Medical Instrumentation Application and Design 4th Edition Webster Solutions Manual

number of cases; the only authority of weight who opposes this view is Charcot, and his opposition is abundantly neutralized by a number of carefully-studied American and European cases.

145 The coincidences among these three cases were remarkable. All three were Germans, all three musicians, two had lost an only son. In all, the emotional manifestations were pronounced from the initial to the advanced period of the disease.

146 A Bohemian cigar-maker was startled by the sudden firing of a pistol-shot in a dark hallway, and on arriving at the factory, and not fully recovered from the first fright, he was again startled by the sudden descent of an elevator and the fall of a heavy case from it close to where he stood. From the latter moment he trembled, and his tremor continued increasing till the last stage of his illness was reached. This was my shortest duration, four years, and of nuclear oblongata paralysis type.

Hysterical and other obscure neuroses have been claimed to act as predisposing causes. But, inasmuch as it is well established that sclerosis is not a legitimate sequel of even the most aggravated forms of true hysteria,147 and, on the other hand, that disseminated sclerosis, particularly in the early stages, may progress under the mask of spinal irritative or other neuroses, it is reasonable to suppose that cause and effect have been confounded by those who advanced this view. According to Charcot, the female sex shows a greater disposition to the disease than the male. Erb, who bases his remarks on the surprisingly small number of nine cases, is inclined to account for Charcot's statement on the ground that it was at a hospital for females that Charcot made his observations. On comparing the figures of numerous observers, it will be found that in the experience of one the females, and of the other the males, preponderate. In my own experience the males far exceed the females both in private and in dispensary practice. Of 22 cases with accessible records, only 7 were females.

147 Charcot's observation of lateral sclerosis in hysterical contracture, although made so long ago, has not been confirmed, and the most careful examinations in equally severe and protracted cases have proven altogether negative.

Syphilis has also been assigned as a cause. The connection is not as clear as in tabes. In the few cases where there appears to be a direct causal relation the lesion is not typical. There are sclerotic foci, but in addition there is a general lesion, particularly of the posterior columns of the cord, such as is found with paretic dementia. And it has been noted that periendymal and subendymal sclerosis is more frequent with the cases of alleged syphilitic origin than with those of the typical form.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS.—In view of what has been already stated regarding the numerous clinical types found in disseminated sclerosis, it is easily understood why the diagnosis of this disease is becoming more and more uncertain: every new set of researches removes some one or several of the old and cherished landmarks; and it may be safely asserted that only a minority of the cases show that symptom-group which was formerly claimed as characteristic of all. The discovery of a series of cases by Westphal,148 in which the typical symptom-group of Charcot was present, but no sclerosis deserving the name found after death, as well as the interesting experience of Seguin, who found well-marked disseminated sclerosis in a case regarded as hysterical intra vitam, illustrates the increasing uncertainly of our advancing knowledge. It was believed within a few years that the presence of cranial nerve-symptoms was a positive factor in determining a given case to be one of disseminated sclerosis, but in the very cases described by Westphal such symptoms were present notwithstanding the lesion was absent. Up to this time, however, no case has been discovered in which, optic-nerve atrophy being present in addition to the so-called characteristic symptoms of intention tremor, nystagmus, and scanning in speech, disseminated foci of sclerosis were not found at the autopsy. This sign may be therefore regarded as of the highest determining value when present; but as it is absent in the majority of cases, its absence cannot be regarded as decisive. The presence of pupillary symptoms also increases the certainty of the diagnosis when added to the ordinary and general symptoms of the disorder related above.

Although the difference between the tremor of typical disseminated sclerosis and that of paralysis agitans is pathognomonic, yet the existence of a group of cases of disseminated sclerosis, as well as of one of cases of paralysis agitans without tremor, renders an exact discrimination in all cases impossible. It is a question, as yet, whether the form of paralysis agitans without tremor described by Charcot, and which is marked by pains in the extremities, rigidity, clumsiness, and slowness of movement, general motor weakness, a frozen countenance, impeded speech, and mental enfeeblement, is not in reality a diffuse or disseminated sclerosis.

The diagnosis of this disease, while readily made in a large number of cases on the strength of the characteristic symptoms detailed, may be regarded as impossible in a minority which some good authorities incline to regard as a large one.

SYNONYMS.—Chronic myelitis, Diffuse myelitis, Simple or Diffuse spinal sclerosis, Chronic transverse myelitis, Sclerosis stricte sic dicta (Leyden, in part), Gray degeneration.

The various forms of sclerosis thus far considered were at one time considered as varieties of chronic myelitis, and under different names, founded on leading symptoms, were considered to be merely local, and perhaps accidental, variations of one and the same morbid process. More accurate clinical and pathological analysis has separated from the general family of the scleroses one clearly demarcated form after another. Tabes dorsalis, disseminated sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and the combined forms of sclerosis have been successively isolated. Still, a large number of cases are left which cannot be classified either with the regular affections of the cord, limited to special systems of fibres, or with the

disseminated form last considered. They agree with the latter in that they are not uniform; they differ from it in that they are not multilocular. Not a few modern authors have neglected making any provisions for these cases, while others treat of them in conjunction with acute myelitis, of which disease it is sometimes regarded as a sequel. The term diffuse sclerosis is here applied to those forms of chronic myelitis which follow no special rule in their location, and to such as are atypical and do not correspond in their symptomatology or anatomy to the more regular forms of sclerosis. In regional distribution the foci of diffuse sclerosis imitate those of acute myelitis: they may be transverse, fascicular, or irregular.

MORBID ANATOMY.—In typical cases the lesion of diffuse sclerosis constitutes a connecting-link between that of the disseminated form and posterior sclerosis. Its naked-eye characters are the same. There is usually more rapid destruction of the axis-cylinders, more inflammatory vascularization, proliferation of the neuroglia-nuclei, and pigmentary and hyaline degeneration of the nerve-cells, than in the disseminated form.

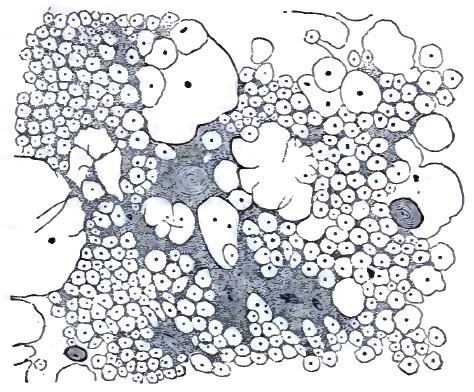

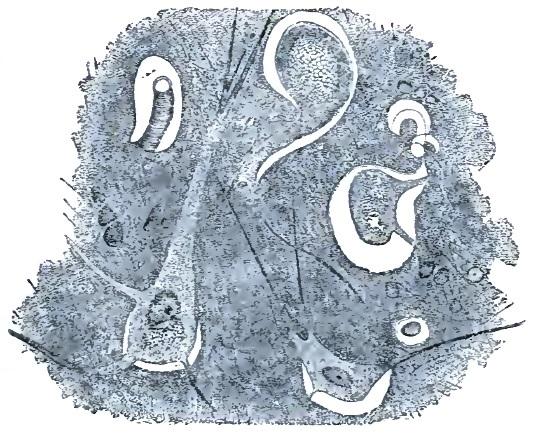

Syphilitic inflammation of the cord extends along the lymphatic channels, including the adventitial spaces, and leads to a diffuse fibrous interstitial sclerosis. In one case in which I suspected syphilis, though a fellow-observer failed to detect it after a rigid search, I found a peculiar form of what would probably be best designated as vesicular degeneration, according to Leyden, though associated with a veritable sclerosis. The lymph-space in the posterior septum showed ectasis; the blood-vessels were sclerotic, and each was the centre of the mingled sclerotic and rarefying change. It appears that while the interstitial tissue hypertrophied, the myelin of adjoining nerve-tubes was pressed together till the intervening tissue underwent pressure atrophy. The result was, the myelin-tubes consolidated, some axis-cylinders perished, others atrophied, a few remained, and, the myelin undergoing liquefaction, long tubular cavities resulted, running parallel with the axis of the cord, and exposed as round cavities on cross-section (Fig. 32). The changes in the cells of the anterior horn in the same cord (Fig. 33) illustrate one

of the common forms of disease to which they are subjected in the course of sclerotic disease.

FIG. 32.

FIG. 33.

FIG. 32.

FIG. 33.

The so-called myelitis without softening, or hyperplastic myelitis of Dujardin-Beaumetz, which is ranked by Leyden and Erb among the acute processes, properly belongs here. It is characterized by a proliferation of the interstitial substance, both of its cellular and fibrillar elements. The nerve-elements proper play no part, or at best a very slight or secondary one. In the sense that this affection occurs after acute diseases and develops in a brief period it may be called an acute myelitis, but both in its histological products and its clinical features it approximates the sclerotic or chronic inflammatory affections of the cord. As far as the clinical features are concerned, this is particularly well shown in the disseminated myelitis found by Westphal after acute diseases, such as the exanthematous and continued fevers.

CLINICAL HISTORY.—Impairment of motion is the most constant early feature of chronic myelitis; in the transverse form it may be as absolute as in the severest forms of acute myelitis; as a rule, however, it is rather a paresis than a paralysis. The patient is usually able to walk, manifesting the paraparetic gait: he moves along

slowly, does not lift his feet, drags them along, makes short steps; in short, acts as if his limbs were heavily weighted. This difficulty of locomotion is preceded and accompanied by a tired feeling before other sensory symptoms are developed. Rigidity of the muscles, like that found in disseminated sclerosis, is a common accompaniment, and may even preponderate over the paresis to such an extent as to modify the patient's walk, rendering it spastic in character. In such cases the muscles feel hard to the touch, and the same exaggerated reflex excitability may be present as was described to be characteristic of spastic paralysis.

If, while the leg is slightly flexed on the thigh, the foot be extended,149 so as to render the Achilles tendon and the muscles connected with it tense, and the hand while grasping the foot suddenly presses the latter to still further extension, a quick contraction occurs, which, if the pressure be renewed and kept up, recurs again and again, the succession of the involuntary movements resembling a clonic spasm. This action is termed the ankle-clonus or foot-phenomenon. Gowers has amplified this test of exaggerated reflex excitability by adding what he calls the front-tap contraction. The foot being held in the same way as stated above, the examiner strikes the muscles on the front of the leg; the calf-muscles contract and cause a brief extension movement of the foot. It is believed that the foot-clonus and the front-tap contraction are always pathological, but a few observers, notably Gnauck, leave it an open question whether it may not occur in neurotic subjects who have no organic disease. Gowers considers the foot-clonus found in hysterical women as spurious, and states that it differs from the true form in that it is not constant, being broken by voluntary contractions, and does not begin as soon as the observer applies pressure. But I have seen the form of clonus which Gowers regards as hysterical in cases of diffuse sclerosis. With regard to the front-tap contraction, its discoverer150 admits that it may be obtained in persons in whom there is no reason to suspect organic disease. It is significant only when unequal on the two sides.

149 By extension the approximation of the dorsal surface to the tibial aspect of the leg —what some German writers call dorsal flexion—is meant.

150 Gowers, The Diagnosis of the Diseases of the Spinal Cord, 3d ed., p. 33.

In severe cases contractures are developed in the affected muscular groups, being, as a rule, preceded by the rigidity, increased reflex excitability, and the thereon dependent phenomena above detailed. These contractures may be like those of spastic paralysis, but usually the adductors show the chief involvement, and sometimes the leg becomes flexed on the thigh and the thigh on the abdomen in such firm contraction that the patient, albeit his gross motor power is not sufficiently impaired, is unable to move about, and is confined to his bed, his heel firmly drawn up against his buttock. It is stated by Leyden that the contracted muscles occasionally become hypertrophied—an occurrence I have not been able to verify. As a rule, some muscular groups are atrophied, though the limbs as a whole, particularly in those patients who are able to walk about, are fairly well nourished.

Pain in the back is a frequent accompaniment of diffuse sclerosis. It is not pronounced, but constant.

The drift of opinion to-day is to regard pain in the spinal region as not pathognomonic of organic spinal affections. It is true that pain is a frequent concomitant of neuroses, and that it is more intense and characteristic in vertebral and meningeal disease; but in denying a significance to pain in the back as an evidence of diffuse disease of the cord itself, I think many modern observers have gone to an extreme. It is particularly in diffuse sclerosis that a dull heavy sensation is experienced in the lumbo-sacral region; and in a number of my cases of slowly ascending myelitis and of tabes dorsalis the involvement of the arms was accompanied by an extension of the same pain, in one case associated with intolerable itching, to the interscapular region. It cannot be maintained that the pain corresponds in situation to the sclerotic area. It is probably, like the pain in the extremities, a symptom of irradiation, and corresponds in distribution to that of the spinal rami of the nerves arising in the affected level.

As the posterior columns are usually involved in transverse myelitis, the same lancinating and terebrating pains may occur as in tabes dorsalis. As a rule, they are not as severe, and a dull, heavy feeling, comparable to a tired or a burning sensation, is more common. A belt sensation, like that of tabes, and as in tabes corresponding to the altitude of the lesion, is a much more constant symptom than acute pains.

Cutaneous sensibility is not usually impaired to anything like the extent found in advanced tabes. It is marked in proportion to the severity of the motor paralysis; where mobility is greatly impaired, profound anæsthesia and paræsthesia will be found; where it is not much disturbed, subjective numbness, slight hyperæsthesia, or tingling and formication may be the only symptoms indicating sensory disturbance; and there are cases where even these may be wanting.

The visceral functions are not usually disturbed. In intense transverse sclerosis of the upper dorsal region I observed gastric crises, and in a second, whose lesion is of slight intensity, but probably diffused over a considerable length of the cerebro-spinal axis, there is at present pathological glycosuria. The bladder commonly shows slight impairment of expulsive as well as retaining power, the patients micturating frequently and passing the last drops of urine with difficulty. Constipation is the rule. The sexual powers are usually diminished, though rarely abolished. As with sclerotic processes generally, the sexual functions of the female, both menstrual and reproductive, are rarely disturbed.

It is not necessary to recapitulate here the symptoms which mark diffuse sclerosis at different altitudes of the cord. With this modification, that they are less intense, not apt to be associated with much atrophic degeneration, nor, as a rule, quite as abruptly demarcated in regional distribution, what was said for acute myelitis may be transferred to this form of chronic myelitis. The progress of diffuse sclerosis is slow, its development insidious, and the history of the case may extend over as long a period as that of diffuse

sclerosis. Sooner or later, higher levels of the cord are involved in those cases where the primary focus was low down. In this way the course of the disease may appear very rapid at one time, to become almost stationary at others. Of three deaths which occurred from the disease in my experience, one, in which there were distinct signs of involvement of the oblongata,151 occurred from sudden paralysis of respiration; a second from a cardiac complication, which, in view of some recent revelations concerning the influence of the tabic process on the organic condition of the valves of the heart, I should be inclined to regard as not unconnected with the sclerosis; and in a third, from bed-sores of the ordinary surgical variety. The malignant bed-sore is not of frequent occurrence in this disease.

151 On one occasion the patient had momentary anarthria, followed a day later by two successive periods of anarthria, lasting respectively about twenty seconds and one minute, one of which was accompanied by diplopia of equally brief duration.

PROGNOSIS.—The disease may, as in the instances cited, lead to a fatal termination, directly or indirectly, in from three to twenty years. The average duration of life is from six to fifteen years, being greater in cases where the sclerotic process is of slight intensity, even though it be of considerable extent, than where it is of maximum or destructive severity in one area, albeit limited. I am able to say, as in the case of tabes dorsalis, that a fair number of patients suffering from this disease whom I have observed for from two to six years have not made any material progress in an unfavorable sense in that time. One cure152 occurred in this series, of a patient manifesting extreme contractures, atrophies, bladder trouble, and ataxiform paresis, where the cause was plainly syphilis, and the histological character of the lesion is somewhat a matter of conjecture in consequence. Diffuse sclerosis of non-syphilitic origin—and this may apply also to established sclerosis in syphilitic subjects—is probably as unamenable to remedial treatment as any other sclerotic affection.

152 The patient went, under direction of Leonard Weber and R. H. Saunders, to Aixla-Chapelle, where this happy result was obtained after mixed treatment had

practically failed.

The same rules of DIAGNOSIS applicable to transverse myelitis of acute onset apply, level for level, to the diagnosis of transverse myelitis of insidious development, the history of the case often furnishing the only distinguishing point between the acute and the chronic form.

The main difference between the diffuse sclerosis and acute myelitis, clinically considered, consists in the gradual development of symptoms in the former as contrasted with their rapid development in the latter disease. Acute myelitis is established within a few hours, days, or at most, in the subacute forms, a few weeks; chronic myelitis requires months and years to become a clearly-manifested disorder. It is the essential correspondence of the symptoms of both conditions, intrinsically considered, which renders it impossible to distinguish clinically and in the absence of a history of the case between some cases of acute myelitis in the secondary period and the processes which are primarily of a sclerotic character.

It is unusual to find the degeneration reaction in myelitis of slow and gradual development. Sometimes there is diminished reaction to both the faradic and galvanic currents, or the so-called middle form of degeneration reaction is obtained from atrophied muscles, the nerve presenting normal or nearly normal irritability, and the muscle increased galvanic irritability and inversion of the formula.

Among the less reliable or accessible points of differentiation between the residua of acute myelitis and the chronic form is the history of the onset and the age of the patient at the time of the onset. Myelitis in young subjects is more likely to be of the acute kind; in older persons it is more apt to be chronic.

In the diagnosis of diffuse sclerosis the question of differentiation from neuroses not based on ascertainable structural disease, such as are called functional, will be most frequently raised. In differentiating between organic and functional spinal disorders all known exact signs of organic disease must be excluded before the