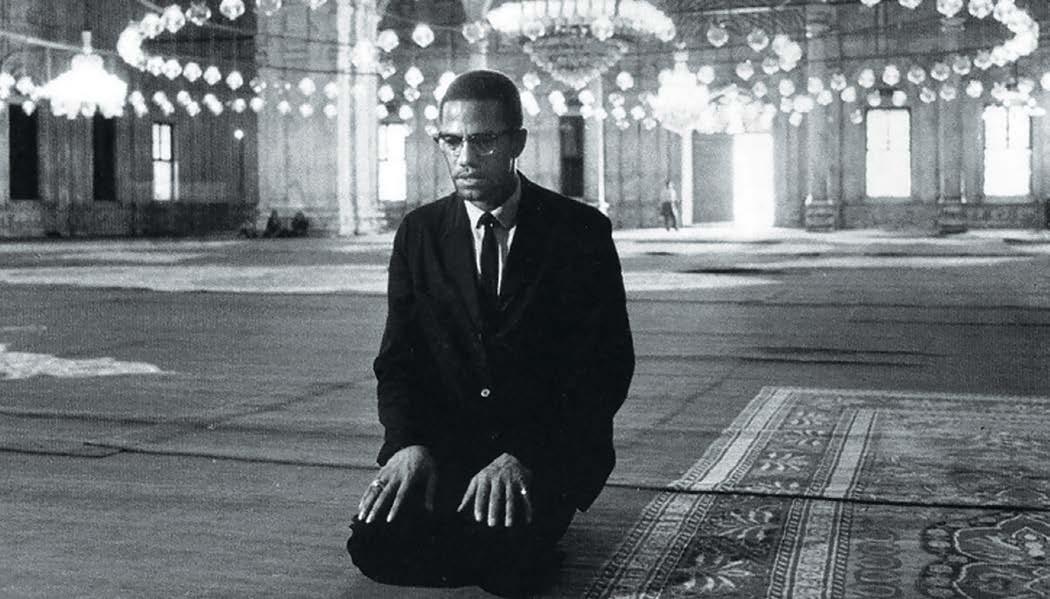

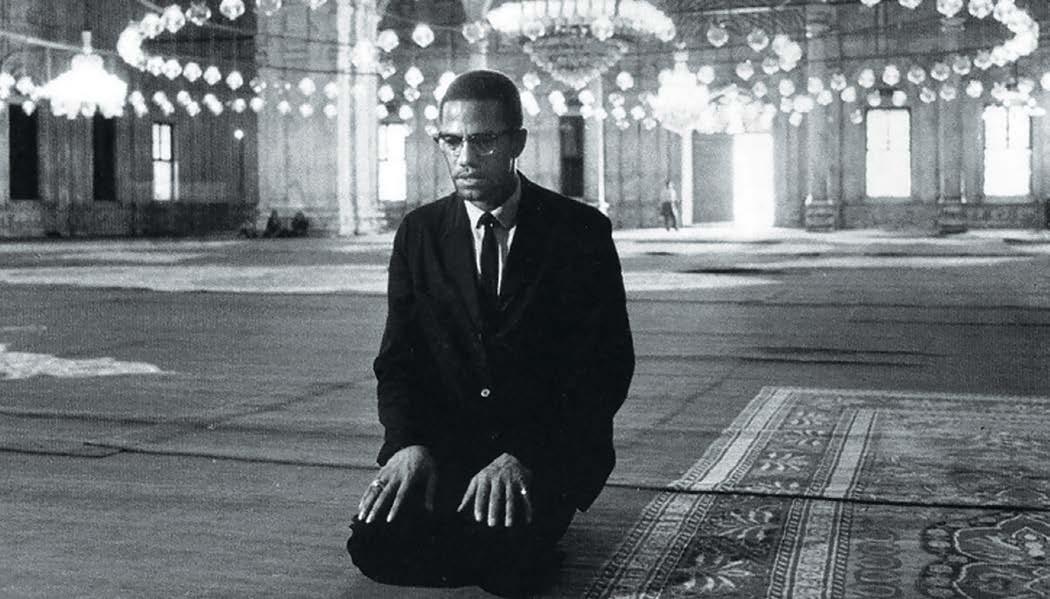

May 19, 2025 would have been Civil Rights leader Malcolm X’s 100th birthday. As we witness Israel’s genocide in Gaza today, we must remember that 60 years ago, Malcolm X and other prominent activists were already condemning Zionism and calling for the right of the Palestinian people to return to their land. In a 1964 essay, Malcolm X wrote, “Zionist logic is the same logic that brought Hitler and the Nazis into power... It is the same logic that says that because my grandfather came from Ireland, I have the right to go back to Ireland and take over the whole country” (The Egyptian Gazette, Sept. 17, 1964).

During a speech in Detroit that same year, he said, “We don’t need a divided Palestine; we need a whole Palestine.”

Dr. James Jones, a veteran of the Civil Rights Movements, takes Islamic Horizons readers through a series of unfortunate racist decisions made by the United States Supreme Court. This painful past is being extended and exacerbated today under false pretenses from the current presidential administration such as liberty, independence, security, and national pride.

In April, ISNA held its 26th Education Forum focusing on “Bridging Tradition & Innovation: Cultivating Hope and Joy in Our Schools.”

Rasheed Rabbi, who has been a constant source of enlightenment on the ISNA convention scene states that the ISNA annual convention is a call to action to recognize and renew America’s righteous spirit — not rhetorically, but strategically. More than a conference that merely offers novel ideas, it’s a gathering of conscience, a platform of resistance, and a place for communities to come together to uphold the true American spirit.

ISNA invites everyone to speak the truth, to demand justice, and to embody freedom. The convention will not merely discuss these principles — it will model them. Through critical

dialogue, faith-rooted actions, and collective resolve, the ISNA 2025 annual convention aims to empower individuals, families, communities, and leaders to restore our legacy.

To be righteous is not to be passive. It is to stand firmly, act boldly, and love deeply — this land, its people, and their collective potential.

Also, in this issue, Professor Nadia B. Ahmad asserts that now is the time for Muslims to set the agenda. The Muslim American community, she reminds us, is at a generational turning point, one that calls not for cautious optimism or slow, negotiated progress, but for decisive and unapologetic agenda-setting. For too long, she states, we have been trained to believe that our victories lie in representation, access, and reconciliation. But history has shown time and again that systems do not change through symbolic presence alone.

Lawyer Faisal Kutty discusses Muslims seeking beyond a seat at the table, pointing out when representation becomes complicity.

Lauren Banko offers a striking review of Louis Theroux’s BBC documentary The Settlers (2025) which chronicles atrocities committed by Israeli settlers against Palestinian civilians, their homes, and their lands. For the viewer, these atrocities are haunting because they are so mundane. Their mundanity stems from the fact that they have been going on since Israel began its military occupation of the Palestinian West Bank and Gaza Strip in June of 1967.

Still, this comes at a moment in which the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is using “full force” — not only unhindered but also constantly militarily replenished by the U.S., U.K., and other European countries — to continue the 77-yearlong genocide against Palestinians, now in play in Gaza since October 2023. As such, Gaza remains in sight, literally and figuratively, throughout the hour-long documentary. ih

PUBLISHER

The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA)

PRESIDENT

Syed Imtiaz Ahmad

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Basharat Saleem

EDITOR

Omer Bin Abdullah

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Bareerah Zafar

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

Iqbal Unus, Chair: M. Ahmadullah Siddiqi, Saba Ali, Rasheed Rabbi, Wafa Unus

ISLAMIC HORIZONS

is a bimonthly publication of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) P.O. Box 38 Plainfield, IN 46168-0038

Copyright © 2025 All rights reserved

Reproduction, in whole or in part, of this material in mechanical or electronic form without written permission is strictly prohibited. Islamic Horizons magazine is available electronically on ProQuest’s Ethnic NewsWatch, Questia.com LexisNexis, and EBSCO Discovery Service, and is indexed by Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature.

Please see your librarian for access. The name “Islamic Horizons” is protected through trademark registration ISSN 8756-2367

POSTMASTER

Send address changes to Islamic Horizons, P.O. Box 38 Plainfield, IN 46168-0038

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Annual, domestic – $24 Canada – US$30 Overseas airmail – US$60

TO SUBSCRIBE

Contact Islamic Horizons at https://isna.net/SubscribeToIH.html On-line: https://islamichorizons.net For inquiries: membership@isna.net

ADVERTISING

For rates contact Islamic Horizons at (703) 742-8108, E-mail horizons@isna.net, www.isna.net

CORRESPONDENCE

Send all correspondence and/or Letters to the Editor at: Islamic Horizons P.O. Box 38 Plainfield, IN 46168-0038

Email: horizons@isna.net

BY RASHEED RABBI

False ceasefires and peace treaties masked ulterior agendas. Gender discourse was distorted to sabotage the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) efforts. Education and research are defunded to stifle a nation’s future. Aggressive crackdowns on immigration stoked the ageold fear of racism. And the list goes on.

These are not isolated acts but coordinated tactics of a sweeping agenda unfolding through a barrage of executive orders under the second Trump administration. As of May 14, 2025, 152 executive orders, 39 memoranda, and 54 proclamations have irrevocably reshaped policy, sharpened hidden agendas, and sent shockwaves nationwide. While political analysts frame these actions within the familiar slogans like “Make America Great Again,” “America First,” and “Peace Through Strength,” the deeper truth has been laid bare: these slogans are mere façades. These orders are not reforms but instruments of erosion. Not solutions but strikes against the very spirit of America. Their intent is not to fix but to fracture, not to strengthen but to suppress. To call them merely deceptive would be an understatement. These are lies inked with deceptive intent long before the signatures on these contentious documents dried.

The 2024 presidential election’s defining issue was the Gaza ceasefire. Despite standing atop a mountain of corpses, bathing in Palestinian blood, and inhaling their dying breaths, the Biden administration remained

unmoved. Its refusal to act exposed a partisan allegiance to Israel which was steeped in political expediency.

That inertia became the perfect electoral bait that President Donald Trump seized. He offered what Joe Biden couldn’t: the promise of peace. Trump promised to deliver a ceasefire, which won him the Michigan Muslim vote, a key factor in his 2024 electoral victory (Sarah McCammon, “Arab and Muslim voters helped deliver Michigan to Trump. They’re not all happy so far,” March 4, 2025. NPR). Yet, before even taking office, he reneged. What followed wasn’t peace, but rather a more calculated bloodletting in Gaza and across Palestine.

His so-called three-phase ceasefire for Gaza hasn’t paused the bloodshed; instead, it has paved the way for a genocidal ethnic cleansing executed with unwavering U.S. backing (Harb, Ali. “What Does Trump’s Ethnic Cleansing Proposal Mean for Ceasefire Deal?” Al Jazeera. Feb 8, 2025). Even in his May trip to Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and UAE, Trump labeled Gaza a “Freedom Zone,” reinforcing “his proposal to displace Palestinians from the territory just as Israel plans.”

The betrayal extends beyond Gaza. It reflects a broader foreign policy that deepens global divisions. Consider Ukraine. On Feb. 28, Republican leaders hailed President Volodymyr Zelensky as a heroic defender of democracy in the morning, but after an afternoon closed-door meeting with Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance, they rebranded him as an ungrateful warmonger (Peter Baker, et al. “Trump Administration

Updates: Trump and Vance Berate Zelensky, Exposing Break between Wartime Allies.” The New York Times. Feb. 28, 2025).

This isn’t foreign policy; it’s foreign improv. Allies are cherished until they’re inconvenient. Enemies are condemned until they’re useful. Commitments are made with solemnity only to be broken at the speed of a tweet. Can nations truly still rely on U.S. leadership when it moves not by principle, but by personal convenience?

The war at home came swift. Within hours of taking office on Jan. 20, Trump eradicated every DEI program across federal agencies and institutions. This singular act dismantled policies that provided marginalized groups equal access to opportunities at the federal level. Without DEI, corporate hiring regresses, schools lose equitable funding, and workplaces abandon fair treatment for all. “His baseless attacks on DEI are attacks on the promise of America — the promise that everyone should be able to build the life of their dreams without barriers standing in their way,” Andrea Abrams, Executive director of the Defending American Values Coalition, told USA Today (Jessica Guynn, “DEI Explained: What Is DEI and Why Is It So Divisive? What You Need to Know.” USA Today. March 5, 2025).

The education sector is also under attack. Federal funding cuts target universities where protests against Israel’s genocide in Gaza have taken place. The Trump administration cut $2.2 billion in funding from Harvard, $400 million from Columbia, $210 million from Princeton, and millions more from dozens of other institutions of higher learning in the United States (Roy, Yash. “Trump Administration Suspends Dozens of Research Grants to Princeton.” CNN. April 1, 2025).

This isn’t about antisemitism, as the administration claims; it’s about silencing academic dissent. Suspending federal funding revokes the intellectual freedom of American universities. Ideological conformity is dictating funding. Universities now face an impossible choice: comply with political mandates or risk financial collapse.

The very principles that once made American universities the envy of the world — free speech and academic independence — are now under siege (Sharon Lurye and Jocelyn Gecker. “Colleges’ Federal Funding in Doubt under Trump Thanks to Cuts, Investigations.” AP News, March 28, 2025). This slow erosion of academic freedom is part of a broader effort

to consolidate control over public discourse, an “unspoken promise of Trump’s return” (M. Gessen. “Opinion: This Is the Dark, Unspoken Promise of Trump’s Return.” The Salt Lake Tribune. November 17, 2024).

The administration’s immigration stance also exceeds prior political posturing, advancing the false narrative that America is under siege

unconstitutional, violating the separation of powers that gives Congress, not the president, authority over federal spending.

In March alone, layoffs surged by 205%, with over 275,000 jobs eliminated, one of the highest monthly spikes in U.S. history. A major driver? Mass firings led by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), an entity with no Congressional mandate or legal basis.

The ISNA annual convention is a call to action to recognize and renew Muslim Americans’ righteous spirit not rhetorically, but strategically. More than a conference that merely offers ideas, it’s a gathering of conscience, a platform of resistance, a place for communities to come together to uphold the true American spirit.

by illegal immigrants. Within his first 100 days in office, Trump invoked archaic immigration laws, questioned judges’ power to rule against his decisions, and attempted to end several legal immigration pathways (Maria Briceño & Maria Ramirez Uribe. “How Falsehoods Drove Trump’s Immigration Crackdown in His First 100 Days.” Al Jazeera, April 29, 2025).

Drastic restrictions and abrupt policy shifts have generated uncertainty for millions, from asylum seekers to scholars to businesses reliant on immigrant labor. While national security and economic concerns are valid considerations in shaping immigration policy, unilateral and ideological executive actions fail to address the complexities of the issue in a sustainable or legally-sound manner.

And even if you dodge these issues, the reeling economy won’t spare you. Stocks are tumbling, shedding over $5 trillion in market value in just three weeks in March 2025 (Jesse Pound, “U.S. stock market loses $5 trillion in value in three weeks,” CNBC, March 14, 2025). Markets are in a tailspin. Business leaders are panicking. Consumers are frightened and confused, and economists are desperately trying to make sense of a capricious tariff policy that punishes Americans more than foreign business interests. Within only 100 days in the Oval Office, Trump has driven an economy that the world envied to the brink of imminent recession (CNN).

Nor do the unilateral federal job cuts demonstrate reform; rather, they are purges. Democrats, labor unions, and watchdog groups condemn the moves as

Perhaps no one embodied the epitome of this administration’s collision of wealth, racist ideology, and unregulated authority more than Elon Musk. Though he left his position at the White House in May, Musk remained the largest individual donor in the 2024 presidential election, funneling over $290 million to Republican causes." Before his departure, he operated as a "special government employee," shaping federal policy while profiting directly from it.

His companies, SpaceX, Tesla, and Starlink, collectively received nearly $38 billion in federal contracts, subsidies, and tax breaks (Desmond Butler. “Elon Musk’s Business Empire Is Built on $38 Billion in Government Funding.” The Washington Post, Feb. 26, 2025). 53% of registered voters disapprove of him, and he hadn’t received an official appointment from the Senate. His position was not for public service. It was profiteering disguised as patriotism. When unelected billionaires dictate public policy, democracy is not merely weakened but is reconfigured into corporate oligarchy. And we may be closer to that reality than we think.

These glimpses of widespread depravity at the federal level are meant neither to discourage nor to fuel partisan attacks. Every administration has strengths and flaws, but the above concerns are recent and deeply interconnected. They are escalating too fast, even for an urgent call for leaders and citizens to act on behalf of the greater good of a nation

pledged to freedom and unity. That’s exactly what ISNA’s annual convention upholds.

What we are witnessing is not just policy shifts or misguided reforms; it is an orchestrated act of betrayal cloaked in patriotism designed to seize the American spirit and its founding promises of pluralism.

Despite a Republican House majority that could advance laws through standard procedures, governance now relies on executive actions at an unprecedented scale. This trend circumvents the checks and balances designed to ensure democracy, disregards institutional norms, and reflects a broad mistrust of the U.S. political system’s foundations.

Likewise, the speed and scale of these changes exemplify a restructuring of American institutions to fit a singular ideological vision. It shows power is no longer shared but wielded. It portrays an emerging political landscape defined by volatility, polarization, and departure from established norms.

The truth is unsettling, but confronting it is essential. Preserving democratic principles, institutional integrity, and public trust — the core of the American political system — demands scrutiny and accountability. The future of America depends not just on who holds power, but on how that power is exercised.

The ISNA annual convention is a call to action to recognize and renew Muslim Americans’ righteous spirit not rhetorically, but strategically. More than a conference that merely offers ideas, it’s a gathering of conscience, a platform of resistance, a place for communities to come together to uphold the true American spirit.

ISNA invites all to speak the truth to demand justice, to embody freedom. The convention will not merely discuss these principles; it will model them. Through critical dialogue, faith-rooted actions, and collective resolve, the ISNA 2025 annual convention aims to empower individuals, families, communities, and leaders to restore our legacy.

To be righteous is not to be passive. It is to stand firmly, act boldly, and love deeply this land, its people, and its promise.

We stand united to renew America’s spirit by defending the truth.

We protect its future by fighting for justice. We keep it free by following prophetic ideals in this challenging time. ih

Rasheed Rabbi, community, prison, and hospital chaplain at NOVA, Doctor of Ministry from Boston University, and MA in Religious Studies from Hartford International University. He is the founder of e-Dawah and Secretary of the Association of Muslim Scientists, Engineers & Technology Professionals.

BY CRYSTAL HABIB

The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) held its 26th Education Forum on April 18 to 20, 2025 in Chicago where it welcomed over 530 educators, administrators, and leaders from the Islamic education community. The event’s theme, “Bridging Tradition & Innovation: Cultivating Hope and Joy in Our Schools,” underscored a collective commitment to nurturing an educational environment that respects Islamic tradition while embracing modern pedagogical advancements.

This year’s forum included more than 40 distinguished speakers and offered over 20 interactive sessions, making it a comprehensive learning experience for attendees. The sessions featured a diverse array of topics critical to contemporary Islamic education, including Arabic, Quranic and Islamic Studies, Curriculum and Instruction, Mental Health and Wellness, and Administration and Leadership. The event addressed the challenges educators face while providing solutions through collaborative discussion of shared experiences.

A lively bazaar with 20 vendors offered a variety of goods showcasing various

educational products, Islamic art, prayer mats, perfumes, abayas, and essential services that catered to the needs of attendees. The vibrant energy in the hallways highlighted the spirit of collaboration and community that the ISNA Education Forum fosters, encouraging interaction and dialogue among participants.

This year’s forum was bolstered by partnerships with the Council of Islamic Schools Based in North America (CISNA) and Weekend Islamic Schools Educational Resources (WISER). These collaborations played a vital role in ensuring that the content presented was relevant and tailored to meet the evolving needs of Islamic educators. Workshops and discussions were informed by current trends and best practices, allowing attendees to walk away with actionable insights applicable to their respective institutions.

The forum served as a platform to recognize outstanding contributions to the field of Islamic education. The prestigious Lifetime Service Award was presented to past ISNA president Safaa Zarzour, Assistant Director

of Little Horizons Academy, honoring his unwavering dedication and extensive impact on Islamic education and community leadership. With roles including former President of ISNA and superintendent of Universal Schools, Zarzour’s commitment exemplifies the essence of service to future generations.

Among the many impactful sessions were:

“Revolutionizing Arabic Classrooms with Technology” by ESL and Arabic educator Fatima Raafat, PhD, which focused on integrating innovative technologies into Arabic language teaching, elevating the student learning experience.

“ Teaching Tadabbur to Cultivate Spiritual Resilience” led by Ismail ibn Ali, the Head of School and Program Manager at the Center for Innovative Religious Education at Al Faith Academy. This session emphasized the value of spiritual reflection through Qur’ānic contemplation which leads to student transformation.

“Leading Meaningful Practices to Strengthen School Environments” by Principal Haleema Syed from the Islamic Center of Naperville Noor Academy offered practical strategies for fostering positive relationships between staff, students, and parents to create thriving school cultures.

“Promoting Social Justice in Our Schools” was led by Amaarah DeCuir from the American University School of Education and author and educator Rukayat Yakub from Ribaat Academic Institute. It discussed the role of anti-Blackness in justifying slavery and subsequent acts of exclusion and aggression in the United States. The presenters stated that Islam was purposeful in elevating every racial and ethnic group and as such, it is the duty of every Muslim to do something about it in an effort to take care of all members of humanity.

“A Preventative Approach to Preserving Muslim Mental Health in Western Culture” was conducted by Dr. Sarfraz Khan, adjunct professor of psychiatry at the Indiana

University School of Education. “Ultimately the goal is to prevent mental illness the same way we strive to prevent other types of illnesses,” Khan said. He focused on the responsibility that parents have in raising their children and that there is a limited window for raising them well. Dr. Khan emphasized Frederick Douglass’ famous quote, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

“ Pursuing Excellence in Team Leadership: Effective Behaviors for School Team” was led by CISNA president William White and featured an interactive workshop that explored research-based best practices for team building using the Five Behaviors of a Cohesive Team framework created by business management expert Patrick Lencioni. Participants reflected on their experiences working within Muslim organizations, learned simple and effective framework for team behaviors, and identified key issues.

“Enhancing Student Engagement, Achievement, and Joy Through STEM Challenges,” led by University of Houston Clear Lake graduate assistant Maisa Meziou, offered a dynamic STEM activity that engaged students, integrated STEM disciplines, and aligned with learning standards. The activity featured was The Bucket Challenge, a cost-effective, accessible, and simple activity that showcased how STEM challenges can elevate student engagement, enhance achievement, and infuse joy into learning.

“Evolution, Free Will, and the Human Experience: Navigating Life’s Big Questions” featured a panel that included educator, author, and youth activist Habeeb Quadri; educator and consultant for the High Quality Educational Consulting Aisha Basith; Director of Initiative on Islam and Medicine Aasim I. Padela; educator Bilal Ali Ansari; and physician and pharmaceutical executive Ahsan M. Arozullah. This session, aimed at high school and college education, explored integrating the study of biosciences into Islamic curriculum, tackling critical topics that can confuse Muslim students. It emphasized the use of revelation as a genuine source of knowledge when addressing fundamental questions about the human being. By applying a holistic epistemological framework, students have increased their knowledge, preparedness, and faith when addressing topics of friction between science and Islam.

“Empowering Islamic Education with AI: Practical Tools for Teachers” was led by AI

experts and co-founders of Nur Al Huda AI, Ibrahim Murtuza and Mohammed Abdul Jabbar and explored how Islamic schools can harness the potential of AI to enhance education. This session provided educators with practical AI tools to streamline lesson planning, personalize instruction, and reinforce an Islamic worldview in the classroom. Participants explored real-world applications, engaged in interactive demonstrations, and left with actionable strategies to implement AI effectively.

During the Saturday Luncheon, ISNA’s Mental Health Initiative was introduced by its Chair, Salman Ahmad who is a Clinical Psychology Ph.D. candidate at the University of Miami where he founded the Muslim American Project. This initiative aims to promote mental wellness and resilience in Muslim communities by leveraging Islamic teachings coupled with contemporary mental health principles. The full introduction to this service can be found through the mental health portal on the ISNA Website.

Keynote speaker Huda Alkaff from the ISNA Green Initiative Team discussed environmental justice and the significance of Chicago in the history of the movement. “As Muslims, we are tasked to care for our planet, a principle echoed throughout the Quran,” she said. Her insights brought attention to the significance of environmental stewardship for future generations.

Pre-conferences allowed for day-long deep dives into several topics. New this year was a tour of two campuses of MCC (Muslim Community Center) Academy which allowed school leaders to learn about the development of a local Islamic school, gain practical insights, and become informed about best practices through the observation of a variety of school activities and presentations led by MCC staff.

The Arabic and Quran workshop provided participants an opportunity to learn how storytelling is a valuable pedagogical strategy that sparks curiosity, enhances communication skills, and demonstrates and promotes Islamic morals and values. Educators who took part in that workshop concluded their session by creating lesson plans that incorporated storytelling within

their contexts. The Health and Wellness workshop focused on equipping educators with tools to address mental health challenges among Muslim youth.

The Forum was a resounding success marked by enthusiastic participation, enriching discussions, and significant networking opportunities. Each session, workshop, and conversation contributed to a renewed commitment to excellence in Islamic education. Attendees left inspired to implement new strategies and insights that will positively impact their students and communities. For more detailed information about the sessions and presenters, please explore the ISNA website under the resources section labeled “Education Forum Papers.”

ISNA extends a heartfelt thank you to the program committee for their dedication, which includes Co-Chairs Abir Catovic and Azra Naqvi, and Ziad Abdalla, Majida Abdul-Kareem, Salah Ayari, Magda Saleh Elkdai, Kathy Jamil, Farea Khan, and Nancy Nassr, alongside ISNA staff members, Programs Manager Muktar Ahmad, Project Manager Tabasum Ahmad, Communication and Social Media Coordinator Crystal Habib, and Program Intern Malaika Khan.

Special thanks to our sponsors: American Islamic College, Fawakih Institute, and Diwan, Islamic Services Foundation, School Pro, and IQRA. We appreciate the attendees, the hotel and banquet hall staff, volunteers, staff members and all those who helped make this event successful. May Allah reward your work! ih

On May 5, Chicago-based grassroots organization Ojala Foundation officially purchased property in Berwyn, Ill. that will serve as the first Latino-led mosque in the Midwest. This former church is housed in a 1948-built Gothic building with easy access to public transportation and 14,000 square feet ready to be repurposed into a prayer area, large banquet/community hall, classrooms, and a library.

Two decades ago, Latino Muslims in Cook County had little to no resources that helped them connect Islam and their heritage. With the help of the Ojala Foundation, they have been able to bridge that gap. This new mosque will go beyond just being a building for the Latino community. It will be a sanctuary for prayer and culture, for healing and heritage; a space created by and for Latino Muslims with a vision that will carry forward for generations.

The Ojala Foundation purchased the property for $1.3 million. They still need $700,000 to complete renovations. Those interested in donating to fund this new mosque can do so at ojalafoundation.org/donation.

On May 7, the United Nations announced the appointment of the High Representative of the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations (UNAOC), Miguel Ángel Moratinos, as the UN Special Envoy to Combat Islamophobia. This historic appointment marks a major milestone in the United Nations’ efforts to combat the alarming rise in hatred, intolerance, and discrimination against Muslims worldwide, a Foreign Office statement said.

Moratinos has served as the UN Under-Secretary-General, holding the post of UNAOC since January 2019.

In February 2020, he was designated by the UN Secretary General as the UN Focal Point to monitor antisemitism and enhance a system-wide response.

As a believer in the value of multilateralism, Moratinos helped in the creation and launch of the UN Alliance of Civilizations in 2005. He also supported the Group of Friends for UN Reform.

In March 2019, Moratinos was awarded with the “League of Arab States” Award by the League of Arab States for his role in strengthening Arab-Spanish relations. Moratinos graduated with a degree in Law and Political Sciences at the University Complutense in Madrid and a degree in Diplomatic Studies at the Spanish Diplomatic School.

national, and regional meetings and conferences. Azarian served for four years as a Discipline Peer Reviewer for the Fulbright Scholar Program from 2015 to 2018 and published 78 reviews in the AMS’s Mathematical Reviews and the European Mathematical Society’s zbMATH Open. These honors recognize his outstanding contributions to research, problem creation, and his unparalleled service to the mathematics community.

Dr. Umair A. Shah, the former Secretary of Health of Washington State, received the Chancellor Robert D. Sparks, M.D., Award in Public Health and Preventive Medicine from the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) on May 9.

During this year’s convocation address, Shah celebrated UNMC’s graduates and shared five reflections from his own journey. Shah said while things may appear differently, people are largely the same alluding to differing political ideologies. He also placed emphasis on being ready to pivot as things will change. He said that behind every data point is a story, and behind every story is a life. He urged the graduates to listen to that story and to not be afraid of taking on challenges. He concluded with a reminder to always do good.

The Chancellor Robert D. Sparks, M.D., Award was established in 1997 in honor of Dr. Sparks, the first president and CEO of Physicians for a Healthy California (PHC). It honors individuals or organizations that have demonstrated outstanding concern for the health of communities.

University of Evansville Prof. Mohammad K. Azarian made history as the first Muslim and the first Iranian American mathematician to have two prestigious mathematics awards named in his honor by the American Mathematical Society (AMS) and the Mathematical Association of America (MAA).

His extensive academic work includes the publication of 47 papers, 87 problems, and over 60 presentations at international,

The Mohammad K. Azarian Prize for Mathematical Reviewers, established by AMS, honors mathematicians who have demonstrated exceptional contributions to the peer review field. The Mohammad K. Azarian Scholar Award, established by MAA, celebrates excellence in mathematical problem creation. This award recognizes individuals whose original, thought-provoking problems challenge and inspire the mathematical community.

The inaugural award will be presented in August at MathFest 2025 in Sacramento.

M. Affan Badar, Ph.D, Vice President of ISNA USA, was recognized by the Indiana State University (ISU) with the 2025 Faculty Distinguished Service Award on April 17. The award is given based on continued dedication and leadership at the university, professional, and community levels. In 2023, he received the ISU Theodore Dreiser Distinguished Research/Creativity Award.

Badar is a professor of Engineering and director of the Ph.D in Technology Management program at Bailey College of Engineering and Technology at ISU. He was the Professor and Chair at the Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management Department at University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates from 2016 to 2018. At ISU, he was the interim Associate Dean of Curriculum, Accreditation, and Outreach from 2014 to 2015. From 2010 to 2014, he served as the chair of the Applied Engineering and Technology Management department. He has also served the University Faculty Senate, Faculty Senate Executive Committee, and College Faculty Council in different capacities including leadership roles. For engineering and technology accreditation in the United States, he is an ABET/ETAC commissioner and started as a program evaluator in 2010 for ETAC and EAC.

President Donald Trump has chosen California Republican state lawmaker Bill Essayli to be the next U.S. attorney in Los Angeles. Essayli will oversee federal law enforcement in the Central District of California, the nation’s most populous federal court jurisdiction encompassing nearly 20 million residents. He served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the office earlier in his career.

The son of Lebanese immigrants, Essayli became the first Muslim member of the California chamber when he was elected in 2022. Since then, he has represented a conservative pocket of inland Southern California in the statehouse.

Essayli will replace acting U.S. Attorney Joseph McNally who filled the post earlier this year after Biden-appointed Martin Estrada left for private practice just before Trump’s inauguration.

Cornell University’s Muslim chaplain, Numan Dugmeoglu, and the Diwan Center for Muslim Life received the 29th annual James A. Perkins Prize for Interracial and Intercultural Peace and Harmony during a ceremony on April 21 at Willard Straight Hall, reported Laura Gallup, a communications lead for Student and Campus Life for the Cornel Chronicle

Each year, the $5,000 Perkins Prize is awarded to a Cornell program, organization, or event making the most significant contribution to furthering the ideal of the university’s community while respecting values of diversity.

Dugmeoglu, who joined in November 2023, has brought stability and increased visibility to Cornell’s Muslim community of at least 1,000 students, faculty, and staff, said Marla Love, the Robert W. and Elizabeth C. Staley Dean of Students. Students from the Diwan Center attended the ceremony and Dugmeoglu accepted the award on behalf of the group.

Winchester, Va.-based Shenandoah University bestowed the Doctoris Honoris Causa degree on Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, formally presented by University President Dr. Tracy Fitzsimmons at a ceremony held at the International Islamic University, Gombak Campus, in Kuala Lumpur on April 11. The award was in recognition of Anwar Ibrahim’s contribution to leadership and community development. The ceremony was attended by Selangor Chief Minister Amirduddin Shaari and about 3,000 staff and students, reported Bernama TV. For more details visit: https://www.su.edu/ blog/2025/04/28/shenandoah-university-awards-honorary-doctorate-to-malaysian-prime-minister/ ih

“Building bridges across identities is not always easy,” Dugmeoglu said. “But in those spaces, I have seen something beautiful: students who lean into discomfort with courage, who seek not only to understand others but to transform themselves.”

Dugmeoglu continued, “Unity is not accomplished through uniformity in the absence of difference, but rather through the wholehearted embracing of diversity. In fact, our differences are exactly what we need to bring to life the mosaic-like tapestry of our shared community here on campus.”

Early in his career, Omar worked in the telecom and technology solutions industries in leadership roles for over a decade, including at AT&T and Verizon.

Asif Mahmod Malik (D) was re-elected as a Trustee for Maine Township, a suburb of Chicago, on April 1. Malik, who holds degrees in science and agricultural management, currently serves as the traffic manager for the Cook County Circuit Court.

Amir Omar was elected mayor of Richardson, Texas on May 3. The son of a Palestinian father and an Iranian mother, Omar (B.S. Texas A&M ’96; MBA University of Texas at Dallas ‘13), who previously served on the city council, defeated the incumbent Bob Dubey with 55% of the votes.

Omar is the Council liaison to the Environmental Advisory Commission (EAC); the Council liaison to the Retail Committee; and is on the Methodist Richardson Medical Center Foundation board.

As the Council liaison to the EAC in 2010, Omar championed the “Tree The Town” initiative, a program that aimed to plant of 50,000 trees in Richardson over the next 10 years.

In May 2012, Omar was selected by the nonprofit One Man Dallas as “the man aged 24-44 who represents the best of DFW community engagement.” That year, he was also named Regional Community Leader of the Year by the Greater Dallas Asian American Chamber of Commerce.

The Chicago-based Niles Township High School District 219 Board of Education inducted three new members during their meeting on May 6. Board elections were held on April 1 as part of the consolidated election cycle. Nour Akhras, MD, Kandice Cooley, and Lindley Wisnewski were sworn in and seated during the Organization of the Board. A Morton Grove resident of 10 years and an immigrant who left Syria at the age of four, Akhras brings decades of experience in pediatric health care and global humanitarian work to her new role. As a board member for medical Non-Governmental Organizations such as MedGlobal and the Syrian American

Medical Society, she has traveled the world providing care to displaced children. She is the mother of four children, including two future Niles North High School students.

Her motivation to serve on the D219 Board stems from her understanding of how a child’s social and emotional environment impacts their overall health.

In addition to her work as a physician and advocate, she is the author of Just One: A Journey of Perseverance and Conviction, a book that humanizes the refugee experience.

families have become friends. We belong to a kind of a club, if you will, that neither family wants to be a part of, but we are very grateful that we have each other,” he said. “Rachel and Ayşenur had a lot in common… They both still need to have an investigation into their killing.”

Washington State House adopted resolution HR 4661 on April 23, recognizing Ayşenur Ezgi Eygi’s life and activism. Her family attended the reading of the resolution and spoke at a press conference afterward. Eygi graduated from the University of Washington in June 2024 with a major in Psychology and a minor in Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures.

On Sept. 6, 2024, an Israeli sniper killed the 26-year-old activist as she observed a protest in the West Bank against Israel’s theft of Palestinian land. Since then, her family and other advocates have called for justice and accountability for her killing. They also called for support for Washington State Senate Joint Memorial 8012 which calls for an independent U.S.-led investigation into Eygi’s killing to ensure justice and accountability.

“Ayşenur’s death was no accident. It was a targeted, brutal act — a cold and unjust killing of a young woman who devoted her life to peace,” said Ozden Eygi Bennett, Ayşenur’s sister. “We will not be silent. We will not stop demanding justice. We will not stop fighting for the truth. And we will not rest until this government does what it is obligated to do: investigate the death of an American citizen.”

In his remarks, Ayşenur’s husband Hamid Ali recalled the death of another Washingtonian activist, Rachel Corrie, who was crushed by an Israeli bulldozer in 2003 while peacefully protesting in Rafah. “If Rachel’s killing had been adequately investigated, perhaps Ayşenur would still be with us today,” Ali said. “I urge all of you to support this call and in doing so help prevent the possibility of another Rachel or another Ayşenur in our future.”

Rachel Corrie’s father, Craig Corrie, was also in attendance in support of the bill. “Our

The city of Santa Clara commemorated the month of April as American Muslim Appreciation and Awareness Month with a special presentation at its city council meeting on April 8. The proclamation recognized the “rich history and significant contributions that Muslim Americans have had on [the] city and community.” The presentation took place during the first few minutes of the meeting.

Additionally, the Bay Area cities of Berkeley, Dublin, and Milpitas honored local Muslim community members by officially proclaiming April as American Muslim Appreciation and Awareness Month at their respective city council meetings April 15. The presentations were done at the beginning of each meeting.

Following resolutions passed by both chambers of the Florida Legislature, May 2025 was recognized as Florida Muslim-American Heritage Month.

To commemorate the occasion, CAIR-Florida’s Imam Abdullah Jaber delivered a Jumu‘ah Khutbah at Masjid Al-Ansar, Florida’s first Islamic center, located in Miami’s inner city. After the Friday prayer, remarks were offered by Masjid Al-Ansar’s resident imam and founder, Imam Nasir Ahmad, a long-standing community leader.

In April, the Florida House of Representatives adopted HR 8069, a resolution introduced by Rep. Anna Eskamani and co-sponsored by Reps. Rita Harris and Angie Nixon. Shortly thereafter, the Florida Senate adopted SR 1384, sponsored by Sen. Carlos Guillermo Smith. Both resolutions recognize May as Muslim-American Heritage Month and celebrate the contributions and culture of Muslim Americans in Florida.

On Feb. 28, 2025, Muslims celebrated the opening of one of the largest mosques

built in Woodland, inland California. The Woodland Mosque serves this city of just over 60,000 people.

Woodland Mosque Board President Muhammad Ahad Parvez presented plaques from the community to Mohammad Usman Sadiq for his engineering and project management contribution.

Reportedly, Muslims from Pakistan first settled in Woodland, Calif., in 1957, and the first South Asian Muslims settled in inland California over a hundred years ago.

This mosque, which took six years to complete, had its groundbreaking ceremony in 2019 which was partially delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a powerful gesture of solidarity, a large banner displaying the names of the supporting churches and faith communities, alongside a message of unity, was erected at the corner of the new mosque site visible to all who passed by.

University of Maryland students voted in support of University System of Maryland Foundation and University of Maryland College Park (UMCP) Foundation divesting from certain defense, military, and security companies in the Student Government Association (SGA) election in April, securing 55% of the vote.

The ballot question called on the SGA to begin lobbying the university system and the UMCP foundation to divest from companies such as Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, that may be complicit in human rights violations in places such as Palestine, Myanmar, and the Philippines (Pera Onal,

“UMD students vote in support of divestment referendum,” April 18, 2025, Diamondback).

The SGA passed an emergency bill on March 5 to hold the nonbinding campuswide referendum during the election held from April 1 to 3. The ballot question comes months after more than 650 students signed a petition urging SGA to add the question to its 2025 election ballot, The Diamondback previously reported.

This university’s Students for Justice in Palestine chapter circulated the petition, which came just after a nearly identical SGA resolution failed to advance in November.

Discussions about divestment have increased at this university since Israel’s genocide in Gaza began in October 2023.

The university, however, wrote in a statement to The Diamondback that the results of the referendum have no bearing on the operations or policies of the university or its foundations.

The Council of Muslim Organizations (USCMO) hosted its 10th Annual National Muslim Advocacy Day under the theme “Defending Rights, Shaping Policy” on April 28 and 29 in Washington, D.C. This milestone brought together over 700 Muslim leaders, activists, and constituents from across the country to directly engage with members of Congress on policies that impact Muslim communities. Together, they held over 220 meetings with Congress members and their staff, delivering one powerful message: Our rights matter. Our voices count.

This year’s National Muslim Advocacy Day focused on holding elected officials accountable and ensuring that Muslim communities have a strong voice in shaping policies that affect us all.

From now until July 31, Express Newark, supported by Rutgers University, is hosting Ritual, a series of exhibitions and events that explore the relationship between Islamic spiritual practices, rituals, and art featuring experimentations in photography, film, sound art, and textiles.

While many of the artists have some relationship with Muslim-majority contexts

worldwide, the exhibition also spanned Newark — which has long been home to one of the nation’s largest African American Muslim communities — while also branching out beyond the domestic borders. Express Newark is a center for art, design, and digital storytelling where people co-create to advocate for social change. “Our exhibitions seek to capture the dynamic histories, intergenerational experiences, vibrant lives, and integral roles that Muslim communities have in Newark, and ultimately, our nation,’’ said Salamishah Tillet, Express Newark’s Executive Director. Ritual featured work by artists, curators, students, and community members who have immersed themselves in nonsecular expressions of spirituality and Islamic traditions across the Muslim world. By bridging traditional spiritual practices and aesthetic innovations, these artistic explorations turn towards Muslim interiorities — an often underrepresented perspective in art — and inspire new discourses, worldviews, and conversations about belief and identity.

“These exhibitions allow us to have an in-depth conversation with so many artists about work that often spans different centuries and countries,” Tillet said. “They give us all a unique opportunity to refresh our perspectives about what we think we know and see, while also allowing us to more deeply reconnect to each other.”

This year, Express Newark hosted its first international artist in residence as part of Ritual. Younes Baba-Ali is a Moroccan-born multimedia artist based in Brussels who engages the public by mixing technology, objects, sound, video, and photography with political, social, and ecological issues.

Throughout his residency, he is developing a two-part installation, “Carroussa Sonore,” which translates to “sounding cart.” It engages those who live and work in Newark. Local artists and students work closely with Baba-Ali to create site-specific sound art works performed throughout Newark neighborhoods by street vendors and performance artists.

“Carroussa Sonore” departs from a religious act and becomes an intervention that

archives urban soundscapes, abstract noises, and alternative narratives throughout the African Diaspora.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit upheld the constitutionality of a Social Studies curriculum that included instructional videos about Islam (in a World Cultures and Geography class), dismissing a parent’s claim that her son’s middle school curriculum violated the Constitution by teaching about Islam, reported Colleen Murphy from NJ Advance Media.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit is a federal appellate court that reviews decisions from district courts in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

In its decision, issued May 12, the court said that the Chatham School District’s curriculum does not show any signs of promoting a specific religion.

The district said that their aim was to provide students with a comprehensive understanding of global cultures and beliefs, as required by state standards.

They also explained that the videos were meant to educate students about the basics of Islam and noted that the videos were provided to students but not shown in class or required to be watched by students. ih

BY JIMMY JONES

“O ye who believe! stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to God, even as against yourselves, or your parents, or your kin, and whether it be (against) rich or poor: for God can best protect both” (Quran 4:135).

This powerful statement from the Muslim holy book is also found in an unexpected place. According to Harvard University’s “Ask a Librarian” service, these words are displayed in Wasserstein Hall on the Harvard Law School campus as part of the “Words of Justice” art exhibit. Ironically, even though this high standard of justice can be celebrated at an elite American educational institution, it can also be easily denied.

Perhaps the most emblematic example of the denial of justice in the United States are those oft repeated words that appear in the second paragraph of the country’s Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed

by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

This compelling declaration of equality and justice sounds magnificent. However, when it was passed by the Second Continental Congress in 1776, this declaration failed miserably when it came to the rights of enslaved Black “men.” Further, even though “men” was commonly used at that time as inclusive of males and females, women had to struggle for almost a century and a half in order to obtain the right to vote in electoral politics. It has only been 105 years since women ultimately received that right with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. Thus, for Black enslaved people and women in this country, the justice declared by the Declaration of Independence was, in reality, justice denied.

But the battle for justice did not end in 1920. For instance, on June 8, 1925, in Gitlow vs. New York, the U.S. Supreme Court

established that the First Amendment’s free speech protections applied to states. Up until this point, the understanding was that the Constitution’s Bill of Rights (which includes the First Amendment) only applied to federal law. Today, this Supreme Court ruling supporting universally protected free speech is being aggressively challenged.

Currently, the full force of the U.S. government is being weaponized to prosecute free speech. Under the pretext of fighting antisemitism and terrorism, American politicians have sought to defend Israel’s killing of over 50,000 Gazans (mainly women and children) since Oct. 7, 2023 in a so-called “war” bankrolled by American taxpayers. For Muslims, Arabs, Palestinian Americans, allied organizations like Jewish Voices for Peace, and for the country’s diverse body of university students standing up for justice in Palestine, the current McCarthy-like crackdown on free speech is a textbook case of justice denied.

Gitlow vs. New York was decided when Malcolm Little (later Malcolm X) was only 21 days old living in Omaha, Neb. He was the fourth of seven children born to Earl and Louise Little. He also had 3 half siblings from his father’s previous marriage. When Little was just 12 days shy of his second birthday, the U.S. Supreme Court issued another infamous ruling. In Buck v Bell, the court held that a 21-year-old white woman could be forcibly sterilized because, as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes stated, “three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

In this case, the justices declared 8-1 that it was in the state’s best interest to sterilize such people to help improve society and the white race. This unjust decision led to the forced sterilization of over 60,000 people in more than 30 states between 1927 and 1979 as part of the then popular Eugenics movement. Subsequent researchers have called this a “war against the weak.”

The America that Malcolm Little was born into was filled with this kind of injustice. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, over 4,400 Black Americans were lynched between Reconstruction and World War II. Little’s America was a world in which you needed to be the right type of person in order to simply survive.

Little, a post World War I baby, was born into a family deeply influenced by Marcus Garvey’s pan-Africanist United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In his iconic Autobiography (1965), Little remembered his father: “the image of him that made me proudest was his crusading and militant campaigning with the words of Marcus Garvey. . . it was only me that he sometimes took with him to the Garvey UNIA meetings which he held quietly in different people’s homes.”

When Little was about 6 years old, Earl Little died in Lansing, Mich. in a mysterious streetcar “accident” which Malcolm believed was really a consequence of his outspokenness and organizing around racial issues. Again, although the Supreme Court made a justice-declared ruling supporting universal free speech, it was apparent that when it came to descendants of formerly enslaved people (like his father) and immigrants (like his mother), this was just another case of justice denied.

Both parents’ involvement in the UNIA, his father’s suspicious death, and his mother’s

devastating institutionalization when he was 12 were events that had a great impact on the man that he was to become. Thus, when Little encountered Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, he was prepared to accept these illuminating new teachings.

In the 100 years since Malcolm Little’s birth on May 19, 1925, we have seen justice declared then ultimately denied multiple times. For example, on May 17, 1954 as Malcolm X was about to turn 29, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling declaring the

In his new book, Mark Whitaker meticulously detailed how Malcom X posthumously continues to impact all Americans. On page xvii of The Afterlife of Malcolm X: An Outcast Turned Icon’s Enduring Impact on America, Whitaker wrote, “In the 21st century, the influence of Malcolm X on American politics ranged from the hold he had over the imagination of Barack Obama, the country’s first Black president, to the inspiration he provided to the young leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement that in the summer of 2020 produced the largest outpouring of interracial protest in support of racial justice in a generation.”

Despite such duplicitous justice declared/ justice denied realities, Malcolm X went on to become an articulate and assertive international spokesperson for human rights. Up until his assassination in front of his pregnant wife and four young daughters on Feb. 21, 1965 at the age of 39, he consistently spoke truth to power.

“separate but equal” doctrine unconstitutional. This ruling overturned the infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court case which allowed states to maintain segregated but supposedly “equal” public facilities. This justice declared Supreme Court decision was quickly subverted in 1955 by Brown V Board of Education II, a justice denied ruling which allowed states to move painfully slowly toward desegregation with the vaguely-worded “all deliberate speed” doctrine.

By 1954, Malcolm X was a prominent minister in the Nation of Islam. While much of the Black community saw Brown v. The Board of Education as justice declared, Malcolm saw it as tokenism and hypocrisy. As a proponent of Black nationalism and self-determination, he saw Brown for what it was: another example of justice denied.

Despite such duplicitous justice declared/ justice denied realities, Malcolm X went on to become an articulate and assertive international spokesperson for human rights. Up until his assassination in front of his pregnant wife and four young daughters on Feb. 21, 1965 at the age of 39, he consistently spoke truth to power.

60 years after Malcolm refuted his reputation for condoning violence by urging supporters to cast ballots before resorting to bullets, his name was invoked at a Democratic presidential convention. After Kamala Harris replaced Joe Biden at the top of the party’s ticket in the summer of 2024, delegates from Malcolm’s home state of Nebraska proudly wore T-shirts emblazoned with his image on the convention floor in Chicago, one of their native icons during a raucous roll call vote. On the political right, meanwhile, Malcolm X’s calls for Black self-improvement and economic self-reliance have also made him a hero to conservative Black intellectuals, jurists, and policymakers.

100 years after his birth and 60 years after his death, Malcolm X’s iconic persona encourages Muslims and non-Muslims alike to aspire to obey these powerful words of the Quran, “O ye who believe! Stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to God, even as against yourself, or your parents, or your kin, and whether it be (against) rich or poor: for God can best protect both” (4:135-136). ih

Jimmy E. Jones, DMin, is Executive Vice President and Professor of Comparative Religion and Culture at The Islamic Seminary of America.

BY NAHID WIDAATALLA

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz’s (Malcolm X) Letter from Mecca, written in April 1964, documents his first Umrah (pilgrimage similar to Hajj). Malcolm X, a prominent African American leader during the Civil Rights Movement, wrote of the interracial dynamics he witnessed between Muslims in the holy city. 61 years later, my own trip to Mecca during Ramadan inspired me to assess his observations and their applicability to the state of the global Ummah today.

MALCOLM X AND RACIAL UNITY

Malcolm X began his letter by emphasizing the spirit of brotherhood he felt during his trip. Worshipping with Muslims of all colors, particularly white Muslims, convinced him that “America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem.”

His experience in Mecca was in stark contrast to 20th century racial segregation in the United States. As a result, he painted Islamic unity as an antidote to anti-Black racism, but his observations don’t mean that Muslim communities are free of anti-Blackness. Unity was not an inherent trait, but rather a conscious choice made by Muslims then and now.

Like Malcom X, I observed the beautiful kindness and generosity of Muslims during my pilgrimage to Mecca. Countless women insisted I break my fast with them, sharing food and drinks without hesitation. Many created space for me to join them on their prayer mats. The sense of peace in the air makes you feel like you are exactly where you need to be.

In an earlier letter written in 1946 before his conversion, Malcolm X vented to his brother from jail about the phoniness of religious preaching he heard from Muslim inmates, calling it “just talk.” In a subsequent letter written in September 1964, X described his newfound membership in the World Muslim League as working towards “a greater degree of

cooperation and working unity in the Muslim world.” This change of heart aptly illustrates the powerful difference between hearing about something, in this case the teachings of Islam, and experiencing it for yourself.

While Mecca is a place that brings out the best in people, it also has the potential to bring out the worst. 92 million people visited the holy mosque during Ramadan this year, striving to worship as close to the Kaaba as possible. People shoving the elderly and scolding the young were common sights. These negatives, however, can sometimes be exacerbated by race.

The kafala system used in many Middle Eastern countries brings migrant workers from impoverished countries to wealthy Gulf states for cheap labor in exchange for visa sponsorship. These transitory laborers commonly face low wages, poor working conditions, and racial abuse in and outside of the workplace.

South Asian and African migrant workers in Saudi Arabia specifically face substantial discrimination. At a fast-food restaurant in Mecca, I witnessed an Arab man cut in

front of a line of people waiting to pick up their orders. He callously waved his receipt at a South Asian worker, making no eye contact. The worker, visibly intimidated, rushed to put the man’s food items into a bag and handed it to him without question.

But this exchange between the Arab patron and South Asian worker was not an isolated incident. In fact, some argue that anti-Blackness among Muslims is becoming rampant and affects all Muslims who have darker skin. It’s why people choose a mosque based on the racial background of the attendees and why interracial marriages are considered taboo by some Muslims. It’s why atrocities like the ongoing war in Sudan, shadow-funded by the United Arab Emirates, do not get much attention in the Muslim world.

The “white attitude” that Malcolm X describes is not only reserved for white people; it is a fundamental belief that a person is inherently superior to another based on the merit of their race, and because of this, their needs are more worthy of being met.

In his farewell sermon, Prophet Muhammad (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) warned, “An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab, nor a non-Arab has any superiority over an Arab; also a White has no superiority over a Black nor a Black has any superiority over a White except by piety and good action.”

In addition to race, social status can shield against negative experiences in Mecca. There is an inherent privilege in having the time, money, and physical health to travel to the holy city. When you are not hustling among sweaty crowds, relaxing and enjoying a hotel meal is a luxury. Malcolm X described his experience as a state guest, highlighting the Saudi government’s provision of “a car, a driver, and a guide,” and “air-conditioned quarters and servants in each city that I visit.” This treatment is by no means normal.

Travelers who aren’t protected by status often cook for themselves, pray on the streets, and walk long distances, often in the sun, to get to their accommodations.

The people living furthest away from the holy mosque are largely African and South Asian, while those living closer by are mostly Arab or Westerners. But inside the mosque, these differences become almost invisible. There is no way to know who is poor, rich, or famous, with everyone wearing the same white ihram and weeping the same tears as they worship. In Surah Al-Hujurat Ayat 13 (49:13 Quran), Allah says, “Indeed, We created you from a male and a female, and made you into peoples and tribes so that you may (get to) know one another.” Umrah gathers people from all corners of the earth, displaying the vastness of Islam and the diversity of Muslims.

Islam’s answer to the “race problem,” as Malcolm X called it, is an emphasis on community. This was most apparent to me during taraweeh and tahajjud prayers, with thousands of Muslims praying fervently for the people of Palestine. During my time in Medina, the second holiest city in Islam, I met a young local woman named Afnan. We sat together on the outskirts of the mosque courtyard, listening to the imam’s Quran recitation. Afnan told me she regularly visits the mosque when she can’t pray, just to listen, observe, and experience the feeling of being around so many Muslims.

In Islam, congregational prayer is an intimate communal experience. Physical touch is exercised between strangers standing shoulder-to-shoulder, while the solid, structured rows of people create a visual of unity. In a Sahih hadith narrated by Abdullah ibn Umar, the Prophet Muhammad said,

[Malcolm X’s] experience in Mecca was in stark contrast to 20th century racial segregation in the United States. As a result, he painted Islamic unity as an antidote to anti-Black racism, but his observations don’t mean that Muslim communities are free of anti-Blackness. Unity is not an inherent trait, but rather a conscious choice made by Muslims then and now.

“Whoever joins up a row, Allah will join him up (with His mercy), and whoever breaks a row, Allah will cut him off (from His mercy)” (Sunan Abī Dāwūd Book 8, Hadith 101).

When gaps in prayer rows occur, they stick out. People shy away from filling these gaps because it can be tough — moving everything to a different line, standing next to someone with a crying child, or praying beside someone who doesn’t smell great. But being part of a community means accepting inconvenience. This includes forgiving the faults of others and sacrificing personal comfort for the sake of something bigger. There may come a time when we are the ones with a crying child or become the elderly person who whispers their prayers a little too loudly.

Sacrificing comfort can also mean using your abilities to uplift another person while disadvantaging yourself. I witnessed countless strong, tall people refrain from pushing ahead in a crowd during Umrah to stay back and shield a weaker person from being shoved.

In his April 1964 letter, Malcolm X discussed the “spiritual path of truth” as a means of healing the disease of racism in America. Much of what he predicts about younger generations leading this search for truth can be seen today in the resistance of university students against institutions that enable the genocide of Palestinians. There is a present-day search for spiritual endurance in a burning world. This endurance, offered by faith, keeps hope alive while comforting the part of us that yearns for an answer to everything.

Malcolm X’s letter from Mecca is therefore a basis for reflection on the condition of Muslims today. While racism persists within Muslim communities, Islam’s unwavering messages of unity, generosity, and brotherhood stand the test of time. ih

Nahid Widaatalla is a public health professional and freelance writer/ journalist, covering social justice, Islam, digital health, and more.

BY NADIA B. AHMAD

The Muslim American com -

munity is at a generational turning point, one that calls not for cautious optimism or slow, negotiated progress, but for decisive and unapologetic agenda-setting. For too long, we have been trained to believe that our victories lie in representation, access, and reconciliation. But history has shown time and again that systems do not change through symbolic presence. They shift only when pressure is applied, power is consolidated, and narratives are boldly defined by those willing to lead with principle, not permission.

Higher education is the terrain where these battles are most critical. For decades, Muslim students, faculty, and scholars have been policed, silenced and sidelined within academic institutions. We’ve been told to wait our turn, moderate our voices, and temper our critiques for the sake of civility. But as the moral failures of the academy become impossible to ignore from complicity in genocide to the suppression of free speech, there is now a rare and urgent opening. Now is the time not to barter for influence. Now, we must set the agenda.

Post-9/11, many Muslims Americans channeled their energy into ostensibly pragmatic pathways: joining interfaith groups, forming diversity offices, running for local office. These gestures were never meant to be the endpoint, but over time, they became indistinguishable from strategy. The result was a community caught in a loop of incrementalism, reliant on validation from institutions that have continued to devalue our principles and discard our people.

The current political moment clearly demonstrates that we’ve reached the limits of reconciliation politics. The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah (628 CE) may have been prudent in a moment of tactical restraint, but our

current context demands the resolve of Uhud (625 CE). The enemy has shown its hand in the form of universities that punish students for advocating for Palestinian liberation, media outlets that suppress Muslim voices, and political parties that exploit our votes while callously ignoring our pain.

It’s time to stop asking for inclusion and start defining the terms of engagement. We are not knocking at the door of their institutions anymore. We are working to build our own.

Universities are not neutral spaces. They are ideologically saturated arenas that produce knowledge, shape public policy, and determine who is heard and who is erased. For Muslim communities, this has meant decades of surveillance, suspicion, and silencing, particularly around issues of war, empire, and the Israeli occupation of Palestine. The suppression endured by Muslims within higher education is systemic, but so too is the opportunity that it provides.

The fractures present in higher

niable. Universities are losing public trust. Faculty are disillusioned. Students are mobilized in ways not seen in decades. And administrations, caught between moral

The current political moment clearly demonstrates that we’ve reached the limits of reconciliation politics. The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah (628 CE) may have been prudent in a moment of tactical restraint, but our current context demands the resolve of Uhud (625 CE). The enemy has shown its hand in the form of universities that punish students for advocating for Palestinian liberation, media outlets that suppress Muslim voices, and political parties that exploit our votes while callously ignoring our pain.

cowardice and economic dependence, are scrambling to preserve their legitimacy. This chaos opens a space not to be managed, but to be claimed.

Muslim North Americans must no longer approach academia as a space to request acceptance into it. Rather, we should see it as a system to be redirected. We need not just more Muslim faculty, we need Muslim-led research centers that shape public discourse. We need endowed chairs that unapologetically center justice, liberation, and resistance. We need academic positions that are not contingent on funding from foreign governments or elite donors with ties to weapons manufacturers or apartheid states. We are not here to participate in the debate. We’re here to reframe it entirely.

We’ve celebrated firsts for too long: the first hijabi this, the first Muslim that. Now is the

time to move past token milestones and into strategic infrastructure building. Power is not representation. Power is control. It’s agenda-setting. It’s the ability to influence decisions before they’re even on the table. The goal is not to become leaders. The goal is to shape the ecosystem that defines leadership itself. That means controlling funding streams, launching journals, setting accreditation standards, and training the next generation of scholars not to assimilate, but to liberate.

We don’t need more panels. We don’t need more access. We don’t need to explain our humanity. We need to direct policy. We need operational autonomy. We need to assert our political, spiritual, and intellectual vision within academic spaces in the United States without compromise.

This shift in strategy must also carry over to the political realm. We can no longer afford to be a community that votes defensively, donates reactively, and organizes sporadically. We must become a force that operates from a clear and principled political compass rooted in anti-colonialism, economic justice, environmental stewardship, and global solidarity.

American political institutions will not reform themselves. We must set the terms of their reform because if we do not, others will, using our names, our identities, and our enforced silence as cover.

Now is the time to ask: What kinds of political futures are we willing to imagine? What kind of intellectual world are we willing to construct? If we continue to operate within the lines drawn for us, we’ll only replicate antiquated colonial systems that were never intended to serve us.

The political and academic power we seek is not a project targeting one election cycle or one specific political appointment. It’s a generational task. That means investing in institutions that will outlive us, narratives that will carry beyond this decade, and movements that will be resilient long after media attention fades.

We must stop building to respond. We must start building to last.

Jewish and Christian communities in the U.S., for example, built institutions, think tanks, endowed professorships, legal defense

funds, and publishing houses that operate with strategic patience and long-term vision. Muslim Americans have the capacity to do the same only if we stop expecting the existing system to validate us and start imagining structures that operate outside of it.

Uhud reminds us that even the most righteous struggle can be compromised by complacency, internal division, and premature celebrations. That is where we are now. The cost of waiting, appeasing, and compromising our principles for proximity to power has become too high. We are being watched, surveilled, and punished for daring to raise our voices. That is not a sign of failure. It is a signal that we are nearing the truth, and that the institutions around us fear it.

Uhud was a wake-up call not to retreat but to regroup with greater discipline, sharper strategy, and collective resolve.

We must make this the moment where Muslim communities decide: we will no longer outsource our values to other organizations. We will not be managed, moderated, or molded into acceptable versions of ourselves. We will write our own manifestos, define our own alliances, and set our own priorities.

To students: do not silence your convictions for the promise of internships or fellowships. You are not naïve, you are necessary.

To scholars: keep writing. Keep teaching. And when they try to suppress you, know that your work is what they feared most.

To community institutions: fund intellectual risk-takers, not political chameleons. Endow the people who dream bigger than the systems they’re navigating.

To parents: raise children who are bold in their faith and fearless in their vision.

To all of us: stop apologizing for wanting more.

This is our opening. We strive not to lead someone else’s movement, but to define our own. The systems are cracking, and we should not spend our energy trying to hold them up. We need to build something new. Let the world know the era of inclusion politics is over. The era of agenda-setting has begun. ih

BY ZAHRA N. AHMED

As anti-Muslim sentiment

intensifies across the United States, Texas stands out as a state where growing diversity meets deepening suspicion and increased targeting of Muslim communities. But rather than simply enduring it, Muslims there are responding with civic power, grassroots resistance, and a renewed sense of purpose.

Shaimaa Zayan, 41, knows this struggle intimately. As the Operations Manager at the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) in Austin, she spends her days supporting victims of Islamophobic abuse by documenting stories, advocating for policy change, and connecting community members to resources. Yet nothing prepared her for the day her work became personal.

During a routine doctor’s visit, Zayan stood quietly in line wearing her neatly-done hijab. Behind her, an older man gestured at her headscarf and asked, “Don’t you feel hot in all that?” She responded politely and moved on, but he kept going. His tone shifted from curious to accusatory when he asked whether Muslim women were allowed to speak to men. He then said with disdain, “We should convert [Muslims] to Christianity so you stop killing us.”

“His hateful words made me feel unsafe,” Zayan said. “I was afraid he might physically hurt me.”

Fearing further escalation, Zayan pulled out her phone and began recording, repeating his words aloud so others in the clinic could hear. The man eventually fell silent, but the damage was done. When her doctor examined her, Zayan showed clear physiological signs of stress, including high blood pressure and heart rate. Her individual experience is just one of thousands.

In 2023, CAIR received more than 8,000 complaints nationwide — the highest number in its 30-year history. In 2024, complaints increased by nearly 600, marking a 7.4% rise. CAIR linked the sharp rise to Israel’s Gaza Genocide, which reignited anti-Muslim rhetoric in U.S. politics and media. Law enforcement encounters surged

We all need to have the courage to speak up.”

emphasizing the need for swift action.

For Bhojani, the issue is deeply personal; his faith and life experience shape his approach to public service. He emphasized that Islam teaches the importance of giving back to the community and has made it a priority to ensure hate crimes are properly recognized and addressed — not just for Muslims but for all Texans.

However, that commitment has been tested. During his campaigns, Bhojani often faced Islamophobic rhetoric. “When I ran for office, people would repeat what they heard in the news and project it onto me,” he said, pointing to unfounded fears about Sharia law in Texas.

as well, rising from 295 in 2023 to 506 in 2024 — a 71.5% jump that coincided with the wave of student-led anti-genocide encampments on college campuses. In Texas, Muslim visibility has grown, and so has the backlash. In some cases, that hostility has turned violent. (“New CAIR Civil Rights Report Reveals Highest Number of Complaints in Group’s 30-Year History,” April 2, 2024, Council on American-Islamic Relations).

In Euless, Texas, a woman attempted to drown two Palestinian American children, a 3-year-old and a 6-year-old, in a swimming pool. Initially released on bail, she was later charged with a hate crime after community advocates linked the assault to rising anti-Muslim bigotry.

The attack quickly became a flashpoint in Texas, underscoring the urgent need to confront Islamophobia and protect vulnerable communities — especially Muslim children. The case drew widespread outrage and galvanized local leaders.