An Essay On The Danish Artist Who Shaped William H. Johnson’s World.

By Josephine Rydeng. 2025.

Holcha Krake (1885-1944)

Holcha Krake was a pioneering Danish teacher, textile artist, ceramist and watercolorist whose career bridged Nordic folk traditions and modernist art movements. She was only fifteen as the 20th century began, yet was already educated and notably independent. In her short life, she experienced firsthand the European avant-garde art scene in 1920s Paris and Berlin. Met with famous artists like Edvard Munch, and Henry Ossawa Tanner and lived through the Harlem Renaissance In New York.

Her marriage to African-American painter William H. Johnson created a crosscultural partnership that influenced both artists’ lives and work, establishing Krake as a significant yet still under-recognized figure in early 20th-century art. Krake’s life and contributions have often been overshadowed by the towering legacy of Johnson. However, her role as both an artist and a catalyst in Johnson’s life and work cannot be understated. She brought to their partnership a wealth of cultural knowledge, artistic skill, and emotional support that profoundly shaped Johnson’s creative journey.

Holcha Krake, was born Holcha Martha Sørensen on the April 6th, 1885, in Karlby Sogn, in Jutland, Denmark, and raised in a family dedicated to education. Her parents, both educators, fostered a home that valued progressive learning, creativity, and curiosity, profoundly shaping Holcha and her three younger siblings, Niels, Nanna and Erna. In 1891, when Krake was six, the family moved to Dalby on the Hindsholm peninsula in Funen, where her father, Søren Martin Sørensen, became headmaster of Dalby Friskole (Dalby Free School), the world’s oldest free school, founded by Christen Kold in 1852.

Søren Martin Sørensen embraced the educational philosophies of Christen Kold (1816–1870) and N.F.S. Grundtvig (1783–1872), which emphasized imagination and creativity as essential to children’s development. Rejecting the strict discipline and rote memorization that had dominated education, Sørensen criticized such methods as "dead knowledge," advocating instead for education that connected to real life and encouraged lifelong learning.

Krake and her siblings all grew up on the Dalby school campus, which later included a teacher training college. By the age of 16, as recorded in the 1901 census, Krake was already working as a school teacher, a testament to her early immersion in the educational ideals her family championed.

Krake’s formative years also included time in Norway through a cultural exchange program that facilitated the movement of young teachers and intellectuals across Nordic countries. During this period, she lived in rural Norway, serving as a governess for Principal Hendrik Kaarstad at Volda College of Teacher Education and staying with Olav Riste, co-owner of the Volda gymnasium. Volda’s rich cultural heritage and its people deeply influenced Krake, who came to regard Volda as her second home.

Dalby Friskole, founded in 1852. Holcha Sørensen and her family would have lived in the building to the right, which housed accommodations for teachers and their families. (Dalby Sogns Lokalhistoriske Arkiv)

A young Holcha Sørensen around the year 1900. Nicknamed "Lille Søren" (Credit: Christoph Voll estate collection. Per Mossin. Danmarks Radio 1983)

This 1898 photograph shows pupils and teachers from Dalby Friskole. The circled individuals are believed to be Holcha’s parents, Søren and Thora. (Credit. Dalby Lokahistoriske Arkiv.)

An account of Dalby Friskol Headmaster, Mr. Sørensen.

In 1905, Hans Schierbeck, a 23-year-old student from Copenhagen, embarked on a month-long journey through rural Denmark. The purpose of his trip was to gather material of cultural and historical interest related to old Nordic folk dances, costumes, and melodies. One of the highlights of Schierbeck’s journey was his visit to Dalby Friskol (Dalby Free School), situated on the Hindsholm peninsula in Funen. His diary entry from this visit vividly captures the atmosphere of the school and its surroundings:

Hindsholm is a genuine Funen landscape fertile, with living fences, friendly villages, white churches, and small forests filled with cornflowers, mullein flowers and poppies. Everywhere, water gushes forth the Odense Fjord, the Kattegat Sea, and the Great Belt Strait. The inhabitants at Dalby Free School were lively and festive, a spirit also reflected in their traditional dances and folk costumes.

My host, Schoolteacher Sørensen, with whom I enjoyed much hospitality, was incredibly helpful in every way. He even accompanied me as I visited many of the residents. The weather was beautiful, and overall, the days I spent on Hindsholm stand out as some of the most enjoyable of my trip.

I lived comfortably, albeit somewhat primitively, at a place known as “Line ved Kirken,” a former college boarding house near the parish church. However, I quickly felt at ease in the charming and picturesque surroundings, and for this, I owe my deepest thanks to Schoolteacher Sørensen and his amiable daughters, who even danced for me.

Schierbeck’s account paints a vivid picture of the cultural vibrancy of Dalby Free School under the leadership of Søren Martin Sørensen. His hospitality and engagement with Schierbeck’s project not only highlight the openness of the community but also demonstrate the school’s role as a living repository of Denmark’s folk traditions.

Krake's father, Headmaster, Søren Martin Sørensen, 1905. (1860–1910)

Credit: Rieber Christensen, Dalby.

Krake’s mother, Educator Thora Mikkelsen Sørensen, 1941 (1868–1949)

Courtesy of Christoph Voll estate collection.

The Danish free schools sought to preserve the fading culture of farming communities by standardizing traditional folk dances and emphasizing regional costumes. These practices gave students a deeper connection to Danish heritage, teaching folk tales and cultural values through movement, music, and visual symbols. This effort fostered pride in rural traditions and ensured their continuity for future generations.

Askov Højskole

From 1908 to 1910, Krake attended the Askov Højskole in southern Jutland where she took the College Teacher’s Course, an experience that would leave an indelible mark on her outlook and values.

Askov Højskole, founded in 1865, was deeply rooted in the educational philosophy of N.F.S. Grundtvig, emphasizing fellowship, community, and the integration of academic learning with practical, communal living. It was a school designed for adult students, offering an extended range of subjects to those who had already attended traditional high schools. The school’s boarding system, which encouraged students to live, learn, and dine alongside their teachers and their families, created a close-knit, egalitarian atmosphere.

Askov Højskole attracted a variety of highly respected educators and cultural figures who enriched the learning environment. Among them was Poul la Cour, a physicist and inventor whose work influenced Denmark’s energy policies, and Martin Andersen Nexø, the celebrated writer known for his seminal works like Pelle the Conqueror. Perhaps most notably, during Holcha’s studies, was Selma Lagerlöf, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, who visited the school in 1909. These encounters exposed Holcha to a vibrant intellectual and artistic community, inspiring her own journey as a culturally engaged individual.

Around 1910, Askov Højskole hosted approximately 250 students, many hailing from countries as distant as Norway and Iceland. This international representation gave Holcha access to a wide array of perspectives and fostered a deep appreciation for cross-cultural exchange. The school’s emphasis on fellowship extended beyond academics, with students actively participating in theatre productions, concerts, communal singing, and dining, experiences that highlighted the importance of shared creativity and collaboration.

Campus layout of Askov Højskole. A mix of academic, residential, and recreational spaces

This group photograph, taken at Askov Højskole in 1908, features teacher Knud Andersen surrounded by his class of 14 young women, embodying the ethos of the folk high school movement. Holcha, circled in the upper center, is a prominent figure among her peers. Credit: Askov Fotograferne, Vejen Lokalarkiv.

Credit: Askov Fotograferne, Vejen Lokalarkiv.

This photograph from Askov Højskole in 1910 captures four young women performing in costume, embodying the creativity and cultural exploration fostered by the folk high school movement.

Their theatrical attire and poses suggest a light-hearted performance, likely inspired by Danish folk traditions. Performances like this reflect the Grundtvigian ideals of education and the celebration of cultural heritage.

Family.

Holcha was not the only member of her family to be influenced by her parents’ unique upbringing. Her three siblings each pursued creative and educational paths that reflected their parents’ progressive values.

Niels Hagbard Sørensen born 1886, received schoolteacher training at Dalby Friskole as a young boy, then trained as a carpenter at Askov Højskole in 1906. He later took the teacher's examination at Skaarup Seminary and became a headmaster at the Rynkeby Friskole, a free school like the Dalby Friskole. There he continued to advocate for progressive teaching methods until he died of a sudden illness at the age of 48 in 1934.

Nanna Sørensen born 1889, showed talent and a passion for playing the piano and began to receive piano lessons at the age of 6. She became a student of the Royal court pianist Miss Johanne Stockmarr and travelled to Paris and Germany where she studied at the Academy of Music in Dresden and was a pupil of Lula Mysz-Gmeiner at the Academy of Music in Berlin. Except for the years abroad, Nanna Krake worked as a pianist and music teacher in Odense until her death in 1968.

Erna Sørensen born 1897, the youngest of the siblings, left Denmark at age 19 to pursued a career in visual arts. She becomes a pupil of the famous GermanAustrian expressionist painter, Oskar Kokoschka at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden. Through Kokoschka, she is introduced to great German artists such as Otto Dix and Conrad Felixmüller, who are active in the Sezessionsgruppe 1919 association. Among the members was Christoph Voll, a promising sculptor from Munich that she falls in love with and marries in 1922. From then on, Erna dedicates herself completely to her husband's work and career and the upbringing of their daughter Karen born in 1924.

Erna and Christoph Voll. 1923.

Courtesy of Christoph Voll estate collection

Pianist Nanna Sørensen

Credit: Odense Amtsraadskreds. Bind 13.

Teacher Niels Hagbard with pupils at Rynkeby school in 1922. Credit: C.I.Jensen, Odense. Ringe lokalhistoriske Arkiv

A Name Change: From Sørensen to Krake

In 1910, Holcha’s father, Søren Sørensen, passed away unexpectedly at the age of 50. Following his death, Holcha’s mother continued her work as an educator and housemother at Dalby Friskole until 1915, when she decided to move to Odense with her three daughters. That same year, the family made the significant decision to change their surname from Sørensen to Krake.

Holcha later revealed in interviews that the name Krake was inspired by the legendary Danish king, Rolf Krake. This choice was likely influenced by the poem Sol er Oppe, written in 1817 by N.F.S. Grundtvig (1783–1872), whose educational philosophies both of Holcha’s parents deeply admired. Sol er Oppe is a retelling of the Nordic heroic tale of Rolf Krake, a legendary Danish king whose story dates back to around the year 1000. In 1866, the poem was adapted into a song and published in the Folk High School Songbook, where it became a staple in Nordic free schools.

At the time, choosing a surname that departed from the conventional “-sen” suffix (such as Sørensen or Jensen) reflected a growing cultural revival in Scandinavia. By adopting the name “Krake,” Holcha’s family embraced this movement, selecting a name that was distinctly Danish and steeped in historical and cultural significance. In Grundtvig’s poem, Rolf Krake represented more than a legendary figure; he symbolized a bridge between the ancient and the contemporary, embodying virtues such as loyalty, courage, and community spirit.

For Holcha and her siblings, all of whom pursued careers in the arts, the name “Krake” not only set them apart but also underscored their connection to Denmark’s rich cultural heritage. The name served as both an homage to their family’s values and a reflection of their shared artistic and cultural aspirations.

Viking burial mound at Rolfsted on Funen. Legend says its the final resting place of Rolf Krake. Image credit: Rolfsted Sogns Lokalhistoriske Arkiv.

The legendary Danish King Rolf Krake escapes the Swedish King Adils and his men (Engraving by Swedish artist Södergren, 1852. SMK)

The Danish Genealogical Institute has granted formal permission for music teacher Miss Nanna Sørensen and teacher Miss Holcha Sørensen to officially adopt the surname, Krake. Folkets Avis newspaper on 17. august 1915.

Krake, with her mother, Thora, and her sisters, Nanna and Erna, enjoying a day at the beach. Courtesy of Christoph Voll estate collection.

Art Education and study tours.

Krake’s journey in the decorative arts began as a young girl designing embroidery patterns. When she couldn’t find textiles she liked, she started creating her own hand-painted fabrics. Her unique designs attracted interest, encouraging her to pursue a deeper understanding of textile arts through selfstudy and mentorship.

Krake took her first professional step in art weaving under the guidance of the renowned teacher and textile artist Jenny La Cour, who ran a textile school in a house called Veum , located on the Askov school campus where holcha was studying. For many years, the Askov textile school served as a pioneering institution for the spread of handicraft in Denmark and known for its first-class woven fabrics.

Krake then applied for the Husflidsselskabet's Weaving School in Copenhagen, which was established in 1913 as a counterpart to Jenny la Cours weaving school in Askov. There Krake studied under professor Anton Rosen whom also was the head of the Danish Arts and Crafts School for Women. The main production of the weaving school in Copenhagen were furniture fabrics, but also fabrics for curtains, cushions and clothing. The customers were both public and private institutions, and the weaving room's fabrics were often praised at domestic and foreign exhibitions.

One of Krake’s first significant solo projects was a replica of the tapestry for the chair of King Christian IV of Denmark and Norway (1577-1648). The replica captured the detailed patterns and colors of the original tapestry, honouring the legacy of Danish royal heritage. Her completed tapestry was exhibited at the Kunstindustrimuseet (Danish Design Museum) in Copenhagen, where it attracted significant attention and praise. The director of the museum, Vilhelm Slomann, was so impressed by her skill and dedication that he reached out to her personally, offering her a travel scholarship to continue her studies abroad. Which she used to study in France for six months.

Early travels.

Holcha Krake spent much of the early 1900s traveling across Europe on scholarships, a period she described as one of the happiest times of her life. These travels allowed her to fully indulge her adventurous spirit and curiosity, as she had never enjoyed staying in one place for too long.

Sweden.

Holcha studies at the Konstslöjdanstalten school, and worked under professor Georg Karlin, the founder of the Kulturen open-air museum in Lund. Her work with professor Karlin gave her access to the largest Nordic collection of ancient textiles at the museum. Holcha copied many patterns from the collection at Lund and used them in her future textile designs. During her stay in Sweden, she took mini trips and visited museums in Göteborg and Stockholm Norway.

Attends Nini Stoltenberg's weaving school in Oslo. Private pupil of Nini Stoltenberg (1877 – 1969) Norwegian textile artist, known for reviving the historic technique of weaving and whose works were exhibited at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis.

Finland.

Holcha resides in Hameenlinna, a city centred on a medieval castle and home of the famous Fredrika Wetterhoff Craft School. Finnish weaving skill was attracting interest during the early 20th century and many newly graduated teachers found a permanent job there. Girls from Denmark, Norway, Sweden Estonia as well as from Russia came to study in the school each year. It had many international students not only from Europe, but also distant countries like Japan. Holcha also visits Finland's oldest city, Turku. Also known as the "Paris of Finland

France

Holcha spent six months in France where she studied at the famous Manufacture des Gobelins, founded in 1607 in Paris. There she worked along with both craft men and women on tapestries using the same techniques as centuries ago. During this period, she also took shorter study tours to Alsace and Flanders.

Tapestry weavers at their looms. Konstslöjdanstalten in Lund. Sweden. 1900. Image credit: KM 51852. Konstslöjdsanstaltens arkiv

Interior from Manufacture des Gobelins. Paris. Ca 1900. Image credit: Guillaume & Amélie Cornet

Germany.

Holcha studies under Professor Ernst Flemming, at the Higher Technical College for the Textile and Clothing Industry in Berlin. Ernst Flemming (1866-1931) was a textile and clothing scientist who supported the avant-garde art scene of the "Golden Twenties” He led the technical college to become the largest institution of its kind in Europe and hired expressionists such as Walter Kampmann (18871945) as university lecturers.

Holcha also visits Dresden and resides with her sister Erna who was studying at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts and visits her sister, Nanna who was studying at the Dresden Academy of Music. During this time, Holcha experienced firsthand, the so-called Weimar Renaissance and the birth of Bauhaus, and German postexpressionism. Though her sisters, she was introduced to expressionist painters, Oskar Kokoschka, Otto Dix, Conrad Felixmüller and Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler. 1920s Dresden, also became an important centre of the artistic style known as "Neue Sachlichkeit" (New Objectivity) combining biting irony and social criticism with old-masterly elegance and Neo-Romantic ideas.

After her stay in Germany, she took study tours to Belgium, Switzerland and the Netherlands where she visits the Kröller-Müller Museum. Which houses the second-largest collection of paintings by Vincent van Gogh, after the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam

Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler. Self-portrait.1931

Credit: Förderkreis Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Hamburg

Christoph Voll and Otto Dix. A beautiful couple. Collaborative artwork. 1921.

(Credit: Sothebys auction. 25 June 2015)

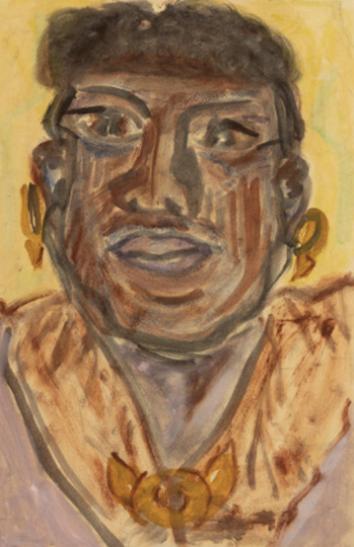

This portrait by Krake highlights her expressive and daring artistic approach, drawing inspiration from German Post-Expressionism. The use of vibrant, exaggerated colors and dynamic brushstrokes captures the emotional and individual essence of the subject, reflecting the German influence she encountered during her time in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. The distorted yet evocative features reveal a focus on inner character and emotional resonance rather than strict realism, aligning closely with the thematic depth and intensity often associated with German Expressionist art.

Early career and exhibitions:

From 1920, Krake became the co-director of the Askov Textile school where she studied in her youth. She ran the school together fellow textile artist, Gerda Michelsen until 1923.

Holchas first major solo exhibition in textile designs was held at the Funen's community centre in Odense in 1923. It was organized by Mrs. Drude Jørgensen, who was the leader of the community centre and also a fine art collector.

Krake quickly became popular with the Odense Housewives Association who invited her many times to showcase her latest designs in home decoration at Industripalæet (the Handicrafts and Industry building) in Odense.

Krake was particularly devoted to interior décor and in addition to woven wall ornaments, she designed and produced bedding sets, towels, tablecloths, carpets, pillow cases, curtains and clothing. Her designs were inspired by her interest in Nordic folklore and featured patterns and motifs from the ancient cultures she had studied. She also showcased her recreations of weavings from the Coptic period and old folk embroideries from southern Jutland and was a firm believer that the past was a model for aesthetic renewal.

Her shows were well visited and especially drew crowds of youths, students, and furniture designers as art weaving was becoming popular in Danish Design. Krake was always present at her exhibitions and was happy to talk about her inspirations and her many travels. She also encouraged people to visit her at her loft studio at Gasværksvej, where she gladly would show samples of her designs and offered her assistance in interior decorating.

By the mid-1920s, Krake had her own modest business in weaving and porcelain painting that she ran from her home and studio in both Odense and Kerteminde. She had an impressive list of clients from all over Scandinavia, USA, India, China and Japan. Most of her sales were smaller items but she also occasionally worked on larger tapestries commissioned from Danish manor houses and sold one of her larger wall ornaments to The Gefle museum in Sweden.

Monthly porcelain painting courses taught by Holcha Krake at Nørregade 49 in Odense. Published on 21 February 1920 and 13 February 1921

Exhibition at Funen’s community centre in Odense and at Ringe boarding House. December. 1923

Exhibition at the Mission Hotel, Odense. December, 1925.

Exhibition at Industripalæet Odense, December 1924

Nordic Art Colony in Cagnes-sur-Mer and Meeting William H. Johnson,

In 1928, Holcha Krake embarked on an artistic journey through Europe, joining her sister Erna and brother-in-law Christoph Voll, a German sculptor, on their study tour. Their first destination was the vibrant art colony in Cagnes-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, a picturesque village that had become a hub for Nordic artists. Danish modernist artists like Vilhelm Lundstrøm and Axel Salto, members of the influential art group "De Fire" (The Four), along with Karl Larsen and Svend Johansen, frequented this community.

Danish journalist and author Andreas Vinding, a resident of Cagnes-sur-Mer in the late 1920s, described the village as a bohemian paradise where life was relaxed, wine was affordable, and the sun was abundant. Vinding noted the welcoming spirit of Monsieur Nicolaês, a local merchant who extended credit to the visiting artists, and the camaraderie among artists, poets, intellectuals, and journalists who gathered at Madame Rose's wine cellar in the evenings. The scene at Cagnessur-Mer was reminiscent of the “golden age” of Montparnasse in Paris, offering a rich and supportive environment for the visiting artists .

During her time in Cagnes-sur-Mer, Holcha and her companions met and socialized with a diverse array of artists, including a young black American painter named William Henry Johnson. Johnson’s charisma and talent made a strong impression on Holcha, and the two quickly developed a connection. In early 1929, Holcha, Erna, and Christoph invited Johnson to join them on a painting tour in Corsica. There, amidst the scenic landscapes, Johnson and Holcha’s relationship blossomed into a passionate romance. The trio continued their journey across Europe, with Johnson accompanying them to Germany, Luxembourg, and Belgium.

By the end of their European tour, William H. Johnson proposed to Holcha Krake, and the couple became engaged upon their return to France. After parting ways with Erna and Christoph, who returned to Germany, Holcha and Johnson boarded a steamer from Dunkerque to Denmark. There, Johnson was introduced to Holcha’s family, meeting her mother and sister, Nanna, in Odense

The following year, in 1930, Krake and William Henry Johnson were married, marking the beginning of their life together as an artistic couple.

William H. Johnson (1901–1970) was a black American artist known for his vibrant and expressive paintings. Born in Florence, South Carolina, Johnson studied at the National Academy of Design in New York and spent several years in Europe, where he absorbed modernist influences. His early works reflected European modernism, but after returning to the U.S., he embraced a simplified, folk-inspired style, focusing on African American life, history, and culture. After Holcha Krake´s passing in 1943, he struggled with mental health issues, leading to his institutionalization in 1947. Today, he is celebrated as a major figure in 20th-century American art with his work preserved by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Marriage and Life in Kerteminde.

Holcha Krake’s marriage to William Henry Johnson in 1930 came as a surprise to her friends and family, as she had long valued her independence and had shown little interest in settling down. Her family encouraged her to draft a prenuptial agreement to protect her business interests, which Johnson agreed to, signing it just days before they were married in a ceremony at the Kerteminde town hall on June 4, 1930. They were wedded by the Kerteminde major who was an old friend of Holchas late father.

Initially, Johnson lived in the attic of a villa named Solhøj in Kerteminde, but soon moved into Holcha’s home and studio on the top floor at Gasværksvej 5. This house, located close to the sea and surrounded by nature, served as both a living space and creative studio for the couple.

Their home was a reflection of their unique personalities and interests, as described in a 1931 article by Bodil Bech, a journalist for Tidens Kvinder (Women of Our Time). She wrote,

“On a visit to the artist couple’s home, one finds William and Holcha Krake Johnson residing in a charming, old house on the top floor. Bright sun enters the rooms through pot plants and curious objects in the small windows. The wooden floor is covered with paint splatters, and the rooms contain wonderful old country furniture from Holcha’s childhood home, as well as numerous books and magazines in five languages. There are books by Ibsen, Nietzsche, African American poetry and French art magazines. Their house feels authentic, luxurious yet simple. When you look at the married couple, it is evident that opposites attract. He is brown and strongly built and she is white, petite and with eyes like mother of pearl and electric hair.”

During their time in Denmark, Holcha actively promoted William H. Johnson’s art. Whom was affectionately known as Willie. She often contacted journalists to generate interest before exhibitions, personally visiting editors’ offices to advocate for his work. She meticulously organized their joint shows, sometimes collaborating with local antique dealers to decorate the exhibition spaces with fine furniture and inviting florists to enhance the atmosphere. These exhibitions were known for their vibrancy and elegance, with Holcha’s colorful weavings and designs displayed alongside Johnson’s paintings, creating a harmonious aesthetic

In Holcha, Willie found a most encouraging and loving spouse that initiated a long period of artistic productivity and emotional calm. Holcha, in turn, discovered a soulmate who embraced her free-spirited, bohemian lifestyle and shared her love of travel, art and literature.

The people who were close to Holcha, described her as free-spirited, welltravelled, independent woman with a charismatic persona. She smoked cigars in public, wore colourful flowy dresses with large brim hats, and owned hundreds of books. She was 45 years old when she married Willie who was 29, a foreigner and a Black man. They both stood out in the small fishing village of Kerteminde yet both Holcha and Willie were welcomed by the local community and admired for their artistic talents and charming personalities.

Kerteminde: A Coastal Haven for Art and Tourism

Kerteminde, located on the island of Funen, Denmark, is a picturesque coastal village celebrated for its stunning landscapes and rich maritime heritage. Known as the "Garden by the Sea," Kerteminde flourished as a tourist destination in the early 20th century. The arrival of the railway in 1900 marked a turning point, making the village more accessible to visitors. With the growing number of tourists, local infrastructure expanded. Hotels were enlarged, smaller guesthouses were established, and even private homes were rented out during the summer, with families relocating to their back houses to accommodate visitors. This influx of seasonal travelers created a vibrant market for local artists and craftsmen, offering ample opportunities to sell their work.

During the late 1920s, Holcha Krake rented a studio on Gasværksvej in Kerteminde, drawn by the artistic potential and the steady flow of summer visitors. The location proved fruitful for her, as her work found a receptive audience among the tourists. In July 1930, just one month after their marriage, Holcha and William H. Johnson held their first joint exhibition on the terrace of the prestigious Tornøes Hotel, a centerpiece of Kerteminde’s social and cultural life. Two years later, in October 1932, the couple exhibited their latest works, including ceramics made during their travels in Northern Africa, at the Kerteminde Library.

During their time together in Scandinavia, Holcha and William H. Johnson were able to pursue their art full-time without taking on additional jobs, but this came with sacrifices and a resourceful approach to life. With big art sales being infrequent, they relied on a self-sufficient lifestyle, growing vegetables in community gardens and bartering with local fishermen and farmers for food. Holcha, who had managed her own weaving business since the mid-1920s, applied her financial acumen to their household. She was frugal and resourceful, ensuring that every penny was spent wisely. Nothing went to waste, and their limited funds were carefully prioritized for essentials like art materials, travel expenses, and occasionally, tobacco. While traveling, they relied on Holcha’s educator network to find affordable accommodations, often staying in teachers’ dormitories, boarding houses, with friends or in modest hostels.

Through Holcha, Willie was introduced to hygge (pronounced “hue-gah”), a Danish concept embodying the joy and comfort of being fully immersed in the moment. Despite their modest means, they embraced a rich life surrounded by family and friends, centered on art, literature, nature, and community.

Hygge is about an atmosphere and an experience, rather than about things. It is about being with the people we love. A feeling of home. A feeling that we are safe, that we are shielded from the world and allow ourselves to let our guard down. What freedom is to Americans, thoroughness to Germans, and the stiff upper lip to the British, hygge is to Danes.

Meik Wiking, The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy Living, 2013

William H. Johnson carrying art supplies. Kerteminde ca. 1930-1931. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian.

Artistic Friendships in Denmark.

Although Holcha and Willie had met prominent Danish modernist artists like Vilhelm Lundstrøm, Axel Salto, Olaf Rude, and William Scharff during their time in France and Copenhagen, they were not part of the prestigious Danish artist groups or societies of the era. Instead, their social circle primarily consisted of fishermen, farmers, and educators from Holcha’s personal network. When they did socialize with artists, it was mainly with local painters and craft artists, reflecting their modest and grounded lifestyle rather than integration into elite artistic circles.

Kerteminde and its surroundings had an artist colony, called the Fynbomalerne, with the famous wildlife and bird painter, Johannes Larsen (1867-1961) at the helm. His residence Svanemøllen in Kerteminde became a junction for the Funen artists who primarily painted nature and animals.

Holcha and Willie was not directly associated with the Funen art colony, but records shows that Holcha exhibited weavings based on bird paintings by Johannes Larsen and that Larsen owned a ceramic bowl with bird design made by Holcha. Willie also used Svanemøllen as motif in many of his landscapes and his woodcuts. The grandchild of Johannes Larsen recollects that Willie visited their house and signed the family guest book.

In 1931, Holcha and Willie exhibited together with Regnar Lange (1897-1963), a local painter known as Maleren fra Lillestranden (The Painter from Lillestranden). Lange was a good friend of the couple and he painted alongside Willie when they both did a portrait of Lange's grandfather, Rasmus Christensen.

Another friend and patron of the couple was Niels Lindberg (1886–1974), a landscape painter and chairman of the Association of Funen Artists. In 1933, Willie painted a portrait of Lindberg to commemorate the opening of the Filosoffen exhibition hall in Odense, which Lindberg had helped establish. Lindberg also amassed a significant collection of works and personal items by both Holcha and Willie and played a key role in organizing their 1938 exhibition at Filosoffen.

In 1934, Holcha and Willie met Kirsten Kjær (1893–1985), a self-taught Danish portrait painter known for her bold, expressive portraits and vibrant personality. Kjær captured subjects ranging from the rich and famous to the poor and unemployed. During their meeting, she painted a portrait of Willie, which was later exhibited in Århus that year.

Regnar Lange using the bow of a boat on as an easel. Kerteminde. Ca 1947. Fyens Stiftstidendes Pressefotografer.

Johannes Larsen at Kerteminde beach. 1937. (Kerteminde Egns- og Byhistoriske Arkiv. B5030)

Niels Lindberg Ca. 1930s Image credit: Helle Lindberg Brink

Kirsten Kjær in 1943. (Image credit: Nyfoto: Ole Akhøj

Travels of Krake and Johnson.

Krake and Johnson shared a profound love for travel and exploration, which became a central theme in their life together. Their journeys were not merely about seeing new places but about immersing themselves in the essence of the cultures, landscapes, and communities they visited. This shared passion significantly shaped their relationship and their artistic outlook.

While living in Denmark, the couple often sought inspiration in nature and the joys of simple living. They spent their days hiking through picturesque landscapes, cycling along forest trails, and enjoying the serenity of Denmark’s beaches. They also maintained close connections with family and friends, frequently visiting loved ones in towns like Odense, Ebeltoft, and Copenhagen. These excursions strengthened their bond and reflected their shared appreciation for the beauty in both nature and human connection.

In the early 1930s, their travels extended beyond Denmark, taking them to cultural hubs in France and Germany. They revisited Paris and other artistic centers, engaging with exhibitions and exploring the vibrant art scenes. In Germany, they spent significant time with Erna and Christoph Voll in Karlsruhe, where they found intellectual and artistic camaraderie. These experiences in larger cities allowed them to network with other artists and explore cutting-edge artistic movements, enriching their creative practices.

However, Krake and Johnson deeply valued escaping the hustle and distractions of urban life. They sought out the quieter, more authentic aspects of the places they visited, believing that rural areas held the true essence of the land and its people. This philosophy guided them to remote regions, where they could connect with local communities and artists whose grounded, simple lifestyles resonated with their own approach to life and art. Notably, their travels took them to rural Northen Africa, where they were inspired by the vibrant cultures, traditional crafts, and dynamic landscapes they encountered. These experiences influenced their work, as they captured the essence of the people and the environment in vivid sketches. Similarly, in northern Norway, they stayed with local artists and communities, immersing themselves in the dramatic fjord landscapes and unique Scandinavian culture. These rural experiences offered a stark contrast to their time in cities and underscored their preference for living and creating in harmony with nature.

"We must never remain stagnant; renewal is the essence of growth."

Holcha Krake, on the transformative power of travel and the necessity of reinvention, exhibition interview, Trondheim, Norway, 1937

Map from the Harmon Foundation's 1957 exhibition panels, highlighting Johnson's extensive travels across the U.S., Europe, and North Africa. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Holcha Krake's African Watercolors

In 1932, Holcha and Willie embarked on a three-month journey to Tunisia, North Africa, inspired by Holcha’s fascination with ancient pottery and Willie’s desire undertake a watercolor tour. During their stay, the couple lived with the indigenous Berber people, immersing themselves in the local culture and studying traditional ceramic practices. Holcha’s watercolors from this period, created on cream paper, depict both the Arabs and the Berber people with detail and sensitivity. With bold lines, vibrant colors, and energetic brushstrokes, she captured the essence of her subjects, celebrating the rich cultural diversity she encountered.

Willie and Holcha in Africa. An online spotlight on the couple’s expedition to Tunisia 1932

Willie and Holcha in Africa. Published on February 20, 2024. This free publication provides a detailed exploration of their transformative journey, including their artistic inspirations, cultural experiences, and the impact of Tunisia on their creative practices.

Jutland peninsula, Denmark. 1934.

From October to December of 1934, the couple embarked on an adventurous bicycle tour across Jutland, Denmark’s rural mainland. Carrying camping gear and art supplies, the couple combined their passion for art with exploration, sketching and painting scenes from the Danish countryside along the way.

In Denmark, cycling vacations were particularly popular, seen as a healthy and enjoyable way to spend time together. Denmark’s flat landscape made it easy and practical for long-distance biking, allowing people to explore the countryside.

Holcha and Willies bike journey was tied to their two joint exhibitions held at the local library in Esbjerg in October and at the Aarhus Art Building in December. Their travels took them as far as the scenic southern shores of Mariager Fjord. Along the way, they sketched and gathered inspiration from towns like Randers and Ebeltoft and stayed in hostels or camped in a tent.

This map shows key locations from Holcha and Willie's bicycle tour of Denmark. The marked towns and cities such as Esbjerg, Aarhus, and Mariager highlight the route through Denmark's varied landscape.

William H. Johnson with his bicycle and unidentified boy. Denmark Ca, 1930-1932.

(Credit: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Young men on a cycling holiday through the Danish countryside. Ca,1930-1940. (Credit:

Ahlgaarden.

Their travels through Denmark also brought them to Ahlgaarden, a family farm located on the picturesque Ahl Hage peninsula near Ebeltoft. This idyllic estate, surrounded by forests and sandy beaches, was managed by Holcha’s cousin, Ejnar Mikkelsen, who took over the property from his father in 1927. Ejnar lived there with his wife, Elisabeth, and their four children: Erling, Lis, Helge, and Per.

Ahlgaarden held special significance for the Krake family, serving as a beloved gathering place for relatives from across Denmark and beyond. Each year, the extended family convened for an annual meeting at the farm. Holcha’s sister, Erna, and her husband would travel from Germany, while other relatives journeyed from Copenhagen and Odense.

Ahlgaarden.

Their travels through Denmark also brought them to Ahlgaarden, a family farm located on the picturesque Ahl Hage peninsula near Ebeltoft. This idyllic estate, surrounded by forests and sandy beaches, was managed by Holcha’s cousin, Ejnar Mikkelsen, who took over the property from his father in 1927. Ejnar lived there with his wife, Elisabeth, and their four children: Erling, Lis, Helge, and Per.

Ahlgaarden held special significance for the Krake family, serving as a beloved gathering place for relatives from across Denmark and beyond. Each year, the extended family convened for an annual meeting at the farm. Holcha’s sister, Erna, and her husband would travel from Germany, while other relatives journeyed from Copenhagen and Odense.

William H. Johnson performing a handstand outdoors. Ahlgaarden. Ca, 1934. Credit: Helge and Niels Ejsing/ William H. Johnson papers

Copenhagen, Denmark. 1935.

Copenhagen was home to Holcha’s cousin, Helga Ejsing, whose flat served as a welcoming retreat for Holcha and Willie during their visits. The couple stayed with Helga while hosting their joint exhibition at Gallery Chr. Larsen at Højbroplads in 1933 and during their visits to the city’s museums and annual art events, such as the Grønningen art show held at the prestigious Charlottenborg Building in 1935.

In January 1935, Holcha and Willie were invited into the home of Carl Kjersmeier, a noted scholar and collector of African art. Kjersmeier’s collection in Copenhagen was one of the most distinguished of its time, attracting artists like Man Ray, and inspired movements such as the avant-garde CoBrA group.

Kjersmeier’s groundbreaking scholarship culminated in the 1935 publication of the first volume of Centres de styles de la sculpture Negre Africaine, a pioneering work that systematically analyzed African sculpture styles.

During this period, Holcha and Willie met Paul Robeson, the renowned American actor, singer, and civil rights activist, and his wife, Eslanda, during Robeson’s visit to Copenhagen to promote his film Sanders of the River. Their connection continued in New York in 1939, where Willie taught at the Harlem Community Art Center, located in the same building as Robeson’s office. Robeson supported Willie’s art, owning several of his pieces. In 1945, Willie created a portrayal of Robeson titled Paul Robeson’s Relations, reflecting their shared artistic and social ideas.

Kjersmeier at his home in Copenhagen. 1933-1939. Credit: Jesper Kurt Nielsen. foto Nationalmuseet.

These sketches by William H. Johnson were inspired by illustrations from the catalogue for The African Negro Art exhibition, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. March, 1935. Credit: SAAM. 1967.59.462/ 1967.59.461

Oluf Wissing, Berlingske Illustreret Tidende.

This caricature captures Johnson at the Grønningen Art Show in Copenhagen on January 20, 1935, alongside Danish director Johannes Børresen and author Louis Nicolai Levy. The trio is depicted studying a portrait painted by Albert Naur.

The Grønningen show’s opening day was a gathering of prominent figures in Danish modernist art, including sculptor Jean René Gauguin and painters Olaf Rude and William Scharff. Krake and Johnson were also in the company of Ruth Bryan Owen, the first female U.S. ambassador, appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.

( Credit: Dagens Nyheder. William H. Johnson papers, Archives of American Art.)

Show announcement for Krake and Johnsons joint show at Gallery Chr. Larsen in Copenhagen. November-December. 1932. Image credit: Fyns Stiftstidende Odense

Norway. 1935-1938.

Between 1935 and 1938, Krake and Johnson embarked on an extended and transformative journey through Norway. Initially planning for a few months stay, the couple extended their time to nearly three years, deeply immersing themselves in Norway's natural beauty, cultural heritage, and rural traditions.

Their travels were marked by an intimate engagement with the landscape and people, as they explored much of rural Norway using bicycles and coastal steamers to navigate the country. They often stayed with Holcha’s extended family and local contacts, which provided them with firsthand experiences of Norwegian life, or camped outdoors in a tent, fully immersing themselves in the rugged wilderness.

This period had a profound impact on their artistic development, as both artists drew significant inspiration from Norway’s dramatic landscapes, rich culture, and traditional arts.

Krake focused on creating delicate and detailed interpretations through watercolors and oils during this period which were exhibited together with her textiles and ceramics. She was particularly drawn to the serene atmosphere of Norway’s rural life, capturing the charm of small coastal villages, with a light touch and a keen eye for color.

The couple’s travels took them to both iconic and remote regions across Norway, including Northern Norway’s Lofoten Islands, Bodø, and Svolvær, where the dramatic mountain coastlines and fishing villages served as endless sources of inspiration. They also visited the central and western fjord regions, including Hardanger and Nordheimsund, known for their breathtaking landscapes and cultural traditions.

In places like Trondheim, Lom, and Lillehammer, they encountered Norway’s rich history, exemplified by medieval stave churches, rural communities, and traditional wooden architecture. Each location offered new visual material that shaped their artistic output and deepened their appreciation for Norway’s cultural and natural heritage.

The map outlines the couple’s immersion into Norway’s diverse landscapes from the Arctic regions in the north to the fjords and villages of the west, and the cultural heartlands of Oslo and Lillehammer.

Oslo.

The couple’s first stop in Norway was Oslo, the capital city, where they stayed at Ro Pensjonat, a guesthouse in the downtown area. In March 1935, Willie participated in an exhibition at the prestigious Blomqvist Gallery, showcasing his work alongside Norwegian painter Olaf Holwech.

Meanwhile, Krake undertook an ambitious project that reflected her fascination with Norwegian textile traditions and medieval craftsmanship. She began researching the famous Baldishol Tapestry, believed to have been produced between 1040 and 1190. This intricate and historic piece, thought to be one of Europe’s oldest surviving tapestries, became the focus of her work during their time in Oslo. Invited to study the artifact in detail, Holcha began an in-depth recreation of the tapestry, embarking on a project that would require years of meticulous effort.

With guidance and collaboration from Ulrikke Greve, a renowned Norwegian textile artist, Krake immersed herself in traditional techniques of weaving and dyeing. Greve, known for her expertise in preserving and recreating historical textiles, mentored Krake in sourcing original plant-based dyes and preparing the wool for weaving. Krake adopted historical methods to ensure her recreation was as authentic as possible, weaving on a portable loom that she could transport as she and Johnson continued their travels across Norway.

Ulrikke Greve (1868–1951) was a pioneering Norwegian textile artist of the early 20th century, renowned for her masteryoftapestrywork.In 1900, she became director of the weaving school at the National Museum of Decorative Arts (Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum) in Trondheim. She later established her own school, Norsk Kunstvæv, in 1905, which gained widespread popularity. Greve was highly regarded for her deep expertiseinyarn,color,andtechnique, earning a reputation as a leading advocate of collaboration between weavers and artists.

The Baldishol Tapestry is one of Norway's most treasured medieval artifacts and among the oldest surviving European tapestries.

Discovered in 1879 during renovations at the Baldishol Church in Hedmark, Norway, it had been repurposed as an altar cloth. The tapestry is thought to be part of a larger, now-lost work, possibly depicting a calendar or seasonal cycle. The surviving portion represents April and May.

On the left, a bearded man in a tunic stands beneath an archway labeled "April," surrounded by four birds, three perched in a tree. On the right, a knight in armor sits astride a horse, holding a shield and lance, beneath an archway labeled "May."

Edvard Munch, Christoph Voll and Erna Krake.

In Oslo, Holcha and Willie experienced a defining moment when they were introduced to the renowned Norwegian expressionist Edvard Munch, one of Europe’s greatest living artists. This encounter left a lasting impression, and Holcha often referenced it in promoting Willie’s work to galleries and potential buyers.

Munch already had a personal connection to Holcha’s family through Christoph Voll, her brother-in-law. Voll, a prominent German Expressionist sculptor and printmaker, had met Munch in Norway in 1925, and the two maintained correspondence. Voll, who married Holcha’s sister Erna in 1922 after meeting her during her studies in Dresden, gained widespread acclaim and a professorship at the Karlsruhe Art Academy in 1928.

However, the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany brought devastating consequences for Christoph Voll. Under Hitler’s regime, Voll endured relentless persecution, including frequent Gestapo interrogations and harassment. Many of his works were confiscated from museums and labelled "Entartete Kunst" ("degenerate art"). His sculptures were publicly mocked in the infamous Degenerate Art exhibitions, starting in Dresden in 1933 and later in Munich in 1936 and 1937, orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels. Voll was later banned from working and exhibiting, culminating in his dismissal from the Karlsruhe Art Academy in 1938, effectively silencing his artistic career under the oppressive Nazi regime.

Amid the escalating persecutions, Voll sent Erna and their young daughter to Denmark in 1939 for safety, while he stayed behind to protect his artworks. Tragically, later that year, he fell ill and passed away under mysterious circumstances at only 42.

Determined to preserve her late husband’s legacy, Erna turned to Munch for help. Munch devised a clever plan: he helped arrange a false exhibition at the National Gallery in Oslo, convincing German authorities of its legitimacy due to his own prestigious reputation. As a result, many of Voll’s works were transported in a sealed train car to Oslo. Danish authorities intercepted the shipment, securing the works in Denmark, where they were hidden in the cellars beneath the Danish Parliament.

During the German occupation of Denmark, Christoph Voll's artwork remained out of German hands, hidden safely by Danish authorities. However, the German

occupiers attempted to have Erna and her daughter, Karen Voll, both German citizens, sent back to Germany. Before this could happen, Erna managed to regain her Danish citizenship, which also extended to Karen. This legal change ensured their safety, allowing them to remain in Denmark and avoid deportation.

Lush and strong women were central motifs in Christoph Voll's work, often inspired by his wife, Erna, and her sisters, Nanna and Holcha Krake.

One of Voll’s most infamous sculptures was his 1921 wooden work, Schwangere Frau (Pregnant Woman). This piece, showcasing a raw and unapologetic portrayal of motherhood, was targeted by the Nazis during the Degenerate Art exhibitions of 1933, 1936, and 1937.

In these exhibitions, Schwangere Frau was maliciously renamed Prostitute and described in the exhibition catalogue as a "glorification of prostitution" and an attack on the sanctity of family and motherhood. The sculpture, emblematic of Voll’s celebration of feminine strength, was labeled degenerate and subjected to public ridicule before being destroyed in 1937.

Gudbrandsdalen.

From Oslo, Krake and Johnson traveled north to Lillehammer, a city renowned for its artistic and literary heritage, famously visited by figures such as Claude Monet. During the summer of 1935, they stayed with some of Holcha’s childhood friends before embarking on their journey toward Volda.

Equipped with camping gear and art supplies, the couple set out on bicycles, immersing themselves in the breathtaking landscapes of Gudbrandsdalen, one of Norway’s most iconic valleys. Stretching over 200 kilometers, Gudbrandsdalen is a living tapestry of lush green pastures, dense forests, and dramatic peaks, its beauty celebrated in both art, myth and literature.

The valley had notably inspired Henrik Ibsen (1823-1906), whose dramatic poem Peer Gynt drew heavily from its legends and scenery. Krake and Johnson, both admirers of Ibsen’s works, embraced the cultural richness of the area. Johnson later remarked in an interview that he had read every one of Ibsen’s books, highlighting their shared connection to the writer’s exploration of folklore and the Norwegian spirit.

Their route through the valley included a visit to the picturesque village of Lom, home to a stunning 12th-century stave church. This architectural masterpiece left an impression on Willie, later inspiring his 1939 woodcut series, which captured the simplicity and grandeur of Norway’s medieval wooden churches.

During their time in Gudbrandsdalen, Krake likely delved into the region’s 17thcentury tapestries, intricately woven textiles that combined artistry with storytelling. These tapestries, created between the 17th and 18th centuries, often depicted Biblical scenes and chivalric ballads, serving as visual aids or “memory cues” for oral storytellers. Legends from the valley even tell of fantastical weavers, whose almost magical artistry became part of the local folklore.

Bøyg is a troll that is said to hinder travellers at Gudbrandsdalen. (Theodor Kittelsen. Museum Stavanger)

Credit: Arne Normann/ Swedish Pictura AB

Gudbrandsdalen tapestry depicting Guiomar. Ca 1650-1750, by unknown female textile artist.

Guiomar is an Arthurian legend. It is said that he was the lover of a fairy queen and taken to the magical kingdom of Avalon (Credit: Jaques Lathion. Kunstindustrimuseet)

Volda

In September 1935, Krake and Johnson arrived in the village of Volda, a place Krake had considered her second home since youth and built lifelong friendships. They visited Olav Riste, a schoolteacher, and newspaperman with whom Holcha had lived with in early 1900s.

They also stayed with Krake’s childhood friend, Kjellaug Kaarstad, and her husband, Lars Tjensvoll, a widowed parish priest with seven children, at the Tjensvoll vicarage. After six months, they moved to a basement flat owned by Krake’s friend, Anna Klepp at Øvre Engeset, which served as their base for the next two years.

During their time in Volda, the couple held two official joint exhibitions: one at Uppheim Volda (the Volda community house) in December 1935 and another in May 1937 at Volda Kunstlag (Volda Art Club). They also held an informal exhibition at the home of Holcha’s childhood friend, Gjertrud Brænde.

When Krake and Johnson planned to travel further north, Erling Kristvik, the new headmaster of the teachers' college in Volda, provided them with letters of introduction to his teacher contacts in the north. Thanks to his help, they were warmly welcomed wherever they travelled and often stayed in the teachers’ private homes or in schoolhouses.

View over Volda, Sunnmøre, ca 1900.

(Credit: Knud Knudsen/ KK-klassisk samling)

Volda, a picturesque rural town in Norway's Sunnmøre region, lies along the Voldsfjorden, framed by the majestic Sunnmøre Alps. Despite its remote setting, it has long been a center of education and culture, beginning with the establishment of a teacher training college in 1861.

By the 1930s, Volda's population had grown to around 5,000, fostering a close-knit yet vibrant community that attracted intellectuals, artists, and educators, cementing its reputation as a hub for learning and creativity.

Olav Riste

(Credit: Norsk Allkunnebok, niande bandet, kolonne 660.)

Lars Tjensvoll. Ca,1935.

(Credit: Kørnsberg, K/ Jærmuseet)

Kjellaug Kårstad. Ca. 1939.

(Credit: K. Kørnsberg. Fotograf i Volda)

Olav Riste (1884–1967) was a respected schoolteacher, farmer, and author from Volda, Norway. The son of activist and educator Per Riste (1846–1930). Olav followed in his father’s footsteps, contributing significantly to education in rural Norway. In 1910, he helped establish Volda's private secondary school and gymnasium, the country’s first rural high school, where he served as director until 1954. An active member of Volda’s intellectual circle, he edited the Annual Journal for the Volda Historical Society, writing extensively on local history. Holcha Krake, during her youth in Volda, became closely acquainted with Olav Riste and his family, whom she regarded as her second family.

Lars Tjensvoll (1888 - 1982) was the parish priest in Volda from 1930 to 1958, and husband of Holcha’s childhood friend, Kjellaug Kaarstad. He was interested in literature and the arts and was one of the co-founders of the Volda Kunstlag (Volda Art Club) in 1937 which housed Holcha and Willies exhibition in May 1937. Tjensvoll and Olav Riste belonged to intellectual circle who met at a cabin called Dalebu where they would write, draw and sing. Holcha and Willie visited the cabin in September 1935 and sketched a self portrait in the cabin’s guestbook.

Kjellaug Kaarstad Tjensvoll (1895–1986) was the daughter of Henrik Kaarstad, director of Voldens Privatseminarium (Volda’s teachers’ college). Holcha Krake stayed with the Kaarstad family while studying and also worked as a governess for the Kaarstad children. During this time, Holcha and Kjellaug formed a lifelong friendship that endured through the years. In 1930, she married Lars Tjensvoll, a widowed parish priest with seven children, whom she lovingly took into her care. Beyond her role as stepmother, Kjellaug nurtured her students, often hosting them for banquets at the rectory. For her lifelong contributions to education and her community, Kjellaug was awarded the King’s Medal of Merit in gold in 1965.

Jølster.

Kralke and Johnson visited Jølster, a rural area in Vestland County, in the period 1935-1936. Known for its rich cultural history, legends, and stunning scenery, Jølster, with a population of around 2,500, was surrounded by mountains and the serene lake Jølstravatnet. Most residents lived on small farms, and news arrived only through days-old newspapers from Bergen.

In 1935, the couple stayed for about three- six months at Klakegg an agricultural settlement in Jølster. They lived on a farmstead called Myrane, owned by local farmer, Daniel Ludvigson Klakegg (1910- 1948). Records from the area suggest their extended stay was due to Holcha’s collaboration with local weaver Synøve Øvrebø Klakegg. During this time, they also visited the Stardalen valley, Stølshus, Våtedalen and the nearby village of Skei, home to about 500 people.

Johnson fondly recalled their stay in Jølster during a 1938 interview, highlighting the simplicity and close-knit nature of the community:

"Most of the population had little idea of the world beyond the parish; many had never been outside it, and those who had ventured beyond had only been as far as Bergen. Naturally, they observed my wife and I painting outside with growing excitement and curiosity. When we spoke of leaving the area, they asked us to organize an exhibition.

With no formal venue available, the local school became our exhibition hall. The show took place on a Sunday, and the day before, on Saturday, Holcha and I posted handmade announcements at the grocery store and dairy farm, as the area had no newspapers. Despite these modest efforts, the exhibition drew an enthusiastic crowd, with people standing both inside and outside the school. Some had travelled far, even from the mountains, to see our work.

Of course, we didn’t sell a single picture nor did we expect to, as no one in the poor parish could afford it. But I assure you, these people, with their raw and immediate connection to art, understood my pictures better than many who attend my exhibitions in the big cities. This was one of the most personally rewarding exhibitions my wife and I ever held even if we didn’t sell a single piece."

Photo of the Klakegg settlement in Jølster. The circled buildings are “Myrane,” the farmstead owned by Daniel Klakegg, which served as the residence for Krake and Johnson during their visits in 1935–1936. (Image credit: Judith Hegrenes /Norwegian Folk Museum)

View over Våtedalen, Jølster. 1896 (Digital museum)

William H. Johnson. Vaatedal, Jølster, Norway ca. 1936 Smithsonian American Art Museum.1967.59.892

Jølster is the birthplace of Nikolai Astrup (1880–1928), one of Norway’s most celebrated and beloved visual artists. While it remains uncertain whether Krake and Johnson were familiar with Astrup’s work before arriving in Jølster, they likely encountered his art during their stay. His home and studio, Astruptunet, situated on the southern shore of Jølstravatnet, was transformed into a museum by his widow, Engel Astrup (1892–1966), following his death in 1928. In addition to showcasing Nikolai Astrup’s paintings, Engel curated an extensive collection of antiques and historical Jølster textiles.

Over the years, Engel Astrup distinguished herself as a talented textile artist, becoming known for her intricate hand-printed fabric designs. Her work, which included hand-printed tablecloths, was exhibited at the Bergen Art Union in 1939. Until her passing in 1966, Engel managed Astruptunet, ensuring that her husband’s artistic legacy endured.

Although it is unknown whether Krake and Engel Astrup ever met, they shared a deep connection through their craft. As textile artists and wives of passionate painters, they would have found much in common had their paths crossed.

During their stay in Jølster, Johnson was captivated by the region’s majestic mountains and lush valleys, often painting from the very same vantage points that Nikolai Astrup had chosen years before. His work, like Astrup’s, reflected the striking natural beauty of Jølster, forging an artistic link between the past and present

Engel and Nikolai. Ca. 1920s. Engel Astrup, married Nikolai in 1907. She supported her husband through thick and thin and was always by Nikolai's side during his long periods of illness.

Credit: Musea i Sogn og Fjordane

Astruptunet home and museum, 1963. Engel Astrup is seated on the far left. She is joined by her son, Dagfinn, his wife Klara, and two of her grandchildren.

Credit: Kode Kunstmuseer. Bergen

A Night in June. Jølster. (Nikolai Astrup. 1905-07)

Credit: Bergen Kunstmuseum, KODE

The Grepstad Mountain Farm in Jølster. (Nikolai Astrup, 1923 – 1927).

Photo: Anders Bergersen (2015)

Jolster II, (William H. Johnson. 1936) SAAM 1967.59.874

The Grepstad Mountain Farm in Jølster. (William H. Johnson 1936) Credit: Doyle: Impressionist & Modern Art November 2019.

Svolvær.

In December 1936, Krake and Johnson visited Ålesund, a picturesque seaport town 70 km north of Volda. With the help of Holcha’s friends, they held a joint exhibition at the Afholdshjemmet (The Temperance Home). The show featured Johnson’s landscapes from Volda, alongside Krake’s weavings and ceramics, and for the first time, her oil paintings were mentioned in exhibition reviews.

From Ålesund, the couple boarded a coastal steamer to Tromsø, stopping at rural towns such as Sandøy, Bodø, and Narvik along the way. Onboard, they met the American couple Helen and David Harriton, who became lifelong friends. In Tromsø, they exhibited their work at the Tromsø Handicraft Society before continuing to Svolvær, in the Lofoten archipelago, where they spent the summer of 1937.

Krake described their time in Svolvær in a letter to the Tjensvolls titled “A Letter from Wonderland”:

“In Svolvær, we have found our dwelling in a cozy little rooftop flat, with a nice view and a garden filled with flowers. We even planted a small kitchen garden, and within two weeks, we were harvesting radishes and salads. Everything grows so fast here, and the summer feels tropical. We had thought the area would be dominated by rocks and greens, but instead, we found meadows and fields filled with buttercups of extraordinary size and color, and swarms of pink willowherbs that even grow on the mountainsides, which here have a rare green colour.

The mountains, the light, the sea, the colors everything here is fantastic. Mr. Johnson has worked day and night with an obsessive energy. Some of his best oils and watercolours were painted from Svolværgeita mountain peak, which he climbed every day. The climb is much harder than Mount Rotsethornet in Volda, but the effort was worth it. The view with the midnight sun shining over the peaks and fjord is the most magnificent we have ever seen.

The air is so refreshing that one hardly needs sleep, and we bathed in the sea every day, all summer. The water was warm, like the French Riviera hard to imagine so far north!”

Holcha, Svolvær. 1937

Johnson on board the Norwegian Coastal Express (Hurtigruten) D/S Kurs Nord. Ca, 1936-1937 (Image credit: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Svolvær, Norway: located between mountains and sea is the largest town in the Lofoten islands. Photo. Ca, 1940.(Credit: P.J. Rødsand)

Svolværgeita mountain. Ca, 1930

(Credit: Normann)

The Svolværgeita mountain, also known as “The Goat” The peak earns its nickname from the two distinct horns of rock that sit atop it, offering both a dramatic silhouette and a thrilling challenge for climbers. William H. Johnson first had to hike the 1kilometer path to its base before ascending the 56meter climb to the top. The peak’s surface, a slanted area roughly 1 meter wide and 1.5 meters long, provided a narrow perch where Johnson could rest and marvel at the panoramic view of the archipelago below. For the truly adventurous or slightly audacious the horns present another challenge: leaping from one to the other. Which has become a rite of passage for some climbers today.

The nearly three years that Holcha and Willie spent in Norway marked a period of tremendous creative growth. For Willie, it was a time where he incorporated elements of Northern modernism into his work, resulting in expressive landscapes with textured brushwork.

For Holcha, Norway provided the opportunity to expand her artistic practice, particularly in creating watercolors and oils. Her watercolors from this period captured the subtle beauty of the Norwegian landscape, with her use of transparent washes of color evoking the ethereal Northern light and the gentle contours of fjords and mountains. This approach brought a sense of harmony and delicacy to her depictions of Norway’s natural beauty

"High in the mountains, where the air is clear and sharp, where the fjords cut deep into the land, and the waterfalls fall like silver threads from the heavens there, you will find the soul of Norway, untouched and eternal, waiting to be understood."

Henrik Ibsen (Norwegian playwright, 1828–1906), from Peer Gynt (1867)

In Full Bloom: Krake's Floral Works

Krake’s watercolors shine brightest in her floral still-lifes, showcasing her exceptional mastery of colour, composition, and expression. The warm, earthy tones of her backgrounds create a striking contrast with the vibrant hues of her flowers, imbuing her works with vitality and warmth. Her background in textile design is unmistakable, reflected in the intricate patterns and her harmonious blending of colours, which elevate each piece beyond mere observation to something truly artistic.

In Danish folklore, flowers hold deep symbolic meanings, often linked to love, protection, and celebration. Krake deftly weaves these cultural narratives into her floral works, transforming still-lifes into visual stories. For example, in Floral Stilllife with Figurine, she includes a decorative reclining red deer. This element serves as more than an ornamental touch it embodies nature and Danish identity, echoing 19th-century ideals of strength and a longing to reconnect with the natural world.

Through her floral compositions, Holcha invites viewers to look beyond the surface beauty of flowers and explore their cultural and symbolic layers. Her floral watercolours are not just visually captivating but also profoundly meaningful, revealing the deeper stories flowers can tell.

Holcha Krake’s Recognition in Oil Painting.

In the period 1936–1937, Krake’s work in oil began to garner significant attention, earning as much praise as her textiles and ceramics in exhibition reviews. In 1937, Krake and Johnson expanded their Nordic travels with a three-month visit to Sweden, where they participated in group exhibitions in Stockholm, Västerås, and Gävle.

The reviews from the Stockholm exhibition at Mässhallen were particularly enthusiastic about Krake’s works in oil, highlighting the boldness and vibrancy of her approach. Critics remarked that her pictures were "extremely successful" and commended her striking use of colour. One review noted that Holcha’s application of colour was even more extravagant than her husband’s, describing her technique as if she were “printing the colours directly from the tubes” and even incorporating the use of a modelling stick to add texture and depth.

These reviews solidified Krake’s reputation as a versatile and innovative artist, capable of excelling in multiple mediums.

Oil painting. Still-life with Herring Holcha Krake. Ca 1936-38 Current location unknown. Courtesy of Christoph Voll estate collection.

Oil painting. Apple Blossoms and mountains. Holcha Krake Ca 1936-38. Current location unknown. Courtesy of Christoph Voll estate collection

Mr. Johnsons Pipes Holcha Krake Ca 1936-38, Oil on paper. Private collection. Norway

Krake’s Mr. Johnson’s Pipes is more than a still-life it is a deeply personal work that captures the quiet intimacy of her life with her husband, Johnson. Painted on bond paper, the work showcases Krake’s mastery of oil as a medium. The painting features a blue jug, a tin, and Johnson’s pipes, arranged thoughtfully on a textured surface.

While the objects may appear ordinary, their significance is profound, particularly the pipes, which evoke a sense of Johnson’s presence and the closeness of their artistic and personal bond. The title itself is revealing. While Johnson was affectionately called “Willie” by friends, Krake always referred to him formally as “Mr. Johnson” in letters home, reflecting her respect for their partnership and his creative identity.

William H. Johnson and Holcha Krake: A Creative and Cultural Partnership

Johnson’s depictions of Krake, along with their collaborative artworks, reveal a profound personal and artistic partnership that spanned continents and cultures. Krake, as both Johnson’s wife and creative equal, was a central figure in his life. His portrayals of her reflect their deep bond and shared artistic vision. Johnson’s portraits of Krake often highlight her with bold brushstrokes and vibrant colors, emphasizing her strength, individuality, and her role as a stabilizing and inspiring presence. These portraits, though few in number, stand as tributes to the significant influence Krake had on Johnson’s art and worldview.

Examples of Johnson’s depictions of Krake include the hand-colored woodcut Holcha Krake (1930–1935), the dual portrait in watercolor Willie and Holcha (1930–1932), and its woodcut version Willie and Holcha (1935). Another notable work is Bonfire Evening, Self-portrait with Wife (1938–1946), a memorial landscape sketch in which Johnson imagined himself and Holcha in the rural South a place Holcha never visited due to laws prohibiting interracial marriage in the region at the time.

During their time together, the couple also collaborated on a range of artistic endeavors, including watercolors, paintings, and ceramics. One of their earliest known collaborations is Cottages, a watercolor signed “Holcha Krake Johnson & Comp.” and dated June 6, 1930, just two days after their wedding at Kerteminde Town Hall. Another example of their joint effort includes ceramic works created in Tunisia in 1932, which they both modeled and hand-painted.

Portraits of Holcha Krake by William H. Johnson Ca 1930-1947.

From Left:

(1). Portrait of Holcha Krake (William H Johnson, Woodcut. 1930-1935), SAAM, 1967.59.794. (2). Portrait of Holcha Krake (William H. Johnson) Sotheby's New York. 2007. (3). Willie and Holcha (William H. Johnson woodcut ca. 1935) SAAM 1967.59.793.

From Left:

(1). Seated Holcha (William H. Johnson Study for woodcut. 1935-1938) Niels Lindberg. Nr. Broby. Funen (2). Bonfire Evening, Self-portrait with Wife (William H. Johnson 1938-1947) Black Art Auction. 2022. (3). Study for Willie and Holcha (William H. Johnson 1930-1932) SAAM,1967.59.89R-V

Collaborative Artworks.

Cottages, 6/6/1930

William H Johnson & Holcha Krake

Credit: Voll Collection, Florence County Museum

Sometimes the couple worked side by side, each infusing the scenery with their distinct artistic sensibilities.

Top: The Red Road (William H. Johnson, ca. 1930-1932) Smithsonian. Bottom: Red Farm House Holcha Krake 1930s Wright Collection.

Ceramic tea set. 1932-1938.

William H Johnson & Holcha Krake.

Credit: Thom Pegg. Black Art Auction

Self-portrait sketch. William H Johnson & Holcha Krake, 1935 From the guestbook of the Dalebu cabin in Rotsetdalen. Norway.

(Credit: Per Buset/ Narve Birkeland. Volda Kunstlag, september 2001)

Christoph Voll and Erna. 1921. Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Kunstsammlungen

Johnson and Krake. 1937 (Dagens Nyheter, Mässhallen. Stockholm)

North and South II is a collaborative dual oil portrait on fibreboard created by William H. Johnson and Holcha Krake in 1937 during their time in Norway. Signed by both artists, the painting is a powerful exploration of their shared personal and cultural identities Johnson as an African American artist from the rural South and Krake with her Nordic heritage. It is believed that Johnson painted Holcha, while Krake painted him, symbolizing their mutual artistic and emotional connection.

The composition depicts the couple elegantly dressed for an evening out. Holcha is portrayed in a luxurious fur coat, exuding sophistication, while William is shown in a formal suit, highlighted by his signature red scarf. The piece captures not only their physical likeness but also their shared experiences and creative partnership. The swirling, expressive brushstrokes convey energy and movement, embodying both the vibrancy of their partnership and the complexities of the time in which they lived.

1937 was the year of the infamous Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich, where avant-garde works, including those by Holcha’s brother-in-law Christoph Voll, were confiscated, mocked, and displayed as degenerate. This painting, created during the same year, could be interpreted as a tribute to Voll and their German friends – A statement of solidarity with those whose artistic freedoms were under threat.

Departure to New York. 1938.

In 1938, with the threat of war looming over Europe, Holcha and Willie made the difficult decision to leave Scandinavia for the United States. After years of artistic growth in Africa, Europe, and Scandinavia, the couple held a farewell exhibition at Filosoffen in Odense, Denmark, showcasing their collaborative and individual works. This marked the culmination of a significant chapter in their artistic journey. For Willie, the move also represented an opportunity to introduce his latest works to the American audience. He was eager to reconnect with his homeland and share the artistic evolution he had undergone during his time abroad.

In November, they boarded the M.S. Pilsudski, a Polish trans-Atlantic steamer, for the voyage to New York. The Pilsudski, a symbol of modern ocean travel, was tragically sunk by German forces the following year, a stark reminder of the political tensions that had prompted the couple’s departure. Their journey to New York marked both a safe escape from the growing dangers in Europe and a new beginning in their creative endeavors.

"We have a home in America, one in Denmark, and one in Norway, but my wife and I are too young to settle down for good. You have to travel while you still have eyes to see the world."

– William H. Johnson, Exhibition Interview, Stockholm, Sweden, 1937.

William

Atlantic crossing. Ca 1938. (Image credit: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Holcha Krake in New York.

Holcha and Willie arrived in New York on November 26, 1938, after their departure from Europe. They initially found temporary refuge with their friends Helen and David Harriton, whom they had met during their time in Norway. Shortly afterward, they moved into their own flat at 27 West 15th Street, located close to Greenwich Village, known for its bohemian lifestyle and artistic communities.

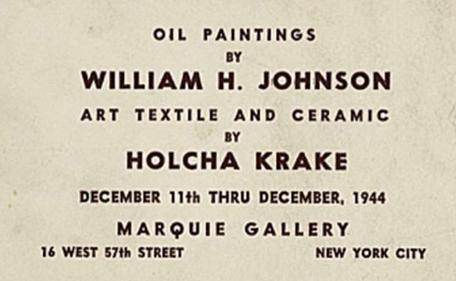

Holcha quickly immersed herself in New York’s vibrant art scene. In 1939, she exhibited her tapestries at the Danish Pavilion at the World’s Fair, showcasing her mastery of traditional Scandinavian textile techniques to an international audience. Later that year, in February, she and Willie participated in a joint exhibition at The Artists Gallery, NY. The highlight of the show was her recreated Baldishol Tapestry, which she had completed in Norway and revealed for the first time in America.

To support their new life in New York, Willie took a teaching position at the Harlem Community Art Center, where he worked from 1939 to 1942. This role provided a vital source of income for the couple, who had returned to the United States with limited financial resources and were struggling with diminished art sales due to the war.

During this time, Holcha often accompanied Willie to the Art Center. Inspired by the vibrant community, she created a series of watercolor portraits that captured the likenesses of the models and students there.