HOMELESS IN A LAND OF PLENTY

By Mark Schumann

By Mark Schumann

By Mark Schumann

By Mark Schumann

In the fall of 2016, when my wife, Cheri, and I were living in Taos, New Mexico, the thought occurred to me one morning that I should draw on my background in photojournalism to document the current and growing crisis of homelessness in America. At the time, I was making images of the northern New Mexico landscape, giving private photography tours, and managing a small art gallery. Later that same day, I wandered into a used bookstore. There, prominently displayed on the front table, was a copy of Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning, a book about the life and work of this famous Depression-era photographer. Lange, of course, created the photograph, “Migrant Mother,” which became an iconic image of the Great Depression.

Within a few weeks, I found myself photographing and interviewing in Chicago, then Los Angeles, and eventually in some 70 cities across the country, from Portland, Maine, to Orlando, Florida, to San Diego, California, to Seattle, Washington.

In late February of 2020, I made one final trip for the project, just before the COVID-19 pandemic led to a nationwide lockdown. On that final trip, I first flew to New York City to see an exhibit of Lange’s work at the Modern Museum of Art. Then I traveled by Amtrak to Baltimore, Charlottesville, Atlanta, Birmingham, and finally to New Orleans, before flying home to New Mexico.

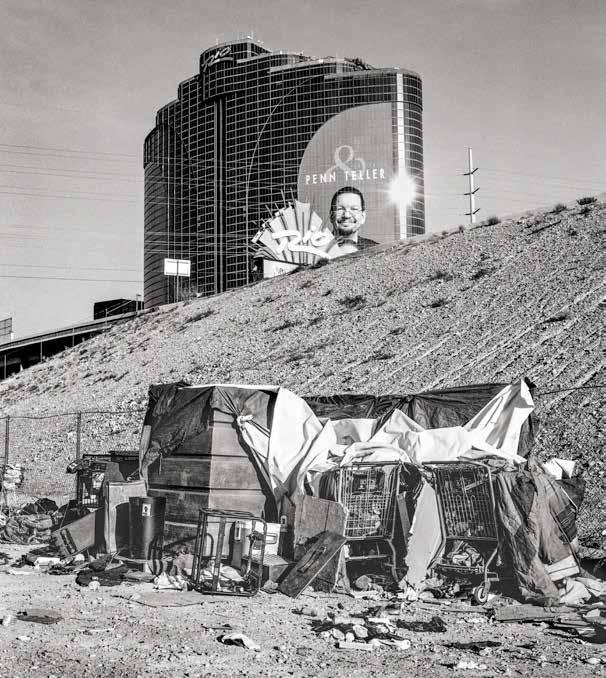

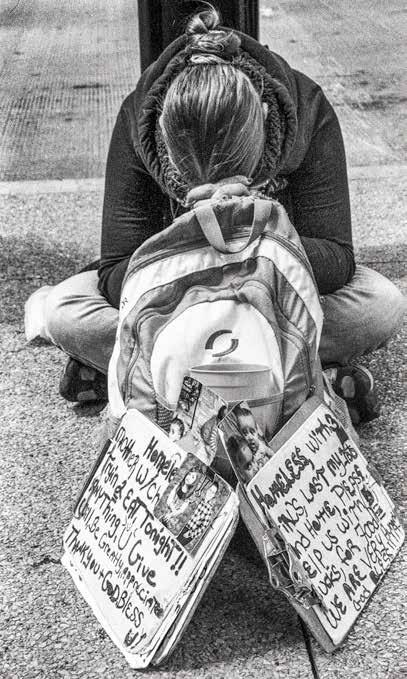

Acknowledging differing points of view on this, I believe there is a compelling need to both more fully document this sad reality of modern American life and raise public awareness to the extent of the homeless crisis. Even more importantly, I see a need to put a human face on this tragedy that affects more than half a million Americans.

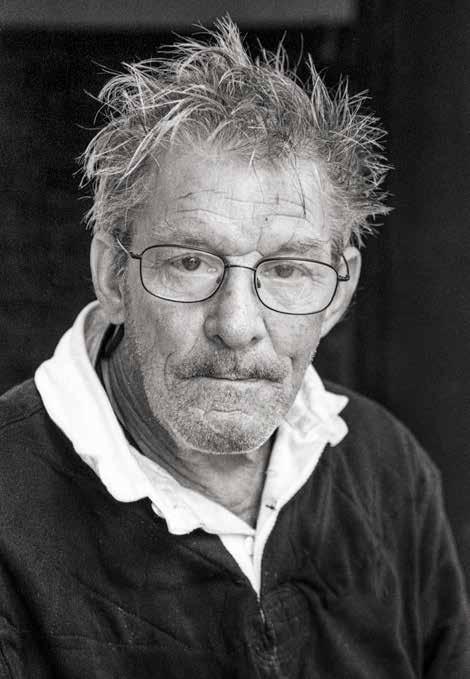

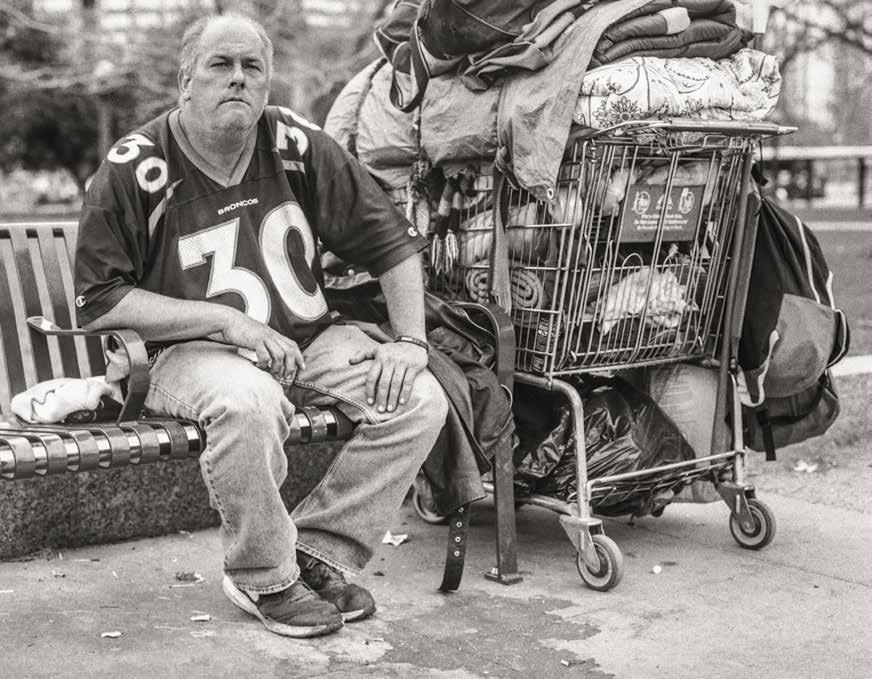

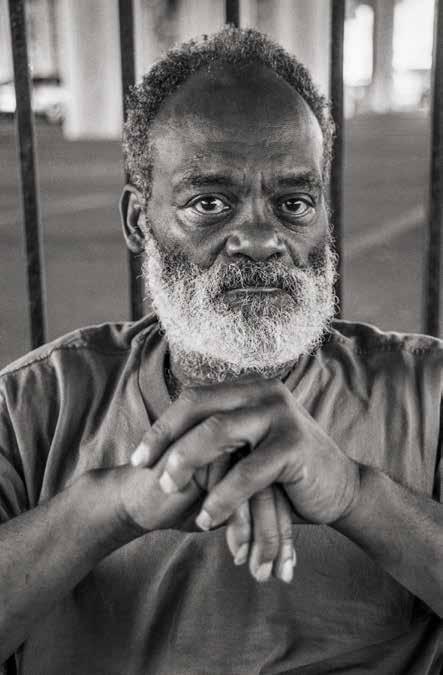

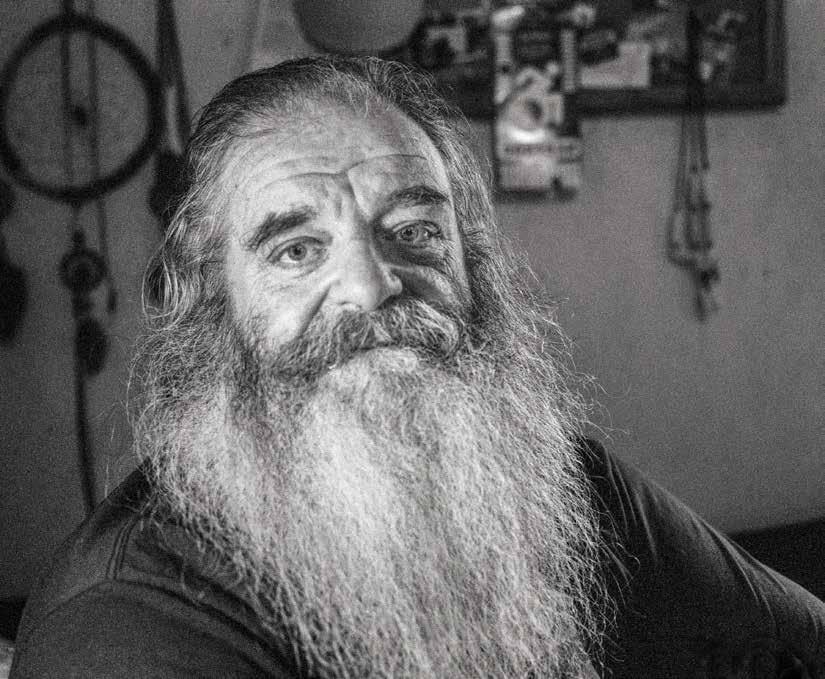

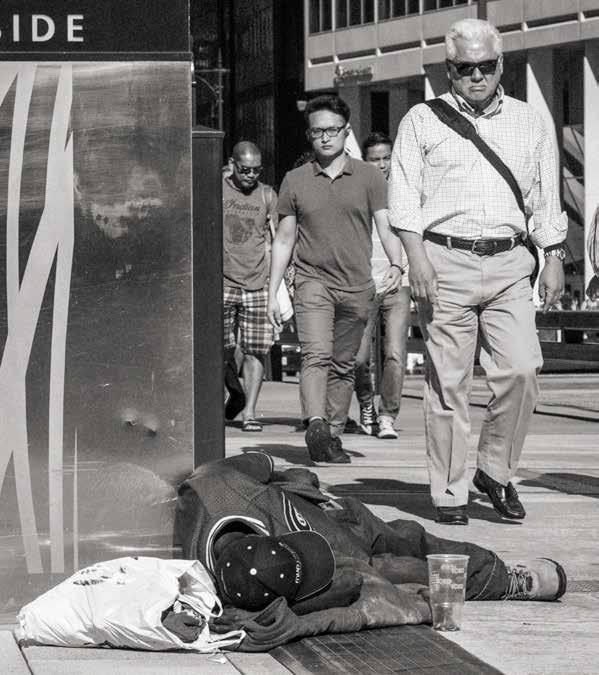

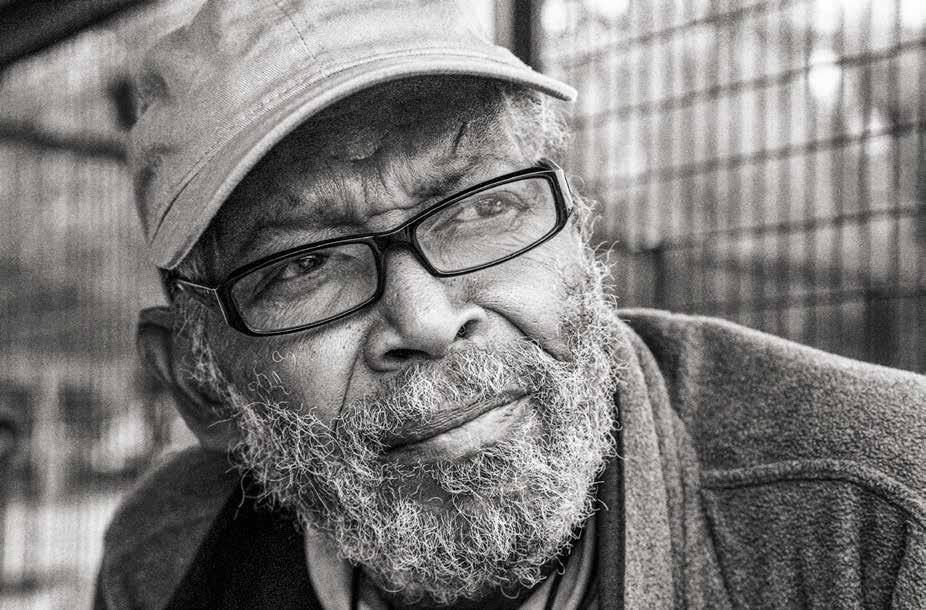

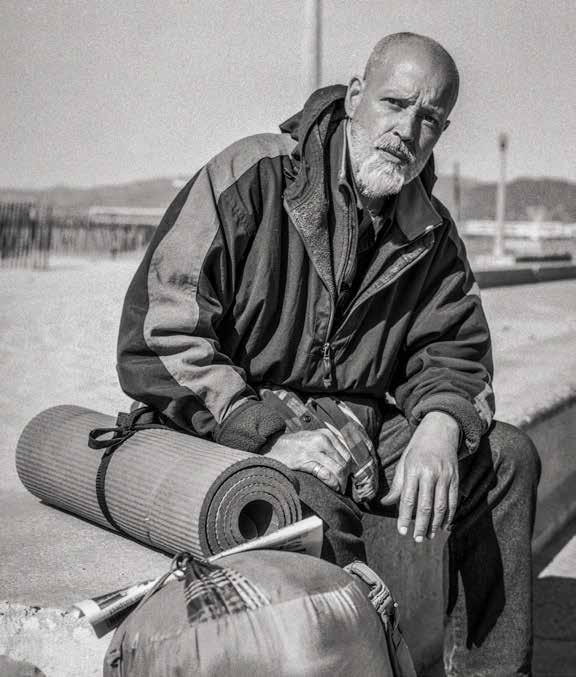

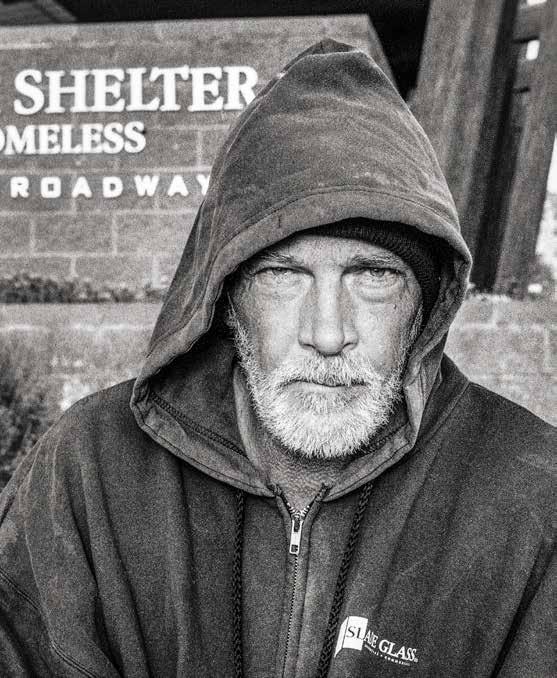

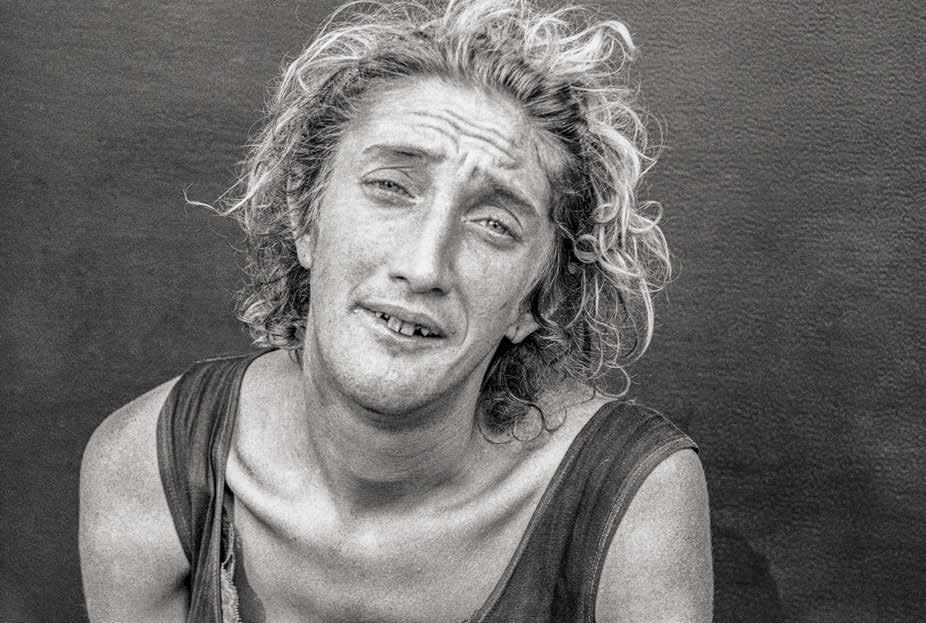

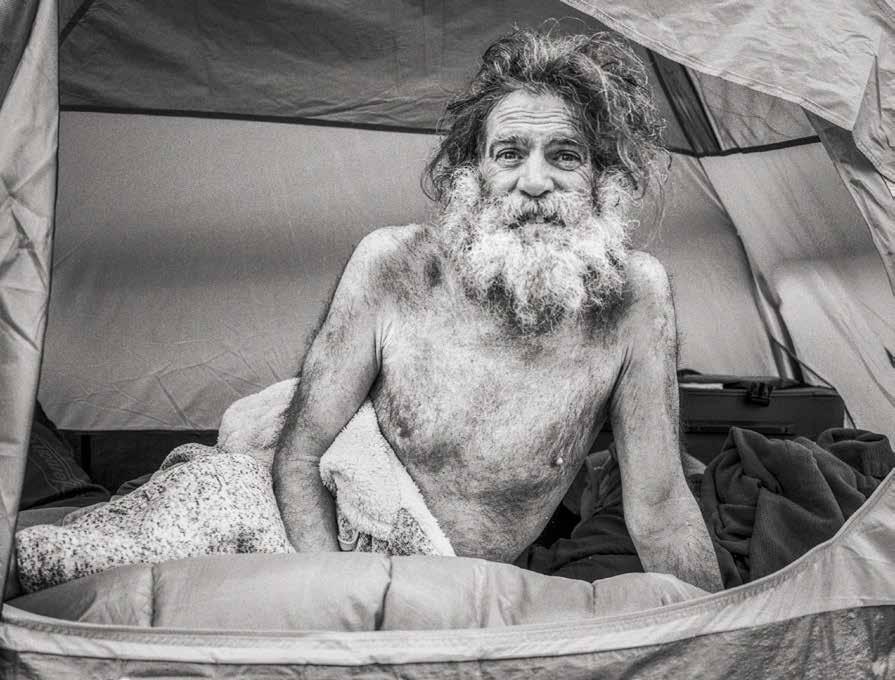

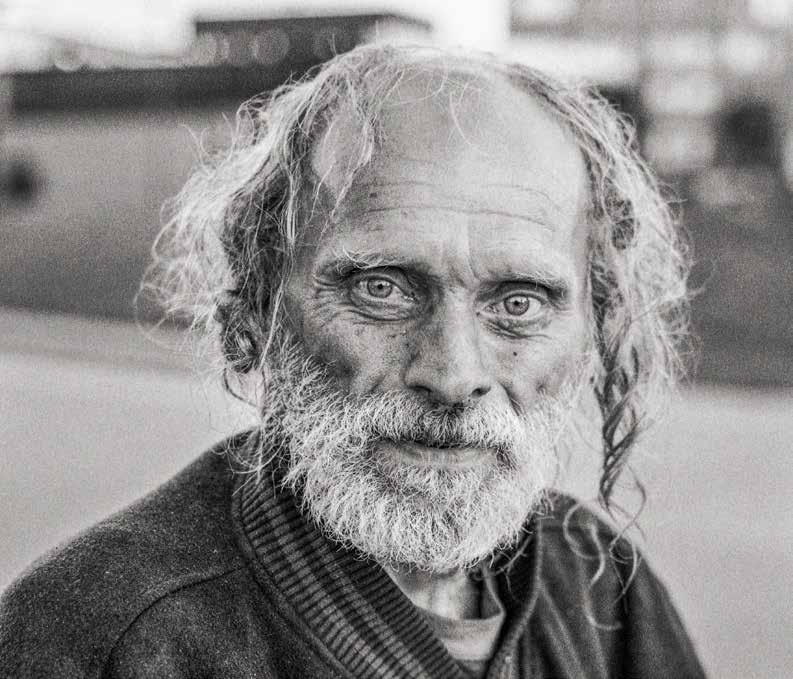

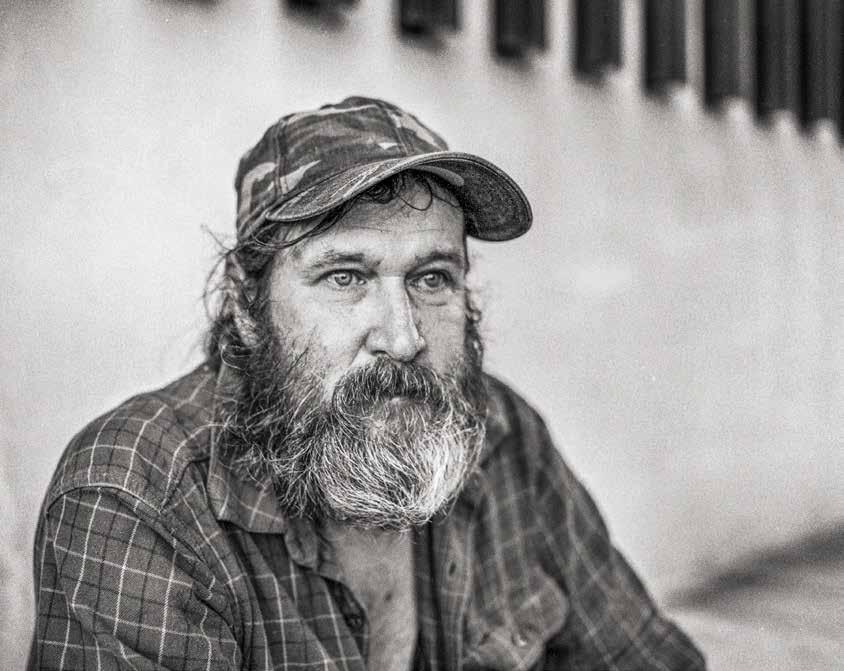

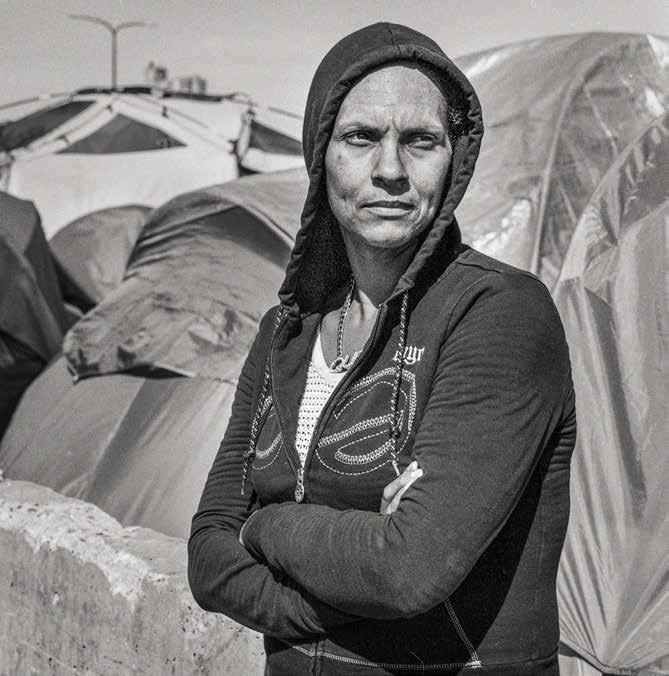

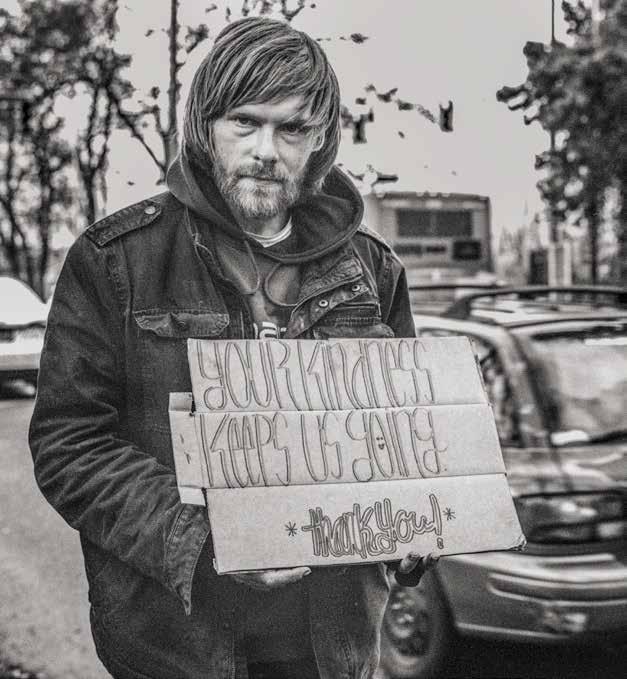

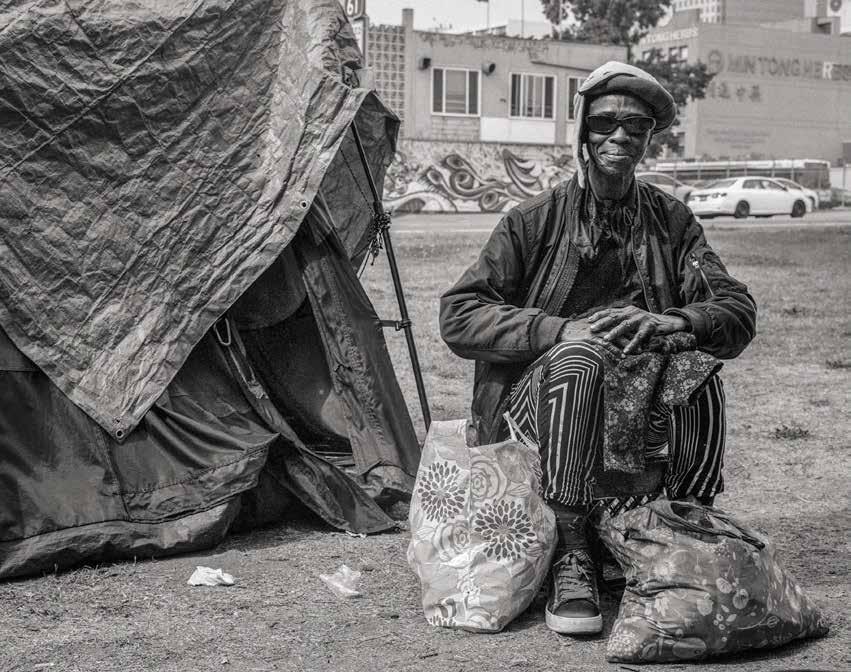

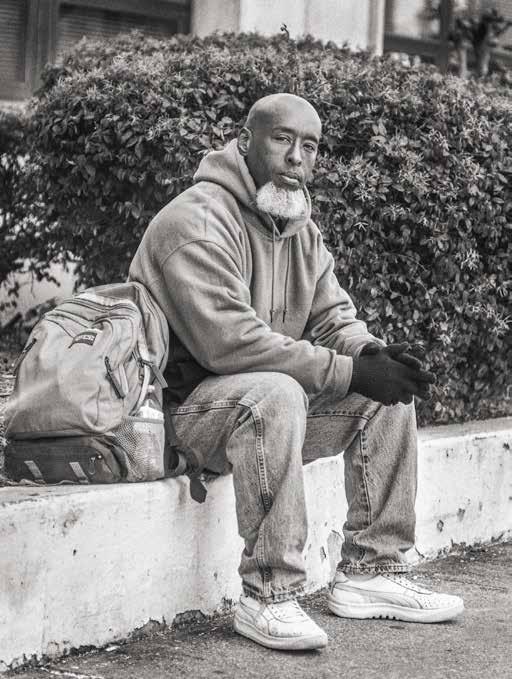

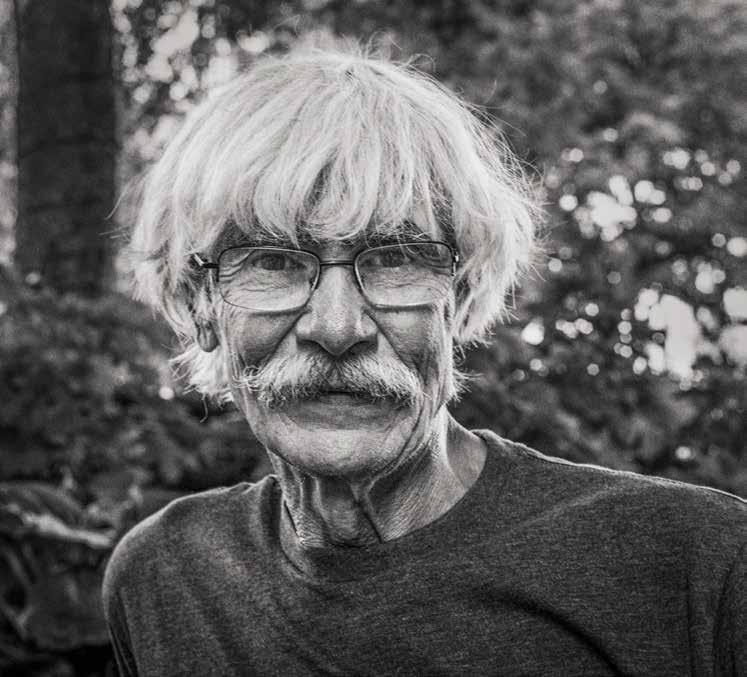

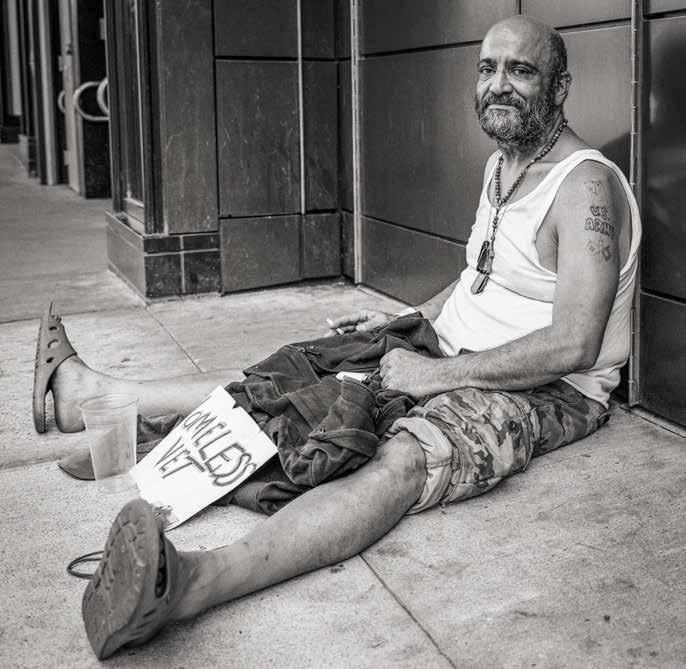

Though some of the images in this project show the living conditions of the unsheltered, the majority are street portraits. While I hope this work accurately illustrates the harsh living conditions on the street, I am offering the viewer an opportunity to see, not tents, but faces, and I hope some will, through these images, be able to look into the eyes of persons experiencing homelessness, and there make a human connection.

Certainly, experiencing genuine human connections is what I sought as I pursued this documentary. After introducing myself, I would express interest in the person and would then ask if I could make an image of them to be included in the project which I explained would become a book, with the proceeds to be donated to homeless service providers. Very few people I approached asked not to be photographed. Many said they appreciated an opportunity to be seen and heard. After all, a common lament among persons experiencing homelessness is that they feel as if they are invisible.

Though the economic crisis of the 1930s is nearly a century behind us, for many Americans without stable housing, these are greatly depressing times. And so, wanting the images in this project to resonate with and echo an earlier time, I photographed exclusively with black and white film. Working with film presented its challenges, particularly when passing through airport security. On a trip to San Diego, where I planned to do some early morning and night photography, I took film too sensitive to light to be passed through security scanners. Each roll of film had to be individually inspected, both as I departed from Albuquerque, and in San Diego as I returned. I am grateful to the TSA agents who were patient with me.

My wife, Cheri, exercised heroic patience as I traveled for this project, and then returned home only to get lost in film developing and image editing. For her support, encouragement, and boundless forbearance, I give thanks. To my father I will be forever grateful for many valuable lessons and gifts, not the least of which was his encouragement to me when I was a young teenager to pursue photography. To Judy Graziosi, I owe much gratitude for her patience and competent graphic design assistance.

Finally, I honor the hundreds of thousands of Americans experiencing homelessness, many of whom, despite all odds, seek to remain resilient, hopeful, and open hearted. May God bless them all, and may those of us fortunate enough to have stable housing find the will and determination to press for changes in local, state and national housing policies that could improve their lives. Net proceeds from this book will be donated to non-profit organizations advocating for and serving Americans experiencing homelessness.

Mark Schumann Santa Fe, New MexicoIn many of the cities where I photographed, I was able to connect with local service providers to arrange interviews with persons housed in temporary shelters, and/or participating in recovery programs. Other interviews, nearly 100 in all, were conducted with persons who had slept unsheltered on sidewalks, in parks, and in wooded encampments. A few of their stories are presented here.

While in San Francisco, I woke up early one morning and slipped quietly out of the boarding-house-style bed and breakfast where I was staying in the Haight-Ashbury district. Approaching the intersection of Haight and Central on foot, I noticed a man sitting on the sidewalk. Unshaven, clothes dirty and wrinkled, he appeared to have had a rough night. As I approached, he glanced up at me and softly asked, “Do you have some tobacco?”

“No,” I replied, “I don’t smoke. But do you mind if I sit down here with you.”

“Help yourself,” he said. Making steady eye contact now, he seemed puzzled by my interest in him.

I said, “Do you mind if I ask if you spent the night on the street?”

As it appeared, he had slept outside, and he smelled of alcohol.

I gave him my name, and explained that I was traveling the country to document homelessness in America.

“Well, my name is Bill,” he said.

Over the next half hour, Bill and I shared a conversation touching on constitutional law, Calvinist theology, addiction, and finally on the struggles of the homeless.

“May I make a picture of you sitting here,” I asked.

He agreed. After making several images, I placed my camera back in my shoulder bag, pulled out my wallet, asked how much a pack of cigarettes cost in San Francisco, and handed Bill what he would need to buy a pack.

“Thank you,” he said, accepting the money from my hand.

“Goodbye, Bill,” I said, “Take care of yourself.”

Angie and I met in a conference room at The City Rescue Mission in Oklahoma City. Angie explained that she first used drugs when an older boy in her high school offered her a joint. “I was just 15 and so excited to be invited to do anything with anyone,” she remembered. “Then some older boys said, ‘We have something else. Do you want to try this? It will make you feel really good.’ That’s when it all began,” she remembered.

Many years later, in a violent relationship increasingly fueled by alcohol and methamphetamine, Angie resolved to make it on her own, so she moved out of her boyfriend’s home and rented an apartment.

Despite ongoing dependence on alcohol and meth, Angie mostly held things together on her own for a year. Then one day a convenience store clerk, concerned by Angie’s erratic behavior, called the police. During her four months in jail, Angie lost her job, her car, and her apartment. “Especially if you have a drug problem, leaving an abusive relationship can lead to homelessness,” Angie explained.

Even so, Angie felt relieved that the clerk called the police. “When I got out of jail, I went back to that store and thanked her,” she said.

By couch surfing with friends for the next year, Angie avoided sleeping on the streets or in shelters. But her failing another drug test led to a violation-of-probation charge, which resulted in her spending another 70 days in jail.

This time Angie won her freedom on the condition that she enter a residential drug-treatment program. Because her vision had deteriorated so, Angie could not keep up with the required readings. “I couldn’t do the reading, and I couldn’t get help for my cataracts as long as I was in rehab. So, the judge released me,” she said.

It took Angie five months to get funding for her surgery. In the meantime, she returned to using meth. When she failed another test, the judge ordered her back to jail unless she could get a treatment center to admit her that day. “The City Rescue Mission here in Oklahoma City agreed to accept me. Every other program had a three or four-day wait. I was so thankful to God, who plucked me out of that crazy behavior and put me here.”

Angie is following the Mission’s ten-month Bridge-to-Life recovery program. “Staying in this safe environment is giving me the chance to strengthen my faith,” she said.

After she completes the program, Angie plans to get a job so she can pay what she owes the state of Oklahoma in fines and probation fees. She is building a closer relationship with her 21-year-old son, and now wants to write a memoir offering hope to others struggling with addiction and domestic violence.

Many women experiencing homelessness have stories much like Angie’s. What I learned, though, as I conducted more interviews, is that the causes of homelessness are quite varied. Every person has traveled his or her own unique path.

“It can happen to you, too,” Charles said, as I interviewed him at a homeless services center in Orlando, Florida.

Charles said it was the looks on his children’s faces as they watched their mother beating him that finally moved him to file for divorce.

“We had many fights,” Charles said. “Once she took a knife to me, and I wound up with 58 stitches. My kids would ask, ‘Why don’t you defend yourself, Daddy?’ And I told them that a man doesn’t beat a woman.”

Fifteen years ago, when his daughter was two, and his son just an infant, Charles lost his eyesight for two days. Though he did not know it at the time, his vision loss signaled the onset of Type 2 diabetes.

With no health insurance, Charles did not seek medical help. One month later, things got worse. Charles remembered, “I was working 13 hours a day pouring concrete. We’d lost twins at birth and I was worried about the new baby. A month later I went into a diabetic coma for eight days. It stripped me of my energy. I’ve never been the same man.”

Because of his deteriorating health, Charles thought it best to give his wife power of attorney. When they separated eight years later, she sold both the home his grandparents had given him and the home he and his wife owned together. “She took our $20,000 in savings and our two kids. I just didn’t have the energy to put up a fight. I lived out of my car for five months before coming here to the Coalition.”

Charles recalled his desperation living unsheltered. Homelessness meant avoiding arrest for vagrancy, finding a place to shower, and trying to communicate without owning a phone. “It’s shocking how people treat each other on the street. They may have been decent people, but a couple of months out on the street turns them into something else.”

When Charles got to the Orlando Coalition for the Homeless, he was seething with anger. It took five months before he was emotionally able to participate fully in the shelter’s programs. “Finally,” he said, “I had to make a priority list of what needed doing to get my kids back. Their mother’s already been charged twice with neglect,” he said.

With training offered through the Coalition, Charles earned a private security license and now has a job. In a few months he plans to move into an apartment, and then to petition for custody of his children. “It’s like I’m rebooting myself,” he said. “Though when I leave here, I’m coming back to teach a class on how best to take advantage of all the shelter offers.”

Charles remembered once being at a gas station with only two dollars on him. A woman walked up to him and said, “Here’s five dollars. Put this in your tank.”

“She gave me that money out of her heart. I used to give money to homeless people, too, but in the spirit of, ‘Here, man,

take this and get away from me.’ Becoming homeless myself has changed my perspective. Some people are homeless for things they couldn’t do anything about. It can happen to you, too,” Charles said.

According to a count of the nation’s homeless conducted early in 2020 by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, on any given night nearly 600,000 Americans are experiencing homelessness. Sixty-one percent are sheltered, often in group shelters, or in temporary housing. The remaining 39 percent, some 226,000 persons, are on the street, sleeping on sidewalks, in parking garages, on park benches, in wooded areas, in abandoned buildings, or in vehicles. Some 100,000 Americans experiencing homelessness are under the age of eighteen, and 33 percent are in families with children.

Homeless counts, which had been declining since 2007, are again on the rise, and the problem is expected to worsen as more Americans face eviction. Alarmingly, chronic homelessness has increased 43 percent since 2016.

A common misconception is that most homeless persons are men, many of them with mental health challenges and addiction issues. In truth, more than 200,000 of the nation’s homeless, some 38 percent, are women. Though still a troubling statistic, homeless veterans now comprise just seven percent of the homeless population.

Service providers helping those experiencing homelessness point to the increasing gap between housing costs and wages as a primary contributor to the rise in homelessness. The top 20 percent of housing consumers in America make an average of $155,000 a year. Collectively, 19 percent of this group’s income goes toward housing. In stark contrast, the bottom 20 percent make an average of just over $10,000 a year, and are spending on average 89 percent of their income on housing.

Among comfortably housed Americans, there are those who struggle with alcoholism, substance abuse issues, mental health challenges, and/or who have made a poor decision or two in their lives. Advocates for persons experiencing homelessness contend that these afflictions and challenges are not the root cause. Homelessness, they say, will remain one of our nation’s most pressing social problems, unless and until significant and sustained investments are made in affordable housing.

The youngest of nine children, Lindsey was adopted at the age of eight by her maternal grandparents. Now 30, she lives with her three children in a Florida shelter for families.

“My father was out of the picture, living on the west coast. My mom was going to put me in foster care when my grandparents adopted me. They were there for me. My mom was not there for me, and I don’t want to be that kind of mom to my kids.”

The father of Lindsey’s first two children says he wants to be involved in their lives, but he is not helping to support them. He lost his driver’s license, and has been unable to keep a job. Lindsey agreed to share an apartment with her father. He had just moved back to Florida from the west coast, and Lindsey had separated from the father of her two older children. As a single mother with an 11-year-old boy and a 5-year-old girl, she was struggling to keep her apartment.

“My father just could not control his drinking. He finally totaled my car. That’s when things really began to unravel for us.”

Without a car, Lindsey had to spend $40 a day getting her children to and from school and getting herself to work at a grocery store. “No one wants to offer full-time jobs. I could only get part-time work.”

Lindsey’s father had agreed to cover the rent, but he was missing payments. Pregnant with her third child, estranged from her boyfriend, and facing eviction, Lindsey considered putting her baby up for adoption.

“It was hard enough trying to figure out how to take care of my oldest two children. I just didn’t see how I could care for a third. There is nothing worse than seeing your children hungry.”

Friends suggested Lindsey contact a local shelter for families. She moved in a year ago and was able to keep her baby, a girl now seven months old. She has her part-time job back at the grocery store, and she is working a second job in the shelter’s thrift store.

Following the guidelines of the shelter, she is saving 75 percent of her earnings. With that money, she hopes in a year to be able to afford to move with her three children into an apartment. Explaining why she dreams about owning a home, Lindsey said, “I don’t want my kids to have to move from place to place to place like I did.”

When she is not working or helping at the family shelter, Lindsey attends classes at a community college. She is on track to graduate in another year with an A.A. degree in medical information technology.

“I’m doing well in school, and my kids are, too. I shield them from the challenges I am going through and I try to keep them encouraged.”

The shelter has been helpful with transportation, clothing, Christmas gifts for the children, and arranging day care for her baby.

While in Sacramento, California, I met Rachel, who was sitting on a blanket in a park across the street from the state capital building. Rachel said she had been living in a tent since she and her boyfriend were evicted from a rental home two years earlier. “Most everybody is just a couple of paychecks away from being homeless,” she insisted.

They were both bartending when Rachel quit work to start classes at a culinary school. “Our boss kept warning Rob he would get fired if he continued to drink behind the bar. “One day my dad took me to lunch. When he brought me home, I saw my boyfriend’s car in the driveway. I found him passed out on the couch. He’d been fired all right.”

Evicted from their apartment, Rachel and Rob started sleeping under the freeway. “It is so depressing out here,” Rachel said. “When I get money I drink, but I do want to get better.” She has placed herself on the waiting list at four rehabs.

While Rob and she were sitting on a bench in a park in downtown Sacramento, he started hitting her. “He flips his switch when he’s drinking,” she said. “He was kicking me in the stomach. A friend who was with us called the cops. They arrested Rob, and I pressed charges. This is the second time he’s been arrested for beating me, so he’s going to be in jail for a while. I know I can’t be with him any longer.”

At age 40, Rachel has signs of liver damage. She thinks she could live with her father, but does not want to be a burden. Because she is still drinking, she can’t apply to a she lter. “I’m going to stay in my tent until I get a spot in a rehab,” she said.

David and I met at Camp Haven in Vero Beach, Florida. His long downward spiral from good health, strong family relationships, and business success to homelessness began when he picked up his first drink. “I struggled with heavy drinking most of my life,” he said. “Then 25 years ago I moved on to cocaine.”

From 2005 to 2010 David stayed clean and sober, and during that time his graphic design business in New York City grew. It all fell apart, though, after he relapsed on crack cocaine.

“Crack got its claws into me. I gave up my business in New York City and moved to Florida to be with my parents. I did well for a few months, but then I started using again.”

Repeated relapses, mental hospitals and jails followed. David kept trying and he kept failing. The core of his problem, he said, was an inability to be honest, and an inability to grow up.

Eventually he was caught shoplifting, later for altering a driver’s license, and finally for counterfeiting. “All to support my habit,” he said.

When out of jail, David would stay with his parents a while, then would get his own place. Every relapse, however, led to another arrest.

“At one point, I had my own apartment by the water, but spent my time closeted with drugs. It was horrible,” he remembered.

Unemployed and alienated from his parents and friends, David would sleep on the beach, or sometimes in a friend’s car. He spent days hanging out at the library. Near the end he sneaked into an old hotel, where he would sleep hidden behind a curtain in a conference room.

One night the owner of the hotel spotted him. “Probably he smelled me before he saw me,” David said. “He offered to let me sleep in one of the vacant rooms, but only because I told him I’d soon to be going to Camp Haven shelter for homeless men.”

A few days later, a bed opened up. David started participating in an intensive program of recovery. “We would meet every morning,” he said, “and would watch videos on spiritual development, employment, the psychology of addiction, and personal finance.”

David now sponsors newcomers in five different 12-step programs. “I grew up with money. I speak several languages, and have done a lot of travel. Still, I can relate to these men. Addiction is our common bond.”

At two-and-a-half years clean and sober, David runs a graphic design business from his apartment. His growing list of clients includes Camp Haven. There have been frustrations, though, in building his business. “Sometimes my past raises its ugly head. Some people still judge me by who I was.”

Every morning David gets together with his mother and father for coffee, and most evenings he joins them for dinner. “Every day they ask, ‘Are you coming over?’ They want to see me now every day. Every day!” he said with pride.

Early on in the project, I went to Los Angeles, and there visited The Midnight Mission located in the heart of Skid Row.

Within sight of downtown Los Angeles’ towering, silver skyscrapers live thousands of homeless men and women. They spend their days scavenging for meals, a drink, a drug fix, and sometimes all three. Many sleep in tents pitched on sidewalks, or in alleyways. In the heart of Skid Row, on the corner of San Pedro and East Sixth Street, stands The Midnight Mission, offering hope to those who are ready for help.

Halfway through my tour of The Midnight Mission, I met Carlos, a husky, clean-shaven gentleman, dressed in dark

slacks, a long-sleeved shirt and a tie. Carlos led me into a gymnasium-size room partitioned into eight by ten feet cubicles. Each cubical had a bed, a small desk and a dresser. “This,” he said, “is where I stay.” Only then did I realize he was not an employee of The Midnight Mission, but one of its 250 live-in clients.

There are many factors contributing to today’s coast-to-coast rise in homelessness. Chief among them is the scarcity of affordable housing. In Los Angeles, the smallest studio apartments start at $1,400 or more per month, making housing unaffordable, even for persons working minimum wage, full-time jobs. In addition, many among the street homeless also struggle with mental health issues, alcoholism, and drug addiction.

Adults tend to only be open to making major life changes when not changing becomes more painful. This is nowhere truer than among those struggling with addictions. To participate in one of The Midnight Mission’s programs, one must be sick and tired of being sick and tired. Carlos is one of them.

After showing me through the reception area, living quarters, kitchen, offices, and meeting rooms, Carlos took me to a quiet reception area. For the next thirty minutes, he told of the painful and grace-filled twists in his life. His spiral into alcoholism and cocaine abuse had led to unemployment, estrangement from family, and the loss of most of his friends. Unable to keep a job, Carlos could no longer afford to pay rent. That’s when, several years ago, he found himself living on the street.

By the age of 13, Carlos was addicted to cocaine. One year later he joined a gang. His drinking triggered rage, which led to struggles with teachers, and eventually to expulsion from high school. By the age of 17, Carlos was a high school dropout and an intravenous heroin user. He left home to share an apartment with friends who had also dropped out of school. He worked in fast food restaurants at minimum wage, got evicted more than once, made and lost friends, and had numerous short-term relationships with women. All the while, Carlos’ abuse of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin grew worse.

Despite his addictions, by his early 30’s Carlos was married and had two daughters and a son. Family obligations, though, did not keep him from disappearing for weeks, sleeping on sidewalks until his wife or parents found him and brought him home. Once his father discovered him huddled in a pile of old, smelly blankets. He was hungry, dirty, tired,

and drunk. “We love you, Carlos, and we are not giving up on you,” he recalled his father saying. But Carlos refused help.

Carlos drifted in and out of his wife and children’s lives. Longer and deeper relapses followed stints of sobriety. Finally, Carlos became a permanent “resident” of the streets. Estranged from his family, he learned survival skills that are now difficult for him to discuss.

The stress of living on the street, particularly coupled with alcohol or drug abuse, can trigger mental illness or make existing emotional problems worse. This was certainly true for Carlos, who wound up shuffling along the crowded sidewalks in Skid Row, talking to himself, while pushing a grocery cart full of his ragged belongings.

By the time Carlos was 50 years old, he had finally had enough. He allowed a friend to bring him to The Midnight Mission, where he entered the Life Recovery program. There he learned how to stay sober. He also learned life management skills, such as how to budget, make himself more valuable to employers, take care of his health, and nurture relationships. Carlos has now restored his relationships with his parents, his wife and his children. He is holding down a job as an assistant volunteer coordinator at The Midnight Mission, and he is hopeful about his future.

“I feel honored, and I feel privileged to be doing the job that I am doing, because I never would have thought,” voice breaking, “when I was a homeless bum that God would have me where I am at now, because I was of the hopeless, hopeless variety,” Carlos said.

Before a crowd of hundreds, and accompanied by his son, Carlos shared his story at The Midnight Mission’s annual fundraising dinner held in Beverly Hills. His is a story of estrangement and reconciliation, and of hope restored. Carlos is not alone. At the Midnight Mission, and at similar programs around the country, lives are being resurrected, proving that homelessness does not have to equal hopelessness.

On another trip to California, where some 27 percent of America’s homeless live, I met Sandy at the Navigation Center, a low-barrier shelter run by the City of San Francisco.

When Sandy was just three years old, her mother died. She went to live with her grandmother. “I know she did the best she could for me, but I didn’t get along with her that well. Our father had pulled a disappearing act. My brother and sisters lived with family members in different cities, so we didn’t see much of each other. I didn’t get along well with my grandmother. I felt so lonely.”

At age 15, Sandy was already drinking and using crack cocaine and pot. She quit school, left home, and moved in with a boyfriend ten years older than her. “I left him after three years because he was physically abusive,” she said. “There I was at 18, sleeping on sidewalks and benches, and in tents. Sometimes I’d stay in shelters, but not for long, because I didn’t want to quit using drugs. It was dangerous on the street. The few things I had were always being stolen. And I was hooking up with guys that didn’t mean me no good.”

Over the next ten years, Sandy plunged into one bad relationship after another, always with older addicts she’d met on the street. “I was hardly ever stable,” she said. “At twenty-five, I married the father of my six children. Now I have 11 grandchildren and a great grandbaby. I don’t see them much because they’re scattered all over the country.”

Up to a year ago, Sandy and her husband had been living in a tent under the freeway in west Oakland. Her aunt took them in but only for a month. “She put us out because he stole from her,” Sandy said. “I left him and got into a shelter for a few months then an apartment, but I soon lost it because of crack cocaine.”

After losing her apartment, Sandy moved across the bay to San Francisco, where she entered the Navigation Center, an unconventional shelter run by the city’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. Unlike most shelters, it serves singles and couples, welcomes pets, and has a relaxed policy on drug use. With some 4000 people living on the streets of San Francisco on any given night, city leaders are trying different approaches, like the Navigation Center, to get the chronically homeless connected to public benefits, health services, and shelter.

“Even though God has blessed me to be accepted here,” Sandy said, “I tell people that if you can find permanent housing, hold on to it with all your might. Pay your rent before you get high.”

More than half of all personal bankruptcies in the United States are due to unpaid medical bills. Often, bankruptcies lead to evictions, and eviction records make it more difficult for a person to pass landlord screening requirements going forward. Often, the health challenges that can lead to astronomical medical bills also result in missed time at work, lost income, and eventually job loss. And down and down the spiral goes. Rafael’s is such a story.

The year was 1980. Rafael remembers feeling both excited and fearful as he climbed aboard a 30-foot boat in the harbor in Mariel, Cuba, joining some 30 other refugees fleeing to the United States.

Then twenty years old, he had just spent three years in the Cuban army. “They were always bad-mouthing the United States, but I didn’t believe them. I wanted a better life.”

For Rafael, leaving Cuba meant separating from his girlfriend, whose father would not give her permission to go. “Leaving my parents was hard, too,” he said. “I’ll never forget them standing in the doorway waving goodbye.”

Rafael settled in Miami, where he got a job driving a truck for an electrical contractor. Within two years he was a certified union electrician, and three years later he married. He lived what he describes as a normal family life in a Cuban-America community in south Florida. “Sure,” he said, “I used some cocaine, drank, and smoked pot. But I had a wife and three daughters, so I kept it under control.”

At the age of 54, Rafael was electrocuted on the job. The accident left him unable to work, but he did not qualify for worker’s compensation benefits. His life began to spiral out of control. He started smoking marijuana heavily. Soon he went to jail. Six months later, when he was released from jail, his wife wanted a divorce.

For the next year, Rafael lived with one of his daughters, and later with cousins. Smoking pot and angering his hosts, he again found himself on the street. “It’s terrible out there,” he said. “There are mentally ill people, and too much drugs. People tried to rob me.”

Two years ago, at the invitation of a distant cousin, Rafael moved to San Francisco “I slept on his couch for a year,” he said. “But my cousin’s partner started complaining. I didn’t say anything. I just left. A few months later, my cousin saw me camped in the park. ‘Don’t worry,’ I told him. ‘I’m not going to die.’”

Rafael was surviving on what he calls a “slim” Social Security disability benefit, not enough to afford an apartment in San Francisco. Three months before I interviewed Rafael, a caseworker with the city’s Department of Homeless Services encouraged him to apply to the Navigation Center’s homeless shelter. There, he was assured, he could get regular meals, counseling, and legal and medical help.

Now 61, Rafael is saving what he can from his disability benefits, in order to move back to Miami to be close to his three daughters and one grandchild.

Angie, Charles, Rachel, David, Carlos, Sandy, and Rafael were just seven of nearly one-hundred persons who agreed to share their stories with me, and I am grateful to each of them for their time, candor, and honesty. It is with equal gratitude that I acknowledge those who helped arrange these interviews. Often, I would return to Santa Fe grateful for the selfless service being offered by thousands of homeless shelter works and other service providers across the country. I also often found myself saddened and depressed by the scope of the challenges they face, yet encouraged by the success and turn-around stories I heard.

- Mark SchumannAkron, Ohio

Chicago, Illinois

Portland, Oregon

Los Angeles, California

Cleveland, Ohio

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Denver, Colorado

Houston, Texas

Memphis, Tennessee

Seattle, Washington

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Portland, Maine

San Diego, California

Los Angeles, California

Chicago, Illinois

Denver, Colorado

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Chicago, Illinois

Cincinnati, Ohio

Detroit, Michigan

San Diego, California

Amarillo, Texas

Austin, Texas

Boulder, Colorado

Orlando, Florida

Los

San

Portland, Oregon

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Chicago, Illinois

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Tucson, Arizona

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Denver, Colorado

Portland, Oregon

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Detroit, Michigan

Oakland, California

Orlando, Florida

Atlanta, Georgia

Phoenix, Arizona

San

Oakland, California

Louisville, Kentucky

Sacramento, California

Columbus, Ohio

Louisville, Kentucky

San Diego, California

Phoenix, Arizona

San Diego, California

San Jose, California

Baltimore, Maryland

Chicago, Illinois

Seattle, Washington

Denver, Colorado

Savannah, Georgia

Akron, Ohio

Indianapolis, Indiana

San Jose, California

Burlington, Vermont

Amarillo, Texas

San Diego, California

Boulder, Colorado

Chicago, Illinois

Denver, Colorado

San Diego, California

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the expressed written permission of both the copyrighted owner and the publisher of this book.