FAMILY ORBITS

Gertrude Stein’s extended family was part of a large German Jewish community in Baltimore. Her father Daniel immigrated to this city in 1841 as a child from Bavaria, where opportunities were closed to Jews. Here, he joined his brothers in the operation of a successful garment-manufacturing and ready-to-wear clothing business. Gertrude’s mother, Amelia Keyser, was the daughter of immigrants from the 1820s who placed a high value on gentility and culture. Daniel and Amelia Stein relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1862 to open a branch of Stein Brothers’ Clothiers, and that is where their children were born — Gertrude, the youngest, in 1874. The family lived in Vienna and Paris for a few years, then moved in 1880 to Oakland, California, where Gertrude reveled in the outdoors. Eventually, Daniel co-founded the Omnibus Railroad and Cable Company in San Francisco. Tragically, Amelia died when Gertrude was just fourteen; Daniel died three years later. Their oldest child, Michael, took up the reins of the business, and Gertrude went to live with her aunt Fanny and uncle David Bachrach in Baltimore. But her closest companion was her brother Leo, with whom she shared a voracious appetite for books.

Stein’s family relationships, marked by intimacy and distance, comfort and calamity, encouraged her love of learning, provided a strong sense of Jewish solidarity, and furnished her with financial stability — crucial foundations for the writer in the making.

Gertrude Stein as an infant with her mother Amelia Stein. Photograph by P. L. Perkins, Baltimore, c. 1874.

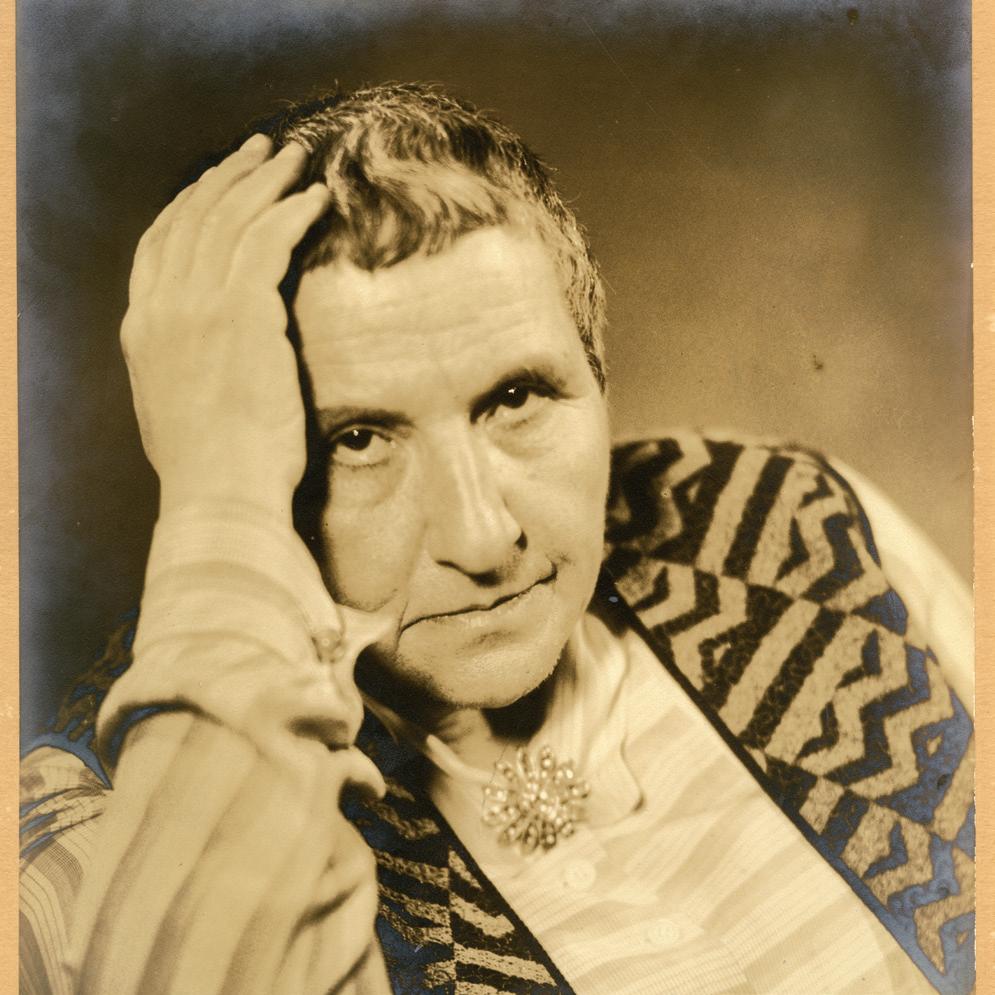

Gertrude Stein. Bachrach Studio, Baltimore, c. 1900.

SCIENTIFIC CIRCUITS

In 1893, Stein entered the Harvard University “annex” for women, soon to be renamed Radcliffe College. She was attracted to the sciences — fields, she believed, in which “a solution was a way to a problem.”1 She joined the psychological laboratory of Hugo Münsterberg, an early adopter of the new field of experimental psychology and an enthusiastic teacher of women students, Stein in particular. She also relished her classes with the psychologist and philosopher William James, whom she regarded as brilliant and humane. Under their direction, Stein devised experiments meant to illuminate subjective experience and subconscious forces — the “under self,” in James’s words, what Stein later called an individual’s “bottom nature.”2

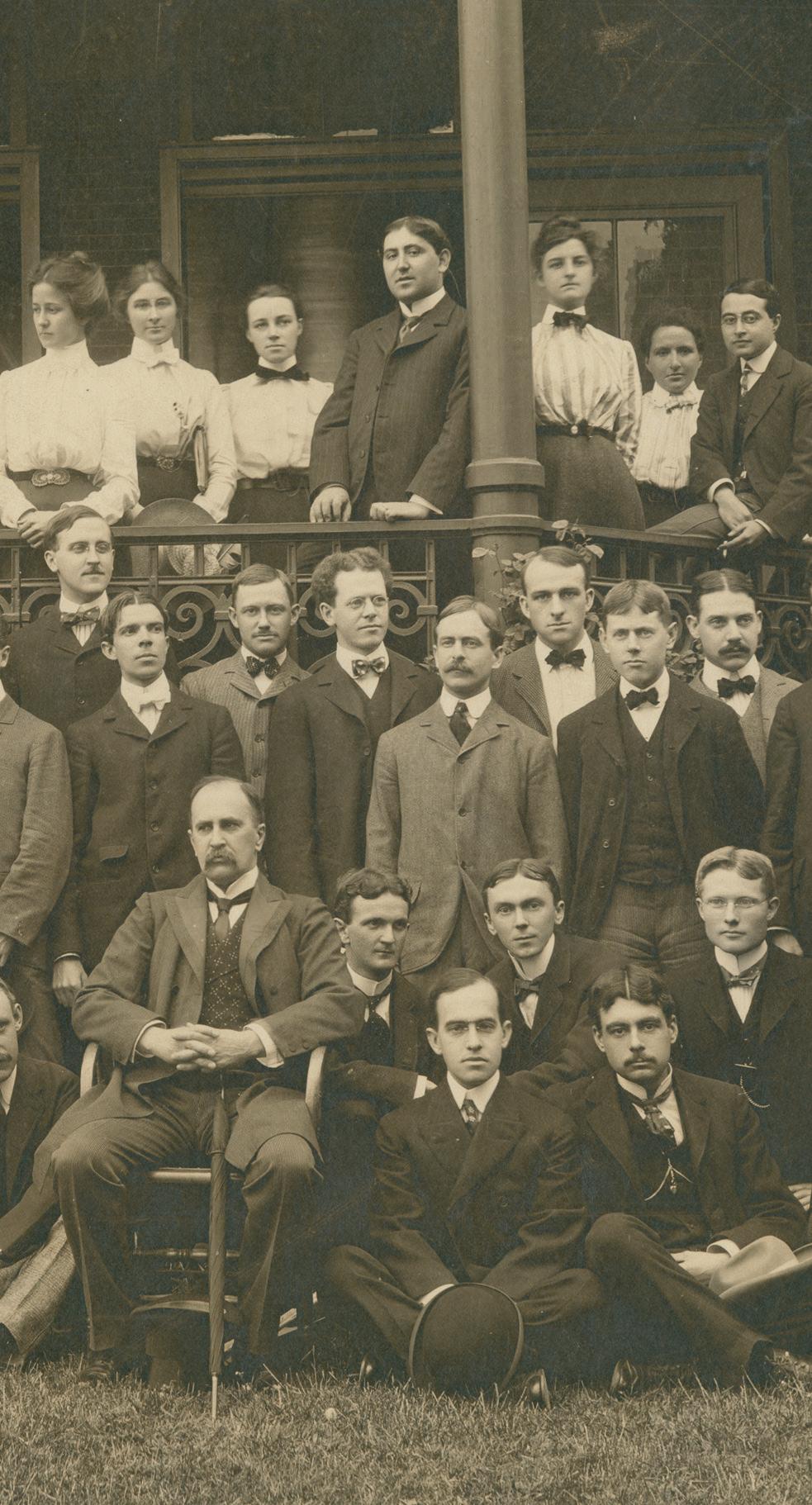

In 1897, with James’s encouragement, she applied and was accepted to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. She loved her anatomy classes with Franklin Mall and Lewellys Barker, and for the first two years, she did very well. Then her grades began to decline. She claimed later in life that boredom and dislike for the clinical rotations, especially obstetrics, dampened her enthusiasm. But it is likely that two other factors influenced her waning effort. Undoubtedly, the environment was not hospitable to women students. In addition, she became embroiled in a confusing, depressing love triangle with two other women. She left medical school in 1901, one semester short of a degree and too detached even to finish an article that could have provided some needed credit.

Nevertheless, her years of training as a scientist fundamentally formed her way of thinking. She was oriented to inquiry and detailed analysis, and attuned to the quirks and riddles of human psychology.

Detail from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Class of 1901, with Gertrude Stein in the rear, second from right. Photograph by John Betz, c. 1901. Alan Mason Chesney Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

In Baltimore in these years, her social group included Dr. Claribel Cone and Etta Cone. As unmarried, educated women, art collectors, and world travelers, the Cone sisters certainly would have offered to the younger Stein models for a kind of life she could imagine for herself.

AVANT-GARDE ALLIANCES

With an uncertain future ahead of her, Stein turned to her brothers. In 1903, she joined Leo at his quarters at 27 rue de Fleurus in Paris; Michael and his family soon moved to a nearby apartment. Their manner of living was not extravagant, but American dollars could be stretched in France. In both households, studying, making, and collecting art became central occupations. Like many white Europeans and North Americans of the time, for whom non-Western art was a revelation, they were initially interested in Japanese prints. Those works taught them to see art differently. Soon they were pursuing startling modern canvases by painters who had absorbed the lessons — and co-opted the styles — of art made in Africa, Oceania, and pre-Roman Europe.

Two of those artists, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, became personal friends. Stein and Picasso grew especially close through the exchange of portraits. He painted her portrait in 1905 – 06, a work that was pivotal to his development of Cubism and now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And she represented him in a series of word portraits intended to reveal his inner being.

Stein spent several years after medical school intensively reading and writing, but did not know how to render her primary topic — a love triangle based on her own experience — into a work that

Leo Stein, Gertrude Stein and Michael Stein standing outside of the rue de Fleurus apartment, possibly 1906. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 11, SF.13.

Gertrude Stein, by Pablo Picasso, 1905 – 06. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

could be published. Finally, while translating three stories by the French novelist Gustave Flaubert, she hit upon an approach that worked. Three Lives (1909) follows Flaubert’s example by focusing on the daily lives of three ordinary women. But Stein drew her characters in accordance with ideas about psychological “types” current in early twentieth-century science. “Melanctha,” the most innovative of the three stories, is set in a fictionalized Baltimore and portrays an African American woman torn between romantic options. Melanctha’s psychological profile exemplifies the profound racism of the science of the time. Yet, Stein’s method — tracking the step-by-step internal shifts of a character over time — eventually bumps up against the limits of “type.” Melanctha proves too complicated for her categories.

Like her heroine, Stein was also experiencing a sexual awakening. In 1907, she met Alice B. Toklas, with whom she had much in common. Toklas was a Californian from a middle-class Jewish family. She too was artistically oriented and eager to break away from the conventional paths marked out for women. Toklas moved into the rue de Fleurus apartment, and eventually Leo moved out. By 1908, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas considered themselves married. In 1910, Stein wrote one of her first word portraits, “Ada,” about Toklas.

Many other alliances sustained Stein over the years. Friends who provided moral support, like Carl Van Vechten and Mabel Foote Weeks. Artists with whom she identified, like Juan Gris. Fellow writers who helped her get published, like Ford Madox Ford and Robert Carlton Brown. And women who, like her, flouted gender norms to claim important literary and artistic roles, such as Mabel Dodge, a patron of the arts; the Cone sisters, globe-trotters and astute collectors;

Portrait of Mabel Dodge at Villa Curonia, by Gertrude Stein. Florence: Mabel Dodge, 1912.

Stein and Toklas in Venice. Real photo postcard, photographer unknown, 1908. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Mildred Aldrich, a journalist; Natalie Barney, a lesbian-feminist writer; and Marcelle Ferry, a surrealist poet.

MODERNIST NETWORKS

Stein was a dedicated and prolific writer. She sketched ideas in little notepads, then drafted full pieces in composition notebooks. She worked nights at a Renaissance-era table beneath paintings by her avant-garde comrades. In the mornings, Toklas typed up Stein’s manuscripts.

But this productivity did not lead directly to publication. Mainstream publishers in the 1910s and 1920s shied away from Stein’s work, worried that it would not appeal to their customers. Her word portraits delve into characters without the usual cues — there is a who, but no what, where, when, or why. Her narratives move along with continuous activity, but contain nothing you could call a traditional plot. Some texts, like Tender Buttons (1914), look like poems but certainly do not behave like poems. Stein’s writing of this period requires a different kind of reading. The words on the page do not construct an alternate reality for the reader’s imagination, a stage where a life-like story plays out. Nor do they lead us, through contemplation, to a designated emotion or insight. The words and phrases are more like tiny organisms observed through a microscope, moving in patterns that gradually yield a meaning that is not literal . . . but is indirectly intelligible. The line, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” was Stein’s favorite example of her approach. The repetition makes the word for a well-known and symbolic flower into something strange — liberating it from layers of tradition. As Stein put it, “I think that in that line the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years.”3

Of course, other writers of the period were also wrestling language into unfamiliar forms, like T. S. Eliot, Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and Virginia Woolf. Stein was acutely aware of this company and her status within it. When her giant, semiautobiographical novel, The Making of Americans, was finally published in 1925, it was important to her that the printer had also printed Joyce’s giant, semi-autobiographical novel, Ulysses, in 1922. She proclaimed on the cover of her book its dates of composition, 1906 to 1908, to show that she had finished first. Much of her writing appeared alongside that of her peers in inexpensive anthologies, short-lived journals, and so-called “little magazines” — venues dedicated to modern literature, where comparison was inevitable.

Those brave, shoestring publishing efforts were often driven by a sense of responsibility. Editors and publishers who supported modernist writing, with its bold topics and unsettling techniques, believed it was essential for literature to express and embody the radical upheavals of the early twentieth century. In many parts of the world, farmers and villagers were relocating to industrialized cities. Work, recreation, travel, and home life threw people into contact with new technologies like automobiles, electricity, telephones, movies, and the machines of mass production. And the socio-political structures that had long oppressed women, workers, immigrants, people of color, and colonized subjects were meeting with vigorous resistance. The tense balance of power created and controlled by the colonizing nations of Europe collapsed violently in the trenches of the First World War. Stein’s friends and acquaintances, like the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, her one-time disciple

Ernest Hemingway, and the artist-provocateur Tristan Tzara, founder of the avant-garde faction called Dada, had direct experience of the war — as did Stein, who, with Toklas, delivered medical supplies to hospitals across France in a car they nicknamed “Auntie.”

The international and interlocking gears of modern societies and economies had a counterpart in the esoteric circles of modern art: both existed as networks. For the painters, musicians, and writers who, like Stein, were rejected by mainstream cultural institutions, their own communities often supplied the collaborators, investors, and audiences needed to bring new work to life. This state of affairs made for tricky social relations; your teammate was also, potentially, your rival.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stein experienced these complications up close with Éditions de la Montagne, a press run by friends, with whom she published two books before the friendships cracked under pressure. Backing away from ensemble enterprises, her next step was to start her own imprint, the Plain Edition, managed by Toklas. Stein and Toklas tried out several strategies for publishing Stein’s work in an attractive but affordable format. Even their tiny operation necessarily involved a network of printers, booksellers, publicists, and, of course, readers.

In 1933, Stein made a decisive turn. She wrote a frank, gossipy, and utterly readable memoir, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Purporting to be an account by Toklas — it even reproduced Toklas’s manner of speaking with a precision that only her long-time partner could muster — it offered Great Depression-era readers a fascinating tour of the modernist scene in Paris. Published by one of the mainstream presses that had so far

The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Contact Editions, Three Mountains Press, 1925.

Real photo postcard, postmarked July 19, 1920, to Robert Carlton Brown from Gertrude Stein, with image of Stein and Toklas in their car delivering hospital supplies for the American Fund for the French Wounded during World War I.

OBJECT LIST

Unless otherwise noted, all materials are from the Robert A. Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein Materials at the Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. Other Sheridan Libraries Special Collections materials marked as SLSC.

FAMILY ORBITS

1. Gertrude Stein as an infant with her mother Amelia Stein. Photograph by P. L. Perkins, Baltimore, c. 1874.

2. Gertrude Stein as a child. Photograph by N. Stockmann, Vienna, c. 1878.

3. The Stein family in California. Photograph by Arthur O. Eppler, San Francisco, c. 1880. Facsimile. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

4. 215 East Biddle Street, where Gertrude Stein lived while attending medical school. Photograph by Eli Pousson, 2018. Facsimile. Baltimore Heritage, CC BY 4.0.

5. Leo Stein and Gertrude Stein. Bachrach Studio, Baltimore, c. 1900.

6. La Première Année de Grammaire, by Larive and Fleury. Paris: Armand Colin, 1887. With Stein’s annotations.

7. The American Commonwealth, by James Bryce. New York: Macmillan, 1888. With Stein’s bookplate.

SCIENTIFIC CIRCUITS

8. Psychology: The Briefer Course, by William James. New York: Henry Holt, 1892. SLSC.

9. Mental Development in the Child and the Race: Methods and Processes, by James Mark Baldwin. New York, London: Macmillan, 1895. With Stein’s bookplate.

10. “Normal Motor Automatism,” by Leon Solomon and Gertrude Stein. The Psychological Review, September 1896.

11. “Cultivated Motor Automatism: A Study of Character in its Relation

to Attention,” by Gertrude Stein. The Psychological Review, May 1898.

12. The Nervous System and its Constituent Neurones, Designed for the Use of Practitioners of Medicine and of Students of Medicine and Psychology, by Lewellys F. Barker. Plate by Max Broedel. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1899. SLSC.

13. Hand Atlas of Human Anatomy, with the Advice of Whilhelm His, translated from the third German edition by Lewellys F. Barker, with a preface by Franklin P. Mall. Volume 3. Leipzig: S. Hirzel; New York: G. E. Stechert, 1900 – 03. Institute for the History of Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

14. Typescript of “The Value of a College Education,” by Gertrude Stein. Unpublished, 1899. Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Baltimore Museum of Art.

15. Gertrude Stein’s application to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 1897. Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

16. Letter to Lewellys F. Barker from Gertrude Stein declining to revise an embryology article, n.d., 1902. Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

BACKGROUNDS

Gertrude Stein studying at Johns Hopkins University. Photographer unknown, c. 1900. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Detail from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Class of 1901, with Gertrude Stein in the rear. Photograph by John Betz, c. 1901. Alan Mason Chesney Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

AVANT-GARDE ALLIANCES

17. Trois Contes, by Gustave Flaubert. Paris: G. Charpentier, 1877. SLSC.

18. Three Lives, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Grafton Press, 1909.

19. What Is Remembered, by Alice B. Toklas. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1963. Inscribed by Toklas.

20. “Ada” in Geography and Plays, by Gertrude Stein. Boston: The Four Seas Company, 1922. Inscribed by Stein to William A. Bradley.

21. What Is Remembered, by Alice B. Toklas. London: Michael Joseph, 1963.

22. “Matisse,” by Gertrude Stein. Camera Work, August 1912.

23. “If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso,” by Gertrude Stein. Vanity Fair, April 1924.

24. “The Life and Death of Juan Gris,” by Gertrude Stein. transition, July 1927.

25. Gertrude Stein at Bilignin. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, c. 1935. Inscribed by Stein to Alexander Smallwood. SLSC.

26. Portrait of Mabel Dodge at Villa Curonia, by Gertrude Stein. Florence: Mabel Dodge, 1912. One copy inscribed by Stein to Etta Cone. One copy inscribed by Mabel Dodge to Charlotte Becker.

27. “Speculations, or Post-Impressionism in Prose,” by Mabel Dodge. Arts & Decoration, March 1913.

28. Letter to Claribel Cone from Gertrude Stein about the publication of Tender Buttons, with gallery enclosures. March or May 1914. Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Baltimore Museum of Art.

29. Tender Buttons, by Gertrude Stein, New York: Claire Marie, 1914. From Holbrook Jackson’s library.

30. Excerpts from Tender Buttons, by Gertrude Stein. transition, fall 1928. Inscribed by Stein to Bobsie [Robert Bartlett Haas].

31. Hilltop on the Marne, by Mildred Aldrich. Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1915. SLSC.

32. Aventures de l’esprit, by Natalie Clifford Barney. Paris: Éditions ÉmilePaul Frères, 1929. SLSC.

33. Letter to Marcelle Ferry from Gertrude Stein, December 8, 1930. SLSC.

34. Letter to Ford Madox Ford from Gertrude Stein, September 19?, 1924. SLSC.

35. Two postcards to Mabel “Mamie” Foote Weeks from Gertrude Stein, dated December 24, 1904 and October 7, 1933.

36. One postcard, postmarked July 19, 1920, and one letter, postmarked April 22, 1931, to Robert Carlton Brown from Gertrude Stein.

BACKGROUNDS

Gertrude Stein standing outside of the rue de Fleurus apartment, c. 1906. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 11, SF.11.

Gertrude Stein sitting in front of paintings at 27 rue de Fleurus, including Picasso’s portrait of her. Photographer unknown, c. 1910. Library of Congress.

MODERNIST NETWORKS

37. Ulysses, by James Joyce. London: Published for the Egoist Press, London by John Rodker, Paris, 1922. Adolphus Emmart’s copy, given in memory of Barney D. Emmart and Milagros Ortega Costa, 2022. SLSC.

38. The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Contact Editions, Three Mountains Press, 1925.

39. God’s Trombones, by James Weldon Johnson. New York: Viking Press, 1927. SLSC.

40. A Draft of XVI Cantos of Ezra Pound: For the Beginning of a Poem of Some Length. Inscribed by Pound to Olga Rudge. Paris: Three Mountains Press, 1925. Irene and Richard Frary Special Collections.

41. “We Came,” by Gertrude Stein. Readies for Bob Brown’s Machine, edited by Robert Carlton Brown. Cagnes-surMer, France: Roving Eye Press, 1931.

42. Poems by Langston Hughes. The Book of American Negro Poetry, edited by James Weldon Johnson. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1931. SLSC.

43. “Lettre-Océan” by Guillaume Apollinaire. Calligrammes: Poèmes de la paix et de la guerre, 1913 – 1916. Paris: Mercure de France, 1918. SLSC.

44. DADA #3, edited by Tristan Tzara, December 1918. SLSC.

45. Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers with “Two Women,” by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Contact Editions, Three Mountain Press, 1925.

46. Transatlantic Review, edited by Ford Madox Ford, with contributions by Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and Tristan Tzara, among others, April 1924. SLSC.

47. Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf. Published by Leonard & Virginia Woolf at The Hogarth Press, Hogarth House, 1921. SLSC.

48. Composition as Explanation, by Gertrude Stein. London: Leonard and Virginia Woolf (Hogarth Press), 1926. Inscribed by Stein to the Woolfs.

49. Morceaux choisis de la fabrication des américains: Histoire du progrès d’une famille, by Gertrude Stein, translated by Georges Hugnet. Paris: Éditions de la Montagne, 1929.

50. Dix portraits, by Gertrude Stein, translated by Georges Hugnet and Virgil Thomson. Paris: Éditions de la Montagne, 1930. Inscribed by Stein.

51. Lucy Church Amiably, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Imprimerie Union [Plain Edition], 1930.

52. Before the Flowers of Friendship Faded Friendship Faded, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Plain Edition, 1931.

53. How to Write, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Plain Edition, 1931. Inscribed by Stein to Sherwood Anderson.

54. Operas and Plays, by Gertrude Stein. Paris: Plain Edition, 1932. Inscribed by Stein to Katharine Cornell.

55. Matisse Picasso and Gertrude Stein with two shorter stories, Gertrude Stein, Paris: Plain Edition, 1933. Inscribed by Stein.

56. Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, part I, by Gertrude Stein. The Atlantic, May 1933.

57. Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1933. Inscribed by Stein to Maurice? [Darantiere].

58. “The Story of a Book,” by Gertrude Stein. Wings, September 1933.

59. Alice Toklas and Gertrude Stein embark on their lecture tour of America. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, 1934.

60. Lectures in America, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Random House, 1935. Inscribed by Stein to Bobsie [Robert Bartlett Haas].

61. Everybody’s Autobiography, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Random House, 1937.

62. Page of manuscript for “Vision of Holy Ghost,” Four Saints in Three Acts, by Virgil Thomson, libretto by Gertrude Stein, n.d.

63. Flier for premiere of Four Saints in Three Acts at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, February 1934.

64. Playbill for Four Saints in Three Acts premiere at the Wadsworth Atheneum, February 1934.

65. Playbill for Four Saints in Three Acts at the Broadway Theatre, New York, NY, April 1952 reprisal.

66. Four Saints in Three Acts LP, abridged version by Virgil Thomson. RCA Victor, 1964 (1947).

67. “If You Have Three Husbands,” part 2, by Gertrude Stein. Broom, June 1922.

68. “The Fifteenth of November,” by Gertrude Stein. The Criterion, edited by T.S. Eliot, January 1926.

69. “Poem pritten on pfances of Georges Hugnet,” by Gertrude Stein. Pagany: A Native Quarterly, January – March 1931.

70. “Autobiographies,” excerpt from Everybody’s Autobiography, by Gertrude Stein, translated by May Tagnard, Barronne d’Aiguy. Confluences, February 1943.

71. Excerpt from “Stanzas in Meditation,” by Gertrude Stein, with translation by Marcel Duchamp. Orbes, Winter 1932 – 33. SLSC.

72. Excerpt from “Stanzas in Meditation,” by Gertrude Stein. Life and Letters ToDay, Winter 1936.

73. Excerpt from “Stanzas in Meditation,” by Gertrude Stein. Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, February 1940.

74. Excerpt from “Stanzas in Meditation,” by Gertrude Stein. 100 American Poems: Masterpieces of Lyric, Epic and Ballad, from Colonial Times to the Present, edited by Selden Rodman. New York: New American Library, 1948. ON THE WALL, LEFT TO RIGHT

Rue de Fleurus, c. 1905. Photographer unknown. Facsimile. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 12, SFH.10. Left: Paul Cézanne, Group of Bathers, 1892 – 94. Second from left: Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock print, artist unidentified. Far right: Paul Gauguin, Three Tahitian Women against a Yellow Background, 1899.

Rue de Fleurus, c. 1906. Photographer unknown. Facsimile. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 12, SFH.22. Top: Henri Matisse, Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life), 1905 – 06. Bottom center: Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne with a Fan, 1878 – 88.

Rue de Fleurus, c. 1905. Photographer unknown. Facsimile. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 12, SFH.16. Center: Pierre Bonnard, Siesta, 1900. Right, at corner: Pablo Picasso, Girl with a Basket of Flowers, c. 1905.

Rue de Fleurus, c. 1906. Photographer unknown. Facsimile. Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 12, SFH.18. Left of stove: Pablo Picasso, The Milk Bottle, 1905. Right of stove: Japanese print of a mountain scene, artist unidentified. Lower right corner: Unidentified pre-Columbian textile.

Rue de Fleurus, undated. Photographer unknown. Facsimile Archives and Manuscripts Collections, Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Box 27, Folder 12, SFH.21. Top left: Pablo Picasso, Nude with Joined Hands, 1906. Top center: Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, 1905 – 06. Bottom center: Henri Matisse, Woman with a Hat, 1905. Bottom right: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Girl in Gray Blue, c. 1889.

Man Ray, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, 1922. Facsimile of a gelatin silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, © Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP. Above Alice: Paul Cézanne, Bathers, 1898 – 1900. Above Gertrude: Paul Cézanne, Madame Cézanne with a Fan, 1878 – 88, and Pablo Picasso, The Architect’s Table, 1912.

Identifications aided by The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Edited by Janet Bishop, Cécile Debray, and Rebecca Rabinow. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Yale University Press, 2011.

PUBLIC REFLECTIONS

75. Two of Robert A. Wilson’s Gertrude Stein scrapbooks.

76. “Portrait of Jo Davidson,” by Gertrude Stein. Vanity Fair, February 1923.

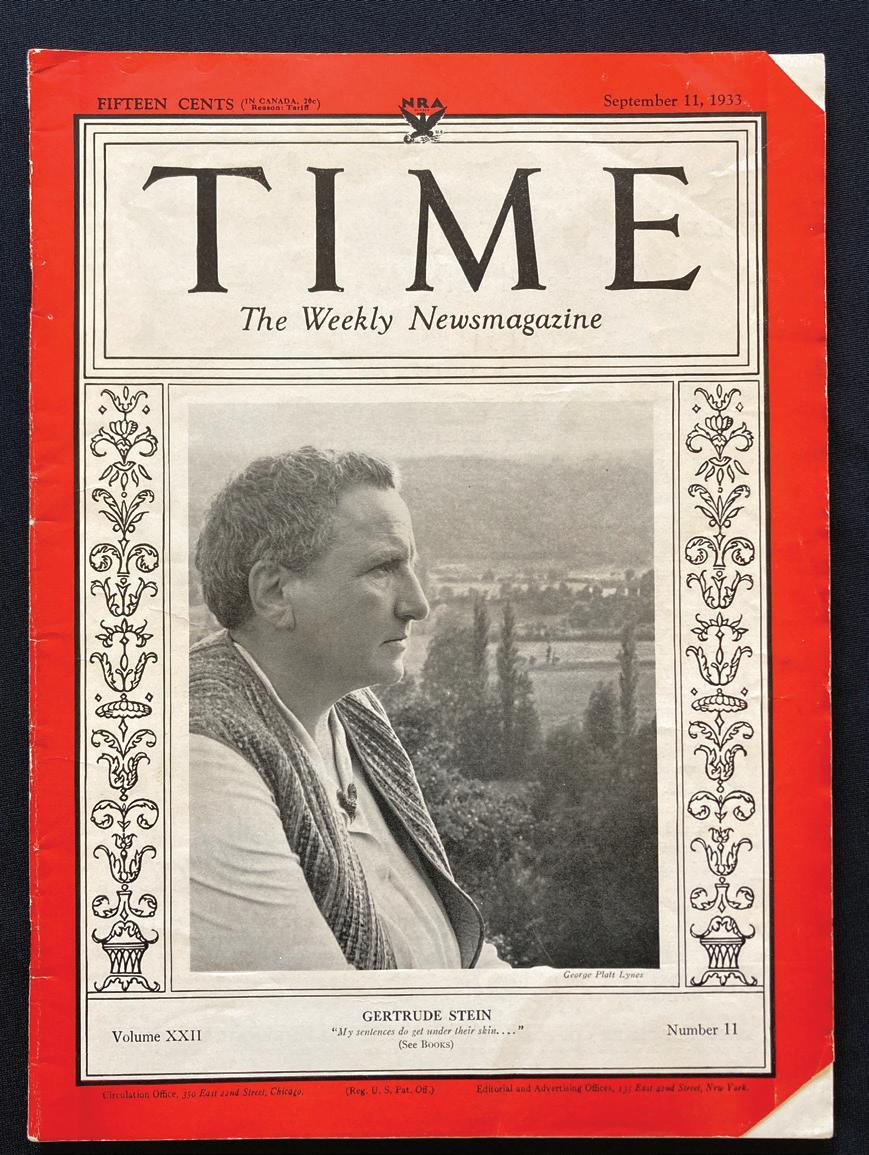

77. “Stein’s Way,” cover photograph by Carl Van Vechten. Time, September 11, 1933.

78. “They Who Came to Write,” by Alice B. Toklas. The New York Times Book Review, August 6, 1950.

79. Two original drawings for The Gertrude Stein First Reader and Three Plays, by Francis Rose.

80. The Gertrude Stein First Reader and Three Plays, by Gertrude Stein, illustrations by Francis Rose. Dublin; London: Maurice Fridberg, 1946. Inscribed by Francis Rose.

81. Paris France, by Gertrude Stein, with cover design by Francis Rose. London: B.T. Batsford, 1940. Inscribed by Stein.

82. Paris France, by Gertrude Stein, translated by May Tagnard, Baronne d’Aiguy. Alger: E. Charlot, 1941. Inscribed by Stein.

83. Wars I Have Seen, by Gertrude Stein, New York: Random House, 1945.

84. “Off We All Went to See Germany,” by Gertrude Stein. Life, August 6, 1945.

85. Brewsie and Willie, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Random House, 1946. Inscribed by Katherine Anne Porter.

86. Four in America, by Gertrude Stein. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947. Inscribed by Thornton Wilder.

87. Paroles aux Français. Messages et écrits 1934 – 1941, by Philippe Pétain. Lyon: Lardanchet, 1941. SLSC.

88. Publication announcement for The Mother of Us All libretto and score. New York: Music Press, 1947.

89. Flier for The Mother of Us All, Center Opera Company of Minneapolis. Hunter College Assembly Hall, New York, 1971.

90. Playbill for The Mother of Us All. St. Peter’s Church, New York, 1971.

91. The Mother of Us All LP, Santa Fe Opera. New World Records, 1977.

92. London production of Yes Is For a Very Young Man, by Gertrude Stein. Photograph by John Vickers, 1948.

93. Announcement for Gertrude Stein’s Gertrude Stein, a one-woman show by Nancy Cole. Gotham Book Mart, February 9, 1971.

94. Announcement for marathon reading of Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans, Paula Cooper Gallery, December 31, 1977 – January 2, 1978.

95. Flier for Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, by Gertrude Stein. Hand Over Mouth Theater, St. Peter’s Church, n.d.

96. Postcard for 27 rue de Fleurus, book and lyrics by Ted Sod, music and lyrics by Lisa Koch. UrbanStages, March 1 – April 6, 2008.

97. Gertrude Stein Reads from her Works LP. Caedmon, 1956 (1934 – 35).

98. Deux Soeurs Qui Ne Sont Pas Soeurs (Two Sisters Not Sisters), music by Virgil Thomson, text by Gertrude Stein. Southern Music Publishing, 1981.

99. Three Songs, music by John Cage, text by Gertrude Stein. New York: Henmar Press, 1991.

100. Robert A. Wilson’s Gertrude Stein pillow. Creator unknown, n.d.

101. Gertrude Stein doll, by Victoria and Vitaliy, MyBestBanner Celebrity Dolls, c. 2023.

102. Gertrude Stein watch. Creator unknown, n.d.

103. Gertrude Stein playing cards and fact cards, various publishers, 1970s – 2010s.

104. Paris France, by Gertrude Stein. Braille edition, Volume 1, publisher and date unknown.

105. One of Robert A. Wilson’s Gertrude Stein scrapbooks.

106. Typescript of “One Has Not Lost One’s Marguerite,” by Gertrude Stein. Signed by Stein. Black and Blue Jay Magazine, April 1926, with Gertrude Stein’s “One Has Not Lost One’s Marguerite.” Ferdinand Hamburger University Archives, SLSC.

ON THE WALL, LEFT TO RIGHT

Exhibition announcement for Man Ray’s Paris Portraits: 1921 – 39, with Gertrude Stein, Photograph by Man Ray, 1925 – 26. The Mayor Gallery, London, 2001.

Gertrude Stein, from Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century. Print from a portfolio based on cycle of paintings by Andy Warhol, 1980.

Reproduction of Gertrude Stein, portrait by Pablo Picasso, 1905 – 06, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in an unidentified Spanish magazine, c. 1966.

Exhibition catalog for Gertrude Stein and Her Friends, C.W. Post Center Art Gallery, Long Island University, New York, and Canton Art Institute, Canton, Ohio, 1975. With cover photograph of Gertrude Stein, by Jacques Lipchitz, 1920.

Stein. Poster by Atelier Bagatelle, New Orleans, c. 2023.

Poster for Quatre Saints en Trois Actes, American National Theatre and Academy, Théâtre de Champs Elysées, Paris, c. June 1952.

Poster for Gertrude Stein’s Made by Two, Theatre Express, LaMama, New York, 1980. Poster design by T. Hachtman.

Gertrude Stein, Plate 5 from Père Lachaise. Etching by Francis Wishart, 1978.

Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose. Poster by Evan and Nichole Robertson, Obvious State Studio, Van Nuys CA, c. 2023.

Mothergoose of Montparnasse LP, Gertrude Stein selections read by Addison Metcalf. Poet’s Theatre Series, directed by Martin Donegan. Folkways Records, 1965. Inscribed by Metcalf to Robert A. Wilson.

Portrait of Gertrude Stein. Photograph by Sophie Delar, c. 1934.

Gertrude Stein by hitching post, Richmond VA. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, 1935.

Profile portrait of Gertrude Stein. Photograph by Carl Van Vechten, c. 1937.

QUEER COMMUNITIES

107. Letter to Julian Sawyer from Alice B. Toklas, September 15, 1946.

108. The Alice B Toklas Cookbook, by Alice B Toklas, illustrations by Francis Rose. London: Michael Joseph, 1954.

109. Typescript of What is Remembered, by Alice B Toklas.

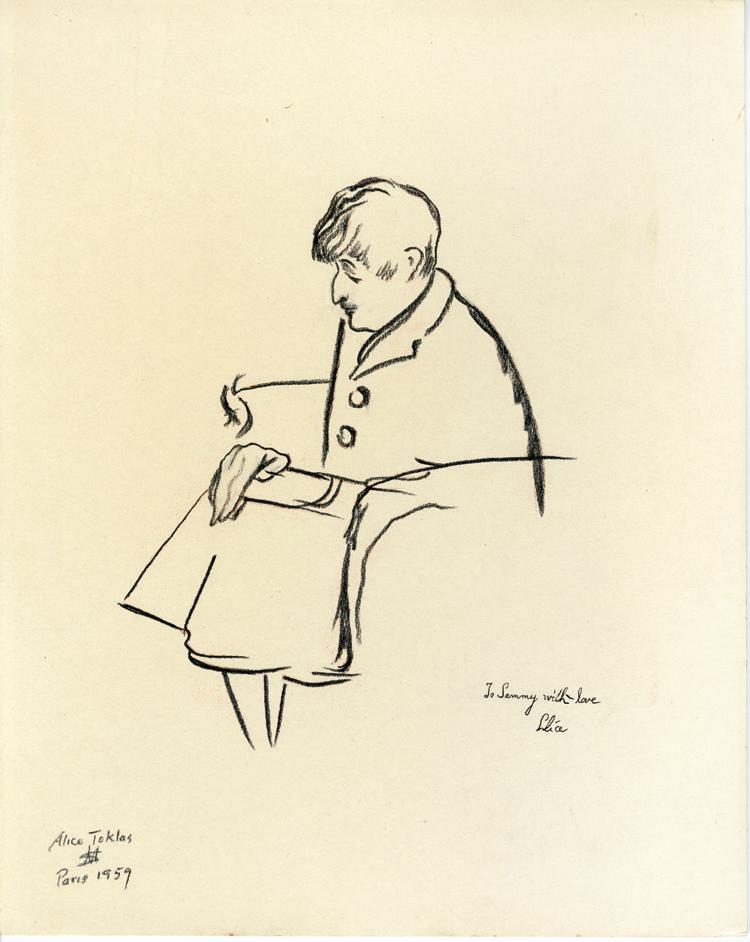

110. Self-portrait, by Alice B. Toklas. Paris, 1959, inscribed to Sammy Steward.

111. Alice Toklas with Sylvia Beach and Thornton Wilder. Photographer unknown, c. 1960.

112. Letter to Allan Tanner from Gertrude Stein, June 22, 1925, with postcard to Allan Tanner from Gertrude Stein, June 1926.

113. Letter to Paul Bowles from Gertrude Stein, postmarked 1931, with photographs of Paul Bowles, Aaron Copland, and Basket the poodle.

114. Proof copy of Operas and Plays, by Gertrude Stein, with postcards to Paul Bowles, c. 1931.

115. Manuscript of birthday poem to Sammy Steward, by Gertrude Stein. Bilignin, 1939.

116. “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,” by Gertrude Stein, originally published in Geography and Plays, 1922. Vanity Fair, July 1923.

117. Things as They Are: A Novel in Three Parts, by Gertrude Stein. Pawlet VT: Banyan Press, 1950.

118. Fernhurst, Q.E.D. and Other Early Writings, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Liveright, 1971.

119. 証明おわりShoumei Owari [Q.E.D.] by Gertrude Stein, translated by Masao Shimura. Tōkyō: Shoshi Yamada, 1984.

120. Review of Things As They Are, by Gertrude Stein. The Ladder, June 1957. SLSC.

121. “On Gertrude Stein,” by A. E. Smith. One Institute Quarterly: Homophile Studies, summer 1959. SLSC.

122. “Gertrude and Alice,” by Alan Jacobs. Vector, August 1971. SLSC.

123. Lesbian Images: Gertrude Stein, Colette, Willa Cather, Elizabeth Bowen, and Others, by Jane Rule. Garden City NJ: Pocket Books, 1976. SLSC.

124. Flier for Nightshift, by Scrumbly Koldewyn and Martin Worman. San Francisco: Bay Area Committee Against the Briggs Initiative, 1978. SLSC.

125. The Caravaggio Shawl, by Sammy Steward. Boston: Alyson Publications, 1989.

126. Gertrude Stein, with other zines in the series The Life and Times of Butch Dykes, by Eloisa Aquino. B & D Press, 2010. SLSC.

127. “Pat Bond: Role(Playing) Gertrude Stein,” interview with Michael Lynch and Mariana Valverde. BodyPolitic: A Magazine for Gay Liberation, December 1979/January 1980. SLSC.

128. Evalyn Parry and Anna Chatterton in Gertrude and Alice, by Evalyn Parry and Anna Chatterton, with Karin Randoja, Independent Aunties at Buddies in Bad Times Theater, Toronto. Photograph by Jeremy Mimnaugh, c. 2016. Facsimile.

129. Gertrude and Alice t-shirt, by Timothy Hull. TimoteoTees, c. 2023. SLSC.

130. Gertrude, Alice, and Basket mug, with photograph by Carl Mydans, originally published in Life, September 1944. academicink, c. 2023. SLSC.

131. Stein stein, by Fitz & Floyd. Made in Japan, 1976.

eluded her, Stein was suddenly a new kind of author, appearing in the stately Atlantic magazine and several illustrated book editions. The book led to a lecture tour in the United States — her first visit in thirty years — and a sequel, Everybody’s Autobiography (1937).

The experience also revived Stein’s interest in collaboration. When the young composer Virgil Thomson proposed a partnership, she embraced the task of writing the libretto for his opera Four Saints in Three Acts. The production opened in 1934 to great acclaim, with a record-breaking run for an opera on Broadway. It was performed entirely by African American singers, a casting decision Thomson made after hearing the cabaret entertainer Jimmie Daniels sing at a club in Harlem. This choice was partly a product of “Harlem-mania,” the greedy attraction of white artists and carousers to the creativity of the Black metropolis. But it also reflected Thomson’s sincere appreciation for African American vocal training. The casting provided a much-needed platform for Black talent, usually confined to a

Detail of Stein’s stationery, from letter to Marcelle Ferry, December 8, 1930. Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1933.

Flier for premiere of Four Saints in Three Acts at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, February 1934.

very narrow niche on segregated American stages, and connected with the Harlem Renaissance, another landmark modernist network, through the participation of choral director Eva Jessye.

PUBLIC REFLECTIONS

Early in Stein’s career, the book reviewers and culture columnists of American newspapers sized up her work and weren’t sure what to make of it. Her trademark repetitions, odd grammar, and refusal of the usual rules of storytelling led some critics and readers to regard her as a bohemian mystic or charlatan, although she also attracted a few genuine fans.

But in the 1930s, Stein’s reputation changed. Readers made The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas a best-seller and packed the halls where Stein, on her American book tour, delivered lectures with wit and unexpected common sense. She acquired new prestige as an eccentric but charming personality. Although she kept on creating work in her high style, notably the long poem Stanzas in Meditation — printed and reprinted in bits and pieces but not published in its entirety until 1956 — she also continued to produce the more plainspoken work that most readers preferred, particularly in response to World War II.

In September 1939, Stein and Toklas fled Paris for a small village near the French Alps where they had spent summers since the mid 1920s. The hasty packing of their art collection is represented on the cover of Stein’s love letter to her adopted hometown, Paris France (1940), in a design by the artist Francis Rose. The two women and the paintings they left behind were protected by their friend Bernard Faÿ, who had assumed an import-

“Stein’s Way,” cover photograph by Carl Van Vechten. Time, September 11, 1933.

Wars I Have Seen, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Random House, 1945.

ant post within the Vichy regime, the Nazi-led government of France headed by Philippe Pétain.

Stein’s memoir of these years, Wars I Have Seen (1945), chronicles day-to-day life in a corner of the treacherous “free zone.” It celebrates the fortitude of the French and rebukes the Germans. With its plural “wars,” the book’s title invokes not just the Second but also the First World War, during which Pétain, a victorious army officer, assumed the position of Commander-in-Chief. It might have been Stein’s naïve confidence in the Pétain of World War I that led her to accept Faÿ’s proposal that she translate into English a volume of Pétain’s speeches, for which she also wrote a flattering introduction. She was a Jewish-American lesbian creator and collector of what the Third Reich called “decadent art,” simultaneously writing a memoir critical of the Nazis. But she was also constitutionally conservative, attracted to the type of orderly society that fascism idealized. Did Stein genuinely admire Pétain as a “savior” of France? Or did she feel that the translation project might provide protection in a profoundly uncertain future? She abandoned the translation in 1942. Scholars continue to debate its meaning.

After the war, Stein achieved the status of a public figure. Her books, aimed at a general readership, were published by Random House, a press with commercial ambitions and literary credibility. Brewsie and Willie (1946) paid homage to the socially perceptive and philosophical conversations of the American G.I.’s who visited after her return to Paris — soldiers who made her feel “all over patriotic,” she said.4 Four in America (1947) was similarly oriented to the U.S., with fictitious biographies of four of her favorite historical Americans, George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry James, and Wilbur Wright. In contrast to

these masculine heroes was Stein’s last work, the libretto for The Mother of Us All, a second opera collaboration with Virgil Thomson first performed in 1947, about the nineteenth-century suffragist Susan B. Anthony. Stein had never had much to say about the suffrage movement or women’s rights, but her knotty writing had always served as a challenge to what she once called “patriarchal poetry.”5 This revolution in subject-matter at the very end of life was perhaps not so remarkable.

Stein died in July 1946 after a painful battle with cancer. “What is the answer?” she asked, just before the operation that failed to save her. And then, when Toklas did not respond, “In that case, what is the question?”6 These last words — opening up an existential conversation she would not live to continue — have served as a sort of invitation to the many artists, writers, and political activists who, since her death, have put themselves in dialogue with her writing and biography.

We who read and value Stein now have inherited a body of work that extends far beyond that which was published in her lifetime. The Mother of Us All has been restaged and recorded several times, often at moments when its political themes are especially relevant. The Gertrude Stein First Reader and Three Plays (1946), with illustrations by Francis Rose, established a tradition of Stein anthologies assembled to make her thorny texts more accessible. A project that Stein greatly cherished — what she imagined as the goal of her own Plain Edition — was finally launched in 1951 under the direction of Van Vechten: The Yale Edition of the Unpublished Writings of Gertrude Stein, drawn from the papers and books Stein had deposited at Yale University before the war. It eventually comprised eight volumes.

Posthumous publications like the Yale Edition brought Stein’s writing to the attention of the next generation. Artists, writers, composers, and theater groups of the post-war avant-garde embraced Stein’s “nonsense,” finding in her texts an apt channel for the paradoxical atmosphere of the Cold War in the West: exuberant consumerism coupled with deep, pervasive anxiety. Some developed new productions and adaptations of her work. Others created original works — fiction, poetry, plays, music, visual art — inspired by hers.

At the same time, many of the texts Stein herself saw through the press, usually in small editions, were long out of print and hard to find. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm of avant-garde artists was not matched by the literary establishment. Once again, Stein was up against the other modernist writers of her generation — white male authors like James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and T. S. Eliot were seen by scholars as the important emissaries of the period. Their works, not hers, merited serious study. Their works, not hers, were published in new editions.

And this is where collectors came to the rescue.

Under the diligent care of its curator, Donald Gallup, the Yale collection made room for Steinrelated books, letters, and other materials that old friends and dedicated readers could donate. Other Stein fans, like Robert A. Wilson, started their own collections. Several of these upstart collectors were gay men like Wilson who saw in Stein not just a literary titan but a courageous example of queer life lived on one’s own terms. Hunting down copies of her books, preserving Stein-related newspaper articles and photographs, publishing bibliographies, organizing exhibitions of their collections, Wilson and his fellow-collectors laid the groundwork for an explosion of interest in

Publication announcement for The Mother of Us All libretto and score. New York: Music Press, 1947.

Stein stein, by Fitz & Floyd. Made in Japan, 1976.

Stein in the 1970s — and made it possible for Stein to play a significant role in the new academic fields of feminist criticism and LGBTQ+ studies. By the late twentieth century, Stein had come to occupy an unusual position in American literary history. Adored as a queer foremother and sage patron of modern art, her many popular representations as an iconic author undoubtedly outweighed the extent to which she was actually read.

QUEER COMMUNITIES

Gertrude Stein never came out of the closet. Any public announcement about her sexuality would have put her in the cross-hairs of antisodomy laws in the United States. Even in France, where homosexuality had been decriminalized in the eighteenth century, openness on this matter would have endangered her already limited ability to participate in the literary marketplace. On the other hand, it’s possible to argue that she was never in the closet to begin with. She and Toklas didn’t explain themselves; some people understood who they were to each other, and some people didn’t. Toklas gave Stein a Julius Caesar-style haircut in 1926, and she loved it. Her cropped hair, along with her straight tweed skirts and embroidered vests, was a crystal clear signal of a non-conformist gender identity.

Not surprisingly, the community that gathered around Stein and Toklas in Paris included many others who rejected normative heterosexuality and strictly binary gender roles. Exchanges of letters, photographs, books, and poems with young male friends and protégés who were gay or bisexual, like Paul Bowles, Sammy Steward, and Allan Tanner, for example, show an ease and comfort that speak of chosen family.

Self-portrait, by Alice B. Toklas. Paris, 1959, inscribed to Sammy Steward. Paul Bowles and Aaron Copland, photographer unknown, July 1931. Enclosed with letter to Paul Bowles from Gertrude Stein.

After Stein’s death, Toklas took on the work of organizing Stein’s literary papers for the Yale collection. In this process, she discovered the manuscript for Q.E.D., Stein’s first attempt to write the story of the love triangle that had so distressed her at the turn of the century. With the encouragement of Van Vechten, Stein’s literary executor, Toklas made the courageous decision to have it published as Things as They Are (1950). Q. E. D. is an abbreviation for the Latin phrase “quod erat demonstrandum,” which means “that which was to be demonstrated,” an acronym traditionally placed at the end of a mathematical proof. Stein’s title indicated that a happy ending had never been possible, that the romantic impasse had played out exactly as expected — but not because she, her beloved, and her adversary were all women. Rather, it was

the conflict between incompatible personalities that had doomed Stein’s chances. Ironically, the publication of this story of disappointed lesbian courtship — an anti-romance if there ever was one — nourished the emerging movement for LGBTQ+ rights. It was reviewed in The Ladder, the publication of the first lesbian civil rights organization in the United States; new editions and translations rolled out in the 1970s and 1980s.

Stein and Toklas as a couple were increasingly seen as a different kind of proof: incontrovertible evidence that lives lived with dignity and love were possible for queer people — even, as laws and policies progressed towards equality, lives lived with candor and pride. The unofficial but very real marriage of Stein and Toklas was recognized and celebrated. They popped up often in the growing LGBTQ+ media ecosystem: local newspapers, national magazines, and books oriented explicitly to queer readerships. Their likenesses appeared on t-shirts, mugs, and calendars. And, starring as themselves, they were featured in new and openly queer works of art.

Above, left to right: The Ladder, June 1957, with review of Things

As They Are, by Gertrude Stein.

Fernhurst, Q.E.D. and Other Early Writings, by Gertrude Stein. New York: Liveright, 1971.

Gertrude Stein, with other zines in the series The Life and Times of Butch Dykes, by Eloisa Aquino. B & D Press, 2010.

Toklas died in 1967, two years before the uprising at the Stonewall Inn in New York City that sparked the modern phase of the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Did she ever suspect that she and Stein would become queer heroes? For twenty years after Stein’s death, Toklas faithfully maintained the role she had chosen in their relationship, centering Stein’s literary accomplishments and modernist foresight. She spiced up her bestselling Alice B. Toklas Cookbook (1954) with droll anecdotes about the famous artists and writers they had known. Even her memoir, What Is Remembered (1963) — her own genuine memoir, at last — was deliberately designed to bolster Stein’s reputation. Now, however, Toklas is increasingly seen in her true light: as Stein’s career partner as well as her partner in life.

Alice Toklas and Gertrude Stein created a queer community unto themselves, a circle of two devoted to Stein’s talent and ambition. Their marriage, conventional in many ways, enabled the absolutely unconventional work of a writer who carved out some of modernism’s most provocative and productive circles — spheres of life and writing that continue to nourish our collective imagination.

1. Stein, Everybody’s Autobiography (Random House, 1937), 242.

2. Stein, The Making of Americans (Dalkey Archive Press, 1995 [1925]), 136.

3. Stein, “Sacred Emily,” in Geography and Plays (Dover Publications, 1999 [1922]), 178 – 88. Explanation from Thornton Wilder citing Stein in his Introduction to Four in America (Books for Libraries, 1969 [1947]), vi.

4. Stein, “To Americans,” in Brewsie and Willie (Random House, 1946), 113.

5. Stein, “Patriarchal Poetry,” in Bee Time Vine and Other Pieces, 1913 – 1927, edited by Virgil Thomson (Yale University Press, 1953), 254 – 94.

6. Toklas, What Is Remembered (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1963), 173.

Major support for this exhibition and accompanying publication and programming is provided by the Friends of the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries. To become a Friend, visit LIBRARY.JHU.EDU/GIVING/

EXHIBITION CREDITS

CURATOR

Gabrielle Dean, PhD, William Kurrelmeyer Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

INSTALLATION AND PROGRAMMING

Sam Bessen, Eleanor and Lester Levy Family Curator of Sheet Music and Popular Culture

Paul Espinosa, Curator, George Peabody Library

Jennifer Jarvis, Paper Conservator

Mark Pollei, Joseph Ruzicka and Marie Ruzicka Feldmann Director of Conservation and Preservation

Alessandro Scola, Senior Book Conservator

Lena Warren, Book Conservator

GRAPHIC DESIGN

L Pupa Design

SPECIAL THANKS to Jenelle Clark, Kristen Diehl, and Amy Kimball, Sheridan Libraries; Sarah Dansberger, Baltimore Museum of Art; Michael Seminara, Institute for the History of Medicine; and Andy Harrison, Terri Hatfield, Nancy McCall, and Timothy Wisniewski, Alan Mason Chesney Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

The extensive ROBERT A. WILSON COLLECTION OF GERTRUDE STEIN MATERIALS at the Sheridan Libraries includes first and significant later editions of Stein’s books, many of them inscribed; books related to and about her; periodicals; letters; photographs; LPs; manuscripts and proofs. It is especially rich in materials that illustrate Stein’s legacy: souvenir objects, brochures, fliers, posters, and sheet music that document interpretations of Stein’s texts and works inspired by hers.

Learn more about the collection here: LIBRARY.JHU.EDU/GERTRUDE-STEIN/