Last academic year was surely the strangest and most challenging that schools in the UK have ever experienced. And the year ahead will have to respond to all that has happened.

During home learning it was more important than ever that teachers, students and parents could easily find what they needed on our website. The strengths and weaknesses of our site became much clearer to us as we watched uptake of our various home learning resources.

How will this shape CAFOD’s support for Catholic schools in England and Wales?

When lockdown happened, like all teachers, our Education team had to adapt quickly to new ways of working. And we plan to carry into the new academic year the insights we gained.

So we spent the summer reworking our webpages. We hope that our academic, collective worship and other resources are now much easier to locate. Some resources have been updated, and some new ones have been added.

During lockdown we began monthly coffee catch-ups on Zoom with school chaplains. These were very popular and will continue. They are a chance for chaplains to share with each other and with us some of the challenges that they experience and the resources, initiatives or support that they find most useful.

If you are a chaplain and would like to join the next catch up, contact schools@cafod.org.uk

One thing the chaplains highlighted was the constant need for new, easy-to-use prayer resources. So, as part of our mandate to promote understanding of and engagement with global justice, we will provide new prayer and liturgical resources in the coming year. We’ve begun with a collection of twelve prayers. Each fits a different global justice theme and is on a PowerPoint slide, ready for assemblies or classroom prayers.

This work is ongoing, so please let us know what works for you and where we can improve things further: schools@cafod.org.uk

Prayers for young people: cafod.org.uk/youngpeopleprayers

We have always provided assembly material for schools, particularly during Lent, Harvest and Advent. In the past, these have been in the form of an adaptable PowerPoint and script, often with an accompanying

film showing our work alongside poor communities around the world.

During lockdown we felt that something more was needed. With most students at home, normal assemblies and acts of collective

worship - those reassuringly regular parts of the school week - had become impossible.

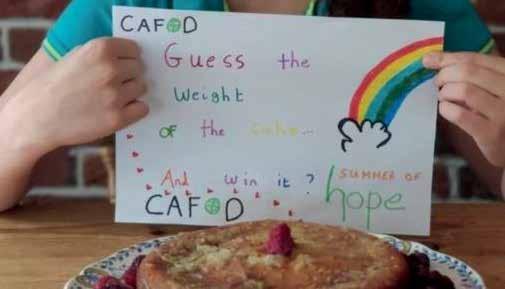

So, our first ever online assembly “Hope in the time of coronavirus”, premiered on Youtube on 18 June. The response was incredible. We received many photos of students watching together in class and messages saying how uplifting the experience had been. Some followed up by supporting CAFOD’s Summer of Hope, fundraising for our Coronavirus appeal. Thank you!

We will offer more online assemblies in the coming academic year. We held one to start the year on 10 September, “The world you want”, and will run another on 8 October in anticipation of Harvest Fast Day.

Watch the previous assemblies and find out about the next one at: cafod.org.uk/schoolstogether

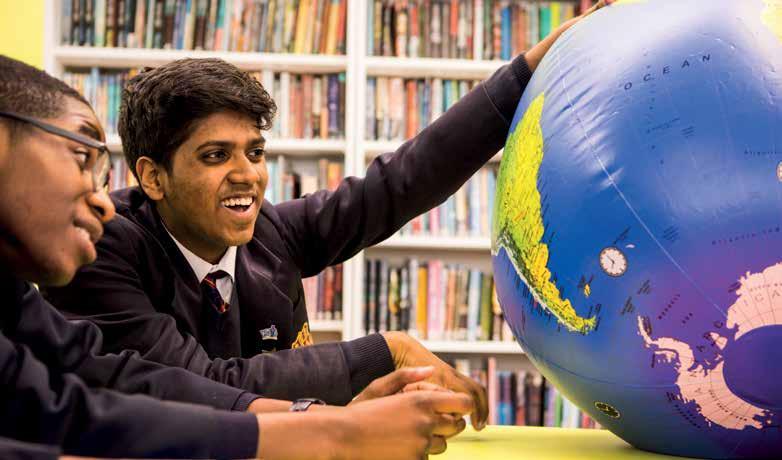

By March, our team had trained more than 500 teachers in using a range of global resources and in how to make great school links, as part of our three-year programme of free, British Council funded CPD. The teachers gave amazing feedback and we were devastated when this programme had to stop.

So, during lockdown, our professional trainers, Bethany Friery (primary) and Susan Kambalu (secondary) worked hard moving the programme online to ensure that this dynamic training could continue.

In the coming year we are offering Everything is connected: Enrich school life through global learning as an online course. We hope that Connecting to the world: Successful school linking will follow soon. You can already book for our face to face course, Young leadership for global justice, in May.

Find out more on our CPD pages: cafod.org.uk/connectingclassrooms

When school visits by our 200+ school volunteers came to an abrupt halt, many schools missed out on visits they had already booked, but our volunteers also felt the loss.

Our Liverpool team even made a video to let their schools know how much they were missing them! You can watch it at https://vimeo. com/437867768.

As the new term begins we know that schools will welcome essential visitors only. But our School volunteer coordinator, David Brinn, has been working with our trained volunteers to develop an engaging range of online offers so that they can continue to support schools, giving children and young people an insight into CAFOD’s work.

If you would like a virtual CAFOD speaker in an RE lesson, contact dbrinn@cafod.org.uk

Thank you for everything you do to help CAFOD and support your students to be more aware of global justice issues and how they can support the poorest communities.

• Harvest Fast Day - Friday 9 October 2020: Theme: Coronavirus – Survive. Rebuild. Heal. Our Harvest assembly YouTube premiere on Thursday 8 October will share inspiring stories from around the world showing how you are supporting families through this crisis.

• Advent 2020: Primary and secondary Advent calendars will be available as PowerPoints with daily class prayers and activities.

• World Gifts: We will provide simple posters to help classes raise money together for a World Gift, during Advent or at any time of year.

• Lent Fast Day 2021: Lent Fast Day is Friday 26 February. Theme: Walk for Water (Ethiopia). Invite your school to take part in a nationwide walk for water in solidarity with those who must do this daily.

This year has been a year like no other. In a time where it would have been easy to give up hope, young people have instead committed themselves to inspiring and leading us all to a brighter future. Not only were we faced, as ever, with the ongoing challenges of poverty, injustice and climate change, but we were also confronted with a global pandemic.

In the midst of adjusting to a new way of life, to learning at home and not going out with their friends, young people around the UK have challenged themselves to look out for our global neighbours around the world.

Pope Francis in Christus Vivit pointed out to us that “Young people are not meant to become discouraged; they are meant to dream great things, to seek vast horizons, to aim higher, to take on the world, to accept challenges and to offer the best of themselves to the building of something better”. This is exactly what we have seen young people doing with their schools, youth groups and at home during the summer term and holidays.

Young people across the country have accepted the challenge of building something better. Across the world, many people lack access to basic healthcare or clean water, and others cannot go out to work because of the lockdown, making it difficult to provide food for their families. After learning about how different communities have been affected by COVID-19, these young people have come up with creative ways to take part in CAFOD’s Summer of Hope appeal.

At St Bernard’s school in Slough, the students have taken part in a sleep out. Maarlon, a student, shared that “by sleeping outside, we raised money to help those people in need. It made me reflect on how privileged I am to have the basic necessities during this global struggle.” Charity work and fundraising is seen as an important part of St

Bernard’s school community. Siobhan, Lay Chaplain, shared that “The students thought this would be a great way to do something together while we are apart. Students and staff slept in their own garden or living room and were sponsored for this. We raised over £1000 which will go towards helping those that are living in countries with poor health systems”

At Salesians College in Farnborough, the CAFOD Young Leader group have been organising online quizzes for their school community, already raising over £600. Joseph explained that being a young leader is “a good way to make a visible difference to the wider community… and hopefully help change and improve the lives of others.”

Young people in Brentwood diocese have joined together to do an 18 hour Lourdes challenge. After their summer pilgrimage was cancelled, they decided to spend the 18 hours they would have spent on the coach journey doing amazing challenges to raise money for CAFOD. Beth shared that “Young people in the Diocese are brilliant in their creativity and enthusiasm, and we look forward to the 18 hour challenge as a wonderful launch for our virtual pilgrimage”.

Children and primary schools have also been getting involved in the Summer of Hope. Freddie from year 2, decided to do his first ever half marathon after learning about being a good neighbour at school. He has raised over £1000 for CAFOD helping us to reach out to where the need is greatest.

Families around the world are already seeing the difference that our supporters, including these young people, are making. We have been able to adapt our programmes, provide hygiene kits, food and clean water to families, and supported partners to raise awareness in their communities. We have joined forces with the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) to scale up our response, ensuring that no one is beyond reach of the aid they need to survive.

Yet, COVID-19 is still affecting communities around the world. Families who have been forced to flee their homes are particularly vulnerable to the virus. Refugees face overcrowding and a lack of hygiene facilities in refugee camps meaning the spread of the virus could be devastating.

For countries that have had years of conflict, people will struggle to access healthcare and lockdown means people are pushed further into poverty, putting millions at risk of hunger and malnutrition.

As we head into autumn and winter, we continue to work with our experts on the ground to understand their challenges and needs and support them in responding quickly. The need is still great, and as these children and young people have shown us “there is more joy in giving than in receiving, and that love is not only shown in words, but

also in actions” Christus Vivit 197. Their enthusiasm and passion for social justice is inspiring. And you can join them.

On 9 October, schools and families will be taking part in Harvest Fast Day. By coming together for a simple meal, your support can mean fewer families have to ask “How do I keep my child safe if we don’t have water for handwashing?” There are resources available online making it easy for schools to take part and to encourage young people to consider others during this time.

• Order free stickers, money boxes or collection envelopes from shop.cafod.org.uk

• Find videos, assemblies, prayers and other free education resources on our website cafod.org.uk/schools

• Share photos and stories of the day by tagging @CAFOD on Twitter

£6

£6 can buy a hygiene package for a vulnerable family containing soap, washing powder and reusable face masks

We continue to hold you and all our global neighbours in our thoughts and prayers. Whatever you can do this autumn term will make a real difference, as we work together for the common good.

£12 can buy text books, exercise books and pencils for a child to continue their education despite school closures

£12

We can’t wait to see how your school will get involved on or around Friday 9 October!

Download or order your Harvest resources at: cafod.org.uk/schools

Supplied to members of:

The Catholic Association of Teachers, Schools and Colleges. The Catholic Independent Schools Conference. The Birmingham Catholic Secondary Schools Partnership. The Manchester Catholic Secondary Schools Partnership. Through the SCES to all Catholic Schools in Scotland.

Editorial Team:

Editor - John Clawson News Roundup - Willie Slavin

Bob Beardsworth, Peter Boylan, Carmel O’Malley, Kevin Quigley, Dr. Larry McHugh, Willie Slavin, Fr John Baron

Editorial Contributors:

Research: Professor Gerald Grace, CRDCE, Peter Boylan

CATSC - John Nish

CISC - Dr Maureen Glackin

SCES - Barbara Coupar

CAFOD - Lina Tabares

Editorial Office:

Networking (CET) Ltd

9 Elston Hall, Elston, Newark, Notts NG23 5NP

Email: editor@networkingcet.co.uk

Cover: Learning to live and love like Jesus - See p 28

Designed by: 2co Limited 01925 654072 www.2-co.com

Printed by: The Magazine Printing Company

Published by: Networking (CET) Ltd

9 Elston Hall, Elston, Newark, Notts NG23 5NP

Tel: 01636 525503

Email: editor@networkingcet.co.uk www.networkingcet.co.uk

Our mission is to serve as a forum where Catholic heads, teachers and other interested parties can exchange opinions, experiences, and insights about innovative teaching ideas, strategies, and tactics. We welcome— and regularly publish—articles written by members of the Catholic teaching community.

Here are answers to some basic questions about writing for Networking - Catholic Education Today.

How long should articles be?

Usually it seems to work out best if contributors simply say what they have to say and let us worry about finding a spot for it in the journal. As a rough guideline we ask for articles of 1000/2000 words and school news of about 300/400 words.

What is the submission procedure?

Please send as a Microsoft Word file attached to an e-mail. To submit articles for publication, contact John Clawson by email at editor@networkingcet.co.uk

How should manuscripts be submitted?

We prefer Microsoft Word files submitted via e-mail. Try to avoid complex formatting in the article. Charts, graphs, and photos should be submitted as separate PDFs. Electronic photos should not be embedded into a Word document as this reduces their quality.

Photographs and Illustrations which should relate to the article and not be used for advertising nor selfpromotion, should be supplied electronically as high resolution TIFF (*.TIF) or JPEG (*.JPG) files). They should be sent in colour with a resolution of 300 dpi and a minimum size of 100 mm x 100 mm when printed (approx. 1200 pixels wide on-screen). Hard-copy photographs are acceptable provided they have good contrast and intensity, and are submitted as sharp, glossy copies or as 35 mm slides or as scanned high resolution digital images (eg. a 300 dpi 1800 x 1200 pixel *.JPG).

• Computer print-outs are not acceptable.

• Screen captures are not ideal as they are usually not very high quality.

We are living in unprecedented times. Autumn term is usually when teaching staff bring together the various cohorts of pupils in their charge. Now it is a time to ensure they can keep them apart. I imagine there will be members of the teaching profession agonising over whether they have taken enough precautions to protect colleagues and students. There will also be lots of students wondering if they are safe or if they are maybe passing on the virus to teaching staff or family at home.

One thing we can be certain of is that our teaching staff, for all the pressure they constantly work under, are rising up to the challenge, They are leading from the front as always.

I hope you can make time to enjoy this very full edition of Networking and maybe you will find something of interest that will induce you to put pen to paper and submit a response.

John Clawson Editor

Captions

Each photograph or illustration should have a selfexplanatory caption. If you do not supply images, you may be asked to submit suggestions and possible sources of non-copyright material.

Who owns copyright to the article?

You do but Networking - Catholic Education Today owns copyright to our editing and the laid-out pages that appear in the magazine.

What are some hints for success?

As much as possible, talk about your experience rather than pure theory (unless discussed in advance) Use specific examples to illustrate your points. Write the way you’d talk, with a minimum of jargon. Near the beginning of the article, include a paragraph that states your intentions. Don’t be subtle about it: “This article will...” is fine.

Closing Date for Copy - Volume 22 Issue One – Winter Term 2021 edition - Copy to Editor by 11th December 2020. Published to schools 11th January 2021.

Our contributor, John S. Harris, concludes this challenging article by saying ‘the Catholic sector…has focused on the perceived right of Catholic families, not on serving the poor and the marginalised. In doing so, it has allowed its schools to become conduits for the recycling of privilege.’

His argument is supported by an impressive range of research and analysis (see references). This is not a polemic, it is a serious, small scale research.

While international research shows that his conclusion is, unfortunately, true for quite a number of countries worldwide, it has always been assumed (and proclaimed) that

in England and Wales, Catholic schools are ‘first and foremost in the service of the poor, those who are deprived of family help and affection and those who are far from the faith’. But is this true?

Readers of this article are invited to send their reactions to what John S. Harris has written. Please send your views (800 word limit) to me at crdce@stmarys.ac.uk

Professor Gerald Grace CRDCE Professor of Catholic Education

St Mary’s University, Twickenham TW1 4SX

London UK

In 2016, a manifesto of the Catholic International Education Office proclaimed that “the Catholic school is an inclusive [and] … non-discriminatory school, open to all, especially the poorest”. “If it is to continue its mission”, it went on, it may encompass “mainly, or even exclusively” pupils of other faiths and none (OIEC, 2016, pp 3-4).

The manifesto echoed many of the points arising from The Catholic School, issued in 1977 as a supplement to the Second Vatican Council’s Declaration on Education. Catholic schools were not to be only for Catholics; rather, it decreed, “in the certainty that the Spirit is at work in every person, the Catholic school offers itself to all, non-Christians included” (Garrone, 1977, para 85).

Voicing a concern that, in some countries, Catholic schools had strayed from their mission to the poor and were showing elitist tendencies, the document re-stated the Church’s over-riding commitment to “the poor, those who are deprived of family help and affection, or those who are far from the faith” (ibid, para 58).

Finally, The Catholic School issued an appeal to Episcopal Conferences to “consider and develop these principles which should inspire the Catholic school and to translate them into concrete programmes” (ibid, para 92).

How faithful has the Episcopal Conference of England and Wales been in answer to this call? How inclusive are our Catholic schools?

PS. In your responses, please indicate if you are willing to have these printed in the journal at a later date, or if they are to remain confidential. Please endorse your response with a 3 for one of the following:

a. Can be printed, with name of writer, name of school and location of school.

b. Can be printed with name of writer only.

c. Can be printed but with no identification d. Confidential only.

Thank you.

Association, and the National Small Schools Forum.

For several years he co-ordinated the Leicestershire Educational Action Research Network (LEARN).

Following retirement, he conducted a research project for the DCSF (as it then was) into formal small school collaborations.

He currently chairs the governing body of a Catholic primary school on the east coast.

The English Catholic school system has evolved in response to the social and political milieu in which it operates. It voices its commitment to helping the poor and the marginalised, and it has a rich tradition of integrating immigrants into civil society. But much has changed. Catholics have long outgrown their status as outsiders. Now, in common with those from other Christian denominations, Catholics are likely to have a higher occupational class and a larger household income than the population at large (Oldfield, Hartnett and Bailey, 2013, pp 33-34).

This relative affluence is reflected in the socio-economic composition of Catholic schools (ibid, pp 31-32). The standard indicator of children’s material deprivation is their eligibility for free school meals (FSM). As a threshold measure, it is open to criticism as to how accurately it identifies true hardship. Nevertheless, it is a widely used and generally trusted proxy, and remains the best indicator of pupil poverty that we have.1

The statistics show that Catholic schools have a free school meal take-up that is significantly lower than other schools –11.6% compared with 13.6% nationally. They also take a much smaller proportion of the most vulnerable children – 11% fewer children who are ‘looked after’ (that is, in local authority care) and 14% fewer children who have an education, health and care (EHC) plan or equivalent (CES, 2018, pp. 25-27).2

The Catholic Education Service has asserted that “research by St Mary’s University … has concluded that certain ethnic groups are less likely to claim FSMs due to a range of cultural reasons and that these particular groups are over-represented in Catholic schools” (ibid, p 25). In fact, the report referred to makes no such claim, stating that “the data gathered … were too limited to be able to draw a direct link between migrant parents and likelihood of FSM takeup”. (Montemaggi et al, 2017, p 10).

Moreover, the DfE report Pupils not claiming free school meals has conducted extensive and detailed research into this area. Using HMRC benefits data, it tracked disparities between FSM eligibility and registration. This revealed that nationally 14% of children eligible for FSM are not claimed for, but that there were significant differences at regional, local and school

level. Pupils in wealthier areas were less likely to be claimed for, even though they were eligible. The effect was replicated at school level: eligible pupils were less likely to be claimed for if their school had a low FSM rate (Iniesta-Martinez and Evans, 2012, pp 11-12, 15).

The DfE report also provided details of variations in registration rates among different sectors of the population. Contrary to the CES assertion, it was eligible white British families who were least likely to claim, whereas eligible pupils whose first language was not English were more likely to claim (ibid, pp 17-18).

As the CES points out, Catholic schools have much larger catchment areas than other schools, and children tend to travel greater distances to them. These children often displace applicants living close to the school, who are more likely to be disadvantaged. Moreover, there are considerable costs – in both time and money – contingent on attending a school outside one’s immediate locality. These include the ability to pay for transport and additional childcare, as well as the general complexity of day-to-day planning familiar to any parent. Together, they are likely to be beyond the resources of the most needy families, particularly since the loss of subsidised school transport (Andrews and Johnes, 2016, pp 14-18, 24-25; The Tablet, 29 August 2014).

Catholic schools take a higher percentage of pupils from ethnic minority backgrounds than other schools. More specifically, the CES annual census shows that Catholic schools in England take much higher proportions of pupils from black African, black Caribbean and black British communities, and also from white nonBritish categories. By contrast, they take a lower than average proportion of pupils from Asian backgrounds (CES, 2018, pp 21-2).

Different minority ethnic communities tend to cluster in our larger towns and cities, often following traditional migration routes, and are to be found especially in London. These are areas where Catholic schools are also commonly located, so it is to be expected that children from ethnic minorities are more likely to be enrolled in them. CES census figures show that schools in the dioceses of Westminster, Southwark

and Brentwood (that is, the three Catholic dioceses serving London) have particularly high concentrations of children from ethnic minorities (more than two-thirds in the cases of Westminster and Southwark). By contrast, six dioceses (including Liverpool and Plymouth) have less than one-quarter of their pupils from a minority ethnic background (ibid, p 44).

It is too easy to make careless assumptions about ethnicity. Children whose families self-identify as being from an ethnic minority will not necessarily themselves be migrants. Most will be from an established minority ethnic community, where the children and maybe also the parents have been born in this country. Their experience is likely to be very different from that of people who have recently arrived on our shores, perhaps with very little knowledge of our language or culture. Many people from minority ethnic communities are living in hardship and working in low-paid and insecure occupations. But others are highly skilled and in well-paid employment (Dustmann, Frattini and Theodoropoulos, 2010, pp 2-4).

Statistical information needs to be animated by real life examples. Aggregated data may well disguise wide variations, including outlying cases that show major differences from the norm. Moreover, a dataset of all the nation’s schools will frequently obscure regional differences, contrasts between urban and rural areas, disparities attributable to cultural or ethnic factors, and many other variables. Unique features can be overlooked; nuances can be missed. Speaking about faith schools as if they are all the same is highly misleading.

Individual Catholic schools may fail to recognise themselves from the description of ‘average’ characteristics; indeed, they may feel seriously misrepresented. There are plenty of Catholic schools wrestling with a range of acute social problems associated with poverty – urban decay, endemic unemployment, family breakdown, widespread drug abuse, and so on. Such schools can get lost in the overall picture because they are markedly outweighed by other schools which show the opposite tendency.

Nevertheless, it remains true that, for many parents, Catholic schools have become associated with prestige and exclusiveness. In turn, ‘top’ Catholic schools are tempted

to parade their elite status, taking them increasingly far from their mission to serve the poor. How this has happened is largely a product of the context in which schools are now required to operate.

The Education Act of 1988 ushered in an era of parental choice that rapidly promoted competition between schools. Rivalry became more intense with the increasing availability of league table data. It enabled some schools to market themselves as ‘better’ than others, when in fact the differences between them may have only reflected the relative affluence of their intakes (Andrews and Johnes, 2016, p 39). The pattern has become self-perpetuating: schools judged as ‘outstanding’ are admitting ever fewer disadvantaged children. These instead become more concentrated in schools that have been graded as failing (Burgess, Greaves and Vignoles, 2020, pp 7-10; Gadsby, 2017, pp 17-18).

Nationally, the system cannot be said to be working well. One in ten children fail to get their first preference of primary school; in London it is much higher (and in some London boroughs it is one in four). At secondary level, the position is even worse, with one in four failing to gain their first choice in many urban areas, and one in three in London. Of those who appeal, only one in seven are successful; for disadvantaged children, the proportion is significantly lower (Hunt, 2019, pp 7-8).

The scramble for places has led to the emergence of schools that exhibit a high degree of social selection. For example, there are well over a thousand schools where the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals is between 10 and 40 percentage points lower than that found in the neighbourhoods from which they recruit. Many of these schools are Catholic, and are to be found in major cities throughout the country, especially in London (Allen and Paramashwaran, 2016, pp 1-3; Cullinane et al., 2017, p 14).

Black families are more likely than white families to choose a faith secondary school (the large majority of which are Catholic) but are less likely to gain a place there. Similarly, a disadvantaged child who applies

to a faith school is significantly less likely to be admitted than a more affluent child living nearby (Weldon, 2018, pp 8 and 19)3

The claims and counter claims relating to the inclusiveness and effectiveness of Catholic schools are a direct result of the marketisation of the education system. In order to ensure their place in the pecking order, schools are forced to engage in a constant struggle for status. For many faith schools, this pressure has corrupted the admissions process, leading to a degree of social sorting which may be unintended but is nevertheless real.

The key oversubscription criterion for entry to a Catholic school is baptism, often augmented by the requirement to demonstrate religious observance. This makes most children ineligible, but it doesn’t prevent deception. A number of investigations have provided evidence of widespread abuse of admission arrangements, such as seeking to secure a place by feigning religious commitment (Francis and Hutchings, 2013, p 24; Montacute and Cullinane, 2018, pp 22-23).

Research by YouGov for the Westminster Faith Debates casts further interesting light on parents’ motives for choosing faith schools. The survey showed that, by a wide margin, the two most important factors in choosing a school were ‘academic standards’ and ‘location of the school’. By contrast, the two least important factors, with very low scores, were ‘grounding in a faith tradition’ and ‘transmission of belief about God’; only 3% chose the latter. It would appear that, even for Catholic parents, Catholic schools are chosen not for their Catholic ethos but for their reputation for high standards (Woodhead, 2013, pp 2-3).

Current government policy – despite some vacillation – is that new schools of a religious character must make available half of its places irrespective of faith. This is based on a concern that schools that cater for a single faith community will inhibit social integration. It is a concern shared by many Catholics and, indeed, supported by Vatican guidance, as we have seen. However, the response of the bishops has been to refuse to open new schools on the grounds that it would mean turning away children because they were Catholic.

The term ‘faith cap’ is misleading. The ‘cap’

does not impose a quota of children of a particular faith, which cannot be exceeded. Rather, it prohibits these schools from selecting more than half their pupils on the basis of religion. Children of the faith may still be admitted under the criteria for selecting the other half. In practice, the number will vary, depending on the popularity of the school4

This ambivalence was illustrated in an interview with Paul Barber from the CES, published in the TES (28 October 2016). He stated his personal opposition to “schools of 100% one faith”, noting that having children of other faiths in a Catholic school was “a real blessing” and that “we want to have the spaces to welcome them” (TES, 2016).

What Barber did not say, however, was that the offer of places for non-Catholic children is provisional – that is, they are only given places that are not wanted by Catholics. In areas where competition for places is most intense, there are unlikely to be any places for non-Catholic children.

The Vatican report “Education today and tomorrow: Challenges, strategies and perspectives” (2015) states that “Catholic schools … aim for quality in their students’ education, but their concern should not be limited merely to polishing their good reputation”. “The real test of whether their service is authentic”, it continues, “is their attention to the poor and concern for those in disadvantaged circumstances. There is always the risk that we forget the poor; this calls for maximum vigilance” (Responses to the questionnaire of the Instrumentum Laboris, 2015, pp 41-42).

Regrettably, the Catholic sector has been caught napping. In response to the manifold changes of the past decade, it has focused on the perceived rights of Catholic families, not on serving the poor and the marginalised. In doing so, it has allowed its schools to become conduits for the recycling of privilege.

References

Allen, R. and Parameshwaran, M. (2016). Caught out: Primary schools, catchment areas and social selection. [online] The Sutton Trust. Available at: Caught-Out_ Research-brief_April-16.

Andrews, J. and Johnes, R. (2016). Faith

schools, pupil performance and social selection. London: Education Policy Institute.

Burgess, S., Greaves, E. and Vignoles, A. (2020). School places: a fair choice? School choice, inequality and options for reform of school admissions in England. London: Sutton Trust.

Catholic Education Service Digest of 2018 Census Data for Schools and Colleges in England. (2018). London: Catholic Education Service.

Catholics hit hard by end of free faith school transport. (2014). The Tablet. 24 August.

Cullinane, C., Hillary, J., Andrade, J. and McNamara, S. (2017). Selective Comprehensives 2017: Admissions to high-attaining non-selective schools for disadvantaged pupils. London: Sutton Trust.

Dustmann, C., Frattini, T. and Theodoropoulos, N. (2010). Ethnicity and second generation immigrants [online].

Francis, B. and Hutchings, M. (2013). Parent power? Using money and information to boost children’s chances of educational success. London: Sutton Trust.

Gadsby, B. (2017). Impossible? Social mobility and the seemingly unbreakable class ceiling. London: TeachFirst.

Garrone, Cardinal G.-M. (1977). The Catholic School. Rome: The Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education.

Hunt, E. (2019). Access to schools: the impact of the appeals and waiting list system. London: Education Policy Institute.

Iniesta-Martinez, S. and Evans, H. (2012). Pupils not claiming free school meals. Department for Education.

Montacute, R. and Cullinane, C. (2018). Parent power 2018: How parents use financial and cultural resources to boost their children’s chances of success. London: Sutton Trust.

Montemaggi, F., Bullivant, S. and Glackin, M. (2017). The take-up of free school meals in Catholic schools in England and Wales. London: St Mary’s University, Twickenham.

OIEC (2016). Catholic schools committed to an integral education of the human person, in the service of society. Meeting of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg (official translation from the French).

Oldfield, E., Hartnett, L. and Bailey, E. (2013). More than an educated guess: Assessing the evidence on faith schools. London: Theos.

Penney, B. (2019). The English Indices of Deprivation 2019. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government.

Responses to the questionnaire of the Instrumentum Laboris. (2015). Educating today and tomorrow. Rome: Instrumentum Laboris.

TES. (2016). Catholic education chief says total religious segregation in schools is “dreadful.”

Weldon, M. (2018). Secondary school choice and selection: Insights from new national preferences data. Department for Education.

Woodhead, L. (2013). New poll shows the debate on faith schools isn’t really about faith. [online] Westminster Faith Debates. Available at: WFD-Faith-Schools-PressRelease.

Notes

1 The Catholic Education Service (CES) persists in the view that the Indicators of Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) provides an alternative, and more accurate, test of pupil poverty. However, the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government warns that the IDACI is unsuitable for this purpose, since it measures deprivation in neigbbourhoods, not in schools. It is therefore unable to distinguish between those children who come from deprived families, and other children who live in an area of high deprivation but are not themselves deprived (Penney, 2019, pp 3-4).

2 The national comparative percentage for looked-after children is omitted in the CES data, and the comparative percentage of children with an EHC plan is misleadingly described as “marginally below” the national figure.

3 This is perhaps a surprising finding, given that children from minority ethnic communities are over-represented in Catholic schools nationally. The explanation lies in the fact that they tend to form a higher proportion of the population in urban areas (especially London), where most Catholic secondary schools are sited.

4 Not all Catholic schools adhere to a strictly ‘Catholics first’ ruling. There are a very small number of Catholic schools which reserve a proportion of their available places for non-Catholic children in their local area. The new Catholic voluntary aided primary school in Peterborough will be one of these.

The many people who were unable to attend this important conference, are indebted to the speakers and organisers for publishing such a full account of the proceedings.[1] Having access to this impressively coherent, informative and balanced collection of papers will provide an invaluable and lasting resource for students of Catholic education.

The depth and breadth of the experience and expertise of this group of Catholic lay people is in itself notable as exemplifying the post-conciliar Church coming of age. One is tempted to speculate that the spontaneity of the pervasive freedom of expression may well have benefited from the absence of an ‘official’ Church voice and is all the more authentic for it. Most commendably, the reader is invited to weigh up the range of arguments and accounts and draw her or his own conclusions.

Of the contributors, Margaret Buck is in no doubt that Voluntary Aided status, from a different historical period in our country’s history, offers a great deal more long-term security than the Academy status that sits comfortably within the neo-liberal capitalist, market orientated economic philosophy of the late 20th, early 21st century. Raymond Friel makes a case for the degree of autonomy within the Academy structure to develop a thoroughly coherent and very distinctive Catholic ethos based upon our Gospel’s soundest values.

Louise McGowan’s searingly honest selfexamination, elicits this telling admission about the turmoil of the early stages of academisation: ‘I do not believe that the governors and out-going headteacher had realised what they were signing up to.’ Its personal effects leading her to conclude: ‘I was so busy dealing with what was around me that I didn’t notice what was happening to me.’

Clearly the profound issue arising in

this report and from elsewhere, is the degree of State control over the nature of school academies, their governance and management and the expectations of teachers. It might be argued that the State has set up proxy corporate enterprises to manage these institutions, synchronised by its own Government Department, to pursue a utilitarian Government policy with little accountability. However those institution leaders and their teams of teachers are oppressively held to account.

The authentic experiences of those teachers was understandably missing at this seminar. But their vocation, professionalism and career in Catholic Education has moved them, from a familiar Voluntary Aided Local Authority pattern to this different one.

Reflecting on the whole Academy initiative from a historical perspective, there would seem to be a less than convincing display of resolve in securing the best possible outcome for the Church at critical stages of educational legislature. Sadly, the lack of a hierarchical unity of response to Academisation from across the diocesan spectrum from total adoption to total refusal and everything in between, has more than one precedent which could quite reasonably be interpreted as the story of diminishing control of our Catholic schools.

That dual partnership has been slowly ebbing away since the mid 70s, with the final implementation of the 1944 Act at the raising of the school leaving age to sixteen. The party political consensus over education broke, assisted by decisions for a comprehensive schools programme.

However the seeds of a market based education were also being sown with one of the early examples being the publication of ‘A Framework for Choice’ in 1967.[2] A major contribution in the book was by A.C.F. Beales, a prominent Catholic academic, who dwelt on Cardinal Bourne’s proposal from 1926 advocating a form of education voucher for each pupil. Bourne’s motive was far from ‘free market’ but sought to ensure a fair distribution of state resource to Catholic schools. Beales warned that ‘one of poverty’s degradations is unavailability of

by Peter Boylan KSG

choice.’[3] That these two leading Catholic figures are together is a coincidence of history, as both played a significant parts.[4]

In 1926, the Hadow Report made proposals for the institution of secondary education for all pupils and in many ways was the precursor of the 1944 Education Act. However, the proposals received a very mixed reception from the Voluntary Sector, largely Catholic schools who faced either huge costs in renovating or building schools, or facing the compulsory transfer of pupils to Council schools. As a part of the following campaign, the Hierarchy, led by Cardinal Bourne in a document circulated to the Hierarchy entitled ‘Principles to be Remembered’,[5] offered among others, three of the principles relevant to current discussions:

• It is no part of the normal function of the State to teach,

• The teacher is always acting ‘in loco parentis’ never ‘in loco civitatis,’

• The teacher never is, and can never be a civil servant and should never regard himself or allow himself to be so regarded. Whatever authority he may possess to teach and control children, and to claim their respect and obedience, comes to him from God through the parents.

The concept of ‘in loco parentis’ was enshrined in English case law as long ago as 1893 when a legal judgement expressed that ‘the school master (sic) was bound to take such care of the boys in his care as a careful father would take of his boys.’ This judgement was confirmed in 1906 in a pastoral letter by the Bishop of Salford, Dr. Casartelli who added a number of similar legal statements. It was confirmed more recently in the Child Protection Act of 2003.

Bourne’s successor’s Cardinal Hinsley, needed to face the calamities of WW2 and the preliminary negotiations leading to the 1944 Act. In January 1945, A.C.F. Beales analysed what he saw as the failure of the Catholic body to convince government of its case.[6] His concerns led him to pose the question ‘What about next time?’

He went on to outline a programme of action that would have secured a more promising debate with government while critical of the Church’s approach to education. He observed that the ongoing debate following the 1944 Act among the Catholic community was focussed on costs, while any education value was ignored. While proposing the founding of a Trust Fund to secure finance as well as a crisis fund to meet the present situation, he questioned academic standards within Catholic schools, and the lack of any Catholic academia which would have been able to research and validate some of the accepted premises. ‘We seldom ask ourselves whether the formula “Catholic children in Catholics schools taught by Catholic teachers” means Catholic education. A complete non sequiter’ he wrote. Bemoaning the lack of continuing formation for the laity he diagnosed that their fault is not knowing how to study, but we teachers do not know what this is for the non-professional adult. “And so, the priceless heritage of Catholic teaching passes them by; the laity lack a formation; the clergy distrust their initiative; and we all go round and round in an endless circle.” The delusions outlined in 1944 are in many ways still with us, seventy-five years later.

During the debates on a Catholic response to the Grant Maintained Schools’ initiative in 1988, the then Bishop Nichols could express the deep reservations and unease of the Bishops’ Conference of ‘attempts to organise education on the principles and practice of an open market economy.’[7] However, that cohesion among the Hierarchy was broken for reasons which the late Dominic Milroy OSB would refer to as ‘the problem of the federal Church.’ Witness the different responses to the Grant Maintained School initiative and now to Academisation among the Hierarchy and a recurring theme emerges that weakens the body as a whole when the centre cannot hold. Can there ever be a policy among

the Bishops that strengthens all parts of the enterprise of Catholic Education in the country?

Bookshelves are littered with the proliferation of post-conciliar publications, reports and exhortations with recommendations and programmes for action. ‘The Easter People 1980’, ‘Signposts and Homecomings ‘81’, ‘Servicing Catholic Schools, ‘88’, ‘A Struggle for Excellence’ ‘97’, ‘Foundations for Excellence ‘99’, ‘The Common Good in Education ‘97’, to name a few of the most prominent sources of unfulfilled promise.

In the report, Gerald Grace comments that this challenge concerning MATs and Catholic Education ‘alerts the whole Catholic community to focus on this important question’; John Sullivan identifies ‘the need for constructive engagement in society by lay Catholics,’ who must ‘display professional competence as well as devotion, if they are to deserve respect and are to carry out their mission.’

In the exhortation of Pope Francis, ‘Christus Vivit’[8] there is a section on Youth Ministry. The model being signalled is captured in a reflection on the journey of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. Those disciples are shown how to recognise what they are hearing; to interpret these events and then to choose what to do next. Recognisable as the scriptural source of the Young Christian Workers’ analytical mantra of ‘See, Judge, Act’ was attributed to the far sighted Cardinal Cardijn’s capturing of the essence of Catholic Social Teaching. Cardijn, one of the giants of Vatican II, is credited as playing a major part in the formation of the young Argentinian priest Jorge Mario Bergoglio.

While we now have an academic and research community, as well as a measure and recognition of the quality of Catholic schooling, there is still the need to ensure Catholic adult lay formation and so engage

in the debate on social and political issues in the market place. Similarly national capital finance is a serious issue and one which is a factor in some dioceses for taking up initiatives that include a financial incentive.

The declining influence of the Church as a partner in shaping the country’s education system is surely a matter of the gravest concern. One might ask, as Beales did in 1945, what about next time? What comes after Academisation and how we are to ensure that we are capable of more than a pragmatic accommodation, remains a matter of some considerable concern.

Focussing on the costs again at the expense of a coherent argument about the inherent value of education is no more valid today than it was in 1944. What we can point to as a most encouraging development since Beales lamented the absence of a Catholic academic research and validating facility, is the emergence of an increasingly influential body of academic work, shared across the Catholic world, coming from these islands.

However, the future shape and content of Catholic education cannot be a matter simply for these interested educators. A secure future remains entirely dependent upon a unified hierarchical conversation engaging a Catholic community whose allegiance to our schools has never faltered.

[1] Conference Report. ‘Are MATs and Academies a Threat to the Future of Catholic Education In England and Wales? Ed Sean Whittle, Networking publications obtained from willieslavin@aol.com

[2] ‘Education, A Framework for Choice’ Ed Rhodes Byson, IEA 1967

[3] ibid

[4] Bourne, Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, 1903 to 1935: Beales became Professor of History of Education, King’s College London.

[5] This document is quoted in full in ‘The Education Question’ T Quirk, private publication 1943.

[6] ‘Some Delusions in Catholic Education,’ ‘Illuminating Facts: The Schools and the Sceptics’ Beales, address to Leeds Newman Association Easter 1944. Published Bradford CPEA January 1945.

[7] Address to Conference on Grant Maintained Status, ACSC London 1993

[8] ‘Christus Vivit’ a Post-synodal Apostolic Exhortation to Young People and the entire people of God’ Pope Francis 2019 CTS publications.

The Research and Development Editor of Networking Professor Gerald Grace, adds his reflection on this contribution to the debate on academisation.

i. ‘It is so important when considering present challenges, to set them in the context of history. This reminds us of the valued principles of the past (not to lose them) and also the mistakes of the past (and not to repeat them).’

ii. ‘ In my view academisation (in its current

forms) represents a corporate takeover of Catholic schools by subtle and indirect means and the whole Catholic community needs to think more deeply about it. It is not an evidence based policy, but rather an ideological project arising from the political ambitions of one man, Michael Gove. It threatens to extinguish a valued

principle of the past, Voluntary Aided status (with relative autonomy) and to replace it with greater power for whoever is Secretary of State for Education in the future. I am surprised that so many of our Bishops cannot see this political strategy.’

During these unprecedented times, New Hall has come together to support the nation and local community in the most remarkable of ways. Reflecting the School’s ethos of care and service, New Hall has taken action with many initiatives over the past few months in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In addition to producing over 200 face shields for the School’s local hospital, Broomfield Hospital, New Hall School has donated a large amount of protective equipment to local care homes. These initiatives have been commended by new outlets: https://bit.ly/39uxn7H. Principal, Katherine Jeffrey, said: “The selflessness and hard work of the staff has provided some much-needed relief to the local community and The School’s Art, Design & Technology Department have done a fantastic job designing and manufacturing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for frontline key workers battling the virus.”

New Hall’s award-winning voluntary service, NHVS, has continued its 40-year tradition of giving service to those in need in the local community. Whilst clubs such as lunches for the elderly and support groups for vulnerable adults have been unable to run in person, New Hall has provided ongoing support and care, through home deliveries, Zoom/Skype calls and letter writing to all the members of its weekly action groups.

Various members of the community have participated in several sporting challenges to raise money for NHS Charities Together. Isla-Rose Onions (Year 1) ran 26km over the month of May, raising a total of £870,

including Gift Aid. Miss Beatty, teacher of English, took part in the 2.6 challenge, walking 2.6 miles for 26 days to raise money for the Little Edi Foundation, despite being eight months pregnant!

Accompanying these efforts, the School’s Senior Prefect Team banded together and walked/ran/cycled 5614km (approximately the distance from New Hall to Times Square in New York) over a period of 30 days, to raise money for NHS Charities Together. James Alderson, Head of Sixth Form, said: “The challenge was an excellent opportunity for Sixth Form students to keep fit and stay connected, while serving the community. The team raised a total of £3,604 and covered an impressive distance of 5727km!”.

The Art Department has contributed to the NHS Heroes Portrait Initiative, with a dozen students and various teachers creating over 60 portraits of Key Workers, to be exhibited in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in due course.

New Hall School remained open to Key Workers’ children continually from March. With a plethora of activities on offer, from golf lessons and croquet, to painting and animal welfare, the School’s ‘Key Worker Childcare Scheme’ provided much-needed support to NHS and frontline Key Workers, as well as ensured that the children continued their studies and selfdevelopment.

New Hall’s large and vibrant Chaplaincy has continued to support the prayer life of the School and local community. Fr Martin Hardy, New Hall’s Chaplain, has regularly live-streamed Mass from the magnificent and historic Chapel.

Principal, Katherine Jeffrey, said: “New Hall’s Chaplaincy Team and Theology Department have created an imaginative and moving

set of ‘Remote Liturgies’, which have been valued by our community during these unprecedented and difficult times. These have helped people to stay connected, as well as being supported in prayer. This has been especially important at a time when many have suffered isolation and loneliness and others are struggling with illness and bereavement.” New Hall is also creating a memorial orchard in the fields in front of the stunning former Tudor palace that forms the School’s main building.

New Hall School was the first independent school nationally to sponsor a state primary academy. Throughout lockdown, New Hall continued with its public benefit work running the successful New Hall MultiAcademy Trust.

Year 7 pupils from Saint Paul’s Catholic High School in Wythenshawe, Greater Manchester took part in a competition to design a flag for Antarctica. The wonderfully colourful flags were then taken to Antarctica as part of a project with Antarctic scientists.

The aim of this initiative is to inspire new generations about the Antarctic and Antarctica Day.

Mrs Helen Allsopp, Head of Geography at Saint Paul’s, explained: “Following a Geography lesson about Antarctica, the pupils were asked to design a flag for the Antarctic – as it does not have its own –based on what they have learnt. The flags were taken to Antarctica by the scientists who have sent us some fantastic photos of the pupils’ pictures in Antarctica.”

On December 1st 1959, 12 nations signed the Antarctic Treaty, a document declaring that Antarctica would be off limits to military activity and setting it aside as a place for peace and scientific discoveries. As of 2010, December 1st has been celebrated each

year to mark this milestone of peace and to inspire future decisions. It is hoped that the celebrations can be extended worldwide through the Antarctic Flags initiative; giving new generations the opportunity to learn about the Antarctic Treaty and to share, interpret and cherish the values associated with Antarctica!

“This really is a remarkable achievement, we are extremely proud of those students who took part in the project. They enjoyed the work and showed so much enthusiasm for the topic,” commented Mr Alex Hren, Head Teacher.” We received some amazing entries from our Year 7s for the competition – well done to all those who took part!”

Inaugural Conference at the Convent of Jesus and Mary Language College, London; 12 March 2020:

By Carolyn Malsher and Louise McGowan

‘Following Pope Francis’s lead, how should Catholic education serve the poor, regardless of whether or not they are Catholic Christians?’

This was the question we posed to speakers and delegates at our oneday conference in March, just before COVID-19 and lockdown posed a whole new set of challenges around education and equity.

We were thrilled to have an esteemed lineup of keynote speakers in Professors Gerald Grace, Stephen McKinney and Richard Pring. In combination these academics represented a good century of research in Catholic education.

Professor Grace took us back to the seminal work The Catholic School issued by The Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education in 1977. He reminded us that the ethos of Catholic education has always been the ‘preferential option for the poor’ and, as Pope John Paul II had clarified, this was “not limited to material poverty but encompasses cultural and spiritual poverty as well.”

Following on from Professor Grace’s historical overview we focused in on more recent developments with Professor McKinney’s studies into the role of Catholic schools in addressing specific injustices such as food insecurity and life chances for those living in areas of deprivation. He touched on the connected issue of sectarianism extant in his home town of Glasgow and how that had been and was being addressed; a subject which drew an interesting discussion from the floor on parallels with delegates’ experiences.

After a thought-provoking morning of keynotes, delegates were able to choose from a range of short papers in parallel

sessions based on their specific areas of interest.

Dr Margaret Buck offered definitions of poverty originating both outside and inside schools, working from her research conducted in state-funded English diocesan schools. She identified material poverty, emotional poverty, and poverty in the faith as being areas of deprivation which may need to be addressed within a Catholic educational setting.

Focusing on primary education, Dr Ann Casson spoke of strengthening the ‘Nexus’ of connections between the home, school and church in order to develop the spiritual capital of pupils, their families and the whole school community. Her presentation was based on empirical research carried out by the National Institute of Christian Education Research (NICER) at Canterbury Christ Church University, which identified some effective approaches such as pastoral care for the whole family, opportunities for parents to share worship and provision of time and space for prayer.

We were pleased to welcome Edward Conway, headteacher at St Michael’s Catholic High School in Watford, one of our partner schools within the Diocese of Westminster Academy Trust. His session focused on the current deficit of social services and the consequences this has had on the de facto position of Catholic schools as an additional support service for vulnerable families. He described what this looks like in practice and how it impacts on schools who are themselves under budgetary constraints. He also gave some helpful pointers towards accessing support from Catholic charities.

Martin Earley looked at the contribution to debate around Catholic social teaching made by two orders of religious fathers; the Dominicans and the Jesuits. He examined the output of their teaching via their academic journals: New Blackfriars

and the Heythrop Journal, respectively. He identified many points of overlap and similar concerns, but noted differences in approach and emphasis, with the Dominicans being more radical and quicker to address ‘difficult’ subjects e.g. MarxistChristian relations, liberation theology and sexual ethics while the Jesuits were more measured and discreet in their criticism of church policy.

The challenging question of whether a selective faith-based entrance policy for Catholic schools is compatible with a social justice ethos was presented by John Harris. The fundamental principle described in the 1977 document is that “In the certainty that the Spirit is at work in every person, the Catholic School offers itself to all, nonChristians included … “ However, school admission policies are often such that the inclusivity this statement implies may be sacrificed, certainly for oversubscribed schools with high uptake from within the Catholic community. The fear of a loss of Catholicity or a dilution of Catholic ethos in schools with a higher proportion of nonCatholic students is, arguably, problematic

and should be addressed with great care and sensitivity.

For full details of John’s research see p8

Dr John Patterson, Principal of St Vincent’s, a specialist school for students with sensory impairment, described his work in forming connections between schools, universities and businesses with the aim of improving the social capital and employment opportunities for visually impaired students. He explained his school’s ‘Common Good’ curriculum and its focus on learning through service while simultaneously promoting opportunities for spiritual discernment.

As a Catholic research school we are lucky to have several practitioner-researchers on our staff, and two of our colleagues presented papers to the Conference. Claudia Paisley, Assistant Headteacher, is contributing to a wider study being undertaken throughout the London Borough of Brent on the underachievement of Black Caribbean students. In her talk on the study she is undertaking within our own cohort of students she examined some of the factors that are emerging to suggest that we as educators could be unconsciously complicit to this issue, which has implications for our stated aims to promote social justice and core Catholic

values. She spoke of how we influence the beginning of a black child’s awareness of themselves and can unconsciously contribute to a crystallising self-view that they are less able, less valued and have less right to a voice.

Our Head of History, Sharon Aninakwa, described the school’s work on a history curriculum that engages with ‘difficult’ histories, and gives our students the language and critical consciousness to understand the impact these histories have on our identities. The school teaches on the basis that history can (and should) be a tool for ‘scholar activism’ where students can confidently seek justice by studying the roots and legacies of injustice. Sharon invited some of her sixth form students to speak to the delegates about what this mode of teaching actually looks and feels like in practise and their voices presented a compelling and much appreciated addition to this paper, amply demonstrating why the Convent was awarded the Historical Association Quality Mark for History Gold Award in 2019.

Outside of the formal sessions we were pleased to offer a ‘poster conference’ during tea and lunch breaks, where our student researchers presented projects they

had been working on during the year. These students were also able and enthusiastic ambassadors for the school, helping with hospitality and conducting guided tours for the delegates of the Convent’s buildings and grounds as well as making visits to lessons. We were incredibly proud of them.

As this was the first ever Research Conference we had hosted as a new Research School, we were grateful to

be working in conjunction with Dr Sean Whittle and the wider Network for Research in Catholic Education (NRCE) community and the support in sponsorship from Willie Slavin and the Networking Catholic Education Trust. Their support, experience and knowledge of the field proved an enormous help in terms of marketing, outreach to interested bodies and the format and organisation of the day.

Finally, we would like to thank our delegates; academics, Headteachers and representatives from Catholic organisations and charitable bodies, for attending and contributing to the many thoughtful and fruitful discussions. Our Conference was luckily timed just prior to the wholescale closure of our schools to the majority of students. As we return to our new, post-lockdown education system, the issues and concerns that we all brought to this day will have been exacerbated and the push for an understanding of and a practical application of social justice in Catholic schools must be prioritised.

making changes to the curriculum, and it could spell

You may have seen in the news recently that the headteacher of every Catholic school in Wales wrote to the First Minister asking the Welsh Government to halt its plans to overhaul Religious Education.

The Welsh Government plans to expand the scope of traditional RE to ‘Religion, Values and Ethics’, removing the academic rigour of the subject and reducing it to an oversimplistic comparison exercise which fails to understand the fundamentals of faith and religion.

The proposals, which were published in May and are currently being rushed through the Senedd, specifically penalise Catholic schools, placing additional and unreasonable legal requirements on them that no other schools have to satisfy, specifically forcing them to teach two separate RE curriculums without any consideration of resourcing impactions this would have for schools.

Such was the strength of feeling among Catholic school leaders that they made the unprecedented decision to write a collective letter to the First Minister directly opposing his administration’s plans, even asking him if it was his intention to damage Catholic education in Wales.

In their letter, the headteachers state that the proposed changes to RE fail to recognise the heritage and deep connection Religious Education has within Catholic schools, and that the Welsh Government’s desire to create a so-called ‘neutral values’ curriculum risked moving towards a homogeneous education system which would no longer recognise children’s legal right to pursue a deep knowledge and spiritual understanding of their own faith as well as those of others.

RE in Catholic schools is grounded in the 2000-year-old theological tradition of the Catholic Church and gives pupils the opportunity to delve into the motivations behind faith, the ability to critically approach the ‘big questions’ of life and the skills needed to analyse the various ‘truth claims’ made by religion. It involves an

in-depth study of scripture, Church texts, and the work of some of history’s most prominent philosophers and theologians from St Augustine and St Thomas Aquinas to St John Henry Newman. This approach creates religiously literate pupils who can understand the language of religion and critically engage with their own faith and that of others.

In other schools, RE looks very different, with many taking a more sociological approach to faith and belief. These approaches tend to observe the practices of different religions from without, rather than engaging with the theological motivations within. This can result in the approach that religion is something that ‘those people over there’ do, with the student as an external observer, rather than a potential participant, engaging in the theological debate. It is therefore unsurprising that those who subscribe to this secular approach to RE want to lump ‘values and ethics’ in with religion, as they believe faith to be just another ‘worldview’.

As with all types of legislation the devil is in the detail, and whist Catholic schools would be allowed to continue to deliver Catholic RE, if a parent demanded their child receive the state-approved ‘Religion, Values and Ethics’ curriculum, the Catholic school would be bound by law to comply. This would be an arbitrary requirement and wouldn’t take into account the financial cost of resourcing two curriculums, the practical implications of how it would actually work, and the principle concerns of a ‘stateapproved’ version of Catholicism being taught in a Catholic school.

Moreover, this requirement to provide two curriculums is only being asked of VA Schools, all of which, bar a handful of Church in Wales schools, are Catholic schools. It is, therefore, no wonder why every single headteacher in Wales saw this legislation as a direct attack on their schools.

The other potentially damaging proposal is the usurpation of parents’ rights as the primary educators of their children, by removing parents’ right to withdraw their children from RE as well as Relationship and Sex Education (RSE).

by

Not only do these rights respect parents’ inalienable role in their child’s education and formation, especially when it comes to dealing with sensitive topics such as these. They have also proved a useful tool in ensuring that schools communicate and engage with parents on key aspects of the curriculum. Our belief in parental primacy means that Catholic schools will always engage with parents over the delivery of RSE, successfully resulting in no pupils being withdrawn from RSE in Welsh Catholic schools last year. But we believe this ‘conscience clause’ is important in other schools, too. Catholic provision in Wales is much smaller than it is in England and for many Welsh Catholics it is simply not possible to send their child to a Catholic school. Many parents of other faiths and none will also face a similar problem.

Hence, while we can be confident that RE and RSE can be delivered in accordance with Church teachings and parents’ wishes in Catholic schools, the same cannot be said for all schools. Therefore, it is essential that Catholic parents maintain the right to withdraw so that all schools must respect and engage with their pupils’ primary educators. This will enable a partnership to be forged to deliver these subjects in a way which takes into account parental concerns.

What can be done to stop these changes?

The Catholic Education Service has been working hard trying to explain to the Welsh Government how these proposals will negatively impact on our schools, but their ears seem to be closed to our concerns. The Welsh Government has also failed to understand the concerns of parents who (according to the Welsh Government’s own consultation report) overwhelmingly rejected many of these changes. Therefore, I urge readers in Wales to contact their local and regional MSs and let them know the strength of feeling there is against these proposals in the Catholic community.

For those reading in England please continue to pray for our brothers and sisters in Wales as they campaign against these potentially devastating changes to Catholic schools.

Assoc. Prof. Lydon, IoE/EHSS presents at an international webinar of the World Union of Catholic Teachers on educating during the Covid-19 pandemic and for the future

Assoc. Prof. John Lydon is a member of the Executive of the World Union of Catholic Teachers (WUCT) which recently organised an English-speaking international Webinar on 12 June 2020 (convened by Flemish President Mr G. Bourdeau’hui) on the theme of ‘to educate in the time of the pandemic and beyond – comparative perspectives’. A French-speaking International Webinar also took place on 22 May 2020. In his welcoming address, he spoke of the disappointment of having to cancel the November 2020 General Congress of WUCT but continued with these positive sentiments:

In anticipation of this better world, UMECWUCT wants to walk, together with you, to ensure that all children acquire foundation skills. UMEC-WUCT wants to give you not only courage, but also wants to congratulate you sincerely for your endeavours. With your help, teachers can break learning barriers, enrich learning experiences, promote transferable skills that today’s children and young people need to become responsible global citizens.

Thanks are also expressed to Giovanni Perrone, Secretary General of WUCT, which was established after the Second World War to enhance international co-operation among teachers and is the only lay teacher body recognised by the Vatican. It also has consultative status with UNESCO.

It was a really interesting time midway through the pandemic to share both professional and deeply personal and reflective experiences of teaching and what it is like for schools during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Presentations were provided by Assoc. Prof. John Lydon, England; Assoc. Prof. John James, St Louis University, United States; Assoc. Prof. Richard Pazcouguin, University of Santo Tomas, The Philippines; Ms. M. Lappin, University of Glasgow, Scotland and Rev. Fr. Adrian Podar, National Theoretical College, Bucharest, Romania and Archbishop Vincent Dollmann, Archbishop of Cambrai and Ecclesiastical Advisor to the WUCT. Dr Caroline Healy, IoE of Education, Faculty of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences provided the plenary sessions.

Assoc. Prof. Lydon, Institute of Education/ Faculty of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, began excellently demonstrating that there are resonances between ecclesiological and educational institutional challenges currently being experienced in England. He addressed three issues currently impacting our schools. These were that schools were closed and gradually re-opening; the impact of online learning and the challenges of home schooling for families. He concluded by speaking about Salesian schools and how they were celebrating the return of all students by highlighting and implementing the core Salesian values of respect (through the provision of quality education), understanding (behaviour and attitudes), affection (personal development) and humour (leadership and management) in practice.

Assoc. Prof. John James from the leading Jesuit St Louis University spoke of the

United States experience and how many Catholic schools, which are largely privately financed through payment of tuition fees, were having to close (as many as 46) due to the pandemic crisis. One principal remarked of Covid-19 and the impact on Catholic schools ‘I’ve seen pockets of greatness and real cracks in the system’. Middle class families can no longer afford to send their children to private schools due to redundancies and are having to visit food banks and James called for the need of adaptive leadership of schools at this time.

Ms. Mary Lappin from the University of Glasgow provided a thoughtful presentation in relation to now schools and place of collective worship are closed, it has provided opportunities for individuals to experience contemplative moments with quieter roads and evenings. There are also those suffering disadvantage with schools closed and schools’ provision of pastoral care via email and telephone is essential, as we experience feelings of loss: loss of certainty and daily routines and loss of companionship due to social isolation. Lappin ended by speaking of the need for resilience and of how this crisis is about how we respond to new changes and challenges in our lives, which is also significant for our spiritual wellbeing with ‘the loss of our assumptive world’.

Assoc. Prof. Richard Pazcouguin, University of Santo Tomas, The Philippines, discussed the significance of our teaching ministries ‘on the frontline’ during community quarantine (lockdown). There are economic challenges to online learning in The Philippines as internet access in remote locations may be poor or non-existent and data packages cost money which people often need to just eat and survive.

Pazcouguin spoke of the psychological challenges faced by his university students and the need for his compassionate counselling online which reminded him of how we are the significant daily presence of Christ in the lives of our students during the pandemic.

Dr Adrian Podar from National Theoretical College in Romania discussed how his institution was a pioneer in online learning. His school has been busy devising resource templates for the rest of Romania. He described the time of the pandemic as one where we can ‘re-connect’ teachers with their students and provide much-needed humour and hope for the future.

Archbishop Vincent Dollmann, Archbishop of Cambrai and Ecclesiastical Advisor to the WUCT discussed the digital divide and the need for all peoples to be integrated into the social media networks. He further spoke of the need to unite in solidarity in our response to the pandemic so social justice and the Common Good could be promoted for all humanity. He said:

A major fact should be emphasised during this pandemic period: economic life was stopped to save lives and doctors, caregivers were applauded like heroes. Our western societies, accustomed to give priority to economic success and profitability, have been able to cope with the crisis and honour the virtues of solidarity, particularly towards the frail and poor. Many people have worked hard to visit the sick or to keep relationships by phone, to help the homeless. Alongside these spontaneous actions, the state or church institutions have been very active. These solidarity efforts, which compete with creativity, are a sign of hope for humanity. It will be even more important to continue in the coming economic crisis period. The teaching of the Social Doctrine of the Church is still relevant and has to be encouraged. We find valuable support in the Pope’s Francis encyclical Laudato Si. The Pope reminds us that everything is linked: ecology, respect for all human life and social justice. These benchmarks appear to be the only valid and lasting answer for the survival and the good of humanity. As if to underline the urgency, the Pope has initiated formation projects, he thus addressed young economists and entrepreneurs to reflect on a more human economy in the spirit of Saint Francis of Assisi, ‘The economy of Francesco’.

Dr Caroline Healy, Secretary General of the Catholic Association of Teachers, Schools and Colleges (CATSC) and Senior Lecturer at St Mary’s University, provided

the plenary and spoke of how the pandemic had provided countries with many shared experiences that unite us all in the World Union of Catholic Teachers (WUCT). This includes the economic challenges for families, especially the disadvantaged ones and the changing behaviour of schools due

to social distancing so they can re-open.

She finished by saying that online learning presents challenges for both students and teachers, but also brings immense opportunities for uniting us all, more than ever before, as we work remotely.

Fifth Cohort of Derry students enrol for Masters Degree in Catholic School Leadership and a new centre for Edinburgh

The MA in Catholic School Leadership team at St Mary’s University was delighted that ten more students from Derry enrolled for the MA in Catholic School Leadership for the Academic Year 2019-2020. This outreach centre continues to go from strength to strength.