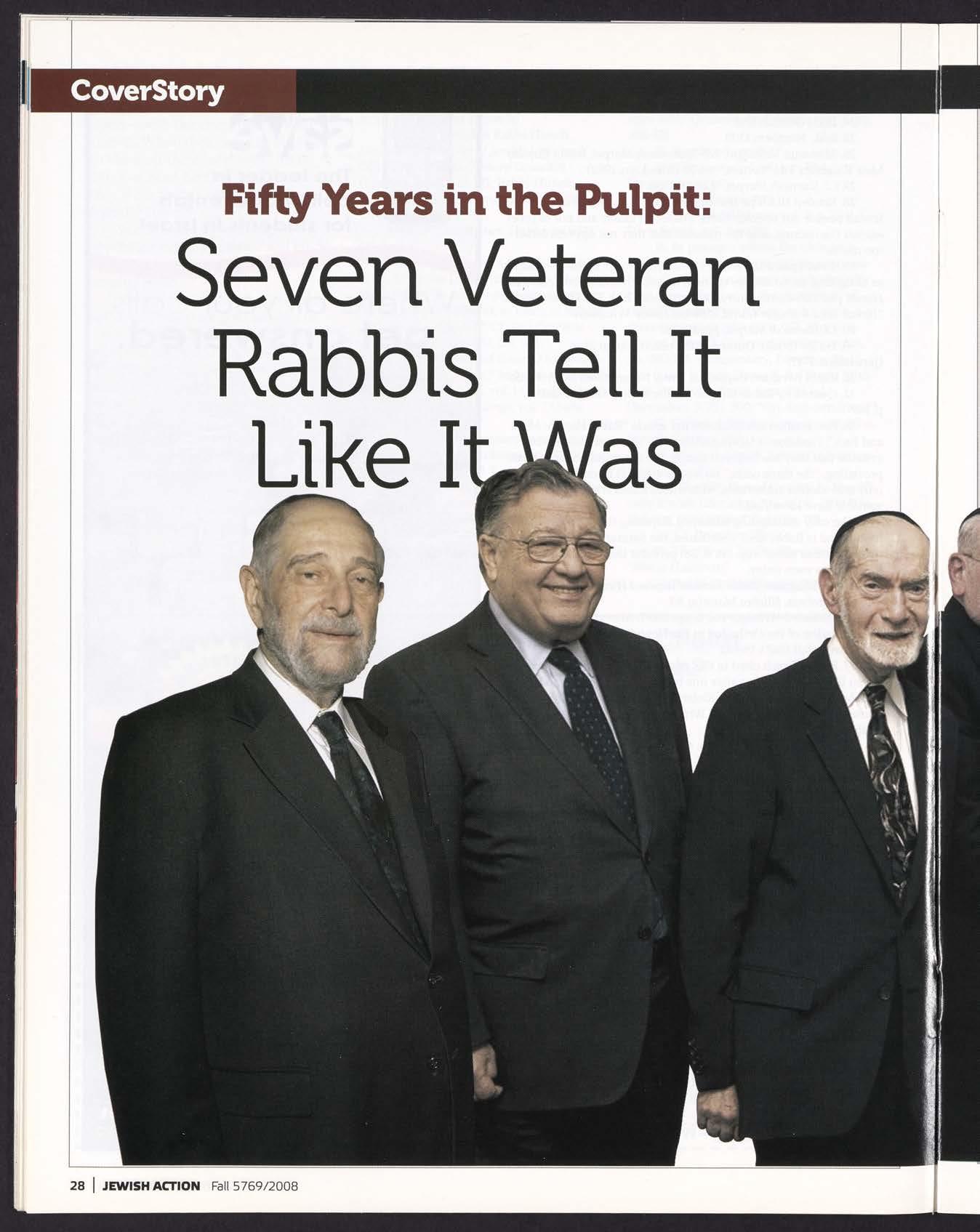

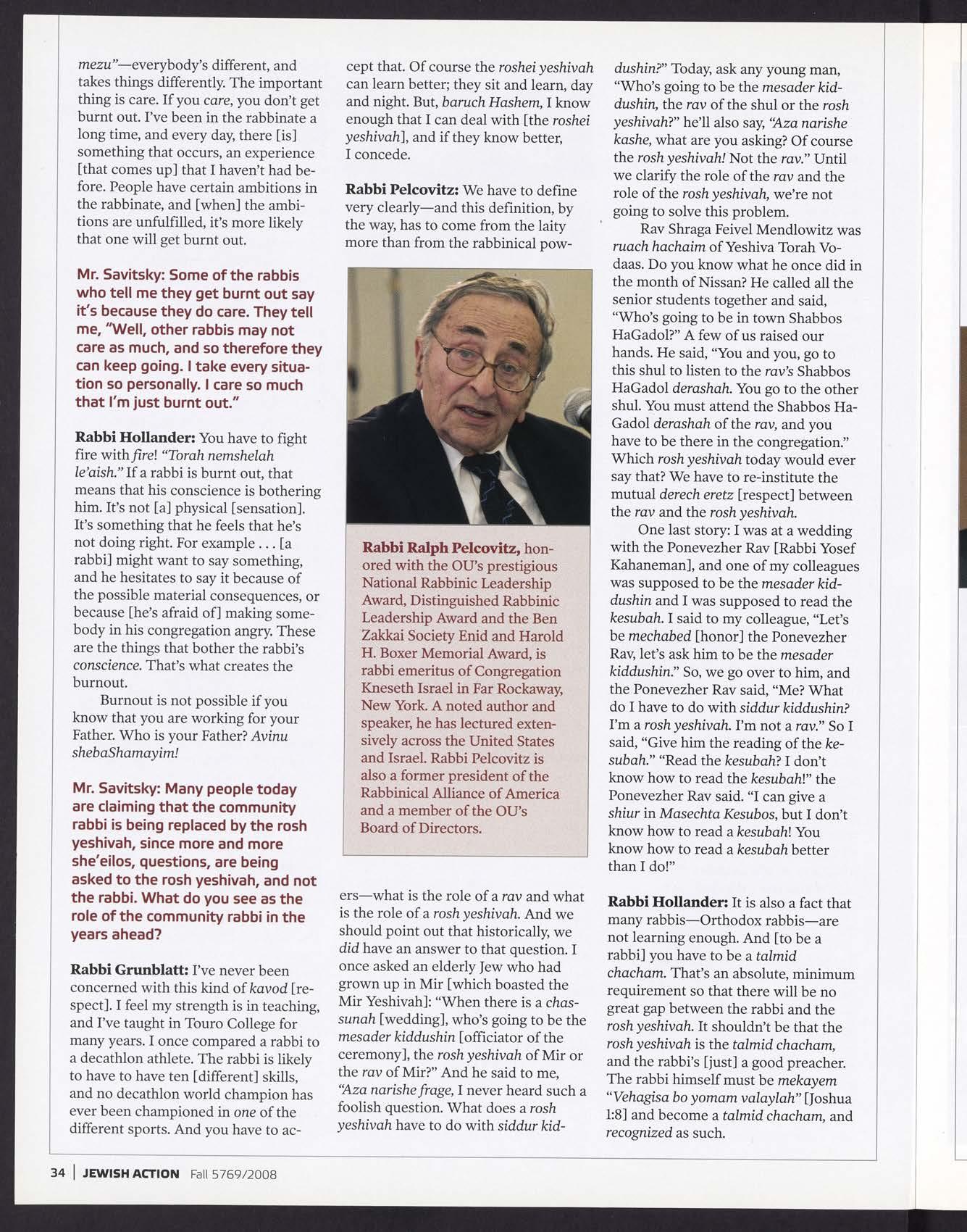

Remember This Article?

A special edition flipbook

Dear Reader,

What were American Jews thinking in the eighties? The nineties? 2000? 2010? 2020?

To see the concerns of American Orthodox Jewry over the last forty years, open an old issue of Jewish Action.

Since our debut in 1985, we ’ ve covered it all the fading Cold War, the war on terror, AIDS to COVID-19, Dial-a-Daf to daf yomi on your phone. We chronicled the Soviet Jewry movement, Ethiopian aliyah, 9/11, the Disengagement, and most recently, the horrors of October 7. We’ve tackled the challenges of a digital age that keeps changing how we learn, connect, and live as Jews.

Some topics never fade: anti-Semitism, work–family balance, kiruv, aliyah, addiction, Jewish education, technology, Torah and science. They’ve been with us since the beginning.

Launched by Joel Schreiber and Rabbi Matis Greenblatt, Jewish Action quickly became known for thoughtful, honest coverage of the issues that matter most. We’ve featured leading voices and prof iled the people who shaped our time.

To mark forty years, we ’ ve chosen some of our most memorable pieces the debates, dilemmas, and moments that have def ined us. What they tell us about Orthodox Jewish life is up to you.

-The JA Team

Instructions:

Take your time to go through this flip book and relive some of JewishActions most powerful articles.

Which do you remember? Do you remember any strong emotions you felt towards that piece? How did it make you feel?

We’d love to hear your thoughts and comments on one (or all!) of the articles provided to you.

Please email us at ja@ou.org with “Flip Book Commentary” as the subject line.

You may request to remain anonymous if you wish.

Happy reading!

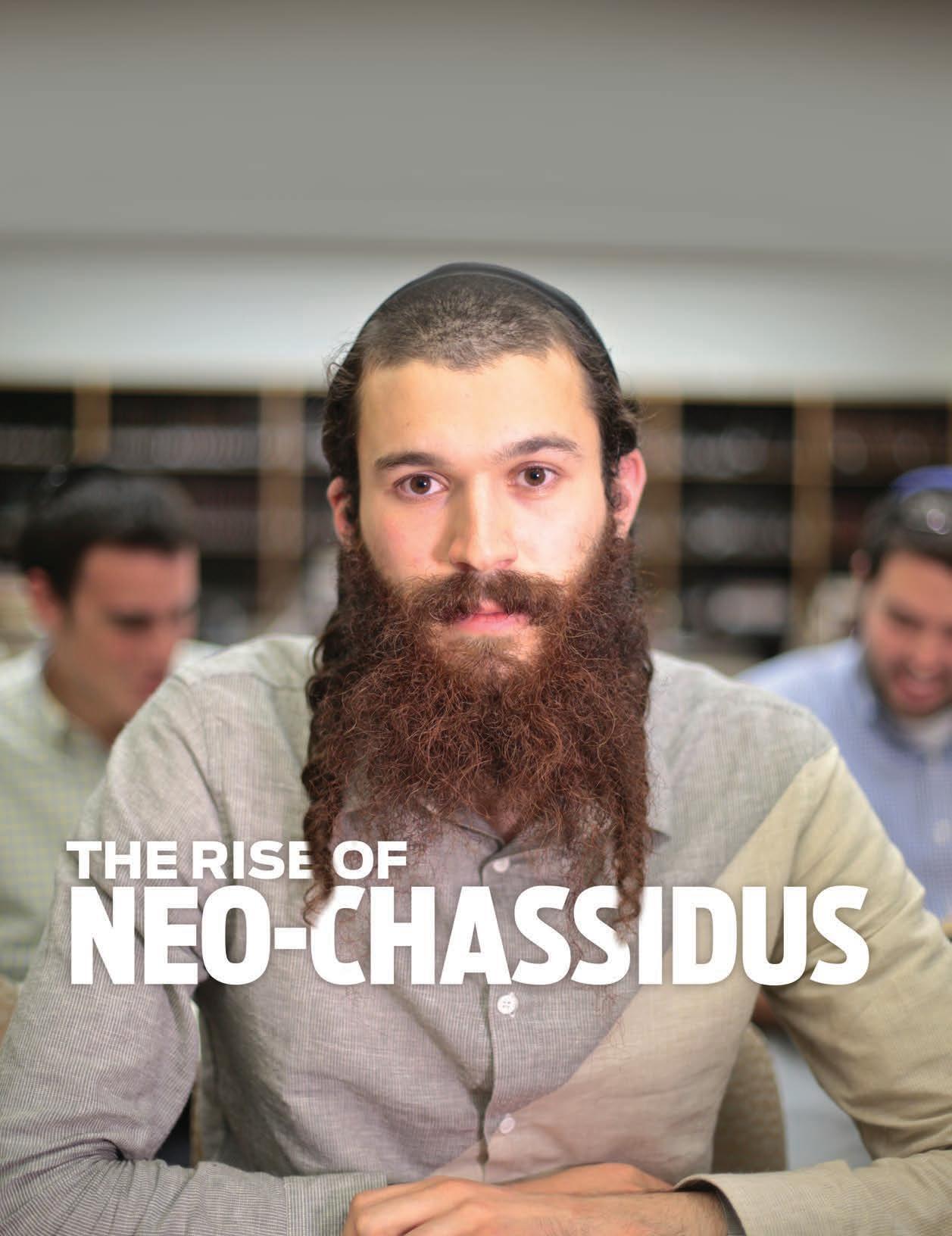

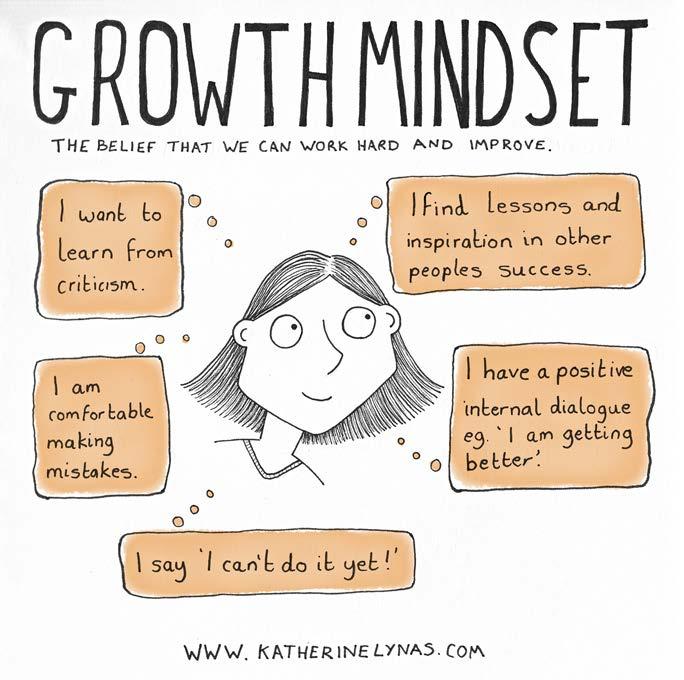

Neo-Chassidus Brings the Inner Light of Torah to Modern Orthodoxy

BY BARBARA BENSOUSSAN

Photos by Josh Weinberg, unless indicated otherwise.

Photo: Dov Lenchevsky

A prince once lay dying, and seeing that the doctors could do no more for him, the frantic king sent for a tzaddik known to be a master of medicine. The tzaddik told the king, “There is one cure that might help him. There is a rare precious gem that, if crushed and mixed into a potion, might cure your son. The gem can be found on a faraway island, but there is also one in the center of your crown.”

“What good does my kingship serve me if my only child dies?” cried the king. “Take the gem from my crown and cure him!”

Barbara Bensoussan, M.A., is a contributing editor of Mishpacha magazine and writes for Jewish Action and other media outlets. She is the author of the young adult novel A New Song (New York, 2006) and the cooking memoir The WellSpiced Life (Lakewood, NJ, 2014), has worked as a university instructor and social worker, and currently writes for Jewish newspapers and magazines.

This mashal (parable), which comes from the Ba’al HaTanya, the first Lubavitch Rebbe, Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, was offered in response to those who opposed teaching the peninim of Torah in the open. The dying prince represents Am Yisrael, languishing from lack of inspiration; the gem represents the inner light of Torah that can revive him.

“From the middle of the eighteenth century, gedolim like the Ramchal [Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzatto] and the Ba’al Shem Tov began bringing forth the deeper secrets of the Torah,” says Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, mashpia at Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) and the rav of Congregation Aish Kodesh in Woodmere, New York. “Halachah constitutes the physical life of the Jew, but the soul of the Torah is the potion we need to infuse it with life. Hashem saw that the Jewish people were suffocating, so He sent the Besht [the Ba’al Shem Tov] to revive them and give them a taste of the light of Mashiach.”

Despite the fact that the Orthodox world brims with minyan factories, glatt kosher vacation packages, yeshivot and kollelim and a thriving print media, Rabbi Weinberger is concerned. One thing is missing, he says: “the soul.” As he wrote in an essay that appeared in the online journal Klal Perspectives in 2012, “Our communities—spanning the en-

tire spectrum of Orthodoxy—are swarming with Jews of all ages and backgrounds who have little, if any, connection to Hakadosh Baruch Hu.” Many of the off-the-derech youth, he says, are not running away from authentic Yiddishkeit; they simply “never met it.”

“There are many out there who may have been shown or taught a version of Yiddishkeit that is dry, that is cold,” agrees Josh Weinberg, a YU musmach who considers himself a neo-Chassid, and is one of many who look to Rabbi Weinberger for inspiration. “They may practice Judaism in their communities [due to societal pressure], but inside, there’s a lot of apathy and [it’s done by] rote. Chances are they were never exposed to this deeper and joyous side of religious observance,” says Josh, who lives in Riverdale, New York, and works as a photographer and videographer for NCSY.

Rabbi Weinberger’s outspoken encouragement of a deeper engagement with what he calls “the inner light of Torah” has caused others to describe him as the captain of a growing trend among the Modern Orthodox to reconnect with the spiritual vision of the Ba’al Shem Tov and his disciples and others who delved into this dimension of Torah. Some of the more popular Chassidic texts that appeal to this group include Rabbi Elimelech of Lizhensk’s Noam Elim-

Editor’s Note: This magazine’s policy has always been to use Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Because in the neo-Chassidic movement Chassidus is referred to as Chassidus, not Chassidut, we felt it was important to spell the word as the movement does. Additionally, please note that many of those interviewed for this article use Ashkenazic pronunciation.

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger’s appointment as mashpia at YU indicates just how deeply the neo-Chassidus movement has impacted the Modern Orthodox world. Photo courtesy of Yeshiva University

elech, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev’s Kedushat Levi, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov’s Likutei Moharan, the seforim of Chabad Chassidus, including the Tanya, the seforim of Rav Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin and those of the rebbes of Ger—the Chiddushei HaRim (Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Rothenberg Alter), the Sefat Emet (Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter) and the Imrei Emet (Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Alter), as well as the writings of Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner and Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaCohen Kook.

Some adherents take on hitbodedut (meditation), attend tisches and farbrengen (Torah gatherings), immerse in the mikvah, engage in Carlebach-style davening and visit tzaddikim or kivrei tzaddikim (such as Rabbi Nachman of Breslov’s kever in Uman).

The Influence Spreads

Rabbi Weinberger’s appointment as mashpia at YU last year indicates just how deeply the neo-Chassidus movement has impacted the Modern Orthodox world. “I myself went to YU forty years ago,” Rabbi Weinberger says. “Today, it’s a different world. There’s still the same strong learning, but so many of the boys are thirsting for the life of inner Torah; in Eretz Yisrael, there’s a real sense of excitement in the hesder yeshivos, where the influence of Rav Kook is still felt.”

Rabbi Judah Mischel, a former rebbe at Yeshivat Reishit Yerushalayim and a popular teacher of Chassidus in Israel, maintains that the rediscovery of Chassidic teachings in the Modern Orthodox world is “changing the face of the community.” YU traditionally embraced a more intellectual or Litvish approach to Torah study. Now YU offers weekly shiurim in Chassidic thought, monthly farbrengen with Rabbi Weinberger as well as a Rosh Chodesh musical minyan, all of which represent a dramatic shift for YU. Rebbeim at YU noted the popularity of neo-Chassidus in Eretz Yisrael, where 85 to 90 percent of YU students study before attending the university. “The administration said that if this moves many of our students, let’s give it a try,” stated Rabbi Yosef Blau, senior mashgiach ruchani at YU, in a February 2013 article in Commentator, the YU student newspaper.

Rabbi Mischel, a resident of Ramat Beit Shemesh, Israel, who is a current student of Chassidic master Rabbi Avraham Tzvi Kluger, defines neo-Chassidus as “people trying to live Yiddishkeit from the inside out, to live more deeply and fully . . . . People today are refusing to be put into boxes. God is One, and His truth can be refracted in many different ways.”

Rabbi Weinberger may be the movement’s senior spokesman, but most of the followers are young. “The majority of the people involved with neo-Chassidus are under thirty,” says Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, an avid follower of the movement who lives in Teaneck, New Jersey. Rabbi Bashevkin, who currently serves as the director of education for NCSY, earned semichah from YU where he completed a master’s degree in Polish Hassidut focusing on the thought of Rabbi Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin.

Memphis Memphis

Noting the trend, some Modern Orthodox high schools have begun offering courses on Chassidus. Torah Academy of Bergen County in New Jersey offers an elective called “Introduction to Chassidut.” This past year, the Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School in Livingston, New Jersey, held a school-wide day-long program on Chassidus which stimulated so much interest in the subject the school decided to offer an ongoing course on Chassidic thought. The popular elective, open to eleventh and twelfth graders and called “Chassidic Thought on Ahavat Hashem,”focuses on studying works from some of the greatest Chassidic personalities, including the Ba’al Shem Tov, the Ba’al HaTanya, Sefat Emet, Kedushat HaLevi, the Piaseczna Rebbe (Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira) and others.

While Rabbi Eliezer Rubin, Rae Kushner Yeshiva High School head of school, does not see a mass movement of high schoolers becoming neo-Chassids, he does see a marked interest in Chassidic thought. He attributes this to the impact of the digital revolution. “Everything is individualized nowadays,” he says. “Even religion is individualized. We select our own music, our own games, our own TV shows through Netflix.” Now, he says, you can select your own style of Judaism.

Nor is this surge of interest in Chassidus limited to Modern Orthodox Jews in the New York tri-state area. Rabbi Shlomo Einhorn, dean of Yeshiva Yavneh in Los Angeles, says that every few months, a few shuls in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood, a solidly Modern Orthodox part of town, coordinate a tisch. Similarly, classes on Chassidic thought are sprouting all over, such as a class on the Tanya and Netivot Shalom, the work of the Slonimer Rebbe, offered in the Boca Raton Synagogue.

An All-Encompassing Approach

Joey Rosenfeld, a twenty-six-year-old enthusiast who used to give shiurim in Chassidus in New York (he recently moved to St. Louis), says that many of his friends found spiritual support in Chassidus when they returned from a year or two of learning in Israel and transitioned back into American life. “They come back after a year of inspiration

and increased piety, which was easy to maintain in the bubble of the beit midrash, and find themselves among an affluent, modern lifestyle,” he says. “It creates cognitive dissonance: Either you go back to your old lifestyle, or you find new ways to cling to authentic Judaism. Chassidus offers an all-encompassing approach to Jewish life. It includes not only life in the beit midrash, but prayer, dealing with struggles and failures and connecting to God even through mundane activities.”

Rosenfeld adds that Chassidus also offers an alternative to the Litvish yeshivah tradition which emphasizes intense learning above all else. “Chassidus encourages people to connect to God in their own unique ways, in ways that make them feel good,” he says. “It’s less elitist. People don’t have to feel guilty about learning bekiut instead of b’iyun, or Tanach instead of Talmud or for picking up a sefer [with an English translation]. ”

Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg, who teaches and serves as mashgiach ruchani at YU’s Irving I. Stone Beit Midrash program (SBMP), agrees that the Chassidic approach promotes a balance sometimes missing in the yeshivah world. “For most people, it’s not realistic to hear that their only acceptable outlet is sitting in a beitmidrash,” he says. “It’s liberating for them to find other means of connecting to Hashem that are authentic and not bedieved. The Litvish and the mussar approaches emphasize yirah and [the] Shulchan Aruch, but that can be [damaging]. The Chassidic approach is softer, more positive. It emphasizes simchah—simchah shel mitzvos, simchah shel chaim. It’s a different vision of what it means to be an ideal Jew.”

Rabbi Weinberg came to Chassidus through his brother Josh, mentioned earlier in this article, who studied in Israel about a decade ago under Rabbi Mischel. Through Rabbi Mischel, Josh and another brother became exposed to Chassidic ideas; upon their return, they passed along their enthusiasm to their oldest brother, Moshe Tzvi. “Chassidus has an energy I haven’t seen elsewhere,” Rabbi Weinberg says. “I had no connection to Chassidism as a child in Philadelphia beyond an image of peyos and shtreimels; I had no idea it could be a language of spirituality, of communication with Hashem.”

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger says that even those raised in Chassidic homes are coming to his shiurim, seeking to reconnect. “For some of them, Chassidus became a way of life, not a fire. Now they’re seeking a new spirit of Chassidism, a rekindling of the fire of the Besht. There are quite a few old-school Chassidim who regularly attend my shiurim.”

Roots of a Revival

Some credit Reb Shlomo Carlebach as being the first to bring Chassidic-style song and tefillah to the Modern Orthodox world; the first Carlebach minyanim introduced a certain Chassidic spirit and warmth into tefillah. “Many shuls had been having trouble getting a minyan when Carlebach started out,” says Dr. Chaim Waxman, professor emeritus of sociology and Jewish studies at Rutgers University. “His style of davening attracted a lot of people.” Today, neo-Chassidic musicians such as brothers Eitan and Shlomo Katz follow in the Carlebach tradition by offering audiences folksy, often inspirational music and teachings. At YU’s neo-Chassidic Rosh Chodesh minyan, some of the participants bring instruments.

Providing sociological context to the neo-Chassidic trend, Dr. Waxman notes that many hesder/Dati Leumiyeshivot in Eretz Yisrael emphasize Chassidic thought, particularly the teachings of Rav Kook, and American students who study there bring home these ideas. American culture, he says, is particularly receptive to them. “American Jews are brought up around the particularly American idea that religion is something that should be meaningful,” he says. “Spiritual seeking is something that has always been a part of the broader American culture. In the past couple of decades, there has been an increased emphasis on the question, ‘What does religion do for me?’”

Dr. Waxman says that Lubavitch Chassidism, which he claims is the fastest-growing movement within American Judaism, resonates particularly well among the Modern Orthodox because it has traditionally encouraged participation in the wider world, the pursuit of higher education, and reaching out to less-affiliated Jews. “Today, you have well-regarded intellectuals like Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz and Rabbi Joseph Telushkin producing biographies of the Lubavitcher Rebbe,” he points out. In general, the Modern Orthodox as well as unaffiliated Jews are more likely to connect with more outward-focused Chassidic groups such as Lubavitch and Breslov than with more insular groups.

Some young people are aware that their own family trees include Chassidic branches, which generates curiosity about Chassidism that leads to involvement. Those who were inspired by Chassidus in Israel may take on external signs like peyot or a gartel when they return home as a means of distinguishing themselves, as a way of marking the spiritual transformation they felt while in Israel. “The people involved [in neo-Chassidus] are a little unconventional, in the sense that they grew up in the Modern Orthodox world, then come home with peyos and a beard,” says Josh. “The YU world of Rav Soloveitchik and Brisk is very intellectual, and by comparison we may seem hippie-ish; some parents see it as a rejection. But most aren’t rejecting anything.

They’re seekers who are looking for a deeper connection.”

“People are moved by sports and movies,” explains Rabbi Einhorn. “They want to be moved emotionally by religion too.”

Thus, it should come as no surprise that women also find neo-Chassidus appealing. One indication of this is the rise in women-only trips to Uman, led by female teachers such as Rebbetzin Yehudis Golshevsky of Jerusalem. These trips do not take place during the intense High Holiday season, when thousands of men flock to Uman; instead, the women tend to go on Rosh Chodesh, seen as a women’s holiday, and especially on Rosh Chodesh Kislev, which has significance for women since the ancient heroine Yehudis helped bring about the Chanukah miracle.

Rebbetzin Golshevsky, herself a product of a Modern Orthodox home who considers herself Breslov today, has been teaching Chassidic Torah for nearly twenty years in Israel. Her popular classes attract women from across the religious spectrum. Why do they come? “Oxygen,” she says. “The Jewish world is in serious need of oxygen . . . . There is nothing sadder to me than Jews going through the motions of observance without feeling the passion. Chassidus instills in a lot of people that passion, that fire, for serving God. It’s not that you can’t have the fire without Chassidus, but it sure is harder.”

An Unofficial Movement

When did this trend first take root? Some date it back about five years ago, when a small group of YU students who recently returned from studying in yeshivot in Israel decided to set up a chaburah to study Chassidic texts during winter break in the basement of a home in Teaneck. Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg was among those who delivered the shiurim. “That group snowballed into a lot of what’s happening now,” he says. “It became known as The Stollel, which now runs a Twitter feed and maintains continuous learning. Today the minyan [in Teaneck], which meets for chagim and special occasions, attracts hundreds of people—we had to move it from a home to a shul.”

“It developed into a sort of underground movement,” says Josh. “Some have even taken to calling its followers ‘neo-Chassidic Warriors.’”

But the neo-Chassids from non-Chassidic backgrounds aren’t for the most part moving to Williamsburg or taking on the full Chassidic garb or minhagim. “Neo-Chassidus is turning back the clock 250 years on Chassidism,” Rabbi Bashevkin says. “That was before Chassidic minhagim even existed!” Some neo-Chassids dabble in Chassidic thought and practices, while others engage deeply with them.

“Neo-Chassidus is more about a consciousness, not a style of dress,” says Yitzchak, who maintains a blog for the movement and prefers to be identified by his first name only. “The social [aspect] is also an important part of the avodas Hashem—the cohesion of people sitting around a table together at a farbrengen, traveling together to Uman.”

According to Rabbi Bashevkin, there’s also a lighthearted side in the movement determined to put the gesh-

mack [enthusiasm] back into Jewish practice. “There’s a sweetness and a rich sense of humor in the movement, a component which goes back to Rabbi Nachman of Breslov,” he says. “You have The Stollel’s Twitter feed, and another called #UofPurim— Purim happens to be a holiday that resonates well with this movement.”

Josh notes that this exuberance has a broad appeal. “A Jew is looking to be connected and the soul needs to be filled with something,” he says. “In a world where there’s so much excitement in nonkosher venues, the movement gives one the ability to fill the soul with holy things, giving young people an exciting way to connect to Judaism.”

Proceed with Caution

Not everyone is wholly enamored of neo-Chassidus. Rabbi Blau admits that the singing and dancing aspect of neo-Chassidus serves a need for people looking for ways to connect to Judaism in an immediate and emotional way, and allows young men not cut out for intensive study to find alternative outlets. But he worries that all this feel-good activity may be too easy a substitute for rigorous Torah study, especially among a generation with a low tolerance for delayed gratification. “I represent, to a degree, a more rationalist tradition,” he says. “When I was in yeshivah, the ‘best’ students were those who were either the smartest or most willing to persist for long hours in the beit midrash. How do you judge a ‘top’ student of neo-Chassidus? It’s impossible to know at this point if this trend will produce talmidei chachamim.”

On Chassidus

Excerpted from Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Faces and Facets (Brooklyn, 1993), 141.

n the darkest days of Jewish history, Chassidism brought a new hope, a new happiness to millions of people. It brought Judaism to life again, making it meaningful to the masses. The radiance that illuminated two centuries of Jewry may yet have another great purpose to serve.

I was once at a conference where it was discussed what kind of Judaism we will have in America 100 years from now. Some people said the trend would be toward Reform. Others said it would be toward the middle, conservative movements. The pessimists said that there would be no problem, given the current rise in intermarriage, for in 100 years, there would be no Judaism at all in America. But one person suggested that 100 years from now, Chassidic Judaism would dominate the American Jewish scene.

I would agree. The Chassidic spirit, the Chassidic philosophy, is certainly the up-and-coming thing. Perhaps this is our answer, the missing ingredient which will provide our coming generation with a new kind of Judaism, a turned-on Judaism . . . Maybe we have to get involved in this love affair of the Chassidim, this love affair with God.

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger has his own concerns; he cautions against leaping into the fire of inner Torah without taking certain precautions. “If people jump in too quickly, without proper teachers, it can lead to imbalance and confusion,” he says.

“There are many broken people out there looking for a fix. This is a less expensive

high than drugs, but if it’s not grounded in halachah and connected to a living master, it won’t succeed.” Without guidance, the mix of youthful high energy and Chassidic practice can be volatile.

“Young people are still finding themselves,” says Rabbi Moshe Tzvi Weinberg. “If there’s nothing grounding [Chassidic practice], it can degenerate into trendy, even silly New Age-style practices.” Activities such as going to Uman or meditation shouldn’t replace traditional learning, but rather add a deeper dimension to it. Rabbi Weinberg illustrates this idea with an image taken from a Chassidic sefer, which describes a father dancing at a wedding with his young son on his shoulders. The fact that the father has

will be an explosion of meaning in the Jewish world. “Rav Kook, who came from one Chabad and one Litvish parent, wrote that at the end of days there will be a conversation between the followers of the Vilna Gaon and the followers of the Ba’al Shem Tov,” Rosenfeld says. “He said that the students of the Besht will herald the coming of Mashiach.”

Rabbi Mischel likewise tells a story that the Besht interacted with Mashiach in the upper chambers of Shamayim (Heaven), and was told that Mashiach will come when the wellsprings of inner Torah spread to the outside. “Rav Kook wrote that ours would be a ‘wondrous generation,’ in which many things will begin happening all at once,” he says. “Ours is a postmodern reality in which there are many options, and many spiritual options.”

Until Mashiach comes, we can look to this generation’s revival of Chassidus as a way to comfort and warm the Jewish soul in the trying times before his arrival. Rabbi Weinberger relates that a Mitnaged once challenged the Chassidic master, the Tzemach Tzedek (Rabbi Menachem

an obligation to be careful about his precious cargo doesn’t detract at all from the joy of his dance.

Rosenfeld similarly believes that it’s easy for some to pervert Chassidic concepts of joy, prayer and tikkun olam to the detriment of halachic observance. “As much as it’s a problem to be a vessel with no light, you can’t be light with no vessel,” he cautions. Another adherent, Yitzchak, adds that it’s simplistic to view Chassidic practice as all about prayer and kabbalah, and not about serious learning.

“Parts of the Zohar are very dry and technical!” he points out. “Tanya is very complicated—it requires tremendous zitzfleisch [patience].While on the one hand you have these Chassidic stories about people sitting and reciting the Aleph Bet to show that it’s possible to connect to Hashem on a simple level, the intellectual tradition of Chassidus is very deep and sophisticated.” He adds that it can be just as challenging to be matzliach (successful) in prayer as it is to succeed in learning.

Many of the movement’s adherents mention that Chassidic writings predict that in the days before Mashiach there

Mendel Schneersohn, the third Lubavitcher Rebbe): “What’s the difference between you and me? We study the same Torah and observe the same mitzvos.”

“It’s like two chicken soups,” the Tzemach Tzedek replied. “The ingredients are exactly the same. But one is cold— and one is hot.”

Jews dancing at Medzhibozh, Ukraine, on erev Rosh Hashanah.

Andrei Riskin

Chassidic

Photo:

WHEN LEADERS

HEALING FROM RABBINIC SCANDAL

By Yitzchak Breitowitz

In Bernard Malamud’s novel e Natural, an extremely talented ball player, Roy Hobbs, is discovered to have taken a bribe to throw a baseball game. He is barred from baseball for life and all his records are expunged. In a poignant final scene, a young boy turns to Roy with pleading eyes and says, “Say it ain’t so.” But Roy cannot. He simply weeps.

In many ways, this novel is a metaphor for the loss of innocence, for the sadness of discovering that those we thought were paragons of virtue and greatness are flawed, for the sense of betrayal as we are cast adrift by those in whom we put our trust and faith. In many ways, this metaphor aptly describes a crisis that is spreading within the Torah community.

We live in the era of the fallen hero—indeed the tragic hero who is destroyed by the fatal flaw that lies within. In all walks of life, people whom we admired have disappointed us with their failures and weaknesses. We have become disillusioned and cynical. Unfortunately, even within the Torah camp, leaders in whom we placed our trust have betrayed us. And while the overwhelming majority of rabbis, teachers and spiritual mentors perform their tasks with integrity and commitment— and we should never make the mistake of condemning the many because of the sins of the few—many of us have lost faith in the very people who are supposed to inspire us in our faith. We see them engulfed in sexual scandals, child abuse, political intrigue, bribery and fraud. Some are accused of direct wrongdoing, others of cover-up and dissembling. Many have lost faith not only in those who are supposed to transmit Torah but, to some degree, in the goodness and morality of the Torah itself. God’s name and His glory quite literally have been besmirched, the very definition of chillul Hashem.

In some ways, this cynicism and loss of faith may be a greater tragedy than even the very real pain suffered by innocent victims (a pain that I certainly do not want to minimize in any way). The tragedy of cynicism presupposes that everything is tainted. Nothing good is real. No one is sincere. Everything is a gimmick. Everyone is a charlatan and a faker. And what is the use of pretending otherwise? These attitudes suck up hope the way a fire sucks up oxygen. They destroy spiritual strivings. They destroy hope for the future. They engender passivity and bitterness and ultimately become a self-fulfilling prophecy of defeatism and hopelessness. It is precisely at this juncture that we have to take stock and articulate some basic simple principles.

The great Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto writes in the

introduction to the Mesillat Yesharim that he will be restating obvious principles that are known by all but are often forgotten in the pressures of the moment. And while his claim of a lack of innovation may be untrue, I humbly admit that this article will contain few chiddushim (novel thoughts). Sometimes, however, there is value in restating the obvious. Let me start with two basic points.

First, do not condemn the Torah. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once famously remarked that it is a big mistake to judge Judaism by the behavior of Jews. The Torah is greater than any one person or institution. The fact that we do not always live by its ideals cannot be an indictment of the ideals themselves.

Second, we live in an imperfect world. People are not all white and pure, nor are they all black and tainted; people come in an infinite variety of grays. The fact that we—all of us—are capable of great sin does not exclude the possibility, and the reality, that we are capable of great good. And indeed, the good that we accomplish is not forfeited by the evil that we perpetuate. As a result, we ourselves must avoid the arrogance of smugly sitting in judgment over the weaknesses and failures of others and, chas v’shalom, even gleefully rejoicing in the “downfall of the mighty” (an attitude that is quite evident on the Internet).1 Demonizing the other can sometimes be a convenient excuse to avoid our own cheshbon hanefesh (personal accounting), one that is necessary to make our communities safer, and ultimately, holier. Thus, whatever mussar I may offer, and it may occasionally sound harsh, does not come from a place of moral superiority or self-righteousness. It is not intended as a personal attack on others. I offer these thoughts as an introspective reflection directed to myself and to any others who may be interested—an enumeration of some things we can do as a community, a listing of pitfalls to be avoided and some assorted thoughts of comfort and chizuk as we face difficult and painful times.

PROTECT THE VULNERABLE

First and foremost, the Jewish community has a solemn responsibility to make its sacred spaces—shuls, mikvaot, yeshivot, day schools and camps—safe. If people have been

Since April 2010, Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz has been a maggid shiur at Yeshivat Ohr Somayach in Jerusalem and rav of Kehillat Ohr Somayach. Prior to his family’s aliyah, he was the rabbi of the Woodside Synagogue in Silver Spring, Maryland, and associate professor of law at the University of Maryland.

harmed physically, emotionally or financially, their pain must be acknowledged and addressed. They should not be dismissed as troublemakers. Our children and our adults must be protected, and those who legitimately seek to protect those in need should not be disparaged or ignored. And if recourse must be had to the secular authorities and the legal process, then so be it. Any attempt to invoke the law of mesira to shield serious abuse is misguided, if not downright evil. This is axiomatic.2

This is not the problem of any one specific synagogue or institution. It is a problem that the entire community must face. There is an element of collective guilt in the fact that we as a community allowed these abuses to occur, did not respond to the problems that were brought to our attention, ignored them, swept them under the rug. If a corpse is found near a city, the elders of the city as representatives of the community are guilty for failing to take steps that would have ensured the safety of the victim. They too are designated “spillers of blood” and they too need atonement. (See Devarim 21:1-9 and Mishnah Sotah 9:6.) We are precisely in the position of those elders.

But fixing the problem, truly fixing it, will take more than simply ensuring that bad behaviors will not reoccur. There is a history that needs to be addressed. Communities and individuals have suffered profound psychological dislocations that cannot be ignored. People have a deep sense of being violated—physically and emotionally. There is pain, anger, rage and confusion. These feelings do not just disappear by making improvements and simply moving on as if nothing ever happened. A person who suffers a vicious amputation by someone he or she admired and even loved is not restored by a prosthesis. The victims—past and potential—have voices that must be heard and respected, concerns and feelings that deserve articulation. There are, of course, laws of lashon hara, and I am not necessarily envisioning full public exposure in the media (though this happens anyway), but at least within the limited community of responsible leadership, those who were harmed must be able to speak.3

Both rabbis and laity must be educated as to what behaviors are normal and acceptable so that they (we!) will be able to evaluate whether a given behavior is outside that norm. Otherwise, people literally do not even know whether they

have been wronged; they are the proverbial child who cannot even ask the question. To the degree consistent with halachah, the appropriate standards should not be pronouncements issued ex cathedra. The offended and vulnerable populations must have a significant role in formulating these standards. This is important because they have first-hand knowledge of the problems and abuses. But equally important, such participation partially restores their sense of respect and dignity that had been so ruthlessly stripped away. It is our responsibility to “have their backs,” so to speak, and we must convey to and convince the victims that we are there for them—a daunting task since we have dropped the ball so many times in the past.

DON’T EXAGGERATE

At the same time, however, one must look at the total picture. What needs to be fixed must be fixed, but do not throw out the good with the bad. We must be careful not to exaggerate. First, the halachic requirements of judging people favorably and giving them the benefit of the doubt continue to exist. These halachot have not vanished (although a school or shul may take provisional temporary steps to prevent possible endangerment or abuse in the interim investigative period). Second, portraying the rabbinate or Torah educators, or both, in a uniformly negative light when the vast majority of rabbis and Torah teachers perform their tasks with excellence and

As one moves further and further away from the cultivation of a private intimate relationship with the Almighty, as one's persona becomes the dominant aspect of his inner reality, one's spiritual life becomes increasingly empty.

commitment is not only a scurrilous and libelous attack on dedicated people who try to serve Hashem and His people with great devotion, but is a tremendous disservice to Am Yisrael, causing many to lose respect for Torah leaders and for the Torah itself.

While even a single victimized child or adult is one victim too many, and while we as a community must try to vigorously uproot any vestige of these improprieties, the solution is not the tarnishing of a noble institution. In the superheated atmosphere of the Internet, everyone is guilty until proven innocent and indeed quite often, is guilty even after being proven innocent. In this world of hyperbole, gossip, unsubstantiated rumors and personal vendettas, a casual reader might conclude that the rabbinate, and indeed the entire Torah community, has run amuck, is utterly devoid of any semblance of morality and is nothing less than the modern incarnation of Sodom and Gomorrah. This does not reflect reality, and it is important that our children know this.

Moreover, we must avoid using the personal sins of individual rabbis as a basis for attempted overhaul of halachah. For example, many are now calling for significant changes in the time-honored halachic procedures of how female candidates for conversion should immerse in the mikvah. Without addressing the substance of these proposals, it is clear that they have nothing to do with the mikvah scandals that have erupted. As far as I know, there

have been no scandals involving these procedures and changing them would have no effect on the wrongdoing that actually took place. Calls for this type of reform are offering “solutions” to nonexistent problems and do little to fix the existing ones. They are subtle attempts to disparage halachic tradition and halachic authority. Proceed with caution.

NEED FOR BOUNDARIES

Most of the recent scandals—not all—involve abusive or exploitive treatment of women. Many, not all, of these problematic encounters started quite innocently in the context of counseling, spiritual advice and the like. What is needed is a code of ethics, a “fence” of sorts that would prevent benign encounters from escalating. No better code of ethics exists than the Shulchan Aruch itself. Counterintuitively, a rabbi may fail to apply the Shulchan Aruch to himself (and after all, who is going to correct him?). Even with the most noble of intentions, this is an enormous mistake with devastating consequences.

There are very good reasons why halachah prohibits the seclusion of a man with a woman and, in response to the plethora of litigation based on sexual harassment, these reasons have been appreciated even by secular culture.4 The laws of yichud (seclusion) and negiah (affectionate physical contact) reflect the reality that sexual attraction is a very potent, powerful and somewhat uncontrollable force, and we have the responsibility to ensure that certain lines are not crossed.5 The Shulchan Aruch generally prohibits flirtatious or intimate talk between men and women, even if the technical strictures of yichud and negiah are not violated.6 Emotionally intimate talk can easily lead to improper physical contact, or at the very least, emotional manipulation. I do not mean to draw a pejorative comparison between Modern Orthodoxy and the Chareidi/Yeshivah/Chassidic world. I am painfully aware that scandals have emerged from all camps. Nor am I suggesting the desirability of total gender separation. For good or for bad, that is not the world we live in, and it is important for women to have a rav with whom they can consult and interact in a comfortable way. But overly familiar, flirtatious, suggestive behavior is playing with fire. It can easily get out of hand, and even when it does not, it can be easily misinterpreted. Such behavior is dangerous to a rabbi’s reputation, can lead to grossly inappropriate behavior and can irretrievably damage the relationship with his own spouse. Comments about a woman’s looks, weight, attractiveness or desirability are simply inappropriate under virtually all circumstances. Any personal reference that makes a woman

uncomfortable should not be said at all. The dedicated male seminary teacher who wants to have an intense tete-a-tete with a student to help her discover the infinite richness and beauty in her soul may or may not be starting off with the best of intentions, but he is heading down a path of destruction either way.

A rabbi might justifiably feel that his intentions are leshem Shamayim, that his sole desire is to help a person in need, that he is beyond the baser instincts that may drive “regular” people astray. This was precisely the mistake of Shlomo HaMelech, the wisest of all men. He too thought he was above temptation. He too thought that the Torah’s rules against accumulating wealth and excessive wives should not apply to him because he was in no danger of losing his bearings and straying. And he discovered that we are all vulnerable and weak, that we can all fail, and that is the very reason we all need to adhere to the bright lines of the halachic system.7

We live in the era of the fallen hero, indeed, the tragic hero who is destroyed by the fatal flaw that lies within. In all walks of life, people whom we admired have disappointed us with their failures and weaknesses.

THE DESTRUCTIVE NATURE OF PRIDE AND OVERCONFIDENCE

Chazal tell us “Do not fully trust yourself until the day of your death” (Avot 2:4). Yochanan served as a righteous kohen gadol for eighty years, and yet at the end of his life became a Sadducee.8 Shlomo HaMelech was the wisest of all men and thought he was immune to temptation, yet he succumbed. On the holiest day of the year, Yom Kippur, the kriyat haTorah of Minchah is the parashah dealing with forbidden sexual relationships—adultery, incest, bestiality. Given the exalted state we reach on that day, such a reading seems an odd choice. Should we not focus on something more spiritually edifying and inspirational? The answer is, that is exactly the point. At the very height of our spirituality, at the apex of our accomplishments, we need to be acutely aware of our capacity to fail. We can never take our spirituality as a given. As righteous as we may think we are, indeed, as righteous as we may in fact be, we can easily slip and need to be vigilant. When we as rabbis are arrogant, smug and overconfident in our religiosity or Torah knowledge, and feel a sense of personal superiority over the people we have pledged to serve, it is precisely at that point that we will fail. “Pride comes before the fall” (Mishlei 16:18).

The story is told about an extremely pious individual who took every conceivable precaution to eradicate chametz from his home on Pesach.9 As he sat at his Seder joyous and confident that he had completely fulfilled the Torah’s commandments, he sees to his utter shock that

there is a kernel of split grain floating on top of his chicken soup. Overcome with grief, he faints. In his dream, he has a vision of the Almighty. He asks God two questions: How did this happen? And, why did it happen? And God answers, “Indeed your house was chametz-free, but your pot was in the fireplace under the chimney. A bird flying over your house dropped a kernel of grain into the pot, making everything chametzdik. As to why it happened, your preparations were perfect. You took every possible step to guarantee halachic perfection, except the most important one—to pray to Me for siyata d’Shmaya. You thought you were in charge; you believed you were in control. When you live with that delusion, you will fail. “Veram levavecha veshachachta et Hashem Elokecha Veamarta bilvavecha, ‘kochi v’otzem yadi asah li et hachayil hazeh,’” “And your heart will become haughty and you will forget Hashem, your God . . . . And you will say in your heart, ‘My strength and the might of my hands have made me all this wealth”’ (Devarim 8:14, 17). The arrogance of which the Torah speaks can be the result of spiritual attainment just as much as material wealth. Indeed, Chazal saw spiritual hubris as the very foundation of Dovid HaMelech’s sin. Confident of his righteousness, he challenged the Almighty to test him. God did so, and Dovid HaMelech failed. (See Sanhedrin 107a.) All people need the mercy of Hashem. Without God, all of us will fail. Infallibility is not a human trait.

A rabbi in particular may be prone to the sins of arrogance and hubris, especially if he is talented. While not necessarily the smartest person in the room, he is usually the most Jewishly knowledgeable. He determines how people are married, buried and converted. He literally makes life-and-death decisions and often has little need to justify, explain or defend those decisions. (“This is a technical halachic matter, too deep and complicated for you to understand,” et cetera.) As Lord Acton remarked, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” When there is a power relationship, when people approach you in their moments of vulnerability and weakness, and when people praise you for your scholarship, organizational abilities and debating finesse, there is the risk of arrogance, of kochi v’otzem yadi. One forgets that he is in the employ of God, and that whatever talents one was vouchsafed must be employed exclusively

for the glory of God. It becomes about you, and when you become the focus, anything goes. Dovid HaMelech takes Batsheva and sends her husband to his death. Yochanan Kohen Gadol becomes a Tzeduki after eighty years of faithful service. The messenger gets tarnished and the message corrupted when it is intertwined with power, influence and control.10

THE DANGERS OF CHARISMA AND THE PERSONALITY CULT

Both as communities and individuals, we need to avoid dependence on charismatic leadership and the personality cult. We are setting ourselves up for disappointment. The rabbi is setting himself up for the “pride that comes before the fall.” The Alter of Slobodka deliberately spoke in a dry monotone to minimize his personal charisma. He wanted people to be affected by the content of his words, not the style of his personality. Indeed, the Derashot HaRan11 teaches that Moshe Rabbeinu was kevad peh and kevad lashon (had a serious speech impediment) precisely for the reason that people should not elevate him to the status of a demigod and be moved and inspired by his hypnotic oratorical abilities. (For the same reason, the Torah conceals the place where Moshe is buried12 and, according to some commentaries, this is also why Moshe’s name is not mentioned in the Pesach Haggadah.)

Rabbi Berel Wein13 describes the dangers of charismatic leadership very well:

We love the flash of brilliant insight, the devastating quip, the broad permanent smile, the warm embrace and the hero

worship that characterize the person who possesses that elusive quality of charisma . . . . Yet, like all other seeming blessings, charisma carries within it seeds of self-destruction.

The charismatic personality is likely to succumb to the temptation of believing all of the adulation showered upon him or her. In the triumphant parades of the Roman emperors, a servant rode along in the emperor’s chariot and whispered to him, amidst the din of the cheering throngs, a reminder of his past failings and future mortality. Believing in one’s own charismatic qualities builds one’s ego to ferocious heights. And an inflated ego always leads to downfall and personal defeat. It allows the guilty to eventually believe in their own perfect innocence and to expect others to do so as well. Prideful haughtiness goes before a fall, opined King Solomon long ago. Prideful haughtiness is very often a byproduct of the charismatic personality.

Similarly, Naomi Mark,14 a clinical psychologist, has written about the strong correlation between charisma and narcissism. She quotes psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut, who, describing the narcissistic personality, notes the “high energy levels, the apparent confidence and lack of self-doubt, and the strong sense of mission.” These qualities can be the very qualities that produce outstanding

leadership but become pathological when the “grandiosity, fantasies of success, lack of empathy, excessive need for attention and approval, and inability to tolerate [alternative viewpoints] interfere with the individual’s functioning in work and love.” The very character traits that make a candidate alluring and attractive may be the source of serious difficulties down the road.

There is yet another danger that charismatic leadership poses, a more subtle one that may be especially damaging to adolescent students, ba’alei teshuvah and candidates for conversion. Such leadership tends to be autocratic, controlling and disparaging of individual choice and personal autonomy (even within the bounds of halachah). These are warning signals that should not be ignored. Leadership that tries to micromanage not only institutions but individual lives is inherently suspect. At least within the non-Chassidic tradition, the role of rabbis, roshei yeshivah, teachers and spiritual mentors is to inform, educate and inspire, not to command and direct. The students/congregants are expected to think for themselves and to have the ability and maturity to make decisions and take control of their lives; the rabbi’s function is to enable and enhance the development of those capacities.

From my own personal experiences, I can say that this was very definitely the approach of my roshei yeshivah, Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman and Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg, as well as that of Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky, all of blessed memory; and this was deeply rooted in the teachings of the Alter of Slobodka. As mechanchim par excellence, they saw their role as helping the student formulate his own approach to life and not simply be an automaton blindly following either the leader or the crowd. From the disciples of the Rav, I gather that Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik was exactly the same. This indeed was historically characteristic of the Litvishe gadol. 15

Even within the Chassidic world which, to some degree, has a different mesorah, there is at least the occasional exhortation to “think for yourself.” My wife’s experience with the greatly lamented Rabbi Shlomo Twerski is instructive. He would often declare with great passion that neshamot are not cookie dough to be cut in uniform shapes and sizes but precious diamonds to be cleaned and polished, exposing the beauty and luster from within; the goal of the rebbe is to help the talmid discover the uniqueness and individuality within himself.16

Leadership predicated on personal charisma, however, does exactly the opposite; it discourages autonomy and confidence on the part of the congregant or student, fosters an unhealthy dependency and vulnerability, limits the capacity for self-expression and inner spiritual growth and, in the guise of a connection to a respected religious authority, may actually undermine the development of a personal relationship with God. Moreover, by linking one’s Judaism so closely to the charismatic personality of an individual rather than to the Torah and Hakadosh Baruch Hu, the relationship to God may be totally destroyed when the all-too-human intermediary fails or falters.

sensitivity, et cetera. In this way, he was the forerunner of the Mussar Movement founded by Rabbi Yisrael Salanter. (In fact, Rav Salanter was the disciple of Rabbi Yosef Zundel, a hidden tzaddik who studied under Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, the greatest talmid of the Gra). Indeed, the Gra, who could hardly be accused of devaluing the study of Torah, writes repeatedly that tikkun hamiddot (rectification of character) is the central purpose of our existence.18

It is equally true that in choosing a rav or spiritual mentor, one of the most important qualities to look for are middot tovot. “If the teacher is comparable to an angel of God, seek Torah from his mouth. Otherwise do not.”19 A rav is compared to the kohen,20 who in turn is described in Avot (1:12) as “ohev shalom v’rodef shalom,” “one who pursues peace and loves peace, loves all of God’s creations and endeavors to bring them close to Torah.” Indeed, Rambam codifies as a matter of halachah that one should not learn Torah from a teacher who does not follow the good path no matter how learned he may be.21 Torah is more than disembodied information. It emerges not only from the mind but from the totality of the soul. We must endeavor to find teachers who have the qualities of the soul within which Torah can reside.

Believing in one’s own charismatic qualities builds one’s ego to ferocious heights. And an inflated ego always leads to downfall and personal defeat.

CHOOSE YOUR RABBI CAREFULLY

Erudition, scholarship and personal magnetism are no guarantee of spirituality and inner goodness. Chazal tell us that Torah is compared to water. The Vilna Gaon (Gra) offers a fascinating explanation. Water has the capacity to cause growth of whatever seeds it happens to fall on. If the seeds are wheat, the water will cause the germination of wheat; if the seeds are poisonous weeds, the water will facilitate the growth of weeds. So too Torah learning will develop and accentuate the preexisting qualities of the soul. If one is imbued with compassion, kindness and humility, then Torah study will make him more so. If one is competitive, arrogant and self-aggrandizing, Torah scholarship will simply create another battlefield in which those qualities can be expressed.17 As such, the Gra emphasizes the need to combine analytical Torah study with conscious development of character, interpersonal

All of this suggests that communities must pay much closer attention to the moral qualities and personality traits of the leaders and role models that they choose. That certain flashy qualities might be overvalued in the selection process while other qualities—gentleness, modesty—are undervalued or even disparaged will only hurt the community in the long run.

THE COMMUNITY’S NEED: TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Why does the Torah go into so much detail about the korbanot, and why is a kohen not permitted to contaminate himself by contact with a corpse? Rabbi Saul Berman22 once offered an intriguing thought. The kohen has great power; the power to effect atonement, reconciliation with the Creator. He has access to holy places that no one else may enter. He can perform rituals that no one else can perform. He is in charge of a cosmic apparatus that literally determines the survival of the world. This puts him in a position of control, and with that control comes the potential of abuse and manipulation. The antidote is transparency and accountability. Every Jew is entitled to know what the avodat hamikdash is and how the kohen performs it. The avodat hamikdash must be demystified and clearly explained so it does not become a force of control. For the same reason, the kohen effectively distances himself from people at the moment of their

greatest vulnerability and weakness, for it is precisely at those moments that the potential for manipulative control is at its maximum. Rabbi Berman suggests that these considerations have relevance to the rabbinate as well. Rabbinic rulings, procedures and standards should not be seen as arbitrary, mysterious pronouncements whose authority is grounded in personal charisma but should be explained in terms accessible to the kehillah. While it is incontestable that a rabbi must be the final halachic authority within his congregation, it is equally true that he must be able to explain his positions, his standards and his behaviors. As Justice Louis Brandeis remarked in a different context many years ago, “Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” Anything that cannot be explained was probably not justified in the first place. Rabbi Yossi aptly stated, “I never did anything for which I had to turn around and see who was watching me” (Shabbat 118b).

THE RABBI’S NEED: A CHAVER AND A REBBE

Numerous statements in Tanach and Chazal emphasize the importance of consulting others and learning from others, both in terms of Torah and in the practical dayto-day decisions of life.23 “Aseh lecha rav u’knay lecha chaver,” “Make for yourself a teacher and acquire for

yourself a friend/colleague” (Avot 1:6); “Eizehu chacham halomed mikol adam,” “Who is wise? He who learns from all people” (Avot 4:1) are just two of many examples. Indeed, even Hakadosh Baruch Hu “sought,” as it were, the counsel of the angels before creating man (“Let us make man”).

As great a figure as Rabbi Elazar Shach stated that it is essential that decision-making be a collaborative enterprise, that different viewpoints be shared and expressed, and he would refuse to give a haskamah to any mosad (institution), no matter how noble, where all the decisional authority was entrusted to a single individual.24 Autocratic leadership results in bad decisions, but even worse, it inculcates a sense of superiority, invulnerability and being above the law. “Do not judge alone for there is only One who is qualified to judge alone” (Avot 4:10).

But the need for a chaver and a rebbe goes well beyond the specifics of particular decisions and policies. Rabbis are professional purveyors of Judaism. “Spirituality” is their bread and butter. Paradoxically, a rabbi may be so busy marketing his religion that he has little time or energy to replenish his own spiritual batteries. And yet, one cannot truly give what one does not possess. (“That which is always giving out is unable to absorb.” 25) As one moves further and further away from the cultivation of a private intimate relationship with the Almighty, as one’s public persona

It is especially vital that we communicate to our children not to lose faith in humanity, in Judaism and in themselves . . . not to succumb to cynicism and despair.

becomes the dominant aspect of his inner reality—as indeed there may be no inner reality—one’s spiritual life becomes increasingly empty.26 When that happens, there is the real risk that the vacuum will be filled with the incessant (and ultimately self-defeating) drive for kavod, recognition, honor and ego gratification.27 And when these become our primary motivators in life, we become vulnerable. We face self-idolization at worst; at best, the empty shell of burnout. We become the “rabbis at risk” who eventually put our communities at risk.

Every soul needs to be nourished authentically, and Chazal’s admonition of “aseh lecha rav u'knay lecha chaver” is not simply practical, pragmatic advice for good decisionmaking, which it surely is, but a call for personal growth. A rabbi needs a space where he can shed the persona of the professional and be a simple person, a pashuter yid. He needs mentors and colleagues with whom he can learn and grow and, at least for a short time, escape the tensions of communal life. He needs to hear the still, small voice of God (kol demamah dakah)28 that is within him, to hear the sounds within the silence, away from the roar and the acclaim, or the derision and abuse, of the crowds, to rediscover himself and thereby find the Almighty.

THE POWER TO CHANGE, THE GIFT OF TESHUVAH

Virtually every person who enters the rabbinate is a person of high idealism, devoted to God, Torah and the Jewish people—one who genuinely wants to make a difference for the good in the lives of fellow Jews and is willing to make great personal sacrifices to accomplish this mission. This is certainly true of the great majority of rabbis who perform their duties with integrity, with nary a whiff of scandal, but it is also true for the rabbis who fail. They too brought to their ministries qualities of goodness, devotion, commitment and self-sacrifice. They too have done much good, and they too have the potential to do much good in the future. To paraphrase an old commercial, “a life is a terrible thing to waste.” Although some might criticize any focus on the pain suffered by these “fallen rabbis” (i.e., who cares?), it is precisely that pain that I want to address, for there are lessons to be learned both for them and for us. It is especially vital that we communicate to our children (and that necessitates that we believe it ourselves) not to lose faith in humanity, in Judaism or in themselves; not to succumb to cynicism and despair; to hear and internalize the message that yes, even great and good people make mistakes, but in the aftermath of failure, there is the possibility, and therefore the obligation, of rebuilding.

This lesson is of such crucial importance that it may be the reason why the malchut of the Jewish nation was assigned to the Tribe of Yehuda rather than to the Tribe of Yosef. One thought that appears with some frequency in sifrei Chassidut and kabbalah29 focuses on the different ways these two personalities respond to temptation. Yosef successfully rises above sin, simply defeats it; “just says no.” We stand in awe of his moral perfection and spiritual strength. Yehuda, on

the other hand, succumbs to temptation in a moment of weakness as his descendant Dovid HaMelech does later. He fails, but through sincere and honest teshuvah and by taking responsibility for his misdeeds, he is forgiven. God wanted us to fully appreciate the awesome power of teshuvah to elevate and purify and thus chose the ba’al teshuvah over the tzaddik gamur. God’s message is one of hope, recovery and resilience.

Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner30 noted long ago that although we are very familiar with the great successes of our gedolim—their brilliance, their hasmadah (diligence), et cetera—we know much less about their struggles, their mistakes and their failures. But in many ways, knowing how they dealt with setbacks and disappointments might be far more useful and instructive than simply viewing them as superhuman and perfect. (He was thus a bit

critical of the hagiographic tendencies in the biographies of gedolim.) The true measure of greatness is growing and learning from our failures. “The tzaddik may fall seven times and rises” (Mishlei 24:16) does not mean he rises despite falling but rather it is the very confrontation with his inner demons that is the source of his greatness.

Thus, it is essential that those who fail—and those who sit in judgment on that failure—carefully ponder three points:

1. If you believe it is possible to destroy, believe it is possible to rebuild.

2. The good that a person does is not destroyed by the evil.31 A lifetime of good work, Torah scholarship and helping countless people in need is not destroyed by sin or mistake. Every person will have to give a din v’cheshbon for his aveirot, but the bad does not cancel out the good.

The good remains. The good within the person remains. It is still there. The fact that someone fails does not mean that his or her life was a failure.

A story is told that the Gra was once in prison together with a Jew who was a convicted murderer. When bread was brought to the cell, the murderer proceeded to eat without netilat yadayim. The Gra told the murderer that he is obligated to wash his hands. When his cellmate remarked that he was guilty of far greater sins than neglecting netilat yadayim and could not imagine that washing would make any difference to the Almighty, the Gra responded that one has nothing to do with the other. One may be guilty of the most heinous of sins, but God still desires that whatever good one can do, one must do. The good remains.32

3. Divine gifts come in many forms, and sometimes the gift of devastating personal failure is an opportunity to acquire humility. People can and do change as a result of confronting their inner demons. “God does not desire the strength of the horse nor the thighs of man. God favors those who fear Him, those who yearn and hope for His loving kindness” (Tehillim 147:10-11). Rabbi Tzadok of Lublin33 explains that the “strength of the horse” metaphorically refers to the energy and the effort we put forth in trying to do good in the world. The “thighs of man” refers to the self-control we exhibit in holding ourselves back from committing evil. Both are important and valuable. But both can be tainted with smugness, arrogance, ego and self-righteousness. What God treasures above all are the qualities of humility and modesty, as well as an awareness that all that we are and all that we accomplish are only by the grace and mercy of God, that left to our own devices failure is inevitable. (Thus, we need to yearn for God’s loving kindness.) It is precisely this awareness that enables us to treat others with respect, to admit when we are wrong, to be open to positive and constructive criticism and to change for the better. And it is precisely this awareness that ultimately empowers us to be a faithful conduit of Hashem’s Torah.

how they responded to the rebuke of the prophets. When the prophet Shmuel confronts Shaul, Shaul first denies the accusation (“I did the will of God”) and then blames others for his failure. By contrast, when Natan communicates to Dovid the enormity of his offense through the parable of the rich man and the lamb, all Dovid does is utter two words, “chatati laShem,” “I have sinned.” No excuses, no mitigating circumstances, no blaming of others. 36 Indeed, Dovid followed the noble example of his ancestor Yehuda who similarly stepped forward to declare publicly “tzadkah mimeni, ” “she [Tamar] is more righteous than I.”37 God does not expect our leaders to be perfect; God does expect them to take responsibility when they fail.

Divine gifts come in many forms, and sometimes the gift of devastating personal failure is an opportunity to acquire humility.

Second, teshuvah requires seeking the forgiveness of those who were wronged, primarily specific victims but including also the community as a whole that experienced significant betrayal.38 Rabbi Hutner39 eloquently explains that when a person hurts another, the damage he inflicts is not only the particular hurt the victim suffered but the fact that the victim feels psychologically violated, less secure in the world, bitter, angry, betrayed, less able to trust. The victim, in a sense, has become diminished as a person, and the perpetrator must do what he can to restore the person to his or her wholeness. Bakashat mechilah (asking forgiveness), then, is not simply an apology for the past but an attempt at restoration. And learning how to forgive is part of that restorative healing process as well. We are all weak and vulnerable, and we should look at all people with compassion and forgiveness. We must learn to forgive not only for the benefit of the sinner but for ourselves. A heart filled with anger and resentment can never move on. It is stuck. There is no room for God.

But teshuvah is neither easy nor cheap. First, teshuvah necessitates taking responsibility for one’s actions rather than denying, equivocating or blaming others. When Shaul HaMelech failed to fulfill his duty to eradicate Amalek, he was not given a second chance. He was told that the malchut would be taken from him and given to someone better and more suitable. When Dovid HaMelech, on the other hand, committed sins that were arguably more severe, i.e., adultery and murder,34 he remained king and indeed his dynasty will produce the Mashiach. Rabbi Yosef Albo35 suggests that the key distinction between Shaul and Dovid lay not in the nature of their sins but in

Third, teshuvah does not automatically mean restoration to a prior position.40 To take an extreme case, no sane person would argue that a repentant child molester should go back to teaching children. This is so for two reasons. First, it is impossible for anyone to gauge the true depth and sincerity of the teshuvah process. Second, even a sincere teshuvah may not be able to withstand a strong, overpowering temptation and the ba’al teshuvah may falter.41 We simply cannot take the chance that innocent people, especially children, may be harmed. Nevertheless, assuming we can minimize these risks, the person who takes responsibility, works to improve and sincerely seeks the forgiveness of those he harmed deserves the gift of a second chance to be of service to Klal Yisrael. All of us earnestly pray that God will give us these chances when we need them. God shows us the compassion that we are able to show to others.42 g

CAN THERE BE TESHUVAH FOR CHILLUL HASHEM?

The sin of a spiritual leader, especially when that sin becomes known to the public, carries a much greater level of severity. In addition to the sin itself, there is a chillul Hashem, a desecration or profanation of God’s name, as the rabbi’s misconduct brings shame and disgrace on the Torah.43 This would even be the case if the misbehavior would not otherwise be a serious sin (e.g., rudeness in the checkout line or cutting someone off in traffic), and the chillul Hashem is obviously compounded by the gravity of the offense. According to Rambam,44 one who is guilty of chillul Hashem has no atonement (kaparah) until the day of death. Neither teshuvah nor Yom Kippur nor even suffering can erase the stigma of the sin. Standing alone, this ruling might suggest that although teshuvah is a necessary component for forgiveness, it is insufficient; there is literally no atonement possible within the confines of Olam Hazeh. However, this ruling does not, in fact, stand alone and other factors must be considered. There are at least five halachic arguments that suggest that even the sin of chillul Hashem is amenable to sincere teshuvah.

First, Rabbeinu Yonah of Gerona,45 in his classic work Shaarei Teshuvah (a work that the Chofetz Chaim consistently treated as an authoritative halachic—not just mussar—source), posits that even the perpetrator of chillul Hashem can receive atonement by dedicating his life to kiddush Hashem, acts of loving kindness and intensive Torah study, that God in effect gives the penitent the chance to repair the desecration of God that he caused by bringing glory and honor to the Almighty’s name.

Second, even Rambam himself seems to concede that sincere teshuvah restores man’s relationship with God, irrespective of the magnitude of the sin, apparently including even chillul Hashem. In chapter 7 of Hilchot Teshuvah, Rambam writes: Teshuvah is great for it draws a man close to the Shechinah . . . . Teshuvah brings near those who were far removed. Previously, this person was hated by God, disgusting, far removed and abominable. Now, he is beloved and desirable, close and dear. How exalted is the level of Teshuvah! Previously, the [transgressor] was separate from God, the Lord of Israel, as (Isaiah 59:2) states: “Your

sins have separated between you and your God.” He would call out [to God] without being answered, as (Isaiah 1:15) states: “Even if you pray many times, I will not hear.” He would fulfill mitzvot, only to have them crushed before him, as (Isaiah 1:12) states: “Who asked this from you, to trample in My courtyards,” and (Malachi 1:10) states: “‘O were there one among you who would shut the doors that you might not kindle fire on My altar for no reason! I have no pleasure in you,’ says the God of Hosts, ‘nor will I accept an offering from your hand.’” Now, he is clinging to the Shechinah, as (Deuteronomy 4:4) states: “And you who cling to God, your Lord.” He calls out [to God] and is answered immediately, as (Isaiah 65:24) states: “Before you will call out, I will answer.” He fulfills mitzvot and they are accepted with pleasure and joy, as (Ecclesiastes 9:7) states: “God has already accepted your deeds,” and (Malachi 3:4) states: “Then shall the offering of Judah and Jerusalem be pleasing to God as in the days of old and as in the former years” (translation by Rabbi E. Touger).

In contradistinction to chapter 1 where teshuvah’s power of atonement is quite limited, chapter 7 describes teshuvah as completely transformative and purifying, fully restoring a relationship of love with the Almighty, allowing the ba’al teshuvah to find favor and grace in God’s eyes once again. Apparently, the need for atonement (kaparah) in chapter 1 is connected to a spiritual “debt,” a liability that is owed for the sin, a punishment that must be expiated—a burden that is not erased until death, and one that the ba’al teshuvah must always carry in his heart—but the existence of that debt/liability is not relevant to the purity of the penitent’s soul and his reacceptance into the community of God and Israel, provided he complies with the requirements of the teshuvah process, e.g., seeking forgiveness from victims, et cetera.46 It is only the kaparah aspect of teshuvah that is limited; its power of taharah (inner spiritual purity) is boundless, limited only by the sincerity of the sinner and the depths of his contrition and resolve. Three other arguments, less rooted in the language of Rambam and Rabbeinu Yonah, are presented in the footnote.47

EMPIRE

AD

Notes

1. See Rambam, Hilchot Teshuvah 4:4, where he discusses the very great sin of getting honor, i.e., smug satisfaction, out of the downfall or humiliation of others (mitchabeid b’klon chaveiro). This is often described by the German word “schadenfreude.”

2. Mesira is the prohibition of one Jew “informing” on another Jew by notifying non-Jewish authorities. See Rambam, Choveil U’Mazik 8:9-10. The moser (informer) was such a despicable person that he could be summarily executed. Some have applied the concept of mesira to prohibit the reporting of abuse to secular law enforcement, but this is an error. See the ruling of Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv in a 2004 letter to Rabbi Feivel Cohen, Kovetz Teshuvot III, no. 231. I am not addressing the very controversial question of whether a rav needs to be consulted first. Compare Rabbi Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer’s article in Jewish Action (“Discovering Rav Elyashiv,” summer 2013) and the subsequent letter to the editor by Ben Hirsch appearing in the fall 2013 issue.

3. As important as the laws of lashon hara are, they cannot stifle the need to redress evils and prevent harm. The Chofetz Chaim discusses at great length when and how a person who has suffered harm by the actions of another party may discuss that harm with others in order to prevent its reoccurrence in the future. See Chofetz Chaim, Laws of Lashon Hara, Klal 10, par. 11-14. He further suggests that there may be (“efshar”) a separate positive and legitimate benefit in enabling people to express their fears, anxieties and resentments if this could bring them to a certain degree of inner healing and closure, citing the verse in Mishlei 12:25 (as interpreted by Yoma 75a): “If there is worry in the heart of an individual, let him share that worry with another.”

4. As employers seek to minimize liability for sexual harassment claims, companies are adopting increasingly strict workplace codes concerning dress, workplace romance, seclusion with the opposite gender, over-familiarity, suggestive flirtatious speech, et cetera. As strange as it may sound, modern employee handbooks are beginning to resemble the “outdated” rules of the Shulchan Aruch

5. The story of Dovid and Batsheva is, of course, the classic example. See II Samuel 11-12. Much of the Book of Mishlei warns the wise son to avoid sexual temptation. See, for example, Mishlei 2:16-19; 6:24-35; 7:5-27 and 9:13-18. While these verses do have allegorical or symbolic meanings, “Ein mikra yotzei midei peshuto,” “The straightforward interpretation is not displaced,” and these warnings are to be taken literally as well. Similarly, Ketubot 13b teaches,“Ein apotropus l’arayot,” “There is no guardian in matters of sexuality,” i.e., no one can be trusted. We must all take precautions. In Kiddushin 81a, the Talmud recounts three separate stories of great rabbis—Rabbi Amram Chasida (the pious), Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Meir—each having almost uncontrollable lust for a beautiful woman. All three of these righteous and holy men were on the verge of succumbing to temptation, pulling away only at the last minute.

6. See Shulchan Aruch, Even Haezer 21:1, 21:6 and 22 for the basic halachic guidelines governing the relationships between men and women.

7. Sanhedrin 21b (explaining why the Torah generally does not give the reasons for its commandments, so that people should not argue that the reasons do not apply to them when, in fact, those reasons would).

8. Berachot 29a. While not relevant here, there is considerable discussion whether this Yochanan might be the father of

Matityahu, the hero of the Chanukah story. If indeed he was, this might explain why Matityahu was so opposed to the Hellenism prevalent in Eretz Yisrael. He saw firsthand how it destroyed the righteousness of his father.

9. I believe I heard or read this story from Rabbi Moshe Wolfson but cannot presently locate the source.

10. A further example of the dangers that power poses to the integrity of spiritual leadership may be gathered from the words of Ramban. In pointing out why the Hasmonean dynasty was ignominiously eradicated although its founders were righteous, Ramban, Bereishit 49:10, offers two explanations. The first, and better known, is that it was sinful for any tribe other than Yehuda to assume the monarchy. After the Maccabee victory, a king should have been appointed from the Davidic, or at least from the Yehuda, line. But the second answer, based on the Jerusalem Talmud, is that there is a discrete, unique prohibition for a kohen to serve as a melech. While no explanation is offered, one might suggest that there is an inherent risk in giving spiritual leaders too much power in the political realm. The need to separate church from state is not to protect the state from the teachings of religion but to preserve the integrity of religious ideals from the corrosive effect of power and manipulation. Interestingly, in 1980, Pope John Paul II promulgated a similar policy prohibiting clergy from holding political office, resulting in the forced retirement of Congressman Robert Drinan, who was also a Jesuit priest. Ramban’s words also have interesting implications for Israeli politics.

11. See Derashah III, p. 38 (Feldman Hebrew Edition). The Ran’s

even on Shabbat and Yom Tov?

Come See Why We Love West Hartford, CT

Explore Our Central Connecticut Jewish Community

Kosher Food • Mikveh • Eruv Orthodox Synagogues Jewish Schools

The Hebrew High School of New England Sigel Hebrew Academy

Jewish Federation of Greater Hartford Mandell Jewish Community Center

actual explanation is a bit different than mine. He states that had Moshe been an eloquent, articulate speaker, future generations might not be convinced of the Divinity of the Torah. They might attribute the beliefs of their ancestors to Moshe’s charismatic abilities. By contrast, if Moshe lacked those abilities but the people were still convinced, that fact establishes the Torah’s veracity as the word of God. My point, building on the Ran, is that charisma also distorts the messenger and can subtly change the message so that, in fact, it may not be the Divine teaching in its purest form.

12. See commentary of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch in The Hirsch Chumash, Devarim 34:6.

13. Rabbi Berel Wein, “Charisma,” www.rabbiwein.com.

14. Naomi Mark, Ph.D., “Charisma and Narcissism in the Jewish Community,” www.shma.com. Mark’s article was part of a symposium on the issue of charisma and leadership published by the online journal Sh’ma, A Journal of Jewish Ideas, in December 2006. The journal had a second symposium on the topic in March 2009. All of the articles are well-worth reading and may be accessed at the Sh’ma web site.

15. See commentary of the Vilna Gaon, Mishlei 16:4 (“Train a child according to his way”) and, more generally, anecdotes in Rabbis Berel Wein and Warren Goldstein’s The Legacy: Teaching for Life from the Great Lithuanian Rabbis (Jerusalem, 2013).