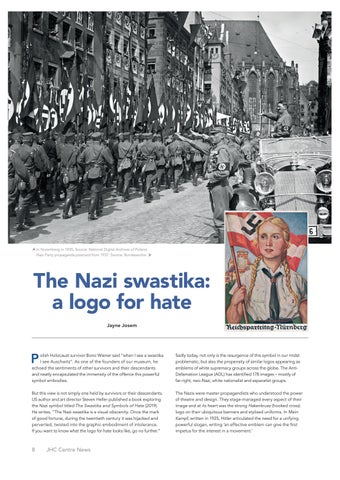

In Nuremberg in 1935. Source: National Digital Archives of Poland. Nazi Party propaganda postcard from 1937. Source: Bundesarchiv.

The Nazi swastika: a logo for hate Jayne Josem

P

olish Holocaust survivor Bono Wiener said “when I see a swastika I see Auschwitz”. As one of the founders of our museum, he echoed the sentiments of other survivors and their descendants and neatly encapsulated the immensity of the offence this powerful symbol embodies.

Sadly today, not only is the resurgence of this symbol in our midst problematic, but also the propensity of similar logos appearing as emblems of white supremacy groups across the globe. The AntiDefamation League (ADL) has identified 178 images – mostly of far-right, neo-Nazi, white nationalist and separatist groups.

But this view is not simply one held by survivors or their descendants. US author and art director Steven Heller published a book exploring the Nazi symbol titled The Swastika and Symbols of Hate (2019). He writes, “The Nazi swastika is a visual obscenity. Once the mark of good fortune, during the twentieth century it was hijacked and perverted, twisted into the graphic embodiment of intolerance. If you want to know what the logo for hate looks like, go no further.”

The Nazis were master propagandists who understood the power of theatre and design. They stage-managed every aspect of their image and at its heart was the strong Hakenkruez (hooked cross) logo on their ubiquitous banners and stylised uniforms. In Mein Kampf, written in 1925, Hitler articulated the need for a unifying powerful slogan, writing ‘an effective emblem can give the first impetus for the interest in a movement.’

8

JHC Centre News