Farm Safety

Fire departments training for grain bin accidents

BY KEITH NORMAN For The Jamestown Sun

JAMESTOWN — Fire departments around the state of North Dakota are getting training on how to extricate people who have become trapped in grain stored in a grain bin, according to Paul Bensch, training officer for the Jamestown Rural Fire Department and officer of the North Dakota Firefighter’s Association.

“We go around to different fire departments,” he said. “We have a scenario we work through with those attending.”

Ken Wangen, fire chief for the Carrington (North Dakota) Fire Department and president of the North Dakota Fire Chief’s Association, is also an instructor.

“Every year it goes corner to corner,” he said. “We’ve been using this equipment since 2016.”

The trailer-mounted equipment includes a small replica of a round grain bin about 8 feet in diameter and 8 feet tall. This bin can be filled with about 280 bushels of any variety of grain, Bensch said.

A rescue mannequin nicknamed Randy is inserted into the grain.

Bensch said usually 12 to 15 firefighters attend the classes held at the local fire departments. The training scenario requires the firefighters to select an incident commander and assign duties before five of the trainees put in safety harnesses and enter the bin.

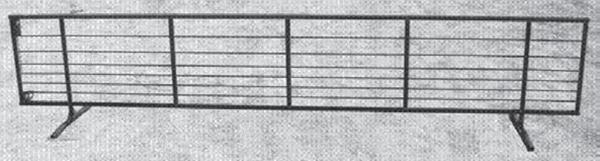

The firefighters are trained to place panels around the trapped person and remove the grain.

Bensch said the training is available to all fire departments in North Dakota and there are grants available for purchasing the panels and other equipment necessary for a grain bin extraction.

“Most departments have been getting the bin panels,” Wangen said. “We tell them it is not if they will have an incident but when.”

However, preventing an accident is preferable to rescue or recovery, he said.

Bensch said there are two common scenarios that lead to someone becoming trapped in a grain bin.

The first involves crusty grain that creates a false surface or bridge with voids below when grain is removed from the bottom of the bin. If the worker steps onto the surface, he or she could fall through and become entrapped in the moving grain being augured out of the bin.

Bensch said hitting the outside of the bin to create vibrations would be the safest method to break the bridge.

Another scenario involves grain adhering to the walls of the bin as the material is removed from the bottom of the bin. If the worker goes into the bin to knock this loose, the worker can become engulfed in an avalanche of grain.

Again, staying out of the bin is the safest way to deal with this problem, Bensch said.

People trapped in flowing grain can be pulled below the surface. The weight of the grain presses against their body, restricting the

Grain bin: PaGE 3

John M. Steiner / The Jamestown Sun

Ken Wangen, fire chief for the Carrington Fire Department and president of the North Dakota Fire Chief's Association, talks about grain bin accidents and the rescue and training involved for fire departments around the state.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 2

chest’s ability to expand during the process of inhaling air.

“It is the same concept as a diver who gets the bends,” Wangen said.

Bensch said he and others are also taking rope training for rescue situations. This includes low-angle rope rescue such as bringing an accident victim up a steep slope of a ditch or hill, and high-angle rescue training such as lowing an accident victim from an elevated structure such as a grain handling leg or elevator.

Bensch and Wangen said they hoped people working in and around grain bins take the proper safety precautions. They also wanted the first responders in the state to be ready if called upon in these situations.

“It is mine and Ken's (Wangen) passion to teach this class,” Bensch said. “It is also one of the most requested classes by the local departments.”

It is also an important service for the rural communities, according to Doug Pierre, deputy state fire marshal for North Dakota.

“Typically, grain bins are in more rural areas and rural firefighters are commonly volunteers,” he said. “It is pretty important for them to get this training.”

And important for workers around grain bins to take the proper precautions.

“On average, about two dozen people are killed in the U.S. each year in grain equipment accidents,” Pierre said. “Using proper safety precautions is better than having an accident.”

John M. Steiner / The Jamestown Sun

A bag of specialty equipment used for rope rescue missions.

John M. Steiner / The Jamestown Sun

Ken Wangen, fire chief for the Carrington Fire Department and president of the North Dakota Fire Chief's Association, stands next to the grain bin rescue training trailer used to train fire department personnel across the state.

Safety around farm equipment requires communications

BY KEITH NORMAN For The Jamestown Sun

JAMESTOWN — The first step to keeping people on the ground safe around farm equipment is simple, according to Angie Johnson, farm and ranch safety coordinator for North Dakota State University Extension.

“It starts with communications,” she said.

Who the communications is with depends on the situation.

If there are adults who are not necessarily familiar with farm equipment, the communications need to be with the equipment operators.

“The equipment operator needs to be aware and alert to their surroundings,” Johnson said. “Do a good job of being open and transparent as to what is going on.”

Johnson said people who visit farms or even walk along roads also have a responsibility.

“Any time you have individuals at the farm or just pedestrians in the area, they need to make sure they wear

“Any time you have individuals at the farm or just pedestrians in the area, they need to make sure they wear high visibility clothing so they can be seen.”

Angie Johnson, farm and ranch safety coordinator, North Dakota State University Extension

Safe This Har vest Season

high visibility clothing so they can be seen,” she said.

Keeping children safe around farm equipment presents some additional safety challenges.

“If you have children on the farm you need to make sure they know the safe areas to play,” Johnson said. “We have agricultural roots here and we want our children to know how it works. We need to help them understand why it isn’t safe to play around farm equipment.”

Johnson said a farmyard can contain as much dangerous equipment as a construction site but rarely do construction workers and their families live at their job site.

“It is not just the equipment,” she said. “It is the haystacks and livestock and a lot of other things around the farm that can be dangerous.”

Even modern equipment can pose hazards for children riding along with the operator.

“We have a lot of concern for children riding in the equipment,” Johnson said. “People should thing long and hard about having kids or adults riding in the buddy or instructor seat furnished on some tractors. They are not designed for children and anybody in the seat should be using a seat belt.”

HAVE A SAFE & SUCCESSFUL HARVEST SEASON!

FARM SAFETY 2024

The pesticides and chemicals that are used on farms can be extremely dangerous. These materials should be kept locked away in marked containers with warning labels.

Safety: PaGe 5

Angie Johnson

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 4

Johnson said the main concern is if the tractor strikes a rock or is jolted in some other manner, the person could be thrown around the cab or even outside the machine if a door latch fails.

“It only takes one time,” she said. “One weird situation for a tragedy."

The biggest concern is the size of the machine. In some cases, equipment is large enough that a child or an adult could be in danger outside the view of the operator. The equipment is also often used under the stresses of a busy harvest or planting season.

“When things get complicated and busy we need to be careful,” Johnson said. “When we are focused on the task at hand we can’t forget being safe.”

That can be difficult for people with a history of working in agriculture.

“It can be really hard for the farm operator,” Johnson said. “We want the kids to be involved in agriculture. We might have friends that want to help or see the process but we all need to be safe.”

Farming is a tradition in many families.

“There is a motto they should remember,” Johnson said. “It is easier to bury a tradition than to bury a child.”

John M. Steiner / The Jamestown Sun

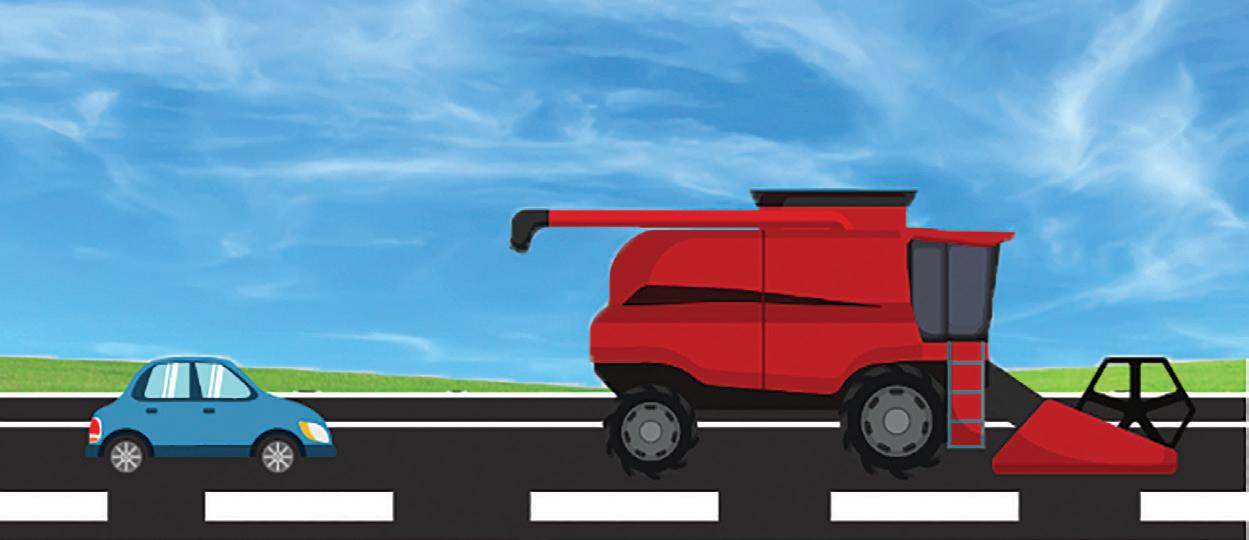

Courtesy the key to equipment safety on the road

BY KEITH NORMAN For The Jamestown Sun

JAMESTOWN — The size of some farm equipment is increasing faster than the size of roads and bridges in the area, according to Chad Kaiser, Stutsman County sheriff.

“Last year we ran into some issues with large (grain) headers crossing some of the rural bridges,” he said. “In one instance, a header hit a guardrail of a bridge and did $36,000 in damage.”

Kaiser said similar incidents at other bridges brought the total damage in Stutsman County to about $50,999 last fall.

Kaiser said the Stutsman County Road Department is not equipped to repair bridge guardrails so all work must be contracted out. The guardrails are part of the inspection process of the bridges so the work must be completed in a timely manner to keep the bridge open to the public.

“They have to be fixed right away,” he said.

The grain header is mounted to the front of the combine and cuts or picks up the grain to feed it into the combine where it is separated from the straw and chaff. Websites for some major farm equipment manufacturers offer the devices in widths of up to 40 feet.

“Most of the time the farmer trailers the header but not all the time,” Kaiser said. “Usually it is only when they are going a short distance between fields.”

When a combine with the header is on the road, it can occupy the entire road, requiring

travelers to pull to the side of the road or to park on an approach until the equipment has passed, Kaiser said.

This can pose particular problems when traveling over hills in the roads.

“Most farms try to warn people when approaching hills,” Kaiser said.

Combines and headers are not the only equipment that can take up most, if not all, of a road, he said.

“When a semi comes onto the road, everyone has to cooperate,” he said. “Move to the side or pull onto the approach.”

Grain carts and other large farm equipment can also require wide turns to move from an approach to the road.

Fall harvest poses some of the greatest risks of public interaction with farm equipment although few problems are reported.

“Everybody is in a rush,” Kaiser said, “but we don’t get a lot of calls. We see the equipment out there because we are out on patrol but not a lot of calls from the public.”

Kaiser noted that North Dakota does not have a minimum speed for traveling on interstate highways, possibly to allow for farm equipment on those roads.

“Most farmers avoid the interstate though,” he said.

While the equipment is getting larger, it is also getting safer with more and better lighting to make travel at dawn or dusk or even at night safer.

“The new equipment has turn signals, break lights and other lights,” Kaiser said. “With older equipment that is not necessarily true.”

Kaiser said the biggest safety factor is still the operators of the farm equipment and drivers they share the road with.

“The motorist and the farm equipment operator need to be cautious and be courteous to each other when out on the highway,” he said.

John M. Steiner / The Jamestown Sun

Sharing the road with trucks and big farm equipment is a major concern on the roadways in rural North Dakota.

Hands-on farm safety lessons

Teens learn communication and more at North Dakota State University Extension Farm Safety Camp

BY JENNY SCHLECHT Agweek

BISMARCK, N.D. — Using tentative hand signals, a teenage boy on the ground directs another teenage boy in the seat of a small red tractor to back up to a tiny hay baler. Progressively, the boy on the ground moves his hands closer together, indicating the distance from the tractor to the baler’s hitch and power take off.

Angie Johnson, North Dakota State University Extension farm and ranch safety coordinator, stands by with a supportive smile, offering occasional instruction or feedback on how the two are working together. Once the tractor is in place, the boys learn to safely hook up and unhook the implement, taking turns connecting points and talking through what they need to do.

The station is one of many that 16 teens from North Dakota, as well as some from as far away as Montana and South Dakota, went through over three days in the last week in June at the final of three NDSU Extension Farm Safety Camps of 2024. The camp, Johnson explains, is “one of a kind throughout the nation” and last year was recognized by the National Association of County Agricultural Agents.

“Our program is really designed to be 100% hands on. So it is complete tractor driving … skid steer driving, ATV driving, getting the chance to actually operate around balers. So they get to learn how to not only just drive

CAMP: PAGE 9

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

NDSU Extension farm and ranch safety coordinator Angie Johnson, left, teaches students at NDSU Extension Farm Safety Camp to hook up a miniature hay baler on June 26, 2024, in Bismarck, North Dakota.

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 7

the mechanics of a tractor, but also engage a PTO — that power takeoff — how to use the hydraulics. So really, taking everything they've learned and applying it and making it real world as to what they would see on the farm,” Johnson said.

This year, the camp was held in three locations over the course of the early summer — Minot, Devils Lake and finally Bismarck. Each camp allowed 16 kids to get their official U.S. Department of Labor tractor certification, as well as knowledge and information in a host of other categories, for a total of 48 kids now more ready to take on life and work on or around the farm.

The camps and the immense effort behind them are in support of a simple goal:

“Every day, we want our farmers and ranchers to come home safe at night,” Johnson said.

Increasing on-farm communication

The National Farm Medicine Center maintains a database of news reports of agricultural injuries and fatalities across the United States. The hard-to-read compilation covers vehicles hitting farm machinery, tractor rollovers, ATV crashes, livestockrelated incidents, grain-bin entrapments and a host of other horrific events that have occurred in the day-to-day routine of agriculture.

“Our profession, agriculture, is the most hazardous industry across all industries, including construction. And so when you think about the equipment we work with, the unpredictable livestock, we just have a lot of hazards,” Johnson said.

For long-tenured Extension agents, the information at Farm Safety Camp is an important step in prevention.

“With my experience of being an agent for 22 years, unfortunately, I've seen the good and the ugly, and I've seen just too many accidents happen in the farming industry that could have been prevented with some basic education,” said Craig Askim,

NDSU ag and natural resources agent for Mercer County.

Many incidents, he said, come down to communication.

“A lot of the accidents that happen is just because the communication between adult and child or boss and child isn't on the same page. So things like runovers and running into things and and running into other equipment or people, I think, are some common things that happen, just because we're not able to communicate, communicate correctly and understand correctly each other,” he said.

That means increasing those communication skills is a big focus for Farm Safety Camp.

"Our goal is to really focus on, how do we communicate, how do we slow down, and how do we teach kids and future farmers and ranchers that the safe thing is always the right thing to do?” Johnson said.

For 15-year-old Molly Wilson of Turtle Lake, North Dakota, using pre-established, standard hand signals when using equipment will be something she takes home from camp.

“The hand signals,” Molly said with a laugh. “Definitely, me and my sister, we, we do our own thing that probably no one else would be able to understand.”

Johnson said getting parents and guardians involved in learning and sharing hand signals is vital. The third day of camp features a parent leadership and action program that gets the parents and kids some practice in communication by having the kids give the guardians hand signals to operate toy pedal tractors through an obstacle course.

“And it is a really good teaching tool, because it allows kids to show their parent or guardian how frustrating it can be to communicate when we don't know what we're asking each other to do. So for example, if we're using the hand signal to come to me or come move forward, if someone else uses a different hand signal, that's when bad

PROGRAM: PAGE 10

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

Each of the 16 campers at Farm Safety Camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, got to make one miniature hay bale on June 26, 2024.

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

Students at Farm Safety Camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, on June 26, 2024, practiced using a skidsteer.

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 9

things can happen and injuries can happen, and so it's a great way to get families on the same page,” Johnson said.

The program also stresses to adults the importance of modeling the safety behaviors they want to see in their children — things like wearing helmets on ATVs or seatbelts in tractors.

“We go through an entire program focusing on communication, proper and really effective role modeling strategies, and also how to have really tough conversations and make sure our kids are ready to do the tasks we're asking them to do,” Johnson said.

And it’s also about not assuming what kids know.

“We have to make sure we're asking questions, seeking to understand, and, ‘Do you know what I'm asking you to do?’ and then having them teach back,” Johnson said.

Better safe than sorry on the farm

For Molly, Farm Safety Camp was about far more than farm safety.

Farm Safety Camp included running large machinery, as well as using pedal tractors and toy equipment as models. These students were learning about parking and safe storage on June 26, 2024, in Bismarck, North Dakota. Program

“We learned a lot about, like, sunscreen and just how important it is, and a lot about skin cancer. We learned location, like county roads and the townships in North Dakota, and, like, how to locate them and tell, if you have to ever, how to tell, like people where you are based on those. And it was really good,” she said.

Molly’s mom, Sarah Bedgar, is the NDSU Extension agent for ag and natural resources in McLean County. She was among the agents working at the Bismarck camp and said the program is as much a rural living survival guide as it is about farm safety. Among the important topics discussed was mental health and suicide prevention, taking the definition of farm safety to all manners of well-being on the farm.

Johnson said the camp brings in county Extension agents as well as volunteer partners like rural electric cooperatives and rural fire departments to “really help kids understand what are those hazards and what tasks can we do safely on the farm?”

Learning how to safely hook up an implement with a PTO was among the lessons covered at NDSU Extension Farm Safety Camp on June 26, 2024, in Bismarck, North Dakota

The camp exposed teens to the big things as well as the little things that can help keep someone from getting hurt. Teedyn Anderson, 13 of Steele, said learning how to get in and out of a tractor properly was one of the big things he’ll take home.

“I've always done that wrong, so I don't want to get hurt doing that or something stupid like that,” he said. “I've always gotten in with three points of contact, but now I've learned that when you get out … you need to have three points of contact when you get out, to not just walk out like you're getting out of a car or something.”

Those little things add up, not just in farm safety but in life.

“Education is a key when it comes to safety,” Askim said. “I don't think we can ever be overeducated in that area. I feel that whatever we can teach to kids to be more safe, not only on the farm, but a lot of this stuff also relates to when they get their own driver's license and when they're transporting ... their younger siblings, or whatever the case may be. In rural North America, we ask our children to be a laborer or a transporter, because our parents have to go in different directions, and we don't have a whole lot of time to do any of that.”

Johnson said the skills taught at Farm Safety Camp are lifelong skills, transferable to any occupation, from learning about confined spaces to lockout-tagout systems.

“Safety is transferable, no matter where you go,” she said.

Askim stressed that the camp isn’t about changing parents’ philosophies or perspectives but about opening the door to education "so everybody can have a clear understanding, and we all can work together and avoid some type of conflict that may come.”

Teedyn can see himself ranching some day and wants to be safer when he’s around PTOs and heavy equipment. He thinks NDSU Farm Safety Camp is an important step for anyone who lives or works in agriculture.

“Being safe is better than being sorry when you're doing stuff, because working around heavy machinery, very bad things can happen if you screw up on something,” he said.

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

Jenny Schlecht / Agweek

Best protection for operators in a rollover

BY UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA MEDICAL CENTER,

CENTRAL STATES CENTER FOR AGRICULTURAL SAFETY AND HEALTH, OMAHA, NEBRASKA

It’s still the deadliest type of injury incident on the farm: tractor rollovers. The best protection for operators in a rollover is a rollover protection system (ROPS).

The PennState Extension “Rollover Protection for Farm Tractor Operators” document notes that recent figures from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) suggest that approximately 20 out of every 100,000 American farmers die on the job every year.

“NIOSH estimates that there are approximately 4.8 million tractors in use on U.S. farms,” the document states. “One-half of them are without rollover protection for the operator. 1 in 7 farmers involved in tractor overturns are permanently disabled and 7 out of 10 farms will go out of business within five years of a tractor overturn fatality.”

ROPS are roll bars or roll cages designed for wheel- and track-type agricultural tractors. They are designed to create a protective zone around the operator when a rollover occurs. In conjunction with a fastened seat belt, ROPS will prevent the operator from being thrown from the protective zone and crushed from an overturning tractor or from equipment mounted on or hitched to the tractor.

Among the key reasons for using a ROPS is that tractor overturns continue to be the leading cause of death on the farm. Additional reasons include:

• The use of ROPS and a seat belt is estimated to be 99% effective in preventing death or serious injury in the event of a tractor rollover.

RolloveRs: PAGe 12

Courtesy / Canva Rollover protection systems can help prevent fatalities on the farm.

• The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires an approved ROPS for all agricultural tractors over 20 horsepower that were manufactured after Oct. 25, 1976, and which are operated by hired employees.

• A ROPS normally limits the degree of rollover, thereby reducing damage to the tractor.

• A ROPS with enclosed cab also prevents tractor operators from being knocked out of their tractor seat from rough ground and low hanging tree limbs, provides protection from the sun and other weather hazards, and reduces risk for the unsafe practice of extra riders on tractors.

• Experienced operators are involved in 90% of all tractor rollovers.

ROPS became optional equipment on most tractor models between 1967 and 1985, meaning new tractor buyers had to add the ROPS cost onto the tractor’s base price. Few cost-conscious farmers added the ROPS as an option. Prior to 1967, even fewer tractors were equipped with ROPS. Today, many tractors manufactured prior to 1967 are still in use and without the protection of a ROPS. It was 1985 when most American tractor manufacturers voluntarily began adding ROPS on all farm tractors over 20 horsepower that were sold in the United States.

Because tractors are often in use for 30 to 40 years after they’re manufactured, the

percentage of tractors in America being used without a ROPS is high. In addition, some farmers claim the ROPS on their tractor hinders their view as they use it, so they have removed the ROPS. Still other farmers find their tractor doesn’t fit a small space unless the ROPS is removed.

ROPS are engineered to mount on specific tractor models are designed to operate with the tractor’s mounting brackets and frame. This creates a structure that is flexible, yet rigid enough to withstand loads produced during a tractor overturn. These must pass engineered, crush, static and dynamic tests set by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) or OSHA to assure adequate performance before they’re produced commercially.

Factory installed ROPS are certified to meet maximum rollover impact and dynamic forces in order to absorb impact energy without excessive deformation to create an operator zone of protection. They may be made of any material that meets temperature requirements and passes the standard test. Typically, installed ROPS are made of steel that will not fracture in cold temperatures and are precision welded. A factory installed ROPS will have a certification label attached to the roll bar starting that the roll bar meets SAE/ASAE/OSHA standards.

Modification of a factory installed ROPS (cutting, grinding, frilling, or welding) is unauthorized and unwise. It can impair the ROPS ability to carry out its function in the event of an overturn.

Three types of ROPS are available for agricultural tractors:

• Two-post ROPS

• Four-post ROPS

• ROPS with an enclosed cab

Two-post ROPS are the most common and are available in either rigid or foldable models. The rigid ROPS has upright posts that are vertical or slightly tilted and mount to the rear axle.

The foldable ROPS was designed with hinges to allow the ROPS to fold to fit low clearance areas.

A four-post ROPS is mounted onto both axles and onto the frame in front of the operator. ROPS with an enclosed cab is typically installed by the manufacturer and the structure acts as a ROPS.

To maintain a ROPS, inspect and service the ROPS and seat belt periodically for extreme rust, cracks, or other signs of wear. Any significant wear could cause a ROPS failure during a rollover.

If signs of wear are observed, the manufacturer or dealer should be consulted to determine a suitable course of action.

Never drill holes into a ROPS or weld a piece of steel onto the frame. If lightning or other light attachments are needed, they should be clamped onto the ROPS. A ROPS should not be used as a point of attachment for a chain, hook,

or cable. Pulling with the ROPS could damage it and result in a rear overturn. If a tractor with a ROPS does overturn, the ROPS should be replaced because it is designed to bend to absorb the overturn energy generated when the tractor contacts the ground. ROPS are only designed and certified to withstand one overturn.

Retrofit ROPS are available. A listing of ROPS for farm tractors manufactured since 1967 is available in “A Guide to Agricultural Tractor Rollover Protection” at https://rops.ca.uky.edu/.

For information about ROPS for some older tractors, visit the National ROPS Rebate Program ( https://www.ropsr4u.com/ ) website.

A homemade ROPS is not recommended because the materials and tools necessary to design one that withstands an overturn are not readily available to the public. A ROPS used without a seat belt will not provide full protection to the operator.

Be aware that a ROPS will not prevent an overturn but can prevent injury to the operator once the overturn occurs. The ROPS and properly worn seat belt provides the most protection in an overturn incident.

Find more details and ROPS resources at https://www.ropsr4u.org/rollover-facts.php .

Funding for this educational article comes from the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health and the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Timely maintenance can prevent round baler fires

“It seems odd to think about the risk of baler fires right now, as the grass is still green in many areas where hay is still being harvested,” says Tom Clays, North Dakota Forest Service director.

Timely baler maintenance is key to prevent dangerous round baler fires.

“A common cause of round baler fires is mechanical issues, primarily problems with roller bearings found within the baler,” says Angie Johnson, North Dakota State University Extension farm and ranch safety coordinator. “The roller bearings inside the round baler can easily become damaged due to wear and extended use. Once the bearings are damaged, they become dangerously hot and can start a fire inside the baler chamber.”

As the haying season shifts into more mature and drier grasses, including the baling of small grain straw, these types of fuels can burn quickly and spread over a large area.

“We have to remember that there is a tremendous amount of friction and static that builds up during baling,” Johnson says. “Add that combination of friction and static electricity or a mechanical failure on the baler, with extremely dry hay, and you have the perfect recipe to start a fire.”

To prevent round baler fires this haying season, Johnson recommends conducting a visual assessment of the baler by walking around the baler when both the baler and tractor are shut off. Performing preventative measures, including daily maintenance when in active use, can help farmers maintain their equipment for peak

performance, reduce repairs and prevent equipment fires.

When assessing the rollers and belts inside the round baler, farmers may need to have the chamber door of the baler open.

“Always make sure the chamber door is in the lock position by manually shifting the lever to the lock position,” says Johnson. “By locking the chamber door open, you prevent the possibility of the chamber door closing on you if the hydraulics of the chamber door fail.”

During the visual assessment of the baler, Johnson recommends farmers consider the following actions:

• Inspect bearings, chains, hoses and belts for wear, and replace worn parts. Some balers use chains or drums rather than belts to create the bale. Take time to inspect.

• Remove excess net wrap and/ or twine pieces that may have accumulated around the rollers.

• Look for purple discoloration on the shields of the baler where the roller bearings are located, as this could be a sign of a “hot spot” on the baler. These hot spots are indicators that the bearing might be wearing out and needs to be replaced.

• Check for belts that may have become loose around the rollers. If a belt becomes too loose, the belt starts slipping on the rollers, causing friction. That friction can allow for dust particles, loose material and the bale developing inside the baler chamber to ignite.

• Lubricate chains, gears and bearings following the recommended lubrication instruction schedule from your baler’s operator manual. The operator’s manual for the baler will provide the best maintenance schedule for your baler.

• Use an air compressor to blow dry matter such as leaves, dust and plant stems off the baler after every 50 to 75 bales.

An infrared heat thermometer is an inexpensive tool ($20 to $40) found at farm and ranch supply stores to help prevent baler fires.

“An infrared heat thermometer is a great tool to help monitor the temperature of your baler’s roller bearings,” Johnson says. “Take the time for a stretch break while baling and use the thermometer to check the temperature of your baler’s roller bearings. If you see a temperature spike with one or more bearings, it is time to stop and get the

bearing replaced before your baler becomes damaged and catches fire.”

Farmers should also carry a fire extinguisher and make sure it is full and working correctly, Johnson says.

“Let others know your plans before going out to bale hay so if you don’t return when you said you would, someone can check to make sure you are OK,” Johnson says. “This also means you should carry a fully charged cellphone with you while baling.”

In the event of a fire, immediately call 911. Firefighters can help contain the fire quickly and lessen the extent of the damage.

“A baler can be replaced. You can’t,” Johnson reminds farmers.

For more farm and ranch safety tips, visit www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/ ag-hub/ag-topics/farm-safety-health.

Proper maintenance can prevent combine fires

Farmers should take steps to minimize the risk of combine fires.

North Dakota State University Extension farm and ranch safety coordinator Angie Johnson urges farmers to use any breaks in harvest for necessary maintenance that can help prevent equipment failures and fires.

“Equipment fires, specifically combine fires, are a serious threat during the harvest season,” Johnson said. “No one wants to lose their combine or the remaining unharvested crop in the field due to fire. The biggest risk, however, is the loss of human life, as combines, crops and other equipment can be replaced — you cannot.”

While performing daily maintenance and making repairs, take time to examine your combine’s electric and hydraulic systems, advises Johnson. Properly route or restrain wires and hoses so they do not rub or get cut by moving parts.

“Hydraulic systems are prone to produce small leaks, and there may be oily residues from repairs,” Johnson said. “Hydraulic oil combined with crop dust provides a ready fuel source that will burn if ignited. It is very common for the fuel source to be crop residue or soybean dust.”

Soybean dust is fine, fluffy material that finds its way to almost all machine parts. A combine that is not thoroughly cleaned periodically will have highly combustible material tucked into numerous places ready to become a fuel source for fire.

“If your combine is on fire, be sure to call your fire department right away,” says Rich Schock, chief of the Kindred Fire Department. “By calling early, before the fire engulfs your combine and spreads further,

we can work towards helping you protect your investment while also keeping you safe and out of harm’s way.”

The dust and chaff produced by harvest crops can be ignited by many sources. Sources include:

• Wore out/damaged bearings

• Engine components, such as the exhaust manifold and turbocharger, which produces exhaust gasses exceeding 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit

• Friction between plant parts rubbing together

• Electrical shorts or arcs

Combine: PAGe 15

Johnson urges farmers to consider the following tips for reducing the risk of combine fires while harvesting crops:

• Pre-operational checks. Take time to walk around the combine before the start of each day during harvest season. Use an air compressor or leaf blower every day when the machine is off and cooled down to remove dirt, dust, chaff and other plant reside that has accumulated. Always wear hearing protection, eye protection and respiratory protection, such as an N95 mask. While blowing off residue look in high-risk areas such as the engine and engine compartments, hydraulic pumps and pump drives, gear boxes, batteries and cables. When cleaning, take time to look for any issues that require repair such as leaking hydraulic hoses that can be a perfect place for chaff to stick and build up, creating an easy fuel source for a fire.

• Take time to service the machine daily based on the combine’s operator manual. Grease and lubricate bearings and chains and continue to look for areas that have excessive wear or damage.

• Watch for wiring issues. Today’s combines are controlled by many

sensors and electrical components that are extremely complex. Take time to glance through wiring systems to see where wires appear to be unrestrained or damaged from rubbing or making contact with moving parts.

• Use an infrared thermometer. Hot bearings are a combustion source. Warm up your combine before taking it to the field and use an infrared thermometer to determine the operating temperature of your combine’s bearings. Safely open the combine’s shields, and from a safe distance, point the infrared thermometer at a bearing to read the measured temperature. If one bearing has a temperature much higher than the others, it may be worn or damaged. Plan to replace the bearing as soon as possible. Infrared thermometers are inexpensive (less than $50) and available at many hardware and farm stores. Another great time to check the temperature of the combine’s bearings is while you are waiting for the truck or grain cart.

• Install an air intake kit. An air intake kit allows clean air found above the combine’s “dust cloud” to enter the combine’s air intake screen, instead of taking in the dusty, dirt-filled air produced from harvesting the crop. Take the time to consider an option that will work best for you and your combine.

• Avoid combining during fire danger conditions. Avoid harvesting when it

is hot and dry. Relative humidity values are low in the fall, increasing the risk of fire, especially in the late afternoon hours when temperatures rise. Limit the harvesting of soybeans that are extremely dry. Soybean moisture can get as low as 8% to 9% on a warm, dry afternoon. Keep an eye on outdoor air temperature and wind speeds. As hard as it is to shut down for the day when conditions are favorable for harvesting, shutting down when temperatures are hot and windy could prevent you from losing your combine to a fire. Be aware and find out if your area is in a fire danger zone by visiting: https://bit.ly/3WGNgAU.

• Carry two, fully charged fire extinguishers. Ideally, you should have two 20-pound ABC fire extinguishers on your combine, one in the cab and one on the outside of the machine near ground level. Have them ready and operational, and review with workers how to use them when needed. Call 911 immediately to get your closest fire department on scene, as fires can escalate quickly.

• Create a soil perimeter. If you choose to harvest during high wind and temperature conditions, make a tillage pass around the perimeter of your field to prevent the possibility of a fire spreading to other areas.

• Strategically park harvest equipment. While harvesting a field, park your semis, trucks, pickups,

tractors, grain carts, etc. in a place with minimal vegetation. Hot exhaust can be emitted from these vehicles and can start a fire in the ditch if dry grass is present. Before parking equipment and machinery in a shed or Quonset for the night, let them cool down first to reduce the risk of a building fire.

“Before going out to combine, let others know your plans and field location,” Johnson says. “If you do not return when you say you will, have someone check to make sure you are OK. This also means you should carry a fully charged cellphone with you while you are combining.”

Dust and fine crop particles are a natural result of combining. Taking time to clear the chaff and dust helps to remove a potential fuel source for combine fires.

“Even though it may feel like you are slowing down your harvest progress by stopping the machine to clean off chaff and dust, it could be the difference between finishing your harvest season or watching it go up in smoke,” says Johnson. “Do the best you can each day to keep your equipment cleaned and maintained. This will protect your investment and yourself from serious injury.”

For more information on crop harvest prevention techniques, visit: ndsu.ag/fireprevention.