SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2021/1443 | $4.00 | WWW.ISNA.NET

MEHR: RECONSIDERING THE ISLAMIC BASIS | MILWAUKEE – A PLACE FOR MUSLIMS IN THE HEART OF AMERICA

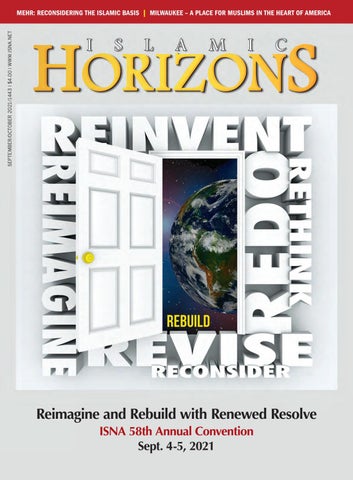

Reimagine and Rebuild with Renewed Resolve ISNA 58th Annual Convention Sept. 4-5, 2021

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2021/1443 | $4.00 | WWW.ISNA.NET

MEHR: RECONSIDERING THE ISLAMIC BASIS | MILWAUKEE – A PLACE FOR MUSLIMS IN THE HEART OF AMERICA

Reimagine and Rebuild with Renewed Resolve ISNA 58th Annual Convention Sept. 4-5, 2021