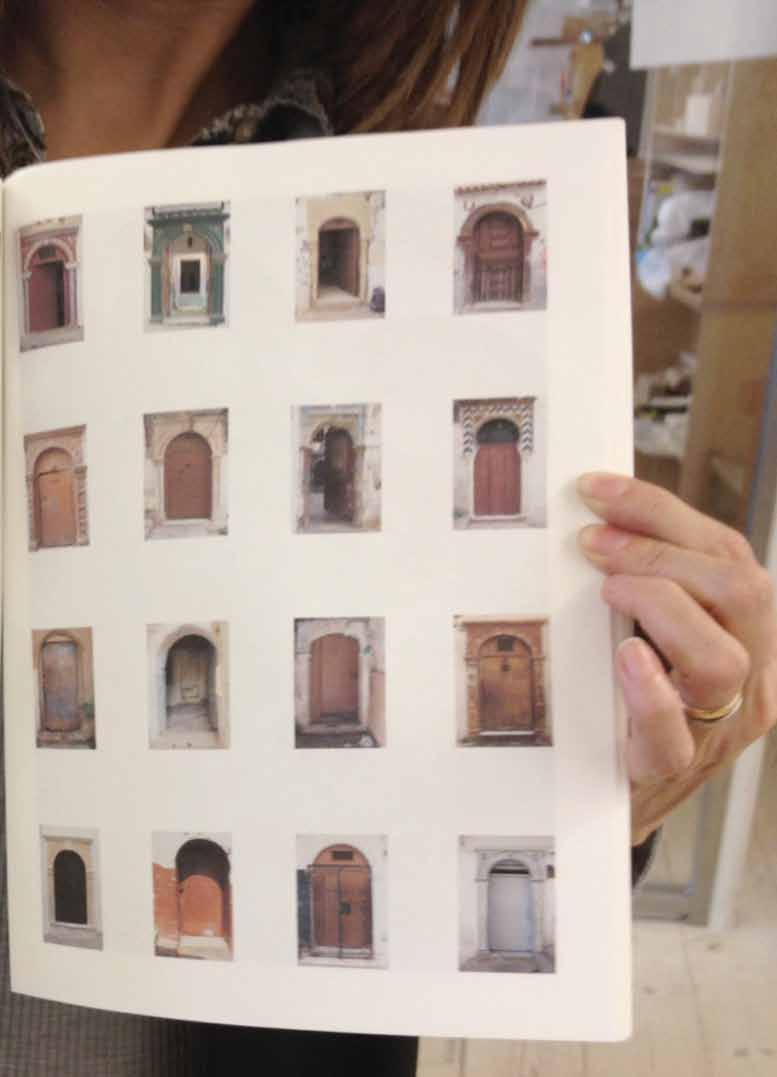

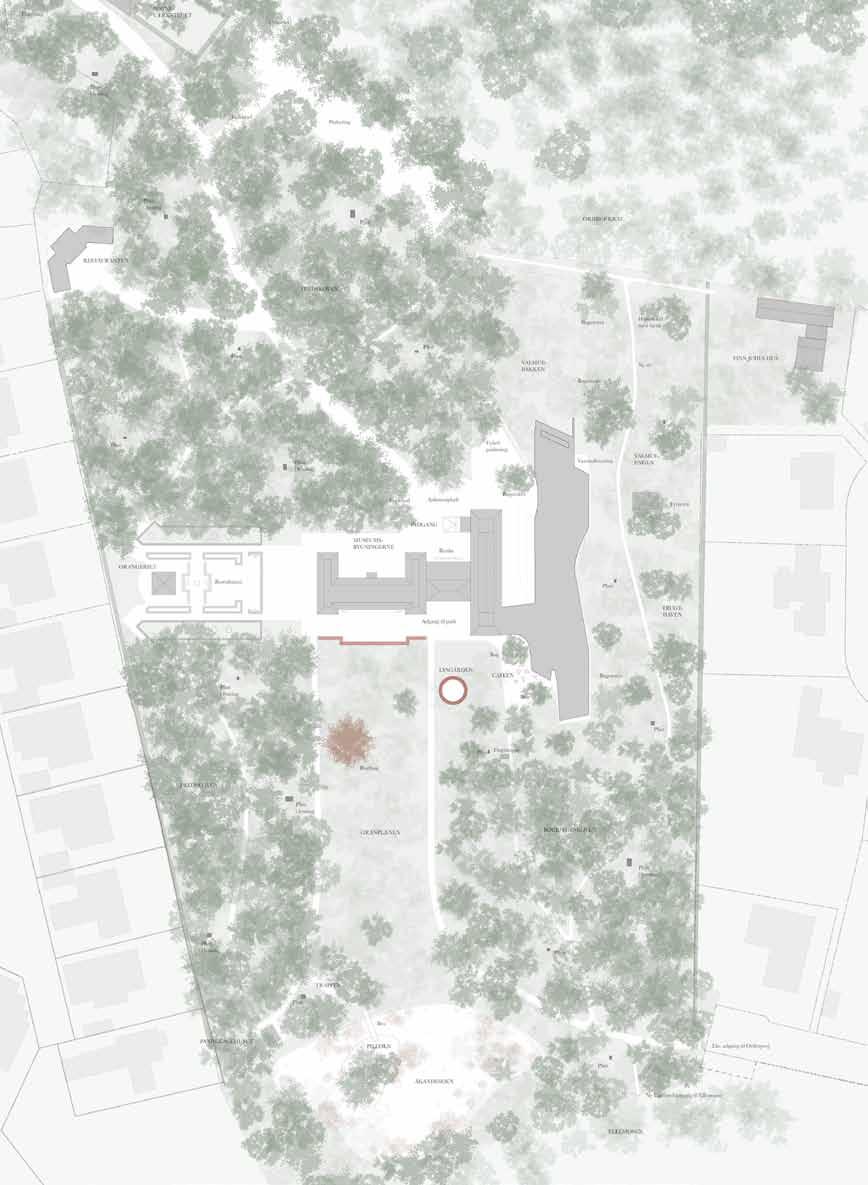

But our overall goal is to educate architects who can contribute to professional cultural heritage, building conservation, transformation and management. The case studies considered are mostly Danish but we also work with cases in the other Scandinavian nations and in this book we have examples from Greenland, Mozambique, Marrakesh, Berlin, London and New York.

We have many people to thank for their contribution to the formulation and implementation of this project. An absolutely essential factor has been the inspirational dialogue we have had with several architectural colleagues from Denmark, England, Sweden and Switzerland. We have found huge inspiration from their contributions to a rethinking of aesthetic ideals and within the transformation of cultural heritage. However, this book is first and foremost a celebration of our gifted students – thank you for your dedication, time and of course, your talent!

Curriculum

Since 2009, this field has formally been described as an area within the science of architecture that focusses on architecture’s concept, effect and culture. The activities within the scope of this field are aimed at mapping, interpreting, integrating and further developing architecture as a central, meaningful factor in the spatial organisation of society. As a part of the history of civilisation, architecture is considered to be a manifestation of heritage to advance and become integrated into the present time as an artistic expression of society’s core values.

Originally, this field came under the general heading of ‘restoration’, as the original focus was on developing knowledge and knowhow in recreating and restoring a building to its original state. At that time, the importance of the field lay in developing structural archaeological knowledge and competencies, historic insight and understanding of historic techniques and materials – all with the aim of re-introducing these to contemporary architectural practice.

The modern English term given to this field is ‘Conservation and Transformation’. Here, conservation refers to the processes used in restoring a building to its original technical and aesthetic condition. Transformation refers to the processes that advance a building by adding a certain amount of technical and aesthetic content.

As a result of the growing scope of the field in practice, the current Danish term for the field translates as ’Cultural Heritage, Transformation and Restoration’. This modern title better covers a field that spans a wide range of competencies concerned with restoring the core cultural values passed down by architectural disciplines dealing with the transformation of historic buildings. In contemporary architectural heritage projects, it is more often the rule than the exception that these different concepts overlap. Whereas the 1997 restoration of C. F. Hansen’s Christiansborg Slotskirke was primarily a restoration (with the key focus on recreating the original), the rebuilding of Frederik VIII’s palace from 1755 represents such a programmatic and technical complexity that it is best described as a transformation.

The Bygningskultur 2015 research project

The primary aim of this project is to coordinate all existing knowledge and establish a new knowledge base within the field. This will be achieved by submitting instructional analyses, methods and examples that can qualify heritage management, preservation and transformation. The research is oriented towards various research disciplines, as well as registered data collection, theoretical knowledge development, and practice-oriented research and development work. The core objective is to source knowledge and acknowledgement by using both a scientific, data-based approach as well as an architectural proposition-based approach.

Consequently, a prime objective is to link the cultural preservation elements and the culture creating elements by reviving the special research culture that previously (with Kaare Klint’s furniture school and Kay Fisker’s living-space laboratory) nourished the development of a specialised architectural research culture in Denmark. The research project combines the methodology of scientific tradition with a phenomenological, hermeneutic approach. Constructional archaeology, building history, architectural history and construction technology are all incorporated. Similarly, key works on authenticity, the body’s phenomenology and theories of human

spatial experience and its artefacts all constitute elements in the project’s methodical and theoretical foundation.

The subject matter is approached by means of three different aspects: phenomenological, technical and historical. This three-fold approach is directly connected to the research methodology of Professor Andrea Deplazes at ETH, which is, for example, described in the publication Constructing Architecture, Materials Processes Structures.

The Master’s programme in Cultural Heritage, Transformation and Restoration has been designed to complement the activities of the Bygningskultur 2015 research unit. Focus, subject matter and assignment themes are coordinated in an academic environment where students, researchers and teachers all interact. The aim is to create a reciprocal synergy between a well-functioning study environment and a new, dynamic, research environment – an environment that is highly relevant to the real world. Experience from this is forwarded into discussions of how the interaction between study and research at Royal Academy can be improved. Useful information concerning how project teaching at Royal Academy can be developed alongside research in integrated research/study environments (beneficial to both parts) will be collected.

The Master’s degree in Cultural Heritage, Transformation and Restoration (CTR) deals specifically with the transformation and restoration of architecture by focusing on historic understanding, technical insight and analytical competency.

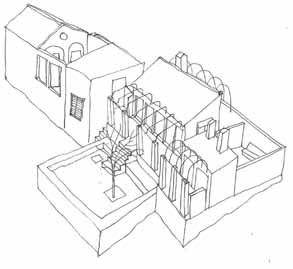

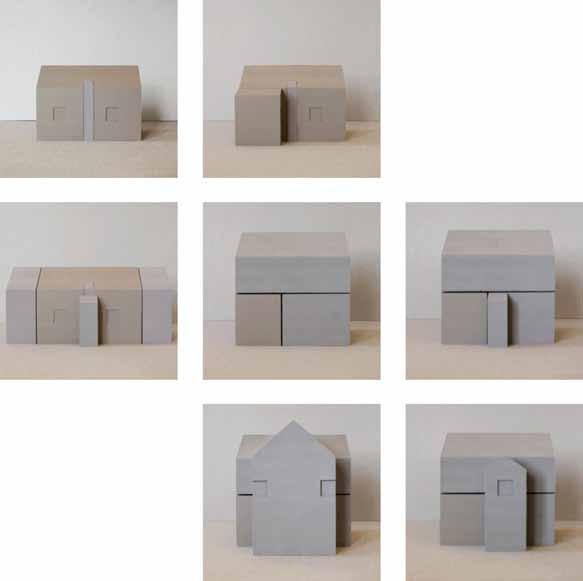

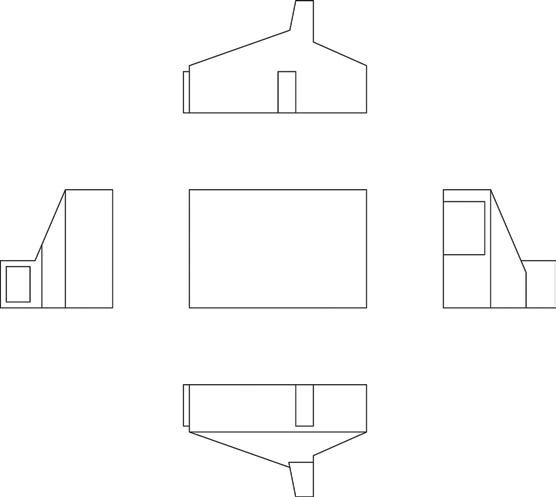

The CTR programme works with transformation in its widest sense. Destruction, reconstruction, repair, transformation and addition are interventions that together cover an ungraduated scale, dealing both with classical restoration and with the ability to build a new building in an existing context. The objective is to instil an understanding of cultural heritage and restoration – not as a limited, independent field, but as a naturally integrated part of architectural practice, where an interest to work with culturally important, location-specific and material-focussed elements is key.

The historic element will be seen as a living and inspirational resource – a source of challenge and refinement to a contemporary architect, rather than an impediment.

The subject matter represents the architectural challenges between continuity and change, between architectural work and the dynamics of society, which has materialised in many current projects restoring and transforming buildings and towns. The department deals with specific competencies in the areas of building culture, restoration, transformation, architectural theory, architectural history and building analysis.

Academic characteristics

The teaching concentrates on how spatial structuring and architectural meaningfulness can be achieved through a culturally founded mastery of a building’s technical reality. We work with architectonic effects that are the result of a process where a mental content is expressed through a specific technical solution. That which drives an architectonic work forward is a method whereby complex relations,

alternately conscious and unconscious, are synthesised to a level of order and entirety that expresses an emotional content. We view the concept of sympathetic insight to be a fundamental element in this process. The sympathetic insight of the architect spans both humane empathy as well as the ability to be able to put him- or herself into a complexity of technical, social, psychological and functional relations. A sympathetic insight into cultural heritage, into the historical given, is seen as a prerequisite for an identity-creating architectural design as part of the programme’s Master’s dissertation.

That which makes restoration and transformation special is the fact that the architect, prior to commencing the work of providing form and programme, requires exact knowledge and sensitive understanding for the existing structures identity, history and technical construction. The Master’s programme introduces and provides competencies within specific areas of knowledge and methods that are relevant to achieve this aim, i.e. building analysis and evaluation, as well instruction in historic construction techniques and material use. Students gain a familiarity with the fundamental issues, theories and cultures in the field of restoration and transformation.

The two-year Master’s programme focusses on restoration and transformation in the field of architecture, encompassing architectural concept, effect and historical culture.

The emphasis of the course will be on mapping, interpreting, integrating and, not least, developing architecture as a central, meaningful factor in the spatial organisation of society. This means that architecture, as a key and integrated part of the history of civilisation, is viewed as a cultural heritage, to which we must relate. On the one hand, this heritage must be maintained and secured against being lost, yet, on the other hand, it needs to advance and be integrated into the present time as an artistic expression of society’s core values.

The aim of the degree course is to educate candidates who can practice, manage and develop this field to its broadest. This will be achieved by training students to take a reflective standpoint towards certain issues and relevant themes that crave and inspire contemporary consideration. Through internships and workshops, the students will become familiar with the practices and conditions of the field.

Interpretive and knowledge-based elements form a key part of the programme curriculum, as does active encouraging of proposals and solutions. The knowledge-based aspect of the curriculum includes constructional archaeological documentation in the form of data collection and mapping competencies, which will be combined as required in the restoration procedure.

The major elements for the basis of the project are cultural historical, architectural historical and topological studies; to a lesser extent, antiquarian studies will be included. The latter covers destructive studies and studies of constructive conditions, colour clarification, interpretation of profiles, studying chronology and key historical periods.

Restoration and transformation does not mean carte blanche access to old buildings; the work must be based upon a foundation and mapping of preservation value, architectural analysis and a clear artistic stance.

The Master’s programme provides knowledge of historical building techniques, architectural history and restoration theory. It also engenders competencies in the field of designing architectural responses that encapsulate culturally founded conditions that are relevant to the building.

The programme instils competencies in architectural analysis, valuation and formulation, as well as in implantation of architectonic strategy in relation to existing structures, including listed, preservation-worthy and function-depleted buildings.

The curriculum has been designed to incorporate a mix of short, intense draft assignments and longer-term, in-depth projects. In close coordination with these, the special fundamental principles taught will provide a relevant and inspirational technical, historical and theoretical knowledge, as well as a specific, practical tool-base as a foundation for the project work.

We work in the area spanning the fields of history, technology and phenomenology. Through lectures and field trips, the particular fundamental principles will cover much of the historical and technical elements, whereas studio work will primarily focus on the phenomenological aspects. A core principle is that the historical, the technical and the phenomenological aspects should not be considered separate entities, but rather relevant and integrated aspects of the working process. This means that the phenomenological aspect will always be addressed when working with the historical and technical aspects, just as these will be integrated with work focussed on the phenomenological aspects.

The intention is for the teaching to support the student’s independent and personal architectonic development with the aid of an artistic quest based in practical ability and theoretical knowledge. The teaching alternates between being specific/demonstrative and abstract/inspirational.

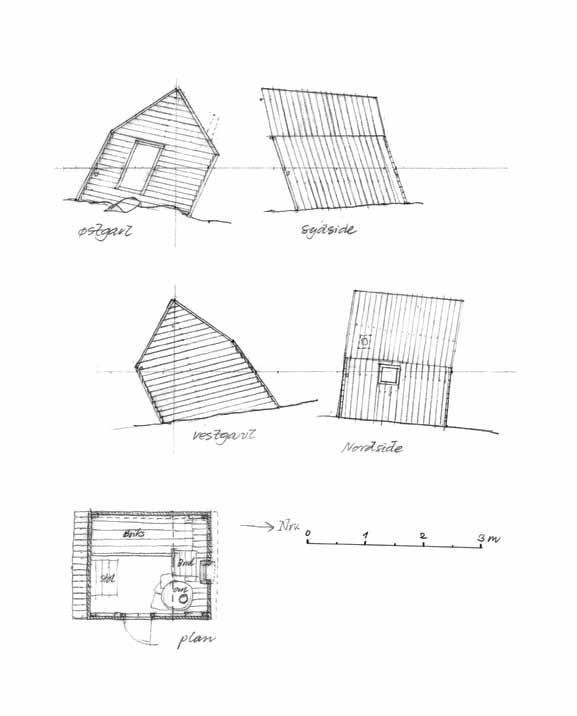

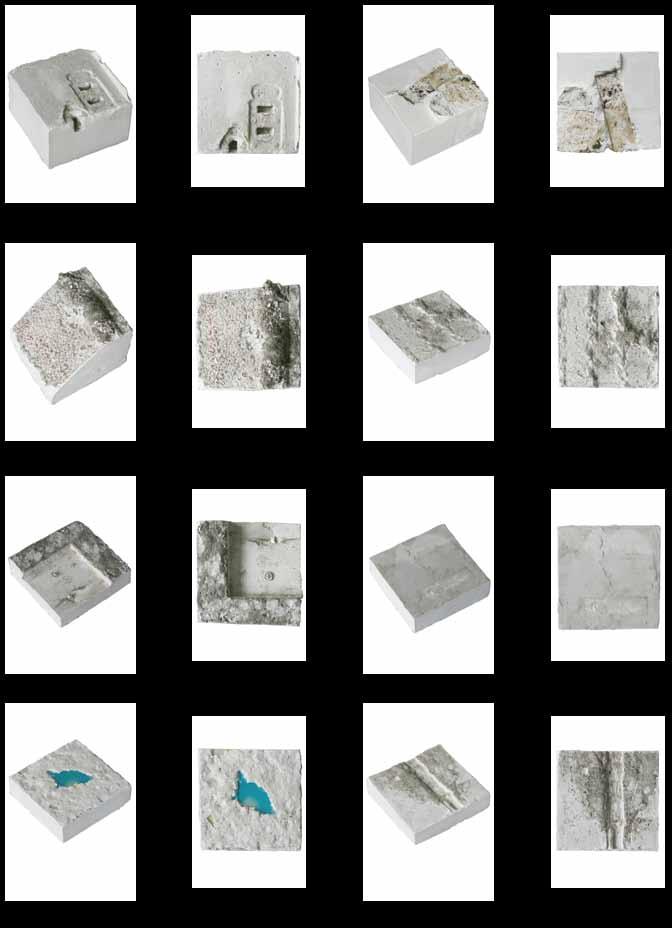

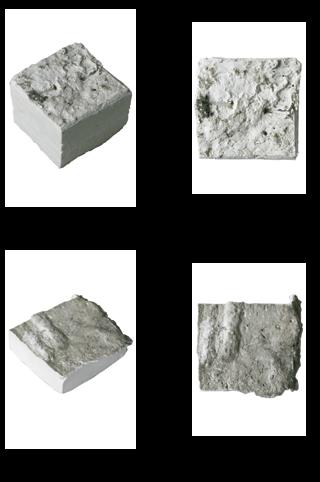

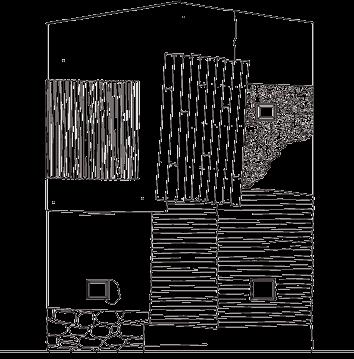

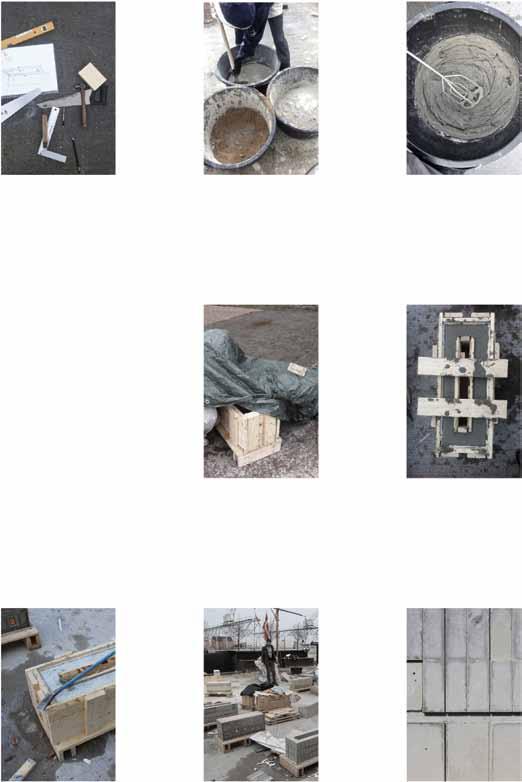

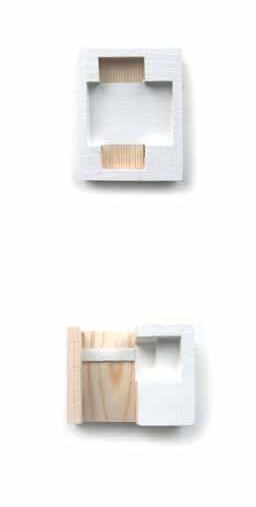

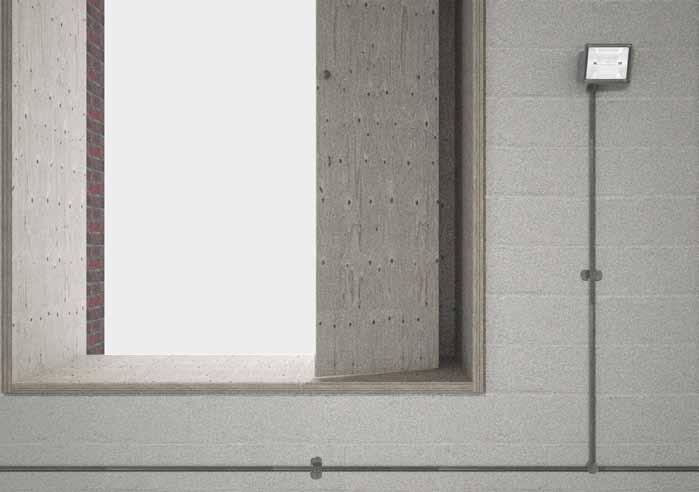

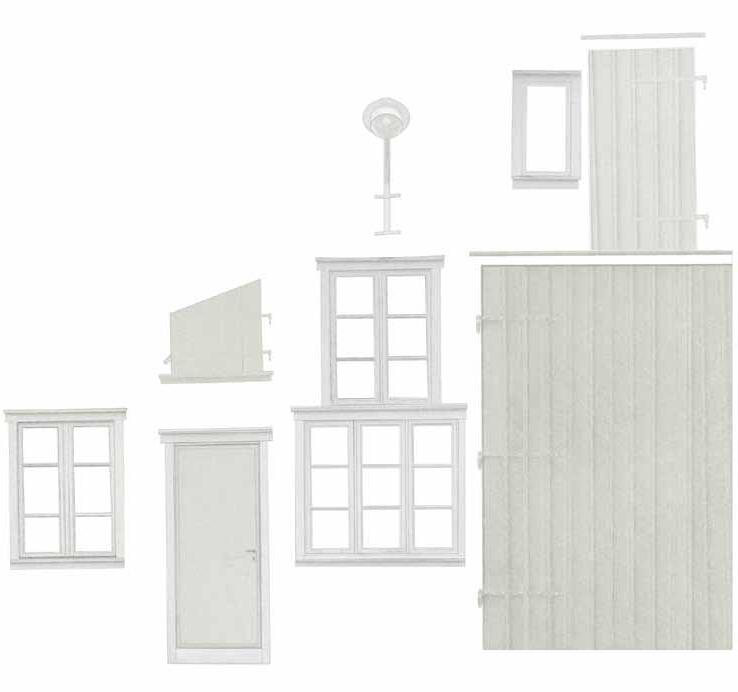

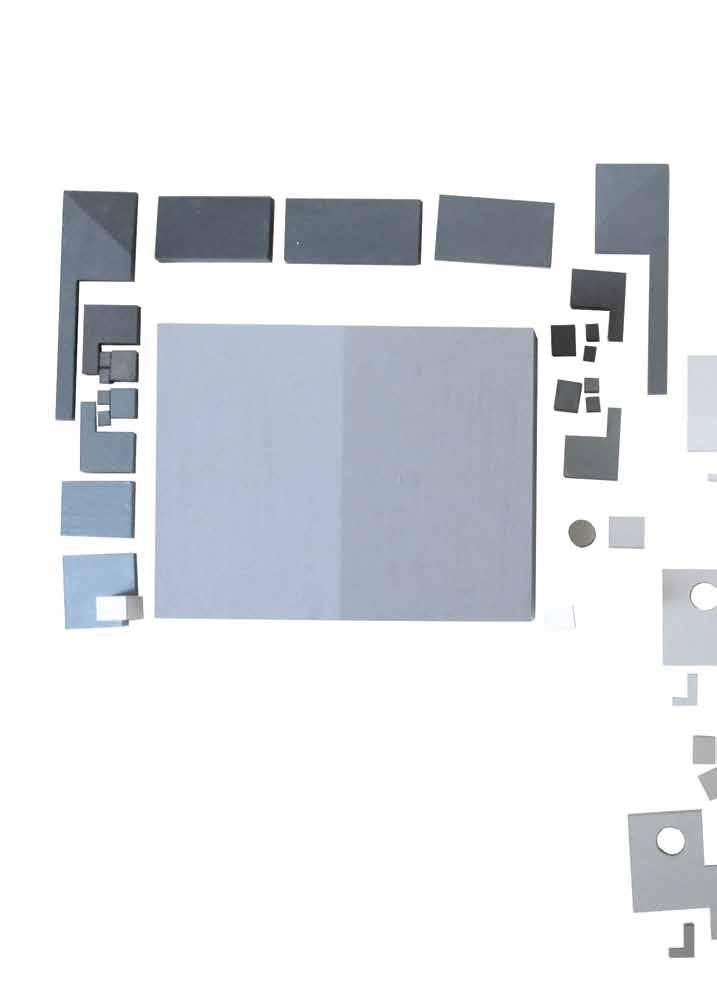

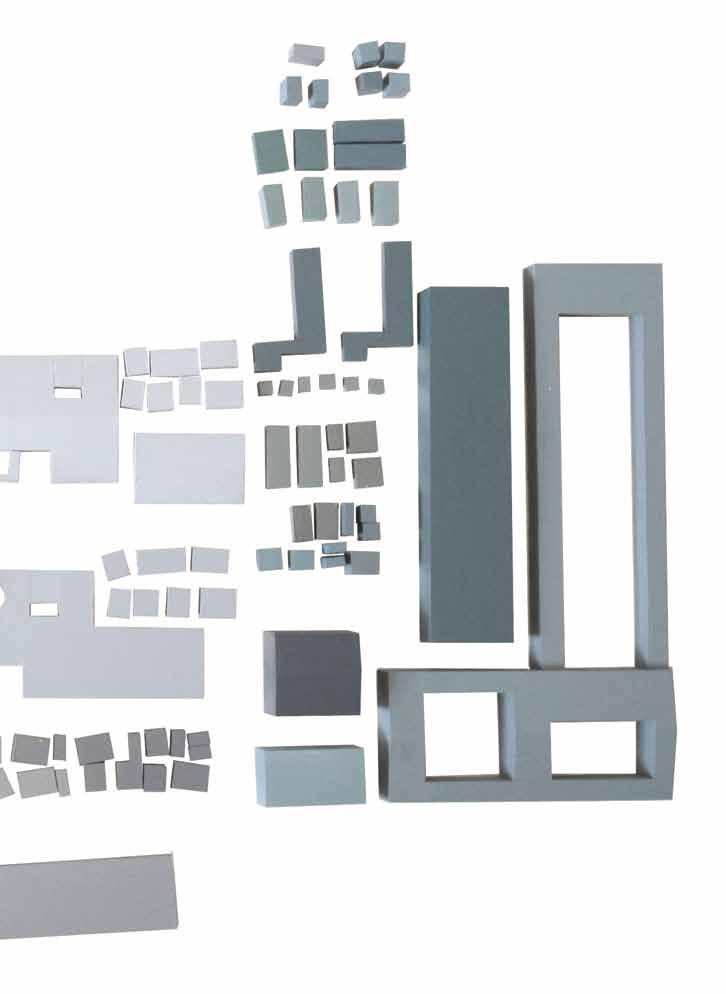

Tectonics 1, 2 & 3 provides in-depth study of three fundamental construction methods that are relevant in both a historic and a contemporary context: joining, stacking and founding. The cultural studies within the programme form the basis for practicing skills of mastering the technical and aesthetic construction of parts of a building. Tectonics 1 – joining – studies carpentry construction, both past and present, and provides insight and experience in understanding the technical and aesthetic possibilities in wood. Tectonics 2 – stacking – studies the architectonic possibilities within the modular stone/brick. And Tectonics 3 – founding – focusses on the cast form and material used for founding.

In VærkSted [WorkShop], we work with the thorough study of a highly designed and thought-out building, alternating between classicism and modernism. We will learn through drawings and photographs, producing a sense-based and a documentary story of the building. The standard surveying/measuring techniques will focus on the subject’s geometric relationships, and here the development of tools to describe the spatial and sensory qualities is necessary. The assignment will provide insight into building culture and construction history, and it will develop the students’ abilities to deal with new registration and representation forms as a foundation for the following assignment in Transformation & Restoration. In

VærkSted, the correlation between a technical solution and its architectonic and phenomenological effect will be studied. Several representational tools and techniques will be studied in order to pinpoint and maintain the sensory qualities that a building exudes.

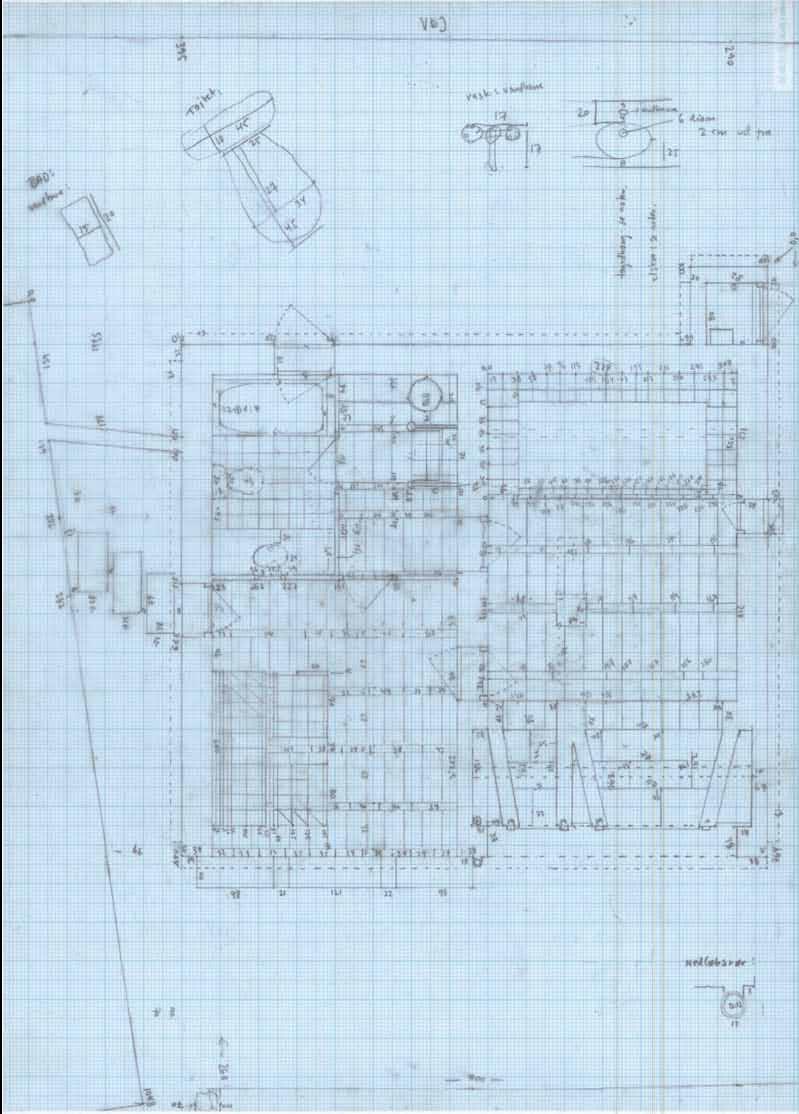

Transformation & Restoration 1, 2 & 3 are 12-week term assignments that focus on specific issues with restoration and transformation in the existing urban and building structures. On the basis of measurements/surveys and studies of existing buildings’ spatial, material and technical values, skills and competences will be developed in the areas of valuation, programming, formulating restoration conditions and project proposals. The assignments will vary between the themes function-depleted buildings, urban densification and addition.

Building analysis and valuation make up a specific foundation discipline, based on surveying/measuring and registration. This provides a unique opportunity for students to attain spatial comprehension as well as in-depth knowledge of a building’s aesthetic and technical construction. A correlation arises between the physical reality and the level of abstraction posed within the drawing, providing increased understanding during the surveying/measuring process as well as during the project development process later on. Through the study of valuation, students gain a nuanced understanding of an existing building, forming the basis for selecting an architectonic direction in the project section of the programme, including programming. The normative designation of un-losable, materials, parts of the building, room divisions etc. forms the basis of formulation an individual and personal approach to restoration, with argumentation for the architectonic strategy being provided. Registering and measuring/surveying work will be undertaken with traditional tool as well as using the latest computer technology. Lectures and practical work.

Historic construction techniques and materials studies represents another fundamental discipline, familiarising the students with historic building materials, building constructions and trades methods. As part of the buildings overall unity, these components play a role when making decisions regarding registration, valuing, programming and project engineering the building culture. Furthermore, historic construction techniques encompasses a learning that can inform about aesthetic and technical design and form of brand new buildings. Because of this, an insight into historical building techniques and an understand ding of materials is not something restricted to architects working with heritage, transformation and restoration, but should be an area studied by all architect students. Lectures, practical work and field trips.

The theory and history of restorative architecture is another foundation discipline that provides a nuanced understanding of restoration attitudes and practices through history. This forms a foundation for familiarity with construction culture, understood as both a par of and an expression of dynamic and complex contexts. The various ways that we have related to and worked on existing buildings architecturally constitutes a significant key to interpreting and understanding surviving buildings. Work with restorative architecture theory and history supports architectonic practice, which is characterised by a view of existing architecture as an interaction between building culture and social culture. The seminal theories

and trains of aesthetic thinking – elemental for the leading practitioners in the field from the 1850s to today – will be examined, including the Venice Charter and the Athens Charter. In practical work, insight will be given into conditions governing the work carried out by project engineers, project administrators and owners of restoration and transformation projects. Visits to architectural studios/practices, administrators, building sites and suppliers. Lectures and practical work based upon independent compendium studies.

The final assignment marks the end of the Master’s programme, combining all of the areas studied throughout the course. Registration, analysis and valuation; programming and proposal making; and development of project proposals that include all aspects covered in the field of CTR: reconstruction, repair, transformation and addition.

1. Prior to our architectural intervention, we will procure an analysis of the pre-existing architectural values, character, tonality and composition.

2. We will refrain from unnecessary contrivance and will commit instead to using solutions that have proven their technical, aesthetic and phenomenological durability.

3. We will develop new solutions when existing solutions prove insufficient or when we have procured conclusive advances able to provide an architectural design of equal merit to that which exists.

4. By using solutions equal in merit to the existing architecture, we will ensure that every new intervention and all new components and details be expressed in keeping with the sense of architectural unity.

5. We will design the architecture in such a way that it does not solicit undue attention.

6. Our architectural solutions will be characterised by a depth of detail aimed at providing a sensory experience that generates both a feeling of belonging to the world and a feeling of fitting into the world within those who view the architecture.

7. The beauty of our architecture will enhance with the years.

8. By using durable and intelligent solutions, our architecture will engender reciprocity between aesthetic thinking and sustainable responsibility.

9. Our architecture will acknowledge the fact that we orient ourselves through the world by means of our senses, and it will appeal to our senses of sight, sound, touch and smell.

10. Our architecture will inspire a dignified and humanitarian meeting between people.

LOST AND FOUND

CHRISTOFFER HARLANG

When exactly did architecture begin? The depiction of the beginnings of architecture1 given by Roman architectural theorist Vitruvius, who lived around 25 BCE, is not only among the earliest we know, but also among the most beautiful. According to Vitruvius, ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� the structures they created said something about who they were, what they were capable of and what they dreamed of. This is how architecture originated over 10,000 years ago. According to Vitruvius’s account, all architecture which has since and which will ever come into being owes a debt to these humble beginnings and shares certain rudimentary characteristics, namely that the creation of architecture is inherently founded in a reciprocity between structure and statement, between purpose and expression2

Architecture is called the heaviest of the arts; it is called this because in its substance it is so extensive that it takes a long time to build it and a long time to break it down. The building works left behind by previous civilisations are therefore the most constant and lasting statements we have about these bygone epochs. When we learn to read these buildings, we ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� them. Architecture history can be read in two ways: partly as a chronological organisation of the cultural values within different eras’ buildings, and partly as a series condensed architectural insights that speaks directly to a contemporary audience. The importance, or weight, of the architecture3 can be seen in the fact that it is architecture that writes the ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ Classicism, Modernism4

- SUBTRACTION AND ADDITION -

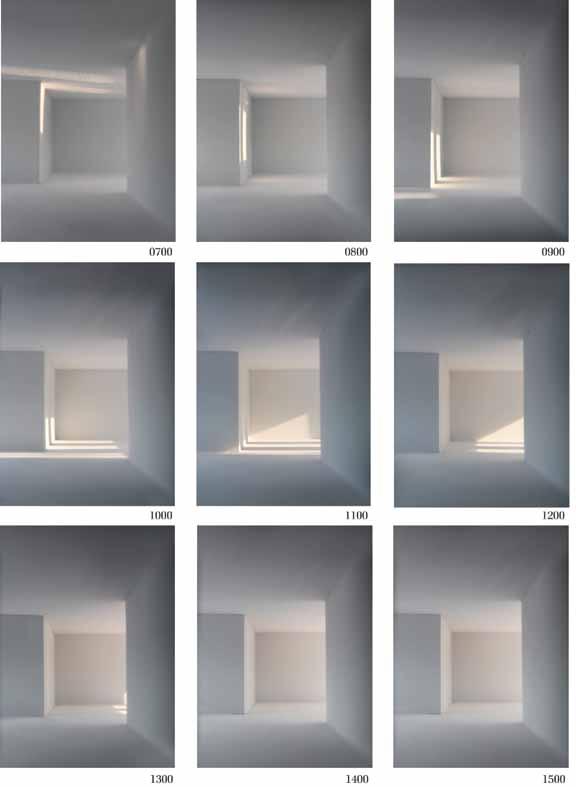

But Vitruvius’s depiction also has an indirect tale of two fundamental, but very different, principles, which humankind throughout history has used as a basis for forming ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ through subtraction of material: The other principle is forming a space by creating a construction, i.e. through the addition of material.

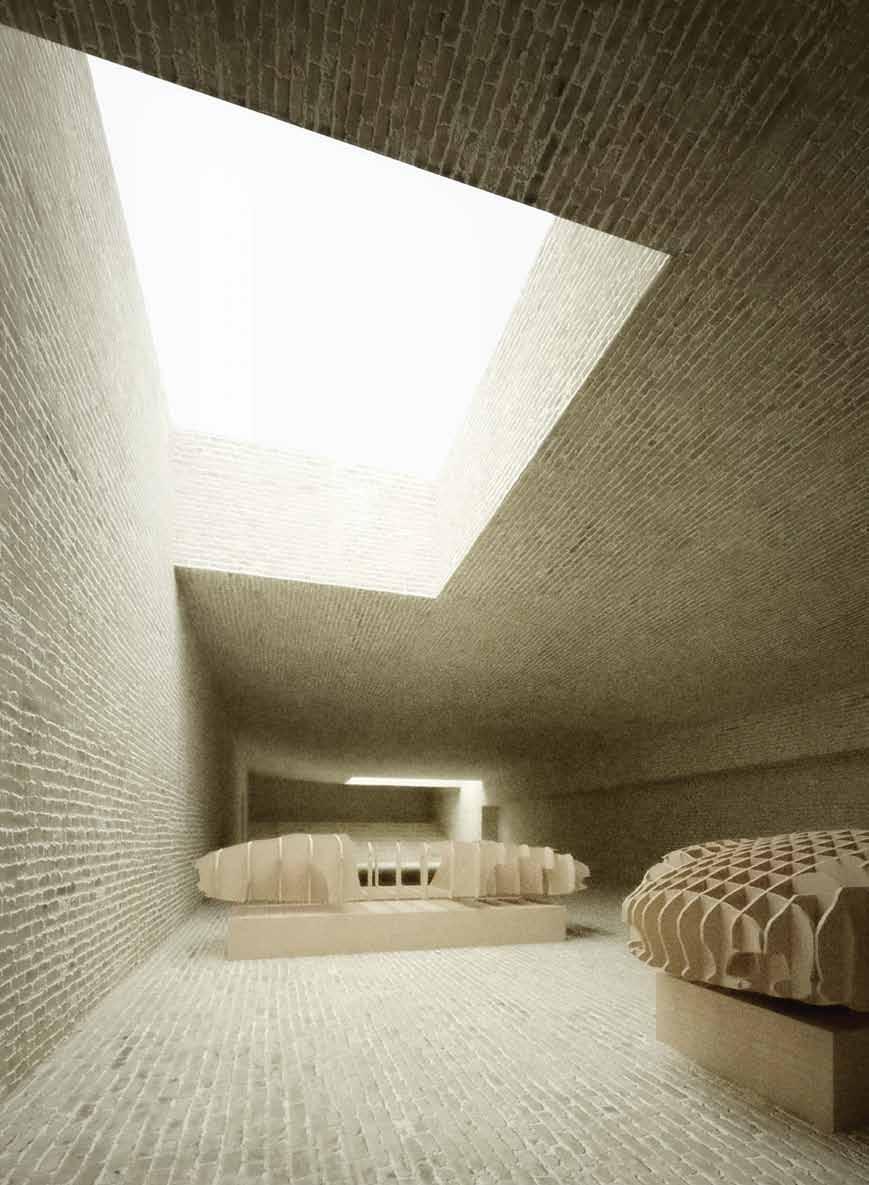

For space as erosion or excavation, the relationship is very different from that of the space as construction, even though we know that it is possible to create aesthetic effects in the constructed space that draw on the effects we know from the hollowed-out space. The space inside Sigurd Lewerentz’s church, Klippan, for example, is somewhat cave-like �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� standing walls and a roof, separating an outside and an inside. But the cave-like feeling of the space is something we feel very strongly, resulting from the special effect that occurs

window openings, and the sound of dripping water in an inner well.

Lewerentz’s church stands on a poured-concrete foundation; it has reddish-brown

inspiration from the choices used by Lewerentz in the church at Klippan when we designed an underground extension and associated gallery hall for Designmuseum Danmark in Copenhagen. Here, too, there is no difference in the material effects between the room’s

- RULES AND OBJECTIVES

prominent position in the supra- and sub-consciousness of the creators. From the dogmas

and tacit knowledge of modernity’s complex syntax, formulas and self-imposed rules, systems have survived which today form the basis of all architectural practice. Vitruvius’s triad Firmitas, Utilitas and Venustas (which dictate the relationship between strength, use and beauty) represents the most solid and fundamental framework of self-understanding for architects. The principle remains strong in the mind-sets of many an architect and forms

the basis for many contemporary architectural works. The hallmark of good architecture is therefore that it is well built, works well in use and is beautiful to behold.

- USE, LOCATION AND MATERIAL CHOICE -

Architecture is an applied art which, unlike the other related art forms such as sculpture ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� to a location, yet is shares a common feature of all other art, namely that it is restricted to ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

The ambition is not only to examine what the location can do for the building, but also �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

- THE PROCESS -

Architecture is generated through the architect’s ability to utilise mental empathy, and allow a technical mastery of the material to manifest itself in a work as artistic value. The artistic value is based on the architect’s ability to handle the formal laws and production �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������tonic expression. This relationship provides architecture with a substance that is experi�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� through its construction can be recognised and felt, evoking an emotional response within the viewer. Architecture is thus a concrete physical manifestation of non-physical concepts ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� produces a content that is very abstract.

Despite a certain amount of transparency in the premise that the ideas and thoughts of various bygone eras paved the way for the thoughts that today hold buildings together, there remains an element of mysticism or supernaturalism when we examine deeper the �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� the work itself.

When an artist puts his or her own understanding of what he or she creates, we call it ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� word from Aristotle’s Poetics and from Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music, which dealt with the

there is also a certain obscurity in the way it comes into being. The connection between art and magic appears clearly in the musician and physicist Peter Bastian7, who describes the musician’s performance as a resonance phenomenon between instrument and musician, who transcends consciousness by establishing a correlation between an inner sound

Bastian’s analytical approach to his art is based on a widespread trust in a purely scien�������������������������������������������������������������������8 (who has repeatedly focussed on the relationship between the conceptual and the instinctive), on the other

tor Henry Moore as saying that it is a mistake for an artist to talk or write about his or her work, as it releases tensions, which are necessary to the work. “By trying to express a goal with coherent logical precision, an artist can easily become a theorist whose actual work is only a trapped exhibition of the complexity of ideas that develop as a result of logic and words.9”

According to Juhani Pallasmaa, the architectural profession is today torn between the �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� blind faith in the necessity of theory and philosophical reference for creating meaningful

philosophical and conceptual proposals10.”

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ceptualisation; this is the view of architecture running parallel with artistic production, i.e. as two complementary approaches to architectural discourse. Theory and design inform ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ serious and precise thinking, thinking itself develops through the medium of architecture.

References:

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� of sociality interactivity. And as they continued to come together in greater and greater numbers, they understood themselves as gifted above the animals. Since they were not forced to walk with their faces bowed to the ground, but upright with eyes towards the ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� from green boughs, others dug caves into the mountain sides, and others copied swallow’s by creating shelters of mud and twigs. By observing other shelters and adding new details to their own, their constructions grew better and better as time progresses.”

Vitruvius

2. For a contiguous description of architectural history, see Fletcher, Banister. A History of Architecture. For a contiguous description of the development of modern architectural history, see Framton, K. Modern Architecture - a critical history, London 1992. �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Conrads, U. Programs and Manifestos on the 20th Century Architects.

4. For a chronological summary of the history of the development of room/space, see Marcusssen, L. Rummets arkitektur - arkitekturens rum. Copenhagen 2002 (DK).

5. See Kahn, L. Writings, lectures, interviews. Red. Latour, A. New York 1991. Fehn, S. The Poetry of the Line.

6. Alberti discusses the connection between musical intervals and architectural proportions. With reference to Pythagoras, he points out that “the intervals with which conformity sound affects our ear with beauty is exactly the same as those which please our eyes and minds ... We therefore extend forth our rules for harmonious relations from the musicians, ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ciples in the Age of Humanism. London 1952. p. 110. �����������������������������������������������������������

8. See Pallasmaa, L. Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. Edited by Dirckinck-Holmfeldt, K. et.all. At fortælle arkitektur. Copenhagen 2000 (DK). p. 84-99.

9. do, p.84.

10. do, p.85.

LOST AND FOUND

THE POWERS OF OBSERVATION

This paper investigates the role of building studies through drafting and measured survey as a means to acquire profound knowledge of the fundamental aesthetical principles of architecture. Through two historical examples it is shown how the study of the aesthetical conquests of the predecessors has been cardinal to the continuous genuine artistic progress of Danish architecture. A contemporary example demonstrates how drafting and measured survey today is still highly relevant in the artistic production and research. It is argued that the direct artistic encounter with the building culture brings about a certain embodied understanding of the aesthetics of architecture, invaluable in the further artistic production.

During a conversation about a sketch by Alvar Aalto, the British architectural theorist William Curtis has described the role of Aalto as an architectural cosmological seismograph. By this Curtis understands that Aalto’s remembrances of the works by Corbusier, the ruins of the Hadrian Villa, etc. are inadvertently projected through the intuitive sketching of the hand.

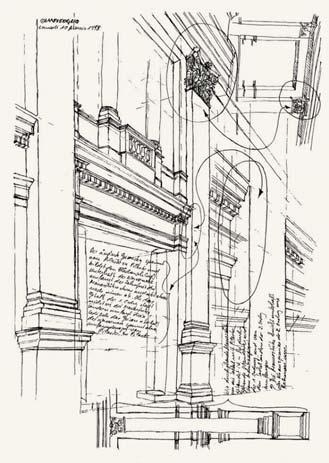

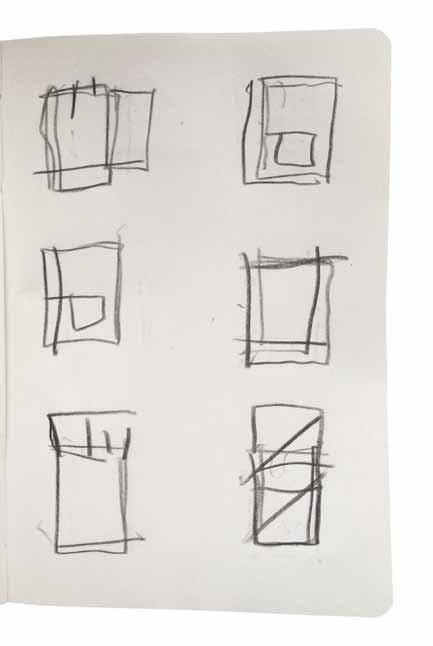

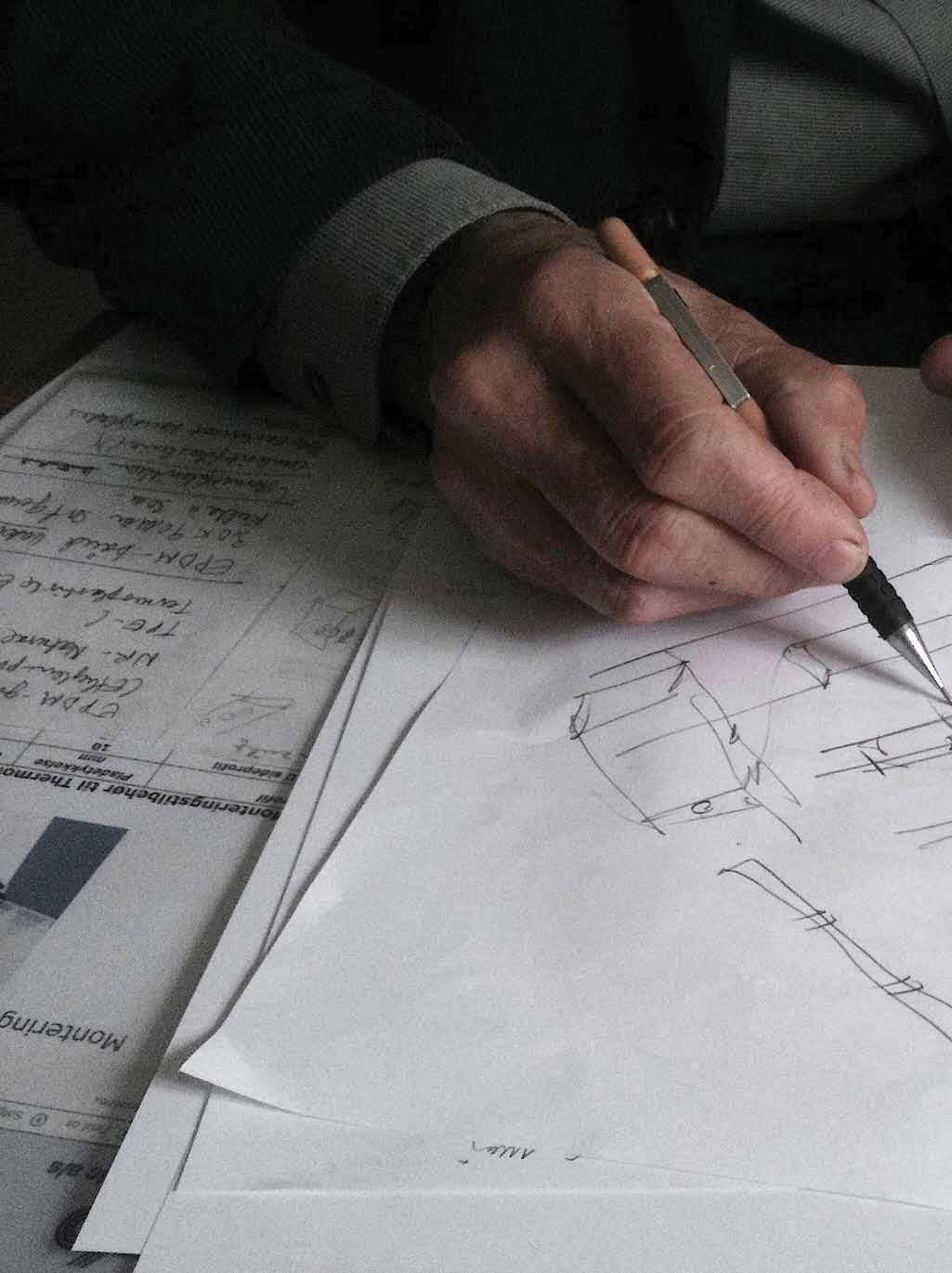

In the following we shall see how studies of the building culture have played a seminal role as an artistic catalyst in the Danish architectural tradition. Especially drafting and measured survey has been of primary importance. The process of conducting measured survey and drafting is formally complementary to the process of artistic work. Inherently, measured survey requires a bodily, physical presence which causes that the observed is not only understood epistemically, but also internalised corporeally. Through the draft-

ing of the hand, the observed is memorised as bodily experience. In the further artistic work, these bodily experiences are inadvertently crystallised, and thus bring about a certain ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������-

Whereas the architecture of the twentieth century apparently represents a rupture with the classical and classicistic building culture, it turns out that a number of artistically pregnant values are conveyed into and carried on in the modern movement. Correspondingly, ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� antique decorum, but a closer look shows that classical antiquity rather played the role of a reservoir of artistic pregnancy which continuously incubated an original and dynamically changing artistic practice. From the School of Ornaments at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, over the “Temple Class” of Kaj Gottlob, to the watercolours of Arne Jacobsen, we see a culture wherein the drafted observation is the decisive factor of the artistic

the works of particularly Jacobsen, could not have been conceived without the knowledge of the architecture of classical antiquity. Thus it seems that the artist-genius who ex nihilo gives birth to his artefacts is a notion with a limited historical validity.

- CASPAR FRIEDRICH HARSDORFF -

tradition, C.F. Harsdorff (1735 - 1799). A student of Nicolas-Henri Jardin, Harsdorff was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1756. This award granted �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� architect to embark on an educational journey from the academy. It is certain that he spent

his stay in Rome a number of drawings are preserved, of which a series of 15 measured survey sheets from The Hadrian’s Villa should be mentioned. That we are dealing with actual measured survey sheets is an unequivocal fact according to Hakon Lund,i since at that time there only existed one measured survey of The Hadrian’s Villa. This survey was in the scale of 1:3000, whereas the survey conducted by Harsdorff is approximately in the scale of 1:96. Moreover, the quality of the drawings clearly indicates that this is the case: they are sketchy, abundantly supplied with dimension and construction lines as well as with hand-written notes on the observed. In addition, the Indian ink is unevenly dried up as

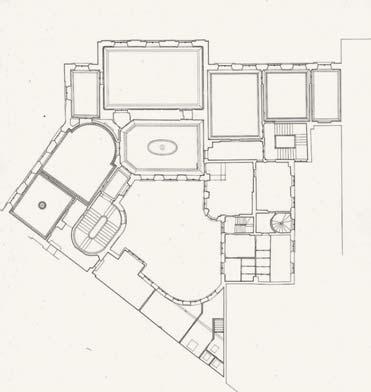

If, for awhile, we were to reject the traditional epochal and historising perspective, and instead solidarised with Harsdorff the architect, what would we then see? If we observe

ments of one orthogonal structure, mainly consisting of an oblong room with a circular

ending, an octagonal room and a circular room. All three rooms are in their voluminosity ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� the masonry is penetrated by passages and circular niches, all located radially on the circular centres of the three rooms. In the top right corner we see another orthogonal structure, ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������standing that the rooms are respectively a tepidarium, a caldarium and an apodyterium, notwithstanding that the left structure is stereotomic due to the fact that it is a part of the thermae, and the right structure is tectonic since it is a part of the stadium, we observe on a more immediate level an artistic handling of a series of complex spaces, which by a number of simple moves are executed completely unstrained and without blemish.

Furthermore, these drawings should be understood as the retained experiences of Harsdorff, acquired spatially and corporeally through the protracted process of surveying. Expressed in the abstract language of drawing, but related to a number of bodily experiences; such a drawing ties the architect’s experienced reality to his drawing practice, and is therefore as experience considered of key importance in the further artistic work, wherein the same process is formally repeated in reverse.

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� a communication of knowledge, as if the drafted observations were deposited in him and precipitated in his own work. Again the main rooms appear as geometrically precise volumes, tied together in two orthogonal structures, and rotated around a ball-and-socket joint, as it were. In several places the thickness of the walls is greater than what seems

LOST AND FOUND

constructionally necessary, and we can thus conclude that the voluminous appearance of the spaces and their interconnectedness is an artistically leading motif. We observe how Harsdorff manages to deal with a complex manifoldness of spatialities in a harmonious whole by applying the same artistic motif as seen in the Hadrian’s Villa. This is not done by reproducing an antique decorum, nor through a mimetic reiteration of the beholded, but, on the contrary, by a clever observation of formal architectonic compositoric motifs interpreted in an original work.

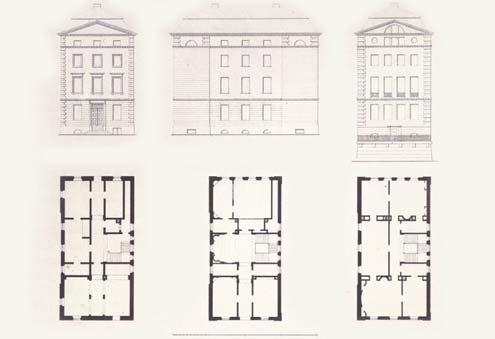

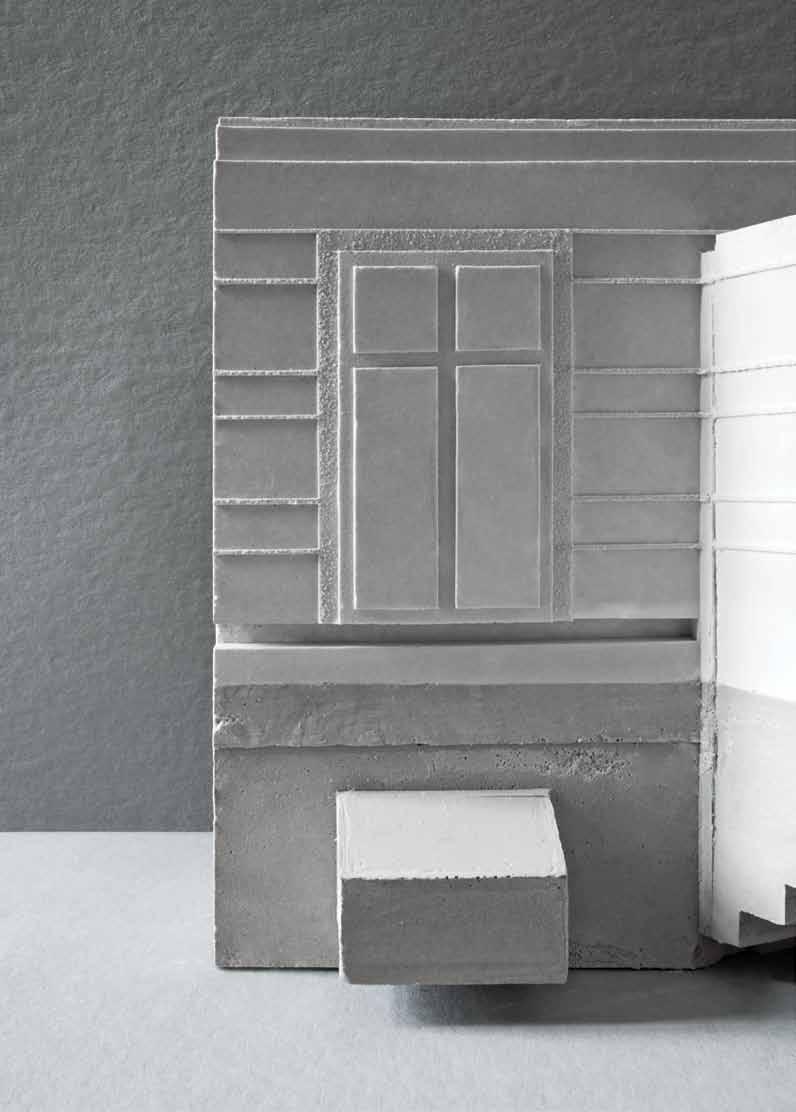

Francesco Borromini (1599 - 1667). Harsdorff’s Mansion shares a formal compositorial relationship with San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane, since both buildings manage to handle the challenging problem of attaining monumentality and unity on a small irregular and cramped corner plot. In part, this is done by applying several overlapping local symmetries and thus attaining a balanced unity in the otherwise asymmetrical. However, at this point Harsdorff surpasses Borromini: while Borromini’s main facade stands out due to its massive ornamental décor, and thus almost seems to be applied as one would put on a mask, Harsdorff’s Mansion is shaped in a plastic unity. Albeit he makes a risalit stand out, it appears as an integral part of the facade, which is folded and bent around the corner, as it were. Whether or not Harsdorff studied San Carlo alle Quatro Fontane is as yet uncertain, but it seems absolutely plausible that he, to some extent, did so during his time in Rome.

The above mentioned example of how architectonic knowledge is passed on and re�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� as a paragon for the master builders of Copenhagen. For that reason, let’s have a closer

look at the mansion on Kongens Nytorv. As mentioned, Harsdorff makes use of several overlapping symmetries in the composition of the facade, and thus elegantly handles a ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ on Kongens Nytorv by a competent articulation of a square central risalit adorned with a �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� windows of the piano nobile. The left wing plays an ambiguous compositoric role, since it can also be viewed as a slightly protruding side risalit of the left part of the facade, as it is mirrored over the slightly recessed middle. The perspective relief effect of the middle part ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� the left part of the facade can be read as an independent secondary unity, is very much due to the centrally placed front door, which thus marks the vertical axis of symmetry. Without this door, the concept would not have worked. Finally, the facade is canted around the corner radically, thus elegantly making room for yet another independent unity of the same formal composition as the previous, albeit placed lower hierarchically. The fact that the building is nevertheless read as a plastic unity, is not only due to the overlapping symmetries, but also due to its very carefully planned proportions. By analysing the facade ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ and its ability to reproduce itself harmoniously by constant division appears to play an important role. By way of example, the central risalit is in the ratio of 1:1, whereas the two side wings are both in the ratio of �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

clude that Harsdorff prescriptively made use of these proportions in his design, but the actual descriptive evidence seems too consistent to be ignored as a mere coincidence. The fact that the Danish bourgeoisie of the 18th century were typically educated in geometry, namely by reading The Elements of Euclid as a part of their bildung, supports this theory.

One could assume that during his survey of the Hadrian’s Villa, Harsdorff observed the conspicuous relationship between building, structure and landscape. Nonetheless, Harsdorff’s Mansion is conceived as a member of a plastic and perspective whole on Kongens Nytorv, together with the now demolished cannon foundry Gietshuset and

Harsdorff makes use of overlapping symmetries internally in his composition of the facade of the mansion, so does he apply this motif in a masterly manner on a macro level by inscribing the mansion in a symmetric relation to the other buildings. The motif thus shifts from building to context, and thereby exceeds its formal origin. This often neglected

quality of classicism is described incisively by Poul Ingemann, albeit in another context: “Thus exists a fundamental will to let the architectonic appear in the bulk, and not in the isolated members. The joint or the transition becomes of less importance, and does not demand to be exposed as something special. It lives concealed and endures neglection, and it appears as competent additions or changes in the score.”iii

- CARL PETERSEN -

architectural scene of the posterity.iv A shrewd observer demonstrating a clear grasp of the artistically pregnant, Carl Petersen formulates a kind of architectonical poetic with his three manuscripts “Oppositions”, “Textural Effects” and “Colours”, and not least with

much to the point, that Carl Petersen is the product of a culture that emphasised building survey through the direct artistic encounter with the building culture. One of the central institutions of this culture that Carl Petersen can be associated with was “The Society of December 3rd, 1893”, a society of architects devoted to the study of architecture through drafting and measured survey. Contrary to the traditional approach, the members of the society did not restrict their studies to the classical masterpieces, but did as well include buildings of an anonymous and unostentatious character. This fact clearly proves two important points. Firstly, it is through the practice of conducting measured survey in itself that the architect acquires a profound understanding of the spatial reality of architecture. Secondly, artistic competence is not developed through the study of certain styles, but instead through the direct encounter with aesthetically pregnant effects, be they mundane or classical. It is remarkable that most of the members of the society were later to become some of the leading architects of Denmark. The Society of December 3rd published ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� architects as Kay Fisker, Povl Baumann, Aage Rafn and, as mentioned, Carl Petersen.

tioning, namely “The Free Association of Architects”, a fraction of “The Association of Architects”, established on the 5 May 1909. A leading member of The Free Association of Architects, Carl Petersen was the instigator of the agitation against the construction of a spire on the cathedral of Copenhagen, the Church of Our Lady built by the great Danish classicist C.F. Hansen, a student of C.F. Harsdorff. Having remained in oblivion

for a lengthy period, C.F. Hansen was rehabilitated as one of the most artistically pregnant architects of the Danish tradition, very much due to the fact that Carl Petersen, in this context, arranged a great exhibition of the drawings of Hansen. As we shall se, it turns out that the poetic developed by Carl Petersen is indebted to the study of the legacy of C.F. Hansen. By reading the accompanied description of the exhibition, one senses Carl Petersen’s eminent understanding of and familiarity with the pregnancy of the art of C.F. Hansen. Capable of intonating his buildings as few others by an excellent command of the ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� his ability to administer and transform a roman-antique legacy in a genuinely independent artistic practice. It is precisely C.F. Hansen’s artistic exactness through his perfect command of the architectonical craftsmanship that Carl Petersen recognises; that is, his ability to make use of exactly the right aesthetic effects to achieve his artistic purpose. Strikingly, this is exactly the subject of Carl Petersen’s manuscript “Oppositions” from 1920.

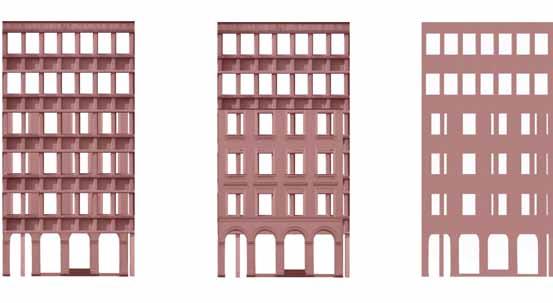

In “Oppositions”, Petersen describes among other things the importance of scale in architecture. In order to achieve monumentality one must stress the greatest dimension of a building. “Thus, if one is working on a long house,” writes Petersen, “...one could easily disturb the impression hereof, if one designs a roof with tall dormers that extends the brick facade upwards. On the contrary, a long dormer on top of the roof surface can often strengthen the impression of the length of the building. Then again, if one is working on a tall building, one can increase the impression of the height by extending the facade upwards in a brick dormer.”v If one compares the above-mentioned with Carl Petersen’s description from 1911 of one of the earliest works of C.F. Hansen, a house on ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� of C.F. Hansen: “The rear facade facing the canal is taller than the two other facades. The ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

LOST AND FOUND

the main facade on the opposite side, an attempt to convey the impression of broadness is made. Thus the corner rustication is made narrower, there is one less window on each ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Carl Petersen to a very great extend developed his poetics on the basis of his studies of C.F. Hansen.

Carl Petersen emphasises that even though C.F. Hansen draws upon roman antiquity, he is “... completely liberated from his ideal and creates independently and originally. He makes use of the artistic effects with a clear awareness that excludes the accidental.”vii. This could just as well be said of Carl Petersen. In spite of formally drawing upon a legacy from C.F. Hansen and Palladio, the works of Carl Petersen are both original and at closer inspection remarkably modern. A work like the project for a housing block on the plot of ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� with Ivar Bentsen clearly demonstrates how an experience of modernity is administered in a classicistic decorum. The almost 700 meters long structure with its machinelike seriality of identical Danish casement windows appears almost ornamentally undressed. When the ornament does appear it is strictly architectonic, meaning that it only is applied when it serves the purpose of accentuating the main tectonic members, such as the eaves’ mediation of the transition from wall to roof. This pathos of absence is also found in the

almost resonant emptiness of the gigantic gateways as well as in the empty central square ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� traditional equestrian statue.viii All of these are artistically pregnant motifs, unfolded in a classical decorum but deeply original and representing an aesthetical interpretation of modernity.

Lastly, let’s have a look at how a corporeally internalised understanding of the poetics of architecture acquired through building survey can play a crucial role in the artistic practise of today. The German sculptor and architectural theorist Prof. Dr. Thomas Gronegger (b. 1965) has, in his highly interesting work “Roma Decorum - Design Processes in Architecture”, shown how the European building culture constitutes a rich reservoir of artistic pregnancy which can still today be drawn on. In almost 200 survey sheets made

baroque era, among others the works of Michelangelo, Maderno, Bernini and Borromini. Together with a photographic archive these survey sheets constitutes the empirical data for

“My decision to opt for this sketched design is the consequence of an awareness that the understanding of form is an individual process which must be experienced on site in a direct artistic encounter with the works.”ix writes Gronegger in the introductory notes, thus stressing the importance of the mere process of surveying.

As we have seen in the previous two examples, genuine artistic progress does not ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ones predecessors. According to Gronegger: “... the possibility of making a genuine step forward lies in fostering an awareness that something new cannot result from ignoring the world of where we come from but can only grow by processing the intellectual, artistic �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������cerns and those fruitful but somewhat remote developments from the past eras and other ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� by Gronegger are of paramount importance. Contrary to a more traditional historical study, the artistic nature of the methods applied uncover important aspects of the artistic ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������chitectural researcher. Since the knowledge acquired through the process of surveying is, to a large extent, of a bodily nature, it is intrinsically personal, and the research conducted is thus, strictly speaking, not reproducible, making it foreign to the more traditional virtues of research. Still, as we have seen, the method is capable of yielding knowledge of the otherwise often inaccessible domains of aesthetics.

On the basis of the understanding acquired through these studies, Gronegger builds his own artistic practise. In an exhibition entitled “Wandstücke” held at the Glypthotek in Munich in 2006, Gronegger displayed four sculptures, all of which were fragmentary and rather imaginative transformations of a classicistic ornamental décor. A classical decorum deconstructed, the works of Gronegger uncovers the artistic pregnancy of the plastic tra-

ditions of European architecture by removal of context and style. Quite obviously, these �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� study in Rome.

The research conducted by Gronegger is thus of a two-fold nature. Firstly, the intense �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� But secondly, by immersing himself into the study Gronegger uncovers what seem to be fundamental truths about the aesthetic structures of the works studied. The former ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Gronegger shows that even today the careful study of classical architecture can be highly rewarding to an ongoing and progressive artistic practice, as well as to the research into the fundamental aesthetics of architecture. Certainly, drafting and measured survey as a means to acquire profound knowledge of the fundamental aesthetical principles of architecture has shown to be as crucial today as it has ever been since the architects of the renaissance begun to study the legacy of classical antiquity. Drafting and measured survey is an excellent means to acquire profound knowledge of the fundamental aesthetical principles of architecture, and is thus not only valuable to the creating architect, but also to the architectural researcher. And as we have seen, such knowledge can only be acquired through a direct artistic encounter with the building culture.

When Architects and Designers Write / Draw / Build / ?

LOST AND FOUND

METTE JERL JENSEN

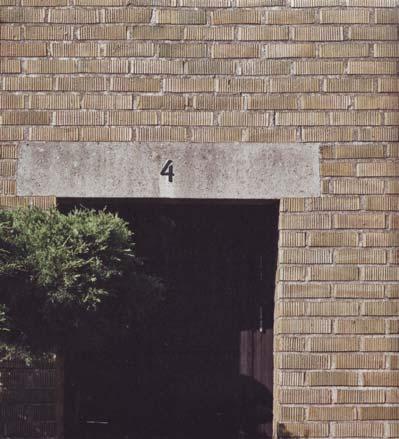

This text sets out to study and explain a term that generates particular awareness of the connotations of brick. The British architects Sergison Bates name it ‘brickness’. Brickness �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� in an attempt to inscribe the term in a semantic Danish context.

The following examination of brickness as a notion is based on texts written by prac�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������thetic considerations.

- PATHOS -

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������tures’1��������������������������������������������������2����������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

He asks whether there is any other building material than brick that is charged with such ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� simply using brickwork as a means of appeasing these associations with emotions for the past. The use of brickwork must not turn into a story of past losses.

LOST AND FOUND

- THE RUDIMENTARY BRICK -

in his essay ‘Brick’ 3. He argues that there is no building material shrouded in as much mystery and with so many myths as brick. Brick’s links with the origins of humanity bestow

ing material consisting of the four elements considered by ancient philosophers to form

- LAYER BY LAYER -

In ‘Von der Bebauung der Erde’5��������������������������������������������������

the process of how these

are layered. He compares soil layering with

BRICKNESS REVISITED

��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������tion of the earth draws recognisable traces up through brickwork’s layers of bonding and ����������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� composition of society�

- A CONVERSATION WITH BRICK���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

matter how many times Kahn apparently came up with proposals for more rational solu������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ �����������������

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������� ���������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� fullest extent.

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

the parts of a building should not look like something other than that they really are11. He

forms in their temples that fell within the bounds of carpentry12. Lodoli indicated that

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ �����������������������������������������������������

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

is key to emphasise here is that although Semper considered the underlying structure as ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� essential. To at all be able to establish a durable abutment on which to place the chosen �������������������������������������������������������������������������. ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

LOST AND FOUND

incapable of doing. Brickness reaches beyond natural characteristics and elements such as

open-minded attitude towards and a curiosity about the material. Always bound by prag�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������

Christoffer Harlang

We are brought into this world, but to exist here we must change it; within this simple statement is an inspiring truth about the fundamental meaning of architecture. Throughout time, people have endeavoured to change the world, and from their efforts we understand who we are and how we regard both each other and the world – every time material has been shaped into form, when locations have been transformed into places, and every time we have altered our world so that it can accommodate. These statements primarily come to the fore through space. But space is not everything; between us and our surroundings is something crucial – form. It is form that allows us to experience the world; it is through the design of form that things obtain presence. And form is very different to space; there is something final and complete about form – form is closed. So it is between the openness of space and the ‘closedness’ of form that an architect must prove his or her worth; it is here we must intervene. The fact that this is not a new phenomenon is irrelevant. Another, yet related, context can be found in Martin Heidegger’s inspirational description of the architect as a “responder” – a person who alternately listens to the openness of the space and responds with form.

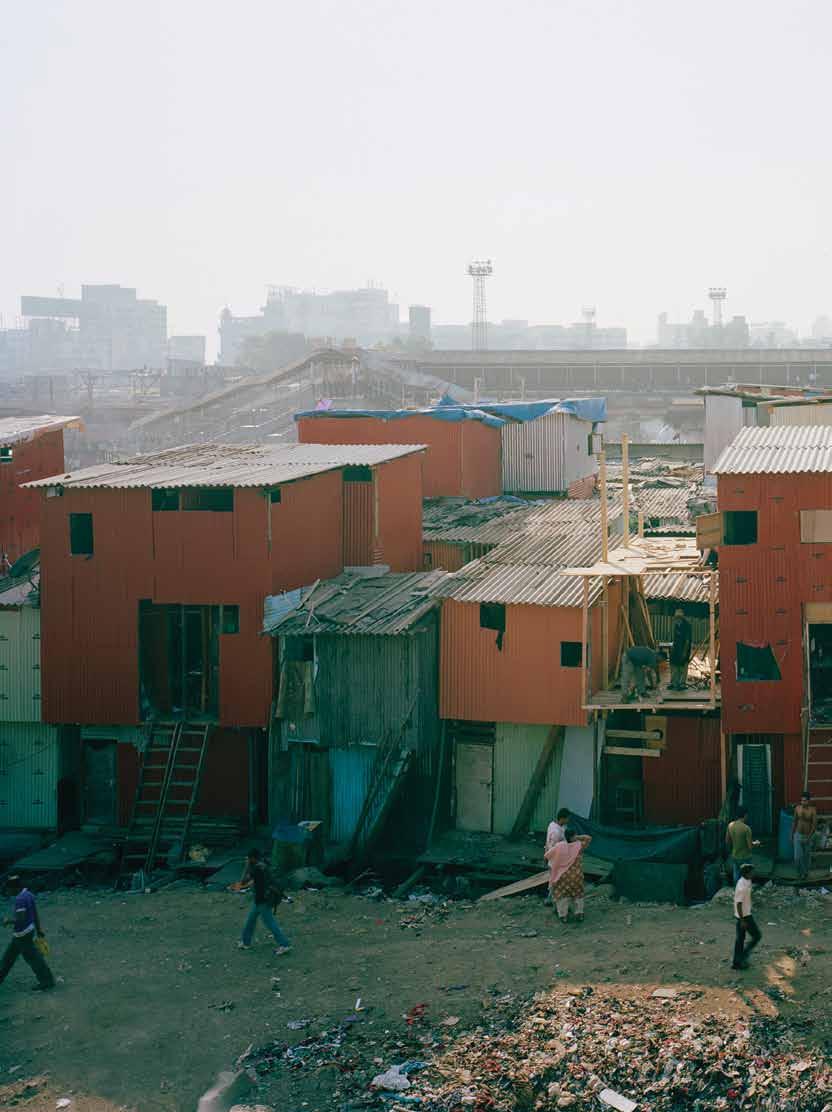

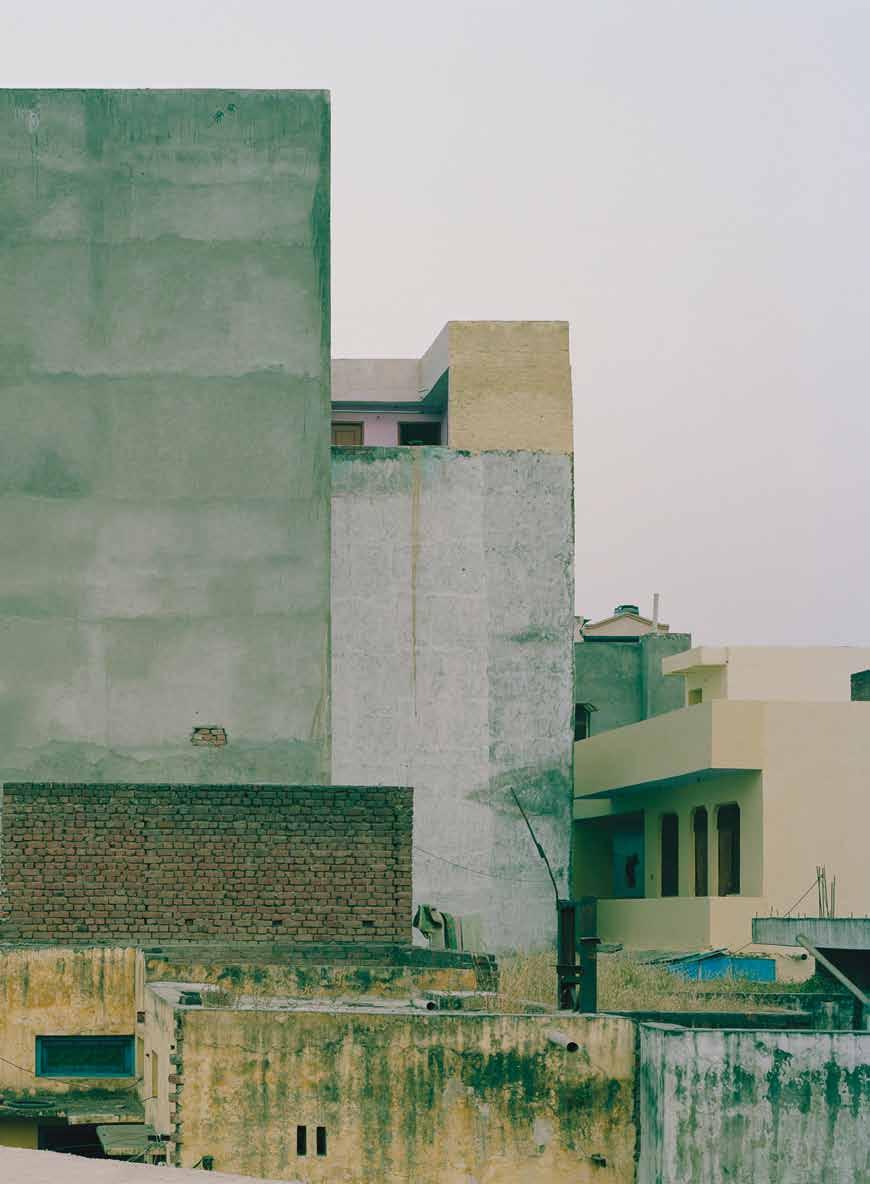

Heidegger focusses on how a construction obtains form through the meeting between construction method and the mountainside upon which it is built and the wind, the snow and the rain. But architecture has changed since Heidegger’s time. Today, architecture only rarely stands upon Heidegger’s virginal hillside. In our current architectural world, challenges that can merely be solved by means of sensitive exchange between a construction, the landscape and the clouds in the sky are few and far between. Since 1930, the population of the planet has increased by over 330%, and density and urbanisation have become the controlling factors. And the Europe of today is almost completely built up. Prognoses show that over 70% of the assignments that architects will work with in the future will deal with altering existing constructions. In the future, little will be built from scratch; instead, we will modify or extend something that someone else has brought into the world. On top of this come modern-day demands for sustainability, stipulating that buildings be transformed rather than demolished. And we face a wealth of challenges to transform buildings and reduce their environmental impact.

The majority of our present-day buildings were constructed after 1945; consequently, the focus of education and research should be on transforming our welfare-state buildings. But with modernity, the perception of the architectural work has changed – a development that fails to sufficiently reflect itself in the way we currently manage modernism’s cultural heritage. In the future, we must engage in critical dialogue with “the open work” of 1960s and 1970s Danish architecture in order to bring about a more identifiable understanding that can be used as a foundation for designing operative solutions that can transform these buildings in the future. A number of recent transformations – including the remodelling of housing complexes – have been based upon an aesthetic foundation raised as a negation of the development’s original modernistic ethos. It can be correctly argued, to some extent, that that the architectural ideology governing these interventions and changes has primarily been one of a decorative end reactive approach, in which the white, abstract space of modernism has been applied to the spatial elements and where colours have been toned down. The expectation has been that the stigmatised visual environment be tempered through adding ‘softer’ forms, polychromatic colours, symmetry and planting, in order to meet the desire for an identifiable common space. But what results is usually of poor quality, with a tendency towards overuse of materials with limited longevity – these become merely an expression of an un-reflected, cosmetic approach to the specific architectural problems and to the original values and qualities. At the same

time, earlier studies have shown that renovations conducted in the 1990s are of such dubious technical quality that they already now need to be renewed.

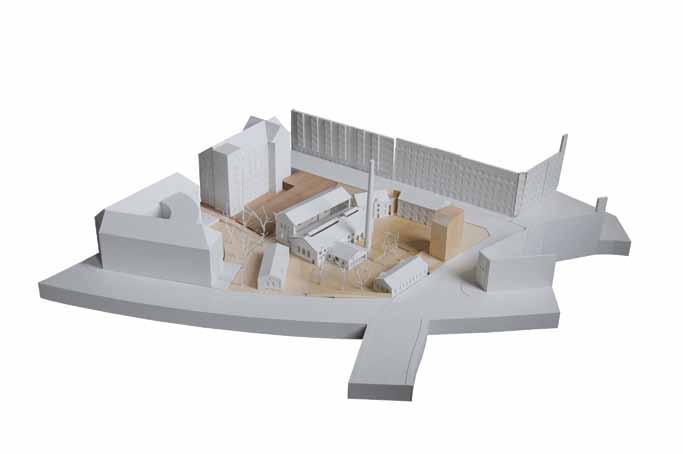

The transformation from industrial to information society has left many buildings functionless, and even entire city districts now need to be redeveloped for completely new purposes. There are already many excellent examples of this, both in Denmark and abroad. One such example is Entasis’s intelligent master plan called Vores By, which deals with the regeneration of the defunct Carlsberg brewery site in Copenhagen. The Vores By project shows just what can be achieved when a heterogeneous complex thinking and intimate sensitive understanding come together. A sensitive understanding leads to emotion. Such qualities are not to be found in the suburbanmentality that dominated the redevelopment of the Holmen area of central Copenhagen. The lesson learned from this is that flush facades, yellow brick and low buildings constitute far too primitive a tool for developing a historic city district. The suburban insipidity of Holmen shows that we desperately require more knowledge and better tools in order to qualify the coming years’ transformation of our city and out building culture. It is in particular the architectonic challenges of continuity and change, of the anonymous building culture and architectural works, and society’s dynamics,that become apparent in the many current projects dealing with transforming and restaurant buildings and urban areas.

Using Heidegger’s analogy, we must position ourselves as a responder to what already exists from history, and we must alternately listen and respond in a dialogue where what we contribute is no less valuable than that which exists from history. Only in this way, can the dialogue be as rewarding as that which Heidegger had on the mountain. And this was precisely what Peter Zumthor managed when, in 1990, he worked on the Gugalun Haus, a small Alpine chalet that dates back to the 1700s. In his design, the typology of the original building remains through the structure’s profile and the tectonic culture is carried on in a new form of construction. This both anchors the house to its slope and optimises the house, enabling it to meet contemporary requirements and uses. With Zumthor’s additions, the house stands stronger on its slope today than ever before.

First and foremost, the architect is a ‘bound’ artist who, on the basis of pragmatic, formal and cultural bonds, manages to invest an emotional content in the realisation of a work. It is this content that, once a work is completed, the viewer recognises and which touches the viewer, providing the viewer with a sense of belonging in the world.

What carries forward the architectonic work is a method whereby a range of complex relations – alternating between conscious and unconscious – are synthesised to a level of order en entirety that delivers an emotional content.

So it is through a culturally sensitive mastery of a building’s technical realities we seek to create meaning in architecture. In terms of Transformation, we are concerned with aspects close to the building and we are looking for architectural effects that result from a process in which a mental content is expressed through a specific technical solution. What carries projects forward is a method whereby a range of complex relations – alternating between conscious and unconscious – are synthesised to a level of order en entirety that delivers an emotional content. We consider the concept of empathy as a fundamental element in this process. Empathy includes both interpersonal empathy as well as the ability to empathise with a complexity of technical, social, psychological and functional conditions. But when it comes to transformation, empathy lies within cultural heritage, in what already exists from history, and is a prerequisite

for the identity of any architectural design. Studies have shown that the dilapidated historic districts have complex properties and composite values, which, through sensitive architectural thinking, can be developed into well-functioning and identity-giving buildings and urban districts.