11 minute read

Professor Philippe Sands oration ‘Human beings reach a crossroad’

Professor Philippe Sands gave the keynote address at the Betty and Shmuel Rosenkranz Oration held in November 2021

Human beingsreach a crossroad

Advertisement

This is an edited version of his address.

This year is the 75th anniversary of the Nuremberg Judgement, a point of recollection and re ection to ask ourselves what has been achieved and what are the challenges.

I had no idea when I accepted an invitation to go to the city of Lviv in Ukraine, in the autumn of 2010, what would follow. As many of you know from reading my book East West Street, the invitation was to give a lecture on my work on crimes against humanity and genocide.

I had been involved in many cases before international courts and tribunals involving many horrors across the world, but there was also the personal aspect of my mother’s place in the Holocaust and the story of my grandparents. I did not accept that invitation because I had a burning desire to give a lecture, but because I wanted to nd my grandfather’s house, the place where he was born in 1904, in a city called Lemberg, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. I found the house and learned more about my grandfather and his story and his identity, and by learning about his identity, I learned a lot more about my identity. It accidentally unleashed a whole tale when I had not been looking for any discoveries.

I uncovered the fact that the man who invented the concept of crimes against humanity, which is intended to protect individuals, and the man who invented the concept of genocide, the protection of groups, both came from the city of Lemberg (now Lviv, but Lwow when it was under Polish rule).

Hersch Lauterpacht would go on to be professor of international law at Cambridge University, a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trial and a judge at the International Court of Justice. Raphael Lemkin had started off life as a criminal prosecutor and he, too, helped in the prosecution at Nuremberg.

The Buchholz family, circa 1913.

In the course of that trial, they learned that Hans Frank, the man they were prosecuting who had been Adolf Hitler’s personal lawyer and who, in 1939 became Governor General of Nazi occupied Poland, was actually responsible for the murder of their entire families.

That is a huge thing. I do cases before international courts and tribunals, and I cannot imagine what it is like to learn that the man who sits just a few feet in front of you, Hans Frank in this case, was responsible for the killing of your entire family. One of the things I discovered in writing East West Street, beyond the signi cant role played by the three main men in the book— Hersch Lauterpacht, Raphael Lemkin and Hans Frank, but also the story of my grandfather—was the vital difference that individuals can make.

When human beings reach a crossroad, they can do the right thing, they can do the wrong thing, or they can do nothing. There are those who reach such a crossroad and do the right thing, even if it comes at a very great price, and even if the sacri ce they might make is liable to be the ultimate sacri ce. One such person is the remarkable Elsie Tilney.

In 2010, when I was looking for the address of my grandfather’s house, Elsie Tilney appeared in his papers. A tiny scrap of paper just said ‘Miss E.M. Tilney, Menuca, Bluebell Road, Norwich, Angleterre’.

I learned that Elsie Tilney was an evangelical Christian missionary who came from Norwich. In early 1939, she happened to be in Paris where she happened to meet my grandfather who told her that he had a daughter less than a year old living in Vienna who needed to be brought to safety. And Ms Tilney travelled by train to Vienna and carried back a one-year-old infant to Paris and safety.

If Elsie Tilney had not done what she had done, I would not be here today. Who knows how I would react to Elsie Tilney if I met her in the street? She never told a single person all the extraordinary things she did during that terrible con ict, but I owe my existence to her, and I am intensely grateful for that, and it has caused me to re ect on those individuals who do absolutely remarkable things.

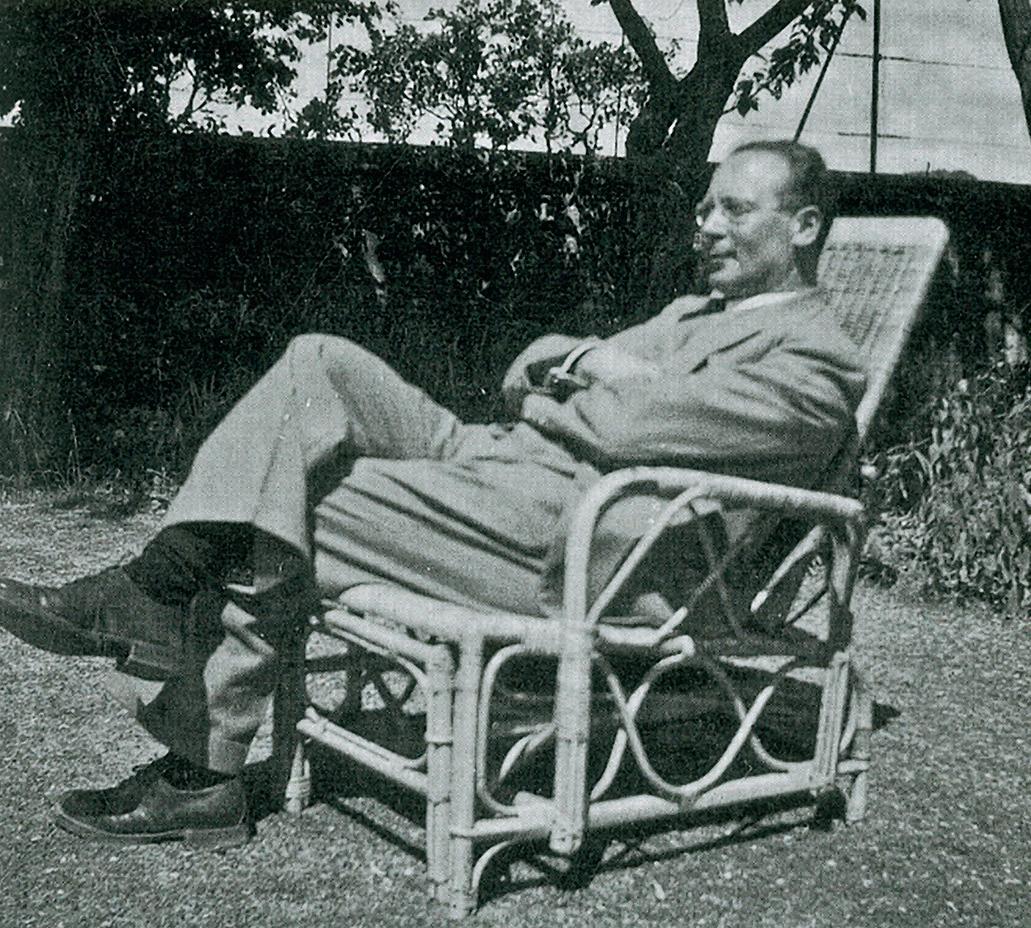

Lauterpacht in Cambridge Garden, 1945.

In writing East West Street I have come to know the son of Hans Frank, Niklas Frank, a distinguished journalist who has become a good friend. It is remarkable to imagine that the son of a man hanged at Nuremberg 75 years ago for the greatest crimes imaginable should become the friend of the grandson of one of his father’s victims, but that is what has happened.

One day Niklas asked me if I would like to meet Horst Wachter. Horst’s father, Otto Wachter, had been the governor of Lemberg in 1942 when the Final Solution was implemented in District Galicia, of which Lemberg was the capital.

In 2012, Niklas and I travelled to Hagenberg, Austria, a tiny village, where we met this remarkable man in his extraordinary home, a dilapidated 15th century castle. Horst lives in real poverty. Only two or three of his hundred rooms were habitable or heated, and it was bitterly cold that rst time that I met him.

Niklas bears the burden of having a father who murdered four million people and was convicted and hanged, and he despises his father. Horst is different and looks for the good in his father.

And so began an adventure, an exercise, an uncovering of another family and The Ratline is what emerged.

Contrary to Horst’s belief, Otto Wachter was not a decent man. In 1938, he was charged with removing all Jews from public of ce and in 1939 he was appointed as governor of Krakow. He built the Krakow Ghetto and, in 1942, he was posted to District Galicia where he oversaw the implementation of the Final Solution. In August 1942, when Heinrich Himmler travelled to Lemberg to ask Wachter whether he wanted to remain in District Galicia or return to a desk job in Vienna, Wachter chose to stay and see this through. There is evidence to show how ef ciently he did his work and how pleased Heinrich Himmler was with it. After the war, Otto Wachter was indicted for mass murder but, unlike Niklas Frank, he disappeared.

Horst had a vast family archive of 10,000 pages of letters, dairies, images, scrapbooks and photographs that I convinced him to donate to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. When he offered me a digitised copy, I was unable to resist and, together with a team of researchers, I spent four years deciphering their remarkable contents.

With these documents, I was able to uncover that Otto Wachter had hidden in the Austrian mountains after the war, not so far from Salzburg, where his wife Charlotte lived. For three years, Charlotte helped him to survive by supplying him with clothing, newspapers, food and skis every two or three weeks. During this time, Otto Wachter was not alone, but was in hiding with a young Waffen-SS soldier called Burkhardt Rathmann. When I questioned Horst in 2017, I found that Burkhardt Rathmann was still alive and I had the opportunity to visit him.

Burkhardt Rathmann imposed a condition that I must ask no question about anything that happened before 9 May 1945, as he had been in a Waffen-SS division which had committed the most terrible of atrocities and was worried about what would happen to him. At this remarkable meeting I learned that Otto Wachter had wanted to make his way out of Europe, along ‘The Ratline’ to South America, to Argentina, like Mengele, Eichmann, Priebke, Klaus Barbie and so many others. And hence I stumbled into a book that became The Ratline.

In a way, The Ratline is a counterpoint to East West Street. Although there is quite a lot of overlap, I wrote it because it raises the question: Why do decent, honourable, educated, religious, intelligent, cultured human beings get involved in the most terrible things? And that is an issue for our day with the rise of nationalism, xenophobia, and populism.

I am, of course, deeply concerned about victims, but ultimately if we want to stop these horrors from happening we need to understand the perpetrators, and The Ratline explores how ordinary folk get involved in mass murder.

At the 75th anniversary of the opening of the Nuremberg trial in 2020, I met the president of Germany, Walter Steinmeier, and we talked about the disappearing voices of those who are able to speak rsthand about what happened. That remarkable and important generation will very soon no longer be with us and one motivation for my work is to keep the ame alive, to recapture the stories and to pass them on to future generations. With the disappearance of those voices, it becomes all the more important to record them.

Leon school card, 1915.

Ultimately, when good things and terrible things happen it is individuals who are at the heart of it, and we need to understand those individuals.

Doctors’ trial, Nuremberg, 1946-1947.

There are four international crimes that have been on our statute books since 1945, war crimes, which were invented in the 19th century—crimes committed during the conduct of war or armed con ict—and three invented in the Nuremberg context: the crime of aggression—waging illegal war—crimes against humanity— killing or harming large numbers of individuals—and the crime of genocide, which concerns the destruction of groups.

These four crimes focus, very understandably, on the protection of individuals, of human beings, and of groups of human beings. They do not, however, cover the protection of our natural environment, which is why recently I have been working with an international working group to come up with a de nition of a fth crime— ecocide—the destruction of our natural environment.

As we were doing our work, I thought back to Lauterpacht and Lemkin. In 1944 and 1945, as the war was going on, these two remarkable human beings, instead of curling up and weeping, decided to take the power of ideas and create two new international crimes: crimes against humanity and genocide.

Many people laughed at them. Many people said to Raphael Lemkin that his new idea of a crime of genocide was hopeless, but he persisted, and it was included in the indictment of the Nuremberg trial. When the judgement failed to mention the word genocide, again, he picked himself up and spent the next three years drafting and lobbying for the adoption of the world’s rst multilateral human rights treaty, The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, signed in Paris in December 1948, a day before the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, which was an idea of Hersch Lauterpacht’s.

Again, individuals make a difference.

Why did I get involved in this? Apart from teaching international environmental law, I have children who are extremely concerned about climate change. Like Lauterpacht and Lemkin, I do not believe that the law itself can ever solve a particular problem. It needs to be accompanied by a whole raft of other actions—diplomatic, political, cultural— and it needs, of course, political will, but what the law can do is affect a change in consciousness.

I became very aware of that when I met Thomas Buergenthal a few days before a case in The Hague in which I was acting for The Gambia against Myanmar in relation to the mistreatment of the Rohingya.

A former American judge at the International Court of Justice and a child survivor of Auschwitz, he noted that it was remarkable that my case was to be based on Lemkin’s ‘Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide’. And that is the huge change that has taken place since the Second World War. Our world may not be perfect, but there are now international standards which say that this kind of behaviour is not acceptable and that you have to protect the dignity of human beings and the rights of individuals and of groups.

In these dif cult times of COVID-19, climate change, rising populism, nationalism, and fascism, it is possible to imagine a different path. Each of us can make a difference and put our energies into a tiny but positive thing to make a real difference.

The world is not perfect, but it is a better world than it was 75 years ago. We have principles and standards and rights that did not exist before. They have not ended the horrors, but they have allowed us to say, at least with some degree of objectivity: no, you cannot treat people that way, you cannot treat individuals that way, you cannot treat groups that way.

Nuremberg, for me, is about a fundamental principle. We are all in this together. No person is above the law. Let us protect the values we care about, protect our institutions and ght for the idea of the rule of law, because it is the only language that each of us has and shares.

Out of the terrible events of 1933 to 1945, there can be positive developments. As the singer and poet Leonard Cohen put it, ‘There’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’.

Professor Philippe Sands QC is Professor of Law at University College London and a practising barrister at Matrix Chambers. He is also an award-winning author of The Ratline (2020), East West Street (2016), Torture Team (2008) and Lawless World (2005), and contributor to the New York Review of Books, Vanity Fair, the Financial Times and The Guardian.