POLICY BRIEF

A Tool for System Change: Turning Water Insecurity Into Action

Matthew Blair*, Parmees Fazeli*, Danielle Frankel*, Sofia Jacobson*, Surabhi Kumar*, Nolyn Mjema*, Avi Patel*, Alejandro Rojas*, Cara Kiernan Fallon, Catherine Panter-Brick, Sera L. Young

*co-first authors

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Water is essential to every aspect of life, influencing the nutrition, hygiene, culture, and livelihood of humans. Despite such importance, the necessity of water is often overlooked. Whereas people and policy makers see food insecurity as a major concern, water insecurity receives less attention. The Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scale is a comprehensive set of scales that measure both household (HWISE) and individual (IWISE) water insecurity. These scales not only measure physical access to water, but also emotional, social, and health-related dimensions (e.g., worry, hygiene, psychological stress). Administered quickly and adaptable across global contexts, the WISE Scale serves as a sensitive and equity-focused instrument that reveals disparities in gender, nutrition, and health. This policy brief analyzes four case studies to better understand the global impact and policy relevance of the WISE Scale. In the first case study, on Cameroon, IWISE data identified that nearly two-thirds of adults experience moderate-to-high water insecurity, correlating strongly with child diarrheal disease and malnutrition. The second case study, on India, exposed gender inequities, demonstrating how women disproportionately bore the physical and emotional burdens of water collection and household management. In the third case study, on Kenya, a direct link between water and food insecurity demonstrated how limited water access affects nutrition, meal preparation, and public health outcomes. In the fourth case study, on Australia, survey results indicated that water insecurity reaching 44% spurred governmental intervention, illustrating the tool’s ability to translate measurement into concrete policy action.

With nationally representative data published in forty countries and implementation underway in an additional forty countries, the WISE Scale’s global reach underscores its versatility and policy relevance. By providing culturally sensitive, comparable data, these scales empower governments, NGOs, and researchers to design targeted interventions and monitor progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 6 (ensuring clean water and sanitation for all). The WISE Scale also emphasizes that water access is understood not only as an infrastructure issue but as a lived experience central to human dignity.

KEY INSIGHTS

• Water security is important for a variety of aspects of life (religious, dietary, hygiene, etc.). There is often a disconnect between water and food insecurity; however, it is critical that they are thought of together.

• The Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scale is a validated, sensitive metric, with an ability to capture disparities in gender, nutrition and health risks. It is an impactful tool that can be leveraged to measure water insecurity experiences in diverse settings.

• This brief presents case studies from four countries (Cameroon, India, Kenya, and Australia) to highlight how the WISE Scale has been deployed and disseminated to measure individual and household experiences with water insecurity.

• Integrating the WISE Scale into routine policy planning will produce metrics for governments and partner organizations to refine resource allocation and increase the return on investment of water-centered interventions.

BACKGROUND

Water is essential to life. A majority of the body is made up of water—75% in infants and 55% in adults. Without water consumption, humans can die within three days.1 The physiological importance of water cannot be understated; it plays a key role in thermoregulation, transportation of nutrients, and removal of waste.2 Along with its physiological importance, water also has a distinct cultural significance, playing an important role in sanitation, hygiene, and cultural practices.3 Water security is the ability to safely and sustainably manage water for agriculture, economic, and human development.4 A lack of specific components of water security, availability, access, use, and stability can lead to water insecurity.5 Due to the multiplicative effects of climate change, rapid population growth, and poor water management, global water demand is outpacing supply, leading to widespread water insecurity.6 7 Now, over a quarter of the world is water insecure.8

Over the past decade, there has been an emerging emphasis on water security.9 However, water security is often thought of as secondary to food security.5 As a result of the novelty of the field of water insecurity, there is a lack of data on the negative health effects of water insecurity on the population. The data on water security has focused mainly on accessibility and adequacy of water.10 However, solely focusing on these two aspects of water security is an injustice to the multifaceted role water plays in daily life. In the 2010s, researchers, through qualitative studies, gleaned how water insecurity has a multitude of negative effects on individuals’ determinants of health.8 This study has illustrated the need for a versatile measurement for water insecurity that takes into account the various components of water insecurity.

Yet, the variety of water insecurity measurements in the literature does not illustrate the lived experience of water insecurity. Water insecurity is a multidimensional issue that can negatively affect the individual’s determinants of health. An adaptable metric is needed to quantify the scope of global water insecurity.

The Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scale represents a family of scales, developed by an inter-

disciplinary group of experts. It offers a rigorously validated and cross-cultural approach to measuring how households and individuals experience water insecurity, which is an essential complement to traditional infrastructure and access indicators.

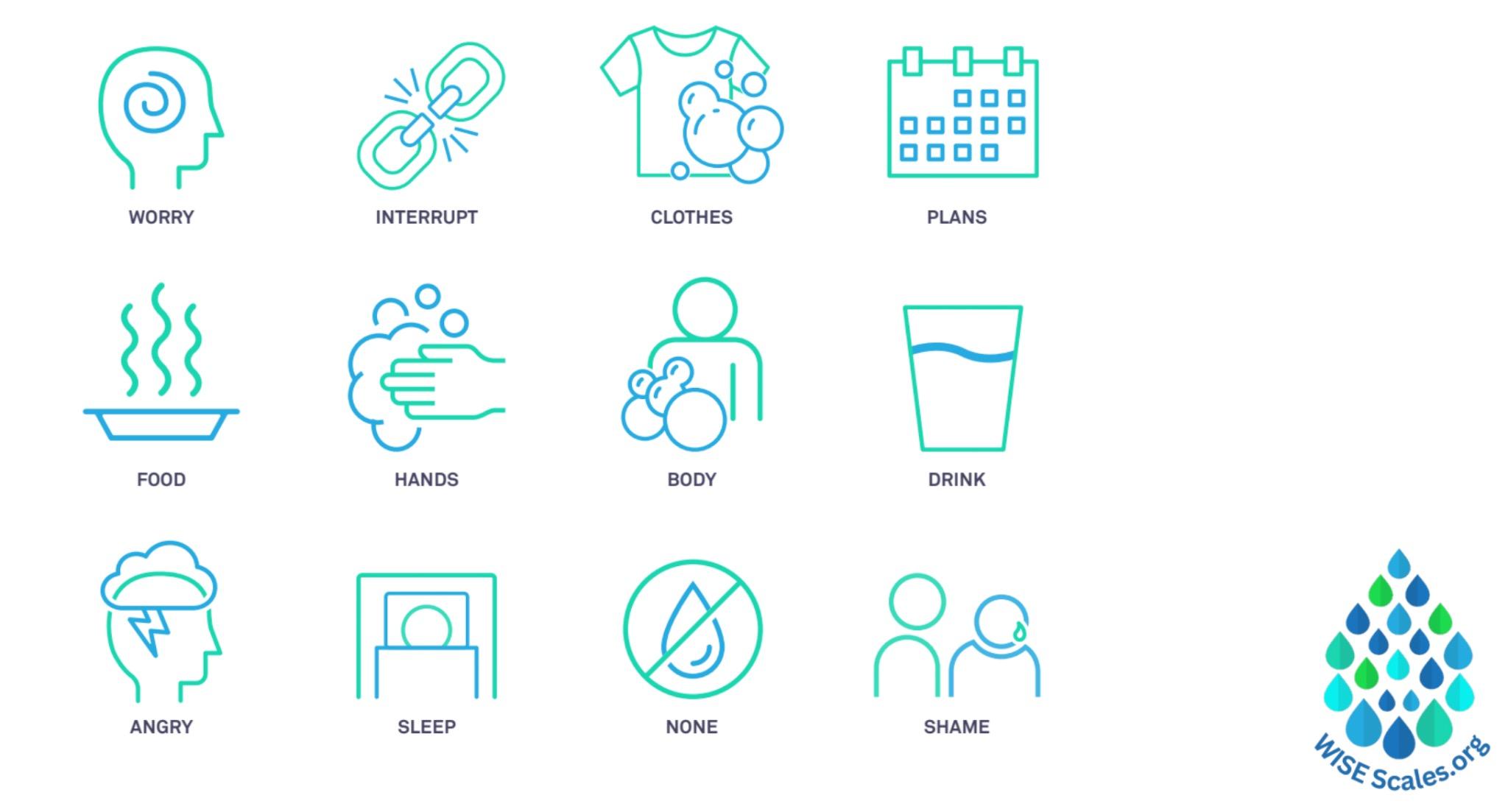

The Household Water Insecurity Experiences Scale (HWISE) Scale is the first globally validated metric for assessing household-level water insecurity, using 12 survey items that can capture key dimensions such as worry about having enough water, disruptions to daily plans, challenges with hygiene or food preparation, and emotional burdens such as anger or shame (Figure 1). These items reflect the frequency and severity of water-related challenges using a standard response scale (“never,” “rarely,” “sometimes,” “always”), and the survey can be administered in as little as three minutes.11

An abbreviated 4-item version, HWISE-4, allows for rapid, low-cost monitoring suitable for routine surveys and comparative analyses, which can take survey participants one minute to complete. The 4-item scale inquires about the frequency (never, rarely, sometimes, always) with which subjects have struggled with the following areas pertaining to water insecurity: worry, plans, hand-washing, and drinking water.12

Figure 1: Twelve items in the Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scale. Each icon represents a survey question assessing a given water-related challenge. Items include emotional (worry, anger, shame), practical (interruptions to plans, difficulties with obtaining food, drink, or sleep), and hygiene-related experiences (hand, body, and clothes washing). The abbreviated HWISE-4 and IWISE-4 evaluate the following: worry, plans, hand-washing, and drink. Together, these twelve items form the validated HWISE and IWISE scales used to capture the frequency and severity of water insecurity across global and cultural contexts. Figure adapted from Bethancourt, H. J., Frongillo, E. A., & Young, S. L. (2022). Validity of an abbreviated Individual Water Insecurity Experiences (IWISE-4) Scale for measuring the prevalence of water insecurity in low- and middle-income countries.14

For individual-level assessment, the Individual Water Insecurity Experiences (IWISE) Scale, available in both 12-item and 4-item forms, extends this metric approach to water-insecure experiences on a personal level.13 14 Taken together, the WISE family of tools pro-

MAP

The Global Coverage of the WISE Scale

vides decision-makers with precise, comparable, and culturally adaptable metrics that 1) reveal disparities, 2) capture the multi-faceted nature of water insecurity, and 3) enable consistent and reliable tracking of progress towards equitable water access.

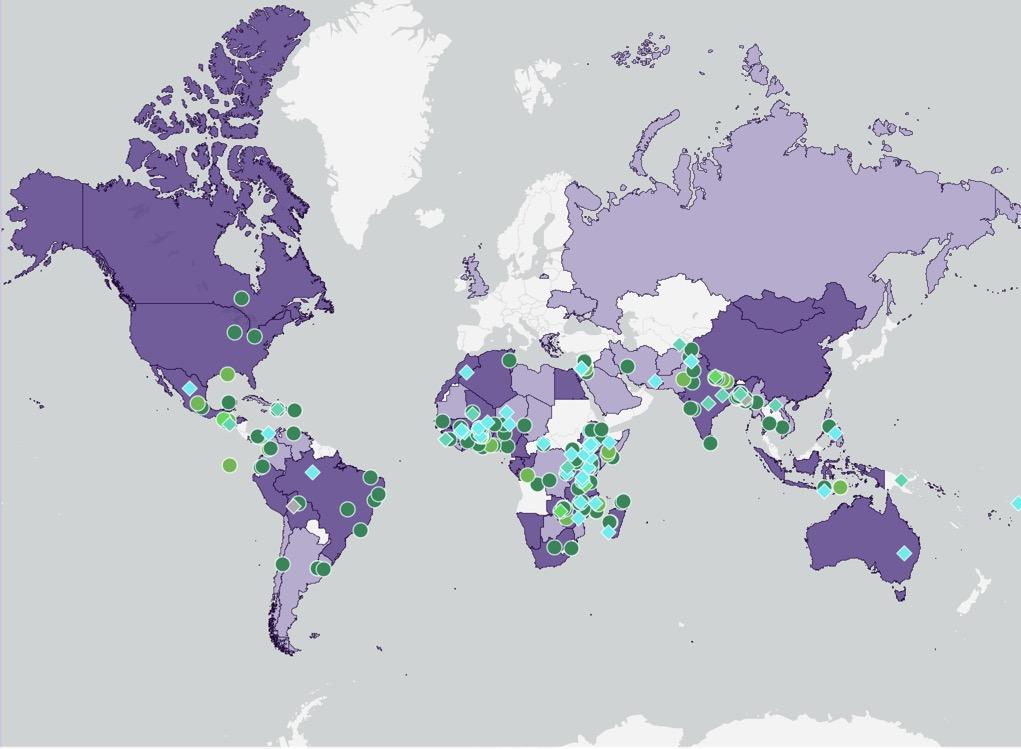

Figure 2: Forty countries have already implemented the WISE Scale and published nationally representative data (dark purple), and an additional forty countries are preparing to launch (light purple). By early 2026, there will be nationally representative data available for a total of eighty countries through the Gallup World Poll. Figure adapted from Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scales: WISE Interactive Map.30

The WISE family of scales measures water insecurity at different levels of experience. HWISE-12 captures household-level disruptions across twelve domains, including worry, interruptions to daily tasks, hygiene challenges, and food- or sleep-related impacts to provide a broad picture of how water instability affects entire households. IWISE-4, derived from four core items (worry, plans, hands, and drink), measures individual experiences in a rapid, comparable format. On the map, diamonds indicate planned site-specific data collection using these scales, while circles represent sites where data collection is already complete.

The map’s color scheme distinguishes which scale

each site used. Dark green circles represent completed HWISE-12 studies, green circles indicate completed HWISE-4, light green circles show completed IWISE-12, and teal circles reflect completed IWISE-4. For planned studies, light blue diamonds denote HWISE-12, teal diamonds mark HWISE-4, and light green diamonds indicate IWISE-12. This color-coded system makes it easy to see how different regions select either the full household instrument or the shorter individual-level variants.

The map shows a wide geographic spread of WISE implementation, with dense clusters of completed and planned sites across Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America. The mix of HWISE-12, HWISE-4,

and IWISE indicators across countries reflects how research teams select scales to match local needs. These range from comprehensive household studies to streamlined individual assessments. Together, the

CASE STUDIES

risks

Kenya Food insecurity

India Gender

Australia Action

distribution of markers illustrates the steady expansion of the WISE tools into diverse global contexts and the growing infrastructure for comparable water insecurity measurement worldwide.

Utilization of the IWISE Scale in Cameroon illustrated how this tool can be used to understand health risks related to water insecurity.

Analysis using the WISE Scale reveals the association between water insecurity and food insecurity, prompting additional consideration for public health interventions.

The potential use of the WISE Scale can help reveal the gender disparities of water insecurity in India.

The data generated by the implementation of the WISE Scale in the town of Walgett garnered great media attention and the government quickly responded.

Table 1: Overview of the Case Study Thematic Analysis. Table created internally by authors.

CAMEROON:

WISE Scale reveals health risks

Cameroon offers a compelling case study to illustrate how the WISE Scale can deepen the understanding of water-related health risks and their impacts on communities and individuals. Cameroon is a lower-middle-income nation in west-central Africa, stretching from the Gulf of Guinea in the south up to Lake Chad in the north. In 2023, Cameroon had a population of 28.37 million.15 In 2024, the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was USD 1,467; the real GDP grew by 3.5% this year.16 In 2020, researchers from Gallup World Poll, Northwestern University, and others conducted a study to measure the water insecurity in Cameroon. Respondents were selected using probability-based sampling with post-stratification weights to ensure the 1,024 respondents were representative of the Cameroonian population ≥15 years of age.17 The Individual Water Insecurity Experiences (IWISE) Scale was used to measure individual experiences with water

access and use.

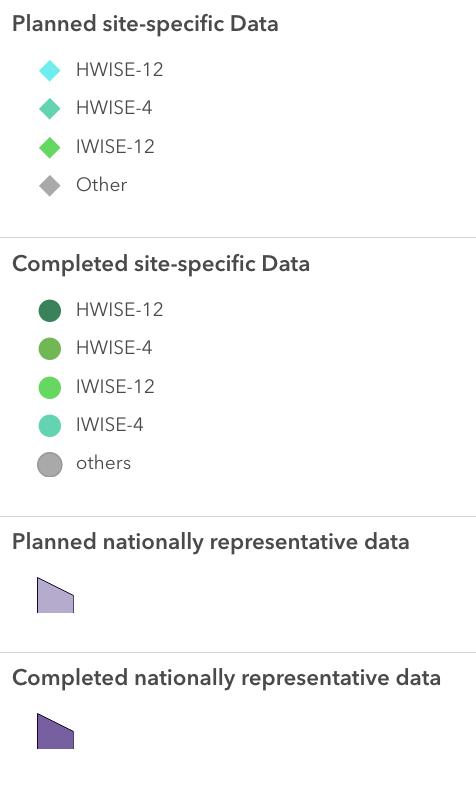

The IWISE Scale found that 63.9% of Cameroonian adults experienced moderate-to-high water insecurity in 2020. This is an extremely significant percent of the population, the highest among any country where the WISE Scale was conducted. Also, researchers found that 55.5% of the respondents had to eat differently and 61.4% had no water to safely consume due to water insecurity. One study done by Yongsi et al. revealed a diarrhea prevalence among children to be 14.4%; various risk factors were examined and water-supply modes and quality of drinking-water were statistically associated with diarrhea cases.18 An additional study by Nounkeu et al. examined specifically rural households and found the incidence of diarrhea among children in water insecure households to be 79%.19 Although a comparison of adult and children age groups, the connection between the health risk and water insecurity show a potential association and connection. Understanding water insecurity through the WISE Scale is essential to capturing and predicting how

1

inadequate water access contributes to nutritional deficits, diarrheal disease, and other profound health risks. The WISE Scale tools are essential in creating active communication and policies for the general health and wellness of populations.

INDIA:

WISE Scale reveals gender role disparities

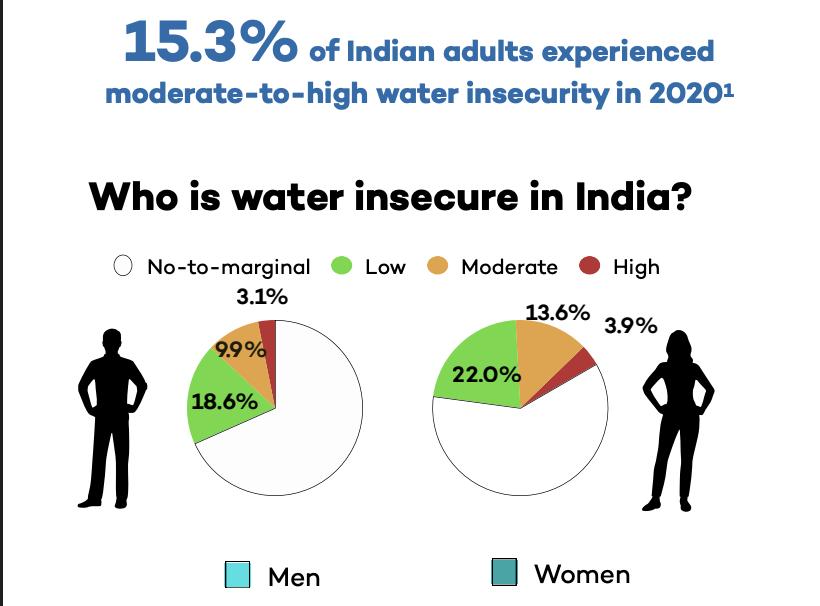

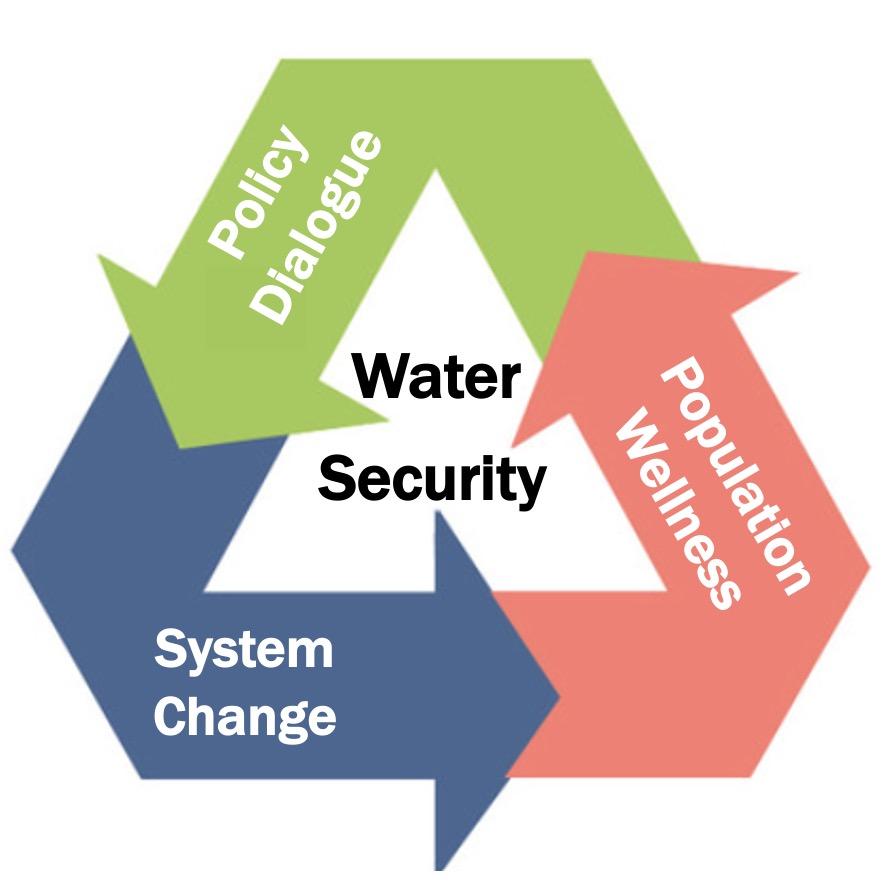

Figure 3

India illustrates how deeply social constructs, particularly gender, influences experiences of water insecurity. According to a 2020 Gallup World Poll, 15.3% of the population faces moderate to high water insecurity, distributed unevenly across gender, income, and geography.20 The poll reveals that 17.5% of Indian women experience moderate to high water insecurity versus 13.0% of Indian men. Previous research suggests that women disproportionately shoulder domestic water responsibilities, often collecting and managing household water and prioritizing their family’s needs above their own. These gendered roles heighten women’s physical, emotional, and time-related vulnerabilities, revealing aspects of water insecurity that conventional metrics miss.21

Despite ongoing efforts toward integrated water resource management, policy frameworks in India still focus heavily on the rural–urban divide and overlook the social dimensions that impact lived experiences. 22 If implemented, the IWISE/WISE Scale could provide substantial value by capturing experiential data as it allows measurement of the psychosocial and gendered impacts of water insecurity rather than relying solely on infrastructure-based indicators. Applying the IWISE Scale in India would thus help illuminate the unequal burdens carried by women and better inform equitable policy responses to have ground water security strategies in everyday reality.

KENYA:

WISE Scale reveals association between water insecurity and food insecurity

Studies from Kenya have provided strong evidence of the relationship between water insecurity and food insecurity, prompting essential considerations for future effective public health interventions. According to a Gallup World Poll conducted in collaboration with Northwestern University and others, 44.6% of Kenyan adults experienced moderate-to-high water insecurity in 2020. More specifically, in the poorest 20% of households, 54.4% of men and 56.7% of women were water insecure. Strikingly, data gathered using the IWISE Scale revealed that 74.1% of Kenyans experienced water interruptions, 72.2% were worried about water, and 59.3% had to change plans due to water insecurity.23

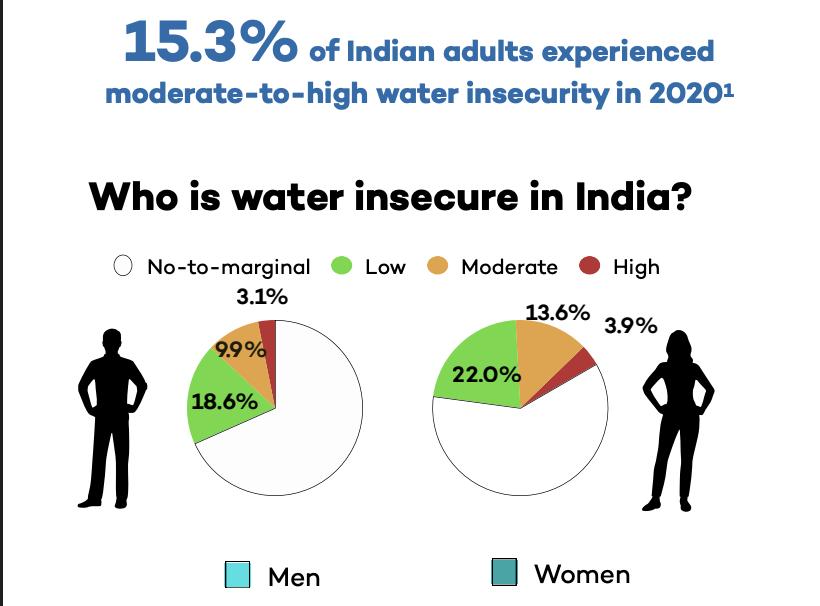

By harnessing water insecurity data, researchers have conducted several studies in Kenya that reveal a strong relationship between water insecurity and food insecurity. For example, in a 2022 paper, authors report an extremely high prevalence of concurrent moderate-to-severe household water insecurity (HWI) and household food insecurity (HFI) among a semi-nomadic pastoralist population of Daasanach living in an arid region of northern Kenya, where water availability is extremely limited. Researchers found that HWI is strongly related to more frequent experiences with

HFI, independent of socioeconomic status (SES). 24 Other Kenya-based studies incorporating the WISE Scale have reported similar results, indicating that better water quantity, water quality, and reduced time spent on water management are all associated with a greater household food security, controlling for other variables.25 Researchers observe that households are forced to change what they consume due to problems related to water insecurity. This combined research suggests that although HWI and HFI probably co-occur because of a shared cause (resource scarcity and/or variation in social status), they may also relate to each other independently of financial and social capital. For example, HWI may exacerbate HFI independently of SES because water availability affects which foods can be cooked or prepared. In the Kenyan context, the local dish of whole maize and beans requires substantial water for preparation; therefore, it may be easier to resort to milled maize porridge when water is inaccessible. Other mechanisms responsible for this association include household money meant to be spent on food being diverted to purchase clean water, or women needing to collect water instead of having adequate time to prepare food.26

These research findings yield important implications for policies and interventions related to food insecurity, especially in settings where limited or unreliable access to water frequently disrupts daily life, constrains time, and restricts what foods can be prepared. For example, food aid programs that distribute

foodstuffs requiring sufficient water to prepare may be less beneficial in regions with seasonal or chronic water scarcity. Ideally, interventions should support the maintenance and development of water services that provide reliable support for livestock and human agricultural needs. With the Kenyan Ministry for Water, Environment, and Natural Resources reportedly utiliz-

ing the WISE Scale for policymaking, extra attention will be directed towards the association between water insecurity and food insecurity in Kenya. Ideally, other governments will follow suit by incorporating water insecurity data collected through the WISE Scale to inform policies related to broader health and welfare issues, including food insecurity.

Figure 5: Predicted HFIAS (Household Food Insecurity Access Scale) scores in relation to HWISE scores in Daasanach household sample. Figure adapted from Bethancourt H.J., Swanson Z.S., Nzunza R., Young S.L., Lomeiku L., Douglass M.J., et al. (2022). The co-occurrence of water insecurity and food insecurity among Daasanach pastoralists in northern Kenya.24

AUSTRALIA:

A Success Story

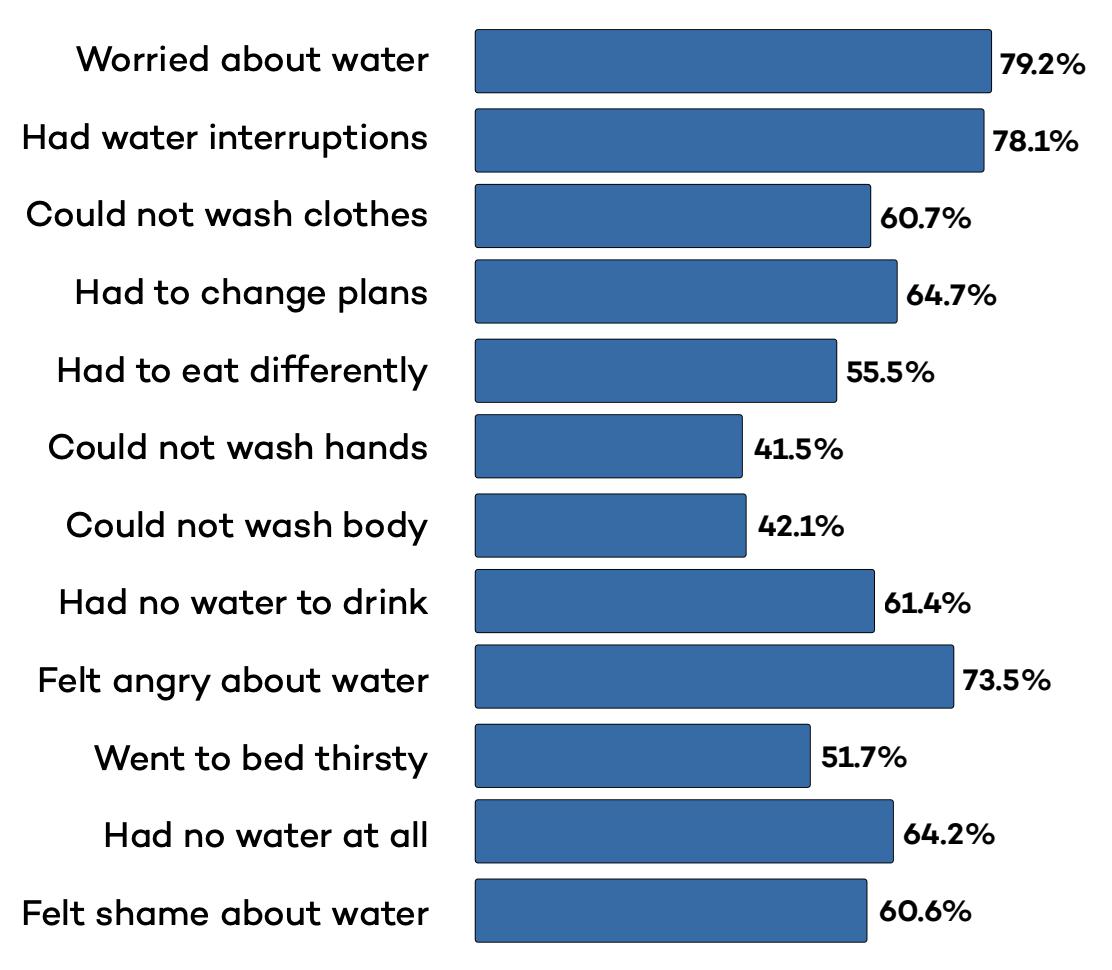

The uses of the WISE Scale are far-reaching, and examples abound of its successful implementation. One such example comes from a small region of Australia, where the WISE Scale directly motivated governmental action. The town of Walgett, located in New South Wales, is composed primarily of Australia’s Aboriginal population. The WISE Scale was administered in April of 2022 to 251 individuals via a community-based survey approach. These surveys were administered by the Dharriwaa Elders Group (DEG) and Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service (WAMS) as part of the Food and Water for Life Program, a product of the DEG’s Yuwaya Ngarra-li partnership with UNSW and The George Institute for Global Health.

As published in a February, 2023 report, researchers found that 44% of the Walgett Aboriginal population was water insecure, a striking figure compared to the 1% of Australia’s total population that is water insecure. Two-fifths, or 42%, of participants experienced no usable or drinkable water and 36% went to sleep thirsty in at least one month in the last year.27 Additional findings from the report were also compelling (Figure 6). This WISE report attracted much media attention and motivated direct government action. The Minister of New South Wales vowed in May of that same year to address the problem. Soon thereafter, government resources were directed to remediate the severe conditions in the region.28 In Australia and across the world, the WISE Scale is already sparking action to promote water security and generate positive change for communities everywhere.

Figure 6: Water security in Walgett. Figure adapted from Tonkin et al. (2023). Food and Water for Life, Key findings from the Food and Water Security Surveys in Walgett, Yuwaya Ngarra-li Community Briefing Report.27

POLICY RECOMMENDATION AND CONCLUSION:

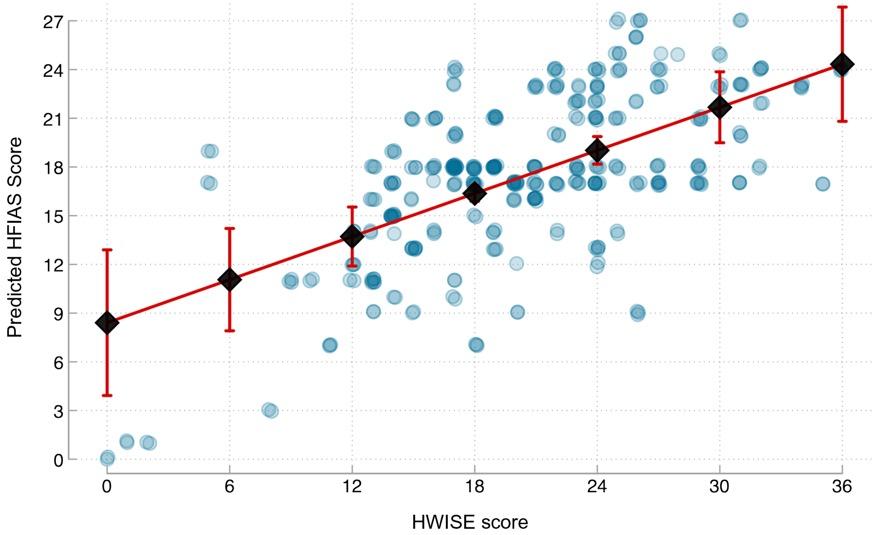

The WISE Scale is a fast, effective, and validated tool that quantifies varied aspects of water insecurity. It has been applied in countries of various compositions: in low-and-middle-income countries like Kenya and Cameroon, high-income countries like Australia, and countries with dense populations like India. Despite the WISE Scale’s effectiveness and flexibility, it has only been applied in 40 countries, a small portion of the 193 member states recognized by the United Nations.30 The scale must be more widely used and we encourage governments, private institutions, research bodies, and individual actors to promote and utilize the WISE Scale, helping to rightfully cement it as a global measure of water insecurity. In an environment where bureaucrats and researchers are inundated with new guidelines and recommendations daily, the WISE Scale is a simple and fast, yet also comprehensive, way to illuminate trends in water insecurity, inform interventions, and efficiently allocate resources to promote population wellness (Figure 7). Further, the data generated by these scales serves as very tangible evidence for activists and policymakers to point to, hold governments accountable, and help motivate action. While the upfront cost of integrating the WISE scale into decision-making might seem large,

this investment has the potential to save costs down the road and generate improvements in population health. By identifying and quantifying water insecurity, the WISE Scale data is not just another data point, but is a critical lever to help generate system change.

Figure 7: Impact of Policy Recommendations for Water Insecurity. Figure created internally by authors.

HOW TO CITE

Blair M*1, Fazeli P *1, Frankel D*1, Jacobson S*1, Kumar S*1, Mjema N*1, Patel A*1, Rojas A*1, Fallon CK1, Panter-Brick C1, Young SL2 (2026). A Tool for System Change: Turning Water Insecurity Into Action. Policy Brief, Global Health Studies Program, Jackson School of Global Affairs, Yale University.

*Co-first authors

1 Jackson School of Global Affairs, Global Health Studies Program

2 Northwestern University, Anthropology & Global Health Studies

REFERENCES

1 Yamada, Yosuke et al. “Variation in human water turnover associated with environmental and lifestyle factors.” Science (New York, N.Y.) vol. 378,6622 (2022): 909-915. doi:10.1126/science.abm8668

2 Popkin, B. M., D’Anci, K. E., & Rosenberg, I. H (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439–458. PubMed Central. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x

3 MacAlister, Charlotte , et al. Global Water Security 2023 Assessment. United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, 23 Mar. 2023.

4 Bigas, H. (2013). Water Security & the Global Water Agenda: A UN-Water Analytical Brief (pp. 1–17). United Nations Water Task Force. https://www.unwater.org/sites/default/files/app/uploads/2017/05/analytical_brief_oct2013_web.pdf

5 Young, S. L., Frongillo, E. A., Jamaluddine, Z., Melgar-Quiñonez, H., Pérez-Escamilla, R., Ringler, C., & Rosinger, A. Y. (2021). Perspective: The Importance of Water Security for Ensuring Food Security, Good Nutrition, and Well-being. Advances in Nutrition, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmab003

6 Salehi, Maryam. “Global Water Shortage and Potable Water Safety; Today’s Concern and Tomorrow’s Crisis.” Environment International, vol. 158, no. 0160-4120, Jan. 2022, p. 106936, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0160412021005614, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106936.

7 Vorosmarty, C. J. (2000). Global Water Resources: Vulnerability from Climate Change and Population Growth. Science, 289(5477), 284–288. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.289.5477.284

8 Mekonnen, Mesfin M., and Arjen Y. Hoekstra. “Four Billion People Facing Severe Water Scarcity.” Science Advances, vol. 2, no. 2, 12 Feb. 2016, p. e1500323.

9 Jägerskog, Anders & Swain, Ashok & Öjendal, Joakim. (2014). Introduction: The Age of Water Security – Current Dilemmas and Future Challenges. Introduction – Security and Its Relation to Water.

10 Stevenson, Edward G.J., et al. “Water Insecurity in 3 Dimensions: An Anthropological Perspective on Water and Women’s Psychosocial Distress in Ethiopia.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 75, no. 2, July 2012, pp. 392–400, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.022. Accessed 17 Feb. 2020.

11 Young, S. L., Collins, S. M., Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Jamaluddine, Z., Miller, J. D., Brewis, A. A., Frongillo, E. A., Jepson, W. E., Melgar-Quiñonez, H., Schuster, R. C., Stoler, J. B., Wutich, A., & HWISE Research Coordination Network (2019). Development and validation protocol for an instrument to measure household water insecurity across cultures and ecologies: the Household Water InSecurity Experiences (HWISE) Scale. BMJ open, 9(1), e023558. https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023558

12 Young, S. L., Miller, J. D., Frongillo, E. A., Boateng, G. O., Jamaluddine, Z., Neilands, T. B., & and the HWISE Research Coordination Network. (2021). Validity of a Four-Item Household Water Insecurity Experiences Scale for Assessing Water Issues Related to Health and Well-Being. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104(1), 391-394. Retrieved Nov 2, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0417

13 Young SL, Bethancourt HJ, Ritter ZR, Frongillo EA. The Individual Water Insecurity Experiences (IWISE) Scale: reliability, equivalence and validity of an individual-level measure of water security. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6:e006460. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006460

14 Bethancourt, H. J., Frongillo, E. A., & Young, S. L. (2022). Validity of an abbreviated individual water insecurity experiences (IWISE-4) scale for measuring the prevalence of water insecurity in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(9), 647–658. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2022.094

15 Climate Risk Profile: Cameroon (2025): The World Bank Group.

16 Climate Risk Profile: Cameroon (2025): The World Bank Group.

17 Sera L. Young. (2024). National Water Insecurity in Cameroon. https://doi.org/10.21985/N2-TM05-T080

18 Yongsi, H. B. N. (2010). Suffering for Water, Suffering from Water: Access to Drinking-water and Associated Health Risks in Cameroon. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 28(5), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn. v28i5.6150

19 Nounkeu, C., Kamgno, J., & Dharod, J. (2019). Assessment of the relationship between water insecurity, hygiene practices, and incidence of diarrhea among children from rural households of the Menoua Division, West Cameroon. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 10(1), 951. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2019.951

20 Young, S. (2024, March 21). Arch : Northwestern University Institutional Repository. National Water Insecurity in India. https://doi.org/10.21985/n2-hr1x-x003

21 Das, D., & Safini, H. (2018). Water Insecurity in Urban India: Looking Through a Gendered Lens on Everyday Urban Living: Looking Through a Gendered Lens on Everyday Urban Living. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 9(2), 178-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425318783550 (Original work published 2018)

22 Kaur, S., Gauttam, P. (2022). Water Security in India: Exploring the Challenges and Prospects. In: Singh, S.K., Singh, S.P. (eds) Nontraditional Security Concerns in India. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-98116-3735-3_11

23 Young, S.L. (2024). National Water Insecurity in Kenya. Individual Water InSecurity Experiences. https://doi. org/10.21985/n2-07t8-zw27

24 Bethancourt H.J., Swanson Z.S., Nzunza R., Young S.L., Lomeiku L., Douglass M.J., et al. (2022). The co-occurrence of water insecurity and food insecurity among Daasanach pastoralists in northern Kenya. Public Health Nutrition. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001689

25 Brewis, A., Workman, C., Wutich, A., Jepson, W., Young, S., & Household Water Insecurity Experiences - Research Coordination Network (HWISE-RCN) (2020). Household water insecurity is strongly associated with food insecurity: Evidence from 27 sites in low- and middle-income countries. American journal of human biology : the official journal of the Human Biology Council, 32(1), e23309. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23309

26 Brewis, A., Workman, C., Wutich, A., Jepson, W., Young, S., & Household Water Insecurity Experiences - Research Coordination Network (HWISE-RCN) (2020). Household water insecurity is strongly associated with food insecurity: Evidence from 27 sites in low- and middle-income countries. American journal of human biology : the official journal of the Human Biology Council, 32(1), e23309. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23309

27 Tonkin, T., Deane, A., Trindall, A., Weatherall, l., Madden, T., Moore, B., Earle, N., Nathan, M., Young, S., McCausland, R., Leslie, G., Bennett-Brook, K., Spencer, W., Corby OAM, C., Webster, J., Rosewarne, E. (2023). Food and Water for Life, Key findings from the Food and Water Security Surveys in Walgett, Yuwaya Ngarra-li Community Briefing Report; Yuwaya Ngarra-li. https://www.unsw.edu.au/content/dam/pdfs/edi/2023-06-yn-news/2023-06-walgettfood-water.pdf

28 Marlan, Z., & Kennedy, J. (2023, May 4). After five years of drinking water described as “filth”, change is finally on the way for Walgett. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-04/walgett-drinking-water-now-being-sourcedfrom-namoi-river/102301424; Morse, C. (2023, May 3). NSW Government vows to address Walgett’s “intolerable” dangerous drinking water situation. National Indigenous Times. https://nit.com.au/03-05-2023/5821/nsw-government-responds-to-walgetts-intolerable-drinking-water-situation

29 Children in Cameroon filling up water tanks. Courtesy of Water, sanitation and hygiene | UNICEF Cameroon. (n.d.) https://www.unicef.org/cameroon/water-sanitation-and-hygiene-0

30 Water Insecurity Experiences (WISE) Scales: WISE Interactive Map, ArcGIS Online, Northwestern University https:// northwestern.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/basic/index.html?appid=3f465415645243ee8466a335c4cde23e