JGM GALLERY ACKNOWLEDGES THE TRADITIONAL OWNERS AND CUSTODIANS OF COUNTRY

THROUGHOUT AUSTRALIA AND RECOGNISES THEIR CONTINUING CONNECTION TO THE LAND, WATERS AND SKIES, OFTEN EXPRESSED THROUGH ART.

WE PAY OUR RESPECTS TO ARTISTS, ELDERS AND COMMUNITY MEMBERS PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE.

Small Archer River - Alair Pambegan’s Country, 2021. Image courtesy of Gabriel Waterman.

1 2

JGM Gallery

summer 2024

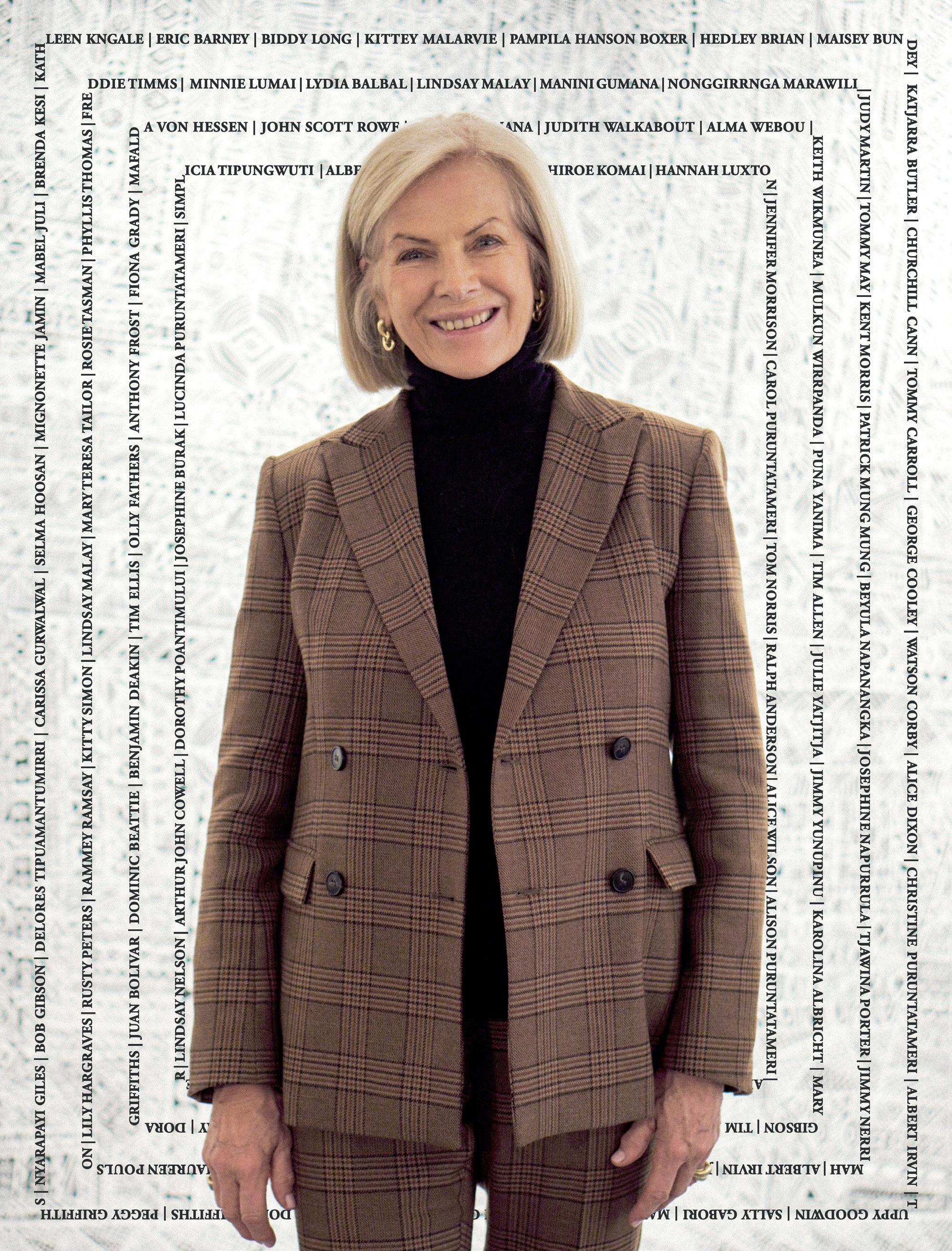

DIRECTOR

Jennifer Guerrini Maraldi

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR

Julius Killerby

MANAGER OF MARKETING, COMMUNICATIONS & LOGISTICS

Heidi Pearce

GALLERY ASSISTANT

Antonia Crichton-Brown

GALLERY ASSISTANT

Chloe Redston

CONTRIBUTORS

Antonia Crichton-Brown

Ashraf Jamal

Chloe Redston

Dominic Beattie

Guy Allain

Hubert Pareroultja

Julius Killerby

Ken McGregor

Mafalda von Hessen

Olly Fathers

3

Weer Loo - The Cry of the Curlew

Julius Killerby explores conceptual and compositional hybridity within the Hermannsburg School of Art, and within Hubert Pareroultja’s work specifically. The text is accompanied by an ‘In Conversation’ with the artist, his biographer, Ken McGregor, and Killerby himself.

15

In Conversation with Mafalda von Hessen

In the weeks preceding Looking In (24 April - 25 May 2024) an exhibtion of works by Mafalda von Hessen, Chloe Redston sat down with the artist to discuss her upcoming show. The conversation was an opportunity to examine von Hessen’s work, its context, and the thoughts and processes surrounding it.

27 Gestures of Tiwi Abstraction

To accompany Yoi ( 21 February - 13 April 2024 ), an exhibtion of works from the Munupi Arts & Crafts Association, Chloe Redston explores the interconnectivity of the visual arts, music, dance and Country in Tiwi culture, and the subsequent nature of Tiwi abstraction.

35

In the Studio with Dominic Beattie & Olly Fathers

In the weeks preceding Tangram (25 October - 2 December 2023), Julius Killerby visited Dominic Beattie and Olly Fathers in their London studios. The visits were an opportunity for both to discuss their work and the collaborative exhibition.

43

Ngurra: Libraries of Knowledge

Using and developing on Stephen Gilchrist’s analogy of the ‘library’ as a means of interpreting Indigenous knowledge systems, Antonia Crichton-Brown examines a cultural relationship to Country as an act of translation.

49

Static Flow: Art at One Creechurch Place

For the fourth installment of Art at One Creechurch Place, Jennifer Morrison presents six new paintings, a series which sees large, euphoric loops, bursting with colour on monumental canvases. In an essay published alongside the exhibition, Ashraf Jamal explores the mysteries and revelations in these works.

review vol. iV

TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. Iv

1 2

weer loo: the cry of the curlew

PRODUCED ON THE OCCASSION OF HUBERT PAREROULTJA’S EXHIBITION, WEER LOO - THE CRY OF THE CURLEW , THE FOLLOWING ARTICLE BY JULIUS KILLERBY (JGM GALLERY’S ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR) EXPLORES CONCEPTUAL AND COMPOSITIONAL HYBRIDITY WITHIN THE HERMANNSBURG SCHOOL OF ART, AND WITHIN PAREROULTJA’S WORK SPECIFICALLY. THE TEXT IS ACCOMPANIED BY AN ‘IN CONVERSATION’ WITH THE ARTIST, HIS BIOGRAPHER, KEN MCGREGOR, AND KILLERBY HIMSELF.

3

4

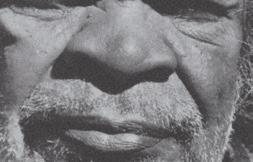

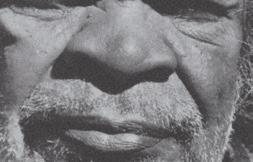

Hubert Pareroultja, 2021. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

HUBERT PAREROULTJA was born in 1952 on the banks of the Finke river. The local Indigenous people, the Arrernte, call this place Ntaria. It was in this area of central Australia that, almost 80 years earlier, Lutheran Missionaries established the Hermannsburg Mission Before that, the land had been lived on continuously by the Arrernte for more than 30,000 years. By the time of Pareroultja’s birth, both the Mission and the Arrernte had endured and, for the most part, lived together in harmony.

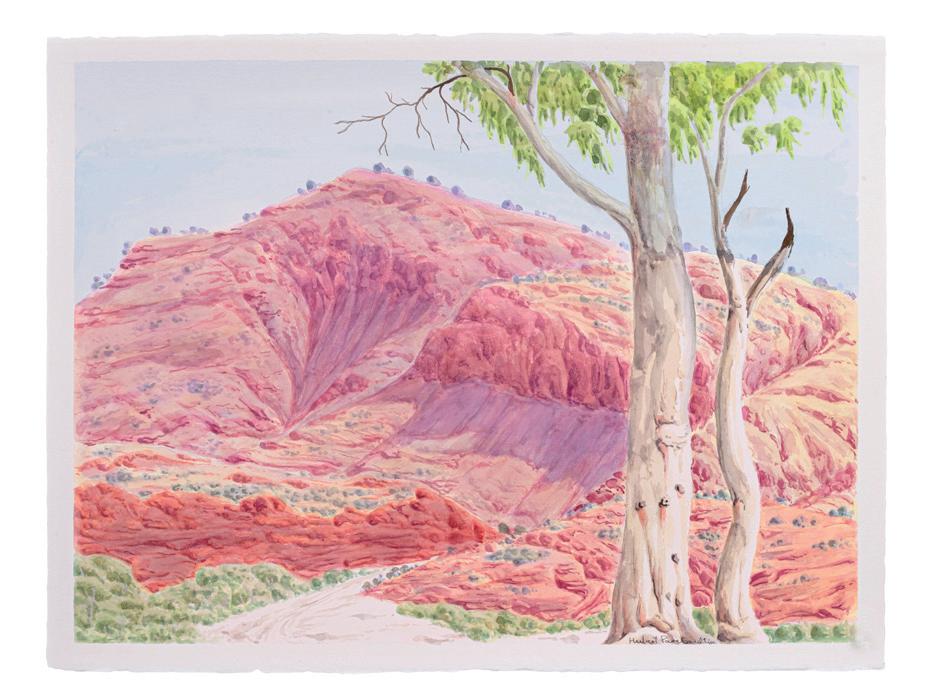

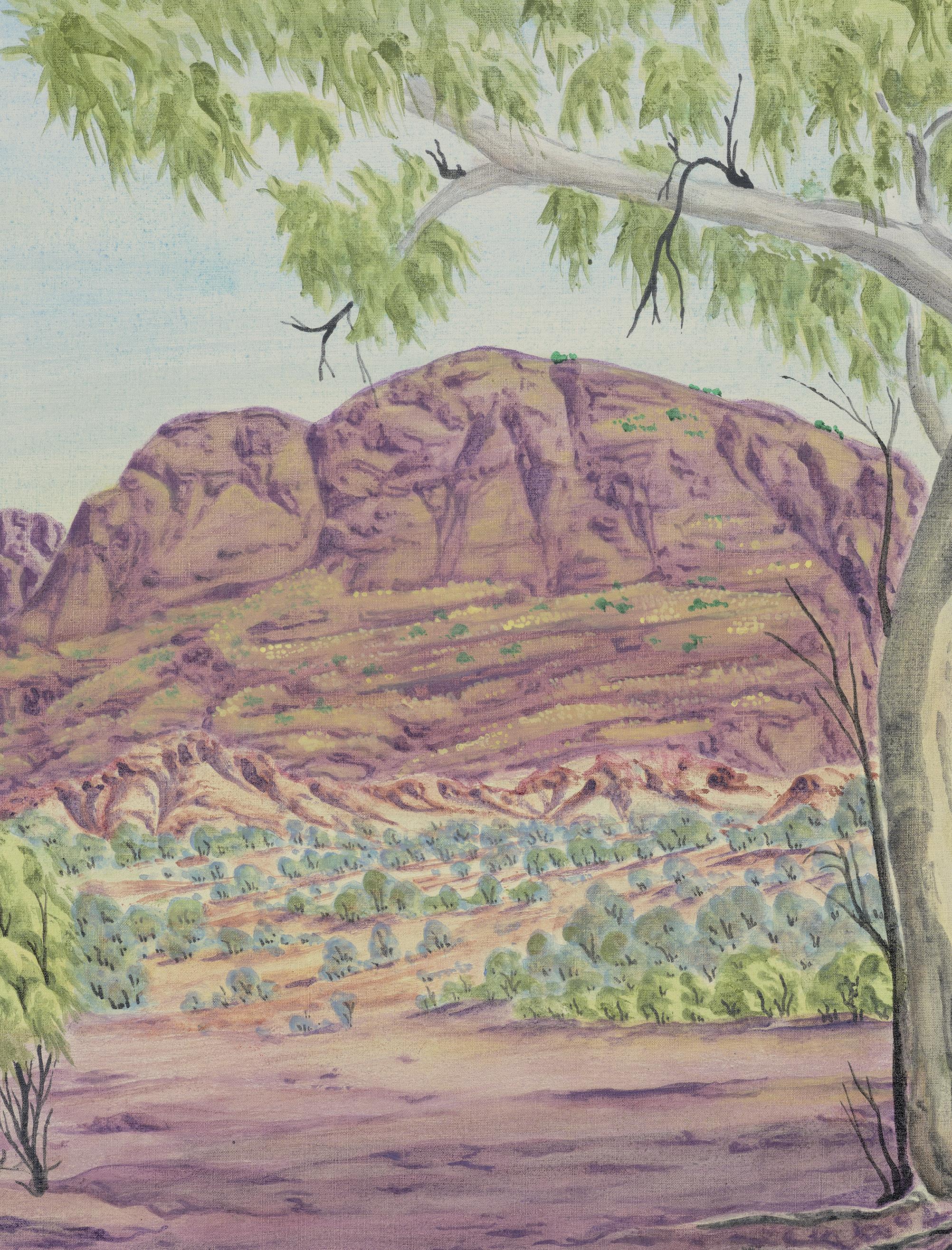

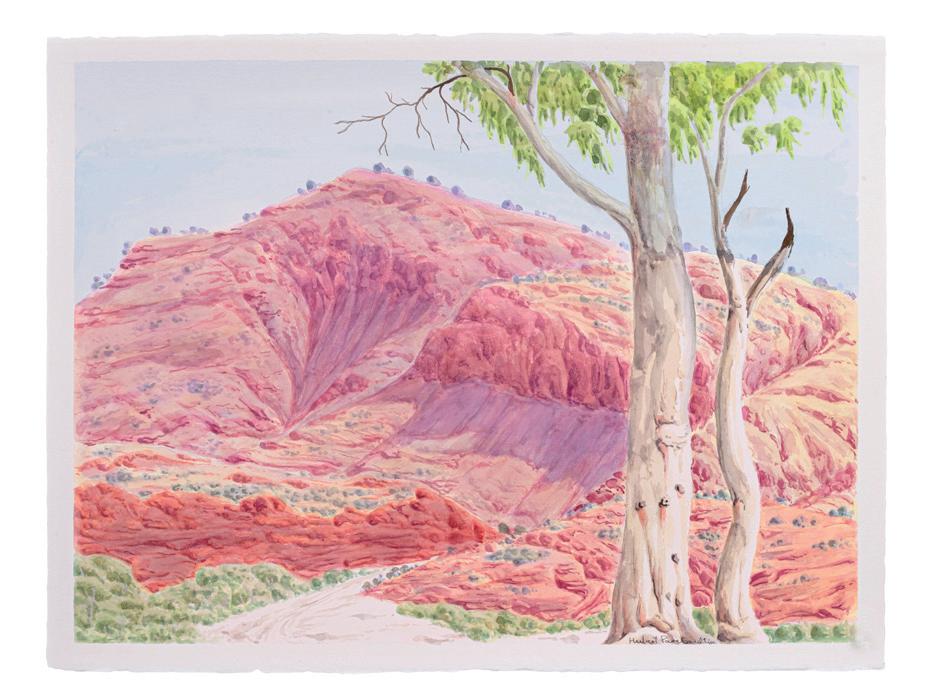

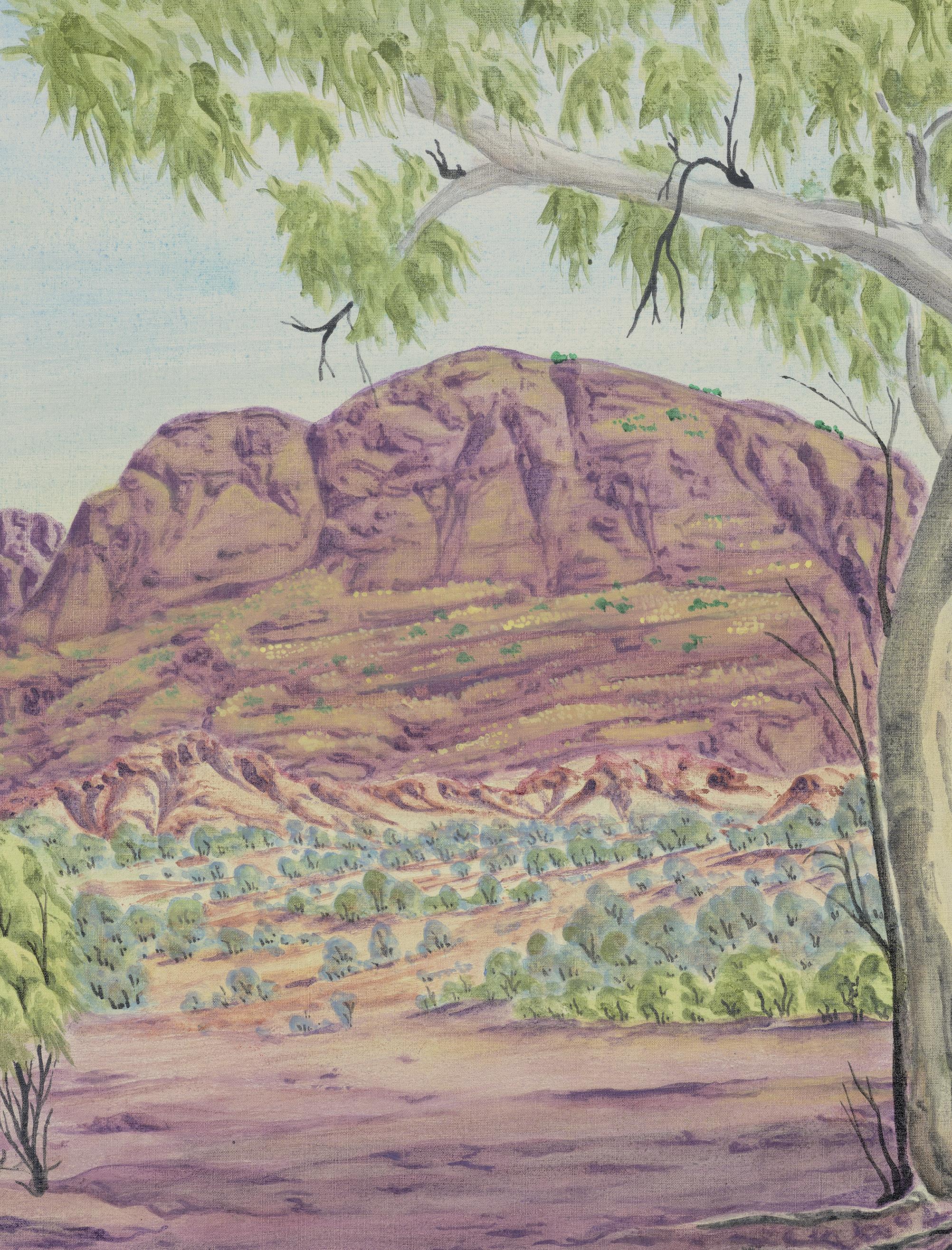

One legacy of this coexistence is the Hermannsburg School, an artistic movement and style of painting pioneered by a non-Indigenous Australian watercolour artist, Rex Battarbee, and Pareroultja’s great grandfather’s second wife’s grandson, Albert Namatjira. Having seen Battarbee’s paintings in 1934, Namatjira approached the artist, asking for artistic instruction and advice. Battarbee obliged, and Namatjira then rapidly absorbed and developed his own representational style, producing works that now stand as archetypes of the Hermannsburg School. Pareroultja’s father and uncles, in turn, received artistic tuition from Namatjira, as did Namatjira’s children. Although, of course, each exponent has their own visual lexicon, what unites almost all Hermannsburg practitioners is a hybridity of one-point perspective European landscape painting, and the earth-bound philosophy of the Arrernte. The aesthetic – luminous, almost hallucinatory in its effect, but always representational – is emblematic of the cultural exchange that took place around the Hermannsburg Mission in the early to mid-twentieth century. No known painting by an Indigenous Australian had, until this moment in the 1930s, utilised the one-point perspective of European landscape painting, a compositional framework which eyes adapted to the Western canon perhaps take for granted. Paintings such as Pareroultja’s Ghost Gums & James Range reconcile the perspectives – conceptual and compositional – of two different cultures, and in that hybridity, produce something unique to the Contemporary Indigenous Art Movement.

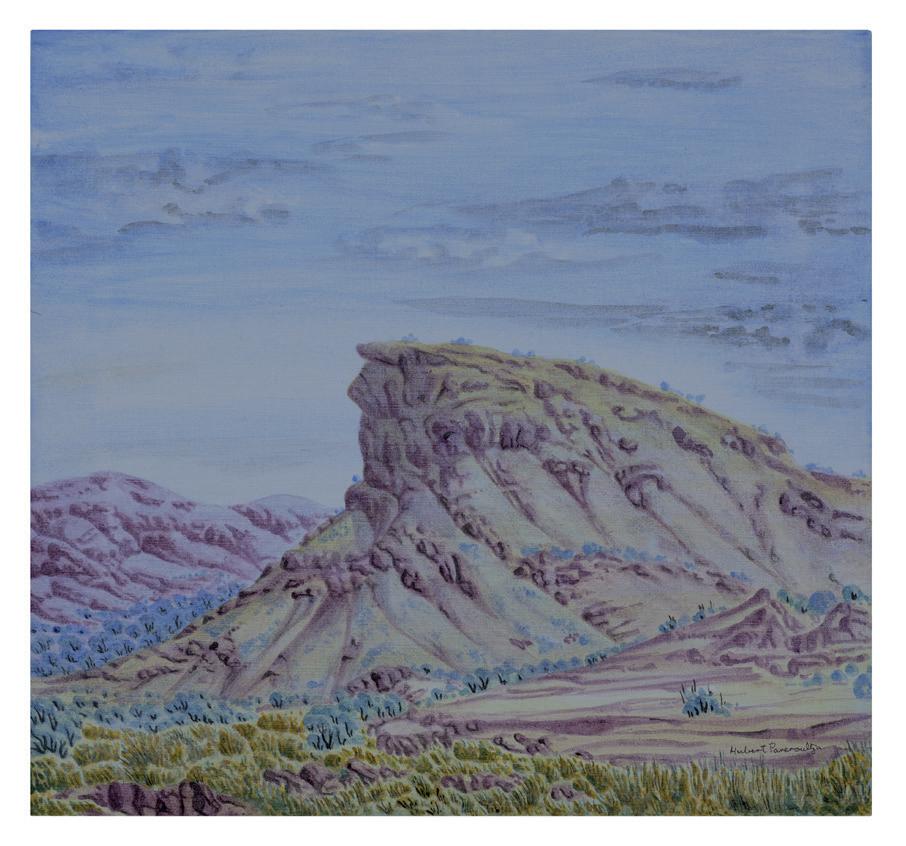

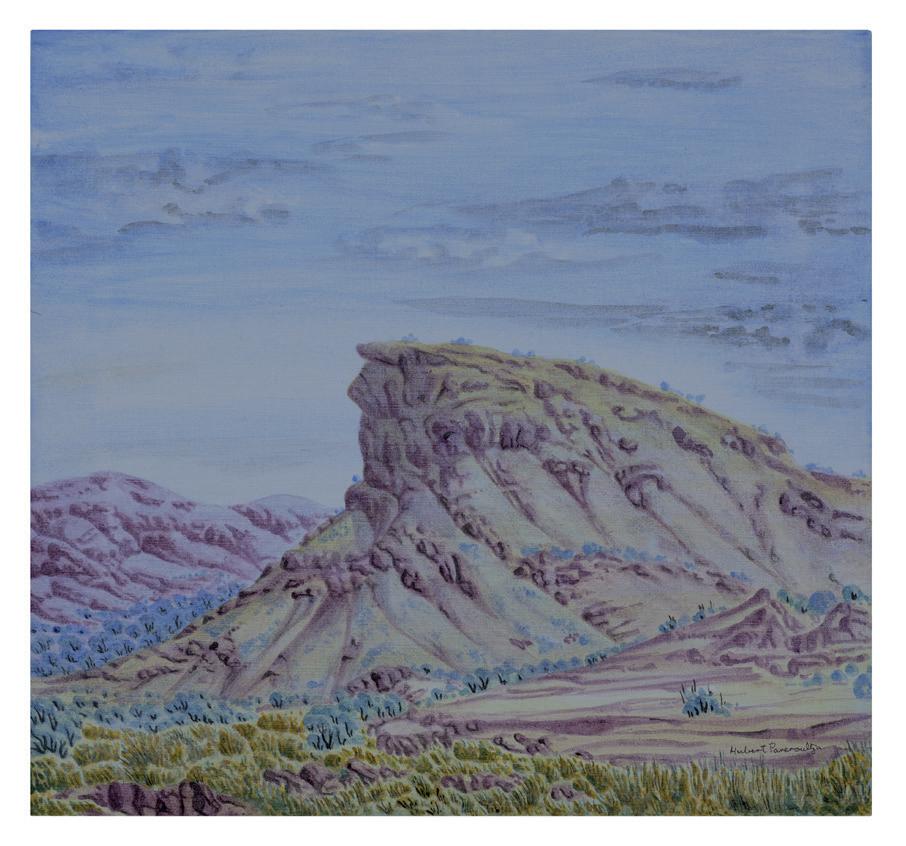

Within the Hermannsburg School, what perhaps distinguishes Pareroultja most is his palette, and the effects it creates. Unlike artists such as Jillian Namatjira or Herbert Raberaba, who often painted with dark hues of orange, yellow and brown, Pareroultja brightens his tones, representing the land with, amongst other colours, light greens, yellows and blues. Shadows are often painted with variations of these vibrant colours, which adds to the descriptiveness of these pictures, revealing aspects of the land that would otherwise remain obscured and in darkness. The consequent sensation for the viewer is a heightened sense of one’s surroundings, as though Pareroultja’s brush illuminates more than the naked eye can perceive. This combination of colours also contributes to a sense of life and buoyancy, which Pareroultja retains despite much of the hardship he has endured. In Ken McGregor’s recent biography of Pareroultja, the artist describes how the Hermannsburg school principal, Bob Arnold, would whip him if he or any of the other students misbehaved:

“In junior school we would all march to assembly to the beat of a drum and stand in straight lines and sing God Save the Queen.” When it was Hubert’s turn to beat the drum, he would speed the beat up on purpose and have children skipping and falling all over the place, the teachers were not at all amused. “I got into so much trouble playing the drums but I thought it was funny. In the afternoons we would clean the classroom and showers and toilets and when we left school to go back home in the evening, we would change back into our camp clothes.”

Suggestive of Pareroultja’s stoicism in the face of such hardship, however, is McGregor’s statement that:

“The many forms of violence... Hubert has witnessed during most of his life have not in any way filtered into his paintings.”

Using this vibrant palette, Pareroultja paints with a masterful economy of brushstrokes and, for the most part, without making preliminary drawings. Consequently, forms lack sharp definition, imbuing the pictures with a lucidity and dynamism that mimics the transient nature of the landscape itself. This is perhaps most clear in the painting, Mount Hermannsburg, in which the terrain itself seems to ebb and flow. At the crest of the central mountain, watery pink pigment blurs into the sky above it, and at its base, crimson marks seep into the foregrounded tree. Definition often conveys stagnancy and inertia, whereas this indistinct representative style animates the land and underscores its vitality. The effect is reinforced by the accentuated curve of branches and the angling of horizon lines off their axes, aesthetic decisions which convey a conception of the

land as a living and, within the context of Arrernte culture, familial part of the artist’s life.

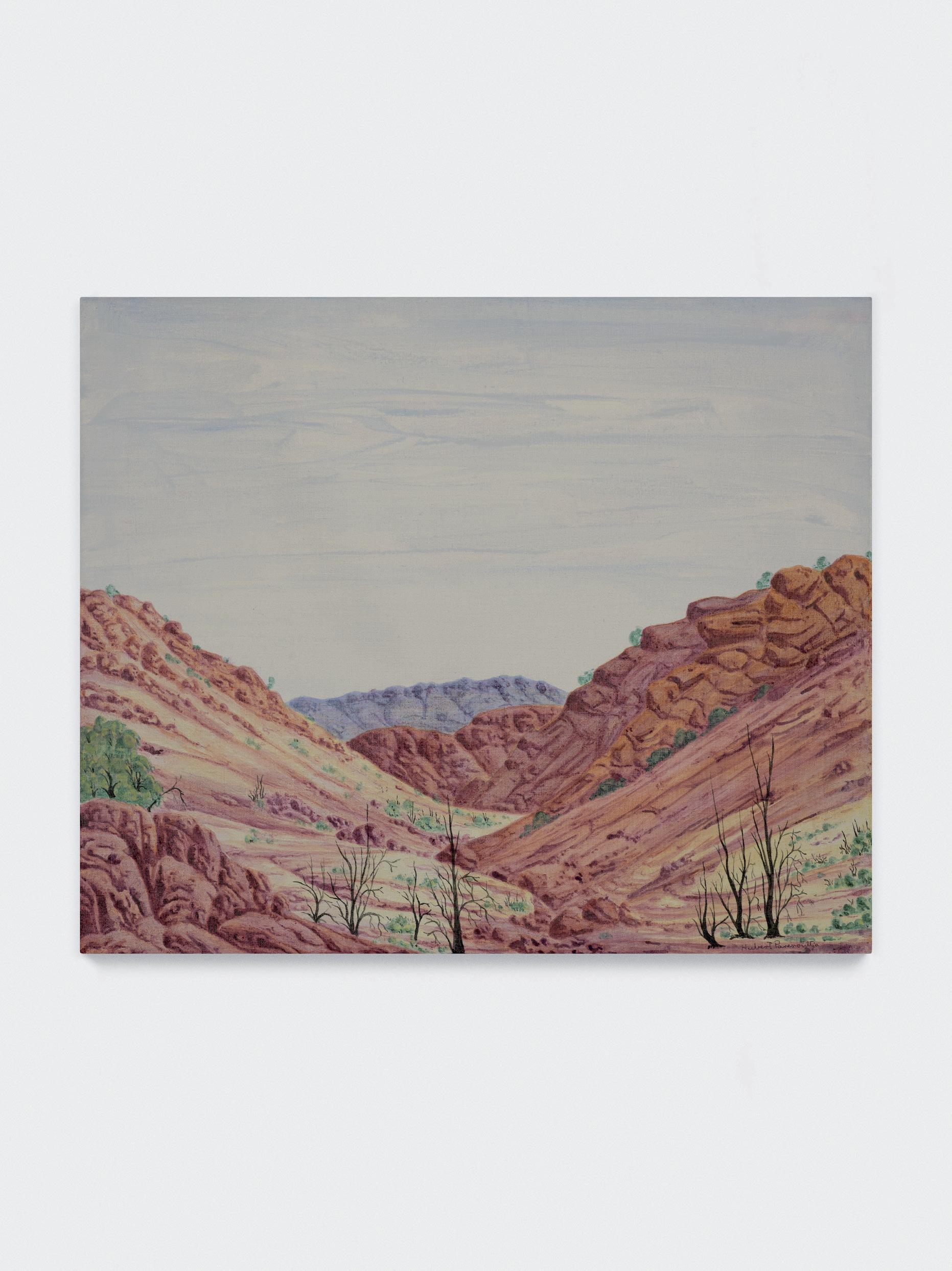

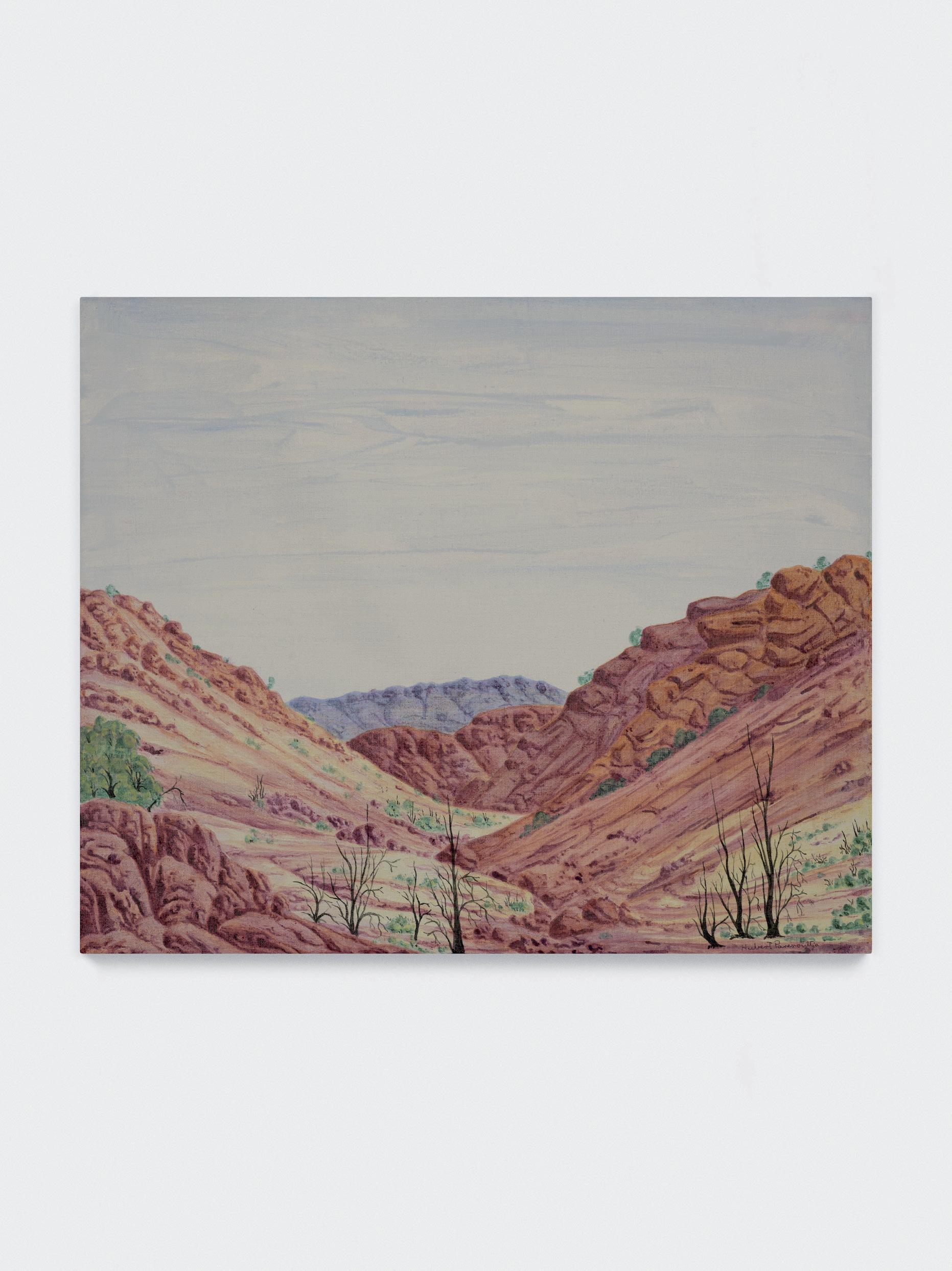

One of the exceptions to the vibrancy of Pareroultja’s palette is Looking Towards the James Range, an acrylic depiction of a winding valley path, painted in subdued reds, browns and blues. It is uncertain whether the muted colours reflect morning or late afternoon light. What is clear, however, is that the landscape is in a process of transformation. We see this in the shift from yellow to red as the left slope meets its opposite hill; in the trees, some bare and others flourishing; and the pale blue vapours, which hint at coming rain. Whether or not Pareroultja intended this landscape as a metaphor for his life is unknown, but comparisons between the two seem inevitable: a path forged between two opposing hills, for instance, can be interpreted as a metaphor for a life lived between two worlds, with “... one foot in the Lutheran ways and one foot in the Arrernte culture”, or as Pareroultja himself puts it, living “... both ways...”

This connection between the artist and the natural world is reinforced by the exhibition title, which references a large, ground-dwelling bird from Pareroultja’s Dreaming. He says that “I hear the sound of the curlew at night on my country... the birds make an unusual sound. They call each other together and celebrate and dance like a sacred ritual and it reminds me of the old Arrernte People who would dance ceremony, which may take the form of a Corroboree”. This underscores the anthropomorphic lens through which Pareroultja views the natural world, but it also situates an interpretation of his paintings within a temporal framework. The early morning or late afternoon light in Looking Towards the James Range, for example, elicits a sense of either anticipation for the nocturnal bird’s arrival, or retrospection following its departure.

Weer Loo - The Cry of the Curlew crystallises the artistic exchange that took place around the Hermannsburg Mission in the early to mid-twentieth century, and represents a continuation of that cross-cultural legacy. That it is Pareroultja’s first exhibition on the European continent thus makes it all the more significant. Just as Battarbee showed his work to Namatjira, so too does Pareroultja demonstrate his artistic facility and the spirit of the Arrernte to audiences here in London.

REFERENCES:

Ken McGregor, When the Rain Tumbles Down in July, (Badger Editions, 2024), 9. Ibid, 17. Ibid, 13. Hubert Pareroultja & Ken McGregor (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Ken McGregor, When the Rain Tumbles Down in July, (Badger Editions, 2024), 125.

1 1 2 3

4 5 5

4

Julius

Image courtesy of JGM Gallery. 6

Opposite: Hubert Pareroultja, Mount Hermannsburg, 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Studio Adamson.

Killerby, 2024.

7

8

Hubert Pareroultja, Across The Plains 2024, watercolour on paper, 52cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor.

JULIUS KILLERBY Hubert, what distinguishes this body of work from previous ones that you have produced?

HUBERT PAREROULTJA Well it’s the first time I am showing my work overseas. Before that, I exhibited around Australia, only, and I am proud to be showing depictions of my own country to a new audience. For that reason, I will be showing a mix of my work, with a variety of subjects done in both watercolour and acrylic paint.

JK Could you describe the landscape where you live and work, and what it means to you?

HP I live about two hours from Alice Springs. So a lot of the paintings are of the bush. The landscape is me. I know it so well, every rock, every tree.

KEN MCGREGOR A lot of the time, people will ask Hubert whether he paints from life or from memory. Hubert can paint from both because he knows the land so well.

JK Does painting from memory change the outcome of the finished work, as opposed to when you paint from life?

HP I would just say that it’s easier to paint from memory, rather than on location. The last two weeks have been 48 degrees, so it’s been impossible to paint on location.

JK Ken, could you speak a bit about the history of Ntaria, the Hermannsburg Mission, and the Arrernte?

KM The Arrernte have been living in the area for thousands of years. The Lutheran Missionaries came in the late 1800’s from Germany and arrived in Adelaide. They then made the arduous trek for thousands of kilometres through this harsh landscape until they found an area that they thought would be suitable to open a Mission. They did help with the supply of food and water for local Indigenous People. They also certainly helped with medicine, schooling and education. Hubert is the benefactor of that because he was educated at the Mission. However, to a large extent they also destroyed Aboriginal culture by removing sacred objects that were important to them. That was difficult for a lot of people and is still a concern for Hubert today. Those objects were part of their culture and was what made them strong. Hubert has very strong feelings about that, but at the same time he’s also happy that he grew up on the Mission, where he had the opportunity to go to school and learn English... Hubert lives in both worlds, having one foot in the Lutheran ways and one foot in the Arrernte culture.

HP Both ways.

KM Yes, both ways.

JK Would you say that there is a parallel between that history and the Hermannsburg style itself, this blend between the more European representative style and the more Indigenous Australian palette, subject matter and appreciation for the land?

KM Yes, I definitely think so. Many people think that Aboriginal People started what they call the Hermannsburg School of Art, but that’s not entirely true. There was an artist named Rex Battarbee, who was a non-Indigenous watercolour artist, and who was travelling in the West MacDonnell Ranges, painting the landscape. He exhibited his works at the Hermannsburg Mission, where they were seen by the Aboriginal People. There was an artist called Albert Namatjira, who was known around the Mission for being good with his hands and making things. He said to Rex Battarbee that he would like to paint with watercolours. A couple of years later when Rex returned to the Mission, he gave Albert tuition. After a couple of weeks, he was painting very, very accomplished works. Albert then taught his children, his brothers, Hubert’s father, and this knowledge was then passed down from one generation to another. Today, it is the longest continuous art movement in Australia. As with Hubert, I have spoken with many people who are descended from the original Hermannsburg artists. They were fascinated to see their country depicted in a realistic way. They’d never seen that before. They’d previously used dots, circles and lines, and visual motifs relating to rituals and ceremonies, so they were quite amazed. What is also interesting is that all of the artists who Albert taught developed their own style. Each of the

Hermannsburg artists had such a personal affiliation with the landscape that the paintings they produced were remarkably stylistically unique.

JK Hubert, for the benefit of our audience here in London, you are the nephew and godson of Albert Namatjira, one of Australia’s most celebrated artists. Is Namatjira’s work a useful reference and inspiration for your own work, and perhaps in answering that could you explain how you found your own artistic voice within the Hermannsburg School?

HP Well, of course, I don’t want to copy Albert’s work, I want to do it my way. All the work that Albert did has gone, the landscape has changed and the trees have grown. I greatly admired Albert, he was a great man, but I have my own style that I’ve developed over many years that sets me aside from anybody else.

JK I notice in your work, Hubert, that shadows are suggested with variations in colour, rather than tone. For me, it lends the pictures a sense of vibrancy, and almost a hallucinogenic quality, which I think, amongst other things, distinguishes it from works by Albert Namatjira and other Hermannsburg artists. I read in Ken’s book that you and your family lived in a humpy by the Finke river and that Albert Namatjira lived in the humpy next to you. What memories do you have of him and what was he like?

HP Well, Albert passed away when I was a small boy, but my father used to tell a story about him. He was taught to paint by Albert, and I would watch my father and Albert paint on location, along with the other Pareroultja brothers.

KM Albert was very kind to you wasn’t he?

HP Yes, he was very kind. When we used to stay in Alice Springs he would send us parcels with lollies and cold drinks.

KM Yes, Hubert watched Albert work along with his father but, as a child, he was also told not to bother Albert, and to not run around him when he was painting. Albert did not want dust being kicked up and damaging his paintings.

JK Hubert, could you describe your early years around the Mission, and the time you spent exploring your family’s country?

in Palm

Image courtesy of Ken

9 10

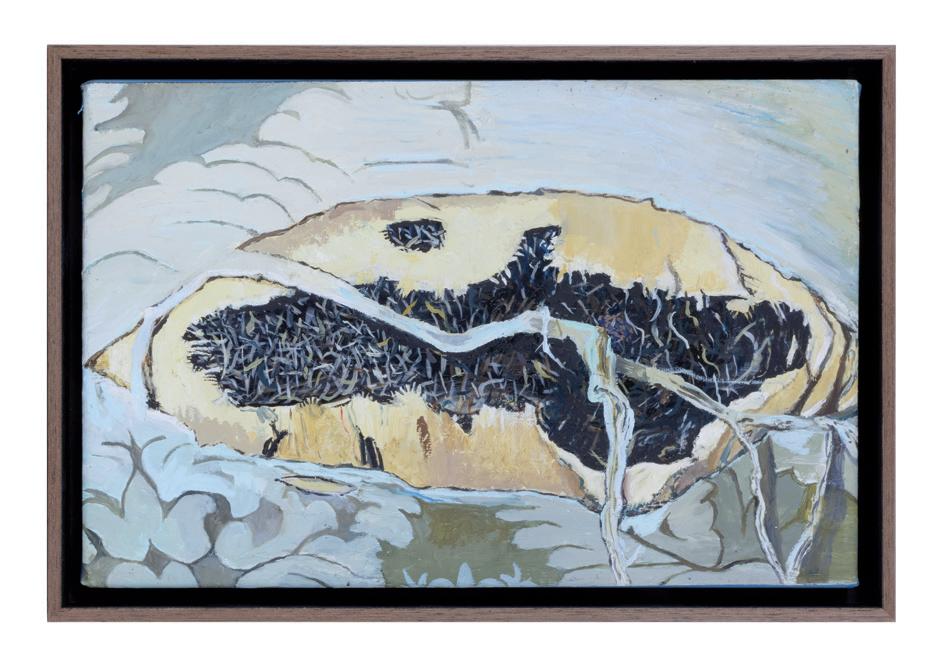

Above: Hubert Pareroultja, Indrai Bluff 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 66cm x 71cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor. Opposite: Hubert Pareroultja

painting

Valley, 2018.

McGregor.

HP When I was a kid I used to go out and spend time with my grandfather out bush, learning how to do work. I would learn where the waterholes were. We didn’t have many things like electricity, we lived in darkness and by the fire. Sometimes, we had a candle. I learned how to look after animals and build fences. It was fun being on country, but it was also tough in those days in the 1960s.

KM Yes, it was also very hot and would have been a very tough time to grow up in. Looking back on it, it was in some ways a very idyllic childhood. But, as Hubert mentioned, there was no electricity, no light. They had to light fires to keep warm and look after their animals. At one time, Hubert had to roll a 44 galon drum full of water several kilometres to the house where they lived, just so that they could have enough water to drink and to cook with. And that was done in extreme temperatures, so it was a tough, hard lifestyle, but they didn’t complain.

HP We had no cars. We could only transport things in wagons, or on donkeys and horses.

JK Yes, and in your book Ken, I certainly get the sense that life around the Mission was idyllic, but also incomprehensibly hard. I am thinking in particular of the project to build the water pipeline, and just the idea of having to build kilometres of pipeline in 45+ degree heat sounds incredibly difficult.

KM Yes, the Kuprilya Springs pipeline was in fact worked on by Hubert’s father and uncles, and it was so hot during the day that they often had to work at night. They were only using crowbars and picts. They didn’t have any of the heavy machinery that we use today. The pipeline was essential for the Mission because it allowed them to grow a lot of vegetables and reduce instances of scurvy, amongst other things. So yes, it was essential to the Mission, but an incredibly tough endeavour to build it.

HP There were no pumps in the pipeline either, so sometimes it would take a very long time for the water to flow down. It was gravity fed.

JK As I understand it, money was raised for that project by asking artists from the Hermannsburg Mission to create artworks that could then be sold. Is that correct?

KM Yes, that’s correct, but not just artists from the Mission. Artists like Rex Battarbee contacted a lot of friends from Melbourne to donate and they also had coverage in the newspapers. Some artists set up studios and painted portraits. Everything was done to try and raise money for the pipeline, which was absolutely essential.

JK So at what stage did the Hermannsburg School, and Albert Namatjira, become a household name?

KM During the 1930’s, artists at the Mission began working on Mulga plaques. They would heat the tip of fencing wire and use that to burn images onto these wooden plaques, it was called poker work. Now, this was partly an idea of Pastor Albricht’s, who was the superintendent at the Mission at the time. He thought it was a good idea for these to be produced because there were a lot of tourists coming to Central Australia. During the Second World War, American soldiers stationed in Alice Springs would visit the Mission, as well as other

tourists. So it was a great thing to do, to sell these works to raise money for the Mission. All this money was used to help with the supply of water and food to the local Indigenous People. It was difficult times, there were droughts and dust storms, but these “souvenirs” sold really well throughout the 1930’s. These “souvenirs” are now very collectible works of art, and were the first examples of the cultural exchange that took place between Indigenous and non-Indigenous People around the Hermannsburg Mission. Albert Namatjira was originally known just as Albert. His father was Namatjira. When Albert started painting in the mid 1930’s, the first works that he produced were signed “Albert”. After a couple of months he was signing them “Namatjira Albert”. He then settled on “Albert Namatjira”. Albert passed away in 1959, but was famous and well known from the early 1940’s.

JK Was the Hermannsburg School the first style developed by Indigenous Australians, which utilised one-point perspective, and the more European representative style?

KM I don’t like to say that it was started just by the Indigenous People, because it was started by Rex and Albert, who became very close and trusted friends. I would say that it was developed by a combination of great thinkers and great artists, and two people in particular, that being Albert and Rex. They maintained their friendship throughout their lives. I think it is difficult to credit anyone with the development of the Hermannsburg style without mentioning Rex Battarbee, who was the instigator and the first person to teach the style.

JK So it was very much a collaborative art movement, as I suppose almost any artistic movement is.

KM It was, and from there it’s been passed down from generation to generation, and that is certainly the Indigenous People doing that. Of course, that’s how Hubert learned to paint, from his father. And the Namatjira’s taught their children and their relatives.

JK What I find fascinating, then, is that this style, and that period in the early 20th century in particular, provides a glimpse into the Indigenous conception of the land in a way that is seamlessly understood by eyes adapted to the Western canon. It seems to be a fascinating blend of two different cultures.

KM Yes, it definitely is. These paintings possess a spirituality, and they are not just depicting the landscape. Hubert can tell you more about this than I can, but when he goes into the landscape, he doesn’t just see the landscape. He sees his ancestors, he sees the spirit people, and they talk to him. When the wind blows, it’s the spirit people telling him stories.

HP Yes, they talk to me a lot.

KM So much goes into these paintings, it’s as though Hubert is the landscape himself. In every tree, every rock, every gorge, every waterhole. Not only does he know it so well, but it’s part of him. Unless you know this culture well and unless you believe in their spirituality, it’s difficult as a Western person to understand that, but he is the landscape and the landscape is him.

JK I find it interesting, Hubert, that in your work there are no people and no indication of people having been in the landscape. But, of course, you see the

“... when you walk around in country like this, you can feel some things looking at you, helping you. the trees, rocks, animals, the birds are watching you, and i listen and watch them all.“

- Hubert Pareroultja

2023,

Image courtesy of Ken

11

Hubert Pareroultja, Flowers

On The James Range

acrylic on Belgian linen, 76cm x 83cm.

McGregor.

12

entire history of your people in the trees, the bush, the animals. You imbue what is ostensibly just a landscape with all the history of the Arrernte.

HP When you walk around in country like this, you can feel some things looking at you, helping you. The trees, rocks, animals, the birds are watching you, and I listen and watch them all.

KM It’s often difficult for Western people to understand how Indigenous people think about the land, Julius, but when the wind blows its the old people speaking to them, and when they are walking around the landscape, there’s a spirituality that Hubert feels every day. He has painted some works of man-made subjects, such as Areonga Station, and humpies that were there. But usually he just depicts the landscape.

JK There’s a passage in Ken’s book, Hubert, which I personally found hilarious, if also a bit sad. Ken writes about how when you were at the Hermannsburg primary school, the other children would be made to sing ‘God Save The Queen’, whilst you beat a drum to keep the timing. There’s a quote where you describe how you would deliberately speed up so that everyone was thrown off rhythm and, as you say, “... fall all over the place.” I get the sense that you combatted the disciplinary side of the Lutherans with a kind of stoicism. Would you say that that’s accurate?

HP Yes, that’s right (Hubert and Ken laugh).

KM That’s even true of Hubert today.

JK The seriousness of the missionaries must have seemed quite ridiculous at times, I imagine.

KM Hubert’s grandfather Palerula, also known as Kristian, didn’t like the rules and regulations of the Mission, and the authoritarian aspect of it. He walked off the Mission several times because he was a tribal man, who lived in tribal ways. He was also a strong man, and the spear was his choice of weapon, which was sometimes used to settle disputes. The missionaries did not like that because they tried to enforce their Western laws on a group of people who had practiced their own ways for thousands of years. There was a bit of conflict there.

JK Did the teachings of the Lutherans have any effect on the Indigenous People’s belief system?

HP I believe in Lutheranism, and in my own culture as well.

KM And you attend church every Sunday?

HP Yes, I do.

JK I also imagine, given your relationship to the land, Hubert, that you would never feel lonely in the landscapes you depict. Even if you were ostensibly by yourself.

HP Yes, I never feel alone because the ancestors are watching me, looking after me. I believe in that, and I believe in church. I believe in both ways. In my country, when I walk around, I don’t feel fear. They are looking after me. I can feel it.

JK When did you decide that your art was something that you would like to commit to and pursue for the rest of your life?

HP I was a stockman and used to work out on the land for many years. I had always liked making art, so when the stockman work stopped, I went back to the Mission and started to paint again. I also needed to make money to support my family.

KM In those days, a lot of the Indigenous people would be paid in rations. So when people started to see that Hubert was quite an exceptional draftsman and artist, he then realised that he could make a reasonably good living selling his paintings.

JK I get the sense that you have a real affinity for animals, Hubert. Is there one which is particularly dear to you?

HP My favourite animal is the horse. When I was a little boy, my grandfather taught me how to ride one.

KM At his outstation, Hubert’s also got emus, chickens, goats...

HP Yes, it’s because I love animals.

KM His affinity for animals is quite extraordinary.

JK I get from your work, Hubert, a distinct sense of optimism and obviously beauty which, correct me if I’m wrong, is perhaps at odds with much of the hardship you’ve endured in your life. Would you agree with that and, if so, what compels you to emphasize the beauty in the world?

HP Because I find the landscape so beautiful. Simple as that. I paint what I see. And my father told me to only paint my own country. I do not paint anywhere else, or I will get punished for it.

JK Could you explain the meaning of the exhibition title, Weer Loo - The Cry of the Curlew?

HP A curlew is a bird that comes out at night time. It calls out and then other curlews join it and dance around. I only hear it at night, and it’s part of the Dreaming of my outstation.

KM These birds make an extraordinary and unusual sound and they call each other together to celebrate and dance. It’s almost like a sacred ritual and Hubert tells me it reminds him of the old Arrernte people who would dance in ceremonies in the form of a Corroboree. His London exhibition is a comparable celebration and a dance of his own work.

JK Do you make preliminary drawings Hubert? Or do you paint directly onto the paper or canvas?

HP I start off by painting the blue skies. I turn the painting upside down to do this, and then leave it to dry. Then I turn it the right way up and put the yellow down for the hills. Then I put the trees in last.

JK Do you paint quite quickly as well? From looking at your work, it’s got this vitality and freshness to it, which is sometimes missing in works that are laboured over.

HP I’m careful with the trees.

KM Hubert has, as he mentioned, a system where he turns the painting upside down to paint the sky, and that’s to stop the blue from dripping down. Watercolour, as you know, is a tough medium to use, you can’t paint over it like you can with acrylic paint. For the ghost gum trees, Hubert uses the white of the paper itself, and then builds up tone and colour from there. I introduced Hubert to acrylic paints several years ago, and he mastered his technique with them almost straight away. He waters his acrylics down, however, to such an extent that they go onto the canvas almost like watercolour, but the process is a bit more forgiving because Hubert can paint over it.

JK Hubert, what response to the exhibition are you hoping to achieve from your audience here in London?

HP I hope that they love it.

JK I am sure they will.

Opposite: Hubert Pareroultja, Looking Towards The James Range, 2023, acrylic on Belgian linen, 76cm x 90cm. Image courtesy of Ken McGregor. 13 14

in conversation with mafalda von hessen

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING MAFALDA VON HESSEN’S EXHIBITION, LOOKING IN, CHLOE

(GALLERY ASSISTANT AT JGM GALLERY) SAT DOWN WITH THE ARTIST TO DISCUSS HER UPCOMING SHOW. THE CONVERSATION WAS AN OPPORTUNITY TO EXAMINE VON HESSEN’S WORK, ITS CONTEXT, AND THE THOUGHTS AND PROCESSES SURROUNDING IT.

WHAT FOLLOWS IS A TRANSCRIPT OF THEIR CONVERSATION.

15

REDSTON

16

Mafalda von Hessen in her studio, 2024. Image courtesy of Pierluigi Macor.

“ the nice thing with painting is that, although I‘m very figurative and my education is very conservative, you can play with proportions, you can play with light, you can play with everything.“

looking

CHLOE REDSTON Mafalda, when did you first start painting? Is it something you’ve done all your life?

MAFALDA VON HESSEN I always had this urge to paint. I even still have the first painting I ever painted in kindergarten. It’s also very figurative! Painting was always very important for me. I have done it all my life – from the age when I could hold a pencil until now.

CR In relation to the scenes that you depict, is there a kind of escapism element within the interiors?

MVH Well, in the beginning probably there was a sense of escapism. Especially when I was little. But now, I don’t know, I just… I just need to do it. There were times where I didn’t paint because I was a costume designer or I was doing my fashion or in a period of transformation between my marriages. In those times, I always felt that something was missing. I never felt complete as a person. It’s like a vocation. A higher calling, if you will.

CR How do you choose your subject matter? What inspired you to depict scenes of ‘the great indoors’, and what are your biggest inspirations and influences?

MVH Usually it’s very spontaneous. When I find something, I look, I take a photo. But sometimes I design the set – I did my masters in theatre stage and costume design. So it’s always in me, this thing. And sometimes it’s the object or the place which talks to me – so it’s something very organic. If I have a commission and somebody says “Can you paint me or my environment?” I still try to create an atmosphere which suits me. I get inspired by colours, by light, by the combination of the things put together. Of course, I often discuss it with Rolf or the person who’s next to me. When I do a portrait, I talk to the person about what they want, which is very important.

CR What is the genesis of an idea and how does it progress and develop?

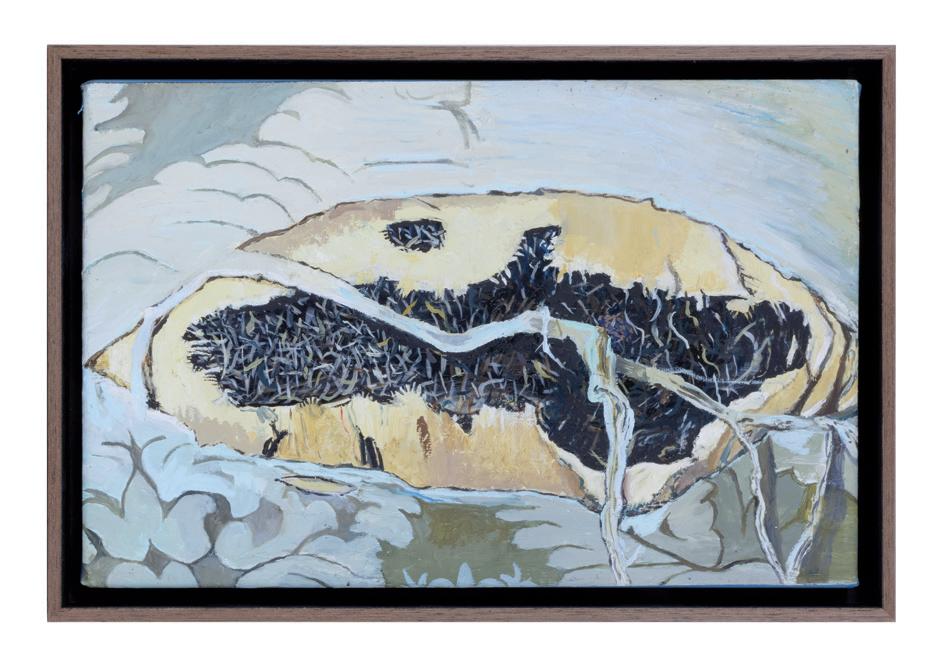

MVH I directly react to the people or the place. I choose the place or set it up. It depends on what it is – whether that be an interior, nature, or a portrait. They are three things which I approach differently. I love to be outside, I love to be in nature, and in that I take a totally different approach than I do to the interiors. Nature sometimes is so breathtaking, but so overwhelming, so big you can’t take it all in. So my way around that is to concentrate on something small like a stone or a branch or something similar. When it comes to interiors, or objects, they talk to me. I want to portray them. For example, for me, chairs some-

times have souls. I’m not sure how to explain it!

CR Are the interior spaces you depict personal to you? If so, what is your relationship to them? Are these spaces you inhabit or perhaps frequent, or are these a snapshot into the spaces of others?

MVH They can be both, they can be personal and they can be things which I see somewhere. I’m very discreet and very honest, so when I see something which I really like, I always ask for permission to take a photo – because not everybody likes to have their places represented in art without agreeing first. Sometimes I find that I look into rooms and they are totally untidy, or it’s just storage, and there’s dust everywhere – rooms like this I find amazing! But I can’t paint that fast. I have so many ideas and I haven’t got them all out yet!

CR You briefly touched on this previously, but are the scenes depicted in their organic state – do you find the scenes like this and attempt to solidify their transitory nature, or do you dress them intentionally for the purpose of representation?

MVH Both! I shall give you an example. I might come to an old house to survey it, I go to the attic and there’s something beautiful and untidy in the middle of the room. I like it so much that I take a photo! Then I go home because there’s an element that I find so intriguing, I must paint it and add my own interpretation. So maybe I create a different light, because the light was too cold, or too warm, or there aren’t enough shadows, or I want to alter the proportions and then I start working from there. The nice thing with painting, although I’m very figurative and my education is very conservative, you can play with proportions, you can play with light, you can play with everything.

CR Could you describe your process and what you attribute to a feeling of introspection?

MVH When I first get into my paintings, or into the substance or in my vision – let’s put it that way – I call the first stage embryos. I do little scribbles and then, from there, I do an A4 sketch. And then I prepare my canvas to which I have already applied colour. Then I do a sketch the same size as the canvas and then I get into my flow. I don’t think, I just go with the flow until it’s done. In the past, like 20 years ago or 10 years ago, I painted in the garden with my children. Now, with the COVID-19 pandemic, I started painting again because I had this urge. In the beginning it was quite tough for me because I had lost practice.

CR I just want to touch on what you said there

“ My paintings are my personal perspective on ordinary and seemingly beautiful and unbeautiful places and objects, in which i try to find my own harmony and grace.“

about the pandemic – did your paintings of interior spaces coincide with spending more time indoors as a result?

MVH Yes, I’ll tell you why: I had a fear of painting. I knew that I had lost the practice. It’s like somebody who wants to do a marathon but hasn’t jogged in a long time and is afraid to start because it’s so frustrating to start at the bottom, it takes you longer to get where you want to get to. COVID gave me time. We were all stuck at home. I started painting again. Everybody in my house had their own space and so on, and I started painting in my bedroom. It was so nice! There was this immense feeling of relaxation without the pressure. So, in the beginning, the paintings were very much of my own interiors.

CR There’s also something to be said for finding beauty and finding the poetic in something that you are surrounded by every day, especially in circumstances like the pandemic where a lot of people felt trapped by their spaces. Finding the beauty in the objects that surround you becomes a form of escapism in itself.

MVH Yes, definitely. Definitely. Also, I feel like

places or a moment or this millisecond sometimes it’s as if they give me a wink! That moment, that light, that constellation of furniture or whatever.

CR I like that term you use – a ‘constellation of furniture’. It implies the organic in something that is materially artificial.

MVH Yes! They are not just pretty visions. My paintings are my personal perspective on ordinary and seemingly beautiful and unbeautiful places and objects in which I try to find my own harmony and grace.

CR To me, the subject matter of your work possesses a contemplative tone, bordering on the melancholic, which is seemingly at odds with the vibrancy of your chosen colour palette. Can you describe your use of colour and how it interacts with the mood of your works?

MVH Colour and proportion are of equal importance for me. Colour gives vibrancy and enhances the inexplicable mood of things – the mystery. I don’t often think about the colour at the time, I get into a flow, a meditative state, and when I step back from

17

in

18

19

courtesy of Studio

20

Mafalda von Hessen (left) Chesa Planta 2 Ardez, 2024, oil on canvas, 73cm x 63cm, (right) Peter’s Shoe 2023-24,

oil on canvas, 166cm

x 126cm. Image

Adamson.

my paintings, sometimes I like what I have achieved, sometimes I scratch over it. My paintings have layers. What lies underneath may have a different colour or texture, sometimes this seeps through to the surface and sometimes it doesn’t. But in that sense, the act of painting becomes like modelling, and the paintings themselves morph into those objects I depict.

CR The title of your exhibition, Looking In, alludes to the intimacy of internal space both physically and psychologically but also implies that we, the viewer, as mere spectators are separate from this. Do you think this places the audience in a voyeuristic standpoint, or do you intend to encourage introspection from us as well – perhaps the two can coexist?

MVH I think they can coexist. First of all, I paint for myself. I don’t paint for the spectator. So, if you gave me a commission, of course I would do my best to put the elements in which you desire, but I would still paint for myself! I’m very selfish at that moment when I am painting, it’s more for myself than for other people. Because otherwise it would be fake. Otherwise it wouldn’t work, it wouldn’t agree with me. So it’s a natural, very organic, reaction within me.

CR The everyday objects you depict are often intricately decorated, perhaps even chaotic, whilst the furnishings are proportionately larger than life, giving the impression of the endlessness of the indoors. How do you think, compositionally, you create both a sense of vastness and, at the same time, intimacy?

MVH I just like to play with painting. In painting you don’t have rules and that is my freedom. Why shouldn’t I put some birds on a chair and the chair on the table? There’s no one who tells me I can’t do that! If I like it I put it in! In that, there is something comforting but also alienating. The compositional opportunities are endless, but that also reveals something about the inner workings of my mind.

CR For me, the intimacy of the internal space is juxtaposed with a feeling of distance, created by the unknown. An indescribable buzz of life and hints of recent activity, such as the coats on the mirror or an indent on a chair, situates an interpretation within the poetics of time, and yet, this notion is simultaneously dispelled by the underlying question: what is about to happen, or what has happened? What mood do you aim to create through these devices?

MVH Usually I try not to create a sterile scene. These devices for me generate a feeling of cosiness through the materiality of the inside, because, as you say, you feel that there’s a person, or rather, there has been a person – there’s a human touch to it. I myself don’t want to limit myself to any singular interpretation. I am, of course, however happy when somebody wants to interpret something and project meaning onto any of my works. I am just playing, and in doing so, I give balance to my paintings through this suggestion of life.

CR Your approach to painting is clearly very playful. I find the juxtaposition of this feature of your work quite interesting because at the same time, it really encourages this kind of deep psychological reaction and introspection.

MVH Exactly. I have never asked a psychoanalyst. You look at me like a psychoanalyst does, which is fantastic. Maybe you are. You ask me questions and I think: yes, she’s right! She’s right! I’ve never seen my work in this light. I think, for me, it’s much more spontaneous than anything, spurred on by a love of materials and surfaces. Sometimes, when I put up my ‘constellations’, as I call them, or I prop them up, I often have a specific element or object which I wish to incorporate, like a cloth of material or a coat, because I like the colour of the coat and it fits the composition. Sometimes they don’t need to make sense, it’s just what it is – what you see.

CR Similarly the hues often suggest a warm, convivial atmosphere, yet eerily the scenes are devoid of an explicit human presence. An air of anticipation for the human presence out of the frame, is reminiscent of, for example, David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash, or Patrick Caulfield’s interior depictions. Are these artists who have particularly inspired you?

MVH I have studied lots of artists and I love art myself. In my family, I have an uncle who was an artist, as is my sister. I grew up in an environment in which art was always talked about. Honestly, when I create, I’m very selfish. I’m thinking purely of the relationship between the canvas, myself, and what I want to depict.

I’m not thinking of anybody else. Of course, I have studied art. But that’s not to say that I want to paint like Anselm Kiefer or like David Hockney or Hector MacDonald or whomever. It doesn’t matter. I paint off an impulse. Otherwise I would be an imitator, an illustrator.

CR There is, therefore, a dichotomy present between the ‘lived in’ setting you create and the interruption of narrative through the absence of human life – and you touched on this with your reference to ‘constellations’ – to what extent are the objects themselves characters in your narrative? Do they tell their own stories?

MVH I see my objects like sculptures. When I paint one single object, for example one chair, it can talk to me. I think of the history. It is, as I said before, as though I seek to imagine their life, their soul. It is the interpretation of the lives of these objects which I seek to depict. It makes the everyday poetic. That’s very beautiful I think. I see harmonies in both objects and in nature. I might paint one single stone or a branch. In a sense, the way I view the world and find poetry in the everyday is consistent no matter what the subject.

CR How do you judge the success of one of your paintings?

MVH I don’t judge the success of my paintings. I am always proud of the result and I like that other people appreciate them. They are almost like people to me, I nurture and raise them from that embryo stage we spoke of, then a skeleton forms and I flesh them out until they are matured and finished. When I am finished, however, I move on. I can’t keep revisiting them because that always instigates self-criticism. I am my own harshest critic. Once finished, so to speak, I never usually retouch my pictures. When I look at them again, sometimes, for me, the perspective is totally wrong but everybody else loves it! I normally just think to myself, next time, I’ll do it differently.

CR I find it really interesting how you describe your process with such anthropomorphic terminology – in doing so you inject life into the inanimate object.

MVH Yes! I even talk to them!

CR Your works are painted with varying degrees of realism and representation. Some are more detailed than others. How do you know when to stop fine tuning the image? What determines whether a painting will be rendered realistically or less so?

MVH In the beginning I found this very difficult. As I said, my uncle was an artist. He used to tell me when to stop, but eventually I had to fend for myself. It’s like when you learn to drive, and the instructor is sitting next to you, and suddenly you find yourself driving all on your own. You never really know how it happens, but you get there! Sometimes a sketch, or a mere scribble, can be so

21

Mafalda von Hessen (left) Chesa Planta 2 Ardez 2024, oil on canvas, 73cm x 63cm, (above) Chair Slit 2024, oil on canvas, 22cm x 33cm. Images courtesy of Studio Adamson. 22

powerful, and that speaks for itself.

CR Would you agree that there is a slight sense of absurdity in some of the arrangements, comparable perhaps to a kind of Magical Realism? I am thinking, for example, of the piece with a chair on top of a table with two birds.

MVH Yes, I love the freedom of setting up scenes. Don’t forget, I’m a designer at heart (for the theatre) and I love it. It’s like playing out a story, why not depict it? Why don’t I put a random object into the painting? It is fun! Rolf also makes beautiful furniture and objects – sometimes I put them into my paintings as well. I also like to reproduce paintings by other artists within the paintings themselves. Sometimes, I see a beautiful room or environment, but I might not like the paintings which currently exist on the walls, so I substitute them for my own paintings! The freedom to do what I want with a painting turns into the magical, the absurd.

CR I notice that many of the objects in your interiors are on the verge of collapsing or falling, whether it be a pile of plates, a coat slipping off a mirror, or a pile of books too close to a table’s edge. For me, at least, this creates a subtle dissonance and a sense of anticipation, even trepidation – lending your work a heightened sense of drama. Would you agree with that analysis?

MVH Of course, you are correct. It creates a tension that makes the scene more curious. I have an anecdote from my father who loved interior design and landscaping. His father was also an architect. One thing my father taught me was that straight passes in gardening are always less interesting. Curves are more exciting. In a similar way, I play with my paintings. It may take me days to make an installation. I place things here and there, remove them and put them back again, trying to find the right balance. When I think I’ve completed it I start painting and think, I don’t like it! So I enhance the elements. There’s a playfulness throughout the whole process, from finding the object to arranging it to putting it down on the canvas.

CR What do you think distinguishes this body of work from previous paintings that you’ve made?

MVH Because I’m so figurative, I used to dislike how I paint. Now I have come to terms with it. I accept it, and I like it. I think this comes down to maturity. I still see myself going more abstract. My art is constantly evolving, and if you were to follow my first painting until now, and even in the future, I think we’ll see there’s a constant, natural evolution. In my mind I’m going abstract. Of course, I could attempt to paint like Pollock or the Abstract Expressionists now, but it would not be me. I wouldn’t feel it. It’s about what you feel. If you don’t feel something, then it’s dishonest. I think these paintings possess honesty.

“... I LOVE THE FREEDOM OF SETTING UP SCENES... IT‘S LIKE PLAYING OUT A STORY... THE FREEDOM TO DO WHAT I WANT WITH A PAINTING TURNS INTO THE MAGICAL, THE ABSURD.“

- MAFALDA VON HESSEN Opposite: Mafalda von Hessen mixing paints. Image courtesy of Pierluigi Macor. 23 24

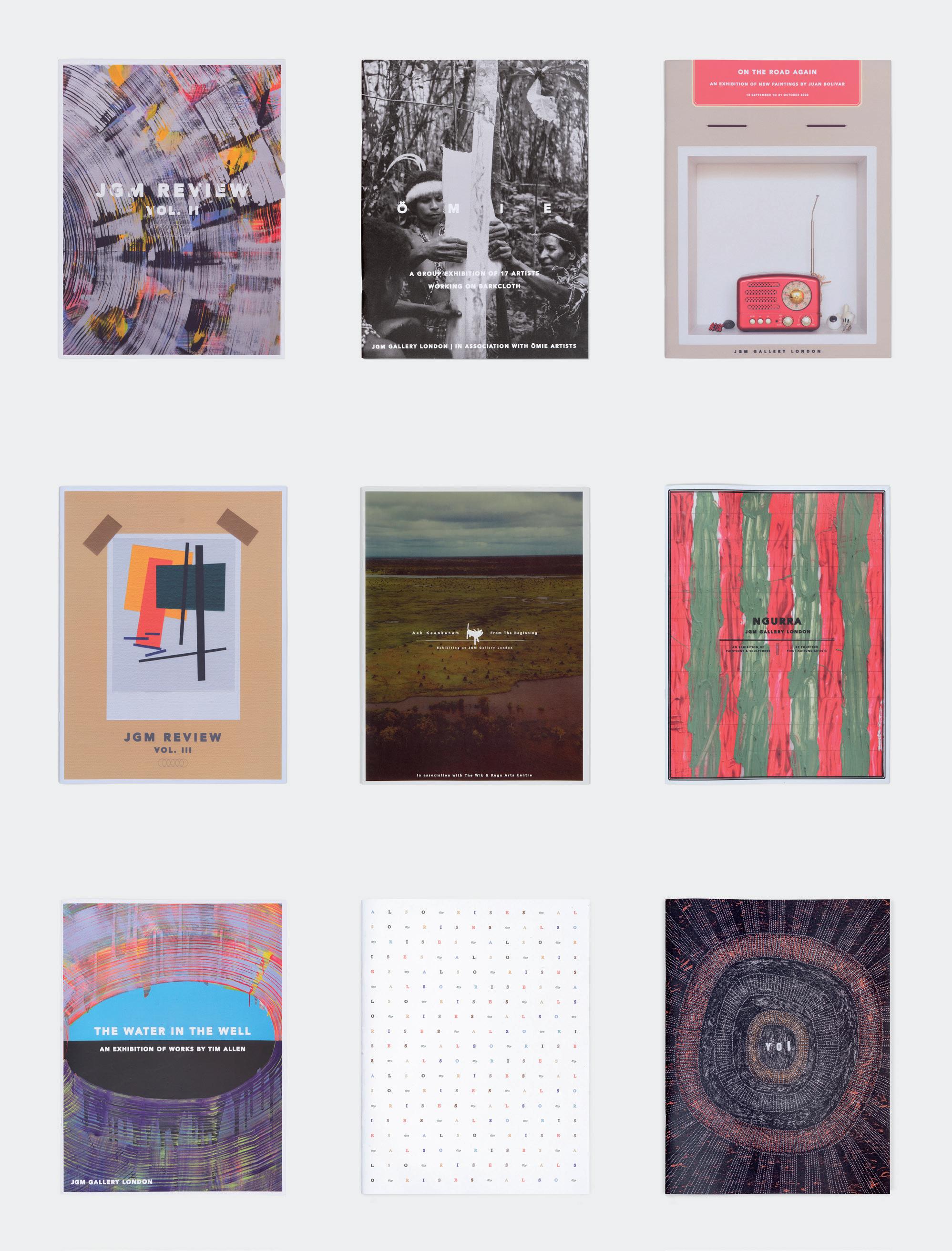

JGM GALLERY PUBLICATIONS

AT JGM GALLERY WE PLACE GREAT EMPHASIS ON OUR PUBLICATIONS. THROUGH THEM, WE AIM TO CONTEXTUALISE OUR EXHIBITIONS FOR OUR COMMUNITY OF FRIENDS, VISITORS AND COLLECTORS. PRODUCED ALONGSIDE THE EXHIBITION CATALOGUES ARE QUARTERLY

ISSUES OF THE JGM REVIEW, A PUBLICATION WHICH SEEKS TO FURTHER AMPLIFY THE GALLERY’S PROJECTS.

25

PUBLICATIONS

GALLERY

26

TO FIND OUT MORE, PLEASE VISIT THE

PAGE ON THE

WEBSITE.

GESTURES OF TIWI ABSTRACTION

THE FOLLOWING ARTICLE BY CHLOE REDSTON EXPLORES THE NATURE OF TIWI ABSTRACTION THROUGH THE LENSES OF GESTURE, ENVIRONMENT, AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE.

27

Tiwi Yoi (Dance Ceremony), 2023.

28

Image courtesy of Ben Searcy and The Munupi Arts & Crafts Association.

- Judith Ryan

- Judith Ryan

THE TIWI ISLANDS, located off the Northern coast of Darwin, comprise Melville and Bathurst Islands, and a number of smaller, neighbouring uninhabited islands. They are home to around 2,500 inhabitants – roughly 2,200 of whom identify as Aboriginal, speaking Tiwi as their first language, and whose ancestors have likely occupied the islands for up to 20,000 years. Although colonisation has had a destabilising effect on the livelihoods of the Tiwi people, they have, despite this, maintained a large degree of self-governance, resulting in a remarkable and dynamic culture. Art is central to Tiwi life; not only does the sale of creative arts form a higher relative proportion of income than any other local government area in Australia, but it stays true to a tradition so antique that it borders on the unimaginable. As such, Tiwi Art reflects the nuanced relationship between all aspects of life on the islands, so fostered over many millennia. The term “relationship”, however, falls short of expressing the complex, inseparable and interconnected nature between the visual arts, music, dance and Country in Tiwi culture, attests Dr David Sequeira of the University of Melbourne. These aspects are linked by a certain spiritual presence, and one which many of the works in this exhibition emanate. Ceremonies provide a forum of artistic expression and dancing, or rather Yoi, which function as an integral role in such activity. When a series of Yoi are performed, some are totemic, some serve to act out newly composed songs, but all possess a narrative function. During such time, participants are painted with natural ochres which take the form of countless, intricate designs called Jilamara. Marks can demonstrate a simultaneously individual and collective voice, recalling elaborate foundational mythologies, everyday life, historic and recent events. These patterns are echoed throughout Tiwi material culture and are transposed onto many of the works in Yoi The works in Yoi are each characterised and aligned by the expressive marks they

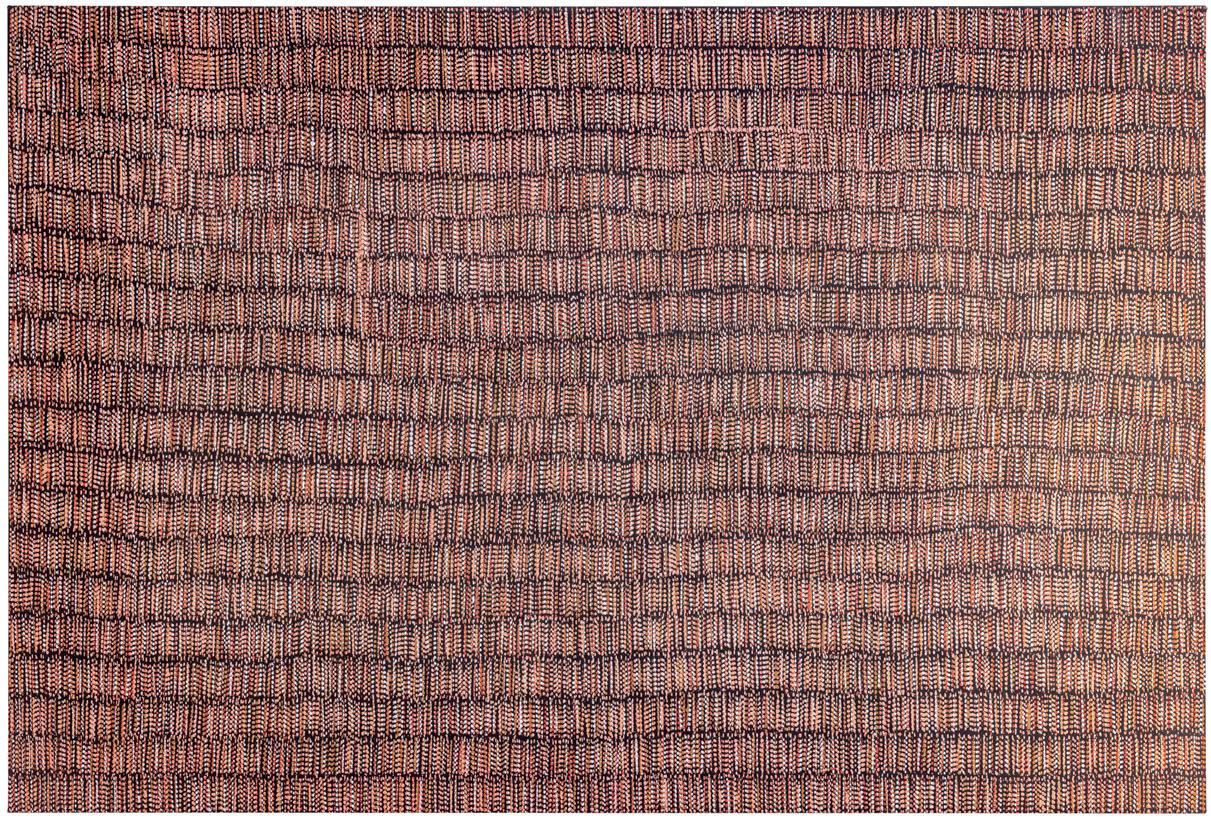

employ. The characteristic mark-making of the Tiwi People exemplifies a process by which surface and mark interact in a dialectic exchange; the mark releases the generative power of the surface. The repetitive and geometric patterns of Lucinda Puruntatameri’s Pupuni Jilamara, for example, though at first glance appear asemic, hint at more than what is displayed through a sense of movement. The two-toned and simplified palette, when combined with the almost mechanical rhythm of marks, paradoxically uniform and yet fluid, creates a sense of hypnosis that resonates with a higher spiritual plane. Manager of the Munupi Arts & Crafts Association, Guy Allain, argues that this effect urges the viewer “... to discover other aspects of our humanity deeply embedded in the Tiwi cosmology – those which are as complex as Greek, Latin or other world mythologies. All of these are parts that play through our universal cultural kaleidoscope.” As such, let us first situate an understanding of these practices within a classical aetiology. We can consider abstraction within a framework of difference, between the representational and self-referential line of the artist. An aetiological account of drawing, narrated by the Elder Pliny, effectively conveys this difference. Pliny’s first account explains that the artist Parrhasius gained distinction through his drawing of outlines and contours. The tale establishes the generative quality of the artist’s mark, which is both created and creating and suggests a notional reality beyond what it actually shows. In the second account, Pliny speaks of a competition between the artists Apelles and Protegenes. The former marks his presence in the latter’s studio through a fine-drawn line. Upon seeing the drawing, Protegenes was instantly aware of its maker and drew a second, finer line. Apelles drew a third and final line, “... leaving no room for any further display of minute work.” The meaning has been the subject of much debate by art historians. David Rosand effectively summarises the connotations of Pliny’s accounts: “... the line of Apelles is self-indicative; its reference is to itself, and, through itself, ultimately to its maker.” On the other hand, Parrhasius’ is “... pictorial, representational...” and its intended purpose is to allude to a mimetic representation of reality. These two examples represent the dichotomy of drawing: the surface mark, which refers to its maker, and its intended representational illusion. When interpreted in conjunction, they provide a framework for the understanding of the processes of abstraction, and indeed, Tiwi Art.

Absolute notions surrounding the artist’s mark become somewhat obscured within the realm of abstraction, and, even more so in Tiwi Art. We can extend the axiom of Pliny’s Apelles, in which a retrospective line becomes an emblem of authorial presence, to the work of Tiwi artists. In Josephine Burak’s Milimika, marks and paint interact, partially obscuring each other, and overlap in a repetitive action which recalls the very intricacies of the hand that made them. This expression of gestural energy, the primacy of which is often emphasised through Tiwi mark-making, offers a unique insight into the movement of the artist and, by extension, the human presence out of which art emerges; the artist’s mark carries the testimony of its author and thus the identity of the artist herself. Moreover, the reference of the non-representational line to the hand that made it simultaneously mirrors the practice of Jilamara. The allusion is thus doubleedged; “ ... the painted body, the body as a canvas, is somehow turned around in a reversed polarity, transposed as such to a canvas.” Though, at first, they seem to resist the urge of mimetic imperative, the marks in Milimika begin to form mesmerising concentric circles. A recurring motif in Tiwi Art, these circles allude to ceremonial dancing grounds. Suddenly the illusion of abstraction is broken. We may once again return to the aphorism of Pliny’s Parrhasius, as the artist’s mark becomes, in effect, one with the object depicted. As such, each mark is, in fact, a meticulously constructed seme – or unit of meaning. When interpreted together they create a complete portrait of Tiwi ceremonial activity. We might therefore consider Tiwi Art alongside the aesthetic sensibilities of Western abstraction, and yet, the weight of spiritual significance, alluded to by the context, extends far beyond our expectations. Demonstrating a synthesis of art in all its forms, for the Tiwi People “ ... to sing is to dance is to paint.”

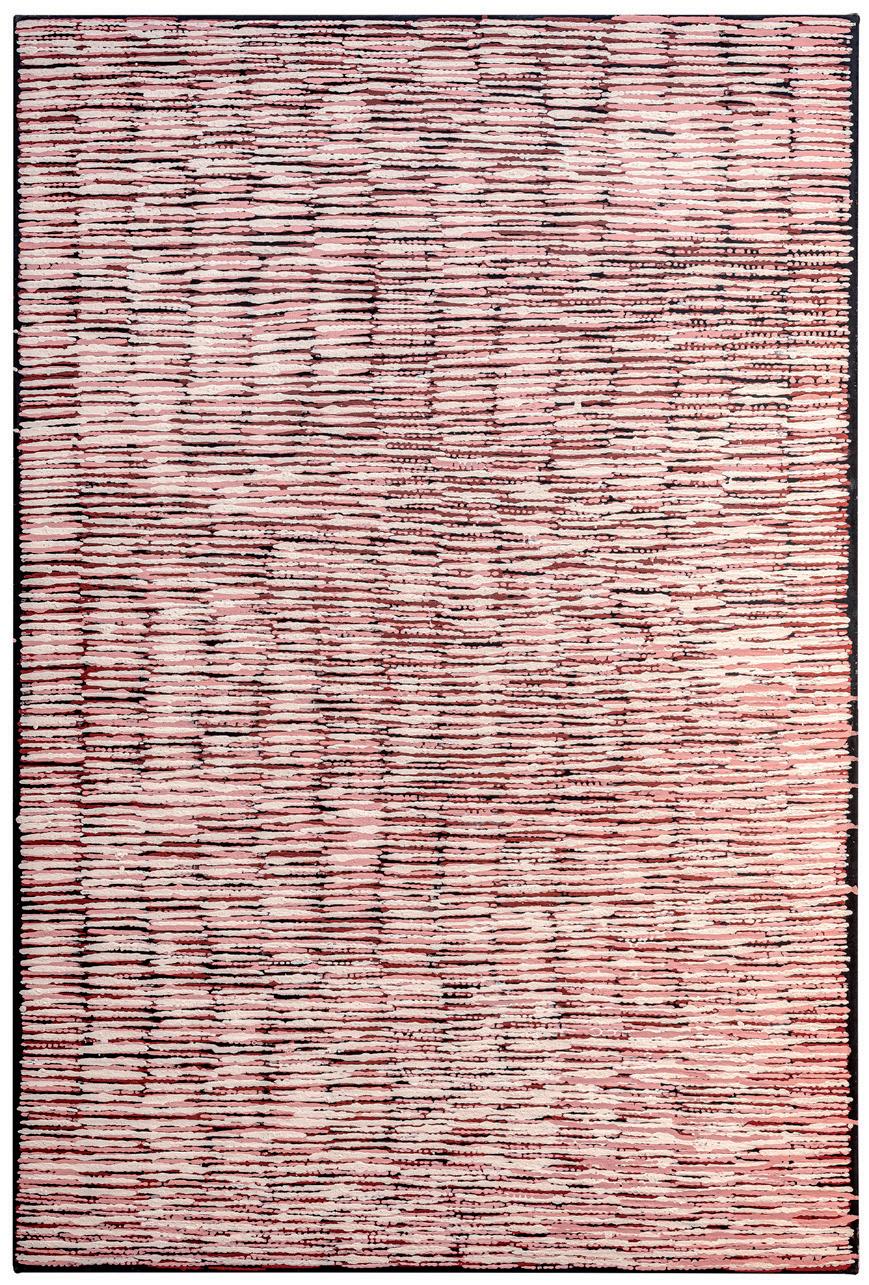

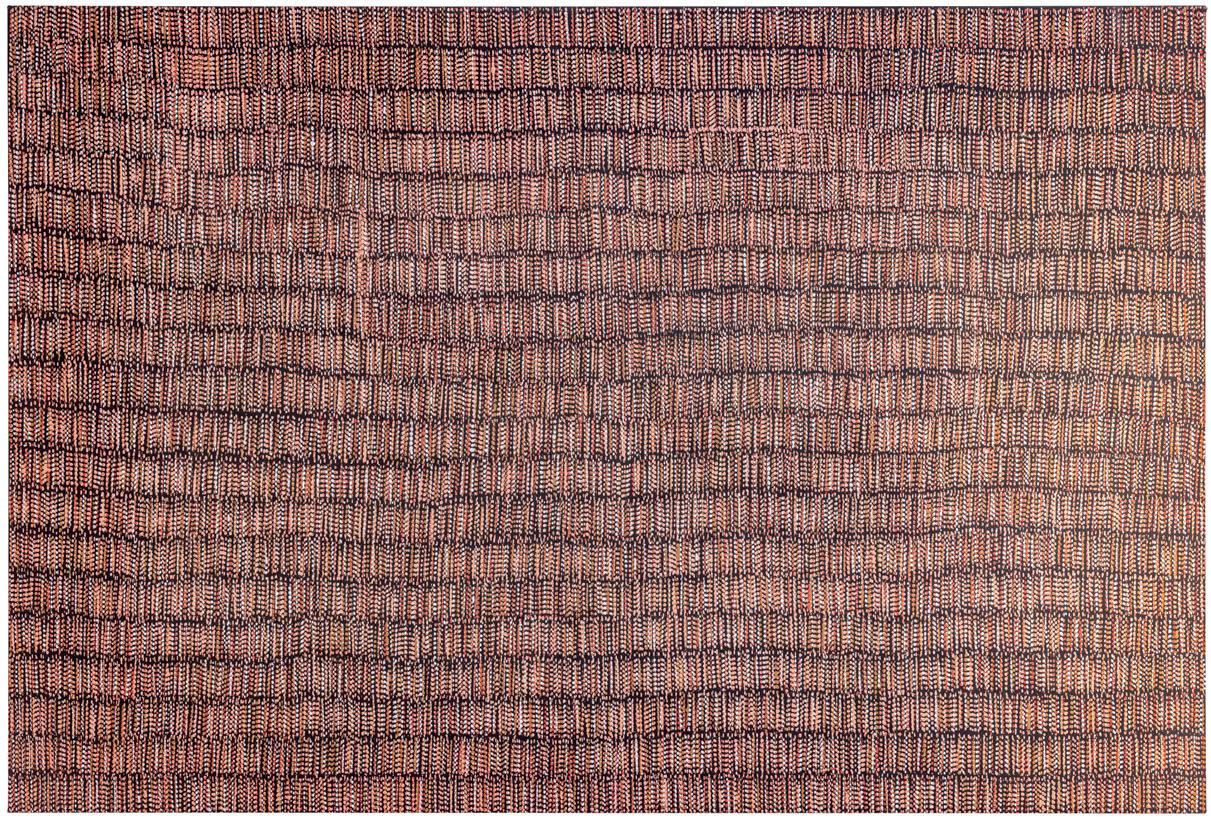

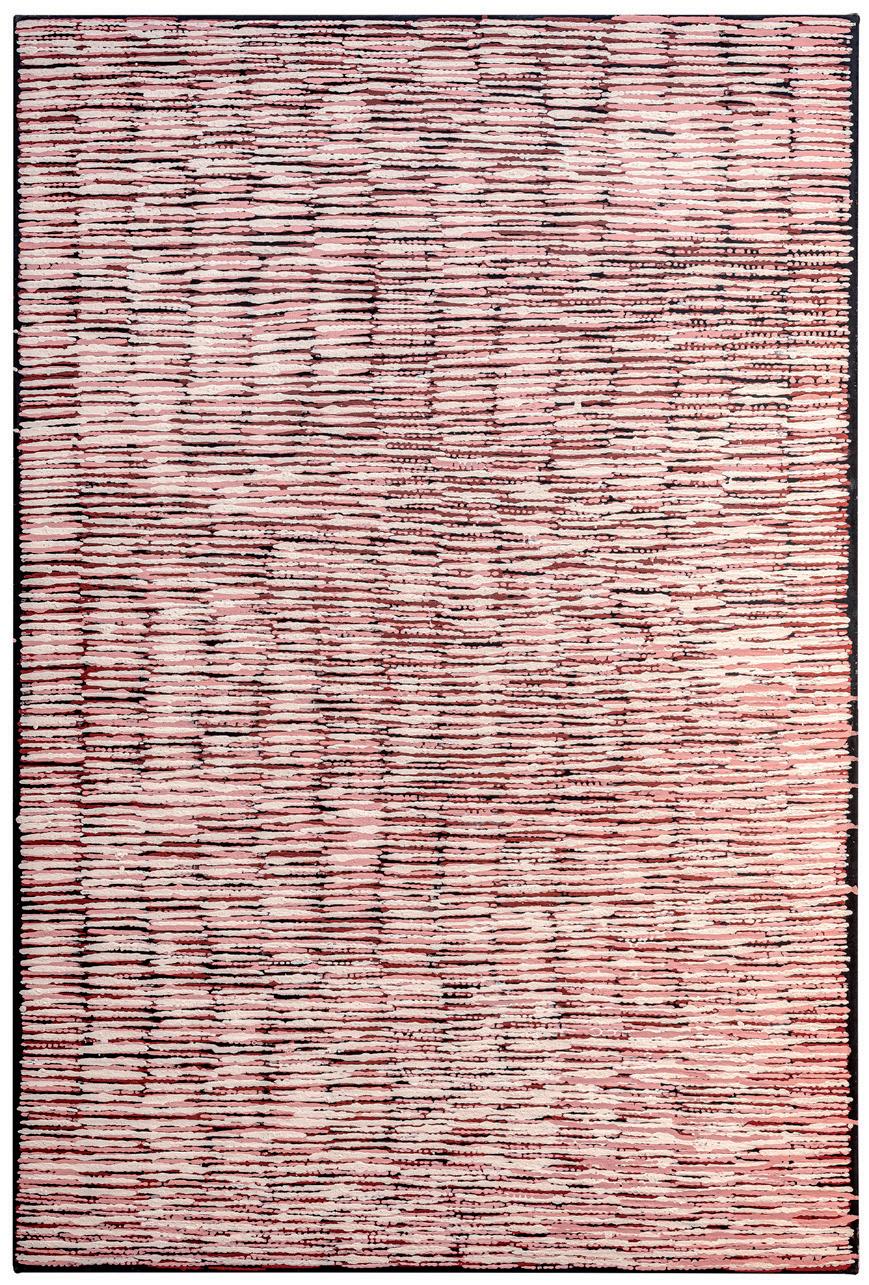

Each work in Yoi carries with it an unwavering freight of cultural significance, made all the more emphatic by an incomprehensibly deep and spiritual connection to homeland. Often painted with natural ochres, the very physiognomy of the works echoes that of the landscape. For example, Alison Puruntatameri’s Winga paintings, meaning “tidal movement” or “waves”, allude to the rhythmic movement of the natural world through a gestural bodily presence – an organic reaction to her surrounding landscape. This affectation, enacted upon the artist, is recalled by the paintings’ materiality. Accumulations of vibrant natural ochres on a black background, applied with a Pwoja Comb, parallel the luminescent reverberation of the waters and coastlines around the islands. The textural layering of paint, applied in a dense linear formation, attacks the linen as though waves crashing

upon the shore. This motion speaks to the continuity of natural processes which subsequently situates an interpretation of her art within the passing of time and a broader cosmology. Tiwi Art presents a unique ode to nature. Remarkably, this has contributed to data showing changes in climate-sensitive biophysical systems that would otherwise remain undetected by instruments conventionally used for monitoring climate change. A reliance on bush harvest, natural materials and medicinal plants, as well as the centrality of the environment to a sense of cultural identity, has attuned Tiwi Islanders to any changes that may take place and fostered a symbiotic relationship, centred around stewardship, over many years. As a result, there is both an individual and collective commitment to sustainable management of lands. Indigenous observations of geomorphological changes, often documented through art, have hence also contributed to a post-colonial regaining of ownership.

There is, in Tiwi Art, a sense of the antique, not only by matter of the sheer age of this tradition but by the intricacies and nuances which unify all aspects of life on the islands. Though ostensibly non-representational, Tiwi abstraction is such that the voices of those who make it persist and urge us to enjoy the movement which has ended up here. An aetiological comparison offered by the Elder Pliny, attempts to illuminate a practice of interconnectivity within the Western imagination, but also, aids us in comprehending the emphasis on continuity within contemporary Tiwi Art: “The songs and the dance connect to our ancestors and the Wulimawi (Elders)… As we are moving forward, we still need to connect. The song connects to the dance. The dance, the body painting and the ceremonial body ornaments connect to the art we make.” Moreover, the symbiotic relationship between people, land and sea offers unprecedented insight into climate concerns, as such imbuing Tiwi Art with an all the more significant sense of contemporaneousness.

Just as we look to a classical past to explain the present, in the words of artist Pedro Wonaeamirri: “... the old and the new coming together is our story, from Parlingarri (Long Time Ago) to today, moving forward but always remembering.”

Each work in Yoi thus represents a transcription of the almost inexplicable within the not-so opposing frameworks of tradition and progress in contemporary Tiwi Art.

REFERENCES

Jon Barnett et al., ‘Winga Is Trying to Get in: Local Observations of Climate Change in the Tiwi Islands’, Earth’s Future 11 (March 2023), 3.

Tiwi People, who were originally spread out across the islands, were placed into three settlements by colonisers. Once noted for their physical health at the time of European contact, they now suffer from a range of illnesses, including very high rates of kidney disease, which result in a death rate that is six times that of the

Australian mainstream population. Another consequence was the introduction of destructive non-native species, lacking in natural predators. Now, however, the Tiwi are the legal owners and custodians of the land.

Barnett et al., Ibid

David Sequeira, Yoyi (Dance): Communicating Tiwi Knowledge around Change, Continuity, and Tradition (University of Melbourne, 2022), 2:55, https://youtu. be/CR2NzkebpW0, (accessed 4 January 2024).

The Pukumani ceremony, for example, considered the most significant of a person’s life, ensures the transition of a spirit into the next life. Yoi might reflect an expression of grief, narrate the life of the deceased, or even be performed by kin, whilst Jilamara provide protection against recognition by the spirit of the deceased.

Guy Allain (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Pliny. Natural History, Volume IX: Books 33-35 Translated by H Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 330, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938), XXXV, 81-83.

David Rosand, “Criticism, Connoisseurship, and the Phenomenology of Drawing,” in Drawing Acts: Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 8.

Ibid

Guy Allain (in conversation with the author), 2024.

Judith Ryan and James Bennett, In Conversation, Milikapiti, (1994), in, Judith Ryan, “The Raw and the Cooked: The Aesthetic Principle in Aboriginal Art”, NGV Art Journal, 36 (June 2014).

The Pwoja is a traditional Tiwi Comb. Unique to the Tiwi People, each one is individually made from ironwood to suit the needs of each artist. Multiple lines of dots are created by dipping the Pwoja’s teeth in the ochre colours and then pressed onto the surface of the canvas to create this mark-making effect.

Pedro Wonaeamirri, Mintawinga Amitiya Wurrungura: from Bark to Moving Image, (University of Melbourne, 2022).

Ibid

“For Tiwi People, to sing is to dance is to paint.”

2 3 4 7 8 9 10 11 12 29

(1997).

Left: Alison Puruntatameri, Winga II (Tidal Movement/ Waves) 2020, ochre on linen, 120cm x 80cm. Image courtesy of Studio Adamson.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 14 30

Right: Alison Puruntatameri, Winga IV (Tidal Movement/ Waves) 2021, ochre on linen, 120cm x 180cm. Image courtesy of Studio Adamson.

31 32

(Left) Carol Puruntatameri, Yipali & Purrukupali II, 2023, ochre on canvas, 180cm x 120cm, (middle) Lucinda Puruntatameri, Pupuni Jilamara I 2023, ochre on canvas, 120cm x 80cm, (right) Carol Puruntatameri, Yipali & Purrukupali I 2023, ochre on canvas, 180cm x 120cm. Image courtesy of Studio Adamson.

WE AT JGM GALLERY ARE DELIGHTED TO ANNOUNCE THAT ‘YOI’ WILL TRAVEL TO SAATCHI GALLERY, WHERE IT WILL BE ON DISPLAY FROM THE 2ND OF AUGUST UNTIL THE 21ST OF SEPTEMBER.

CONGRATULATIONS TO THE EXHIBITING ARTISTS, AND TO THE MUNUPI ARTS & CRAFTS ASSOCIATION.

Saatchi Gallery exterior, 2020. Image courtesy of Matthew Booth. 33

34

In The Studio With Dominic Beattie & Olly Fathers

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING TANGRAM, JULIUS KILLERBY (JGM GALLERY’S ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR) VISITED DOMINIC BEATTIE AND OLLY FATHERS IN THEIR LONDON STUDIOS. THE VISITS WERE AN OPPORTUNITY FOR BOTH TO DISCUSS THEIR WORK AND THE UPCOMING EXHIBITION. WHAT FOLLOWS IS A TRANSCRIPT OF THEIR CONVERSATION.

Olly Fathers in his South London studio, 2023. Image courtesy of Justyna Kulam. 36 35

JULIUS KILLERBY Dom, where does your interest in pattern come from?

DOMINIC BEATTIE It developed out of the abstract, geometric paintings I began making and exhibiting about a decade ago. The first purely pattern based works were a series of around 200 marker pen drawings I developed in 2016. Outside of my own practice, the inspiration usually comes from textiles, folk decoration and vernacular design.

JK Would you say that your subject in Tangram is, strictly speaking, pattern? It occurs to me that if one thinks of pattern as the repetition of the same shape at regular intervals then it would be difficult to describe your work in these terms.

DB The patterns I paint are a vehicle for colour and form to interact. They are loose and improvised, but usually always follow a regular logic. What interests me is the random combinations and the clashes they create side by side. So the subject isn’t really pattern. It’s the good and bad surprises between the patterns.

JK Do these designs come purely from your imagination, or are they based on something?

DB All the pattern based work I make is improvised on the spot. Sometimes I may look to an earlier work for inspiration if I have a creative block but that is rare. Colours, shapes and the repetition are usually spontaneous.

JK Olly, do you often view your real-world surroundings geometrically? Your work almost reminds me of diagrams of The Golden Ratio, which are then superimposed onto landscapes and representational compositions.

OLLY FATHERS I often observe how we use the geometric shapes of buildings and other man made structures to perceive our position in a space. However, the artworks generally aren’t a direct reference to actual landscapes.

JK What are you trying to express through the repetition of certain shapes and designs? Does the repetition have conceptual implications?

execution is very different which is why we thought the pieces would compliment each other so well.

JK What is a Tangram and why is it the title of the exhibition?

DB It’s a geometric kids puzzle and it felt an appropriate title because of the simple shape collating nature in our works and the feeling of infinite combinations.

OF We spent a long time thinking of a title for the show and had a variety of different ideas, some relating to building and construction. When we were discussing how we piece our works together, however, we both mentioned that it was like putting together a puzzle. Dom then mentioned a Tangram, which made perfect sense.

JK Dom, I notice that some of your works are divided into multiple panels. Does this reference the structure of a Tangram?

DB Not really. It’s more a practicality of making large work in a London studio. Modular making is the only way that I can make things for nice big gallery walls. This necessity has fed back into the work in a way, making it more patchy, or collage like.

“each series of works I make is defined by a set of rules, which make it somewhat coherent. within those rules, spontaneity and improvisation always occur and give the work life. without the rules, the work would be random and incomprehensible and without the chaos it would be dead.”

- Dominic Beattie

JK A Tangram would seem to suggest compositional parameters that you have to work within. Do you both like placing your process within certain constraints?

DB The constraints come naturally when you make this sort of work. If you go too wild it becomes unreadable.

OF Yes, I think in these works in particular I use a certain selection of shapes. I enjoy the challenge of creating different compositions within this constraint as the restriction almost makes way for more creativity.

clearly within a space high in energy and pattern. In the making process I usually explore multiple versions of designs that would then be refined until I’m happy with a composition that, for me, feels balanced and stylistically fits with my intention. At the same time, I’m always thinking what woods would work well with the design, as the textures of the grain and natural variations in colour are really key. They can change how the design feels completely. The making process takes up a large portion of the process as the works are hand cut and with point millimetre space for error, which at times can be quite gruelling.

DB For me it’s just lots of making and experimenting with materials and ideas until I generate something solid. If I like what I’ve made I will make more pieces in the same manner, with variations to further explore what it is. When it becomes a body of work, and if I get offered a show, I will try to imagine it in the space and add more site specific pieces if necessary.

JK I’m not sure if you’ve heard of it, Olly, but I see parallels between your work and The Ship of Theseus. In that paradox, the question is asked whether a ship remains the same if all its constituents have been replaced or altered? Many of your works seem to be the same, except for the grain and colour of the timber. They seem to rhyme, but never repeat. Would you say it’s accurate to compare your conceptual concerns with The Ship of Theseus?

a lot of similar interests in art and our approach to making artworks. We both have ideas behind our practice but it’s come about from years of commitment to developing as makers. This exhibition allows the work to show that.

JK How does the work in this exhibition differ from your previous work?

DB The smaller works I made for Tangram are very new. They are cut from the larger Modular Window installation. The painting was already done, so the creative element in making them was to decide upon a permanent combination of patterns and cut and paste them together. Although I have made many assemblages before, this felt different because it involved more looking than making.

OF All the pieces I made for this show are part of the same series of work and only use two different veneers for each piece. I’ve also been very excited to introduce sculpture into this body of work, which is the first time I’ve seen the works realised in 3D. This really made me view the compositions from a different angle. I found my eye gravitating toward the negative spaces in between these 3D forms, or the new surfaces created in the sides of the protruding forms.

OF I generally use simple primary shapes because we relate to these very instinctively. Perhaps that’s because this is how our relationship with shapes starts. Their simplicity also allows for a lot of playful freedom. Although my aesthetic is often confined to a set number of these primary shapes, there’s a lot of freedom in how they come together to create these compositions. To me, they speak very differently to one another.

JK Though your conceptual concerns are similar, would you both agree that your application not only differs, but is almost an exact inversion of the other? Dom’s work, at least to me, seems to convey a deviation from the meticulous designs in Olly’s work. By extension, I feel that one conveys chaos and the other order. Or is that perhaps too reductive?

DB I think we both come from a place of formal abstraction, and we both think in terms of building a work, rather than painting it. The outcomes are very different. Olly’s work is natural in material but almost industrial in its execution and final form, whereas mine is totally synthetic in material and colour, but completely from the hand in how it’s made and looks. It’s a funny inversion.

OF Yes, like Dom said, we come from a similar mindset but approach the making in a very different way and with a different aesthetic. Visually, there are similarities – geometric shapes, a sense of construction and repetition – but the

JK I’m not exactly sure why, but in looking at both your works, I often wonder what the other potential geometric arrangements could be? It’s as though you’re both encouraging the audience to think of other potential compositions. Is this deliberate?

DB My work often has an endless feeling, like it could continue off the edge forever, or a series could grow indefinitely. Sometimes I see painting as puzzle making, and with that element of playing there is definitely an infinite combination vibe.

OF For a lot of my pieces I really like to encourage the viewer to look at the work and imagine movement and balance. For this show, there’s a very obvious comparison of playing with tone and composition in the inverted pieces. The shift of colour really makes you read the arrangement in a completely different way and I love that. Even the repositioning of one element can allow the arrangements to feel different entirely.

JK What is your process, from the inception of an idea to it hanging in the gallery space?

OF For a show like this I wanted to create a series of works that all relate to one another. In this case, I knew Dom was going to have a large installation piece that was bright in colour and pattern so I wanted to create pictures that would work well in unison with this. I decided early on that I wanted to focus on a two tone palette for the works. I felt this would help the compositions to be read

OF Yes, I think that’s a nice parallel to relate to the work. Even if I intended to make two identical works, I feel I could never achieve this, as I’m working with a natural medium. The grain, colour and texture of the wood is always unique to the piece. There’s a nice contrast to the very bold primary shapes I use in the designs which shout from afar, to the quieter subtleties of the wood grain that only really starts to sing out when you look closer or live with the piece for a long time.

JK How do you decide which colours or pieces of timber you are going to use?

OF For this show I knew I wanted the pieces to be two toned so as not to clash with the vivid colours of Dom’s pieces. That was my starting point. When I choose what wood veneers I want for a piece it’s always a mixture of what works chromatically and texturally.

JK Have you both reached any conceptual conclusions by putting this exhibition together?

DB I don’t think it’s evident in my work because visually it’s very full on but working with Olly has reinforced my belief that simplicity is key. Our works are complex in some ways, like their development and fabrication, but ultimately they are visual, not conceptually driven and that is enough.

OF I’ve known Dom for a long time and besides liking his work, we share

JK Who are some of your favourite artists?

OF Some of the minimal artists from the 1960’s – Ellsworth Kelly, Fred Sandback, Frank Stella – I also take a lot of inspiration from architecture and design, such as the Bauhaus, mid century design, and the Memphis design movement.

DB Patrick Caulfield’s work was my portal into fine art so he will always be a main favourite. Other big influences are Paul Feeley and John Wesley. Now I look more at outsider and folk art... it surprises me more than contemporary art.

JK Dom, there seems to be a slight contradiction in your work between the subject that inspires it – quilts and stained glass windows – and the way that you paint. We are used to viewing textiles and stained glass windows within meticulous arrangements, but your paintings are distinctly gestural. What do you think the effect of this is?

DB The pattern based works are made on an invisible and imagined grid. Inside that boundary I can be loose and tight at the same time. I’m not sure of the effect it has. I hope it looks fresh and surprising.

JK For both of you, does your work, in some sense, make itself? In other words, once you’ve decided on the geometric and chromatic constraints, does the work almost self-generate? Or is there a high degree of chance and accident that effects the outcome?

DB For me both things are true. Each series of works I make is defined by a set of rules, which make it somewhat coherent. Within those rules spontaneity and improvisation always occur and give the work life. Without the rules the work would be random and incomprehensible and without the chaos it would be dead.

37

38

Previous page: Dominic Beattie, Window Painting V, 2023, spray paint on wood, 198cm x 229cm.

Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

Tangram opening night.

Previous page: Dominic Beattie, Window Painting V, 2023, spray paint on wood, 198cm x 229cm.

Image courtesy of Daniel Browne.

Tangram opening night.

39 40

Image courtesy of György Körössy

OF For me, the work has to be planned out precisely to ensure all the cuts and joins fit together perfectly, so there is little room for change in the making process. Sometimes things can happen which require adjustments but the necessity to overcome these issues and problem solve makes the process more interesting for me.

JK Was it always the plan to exhibit your work alongside each other? What are the conceptual implications of showing your works together? What do they do in tandem?

DB We have shown together a few times before in group exhibitions but this is the first focused duo show. There is always a similar mindset towards making and ambition between us. Together, I think you can see a radically different approach to craft and material exploration in the same language of geometric abstraction. It’s a show about parameters and opposites.

OF Like Dom said, we’ve known each other for a long time and shown together before. We both knew we had common interests and approaches to making and thinking about artworks so it made perfect sense to show together. I think in tandem they just champion the enjoyment of making and that’s conceptually all we ever needed.

JK Olly, could you speak a bit about the two tone works arranged in a grid? What are you trying to express through that work?

OF I actually wasn’t intending on making the pieces in the grid to include inverted versions of one another. However, in the making process I kept finding myself drawn to these reversed versions of the work. It changed how I viewed the piece and its companion piece completely. In previous works I’ve been very drawn to the off-cut shapes created by making my works. They are kind of accidental forms that explain, and show evidence of, the making process. The smaller works displayed in a grid almost act as maquettes for larger works and only when you view them in a group do they give that sense of experimentation. There’s an infinite number of combinations or possibilities when arranging the designs, so I wanted them to really feel like a snapshot in that process of shifting and moving the compositions about.