Acknowledgments

The most important and heartfelt acknowledgment is to my family. Thank you to my two sons, Colin and Tyler, for accepting some “motherless” weekends and evenings throughout my career, as I traveled and shared my passion for and knowledge of sedation with colleagues worldwide. You have, albeit unknowingly, indirectly supported me not only for this book but also throughout my career: Understanding that sharing sedation experience with others to advance the practice, safety, and knowledge of sedation is my passion and has taken me away from home, even missing on occasion some of your important events. Thank you, Tyler, for sitting beside me in the early morning and late-night hours to read over my shoulder, encouraging and helping me edit and revise chapters. Thank you, Colin, for your efforts in helping me organize the book and come up with new ideas for book chapters. I am so proud of you both and honored to be your mother.

I would like to express my respect, gratitude, and appreciation to Gregory Sutorius, Senior Editor for Clinical Medicine, and Lorraine Coffey, Developmental Editor, at Springer. Thank you both for agreeing to the short deadline from inception of the third edition, to receiving the chapters, editing them, formatting the

ix

book, and presenting it published in 6 short months! Your gentle prodding, attention to detail, kindness, expertise, and professionalism has inspired me to meet all deadlines. Most importantly, you both were committed to this project committed to supporting all efforts to produce Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room as a contribution to the feld.

My fnal acknowledgment is to Ms. Kimberly Manning. From the inception of the 3rd edition of this book to the fnal moments of its galley proof approval, you devoted even the after-hours ensuring that all references, fgures, tables, and source information were accurate, the grammar and typos corrected, the copyrights were obtained, and that everything from the table of contents to the fnal chapter fowed appropriately. You caught mistakes that would have gone unnoticed. I have esteem for your commitment to this edition: your organization, encouragement, tireless enthusiasm, and sleuthing skills to uncover important contributions to this book were invaluable. I will always be appreciative.

x

Acknowledgments

1 The History of Sedation

Robert S. Holzman

2 Sedation Policies, Recommendations, and Guidelines Across the Specialties and Continents

3 Procedural Sedation: Let’s Review the Basics

Vincent W. Chiang and M. Saif Siddiqui

4 Pre-sedation Assessment

Timothy Horeczko and Mohamed Mahmoud

5 Sedation Scales and Discharge Criteria: How Do They Differ? Which One to Choose? Do They Really Apply to Sedation?

Dean B. Andropoulos

6 Physiological Monitoring for Procedural Sedation

Cyril Sahyoun and Baruch S. Krauss

7 Neuromonitoring and Sedation; Is There a Role?

Neena Seth

8 The Pediatric Airway: Anatomy, Challenges, and Solutions

Lynne R. Ferrari

9 Pediatric Physiology: How Does It Differ from Adults?

Dean B. Andropoulos

10 Capnography: The Science, Logistics, Applications, and Limitations for Procedural Sedation

Bhavani Shankar Kodali

11 Clinical Pharmacology of Sedatives, Reversal Agents, and Adjuncts

Randy P. Prescilla

12 The Pharmacology, Physiology and Clinical Application in Dentistry of Nitrous Oxide

Dimitris Emmanouil

13 Sedation of the Obese Child: Essential Considerations 211 Tom G. Hansen and Thomas Engelhardt

14 Sedation; Is it Sleep, Is it Amnesia, What’s the Difference?

Robert A. Veselis and Vittoria Arslan-Carlon

xi

Part I Pediatric Sedation Outside the Operating Room

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

.

Joseph P. Cravero

41

49

83

95

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

141

155

171

199

223

Contents

15 Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics in the Pediatric Population 247

Brian J. Anderson

16 Billing and Reimbursement for Sedation Services in the United States 273 Devona J. Slater

Part II Sedation Models Delivered by Different Specialties: A Global Voyage

17 The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Service: Models, Protocols, and Challenges 285 Douglas W. Carlson and Suzanne S. Mendez

18 Sedation in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: International Practice 305 Karel Allegaert and John van den Anker

19 Sedation in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: Challenges, Outcomes, and Future Strategies in the United States 345 Pradip Kamat and Joseph D. Tobias

20 Sedation in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: Current Practice in Europe 373 Stephen D. Playfor and Ian A. Jenkins

21 Sedation for Pediatric Gastrointestinal Procedures 397 Jenifer R. Lightdale

22 Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Complex and Multifactorial Challenge 413

Robert M. Kennedy

23 Sedation for Radiological Procedures

Amber P. Rogers

24 Sedation of Pediatric Patients for Dental Procedures: The USA, European, and South American Experience

Stephen Wilson, Luciane Rezende Costa, and Marie Therese Hosey

25 Sedation Strategies and Techniques for Painful Dental Procedures

475

497

533 James W. Tom

26 Special Considerations During Sedation of the Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder

John W. Berkenbosch, Thuc-Quyen Nguyen, Dimitris Emmanouil, and Antonio Y. Hardan

27 Pediatric Sedation: The European Experience and Approach

Piet L. J. M. Leroy and Grant M. Stuart

545

561

28 Pediatric Sedation in South America 587 Pablo Osvaldo Sepúlveda and Paulo Sérgio Sucasas da Costa

29 Paediatric Sedation: The Asian Approach—Current State of Sedation in China 601 Vivian Man Ying Yuen, Bi-Lian Li, Bin Xue, Ying Xu, Jacqueline Cheuk Kwun Tse, and Rowena Sau Man Lee

30 Pediatric Sedation: The Approach in Australia and New Zealand 615

Franz E. Babl, Ian McKenzie, and Stuart R. Dalziel

31 Pediatric Sedation in the Underdeveloped Third World: An African Perspective 633

James A. Roelofse, Graeme S. Wilson, and Cherese Lapere

xii

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

.

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contents

Part III Safety in Sedation

32 Pediatric Sedatives and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Challenges, Limitations, and Drugs in Development

Lisa L. Bollinger and Lynne P. Yao

33 Apoptosis and Neurocognitive Effects of Intravenous Anesthetics .

Sulpicio G. Soriano and Laszlo Vutskits

34 Adverse Events: Risk Factors, Predictors, and Outcomes .

Kevin G. Couloures and James H. Hertzog

35 Fasting Status, Aspiration Risk, and Sedation Outcomes

Maala Bhatt

36 Outcomes of Procedural Sedation: What Are the Benchmarks?

Mark G. Roback

37 Medicolegal Risks and Outcomes of Sedation

Steven M. Selbst and Stewart L. Cohen

38 Improving the Safety of Pediatric Sedation: Human Error, Technology, and Clinical Microsystems

Craig S. Webster, Brian J. Anderson, Michael J. Stabile, Simon Mitchell, Richard Harris, and Alan F. Merry

Part IV Sedation into the Twenty-Second Century

39 Intravenous Infusions for Sedation: Rationale, State of the Art, and Future Trends

Anthony R. Absalom

40 Usage of Nonpharmacological Complementary and Integrative Medicine in Pediatric Sedation

Yuan-Chi Lin

41 Towards Integrated Procedural Comfort Care: Redefining and Expanding “Non-pharmacology”

Cyril Sahyoun, Giorgio Cozzi, Piet L. J. M. Leroy, and Egidio Barbi

42 The Role of Simulation in Safety and Training

James J. Fehr, Itai M. Pessach, and David A. Young

43 Criminal Homicide Versus Medical Malpractice: Lessons from the Michael Jackson Case and Others

Gail A. Van Norman and Joel S. Rosen

44 Considerations for the Intersection of Sedation and Marijuana

Brian E. McGeeney and Rachael Rzasa Lynn

45 Proportionate Sedation in Pediatric Palliative Care .

Jason Reynolds

46 Ethical and Clinical Aspects of Palliative Sedation in the Terminally Ill Child

Gail A. Van Norman

47 Future of Pediatric Sedation

James R. Miner

xiii

647

. . . . . . . . . . . 657

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 665

.

681

695

707

721

755

773

783

797

813

827

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 835

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 847

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 863

Epilogue 881 Index 889 Contents

Contributors

Anthony R. Absalom, MD, MB, ChB Department of Anesthesiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands

Karel Allegaert, MD, PhD Department of Development and Regeneration, and Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Leuven, Belgium

Department of Hospital Pharmacy, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Department of Development and Regeneration, KU Leuven, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Leuven, Belgium

Brian J. Anderson, PhD Department of Anaesthesiology, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Dean B. Andropoulos, MD, MHCM Department of Anesthesiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

John van den Anker, MD, PhD Department of Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Physiology, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA

Intensive Care, Erasmus Medical Center-Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Department of Pediatric Pharmacology, University Children’s Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Vittoria Arslan-Carlon, MD Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

Franz E. Babl, MD, MPH Emergency Department, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Egidio Barbi, MD Department of Pediatrics, Institute for Maternal and Child Health – IRCCS ‘Burlo Garofolo’, Department of Medicine, Surgery and Health Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy

John W. Berkenbosch, MD, FAAP, FCCM Pediatrics/Pediatric Critical Care, University of Louisville, Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville, KY, USA

Maala Bhatt, MD, MSc Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Lisa L. Bollinger, MD Global Patient Safety and Pediatrics, Global Regulatory Affairs and Safety, Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

Douglas W. Carlson, MD Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Springfeld, IL, USA

xv

Vincent W. Chiang, MD Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Stewart L. Cohen, Esq Law Offces of Cohen, Placitella & Roth, P.C, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Luciane Rezende Costa, DDS, MS, PhD Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Universidade Federal de Goias, Goiania, Brazil

Kevin G. Couloures, DO, MPH Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University/Lucille Packard Hospital for Children, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Stanford School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Giorgio Cozzi, MD Emergency Department, Institute for Maternal and Child Health IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste, Italy

Joseph P. Cravero, MD Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Stuart R. Dalziel, MBChB, FRACP, PhD Departments of Surgery and Paediatrics, Child and Youth Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Children’s Emergency Department, Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland District Health Board, Auckland, New Zealand

Dimitris Emmanouil, DDS, MS, PhD Department of Pediatric Dentistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Thomas Engelhardt, MD, PhD, FRCA Department of Anesthesia, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, QC, Canada

James J. Fehr, MD Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Palo Alto, CA, USA

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Lynne R. Ferrari, MD Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Tom G. Hansen, MD, PhD Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care: Pediatrics, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark

Department of Clinical Research: Anesthesiology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Antonio Y. Hardan, MD Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Autism and Developmental Disorders Clinic, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Richard Harris, BMBS, D. Univ Specialist Anaesthetic Services, Adelaide, SA, Australia

James H. Hertzog, MD Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, USA

Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Robert S. Holzman, MD, MA (Hon.), FAAP Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Timothy Horeczko, MD, MSCR Department of Emergency Medicine, Harbor—UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA

Marie Therese Hosey, BDS, MSc Department of Paediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Oral and Craniofacial Sciences, King’s College London, London, UK

xvi

Contributors

Ian A. Jenkins, MBBS Department of Pediatric Intensive Care and Anesthesiology, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol, UK

Pradip Kamat, MD, MBA, FCCM Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, USA

Robert M. Kennedy, MD Department of Pediatrics, Division of Emergency Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

Bhavani Shankar Kodali, MD University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Baruch S. Krauss, MD, Ed.M. Division of Emergency Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Cherese Lapere, MBChB, DipPEC, DA(SA), PDD Department of Anaesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Groote Schuur Hospital, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Rowena Sau Man Lee, MBBS, FHKCA Department of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong, China

Piet L. J. M. Leroy, MSc, MD, PhD Pediatric Procedural Sedation Unit, Division of Pediatric Critical Care, Department of Pediatrics, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Bi-Lian Li, MD Department of Anesthesiology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Jenifer R. Lightdale, MD, MPH Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Pediatrics, UMass Memorial Children’s Medical Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA

Yuan-Chi Lin, MD, MPH Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Rachael Rzasa Lynn, MD Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Hospital Pain Management Clinic, Aurora, CO, USA

Mohamed Mahmoud, MD Department of Anesthesia, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Brian E. McGeeney, MD, MPH, MBA Division of Headache Medicine, Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, JR Graham Headache Clinic, Boston, MA, USA

Ian McKenzie, MBBS, FANZCA Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Suzanne S. Mendez, MD Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, St. Charles Medical Center, Bend, OR, USA

Alan F. Merry, FANZCA, FPMAN Department of Anaesthesiology, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand

James R. Miner, MD Department of Emergency Medicine, Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN, USA

xvii

Contributors

Simon Mitchell, MBChB, PhD Department of Anaesthesiology, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Thuc-Quyen Nguyen, MD Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Itai M. Pessach, MD, PhD, MHA The Edmond and Lily Safra Children's Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel

The Sacler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Stephen D. Playfor, MBBS Department of Pediatric Critical Care, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester, UK

Randy P. Prescilla, MD Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Jason Reynolds, MD Pediatric Palliative Care, Cook Children’s Medical Center, Fort Worth, TX, USA

Mark G. Roback, MD Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO, USA

James A. Roelofse, MBChB, MMed, PhD Department of Anesthesiology, University of Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

University College London, London, UK

Amber P. Rogers, MD, FAAP Departments of Pediatrics and Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Departments of Pediatrics and Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Joel S. Rosen, Esquire Cohen, Placitella & Roth, P.C., Philadelphia, PA, USA

Cyril Sahyoun, MD Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Geneva, Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève, Geneva, Switzerland

Steven M. Selbst, MD Department of Pediatrics, Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children and Sidney, Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Wilmington, DE, USA

Neena Seth, FRCA Evelina London Children’s Hospital, Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

M. Saif Siddiqui, MD Division of Pediatric Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR, USA Department of Anesthesiology, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR, USA

Devona J. Slater, CHA, CHC, CMCP Auditing for Compliance and Education, Inc. (ACE), Overland Park, KS, USA

Sulpicio G. Soriano, MD Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Michael J. Stabile, MD, MBA Department of Anesthesia, Centennial Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

St. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

xviii

Contributors

Grant M. Stuart, MBChB, DCh, DA, FRCA Department of Anaesthestics, Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Trust, London, UK

Paulo Sérgio Sucasas da Costa, MS, PhD Federal University of Goias, Goiânia, Brazil

The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Joseph D. Tobias, MD Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

James W. Tom, DDS, MS, DADBA University of Southern California, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Jacqueline Cheuk Kwun Tse, MBBS, FHKCA Department of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong, China

Gail A. Van Norman, MD University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Biomedical Ethics, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

Robert A. Veselis, MD Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Memorial

Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

Pablo Osvaldo Sepúlveda, Dr. Med. Hospital Base San Jose, Osorno, Chile

Laszlo Vutskits, MD, PhD Department of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology and Intensive Care, University Hospital of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Craig S. Webster, BSc, MSc, PhD Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Graeme S. Wilson, MBChB, FCA(SA) University of Cape Town, Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, Rondebosch, Western Cape, South Africa

Stephen Wilson, DMD, MA, PhD Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

Blue Cloud Pediatric Surgery Centers, Glen Rock, PA, USA

Bin Xue, MD Department of Anaesthesiology, Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Ying Xu, PhD, MD Department of Anaesthesiology, Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

Lynne P. Yao, MD Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, Offce of New Drugs, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

David A. Young, MD, MEd, MBA, FASA, CHSE Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Vivian Man Ying Yuen, MD, FANCZA, FHKCA Department of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, Hong Kong, China

xix

Contributors

The History of Sedation

Robert S. Holzman

Introduction

The history of induced altered states as a means of tolerating the intolerable is as old as man and for eons has been alternately welcomed, worshipped, and vilifed [1]. Ironically, as in ancient times, these three attitudes often coexist [2–4].

Is the history of sedation different from the history of anesthesia? They were and often continue to be inseparable, particularly for children,1 so we will focus on the various modalities and practices over time, emphasizing the differences but remaining in awe of the similarities through the ages.

Most children in Ancient Egypt did not go to school. Instead boys learned farming or other trades from their fathers, and girls learned sewing, cooking, and other skills from their mothers. Some girls were also taught to read and write. Boys from wealthy families sometimes learned to be scribes. In Greece when a child was born, it was not regarded as a person until it was 5 days old when a special ceremony was held, and the child became part of the family. Parents were entitled, by law, to abandon newborn babies to die of exposure. Sometimes strangers would adopt abandoned babies. However, in that case, the baby became a slave. In Sparta children were treated very harshly. At the age of 7, boys were removed from their families and sent to live in barracks and treated severely to turn them into brave soldiers. They were deliberately kept short of food so they would have to steal – teaching them stealth and cunning. Spartan girls learned athletics and dancing – so they would

1 The Committee on Drugs of the American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that “the state and risks of deep sedation may be indistinguishable from those of general anesthesia.”2 The American Dental Association Council on Education defnes general anesthesia to include deep sedation.3 The minimal distinction between deep sedation and general anesthesia has been recognized by the current author as well.4

R. S. Holzman (*)

Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

e-mail: robert.holzman@childrens.harvard.edu

© Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

become ft and healthy mothers of more soldiers. Many of the inhabitants of Rome were slaves. Prisoners of war were made slaves, and any children slaves had were automatically slaves. The sons and daughters of well-to-do Romans went to a primary school called a ludus2 at the age of 7 to learn to read and write and do simple arithmetic. Girls left at the age of 12 or 13, and only boys went to secondary school where they would learn geometry, history, literature, and oratory (the art of public speaking).

Infanticide was common and was a parent’s right if they didn’t want a child. The Spartans, for example, checked newborn infants for physical deformities and “mental” problems; if an abnormality was discovered, the child was tossed off a cliff. It was the state, not the father as in other Greek citystates, who determined whether a newborn male should live or die. Sparta was a military state and needed a good supply of robust babies.

The diffculty with evaluating even relatively recent historical attitudes toward children is the paucity of documentation; this is particularly true with medical care. The common notion, introduced as a historical truth by Aries, was that children “were simply adults in miniature” [5]. Representations of children in medieval artwork depict them in adult clothing (Fig. 1.1). If they wore grown-up clothes, the theory goes, they must have been expected to behave like grown-ups. Similarly, literature rarely touched on the childhood years of its characters. The medical profession left nurses and mothers to deal with children. After all, because infants and small children were unable to speak and report their complaints, how could a learned doctor be expected to bother with them?

These ideas, proposed with a dearth of primary evidence, likely devalued the love that ancient and medieval parents

2 The same name applied to the school for gladiator training.

K. P. Mason (ed.), Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58406-1_1

3

1

degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents). Florence, Italy. Commissioned in 1419; opened in 1445. Glazed blue terracotta medallions are mounted between the arches with reliefs of babies designed by Andrea della Robbia suggesting the function of the building. The insignia of the American Academy of Pediatrics is based on one of the medallions

had for their children. While there certainly isn’t a great deal of medieval artwork that depicted children, the examples that survive do not universally display them in adult garb. Additionally, medieval laws existed to protect the rights of orphans. By the turn of the thirteenth century, English law recognized the dependency of the young and spoke of the needs they had for protection and support, especially around the time of the Black Death (1848–1850). In Bristol, as in London, offcials made the guardianship of orphans a matter of public concern in order to protect inheritances. However, neither London nor Bristol protected the orphans of the poor and the propertyless. For example, in medieval London, the Orphan Court would place an orphaned child with someone who could not beneft from his or her death, and in this, the mayor had jurisdiction over the child’s fnancial and property assets. In keeping with the times, medieval medicine approached the treatment of children separately from adults. In general, children were recognized as vulnerable and in need of special protection. Early death, however, was an unfortunate but frequent event.

Nonetheless, before the eighteenth century, few groups were more ignored medically than children. Death rates were high for a variety of reasons, mainly because of infectious diseases, but poor maternal care and prematurity led to diffculty caring for sick young babies. Nor was this restricted to the poor. Queen Anne, who ruled England from 1702 to 1714, had four miscarriages between 1684

and 1688, and not a single one of her 18 children survived to maturity. Such childhood mortality was considered natural, and parents viewed – and were encouraged to view –the loss of 75% of their infants before the age of 2 as a normal condition. Moreover, most doctors were not alarmed by the heavy death toll for babies, since they believed children to be outside of their scope of practice. When children received any treatment at all, they were drugged and bled just like their elders, because they were considered grownups in miniature.

A growing humanitarian movement in the eighteenth century made the medical profession aware of its obligation to the underprivileged, including children. Thomas Coram (1668–1751), a bachelor, pitied the many babies abandoned on the highways leading to London. In 1739 he helped to found London’s Foundling Hospital. Though not a hospital in the modern sense, this child shelter drew generous aid from the medical profession and served to focus attention on proper childcare [6]. The frst foundling hospital was established a millennium earlier by the archpriest of Milan in 787, although perhaps the most well-known of the foundling hospitals was the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Fig. 1.2).

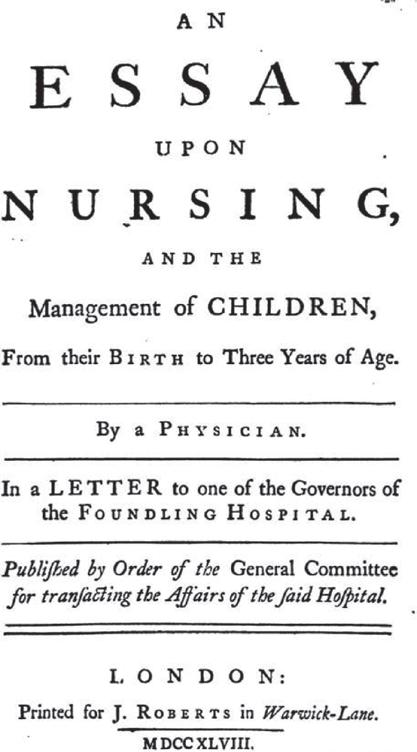

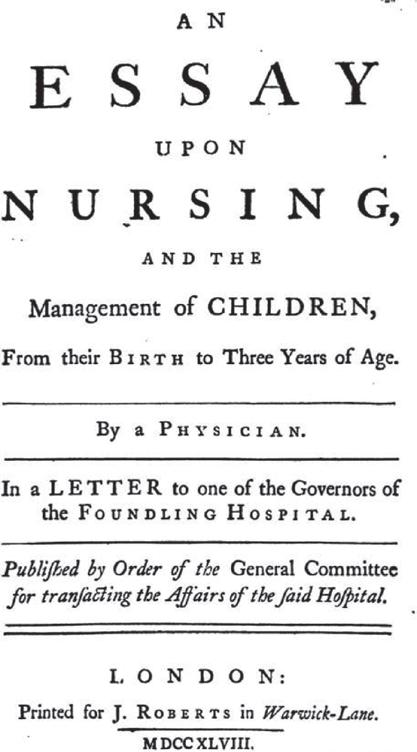

The most eloquent of the emerging pioneer “pediatricians” during the 1740’s educators was Dr. William Cadogan of London. He told mothers it was dangerous to swaddle babies tightly (in contrast to the swaddling portrayed in the medallions illustrated above), and his Essay Upon Nursing (1748) harshly criticized feeding infants an “unwholesome mess” (often, table scraps) (Fig. 1.3). Many mothers, he observed, were not nursing their babies “for fear of getting fat.” He also advocated frequent diaper changes (a source of disease) and gave infants a “right to kick” [7].

4

Fig. 1.1 Children were “simply adults in miniature”

Fig. 1.2 Ospedale

R. S. Holzman

There is a general perception that in the Middle Ages, children were not valued by their families or by society as a whole. On the other hand, it is important to remember that classical as well as medieval society was primarily an agrarian one. The family unit made the agrarian economy work. From an economic standpoint, nothing was more valuable to the working family than sons to help with the plowing and daughters to help with the household. To have children was, essentially, one of the primary reasons to marry. However, this hardly justifes a general perception of society’s indifference to childhood. Specifc examples can be found, within the broad swath of cultural contexts over millenia, of kindness and progressively enlightened attitudes to childhood medical care. In the face of these facts, it is diffcult to argue that people of ancient and medieval times were any less aware that children were their future than people are aware today that children are the future of the modern world. As a historical volte-face, it is intriguing to contemplate whether future history may reveal over-sentimentalization of children in our modern society.

Inebriation, Intoxication, Hallucination, and Anesthesia

A Forme Fruste of the Sedation Continuum

Alcohol is a fermentation product of many fruits and cereals, and its water solubility makes it a rapidly effective analgesic via glutamate inhibition and soporifc via gammaaminobutyric acid activation. Winemaking was frst practiced in the Middle East about 6000–8000 years ago and was already well established in ancient Egypt. Although wine production was not well-developed in ancient Greece, wine was imported from other countries and often used for medicinal purposes. Beneftting from the breadth of their empire and diverse oenology exposure, the Romans developed the art of winemaking.

Winemaking was ubiquitous in the ancient world – the Moors prepared date wines, the Japanese rice wines, the Indians (Mexico) made pulque from agave, the Vikings fermented honey to make mead , and the Incas made chi -

5

a b

1 The History of Sedation

Fig. 1.3 Dr. William Cadogan, London pediatrician before the word “pediatrics.” Also illustrated is the title page of his Essay Upon Nursing and the Management of Children

cha from maize. Modern beer making (yeast –Saccharomyces cerevisiae ) probably had its origin in Babylon as long ago as 5000–6000 bce . The addition of hops is a much more recent modifcation. Beer drinking and drunkenness were common in ancient Egyptian life; the Greeks learned their brewing skills from the Egyptians. Britons and Hiberni 3 drank courni made from fermented barley.

Wine remained an inebriant and intoxicant, however, until distillation technology was developed in the tenth century. Distillation exploits the fact that alcohol has a lower boiling point than water and therefore can be boiled out of an aqueous solution and condensed, approaching (but never achieving) purity—although 95% by volume is achievable. Liquors (such as rum or whisky) involve fermentation of sugarcane or barley, respectively. Liqueurs are usually produced by steeping fruits and/or herbs in brandy or vodka, with subsequent filtration to remove the vegetable residues. In this regard, absinthe , prepared from wormwood ( Artemisia absinthium , A. maritime , or A. pontica ), anise ( Pimpinella anisum ), and fennel ( Foeniculum vulgare ), plus nutmeg, juniper, and various other herbals, added to 85% alcohol, is then filtered and diluted to 75% alcohol by volume. Wormwood was the most important ingredient because of its psychotropic properties, recognized by ancient and medieval herbalists (Georg Ebers, Hippocrates, Dioscorides, John Gerard).

The dose response of alcohol is interesting as a proxy for the continuum of sedation and general anesthesia. Mild intoxication occurs with a blood concentration of 30–50 mg/ dL (0.03–0.05%), and mild euphoria is achieved. Once the concentration has reached 100 mg/dL (0.10%), more serious neurological disturbances result in slurred speech and a staggering gait. At concentrations of 200 mg/dL (0.20%), vision and movement are impaired. Coma results at twice that concentration.

Ancient History

Much of what we know in the twenty-frst century about attempts to provide analgesia and sleep is derived from the written records of ancient civilizations in widely separated areas: China, India, Sumeria, and Egypt, for example. The recorded knowledge began approximately in the fourth millennium BCE, codifying oral drug lore that had undoubtedly preceded such codifcation by centuries. In rough chronological order of the records (but not by the use of the drugs themselves), we can begin with China.

Chinese Drug Lore

R. S. Holzman

3 Hibernia is the Latin name for Ireland; its people were the Hiberni

The Pen Tsao (the symbols of which represent the compilation of medicinal herbs)4 was said to have been authored by Emperor Shen-nung in approximately 2700 bce. As the father of agriculture (the “Divine Husbandman”), he was said to have tasted all herbs in order to become familiar with their usefulness. Likewise, the Nei Ching was said to have been written by Emperor Hant-Ti (about 2700 bce). Although these texts describe the effects of naturally occurring herbs, the preparation of medicinals from herbs was attributed to I-Yin, a prime minister of the Shang dynasty (1767–1123 bce). The details of these preparations were recorded by making knots in strings, arranged vertically on a narrow bamboo surface. The ideograms utilized were uncannily similar to those chosen by Egyptian physicians in their hieroglyphs.5 As recording transitioned from string knots on bamboo to pen and paper, clinical cases and treatment recommendations were more easily recorded, initially by Chang Chung-Ching and the surgeon Hua Tuo (c. 140–208), who probably used Cannabis indica (mafeisan6) for anesthesia (Fig. 1.4). This was probably no accident, as there is ample suggestion that Hua Tuo may have developed many of his medical ideas from Ayurvedic practices in an area of China richly infuenced by Buddhist missionaries [8].

Hindu Drugs

Brahman priests and scholars were the medical leaders in the earliest recorded histories, three of which are of foundational importance in Ayurvedic medicine:

• Charaka Samhita (Compendium of Charaka) (secondcentury CE but copied from an earlier work)

• Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta’s Compendium) (ffthcentury CE)

• Vagbhata (seventh-century CE)

The Susruta detailed more than 700 medicinal plants, the most common of which were condiments such as sugar, cinnamon, pepper, and various other spices. Included among

4 ben (pen; 本 “root”) and cao (tsao; 草 “herb”).

5 The ideogram for “physician” (pronounced i) contained an arrow or a lancet in the upper half and a drug—or bleeding glass—in the lower half.

6 The name mafeisan combines ma (“cannabis; hemp; numbed”), fei (“boiling; bubbling”), and san (“break up; scatter; medicine in powder form”). Ma can mean “cannabis, hemp” and “numbed, tingling.” Other historians have postulated that mandrake or datura was used rather than cannabis, along with the wine. Still others have suggested hashish (bhang) or opium.

6

Sumerian Drugs

Agriculture developed in the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (present-day Iraq), and a sophisticated cultivation of plant materials useful for the alleviation of symptomatic disease was not only practiced but also recorded. Nearly 30,000 clay tablets from the era of Ashurbanipal of Assyria (568–626 bce) were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century near the site of Nineveh, capital of the neo-Assyrian Empire, with numerous references to plant remedies. Beers were especially well-developed in ancient Babylon. C. indica was known for producing intoxication, ecstasy, and hallucinations, especially when reinforced with hemp. This was all under the supervision of the priesthood. In addition, hallucinogenic mushrooms were employed in ancient Sumeria. Poppies were used mainly as a condiment in Sumerian life. Although there is no drug activity in the poppy leaves, fruit, or root, if the unripe seed capsule is opened, the white juice resulting from that is (raw) opium, the “latex” of which forms alkaloids as it dries. However, opium was not described (as far as we know) in the Ashurbanipal tablets.

Jewish Medicine

Tuo’s surgical and medicinal abilities as well as his use of moxibustion

them were descriptions of the depressant effects of Hyoscyamus (a source of scopolamine) and Cannabis indica The eponymously named text (Susruta, c. 700–600 bce) described Susruta’s use of wine to the point of inebriation as well as fumitory cannabis in preparation for surgical procedures. Part of the diffculty with so many drugs was that they were not well codifed and were prescribed in casual ways by numerous practitioners, who relied on (clinical) observation of effects [9].

Jewish medicine received signifcant contributions from the Babylonians during the Babylonian captivity (597–538 bce) as well as from the Egyptians during the Egyptian captivity (a date which is much less clear, based on 430 years of captivity prior to the Exodus, accepted as 1313 bce in rabbinic literature) [10]. Later Jewish medicine adopted Greek and Greco-Roman medical practices. Jewish potions were also prepared by the priesthood, the custodians of public health, for pain relief and the imparting of sleep during surgical procedures, venesection, and leeching. Rather than viewing sickness as divine retribution and its treatment ambivalent, physicians were regarded as the instrument through whom God could effect a cure. Jewish physicians therefore considered their vocation, whether curing illness or treating pain and suffering, as spiritually endowed. The use of opium as an analgesic and hypnotic drug was known, and warning was given against overdosing. “Sleeping dugs” (Samme de shinda) were probably hemp potions, but probably not opium derivatives [11].

Egyptian Medicine

The major infuence on the emerging Greek world of medicine came from Egypt. Our knowledge of their codifcation is relatively robust because of the medical papyri, most of which were hieratic (hieroglyphics or ideographs), compiled from around 2000–1200 bce (Table 1.1). These documents

7

1 The History of Sedation

Fig. 1.4 Hua Tuo (c. 140–208 ce). The ancient texts Records of the Three Kingdoms and Book of the Later Han record Hua as the frst person in China to use anesthesia during surgery, referring specifcally to mafeisan. The illustration portrays Hua

Table

1.1 List of Egyptian medical records

Document Date Comment

Kahun Papyrus 1900 bce Primarily veterinary medicine

Edwin Smith Papyrus 1600 bce Consists of 48 case histories; a well-organized surgical text

Ebers Medical Papyrus 1550 bce Deals with medical rather than surgical conditions; emphasizes recipes

Hearst Medical Papyrus 1550 bce Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary

The Erman Document 1550 bce Deals largely with childbirth and diseases of children

The London Papyrus 1350 bce Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary

The Berlin Papyrus 1350 bce Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary

The Chester Beatty Papyrus 1200 bce Formulary for anal diseases; one case report

S. Holzman

were probably copied from older originals, as evidenced by the use of archaic terminology within the medical papyri, more characteristic of language from around 3000 bce.

It is ironic, and somewhat puzzling, that despite the richness of ancient documentation from these artifacts, there is a paucity of information about narcotics and sedatives in ancient Egypt. Most of the suggestions about the use of such medications are by inference. For example, Ebers 782 cites shepnen of shepen (poppy seeds of poppy) to settle crying children. Interestingly, the poppy seed contains relatively little morphine; it is the latex produced from the incision of the seed pod that actually contains the active ingredient. Another suggestion, by inference, is that base-ring juglets were used to import opium from Cyprus in about 1500 bce, because of the resemblance of these juglets, when inverted, to a poppy head (Fig. 1.5) and the reported fnding of mor-

of the capsule, but the faring angle is almost identical. Overall, the outline of the body of the juglet almost parallels that of the poppy head, and its tall slender neck corresponds to the poppy’s thin stalk

8

Fig. 1.5 Comparison of an opium poppy capsule and a base-ring juglet. An inverted opium poppy capsule on the left and a base-ring juglet from the Bronze Age (dated to Egypt’s 18th dynasty). Note that the solid pottery base ring takes the place of the serrated upper portion

R.

phine in an Egyptian juglet from the tomb of Kha (nineteenth dynasty), although this has been disputed [12, 13]. Cannabis (C. sativa) was prescribed by the mouth, rectum, and vagina and delivered transdermally and by fumigation, yet central nervous system effects were not described. The London and Ebers papyri refer to mantraguru, an obvious common origin with mandrake or Mandragora. Some species of lotus (Nymphaea caerulea and N. lotus) are native to Egypt and contain several narcotic alkaloids that can be extracted in alcohol, leading to a logical hypothesis that lotus-containing wine might have additional narcotic effects. Ebers 209 and 479 both refer to preparations for the relief of right-sided abdominal pain and jaundice (respectively) containing lotus fower as an ingredient but directing that the lotus fower has to “spend the night” with wine and beer—conditions that would likely permit alkaloid extraction. It is therefore interesting that depictions of the lotus fower being sniffed are the only artifactual suggestion of the possible medical use of lotus (Fig. 1.6).

Beer was thought to “gladden the heart” in general. Medicines mixed with beer—and combined with spells— were thought particularly effective. Beer and wine were also prescribed for children and nursing mothers. Childhood incontinence, for example, was treated in accordance with instructions from the Georg Ebers. The mother was to drink a cup of beer mixed with grass seeds and cyperus grass for 4 days while breastfeeding the child [14].

All over the world, indigenous people have learned the medicinal properties of plants in their environments. The remarkable accumulation of a fund of knowledge transmitted initially through oral tradition via specifc lines of professional authority (physicians, priests, specialized castes of

drug-gatherers and preparers), and a suffcient amount of experience to provide the basis for a systematic analysis of effcacy undoubtedly took a long time. It is extraordinary, moreover, for its survival and consistency through the ages, laying the groundwork for classical civilization and beyond.

Classical History

Greek Medicine

Chaldo-Egyptian magic, lore, and medicine were transferred to the coasts of Crete and Greece by migrating Semitic Phoenicians and Jews. The stage was then set for incorporating ancient Egyptian drug lore into Greek medicine. Two prominent medical groups developed on the mainland of Asia Minor (the region located in the southwestern part of Asia comprising most of what is present-day Turkey): the group on Cnidos, which was the frst, and then the group on Kos, of which Hippocrates (460–380 bce) was one member. While they were accomplished surgeons, they generally eschewed drugs, believing that most sick people get well regardless of treatment. Although Hippocrates did not gather his herbal remedies, he did prescribe plant drugs, and a cult of root diggers (rhizotomoi) developed, as did a group of drug merchants (pharmacopuloi). In Greece, plants were used not only for healing but also as a means of inducing death, either through suicide or execution; perhaps the best example was the death of Socrates.7 Later, Theophrastus (380–287 bc), a pupil of Aristotle (384–322 bce), classifed plants and noted their medicinal properties. This was a departure from previous recordings, as Theophrastus analyzed remedies on the basis of their individual characteristics, rather than a codifcation of combinations as in Egyptian formularies. He provided the earliest reference in Greek literature to Mandragora [15].

The father of history, Herodotus (484–425 bce) (Fig. 1.7), left a detailed description of the mass inhalation of cannabis in the Scythian baths:

The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy, and this vapour serves them instead of a water-bath; for they never by any chance wash their bodies with water. [16]

Compression of the great vessels of the neck was also recognized as a form of inducing unconsciousness. It was rec-

7 As related by Plato in Phaedo, Socrates was sentenced to die by drinking poison hemlock (Conium maculatum). Coniline, the biotransformation product post-ingestion, has a chemical structure similar to nicotine, which exerts its inhibitory actions on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors resulting in neuromuscular blockade, respiratory failure, and death.

9

1 The History of Sedation

Fig. 1.6 Stela (An upright stone slab or column typically bearing a commemorative inscription or relief design, often serving as a gravestone) of Ity (from the British Museum EA 586). Painted limestone Stela of Ity, dated to the 12th dynasty, c. 1942 bce. Ity’s many titles and the names of his mother, wife, sons, and daughters are listed. Note the illustration of the lotus fower being sniffed

Fig. 1.7 Bust of Herodotus (484–425 bce). Roman copy of the Imperial Era (second-century CE) after a Greek bronze originally of the frst half of the fourth-century BCE. Department of Greek and Roman Art, Gallery 162 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photograph: Nguyen, PBM (2017, April 12). Herodotus. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.ancient.eu/image/6501/ Published under a Creative Commons Attribution license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

ognized that compression of the carotid8 arteries would result in unconsciousness and insensibility, as would pressure on the jugular veins. Aristotle acknowledged this saying of jugular vein compression, “if these veins are pressed externally, men, though not actually choked, become insensible, shut their eyes, and fall fat on the ground” [17].

The poets Virgil and Ovid described the soporifc effects of opium. Virgil (70–19 bce) described the power of the poppy through the personifcation “Lethaeo perfusa papa-

8 The Greek word carotid means drowsiness, stupor, or soporifc— hence the carotid artery is the artery of sleep. Galen incorporated its use as an adjective when he stated, “I abhor more than anybody carotic drugs.”

vera somno” (“poppies steeped in Lethe’s slumber”),9 while Ovid (43 bce–17/18 bce) also invoked the personifcation of Lethe by stating, “There are drugs which induce deep slumber, and steep the vanquished eyes in Lethean night.”10

Roman Medicine

After the decline of the Greek empire following the death of Alexander the Great (323 bce), Greek medicine was widely disseminated throughout the Roman Empire by Greek physicians, who often were slaves. Dioscorides (c. 40–90 ce) described some 600 plants and non-plant materials including metals. His description of Mandragora is famous—the root of which he indicates may be made into a preparation that can be administered by various routes and will cause some degree of sleepiness and relief of pain [18]. Pliny the Elder (23–79 ce) described the anesthetic effcacy of Mandragora in the following manner:

…(Mandragora is) given for injuries inficted by serpents and before incisions or punctures are made in the body, in order to insure insensibility to pain. Indeed for this last purpose, for some persons the odor is quite suffcient to induce sleep. [19]

In the frst century, Scribonius Largus compiled Compositiones Medicorum and gave the frst description of opium in Western medicine, describing the way the juice exudes from the unripe seed capsule and how it is gathered for use after it is dried. It was suggested by the author that it will be given in a water emulsion for the purpose of producing sleep and relieving pain [20]. Galen (129–199 ce), another Greek, in De Simplicibus (about 180 ad), described plant, animal, and mineral materials in a systematic and rational manner. His prescriptions suggested medicinal uses for opium and hyoscyamus, among others; his formulations became known as galenicals

Islamic Medicine

In 640 ce , the Saracens conquered Alexandria, Egypt’s seat of ancient Greek culture, and by 711 ce , they were patrons of learning, collecting medical knowledge along the way. Unlike the Christians, who believed that one must suffer as part of the cure, the Saracens tried to ease the discomfort of the sick. They favored bitter drugs with orange peels and sweets, coated unpleasant pills with sugar, and studied the lore of Hippocrates and Galen. Persian physicians became the major medical teachers

9 Virgil, Georgics 1. 78

10 As recorded in Fasti, a Roman calendar, 4:661

10

R. S. Holzman

after the rise of the Baghdad Caliphate around 749 ce , with their teachings penetrating as far east as India and China. By 887 CE there was a medical training center with a hospital in Kairouan (present-day Tunisia) in Northern Africa.

The most prominent of the Arab writers on medicine and pharmacy were Rhazes (865–925 ce) and Avicenna (930–1036 ce), whose main work was A Canon on Medicine. The historical signifcance of this thread of recorded ancient medicine was that during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, this preserved knowledge was transmitted back to Christian Europe during the crusades. Avicenna noted the special analgesic and soporifc properties of opium, henbane, and mandrake (Fig. 1.8) [21].

Fig. 1.8 Avicenna (930–1036 ce). “If it is desirable to get a person unconscious quickly, without his being harmed, add sweet-smelling moss or aloes-wood to the wine. If it is desirable to procure a deeply unconscious state, so as to enable the pain to be borne, which is involved in painful application to a member, place darnel-water into the wine, or administer fumitory opium, hyoscyamus (half dram dose of each); nutmeg, crude aloes-wood (four grains of each). Add this to the wine, and take as much as is necessary for the purpose. Or boil black hyoscyamus in water, with mandragora bark, until it becomes red, and then add this to the wine” [21]

Medieval Medicine

The frst Christian early medieval reference to anesthesia is found in the fourth century in the writings of Hilary, the bishop of Poitiers [22]. In his treatise on the Trinity, Hilary distinguished between anesthesia due to disease and “intentional” anesthesia resulting from drugs. While St. Hilary does not describe the drugs that lulled the soul to sleep, at this time (and for the following few centuries) the emphasis remained on mandragora.

From 500 to 1400 ce, the church was the dominant institution in all walks of life, and medicine, like other learned disciplines, survived in Western Europe between the seventh or eighth and eleventh centuries mainly in a clerical environment. However, monks did not copy or read medical books merely as an academic exercise; Cassiodorus (c. 485 ce–c. 585 ce), in his efforts to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve sacred and secular texts, recommended books by Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides while linking the purpose of medical reading with charity care and help.

Conventional Greco-Roman drug tradition, organized and preserved by the Muslims, returned to Europe chiefy through Salerno, an important trade center on the southwest coast of Italy in the mid-900s. One of the more impressive practices documented at Salerno was intentional surgical anesthesia, described in Practica Chirurgiae in 1170 by the surgeon Roger Frugardi (Roger of Salerno, 1140–1195), in which he mentions a sponge soaked in “narcotics” and held to the patient’s nose. Hugh of Lucca (ca. 1160–1252) prepared such a sleeping sponge according to a prescription later described by Theodoric of Cervia (ca. 1205–1296). As an added precaution, Theodoric bound his patients prior to incision. The description of the soporifc sponge of Theodoric survived through the Renaissance largely because of Guy de Chauliac’s (1300–1367) The Grand Surgery and the clinical practices of Hans von Gersdorff (c. 1519) and Giambattista della Porta (1535–1615), who used essentially the same formula of opium, unripe mulberry, hyoscyamus, hemlock, Mandragora, wood ivy, forest mulberry, seeds of lettuce, and water hemlock (Fig. 1.9).

Ether

Ether was discovered in 1275 ce by the Spanish chemist Raymundus Lullus (c. 1232–1315). This new discovery was given the name “sweet vitriol.” In 1540 ce, the synthesis of ether was described by the German scientist Valerius Cordus (1514–1544 ce) who carefully specifed the materials to be used, the apparatus, and the procedure to be followed in order to distill “strong biting wine” (alcohol) with “sour oil of vitriol” (sulfuric acid). He recommended it for the relief of cough and pneumonia [25]. Paracelsus (1493–1541), a contemporary

11

1 The History of Sedation

Fig. 1.9 The alcohol sponge [23]. “Take of opium, of the juice of the unripe mulberry, of hyoscyamus, of the juice of hemlock, of the juice of the leaves of mandragora, of the juice of the wood-ivy, of the juice of the forest mulberry, of the seeds of lettuce, of the seeds of the dock, which has large round apples, and of the water hemlock—each an ounce; mix all these in a brazen vessel, and then place in it a new sponge; let the whole boil, as long as the sun lasts on the dog-days, until the sponge consumes it all, and it is boiled away in it. As oft as there shall be need of it, place this sponge in hot water for an hour, and let it be applied to the nostrils of him who is to be operated on, until he has fallen asleep, and so let the surgery be performed. This being fnished, in order to awaken him, apply another sponge, dipped in vinegar, frequently to the nose, or throw the juice of the root of fenugreek into the nostrils; shortly he awakes” [24]

of Cordus, came surprisingly close to the recognition of ether as an anesthetic [26]. Later, in 1730, the German scientist W. G. Frobenius changed the name of sweet vitriol to ether.

Varied Preparations of Varying Potencies

If the constituents of the plants were combined with fats or oils, they would penetrate the skin or could be easily absorbed via the sweat ducts in the axillae or body orifces such as the vagina or rectum. This would allow the psychoactive tropane

Fig. 1.10

John Arderne (1307–1380). “An ointment with which if any man be anointed he shall suffer cutting in any part of his body without feeling or aching. Take the juice of henbane, mandragora, hemlock, lettuce, black and white poppy, and the seeds of all these aforesaid herbs, if they may be had, in equal quantities; of Theban poppies and of poppy meconium one or two drachms with suffcient lard. Braise them all together and thoroughly in a mortar and afterwards boil them well and let them cool. And if the ointment be not thick enough add a little white wax and then preserve it for use. And when you wish to use it anoint the forehead, the pulses, the temples, the armpits, the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet and immediately the patient will sleep so soundly that he will not feel any cutting” [27, 28]

alkaloids, especially hyoscine, access to the blood and brain without passage through the gut, thus avoiding the risk of poisoning. A few prominent surgeons offered statements about the mode of application of such salves or “ointments.”

John Arderne (1307–1380) (Fig. 1.10), known for his success curing fstula-in-ano, and Andres De Laguna (1499–1560) (Fig. 1.11), physician to Emperor Charles V and Philip II, provided unambiguous descriptions of soporifcs.

12

R. S. Holzman

Fig. 1.11 Andres de Laguna (1499–1560 ce). “…a pot full of a certain green ointment…with which they were anointing themselves…was composed of herbs…such as hemlock, nightshade, henbane, and mandrake…I had the wife of the public executioner anointed with it from head to foot…she…had completely lost power of sleep…no sooner did I anoint her than she opened her eyes, wide like a rabbit, and soon they looked like those of a cooked hare when she fell into such a profound sleep that I thought I should never be able to awake her…after a lapse of thirty-six hours, I restored her to her senses and sanity” [29]

The uncertainty of the potency and action of the narcotic drugs rendered their application dangerous, and by the end of the sixteenth century, such anesthetics had largely fallen into disrepute and disuse. Indeed, if physicians tried to use “narcotic” herbals in the middle of the seventeenth century, they were condemned, arrested, and fned or tried for practicing witchcraft [30]. Many of the early books were herbals, and Gerard (1545–1612) warned of the alkaloids “… this kind of Nightshade causeth sleepe…it bringeth such as have eaten thereof into a ded sleepe wherein many have died” [31].

The Scientifc or Modern Epoch

The divergence of herbalism (botany) and medicine began in the seventeenth century as part of the larger movement known alternatively as natural philosophy, scientifc deism,

and the scientifc revolution. An attempt to develop quantitative methodology characterized science, and at the forefront of these attempts was the chemical analysis of the active ingredients in medicinal plants.

Following his clinical observation of poisoning in children who had mistaken water hemlock for parsnip root, Johann Jakob Wepfer (1620–1695) demonstrated dosedependent toxic effects in dogs of the alkaloids eventually isolated as strychnine, nicotine, and conine [32, 33]. Thus, this early quantitative approach gave rise to the development of modern chemistry and pharmacology. This was frst successfully applied to anesthetic pharmacology by Friedrich Wilhelm Adam Serturner (1783–1841) who, in 1805, described the isolation of meconic acid from the crude extract of opium and, in 1806, extracted opium. He further experimented with this crystal on dogs, fnding that it caused sleep and indifference to pain and called this new substance morphine, in honor of the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus. This science of pharmacology—the interaction of chemistry with living matter—thus began to replace the ancient and descriptive materia medica of herbalism and set the stage for the advances of the second half of the nineteenth century, which included modern surgical anesthesia.

The introduction of these drugs directly into the vascular system was developed by (Sir) Christopher Wren (1632–1723) at Oxford in 1656 when he convinced his friend Robert Boyle (1627–1691) to experiment with a quill attached to a syringe through which opium was injected into a dog. What they found was that the opium made the dog stuporous, but did not kill him. Not long thereafter, in 1665, Johann Sigismund Elsholtz (1623–1688) administered opiates intravenously to humans in order to achieve unconsciousness, as described in his 1667 work Clysmatica Nova (Fig. 1.12) [34]. He performed early research into blood transfusions and infusion therapy and speculated that a husband with a “melancholic nature” could be revitalized by the blood of his “vibrant wife,” leading to a harmonious marriage. Direct transfusion of blood between animals was accomplished later that same year, and human transfusion followed 2 years later. Lamb’s blood was usually used, until James Blundell (1791–1878) transfused human blood into humans.

By the 1830s, physiologists and elite doctors envisioned a level of unconscious life separable from the higher functions and the mind, including suffering. Advances in surgical thought, including more conservative and slower surgery, intensifed the problem of pain for both patient and surgeon. By the mid-1840s, pain no longer seemed physiologically necessary or socially acceptable, but the intensive use of drugs known to diminish surgical pain was dangerous, and non-pharmacological alternatives such as mesmerism were highly contentious and controversial.

Mesmerism, the predecessor of hypnosis, was based on Franz Anton Mesmer’s (1734–1815) belief that a magnetic

13

1 The History of Sedation