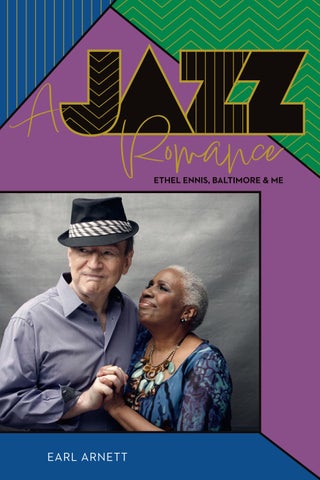

Romance A EARL ARNETT

ETHEL ENNIS, BALTIMORE & ME

ARomance

A

Romance

ETHEL ENNIS, BALTIMORE & ME

EARL ARNETT

Copyright © 2025 by Earl

Arnett

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work in any form whatsoever, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief passages in connection with a review.

Published 2025 Baltimore, Maryland

Design by B. Creative Group

Printing by Black Classic Press Digital Printing

ISBN: 979-8-218-62097-4

Unless otherwise noted, all photos reproduced courtesy of the Ethel Ennis and Earl Arnett Collection, Department of Special Collections, Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries.

Cover photo © Dean Alexander, courtesy of Dean Alexander

To Mama Jeanne Arnett (1918–2021), who supported and encouraged Ethel and me throughout our fifty-one-year marriage

PREFACE

The idea for this book came from Ethel, who was always more intuitively wise than me. She felt that our story should be shared with a wider audience. I was initially skeptical. “Memoirs” were plentiful and egotistical, I thought, usually mere records of social accomplishment, interesting only to the author’s friends and professional historians. But then I considered myself as a reader, always interested in people and families. Because of our occupations, Ethel and I had moved fluidly up and down social ladders outside normal categories. Maybe, if I could write it well, our story would be interesting and useful. You have the result here and will be the judge. I began research in 2010, gradually realizing how little we know about ourselves. Even our memories are part fiction, and we seldom know the context in which we live. Most of life, even that small portion we personally experience, is an unfathomable mystery with hidden currents and energies. During the writing, I debated how personal this book should be. Should I include my father’s considered manifesto against “interracial” marriage? How private should I be in sharing my fifty-one-year partnership with Ethel? In my father’s case, the decision was easy. He had written for publication and still represents a sizable population who think his way. (We reached a pleasant rapprochement in his later years, although he never acknowledged he might be wrong.) In most other instances, I’ve followed personal details wherever they led. As Ethel sometimes joked, “You tell everything you know,” and she was right.

I stopped writing in 2017–18, the two years when Ethel suffered increasingly debilitative strokes, and took it up again after her death on February 17, 2019, as a form of grief therapy. Ethel never read the manuscript, but I think she would be pleased. We’ve shared our story with the world. Now it belongs to anyone who wants or needs it.

It was Philip Arnoult (1941–2024), a talented theatrical entrepreneur, who first persuaded Ethel and me that we possessed “archives” with cultural value. Through his intercession, we met Sylvia Eggleston Wehr (1940–2023), then associate dean of the Johns Hopkins University Sheridan Libraries, where we established an Ethel Ennis and Earl Arnett Collection. Ethel had received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from Hopkins in 2008, and we were pleased to have our accumulated papers and collections join the university’s archives. When Ethel died, Sylvia helped me arrange a private luncheon and public memorial concert at the Peabody Conservatory and she subsequently became a good friend and champion of this book, raising funds for its publication and to sustain me as its author.

Writing is a solitary enterprise, but a book represents community. Robbye Apperson made possible not only Ethel’s memorial luncheon but also the publication and launch of this book. I am grateful for her continuing commitment to sharing Ethel’s legacy and our story with Baltimore and the world.

Richard J. Stephenson, my fraternity brother and longtime friend, contributed generously through his family foundation, enabling me to consult on the processing of the archive and complete the manuscript.

I am also grateful to Philip Arnoult, Richard O. Berndt, Perry and Aurelia Bolton, Margaret Burri, Connie Caplan, Al De Salvo and Susan Thomson, Kenna Forsyth, Beth and Mark Felder, William P. Gillen, Walter and Penny Haney, Paul Hildner, Janet and William Pickett, Carl Streuver and Barbara Wilks, and Susan de Tournemier for their support.

Thank you to Robert J. Brugger, former history and regional books editor at the Johns Hopkins University Press, who volunteered to review and comment on the first draft of the manuscript, as did assorted friends

and family. Thanks to my copy editor, Megan Stolz Rogers, for her meticulous eye and to Kerry Skarda at B. Creative Group for her superb book design. Needless to say, any errors that remain are mine.

Thank you to the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries, especially Gabrielle Dean, William Kurrelmeyer curator of rare books and manuscripts, and Africana archivist Tonika Berkley and to Raynetta Wiggins-Jackson, curatorial fellow for Africana collections with the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts at Johns Hopkins. Their combined talents, efforts and enthusiasm resulted in the landmark exhibition, Ethel’s Place: Celebrating Ethel Ennis, Baltimore’s First Lady of Jazz, which ran October 22, 2023, through April 24, 2024, at the George Peabody Library, and for which I gladly served as a consultant. Thanks also to Dean Emeritus Winston Tabb, Dean Elisabeth Long, Associate Dean Beth Miller Ryan and Communications Director Heather Stalfort.

In the course of a narrative that spans more than five decades, many extraordinary people didn’t fit the story being told. With appreciation, here are a few not mentioned in the text: my sister Carole McMullen, her husband Rob and daughter Stacey; Stan Mosley and his remarkable family; friends Phil and Sandy Johnson, Burt Kummerow, Ruby Glover, Barbara Mann, Linda Emory, Nevitta Ruddy, Paul Iwancio, Nita Callaway, Russ Moss, Bob Adams and George Young; former Baltimore Sun colleagues Ike Rehert, Antero Pietila, Fred Rasmussen and Jacques Kelly; and Ethel’s Place employees Joe Kearns, Robert Ford, John Lankenau and Alexis Schofield.

What you will read here is not a family history or a memoir but rather a general map of two journeys that melded into one, told as truthfully and honestly as this author is capable.

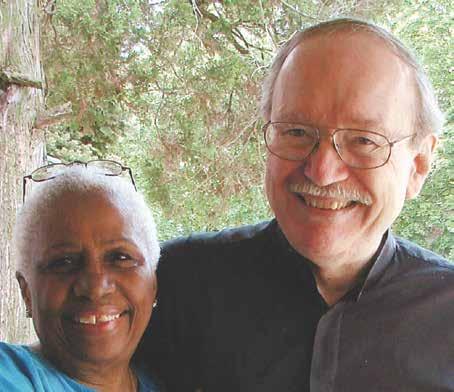

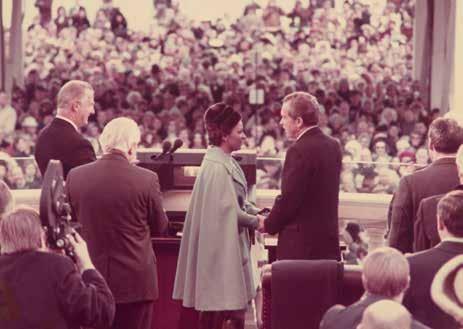

Exchanging vows, August 29, 1967

LOVE & MARRIAGE

In 1958, when I was a senior at Tokyo American High School–Narimasu, singer Ethel Ennis, newly married to a Baltimore attorney, toured Northern Europe with an all-star Benny Goodman band prior to concerts at the Brussels World’s Fair. I was white, a transplanted Hoosier born in Muncie, Indiana, and she was Black, born on the third floor of a Baltimore row house. If someone had told us that within nine years, we’d be married and spend the next fifty-one years together, we’d have said they were ridiculous. No way.

When Ethel divorced in 1965, she said she’d join a nunnery before remarrying, and I was a confirmed bachelor who considered marriage a possibility only after 40. But there we were on August 29, 1967, before a judge in Aspen, Colorado. The late Werner Kuster, then owner of the Red Onion Restaurant and Bar and now a member of the Aspen Hall of Fame, gave the bride away. The Joe Kloess Trio (Joe Kloess, piano; Paul Warburton, bass; Mike Buono, drums) served as witnesses. We walked beaming onto the courthouse steps, and that evening Ethel sang at the Onion, where she appeared twice a year. The day wasn’t that special since our real marriage and honeymoon had already occurred in Los Angeles a few months earlier when we spent three weeks together at the Sunset Doheny Motel while Ethel sang with Joe’s trio at the Hong Kong Bar (now defunct) in the Century Plaza Hotel.

That same year—1967—the US Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia invalidated the anti-miscegenation laws in sixteen states that prohibited our legal union;1 Maryland had just repealed its own 275-year-old law. Ethel’s parents weren’t particularly disturbed. Her mother, Arrabell Ennis, said, “I don’t mind you marrying a white man, but why ain’t he rich?” Her father, Andrew Ennis, a one-legged barber, shrugged his shoulders and said all men were brothers ’til proved otherwise.

My father, however, was another story. Clyde Arnett Sr., a retired Army lieutenant colonel, reluctantly searched his soul and composed a single-spaced, eleven-page typewritten manifesto that he first submitted to the Reader’s Digest. 2 He concluded that our marriage was wrong, and when the Digest didn’t publish his tome, he sent me a carbon copy with the concluding sentence, “We are not gaining a daughter, and we are losing a son.” I remember telling Ethel, “Oh, don’t worry about my family. We’ve lived all over the world and are used to having all kinds of people at our house.” She looked at me skeptically and said, “We’ll see.” My mother was quietly mortified, and my brother and sister were embarrassed by her husband’s attitude. I was genuinely surprised and replied that his reaction was his problem, not mine. I was in love.

How did this improbable, problematic romance begin? Our paths first converged when I came to Baltimore in late 1962 and saw Ethel sing at the Red Fox, a Baltimore landmark in the 1950s and early ’60s.

1 The term miscegenation for interracial marriages was invented in 1863 as a hoax to embarrass President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionists.

2 See Appendix A: Dad’s Letter

THE RED FOX & A FIRST MARRIAGE

In the summer of 1953, George “Foxie” Fox had walked down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Red Fox, his new bar and lounge at the corner of Fulton Avenue and Pennsylvania, to the Casino, where a young Ethel was playing piano and singing, accompanied by Montell “Monty” Poulson on the upright bass.

Foxie was a short, profane, coarse Jewish man who drank quarts of scotch, smoked cigars, and tipped the scale at about 300 pounds. He was also a New York refugee, a gambler who claimed he’d been a millionaire by the age of nineteen. When he had money, he spent it on women, booze, clothes, and the horses. He was also generous with the comedians and singers who hung around Broadway when their money was low. He specialized in college basketball games until, he claimed, the Mob forced him out of business. So Foxie packed his bags, held a party at Lindy’s where he bought the players free food and booze for the last time, and headed south for Baltimore, a slower moving town, to lay low. There he met Reba, a department store buyer; they got married, and his fast life slowed. In late 1952 or early 1953, to keep life interesting, he bought a liquor store and Rictor’s Red Fox Room at the top of Pennsylvania Avenue, the great entertainment and commercial center of Baltimore’s Black Belt. During the ’50s, it was among the few places in Baltimore where white and Black

people openly socialized in a sophisticated joint. Lou Bennett at the piano and organ was a fixture the first few years. Once in a while, someone like Miles Davis would walk through the door. The ponies at nearby Pimlico and “whoores” in Washington also kept Foxie entertained while he and Reba measured their bottles, counted receipts every night, and raised a family.

Foxie sometimes embarrassed his wife and her sisters with coarse, ribald stories told in the style of Myron Cohen, a favorite comedian. “How many pages in the Bible?” he asked my brother’s first wife, Sallie Weissinger, when they were introduced. “I don’t know,” she replied. “How many lives does a cat have?” he continued. “Nine,” she replied. “My Lord,” Foxie responded with a twinkling wink, “this girl knows more about pussy than the Bible.”

Foxie and Reba saw in Ethel “a Persian Room act”—she had a sophisticated voice that “sounded white” and a rhythmic sense that communicated “Black.” And she was “nice,” a protected church girl with lively good humor and a quick mind. Ethel and Poulson, supplemented by an assortment of other local musicians, soon became a mainstay at the Red Fox, center of a multicultural scene that included Johns Hopkins students, Avenue habitués, doctors, lawyers, steel workers, gay folks, teachers, soldiers and civil rights activists. Jazz music provided the catalyst, and the Red Fox became a “spot.” Ethel could play chords behind a bebop band, but her heart lay in church-based rhythm and blues, so the weekend crowds who jammed the small room at Pennsylvania and Fulton got a rich dosage of intelligent, rhythmic music that made them feel good. Jazz purists would tease Ethel about her pop songs and changes, but she just laughed. What good was music if people didn’t enjoy it? Besides, for her music was just a hobby that paid off.

Foxie enjoyed the crowds, but he also heard something special, particularly when Ethel hushed the room with warm, artful ballads. This was more than a local attraction, he thought. So he became her first manager on a handshake and began thinking on a larger scale. In the summer of 1955, he drove Ethel to New York and had her audition with four other singers for a two-week gig at the Patio, another cocktail lounge,

once classy and now long gone. She got the job, and the Red Fox arranged a send-off party for the “gate to stardom” that Foxie envisioned for his new protégée.

Ethel had visited New York City several times as a girl but was never enthralled by its fast rhythms, ambitious people and excitement. Her grandmother had sometimes called the shy girl a “ninny,” unadventurous and timid, but she preferred her own tempos, often slowed jumpy pop songs to ballads and kept her Baltimore pace—slower, more Southern, cautious. Her mother, who had never entered a nightclub until the Red Fox party, accompanied Ethel with Foxie and Reba to New York. Presumably, the gig went well. Foxie took her to see Dorothy Donegan perform, perhaps to illustrate how a woman at the piano could be outgoing, entertaining and exciting as well as a good musician. He arranged and paid for an all-day recording session on November 25 at the Bell Sound Studio with Hank Jones (piano), Kenny Clarke (drums), Albert Hall (bass) and Abie Baker (guitar). The result was the album Lullabies for Losers, released on Jubilee along with the singles “Off Shore” and “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.”

All but one of the songs was a ballad, and there were a few standards (“Blue Prelude,” “You Better Go Now”), but the rest were relatively unknown, including some she sang at the Red Fox. It was not an auspicious debut for jazz-infused tunes most people had never heard of. Charlie Parker died in 1955, signaling the decline of bebop; Elvis Presley and his new manager Col. Tom Parker were beginning to make a noise. Little Richard recorded “Tutti Frutti,” and Ray Charles had his first hit with “I Got a Woman.” In the South, Emmett Till was murdered and Rosa Parks refused to sit in the back of a bus. It was a beginning time for shoutin’ music, rock and roll, and protest.

Although Lullabies for Losers has since been re-released in many forms, Foxie never received any money from the Blaine brothers, who controlled the label. For the musicians, all of whom worked in the New York studios, the session was just another day’s work with an interesting new singer. Ethel continued to work in New York clubs like the Beau

Brummel and the Apollo Theater, coming home to work at the Red Fox or traveling to places like Pittsburgh and Syracuse. She and Foxie never had a formal contract; he watched over her like a father (in fact, she referred to him as her “Jewish father”), keeping aggressive libertines away, and she accepted what he paid her in cash. On one occasion, when a rich New Yorker offered Foxie $5,000 to sleep with his singer, he replied she wasn’t for sale. “Everyone’s for sale,” the playboy replied. “Not this one,” Foxie responded. “She’s not like that.” In return for such protection, Foxie had excuses to travel away from home, play the ponies, visit a few whorehouses and dabble in show business.

Still, the 1955 venture to New York and the Jubilee album must have drawn attention. The following year, Ray Ellis directed an orchestra for a single released by Atco, and in 1957, Capitol Records under Al Livingston signed her for a two-album deal. Producer Andy Wiswell hired top-flight arrangers to orchestrate a collection of Broadway-based standards that highlighted Ethel’s abilities to sing on key, clearly enunciate lyrics and swing—all qualities that were quickly going out of fashion. Ethel didn’t select the songs and, in many cases, had never heard them before arriving in the studio. She simply performed them to the best of her ability and then promptly forgot them.

All during this time, when she wasn’t traveling to the East Coast clubs or recording in New York, Ethel returned to Baltimore to perform at the Red Fox and live with her mother and brother in a small, nearby second-floor apartment on Whittier Avenue. They had had to move out of publicly subsidized Gilmor Homes because Ethel was making too much money. Ethel had already decided that New York wasn’t her cup of tea, and she had strong reservations about the show-business life. She didn’t mind performing on stage but disliked the schmoozing, striving and manipulating aspects of the music industry. When she asked her mother for advice, it came back as “get the money, honey.” Something had to give.

On November 23, 1957, after recording her first Capitol album with Neal Hefti, she married Jacques Leeds, a charismatic Baltimore attorney who had just divorced his second wife. The ceremonies were performed by

a minister in someone’s house; Ethel didn’t even recall where or who was there. Jacques was a Red Fox regular with flashes of brilliance that sustained his legal practice. He sometimes drank too much and occasionally beat his women. Ethel thought she married more to get away from her mother than to live in love with Jacques. He thought he was marrying a flashy entertainer rather than a church girl who stumbled into professional music. The young couple moved into an apartment on Druid Hill Avenue across from Union Baptist Church and tried to make it work. Ethel said he had a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality when they were together: brilliant and charismatic when sober, violent and jealous when drunk. When I occasionally drank too much, she would shake her head and wonder how she ended up with two crazy Hoosiers.

Born in Peru, Indiana, in 1927, Jacques came to Baltimore as a child, the offspring of a white father and Black mother. I heard colorful stories about his father, a merchant seaman who had apparently escaped from a chain gang and maintained two families—one white in Philadelphia and another Black in Baltimore. Jacques had graduated from the University of Maryland Law School in 1954, one of only three African Americans in his class. He was among the group of Baltimore lawyers who started making inroads against discrimination and segregation after World War II.3 He didn’t actively participate with other lawyers from the Baltimore-Washington region who pioneered civil rights cases in the 1950s and ’60s, but he performed a lot of pro bono work for poor folks who couldn’t afford legal services. His fourth and last wife, Polly Ware, recalled that “sometimes he was paid with chickens, corn or tomatoes.”

Always interested in politics and acknowledged by his peers as a smart attorney, Jacques did achieve a number of firsts. He was appointed assistant city solicitor and in 1962 became the first Black Maryland assistant attorney general. He later ran for state senator in a primary against Verda Welcome, and Ethel recalled stuffing envelopes and helping with the secretarial work

3 See Appendix D: Segregation, the Color Line & the Law

of the campaign, but then in some “backroom” deal, he withdrew his candidacy, and Welcome became the first Black woman to serve in the Maryland Senate.

Maybe his erratic behavior had something to do with his withdrawal from politics. Jacques was a sportsman who loved to hang out at clubs and racetracks with gamblers, boxers, hustlers and entertainers. More than once, he would disappear on binges while his law partners covered for him. He had charm, brains and talent but in those days wasted his gifts, much to the disgust of fellow attorneys who later became distinguished jurists. After his marriage to Polly, he seemed to become more serious and ended his legal career as a respected judge on the Maryland State Workers’ Compensation Commission. Jacques and I always got along but never became friends. We would occasionally see each other, and Ethel and I attended his retirement ceremonies in 1997, where she described herself as “wife number 3.” He died in 2018 at the age of 90.

However, in the spring of 1958, married only four months, Ethel was in New York recording Have You Forgotten?, her second album for Capitol, arranged and conducted by Sid Feller. “Popsie” Randolph, a photographer and Benny Goodman’s band boy, was around and happened to mention that Goodman was auditioning for a female singer to accompany an all-star band booked to tour Northern Europe before appearing at the Brussels World’s Fair. Ethel showed up at the audition site, sat at the piano and sang “I’ll Take Romance.”

Goodman smiled, and that was that. She returned to Baltimore, thinking no more about it; life was complicated enough. She was trying to be a lawyer’s wife, keep house, cook, sing, commute to New York for recording sessions and live with a tempestuous man. Jacques had already changed her professional relationship with Foxie and seemed to resent the attention she received. But a few weeks later, Goodman called and asked her to start rehearsals.

Suddenly Ethel was in the national spotlight, the newest Goodman singer in a line that included Helen Ward, Martha Tilton, Helen Forrest, Peggy Lee and Billie Holiday. Ebony magazine came to Baltimore and did a

large photo spread before the band departed for Europe on May 3. They had rehearsed for three weeks in New York and would perform in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and the Netherlands before arriving in Brussels on May 25 for the fair. During the weeks of travel, twenty-five-year-old Ethel was the only female in a band that included such luminaries as Arvell Shaw, Roland Hanna, Billy Bauer, Roy Burns, Taft Jordan, Seldon Powell and Zoot Sims. Jimmy Rushing, the veteran blues singer known as “Mr. Five-By-Five,” acted as informal chaperone and father figure.

All the reviews were favorable, and when Ethel returned, Capitol released the second album. During a concert at Morgan State College in her hometown that summer, Louis Armstrong invited her onstage to sing with him. Ella Fitzgerald called Ethel her favorite young singer, and Billie Holiday telephoned from New York in the middle of the night to offer encouragement to “the new bitch from Baltimore.” What was the “new bitch” thinking?

Ethel said she wasn’t thinking of anything; she was simply going along with the flow. She continued to work at the Red Fox and tried to build a married life. Sometimes she showed up for work with a black eye. When an opportunity arrived to work for six months in New York at a club called the Toast, she took it—a dead-end job at a piano bar shared with another from 8:30 p.m. to 4 a.m., six days a week. On Mondays, she returned to Baltimore to iron her husband’s shirts and straighten up the apartment. Battered and bruised, she sometimes fantasized about murdering Jacques in his sleep, and her mother suggested going to a conjure woman in South Carolina to work roots to tame his demons.

Jacques and Foxie didn’t get along, so there was no longer a manager to look out for her interests, Jacques was jealous of her limited fame and Ethel wasn’t seeking success. The Capitol album didn’t sell enough to lead to others. Music had changed. Iran banned rock and roll in 1958 as a health hazard, but everyone else was rockin’. Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald still hit the pop charts, but Bill Haley and His Comets were flying. As one of Ethel’s biographers put it, “it was a case with nowhere to go and no commitment to getting there.”

So, Ethel took what some would call a hiatus. Unlike Billie Holiday, she didn’t have a victim’s addictive mentality; even Jacques couldn’t subjugate her the way he would have liked. She was not “his woman;” she belonged to herself despite the occasional battering. Eubie Blake, another Baltimorean, had often told local musicians that they should “swim in the big sea” of New York rather than float in “the gutters of Baltimore,” but Ethel had no career ambitions. If someone called her for a performance and it felt right, she packed her music bag with notepads of lyrics in shorthand and traveled. If not, she still sang weekends at the Red Fox and lived. She didn’t think she was happy, but her family remained in Baltimore. She had fans. She enjoyed cooking, TV soap operas, pinochle, animals, infants, fellow musicians and some of the assorted characters Jacques brought to their lives. She was cheerfully active, not entirely passive about a music career but reluctant to “go against her grain for gain.”4

That was the Ethel I saw sometime in late 1962, early 1963—gowned and sitting at a small piano on a cramped stage in the corner of a bar, belting rhythm and blues, pop tunes and slow ballads that quieted the weekend patrons. Usually, a bass player accompanied her, sometimes a drummer, guitarist, vibraphonist or even a guest singer. I was mesmerized and grateful to discover what the locals regarded as a cultural treasure, hidden in the bowels of a segregated city.

I was a new college graduate, a soldier just out of basic training and a private in the student battalion at the US Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird, Maryland—a twenty-two-year-old who knew nothing of Baltimore, the music business or Afro-American culture. One of the few Black soldiers there invited me to visit this great music club he’d heard of. It featured an extraordinary singer married to a local attorney who appeared there on weekends.

I had never been to Baltimore before. Born in Muncie, Indiana, in 1940 and subsequently an Army brat after my father enlisted in 1944, I had

4 Sallie Kravetz, Ethel Ennis, the Reluctant Jazz Star: An Illustrated Biography (Gateway Press), 1984.

lived and attended schools in suburban Virginia, California, Indiana, Austria and Japan before enrolling at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, my father’s alma mater. I graduated in June 1962 as a commencement speaker with no immediate prospects.

After my speech, a youthful appeal for new definitions of freedom, I recall standing underneath a tree near the college chapel. The dean, an Ivy-League-type with deep roots at Princeton, walked by and remarked, “Arnett, we would have liked to give you an award, but you didn’t fit any of our categories.” I had no advice or connections to the wider world beyond a letter my father had written from Okinawa the previous month. It was an unusually long, handwritten message from a man who usually bottled up his emotions and personal feelings. He wrote:

I’m enjoying my work here. I’m the chief of the Counterintelligence Department in the school. I teach and also supervise other instructors in my department. I teach officers from seven Southeast Asian countries. They all speak English with varying degrees of fluency, but they are very intelligent—very well-informed people. We get only the best officers from Vietnam, Thailand, Korea, Philippines, Taiwan, Indonesia, Japan, etc.

It’s a pleasure to instruct them or just to talk to them. It’s an odd sensation once in a while though. About two weeks ago I was sitting with a group of Thai colonels in a Chinese restaurant in Okinawa, eating Japanese food and talking about Italy in English. It occurred to me to wonder what a good Kentucky hillbilly was doing there.

We are accomplishing something here. We are making friends for the United States, and I feel myself a very distinct part of it because my students seem to like me. We are treating these people like brothers and like the equals that they are. This is something that the British and particularly the French did not do in this part of the world. These people recognize it and appreciate it. I’m perfectly frank with them. If I don’t know something, I just say so and go on from there. I eat with them and drink with them, so they confide in me and ask

my advice. We are good friends with no ulterior motive involved. We are turning out these trained friends as fast as possible, and they are going back to their countries and spreading the word. Americans are people and human and they’re here to help—not take something away from us. Believe me—America needs friends. The next war will start over here. So, lest I get carried away, I feel that I’m doing something worthwhile and I’m being repaid in more than money.

In the same letter, he also offered assistance to me, his first son, for whom he hoped much. If I wanted to fulfill my military obligation (the draft was still omnipresent for young men) and was interested in Army intelligence, I should travel to Fort Holabird soon and talk to a Major Taggart, who would set me straight.

What were my options? I had accepted a night job in a local plastics factory, a position that would enable me to continue thinking about “freedom” and write. I jumped into my used Studebaker, a departing gift from my parents before they moved to East Asia, and drove to Baltimore in much the same spirit as the young Miles Davis, who traveled from St. Louis to New York to find Charlie “Bird” Parker. For both of us Midwesterners, the journey was an opportunity and a danger. Miles finally found Bird, flew musically and became addicted to drugs. I found Major Taggart, joined the Army and discovered that I didn’t like the military. I remember marching next to a klutzy recruit in basic training and the sergeant shouting, “What you trying to be, shitbird, an individualist?” Yeah, I thought, that’s exactly what I’m trying to be!

Both my grandfathers had served in the Army, one in the Philippines and the other in France; both uncles had fought in the Pacific during World War II. Arnetts had fought in the American Revolution and the Civil War, so the military seemed engrained in my DNA. Major Taggart outlined a comprehensive plan: go to basic training and the Army Intelligence Center, then Officer Candidate School. After becoming an officer with enlisted experience, I could advance to further schooling and fast promotions. My father would retire as a lieutenant colonel, but everyone I contacted seemed

to agree that he should have been at least a full “bird colonel,” above the rank of lieutenant colonel, except for his stubborn, withdrawn personality. Major Taggart’s plan would almost certainly have made me a general officer. So I called my brother in Crawfordsville and asked him to take care of my meager belongings (mostly books), parked the Studebaker in a vacant lot outside the fort and boarded a train on June 11 for Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to begin basic training. For six weeks I sweltered in the summer heat as a lowly recruit and then made my way back to Baltimore for intelligence training. During this six-month period, I decided that Major Taggart’s plan wasn’t for me; I didn’t want to advance up the military ladder. Joseph Heller’s book Catch-22 had become our bible at the intelligence school, and I had adopted The Good Soldier Švejk’s view of the Army—any army—after Jaroslav Hašek’s 1930s satirical stories.5 When the promised slot at Officer Candidate School opened up, I refused it and decided to learn what I could during my three-year enlistment. I graduated first in my small class in March 1963 and was sent to Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, California, to work in civilian clothes from a field office as a special agent conducting personnel security investigations. I was in California when Ethel moved to 3113 Leighton Avenue with her brother on August 28, 1963, the day that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington.

5First published March 1921 in Czech as Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války, the entire collection of short stories has a 2005 edition in English, published by Penguin Classics and translated by Lumír Nahodil and Cecil Parrott.

EARL’S MILITARY, EXPATRIATE & EARLY NEWSPAPER YEARS

(1963–66)

For three years, I neither saw nor heard of Ethel Ennis. I had started listening to jazz in college after hearing Miles Davis’s album Sketches of Spain on a late-night radio station in Indianapolis. I had never heard such free but controlled expression of passion. It appealed to my repressed sexuality at an all-male college in much the same manner as flamenco guitars. I had met Dizzy Gillespie in my fraternity’s living room and danced to Duke Ellington’s music at a Panhellenic event, never realizing I would encounter them much later as an adult whose wife had sung with both. Perhaps the music had seeped into me before I even knew what it was: While I was in utero, my twenty-two-year-old mother, who then almost never went out by herself, attended an Ellington concert in Bloomington, Indiana. She had been captured by “Mood Indigo” just like the Englishmen who met him on his first European tour.

During my year in California, I shared an apartment with two roommates in San Pedro on a bluff above Cabrillo Beach. When not investigating and writing reports, we explored our surroundings. One roommate, John Madden, a forest ranger who’d been drafted, introduced me to the forests and mountains around the LA basin; the ocean was omnipresent. On my own I visited The Lighthouse nightclub in Hermosa Beach and haunted

small flamenco and mariachi bars. Gwinn Vivian, a drafted anthropologist/ archaeologist who worked out of our small office, introduced me to the magic of the Southwest, His wife, Pat, a talented printmaker and painter, accompanied us on majestic trips to Navajo country.

In the early ’60s, San Pedro, or “Peedro,” had a distinct multi-ethnic, semi-bohemian atmosphere, with small food and wine stores, cafés and assorted characters. It was a harbor town different from tonier nearby Palos Verdes and the Hollywood areas to the north. It gave me room to explore music, food, wine and literature during off-duty hours. I was content to serve out my Army years there and then head to the High Sierras to hike, fish, remove the frustrations of military life and figure out how to be a writer.

Then I received orders for Germany. My father suggested that I stop in Okinawa to visit the family beforehand, so I unpacked my military duds, sewed on sergeant stripes and found space-available flights to East Asia from Travis Air Force Base. The flight from Hawaii to Okinawa was filled with a combat-ready unit sitting at attention with rifles under the command of a young lieutenant who looked at my rumpled uniform with disdain.

Welcome back to the Army, I thought. My idyllic Southern California days were over.

It was my third trip to Japan, although in 1963 Okinawa technically was still under military occupation. I had lived in Tokyo as a high school senior and then returned for a summer in Kyushu after my freshman year in college. Now I was briefly part of the small community around the US Army Pacific Intelligence School, where American instructors taught their Asian counterparts in counterinsurgency and counterintelligence methods. This was only a few months after President John Kennedy’s assassination, and the new Johnson administration was desperately trying to figure out how to prevent the spread of communism in East Asia.

I had already argued differences between democracy and Marxism with students at the University of Tokyo and subscribed to Graham Greene’s cynicism in his 1955 book The Quiet American but listened intently as these military men engaged in friendly discussions about how to bring “freedom” to their countries. After three weeks, I re-donned the uniform and made my

way back 10,000 miles to Germany. I arrived in civilian clothes and was promptly informed to report in uniform, at least until they decided what to do with me. This was no longer the Counter Intelligence Corps in occupied Austria that I remembered as a boy.

The CIA and other agencies had taken over the heavy lifting. When I was assigned to a field office in Mainz, we mostly drank beer with the German police and occasionally performed minor security investigations. Since I spoke passable German, headquarters soon sent me as part of a small team to a war game in Bavaria. Our job as part of the occupation force was to locate the special forces units who parachuted into the rolling countryside and hid out until time to “attack” key targets. We rented cars, received currency and headed into the picturesque landscape to locate the bad guys and recruit “spies.”

In Kochel am See, I recruited a deputy mayor named Hans Demleitner, who also acted as a Hochzeitslader, a master of ceremonies for traditional Bavarian weddings where old songs are performed, jokes told and guests try to steal the bride. He knew everyone in the area and had served in a mountain unit on the Eastern Front in World War II, so he was an ideal “spy,” the best of several I developed over the course of the three-week exercise. We almost caught one “enemy” unit hiding in a farmer’s barn and in turn became a target. In Oberammergau, I had rented a room and tried to recruit the pretty daughter of the main hotel’s owner. He turned out to be the town’s most notorious anti-American and reported me to the German police, who also began searching for my suspicious character.

Fortunately, I had another room in Füssen, an ancient town near the Austrian border, and was able to avoid all pursuers. If the rest of my Army experience in Germany had been as interesting and challenging, who knows? I might even have been tempted to return to Major Taggart’s original plan for my military career. Unfortunately, everything after this initial experience was downhill.

I returned to Mainz in “civies” speaking better German and settled into an office routine limited by a sergeant’s pay. All went reasonably well until the Christmas holidays when I spontaneously decided to grow a

mustache. After all, I reasoned, we were “agents” who weren’t supposed to look like Americans. Right? Wrong, according to the new lieutenant colonel in Kaiserslautern, who had commanded truck companies before graduating from the US Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird. During a tour of field offices, he took one look and ordered me to shave it off.

I didn’t imagine I’d ever see him again and so blithely ignored the order. However, our paths crossed again a few months later, and I found myself back in uniform at attention in front of his desk where he gave me a direct order to eliminate the mustache. Then began a mental calculus: I only have a few months before my enlistment expires and I plan to be discharged in Germany. This man represents all the aspects of the military that I dislike and obviously doesn’t understand the intelligence game. I politely told him that my mustache was none of his business. Several of his Black officers had mustaches; why shouldn’t I?

I spent my last few months in the Army at the German headquarters in uniform as training sergeant with other assorted duties, including, ironically, reenlistment sergeant. The lieutenant colonel, who wanted to court-martial me, became a laughingstock, and I was a hero among the enlisted men.

On June 11, 1965, I walked out of headquarters a free man and moved into the Darmstädter Hof, a resort hotel in Rüdesheim am Rhein, inherited by Hedi O’Steen, pregnant wife of a former colleague for whom I sometimes bought items at the Post Exchange. Bill O’Steen was much more a spy than I. He had a romantic, manipulative mind and carried a monologue from Cyrano de Bergerac in his wallet. We were friends, and he offered me his hospitality.

Thus began my adventures as an expatriate. I had less than $1,000 in cash, a portable typewriter, a record player with about 100 LPs (Miles Davis, Oscar Peterson, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Big Bill Broonzy, Mozart and assorted others), twenty books, a backpack and sleeping bag, a few clothes and a mandolin I couldn’t play.

For three weeks I was a friend to Bill and the neurotic Hedi as they tried to operate the rundown hotel during the tourist season. Then my San

Pedro roommate John Madden, who had also been sent to Germany, arrived from Bonn with his American fiancée to pick me to witness their wedding in Switzerland. We spent a few days in Paris and then drove to Basel, where I observed the nuptials. When they went their separate way, I trained down to Gmunden in the Salzkammergut region of Austria to visit Fanni Schmitt, who had been my family’s cook and maid from 1950 to 1953. She had a small apartment in her brother’s 250-year-old farmhouse at the foot of the Traunstein on the Traunsee, a cold, deep mountain lake known for its swans. She wasn’t living there, so she invited me to stay as a guest of the family. At that time, her niece Margaret Schmitt, whom I had known as a boy, also lived there with her parents, husband and son. In the summer they rented rooms to English, Austrian and German tourists, especially from Munich and Vienna.

At the end of July, I received a telegram from Bill urgently requesting me to return to Rüdesheim to assist him. Hedi had given birth but had postpartum blues, and both needed help. I returned to a difficult situation, where I consoled Hedi, carried hotel guest bags, chased chambermaids and even briefly operated a small bar in the lobby. In the meantime, to make money, Bill sometimes worked as a contract employee for the CIA, running agents in and out of East Germany. Several weeks later, I had an argument with Hedi and was politely asked to leave. Once more, I packed my suitcase, visited a fraternity brother in Brakel and revisited the Rhineland before boarding a train on August 26 to return to Gmunden.

With very limited funds, I spent my days reading, swimming in the lake, writing in notebooks and plotting my next move. Did I want to be a permanent expatriate? How does one become a professional writer? What was I going to write? In early September, Evelyn Unsinger and her mother arrived at the Schmitts’ from Munich for their annual vacation. They were transplanted Berliners with a tragic family history, and we quickly became friends. Then I fell in love.

Evelyn was a thirty-year-old secretary, neat and efficient, who lived with her mother in a small apartment. Both had been traumatized by the Soviet occupation of Berlin; her mother had been forced to remove dead

bodies from the streets, and the question of rape lingered but was never spoken. Evelyn had been disappointed in love at age 26 but saw me as a Goldstück, a lucky charm, another chance for children and a life apart from her mother. It was a late summer romance—quick and intense. Perhaps too quick because by the time the Unsingers returned to Munich, we were talking of marriage and children.

Did they calculate the affair? What did I know? I was a naive twenty-five-year-old German-speaking American expatriate with vague ambitions to become a writer. Love and desire pushed me forward into an engagement party in Munich. I commuted regularly by train between that city and Gmunden while making plans for Evelyn to come to the United States in 1966. I finally left Gmunden on December 23 to spend Christmas and New Year’s in Munich, then traveled north to Bremerhaven to board the USNS General Simon B. Buckner, a troop ship headed to New York.

At the time, the Army provided free transportation back to the United States within a year of discharge in Europe. I was part of a small troop of civilians aboard the Buckner who occupied the lower levels along with the enlisted men. One of us was a poet found destitute on the streets of Copenhagen. Another, Fitzpatrick, was an amiable Irishman who spent six months a year crab fishing in Alaska and then caroused the next six months in Italy. He had gone broke in Monte Carlo and was unable to reach his fishing partner for funds.

As an officer’s dependent, I had sailed the Atlantic and Pacific on several military transport ships but was unprepared for enlisted troop life below decks. Using the large, common latrine in the bow on a tossing sea was surreal. But we laughed at the sergeants who had no control over us, suffered the discomforts of a winter Atlantic crossing, shared stories and arrived in New York City on February 2, 1966.

I immediately made my way to Baltimore, where my father served his last military assignment as chair of the tech department at the Army Intelligence School. My parents and sister were living in a modest apartment in nearby Dundalk, where I arrived with my mustache looking like an Austrian mountaineer. My mother did a five-second double take

before letting me in. Back in my own country, I faced a familiar question: “Where do I go from here?” This time I had a German fiancée and had persuaded myself to have children but had no idea how to support a family.

One Army buddy had written to me to stay away from America as long as I could. Gwinn and Pat Vivian offered the use of their Navajo hogan, built in rolling ranch country in east-central Arizona near the Zuni reservation. My father suggested that the new Office of Economic Opportunity, a centerpiece of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society,” was hiring.

Vic Powell, one of the few Wabash professors with whom I’d stayed in touch, wrote that if I were interested in newspapers, I should contact Peter Edson, a syndicated Washington columnist and Wabash trustee. This last option offered a path to writing, so I wrote the letter, enclosing several letters of recommendation. Edson replied that the Sun Newspapers were hiring and I should write his friend Price Day, the editor in chief. So I wrote a two-page letter, explaining how I would make a good newspaperman, and one day in March I received a phone call from Paul Banker, then the city editor, asking if I could come down for an interview. I put on my only blue suit and went downtown from Dundalk.

“What do you think you’ll be doing in ten years?” Banker asked.

“I’d like to do for the Sun what James Reston does for The New York Times,” I replied.

“That’s very ambitious,” Banker said.

“Ten years is a long time,” I said.

Then I took a perfunctory general information test, rewrote a three-paragraph story from the previous day’s issue and was offered a job.

The Baltimore Sun had just recovered from a bitter labor strike, and I was hired as one of the first non-union reporters allowed under the new contract. Naturally, this made me a subject of interest for members of the Newspaper Guild, including Arnold “Skip” Isaacs, a good reporter and union man. He and Richard Levine, who had just done a major exposé of the police department, worked on me to join. They taught me how to report.

The newspaper in those days was much like what Russell Baker described in his memoir The Good Times.6 Charles “Buck” Dorsey was the aloof managing editor who seemed to control all the Maryland strings from the governor’s office to the street corner. Clarence Caulfield, or “Caully” as everyone called him, and Bob McDowell were the assistant city editors. Scott Sullivan, who flaunted his Yale Phi Beta Kappa key, covered city hall. Tom Fenton, who later made a mark with CBS News, was the best dressed among a crew that ranged from boozy old timers with bottles in their desk drawer to young Ivy Leaguers on a quick upward path. I was the greenest among them.

The newsroom was one open space and filled with voices shouting instructions, arguing with the editor and rewrite men or calling for copy boys who grabbed sheets as they came off the typewriter. Tickers clattered in the background with news from the wire services. Deadlines produced intense periods of activity, when reporters proved their worth, followed by lulls between the news, which came sporadically and often unexpectedly. If it didn’t come, beat reporters created their own news by calling parties who disagreed or disliked each other. The new hires participated in a rotation system that included periods in the police districts and district courts, general assignments and writing obituaries. A man at police headquarters, usually Fred Hill at the time, coordinated our activities around the city. We called our police, fire and court news into rewrite men who created the story read in the next morning’s newspaper.

The most capable man in this system, who arrived a few months after me, was John Carroll, who would later become editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, the Sun and the Los Angeles Times. He had a newspaper background and knew instinctively what made a story. We district men got to know each other well as we traveled around the city, sometimes meeting for dinner to compare notes. We participated in a friendly competition to get off the rotation and acquire a real reporter’s job. Carroll had ink in his veins;

6 Russell Baker, The Good Times (New York, William Morrow & Company, 1989) (original edition).

I was still trying to understand the news world and wasn’t even sure I liked it. The Sun to me was a mysterious word factory run by men in the background who didn’t talk to young reporters. All was very laissez-faire; if you weren’t criticized, you must be doing OK. I remember once coming to work Sunday morning for general assignment. No one was in the newsroom, the machines were clacking and I had no clue what to do. A passing copy boy said that the reporters sometimes checked the wire services in case a big story developed. As I was floundering, Caulfield walked in and took pity on my situation. He gave me a few guidelines and shared a few memories—a nice man.

Not long after I started, the hierarchy shifted. Banker became the managing editor when Dorsey retired, and Sullivan took his place as city editor. We were never simpatico, and I began to look elsewhere for some kind of stimulation. The paper, I thought, was about as exciting as an insurance company. Since I was a police reporter, I thought I’d try to find something out about organized crime in the city; everyone was saying we didn’t have any and I didn’t believe it. A federal attorney told me that if I was serious, I should investigate Congressman Samuel Friedel’s facilitation of Teamster funds to local investors in Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Sounded interesting, so I asked my Sun editors if they would let me pursue the lead. They promptly closed the door; it was inconceivable, they said, that a respected Jewish congressional representative from Baltimore would have any connections to crime. So I never knew.

It was obvious—even to an inexperienced reporter—that the newspaper had no interest in political economy beyond a surface level. So I asked to be permanently assigned to the Western Police district, an unheard-of request from someone on the rotation. At least I might learn something and develop leads to stories worth writing. The city’s African American community had traditionally been underreported by the Sun. In addition, as a returned expatriate, I found Baltimore’s Black citizens generally more interesting than their white counterparts. The music was more vital, the heritage deeper and the people more fascinating than the white reporters knew.

Within a few months, it was obvious that marriage to Evelyn wouldn’t work. My passion, including the idea of fatherhood, had faded, and I still had no idea what I was doing. When I wrote her guiltily with the news, she replied coldly with a bill for our engagement dinner. I sent the money, and we never communicated again.

The other important character in this newspaper narrative is Martha Schoeps, who has unjustly been left out of Sun official histories. She began in the library and timidly worked her way under Dorsey to become editor of the “Women’s Page,” eventually to be expanded as a separate feature section. Schoeps was an overweight, mysterious spinster who hinted of a lost love and seldom mentioned her background, but she supported the arts as well as young writers. She was sensitive and kind, much different from most of the hard-bitten characters in the newsroom. I contributed several stories to her section and wrote a few articles about the jazz music I was hearing in small clubs after my police reporter’s hours ended. Schoeps was a friendly, supportive presence in the newsroom who had a feature writer’s slot on her small staff. Carroll called it the best job on the paper, but it was filled, and I was getting tired of the Sun, Baltimore and the East Coast. I told my editors that I would leave in the spring of 1967 and head west to visit my friends and their hogan in Arizona. By this time, my father had retired and the family had moved to Tucson, Arizona, so the West beckoned even more.

ETHEL’S MIDDLE GROUND YEARS (1963–66)

While I was pursuing my life as a soldier in California and Germany, Ethel’s life changed considerably since the time I had first seen her at the Red Fox. Her records for Jubilee and Capitol had produced some followers and supporters, who heard something quite distinctive in her voice, a blend of sensibilities unique to her. In one phrase she sounded like an English duchess with perfect diction and intonation;7 in another she tapped African American rhythms that white singers could only imitate. “If you were only Jewish,” some fans told her. She didn’t belong to anyone’s elite based on her background or education, but she sounded like fine cognac and champagne.

Ray Errol Fox (no relation to George Fox), an aspiring songwriter and showman from Philadelphia, first heard this voice on the radio when he was a freshman at Boston University and “flipped,” he said. While in law school in Philadelphia, he discovered he didn’t want to be a lawyer but was good at contracts and criminal law, qualities that might be useful in the music business. Ethel’s name came up in conversation, so when he left law school, in late 1962 or early 1963, he came down to Baltimore to hear her at the Red Fox and announced, “I want to manage you.”

7 Nellie Lutcher was surprised when she first met Ethel: “I thought you were an ofay chick,” she said.

“I was in my early twenties and have never managed anyone before or since,” he recalls. “But Jacques was very supportive. We drew up a contract and began a relationship that must have lasted at least a year, year and a half.”

Ray Fox used his Philly base to showcase his new client at radio stations and nightclubs, including one on City Line where she performed for weeks while staying at a local hotel. “I’ll always remember Jack Pyle introducing her there,” he recalls, referencing the Philadelphia radio pioneer. “He said there were five great female jazz singers in the United States. Ella Fitzgerald was first in her own category, and you could put the remaining four in any order: Sarah Vaughan, Carmen McRae, Edie Gormé and Ethel Ennis.”

Ray Fox’s aim was to get Ethel back in New York, the city she tolerated but never loved. He took Ethel and three other Baltimore musicians (including Jimmy Wells on vibes and Donald Bailey on bass) to a New York studio and sent the tapes to Andy Wiswell at RCA, the same A&R (artists and repertoire) man who had guided her as an artist at Capitol. He got an enthusiastic response and persuaded Wiswell to come hear Ethel live at the Latin Casino in New Jersey. Wiswell brought Gerry Purcell, a manager with strong contacts at RCA, and a relationship was forged. RCA would sign Ethel if she had capable, experienced management, so Ray Fox sold his contract to Purcell for a reasonable price, and in 1963, a new “career” began.

Following her grandmother’s advice, Ethel figured she might at least use this new opportunity and her failing marriage to buy some property, something tangible as a way of advancing in a segregated society. She bought the row house at 3113 Leighton Avenue, next door to one of Jacques’s long-standing girlfriends, named Bernice, at 3111. Fred Weisgal, a pioneering civil rights attorney and an outstanding amateur musician, had lived at 3111 for a few years in the 1950s, when the neighborhood was almost exclusively Jewish. Due to outrageous block-busting tactics, the neighborhood had become almost exclusively African American by 1963, and only a few scattered Jewish families remained. Bernice was an earthy,

fun-loving, light-skinned woman with her own family who had known Jacques since high school. She and Ethel were friendly, so the proximity worked—at least for a while. When she came home one evening and found Bernice with Jacques on her side of the bed, something had to give. Her first RCA album This is Ethel Ennis came out in the fall of 1963; she filed for divorce in 1964 and swore off marrying again.

In 1964, Ethel began feeling familiar doubts about show business. Ray Fox had catapulted her back into a New York–style career, just as George Fox had done in the 1950s, but the New York tempo bothered her. She was an emerging “new star” on an old, established label not known for promoting many Black artists. Purcell had placed her with the William Morris Agency, a premier talent agency run by Abe Lastfogel.

Purcell had a well-traveled formula for building a pop star that had succeeded with Eddy Arnold, his most successful client: Showcase at the right gatherings, work the media, book the right venues. He also had his own personal formula for breaking in female artists, suggesting to Ethel that a few weeks in his intimate company would eliminate whatever inhibitions prevented her from being a sexy singer. Ethel recorded two more albums in 1964, lavishly produced products with strings in the famous old RCA studios, but she resisted the other blandishments. What did she want with a connected Italian when she was getting rid of a more interesting African American?

Like any genuine artist, Ethel didn’t fit formulas and resisted categorization, but she tried to cooperate as much as possible. She realized the white folks were helping her, so she went along for the sake of a career until she felt that she was going “against my grain for gain.” But RCA in those days was a pop music factory, and her manager regarded jazz as sordid, so she was steered to music that appealed to a general audience with an emphasis on production values and artisanship instead of originality and artistry. When Ethel suggested she could do more with a song, the arrangers, producers, engineers and A&R men simply smiled and told her that perfect intonation and diction were enough. She only knew five of the

first twenty-four songs selected for her, most from Broadway shows and Hollywood films she had never seen. Producers knew she read music, so the lead sheets would be mailed to Baltimore, and she would arrive prepared at the New York studio to do her part with musicians and arrangers she also didn’t know. She never saw original contracts—just booking sheets and statements from Purcell’s office. On the few occasions when she was privy to insider conversations, she was appalled at the basic dishonesty of the music business, where multiple sets of books were common and performers manipulated like pawns.

To their credit, both Purcell and RCA invested money in their singer; they believed in her potential for show-business success and gave her advice based on what they knew. Purcell wanted her to sell the house she had just bought and move to New York. He hired Cholly Atkins, a well-known choreographer, to teach her how to move with the lyrics—part of an effort to groom her for big showrooms, where appearance and personality were at least as important as the music. He was also concerned about her nose and overbite and suggested cosmetic changes. RCA heavily promoted the first albums, lighting the photo sessions so that she wouldn’t appear too dark and highlighting her wholesomeness. They placed her own image on the album covers instead of white models, as Capitol had done, but the result was still whitewashed—a bland, in-between look, neither white nor Black, which fit the lush but empty arrangements. Well-known arrangers like Sid Bass, Dick Hyman, Claus Ogerman and even Clyde Otis worked on her recording sessions along with top-notch sidemen. Everything was professional, first class and ultimately middle-of-the-road mediocre. No pop hits nor entertainment “breaks” emerged from the first two albums. The music business was changing in the 1960s: rock and roll was ascending, Black musical roots were emerging and what people knew as jazz was on a slow decline.

When Ethel made a splash at the 1964 Newport Jazz Festival, the record label quickly released Eyes for You, which featured a small group with Ethel singing songs she knew with experienced, jazz-oriented musicians. They followed it in 1965 with My Kind of Waltztime, another small-group

project with Ethel singing familiar standards. A few singles like “The Girl from Ipanema” and “Matchmaker, Matchmaker” briefly got extensive airplay, but the only song I ever heard from RCA that had real pop chart potential was a duet arranged by Gary McFarland with singer Brook Benton. It was never released.

Purcell complained that Ethel didn’t have the all-out commitment for success; she wasn’t willing to sacrifice enough and said “no” too many times to his efforts to persuade her to participate wholeheartedly in the show-business life. He placed her with Matt Monro in Las Vegas, booked her at the Crescendo and other clubs in Hollywood and scheduled her on national media shows like The Bell Telephone Hour, The Tonight Show with Steve Allen and Johnny Carson, Mike Douglas, Dave Garroway, Arthur Godfrey and many others. She followed Newport with the Monterey Festival in 1965. Most of the time she showed up, did a good job and went home or to a hotel room with a television. Not too many people realized she was a battered woman with low self-esteem and deep suspicions about human motives, particularly men. She was happy singing songs with good musicians and on a few occasions fired house bands in order to hire players who knew what they were doing.

By 1966, she was still signed to Purcell, but both agreed that she would be a “semi-star”—someone not willing to take risks or make the sacrifices he believed necessary for popular acclaim but nonetheless “a talent deserving wider recognition.” The year before, she had met John Powell, a booking agent and manager based in Spokane, who heard her at Slate Brothers in Hollywood, where she shared the bill with comedian Pete Barbutti, one of his clients. They began an informal association that developed into engagements in Canada, the Northwest, California and Aspen, Colorado. Sometimes his gigs interfered with Purcell, and more than once she chose Powell, who got nervous when Purcell threatened him for messing with his “property.”

Ex-husband Jacques still visited Bernice next door, but Ethel was on the road almost nine months a year. When Purcell or Powell called with a job, she packed up her music bag and gowns, jumped on a plane and flew

around the country. In London, she became friends with Erroll Garner and shared rice and beans with Johnny Hartman. Musicians admired and respected her. Some fellow singers like Sarah Vaughan, Carmen McRae and Della Reese thought she might be stuck-up because she didn’t hang out with the entertainment crowd. She sometimes went out for Chinese food with the guys after a gig but usually kept to herself. There might be an occasional man, but the church girl didn’t shack. When she wasn’t out of town, Ethel still sang weekends at the Red Fox.

RCA never found the hit that might have moved Ethel into the upper echelon of the entertainment business, where people actually made money and lived well, and she never found “the song” that uniquely identified her to the public. Purcell’s efforts to make her a conventional star were doomed to failure from the beginning. Ethel occupied a very tenuous middle ground in a business where there is no middle ground: You’re either on top or at the bottom. She was interested in making a career and realized that she needed an act but found no one willing to put in the time and energy required. In some music industry quarters, she became known as a difficult artist: Someone who sometimes said “no” when the desired answer was “yes.”

The American music scene of the mid-1960s belonged to The Beatles, the Beach Boys, Simon & Garfunkel, The Monkees, Herb Alpert and Motown. Dionne Warwick had a hit with “Message to Michael,” but with a few possible exceptions like Nancy Wilson, there were virtually no new, jazz-oriented Black female singers with R&B roots who attracted much public attention.

five THE RED FOX AGAIN

In early 1967, Martha Schoeps’s feature writer decided he had enough of “soft news” and wanted to move on. She offered me the job: three stories a week and I could make my own hours. I couldn’t refuse. I thought I would write a few stories in advance so that I could hit the deadlines running. One story would be about Ethel Ennis and those few occasions when she still sang at the Red Fox. As a police reporter who listened to music while sipping a beer after work, I had gotten to know the performers at Henry Baker’s club Peyton Place across the street and sometimes walked over to the Red Fox to hear her. On one occasion, I brought a female friend from New York, and she remarked that there seemed to be an attraction working. I wanted to find out why this special person was still singing in a place that had already seen its best days. So after several attempts, in March 1967, I made an appointment for an interview. The neighbors said it was an awfully long interview. I kept returning, not so much to ask questions but to enjoy Ethel’s company. I had never met such an accomplished artist who was so completely natural—friendly, funny, earthy and unaffected by her art. Her gifts had developed naturally, she said, and she wanted to respect the talent. She hadn’t studied to become a singer, and her ambition had never been to become a professional entertainer. Her musical life had evolved organically, and like me, she was following where her skills led. She was naturally sophisticated and graceful and had experienced the wider world.

Wow, what was there not to like! And apparently the feelings were reciprocated. She and the Foxes thought I was “nice.” We had a date at the local Chesapeake Restaurant, and I accompanied her to the CBS building in New York on one of her dates at Arthur Godfrey’s show, then the only national radio program that still had a live band.

Because I was soft-spoken and gentle, Ethel figured I must be gay, but when I pushed the hotel beds together, she was quickly disabused of that notion. Our romance had begun, and I was introduced to show business. Peter Lassally—the nicest top show-biz professional I ever met—was still the show’s producer. By that time, the Arthur Godfrey Time radio program had been on the national airwaves for twenty-two years, and Godfrey in his sixties was not the powerful national presence he had been in the early years of television. A self- made New Yorker, he was an insecure, complex man— not the country bumpkin portrayed by Andy Griffith in the Budd Schulberg and Elia Kazan film A Face in the Crowd. However, like Lonesome Rhodes, he was also not the genial everyman who sold products like no one else and made CBS untold millions of dollars. At the height of his popularity—as the biggest media star in America, a friend of presidents, corporate heads and generals—Godfrey considered running for president. But his womanizing and controlling, sometimes abrasive, personality gradually seeped into public consciousness through a few well-publicized incidents, and he faded.

I think he also mellowed, although he still chased women, had temper tantrums with his staff and irritated the network brass, who supposedly despised him. They couldn’t ignore him because he retained a national audience who bought products and attracted top talents. His concern for our natural environments was genuine, and he constructively used his remaining celebrity to conserve them, all the while harassing the young women in his office.

On his seventieth birthday, more than a year after the show finally left the air, Godfrey’s New York mistress invited Ethel and me to a private birthday party at his penthouse—just the four of us for intimate dinner and conversation. He pointed with scorn to a gaudy sculpture, a gift from

William S. “Bill” Paley, he said, who didn’t have enough gratitude for all the money Godfrey had made for him. At seventy, Godfrey was a lonely celebrity in decline. As a teenager he had once slept next to The New York Times newspaper rolls on the street, and now he was a millionaire with a penthouse, private plane and Virginia estate complete with stables. But he was still driven—by sex, power and the need for public acclaim—all with an amiable, man-of-the-people exterior.

When Ethel first started appearing on his show in 1964–65, he invited her to the same penthouse for dinner and tried to seduce her by emerging nude from his mirrored bedroom. Stunned and then angry, she stormed away and walked twenty blocks in the rain back to her hotel. From Godfrey’s perspective, he was merely following long habits of seduction. He once told me that every successful American male he had ever met—and he encountered a lot of them—needed to empty his seminal vesicles at least once every twenty-four hours. The only exception, he said, was General Curtis LeMay. (I realized then that I would likely never become very successful in America.)

For a long time after this incident, Ethel wasn’t invited back to tape more shows, but she gradually became a semi-regular along with Richard Hayes, the male vocalist. We traveled once with the show to Miami for a week and later to the Michigan State Fair. Ethel sang duets with Godfrey, and I even interviewed him for a Sun article. The musicians over the years were good company, most of them from jazz backgrounds: Remo Palmier, Lou McGarity, Gene Traxler, Hal McKusick, Sy Mann, Hank Jones, Johnny Parker and Gerry Alters. Most people around Godfrey didn’t last more than a few years, but a few did, particularly those who didn’t challenge his ego. Peter Lassally left Arthur Godfrey Time in 1969 to become producer of The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, then David Letterman and Tom Snyder. We stayed in touch in the early years and had dinner with the Lassallys in 1973, when we flew to Los Angeles for Ethel to do The Tonight Show after receiving acclaim for singing the National Anthem at Richard Nixon’s second inauguration. Lassally is now retired as “a talk whisperer,” master of the talk-show format who learned from Godfrey how the host

should speak directly in personal conversation to that one viewer or listener on the air. I once saw Godfrey verbally abuse this man terribly in a New York theater and wondered how he could take it. Later I learned Lassally had spent two years as a youth in Nazi concentration camps.

After that first New York trip in 1967, Ethel and I returned to Baltimore and began spending more time together. By the time she traveled west again to sing at the Spokane House, another John Powell gig, I was in love. Ethel was skeptical. “What do you mean by love?” she asked, so I wrote her a two-page screed by a twenty-seven-year-old who, apart from his mother and sister, had loved only three women in his life: his high school sweetheart, German fiancée and New York girlfriend.8

8 See Appendix B: Love Letter

SUNSET DOHENY

After Spokane, Ethel was scheduled to sing for three weeks at the Hong Kong Bar in the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles, so I decided to meet her there. I had vacation time before my new job started, and I wanted to know where our romance was going. So I flew to LA and made my way to the Sunset Doheny Motel, where Ethel had camped with her gowns, wigs, lingerie, shoes and music. This was a Powell gig, prestigious but low paying. Purcell would have had her staying at the Century Plaza for more money, a good portion of which would have gone into his bank account. The Plaza, opened in 1963 with great fanfare, had decided to make its dimly lit, 300-seat Hong Kong Bar into the kind of jazz room that once flourished on the Strip. It wouldn’t last long. Like Ethel’s musical career, the timing was all wrong. Show-business money, and the high rollers and gangsters who spent it, had migrated to Vegas, and musical tastes among the young had changed. Jazz didn’t speak to the rock and rollers. Even Hugh Hefner lamented that romance and sophistication had disappeared from the Strip. Purcell did send Stan Pat, his West Coast rep, to check on Ethel, but she was basically on her own with me as young lover to assist.

The Hong Kong Bar was the fourth LA nightclub for Ethel in three years. She first visited Los Angeles with friend and guitarist Walt Namuth in 1964 to perform at the Crescendo, a jazz-oriented show room where people like Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Mel Tormé had recorded

and performed many times. It had been sold the previous year and was closing, so Ethel encountered a cold atmosphere with a house band that couldn’t play her music. She ended up paying off the band and bringing in different musicians, making a grand total of $12 for the week. There was some compensation in subsequent experiences. At The Scene, she held hands with Peggy Lee, who taught her how to drink brandy, and at Slate Brothers, she shared a bill with Pete Barbutti, who attracted such luminaries as Red Buttons, Allen Ludden and Betty White, and Ernie Kovacs and his wife, Edie Adams.

May 1967 was the advent of the Summer of Love on the Sunset Strip. Most of the real hippies gathered in San Francisco, but the Strip had its share of youngsters who crowded its length to listen to music in the clubs and just “be” together. Six months earlier, police had clashed with about 1,000 youths protesting a strict curfew and loitering law designed to reduce the street crowds around the rock clubs, particularly Pandora’s Box at 8118 Sunset, about eight blocks east of the Sunset Doheny. Frank Zappa, Peter Fonda, Jack Nicholson, Sonny and Cher and other celebrity supporters of the counterculture were there to observe and encourage a peaceful demonstration that turned violent. Property was destroyed; protestors were arrested. A month later, Stephen Stills, a member of Buffalo Springfield, recorded “For What It’s Worth” at Gold Star Recording Studios in Beverly Hills, about two miles from our motel. It was still playing on the radio when we arrived. The Whiskey a Go Go, where Buffalo Springfield had operated as a house band for a while and which many consider the birthplace of LA rock and roll, was just up the street. So we were in the center of West Hollywood counterculture in the beginning years of its rock-and-roll era but didn’t know it.

Every evening we took a cab to the hotel. I assisted Ethel in the small basement dressing room, and she performed sets of jazz standards, sprinkled with songs from her RCA albums and supported by the Joe Kloess Trio. People like Buddy Greco dropped by to listen, and Variety, the traditional show-biz bible, gave her performance a good review. We enjoyed it, but Purcell probably would have hated it. There was no “act,” no

professional lighting and she gave the musicians too much time to solo. By the time we returned to the motel, the streets were relatively quiet, although there were always lingering crowds at the Whiskey, particularly on weekends. During the day we walked up and down the Strip and found good cheap places to eat as well as wine-and-cheese stores for provisions to bring back to the motel. One double bed acted as storage for all of Ethel’s junk; we snuggled and slept on the other. Scotty, a friend from Baltimore, took us around in his Cadillac, including jaunts to Compton joints where you could enjoy chitlins and champagne. On one occasion, a former Army buddy took us sailing. Sarah Vaughan invited us to lunch, and while the two singers exchanged compliments, I studied her white male companion. Ethel had already bought me some clothes to overcome my baggy newspaper look, and I was vaguely uncomfortable at the thought of being supported by a woman. Would I be a convenient “occasional man”? The Black/white combination wasn’t unusual in the entertainment business, where men and women often manipulated each other. Our love had nothing to do with skin color, but we lived in a society where the color line still mattered, and I knew our romance might have problems in America. The three weeks at the Sunset Doheny amounted to a “honeymoon;” we were together 24/7 and enjoyed every minute. Ethel then made her way to another Powell gig at the Spokane House, and I headed back to Baltimore to begin my new writing job on June 1.

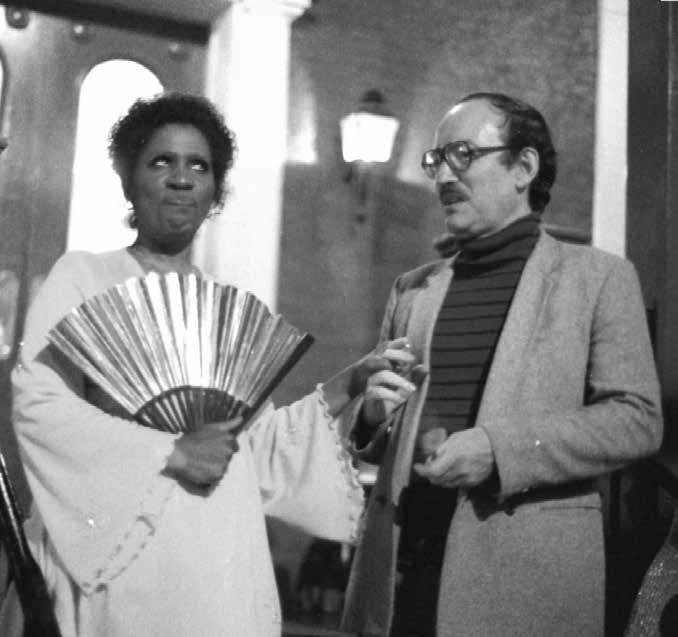

At the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles, 1967

SHACKIN’

By this time, our real marriage had already started, even if it wasn’t legal. We were bound to each other, each giving what the other wanted and needed, the whole bigger than its parts. When Ethel returned, I began moving my few belongings from a bachelor apartment on Bolton Street to her house near Mondawmin Mall. The late Gerald W. Johnson, one of the Sun’s luminaries from the H. L. Mencken era, lived in Bolton Hill then, and I was asked if I wanted to meet him. “Sure,” I replied. Johnson was a distinguished journalist and writer, and I might learn something. After more than fifty years, I still remember our conversation. Baltimore was a fine city, he said, until “the niggers” from the South arrived during World War II and caused its current ills.

I was shocked by his prejudicial language and realized that’s who I was about to join in West Baltimore. Baltimoreans, in my experience, were pretty much the same, Black and white. If anything, the Black folks were more vibrant and culturally alive than their white counterparts, who seemed locked into old social patterns and ethnic neighborhoods. My brother’s first mother-in-law, a grande dame from New Orleans, visited in 1966 and told me that with my manners and international background, I was a prime candidate for Baltimore society, which she seemed to regard as on par with her own. By that time, I was frequenting the jazz clubs and ignored her advice.