Not with ink, but with blood and tears The

diary of Yitzchak Meir Kluska

News SEPTEMBER 2018 The magazine of the Jewish Holocaust Centre, Melbourne, Australia Registered by Australia Post. Publication No. VBH 7236

Centre

JHC Board:

Co-Presidents

Pauline Rockman OAM

and Sue Hampel OAM

Treasurer Richard Michaels

Vice-President David Cohen

Secretary Elly Brooks

Other Directors

Allen Brostek

Anita Frayman

Abr am Goldberg OAM

Paul Kegen

Phil Lewis

Helen Mahemoff

Melanie Raleigh

Mary Slade

The Jewish Holocaust Centre is dedicated to the memory of the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators between 1933 and 1945.

We consider the finest memorial to all victims of racist policies to be an educational program that aims to combat anti-Semitism, racism and prejudice in the community, and fosters understanding between people.

JHC Foundation:

Chairperson

Trustees

Helen Mahemoff

Nina Bassat AM

Joey Borensztajn

Allen Brostek

David Cohen

Jef frey Mahemoff AO

JHC Staff:

Executive Director War ren Fineberg

Curator and

Head of Collections

Director of Education

Director of Community

Jay ne Josem

Lis a Phillips

Relations & Research Dr Michael Cohen

Director of Marketing & Development Leora Harrison

Director of

Testimonies Project Phillip Maisel OAM

Librarian/Information Manager Julia Reichstein

Senior Archivist Dr Anna Hirsh

Audio-Video Producer

Education Officers

Marketing Manager

Executive Assistant

Finance Officer

Office Manager

Communications Officer

Volunteer Coordinator

Bookkeeper

Database Coordinator and IT Support

Centre News:

Editor

Yiddish Editor

Robbie Simons

Fiona Kelmann

Anatie Livnat

Fanny Hoffman

Danielle Kamien

Evelyn Portek

Leon Mandel

Lena Fiszman

Tosca Birnbaum

Rae Silverstein

Daniel Feldman

Daniel Feldman

Ruth Mushin

Alex Dafner

13–15 Selwyn Street

Elsternwick Vic 3185

Australia

t: (03) 9528 1985

On the cover:

Genia Janover and Judy Kluska with Yitzchak Meir Kluska’s diary

Photo: Zina Sofer

This publication has been designed and produced by Grin Creative / grincreative.com.au

f: (03) 9528 3758

e: admin@jhc.org.au

w: www.jhc.org.au

OPENING HOURS

Mon–Thu: 10am–4pm Fri: 10am–3pm

Sun & Public Hols: 12pm–4pm

Closed on Saturdays, Jewish Holy Days and some public holidays

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in Centre News are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the magazine editor or editorial committee. While Centre News welcomes ideas, articles, photos, poetry and letters, it reserves the right to accept or reject material. There is no automatic acceptance of submissions.

IN THIS ISSUE From the Presidents 3 Editor’s note 3 Director’s cut 4 Education 4 Precious new arrival: a Torah scroll that survived the Holocaust 5 Remember the past – build the future 6 Not with ink, but with blood and tears 10 Survivors remember the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising 12 Jewish life in Germany today 14 Failing to understand failure: reassessing the Evian Conference of 1938 16 Anita Selzer in conversation with Lisa Phillips 20 Jewish Rescuer Citation awarded to Ronia Rozental 22 Lowicz: a city sentenced to death 23 My Holocaust memorial year abroad at the Jewish Holocaust Centre 24 Hope for a better future 25 Keeping their memories alive 26 Ex tracts from my MOTL journal 27 JHC Social Club 28 Young Friends of the Jewish Holocaust Centre 29 Seen around the Centre 30 New acquisitions 32 Celebrating through giving 33 Community news 34

From the Presidents

Pauline Rockman OAM and Sue Hampel OAM

Dr Anna Hirsh, Senior Archivist at the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) brought out a miniature notebook not much larger than a 50-cent piece, totally covered in tiny handwriting in Polish: the diary of Romuald Mrozowski. It had been brought to the JHC by his stepdaughter at the suggestion of her son, who was so affected by his visit to the JHC as a high school student over 20 years ago that he thought it would be the best place for it. Romuald was involved in the Warsaw Uprising that took place one year after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and was captured as a POW.

We thank our translators who bring amazing stories like this to a wider audience. They do a fantastic job deciphering difficult handwriting and dealing with difficult subjects.

The JHC Collection is our most treasured resource, and has immense cultural value within both Australian and Holocaust history. Comprising documents, photographs, artefacts, rare artworks and oral history recordings, the collection presents tangible evidence of the lives of those who suffered under Nazi persecution. Outstanding community support has enabled the JHC to use the most cutting-edge technologies in the collection and exhibition of priceless artefacts from the Holocaust period.

The JHC continues to be a hive of activity. We have recently hosted a number of public lectures and book launches, and the exhibition ‘Jewish Life in Germany Today’.

Mandy Myerson and Bianca Saltzman organised a commemorative event for Yom Hashoah at the JHC, attended by 250 young adults. We are very pleased to see the next generation’s interest and involvement in the area of Holocaust remembrance.

In May we attended the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) plenary in Rome as part of the Australian delegation, in Australia’s new capacity as a liaison country. Australia will move to full IHRA membership by June 2019, and we are very grateful to Sir Eric Pickles and the English delegation for their guidance in this journey. Meeting and sharing information and resources is a great benefit of these sessions, not to mention hearing from Professor Yehuda Bauer, the IHRA honorary chair.

In June, Sue Hampel and Jayne Josem, JHC Curator and Head of Collections, gave presentations at Yad Vashem’s 10th International Holocaust Education Conference. The conference was attended by 350 delegates from over 50 countries.

The JHC education program attracts over 22,000 students from schools throughout Victoria. In addition, over 10,000 others visit the museum, and over 100 events are held throughout the

year. We are delighted that City of Glen Eira has approved our preliminary building plans and we can now move forward in redeveloping our facilities. We shall be retaining as much of the original building as practical, but our architect has incorporated sufficient space to meet the needs of the JHC for next 20 or more years.

Dear friends, our work is arguably even more relevant today than it was when the JHC was established in 1984, and we look forward to your support in this exciting development.

Editor’s

Ruth Mushin

Now that the preliminary plans for the redevelopment of the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) have been approved, we are excited to bring you an artist’s impression of how the new building will look and some of the facilities it will house.

We continue to feature survivor stories in this edition of Centre News . Sam Brygel presents witness accounts of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising taken from the JHC’s Phillip Maisel Testimony Project. These moving stories of survivors who were children and teenagers at the time bring to life memories of both the uprising and daily life in the ghetto. The late Yitzchak Meir Kluska’s story of survival in a claustrophobic bunker with six others in Jedrzejow, Poland, for two years during the war is another remarkable story. His family recently presented the JHC with his precious diary, written in Yiddish in that bunker. We also feature the story of another precious acquisition – a Czech Torah scroll from the town of Valasske Mezirici that was rescued from the Czech Republic and found its way to Melbourne.

Michaela Glass, the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor and recipient of the Irene and Ignace Rosenthal Scholarship, presents a moving account of what happened to her grandfather’s hometown of Lowicz, Poland, during the Nazi occupation, and Professor Paul Bartrop writes a thoughtful analysis re-examining the impact of the Evian Conference of 1938. I hope you enjoy these and the many other articles in this edition.

JHC Centre News 3

note

Education Lisa Phillips Director’s cut Warren Fineberg

Ihave recently been on a two-week trip to Japan with my family, during which we visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. While still in Melbourne I arranged for Mrs Tamura, a volunteer survivor guide, to show us through the park and museum. As we toured the remains of the Genbaku Dome and the various memorials to the victims, including those who helped the injured after the blast and subsequently succumbed to radiation poisoning, Mrs Tamura told us her story. She was a child when the bomb hit Hiroshima but had been sent on an errand a few kilometres from the site. Her parents, however, were in the explosion zone but miraculously survived. Mrs Tamura is a champion for peace and asks that we each do what is in our power never to allow a nuclear tragedy such as that experienced by Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be repeated. I felt humbled to have met Mrs Tamura and found strong parallels between her experience and the message of our Holocaust survivors in Melbourne.

I would like to welcome Danielle Kamien, our new Marketing and Communications Manager. Danielle is assisting the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) to promote activities and events, and is involved in our fundraising efforts to help meet our operational requirements.

On the back cover of the last edition of Centre News, Holocaust survivor Sarah Saaroni OAM was featured calling on members of the community to consider donating Holocaust material to the JHC archives. I would like to remind families of survivors of the need to protect and preserve Holocaust artefacts for future generations, and ask that you endeavour to locate any material in your home that needs care. Curator Jayne Josem or Senior Archivist Dr Anna Hirsh will be happy to speak with you about the best way to preserve this material, and how to donate it to the Centre if you wish.

Plans for the new Centre have been approved by the City of Glen Eira, and Helen Mahemoff, Phil Lewis and Leora Harrison have been working tirelessly on preparations for a capital appeal. I encourage all our supporters to get behind this project that will deliver a major gift to all Victorians, and be an enduring legacy to our survivors and those who died in the Holocaust.

The Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) education programs continue to break student attendance records, with each session often booked with more than one school. This May, for example, 1,000 more students participated than in May last year. We have also seen an increase in bookings for the Hide and Seek program, our program specifically designed to meet the needs of younger students. This is a wonderful team achievement and I am grateful to all our survivors and volunteer guides who devote so much time and energy to ensure that we deliver excellent Holocaust education. I am also indebted to our educators Anatie Livnat, Fiona Kelmann and Fanny Hoffman, as well as Tosca Birnbaum and Rae Silverstein who work tirelessly behind the scenes.

We have welcomed a number of new guides to our weekday teams, which has enabled us to meet the increasing demands of the school programs. We have also welcomed two new Holocaust survivors as speakers: Ivan Jarny, who was a partisan, and Eva Telman who fled with her family to the USSR during the Second World War.

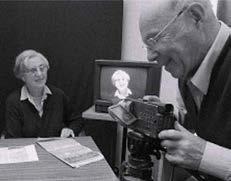

As personal accounts by survivors remain at the heart of our education programs, we have explored ways of enhancing the delivery of survivor stories by using video testimony. Showing video testimony with a survivor present, followed by a question and answer session, has proven to be most successful for students and survivors.

Through our Custodian of Memory program, we have developed a model of guiding in the museum if a Holocaust survivor is not present. Instead, the experience of individual survivors is delivered through scripted narrative and using the Eyewitness testimony film, created in early 2000. This model ensures that the survivor’s voice remains central to visitors’ experience in the museum.

Our professional development sessions, including the Rosalky Professional Development sessions at the beginning of each term, continue to be well attended as we strive to learn and become more skilled in our delivery of the material.

Having an exhibitor stand at teacher conferences has allowed the education team to promote the work of the JHC, as well as advise on teaching the Holocaust. We have attended the Victorian Association for the Teaching of English and History Teachers’ Association of Victoriaannual conferences, providing the opportunity for valuable discussion, as well as enabling us to present workshops on various themes related to the Holocaust.

4 JHC Centre News

In April, the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) became the custodian of a precious Torah scroll. The scroll was presented to the Centre by the Memorial Scrolls Trust, a UK-based organisation whose mission since the 1960s is to conserve and preserve Czech Torah scrolls that survived the ravages of the Holocaust.

Dr Joseph Toltz, a Sydney academic who represents the Memorial Scrolls Trust in Australia, formally handed over the Torah scroll, which came from Valasske Mezirici, colloquially known as Valmez. The small Jewish community of Valmez had existed since the middle of the 19th century and in 1930 it comprised 150 people. The scroll, which was used in the synagogue, was one of 1,564 Torah scrolls from the provinces of Moravia and Bohemia that were rescued in Prague by a group of Czech Jews during the war, and later saved from neglect by British Jews when Czechoslovakia was under communist rule.

Almost the entire Jewish population of Valmez was murdered during the Holocaust, and this is the only sacred artefact that miraculously survived from that community. In presenting it to the JHC, Dr Toltz said, ‘As one of the premier institutions of Holocaust remembrance in Australia, I knew that you would be an excellent choice to tell the stories of the Jews of Valmez, the curators of the Jewish Museum of Prague, the second saving of the scrolls by the Westminster Synagogue, and the incredible circumstances that have led to this scroll’s arrival in Australia.’

The story of the rescue of the scroll begins with the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, when Jewish congregations were

A precious new arrival

Jayne Josem

closed down and their synagogues destroyed or deserted. In 1930 there were 117,551 Jews in Bohemia and Moravia. By 1943 some 26,000 had managed to emigrate. Around 81,000 Jews were deported to Terezin and other camps, of whom about 10,500 survived. In total, around 80,000 Jews from Bohemia and Moravia died during the Holocaust. Prior to the war, 60 of the 350 synagogues were destroyed (mostly in the Sudetenland). Those remaining were abandoned and left to decay, and when the Communists came to power 80 were demolished.

In 1942, a group of members of Prague’s Jewish community devised a way to rescue the religious treasures from the deserted communities and destroyed synagogues, and bring them to the comparative safety of the Jewish Museum in Prague. The Nazis were persuaded to accept the plan, and more than 100,000 artefacts were brought to the capital. Among them were about 1,800 Torah scrolls. Each was meticulously recorded, labelled and entered on a card index by the museum’s staff with a description of the scroll and the place it had come from. In his speech, Dr Toltz referred to the speculation that the Nazis were hoarding this material for a future ‘Museum of an Extinct Race’, but added that ‘there is no documentary evidence from the Nazis to state this as a specific motive’.

After the war, the scrolls were transferred to the ruined synagogue at Michle, outside Prague, where they remained until they came to London. Some 50 congregations re-established themselves in the Czech Republic after 1945, and were provided with religious artefacts. When the Communists took over in 1948, Jewish communal life was again stifled, and most synagogues were closed. The initiative to keep the remaining 1,564 Torah scrolls safe was taken by London Jews, who purchased them from the Communist government and brought them back to Westminster Synagogue. The full story of how the scrolls came to London can be found in the book Out of the Midst of the Fire by Philippa Bernard. It is also detailed on the Memorial Scrolls Trust website: memorialscrollstrust.org.

This particular scroll had been used in the 1970s in a synagogue in Brisbane until it was declared posul (unkosher), making it unusable for religious purposes. The synagogue then handed it to the Brisbane Museum, where it was stored safely for many years. The mission of the Memorial Scrolls Trust is for these scrolls to be visible to a wider public, hence the transfer to the JHC in Melbourne, where over 22,000 school students and many adult visitors come each year to learn about the Holocaust and its wider implications.

JHC Centre News 5

Jayne Josem is JHC Curator and Head of Collections.

Dr Joseph Toltz and Jayne Josem

Remember the past Build the future

The Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) is set to undergo the most significant redevelopment since opening its doors to the public in 1984. This major project, expected to cost between $15,000,000 and $16,000,000 (including relocation costs during the build), will bring the museum into line with other world-class museums.

Since the addition of a new building in 1999, we have continued to expand our activities and now find that we have outgrown our existing facilities. Each year our visitor numbers have increased and our premises are no longer adequate to accommodate the growing number of school visits, exhibitions and special events we host each year. It has thus become clear that we need to ensure that our museum will be sustainable for at least the next two decades.

6 JHC Centre News

JHC Centre News 7

Artist’s impression of the new building incorporating the facade of Fink House.

The need for the new centre is a wonderful endorsement of the work we do, and we should all feel proud that demand for our services continues to grow.

The building we are currently using was intended to accommodate 18,000 visitors – students and members of the public – annually. In 2017, 32,000 people visited the JHC, among them 22,000 students who attended our school-based education programs. In addition, we hosted 100 public events and two special exhibitions (which, for reasons of space) can only be held during school holiday periods). The need to accommodate such large numbers of visitors poses immense challenges for our day-to-day operations and limits our ability to respond to increasing school and community demand for our services.

Following an extended consultation process with guides, volunteers, staff, the JHC Board and community leaders, we have concluded that we need to redevelop our existing facility in Elsternwick both to accommodate current demand for our services and to provide for future growth. Preliminary plans indicate that we can increase our floor space by 180 per cent, yet maintain our current footprint.

More than 650,000 Victorian students have visited the JHC since its establishment. The Centre provides a powerful voice, bearing witness to dehumanisation and mass murder. It is a memorial to the six million Jews murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust, and pays tribute to those who survived but suffered so much loss

and grief. With this in mind, we understand the enormity of our responsibility to keep the voices of our survivors alive and assume custody of their vision for the Centre, while ensuring we do not forget our past, and build for the future.

The JHC already has an excellent reputation both locally and internationally. However, this planned extension will cement our place on the map as a ‘must see’ museum on a global scale.

Some of the features of the new museum will include:

•a pur pose-built Children’s Mus eum to inc rease Holocaust education for younger students. The success of our Hide and Seek program, developed with the support of Gandel Philanthropy, has resulted in extensive demand to provide programs for students in Years 6 to 8;

•an enlarged foyer and per manent exhibition spaces to accommodate increasing demand;

•flexible lear ning spaces to enab le the adoption of new technologies and more interactive learning styles;

•enhanced contemplation and memorial spaces;

•a dedicated temporary or spe cial exhibition gallery (enabling us to hold temporary exhibitions throughout the year); and

•an exp anded lib rary, res ource and res earch facilities.

8 JHC Centre News

To ensure that our project is carried out flawlessly and to the highest standard, we have established a Project Control Group (PCG) and a Board sub-committee. The PCG is chaired by leading Australian architect Alan Synman OAM, who has had more than 50 years’ experience in the design and delivery of major building projects. Award-winning architect Kerstin Thompson has been commissioned to design the building, the design process to be overseen by the JHC Executive. In addition, we are fortunate to have the support of Paul Kegen (JHC executive member and architect), Phil Lewis, George Umow and Simon Rubinstein, all of whom will sit on the PCG and provide vital direction and oversight of the redevelopment. Project manager Dean Priester will support the PCG team through the implementation phase.

We are exceptionally grateful for the voluntary support of such an experienced and talented team of people.

We shall continue to update you on this significant project as further details come to light, and look forward to bringing you on this journey.

JHC Centre News 9

View of the grand foyer through to the Garden of the Pillars of Witness and the Eternal Flame.

Artist’s impression of the Memorial Room featuring a light well.

Artist’s impression of a learning space in the new museum.

Resource Centre incorporating the library.

“The need for the new centre is a wonderful endorsement of the work we do.”

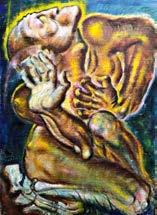

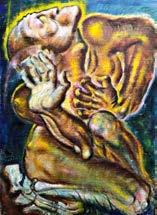

Not with ink, but with blood and tears

Genia Janover

Genia Janover

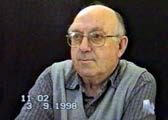

Yitzchak Meir Kluska came from a large traditional Jewish family in Jedrzejow, Poland. His occupation as furrier and tailor saved his and his younger brother Chaskel’s life when the Nazis occupied their town and they were assigned to forced labour. As the deportations which had already claimed their family continued, Yitzchak Meir and Chaskel went into hiding, entering a dug-out claustrophobic bunker which eventually harboured seven souls. During his two years in hiding, Yitzchak Meir kept a diary. This rare testimony, which captures the immediacy of his suffering, was recently donated to the Jewish Holocaust Centre by his daughter Genia Janover, and daughter-in-law, Judy Kluska, wife of Jack Kluska z”l.

Now within the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) Collection, this precious diary describes the singular and collective suffering experienced by Jewish people under Nazi oppression. It also provides evidence against the cynicism of Holocaust deniers who seek to minimise victim numbers and diminish their suffering. As such, it transcends its personal and family signi cance, and is an important contribution to Holocaust history.

-Dr Anna Hirsh, Senior Archivist

-Dr Anna Hirsh, Senior Archivist

10 JHC Centre News

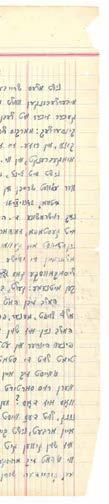

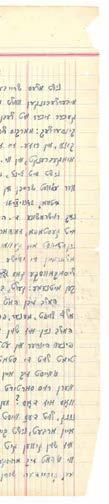

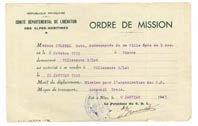

A page from Yitzchak Meir Kluska’s diary. The published version of the diary.

Photo: Romy Moshinsky

Ein kurtser iberblik fun mayn leben, nisht als shrayber, vayl kh’hob tsu dem keyn talent vi oykh nisht genug lere. Nor mayne iberlebungen volt ikh gern gevolt zoln blaybn far mayn liber shvester vos is gikher zikher mitn lebn. Zi ge nt zikh in Rusland mitn libn man, vi oykh mit di libe kinderlekh. Zey zoln visn vos is geshen mit der gantser familye ven men hot zey umbgebregnt vi azoy. Dos is mayn tsil.

A short overview of my life, not as a writer, because as a writer I have no talent and not enough education. But my life story I would dearly wish to leave behind for my beloved sister who is more likely to survive. She is in Russia with her dear husband and children. They should know what has happened to our family and how they were annihilated. This is my aim.

So begins our father’s journal, now yellow and faded with the passage of seventy years. These memoirs were penned during 1943 and 1944 in Jedrzejow, as he hid in a bunker dug beneath a chimney, in the house of a neighbouring Pole.

Yitzchak Meir Kluska was an ordinary man – kind, intelligent, loving, and proudly Jewish – yet he had also lived an extraordinary life. To us, his children, he talked only of the present and of the future – nothing of the past. As my brother Jack and I grew older we knew somehow, almost by osmosis, that he had endured terrible suffering and loss. At some point, we even knew that there was a journal written during his darkest days. But he never spoke of it. It seemed that his mind, his heart, his very soul had a need for silence. And we never asked.

After our father passed away in January 1990, we shared memories and stories, and pulled out the precious few photographs that he had guarded. And we took out the journal that lay haphazardly and unceremoniously in the bottom drawer of his desk in a simple brown plastic folder labelled with his name.

For many months translation became the evening ritual for Mum, Uncle Chaskel, Jack and me. Yitzchak Meir’s beautiful, even script belied unbearable pain. His words spoke out poignant grief and empty days, the passion of bleak despair. His writing admitted us to his inner life, something that he had never really allowed us. We saw his youth, his energy, his creativity, his idealism, his modern outlook on life, his disagreements and his political activism.

We were warmed by the love that he expressed for his wife, the romance of their courtship and his unbridled joy at the arrival of a child, Regina, on 3 April 1937. We also ached for his loss.

I still run back for us to say our goodbyes and to hug and kiss my dear wife with tears and also my dearest daughter. She asked me a question: Daddy, where are you going? The question of my daughter echoes in my ears never to be forgotten. Daddy, where are you going? I can no longer answer her.

We ached for his harrowing sense of guilt.

I convict myself and accept a murderous sentence. I should not have listened. I should have gone with my people, to be killed with my wife and child, with parents and sisters – the whole family – not to have remained with a broken heart.

Wednesday 16 September 1942 was the last time my father saw his family. He, together with some 200 men left behind, was taken to a barracks from where they would be assigned to forced labour. Sometime after, he learned the fate of his wife and daughter, that they had been murdered soon after arriving at Treblinka.

On 18 February, 1943... I had a dream that my dear wife came from somewhere and told me that it is the time to leave the barrack, it is dangerous to still be here… [On] 20 February, 1943, I entered the bunker… How can ve men manage in this place?! This [bunker] is the foundation of the hearth of a replace. The width is two metres, the length is 1.8 metres and the height three metres.

As we translated, we became familiar with names: aunts, uncles, cousins, neighbours. Their names, in our father’s hand, their only memorial. We reproached ourselves that we had not asked questions. Perhaps Dad wanted us to ask? Perhaps he wanted to tell us directly. We translated as best we could, some segments we just left blank. We discussed donating the diary, but were unable to part with it. It was a physical conduit to our father. We placed it in a safe with other valuable items.

Almost 20 years later, I was asked to speak about an object that informed my identity. My brother and I retrieved the diary and we were shocked at its condition. The writing had faded, and the paper was disintegrating.

This compelled us to consider how to safeguard the diary for future generations. Together we commenced a project to conserve the pages and undertake a professional translation. We also made the decision to donate the original diary to the Jewish Holocaust Centre, where it would be expertly cared for and could contribute to a greater purpose. Our father’s journal belongs to the collective memory. This forms part of his legacy.

Our father lived another 45 years after emerging from the bunker at the end of the war. He responded heroically to the challenging Biblical summons: And thou shalt choose life. He was thankful for his new life, his happy second marriage to Regina, a survivor of the Skarzysko forced labour camp. He had his children and the children of his children to live for.

Not with ink rather with blood and tears, should be written the Jewish story. Who will write and what will be written will pale against the reality.

Our father, Yitzchak Meir Kluska, set himself an onerous task – to make known his story – dos is mayn tsil – this is my aim. It is our sacred duty to complete his task.

JHC Centre News 11

Yitzchak Meir Kluska (r-) with his parents Sara and Wolf and his brother Chaskel (l).

Survivors remember the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

On the eve of Pesach 75 years ago, as the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto conducted their Seders, the Pesach themes of freedom and slavery surely could not have been more pertinent. On 19 April 1943 – also Passover Eve –the Nazis were preparing to liquidate the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto. With the vast majority of the Jews within the ghetto already having been sent to the Treblinka death camp or other concentration camps, the remaining Jews were not simply talking about freedom – they were doing so while living under the oppression of the Nazis.

To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising at the Jewish Holocaust Centre, we used the testimonies provided to the Centre’s Phillip Maisel Testimony Project to uncover what Melbourne Holocaust survivors witnessed. While these survivors were mostly children at the time of the uprising, and while their testimonies provide witness to the uprising, they also recall the conditions and daily life in the Warsaw Ghetto, beginning with its creation in 1939. Of course, as with any historical event, the survivors’ stories are each quite distinct, yet they also share certain aspects of the experience – including pain, suffering and luck.

Ella Prince (nee Zalcberg) was 13 years old when the ghetto was created. Ella provides testimony of the harrowing and tormenting

nature of the regular transports leaving from the ghetto, before which selections would take place and the chosen Jews would be sent to their deaths in Treblinka, or to further forced labour in concentration camps such as Majdanek. Ella notes, ‘It was always less and less people because the selections were more often.’ She witnessed this trauma personally, recollecting the day when her family was rounded up. She says, ‘The Germans from afar took away my brother from my father’s hand.’ They returned home that day ‘without my brother’. Only Ella and her mother survived the Holocaust.

Maria Lewitt (nee Markus) was 16 years old when she moved into the ghetto. Maria credits her mother with her own remarkable survival, as her mother believed that their options were either to ‘obey the Germans and then have their heads chopped off’, or ‘disobey them, do illegal things and risk having our heads chopped off’. Maria and her mother chose the latter, escaping from the ghetto in April 1941 and hiding on the Christian side of Warsaw with false papers, where her family continued to remain active in the underground resistance. She soon learned from the Polish Underground the ‘evil’ truth behind the transports from the ghetto, but says it was a reality that they ‘didn’t want to believe’. From outside the ghetto, Maria also provides a unique perspective in witnessing the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Maria describes seeing the ghetto in flames as ‘like Atonement Day for us’.

12 JHC Centre News

Sam Brygel

Jews arrested during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as photographed by the Nazis

Abram Goldman was 15 years old when the ghetto was established. His account stands apart from the rest as he was directly involved in the uprising. Abram, together with his brothers, who also took part in the uprising, states, ‘We decided not to go to Lublin (Majdanek), we decided to go into hiding.’ Instead of going to the Umschlagplatz (assembly point for Jews prior to deportation), Abram and others ‘got some ammunition, guns and things, which the Poles used to supply, naturally for a lot of money’. Consequently, as Passover Eve and the imminent liquidation of the ghetto by the Nazis approached, Abram describes that ‘we were getting prepared to fight against the Germans’.

Henryk Strosberg was a mere nine years old when the ghetto was created. He offers the raw and emotional perspective of a small, frightened child. However, it is perhaps not fear that is the most pervading emotion for Henryk, but rather confusion in trying to comprehend the extent of the evil taking place in his hometown. He vividly vividly recalls the hunger and starvation that permeated the ghetto, especially remembering ‘children, starving, dying in the street, just being covered by newspapers, and taken away’. Another event that stands out for young Henryk is the suicide of Adam Czerniakow, head of the Jewish Council of the Warsaw Ghetto. Upon understanding from his mother that ‘this is a very bad sign’, Henryk was prompted to ask his mother, ‘Why was I even born at all?’ This comment is chilling for its rawness, for it perfectly depicts the confusion of a young boy thrown into an unreal world filled with evil and suffering.

Halina Zylberman (nee Neuberg) was 14 when she moved to Warsaw in 1942. Like Maria, she also lived on the Christian side of Warsaw with false papers, and also offers a fascinating account. Referring to the cunning nature of the Nazis, Halina remembers that the ‘SS ordered them [the Jews] to sing… I thought it must not be so bad in the ghetto’. Later she realised this was part of their propaganda, pretending to the outside world that everything was fine in the ghetto. During the uprising and liquidation of the ghetto, Halina remembers the shameful

way in which the Polish children living nearby would play on the swings and ‘swing very high so they could see how the Jewish people were burning in the ghetto’. Moreover, Halina remembers how the children ‘were joking about it’.

Lusia Haberfield (nee Hasman) was eight years old when the ghetto was created. For Lusia, worst of all was her memory of being at the Umschlagplatz awaiting transportation to concentration and labour camps. Lusia states, ‘If there is a hell, somewhere, at all, Umschlagplatz was the hell.’ She describes scenes of women being raped, and the suicides of women who refused to succumb to this horror. In doing so, Lusia provides a perspective that is often left out of Holocaust memory, yet it is a perspective that is necessary to understand the bottomless depths of the torment to which the Jews were subjected. When her testimony moves to the uprising, Lusia’s face lights up noticeably as she remembers seeing the brave fighters who were so young. Describing it as a ‘miracle’, she affirms that we should be ‘so proud’ of the uprising and its heroic fighters.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is not remembered by Jews for its military victory, as such a reality was never even a possibility. Rather, it is remembered for the courage of the young people who, in holding out and fighting back for 27 days, ensured that it was the longest urban insurrection fought against the Nazis during the entire period of the Second World War. The uprising also inspired further uprisings in the Sobibor, Treblinka and Auschwitz concentration camps.

The remarkable oral testimony of the Melbourne Holocaust survivors who witnessed these events for themselves will ensure that the memory of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising lives on forever.

JHC Centre News 13

(l-r) Henryk Strosberg, Lusia Haberfield, Maria Lewitt, Abram Goldman, Ella Prince, Halina Zylberman

Sam Brygel completed an internship at the JHC, working on this film project with the Curator, Jayne Josem, and Audio Visual Manager, Robbie Simons, as part of his Arts degree at Monash University.

Jewish life in Germany today

Mark Dreyfus

In July, the Jewish Holocaust Centre hosted the travelling exhibition ‘Jewish Life in Germany Today’. The exhibition was brought to Melbourne by the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany in Canberra.

In 25 poster panels, the exhibition combined the historical and contemporary aspects of living as a member of the Jewish community in Germany. In concise and striking statements, Jews explain what living in Germany means to them, how the history of the Holocaust influenced their personal lives and the dreams they have for their future in Germany. From students to best-selling authors, to rabbis and entrepreneurs, their biographies reflect the diversity of the German-Jewish community today and are a testament to the transformation that Germany has undergone since the Second World War.

The exhibition was opened by the Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP. This is an edited version of his address.

It is a pleasure to be here to launch this wonderful exhibition, and to have the opportunity to reflect a little about what this exhibition represents: a kind of Jewish renaissance in a nation that was a place of great importance to Jews, until the horrors of the Nazi regime and its aftermath cast a shroud of darkness over Jewish life there. Because what this exhibition makes so clear is how Jews and Jewish life is once again flourishing in Germany. And that is a wonderful thing to be able to say.

The story this exhibition tells is a story of importance to Jews the world over, and to very many, if not all, Germans. It is a story like so many in Jewish history that is about hope, about resilience and about renewal. And it is a story to which I have a very strong personal connection. It is my father, George Dreyfus, who should be giving this talk because he has had much more contact with Jewish life in Germany today than I have. I have visited Germany, but my father has returned there every year or two since about 1951. In doing so, he has participated in a very real way in making sure that there has been a renewed Jewish presence, including many performances of his compositions – including an opera or two – in Germany.

My father and his parents escaped from Nazi Germany, my father before the war, arriving in Australia with his brother, the late Richard, in July 1939. My father’s parents, my grandparents, arrived, some three months after the war started, in a somewhat miraculous escape from Germany. My great grandparents did not. They perished in the Holocaust.

14 JHC Centre News

Top right; (l-r) David Prince, the Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP, Abram Goldberg OAM and the Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP

Top left; Susanne Koerber and the Hon Mark Dreyfus

I have a continuing connection to Germany because all three of my children have taken up German citizenship, not because they have gone to live in Germany but because it is possible for children and other descendants of survivors to take up German citizenship, under a law of return that Germany has made possible.

I think we are all aware of the enormous contribution that German Jews have made to both Jewish and Western thought over the centuries. One could point to intellectuals like Moses Mendelssohn, Rabbi Abraham Geiger, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and Zacharias Frankel. All had a very significant impact on Jewish thinking and on our religious traditions. You could also point to German Jewish scientists in fields including physics, chemistry and medicine who have had a huge impact on the world, perhaps none more so than Albert Einstein. And in many other fields, as this exhibition reminds us with notes and images of Mayer Rothschild, Kurt Weill, Hannah Arendt, Max Liebermann and others.

Some of the statistics that are included in the exhibition tell the story of Jewish life in Germany with a stark simplicity. Around half a million Jews lived in Germany when the Nazis came to power in 1933. I will not dwell on this, the darkest chapter of Jewish history in Germany, other than to say around 300,000 Jews had left by 1939, a few thousand more managed to escape after the Second World War had started, but around 180,000 German Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, along with millions of others throughout Europe. The enormity of this crime, this loss, this horror, like so much of the Holocaust, can be stated, but not truly comprehended.

Yet the unspeakable enormity of that horror also underpins the remarkable story that this exhibition tells. And the fact that the Jewish community is once again thriving in Germany, still in living memory of the most appalling crimes against it, also speaks of the willingness of German society to confront the demons of its past. Because only by confronting the past has German society been able to make the heartfelt commitments needed to truly welcome Jews back into the German nation, and for Jews to trust that welcome.

At the beginning of the 1950s there were not more than 25,000 Jews living in the Federal Republic of Germany, and only a few hundred in the German Democratic Republic – at least only a few hundred willing to be identified as Jews to that German government. These figures did not change much over the coming decade, so that by 1990, there were still only around 30,000 Jews living in West Germany.

However, then things changed. Through the 1990s and the early 2000s, more than 200,000 Jews and their family members immigrated to Germany from the collapsing Soviet Union. Many were on their way to other nations but many stayed, so that now up to 200,000 Jews are living in Germany, with Berlin again the largest of those communities.

Indeed the Jewish community in Germany is now the eighth largest in the world and it continues to grow and flourish. I find it very heartening that thousands of young Israelis spend time in Germany – some for years – particularly in Berlin. And I also find it heartening that the state of Israel finds a loyal friend in the Federal Republic of Germany.

This exhibition provides a beautiful tapestry of how the flourishing Jewish community in Germany now looks. The diversity of the Jews that are represented tells us that there is a vibrant Jewish life in Germany today.

JHC Centre News 15

The Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP is the Federal Member for Isaacs, Shadow Attorney-General and Shadow Minister for National Security.

(l-r) The Hon Mark Dreyfus QC MP and George Dreyfus AM

Failing to Understand Failure: Reassessing the Evian Conference of 1938

The Evian Conference took place in the resort town of Evian, France, between 6 and 15 July 1938. Formally named the ‘Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees from Germany (including Austria)’, it met at the invitation of US President Franklin D Roosevelt to discuss, in depth, the immigration policies of invited nations and their options for accepting refugees from Nazi Germany. The countries attending were not expected in any way to depart from their existing policies. When the meeting’s final recommendations were made no definite action was proposed – only that the deliberations should continue and a subsequent meeting should take place in London.

The major objective of this global conference was to do nothing. It was successful in achieving its fundamental aim of enabling an exchange of information among those attending, and nothing more. Contrary to what has become post-Holocaust popular wisdom, the delegates did not meet to open doors for refugee Jews, or force certain countries to ease their restrictions, or save Jews from the Holocaust. In 1938 there was, as yet, no Holocaust from which Jews needed saving.

There was, however, a refugee crisis and consequently, many nations were confronted with a situation that has many parallels with our own time.

Questions abounded: Should an opendoor policy be permitted for anyone claiming refugee status? Should quotas be imposed, and, if so, how are the decisions to be made as to numbers and eligibility? Should refugees be permitted entry on a short-term, long-term, or permanent basis? Should they be allowed in regardless of the prevailing economic situation? Should refugees of a different religious or ethnic background be given the opportunity to arrive? Should they be allowed to stay, thereby potentially transforming the existing social and/or ethnic fabric? The issues in 1938 (as today) were many, and the need to deal with them urgent.

An analysis of Roosevelt’s invitation reveals the following features: no particular ethnic, political or religious group

should be identified with the refugee problem or the calling of the conference; nothing should be done to interfere with the operations of existing relief bodies; all assistance for refugee work should be drawn from purely voluntary sources; and no nation should be required to amend its current immigration laws to accommodate the refugees.

The agenda would be set by the US government, and the conference would be dominated by three men: Myron Taylor from the United States, Edward Turnour (6th Earl Winterton) from Britain and Henry Bérenger from France. During their presentations, each stated essentially that they were far from prepared to do anything that would expand Jewish refugee immigration to their countries. The United States said there would be no expansion, only a merging of the existing German and Austrian quotas; Britain said that there would be no discussion of Palestine or the colonial Empire; and the French stated that they had already taken enough ‘aliens’ and were ‘saturated’.

This gave a lead to all the other countries, as they too made their presentations. Analysing the addresses made by delegates it becomes apparent that often they did not have prepared instructions from their governments, and they made things up on the spot. They acted safe in the knowledge that they were interpreting faithfully their governments’ views. This was therefore a gathering of representatives who projected a comprehensive perspective of official reactions to the refugee crisis. It is not a pretty picture. Grouping them into blocs, we see several themes for each.

The Europeans were concerned about the possibility of supplanting the League of Nations High Commission for Refugees. They expressed a preference that the United States and other countries outside Europe should begin accepting a greater share of the burden. The European countries were only were only prepared to accept refugees for temporary asylum in a short-term transit capacity and, although there was much sympathy, no country could play an active role in facilitating refugee resettlement.

16 JHC Centre News

Paul R Bartrop

“ “

The major objective of this global conference was to do nothing. It was successful in … enabling an exchange of information among those attending, and nothing more.

The Latin Americans, the largest group of states, were all keen to align with President Roosevelt’s call to link arms in a joint effort to ease refugee distress, and recognised that the refugee crisis was a humanitarian disaster. However, refugees would only be admitted in accordance with their existing laws; only those engaged in farming would be admitted; no special financial arrangements would be made to assist refugees; and any migration would have to proceed without any detriment to local workers. The Latin American states believed that the United States or the European nations should pick up the slack in solving the refugee issue. They also made it clear that urbandwelling professionals and intellectuals were not wanted.

The (self-governing) British dominions shared a sense of being able to take charge of their own affairs without interference from Britain, and stated that they had neither an interest in – nor a serious desire to help resolve – the refugee problem. Canada only wanted farmers; New Zealand did not want foreigners; Ireland, which had not originally been invited but went anyway, did not see itself as an immigrant-receiving country; South Africa did not attend; and Australia …?

Australia was represented by the Minister of Trade and Customs, Sir Thomas White, whose speech was largely the same as those of everyone else. He stated that ‘Australia has her own particular difficulties’. and that, were migration play any part in easing those difficulties, the only type that could be countenanced was British migration. Recognising ‘the unhappy plight’ of Jews in Germany

and Austria, White explained that ‘they have been included on a pro rata basis, which we venture to think is comparable with that of any other country’. He added that, ‘Under the circumstances, Australia cannot do more, [and] as we have no real racial problems, we are not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large-scale foreign migration’.

As no nation could foresee the Holocaust, the sense of humanitarian urgency was less pressing than it would become in later years. And therein lies a major element embedded within any assessment of the refugee problem in Europe prior to the outbreak of war in September 1939: every country in the world was formulating and administering an immigration or refugee policy – not a rescue-from-the-Holocaust policy. No one holding senior office during the 1930s, in any major state (including Nazi Germany), envisaged the Holocaust that would emerge within 18 months of the outbreak of war. Thus, when it came to addressing the situation at Evian, the only concrete proposal was to keep on talking, while at the same time not compromising the direction in which governments had already been heading.

Historians cannot see around corners, and no truer claim can be made than that our long distant past was, once upon a time, someone else’s far distant future. This is the same trap into which historians and other commentators have since fallen when looking at Evian. The refrain ‘they should have foreseen what was coming’ just does not work.

JHC Centre News 17

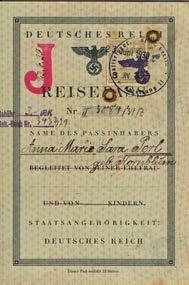

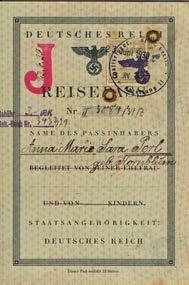

German Reich Passport issued to Anna Marie Sara Perl (nee Kornblum) in June 1939 and stamped with the letter ‘J’ to signify that the bearer is Jewish.

Lilo Nassau desperately walking with her son from embassy to embassy seeking immigration permits for her family after her husband was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Source: JHC, courtesy of Lilo Nassau

That said, there were a number of areas in which the Evian Conference, when measured against the standards of 1938, was clearly deficient. Even if the Holocaust could not have been foreseen, the possibility of war was evident, but at Evian there was no discussion of what would happen to the Jews of Eastern Europe should Germany embark on a war of conquest and thereby increase the number of Jews under Nazi rule. The conference never managed to resolve the points of crossover between the League of Nations High Commission, other refugee bodies and the conference, and it failed to suggest any sort of financial arrangements for the refugees. Nor, shamefully, did the delegates even agree to condemn the Nazi antisemitic persecution that led to the refugee crisis in the first place; in a climate of high appeasement, that issue was not even raised. These were all within the conference’s remit as targets that could have been met, but none ever was.

One person, however, saw through the conference rhetoric. At an official level, no one else, it seems, was as insightful as Adolf Hitler, who assessed Evian better than anyone else at the time. The Nazis realised that the conference was focused more on looking good than on actually doing anything of a definite and lasting nature, and saw that it was about saving the reputation of attending countries rather than Jews. In a speech at the Nazi Party rally at Nuremberg on 12 September 1938, Hitler made explicit the connection between Roosevelt’s calling of the conference and his attempt to deflect attention away from an otherwise unhelpful American policy.

One final, key question needs to be asked: could the Evian Conference have made a difference to the events that were to follow? The best answer is only … perhaps. Evian could have acted as an occasion for caring administrations to voluntarily agree to increasing their refugee or immigration intakes. However, questions of realpolitik, racial and population preferences, antisemitism, economic priorities and other factors led to a collective rejection of any liberalisation in favour of Nazi Germany’s unwanted Jews. No other outcome was ever likely, and the hopes of many were consequently misplaced and unrealisable.

Therefore, is it legitimate to refer to Evian, as many have done in light of the Holocaust, as a ‘failed’ conference? I do not think so. After all, it lived up to the terms of Roosevelt’s original invitation and, as a result, delegates stated that their countries were actually doing quite a lot for refugees, while at the same time demonstrating that they could do no more and were not prepared to try. In what was a classic case of ‘virtue signalling’, the assembled countries used the opportunity to look good, but the refugees gained nothing.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the word Evian, when spelled backwards, reads ‘naive’, for that is precisely what the conference was. A cynical attempt to deflect attention from otherwise unhelpful policies on a global scale, for the Jews of Germany and Austria – and in the public consciousness ever since – the stakes for the Jews of Germany (and then Europe) were frighteningly high, confronting a regime that cared nothing for the standard conventions of international behavior and a community of states that cared little for the fate of the people they had come together to discuss. If there was any failure, it was a failure of imagination – both on the part of the countries attending and those hoping that some other outcome would be possible. Evian must be viewed through the lens of its initiation in March 1938, rather than the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

It is therefore heartbreaking that ever since Evian there has been a constant narrative that begins with the words ‘the failure of the Evian Conference’. Yet if its failure lay in the fact that the delegates did not foresee Auschwitz, they were not alone. No one in 1938 could have done so; more is the pity.

After Evian, but prior to the German attack on Poland precipitating the outbreak of war, many events further reduced options for the Jews of Germany. These included the establishment of a Nazi Office of Jewish Emigration to speed up the pace of Jewish emigration from Germany (1 August 1938); the requirement that Jewish women add ‘Sarah’ and men add ‘Israel’ to their names on all legal documents (17 August); the closure of Swiss borders for Austrian Jews seeking sanctuary (19 August); the Munich Agreement in which Britain and France surrendered the Sudetenland regions of Czechoslovakia to Germany by negotiation (29–30 September); the compulsory stamping of passports belonging to German Jews with the letter ‘J’ to indicate their identity (5 October); the Kristallnacht pogrom throughout Germany and Austria (9–10 November); the German invasion of what remained of Czechoslovakia (15 March); and the return to Europe of the SS St Louis , a ship carrying 936 Jewish passengers, after being denied entry into Cuba and the United States (17 June). Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939; Britain and France declared war on Germany two days later.

While it is true that before Evian there were no mass deportations or large-scale brutal assaults against Jews, it is equally true that these began in increasing measure after Evian. Were these in response to the nations of the world turning their back on the Jews in July 1938? Ascribing too much to a Nazi grand plan leading to the Holocaust is dangerous; as stated earlier, no

18 JHC Centre News

“ “

At an official level, no one else, it seems, was as insightful as Adolf Hitler, who assessed Evian better than anyone else at the time. The Nazis realised that the conference was focused more on looking good than on actually doing anything of a definite and lasting nature …

Arrival of Polish Jewish refugees in London, February 1939

Australian landing permit for Herbert and Ilse Lippman dated 28 November 1938

one at Evian could anticipate what would happen next, and Nazi policies did not foresee the events to follow. There could be no escaping the fact, however, that even in July 1938 the Jews of Germany were in desperate straits, or that the states represented at Evian displayed little other than apathy and disregard over their ultimate destiny.

The years following Evian should have broadened humanity’s horizons. How far that rings true today is for another generation to judge, but considering Evian they will have a template upon which to rest their considerations.

Two quotes exemplify the relevance of the Evian Conference for the present: Rabbi Hugo Gryn, a Holocaust survivor who became one of the leading spiritual leaders in the United Kingdom wrote in his memoir, ‘Time is short and the task is urgent. Evil is real. So is good. There is a choice.’ And Elie Wiesel stated, ‘The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. The opposite of beauty is not ugliness, it’s indifference. The opposite of faith is not heresy, it’s indifference. And the opposite of life is not death, but indifference between life and death.’

This is an edited version of a public lecture presented by Professor Paul R Bartrop at the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC). Professor Bartrop is Professor of History and Director of the Center for Judaic, Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Florida Gulf Coast University, Fort Myers, Florida, United States. He is currently a Visiting Fellow at the JHC.

JHC Centre News 19

Source: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-S69279 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Anita Selzer

in conversation with Lisa Phillips

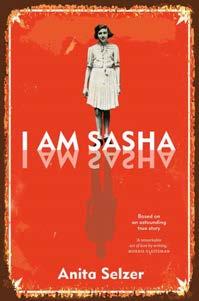

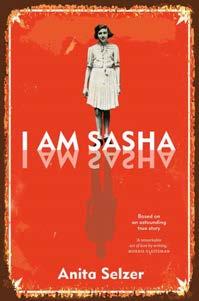

Anita Selzer is a Melbourne-based author who writes non-fiction for children and adults. Her book, titled I Am Sasha, was published recently. Here she is in conversation about the book with Lisa Phillips, the Jewish Holocaust Centre Education Director.

LP: Why did you decide to write this story?

AS: In 1994, before my grandmother passed away, she handed me a manila folder with Ioose Ieaf pages in it. In it she wrote, ‘The story of how your father and I survived the Holocaust is in this file. I want you to tell the world how we did. You are becoming a writer with a book already published. Please write and publish our story. Promise me.’ I wrote I am Sasha to honour her wish and leave my children a tangible record of their legacy. I would not have thought to write the story if she had not asked me. It was a part of my father’s life that he really did not want to discuss.

LP: You had your grandmother Larissa’s memoir and a short story written by your father. Could you tell us about what they contained, when they were written, and what other research you had to do to write I Am Sasha?

AS: The pages in Larissa’s memoir were written in blue biro, spanning the years of her life. While her mother tongue was Polish, the memoir was written in English, in post-war Melbourne. It focused on her family life, meeting and marrying my grandfather, losing him, and life during the war and postwar years.

In Melbourne in 1966, my father had typed a short piece about his life during the war entitled ‘A Magnificent Deception’. lt begins in 1941, describes various incidents that are recorded in my grandmother’s memoir, and mentions how he had survived disguised as a teenage girl. Dad had submitted this story for publication without success. I think the time was not right then, and his rendition did not include how he had felt or thought about being a teenage girl. What his writing told me, however, was that Dad wanted his story shared with a wider audience.

As I wanted readers to feel as if they were there on the journey with Sasha and Larissa, I had to do extensive research, so I gathered information about pre-war Poland, the Second World War, the Holocaust, other survivors’ experiences, and the places in which my father and grandmother had lived and visited.

20 JHC Centre News

(l-r) Anita Selzer and Lisa Phillips

LP: The historical detail is a strength of the book, which makes it an excellent educational resource. You describe the rich Jewish world that existed before the war; the death camps, which you refer to by name; the mobile Einsatzgruppen and their role in the destruction of the communities; the Jewish councils known as the Judenrat; the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising whose 75th anniversary we have recently marked; and you even had Sasha reading Janusz Korczak’s books for children. How did you decide what information to include and what to exclude?

AS: Initially, it was daunting to decide what information to include and exclude in the book. I wanted to write more than the story of my family’s survival, so it was important to include the historical context. I felt the need to paint the bigger picture of war and educate readers about it, especially for young adult readers, and adults who may not know much or anything about the Holocaust.

I wished there to be shades of light and dark in the book, to show love, kindness and hope, as well as the horror of war. Other themes in the text are racial and religious identity; gender identity; adolescence and puberty; racism, inhumanity and human rights; truth and deception; hiding; choice and chance; friendship and trust; cruelty; tolerance and acceptance; loss and displacement; and immigration. There are probably more themes woven through the text that I hope readers will enjoy discovering.

I wrote hoping that readers would have a visual experience –that they are able to see the story unfolding through the text. Above all, for me, I Am Sasha needed to be as authentic as possible. The memoir and photographs are primary sources

–historical evidence that authenticates both the story and moments in history. That is why I included excerpts from the memoir along with photographs. Sasha reading a book like Janusz Korczak’s work was also a conscious choice to include as an example of what was read by young people at that time.

I chose to exclude some historical information in telling the story of Sasha’s survival, Larissa’s early family life and her life with her husband, as I felt the focus needed to be on Sasha and his journey. That is why I wove the history seamlessly into the story, rather than having it stand out as a history lesson. I also felt that the text would have been too long had I written more detail about the war.

LP: What were some of the challenges you faced when writing I Am Sasha?

First, writing in the voice of a young boy who is telling a story was challenging, as I had not done this before. My preceding nine published books were in the area of Australian history and biography. Imagining Sasha’s feelings and thoughts was a second challenge, as I had never discussed these with my father. He did not talk about the war, only to say, ‘Every day I got after the war was a bonus because I was destined to die.’ I needed to imagine his thoughts and feelings. Perhaps raising two sons enlightened me somewhat about the psyche of an adolescent boy. And thirdly, finding the right publisher and ‘home’ for I am Sasha was a long road, which required faith and perseverance.

Originally, I wrote Saving Sasha in my grandmother Larissa’s voice in 2013. That was challenging because I had never written a novel before. A year later, I submitted the manuscript to publishers. Although there was considerable interest, I was not convinced that the offers made to me were the right ones, so at that stage I felt disheartened. Eventually, however, I was advised to re-write the story in Sasha’s voice and tell the story from his point of view. I did this with reluctance, but it was the right strategy, as the new manuscript was accepted by Penguin Books. I felt I had now found the right home for I Am Sasha, as the publishers understood the emotional resonance of the story.

LP: What m essages would you like those reading I Am Sasha to gain?

AS: Toler ance and acceptance of different races and cultures is an important message, along with the promotion of global peace, love and kindness. We need to remember that we are all the same, made of flesh, blood and bone. We also need to reflect and recall the inhumanity of Adolf Hitler and his regime and say ‘never again’.

I would like readers of I Am Sasha to understand that gender is not necessarily fixed, but rather can be fluid, enacted, practised and contested. Gender is part of a becoming and, to a large extent, a performance. As existential philosopher Simone de Beauvoir has said, ‘One is not born, but rather becomes a woman.’ And this is influenced by choice – like the reluctant, but lifesaving one made by Sasha as a teenager in I Am Sasha.

JHC Centre News 21

Jewish Rescuer Citation awarded to Ronia

Rozental

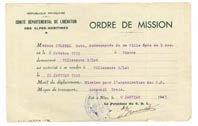

In April 2018, the late Ronia (Rone) Rozental was awarded the Jewish Rescuer Citation. The B’nai B’rith World Center in Jerusalem and the Committee to Recognize the Heroism of Jews who Rescued Fellow Jews During the Holocaust (JRJ). created the Jewish Rescuer Citation in 2011 to honour Jews who rescued other Jews, and to highlight Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. To date, almost 200 rescuers have been recognised. They were active in France, Hungary, Greece, Germany, Slovakia, Yugoslavia, Poland, Ukraine, Italy, Latvia, Austria and Holland, and all put their own lives in jeopardy to help other Jews under Nazi rule. Ronia Rozental was the rst Jewish rescuer from Lithuania to be awarded the Jewish Rescuer Citation. She had been previously awarded the Saviour Cross by the Lithuanian Government in 1993 – the only Jew to have received that honour.

Ronia and Shmuel Rozental lived in Kovno (now Kaunas) with their son Leo before the Nazi occupation. Shmuel was the principal of the Shalom Aleichem School and Ronia was the director of the kindergarten teachers’ training college. Some of her students were nuns.

The Rozentals, together with all the Jews of Kovno, were forced to move to the Kovno Ghetto in June 1941. Ronia and Shmuel’s daughter Rona (now Rona Zinger) was born in the ghetto in 1943. As the Nazis had issued an order making pregnancy illegal for Jewish women, Ronia had to conceal her pregnancy, and after Rona was born, Shmuel created a special hiding place in which to hide her and her cousin Lusi, who was also born in the ghetto.

Although education for Jewish children was banned in 1942, Shmuel taught in the Yiddish underground school established in the ghetto, and he also forged identity documents. Ronia’s role in the underground organisation was to rescue Jewish children. She used her pre-war contacts with student nuns to arrange hiding places for children in a monastery, an orphanage, and with Christian families. With her green eyes and dyed blonde hair, she looked Aryan and came in and out of the ghetto without wearing the yellow Star of David that was mandatory for all Jews.

In 1943, Shmuel smuggled Leo out of the ghetto in a sack of potatoes and he was hidden in a tiny space under a stove by a poor farming family. Rona was also smuggled out of the ghetto and hidden by a gentile couple. Baptised and named Lily, she lived with her foster parents until she was six. Shmuel, Leo and Rona survived the war, but Ronia was murdered in Stutthof Concentration Camp. Shmuel was liberated from Dachau Concentration Camp and was nally reunited with his daughter in 1949, when he renamed her Rona, after her mother.

Ronia Rozental’s award in recognition of her actions in rescuing Jews during the Holocaust was presented during a moving Yom Hashoah ceremony at the Gvillei Esh (Scrolls of Fire) Square in the Forest of Kdoshim (Martyrs Forest), Israel. The medal was accepted by her granddaughter, Maya Rozental.

22 JHC Centre News

Jewish Rescuer Citation awarded to Ronia Rozental

Ronia Rozental, Kovno 1936

Maya Rozental (front row 2nd right) with Ronia Rozental’s Jewish Rescuer Citation

Lowicz: a city sentenced to death

Michaela Glass

My grandfather, Zigmund Glass, was born in Lowicz, Poland in the early 1920s. In 1939 he ed to escape the Nazis with two of his three brothers, Jerzy and Marek. They travelled from Russia to Japan and then sailed to Canada. In Canada, Zigmund and Marek enlisted in the Air Force. Like many other Polish refugees, they were sent to England join the RAF. Both brothers served in the Bomber Command during the Second World War. Marek was killed in battle. Zigmund survived and ultimately settled in Inverness, Scotland, where he married Doreen Gordon.

This is the story of my grandfather’s hometown. Lowicz is half way between Lodz and Warsaw. Jews had lived there since the 14th century. Before the Shoah, Lowicz was a sleepy town. It came alive with peasants from the surrounding villages on market days.

Lowicz had a synagogue and a kehillah. The Jewish community opened a public Jewish library in 1906. After the First World War, one quarter of Lowicz’s population was Jewish. The Jews worked mostly as artisans or academics.

The Lowicz Jews were diverse. There were intellectual, Zionist and Socialist groups, as well as an active youth movement. Lowicz was one of a few small towns even to have its own Yiddish weekly, the Mazowsher Wochenblatt.

Throughout the ages, Lowicz had been protected by the Bzura River. The river wrapped around the city, creating two islands. These were used as defensive outposts to keep the city safe. Until the Nazis came.

On 1 September 1939, seven Nazi planes bombed Lowicz from the air. The Nazis quickly occupied the city, and burned down the synagogue which had been the pride of the Jewish community since 1887. Their next project was to destroy the Bzura River.

The Nazis ordered the Jews to create walls in the river, redirecting the water away from the city. This would make it easy for German armies to enter on foot. They never wanted Lowicz to be a Jewish ‘fortress’ again.

The Lowicz Jews thought that working for the Nazis would spare them their lives. They had no idea that by diverting the river they were eliminating any chance their community had of surviving.

The Nazis established the Lowicz Ghetto, the rst in the Warsaw district. They also created a Ghetto Police who would ensure a constant supply of workers. Three hundred Jewish slave labourers were sent to build the river walls daily. These merchants and members of the Jewish intelligentsia had no experience of

physical labour. They were fed small bread rations and thin soup in exchange for their work.

Survivor Gedaliah Tcharneson-Shaiak said, ‘They died like ies, weakened, famished and exhausted.’ Nazi soldiers ordered the workers to use thousands of Jewish tombstones to strengthen the wall. In four months, they built a wall six metres high and 10 kilometres long.

With their ancestors’ tombstones under water, their synagogue burnt down and their population starved, the Lowicz Jewish community had been spiritually and physically destroyed. The Lowicz Ghetto was liquidated in 1941. During the Shoah, 18,000 Lowicz Jews were murdered. Many members of this once-thriving community had even been forced to dig their own graves.

Michaela Glass is a journalism student at Monash University and the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor. She was the 2018 recipient of the Irene and Ignace Rozental Internship and interned at the Jewish Holocaust Centre in July 2018. She is researching survivor testimony, focusing on the experience of Polish Jews during the Shoah.

JHC Centre News 23

Zigmund and Doreen Glass

Zigmund Glass in his RAF uniform

My Holocaust memorial year abroad at the Jewish Holocaust Centre

As a young Austrian, one has to choose between two types of conscription: Armed Forces or Civil Service. Few know about the third possibility of doing Memorial Service abroad. For me, however, it was immediately clear that this would be my choice. After doing some research, I chose the Jewish Holocaust Centre (JHC) as it is one of the last Holocaust memorial institutions where one can still actively work with survivors of the Holocaust, and I am part of the last generation who can sit with survivors and listen to their stories. Despite the enormous amount of preparation involved and the demanding project in which I was involved, I would never have wanted to miss the experience I have had.

When I rst arrived, I was introduced to JHC employees, volunteers and survivors, and attended school programs during which survivors spoke to students. My rst projects were working with the audio/video producer and curatorial department to create online portfolios on the video platform Vimeo, to be used for marketing. I also help install a new video camera system in the JHC large auditorium to simplify the process of lming events.

In the archives department I learnt about the cataloguing and archiving of documents and artworks. I also translated documents from German to English, ranging from a 40-page account written by a Holocaust survivor to the documents in the Marcuse collection. Ernest Marcuse was a Berlin artist of Jewish descent who immigrated to Australia shortly before the war, and the collection includes numerous technical drawings, many of which are amazingly futuristic.

As I have training as an event technician, I participated in the planning and staging of events. My role involved photographing and lming events, as well as ensuring that the sound and set-up of the facility were appropriate.

I took part in the Hide and Seek education program by helping students with the correct pronunciation of German names and addresses, as well as ensuring that the program ran to schedule. I was also involved in the digitising of comments left by students on a noticeboard at the end of their visit, so that this valuable feedback can reach a wider audience.

By far the most demanding and time-consuming project in which I was involved was the compilation of an inventory of the entire JHC, in preparation for the Centre’s redevelopment. My task was to count, label and list every single item in every room so that items can be packed and moved. I was also entrusted with

administrative tasks, including answering telephones, shopping for supplies and doing simple repair work.

It was a great honour to represent the Austrian Ambassador at a prestigious event, but the most important and memorable part of my time at the JHC was my daily interaction with Holocaust survivors, and the lifelong memories I will have as a result.

Now that my 10-month placement is over, I have absolutely no regret about my decision to complete my Memorial Service at the JHC, and I am sure that the experiences I have had and skills I have learned will be of great help in my future working life. I thank my colleagues, and the volunteers and survivors for their help and support.

24 JHC Centre News

Julius Sevcik

Julius Sevcik

Hope for a better future

In June, author and journalist Julie Szego launched Hope for a Better Future, by Sarah Saaroni OAM. This memoir is a sequel to Sarah’s autobiography Life Goes on Regardless... (Hudson Publishing, 1989), which focused on her childhood in Lublin, Poland, her story of survival during the Holocaust and her journey rst to Palestine (now Israel) and then to Australia.

The sequel takes the reader on Sarah’s life journey after the Holocaust. Sarah’s personal victories in Israel were overshadowed by ongoing nightmares triggered by the Holocaust and the hardships of daily life. Uprooted yet again and resettling

in Australia, Sarah quickly discovered that even in a nation of peace and prosperity life was not without its vicissitudes. However, she discovered catharsis from her Holocaust trauma through creative expression, family and involvement in the Jewish Holocaust Centre.

Sarah Saaroni’s memoir is a story of courage, determination and resilience. It is available at the Jewish Holocaust Centre, email admin@jhc.org.au or phone (03) 9528 1985.

Phillip

Maisel

Testimonies Project

The Jewish Holocaust Centre has over 1,300 video testimonies as well as over 200 audio testimonies in its collection. These provide eyewitness accounts of the horrors of the Holocaust, as well as glimpses into the vibrancy of pre-war Jewish life in Europe. The collection is widely used by researchers and students of oral history, the Holocaust and a variety of other disciplines.

If you would like to give your testimony or know of someone who is interested in giving a testimony, contact Phillip Maisel. Phone (03) 9528 1985 or email testimonies@jhc.org.au.

JHC Centre News 25

(l-r) Tosca Mooseek, Sarah Saaroni OAM, Dorothy Saaroni and Rae Silverstein

(l-r) Maria Lewitt OAM and Sarah Saaroni OAM

Keeping their memories alive

Vivienne Dacey

Twelve thousand people participated in this year’s March of the Living (MOTL) and our international group comprised 45 Australians and 45 others from around the world. Going on MOTL was a decision I made without too much hesitation. I had been to Poland many years ago, so I knew that what I was going to see would be difficult, but I did not anticipate the impact it would have.