PORTRAYALS

JAC DE VILLIERS

JAC DE VILLIERS

1976-2024

PORTRAYALS is a selection of my favourite portraits, some stylised, some snapped.

In portrait photography, one experiences an intimate but brief relationship with someone who is, more often than not, a total stranger. My job is to capture and portray the essence of my subject – a moment of revelation becomes a moment preserved.

When I prepare to make a portrait, I have a rough mental image of what I’m after, and then plan accordingly. Through the choice of location and the use of lighting and sometimes props, I try to create a narrative around my subject. Although the staging can be controlled, the result is often unpredictable – ideally collaborative and engaging, but always challenging.

I was born and raised in Cape Town, and it has remained my base. I remember the exact moment when, as a 12-year-old In 1960, I realised that I wanted to become a photographer: It was when I saw a photograph of Ernest Hemingway by Karsh of Ottawa on the cover of a photographic yearbook. Dramatically lit, the portrait appeared more vivid than life itself, and the creative process involved seemed utterly magical. It still does today.

In 1968 I dropped out of university to work as an assistant to the talented Cape Town photographer Beresford McNally. In the early 1970s I studied filmmaking in London, and in 1975 returned to Cape Town to open a photographic studio. I’ve been lucky to have honed my skills in a pre-digital age that taught me how to master the different camera formats, from large to small, and also taught me the value of good printing.

I was influenced by the photographer Bill Brandt who was a master of composition and chiaroscuro, creating a wonderful sense of melodrama in his stark portraits. He once wrote: “It is part of the photographer’s job to see more intensely than most people do. He must have and keep in him something of the receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time, or of the traveller who enters a strange country.”

In 1978 I photographed the 27-year-old Stephen in front of the old Valkenberg manor house for a magazine article on loneliness. He said: “At university I became intensely aware that while other people had friends to go to, I didn’t. People were enjoying themselves, and I was missing out. I’m now learning fairly basic social skills, things which I probably should have learnt twenty years ago...”

Aunt Kitnooi Johnstone, Churchaven – 1978

This is the queen of the West Coast, Ouma Ellen Barsby, whom I photographed in Churchhaven on her 98th birthday, with a platter of grilled haarders, the staple diet of the West Coast of the Cape. The haarder is a silvery mullet and its flesh is firm and moist and slightly oily and tastes out of this world. The locals, who are mostly subsistence fishermen descended frequently from Norwegian whalers.

From the mid 1980’s Churchhaven, located on the Langebaan lagoon in the West Coast National Park of South Africa, became my second home. I love the drama of a typical winter scene where a strip of pink flamingos seperate a saturated sky from the turquoise lagoon. Nowhere have I seen such a sudden and definite change between seasons: the rough Southeaster of late spring seems to drain the winter lush from the veld, leaving it dry and grey.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was the spiritual leader of the struggle against apartheid. Dressed in his clerical robes, the diminutive Tutu always created a stir when he entered a room, carrying a positive spirit with him wherever he went – one that transformed the mythical and the mystical into a democratic narrative that could be understood by everyone.

He was generous and magnanimous – a real mensch, who helped to hold the country together with kindness and wit. He was also a wonderful person to photograph because he understood the process, and covered his eyes with his hands to illustrate the saying, “See no evil”.

The author and philosopher Rabbi Aidan Steinsaltz was the spiritual leader of the Russian Jews in Israel, and a walking encyclopaedia. When, in 2004, I photographed him in Jerusalem, he expressed the view that the colour pink represented “false happiness”. I know exactly what he meant.

The poet Dara Yen Elerath goes further: “Pink is an unhappy hue … It is the colour of fingernails shorn away, blood dripping from the waxen quick … The colour of harm that lingers on cut shins for days. It is only a tincture of desire, and so carries the least conviction. It is the tint that drifts away unnoticed in the night. Be frightened of pink. Do not think it the innocent color of dresses or barrettes, the blush of areolas, strawberry snow cones, or grenadine martinis. Try, for once, to see it rightly. It is frightening.”

The American guitarist Carlos Santana spoke about his universal sense of religion: “There’s too much slippin’ ‘n’ slidin’, too much shuckin’ ‘n’ jivin’. We need moral rejuvenation. When you put your toe in the ocean it doesn’t matter if it’s the Pacific or the Atlantic, there is only really one sea. So Buddism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism is all the same. If you ask God his religion, what’s he gonna say? Too much slippin’ ‘n’ slidin’, too much shuckin’ ‘n’ jivin’ ...”

There’s an exhilarating moment – a sacred moment – when the composition in my camera somehow rearranges and translates the chaos around me into harmony, captured in the split second when I press the shutter.

In 2004 I photographed the legendary singer Cesária Évora in the foyer of a small three-star hotel in Paris. She kept us waiting for four hours, and on her arrival looked tired from travelling. When we asked her to write something, she couldn’t – she couldn’t read or write. Once in front of the camera, like a true professional, she perked up and started singing me her song Sodade: If you write me a letter, I will write you back … If you forget me, I will forget you ... Until the day ...You come back..

In 2006, I photographed the celebrated jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela for a Mont Blanc lliteracy initiative. In his self-effacing way, he said this about his music: “When people say, ‘I love your music’, I say it’s not my music, I found it here. And whatever is happening to me is like supposed to happen. I think that any artist’s best work, this is my crazy notion, their best work is not originated by themselves. I think, there is some kind of spiritual, some conscious mode you put yourself in so as to receive. Because none of us are original. Like my grandmother said: ‘We didn’t come into the world with anything.’ The less you think that you know, the better you can receive, and the more enthusiastic you can be about what you don’t know.”

The singer, songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and musical activist Johnny Clegg was a great unifier. His trademark blend of Zulu rhythms and Western pop earned him the title of Le Zulu Blanc – the White Zulu, as the French called him. His skin was white, but his heart was Zulu. In a great honour, he was given the name Madlebe, a Zulu clan name which means ‘big ears’. Clegg and his wife, Jenny, had two separate wedding ceremonies, one Jewish and one Zulu. Following his death, his family visited Sipho Mchunu, his erstwhile partner in the band Juluka, to perform a Zulu ritual celebrating Johnny’s spirit crossing into the ancestral world. He had written a song titled The Crossing, about this sacred transition of becoming an ancestor, and continuing to guard one’s family from the afterworld. Among his bestknown songs was Asimbonanga (“We have not seen him”), dedicated to Nelson Mandela and others who had suffered under the apartheid regime. It appealed to the next generation of South Africans to carry on Mandela’s democratic and unifying message. It was banned locally in 1986, but gained worldwide popularity. Clegg was a great South African who helped to pave the way to a better and more unified society.

Hier sit die manne in die Royal Hotel Ek ken mos vir almal ek is almal se pêl Luister ou vrind, daar agter die bar Hoe lyk dit met nog so ‘n doppie daar

David Kramer – poet, musician and actor – has played a major role in preserving South African oral traditions, and his lyrics, often influenced by Bob Dylan and Boeremusiek, have become part of South African folklore. They reflect the sadness and happiness of small-town lives, rugby, and local characters. He is funny, ironic and often political, though seldom in hatred or anger. People love him because he relates to their South African background. His knowledge of the country is unique. For example, he discovered a guy called Hannes Coetzee who slides a teaspoon clamped in his teeth over the string of his guitar to create a tinny twang. He has lit up South Africa with his brilliance and energy.

The Afrikaans rapper Zander Tyler, a.k.a. Jack Parow, has done a lot to make Afrikaans cool, celebrating his origins in Cape Town’s northern suburbs, and exporting the language back to Mother Holland, where he stages his own music festival, Parowfest, to sold-out crowds in Utrecht.

When it comes to his music-making as a 24/7 job, his success is due to staying true to himself and having a way with words that is unique and poetic: “So wie gaan by my staan in die koue oggendryp? Wie gaan by my staan as die donker suutjies inkruip? Wie gaan lê in my arms as die tortelduiwe roep, as die son opstaan op soek na vars bloed?”

(So who will stand by me in the cold morning frost? Who will stand by me when the dark creeps in softly? Who will lie in my arms when the turtle doves call, When the sun rises looking for fresh blood?)

Reflecting his continued belief in family values, he acknowledges the role played by his mother, Ronelle, in supporting his rap career, and salutes his late father, Edwin, in his moving song Tussen Stasies: “So ek trek die kombers oor my kop en lê oop voete ... En stap die lang pad in my pa se groot skoene.” (Between Stations: So I pull the blanket over my head and lie with bare feet ... And walk the long road in my father’s large shoes”)

On 5 April 2006, Nico Carstens, then 80 years old, played his last concert in the Belville Civic Centre. He was the master of Boeremusiek, which he sometimes fused with swinging ‘African music’. His song Zambezi was probably South Africa’s most popular tune of all time and became a number one hit, topping the charts in London for six weeks in 1955 – the longest run until the advent of the Beatles.

At the end of the concert, he was asked: “So, Nico, what have you got to tell the audience about life, from your long experience?” At first, he said nothing. And then he said, “I’ve got nothing to say.”

Bob Dylan’s song Joey could well describe Nico: Born in the year of who knows when.

Opened up his eyes to the tune of an accordion. Always on the outside of whatever side there was.

When they asked him why it had to be that way, ‘Well,’ he answered, ‘just because.’

From being the swankiest South African musician, he ended up living in a single room in Parow, a low-rent area in Cape Town’s Northern suburbs.

There was sadness in the air on the day in 2005 when our team met the tenor Luciano Pavarotti in Jo’burg – Pope John Paul II had died the previous day. Once in front of the camera, though, he was his charming best, singing softly to himself and chatting away. I photographed him in his hotel, the Palazzo Montecasino, and behind him a table in his room was laden with his breakfast, an opulent medieval feast. At the end of the shoot, Pavarotti asked me to hand him my camera, and took a photograph of me. When I use the portrait, I sometimes credit it: “Photograph by Luciano Pavarotti.”

Besides Shakespeare, Athol Fugard is the most performed playwright in the world. He wrote plays featuring ordinary people, mostly South Africans, who find themselves in extraordinary situations, influenced by politics and passion, illustrating human inhumanity at its most raw, and told in a unique voice.

Near Humewood Beach in Port Elizabeth, the absurd sign ‘Happy Valley’ configured in red electric bulbs hangs over a neglected stretch of land where ordinary people walk and play. At night, the sign creates a theatrical atmosphere, but in the harsh light of day the set feels a little sad. Back in the summer of 1990, I decided that this would be the perfect place to photograph Fugard. As usual he was polite and humble, qualities he traded on.

In 1972 I saw the play Sizwe Banzi is Dead when it premiered at the Space Theatre in Cape Town. This two-man play was written by Athol Fugard in collaboration with the actors, John Kani and Winston Ntshona. It opens in a photographer’s studio where a man, Sizwe Banzi, has his portrait taken to replace the picture in a dead man’s pass book, thereby giving him a better chance to get a job and survive. Like so many of Fugard’s plays, it had a relatively simple structure that brilliantly illustrated the hostility and inhumanity of pass books, which all black Africans had to carry under Apartheid.

It was an international success due to its simplicity, humour and humanity, and launched the highly successful international careers of Kani and Ntshona.

In 1975, after returning from a successful run in the United States, Kani was assaulted by police and beaten up so badly that he lost the sight in his left eye.

It’s October in Jo’burg, and the jacarandas are beginning to bloom. With more than 10 million trees, the city of gold is said to harbour the world’s largest man-made urban forest, a fact reflected in neighbourhood names like Greenside and Parktown. The latter is also the home of the renowned South African novelist Nadine Gordimer.

I photograph her in her study, filled with filtered daylight. Her expression is clear and persuasive, with the faintest suggestion of a smile. She’s eighty, and she’s lovely.

Gordimer told finely observed stories about ordinary people, and how politics affected their psychological and moral make-up. Stories of love and loathing, told against the backdrop of her racially divided country. She achieved international recognition, and won the Booker Prize as well as the Nobel Literature Prize.

On 30 April 2004, our team drive from our hotel in Waikiki along the coast to the north of Hawaii, past huge Banyan trees that grow their roots on the outside of their trunks, stretching down from their branches. As they age, each tree seems to become a small forest by itself. In the early afternoon we meet the renowned novelist Paul Theroux.

Theroux’s candour and sense of irony is compelling: “Being unbalanced, dysfunctional and feeling inadequate made me a writer. It made me humble when I realised that I’m not the same as other people. I feel incomplete. When you look at me everything seems fine … but it’s not fine, and I think that people who have created something in this world did so because they felt incomplete. “Having something wrong with me has served me well. In my opinion, certainty has its roots in something that needs to be corrected. The person who is certain is certain almost because he is mistaken, and the only value really is doubt, doubting the validity of something and asking questions. Being certain to me is a form of insanity.” Theroux then asked: “Did all of this make sense?” It did, because it also applied to me.

Lin Sampson, my journalist friend with whom I’ve worked for about 40 years, is known for her prickly, insightful writing – her prose without the con, so to speak. Her impoliteness is also graceful.

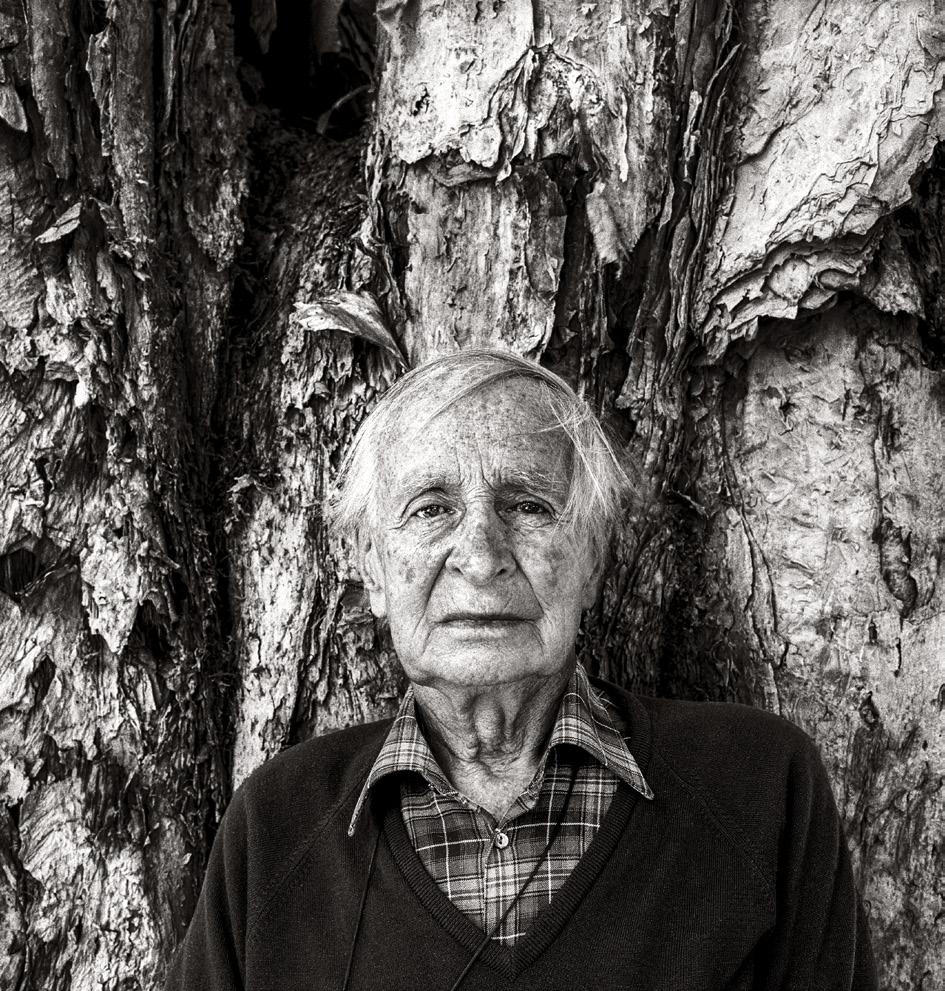

I photographed Sir Laurens van der Post at age 90 in front of a paperbark tree in the garden of the Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town, that seemed to have become his home. He died soon afterwards. He was a Jungian mystic, a hero to many and a close friend of, and spiritual adviser to Prince Charles who, according to British newspapers, he taught to talk to his plants. He was regarded as a national treasure until 2002, when the British journalist and author J.D.F. Jones wrote a biography about him titled Storyteller in which he questioned his honesty and sincerity, and claimed he was a fraud. Nevertheless, Sir Laurens will be remembered as a spellbinding storyteller and a figure of mesmerising charm.

Celebrities typically have busy schedules, so it’s important to avoid being late for meetings, and just as important to avoid being early. When our team arrived half an hour early, waking up the novelist Paulo Coehlo from his afternoon nap at his house in Lourdes, France, he was unimpressed. However, he soon cheered up and demonstrated his archery skills, which is his meditative ritual.

In 1986, while walking the 800-kilometre Camino de Santiago in northwestern Spain, Coelho had a spiritual awakening that would change his life. The following year he wrote The Alchemist, The message of the book is perhaps summed up in a single sentence of hope: “When you want something, the whole universe conspires to help you”. This simple message resonated to such a degree that The Alchemist sold over 150 million copies!

The Maori name for New Zealand is Aotearoa (‘Land of the Long White Cloud’). I became aware of its nasty weather when we arrived in Okarito, the sleepy Westland coastal village where the novelist Keri Hulme lives in an octagonally shaped beach shack. The sea was a dull emerald colour, the sea sand was grey and clammy, and the clouds seemed at a tipping point of saturation.

In 1985, much to her own surprise, Hulme won the Booker Prize for her novel The Bone People. I instantly liked this gutsy, pipe-smoking, engaging woman who calls herself “lucky enough to be a mongrel”, due to her Maori, Scots and English heritage. In The Bone People she writes as if she were exorcising a mythological and intensely intimate vision, mixing Māori mysticism with unadulterated human psychology. It touched a raw nerve in New Zealand. She seemed to have arisen from the land itself, a lifelike representation of salt spray, tangled bushes and stubbornness.

Rian Malan is an average musician and a brilliant writer, but prefers playing music to writing. His book My Traitor’s Heart burst onto the scene in 1990, to the point where he featured on the cover of Esquire Magazine. Few South Africans were ready for its raw truths, but Rian wrote the truth. He had always dealt in it, however hard and difficult this might be. His sense of fairness led to years of investigation into various causes including AIDS, the Coligny mining disaster, and the uncovering of the complex and troubling history behind the global hit song “The Lion Sleeps Tonight”, originally composed by Solomon Linda, a Zulu migrant worker and musician. The song was exploited by the international music industry as well as by Disney using it as part of the soundtrack of its globally successful The Lion King. Thanks to Malan’s expose in Rolling stone magazine, Solomon Linda is now recognised as the rightful originator of a global anthem — and his family finally received a share of the song’s immense success.

In 1958 Chinua Achebe wrote the globally acclaimed novel Things Fall Apart which deals with the influence that 19th century colonial forces and European missionaries had on African tribal cultural life.

The Bard University campus is about 4 hours north of New York by car, where I photograph Professor Chinua Achebe sitting in his wheelchair on his verandah, framed against gauze windows that set the winter scene of naked trees in the misty light. He’s dressed against the cold in dramatic fashion in a black beret with a black-and-white scarf. I come closer and frame his lined face in the square format of my Hasselblad camera. His is a portrait of power and serenity, but also of sadness, for things did fall apart in his native Nigeria where he remains persona non grata.

Isabel Allende is the world’s most widely read Spanish-language author. Her books, notably The House of Spirits and City of Beasts, are marked by magical realism. She’s a feisty and sensual writer, and says: “Writing is like making love. Don’t worry about the orgasm, just concentrate on the process.”

Writing about sex is tricky – it can easily be cringe-making.

Every year, England’s Literary Review bestows a Bad Sex in Fiction Award on the author of the worst sex scene in a novel. The award was established by Auberon Waugh in 1993 to highlight the ‘crude, tasteless, and often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in contemporary novels, and to discourage it’.

In 2010, Rowan Somerville won the award for his novel The Shape of Her. He had written: ‘The wet friction of her, tight around him, the sight of her open, stretched around him, the cleft of her body, it tore a climax out of him with a final lunge. Like a lepidopterist mounting a tough-skinned insect with too-blunt a pin, he screwed himself into her.” It’s this sentence that won Somerville the well-deserved prize, which he accepted with good humour. “There is nothing more English than bad sex,” he responded, “so on behalf of the entire nation, I would like to thank you.”

Business writer Tom Peters’ philosophy is that customers are the individuals using the product, so they will have the best insight of the strengths and weaknesses of it. Communicating with customers will help create loyalty between them and the company. He writes: “Change and change alone comes from one thing. It comes from people who are incredibly irritated with the status quo.”

He’s the only business guru who can turn a coffee spill into a case study on leadership agility. He is a man who doesn’t just think outside the box — he shreds the box, sets fire to it, and then demands that you give a TED Talk about the ashes.

The prolific author and academic Edward de Bono taught people to think. He famously invented the expression “lateral thinking”, and explained it as follows: “It’s the process of using information to bring about creativity and insight restructuring. Lateral thinking is closely related to insight, creativity and humour. All four processes have the same basis. But whereas insight, creativity and humour can only be prayed for, lateral thinking is a more deliberate process. It is as definite a way of using the mind as logical thinking, but a very different way.”

An interesting anecdote about him is that he once installed large mirrors in an office block with slow lifts, after which people waited patiently while looking at themselves, always an enduring hobby.

The novelist Tom Robbins’s house in Seattle was colourful and quirky, and reflected his sense of humour: a huge circus mural of a jungle woman wrestling a snake served as the backdrop for this portrait I took in 2004. His message was simply that people are too egotistical, and take themselves too seriously. “If the German crowds could have loosened up, thrown their sausage skins at Hitler and laughed him off the stage, we might have been spared the Holocaust,” he quipped. No wonder Even Cow Girls Get the Blues became a cult read.

Douglas Coupland is a prolific writer and artist who says he’s “never left art school”. His studio in Vancouver is neat and tidy, almost antiseptic, with oversized washing-powder box sculptures and life-sized toy soldiers guarding his seemingly solitary existence on Shampoo Planet (the title of one of his novels). “Remember,” he writes, “The time you feel lonely is the time you most need to be by yourself. Life’s cruelest irony.” His sensible advice: “Figure out what it is you don’t do very well, and then don’t do it.” And his motto is “Work is more fun than fun.”

“In some silent invisible vestibule of the brain, the images are caught, apprehended, interrogated, and sent, brushed up, to the resting place as a horse. The sheet of paper is simply a visible extension of the retina, an emblematic demonstration of that which we know but cannot see. Our projection, our moving out toward the image, is an essential part of what it is to see, to be in the world with our eyes open.” – William Kentridge

I photographed the artist Beezy Bailey for the London Sunday Times in front of a large painting. Its floating figures reminded me of Marc Chagall’s work, with an added sense of playfulness. If I had to sum up his work, it would be “light of heart” – he paints from the heart in a playful way.

Now middle-aged, Brett Murray somehow remains the main contender for the title of the enfant terrible of South African art. He showed a lot of spunk (so to speak) by painting the presidential prick, thereby rubbing the political establishment up the wrong way. Today more than ever, it’s important that art should retain its ability to offend.

Sanell Aggenbach moves seamlessly between painting, printmaking and sculpture. Her work is subtle, deals with memory, identity and history, and walks a tightrope between nostalgia and criticism, probing political and cultural undercurrents through the language of domesticity. Her paintings are enigmatic— muted in tone, and referencing old photographs and personal relics. They evoke a kind of fading memory.

On my 11th birthday I saw my first nude painting of a woman. I didn’t know what a naked woman looked like before I saw Birth of Venus exhibited in the Garlicks department store in Cape Town in 1966. It was painted by Vladimir Tretchikoff, and introduced me to the art world. Thanks Tretchi, on both counts.

A few years later I saw the flamboyant Russian painter speeding along a highway in an pink open-top Cadillac, with his white hair flowing in the wind. Next to him, dressed in a white fur coat, sat his wife, Schmoogie (little dog in Russian). This was swank and glamour that Cape Town wasn’t used to.

In 1996 Tretchikoff ‘s most famous painting, Chinese Girl, had just turned fifty when the journalist Lin Sampson and I visited him and the charming Schmoogie (real name Natalie) at their home in Bishopscourt, Cape Town. His house was called “Tretchi”, written in pink neon lights. Although it was early in the morning, the champagne flowed, and I immediately warmed towards this wily old raconteur.

This romantic man showed no bitterness or loss of vanity over the fickle art establishment’s shoddy, hot-and-cold treatment of him through the years. He was a great show-off, but I believe the patriotic Tretchikoff would have been proud of the posthumous celebration of his art at the National Gallery in 2011.

Nazdarovie, Tretchi! Here’s to Venus rising from the lurid turquoise sea, water running in rivulets over her naked, waxy body.

In 2009, I accompanied Nandipha Mntambo to Maputo in Mozambique to document her performance piece, Praça de Touros. In an empty arena, dressed in a cowhide matador outfit, she attempts to take on the persona of the bullfighter and that of the bull. She explains: “For a long time I had been thinking about fighting against myself, and how to express this inner conflict.”

Sculptor, body builder, painter, performer, exhibitionist and world yo-yo champion Barend de Wet had a simple motto: ART = LIFE = ART. He was the complete artist in the sense that every step he took or move he made was regarded as part of a personal creative process. Claiming that his body was art, he loved stripping naked in public. And in the end people didn’t notice his nudity (no nudes is good nudes). I photographed his proudest creation, his new-born son Ben, and he then sold the picture printed as post cards. He died far too soon in a car accident in 2017.

‘‘I am your relative,”Marc Quinn wrote on his hand when asked to write a message to mankind. I photographed him through the glass door of a fridge that houses the frozen cast of his son’s head, sculpted from his own liquidised placenta. Quinn explores “what it is to be human in the world today.” He’s concerned with the essence of our physiological being: our bodily functions, identity, and our DNA.

The artist Gaby Cheminais once wrote a beggar a cheque at her front door when she had no cash on her – an act of eccentric kindness, to say the least.

Her daughter Sascha now lives in New Zealand, where she settled after surviving a few armed robberies at work in her native Cape Town. In this portrait, Gaby hugs Sascha in a protective way, but the mother and daughter are divided on the horizon by the grey sky meeting the rough sea, drawing a line of separation between them.

Talking about relationships, the lovely film director Jane Campion (she won an Oscar for The Power of the Dog) claimed that after the age of forty she felt that she had become invisible to men. She could have fooled me! She wrote ‘INVISABILITY’ on the palm of her hand and held it up, covering her face. However, she was charismatic, engaging, and easy to photograph, because she had imagined what I wanted.

I had seen Gillian Anderson play strong women, like the FBI agent Dana Scully in the X-Files. So when, in 2004, I met her at the Royal Court Theatre in London, I was amazed at how tiny she was. Beautiful, with large bright eyes, she’s a brilliant actress who conveys a sense of intelligence and aplomb when portraying larger-than-life women such as Wallis, Duchess of Windsor, Edwina Mountbatten, Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, Margaret Thatcher in The Crown, andmore recently, the BBC reporter Emily Maitlis in Netflix’s Scoop, a fictional dramatisation of the infamous Newsnight interview with Prince Andrew.

Despite her breathtaking beauty, actress Natascha McElhone is quite grounded as she jokes, “Yes, I went to drama school, but I also know how to fix a leaky sink and survive a bad first date.”

She says: “Never begin with results. They will appear as a logical outcome of what has gone before. If you start off wanting the end result of something, you lose sight of the journey, which is really the whole point of life and living. Enjoy the journey. And if something comes out of it, then all the better. But if it doesn’t, the journey’s the most important thing.”

“I have only slept for four hours in the last 48, so I’m brain-dead.” announced Philippe Starck when our team arrived at his Paris studio. “I don’t know why you are here – my secretary told me, but I understand nothing.” Things had got lost in translation.

For an hour, the world’s most famous designer played, danced, sang and performed Kung Fu tricks – spontaneous, funny, and always serious: “Remember that life on earth started nearly four billion years ago at a time when we were bacteria. A little bit silly, even very silly. When we became fish, we lived in complete happiness. One day we had feet, and we became frogs. We climbed up to the land. We became the super frogs that we are today. We went to the moon. We’ll perhaps go to Mars. And this is unbelievably magnificent! This is pure poetry. We are mutants.”

He asked me for a Polaroid (a small, instant print taken as a test before shooting on film) to give to his girlfriend. “Thank you Jac,” he said while shaking my hand vigorously, “You have helped my sentimental life.”

The British architect Richard Rogers was known for “celebrating the components of the structure”, which is well illustrated in the Pompidou Centre he designed together with the Italian architect Renzo Piano. When in the mid-1980s I saw the building for the first time, I was amazed by its dramatic, high-tech design – its skeletal structure was on the outside, with exposed tubular escalators and colourful ductwork. It looked like a giant Meccano set – a brave new building that turned the rules inside out.

The lovely Marion Jones is widely regarded as the greatest female athlete of all time. In 2000, she became the first woman to win five medals at a single Olympics – three golds and to bronzes. Sadly, in 2008, four years after photographing her in Raleigh, North Carolina, she was sentenced to six months in prison for lying to federal investigators about using performanceenhancing drugs. The International Olympic Committee also stripped Jones of her medals.

Gary Player is regarded as one of the greatest golfers of all time. He was in good shape when I met him on his stud farm in Kwazulu Natal. He slapped his tight, flat stomach, declaring: “I do a thousand sit-ups a day, and I’m probably the fittest seventy-year-old in the country!”

After Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, he and Player became close friends. When they met for the first time, Mandela he told Player: “If I have hatred and non-forgiveness in my heart, I’ll be like an apple – green on the outside, but rotten on the inside.”

The cricketer Ian Botham could be the poster boy for tough English guys. Nicknamed Beefy, he’s a real chap – a chap with a big heart. In 1997, while receiving treatment for a broken toe, he took a wrong turn into a hospital’s children’s ward where he learned that some children with cancer had only weeks to live. He started doing fundraising work, including a 900-mile trek, and has raised more than £12 million for charity.

The Canadian Wayne Gretzky is a good-looking ‘guy next door’, with no outstanding physical features that make him the best ice hockey player of all time. He says: “I couldn’t beat people with my strength; I don’t have a hard shot; I’m not the quickest skater in the league. My eyes and my mind have to do most of the work.”

They don’t know what we know’ is the cryptic motto of Dricus du Plessis, the current UFC Middleweight Kickboxing Champion of the World. I asked Dricus to adopt a defining facial expression. He looked away, turned his head back towards me, and, with a hint of malevolence, raised his eyes, but with a suggestion of a smile.

In a 1995 World Cup match played at Newlands in Cape Town, I witnessed the New Zealand rugby hero Jonah Lomu crush his English opponents. They fell like rags off the unstoppable Number 11 as he established himself that day as the greatest wing ever to play the game.

I photographed him in Auckland nine years later, soon after a kidney transplant. He was a shadow of his former self, and looked vulnerable when he took off his shirt to show me the number 11 tattooed on his chest.

He was a gentle giant … until provoked! He told us how, at age 15, he had counterpunched his father after suffering years of abuse, in what sounded like a Once We Were Warriors home life.

When we left, there was a sense of melancholy in the air as he drove his black Jeep into the gloomy magenta twilight of Aotearoa – the Land of the Long White Cloud.

Timing is everything; also knowing when to quit. When I watch the Rolling Stones acting like teens on stage, I feel embarrassed for their sake, and want to shout: ‘Stop and get off the stage while you can’. The World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Lennox Lewis knew when to quit – with face, senses and respect intact.

Lewis doesn’t fit the stereotypical boxer profile -- he’s a excellent chess player, playing up to four times a day. He once told the Celebrity Talk Show host Joe Rogan that he often plays the regular dudes at Washington Square Park, some of whom are masters. Anyone can challenge him online: his username is inter2000.

–

After witnessing death and injury among comrades, he decided to study medicine, and later turned to biomedical research. While serving in Vietnam, the biotechnologist Craig Venter tried to commit suicide by swimming out to sea, but changed his mind along the way. In 1990, he revolutionised biological science by independently mapping out and sequencing human DNA, known as The Human Genome Project.

In 1990, he revolutionised biological science by independently mapping out and sequencing human DNA, known as The Human Genome Project.

According to Venter: “The complexity of life in our society has a chance at being helped by modern science. It gives us a chance just to understand where we fit into the continuum of life. We found that the variance in genetic code between any two humans is extremely small. This concept of race is clearly a social construct. There is no scientific definition of race. It’s a social definition. There’s only one race, and it’s the human race.”

Something magical happened on 7 March 2004 when I photographed Grandmaster Garry Kasparov in a hotel in Madrid. A gust of wind blew the curtains sideways, causing the most beautiful soft sunlight to flood his face. Kasparov looked straight at me with confidence, and I knew I was taking a good portrait.

He started playng chess when he was five years old. He learned the moves from his mother, who told him he would he would one day be the World Chess Champion. “If not you, then who?” she asked. Like a good Jewish boy, he believed her.

“There is no one who can share your responsibility, he adds. “It it is your responsibility, you must carry it and be responsible for your actions. At the end of the day, we all are being challenged by our destiny. And it’s up to us to make all the difference in this life. If not you, then who?”

Marthinus van Schalkwyk is a professional politician who chopped and changed his allegiance in the winds of change. An apartheidera intelligence operative, he succeeded F.W. de Klerk as leader of the National Party, rebranded it unsuccessfully as the New National Party, and then joined the ANC. He was given the nickname Kortbroek (short pants) because of his boyish looks. When I photographed him in 1995, I was surprised by the focal point of his office -- a print of an English hunting scene, hanging over the fireplace.

After the successful 1995 Rugby World Cup tournament in South Africa, Leadership magazine commissioned the well-known Afrikaans author André P Brink to write a piece about our victory and the role played by President Nelson Mandela, who, in a gesture of national unity, dressed himself in the Springbok rugby jersey with the number 7 on its back, as worn by our winning captain, Francois Pienaar. For the studio portrait, we painted Brink’s face in the colours of the national flag, as proud fans do, leaving half his face recognisably exposed.

On 22 March 2004, the Palestinian leader and a founder of Hamas, Ahmed Yassin, 67, was assassinated in Gaza City. When our team arrived at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv the following day, security was on high alert. Our producer told a security officer that the purpose of our visit was to photograph the Israeli president, Shimon Peres. This provoked a lot of suspicion – we were interrogated for four hours, and our equipment was thoroughly searched.

Peres was known as a warrior for peace, due largely to his understanding of the role imagination plays in life. He said: “People prefer remembering to imagining. Memory deals with familiar things; imagination deals with the unknown. Imagination can be frightening – it requires risking a departure from the familiar. We should use our imagination more than our memory.”

He was also respected in Palestine – as a goodwill gesture, the Palestinian leader President Mahmoud Abbas attended his funeral in Jerusalem in 2016.

President F.W. de Klerk will mainly be remembered as the person who unbanned South Africa’s liberation movements, negotiating himself out of power in the process. This goes against the grain and instincts of almost all politicians. A religious man, he called his transition a Damascus Road experience.

It was a summer’s day in early 1995 when I photographed President Nelson Mandela in the cool, granite-clad courtyard of the Union Buildings in Pretoria. In the heat of the midday sun, a Highveld storm was brewing, ready to crack the saturated sky. The president arrived in the ‘revolution red’ Mercedes Benz that the East London factory workers had built for him, and greeted me in his familiar and disarming way: “Hello, how are you?”, as though he remembered me from a previous meeting.

It was great to have had a leader you’re proud of – someone whose wisdom you trust, and whom you can consult in your imagination when you have a problem to resolve. You ask yourself: “How would Mandela deal with the situation?”

That’s as good as it gets.

THE QUEEN, THE VICE PRESIDENT AND I

THE QUEEN, THE VICE-PRESIDENT AND I

In 1947, the young Princess Elizabeth was photographed driving past the Board of Executors building in Cape Town. Forty-eight years later, in 1995, I was commissioned to repeat the picture. I was meant to photograph her – now Queen Elizabeth II – in her car after leaving a service in St George’s Cathedral, opposite the Board building at the top of Adderley Street. I managed to jog next to her car – security was surprisingly slack – and got my shot.

Afterwards, I photographed then Vice-President Thabo Mbeki while he was chatting outside the cathedral for the cover of Leadership magazine. Two shots in one.

CARVE HER NAME WITH PRIDE

I photographed Fezeka Kuzwayo, a.k.a. Kwezi, performing a one-woman play at the 2000 World Aids conference in Durban. She told me she had been infected with HIV/AIDS by a priest who had raped her. In 2005, she also laid a charge of rape against Deputy President Jacob Zuma.

During the ensuing trial he said the sex was consensual, and added famously that he had taken a shower afterwards as protection against infection. Zuma was acquitted, while Kwezi had to flee the country. She died in exile in 2016.

Is Cyril Ramaphosa laughing all the way to the bank? He seemed to move from trade unionist to billionaire in record time. Later, when he had become president, it was no laughing matter when he was claimed to have covered up the theft of more than half a million dollars hidden in a sofa on his Limpopo game farm, Phala Phala.

I photographed the then businessman Ramaphosa in 2006 for a Mont Blanc pen literacy initiative. He was charming, and told his secretary to watch us so that we could not pinch anything from his office. I asked him whether he was planning to run for president, and his answer was typically noncommittal. He has always played his cards close to his chest, which I suppose will be his legacy.

MINISTER OF INTEGRITY in 2016, together with then Minister Derek Hanekom, I was delighted to receive an honours medal from our old school, Jan van Riebeeck High – mine for photography, and his for active politics.

During the politically turbulent 1980s, Hanekom was imprisoned for his antiapartheid activism. He experience had not hardened him, but had made him even more dedicated to reconciliation and nation-building. Despite the political storms that raged around him, he remained a voice of reason, promoting transparency and, most importantly, integrity.

I photographed Queen Noor of Jordan at the World Parks Congress in Durban in 2003. It focused on the preservation of protected areas worldwide, a subject close to her heart. She’s also a founding leader of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017, and is deeply involved in the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

During our shoot, the self-assured Queen Noor confided to our stylist, Tanya Tyler, that her face and body had been nipped and tucked.

The Republican US Senator Richard Luger was known as a humane conservative who campaigned against the policy of apartheid in South Africa as well as the use, production and stockpiling of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons after the Cold War. Measured, principled, and more focused on policy than performance, he was the type of politician we rarely see today.

The chain-smoking Chinese dissident Wei Jingsheng suffered enormously at the hands of the Chinese authorities, spending a total of 18 years in prison for expressing his democratic beliefs. Imprisoned after the Tiananmen Square crackdown, he was kept in solitary confinement for years, unable to exercise or go outside. He was deprived of basic health care while suffering depression and heart disease.

When I photographed Wei in 2004, he spoke only Chinese, while I spoke none. But we managed, I’d like to believe, to communicate quite well. Translated from Chinese, his message reads: “Many people are like that African animal called a chameleon. They adapt to the circumstances. This is a good tactic for surviving, but its bad for the course of the world.”

The human rights activist Saad Ibrahim is dressed in an old-fashioned blazer and cravat when we meet in his small apartment on the Columbia University campus in New York. Following international pressure, he has recently been released from an Egyptian jail where he spent three years in solitary confinement for his pro-democracy activities.

He tells a moving story: “The only thing that I could see from my prison cell was a tree that looked so big to me, and when I was released, I looked at it and it was very small. But you know, in prison everything is distorted, so I used to look at that tree, and it was magnified in my imagination.”

He reflects: “Peace and democracy are two sides of the same coin. In order to have peace in any region of the world, in any society, torn by civil strife, torn by hatred, you must have justice and democracy. My fight is for democracy, peace and development, because these three ensure human dignity for all.”

The South African journalist Aggrey Klaaste was slim in stature, but bold and robust in his writing. He was a mensch and a voice of conscience in a time when South Africa desperately needed one. What set Klaaste apart was his conviction that journalism had the power to inspire and change people in addition to informing them.

Although harassed and imprisoned by the National Party government, he launched his nation-building initiative in 1988, when he became editor of Sowetan newspaper. Its aim was the upliftment of black communities that had suffered under apartheid. Supported by business, the initiative recognised and rewarded community builders who had helped to uplift thousands of people. After his death, his fellow journalist Thami Mazwai wrote: “This gentle, caring intellectual resolutely braved opposition from all sides to triumph in the end.”

In the mid-1980s I photographed the Reverend Allan Boesak outside his house in Belville, Cape Town, which looked more like a fortress that a home. Nattily dressed, with a thin tie and a white hankie in the top pocket of his tailored check jacket, the struggle icon also looked more like a CIA agent than an ANC leader. As usual, he was brimming with self-confidence. But his self-deprecating humour, also delivered in his whiny preacher’s voice, was infectious, and incongruous for someone with such a big ego.

He became a sacrificial lamb when he gained too much power within the ANC. Sadly, the country lost a great leader when he went to prison. Boesak, I’d like to believe, was not a calculating thief, but had rather mismanaged some of the funds that he had received.

Deluxe owners Carl Wessel and Judd Nicolay are the rock ‘n roll stars of coffee in the Cape. In 2009 they started roasting in a tiny shop, the size of a garage, in Church Street, Cape Town, and soon gathered a devoted following. They’re known to treat their loyal staff like family. Sometimes Carl wears a suit that looks as though he might have slept in it. And I’ve seen Judd delivering coffee to his clients in his Range Rover. These boys have style.

The talented Alwijn Burger, a.k.a. ‘Blomboy’, ran the Gentlemen’s Flower Arranging Club for chaps keen on honing their skills in floral art. According to Burger, “Nothing adds more panache to a gentleman’s appearance than a simple flower worn on the lapel”.

Kobus van der Merwe is the antithesis of a ‘rock star chef’. He is humble and creative, and scoffs at the idea that his restaurant, Wolfgat, was voted the best in the world, adding: “It’s an absurd and meaningless title.” He runs Wolfgat with a small footprint and uses only local foodstuff, while his staff, mainly women, have equal rank. The food they produce is sublime.

Rick Stein is a storyteller, and his is the story of fish, simply told with intellect and wit. He cooks fish effortlessly all over the world for his wholesome television programs. He got his first big break by appearing on one of Keith Floyd’s TV shows, and refers to him as a mentor whose legacy he is proud to continue: “What Keith did was bring food to men, and all I’ve done is to carry on doing the same thing, so I owe him a great deal. But I think he got a bit pissed off. I guess I was the young upstart.”

Chef Reuben Riffel impresses with his humility and ease of engagement, characteristics he shares with fellow chef Kobus van der Merwe. They had a mentor in common, the talented chef Richard Carstens. Instead of celebrity chef, Reuben’s lack of egotism makes him more of a storyteller of food … in his mother tongue of Afrikaans, so to speak.

WINNER

Chef Luckson Mare of The Living Room in KwaZulu-Natal is one of a new generation of African chefs finding their voices on the global stage. He’s been crowned as the 2024 winner of the Pellegrino Young Chef Regional Final for the Africa, Middle East & South Asia region. He won with his signature dish that included the foraged indigenous Matungulu (Natal Coastal Plum). “I’ve taken the humble root and paired it with duck, which, to me, symbolises fine dining.” He adds that using the plum is a tribute to his mentor, Chef Johannes Richter, who profoundly shaped his approach to cooking.

I photographed chef Jan–Hendrik van der Westhuizen in a private jet on our way to the Kalahari. He’s flying high – his upward trajectory since winning a Michelin star has been nothing short of remarkable. He’s unsoppable. Like the retaurant industry my industry is fuelled by drugs, sex and ambition. No one I know matches Jan–Hendrik’s drive. From the Cape to the Kalahari he’s left a focused footprint of brand innovation. His persona he is the brand – building a cool underground cellar in the middle of a hot desert is clever. Serving bobotie and biltong in France is clever. The guy is smart!

Jan-Hendrik van der Wsthuizen, chef – 2018

With his self-deprecating sense of humour Vusi Ndlovu must be the coolest chef in Cape Town. I met him and his partner Absie in the autumn of 2024 at Wolfgat restaurant where they cooked with Kobus van der Merwe – the three of them a true triangle of talent. Wolfgat is a small restaurant with a big heart. Carling Black Label is introduced and compliments effortlessly wines from the dry West coast to toast and celebrate the event. The menu –‘n spyskaart van plesier – reflects the local botany: crowberry and kelp; soutslaai and sea lettuce. From the cold Atlantic: abalone and oysters; limpets, mackerel and mussels; tjokka and bokkom. And then the classics: askoek, herebone and klipkombers. – Kobus’ cooked oyster served on a pebble blanket. Vusi plays with fire - his robust rare beef rib eye with sweetbreads follows. Cries and whispers of deliciousness echoes in the ancient Wolfgat cave below. Africa smiles.

Vusi Ndlovu, chef – 2024

Nobuyuki ‘Nobu’ Matsuhisa is one of the world’s most famous celebrity chefs. After a stint in Peru at the age of 24, he started a cross-cultural food experiment by blending Japanese techniques with Latin American flavours. He added jalapeño to yellowtail sashimi which became an instant culinary success. He says: “You know how kids dream of being soccer players or actors? Well, my dream was to be a sushi chef. The two most important days in your life are the day you are born, and the day you find out why.”

Sydney Moonsamy spent 35 years as a waiter at the Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town – a life dedicated to service. He was also the highly respected ‘tea master’ or ‘tea sommelier’ at the hotel where he created the signature blend for their famous tea, mixing Ceylon, Assam, Darjeeling, Keemun, Kenya, Yunnan, and rose petals from the garden. The hotel’s high tea was made famous by the Duchess of Bedford as a means of combating her late afternoon “sinking feeling”.

This is Stephanie wearing Vivienne Westwood at her most tigerish. Stephanie arrived in Cape Town for a short stay with a container full of clothes. One dress opened up to reveal a box of white doves. As the designer Louis Feraud once said, “To be truly chic, a woman must dress with a little humour.”– Lin Sampson

Day for night is a cinema technique in terms of which a subject is correctly lit and the surroundings and background are underexposed and blue-filtered, which creates an impression of evening. I used this technique when I photographed Virginia Springett, who walks the streets of Sea Point plying her trade. She is in her seventies and, as a no holes barred prostitute, lives from hand to mouth.

AIn the early 1960s, I often accompanied my father to a fish market in an area of Cape Town known as District Six, located in the heart of the city below Table Mountain. It was a mixed-race neighbourhood, established about a hundred years earlier as a community of freed slaves, merchants, artisans and immigrants.

On 11 February 1966, the white nationalist government of the day passed a law declaring District Six a whites-only area. The houses were subsequently bulldozed and the inhabitants were relocated 25 kilometres outside the city to wind-swept, sandy scrubland known as the Cape Flats. Cape Town not only lost a vital chunk of its population and architecture, but also lost its soul.

Today a few mosques and churches dot this wasteland where a spirited community once lived. According to ex-resident Ruth Jeftha, “District Six was all about food, we didn’t have much, but food brought us together. If you had kids to feed, you would go to your neighbour and ask for food.” Linda Fortune remembers the smells of District Six: “I used to walk up Hanover Street on my way home, and could identify what different people were cooking. I truly miss the food, the smells of District Six.”

Huis Kombuis (Home Kitchen) is a term coined by a group of 22 former District Six residents who participate in a memory workshop program with team leader Tina Smith, curator of the District Six Museum. It’s a design project where storytelling, performance and traditional craftwork – including embroidery, sewing and appliqué – are used to document the area’s former culinary life.

A few years ago, Tina invited me to work with her on a food book with the working title Huis Kombuis: The Food of District Six. It includes the testimonies of her group, their recipes as well as their portraits, decorated with their embroidery. It is a unique cookery book in the sense that it records and celebrates the food of an absent society.

Huis Kombuis: The Food of District Six was published in late 2016. The portraits were also exhibited at the District Six Museum, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the notorious event when District Six was bulldozed.

MARION ABRAHAMS-WELSH

“I remember my grandmother and my mother cooking right through the night. We had a huge, black cast-iron pot. In that pot, my grandmother cooked a small pig, a whole one, together with the turkey, the roast beef and the roast potatoes. Everything would go onto the table at lunchtime, the vegetables and the beetroot salad.”

Abrahams-Welsh with her Spode plate – 2016

“Despite leaving school in Standard Two, I wanted to achieve something in life and my employment in differetnt jobs gradually improved my life. During my childhood I participated in the klopse, played netball and coached a women’s netball team. I was involved in starting an all-male drag queen netball team.”

“ We had a lovely kitchen. It was my weekend job to put wood or coal in the stove. Sometimes we ran out of wood. We went to this furniture factory and came home with bags of wood for the fire. We cooked our best food on that stove.”

“We had a special recipe for the different kinds of curry. We weighed everything before it went into the pot. That was how we catered for our customers. We gave them the very best. My brother-in-law was very particular like that.”

“Sunday wouldn’t be a Sunday without chicken and nowadays they have this masala chicken. In those days it was just pot braaied chicken. So ja, I looked forward to Sundays, you slaughtered your own chicken.”

I photographed the gentle-spirited ceramicist Marjorie Wallace wearing an indigo shirt at a Design Network Africa workshop in Accra, Ghana. in 2016. Blue was her sacred colour. To me, her work has an African Zen quality due to the use of bold patterns and the colour blue. While she might not have sought the spotlight, Marjorie Wallace has left a collection of work that, like her own person, speaks with dignity and quiet strength.

Stephen Burks is probably the world’s most exciting industrial designer. He has a democratic attitude to design in the sense that he believes the artisan’s input is just as important in creating the quality, look and feel of the final product. An intrepid traveller, Burks has worked with hundreds of artisans in many countries, especially in Africa, in the course of his project titled ‘Stephen Burks Man Made’, bringing those cultures to bear on contemporary design. He explains: “I travel to make the invisibility of their cultures visible through my work – to build a bridge from their craft traditions into the future.”

I met him in Accra, Ghana, while photographing a Design Network Africa workshop hosted by Trevyn and Julian McGowan. The subject of racial stereotypes came up in our conversation, and Burks quipped that an interviewer once referred to him as “the Barack Obama of design”.

The subtleties of daylight streaming through a window is almost impossible to replicate with artificial light – the rich colour, the moulding of the light on a face is just different. Rembrandt’s paintings are a testament to the power of natural light.

I used natural ‘north light’ for my portrait of the furniture designer and crafter Kweku Forson in Accra, Ghana. He has a timeless face that radiates contentment, confidence and sensitivity, seemingly reflecting everything that’s good about Africa

Heath Nash uses “other people’s rubbish” and makes it shine by ‘upcycling’ and transforming it into beautiful lights that are sculptural and playful. In this portrait, taken during a Design Network Africa workshop in Accra, Ghana, he’s clutching his ‘leafball’, a beautiful light, and his first commercially successful product that put him and his team on the international design map.

In 1950, before leaving for London to join the Sadler’s Wells School of Ballet, Johaar Mosaval had to perform a dance routine for two Imams to decide if ballet was compatible with Islam. They were blown away by his flair, and gave him their blessings. Mosaval had been studying with Dulcie Howes at the UCT Ballet School where he had to stand at the back of the class, separated from his fellow students because of apartheid.

He went on to join the Royal Ballet Company, and in 1953 he danced a solo in Benjamin Britten’s Gloriana for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. He describes the experience as the highlight of his life: “That night, the whole opera house consisted of every king and queen in the world. It was the most magnificent, spectacular audience ever, and dancing on stage you could see the flickering of the tiaras and the diamonds that were worn that night. I was floating on Cloud Nine.”

The words “You’re too tiny to succeed as a ballet dancer” were among the many challenges Johaar had to ensure and surmount. Among with childhood poverty, racial discrimination and parental disapproval, this gave him the iron will he needed to succeed.

And his success was phenomenal, for by the mid-1960s he had moved up the ranks to senior principal dancer, partnering such famous ballerinas as Margot Fonteyn and Svetlana Beriosova. He danced with Rudolf Nureyev, and worked with famous choreographers like Kenneth MacMillan and John Cranko. Due to touring with the company, he gained international recognition as a brilliant character dancer with impeccable technique. Among others, he danced famously as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Jasper in Pineapple Poll and the Bluebird in The Sleeping Beauty

I photographed Johaar in District Six, not far from where he grew up in a thriving community, long before the place was demolished into a wasteland of sorrow. But, at the age of 93, this sharp and beautiful man shows only contentment as he recounts stories from his past, filled with miracle and wonder.

By the summer of 1978, most of Cape Town’s District Six in Cape Town had been bulldozed, in the name of the racial ideology of apartheid. A community had been destroyed and a wasteland created that still serves as a stark reminder of the injustices of the past. They’d ripped out the heart, but somehow the spirit of the place remained – manifesting itself in the theatrics and defiance of a spontaneous drag queen show I was fortunate to witness.

In the harsh summer light, with the pavement their catwalk, Madame Two Swords and the Girls strutted their stuff in front of a crowd of cheering kids. Street theatre at its very best.

TToday, drag queens are freer to live out their fantasies than in the 1970s when, for example, Sandra Dee was arrested and imprisoned for ‘dressing up as a woman’. They’ve become more mainstream, but also less risqué.

I worked with the artist Nina Milner who recently launched and curated the Kewpie Legacy Project, a vehicle for selling merchandise and portrait prints of drag queens, to benefit the District Six Museum.

The actor Pieter-Dirk Uys has helped South Africans to survive and change by exposing them to the ridiculous side of apartheid. He has been called The Most Famous White Woman in South Africa. He is kind, friendly, and massively energetic. At 80, he is still dreaming up new ideas, and his alter ego, Tannie Evita Bezuidenhout, is still up and about like any Pretoria housewife, obsessively house-proud, plastered with makeup, and entirely reliant on a fleet of maids.

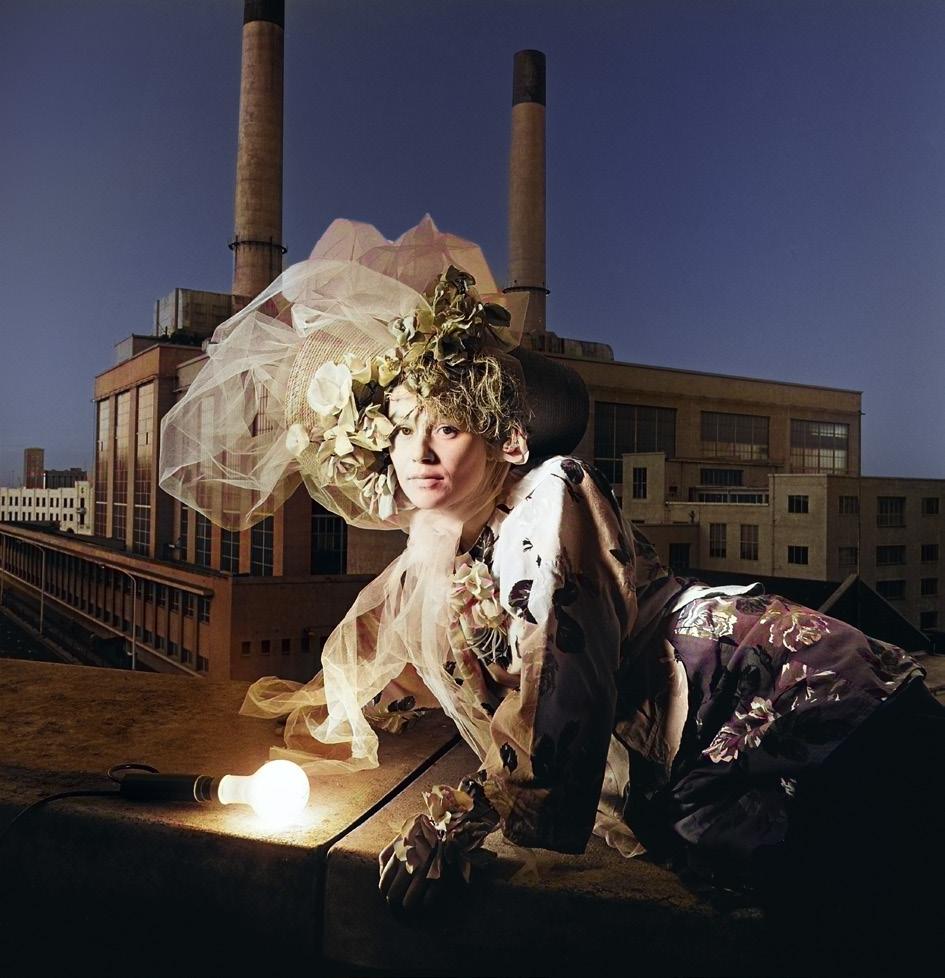

IIn the mid-1980s, Vula magazine had a shoestring budget, but it was fun to work for them, as one had complete creative freedom. I photographed the young, bright and gracious actress Terry Norton at the old power station in downtown Cape Town, lit with a single electric bulb. I recently I colourised the photograph in Photoshop. Terry went on to a great acting career on stage and in film, working with the late Irish novelist and playwright Edna O’Brien and actors like Michael Caine, Juliette Binoche and Forest Whitaker.

Uys in his role as Tannie Evita Bezuidenhout – 2000 Terry Norton, actress – 1985

I photographed the fashion designer Lukhanyo Mdingi in 2016. He is inspired by the vibrance and aesthetics of small South African towns, which has led him to source traditional fabrics and apply them in a modern manner.

In 2019, Mdingi became an international player when he presented his first collection to an international audience at Men’s Fashion Week in New York.

In 2019, I photographed Marsi van de Heuvel in the vaults of Zeitz Museum in Cape Town. She uses a fineliner to make marks on paper. She explains: “One stroke holds a brief moment of energy and intention.” The use of this meticulous technique gives her portraits, landscapes and abstract fields a depth and radiance which encapsulates the meditation and obsessive effort that went into creating them. In the presence of her work, I felt a similar sensory experience I had in the Rothko room of the Tate Gallery in London, a sense of connection to something bigger than myself.

The suburb of Rugby, located between the N1 and the notorious Koeberg Road, is trendy Cape Town’s bleaker terrain – its zef side, as the rapper Jack Parow would sayu – the unfashionable area that’s not earmarked for gentrification. Thank God

After living in an old Railways cottage near the Cape Town harbour for a number of years, it makes sense that the late Aida Uys and her partner Braam Theron chose Rugby to make their next home, for they never followed trends. They set them. To me, they were the most stylish couple the Cape has ever seen. Period.

Style is really undefinable and yet tangible, for it touches your senses. I feel I can sense, almost instinctively, when I meet someone with style. It’s not a big deal, it’s simply being aware as a photographer. It’s my job.

I met Aida during the 1980s as she got off her black Triumph motorbike. She was wearing an embroidered silk blouse under an old leather jacket, a man’s khaki trousers with turnups, Wupperthal boots, delicate gold jewellery and vintage leather gloves, and her hair was in a bun. On the back of the bike was a basket that Braam had made for her to carry Ysbeer, their cross wirehaired terrier, her travel companion wherever she rode.

Braam and Aida collected stuff, lots of it, tons of it. Their house was filled with objects, some chosen for their usefulness, some for fun and some for sheer folly. There were anglepoise lamps, model planes, coins, compasses, masks, telescopes, bangles, tools, ropes, helmets, and many, many leather suitcases. And there were gems like a glove finger stretcher (honestly), a peach peeler, a boot button hook ...

Braam rents out props to the film industry with a quirky inverted economy of scale, which he explains as follows: “The more you rent, the more you pay. If you want to rent one coffee flask you pay, say, R30, but if you want 40 flasks - which I have in stock – you pay R60 each, for the chance of you finding 40 of the same is very small, so you pay more.

Braam was really Aida’s romantic handyman. Because Aida took tea brewed from a pot (tea bags were strictly non-U), tradition dictated that Braam would make her a tea strainer for every birthday. This tender detail is what made their liaison so special, so complementary.

Birrie le Roux, who works in the film industry, was a close friend of Aida’s. She defines Aida’s spirit in a succinct and insightful way: “To live in such an overstimulating environment, where you add new things to it all the time, you have to have a place in your mind where there’s a quiet calmness. I think Aida always had that. She was naturally serene. And she had a very strong sense of her own style and who she was – and I think that Braam enhanced that.

Birrie le Roux, who works in the film industry, was a very close friend of Aida. She defines Aida’s spirit in a succinct and insightful way: “To live in such an overstimulating environment, where you add new things to it all the time, you have to have a place in your mind where there’s a quiet calmness. I think Aida always had that. She was naturally serene. And she had a very strong sense of her own style and who she was – and I think that Braam enhanced that. It was a combined thing because Aida and Braam had that perfect sense of style, with clothes, with food, with the way they lived, the cars they drove, The way they did everything came naturally. They did everything in a considered way, and with care long before everyone was into good food and natural things. They were completely different to anyone else that I’ve ever met.”

Aida was once asked what her ideal living situation would be. Her answer was simple: “I want Braam to build me a room on top of the garage, furnished only with my piano, and a window with a view of the sea.”

Why do we live where we do?

Because we do not seek safe havens

And because of friends Braam and Aida.

Aida died in 2012.

I met Phillicus Olivier in 1958, in Standard Four at Jan van Riebeeck Primary, and we became friends. He was my friend for life, so to speak –loyal, caring and loving.

A couple of weeks ago, in our final conversation, this kind and gentle man mentioned to Tasha and me that the only life worth living was one of creative endeavour. Whether playing jazz on his violin or cooking a fourcourse meal, he lived by his credo - his was a life of spirituality peppered with sustained hedonism. A life worth living.

T ASHA@50

My speech at my partner Tasha’s 50th birthday party on 4 February 2024: Yesterday I asked the AI app ChatGPT to write a speech for my girlfriend upon her 50th birthday, adding that she was vivacious, clever, funny, stylish, generous and joyful. In a flash, the app wrote back: “Ladies and gentlemen, esteemed guests, It is an honour … “

It went on and on in this formal language, one cliché after the other, so I decided to skip ChatGPT, because all I really wanted to say is:

“Tasha brings a unique energy that feels like someone has just turned up the music. She sparks joy.

She teaches me the difference between touching and feeling, between hearing and listening, between looking and seeing ...

“For now we see through a glass, darkly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; but then shall I know, even as also I am known. And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love.” (1 Corinthians 13:12)

Let’s drink to her health!