A CHAIR, A HOUSE, A SIGNATURE

Fall 2022

A CHAIR, A HOUSE, A SIGNATURE

Fall 2022

JINGWEN GU Section 02_WILLIAMS || jg2369

The signature is considered as the manifestation of a certain identity; a quest of architectural exploration thereof thus extracts critical facets of the identity and remanifests it in the language of spatial compositions. Nine such compositions are constructed to interpret the signature on various levels of literality and via different aspects of its spatial qualities, exploring ideas of pressure and porosity, regulation and freedom, eventually amounting to a dialectic of restraint and catharsis.

The inherent sense of regulation and construction within the Chinese characters is at tension with the speed and fluidity when writing the signature, thus creating contrasting conditions of regulation and freedom, restraint and catharsis all in one calligraphic manifestation.

Explores the inherent skeletal construction of Chinese characters versus the organic calligraphic insinuations, the regulations against the force of free exuberance.

Synthesis of the previous four drawings where an organic form is found by overlaying the porosity, external forces, and internal structure together. The organicity of this form is in turn contrasted and confined by the regulation lines and segments, creating a condition of imprisonment and tension.

The figure-ground condition in drawing 5 is multiplied, with the organic and orthogonal systems receding behind each other in turns, thus creating an alternating pattern of regulation and freedom.

Bristol, 8’’’×8’’×4’’

Derived from drawing 2, one single sheet of paper is scored where the percieved forces are applied to the structural skeleton of the signature, with perforations to create porosity.

Iteration based on Model 1 where the intersection of curves is smoothened and different foided parts of the paper allowed to re-intersect with each other spatially.

Bristo, wood, and chipboard, 8’’’×11’’×2’’

A parallel reinterpretation of the interplay between the organic and the orthogonal, with intentionally curated moments when one emerges from or recedes below the other.

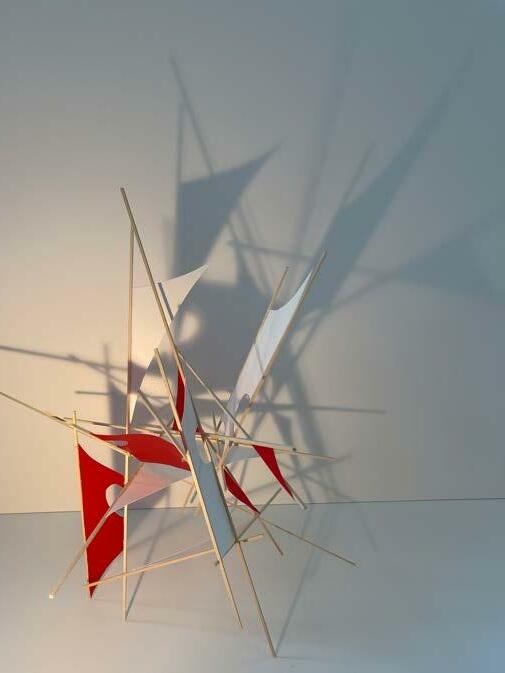

Bristol, mylar, and wood, 6’’’×6’’×8’’

Architecturalization of Drawing 3, where the orthongonal construction system is distorted to allow for a more dynamic use of the planar language.

Bristol, wood, and chipboard, 10’’’×20’’×8’’

The multiplication of Model 3 based on Drawing 6. The organic forms are sandwiched between the two layers of orthogonal reliefs, reaching outward at some points and firmly anchored at others, thus spatializing the feeling of confinement in the signature and the identity it expresses.

A more controlled version of Model 5 where the language of lines and planes is upgraded to that of volumes and voids, while the entire construction is flattened out along a single plane to assume qualities of a bas-relief.

Bristol and wood, 32’’×6‘’×8‘’

The pseudo-volumetric language of Model 1 and the orthogonal language of Model 3 and 6 are brought together in a linear composition to allow the ordered stripes to intertwine with themselves to form chaotic knots, hence creating an oscillation between regularity and irregularity, determinism and chance.

The figure-ground conditions in Model 3 is reversed so that the organic form becomes a void carved into a box volume, thus exploring spatial opportunities by making solid the external confining forces that frame and mold the signature.

Through the analysis and the architecturalization of my signature, discovered that it is imbued with a sense of struggle and tension between construct and improvisation, restraint and catharsis. Much like models 3, 6, and 8, the chair is also designed as two contradictory yet symbiont pieces: one to provide the thesis of the chair, the other to constitute its antithesis, the two oppressing and confining each other. With the addition of the human occupant, the two chairs are synthesized as a new construct: the Anti-Chair, one which both refuses and imprisons the occupant, which does not support but is instead supported by the occupant, and thus is at once welcoming and intimidating. The occupant becomes a voluntary prisoner of architecture seduced and trapped by this dialectic ma nifest in the signature.

10 study models are conceptually and morphologically derived from the previous drawings and models to investigate potential conditions of the chair under human occupation.

The final chair largely follows Chair 8 and is thus designed to be the synthesis of the dialectic between exuberance and regulation, where a series of orthogonal members derived from regular frames are rotated and interlocked with each other. The chair is shaped in an inviting posture but the rigidity of its members refuses intimacy, creating tension with its sitter.

The largely orthogonal and regulated chair is combined with a much more organic antithetical counterpart, which can also be a chair on its own, and constitute a grand synthesis which is the Anti Chair. The two pieces interlock and are in tension with each other yet have no structural soundness unless the human is seated in it; the human thus becomes the joinery component and serves to hold up the chair, instead of the chair supporting the human. It is thus hard to get off the chair, whose role subsequently shifts from that of servitude to that of oppression. The human-instrument relationship is inverted, hence the name Anti-Chair, which not only manifests the concept of imprisonment but also explores the endless dialectic iteration of thesis-antithesis-synthesis, with the scope of the chair gradually zooming out from a single component surface to one chair, then to the pair of chairs, and finally to the system between the chair and the human.

The conceptual construct of the house is very similar to that of the chair; however, now that the chairs are placed in and regarded as the primary occupants of the house, the agenda for the final project becomes to explore the architectural paradigms of the instruments (non-humans) as opposed to those of humans. Again, the two form a dialectic structure in which one oppresses the other.

The human architectural logic is epitomized by the open plan floor slab, which allows for infinite opportunities of circulation. Orthogonality follows from the horizontality to allow spaces to be layered and stacked.

The paradigm of the chairs is defined conversely: with no demand for circulation, chairs can occupy stationary voids scattered across the space with no regard for vertical variation. Hence the wall becomes the best archetype to accomodate the chairs, and the subseteqent form can be highly organic.

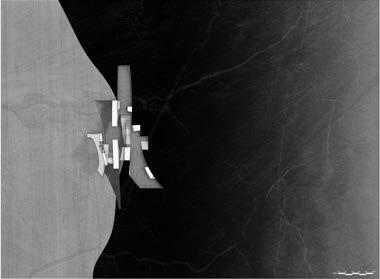

Sited on a cliff, the floor archetype (horizontal/human logic) is strongest near the top of the cliff where the terrain is flatter, and the wall archetype (vertical/chair logic) us strongest near the bottom of the cliff which allows for more expansive vertical space. The two archetypes and paradigms thus populate from their origin of spatial strength towards each other along the long, narrow site, hence forming a condition of mutual oppression: the floor slabs are more and more disintegrated by the more massive walls, while the latter is domesticated and distorted by the floor slabs on the other end.

The experience of such a house from the human perspective is thus one of alternating freedom and restraint, and the same can be said from the perspective of the chairs: they are anti-houses of each other, yet together they from a conflicting dialectic synthesis.

Auxilliary structures

Floors (human paradigm)

Walls (chair paradigm)

Site

Exploded Axonometric

Form Generation Diagram

Converse to the previous diagram, the floors are also gradually disintegrated by the walls along the reverse direction. The two logics, the humans and the chairs, are thus antithetical, oppressive, yet symbionic to each other.