Willie and Holcha in Africa

“In the autumn we,

(Holcha Krake)

will travel to

Africa, the Negro's own land. I yearn for Africa

and expect it to be the last inspiration that I need, and where I expect to find my true self, which is different from what other people say I am”

William H. Johnson. Kerteminde 1931. (Interview. Tidens Kvinder. Danish weekly magazine)

Cover: William H. Johnson: Landscape with Mosques, Tunis. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.857

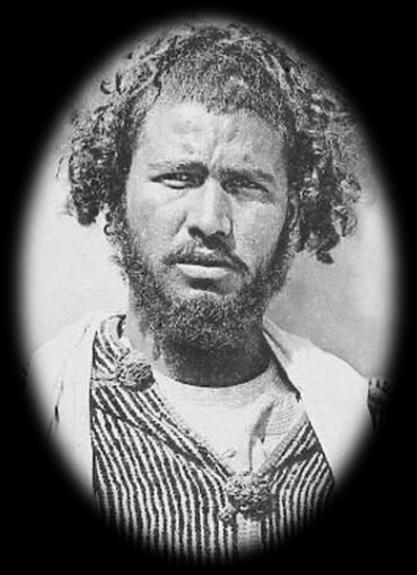

William H. Johnson at his studio in Kerteminde. Denmark. Ca 1931.

(Harmon foundation collection. National Archives and Records Administration)

William H. Johnson at his studio in Kerteminde. Denmark. Ca 1931.

(Harmon foundation collection. National Archives and Records Administration)

Introduction:

in April 1932, African-American painter William H. Johnson and his Danish wife, textile artist, Holcha Krake embarked on a journey to Tunisia in North Africa. On route from Denmark the couple visited Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium and finally France, where they took the train from Paris to Marseilles to board the ferry to Tunisia.

What followed was a three-month odyssey of exploration where the couple visited the capital Tūnis, studied indigenous Berber pottery and textiles at Nabeul and Kairouan and took expeditions to Sousse, Bardo and Hammamet. The couple both sketched on their tours, creating works that both captured the local North African people and Tunisia’s ancient architectural wonders.

Johnson was the first African American painter that explored Tunisia and perhaps influenced by renowned African-American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (18591937) whom Johnson had befriended in France. Tanner was captivated by the special light found in North Africa and had visited Algeria in 1908 and Morocco in 1912.

Photo of Willie and Holcha on the Atlantic crossing. Ca 1938. (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Photo of Willie and Holcha on the Atlantic crossing. Ca 1938. (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

French school map of Tunisia. 1938. Vidal La blache. mayflyvintage.co.uk

French school map of Tunisia. 1938. Vidal La blache. mayflyvintage.co.uk

Tunisia in the 1930s.

Tunisia is the northernmost country in Africa, bordered by Algeria and Libya. It was once a province of the Roman Empire, known as Africa Proconsularis (117–138 AD) Tunisia’s accessible Mediterranean Sea coastline and strategic location have attracted numerous conquerors and visitors through the ages, and its ready access to the Sahara has brought its people into contact with inhabitants of the African interior.

At the time of Johnson and Krake´s visit, travelling had become easier with the electric tramway built along the coast and buses going to rural areas. Yet mules and camels were still a popular form of transportation. In 1932, Tunisia was under French colonial rule (1881- 1956) which meant that Johnson and Krake could communicate within its French speaking societies. However, in rural areas, they had to rely on nonverbal interactions.

Although Tunisia had attracted many cosmopolitan travelers by the 1930s, Johnson and Krake gained access to sacred sites and areas otherwise not approachable for Tunisia’s European colonial population or other non-Muslim visitors. Krake recalls that she was personally invited to see the secret process of woven textile and Johnson, whom often was mistaken for a local, could sketch areas never seen by non-Muslim before.

Colonial France marketed Tunisia as an exotic and backwards destination, depicting the locals as unmodern and “primitive” Yet, for Johnson and Krake they found the locals to be highly intelligent and admired that they kept their heritage, traditions and customs intact for thousands of years.

Colorized photos from the capital Tunis. Ca 1899. ©Library of Congress

William H. Johnson. 1932

Indigenous Sufi man. Ca, 1900. Tunisia

Albanitorv. Odense

Colorized photos from the capital Tunis. Ca 1899. ©Library of Congress

William H. Johnson. 1932

Indigenous Sufi man. Ca, 1900. Tunisia

Albanitorv. Odense

Nabeul.

“Imagine a desert in springtime with a flowery carpet of ornamental plants, while the rain awakens the scent of the wet earth”

Holcha Krake´s description of Tunisia. Aarhus Newspaper. Denmark. 1934.

William H. Johnson, Poppy Fields, Africa, 1932. Smithsonian American Art Museum 1967.59.34.

William H. Johnson, Poppy Fields, Africa, 1932. Smithsonian American Art Museum 1967.59.34.

Nabeul, is a port town located in northeastern Tunisia, about 65km from the capital Tunis, and is an area of splendid coastlines, hills and fertile plains. Nabeul, which derives its name from the Greek “Neapolis” (new town), dates back at least 2400 years and is renowned to this day for its pottery and ceramics crafted by its indigenous Berbers artisans. During the Roman Empire the city was known for its production of pottery, especially the popular red terracotta clay pottery.

In a Danish interview from the 1934, Johnson recalls that upon arrival, the town only consisted of 36 Berber families, all keeping alive their ancient pottery tradition, handed down from generation to generation. Each family had their own Kiln for firing pottery and they collected clay from the nearby hills.

The Berbers were intrigued by both Johnson and Krake. Johnson’s hair and skin color was similar to theirs and he completely blended in when he wore their native attire. In Krakes case, it was her blue eyes and blond hair that first drew attention, and then her marriage and working companionship with a dark-skinned man. That was very unusual and it highly amused and delighted them.

Terracotta deity with lion's head representing Tanit. 1st Century BC. Nabeul Museum. Tanit was the mother goddess of fertility and worshipped by the Berber people of North Africa. Photo by Prof. Mortel.

Terracotta deity with lion's head representing Tanit. 1st Century BC. Nabeul Museum. Tanit was the mother goddess of fertility and worshipped by the Berber people of North Africa. Photo by Prof. Mortel.

Nabeul Berbers kneading clay by foot. C.1920s. (Collection of Faouzi Zitouna)

Nabeuls pottery industry dates back to Roman times. Leopard with jug. Mosaic. 5th century BC, Nabeul, Tunisia

Photo by Andreas Wolochow.

Holcha Krake. Ca 1920. (Steve Turner. Los Angeles)

Pottery workshop.Nabeul. Ca. 1920. (Collection of Faouzi Zitouna)

Nabeul Berbers kneading clay by foot. C.1920s. (Collection of Faouzi Zitouna)

Nabeuls pottery industry dates back to Roman times. Leopard with jug. Mosaic. 5th century BC, Nabeul, Tunisia

Photo by Andreas Wolochow.

Holcha Krake. Ca 1920. (Steve Turner. Los Angeles)

Pottery workshop.Nabeul. Ca. 1920. (Collection of Faouzi Zitouna)

Unlike most foreign visitors to the town, the couple was welcomed and invited to stay with a Berber artisan family. Johnson and Krake socialized with the whole town throughout their sojourn and was invited to a private traditional Berber wedding that lasted seven days. Johnson also recalls that one evening, he was lucky to witness the Berber men performing a primeval worship dance.

What Johnson observed was likely the ceremony known as “Stambeli” A Tunisian Indigenous trance dance created by the descendants of sub-Saharan slaves brought to Tunisia. It relates to the ancestral memory of those Africans who were displaced and enslaved. And its music calls upon spirits to heal humans through ritualized trance.

The area around Nabeul is also home to the oldest groups of Sufism. A mystical branch of Islam, whose ultimate aim is to seek the pleasure of God by returning to the primordial state known as “Fitra” The Sufis believe that humans were created in the most perfect form and were endowed with a primordial nature that left an everlasting imprint before they were sent to Earth's worldly realm.

Johnson was deeply intrigued by North Africa and its people. He lived and took part in the daily life of locals, all in the interest of making a direct personal connection with Africa. Their way of life impressed him as being closer to “art” than any cultivated societies he’s been in. And he was convinced that he understood the core of African art and culture in a way European artists never could.

As opposed to the likes of Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani whose “primitivism” was mostly inspired by African masks and artefacts, Johnsons “primitivism” was the result of an inward gaze, focusing less on the decorative value of African art and culture, but on the meaning or intent of the works and how they applied to him and the African American self.

“I have never met more genuine and dignified people than the fishermen in Kerteminde, and the Arabs. Those are the people who taught me the most”

“William

H. Johnson. Copenhagen, 1933 Christian Larsen gallery. Højbroplads

William H. Johnson North African Man. 1932. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.39

William H. Johnson. Sketch. Sufi elder. Ca 1932 Private photo.

Stambeli dance. Tunisia. Ca. 1910 (photo Eugène Chatelain)

H. Johnson. Copenhagen, 1933 Christian Larsen gallery. Højbroplads

William H. Johnson North African Man. 1932. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.39

William H. Johnson. Sketch. Sufi elder. Ca 1932 Private photo.

Stambeli dance. Tunisia. Ca. 1910 (photo Eugène Chatelain)

In Nabeul, Johnson and Krake were introduced to the Berbers traditional techniques in ceramics and was taught age-old secrets of glazing and firing. The Berbers showed them how they extracted pigments from crushed plants, rocks and minerals from the hills of Nabeul. And the couple brought home several kilos of powder for future use. For Berber artisans everything has a meaning and their culture encompasses a rich tapestry of spiritual beliefs that blend pre-Islamic traditions with Islamic influences. From ceramic, carpets to tile covered houses, the arts reflect the Berbers’ connection with nature, spirituality, and collective identity. Art does not only serve as decorative items; they also convey social messages and pays tribute to the divine power that governs all creation.

During the couples stay in Nabeul they learned how to do replicas of the ancient Berber ceramic patterns and their colors. But they also modified the designs and added their personal touch to them. Johnson recalls that when he showed the Berbers his and Krakes private ceramic pieces, they were astonished and awestricken. They had never seen their traditional patterns and colors used differently before. Nor had they ever thought of changing their traditional designs to something new.

Johnson and Krakes personal designs had, in a sense, launched the first new style to the town since antiquity.

The Yaz: Ancient Berber symbol, which means free person. Or liberation of Man from all his chains.

Chemla Peacock Eye Vases Nabeul. Private photo.

Johnson and Krake. Aarhus exhibition. 1934.

North African Mokhfia dish with linear mesh forms.

Photo: Luc de Laval Antiquités

Johnson and Krake. Aarhus exhibition. 1934.

Traditional Nabeul Terracotta Tea Set. Photo: bleunankin.Royan, France

William H. Johnson. Terracotta Tea Set. Private photo.

Chemla Peacock Eye Vases Nabeul. Private photo.

Johnson and Krake. Aarhus exhibition. 1934.

North African Mokhfia dish with linear mesh forms.

Photo: Luc de Laval Antiquités

Johnson and Krake. Aarhus exhibition. 1934.

Traditional Nabeul Terracotta Tea Set. Photo: bleunankin.Royan, France

William H. Johnson. Terracotta Tea Set. Private photo.

Tunisia:The Louvre Of Africa.

“When art has reached a certain stage, it will search for the primitive. And once it’s have absorbed enough, it will move forward, until it returns for its search for the primitive again. This is how I think it will always go in art. An eternal circle dance. “

William H. Johnson. Odense. 1932. (Exhibition interview at Albanytorv)

Head of a man. 100 A.D. Bardo, Tunisia.

Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Phoenician Bearded face. 400-200 BC. Tunisia. Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Phoenician mask. (7th-6th BCE) Carthage, Tunisia

Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Boy holding a dove. 3rd century BCE. Sousse. Tunisia. Photo: romeartlover.it

Head of a man. 100 A.D. Bardo, Tunisia.

Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Phoenician Bearded face. 400-200 BC. Tunisia. Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Phoenician mask. (7th-6th BCE) Carthage, Tunisia

Photo: Sadigh Gallery Ancient Art

Boy holding a dove. 3rd century BCE. Sousse. Tunisia. Photo: romeartlover.it

Some of the world’s greatest roman artifacts are located in Tunisia ever since it was once a prosperous Roman province, known as Africa Proconsularis (117–138 AD).

Krake recalls that she and Johnson sketched and copied motifs from the many mosaics they saw in Nabeul, Kairouan, Sousse and Hammamet. Krake often transferred designs and patterns from ancient ceramics to her textiles in the past. She was mainly fond of symbols taken from Greek and Egyptian mythology. The couple also spent time at “ The al-Matḥaf al-Waṭanī bi-Bārdū “ A museum located in Bardo, west of the capital Tunis. It was built in 1888 and houses one of the largest collections of Roman mosaics and sculptures in the world. The North African Roman mosaics are renowned for its large-scale figural compositions and more vibrant colours than their Italian counterparts.

Fighting men. 3rd Century A.D. Tunisia. Bardo. Roman Sea mosaic, 2nd-3rd century. Bardo

Photo credit: DeA Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

Boxing men 3rd Century A.D. Tunisia. Bardo

Mosaic from Carthage, Tunisia, 3rd Century.

Bardo Museum. Tunisia.

Leopards. 2nd-3rd century. Tunisia. Bardo.

Fighting men. 3rd Century A.D. Tunisia. Bardo. Roman Sea mosaic, 2nd-3rd century. Bardo

Photo credit: DeA Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

Boxing men 3rd Century A.D. Tunisia. Bardo

Mosaic from Carthage, Tunisia, 3rd Century.

Bardo Museum. Tunisia.

Leopards. 2nd-3rd century. Tunisia. Bardo.

Tunisian Sous-Verre Paintings:

A prelude for William H. Johnsons folk art style?

When Tunisia fell under French rule in 1881, the technique of reverse painting on glass, known as " Peinture Sous-Verre” began spreading in Northen Africa. This technique consists of painting on window glass in reverse order from the original project. The Sous-Verre trend later spread across the Sub-Saharan region in 1915 and became particularly popular in Senegal.

The circulation of Tunisian reverse glass paintings flourished between the 1910s and the 1950s. The artist Paul Klee, noted in his diary that he brought home several Sous-Verre works he purchased at the souks in Tunisia 1914.

Normally, Muslim tradition prohibits figurative art, but in Tunisia it was accepted for local artisans to portray myths, heroic characters and local Sufi saints. The paintings were favoured among the local population of Tunisia who now could buy inexpensive portraits of their spiritual guides and used as a contemplative device in their homes

Early 20th century Tunisian Sous-Verre painting is characterized by its flattened figures surrounded by bold colors. Their simplified style acted as replacement for words for the illiterate. Whether Johnson was directly inspired by them is unknown, but it’s interesting to see the many similarities in color use and the naive style that Johnson consciously used in his paintings from 1938-1947.

Khalid ibn al-Walid. Arab commander. 20th C. Tunisia. (Collection of Mohamed Hamdane.)

The Sacrifice of Abraham. Late 19th century. Tunisia. (Collection of Mohamed Hamdane.)

Depiction of Imam Ali. Muslim Caliph. 20th C. Tunisia. (Collection of Mohamed Hamdane.)

William H. Johnson. Li'L Sis, 1944. Smithsonian Art Museum. 1967.59.1023

William H. Johnson Little Girl in Orange, ca. 1944 Smithsonian Art Museum. 1967.59.1007

William H. Johnson, King Ibn Saud ca 1944. Smithsonian Art Museum. 1967.59.661

The Holy City of Kairouan.

William H. Johnson Great Mosque of Kairouan, Africa, 1932.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.12

William H. Johnson Great Mosque of Kairouan, Africa, 1932.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.12

When the famous Swiss-born German artist Paul Klee entered the city of Kairouan in April 1914 he wrote in his diary “ Color possesses me. I don’t have to pursue it. Color and I are one. I am a painter.” He left Tunisia shortly after, explaining: "I had to leave to regain my senses."

Johnson and Krake might have been aware of the 1914 Tunisian journey made by Paul Klee together with fellow artists, August Macke and Louis Moilliet. Like the Swiss-German avant-garde group they also chose to stay in Kairouan, Sousse, and Hammamet.

The holy city of Kairouan is similar to an open-air museum for its richness and diversity. Every corner and every place contain abundance of ancient history. Located in the center of Tunisia in a plain at an almost equal distance from the sea and the mountain. Kairouan is defined as the holiest city of Tunisia, having the oldest mosque in North Africa and the world’s oldest minaret.

View over Kairouan. Photo: tunisienumerique.com

Paul Klee. Kairouan. 1914. Christie's. NY. Nov 17.2016

William. H. Johnson. Kairouan. Ca.1932. Private photo.

View over Kairouan. Photo: tunisienumerique.com

Paul Klee. Kairouan. 1914. Christie's. NY. Nov 17.2016

William. H. Johnson. Kairouan. Ca.1932. Private photo.

As Johnson could blend in with the locals, he was able to enter areas that had been closed to non-Muslim visitors throughout much of its history. He was invited inside the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Mosque of Uqba), the oldest Mosque in North Africa. He visited the mosque and mausoleum, Zaouia Of Sidi Sahab ( Mosque of the Barber). One of the finest Islamic buildings in Tunisia. Johnson also explored the narrow alleys of Kairouan’s ancient medina and did several sketches from the area.

Johnson recalls that he and Holcha climbed up the minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan which stands 31.5 meters tall and is the oldest in the world. There they saw a spectacular view of the desert with camel caravans coming from all directions. The caravans all stopped at the foot of the mosque and the merchants spread all their colorful merchandise in the street. They could hear them barter their goods all day until they disappeared back into the desert in the early morning.

Photo

(Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Holcha Krake and William H. Johnson at La Grance Place in Kairouan. 1932. collage assembled by the Harmon Foundation 1957.

William H. Johnsons watercolor sketches from Kairouan 1932.

The Prayer Hall, Mosque of Kairouan Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.79R-V

Photo: Mary Evans

The Sidi Abid al-Ghariani Mausoleum. Kairouan Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.79R-V

Photo: Natalie Tepper

Kairouan – The Grande Rue and the Mosques. Smithsonian American Art Museum- 1967.59.847

Photo: Giovanni Camici

William H. Johnsons watercolor sketches from Kairouan 1932.

The Prayer Hall, Mosque of Kairouan Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.79R-V

Photo: Mary Evans

The Sidi Abid al-Ghariani Mausoleum. Kairouan Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.79R-V

Photo: Natalie Tepper

Kairouan – The Grande Rue and the Mosques. Smithsonian American Art Museum- 1967.59.847

Photo: Giovanni Camici

In Kairouan, Krake studied the manufacturing process done by craftsmen and women in the carpet workshops. Kairouan is known as the ‘CapitalofCarpets ’, as these are its main craft product. It is also renowned for its manufacture of silk, cotton and linen fabrics since the 8th century.

She was introduced to the pre-Islamic traditional industry of carpet weaving that was based on the fabric of the "mergoums" and "kilims, where local hand spun wool and natural dyes are used.

As a young textile student, Krake had copied designs from Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection in Berlin, and her textiles were influenced by her interest in ancient cultures. She believed that the past was a model for aesthetic renewal, so the visit to Kairouan must have been an exciting experience.

Krake was especially intrigued by the similarities in the patterns she recognized from old Nordic textiles. In the early 9th to 10th centuries, North African textiles were introduced to Scandinavia by Viking merchants. When Scandinavians themselves started to produce rugs, their designs were influenced by the oriental design.

Traditional Hand knotted Kairouan rug. Textile found at the Norwegian Viking ship, Oseberg. AD 820. Photo: Vikingeskibsmuseet. Oslo.

Traditional Hand knotted Kairouan rug. Textile found at the Norwegian Viking ship, Oseberg. AD 820. Photo: Vikingeskibsmuseet. Oslo.

Holcha Krake with her carpets inspired by her travels in Tunisia. Aarhus Art Exhibition. Denmark. 1934.

A woman weaves a carpet. Kairouan 1934.

Photo: Picture alliance Arkiv

Holcha Krake. Tribal Kilim Rug. Ca 1932-1938 Private photo.

Holcha Krake with her carpets inspired by her travels in Tunisia. Aarhus Art Exhibition. Denmark. 1934.

A woman weaves a carpet. Kairouan 1934.

Photo: Picture alliance Arkiv

Holcha Krake. Tribal Kilim Rug. Ca 1932-1938 Private photo.

Holcha Krake´s watercolors of indigenous people Tunisia. North Africa. 1932. Courtesy of Thom Pegg. Click link to see more works by Holcha Krake and Johnson

https://issuu.com/msmodular72/docs/willie_and_holcha_pages

Excursions to Hammamet and Sousse.

Sousse and Hammamet are two ancient coastal towns located about 97,3 km from each other. Hammamet is located about 15 km from Nabeul and would have been a short bus ride for Krake and Johnson to take.

The area is known as the "jewel of the coast" and famous for its long beaches and roman ruins of amphitheaters and thermal baths. With the old electric tramway along the coast that was in function until 1960, visiting the many coastal towns was uncomplicated and cheap.

Holcha Krake recalls that during a stay at Hammamet, she and Johnson was invited by the locals inside a private home and shown their hand-woven wools, tapestries and pottery. African-American painter, Hale Woodruff (1900 - 1980) did short series of watercolors from Hammamet in 1930 – Yet he never visited Tunisia and painted them from his residence in Cagnes-sur-Mer. France

Beach at the Medina walls. Hammamet.1930

Indigenous sculptures. Sousse.

The Tunisian tramway seen along the coast

Hale Woodruff. Hammamet, Tunisia. 1930. Swann Galleries. Feb 16, 2012.

Beach at the Medina walls. Hammamet.1930

Indigenous sculptures. Sousse.

The Tunisian tramway seen along the coast

Hale Woodruff. Hammamet, Tunisia. 1930. Swann Galleries. Feb 16, 2012.

Return to Denmark: Ceramic exhibitions.

Johnson and Krake. Blomqvist Gallery. Oslo. Norway. 1935

Johnson and Krake. Blomqvist Gallery. Oslo. Norway. 1935

November-December. 1934.

Holcha Krake and William H Johnsons exhibition. Aarhus Art Building. Denmark.In June 1932, Johnson and Krake returned to Denmark. On route home they spent 3 weeks in France where they visited a ceramics museum in Martigues and visited Henry Ossawa Tanner at his studio in Paris. When back in Kerteminde, the couple decides to move from Gasværksvej into a larger house and studio at Skovejen.

First Ceramic exhibitions.

Four months after their trip to Tunisia, they debuted their ceramic pieces at the local library in Kerteminde on October 1932. Neither Johnson nor Krake had worked or shown ceramics prior to their Tunisian trip and the exhibition was given high praise.

In November, Holcha arranges a larger exhibition with their ceramic works at Hotel Brockmann at Albanytorv in Odense. The Odense show was so successful, that it was prolonged into December.

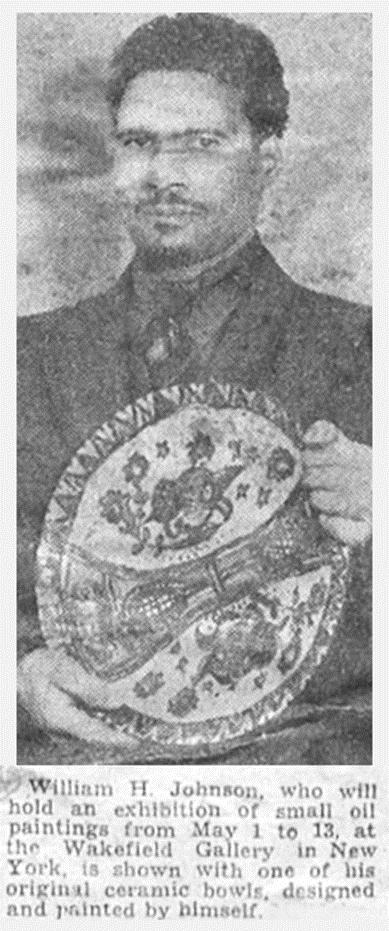

Danish reviews of the couple's exhibitions in 1932 state that they exhibited vases, dishes, tiles, bowls, and ashtrays that they both had created, and praised Johnson for being a fine ceramist. It is also mentioned that Johnson had done much of the hand painted designs on Krakes ceramic works.

In 1933 and 1934, the couple includes their ceramics to their larger joint shows in Copenhagen and Aarhus. Here, Johnson was especially praised for the colors and brushstrokes he used on the surface of his ceramic, who all had the hallmarks of his expressionist oil paintings. Both shows were very well visited and records show that many ceramics and textiles were sold. In 1937, the couple participated in a group show with Swedish ceramic artists, Allan Ebeling and Gunnar Nordborg in Västerås and Gävle and Stockholm.

Show announcement. Hotel Brockmann, Albanytorv, Odense. Denmark. NovemberDecember. 1932.

Quote from the show:

” Johnson is not just a peculiar painter; he is also a fine ceramist. The couple has studied the ceramics of the north Africa, and produced vases, plates, ashtrays, bowls and more”.

Exhibition. Weaving, Painting and Ceramics. Kerteminde Library. Denmark. October. 1932.

Quote from the show:

” Mr. Johson is also a ceramist and together with his wife they have produced something significant. Oriental ceramics”

Quote from the show:

” She exhibits ceramics and woven works and he exhibits paintings and ceramics “

Hotel Brockmann, Albanytorv, Odense. Christian Larsen gallery at hojbroplads. Copenhagen 1933.Record shows that Krake continued to exhibit her ceramic pieces throughout the 1930s and 40s until she passed away from breast cancer in January 1944. In Johnsons case, his ceramic pieces are mentioned in Danish reviews from 1932-1934, a Norwegian review from 1936, a Danish review from 1938 and then finally in December 1944 at the Marquie Gallery in New York.

For Johnson, his ceramic pieces seam to correlate with the dramatic expressionist paintings he made from the period 1932-1938. Which were done in heavy impasto giving the impression of "wet clay."

As Johnsons works in ceramics are so scare and mentioned much less than Krakes pieces, it’s difficult to determine whether it was a brief personal experiment for him or a new endeavor Johnson began making experimental block prints the same year he started doing ceramics. The block prints were a media he chose to make his otherwise expensive art accessible to a wider public.

Perhaps he chose block prints over ceramics as they were faster to produce. It is also conceivable that due to the fragile nature of ceramics, they didn’t survive when they were put in storage in 1947 as he entered the Central Islip State Hospital, where he died in 1970.

Thus far, Johnsons few surviving ceramics have only been found in Denmark.

Holcha Krake. Tile design. Ca. 1932.

Private photo.

William H. Johnson. Design with Color Notations, Ca. 1935. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.465

Holcha Krake. Tile design. Ca. 1932.

Private photo.

William H. Johnson. Design with Color Notations, Ca. 1935. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.465

Show announcement. Wakefield Gallery, New York. May 1944.(Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Show announcement. The Artists Gallery. New York. 1938 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Show announcement. Marquie Gallery. New York. December. 1944 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

After their travels to North Africa, Johnson and Krake had 15 joint shows in Scandinavia and three in New York Ceramic works were included in the majority of them.

Denmark:

1932. October. Kerteminde Library

1932. November-December. Hotel Brockmann at Albanytorv in Odense

1933. November. Christian Larsen gallery in Copenhagen.

1933. Vestergade 82 in Odense.

1934. November-December. Esbjerg Library

1934. November-December. Aarhus Art Building.

1938. October. Filosoffen in Odense

Norway:

1935. Uppheim. Volda

1936. Afholdshjemmet. Aalesund

1937. Kunstlageret på handelsskolen. Volda

1937. September. Kunstforeningen Trondheim.

1937. Handicraft society. Tromsø

Sweden:

1937. Group show with Swedish ceramic artists, Allan Ebeling and Gunnar Nordborg in Västerås and Gävle and Masshallen, Stockholm.

United States:

1938. The Artists Gallery. New York.

1944. May. Wakefield Bookshop Gallery

1944. December Marquie Gallery.

Holcha Krake. Dish with bird design. Ca. 1932. Kerteminde museum.

William H Johnson. Arabian leopard. Plaster sculpture. Ca.1932-1938. ( Private collection)

Holcha Krake. Splash glazed dish with tribal Berber patterns. Ca. 1932-1938.( Private collection)

William H Johnson. Stoneware bowl modelled in an organic shape Ca.1932-1938.( Private collection)

William H. Johnson. Splash Glazed Tea Set Ca. 1932-1938. ( Private collection)

Holcha Krake, Fish Design for a Ceramic Plate, ca. 1930-1939 Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.1158

Holcha Krake. Dish with bird design. Ca. 1932. Kerteminde museum.

William H Johnson. Arabian leopard. Plaster sculpture. Ca.1932-1938. ( Private collection)

Holcha Krake. Splash glazed dish with tribal Berber patterns. Ca. 1932-1938.( Private collection)

William H Johnson. Stoneware bowl modelled in an organic shape Ca.1932-1938.( Private collection)

William H. Johnson. Splash Glazed Tea Set Ca. 1932-1938. ( Private collection)

Holcha Krake, Fish Design for a Ceramic Plate, ca. 1930-1939 Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1967.59.1158

Reference Sources:

Manai, A. (2007). British travellers in Tunisa, 1800-1930: a history of encounters and representations. Tunisia: Centre for University Press.

Clara Ilham Álvarez Dopico. North African Crafts under Colonial Status, c. 1900: The Case of Pottery in Tunisia and Algeria

Guernier, E., Froment-Guieysse, G. (1948). L'Encyclopédie coloniale et maritime: Tunisie. France: Encyclopédie de l'Empire Français.

Meisl, K. (1998). "Naermere solen" Holcha og William H. Johnsons liv. Denmark: Johannes Larsen Museet.

Turner, Steve and Victoria Dailey, WILLIAM H. JOHNSON: TRUTH BE TOLD. Los Angeles, 1998.

Powell, Richard J. HOMECOMING: THE ART AND LIFE OF WILLIAM H. JOHNSON. Washington, 1991. Sieglinde Lemke. Primitivist Modernism: Black Culture and the Origins of Transatlantic Modernism.

Le Voyage en Tunisie 1914 - Paul Klee August Macke Louis Moilliet /franCais

Breeskin, A. D. (1982). William H. Johnson: The Scandinavian Years : September 17-November 28, 1982.

T. Cook. The Traveller's Handbook for Algeria and Tunisia. (1913). United Kingdom:

Spencer, W. (1967). The Land and People of Tunisia. United States: Lippincott.

About the author, J.L Rydeng

Josephine Rydeng is an art dealer and apprasier, based in Copenhagen, Denmark. She works with with her father, Hans Rydeng at Obro Art gallery, and is the 4th generation of her family to work in the industry, following in the footsteps of her grandfather, Leif, who was a well-known painter of birdlife in his own right, and her great grandfather, N.P.Rydeng, who established the familys business by opening the gallery in 1905. Josephine specialises in scandinavian fine art, female painters and American artists working in Scandinavia. Josephine grew up in Copenhagen to with her Father, Hans, and her mother Aicha, who is north-African, from the Berber tribes of the Atlas mountains, who herself was the daugher of a artisan potter.

Life is beautiful. And the greatest art, in my opinion, is the art of living. Life is new and strange every day. For me, tomorrow is always the best day.”

William H. Johnson. Copenhagen, 1933.William H. Johnson, Study of an African Girl, Tunisia 1932. Smithsonian American Art Museum 1967.59