TRIBUTE

Tobie Kaplan: The Woman Who Helped Shape Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s Enduring Legacy By Tova Cohen

FROM THE PAGES OF JEWISH LIFE

The Editor’s View By Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan

HEALTH AND WELLBEING

My Journey with Dementia

By Wally Klatch, as told to Nechama Carmel

Dementia in Halachah By Rabbi Dr. Jason Weiner

Writing the Final Chapter: A Torah View on Facing Mortality By Rabbi Daniel Rose

When Dad Has Dementia By Rachel Schwartzberg

COVER STORY Voices of Valor: Women advocating for Israel and the Jewish people

The Pen Is Mightier than the Sword: Fay By Barbara Bensoussan

Fighting the Good Fight: Kassy Akiva By Sandy Eller

Getting to the Root of the Story: Meira K. By Merri Ukraincik

Advocacy on a Higher Level: Tziri Preis By Barbara Bensoussan

One Teen’s Fight against Antisemitism: Sofie Glassman By Yehudis Litvak

That Girl Who Loves the Jews: Adina Fernandez By Sarah Ogince

Twenty Years Later—Remembering the Uprooting of Gush Katif By Carol Ungar

Debbie’s Story By Debbie Rosen, as told to Toby Klein Greenwald

From Gush Katif to the Rebuilt Ganei Tal By Moti and Hana Sender, as told to Toby Klein Greenwald

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER Seeing the Light

MENSCH MANAGEMENT

How Decisions Are Made: A Jewish Perspective on Authority vs. Influence By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

JUST BETWEEN US No Labels, No Limits By Rabbi Yisrael Motzen

IN FOCUS

Yes, There Are Jews in Charlotte By Adina Peck

KOSHERKOPY

Test Your Kosher Travel IQ By Rabbi Donneal Epstein

LEGAL-EASE

What’s the Truth about . . . Saying G-d’s Name in the Course of Torah Study? By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

THE CHEF’S TABLE

Juicy Fruits: Enjoying the Sweets of Summer By Naomi Ross

NEW FROM OU PRESS

The Eternal Conversation By Rabbi Jonathan Sacks

BOOKS

The Great Z’manim Debate: The History, the Science, and the Lomdus By Rabbi Ahron Notis

Reviewed by Rabbi Yaakov Hoffman

Hakham Tsevi Ashkenazi and the Battlegrounds of the Early Modern Rabbinate By Rabbi Yosie Levine

Reviewed by Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein

Letter and Spirit: Evasion, Avoidance and Workarounds in the Halakhic System

By Rabbi Daniel Z. Feldman

Reviewed by Rabbi Moshe Kurtz

REVIEWS IN BRIEF By Rabbi Gil Student

LASTING IMPRESSIONS Keeper of the Tefillin

By Dr. Ethan Schuman

Cover Design: Bacio Design & Marketing, Inc.

Cover Photo Credits:

Top middle: Dani Sarusi

Bottom left: Dina Brookmyer

Bottom right: Chana Stuart

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION

jewishaction.com

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Associate Editor Sarah Weiner

Associate Digital Editor

Assistant Editor Sara Olson

Rachelly Eisenberger

Literary Editor Emeritus Matis Greenblatt

Rabbinic Advisor

Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz

Book Editor

Rabbi Gil Student

Book Editor

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Moishe Bane • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg

David Olivestone • Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Menachem Genack’s heartfelt tribute to Joe Lieberman (“Reflections on the Life and Legacy of Joe Lieberman—On the Occasion of His First Yahrtzeit,” spring 2025) brought tears to my eyes because like Rabbi Genack, John McCain and countless others, I admired and loved Joe. Joe’s principles, his courage, his faith, his sincerity, his modesty and his sense of humor defined one of the very best citizens ever to serve our country. How we who knew Joe cherish his memory and mourn his loss!

Gordon Humphrey

Former United States Senator Concord, New Hampshire

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Moishe Bane • Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

David Olivestone • Gerald M. Schreck • Dr. Rosalyn Sherman Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman • Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Design 14Minds

Advertising Sales

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Copy Editor Hindy Mandel

The OU is to be commended for its project to supervise and standardize the kashrut of mezuzot, as described in Rachel Schwartzberg’s article (“The Making of a Mezuzah,” spring 2025). One factor in the need for this supervision is the marked increase in demand. The article attributes this to several circumstances, including, as Rabbi Moshe Elefant puts it, “We simply have more doorways than ever before.”

Subscriptions 212.613.8140

Design

Bacio Design & Marketing, Inc.

ORTHODOX UNION

Advertising Sales

President Mark (Moishe) Bane

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

ORTHODOX UNION

Vice Chairman of the Board Mordecai D. Katz

President Mitchel R. Aeder

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry I. Rothman

Chairman, Board of Directors Yehuda Neuberger

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Gerald M. Schreck

Vice Chairman, Board of Directors Morris Smith

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

It should be noted that most of these doorways are in Israel where, almost without exception, the approximately eight million Jews living here have mezuzot on their doors. That’s true also for each and every room of all Israeli offices, stores, restaurants, hotels, hospitals, schools, museums and other public buildings, and there’s a huge amount of new construction going on here all the time.

Seeing mezuzot everywhere you go is just one more constant reminder that we live in a Jewish country, and that the entire country is suffused with a Jewish identity and consciousness that cannot be duplicated anywhere else in the world.

David Olivestone Jerusalem, Israel

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry Orlinsky

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer Arnold Gerson

Senior Managing Director

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Jerry Wolasky

Rabbi Steven Weil

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Executive Vice President Rabbi Moshe Hauer

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer

Rabbi Josh Joseph, Ed.D.

Chief Human Resources Officer

Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Chief Information Officer Samuel Davidovics

Managing Director, Communal Engagement

Chief Innovation Officer

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Rabbi Dave Felsenthal

Director, Jewish Media, Publications and Editorial Communications

Rabbi Gil Student

Director of Marketing and Communications Gary Magder

Jewish Action Committee

Jewish Action Committee

Dr. Rosalyn Sherman, Chair

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

Gerald M. Schreck, Co-Chair

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2018 by the Orthodox Union Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004

©Copyright 2025 by the Orthodox Union

40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Twitter: @Jewish_Action

Facebook: Jewish Action Magazine

Twitter: Jewish_Action Linkedln: Jewish Action Instagram: jewishaction_magazine

Liel Leibovitz’s article, “What Jews Really Want” (winter 2024) was really on the mark. What not-yet-religious Jews are really looking for, Leibovitz writes, is a “real, serious, meaningful, character-building challenge.” This reminds me of an experience I had about twenty years ago when I was working as a summer intern for a secular Jewish newspaper in Cleveland, Ohio. During the Three Weeks [the period of mourning the Churban when it is customary to refrain from haircuts and shaving], I along with my fellow intern, also an Orthodox Jew, stopped shaving. One of our co-workers, who was interested in learning more about Judaism, asked us about it. Feeling a bit uncomfortable, I responded with a humorous quip. Well, the co-worker was a bit taken aback and said, “So this is all just a joke for you guys!” His response hit me hard. He was looking for a more meaningful answer. A couple of years later, I came across an article written by the same co-worker about a Discovery Seminar he had attended, where he describes being very inspired. Yes, meaningful discussion is one of the best ways to bring Jews back to the fold.

Ariel Galian Beitar, Israel

In “Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin on Jewish Identity Post–October 7,” (winter 2024), Rabbi Bashevkin provides a troubling analysis of the state of Yiddishkeit in America outside of the ghetto walls. One thing was missing from his analysis: Chabad.

Chabad is already doing all the things that Rabbi Bashevkin correctly says needs to be done, and that is the entire focus of their movement.

The reason why no one else under the Orthodox umbrella has been able to even tangentially replicate Chabad’s success, their good ideas and motivations notwithstanding, is because a key ingredient of that success is missing: mesirus nefesh. What other group has young couples willing to move 1,000 miles away from the nearest minyan to set up shop?

Full disclosure: I am not affiliated with Chabad and my sons learned in Brisk, Mir, Ner Moshe and other Litvishe yeshivahs. But facts are facts.

Meir Zev Mark Beitar Illit, Israel

The recent collection of stories about people who have left the Orthodox fold (“Leaving the Fold: The OU’s new study provides insight into attrition,” spring 2025), and the role of families and schools—sometimes in conflict with each other over a child’s level of frumkeit—reminded me of something that happened in my life a few decades ago.

One of my colleagues was a proud but not-strictly-Torahobservant Jew, who had worked at a series of jobs with Jewish institutions.

This co-worker (I’ll call him Stan) and his wife sent their two young daughters to a Modern Orthodox day school in their New York neighborhood. At the same time, Stan, an avid basketball player, met his friends every Saturday, weather permitting, to shoot some hoops. I don’t know what Stan’s daughters told their parents when they came home from school, but I do know that one day he told me that his gamesplaying behavior on Shabbat sent an inconsistent message to his children—whom he wanted to take their Jewish studies seriously. Stan stopped the basketball on Shabbat. And no more shopping then, too. Soon, there was a higher level of kashrut in the family’s apartment. And Stan started going to Shabbat services each week.

Not familiar with tefillin (he had learned about them at his bar mitzvah but had not diligently put them on since then), he had me show him the procedure. I used a pair I kept in my desk.

In time, Stan retired from his job at my office, and the family made aliyah, settling in Jerusalem. Now, Stan attends a daily Torah study session every day. And his daughters are committed, Orthodox Jews—because their parents didn’t want

to send mixed messages about the importance of modeling at home the lessons about Judaism that the daughters were learning in school.

Steve Lipman

Forest Hills, New York

Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet’s Teaching Career

In Rabbi Ron Yitzchok Eisenman’s review of Rakafot Aharon: Timeless Halakhah and Contemporary History (spring 2025), the reviewer states that Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff started teaching “when Richard Nixon was president.” I was in his last pre-aliyah shiur at Yeshiva University’s High School for Boys (MTA) which began in September, 1968, when Lyndon B. Johnson was the president. In fact, when Rabbi Rakeffet began teaching at MTA, John F. Kennedy was president. But, in the interest of completeness, when “Arnie Rothkoff” was teaching Torah to public school kids in the Bronx, Dwight D. Eisenhower was still president. In short, his teaching career has spanned thirteen administrations (fourteen, if you count Donald Trump twice). Very impressive indeed.

David Gleicher

Jerusalem, Israel

[Ed. Note: The statement about Richard Nixon was an editorial error and did not originate with the writer.]

As a longtime admirer of both Rabbi Aaron RakeffetRothkoff and Rabbi Ron Yitzchok Eisenman, I found the review of the former’s book, Rakafot Aharon: Timeless Halakhah and Contemporary History, especially enjoyable. Rabbi Eisenman writes regarding the Rav’s opinion on the Langer case: “Rabbi Rakeffet quotes a ‘confidant’ of Rabbi Soloveitchik who maintains that the Rav supported Rabbi Goren privately, but the fact is that the Rav did not say anything publicly on the subject.”

I believe that the Rav did address the subject publicly, and he was clear in his opposition to Rabbi Goren’s heter In his well-publicized speech in 1975 decrying the potential annulment of kiddushin, the Rav noted that certain halachic problems are unsolvable. (Audio of this portion of the speech is available on YUTorah.org, titled “Gerus & Mesorah—Part 1,” at approximately thirty-nine minutes.)

The Rav said, “However, if you think that the solution lies in the reformist philosophy, or in an extraneous interpretation of the halachah, you are badly mistaken. It is self-evident; many problems are insoluble, you can’t help it. For instance, there was the problem of these two mamzerim in Eretz Yisrael—you can’t help it. All we have is the institution of mamzer. No one can abandon it—neither the Rav HaRoshi, nor the Rosh HaGolah.

What can we do? This is Toras Moshe . . . . This is kabbalat ol malchut Shamayim . We surrender.

It cannot be abandoned. It is a pasuk in Chumash: ‘Lo yavo mamzer bekehal Hashem.’ It’s very tragic; the Midrash already spoke about it, ‘vehineh dimat ha’ashukim’ [and behold, the tears of the oppressed], but it’s a religious reality. If we say to our opponents or to the dissident Jews, ‘That is our stand’— they will dislike us, they will say we are inflexible, we are ruthless, we are cruel, but they will respect us. But however, if you try to cooperate with them, or even if certain halachic schemes are introduced from within, I don’t know; you would not command love, you would not get their love, but you will certainly lose their respect. It’s exactly what happened in Eretz Yisrael. What can we do? This is Toras Moshe, and this is surrender. This is kabbalat ol malchut Shamayim. We surrender.”

The Rav is clearly referring to the Langer case, an example of something “unsolvable” and that “you can’t help it,” not even the Rav HaRoshi. He seems to be using Rav Goren’s heter as an example of a “halachic scheme introduced from within.”

According to the Rav, the more appropriate response would have been to surrender to halachah; the attempted heter was a futile attempt to coax love out of dissident Jews.

Jacob Sasson Passaic, New Jersey

Regarding shiurim I gave about a half century ago on the “brother and sister controversy,” I can tell you that my knowledge of the Rav’s position was the result of conversations with two distinguished colleagues and friends, namely, Rabbis Aharon Lichtenstein and Emanuel Holzer. They both explained to me the Rav’s halachic position and why he did not go public. Their information both verified and complemented their approaches.

Regarding the Rav’s speech in 1975, I am very well aware of this talk. I actually was the first one to publicize it in Israel, as Rabbi Holzer sent me a recording. I recreated the speech with all the sources at that time. I believe that the Rav is not referring to Rabbi Goren’s pesak per se but rather to the atmosphere created by the public discussion about the halachic status of the children. In the media of that period, endless personalities advocated for the abrogation of the laws of mamzeirut. I lived through that period, and I recall my many public lectures explaining these sacred laws as a bastion of holiness and the basis of the Jewish family. I still recall my pain at the time when I heard some very influential individuals decry “Devar Hashem zu halachah—the word of G-d, this is halachah” (Gittin 60b).

However, one must recall that this lecture was not about the brother and sister. It was rather a refutation of a proposal that was made at that time to establish a Beit Din in New York that would retroactively annul marriages when the husband refused to give a get or made excessive demands upon the woman. I discuss this topic at length in Rakafot Aharon, vol 4. I gained much more knowledge about this topic over the subsequent generations. I have returned to this topic and lectured on it many times in the Gruss Kollel. Much of it is available on YUTorah.org.

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org. Letters may be edited for clarity.

Transliterations in the magazine are based on Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Thus, the inconsistencies in transliterations in the magazine are due to authors’ or interviewees' preferences.

This magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

Having kept a kosher home for nearly thirty years, over time, I have grown increasingly concerned about the ingredients in many kosher products. It is alarming to see how many of these foods are filled with unhealthy, even toxic, additives. Compared to other countries, the United States is experiencing significantly higher levels of morbidity, and I believe this is closely linked to the overwhelming presence of artificial and toxic chemicals in our food supply.

It is no secret that millions of Americans suffer from chronic illnesses, and these have dramatically increased over the decades. Many studies have shown a direct correlation between the rise in these diseases and the widespread use of synthetic chemicals in packaged foods. Notably, the spraying of glyphosate on commercial crops starting in the mid-90s has been linked to many chronic health issues. This is just the tip of the iceberg, as ingredients like artificial dyes and chemicals are still permitted here, despite being banned in other countries. Why is this allowed?

In the small Jewish community where I live, we have limited kosher options, but organic, all-natural whole foods are available in most grocery stores. Yet, when I visit larger Jewish communities with numerous kosher markets, I am dismayed to find that these healthier options are virtually nonexistent. There are countless processed kosher products with artificial, unhealthy ingredients on their shelves. Why?

With the growing focus on public health and wellness, I truly hope the kashrut industry—together with food manufacturers and kosher markets—can become a voice for promoting and providing healthier food options. We need kosher products that are free from harmful, artificial ingredients.

Our spiritual and physical health are interconnected, so it’s baffling that Jews seem to separate this concept when it comes to consuming food. Kashrut is vital to the Jewish people, but keeping kosher should also support our physical wellbeing.

Shoshana Rivkah Lulky Little Rock, Arkansas

OU Kosher Responds

Thank you for contacting the OU.

The OU is a kosher-certifying agency. Health aspects of food production are beyond our area of expertise.

Halachah is extremely sensitive to matters of health, to the extent that chamira sakanta meisura (life-threatening health concerns generally take precedence over halachic restrictions). Nonetheless, as a kashrus agency, the expertise of the OU is limited to the domain of kosher supervision, and the evaluation of the health status of a facility is beyond the scope of the OU’s mandate. Health inspectors receive extensive training before they are qualified to perform inspections and evaluations, and OU mashgichim are not trained in this area. There are government agencies that are entrusted with the responsibility of ensuring the safety of food items, and the OU certifies products that meet the criteria of public health and safety requirements.

Rabbi Chanoch Sofer

Webbe Rebbe, OU Kosher

With heartfelt appreciation for his many years of thoughtful guidance, creativity and dedication on the Jewish Action Editorial Board, we warmly congratulate David Olivestone on his new role as Contributing Editor. We’re excited to continue benefiting from his voice and vision in the pages of the magazine.

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

We write a lot about challenges, but this message focuses on opportunities. It derives from having spent a recent Shabbat with the staff of this year’s OU-NCSY summer programs. These hundreds of religiously engaged young men and women were preparing to spend many weeks with thousands of Jewish teens with whom they will share their love for G-d, Torah and the Jewish people. Hundreds more will do the same on our Yachad and Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus (JLIC) summer programs.

In our morning Amidah prayer, we turn to Hashem and ask Him to bless us “be’or panecha—with the light of Your face.” While this can be understood as a metaphorical request for G-d to visibly demonstrate His love for us, it may also be a request that our own faces exhibit a heavenly glow like that of Moshe, whose face

vice

radiated brilliantly when he returned from his intimate and transformative experience with G-d at Sinai.

Those young people visibly carry that blessing. Their spirituality glows and their faces radiate goodness. Being with them was uplifting, hopeful and enlightening on several fronts.

Organizations tracking incidents of antisemitic harassment, vandalism and assault in the United States report a continuous rise in those numbers. Evidently, all the Jewish communal activism to reduce antisemitism is not proving effective. One might therefore say we are losing the battle, but that is only correct if you define victory by lessening manifestations of Jew-hatred. Recognizing, however, that the antisemites’ ultimate goal is to, Heaven forbid, weaken or destroy Jews and Judaism, then it is evident that we are winning as, with Hashem’s help, we witness a repeat of the historic phenomenon that first emerged during the original anti-Jewish persecutions in Egypt: “The more they were oppressed, the more they grew and expanded.”1

Engagement in Jewish life has indeed surged since the attacks on Shemini Atzeret 5784, October 7, 2023. Broad communal studies2 have documented that this was not just an immediate post–October 7 spike; the growth has continued since then. Within the OU, we see this on many fronts, including, for example, a dramatic 50-percent increase in NCSY’s Jewish Student Union (JSU) public school clubs throughout the country, and elevated Torah engagement of both men and women on all our OU platforms.

The antisemites are doing their best to weaken and to destroy Jews and Judaism, but throughout the world

we are responding to the hostility by doubling down on being there for each other and elevating our engagement in Torah and mitzvot, the essential identity of the eternal Jewish people. The smashed idols of failed contemporary ideals have made room for many Jews to return home to Jewish community and values. From the Orthodox to the unaffiliated, October 7 and October 8 have generated a wonderful backlash of prosemitism.

Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin (the Netziv of Volozhin), in his classic essay on antisemitism, She’ar Yisrael, 3 advanced a thesis4 that antisemitism is G-d’s way of protecting and preserving Jewish identity. In the Netziv’s wry reading of Vehi She’amda, 5 we declare that those who in every generation set out to destroy us have, in fact, prevented our destruction by disrupting our assimilation into the surrounding society and driving us to come home to G-d, Torah and Klal Yisrael. The surge in Jewish engagement following attacks on the Jews here and in Israel is not an incidental reaction to these events but their Divinely intended result. That renewed positive energy is visible in these young men and women. While we often wring our communal hands bemoaning the prevalence of religious disconnection and complacency, the NCSY summer staff are spiritually engaged and ambitious. The light in their eyes reflected their vibrant bond to Judaism—apparent in the way they davened and sang, related to others and carried themselves, and eagerly learned Torah and wisdom from the assembled faculty. Sincerity, passion and purpose were everywhere. “Lo alman Yisrael the Jewish people are not bereft.”6 A community that has raised such a dynamic force of glowing young men and women is the farthest thing from bereft, and the experience of the past

nineteen months has made their glow grow even brighter. That glow is a key indicator of success in the battle against antisemitism. With Hashem’s help, we are winning.

Who Will Educate the Next Generation?

What made these young people shine? Undoubtedly each of those stars has a back story with unique supporting actors, including parents and teachers, communities and schools, mentors and informal experiences leading them to the meaningful connection they have to Hashem, His Torah and His people. But the key element that produced that light in their eyes and brought them together this past Shabbat is their sense of mission to share the Torah they love with people they care for. Like Moshe whose radiance was on display specifically when he was sharing Hashem’s words with the Jewish people,7 their glow reflects their eagerness to do the same. They are poised, motivated and empowered to make a real difference, leaving them no room for apathy or indifference. Their sense of mission is not a nice extra to look for in an excited group of camp counselors. It is core to our identity as believers and as Torah learners.

Rambam noted in his Sefer Hamitzvot8 that because people are naturally moved to share their passions, the mitzvah to love G-d includes within it the mandate to impart that love to others, “sheyehei shem Shamayim mitaheiv al yadcha so that the name of Heaven becomes beloved because of you.”9 Avraham was the primary example of this as he loved Hashem10 and was a driving force in bringing others to His service.11 The mission to share our faith with others is both a stimulant and an outgrowth of our ahavat Hashem (love of G-d).

Rambam similarly considers both the learning and teaching of Torah to be components of a single mitzvah, lilmod chochmat haTorah ul’lamda 12 One might trace this to the Rambam’s own citation13 of the Sages’ view that one’s love for G-d is best expressed

through the learning of His Torah. Torah study therefore adopts the same rules as the love of G-d, where having it and sharing it are inseparable. Can we really be thirsty for knowledge and engaged in learning without also being driven to share that knowledge?

This mission to teach is also an essential aspect of our Jewishness. In conveying the history of worship, Rambam speaks of how when Avraham discovered the One G-d, he proceeded to smash the idols worshipped by his contemporaries.14 Avraham, however, was not the world’s first righteous monotheist. Why had this smashing of the idols not been performed earlier by Shem and Ever, ancestors and predecessors of Avraham who also believed in the One G-d? Ra’avad suggests that they had not even been aware of the idols, whereas Rabbi Yosef Karo, in his Kessef Mishneh, explains that while Shem believed in the same G-d as Avraham, he only shared that belief with those who came to seek it from him, while Avraham was committed to proactively transforming the world and redirecting the faith of others. Ra’avad and Kessef Mishneh are presenting the two distinguishing elements of the Abrahamic and Jewish mission: noticing and caring about the religious well-being of others.

In his discussion of antisemitism, the Netziv takes note of the unusual choice of the term itself.15 When were we ever called Semites rather than Jews/Yehudim or Hebrews/Ivrim? He suggests that this appellation implies a reduced Jewish stature and worthiness and posits that part of the curse of antisemitism is the humiliation of our being seen by the world as undeserving of the loftier titles of Ivrim or Yehudim such that we can only be described as simple Shemites.

The Jewish community cannot be satisfied with Semitism, a faith that we observe and maintain but are not committed to share and inspire others with. If we are to be faithful to the vision and mission of Avraham, we must have a religious culture that inspires young and old to notice and

to care for the wellbeing and the Jewishness of other Jews. We cannot possibly have a dearth of people dedicated to teaching and caring for other Jews. Like Avraham, Jews should be sitting at the doors of our individual, familial and communal tents, scanning the horizon to identify individuals with whom we can share what we have to offer and rushing forward to share it with them.

This shining cadre of young men and women are doing just that, and we must hold them up as the children of Avraham and Sarah, examples of what a Jew is meant to be, to feel and to do, encouraging them and many others to nurture a lifetime passion to notice and care for the religious wellbeing of every member of Klal Yisrael.

I was far from the only one who saw the light in this remarkable group of young men and women. The hotel where the summer staff training was held simultaneously housed a group of Chareidi Israeli leaders currently positioned at crucial junctures of influence within Israel, in critical Knesset committees and government ministries and in local councils and mayoral offices. While the visiting group had been focused on protecting and strengthening their own community’s interests, they had come to the United States for a week-long mission to broaden their horizons and learn more about American Jewry, and they eagerly began and ended their Shabbat in the uplifting company of our summer staff. As they described it, their encounter with our young people and “the fire in their eyes” helped them see a broad and uplifting model of commitment to Klal Yisrael that was enormously impactful and the highlight of their week, leaving them wondering how they could learn from them and bring this secret sauce to their own children and students in whose eyes they did not always see that fire.

“Barcheinu Avinu kulanu k’echad be’or panecha—Bless us, our Father, all of us as one, with the light of Your

Serves: 6

Fleishigs Issue #59

A creamy base is all the rage and don’t skimp on the herbs — it makes this dish pop!

3 Persian cucumbers, diced

2 firm tomatoes, diced

3 radishes, diced

2 scallions, thinly sliced

½ cup mixed chopped herbs (parsley, dill and/or cilantro)

Juice of 1 lemon

½ teaspoon kosher salt, plus more to taste

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 (8-ounce) container Tnuva quark

Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

1. Toss cucumbers, tomatoes, radishes, scallions and herbs with lemon juice and salt.

2. Spread quark onto a serving plate or platter, then top with salad. Drizzle with olive oil and a sprinkle of pepper. Season with more salt, to taste.

Serves: 6-8

Issue #36

This is an Israeli take on the classic Greek salad — there’s saltiness from the feta, freshness from the vegetables, tanginess from the vinaigrette and texture from the roasted chickpeas.

FOR THE VINAIGRETTE:

¼ cup olive oil

¼ cup fresh lemon juice

1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

1 tablespoon honey

1 clove garlic, minced

1½ teaspoons za’atar, plus more for garnish

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½ teaspoon kosher salt

FOR THE SALAD:

6 cups mixed greens

1½ cups sliced tomatoes

2 Persian cucumbers, sliced

½ cup olives

1 cup crumbled Tnuva feta cheese, divided

1½ cups Roasted Chickpeas

1. For the vinaigrette, add all ingredients to a jar, seal tightly and shake until fully emulsified.

2. Toss greens, tomatoes, cucumbers and olives in a large bowl. Add ½ cup feta and vinaigrette; lightly toss to coat. Top with remaining ½ cup feta and a sprinkle of za’atar.

face.” In these times of deep division within Klal Yisrael, these glowing and radiant young men and women, admired by every Jew they encounter, are a blessing from Hashem and a glimmer of hope that we will triumph over antisemitism, inspire the teachers and students of the next generation, and eventually come together as one, as Klal Yisrael, noticing and caring for each other.

1. Parashat Shemot 1:12.

2. https://www.jewishfederations.org/ fedworld/federations-new-study-490865.

3. This essay was published along with the Netziv’s commentary on Shir Hashirim and is available here: https:// he.wikisource.org/wiki/%D7%A9%D7%9 0%D7%A8_%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8 %D7%90%D7%9C. An annotated English version of the essay was published by Rabbi Howard Joseph, z”l—father of Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph, OU executive vice president and chief operating officer—as Why Antisemitism? A Translation of “The Remnant of Israel” (New Jersey, 1996).

4. This thesis was also promoted by many others, including Rashi in his Sefer Hapardes Hagadol, who wrote of the “profound gratitude the Jewish people must express to G-d for generating hostility between them and the nations, as without that, they would assimilate with the nations and adopt their ways . . . therefore Hodu la’Hashem ki tov—give thanks to Hashem for He is good; His kindness is everlasting.”

5. She’ar Yisrael, chap. 3, and the Netziv’s Imrei Shefer commentary on the Haggadah.

6. Yirmiyahu 51:5.

7. Parashat Shemot 34:29-35.

8. Positive commandment 3.

9. Sifrei Devarim 32:2.

10. Yeshayahu 41:8.

11. Rashi to Bereishit 12:5.

12. Sefer Hamitzvot, positive commandment 11.

13. Sefer Hamitzvot, positive commandment 3.

14. Rambam, Hilchot Avodah Zarah 1:3.

15. She’ar Yisrael, chap. 5.

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

In the corridors of executive suites and community institutions alike, we often encounter the perennial question: What truly drives decision-making—authority or influence?

As one who has spent much of my career navigating both organizational and communal life, I’ve found that the answer lies less in theoretical models and more in the quiet spaces where trust, authenticity and human connection live. Authority is granted by title, by structure, by appointment. It’s the CEO’s corner office, the rabbi’s pulpit, the principal’s desk. It enables decisions, allocates power and often provides clarity in moments of ambiguity. But authority alone does not ensure followership. In fact, authority without influence breeds compliance at best— and resentment at worst.

Influence, on the other hand, is earned. It is the currency of credibility, consistency and character. Influence lives in the realm of the emotional, the relational and the deeply personal. Where authority might compel action, influence invites alignment.

There is a kind of secret hack to leadership—one that is often overlooked in textbooks and ignored by PowerPoint decks—and that is influence.

As the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks points out: “Power, in other words, is a zero-sum game: the more you share, the less you have. Influence is not like this, as we see with our Prophets. When it comes to leadership-as-influence, the more we share the more we have.”

Leadership is not necessarily about authority. In fact, decision-making often derives from those who use the power of influence.

A few relevant lessons about influence:

1. Influence is not about titles. In his piece “You Don’t Need to Be ‘the Boss’ to Be a Leader,” published in Harvard Business Review (February 2023), Matt Mayberry asserts that leadership isn’t tethered to a title—it’s tethered to behavior. Leadership means committing to personal growth, embracing your unique skills and connecting with others on a deep level. As Mayberry writes: “It all comes down to how we communicate, rather than what we communicate.” True leaders operate from a mindset of service, not status. Vulnerability, authenticity and empathy go a long way.

2. Influence is democratic. Influence is a precious commodity, but perhaps its most remarkable feature is that anyone

When people follow you not because they have to but because they want to—that is leadership worth having.

can wield it. It isn’t about job titles or seniority. Influence can come from the assistant who knows how to read the room better than anyone else, or the recent graduate whose insight in a meeting changes the whole direction of a project.

I’ve seen firsthand how a seemingly minor comment in the middle of a strategy session—offered without fanfare by an entry-level professional— reshaped the trajectory of a months-long initiative. At a much earlier stage in my career, a colleague loudly and derisively rejected an idea of mine outright, only for me to hear him advocating the very same concept six months later after I’d quietly and consistently introduced it in different ways over time.

3. Influence can be very quiet. When wielded wisely, influence is subtle and strategic. Less is more. It isn’t about dominating the conversation; it’s about knowing when to speak and how to listen. Sometimes it’s the softspoken comment in the middle of a meeting— or the conversation in the hallway between meetings—that shifts the mood, reframes the challenge or opens a new possibility.

Moshe Rabbeinu, perhaps the most authoritative figure and certainly the most significant leader in Jewish history, wielded immense power: he spoke face to face with Hashem, led an entire people out of slavery and received the Torah on Har Sinai. Yet his leadership was not defined by authority alone.

Consider the episode in Shemot 18:17–18 where Moshe’s father-in-law, Yitro, observes him adjudicating every case, large and small. Yitro advises:

Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph is executive vice president/chief operating officer of the Orthodox Union.

Eighty-nine percent of business schools offer classes on how to speak and present, with very few teaching how to listen. But listening is where influence begins.

“Lo tov hadavar asher atah oseh—What you are doing is not good. Navol tibol gam atah gam ha’am hazeh asher imach ki chaveid mimcha hadavar lo tuchal asohu levadecha—You are going to wear yourself out, both you and these people who are with you, for the matter is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone.”

He then proposes a decentralized model of leadership, empowering others to take on responsibility. Moshe, despite his Divine appointment, listens. He adapts. He shares leadership.

This moment is powerful. It shows that authority must be tempered with humility and that true influence often comes not from knowing all the answers but from knowing how and when to empower others. This is also exemplified by Yitro himself when he says, “Atah shema b’koli iatzcha—Now listen to me, I will give you counsel” (Shemot 18:19). He gives advice, not commands, provides direction, not directives.

This is Jewish leadership. Not dominance, but empowerment. Not command, but connection.

The Jewish communal world offers a unique leadership laboratory. We operate in mission-driven environments where authority is often diffuse and influence is everything. A shul president may have technical authority, but a long-time congregant or respected community member may hold more sway. An executive director might control the budget, but an educator or rabbi might hold the emotional loyalty of the stakeholders. This complexity can be frustrating—but it’s also beautiful. It demands leaders who are emotionally intelligent, spiritually attuned and deeply human. It reminds us that leadership is not a function of title but of trust.

Perhaps the prime exemplar of the use of influence over authority may

actually be Hashem. In Parashat Ha’azinu (Devarim 32:2), the pasuk says: “Ya’arof kamatar likchi tizal katal imrati kise’irim alei deshe v’chirvivim alei eisev—My doctrine shall drop as the rain, my speech shall trickle as the dew, as the droplets on the tender grass, as the showers on the herb.”

What a beautiful description of Hashem’s teachings and guidance—His Torah—trickling down to us, growing us gently, rather than hammering on our heads and pounding us into the dirt.

The Netziv points out that when Hashem delivers His message softly, with a kol demamah dakah (a voice of thin silence), we are compelled to lean in to listen deeper, to work harder on our end to receive it. The softer the voice, the deeper the impact.

Take a moment and ask yourself: Who influences you? Is it your parent, spouse, assistant, colleague, friend, sibling? And perhaps more humbling: Whom do you influence? Through your words, yes, but perhaps even more through your silence, your actions, your timing. We live in an age saturated with “influencers,” many of whom proclaim their status loudly. But when someone tells you they are an influencer, does it make you more, or less, likely to listen?

One of my personal role models for leading a life of influence was Chaim Shimon (Simon) Felder, z”l, whose first yahrtzeit will have passed when this essay is published. Reb Shimon was a true influencer. I’m not sure I even realized he was the mayor of our village on Long Island, New York, until he had already been in the role for a couple of years. I just thought everyone listened to him because he was smart. When he spoke with you, you felt he was taking you seriously, listening to you and focusing on you. No matter your age or who

you were in the community. And then, subtly, he would share his thoughts and ideas and opinions. And almost always I walked away with a new perspective, a new concept, a new way of thinking about a difficult issue or question, whether it pertained to the public sphere, Torah or the Jewish community. His well-documented stories about surviving the Holocaust are surely deserving of attention. But beyond his incredible life accomplishments, he exemplified the traits of being a true influencer to everyone he met.

Real influence is usually quiet; it doesn’t need to be declared. And yet our systems rarely teach this. Eighty-nine percent of business schools offer classes on how to speak and present, with very few teaching how to listen. But listening is where influence begins. And validation is where it grows.

We respond to blessings with “ amen”—a word that means “true.” Why not just stay silent? Because validation is a key element of connection, and connection is the foundation of influence. Saying “amen” is more than agreement—it’s a way of making someone else’s voice a little more real in the world. That is the essence of influence: being present, bearing witness and lending weight to someone else’s words.

Authority provides the vessel—it creates the structure within which leadership can operate. But influence is the flame. It is what warms, illuminates and sustains. As leaders—in business, in our communities and in our lives— we must cultivate both. But if we must choose which to lead with, let us begin with influence. Because when people follow you not because they have to but because they want to—that is leadership worth having.

Whether you sit at the head of the table or not, you have the power to lead—through word, action, silence and sincerity. The question is not whether you have influence. The question is: how will you use it?

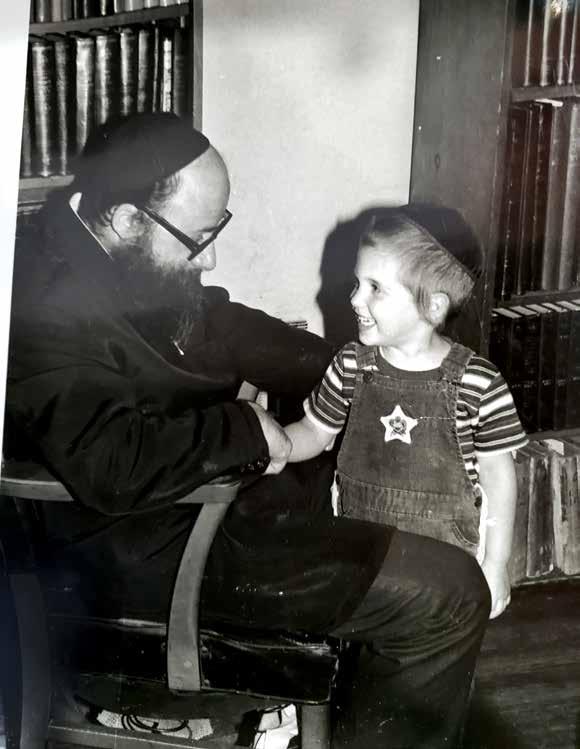

By Tova Cohen

n the quaint town of Merigold, nestled in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, Tobie Goldstein was born to parents who observed little in the way of Jewish tradition. As their only child, Tobie was cherished, she got only came during visits to her slightly more observant grandparents in Louisville,

Though Judaism was not a cornerstone of their own lives, Tobie’s parents knew she was destined for something greater. When they heard about a young rabbi teaching at the local day school in Louisville, fresh from studying at the prestigious Mir Yeshiva in Jerusalem, they urged Tobie to arrange a hasty visit to her grandparents and seek out an

That rabbi was the legendary Aryeh Kaplan, though at the time he was just a young scholar with a brilliant mind for both religion and science and an uncharted path before him. Eventually, he would become one of the preeminent Jewish thinkers and authors of our time with an extensive literary output. One day, he would inspire droves of unaffiliated Jewish teens and young adults through NCSY with his unique , fanning the flames as they grew into something much brighter. But few know of the profound role his beloved wife played in helping

“My mother, who passed away last year, was the driving force behind everything my father accomplished and who he became,” said Micha, the fifth in Rabbi and Tobie Kaplan’s line of nine children and a devoted keeper of his parents’ story, especially his mother’s. “It was my mother who, early on in the marriage, decided to make Shabbos with guests an integral part of their marriage and a focus in our home.”

“My mother is the one who really set the tone,” continued Micha, “not just for my father but for our home and the lives

With Tobie’s steadfast support, Rabbi Kaplan went on to become one of the greatest interpreters of Jewish thought into English in modern times and a key figure in the 1970s

To try and eke out a living for their growing family, the Kaplans moved frequently—from Louisville to Maryland (where Rabbi Kaplan earned an advanced physics degree) to Iowa to Tennessee to Dover, New Jersey, and then Albany,

Brooklyn, where Tobie reveled being in the heart of Jewish life and where she further anchored her young family in a structured and strong framework of religious Judaism.

But the family struggled financially. “My father wore the same sweater for twenty-five years to the point where it had visible holes,” recalled Micha. “I remember walking to school in the snow with worn-out shoes, too. But my mother had simple needs, and money wasn’t important to her. Her values

“Having an open home teeming with guests was one of my mother’s biggest priorities,” said Tobie’s daughter, Abby Rosenfeld. “Since she grew up as an only child, she was determined to always be surrounded by people. She had nine children, and she always had as many guests as possible for Shabbos.”

The Kaplan home also had a constant influx of devoted followers who never missed a shiur; they were drawn to Rabbi Kaplan’s effortless ability to convey the most complex ideas in a straightforward way.

“My father would hold classes in the house, and I remember my mother’s valiant efforts to try and keep all the kids quiet,” remembered Micah. “It couldn’t have been easy, but she always encouraged my father’s Torah pursuits.”

One regular attendee of Rabbi Kaplan’s in-house shiurim was Yitta Halberstam, journalist and author of the Small Miracles series. “I remember Tobie as a very warm and hospitable woman with the most charming Southern accent,” recalled Yitta. “She clearly gave her husband a lot of latitude to devote himself to the tzibbur (community), and she seemed perfectly comfortable and very proud that he was involved with inspiring and helping so many people.”

Abby elaborates on Micha’s earlier point about her mother’s reverence for Shabbos.

“My mother did not have a lot of material possessions, but she received a set of silver candlesticks as a gift and she treated them with extraordinary devotion, cleaning them regularly,” recounted Abby. “They were central to her Shabbos experience.”

Despite the constant flurry of children and guests, Abby remembered, her mother remained calm. “She was never frazzled or uptight while preparing for Shabbos,” said Abby. “One of my most cherished memories is making challah with her every Friday morning.” Because Abby made challah with her mother weekly, she was able to effortlessly recite the recipe by heart to her amazed teacher in the second grade who asked about the delicious bread Abby had brought to share with her class.

It was during this time living in Boro Park that Rabbi Kaplan was recruited to work for NCSY by Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, who came across his writing in a journal for Orthodox Jewish scientists and was immediately taken with Rabbi Kaplan’s extraordinary writing style.

Beyond his in-person influence, Rabbi Kaplan had a remarkable literary output, having written ten hugely

influential books for NCSY exploring Judaism’s foundational principles and central a series of booklets refuting the teachings of Christian missionaries intent on luring Jews into messianic “Judaism” at the time. He also served as editor of the OU’s the predecessor to

In fact, Rabbi Kaplan became the preeminent writer in the world of English-language Judaica. His prolific body of work includes The Handbook of Jewish Thought and translations of obscure Kabbalistic texts like the Sefer Yetzirah demonstrating intellectual rigor and a deep understanding of how to illuminate complex concepts for the masses.

A force in the popular speaker and a regular keynote at NCSY events where teens found him, despite his brilliance, both approachable and relatable.

“Throughout history, Jews have always been observant,” Rabbi Kaplan once stated in an interview. The movement is just a normalization. The Jewish people are sort of getting their act together. We’re just doing what we’re supposed to do.”

But, emphasize his children, Rabbi Kaplan would have never become so prominent in the growing such a prolific writer had Tobie not taken the reins of running their home and raising their children, serving as a behind-thescenes pillar of strength, wisdom and quiet devotion.

My mother was the driving force behind everything my father accomplished and who he became.

“When my brother Ruven was just three weeks old, my mother insisted my father go to an NCSY convention that was scheduled,” said Abby, citing an example of her mother’s selflessness. “My mother also spent many a night proofreading my father’s words. He greatly respected her input and ideas.”

Rabbi Kaplan died from a heart attack at forty-eight years old. It was 1983, and Tobie, who was not yet forty years old, was left with nine children to raise. She soon married Yeshaya Seidenfeld, who took on her children as his own in addition to the three from his previous marriage.

Although in a better financial position at this point, said her daughter, Rochel Eisig, Tobie remained a simple, low-maintenance person who had no interest in anything “gashmiyus.”

“It was my father’s entire library of sefarim that were among her most prized possessions,” said Rochel. “She let people borrow them, but it was extremely important that they be returned.”

“My mother had an encyclopedic knowledge of every sefer in the house, so much so that I once visited and came home to my wife getting a call from my mother, asking if I took a certain sefer she noticed was not in its place,” recounted Micha. “She might not have known how to speak Hebrew, but she imbibed the words anyways. During the Covid-19 pandemic, one of my nephews came to her home to learn every day, just so she could hear him learning and absorb the pages of Gemara.”

Her other most cherished treasures? Her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, each of whom was special and unique in her eyes, said one of her closest friends, Annie Weiss. “Tobie didn’t care about anything as much as her family,” said Annie. “She was always there for them, whatever they needed, through good times and bad, just an excellent and devoted mother and grandmother. It’s just beautiful to see the family she created.”

When Tobie passed away last April at age eighty-two, she left behind over 150 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, all of whom are deeply devoted and observant Jews today.

A new generation of young people are now embracing Rabbi Kaplan’s works, which NCSY reissued in 2021.

“Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s capacity to help people find a home within Yiddishkeit and in Jewish life, which was his life’s work, is undoubtedly a testament to the home he and his wife, Tobie, built together,” said Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, NCSY’s director of education, who spent two years editing the collection of Rabbi Kaplan’s writings.

As Rabbi Kaplan’s legacy continues to live on and inspire people to dive deeper into Judaism, it’s time that people recognize the woman who not only made this legacy possible but who beautifully inhabited the often unseen yet indispensable role of those who stand behind great leaders— not merely supporting their journey but shaping it in the most profound ways.

Ed. Note: Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan briefly served as editor of Jewish Life, the precursor to Jewish Action, in 1974. During his tenure, he wrote the following editor’s note, which was published amid the Watergate scandal and the Arab oil embargo. In response to the US’s support for Israel during the war with Egypt and Syria, Arab oil producers halted exports to the US. This resulted in soaring gas prices, long lines at gas stations and a major economic downturn.

If a generation ago, someone would have suggested that the economies of the United States and the great European powers might depend on a Halachic question, he would have been considered mad. Yet, this past winter, this proved to be exactly the case. If size or population were the sole criterion, Israel would be counted as one of the more insignificant nations of the world. As the birthplace of the Bible, it might have stirred some interest, but it would never be the focus of world concern. There is one factor that makes Israel the center of international politics—and that is the fact that it is surrounded by a veritable sea of oil. Since its birth, Israel has been at odds with the Arabs, who control a very large percentage of the world’s oil supply.

Of late, the Arabs have been learning how to use oil diplomacy as a weapon. As a result, any conflict in the Middle East is felt by all the great oil consuming nations, who depend on the Arabs for the bulk of their energy supply. Therefore, any movement that Israel makes vis-a-vis the Arabs has reverberations throughout the industrialized world.

During the past winter, the settlement of the Middle East stalemate, and hence the flow of Arab oil, was

greatly dependent on Golda Meir’s ability to form a viable majority government. One of the major obstacles was the Religious Block (Mafdal), who would not join the government until the question of “Who is a Jew” was cleared up in a manner conforming to Halachah. Until what was basically a Halachic question could be resolved, it seemed that the oil taps would remain shut, and that the great powers would have their thirst for oil unassuaged. Thus, in a sense, the economies of the great industrial powers—for a while at least—were dependent on a question of Halachah.

We often say, “the Torah is the blueprint of the world,” and that “the whole world depends on the Torah.” This is one time when we were actually privileged to see this in practice.

Another teaching closely related to this is that “Eretz Yisroel is the center of the world.” In ancient times, this

was literally the case, since Israel was the only land bridge between the Eurasian and African continents. If one wanted to cross over from Eurasia to Africa by land, the only way to do so was to pass through Israel. In many ways, it was Israel’s geographic position at the crossroads of civilization, that put her in contact with every major culture of the ancient world.

In modem times, this geographic position is no longer that crucial. As if in compensation, another factor has suddenly come to the fore. It is the fact that Israel’s neighbors control the bulk of the world’s oil supply, which guarantees that every great world power will once again take a strong interest in events in that area.

But the more we think about this, the more an important question comes to mind. Why is all this oil found just there? Why did Divine Providence—for this cannot be mere coincidence—place the world’s energy treasures right at Israel’s doorstep? Pondering this question is enough to convince even the skeptic that we are somehow witnessing a drama whose script was written a very long time ago.

The question becomes all the more striking when one realizes that our century—the one in which the State of Israel was re-established—is, and will remain, the one which is the most dependent on oil as a source of its energy. A century ago, coal was the main energy source, while in the century to come, it will most probably be either nuclear or solar energy. It is precisely at the moment that the drama is being played that oil is playing its most important role.

There may be some of William James’ proverbial “tough minded” individuals who will fail to see the hand of G-d in all this, but they will have to be very tough minded indeed.

Anyone who has ever seriously given any consideration to the tides of history knows of those pivotal events, often unrecorded, upon which the fates of empires and civilizations are decided. It is often a relatively minor decision on the part of an obscure individual that ultimately changes the world for centuries to come.

Egypt, leading to the drama of the Exodus and the birth of the Jewish people. All of this resulted from a relatively “unimportant” decision on the part of a lowly slave.

In the past year, the shape of national—and ultimately world—history, has been shaped largely by a decision of Frank Wills, a security guard at 2600 Virginia Avenue in Washington, D.C. If he had not noticed a piece of tape over a lock, or had neglected to report it, the country today would not be rocked by the national trauma named for the building he guarded: Watergate.

Our sages teach us that every act that an individual does ultimately has reverberations that will affect mankind as a whole. Besides this, who knows which events will be pivotal in shaping world history. Providence has allowed us to be witness to one such pivotal event—the decision of Frank Wills—and the world is trembling at its outcome.

As this is being written, the fate of the Presidency, and ultimately of the United States as a whole, is hanging in the balance. Whatever direction this ultimately takes, the government will remain scarred and disrupted for decades to come, it is a situation unprecedented in modem history, and for this very reason, no one can predict just how cataclysmic its effects will be. And as President Nixon himself has pointed out many times, we are also at a pivotal point in world history—with Europe, Russia, China and the Middle East in the balance—and therefore, the outcome of Watergate and the impeachment trial will have unprecedented effects on the world as a whole.

Much of what happens in the next few decades—and perhaps for a much longer time—will depend on the decisions of one individual—President Nixon himself. At this most fateful time in world history—and ultimately in Jewish history as well—it would be well for us to ponder the verse (Proverbs 21:1), “The king’s heart is in the hands of G-d. . . . He turns it wherever he wills.”

The prime example of this was the Egyptian slave who refused to be seduced by his master’s wife. He was falsely accused of attempted rape and, as a result, imprisoned. In prison, he came in contact with Pharoah’s butler, and thus, Joseph eventually became the prime minister of Egypt, and in this capacity, saved the greatest civilization of the ancient world from being decimated by famine. Closely intertwined with this was the emigration of Jacob and his family to

Two years ago, at the age of sixty-nine, I started having memory problems. I lived in Israel at the time and went to visit the Roman theater in Caesarea. I really enjoyed it and told one of my sons about it.

My son said, “Abba, we were just there a few weeks ago.” I had absolutely no recollection of going to Caesarea. None. Even after my son reminded me of what happened there, I couldn’t recall anything. My memory was wiped out. That’s when I knew my memory issues were not just due to aging. I realized something was very wrong and went to a neurologist.

The neurologist at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem administered a MoCA test, used to assess cognitive impairment, and an MRI of my brain. After reviewing the results, he diagnosed me with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an early stage of dementia. Since then, I’ve been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease. This is the stage where I am now, at the beginning of the journey of Alzheimer’s.

I have gone from being a fairly normal person to one whose life has changed immensely. Within a period of two months I went from rarely hearing “can I help you with that?” to hearing it far too often. I am not able to do things I used to do effortlessly, and the phrase “I need help” comes out of my mouth with increasing frequency.

I think slowly and I don’t absorb things well. If somebody speaks quickly, I can’t keep up. When I go to shul on Shabbat morning, I take a chumash and a siddur like everyone else. But I keep them right next to me and do not open them up, because following along is too difficult. I can no longer listen to the shaliach tzibbur and try to read along at the same time.

A recent sign of my brain’s deterioration is my inability to recognize people—someone might approach me and it’s obvious that we’re well-acquainted from the way he’s speaking to me, but I don’t recognize the person’s face or his name at all.

On occasion as I speak with my neurologist on Zoom, I have no idea it’s him, except for the fact that I see his name on the bottom of the screen.

I am not able to do things I used to do effortlessly, and the phrase ‘I need help’ comes out of my mouth with increasing frequency.

There are things I remember and things I don’t. I can’t distinguish between what kinds of things I will remember and what I won’t. Sometimes I remember something asked of me ten minutes earlier, but I will have no recollection of what happened yesterday. Instead of memory, there is blackness, a void. Nothing.

A very scary moment occurred when I began to talk about one of my sons, and for a few seconds, I couldn’t remember his name. When I finally did recall it, it sounded strange to me—why would I give my son a name like that?

I have four children, thank G-d—three sons and a daughter. I’ve seen enough videos of parents with dementia who don’t recognize their own children sitting right next to them. To think that I might be at the very beginning of that path is deeply frightening.

In November 2023, I moved to Denver, Colorado, to be closer to one of my sons. Currently, I live on my own, but

my son lives close by. Every morning, I enjoy walking in a nearby park or to the botanical gardens, which relaxes me and helps to clear my mind. I also participate in a few Zoom support groups for people with dementia or terminal illnesses, enabling me to connect with others facing similar challenges.

There seem to be plenty of Jewish support groups for caretakers of individuals with dementia, but not many for those living with dementia. It is unfortunate. I’m sure it is needed.

When memory starts to fail, it drags functionality along with it. When am I going to start forgetting things like taking a house key with me when I leave the house? I don’t know. While dementia often brings a gradual decline, it can also cause rapid, unexpected deterioration—and that’s what frightens me. One woman in the support group shared that her husband, who had dementia, was doing well, and then within a month, he completely deteriorated.

And yet, even while I am frightened, I can see the blessings. I can sense my mild cognitive impairment; I feel my brain working less. I’ve always been a thinking

Once I got over the shock of the diagnosis, I came to terms with what was happening to me . . .

person, but as I experience cognitive decline, I feel my heart becoming more expansive. I’ve become more of a feeling person. I’m much more emotional than I ever was. I cry often. When I go to the supermarket, I always hug the security guard. I’ve discovered that I actually like this new self.

Truthfully, people aren’t used to hearing someone talk honestly about dementia and dying. But one of my goals is to start conversations about these difficult and painful topics. At this stage of my illness, it’s early, and I still have time to do things before I reach that dreadful place.

I had to figure out how I want to spend my remaining time. I decided to document my journey with dementia. Every day, I take videos to record how I feel and post them on a website.

I’ve also started speaking at different venues to raise awareness about dementia, including synagogues, libraries and educational centers. I want to learn what guidance Torah sources can offer me as a Jew on this dementia path. At the same time, promoting dementia awareness and conversation gives me a focus and helps keep me motivated and feeling alive. I believe that not being active or having a focus exacerbates dementia in many people. In that sense, dementia is both my problem and my solution.

Once I got over the shock of the diagnosis, I came to terms with what was happening to me: I was heading toward being an immobile, basically non-functional human in what amounts to a long period of dying.

Dementia takes the person away. The person is no longer who they once were.

. . . to think that I might be at the very beginning of that path is deeply frightening.

While these thoughts of dying dominated my mind, slowly another realization appeared: I’m dying and living at the same time.

But as I see it now, living and dying are not two distinct aspects. Dementia makes dying more real and reminds me that all I have is this moment. Everyone is going to die. But since I’m in the process of dying, I’m trying to live more fully and make every moment of my present life that much richer.

By Rabbi Dr. Jason Weiner

As the population ages, researchers anticipate a sharp rise in the number of people living with dementia, with cases expected to double by the year 2060. Dementia can be extremely challenging, affecting not only individuals but also their families, communities and caregivers. It raises a range of emotional, ethical, pastoral and halachic dilemmas.

Thankfully, the Torah provides detailed and wise guidance on all areas of life, offering comfort and direction when facing the challenges associated with dementia. While there are many complex issues with intricate details, this article aims to present a basic overview of some of the key areas and the rabbinic guidance that are essential to consider.

One of the most fundamental issues to address is the obligation to perform mitzvot. The ability to fulfill mitzvot is a profound opportunity to connect with Hashem and maximize one’s spiritual potential. However, when illness progresses, some mitzvot may become an overwhelming burden, confusing or very difficult to perform, rather than a source of enrichment for the individual.

Halachic authorities suggest that in the early stages of dementia, a person remains fully obligated in mitzvot However, as dementia advances, if an individual becomes completely detached from reality, they become patur (exempt). The precise determination of when they become exempt depends on their specific condition. In general, if

the individual seems aware of their surroundings and is able to understand what they are doing, they likely remain obligated in mitzvot, but if not, they become patur. This can fluctuate from time to time depending on their mental state at any given moment. They may even remain obligated in some mitzvot, such as those that they understand, while being exempt from others, such as those that they can no longer comprehend. One should consult with a rabbi to help make this determination on a case-by-case basis.

There may also be considerations related to challenges in maintaining a clean body, inability to physically perform mitzvot, or behavior that distracts others or causes embarrassment.

This exemption from mitzvot should never be seen as a punishment but rather as a compassionate recognition that they should not feel obligated to place themselves in compromising situations.

Once a person is no longer obligated in mitzvot, he should never be forced or pressured to perform them. However, if he chooses to do so, he may perform mitzvot as an aino metzuvah ve’oseh (one who fulfills a commandment despite not being required to do so).

In fact, participating in public mitzvot—such as communal prayer or a Pesach Seder—can be especially beneficial to one suffering from dementia, as studies suggest that social engagement may slow down or reduce some of the effects of dementia. This helps prevent isolation and allows one to maintain his daily routine, which are both important factors that rabbinic authorities take into account.

Rabbi Dr. Jason Weiner, BCC, serves as senior rabbi of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and rabbi of Knesset Israel Congregation of Beverlywood. He also serves as senior consultant to Ematai, which educates Jewish individuals and families about end-of-life issues.

Although individuals with advanced dementia may no longer be obligated to perform all positive mitzvot, it is still ideal that they avoid transgressing prohibitions, such as eating non-kosher food. One may gently remind the individual of these prohibitions, if necessary. This presents a particular challenge for caregivers, who must balance sensitivity and kindness with ensuring that the individual maintains their values, when possible.

When it comes to taking care of individuals suffering from advanced dementia, just as halachah provides detailed exemptions from obligations—such as allowing leniencies in Shabbat observance based on the severity of an illness—the same principles that apply to physical illness also extend to cognitive impairment. An individual suffering from advanced dementia may be considered in the category of a dangerously ill patient, for whom even Torah prohibitions can be overridden when absolutely necessary to take care of them. One should consult with their rabbi to help determine if and when these leniencies should be applied.

During the early stages of dementia, if a person wants to ensure that their care aligns with their values, goals and preferences, it is highly advisable to:

• Appoint a surrogate decision maker

• Fill out an advance healthcare directive and an ethical will

• Have clear conversations with family members to ensure that everyone is aware of their wishes

These steps help prevent confusion later on, ensuring that one’s values continue to guide their care, even when they can no longer fully express them on their own.

A particularly difficult and common dilemma is the obligation of kibbud av va’eim (honoring one’s parents), especially when caring for a parent with advanced dementia.

As dementia progresses, the needs of the individual can become burdensome and overwhelming for their family. Does honoring one’s parents mean sacrificing everything in order to care for them personally?

The Rambam (Hilchot Mamrim 6:10) addresses this issue, ruling that if caring for a parent becomes too difficult, it is appropriate to hire someone to assist. This ruling is especially relevant today, as specialized facilities and professional caregivers can often provide the ideal care for individuals with dementia. Placing a parent in an appropriate facility—when needed—should not be seen as a failure but rather as a responsible and compassionate decision. There are also certain actions that may need to be taken when caring for individuals with dementia, such as restraints or other necessary interventions. Halachah teaches that, when possible, it is preferable for these actions to be carried out by someone other than the person’s children.

Using hired caregivers may often be in everyone’s best interest, by providing proper medical care, mitigating loneliness and preventing harm to shalom bayit

Another common challenge is when an individual with dementia insists on doing things that pose a danger to themselves or others.

For example:

• Driving a car despite cognitive decline

• Living alone when it is no longer safe

While these situations can be uncomfortable to address, it is often in everyone’s best interest to take necessary steps

to mitigate these risks, even if it goes against the individual’s stated desires.

Similarly, individuals with advanced dementia may forget past tragedies, such as the death of a loved one, and repeatedly ask for them. Reminding them of such losses can cause them repeated grief and trauma. Although truthfulness is a Torah value, there are cases where Jewish law permits deviating from the truth when it is in the best interest of the individual—especially to prevent unnecessary suffering.

Compounding the personal difficulty of experiencing diminishing cognitive faculties, people suffering from dementia may also encounter disrespect that others inadvertently display towards them. Our rabbis were aware of this and cautioned us to “be careful to continue to respect an elder who has forgotten their Torah knowledge due to circumstances beyond their control, as it says: the tablets and the broken tablets were placed in the Ark of the Covenant.” This statement refers to compassion that must be shown to one who is experiencing dementia, and in fact it is stated in Menachot 99a in the name of Rav Yosef. What is fascinating is that we know from Eruvin 10a that Rav Yosef himself suffered from dementia and his colleagues would gently remind him of his great teachings in order to cheer him up. Sometimes, those suffering from advanced dementia may seem to be only a shell of their former selves. The rabbis remind us, however, that they are still holy. They are still tzelem Elokim (made in the image of G-d) and deserve to be treated with the utmost respect and dignity.

Caring for individuals with dementia presents profound halachic, ethical, medical and emotional challenges. Each case requires thoughtful navigation, balancing compassion with halachic principles on a case-by-case basis. The Torah provides guidance and wisdom in these areas, helping us make sensitive and informed decisions in these very challenging situations.

By Rabbi Daniel Rose

Here is a fictional version of an email I recently received.

Dear Rabbi,

I need you to teach me how to pray.

My father has had early-onset dementia for some time. When it began, I knew exactly what to daven for. I was davening for it to be reversed, or at least for it not to deteriorate. I was davening that he would not have to suffer the loss of his memory, let alone the loss of his mind. I was davening that it wouldn’t happen the way the doctors said it would.

But now it has happened. It is clear to all of us that his cognitive function is only getting worse, his need for aides and his inability to care for himself only getting more acute. He is not going to get better.

We are not allowed to pray for miracles. So what is left for me to pray for now?

I write back to this woman about davening for Hashem’s compassion. I tell her that everyone’s experience is different, that the disease can develop more quickly or more slowly. I tell her to daven for all that he is likely to encounter along the way: that his aides should be kind, that his overall health should remain strong, that the ancillary conditions that can accompany this condition should not be too severe. It is all true, and all eminently practical.

But most of all, what I want to tell her is that life does not end with a diagnosis of dementia.

Life changes, often drastically. Dreams and expectations can be shoved to the side. Basic needs to which we had never given much thought can become incredibly time-consuming and deeply emotionally draining. We will have to call on skills that we never called on, and never wanted to call on, before. But there is still life. There is still connection. There is still family and relationship. And there is still tefillah and hope—not hope for a cure, but hope for perspective, for compassion, for appreciation, for joy.

When someone receives a diagnosis like early-stage dementia, the shock can easily give way to a feeling of helplessness. The knowledge that what is coming is beyond our control to

We obsess over the past and fret about the future. We regret what might have been, and we pour our energy into what might be. What we see least easily is today—the growth we can achieve, the choices we can make, the people we can touch and the people who can touch us.

prevent flies in the face of everything we thought we knew about ourselves, our skill and capabilities and independent nature. And spiritually, there can be a similar kind of helplessness. What does Hashem want from me now? Facing the knowledge that my ability is going to be so limited, what does He expect me to do?

A great deal.