Where is the year going? It doesn’t seem that long ago when, back in January, we celebrated the Jubilee Year Launch Day for schools and colleges. A flurry of activity saw pupils and teachers across the nations came together to mark the start of this landmark moment in the Catholic church.

Inviting us to stand in solidarity with people around the world experiencing poverty, injustice and conflict, Pope Francis calls on us in this Jubilee year to be Pilgrims of Hope; to build a better world for everyone, experiencing the joy which comes from taking action together. It’s an invitation to renew our hope, a hope which comes from knowing God loves each one of us.

CAFOD, the Catholic Education Service and the Caritas Social Action Network have come together to provide you with a huge range of creative resources. They’ll support and inspire you and your whole school during this year of Jubilee.

For our Joint Resources Jubilee-schools.org.uk

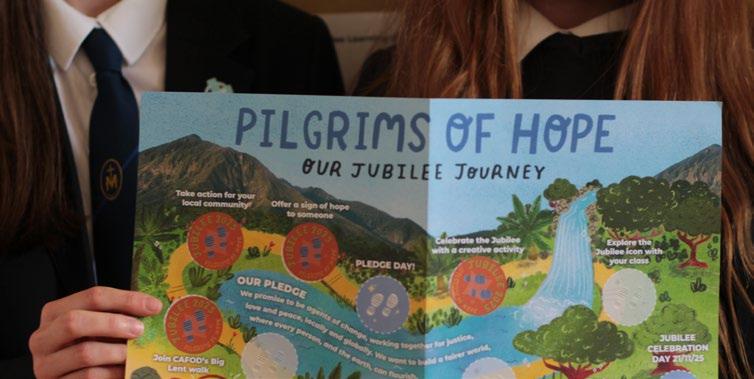

Since January we have seen schools celebrate with many different activities: creating jubilee icons and proudly displaying banners, classroom talks and cross-town pilgrimage walks, painting windows and dressing in Jubilee colours.

“ We're delighted with how schools have responded to the Pope’s call to journey together with hope in this Jubilee Year ” says CAFOD’s Head of Education, Monica Conmee. “ The creativity and enthusiasm have been inspiring” she says.

Encouraged by the success of the launch, it’s now time for the next stage of the journey. In June or July, all Catholic schools are invited to make a Jubilee Pledge to live out Catholic Social Teaching; to stand in solidarity with communities experiencing poverty, advancing justice and harmony locally, nationally, and globally.

A better world needs all of us, and the Jubilee Pledge will be a whole school, long-term commitment to take concrete actions to build a fairer world.

social action network

1. Four lines at the beginning state the pledge itself, which can be recited as a group.

2. The bullet points expand on the vision, detailing what it means to live out the words of the pledge.

3. The final part is over to you! Write down the ways in which your own school community will commit to living out the pledge in the long term.

1. Prepare the whole school community: learn about issues of injustice.

2. Consider how you will embed Catholic Social Teaching at the heart of school life in order to ensure a long-term commitment to building a better world. Write this on your pledge poster.

3. Choose a day in June or July to mark your Pledge Day.

4. Order or download pledge posters. You can order pledge posters from the CAFOD shop: shop.cafod.org.uk or download a copy from jubilee-schools.org.uk

5. Plan how to mark the day: liturgy, learning, activities, symbolic action. Find a suggested plan for the day online.

Download our Pledge Guide to help you write your Jubilee Pledge and plan your Pledge Day: jubilee-schools.org.uk

Pope Francis encourages us to celebrate the Jubilee with ‘deep faith, lively hope and active charity’. How we choose the Jubilee Pledge we make, and how we plan to live it out, can reflect all these things.

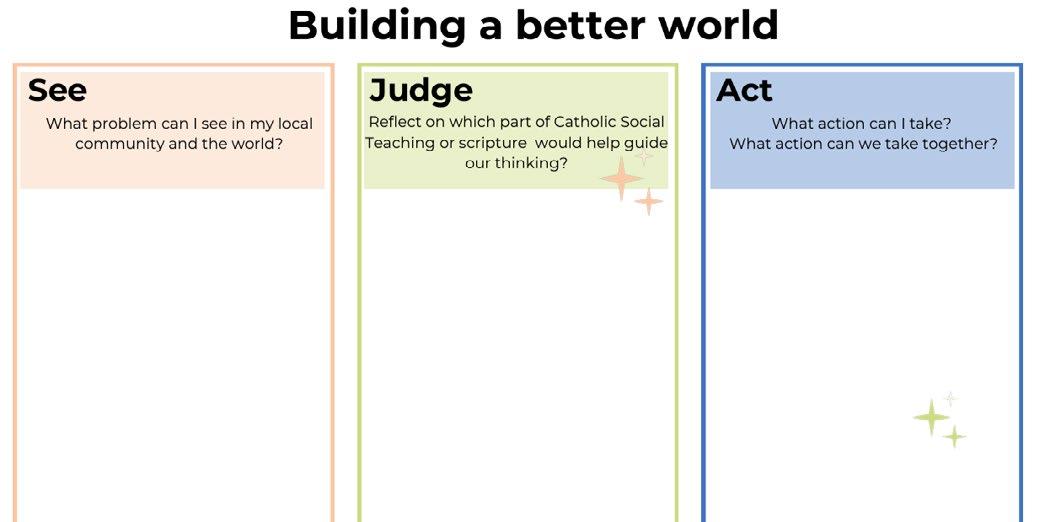

Use the 'See, Judge, Act' resource to help you identify areas that you wish to focus on for your whole school pledge. When preparing your pledge, work with CAFOD and your local Caritas to support the needs of your local community.

Once you’ve decided on your Jubilee Pledge, why not make it a day to remember involving the whole school community? You could celebrate your Jubilee Pledge Day with a Mass, Celebration of the Word or assembly incorporating Jubilee resources,

inviting parents and carers; send pledges home for families to commit to, together; explore issues of injustice through education resources on your Jubilee Pledge Day; have a celebratory fundraising coffee morning or afternoon.

In this Jubilee Year, all Catholic Schools are invited to refresh and renew their mission statement. If this is something you are considering, download the Vision, Values and Mission Toolkit for guidance.

social action network

Raymond Friel OBE

Dr David Torevell

Rev Dcn Michael Bennett

Anthony McNamara

Edmund P Adamus

Jo Stow

Jessica Hall

Dr. Paul Rowan, PhL, STD

Declan Linnane

Dr Sean Whittle

Julie-Anne Tallon

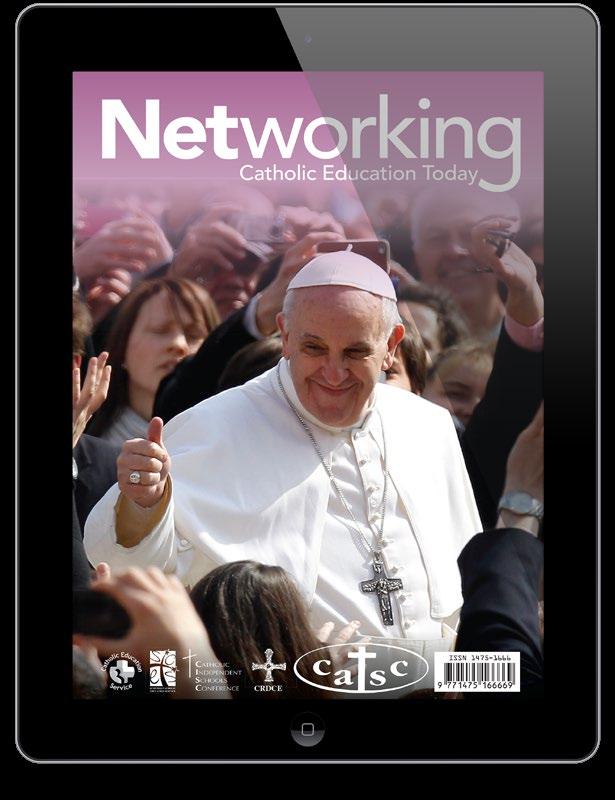

As we began our summer term we did so with a profound sense of both gratitude and mourning. The death of our Holy Father, Pope Francis, marked the end of an extraordinary papacy—one deeply rooted in the Gospel and passionately committed to the mission of Catholic education across the world. In his quiet wisdom and courageous leadership, Pope Francis reminded us that education is “an act of hope” and called Catholic schools to be places of encounter, inclusion, and formation. He championed the role of educators as “builders of bridges,” urging us to form not only minds but hearts—especially among the young. His Global Compact on Education invited us to reimagine our vocation in solidarity with the poor, care for creation, and the pursuit of peace. We remember him now with reverence and resolve, inspired to carry forward the vision he so clearly articulated.

In this spirit of renewal, we’re pleased to highlight our newly updated website: networkingcet.co.uk. It has been designed as a more accessible and vibrant space for sharing resources, fostering dialogue, and promoting good practice among Catholic headteachers and educators. We are grateful to all who have contributed so far and warmly invite your continued support. We hope this issue will inspire and encourage you as we honour the legacy of a remarkable Pope and reaffirm our shared commitment to the Gospel values at the heart of Catholic education.

John Clawson Editor

By Raymond Friel OBE

Raymond Friel is a former headteacher in state Catholic secondary education. He is currently the CEO of Caritas Social Action Network. He is working on his next book, God’s Story: the Vision, Mission and Values of the Catholic School in the 21st Century, due to be published by Redemptorist Publications this autumn.

A knock on the door. it’s Monday morning in school, 8.28 am. Staff briefing is at 8.30 am. I’m fairly new in post as the headteacher of a Catholic secondary school, pacing my office, rehearsing my messages for the staff, some of them blunt. The atmosphere was edgy. Change was needed, but not everybody wanted change and I wasn’t all that secure about how to bring it about. I opened the door with a frown. It was Michelle, one of our young English teachers. “Have you got a minute?” she asked. I made it pretty clear I didn’t have a minute. Staff briefing was in two minutes and couldn’t this wait until later. But she held my gaze and quietly insisted. “I just need a minute.” So she came in and sat down and told me through tears that her sister who had two young children had been diagnosed with a terminal illness and she just wanted to know that she’d have some support from me.

I asked the deputy to do the staff briefing. We sat with cups of tea and she told me what was going on, while I listened, trying not to interrupt with the wrong words. I offered Michelle whatever help she would need to support her sister and her family in the difficult months ahead. She thanked me and went off to teach. Ten years later I left that school, and I got one of those very big farewell cards with dozens of scribbled messages from staff. There was a message from Michelle thanking me for the time I helped her when her sister was ill and had died. That was what stayed with her.

That taught me an important early lesson in leadership. Schools are very busy places and leadership in school is hard at times. You can lose yourself in the daily tasks and your attention can be dominated by the stressful situations and critical incidents you have to deal with. In a Catholic school, however, attention to each other should be at the heart of the mission, inspired by our vision of the human person, our anthropology, which is that we are made in the image and likeness of God. Made in love and for love, made to be relational, to grow in community, with a divine origin and an eternal destiny. The grandeur of this vision is sometimes hard to hold on to on a Monday morning in school. But it’s always there, waiting for us to re-focus.

Simone Weil, the great French philosopher, said, “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love” (1). Attention, like prayer, is a form of generosity. Weil called it the purest form of generosity. In some of the leadership courses in those days, there was a lot of focus on the importance of visibility. Be seen: in the corridors, the playground, the classrooms. That’s not unimportant, but it feels to me now too much like surveillance. Now I’d want to stress the importance of presence as a key characteristic of leadership in a Catholic school, indeed for any role. Presence as

a precondition for attention and encounter. In his homily for the opening of the synodal path, Pope Francis said, “Jesus did not hurry along, or keep looking at his watch to get the meeting over. He was always at the service of the person he was with, listening to what he or she had to say…We too are called to become experts in the art of encounter”(2).

These encounters with others are, If you like, sacramental. In On The Way to Life, a forgotten gem published by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference in 2005, the authors reflect on Vatican II’s theology of grace which “allows people to understand the sacramental nature of their ordinary lives, hence the universal call to holiness…In a sense, every member of the Church – not just the ordained priesthood and hierarchy – becomes a minister of grace and has the possibility of mediating it in and through their lives” (3), You won’t find that on many job descriptions for leaders in Catholic schools: ministers of grace. Yet, that is what we are, or can be. That is what we are called to be.

This is also sometimes referred to as the Catholic imagination, seeing presence where others see absence. As the same document puts it, “If grace is integral to nature, then all nature has in some way the capacity to disclose grace and be a vehicle of it.” This is the great insight at the heart of our faith, a profound understanding of the nature of graced presence: the presence of God in creation, the presence of Christ in those who experience poverty, the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the presence of the Holy Spirit among us today, prompting us from within to love God and to love one another. And presence, for it to become a transforming encounter, needs time and attention.

In the 21st century, one of the acute challenges we face is the ‘theft of time’, what Pope Francis, in one of his wonderful neologisms, calls rapidification. We are seduced by the culture of just-in-time delivery, instant response, the relentless pursuit of economic growth, with time spent just listening to each other considered a waste of time, unless it’s to extract information, or issue instructions. Leaders need time: for stillness, for reflection, for listening, for encounter. I can imagine many of the leaders I know reading that last sentence with a wry smile. Pull the other one, Raymond! I’ve barely got time for a sandwich at my desk, before I fire off a dozen emails and go and take assembly. Then there’s a knock on the door…

Endnotes:

1. Simone Weil, An Anthology (London: Penguin, 2005), p. 232

2. Pope Francis, Homily for Opening of Synodal Path (Rome, 10 October 2021)

3. Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, On the Way to Life (2005)

How do pupils in our Catholic schools/ colleges/universities discover the Truth? In an age when the world order is being shaken to its core and when international and personal conflicts dominate the news, how do students discover who is right and who is wrong, who is telling the truth and who is telling lies? Is there any such thing as the Truth or have our pupils doggedly given up on answering this question? This issue is indelibly linked to students’ poor mental health and has produced according to Haigh (2024) an ‘anxious generation’ creating within them an ‘epidemic of mental illness’. They now inhabit a world saturated by international warfare, violence and killing, serious conflicts, AI, smartphones, social media ‘influencers’, neo-liberalism and rampant market forces. Haigh contends that social media and smartphones are the main culprits and that religion and sport give our young people two substantial ways out of their dilemma. Taking the religious exit, I shall focus in this article on the Trappist twentieth century monk Thomas Merton who offers one very practical way forward. I contend that Catholic educators should place his recommendations at the core of their thinking and practice. The practice is as old as Christianity itself; there really isn’t anything new here.

The Contemplation of the Natural Order and Truth

Merton was always concerned about Truth. In The Ascent to Truth he claims that the contemplation of nature and Truth, what the Greek Fathers and Mothers called theoria physica, is an illuminating recognition of God’s presence and influence in the world: ‘ … He is manifested in the essences (logia) of all things’ (McDonnell, 1989, 384, Ford, 2009). This is not a scientific knowledge of things, but rather an intuitive recognition borne of ‘… a habit of religious awareness’ (1989, 384). It is therefore likely to be enhanced over time, through prayer and contemplation. Indeed, Merton claims that this awareness comes about only by some degree of ‘ascetic detachment’, one of the key ongoing challenges involved in contemplative living. There is also another, illuminating side to this awareness (equally instinctive) which recognises the illusory and falsity of things when they are considered

wrenched from their right ordering and without reference to their Creator. In other words, contemplation allows us to ‘see’ the Truth of things when it is understood as ‘created’ by a benevolent God and at the same time to recognise illusion when this same creation is understood as unconnected to its source and its true purpose.

Contemplation counters the ‘Novelty’ and the Seeking of New Experiences Merton’s Biblical claim is that because ‘there is nothing new under the sun’, (Eccles, 1,9) scores of generations waste their time in endless pursuit of empty things, restlessly wanting new things, what Merton refers to as seeking ‘novelties’ (1989, 380) rather than accepting with appreciation what is given. Time spent on smartphones epitomises this pursuit. Filling time thus becomes an endless search for things which are empty (especially those based on sexual fantasy) and have no real substance – they quickly become non-existent, because they have no real existence in God. The best way to understand the world is to see it in relation to Christ who entered time and consecrated it to Himself and thus saved it from being ‘… an endless circle of frustrations’ (1989, 380). Contemporary men and women, as Merton so vividly describes, exhaust themselves ‘in the pursuit of mirages that ever fade and are renewed as fast as they have faded, drawing him further and further into the wilderness where he must die of thirst (1989, 380). Because of their lack of time given over to contemplation, they feel this alienation deeply. If the very reason for humanity’s existence is contemplation of the Father through Christ in the pursuit of Truth, then when a person finds s/he is unable or unwilling to do this, s/he goes in search of ‘… oblivion in exterior motion or desire’ (my italics, 1989, 382). Merton calls upon Pascal and his notion of divertissements (distractions) to defend his point: ‘We cannot find true happiness unless we deprive ourselves of the ersatz happiness of empty diversion’ (1989, 382). Because we cannot contemplate the world as we ought to, we fill our time with distractions which never ease our pain since these are empty and give no real, lasting comfort. In fact, they increase the pain because they trick us

By Dr David Torevell

into thinking they are real when in fact they are illusory; they tell us a lie which we are duped into believing is the truth. This reminds me of the Buddha’s second Noble Truth of which Merton would have been well aware. The craving for empty things brings about suffering, eventually leading to an experience of a dead-end.

But Merton offers a warning in his last collated publication before he set out on his Asian journey in 1968. He tells us that even if we do remember to contemplate, things can easily go wrong. When contemplation becomes essentially an insistent reflection on the self, it is nothing but narcissism and thus falls easily into idolatry. By simply studying ourselves (influenced perhaps by the many forms of contemporary secular forms of meditation which are now on offer and by the emergence of identity politics), practitioners may find this so ‘delightful’ that they lose interest in ‘… the invisible and unpredictable action of grace’ (2018, 35). Contemplation is not about establishing oneself ‘… in unassailable narcissistic security’ (2018, 9). Rather it is ‘… face to face with the sham and indignity of the false self that seeks to live for itself alone and to enjoy the “consolation of prayer” for its own sake’ (2018, 9). This so-called ‘self’ is pure illusion and he who lives by it will soon find ‘he experiences nothing but disgust or madness’ (1989, 9). Merton draws largely from existentialism and from Pascal. Our digital age, in its own insidious way, may promote this narcissistic and illusory way to the very limit. Since humanity lives with a sense of alienation, insecurity and ‘dread’ due to his/her inevitable, ceaseless self-questioning, the social realm tries to make it bearable when it offers ‘… a multitude of distractions and escapes’ (2018, 9). The banishing of Adam and Eve from the garden resulted in humanity’s disengagement from paradise (Gen, 3, 24). Attempts to assuage this alienation is revealed in those forms of modern addictions (sex, drugs, alcohol) which confront us in the news daily. But the answer is not to seek ‘answers’ by divertissements, but to contemplate the truths given by God in the created order. The way forward is Noverim te, noverim me (may I know you, that I may know myself), as St Augustine taught us (2018, 77). This is what brings a person rest and peace in the social order.

Instead of accepting the Stoics’ answer to painful events - learn to accept them as unflinchingly as you can - we should allow ourselves to ‘… be brought naked and defenceless into the centre of that

dread where we stand alone before God in our nothingness, without explanations, without theories, completely dependent on his providential care’ (2018, 80). Merton is postmodern in the sense that he sees that the modern autonomous self is an illusion and will crack under its own misapprehensions. Modernity’s insistence that individuals can secure a happiness for themselves by their own efforts, desires and motivations, becomes the greatest lie. Consequently, ‘… all our meditation should begin with the realization of our nothingness and helplessness in the presence of God’ (2018, 81). What is required is a disposition of humility, attention to reality, receptivity and pliability (2018, 83). The investigating cognito, which McGilchrist so convincingly exposes as an unbalanced left hemisphere brain activity, is recalled here. Since God is invisibly present to the ground of our being, he remains hidden from the ‘… arrogant grasp of our investigating mind’ (2010, 100). Any such attempts will fail. Merton claims he knows the very reason for our being born :‘… to be loved by him as our Creator and Redeemer, and to love him in return’ (2018, 102). This does not mean separating ourselves off from the material and the natural order, but of seeing its inherent potentiality and limitations so that they do not become idols. This recalls McGilchrist’s exposition of some of the dangers of the Protestant approach to images at the Reformation. Protestant iconoclasts could not see that divinity could find its place between one ‘thing’ (like a statue or stained-glass window) and another (the beholder) rather than ‘… having to reside fixed on the thing itself’ (2018, 316). If any images were allowed in the Reformation, it was because they could offer an explicit message ‘… by reading a kind of key, which demonstrates that the image is thought of simply as an adornment, whose only function is to fix a meaning … which could have been better stated literally’ (2018, 318). This reflected a far more cognitivist and literalist view towards reality than previously held and decried the value of metaphor for communicating thought. It also spurned a distinctively detached and suspicious attitude towards nature itself, which was reinforced by Descartes whose desperation to find certainty resulted in his belief that the only way to secure this was by developing a detached, mentalist and ‘objective’ view of the world. Thus, many became spectators rather than actors in the world, no longer bodily or affectively engaged with nature (McGilchrist, 2010, 332-335).

Hoff’s critique of techno-fascism and the iPhone culture in which we now live, rests on his view that our age is simply an extension of modernity and in particular Newton’s evaluation of the world as a machine. But our modern obsession with mobile phones and AI are particularly dangerous since the latest inventions tap into our senses and take on a quasi-sacramentality of their own. Mobile phones sing to us, we can touch its ‘holy’ screen and it looks suave and sophisticated – and what’s more, we can carry round this indispensable item in our pockets (2018, 254). They are very close to us; they mean a lot to us; they even define our identity. They are like someone’s else’s flesh next to ours - alive, consolatory, helpful, sexy - yet utterly, absolutely. different. Such modern machines (and that is all they are), have replaced our bodily absorption and attuning to the natural world. Merton would claim that they are another divertissement wrenching us away from contemplation and Truth. Persons are somatically cut off from one another in a new way, although such ‘new’ technology (we want the latest design, which is better and quicker and more efficient than the last) claims to make us more in touch with one another. Hoff writes, ‘Poorly designed technologies pollute our gift to be attuned to our never fully penetrable social and natural environment (2018, 252). Wise and prudent persons must never leave the task of finding the meaning and order of the world to software agents (2018, 259). Like McGilchrist’ summation of the contemporary world, Hoff claims that there persists a (post)modern narcissistic illusion to act as ‘… detached spectators, who hide behind a window or a surveillance camera, in order to observe analytically objectifiable “neutral facts” or more elementary “information units” ’ (2018, 267). Notice the present debate about the use of VAR in football and other sports. Video cameras are now consulted to determine the ‘truth’ of what happens in the spontaneous human vitality of a sporting match, one of the most bodily exercises known to humanity, where the ball swerves unreliably between flesh and other opponents’ flesh. The unexpected thrill of the game and human decisions made by the referee are now replaced by the detached watching of a video screen. But this fails since the human intervention of the referee has to interpret what the screen offers him. Machines can never tell the truth – at most they can nudge us in the right direction and even then

we have to be careful. We live in an age of sophisticated machines, which will increase as AI develops. They are on the march and there appears to be no stopping them. Care is required.

Giving Up on Contemplation leading to a Suspicion of the World

The reverse of a contemplative attuning to the natural order - what one might call a suspicious, cynical and even embittered attitude to the worldbecomes apparent in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Once he can no longer trust the social world of which he is a part (the ghost has told him his uncle has killed his father), he becomes victim to and exposes a deeply jaundiced approach to that world. His soliloquy about the flatness of the world beginning with the famous semi-prayerful plea, ‘O God, O God, /How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable / Seems to me all the uses of this world!’ leads him to a more generalised condemnation of the world itself, sometimes expressed in gender terms - ‘Frailty, thy name to woman’. It expresses the belief that the world no longer has any significance or honesty attached to it, that the person he once loved is no longer to be trusted and that there is something ‘rotten’ in the entire state of Denmark’. Ophelia is right to say that ‘a noble mind is here overthrown’. Hamlet has lost his mind, or at least the mind he once had which could envisage the world in spiritual terms as good and created. It eventually leads him to doubt whether it is worth staying around this corrupt world at all– it might be better to not be, than to be. No amount of persuading by his mother to ‘throw to earth / This unprevailing woe’ will deter him from taking this stance towards the world, for she herself is caught up in the very conditions which make Hamlet believe as he does. The highly erotic description of his mother’s relationship with Claudius reflects his belief that lustful sex (‘In the rank sweat of an enseamed bed/Stewed in corruption …’, rather than love now constitutes the way of the world. Is the ghost real asks Hamlet to himself? But he also asks the more dangerous question – is the world ‘real’, ‘true’ ‘trustworthy’ anymore? And the only way he can answer this is by doubting and being suspicious towards any proclaimed substance to the world itself. Like the ghost, the world itself becomes insubstantial - nothing has any real substance anymore and he even wishes that his own ‘sallied flesh would melt/Thaw and resolve itself into a dew’; he wants to become insubstantial himself, just like the world he no longer trusts. He can no longer differentiate

between what is true and what is false, what is empty of meaning and what is full. He wishes to become a mirror image of the no-longer-to-be trusted world. Notice how he can no longer trust even himself anymore – not even to kill a foul murderer. Why not? He has lost confidence in himself and in the world.

Has Hamlet, like his postmodern heirs, decided that there is no longer any Truth to be discovered, or has he simply given up trying to find it in the murky world in which he finds himself? Has Merton’s ascent to Truth become too steep for him and for us? Gregory’s damning but persuasive appraisal of the contemporary world, in part initiated by Reformation thinking, is that we have relinquished the pursuit of truth. We are indoctrinated into the belief that there are no definite answers to life’s questions anymore (2012, 359). But this claim hides a paradoxical characteristic of modern liberalism. From a notion of tolerance, it does not prescribe what citizens should believe anymore, how they should live or what they should care about, but it nevertheless depends for its social cohesion ‘… on the voluntary acceptance of widely shared beliefs, values, and priorities that motivate people’s actions’ (2012, 375). Otherwise liberal states have to become more legalistic and coercive. Any trespass and the full force of the disciplinary law crashes down on trouble-makers.

Contemplative Learning

All of the above has consequences for the way we view learning. Griffiths makes a bold claim about how Christians ought to understand this Christian endeavour. This is at odds with contemporary emphases which makes an idolatry of the intellect. He believes the proper telos of learning has been sabotaged. We live in an age ‘… where the proper telos of learning is not virtue or contemplation, but, rather, material success and the attainment of power’ (my italics, 2011, 106). A Christian approach is to recognise that all knowledge is a route into the goodness of God’s creation. As Griffiths writes, ‘To know and think about anything – a theorem in mathematics … is to know something of what the Lord has made, which is to say that it is to know a good’ (2011, 106) He writes St. Augustine’s distinction between curiosity and studiousness is helpful here. Curiosita is a debased form of learning since it establishes a dominance, a power over that which is to be learned. We try to conquer it, master it and gain control over it - and therefore we abuse it. We enter into a form of prostitution where we have monopoly over a

‘thing’ for ultimately personal gain. One example of this is the nauseous claim that getting a degree (having knowledge) will ensure you get a wellpaid job. It is reductionist in the extreme. In this model, we make idols out of the things we learn. But as Griffiths intelligently and Merton-like points out, the phantasms that the curious attempt to grasp, do not satisfy them (2011, 128). Learning becomes desperate because such learners ‘seek new things to know because they can never be satisfied by the simulacra of knowledge curiosity provides’ (2011, 108). It is a Sysiphus-like nightmare, a walk into the abyss under the guise of gaining new knowledge. Can it even be called the gaining of information? Perhaps that is being too generous towards it. It is no less than an activity of the lust of the eyes claims St. Augustine. But, such a Faustian appetite for knowledge is paradoxically ravenous for its own extinction – it leads to death (2011, 108). The curious hate the unknown because they want to bring it to nothing by coming to know everything by an inappropriate means. But to bring the unknown (incognitum) to nothing by an act of blatant undisguised power, is to return it to the nothing from whence it came before the Lord brought it into being ex nihilo. God’s creation cannot be known in this way, for God’s creation is never mastered by his creatures. We do not have the capacity to know fully the things of God, and to reduce them to nothing, to not having any meaning or significance apart from financial gain, in the name of progress, is a selfcontradiction, but more dangerously, a lie to ourselves as created beings. It is to know ‘no-thing’ at all. Let me repeat, the endeavour is bound to fail, because curiosita, the method they use to gain knowledge of the unknown, guarantees a deathly failure to know. Indeed, all modern talk about methodology ignores the one centrally important core of learning – which is to approach learning studiously, contemplatively. Curiosity by contrast, brings about ‘cognitive devastation’, a shattering of the good, since its approach removes any chance of coming to know the unknowable; they are ‘cognitive killers’ (2011, 109). They murder Truth itself and then insist they are educated.

Studiousness (studiositas) is different and is based upon a desire for cognitive intimacy with and love for the created goods of God. All knowledge should be pursued primarily out of love for the world. And only secondarily for instrumental or functional ends. Only through the former can the secondary

be best determined. Griffiths tells us, ‘The studious do not assess outcomes or undertake their studies with particular expectations. Instead, we attend, lovingly, to what is given’ (2018, 119). Nothing is too small for our attention. Monks and nuns show us the way forward in this. Learning is a prayerful activity assisting to some small degree, access to the knowledge of God. That is why it is undertaken. We come to know God better when we learn. It is therefore a truly lifelong activity, since we can never come to know fully, the God who gave us his created goods to enjoy so that we might understand him a little more (1.Cor. 13,12). Studiousness often includes attentive waiting, sometimes a slow attuning to glimpses of truth which then spur us on to discover more. Delight in learning comes about because we develop an intimate relationship with the creative goods of God; it is never boring, might at times be arduous, but is never mind-sapping and debilitating. Learning about the things of God is actually quite difficult, especially when it comes to learning about ourselves. Since we are finite creatures dependent upon the Creator, we resist any attempts by others to figure us out, to know us. Studiousness also increases the status and importance of learning and tells us why it is vitally important in Christianity. Note how the Jesuits and Benedictines, for example, have a distinctive charism for learning. Monastics regulate their days by their absorption in prayer (contemplation), labour and learning. That is why their architectural features demonstrate a pattern around three interlocking circles - a chapel, a location for work and a library. Learning (or its proper form, lectio divina) cannot be separated from our desire for God.

Tuning into the World Contemplatively Tuning into the Truth might help us to understand better this issue. Jesus was the One who ‘fine-tuned’ his relationship with the Father through prayer. Merton says this is a delicate thing and we can easily be misled. Contemplative prayer if not properly conducted, can encourage the autonomous and calculating ego to be satisfied with and even take delight in its own narcissism ‘seeking to confirm itself in its own selfish existence’ (2018, 109). He then finds himself not alone with God, but with his own self. He will be in the presence of an idol of his own making. This is a false ‘nothingness’ for it rests content in its own finite being, and becomes ‘absorbed’ in its selfconstituted triviality’ (2018, 113). Real contemplation ‘is not a psychological trick, but a theological grace’ (2018,

115). What authentic contemplation does is to make us more attuned to our hope in God, our trust in his voice and our confidence in his mercy. This is not an ideological logic of equivalence‘emptiness equals the presence of God’. No. ‘An emptiness that is deliberately cultivated for the sake of personal ambition, is not empty at all: it is full of itself. It is so full that the light of God cannot get into it anywhere’ (2018, 119). This kind of ‘self-aspiration’ leads to the ‘emptiness of hell’. True contemplation is able to rest in ‘no-thing’ and it finds repose in emptiness but not emptiness for its own sake : ‘Actually, there is no such thing as emptiness, and the merely negative emptiness of false contemplation is a “thing” not a “nothing”. The “thing” that it is is simply the darkness of the self, from which all other beings are deliberately and of setpurpose excluded’ (2018, 120).

Sometimes Merton suggest the spirit of rebellious refusal persists in our heart even when we try to return to him (2018, 122). The ‘dread’ which occurs by being alienated from God and oneself (what better description is there of Hamlet’s state of being than this?) is set in rebellious opposition to the truth of one’s own contingency. If only Hamlet had realised this, then there would not have been so much blood. The realization of our contingent self also prevents us from having to say too harsh things about ourself (Pope Francis, 2018) Everyone fails; it also stops us from what Hamlet declares, ‘Now I am alone’. The experience of “dread’’, “nothingness” and “night” in the hearts of human beings is then the awareness of infidelity to the truth of our life (124). If reflects a deep lying to the self. It is an awareness of infidelity as unrepented and without grace as unrepentable (2018, 124). Merton claims that a feeling of nothingness will not be relieved ex opera operato by the reception of the sacraments. These will not suffice since s/he continues to cling to the empty illusion of a separate self, inclined to resist God. Nor will it ally his sense of nothingness which he will feel when left to him/herself without divertissement. He is even hard on ‘the best of men’ since they see ‘their stubborn attachment to the lie in themselves … their fear of truth and the risks it demands’ (2018, 125). Even if s/he is able to recognise the dread which comes about without recourse to God, at the same time s/he loses his conviction that God is or can be a refuge for him. His meditation then becomes nothing more than an agonia, a wrestling with nothingness and doubt.

St John of the Cross is Merton’s confidante and it should be Catholic educators’ too. When things appear dark and sinister in the world and when our prayer is arid and dry, like dried wood without kindle, then be glad for ‘when God takes your hand and guides you in the darkness, as though you were blind, to an end and by a way which you know not nor could ever hope to travel with the aid of your own eyes and feet, howsoever good you may be as a walker’ (St John of the Cross quoted in Merton 2018, 145).

What I have attempted to show in this article is that we can often become duped into thinking we inhabit a ‘real’ world, which through contemplation we learn is nothing more than a figment of our distracted selves. Pascal’s divertissements blur the boundaries between truth and falsehood and make the world opaque, sometimes insubstantial, often not to be trusted. This can lead to a kind of death in spiritual terms – the annihilation of Truth through the obliteration of the natural order as created. Merton and others like him, remind us of this. I believe it is wise for an ‘anxious generation’ to listen carefully to what they say.

References

Ford, M. 2009. Spiritual Masters for All Seasons.

Gregory, B. 2012. The Unintended Reformation.: How a Religious Revolution Secularised Society.

Griffiths, P. 2011. ‘From Curiosity to Studiousness-: Catechising the Appetite for learning’ in Smith, D & Smith, J. Teaching and Christian Practices. Reshaping Faith and Learning.

Haidt, J. 2024. The Anxious Generation. How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness.

Hoff, J. 2018. ‘The Eclipse of Sacramental Realism in the Age of Re-Form: Rethinking Luther’s Gutenberg Galaxy in a Post-Digital Age’, New Blackfriars. 99. 1080. 248-270.

McDonnell, T. 1989. A Thomas Meton Reader. McGilchrist, I. 2010. The Master and his Emissary. The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World.

Merton, T. 2018. Where Prayer Flourishes. Pope Francis, 2018. Gaudete et Exsultate. Apostolic Exhortation on the Call to Holiness in today’s World.

David’s co-written book with Brandon Schneeberger and Luke Taylor SJ Exploring Catholic Faith in Shakesperean Drama. Towards a Philosophy of Education was published by Routledge in April, 2025.

Introduction

The 2016 GCSE curriculum reforms led to a tsunami of change in all areas of the KS4 curriculum. These changes were so profound that McGrail & Towey (2019) conducted an impact study in eighteen schools across various Dioceses in England and Wales. The study, entitled Partners in Progress? An Impact Study of the 2016 RE Reforms in England, sought to understand the views of teachers and leaders of RE in the Catholic sector. Using a qualitative methodology, gathering data through in-depth semistructured interviews, the study showed that whilst the changes were positively greeted by many, there was a high degree of dissatisfaction among practitioners who viewed the content as inappropriate for many GCSE students. It was believed to be inaccessible and irrelevant to their lives or stage of development in their faith journey. Although the study conducted student focus groups, the findings did not include this data. Thus, there is a need to understand how students experience the reformed KS4 RE curriculum.

Is the Reformed Curriculum Accessible and Relevant?

As a practitioner of RE for twenty-eight years, I find the 2016 curriculum problematic. I agree with McGrail & Towey (2019) that areas of the reformed content lack relevance to the lives of many students. Having delivered the GCSE in three schools, each with different socio-economic contexts, I have experienced similar student reactions: ‘Why do we have to learn this?’ and ‘This is boring!’ Many practitioners I have worked with, and others through professional networks, voice similar concerns. One colleague commented that the curriculum, even within an approved examination board, lacks relevance and is ‘out of touch with the reality’ of students.

McGrail & Towey (2019, p.283) found dissatisfaction among teachers who felt the curriculum ‘would be too difficult for pupils’ due to its overly academic theological content. A significant cause of dissatisfaction was also the level, quantity, accessibility, and language of the content (p.288). These are strong criticisms. If educated professionals with a vocation to teach RE express such concerns, it raises the question: what are the students' opinions?

This question has prompted me to undertake an EdD to explore how GCSE RE students experience the curriculum, which equates

to 10% of their curriculum time. In a synodal Church that values listening and discerning, it is timely to understand student experiences of the RE curriculum, considered not only a core subject but the "core of the core curriculum" (St. Pope John Paul II, 1992, p.2).

In this article, I explain why, in the spirit of synodality, it is important to explore how Roman Catholic GCSE RE students experience the curriculum.

Why My Study? A Tsunami of Change! 2016 marked a massive shift in England and Wales's GCSE curriculum, described as a "headlong rush to reform GCSEs [leading to] widespread confusion" (Bousted, 2017, p.1). This was not the view of Michael Gove, who based the changes on Michael Young's (2014) theory of powerful knowledge. Gericke (2018, p.428) argues that for Young, "Powerful knowledge is coherent, conceptual, disciplinary knowledge that, when learned, will empower students to make decisions and become actioncompetent."

For Young (2014), powerful knowledge transcends common knowledge and leads individuals from what they know to what they do not yet know. It exists outside students' immediate experiences, providing access to new worlds. In RE, for example, knowledge of the Magisterium would be considered powerful knowledge.

Is Powerful Knowledge a Problem? The simple answer is ‘No’—a curriculum should present new knowledge specific to each discipline. In English, studying A Christmas Carol and Macbeth moves students into new yet relevant worlds: concepts like greed, poverty, illness, and loneliness remain within their thematic universe.

In RE, Moffat (2021, p.249) argues that powerful knowledge can offer "deep learning," stating that the RE specification provides academic rigour appropriate to students’ age, offering a lifelong love of theology. Yet, one must ask: is the RE GCSE knowledge different from English in terms of student comprehension? Is the RE curriculum relevant to students' lives?

These questions drive my desire to explore student experiences. When asking students who consider RE boring whether they find

By Rev Dcn Michael Bennett

Dcn Mike Bennett is the Director of Catholic Life at All Saints RC High School Kirkby Liverpool. Having served in six Catholic Schools in the Archdiocese of Liverpool for over twenty-fiveyears as teacher of RE, Head of RE and Assistant & Deputy Headteacher. Mike is currently leading on Catholic Life and formation. Mike is in the final stage of a Doctorate at Liverpool Hope University researching students' experiences of GCSE RE Specification A.

other subjects more interesting, many suggest English feels more relevant. Why? Bellet (2006) applies a theory from Paulo Freire (1970), a Brazilian educator and philosopher who developed critical pedagogy.

Freire’s thematic universe theory argues that knowledge disconnected from the learner’s reality is hard to grasp. In adult literacy, he refused to use standard government texts, instead using materials rooted in students' environments. In terms of RE, Bellet (2006) suggests that knowledge must exist within the student's thematic universe—the world of ideas they inhabit.

Thus, while A Christmas Carol resonates with students, can the same be said for studying the Four Marks of the Church? I do not yet know, but I aim to explore this.

Some students view the post-2016 RE curriculum as irrelevant. Is it because much of the knowledge lies outside their thematic universe? I cannot yet answer this; however, students' voices must be listened to.

Synodality

We are called to be a synodal Church, valuing listening. Pope Francis (2021) teaches that the Church is on a constant journey, and at its heart is the synodal process—a "learning process, in the course of which the Church comes to know herself better" (p.5).

We must engage with students of RE: if they express dissatisfaction with the curriculum, we must discern its meaning; if they find it engaging, we must celebrate that.

In my experience, students more positively embrace philosophy content— particularly moral philosophy or Christian ethics. Debates around human sexuality, reproduction, and gender discrimination seem to engage students more fully. Is this because these topics lie within their thematic universe and offer concrete points of reference for anchoring new knowledge?

In contrast, theological and scriptural content appears less relevant to many students, possibly because it does not exist within their thematic universe. A Religious Education curriculum must offer engagement with the Church's traditions and wisdom. Yet, is the current weighting toward Theology and Scripture too heavy? Should there be greater balance with Philosophy and

Ethics? These are questions I will explore during my research.

Over nearly thirty years, I have seen a change in students' attitudes since the 2016 reforms. Many students question why they must learn about topics like the Four Marks of the Church, the Magisterium, and Popular Piety. Many colleagues also struggle to make these accessible to fifteen-year-olds.

Chater (2015), Gericke (2018), and Deng (2015) argue that a highly academic theological curriculum that exists outside students' immediate experiences will lead to frustration. Chater (2015, p.5) particularly suggests that a content-laden curriculum tends to "induce boredom, apathy or hostility amongst students and teachers!" I have experienced this many times since 2016.

Thus, it is apt to build on McGrail and Towey’s (2019) work. Their study considered the impact on those who deliver the curriculum; now, it is time to assess its impact on those who receive it.

Methodology

My research focuses on subjective human experience: how students experience the curriculum they receive, and how teachers experience delivering it. I aim to assess differences between what is taught, what students would like to learn, and what teachers would like to deliver.

Using a qualitative methodology, I will gather data through in-depth, semistructured interviews with RE students and teachers. This approach will allow me to fully understand participants' experiences. I will analyse the data using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), which seeks to understand the complexity of human experience.

Conclusion

McGrail and Towey’s (2019) impact study was a timely and significant piece of research. It provided RE teachers and leaders in Catholic schools an opportunity to discuss their experiences of the reformed GCSE curriculum, highlighting both satisfaction and dissatisfaction. A key anxiety was the suitability of the content and its potential to disengage students due to lack of relevance and accessibility.

Although students’ views were gathered during McGrail and Towey's study, they were not published. Nine years on, it is time to engage with students directly, in a spirit of synodality, to understand their experience of GCSE Religious Education.

References

Bellett, E. (2006) Religious Education for Liberation: A Perspective from Paulo Freire. British Journal of Religious Education, 20(3), pp. 133-143.

Bousted, M. (2017) The consequences of Gove’s ideological reforms are now being felt everywhere’. Times Education Supplement.

Chater, M. (2013) Doing the Knowledge: or, I had that Mr Gove in my curriculum once.

Chater, M. (2020) Reforming RE: Power and Knowledge in a worldviews curriculum. John Catt Publications.

Deng, Z. (2015) Content, Joseph Schwab and German Didaktik. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(6), pp. 733-786.

Dillen, A. (2011) Empowering Children in Religious Education: Rethinking Power Dynamics. Journal of Religious Education, 59(3), p 4-16.

Franck, O. (2021) Gateways to accessing Powerful Knowledge: a critical constructive analysis. Journal of Religious Education, 69(6), pp. 161-174.

Franck, O. (2023) Powerful Knowledge in Religious Education: Exploring Paths to a Knowledge-Based Education in Religions. Palmgrove Macmillan.

Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin.

Freire, P. (2005) Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to those who dare to Teach. Routledge.

Gericke, N. (2018) ‘Powerful knowledge, transformations and the need for empirical studies across school subjects’. London Review of Education, 16(3), pp. 428–444.

Lundie, D. (2009) ‘Does RE work?’ An analysis of the aims, practices and models of effectiveness of religious education in the UK. British Journal of Religious Education, 32(2), pp. 163 -170.

McGrail, P, Towey, A. (2019) Partners in Progress? An impact study of the 2016 Religious Education reforms in England. International Journal of Christianity and Education, 26(3), pp.278-298.

Moffatt, J. (2021) Religious Education as a Discipline in the Knowledge Rich Curriculum. Irish and British Reflections on Catholic Education, Springer pp. 249-260.

Pope Francis (2021), Pope calls for humble and synodal Church, led by the Holy Spirit, Vatican News Service.

Pope John Paul II (1992), ADDRESS OF HIS HOLINESS JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS OF GREAT BRITAIN ON THEIR AD LIMINA VISIT.

After nearly two decades of headship in Catholic education, I work as a consultant. My main areas of interest are school leadership and how appraisals are conducted, especially the appraisal of heads and the CEOs of MATs. This includes how NC assessments, OFSTED inspections and other measures of school performance impact on appraisal outcomes. I’m increasingly aware of the importance of fairness, empathy and understanding in appraisal conversations, including whether the professed ethos or charism of a church school is always being reflected in the experience of the person being appraised. At all levels, appraisal should be treated as a significant process with conversations that are constructive and targets that are both challenging and motivating. In some cases, however, they are treated as a cursory administrative necessity. Managed poorly, they can be a deflating experience for the appraisee. My interactions with trustees, governors, CEOs and heads have given me insights into the strengths and limitations of different appraisal models.

The core purpose of appraisal is to review performance based on the outcomes of agreed targets and to agree on objectives for the following cycle. Most panels and line managers recognise, however, that outcomes are unlikely to reflect the entirety of the appraisee’s performance and will take a holistic view of the quality of their leadership. Targets for school leaders may range from being remedial, such as strategies to address concerns raised by an inspection, to groundbreaking, perhaps spearheading a major curriculum or pastoral innovation. They can be detailed or broad brush. In a church school at least one will focus on its Christian life. Whatever way they are framed they should prioritise rather than add to leaders’ workload and their challenge should be manageable. A target which has a focus on, and strategies for, improving teaching and learning is essential, but its desired outcome should avoid pinning success on a specific percentage or numerically based outcome. Although appraisal objectives for heads are termed as ‘governors’ targets’, in my experience

panels generally trust competent leaders to draft their key priorities for the following cycle. Where relationships are good and communications are regular, these will likely be accepted as an appropriate starting point. However, before any formal agreement on targets, modifications suggested by panel members are a positive indicator of mutual respect and shared empowerment.

An effective relationship between the external consultant and an appraisal panel is based on respect for each institution’s preferences and policies for the format for the review. Consultants can propose modifications which panels often welcome, but appraisal processes should be challenged only when they are clearly problematic. Alongside their experience and expertise, consultants bring their own distinctive approach to undertaking the role. It is best for this to be shared with governors or trustees before being appointed. I follow the ‘appreciative enquiry’ model, a robust and constructive evaluation process promoted by the National College for School Leadership. I’ve also learnt much from effective appraisal strategies used by the outstanding educationalists I’ve observed in my work for the NCSL’s International Unit. Longitudinal research by Nottingham University’s Professor Chris Day into effective leadership has shown how heads who lead the same school successfully over several years provide a desirable blend of continuity and openness to change. Consultants who work with leaders and governors over longer periods develop a richer understanding of a school’s story, its challenges, and the aspirations it has for itself. Coupled with the rigour essential for avoiding a ‘comfort zone’, this empathy and trust allow for better informed and more searching professional conversations.

Although there will always be some heads who lack the skills and personal qualities needed to do the job, most leaders are committed to ensuring the wellbeing of their pupils and staff and to improving outcomes, so enabling their schools

By Anthony McNamara

to flourish. Conversations between leaders and consultants in the run up to appraisal provide valuable opportunities to discuss pedagogy, analyse data, reflect on performance and relationships, and explore possibilities for the future. Many schools hold termly or midacademic year appraisal meetings so progress against targets can be monitored on an interim basis. The annual appraisal meeting itself, however, is the most significant arena not only for trustees and governors to review and assess the school leader’s performance in a summative way but also, just as importantly, to record their support and appreciation for the person in whom they have entrusted the leadership of their MAT or school. While recording panel members’ comments on progress against targets, I ask each of them to say what they most appreciate about their head or CEO. The praise is invariably heartfelt, as is concern for the leader’s wellbeing. Many consultants ensure that these comments, perhaps anonymised, are captured in the final document. Seeing an appraisee’s face glow when they listen to how much a panel values their hard work and commitment is a lovely moment.

Working over several years with primaries, secondaries and MATs in both the state and church sectors in different parts of the country, I’ve seen how the appraisal process is enriched by the quality of panel members. On rare and dismal occasions, because of insensitive or even unprofessional behaviour, I have had to intervene. I needed to prompt one chair of governors to thank a head who had met all her targets and was held in high regard by her colleagues. A more disturbing experience was having to challenge a CEO who, in front of an appraisal panel, made unjustifiable and deprecating comments about a committed and effective head. In some larger MATs, there are notorious cases of a setback such as a drop in KS4 results being used as a cudgel. The appraisee is left with their confidence shattered and a resignation that may be a loss to the profession. These poorly or badly managed appraisals are wasted opportunities for what could have been transformational professional exchanges.

Where concerns and challenges have arisen over the year, appraisal conversations and reflections that are handled with sensitivity can be catalysts for improvement. I have been inspired

by the deep emotional intelligence shown by some chairs and CEOs in years when pupil outcomes have been disappointing. When I used this adjective in my preliminary notes to the CEO of a high achieving MAT in reference to results in one of his schools, he challenged me. He felt it carried unhelpful freight and risked being internalised by the head concerned as personal failure. I listened as he reflected truthfully to the head how the year had gone. He did not excuse or gloss over anything but throughout the conversation what I heard was his understanding of context, and his confidence in and respect and affection for his colleague. The head told me how reassured and motivated he felt afterwards. The warmth and drive for excellence that characterise that MAT have transformed the life chances of children in the deprived area it serves, and its success has deservedly attracted national attention.

The effectiveness of school leaders is rightly measured against national terms of reference and so their appraisal should give significant weight to pupil progress and attainment and inspection judgments. Context matters as well: results and attendance can be affected by difficulties in recruitment, poor quality supply staff, long-term staff sickness, and persistent absenteeism among pupils who are unreachable. Widespread concerns over the validity of inspection judgments and the behaviour of some inspectors have prompted a government review. At a conference on school improvement in Brazil I saw for myself how the heavy-handedness of the OFSTED model of quality assurance is why it continues to be an unattractive international outlier. A speech by HM inspector of Schools appalled many of the delegates and differed starkly from the supportive vision offered by Canadian and Australian speakers. Conversations that followed raised two questions: ‘How do we measure, assess, inspect and appraise intelligently?’ and ‘How do we employ emotional intelligence effectively in appraising and supporting our teachers and school leaders?’.

Appraisal objectives, when achieved, provide evidence of their positive impact. But whatever the capacity in which we work in schools, our daily interactions, professional behaviour and priorities are being appraised all the time, and most importantly by our

pupils. In the context of a 2022 PISA survey which showed that our young people have the second lowest life satisfaction in developed countries, and another which ranked them among the highest for ‘not feeling they belonged’, one objective set for all of us who work in Catholic education overrides all others. It is ongoing and challenging and is why many of us see our work as a vocation. Our pupils may not be aware we are trying to achieve it, but in these darkest of times, and especially for those who are most vulnerable and disadvantaged, it will shape their future lives. It was best described in the Vatican Council document, ‘Gaudium et Spes’. It called on school leaders and teachers ‘to be especially aware of how much depends on them in the present state of the world. Their task is not simply to impart knowledge but to give future generations reasons for living and hoping’.

This is a huge and daunting expectation on us. In most cases it will be met in small shifts in awareness and behaviour which have a cumulative impact. Here is an example from my own experience. One year we trialled an anonymous survey with the classes we each taught which included the sentence, ‘My teacher likes me’. I was upset to see that among the thumbs up and don’t knows, one pupil had ringed ‘no’. From the handwriting I eventually worked out who the child was. To my shame I realised that he wasn’t imagining it, I probably didn’t like him and what worse, he knew it. That appraisal of me, a circled ‘no’, by a child who was struggling with his learning jolted me into developing a greater awareness of my own behaviour. It motivated me to improve my practice more than any panel scrutinising my performance. It made me reflect as well on the damaging impact two teachers had had on my self-worth when I was a schoolboy and how a line-manager who never hid his dislike for me at the start of my teaching career undermined my confidence. In whatever capacity we interact with others, the emotional intelligence that we acquire through learning empathy and self-awareness will be a key driver to improving performance. More importantly, it will do its bit to make Amos’ and Micah’s call to ‘act justly and love tenderly’ a reality. As the saying goes: ‘We might forget what was said to us, but we’ll never forget how we were made to feel’.

The perception that faith and science are at odds remains stubbornly prevalent in some circles. The prominence in the early 2000s of New Atheists, such as Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens, strongly contributed to this misconception.

Historical awareness can be limited. The likes of James Clerk Maxwell, Johannes Kepler, and Georges Lemaître, the Belgian priest who proposed the “Big Bang” theory, are among many who felt that theism was not at odds with the pursuit of scientific knowledge. For Lemaître, his faith engendered the awe that inspired his research. Nevertheless, more recent debates — in the West, at least — have all but eclipsed this multilayered history.

It is in this sometimes fraught context that the UK-based “God and the Big Bang” education programme came to be. In 2010, the Anglican diocese of Manchester submitted a motion to the General Synod, affirming that science and faith were compatible. The motion passed with little opposition.

Two years later, the Director of Education for Manchester diocese, Maurice Smith, and the Anglican Bishop of Middleton commissioned social entrepreneur , Michael Harvey, to begin a project that would demonstrate this compatibility. Despite having no science background himself, Mr Harvey was undaunted.

“I found a head teacher in Kent who, with a couple of scientists, arranged events for sixthform students called ‘God and the Big Bang’. I thought it was something quite replicable, asked for permission to use the name, and brought it back to the diocese of Manchester. From those beginnings, more than a decade ago, God and the Big Bang (www.GATBB. co.uk) has become a nationwide project, involving dozens of scientists of deep Christian faith, many of whom are Catholics who have spoken to tens of thousands of primary and secondary school students as well as sixth form students since its inception. In 2023 alone, the team visited more than 100 schools, and interacted with more than 6500 nine- to 18-year-olds. Around 15% of schools who host the workshop are Catholic schools and the GATBB Team are eager to be invited by more. In recent weeks both the newsletters of ATCRE [Association of Teachers in Catholic Religious Education] and CISC [Catholic Independent Schools Conference] have generously advertised the workshop. David Bayne,

Communications lead for ATCRE and a retired Head of Sixth Form in Hexham and Newcastle diocese experienced the workshop himself with his own students and highly recommends it.

THE team offers schools a series of formats, depending on age. “Awesome Science” sessions, for five- to seven-year-olds, last between one and two hours; workshops for eight- to 11-year-olds can be offered as either a half or whole day; for 11- to 18-year-olds, workshops are offered over a whole day, divided into various interactive segments.

Workshops are designed to be flexible, to work around a school and its needs. Pupils are surveyed at the start, to help the team to adapt accordingly. Classes may reflect on meaty subjects such as evolution, ethics, science in action, whether medical treatment is a human right, or how to decide what the NHS offers patients. Another questionnaire is distributed at the end of the day to see what impact the experience has had.

Mr Harvey believes that the programme is redressing some important historical imbalances in the ways in which both science and faith have been approached in British education. He feels, as do many in Christian schools that “scientism” has crept in to all areas of education. ‘This is what science has found, and it will basically solve all the problems,’ he says , ‘ very rarely do we teach science as “This is what we don’t know.”

“Often, there’s a sense from schools that parents are either worried we’re coming in with a very evangelistic agenda - which we don’t - or that we’re going to tell them that they must believe in evolution and the Big Bang” explains Abi Falkus Lead Coordinator.

As well as the in-person workshop in school, “God and the Big Bang” is accompanied by online resources — many of them free and suitable for audiences of diverse ages, disciplines, and beliefs. A highlight is the video Sparks Resources — which accompanies purchases of Sparks discussion cards — where the team discuss weighty matters such as “God and Creation”, “Truth and Proof”, “Time and Space”, and “Mystery and Wonder”.

“Questions are at the heart of both science and religion,” a biology and physics researcher, Gavin Merrifield, another member of the team, says. “If we stop asking questions, I think then we have a problem.”

I recently attended a full drop down day workshop at St. Thomas the Apostle Academy in the Archdiocese of Southwark for the whole of Year 11. [Yes Year 11 in their GCSE year!] I was very impressed by the way the team enabled the students to really engage with the process and explore the interconnectedness of faith and reason/ science and religion. Rob Green, Head of RE said;

“Students at St Thomas the Apostle are very STEM orientated but a large majority do have a strong faith as well. Finding activities that incorporate the two can sometimes be quite difficult especially in a formal setting. However, GATBB incorporate these two aspects of life really well. I think the students responded well to how professional and interesting the speakers were. The team had a great passion for their chosen specialities, and I think this kept the students engaged throughout the day. Staff members were equally as impressed in the Q&A as the team seemed to tackle the questions fantastically.” As an observer on the day, I can fully attest to this highly positive impact. The GATBB team recently carried out some research in to the impact of their work in a Catholic secondary school and the key findings were that students with religious commitment (especially Muslims & some Catholic and other Christians) defended faith, while atheist/ agnostic students unsurprisingly leaned towards science. KS3 students were more uncertain, while students in KS4/5 had nuanced views. Many believed faith and science could coexist once they had experienced the workshop strongly agreeing with the statement: "Science explains the physical world, faith explains meaning."

How does GATBB scout for talent?

“The key word is scouting”, Mr Harvey says. “We’re blessed if people come to us. In the meantime, we actively seek out highly committed Christian undergraduates and post-graduate scientists as it’s important that our facilitators are relatively close to secondary students in age.”

GATBB is thus about far more than shattering the dichotomy of faith v. science. It is about equipping young people with important skills, such as discernment and critical analysis, useful for academia and beyond. Students are learning to apply knowledge constructively, to engage in, and with, the wider world better. This is all the more vital in a “post-truth society” where it seems to be completely unacceptable to tell somebody that they’re wrong, even if what they believe to be true is based on misinformation. After more than a dozen years of being in schools the fruits are beginning to show. Michael tells me this is exemplified by a recent encounter. “There was a young man, who was in his first term at Oxford, studying biology. A senior scholar said to him: ‘You’re a Christian doing biology? Then you won’t be a Christian after the first year.’ The young man said it shocked him a bit. However, he remembered, just a few months before, a group of GATBB scientists came to his school showing that science and faith were compatible.’” These are the kind of bright young minds that Michael hopes to bring on board in future. “We’re going from recruiting 10 to 30 science communicators in one year. We’ll have to find, train, and deploy them, and that’s going to really test us.”

In 2021 GATBB was a awarded a three year grant of £707,000 from the John

Templeton Foundation which is testimony to as well faith in the unique educational contribution the project is making and why Catholic schools would do well to engage with GATBB as much as possible.

The aim is to help students explore how faith and religion together helps us ask better questions in harmony with scientific knowledge and discovery through the lens of Christian spirituality and biblical faith. Many children, don't always appreciate just how much the Church has been an advocate for scientific discovery throughout history and just how many amazing scientists were men and women of profound Christian faith.

The workshop aids the mission, identity and evangelisation role of the school by raising awareness of just how proscience the Church is and has been as well as alerting young people to the risk of scientism. [placing an excessive belief in the power of scientific knowledge and techniques]

Students are challenged to think critically as they approach questions from both a scientific and faith perspective. The content is carefully tailored to the age and ability of the pupils taking part.

Scan Here

For a brief video providing some information on the GATBB project

Or visit: gatbb.co.uk

If you would like to know more and book a workshop for your school please contact Abi Falkus on abi@gatbb.co.uk

As we reflect on the season of Lent that has just passed, Common Good Schools Project Leader, Jo Stow, encourages schools to take a more relational approach to charity and to notice hidden poverty in the classroom.

Last week, I joined a friend who is a teacher at an after-school club. The children gathered, enjoyed snacks, and then went off to participate in the session’s activities. After snack time, I noticed that one boy, Michael (not his real name), hung back from the activities and was eating what was left over of the snacks. Michael is eleven. His teacher added quietly, “He comes for the free food.”

The season of Lent was a busy one in church schools. Charities were supported. Wonderfully creative, sponsored events took place. Children and staff worked hard to “give alms to the poor.” Donations were made to local food banks. Many fasted – a spiritual discipline that points us to God by reminding us how it feels to be hungry,

At an education conference I recently attended, data was shared about child poverty globally. A teacher spoke up. He said, “Students at my school are part of that statistic.” I went to chat with him over lunch. He spoke about the stigma of poverty in schools. “These children become invisible because of the shame they feel. Somehow, they feel that poverty must be their own fault.” I was struck that stigma is still an issue after decades of campaigning on child poverty. These children are effectively hidden in plain sight. We have the data, but part of the story is missing.

Now that Lent has ended, it is worth reflecting on where the poor people we have supported are located—where they live: nearby, in another district, or perhaps overseas.

Lately, I’ve been doing some research among primary school teachers. It became

engage with issues of global poverty, but there is a considerable lack when it comes to the local. Given this, what could we be missing? Perhaps our approach needs to pay closer attention to context. And when we support a local charity, we should be aware that some of those in need may be under our own roof.

Them

Let’s consider the full meaning of almsgiving. Traditionally, giving alms has been described as “a witness to fraternal charity”[3], indicating that it is about more than giving money or services. Christian love particularly involves the gift of time and personal connection. This is how the bonds of fraternity are formed.

Pope Francis repeatedly called for a culture of encounter and warns against charity becoming a means of keeping poor people at arm’s length.[4]

In a busy school, “almsgiving” can sometimes become reductive and conflated with fundraising. What might this feel like for Michael? His ability to contribute is compromised, and his family’s situation can become a source of shame. He is faced with the confusion of being invisible in his own classroom.

If we fail to embrace the true spirit of almsgiving, we can inadvertently fall into a “them and us” dynamic. If we do not recognise who is under our roof, we create a false division between those who can afford to give and those who can’t, and we risk removing the agency of someone who is poor.

In its welfarist, reductive form, where charity is understood as volunteers doing charity for poor people (whether through fundraising or by delivering a service), the possibilities of true encounter are small. The transactional dynamic between active giver and passive recipient does not build fraternity, one of the signs of Christian love.

If our almsgiving is focused on our local area, this opens up opportunities to go beyond the welfarist approach. A mark of the common good

is reciprocity. This requires true relationship, where there is give and take, and the dignity of the person is upheld. Simply giving money to the poor may help temporarily, but it does not uphold a person’s dignity – it is as if he or she has nothing to contribute.

Earlier this week, a colleague shared with me some children’s responses to the question “Do you think God cares about poverty?” Most assumed that God does care, and that kindness is the right response. But rather a lot of them took the view that poverty is a matter of fate or the result of poor choices. There was little awareness of the injustice of an economic model that relies on low-wage, insecure jobs.

The Christian vision of justice derives from the Jewish tradition of right relationship, in which the response to poverty must be relational. We do not stand in solidarity with the poor by giving a handout and walking away.

The principle of Solidarity sees human beings as social beings designed to be interconnected by relationships of mutual concern and support. It is a determination to work for the good of all and of each person – so that in some way, all are responsible for all.

This means going through something with someone, giving time and building a relationship, helping them to get back on their feet. The Good Samaritan not only helped the man by the road and paid for his care; he came back the next day. A relationship was formed.

Charity that is truly Christian is not a one-way street: the giver must be open to receive, and the receiver must be able to give. This ensures a mutuality that goes beyond transaction. Everyone has something to contribute.

In Catholic Social Teaching, Solidarity is always to be balanced with the principle of Subsidiarity. Subsidiarity holds that responsibility is taken at the most appropriate level and that decisions should always be taken closest to those they affect – and that a central authority should only do tasks

that cannot be performed at a more local level. In this way, everyone fulfils their unique roles, and the integrity and agency of each person are upheld.

If Not Donations, What Might This Look Like?

We often ask our partner schools, “How can you make what you are already doing more common good?” Small tweaks are where to begin. For example, fundraising should always be accompanied by something relational and reciprocal. Whatever your Lent action was, it should have built relationships.

If you are open to a radical new way of almsgiving, consider these suggestions:

• A shared meal hosted by a local partner with a good kitchen, served by school children (both those on FSMs and those who are not), involving parents and staff, and where members of the community are invited too. Costs could be supported by a pay-asyou-feel or pay-it-forward model.

• A listening project where children research what sorts of foods are available locally – identifying whether fresh, healthy food (fruit, veg, meat, and fish) is priced too high, and finding out about the range of local suppliers, including supermarkets, community food sources, co-ops, allotments, and local farming produce.

What About Michael?

Michael, the boy who stayed for the leftover snacks, is not just hungry - he is isolated. For him, school charity initiatives were confusing and embarrassing. Beyond FSM statistics, Michael deserves solidarity, friendship, accompaniment and the opportunity to contribute..

Now that Lent is over, how can we ensure that our charity work builds relationships, respects dignity, and fosters reciprocity?

In an era where the social landscape is increasingly secular and pluralistic, Catholic independent schools face a unique set of challenges. These schools are tasked with remaining true to their religious identity while simultaneously providing a contemporary, high-quality education that resonates with the broader society. At Beaulieu Convent School in Jersey, which I have the privilege of serving as Head, and in my role as Chair of the Catholic Independent Schools Conference, I have been fortunate to witness first-hand how Catholic schools navigate these tensions while continuing to serve the needs of our diverse communities.