Quarterly THE CATHEDRAL

OUR MISSION Inspired by the love of Jesus, we are building the kingdom of heaven, where differing people live in community, serving God and each other.

Many of you have heard about my new kitten Zoe. I saw her in the middle of Roosevelt Boulevard, crouched down while cars drove right over her. Miraculously, she hobbled across three lanes of traffic and was not killed! She has one leg that is unresponsive, but other than that, she is fine.

When I first held Zoe, she trembled. She was dirty and covered with fleas, in pain, and had some head trauma. After the vet examined her, we brought her home, and my husband and stepdaughter had to pick off the fleas one by one (she was so small that we couldn’t use flea medication).

We think that someone must have thrown Zoe out of a car window. She was just six weeks old at the time and very small. In addition to her physical wounds, she just needed to be held. Zoe (I named her for the Greek word that means Life) needs to know that she belongs to us and we to her.

The world that we live in encourages individuality and self-sufficiency, and these are good things. But human beings also need to belong to one another. And most of all, we need to understand, deep inside our hearts, that we belong to God.

The very nature of God is communal. Christians are taught that God is three in one and one in three. We call this concept The Trinity, and it makes no sense intellectually. But it does tell us that God has community within the divine self. And when we are together, we reflect the very nature of God.

Jesus said, “When two or three are gathered together in my name, I am in the midst of them.” (Matthew 18:20). Jesus was trying to tell us that God can be most present with us when we belong to one another. When we are isolated and alone, it is harder for God to be present because we become easily tempted, get side-tracked, and can wander into despair.

Zoe is thriving! Each morning, she greets me with purrs and dashes around the room. She knows now that she is loved, that she belongs. Never forget that you belong to the Body of Christ. Do not let yourself get too far away from your church community. I know that other people can be frustrating and aggravating at times, but Jesus traveled with twelve disciples, and we too must travel together. In this way, we can enter the very heart of God and not be trampled by the chaos of this world.

In Christ’s Love,

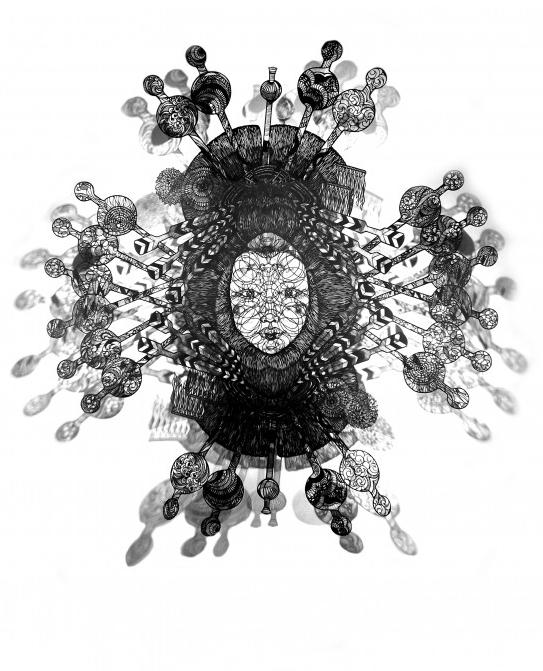

CENTRAL SYSTEM | Juana Gomez

by Steve Garnaas-Holmes

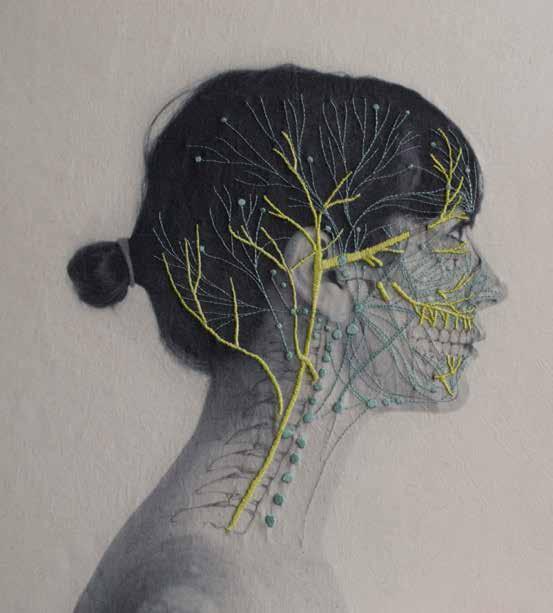

The cells in your body love what they do.

Nerve synapses adore each other, holding hands, sharing secrets all the time.

Your glands, twinkle in their eye, distribute their gifts. Your muscles don’t move from duty, but joy. Your lungs, even when troubled, love the air and love passing on its riches. White blood cells sweep the streets because they love everyone who lives there. Ligaments and tendons hang on and when severed long for each other. See when you’re cut how skin reaches for skin, tissues embrace like lovers.

The members of the body care for one another. They gather at each other’s sickbeds. When the village is not well all its citizens pitch in, each doing their best for the whole, because they love each other.

Beat by beat your heart speaks in you —let it be your life—

Oh Yes. Oh Yes. Oh Yes....

True belonging is the spiritual practice of believing in and belonging to yourself so deeply that you can share your most authentic self with the world and find sacredness in both being a part of something and standing alone in the wilderness. True belonging doesn’t require you to change who you are; it requires you to be who you are.

~Brene Brown

by Carrie Newcomer

I was riding my bike down a long country road, my head full of some problem that was weighing upon my mind. I peddled mile after mile lost in the turning wheels of my mind, barely noticing the way the wheels of my bike were in motion and yet some part of them always touching the earth. Just then three brilliant yellow goldfinches flew across my path, so close I felt a puff of air from their fluttering wings. It was like waking from a dream, the sky was clear and cornflower blue. There were spirals of newly harvested hay dotted across the fields, glowing in the late afternoon sun, looking like a herd of large round gentle creatures. The light was golden, the way it gets when the earth has tilted on its axis and the fall solstice is near. And in that moment, I was filled with joy and utter gratitude.

IT

WAS MORE THAN JOY, IT WAS TRANSCENDENCE, A FEELING OF COMMUNION AND CONNECTION, THE LIGHT IN ME HOLDING HANDS WITH THE LIGHT THAT CAME INTO THE WORLD LONG BEFORE THE SUN AND THE MOON. THIS WAS THE WAY MY SOUL ACTUALLY SEES THE WORLD, ASPIRES TO LIVE IN THE WORLD, HOPES TO MANIFEST IN THE WORLD. AND YET, IT SLIPS AWAY, I FALL ASLEEP, AND I FORGET.

I am grateful that this incident was not a singular moment. I have felt it when an orchestra swelled and then calmed, when a poet spoke a line so true everyone had to stop breathing for a beat, when I picked up a smooth stone by the lake, when my old dog pressed her head into my sternum, when I pulled up a huge sweet potato from the womb of the garden, when I was just looking out the window at the morning pond, when chanting with monks at an Abbey in Kentucky, again and again and again when I’m

singing, when walking on a path I’ve walked thousands of times, when watching my infant daughter sleep, when my dear friend passed from this mystery into the next, when our voices echoed across the canyon, and when I arrived home and the porch light was still on and shining in the dark. Yes, and there are more. There are always more.

Which makes me wonder, and at times believe that our moments of transcendence are not the dream, but perhaps our own true state. Perhaps being lost in the turning wheels of what really doesn’t matter is actually when we are sleepwalking—asleep until three extraordinary golden finches cross my path and invite me into the here and now.

I imagine if I were a realized Bodhi or actualized saint or completely enlightened being I would be in that flow state all the time, but then I suppose I would need to figure out how to pick up the groceries or walk the dog or scratch my nose or pay the bills. And so, mere mortal that I am, I’ll just keep looking out the window, I’ll try to stay open, and to always be grateful whenever I wake from the dream and step once again into the holy now.

from the 2025 Episcopal Parishes Network Conference

When we erase difference, we fail to live into the gift of the Holy Spirit and the promise of comfort. The word comfort is derived from the Latin word confortare, which means to strengthen greatly. There is great strength and comfort when we honor, celebrate, and find belonging within the triune God’s proliferation of differences. The great Black lesbian philosopher Audre Lorde writes, “Without community, there is no liberation. But community must not mean a shedding of our differences, nor the pathetic pretense that these differences do not exist. All people are images of the Holy Trinity.”…

Belonging is the air we breathe. Indeed, it isn’t like the air, it is the very oxygen that fills our lungs. We don’t exist from one another. We cannot breathe without the people, the places, and values that form our life. When we inhale, our bodies acknowledge our dependence on others. Belonging, like the air we breathe, permeates the fullness of our existence. And so we are reminded that we exist in a symbiotic and an enduring state, a mutuality of giving and receiving our breath from others. When we exhale, we offer our life, our sense of self, our hopes and intentions out into the world. We belong to each other, and we belong to God. This is the fundamental reality that grounds and forms our lives, making all life possible…

Belonging is the question of our generation.

by The Rev. Canon Mark Anderson

At the center of every human life is a longing: to be known, seen, and loved. That longing points us toward three essential connections: belonging to God, to others, and to ourselves. These paths, when braided together, help us find peace.

First, to belong to God is to know, deep in your bones, that you are not defined by performance or productivity. That truth doesn’t demand striving. It invites rest. You are loved, not because you earned it, but because you are. That’s God’s grace.

Second, to belong to others is not the same as fitting in, which requires the real you to hide. Belonging allows you to show up as you are — messy, complex, unfinished — and still be welcomed with love. True community doesn’t erase difference. It honors it. It creates space for vulnerability and sacred worth. A space where people say, “You matter. You have a place at our table.”

Third, belonging to yourself. This may be the hardest. To belong to yourself is to be honest with who you are, not the curated version. It means living with integrity, letting your beliefs, values, and actions align. It’s not about ego. It’s about peace. When I belong to myself, I don’t have to pretend. I can move through the world with courage and clarity.

These three cords — God, others, self — form the spiritual architecture of a whole life.

For generations, our connection to the divine was nurtured through shared religious life. But those rhythms are fading. In 2000, 42% of Americans attended church regularly. By 2023, only 30% did. In 1999, 70% said they were members of a church, synagogue, or mosque. In just 20 years, that number dropped below half. Belief hasn’t disappeared; but the institutions that once held our spiritual lives no longer anchor us.

Our connection to each other is also in sharp decline. Sociologists call this “social capital.” Most of us call it friendship. Young adults now experience 70% fewer social interactions than two decades ago. In 1990, a third of Americans had 10 or more close friends. By 2021, only 13% did.

Robert Putnam, in his book Bowling Alone, described this unraveling. America has many fewer bowling leagues than in the 1950s. Americans are still bowling he says, but now, they do it by themselves. Civic clubs, volunteer groups, neighborhood gatherings are thinning out. We’re doing the same activities, but by ourselves.

Finally is our connection to ourselves. In 2014, 8% of Americans reported struggling with depression. By 2023, it was 13%, a 50% increase in less than a decade. Among young adults, it’s more than doubled.

We are becoming strangers to God, to one another, and even to ourselves. And yet, in the midst of all this disconnection, something else is rising: longing. Recent surveys show that 74% of Americans want to grow spiritually, and 77% still believe in a higher power. The hunger hasn’t vanished; it has intensified.

In 2012, only 4% of Americans practiced meditation regularly. By 2017, that number had tripled. Spiritual books are booming. People are seeking. They’re trying to find a path. Yoga. Therapy. Mindfulness. These aren’t always faith-based, but they’re rooted in a sacred impulse: the desire to find connection, purpose, and peace.

As Dickens wrote, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” That paradox fits our moment. Institutions are declining, yet spiritual hunger is growing. People feel unmoored, yet they are reaching out. The data tells us: people want to belong. They just don’t know where to look.

In the earliest chapters of Genesis, we find a poetic glimpse of life as it was meant to be. Before the noise, before the hiding, before the fracture, there was a garden. And in the Garden of Eden, all three dimensions of belonging – to God, to other, to ourselves – were present, holding together in harmony.

Adam and Eve didn’t just believe in God from a distance. They walked with God, moving through creation in communion with the One who made them. There was no striving. No shame. Just presence. Just love. Their worth was not earned. That’s what belonging to God looks like.

When Adam sees Eve, and he cries out, “This at last is bone of my bone,” it’s not a statement of ownership; it’s a moment of recognition. Of joy. Of connection. They were naked and unashamed, which is not just about physical vulnerability, but spiritual and emotional openness. They were fully seen, and still fully safe. This is what it means to belong to one another: not to fit into roles or expectations, but to be received as a gift.

And in those early moments, they also belonged to themselves: no posturing, no pretending, no mask to wear. One of the signs that sin had entered the world was when Adam and Eve put on clothes; they began to feel shame. Before that, they were at peace in their own skin: aligned, whole, unfractured. They lived with integrity, inside and out.

It was a picture of wholeness.

Of course, the story doesn’t end there. As soon as fear and shame enter the scene, the cords of belonging began to fray. Adam and Eve hid from God. They blamed each other. They covered themselves. The bonds that once held them — God, others, self — unraveled.

But the memory of Eden remains. And the promise of the gospel is that through Christ we are invited forward. Not to reclaim a lost innocence, but to receive a new wholeness. A deeper healing. A restored creation. Because this longing we carry is not a flaw. It’s a compass. It remembers something ancient and sacred. And it’s pointing us home.

Despite the brokenness of the world, the path home and to belonging still exists. And the journey begins with a few simple questions.

First, what is the goal? Most of us already know. We may not use theological language, but we know what we’re longing for. We want to be held by a love that doesn’t shift with the seasons. We want real relationships: people who see us, know us, and stay with us. We want to stop pretending. To live with honesty and integrity and grace. To have peace.

Second, how do I get there? The answer isn’t hidden. If we really want to draw closer to God, start with prayer, open the Bible, or take a walk and speak to God like a friend. Want to grow closer to others? Reach out. Tell the truth. Accept help. Be present. Want to know yourself? Make space for silence. Talk to a therapist. Start a journal and write down the truth, even if you can’t yet say it out loud. The practices aren’t mysterious. The challenge usually isn’t knowing what to do, it’s believing it’s worth doing.

And that’s the third question: Is it worth it?

THIS JOURNEY REQUIRES SOMETHING FROM US. IT ASKS FOR VULNERABILITY. HONESTY. COURAGE. IT MEANS

OPENING OLD WOUNDS AND ADMITTING WE’RE TIRED. IT MEANS LETTING GO OF THE POLISHED VERSION OF OURSELVES IN ORDER TO BE KNOWN IN OUR FULLNESS.

That’s where the Church comes in. Not to guilt people into action. Not to shout instructions from a distance. But to walk with us. To help us imagine what’s possible. To say, with our presence and our lives, that healing is real. That wholeness is not a fantasy. That we are not too far gone. That the road home is open and we don’t have to walk it alone.

If the ache of our time is a crisis of belonging, then the Church has never been more urgently needed. Not as a dispenser of answers or as a place of performance. The Church is needed as a living, breathing community that dares to embody the truth that we were made to belong – to God, to others, to ourselves.

We need churches that practice radical hospitality, where no one has to clean up their life to be welcomed, where the messy and the holy sit side by side. We need churches where questions are honored, not silenced. Where leaders go first in telling the truth. Where vulnerability is seen as strength, not weakness. Where grace is the glue that holds us together.

We need churches where prayer is honest. Where Scripture is a window, not a weapon. Where the sacraments are tangible signs that we are loved, we are held, we are home.

That is the work before us. To offer belonging not as a reward for good behavior, but as a reflection of God’s unchanging love. Not as a concept to explain, but as a way of life.

by Danusha Laméris

I’ve been thinking about the way, when you walk down a crowded aisle, people pull in their legs to let you by. Or how strangers still say “bless you” when someone sneezes, a leftover from the Bubonic plague. “Don’t die,” we are saying. And sometimes, when you spill lemons from your grocery bag, someone else will help you pick them up. Mostly, we don’t want to harm each other. We want to be handed our cup of coffee hot, and to say thank you to the person handing it. To smile at them and for them to smile back. For the waitress to call us honey when she sets down the bowl of clam chowder, and for the driver in the red pick-up truck to let us pass. We have so little of each other, now. So far from tribe and fire. Only these brief moments of exchange. What if they are the true dwelling of the holy, these fleeting temples we make together when we say, “Here, have my seat,” “Go ahead — you first,” “I like your hat.”

12 For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. 13 For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit.

24 But God has so composed the body, giving the greater honor to the inferior part, 25 that there may be no discord in the body, but that the members may have the same care for one another. 26 If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together.

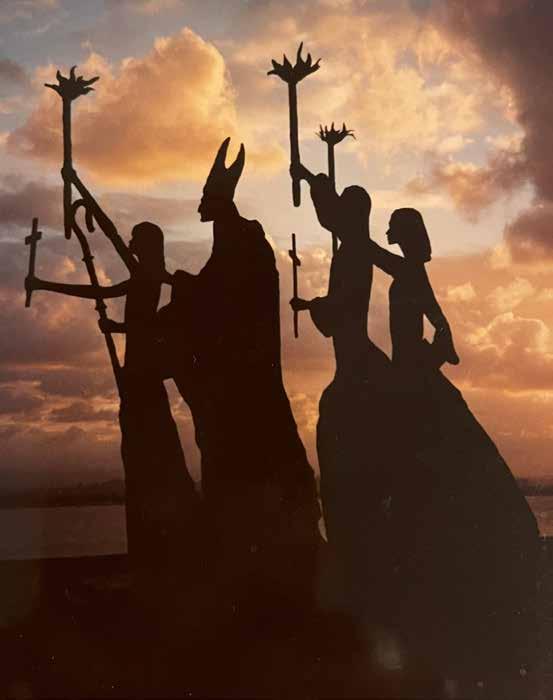

by Matthew Fox

Recently, a successful businesswoman in Oakland who runs a car repair shop told me that my book The Reinvention of Work “is even more needed today than 30 years ago when you wrote it.” She told me she gives the book out to all her employees when she hires them, as it lays out the values for her workplace. The Conclusion chapter of the book, entitled “Work as Sacrament, Sacrament as Work” treats—as does the whole book—the sacredness of our work. The first section of that chapter cites Thomas Aquinas and Bhagavad Gita teachings.

I recognize this amazing sentence as a statement of what Teilhard de Chardin and Brian Swimme, among others, call Cosmogenesis. The whole cosmos, all of creation, is in a constant process of birthing.

As Pére Chenu says, there is a continuous creation. And a continuous incarnation. And humans are integral to both, we are called to contribute to creation and to contribute to the divinizing of the universe. This is our work, this is, as Hildegard puts it, our “service of God.” When she talks about all of nature being a temple and an altar for the service of God—”the sum total of heaven and earth”—i.e. of the universe—she is celebrating our reason for being.

We are here to contribute to the ongoing evolution of the universe and participate in the wonder of it all, which also means discovering more and more about creation, about the ongoing birthing or genesis around us, all 13.8 billion years of it and even all two trillion galaxies of space encircling it.

In Hildegard’s vision, cosmogenesis becomes our common work, our common service to God and to the world.

And it is sacramental, thus the words “temple” and “altar” are spoken of. Our work is the sacrifice, the thing-made-sacred, that is an offering of praise and thanks we put on the altar. It is our thanks for being here, the gift we leave behind when we die.

by Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer

And if it’s true we are alone, we are alone together, the way blades of grass are alone, but exist as a field. Sometimes I feel it, the green fuse that ignites us, the wild thrum that unites us, an inner hum that reminds us of our shared humanity. Just as thirty-five trillion red blood cells join in one body to become one blood. Just as one hundred thirty-six thousand notes make up one symphony. Alone as we are, our small voices weave into the one big conversation. Our actions are essential to the one infinite story of what it is to be alive. When we feel alone, we belong to the grand communion of those who sometimes feel alone— we are the dust, the dust that hopes, a rising of dust, a thrill of dust, the dust that dances in the light with all other dust, the dust that makes the world.

1

by Richard Rohr

Francis sets out on the road, excited because he knows his vocation is to be a contemplative, spending time in nature in solitude and prayer, and to be in active ministry and to preach to people what he’s experienced. Along the way, he sees a tree filled with birds. He approaches the tree and the birds don’t fly away, so he starts talking to them. We have several accounts of this first sermon, which is not to human beings but to animals, to birds. Maybe it’s been romanticized, but the story is that they stayed and listened to him. At the end of the sermon he says, now go off, because I’ve told you who you are.

For the rest of his life, Francis is in relationship with a variety of animals, birds, fish, trees, and flowers. He always tells these creatures, “Do you realize that by your very existence, you are inherently giving glory to God? So just be who you are. Every animal, every created being has a unique thing to do. Each of you, do your thing; and in that doing, you are giving glory to God!” He would take delight in everything doing its thing. This is a mutual mirroring, and I think it allowed him to do his own thing. He realized that just by being Francis, in all his freedom and joy, he also was giving glory to God. He has no trouble being alone because mirrors are everywhere.

The only reason I can talk about Francis’ relationship with nature with some confidence is because it’s honestly what I have experienced on my Lenten retreats in the desert. I know it may sound fanciful, but everything becomes a mirror— whether the shape of rocks or the color. I’d collect a whole pile of rocks by the end of the five weeks because they were always naming something about me, and I didn’t even know what it was. All I’m saying is the whole world comes to life: every kind of cactus, every kind of tree or dead branch, the sunrise, the sunset, the different kinds of birds. I find myself in the middle of a universe of belonging.

[Father Rohr shares an excerpt from a David Whyte poem]

…I want to walk through life amazed and inarticulate with thanks… I want to know when I lean down to the lilies by the water and feel their small and perfect reflection on my face… I want to know what I am and what I am involved with by loving this world as I do… I want to be found by love, … I want to come alive in the holiness of that belonging.

As we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same.

~ Nelson Mandela

Owene Courtney

Laura Jane Pittman

The Rev. Dr. Linda Privitera

The Very Reverend Kate Moorehead Carroll

jaxcathedral.org