THE PROFESSIONAL VOICE OF SCHOOL LEADERS

Looking back

Looking forward

ISSUE 140 | DECEMBER 2025

AI and Schools: Shaping Our Digital Futures Agency, imagination, and leadership in an age of AI tools

The 7 Key Competencies: Equipping pupils for the world 2 8 17 6

John O’Boyle Principal, Our Lady of Mercy Convent School, Booterstown, Co. Dublin

Building Bridges Beyond the School Walls: The Nano Nagle –MTU Summer Programme Pilot 10 22

Keeping the Rumour of God Alive: Faith Leadership in Catholic Schools: A Day in the Life

Rory Healy Principal, Scoil Phádraig Naofa, Tullow, Co. Carlow

Jacinta Budhlaeir Principal of Nano Nagle School, Listowel

Dr Keith Young Assistant Professor in ICT/Digital Learning, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick

Being and becoming an Irish primary school principal: a view from the inside

Dr Anna Mai Rooney

Cross-sectoral Leadership Coordinator, Oide Leadership Division

Leading with Questions: Coaching as a Leadership Style

Coran Swayne Administrative Deputy Principal, East Cork Community Special School

The PIEW Framework - Deirdre Reidy, Principal of St. Joseph’s NS, Kilrush, Co. Clare

The Principal’s Balancing Act – Why Radical Change is Needed

- Daniel O’Connor, Principal of St Columba’s BNS, Douglas, Cork

Be Well, Lead Well: Two Principals - By Keith Ó Brolacháin, Principal & Founder of School Solutions

Breaktime Blues - Paul O’Donnell, Principal of St Patrick’s NS, Slane, Co. Meath

The Self-Compassion Wristband: A Simple Tool to Build Emotional Resilience in Children

- Robbie O’Connell, Principal of St. Brendan’s NS, Blennerville, Tralee, Co. Kerry

Legal Diary: Teacher sacked on grounds of professional incompetence loses unfair dismissal claim

- David Ruddy BL

Be Well, Lead Well – Burnout Prevention - IPPN Supports and Services And much more…

Irish Primary Principals’ Network, Glounthaune, Co. Cork 1800 21 22 23 • www.ippn.ie

Editor: Geraldine D’Arcy

Editorial Team: Geraldine D’Arcy, Brian O’Doherty and Deirdre Kelly

Comments to: editor@ippn.ie n Advertising: Sinead O’Mahony adverts@ippn.ie ISSN: 1649-5888 n Design: Brosna Press

The opinions expressed in Leadership+ do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of IPPN

DR KEITH YOUNG ASSISTANT PROFESSOR IN ICT/DIGITAL LEARNING, MARY IMMACULATE COLLEGE, LIMERICK

Every chapter in education brings a moment of change. For many school leaders, the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) feels like one of those moments, not simply another ‘initiative’, but a profound shift in how information, decisions and relationships could potentially be mediated in our schools. Yet, in the daily realities of leading schools, where administrative demands already press against every minute of the day, it can be hard to lift our eyes from the urgent to the essential.

The theme of this year’s IPPN Conference – Reflect, Reimagine, Renew – offered a useful frame to explore this. On Day 1, we looked back at what has shaped us and on Day 2, we imagined what might yet be possible. During my talk at the conference, we explored that act of imagination, not as consumers of new technology, but as professionals with agency and responsibility in deciding if, and how these tools will serve learning, inclusion and leadership.

Much of the current conversation about AI and education focuses on what it can do for us – automate routine tasks, generate learning materials, analyse data. There is potential in all of that, particularly in a system where principals must frequently spend disproportionate time running the school rather than

leading. But if we reduce AI to a means of productivity, we risk missing the deeper opportunity, to ask what kind of digital future we actually want in our schools, and who should shape it

Agency, in this sense, is not something AI gives us. It is something we already hold and must now exercise collectively. Principals, deputies and teachers are uniquely placed to guide how AI tools are introduced and interpreted within school life. That guidance can’t be left to algorithms, vendors, influencers or distant policy frameworks. It needs to emerge from our values as educators: our moral purpose, our understanding of children and our lived knowledge of what good learning feels like.

AI also prompts us to revisit what leadership itself might mean. In the age of AI tools, leadership faces new challenges – of judgement, ethics, integrity and care – and so it must be about cultivating discernment: knowing when to use technology and when to resist it; when it can support our work and when it risks undermining the human and moral dimensions of it. It is about creating a culture where professional curiosity and ethical reflection thrive. The work of leadership becomes helping our communities to think clearly and act wisely amid an abundance of data and the risks of automation.

There are obvious challenges. Schools already struggle with digital infrastructure, inequitable access and the absence of skilled administrative support. The idea of adding ‘AI strategy’ to an already impossible list may seem unrealistic. But perhaps this is precisely where imagination comes in. What if we approached AI not as another demand, but as a chance to re-design the conditions for sustainable leadership – to reclaim time, to streamline administrative work, and to re-centre our work on learning and relationships?

None of this will happen by accident. Our digital futures will be shaped either by us or for us. The choice is ours.

Reflecting on the national conference, my invitation to you remains the same: let’s reimagine what leadership looks like in an age of AI tools. Let’s be curious, critical and creative in equal measure. And let’s ensure that, whatever technologies evolve, the heartbeat of Irish education – our commitment to children, community and care – remains unmistakably human.

If you would like to get in touch with Keith in relation to this article, you can email him at Keith.Young@mic.ul.ie.

The beginning of this school year brought significant challenges for many schools and leaders and IPPN acknowledges the ongoing exceptional commitment shown by school leaders and teams in getting things back on track with minimal disruption to the children.

This issue of Leadership+ draws the 25 Years of IPPN project to a conclusion. It has been a year of reflection, reimagining and renewal. The IPPN Roadshow, which ran from January to October, was an opportunity to meet and hear from so many principals and deputy principals in every county. 25 Years of IPPN was formally launched by IPPN Chair Catríona O’Reilly in February at the IPPN Deputy Principals’ Conference. Interviews with all our past presidents were recorded and published throughout the year, with the final interview being published via E-scéal a few weeks before Christmas. It is a treasure trove and an oral history of the key milestones over the past 25 years.

The Annual Principals’ Conference in Killarney saw the launch of two key elements of the project – the epublication Looking Back, Looking Forward: 25 Years of IPPN and a commemorative video of the highlights from the past quarter century. Both were shared via E-scéal, ippn.ie and social media.

Another element of the project was the creation of an archive of key materials relating to the establishment of IPPN, its official launch and significant developments along the way. Sincere thanks to Jim Hayes and Tomás Ó Slatara for their work on the archive.

Our ongoing engagement with the piloting of administrators working in small and in larger schools has been a powerful reminder of what is possible when school leaders are enabled to focus on teaching and learning. The difference this is making to leadership effectiveness, and the sustainability of roles, is profound. Our budget submission resulted in progress on all four priority areas; we will keep pressing for all the priorities to be actioned. The launch of the brand new ippn.ie website in September, the Leading with Impact podcast in October and the Burnout Prevention resource in November add to the suite of supports in the IPPN leadership kitbag for members.

To paraphrase a crafty politician from the not-too-distant past – A lot done. More to do. On that note, the launch of the IPPN Strategic Plan 2026-2030 at the principals’ conference in Killarney signposts what’s ahead. It clarifies who we are, what we do, how we do it and why we do it. The focus is on providing an environment in which school leaders can flourish in their roles and lead effective schools, ensuring improved outcomes for the children we serve. It is an ambitious plan, and we look forward to engaging with members as we implement it over the next five years.

You’ll read about many of these projects and activities in this issue. We are delighted to showcase many excellent contributions from members on a wide range of topics –Summer Schools, the PIEW Framework, Faith Leadership in Catholic schools, AI and Schools, The Principal’s Balancing Act, Key Competencies, and Coaching as a Leadership Style, to name just a few. Also in this issue are Anna Mai Rooney’s PhD thesis summary on Being and Becoming a Primary Principal and DCU Changemaker Director John White’s piece on Doing Creativity.

We sincerely thank all of the contributors to this issue and encourage suggestions and feedback to editor@ippn.ie

See you all in 2026!

Geraldine D’Arcy Deirdre Kelly Brian O’Doherty Editor President Deputy CEO

DAVID RUDDY BL

A primary school teacher dismissed from her job on the grounds of professional incompetence, has lost her claim for unfair dismissal. This follows a Workplace Relations Commission (WRC) Adjudicator finding that the teacher was not unfairly dismissed by the Board of Management (BOM). The ruling has emerged after 10 WRC hearing days held over a two-anda-half-year period. The teacher worked as a Special Education Teacher (SET) and was dismissed from her role by the school BOM in September 2021.

The school is a three-teacher school. The teacher started teaching at the school in 2002 and in 2010 she became the main SET teacher. In her evidence, the school principal told the WRC that in October 2017, the teacher had stopped communicating with the other staff and children’s parents.

The principal said that in a small school in a local community, the situation became untenable. Parents made complaints about discipline in the teacher’s class. The principal said that in November 2017, there was ongoing evidence that the teacher was unable to manage her classroom. Outlining disciplinary issues in the classroom in February 2018, the principal alleged that children were hiding in the toilet without the teacher noticing, and children were walking around the classroom during class.

The principal further alleged that in early March 2018, more complaints were received from parents, books were

‘there is a widely-held misconception that a teacher cannot be dismissed from their teaching post. But this is not so, a teacher may be dismissed if there are appropriate grounds to do so and if Circular 49/2018 is followed.’

thrown in the classroom and belongings of children were rifled by other children, which caused upset. The principal stated that misbehaviour was met with weak and inconsistent responses such as ‘Don’t do that again, good boy.’

The principal said that the issues went beyond discipline where the teacher would concentrate on one child while the rest of the class were all talking and misbehaving.

The principal initiated a competency process for the teacher in January 2023 as per Circular 49/2018 and commenced a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) around five areas – Classroom discipline; Standard of Teaching; Engagement with Pupils; Engagement with Parents and Staff and Planning of Classwork. As part of the PIP, under the Engagement with Pupils section, the principal found three of the teacher’s pupils sitting in the staff room, having asked her if they could go to the toilet. The principal further

found that there was no improvement during the PIP. The teacher said that she thought the PIP was a complete nonsense and that the principal’s report on the PIP was also a nonsense.

An inspector was appointed by the Department of Education chief inspector to attend the school to assess the teacher’s professional competence as part of an external review provided for in the circular. The inspector made three inspection visits and found that the teacher was not performing at an acceptable level of professional competence in her role. The inspector found that the teacher’s work was poor in all areas of competency assessed.

The WRC adjudicator found that it was hard to see how the Board of Management (BOM) had any option other than to respond in the most serious way – which was to proceed to disciplinary action. Circular 49/2018 provides a statutory mechanism for a school to suspend and/or dismiss a teacher.

The adjudicator stated that ‘there is a widely-held misconception that a teacher cannot be dismissed from their teaching post. But this is not so, a teacher may be dismissed if there are appropriate grounds to do so and if Circular 49/2018 is followed.’ The adjudicator stated that given the length of time that the process took – three and a half years – she has little doubt that the impact that this process had on the teacher, the school management, the

children attending this small school and their parents ‘was difficult, attritional and damaging.’

The adjudicator held that, over time, the teacher did not improve to the level that was required to provide an appropriate education to the children in her care. The adjudicator concluded that much time was spent on recording what the teacher regarded to be unfair treatment and making bullying allegations against the principal. Insufficient time was spent by the teacher actively listening to the critical feedback that she was receiving from the principal, her line manager, and reflecting on how she needed to improve the standard of her teaching.

The adjudicator stated that if there is anything the BOM could be criticised for, it is for allowing the process to go on as long as it did. The adjudicator further stated that she was satisfied that the principal

carried out her duties in accordance with the terms of stage 1 of the circular and until she correctly disengaged from the process having completed her stage 2 report to the BOM.

The adjudicator held that the inspector observed in his report a failure by the teacher to engage with the children, inadequate support plans, inadequate targets or measured progress, disorganisation, not getting through the teaching that was required, not engaging with pupils, reading from textbooks while children became disengaged. The inspector’s findings ‘were stark’ and the teacher failed every competency that she was assessed on.

It was held that the decision by the BOM to dismiss the teacher was within a band of a reasonable response to the uncontested findings of the inspector. The BOM decision was upheld by a

Disciplinary Appeals Panel (DAP) made up of an independent chair appointed by the Minister, a representative of a management body and a trade union representative. It was held that the circular process was adhered to by both the school and the Department of Education.

The WRC hearing heard that the teacher has obtained other teaching work since her dismissal.

If you would like to get in touch with David in relation to this article you can contact him at david.ruddybl@gmail.com

JOHN O’BOYLE PRINCIPAL, OUR LADY OF MERCY CONVENT SCHOOL, BOOTERSTOWN, CO. DUBLIN

Let’s question ourselves about how we’re delivering the key competencies to ensure students are equipped for the world before them.

The recently launched Primary Curriculum Framework marks a significant shift in teaching and learning for the future. At its heart lie seven key competencies designed to equip students with the skills, values and attitudes necessary to thrive in an everchanging world.

If we look towards international schools, and the way they deliver education and their chosen curriculums, the movement towards ‘inquiry-based education’ is evident. So, to see our new framework incorporating similar strategies is a positive move.

These competencies are not mere additions to the curriculum, but essential pillars that guide teaching and learning across all subjects. As educators, it is vital that we reflect deeply and honestly: are we truly embedding these competencies into our daily practice? Whether we are working in a Junior, Senior, vertical or special school, of any patronage, we as educators should strive to prepare students for all obstacles that come their way.

So, to truly take on these competences, educators need to question themselves. Are we empowering our students to grow within themselves so as to develop lifelong skill for both inside and outside the classroom? Let’s explore the essence of these competencies and challenge ourselves to question our own practices.

Being Well is currently a major focus –for our leaders, staff, communities and

most importantly, our students. ‘Being Well’ is a central competency in the Irish Primary Curriculum Framework, emphasising children’s physical, emotional, mental and social wellbeing. Consider:

1. Are we creating safe and inclusive environments where students feel emotionally supported, valued and respected?

2. Do we provide opportunities for students to develop selfawareness, resilience and emotional regulation through our teaching and leadership?

Being Mathematical encourages students to become confident, curious and critical thinkers. Ask yourself:

1. Are we enabling students to solve problems in real-life and mathematical contexts using logical reasoning and critical thinking?

2. Are we supporting students to explore patterns, make connections and communicate their mathematical ideas with clarity and confidence?

Being an Active Citizen encourages students to understand their rights and responsibilities, value diversity and take meaningful action. It’s heartening to see how the 17 Global Goals are indirectly woven into this framework. Reflect on:

1. Are we enabling students to engage with real-world issues?

2. Are we promoting values such as fairness, empathy, inclusion and responsibility?

3. Are students empowered to share their voices and participate meaningfully in democratic processes?

Being Creative encourages imagination, curiosity and original thinking. Creativity isn’t just for the arts – it belongs across all subjects. Think about:

1. Are we providing students with opportunities to take risks, be curious, express themselves and explore new ideas?

2. How are we integrating creative thinking into all areas of learning?

As

educators, it is vital that we reflect deeply and honestly: are we truly embedding these competencies into our daily practice?

DEIRDRE

Being an Active Learner is arguably the most vital competency. It focuses on student curiosity, motivation and responsibility for their own growth. Ask:

1. Are we encouraging students to take ownership of their learning and reflect on their progress?

2. How do we support independent and collaborative inquiry and goalsetting?

Being a Digital Learner is vital in a world of rapid technological change. It focuses on using digital tools safely, effectively and creatively. Reflect on:

1. Are students using digital tools to enhance learning and express ideas creatively?

2. Are we offering experiences only possible through digital platforms – such as online collaboration and multimedia problem-solving?

Being a Communicator and Using Language underpins all other learning. This competency emphasises expressing ideas, listening actively and engaging respectfully. Consider:

1. Are students learning to articulate their ideas clearly and engage in meaningful dialogue?

2. Are we helping them use language to think critically and make meaning across contexts?

The key competencies are essential in preparing students to become adaptable, empathetic and confident citizens. They equip students to navigate real-world challenges – inside and outside the classroom – and to thrive in diverse, dynamic environments. As educators, we play a central role in making this vision a reality.

If you would like to get in touch with John in relation to this piece, you can email him at principal@ourladyofmercy.ie

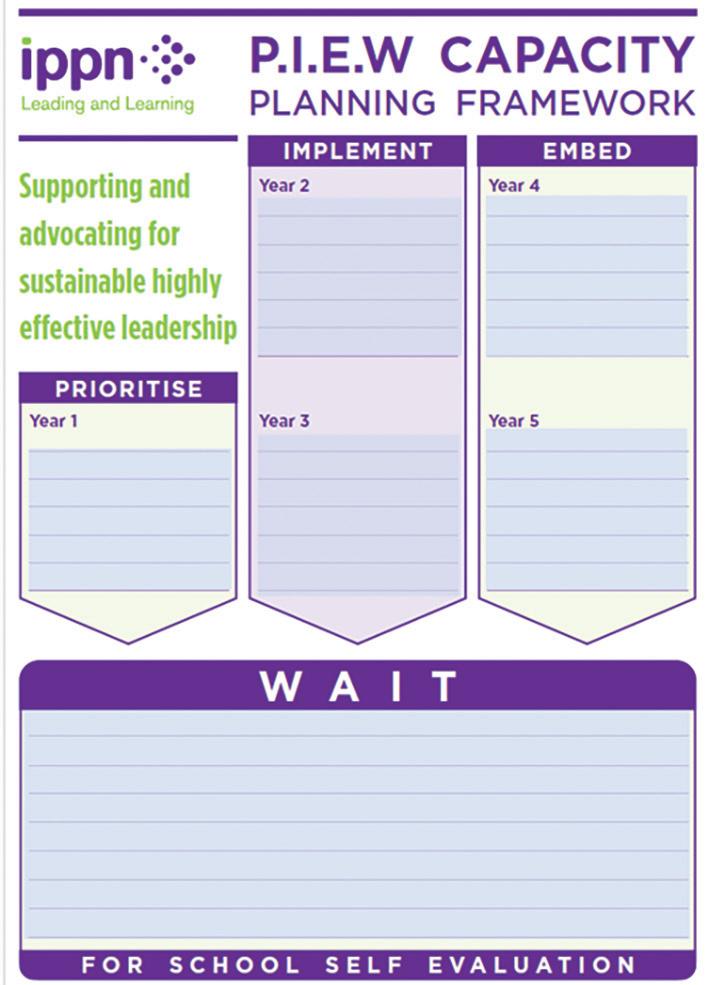

When I stepped into the role of principal in 2019, I knew that clarity of focus and structure would be vital – both for me, and for the whole school community. A friend of mine who had recently completed Deputy Principal training at the time introduced me to The PIEW capacity planning framework.

After spending some time creating a priority list, planning for the future and gathering information on initiatives that were currently in process in the school, the PIEW plan quickly became a touchstone in how I approached school development planning. A few years on, I can look back and see just how valuable it has been.

Key Takeaways from 2019–2023

Clarity of Goals: The framework kept me anchored to the targets I had set for the school. With so many competing demands in the principal’s role, having a structured process ensured nothing got lost

Continuity through Change: We had a complete change of staff over those years, which could easily have disrupted progress. Instead, the PIEW framework gave us consistency, allowing new staff to step into a school where the priorities and developmental journey were clear

Momentum for Initiatives: From new programmes to curriculum innovations, PIEW supported, not just the launch of initiatives, but their ongoing development

A Reflective Lens: Each September, revisiting what we had achieved over the previous year was a powerful motivator. Seeing the journey mapped out through the framework definitely fostered a strong sense of achievement.

Sustainable Leadership: Most importantly, PIEW gave me

confidence as a new principal. It allowed me to balance the immediate demands of the role with the long-term vision, without feeling overwhelmed!

Looking back, I see PIEW not as an administrative tool, but as a very practical support. It kept me and the school moving forward with purpose, helped navigate transitions, and provided a reliable way of celebrating success as a community. For principals starting out – or for any school seeking sustainable progress – I would strongly recommend it as a framework that truly works in practice.

To get in touch with Deirdre in relation to this piece, you can contact her at principal.creens@gmail.com

If you would like IPPN to run an online workshop with your leadership team and their emerging leaders, please contact David Buckley by email to David.Buckley@ippn.ie

Introduction and Rationale

DR ANNA MAI ROONEY OIDE LEADERSHIP COORDINATOR

I consistently find myself to be inspired by the positive and courageous leadership of Irish primary principals, from within my former role as school principal, and also my two seconded positions. The first was in the Centre for School Leadership (CSL), and the second in Oide. I endeavoured in this study, to illuminate the benefits, if any, of what is perceived to be a very challenging role. I also interrogated a perceived systemic negativity towards the role, and how bespoke professional learning and system support might alleviate this perception. Additionally, I determined to examine the role of both distributed and transformational leadership, and their potential influence on sustainability in Irish principalship. Finally, my intention was to probe the development of the person of the principal and its significance alongside their professional practice.

Irish primary principalship is interrogated in the study through the lens of the following four research questions:

1. What are the main benefits and challenges in the role of the Irish primary school Principal?

2. How does becoming a Principal influence these benefits and challenges?

3. How can professional learning mediate the challenges and enhance the benefits?

4. What is the potential of the Irish education system to support those becoming Principals and those more established in the role?

The study is an empirical study situated in an interpretivist paradigm. The data for this study was collected through fifteen semi-structured interviews and analysed using thematic analysis, (Braun and Clarke, 2022). All participants were actively engaged in system-

level leadership, which McMahon (2016, p.151) characterises as the practice of school leaders extending their influence beyond their own institutions to positively shape the broader educational landscape. The individuals involved continue to play a pivotal role in facilitating professional learning for their peers.

All Things Considered: A Tough Role with Significant Benefits

The list of benefits, all self-explanatory, that emerged from the data are as follows:

1. Work Satisfaction

2. Challenge, Buzz, Variety and Fun

3. Pride in Achievement and in School Context

4. Pride in Children, Team and Community

5. Love of Teaching, Learning and Children’s Development.

The challenges emerged as follows:

1. Challenging Relationships (mainly with other staff members)

2. School Governance (lack of support and knowledge from Boards of Management)

3. Balancing Positivity and Negativity (In particular, one participant provided a collective noun for principals, ‘a negativity of principals’)

4. Demands and Workload

(The participants spoke about the role ‘being generally unsustainable’ and the majority feeling ‘overwhelmed with my workload’)

5. Lack of System Understanding (All of them expressed their concern about the lack of understanding from the system as to how tough things are in schools accusing the system of ‘not prioritising’ and ‘not valuing the role’).

The participants suggested the following solutions:

1. Addressing Challenge for Sustainability (‘I distribute as much leadership as I can’, ‘it’s about organising yourself and being able to box in your time’).

2. Effective Leadership (‘a clear vision’, ‘involve others in the map-making’, ‘comfortable in the role of leading learning’).

3. School Culture and Values (‘being true to the integrity of the school’, ‘lead according to your own values and beliefs’, ‘the courage to act, the moral purpose’) Transformational Leadership (Wilson Heenan et al. 2023).

4. Distributed Leadership (‘we need to start re-educating people on what distributed leadership is and what it looks like on the ground’, ‘they [teachers] do not understand leadership . . . they don’t see themselves as leaders’).

Setting the Scene:

Principalship by Accident or Design

1. Circumstances of Appointment and Life Experiences

None of the fifteen participants in the study actually planned their career progression towards principalship. Three applied due to being unhappy in their schools, four applied due to needing to move location for personal reasons, and seven applied to principalship because the position came up very early in their careers and they were encouraged to apply. One participant took on the role in an acting capacity when their principal went out on secondment.

Eight had no prior leadership experience, four had been deputy principals previously and three

came from middle leadership. All agreed that they had a significant lack of knowledge about what the role entailed. As one participant put it, ‘I had youth, naivety and innocence on my side. I thought I was the bees’ knees to be appointed at 30.’ The participants’ backgrounds lent themselves to their individual decisions to apply for the role, with all of them having a deep interest in education and leadership from early life and teaching experience, a phenomenon described as’ anticipatory socialisation’ for the role (Murphy, 2023:42). As previously mentioned, they were encouraged to apply by colleagues and family members. One participant articulated that his colleagues ‘lit the spark in me’ while another was encouraged by a partner, ‘I think you’d be good; I think you should go for it; you have the support of people.”

2. Early Experiences

All of the participants experienced significant challenge in their early years in the role, and all of them admitted to significant learning on the job.

3. Professional Learning for Newly Appointed Principals

Mentoring and coaching are key to sustainability in principalship, according to the participants, as is engagement with the Misneach programme and the PDSL.1 Their main request was a formal shadowing programme for new principals. ‘I also think there needs to be a programme where people just come in and follow me around for a few weeks to see what this looks like ...’

The Person of the Leader and Opportunities for Development

The study unveiled the importance of:

1. Finding a Balance to Avoid Excessive Emotional Labour

The participants maintained that a balance is key between sharing with their staff and being the ‘solid anchor’ for them. They felt it necessary to suppress emotions ‘to facilitate the development of the school and others’ while also contending that being stoic is not the answer – ‘it’s just not sustainable’

2. Life Lessons and Experience

The participants all agreed that ‘you get more resilient over the years’

...the study advocates for significantly more focus on the development of the person of the leader, the time and space to network and a refocus on the benefits of clusters, communities of practice and on-site learning.

and that the best option is ‘to move a little closer to my own values’ (authentic leadership, Lynch et al. 2022) and to ensure ‘an emotional core of your own that you can tap into’. There was a strong sense of anxiety about future careers and the capacity to sustain themselves. As one articulated, ‘we’re currently getting applicants for the role who aren’t ready, who aren’t able... it’s a really dangerous cycle to be in on a systemic level.’

Professional Learning and System Supports

In this final theme, the sub themes that emerged include:

1. Impact of System Leadership (all the participants are involved in the facilitation of leadership professional learning for their colleagues, and one said that it is ‘where I get most of my energy from’)

2. Quality Professional Learning (participants declared the importance of prioritising professional learning both for themselves and their staff members and advocated for more focus on the development of the person of the leader)

3. The Benefits of Networking (participants were adamant about the importance of networking, urging the system to acknowledge and formalise it).

Conclusion

This study highlights the benefits of principalship and the importance of a principal’s beliefs and values being

aligned with those of their school to achieve authentic leadership (Lynch et al. 2022) and transformational leadership (Wilson Heenan et al. (2023). It also presents the challenges of principalship, and potential solutions like distributed leadership, which needs further development, and a focus on the person of the leader. The situational circumstances around becoming a leader comprised the most surprising additional knowledge from the study, specifically people’s willingness to take on the role with a significant knowledge deficit. Rather than a formal preparation programme, the study’s findings focus on the potential of job shadowing to alleviate this significant recruitment issue.

From the point of view of professional learning, the study advocates for significantly more focus on the development of the person of the leader, the time and space to network and a re-focus on the benefits of clusters, communities of practice and on-site learning. Due to being appointed at a young age, the advantage of an optional step-down facility is introduced. Finally, although system supports emerge as being much appreciated by the participants in this study, they are overshadowed by overwhelm and a strong sense of disconnect within which schools do not trust the system due to constant curricular and legislative change demands. The study concludes with a strong sense of the need to shout ‘stop’ and to model a more sustainable approach to school leadership in consultation with schools. The need to pause, reflect, discuss and network in an Education Convention is suggested, a timely prediction perhaps of current system plans.

Anna Mai’s research is available at the following link:

References available by request to editor@ippn.ie

1 The Oide Post Graduate Diploma in School Leadership [PDSL] is jointly accredited by the University of Limerick [UL], the University of Galway [UoG] and University College Dublin [UCD]. It is a part-time [18 months] blended programme based on the four domains of LAOS (2022). https://oide.ie/ leadership/home/post-graduate-diploma/

RORY HEALY PRINCIPAL, SCOIL PHÁDRAIG NAOFA, TULLOW, CO. CARLOW

It is 8:45 on a wet Monday morning. A parent approaches me at the school gate, frustrated about her child’s behaviour. A teacher stops me in the yard to ask about a new literacy resource. A boy clutches my sleeve, eager to show me the prayer he has written in class. In these moments, I am reminded that leadership is not just about timetables, budgets and inspections. It is also about holding the faith dimension of our school gently but firmly: helping our boys, their families and our staff encounter something greater than themselves.

This is what I mean by faith leadership: not an added burden, but the thread that runs through everything else.

The late Jesuit theologian Michael Paul Gallagher spoke of ‘keeping the rumour of God alive.’ In an Ireland where secularisation is accelerating and surveys show growing calls for non-denominational education, Catholic schools remain one of the most common places where children and families encounter this rumour. As principals, we are uniquely placed to ensure it is not a faint whisper, but a living and hopeful message.

Faith leadership weaves together three dimensions of school leadership:

1. Managerial – ensuring systems and governance are in place.

2. Instructional – leading teaching, learning and curriculum.

3. Faith/Ethos – nurturing Catholic identity, modelling Gospel values, and witnessing to God’s presence in community life.

When these overlap, faith leadership is not an ‘add-on,’ but an infusion of ethos across all aspects of school life.

Educationalist Gerald Grace describes

Educationalist Gerald Grace describes the importance of ‘spiritual capital’ in Catholic schools: a deep well of meaning, purpose and identity. In times of change and pressure, this capital can act as both compass and resilience.

the importance of ‘spiritual capital’ in Catholic schools: a deep well of meaning, purpose and identity. In times of change and pressure, this capital can act as both compass and resilience.

For principals and teachers, faith leadership offers:

A clear moral purpose, anchoring leadership beyond paperwork

A shared vocabulary for ethos with staff, parents and Boards

A framework for inclusion, where Gospel values underpin welcome and diversity.

Faith leadership is not about perfection. It is about creating spaces for reflection, prayer and values-led decision-making. Some practical steps include: Staff reflection: a short silence or Scripture at meetings

Ethos in policies: linking Catholic values to inclusion and wellbeing

Visible witness: modelling kindness, integrity and servant leadership

Student voice: involving children in liturgy, assemblies and social justice

Peer support: connecting with fellow principals for encouragement.

These are not extras – they are the lifeblood that keeps Catholic schools distinctive and nurturing.

The challenges are real. Many teachers identify as non-practising Catholics. Public debate increasingly questions the place of religion in schools. Principals can feel exposed when articulating ethos. And yet, there is opportunity. Pope Francis reminds us in Evangelii Gaudium that Catholic schools are not relics of the past but ‘living laboratories of Gospel joy.’ They are places where faith and reason, culture and Gospel, encounter and dialogue. As lay leaders, we are at the forefront of this mission – not carrying the torch alone, but together with parents, teachers, Boards and the wider Church.

Faith leadership is not about adding another item to an already overflowing to-do list. It is about finding joy and resilience in the heart of the mission.

As one principal told me: ‘Faith leadership reminds me why I do this job. It keeps the heart alive when the paperwork threatens to take over.’

So tomorrow morning, at the school gate, in the classroom, or in the staffroom, remember: you are not just a manager or administrator. You are also a keeper of the rumour of God – a quiet but vital witness to hope in your community.

If you would like to get in touch with Rory in relation to this piece, you can contact him at principal@tullowboysns.ie

Primary School Teacher feedback

Over the past 12 months, IPPN has been acknowledging and celebrating the people, milestones and developments that have shaped the organisation we are today. Here, we summarise what has been happening throughout the year:

The 25 Years of IPPN project was launched at the IPPN Deputy Principals’ Conference in Galway on 13th February 2025 by IPPN Chair Catríona O’Reilly, almost 25 years to the day after the formal launch of IPPN in Dublin Castle on 10th February 2000.

The IPPN leadership team went ‘on the road’ and met members in all 31 city/ county networks between January and October. It was an opportunity to celebrate the 25-year milestone (with special cake!), share a little of IPPN’s history, as well as to deliver a wellreceived seminar on ‘Making Leadership Doable’. It was also a tribute to Jim Hayes and Seán Cottrell’s roadshow in the lead-up to the launch of IPPN back in the late 90s when they were both fulltime in school and driving the length and breadth of the country meeting principals and getting them involved in a fledgeling network of principals.

As part of the roadshow, tremendous work was done to link every school leader who wished to join a Support Group with one in their area – at least 700 more school leaders are now part of a local support group.

Thanks to the diligence and hard work of Jim Hayes and Tomás Ó Slatara, IPPN now has an archive of key materials relating to the establishment of IPPN, its official launch and key milestones along the way. The archive materials are available to view in the IPPN Support Office in Glounthaune, Cork.

In this series of interviews, IPPN past president Damian White interviews each of IPPN’s presidents from its founding in 2000 to its 25th anniversary in 2025. These interviews provide an exceptionally rich oral history of the organisation in its first quarter century. See

A commemorative ePublication was launched by IPPN President Deirdre Kelly on 12th November at the annual

principals’ conference in Killarney. It includes photographs from ‘memory lane’, inputs from members, critical friends of IPPN, stakeholders and key IPPN staff, as well as the voice of the child and links to all the Past President interviews. The official title is ‘Looking Back, Looking Forward: 25 Years of IPPN’ with the foreword written by founding president, Jim Hayes.

A commemorative video was prepared for the principals’ conference, which includes radio and TV footage from the launch of IPPN in 2000, clips of conference speeches over the years, photographs of IPPN Presidents, critical friends of IPPN through the years and key IPPN staff.

The first episodes of the new IPPN podcast ‘Leading with Impact’ were issued to coincide with the start of

IPPN President Deirdre Kelly with Donegal school leaders at their IPPN City/ County AGM

the new school year: podcast host Brian O’Doherty in conversation with IPPN President Deirdre Kelly, psychotherapist Sinéad Kennedy, principals Caroline Sheill and Gemma Maher. It is fitting that 2025 is the year we get the podcast up and running, with the first discussions around this logged back in 2007!

As we celebrate the past 25 years, it is important that we are well placed as an organisation to continue the work of our founders in an ever-changing leadership landscape. ‘Leading for Impact – IPPN’s Strategic Plan 20262030’ was launched at Conference by IPPN Chair Catríona O’Reilly on Friday 14th November. As we look to the future, it clarifies who we are, what we do, how we do it and why we do it.

In challenging ourselves to deliver on the ambitious strategic objectives in

this plan, IPPN aims to collaborate with our members and the wider education system to provide an environment in which school leaders can thrive and flourish in their roles and lead effective schools ensuring improved outcomes for the children we serve.

A lunch for all former and current members of the IPPN Board of Directors (and the then Executive Committees) will be held at The Gresham Hotel in Dublin on 10th December. Bringing together all the leaders who helped to shape IPPN over the past quarter-century is a fitting tribute to their collegiality, professional generosity and volunteerism and a lovely way to conclude the 25 Years of IPPN commemorations.

Here’s to the next 25!

How can young children learn to think creatively, take initiative, and make a difference for others? We explored this question through a 12-week project combining Project-Based Learning (PBL) and Design Thinking – a creative, structured approach that helped pupils learn by doing. The result was an example of Entrepreneurial Education in action, where students developed ideas that created real value for others in our school community.

Entrepreneurial Education

Entrepreneurial Education (EE) is not about teaching children to start businesses. It’s about developing mindsets – creativity, curiosity, resilience, and the ability to see opportunities and act on them. When pupils identify problems, design solutions, and create something that benefits others, they are practising entrepreneurship in its truest sense: creating value through learning.

In the context of primary education, EE encourages learners to take initiative, collaborate and reflect. It builds confidence, critical thinking and empathy – skills that prepare children to thrive in an uncertain and changing world.

Our school has a strong tradition of thematic, project-based learning. However, recent professional development in Innovation and Creativity in Education deepened our understanding of how PBL, Design Thinking and Entrepreneurial Education interconnect.

Staff workshops on psychological safety, student and teacher agency, helped teachers and pupils feel safe to take risks and learn from mistakes. This culture of trust provided grounds for creativity and inclusion.

John Brennan’s article in Issue 139 offers a comprehensive overview of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) – the framework that ensures all learners can access, engage with, and demonstrate their learning. Our experience shows how PBL and Design Thinking can bring UDL to life in the classroom.

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is an active approach where pupils explore real-world questions and challenges, applying what they learn to produce a meaningful outcome. It connects learning across subjects and promotes deep engagement.

In our case, pupils from 1st and 2nd class worked on a project to strengthen communication (as identified through the process) with our special class for children with autism, the Oak Room. Their goal was to design something that could help everyone connect.

Through PBL, learning became purposeful: maths, language, art, and SPHE were integrated into one meaningful experience. Every pupil had a role – researcher, designer, communicator – allowing different strengths and learning styles to shine.

Design Thinking is a process used to solve problems creatively. It involves five stages: empathise, define, ideate, prototype and test Students began by visiting the Oak Room and interviewing staff to create understanding. They identified empathy and inclusion as key themes, then brainstormed ways to help. Working in self-chosen groups, they designed posters, bracelets, and necklaces using Lámh sign language to help everyone communicate.

Reflection was built into every session using the “What? So What? Now What?”

framework. Pupils loved this part, proudly leading discussions and suggesting improvements. Learning felt meaningful and fun.

Learners showed sustained enthusiasm and focus throughout each stage. Students couldn’t wait for their design thinking time. They demonstrated resilience, teamwork, and empathy. When testing their creations, both classes were visibly excited –communication became play, and inclusion became natural.

Teachers observed greater confidence, creativity, and collaboration. The project supported mixed-ability learning and mirrored the UDL principles John Brennan describes: multiple ways to engage, represent, and express learning.

Most importantly, pupils realised that learning can make a difference – that their ideas could bring joy and connection to others. This is entrepreneurial education at its heart.

This project reminded us that entrepreneurial learning begins with empathy and curiosity. When children see the value their ideas create, they become active, responsible learners.

Our next steps include integrating Design Thinking into the new Primary Mathematics Curriculum, exploring flexible learning spaces, and continuing to nurture creativity and inclusion across the school. We are also using design thinking in our Creative Schools journey as it strongly compliments the Lundy Model.

For schools beginning this journey: start small, build staff confidence, and trust your pupils. With the right support, you’ll be reminded that every classroom can be a place where creativity and care create value.

You can contact Ciara about this article by email to ciarabreen@screenns.ie or www.linkedin.com/in/ciara-breen

Stepping into Leadership is a programme designed to support and guide the new school leader to manage self, reflect on their leadership role, assist their personal development and may often be a lifeline in challenging times.

Reflections on Leadership

Fortnightly Reflections on Leadership are issued to newly appointed and acting school leaders on immediate appointment throughout their first two years in the role. The emphasis is on personal leadership development as well as signposting where to access information and prompts to assist with planning.

Planning prompts issue to all school leaders on a weekly basis via our E-scéal e-newsletter. These are shaped around the rhythm of the school year and the specific issues that arise at particular times. Here you can access the most recently issued planning prompts that have issued, from September through to June.

Useful Links

This webpage includes links to

• CPD provided by Oide, the Support Service for Teachers and School Leaders

• Key publications – frameworks, guidelines and resources by the DEY, NCSE, NCCA and Tusla.

New and acting leaders can also avail of the wide range of other supports and services available to all IPPN members, which are accessible through www.ippn.ie. This includes

• Leadership Tools such as the Guide to the leadership of teaching and learning, the Leadership Reflection Log, and PIEW – the capacity planning framework

• Sample Policies provided by school leaders to be tailored to each school’s context

• Leadership Support – one-to-one, confidential advisory service provided by a team of skilled, experienced school leaders. This is collegial support and guidance of a non-directive and non-legal nature

• Resources Bundles – this is where school leaders will find the answers and supporting documentation relating to the most common queries they encounter in the day-today leadership and management of their schools

• Resources – A range of template resources has been developed and shared by school leaders. They have been categorised with reference to the four domains of the quality framework for leadership and management

• Leadership+ – IPPN publishes five issues of Leadership+ per school year, showcasing members’ own research, the work IPPN does on behalf of members, and external perspectives on matters of relevance to school leaders – researchers, policy-makers, stakeholders, education thought leaders, etc.

• Local Support Groups – IPPN is a network of school leaders and local support groups are the beating heart of that network, underpinned by the principle of the wisdom of the collective informing the practice of the individual. IPPN is committed to ensuring access to a local support group for every principal and deputy principal who wishes to be in one.

• Be Well, Lead Well – A key focus for IPPN is the importance of the wellbeing of school leaders and its relevance to school effectiveness. We encourage all school leaders to prioritise self-care and have collated a range of tips, strategies and activities. Take a minute or two out of your day for yourself and find the strategies and tips that work best for you.

• Events – IPPN hosts local, regional and national events for school leaders each year including conferences, city/county network annual meetings, a comprehensive online summer course and various workshops/seminars. More than 2,500 school leaders participate annually at these events.

• E-scéal – This weekly e-newsletter is issued every Thursday afternoon through the school year to principals and deputy principals. It is a vital ‘one-stopshop’ resource, providing key information from across the education sector. The website hosts 12 months of E-scéalta.

DANIEL O’CONNOR PRINCIPAL OF ST COLUMBAS BNS, DOUGLAS, CORK

‘I loves me job.’ That’s the phrase that often comes to mind when I think about being a principal. The truth is, though, the job as it currently stands is unsustainable. The title príomhoide means head teacher – but that’s a fantasy most of us rarely get to live out. More often than not, we’re head cleaner, head fundraiser, head financial consultant, head legal expert… the list goes on. And yes, I’m sure you get the picture.

On the rare occasions when I do carve out that magical window to truly focus on teaching and learning, the energy and satisfaction it brings are incomparable. But here’s the harsh reality: less than 10% of my working life is spent as the actual ‘head teacher.’ Imagine if we could bump that figure up to even 50%. The ripple effect – on staff morale, on students’ experiences, and on the broader profession – would be transformative.

Like many others, my first instinct to deal with the crushing workload was to work harder. Longer hours, fewer breaks, sacrifices to family time, hobbies and eventually, my own health. It’s a trapdoor that countless principals fall through. The problem is, you don’t realise it’s a trap until you’ve hit the bottom. For me, it took hefty doctor’s bills and a wake-up call to accept the truth: working myself into the ground was not a sustainable strategy.

This painful lesson forced me to ask the harder questions. What supports do we need to lead schools effectively? What changes must happen if we want to protect not just our health but also the profession itself? The implementation of the new Primary School Curriculum is a fantastic opportunity, and I’m genuinely excited by its potential. But I also know that unless we’re properly supported, this ‘opportunity’ could push many of us beyond breaking point.

...the scheme pairs Irish principals with colleagues abroad for short reciprocal visits. The idea is beautifully simple: step away from the mountain of compliance and paperwork and spend time immersed in what leadership in education is meant to be about.

The evidence is already there. In two principal groups I’m involved with, about half of the members who were leading schools last year are no longer in the role today. These aren’t people leaving because they dislike the job – they’re stepping back because the relentlessness of it all simply became too much.

So where does that leave us? For me, it led to exploring alternatives – real, practical ways of lightening the load while deepening my focus as a head teacher.

It’s worth acknowledging that IPPN has already done considerable work to support school leaders in their role as leaders of learning and in building capacity to lead effectively. Among the tools and frameworks developed are:

• The Guide to the Leadership of Teaching and Learning

• The Leadership Effectiveness Reflection Tool

• PIEW – The Capacity Planning Framework.

These resources are designed to help principals reflect, plan and grow

as instructional leaders. For those interested, they can be accessed at ippn.ie under Supports & Services –Leadership Tools (login required to view/download).

In addition to these resources, IPPN is also piloting the Principal Exchange Programme, which has proven to be one of the most rewarding professional experiences of my career.

Run as a pilot by IPPN, the scheme pairs Irish principals with colleagues abroad for short reciprocal visits. The idea is beautifully simple: step away from the mountain of compliance and paperwork and spend time immersed in what leadership in education is meant to be about. It’s a chance to reflect, to compare systems, to learn new approaches, and – crucially – to rediscover the joy of teaching and leading.

My own exchange took me across the Atlantic to Toronto, Canada, but that’s a story in itself. What matters most here is the principle behind the programme: making space for reflection, collaboration and professional growth. Because unless we rethink the supports for principals – and reimagine how leadership development is structured – the future of the profession will be in jeopardy.

For too long, the solution to the principalship crisis has been to ‘just work harder.’ It’s time to get serious about what actually sustains us as leaders. Otherwise, the phrase ‘I loves me job’ will become something principals say with irony rather than conviction.

If you would like to get in touch with Daniel in relation to this piece, you can send him an email at danieloconnor@stcolumbasbns.ie

CORAN SWAYNE

ADMINISTRATIVE DEPUTY PRINCIPAL, EAST CORK COMMUNITY SPECIAL SCHOOL

‘Coaching is unlocking people’s potential to maximise their performance. It is helping them to learn rather than teaching them.’

(Whitmore and Gaskell, 2024, p. 13)

Applying for the position of Administrative Deputy Principal in a special school was daunting. My background had been entirely in a mainstream primary setting, where I taught for seven years while holding a middle leadership role. What gave me confidence was the knowledge I had gained through studying and practising coaching, and the realisation that leading was possible without having all the answers or being the expert in every situation. That realisation captures the potential that coaching brings to school leadership.

The IPPN Sustainable Leadership Project highlights that principals and deputies are at a tipping point, with workload, administration and emotional demands stretching capacity. Developing a coaching skillset can be one way to make leadership more sustainable. With educative coaching still in its infancy in Irish education (Moynihan, 2025), many leaders will already have experienced Oide Leadership Coaching, which offers one-to-one support to help school leaders manage complexity, renew focus and grow coaching cultures.

When I stepped into senior leadership, I quickly saw how a coaching mindset could make the role more sustainable. Coaching can take many forms in

schools, from a way of being to a professional learning approach, but for me it has become a way of leading.

We often think of questions as a way of gathering information. When supporting a colleague, our questions may help us understand a situation so we can draw on our own experience and offer advice. Yet that approach, while well intentioned, is not sustainable. Providing advice can create dependency, limit thinking to our perspective, and reduce our colleagues’ ownership of solutions. Coaching invites us to use questions differently. When we ask better questions, we help colleagues gain clarity, reduce reliance on our input, and find their own way forward.

Some simple ways to start include:

Asking more what questions and fewer why questions

Using open rather than closed questions

Helping colleagues draw on their own past successes.

Even small shifts in how we talk to colleagues can make a difference. I have found that simply pausing during problem-solving and asking, ‘What do you think?’, often opens a richer conversation than jumping straight to advice.

Listening effectively means more than making eye contact or reducing distractions. It requires genuine curiosity and the discipline to resist our natural instinct to be the fixer. As leaders, we often listen with the intent to respond or take control of the problem. Coaching invites us to listen differently: to let go of that need to fix, to stay present, and to listen for

the glimmer of a solution or a trace of past success in what our colleague is saying.

In a leadership context, this might mean:

Allowing silence instead of rushing to respond

Listening for what is working, not just what is wrong

Noticing moments of strength or insight in what the other person says.

When we allow time for silence and resist the urge to fix, we make room for others to find their own solutions.

School leaders and teachers now have more opportunities to develop and apply these skills in daily practice. University College Cork’s Postgraduate Diploma in Coaching in Education, Ireland’s first universityaccredited programme, complements Oide’s leadership coaching service by equipping educators to embed coaching as a sustainable and transformative practice.

This article draws on ideas from John Whitmore, Christian van Nieuwerburgh, Michael Bungay Stanier and Joseph Moynihan, along with recent work by Oide and IPPN.

Coran is also a Lecturer in Educational Leadership and Coaching in Education at University College Cork.

Coran can be contacted at coran.swayne@corketb.ie

DR JOHN WHITE DIRECTOR OF THE DCU CHANGEMAKER SCHOOLS NETWORK

Edward de Bono once wrote: ‘Creativity is the most important human resource of all. Without creativity, there would be no progress and we would be forever repeating the same patterns.’

The term creativity has received much attention in recent decades and frequently appears in discourse related to change. For example, it is cited as one of the seven key competencies of our primary curriculum framework and is also a key ‘stakeholder’ in modern discourse about 21st-century skills needed for success in our modern world.

Creativity is also one of the four key pillars which underpin the work of the DCU Changemaker Schools’ Network (DCU CSN – ). The other pillars are teamwork, leadership and empathy. Over the past five years, our expansion and development has afforded us many opportunities to research, disseminate and explore the idea of creativity within a changemaker context. A

Changemaker is someone with the skills and confidence to lead change in their home, school, community and their own lives. Obviously, creativity is a core factor in the actual activities of changemakers.

Key to our work in examining creativity has been a focus on practical and ‘user-friendly’ ways to actually ‘do creativity’. The term itself has multiple interpretations. Our research, collaborations, site-visits, clusters of interest, workshops, best practice

explorations and conference this year (Creativity and Citizenship in DCU Changemaker Schools) has afforded us opportunities to actually examine how changemaker schools ‘do creativity’. We have gleaned the following insights into ‘doing creativity’ within a changemaker context.

In DCU CSN schools, creativity was enhanced by the formal and informal celebration of creative ‘products’ and ‘processes’, and a notable tolerance

for ‘mistakes’ and ‘giving it a go’ (Sternberg, 2019). Such processes were also underpinned by teacher agency. Providing opportunities for children (and teachers) to reflect on their own creative processes also serves as a valuable tool for its further promotion.

Philosophical and Pedagogical approaches

The following philosophical and pedagogical approaches are valuable in the promotion of creativity:

1. Fostering pupil voice, pupil dialogue, discussions, leadership and autonomy

2. Teacher openness to going off script and ‘bringing learning down another, unknown route.’

3. The ‘teacher does not have to be the creative one.’

4. The development of students’ capacities to ‘lead’ and ‘make connections’.

5. Identifying and using various ‘creative spaces’ which afford students opportunities to explore, imagine and create. For example: outdoor learning and ICT ‘spaces’

6. Recognising the value and importance of play, discovery learning and ‘hands-on’ activities.

7. Using student collaborative learning and concrete materials

to foster imagination and reduce ‘chalk and talk’ pedagogical approaches.

8. Using teacher collaboration to plan creative lessons and learning activities.

9. Teacher modelling of ‘thinking creatively’ and acting ‘creatively’.

10. Grounding creative activities in the students’ own experiences and environment.

11. Using creativity as a valuable and viable tool for inclusion.

12. Appreciating that creativity can have a ‘big’ audience (e.g. a school drama production) and a small audience (e.g. a student’s homework).

13. Reshaping students’ perceptions of teachers, where a student may say: ‘what does the teacher want this to look like?’

14. Encouraging children’s creativity can have a self-fulfilling effect, where teachers’ own creativity is developed.

15. It is important to realise that creativity can be intertwined with ‘measurable attainment’.

16. Children can be reluctant to ‘give it a go’ and need to be taught it’s ok to get it wrong.

17. It is valuable to promote ‘perseverance’ as a ‘mindset’ in the classroom.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most interesting feature of our work on creativity lies in its connections with fun and play. As Albert Einstein once said: ‘creativity is intelligence having fun’. Children in the DCU CSN are quick to point out the ‘fun’ they have while engaging in creative processes. Such processes can equip them with skills such as perseverance, tolerating uncertainty, playing with possibilities, challenging assumptions, teamwork and leadership. Skills as changemakers for both themselves, and the wider world!

References:

Sternberg, R.J., 2019. Enhancing people’s creativity. The Cambridge handbook of creativity, pp.88-104.

John can be contacted at john.white@dcu.ie should you wish to get in touch with him in relation to this article.

IPPN is delighted to present a vital new resource developed exclusively for IPPN members – Be Well, Lead Well: Burnout Prevention – available now via the IPPN website.

This is the culmination of over a year’s work in responding to the challenges posed by the results of the health and wellbeing research, commissioned by IPPN and conducted by Deakin University. The research conclusions were sobering and confirmed the negative impact leadership practice can have on the health and wellbeing of school leaders. Far too many school leaders are close to or already experiencing burnout.

This, and the other findings, prompted the Advocacy and Communications committee of the National Council to develop a position paper on school leader wellbeing and out of which emerged our Be Well, Lead Well campaign. The underlying premise is that you cannot possibly lead effectively if you are not well enough to do so.

As part of the campaign and to further promote your wellness, IPPN commissioned accredited psychotherapist and mental health consultant Sinead Kennedy to develop a digital series exclusively for IPPN members. Be Well, Lead Well: Burnout Prevention consists of 9 bite-sized videos that can accessed and digested at your own pace, whenever it suits you. The emphasis is on prevention by recognising the signs and symptoms of stress and burnout, with practical tips and downloadable resources.

The 9-step Programme

The programme is set out in 9 sequential steps, each of which has a clear set of key takeaways

1. Understanding burnout – This section gives school leaders a clear, evidencebased grasp of what burnout is, how it differs from everyday stress, and why leaders are at higher risk. It offers quick self-check frameworks (trafficlight cues, locus of control) and practical steps to reduce risk, improve recovery and build resilience.

2. Resetting the nervous system – helps school leaders understand how their body’s stress response works and why regulating the nervous system is key to managing pressure and preventing burnout. It simplifies complex neuroscience into practical, everyday tools that leaders can use to move from “fight, flight, or freeze” back into calm, focus, and connection. Through body-based techniques like breathwork, grounding and microresets, participants learn to bring their thinking brain back online, widen their window of tolerance, and improve both personal resilience and their ability to co-regulate staff and students.

3. Improving sleep and emotional recovery – helps school leaders break the vicious cycle between burnout and poor sleep by understanding how stress disrupts rest and recovery. The module provides practical strategies to calm the nervous system, improve sleep quality, and introduce different types of rest – physical, mental, sensory, emotional, social and creative. Leaders will learn how to create healthier sleep habits, reframe anxious thinking at night and use acceptancebased approaches to reduce pressure around sleep, supporting deeper recovery and resilience.

4. Managing depressive symptoms – supports school leaders in recognising and responding to low mood, fatigue and loss of motivation that can accompany burnout. The module explains how depressive symptoms often pull leaders “below the window of tolerance” and introduces body-based upregulation tools, behavioural activation strategies, and CBT techniques to break the cycle of withdrawal and negative thinking. It also explores worry management, gratitude practices and attentional shifts that help leaders re-engage with energy, focus and balance.

5. Setting healthy boundaries to prevent burnout – shows school leaders how to set clear, valuesaligned limits that increase resources and cut hindering demands –

especially when demoralisation (value conflict) is the real driver of burnout. You’ll learn why boundaries feel hard, how to defuse guilt, and how to use simple scripts and system guardrails so “clear is kind” becomes a daily habit.

6. Managing relationships – gives you practical, research-informed habits to protect trust under pressure – how to spot stress spillover, communicate needs cleanly, handle conflict without escalation, and use small daily interactions to co-regulate your team and keep the “emotional bank” solvent.

7. Reconnecting with purpose – helps school leaders turn meaning into a practical burnout buffer. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (autonomy, competence, relatedness), you’ll surface your “why,” spot purpose debt (the gap between what matters and what fills your diary), and use fast exercises – Peak Evidence Scan, values writing, ACT’s Clarify–Unhook–Accept–Choose, and narrative re-authoring – to turn purpose into small, scheduled actions that restore energy and direction.

8. Supporting others with burnout prevention – gives school leaders a practical playbook for spotting strain early, holding safer conversations and shaping day-today behaviours that lower burnout risk across the team. It centres on psychological safety, clear communication, small workload guardrails and simple coaching tools leaders can use this week.

9. Integration and SMART goal setting – pulls all of the previous steps together and provides guidance to establish goals and techniques to prevent burnout.

Sinéad features in episode two of Leading with Impact: The IPPN Podcast, which is also available at ippn.ie and wherever you access podcasts.

You can contact Sinéad by email at sinead@here4youtherapy.com

One day, a number of years ago, the perfect storm developed in our school. It was an educational institution’s worst nightmare borne out: Friday the 13th of the month, a full moon in the lunar calendar and a windy day. All educators know from bitter experience that any of the above phenomena, on their own, discombobulate the internal workings of school-going children. Combined, it was total carnage.

I could only offer thoughts and prayers to the staff heading out on yard duty until I realised that I was also on the rota. As I got to the door, I met a usually calm and sensible Special Needs Assistant, her pupils fully dilated. ‘I’ve never seen the likes of it’ she shrieked. ‘They’re like squirrels at a house party!’ I braced myself and entered the fray.

It’s important to state that, while our school is situated in a village, we are no soft townies. At break times, our children engage in risky play (normal play in the 1980s and 90s) by climbing trees and walls, riding scooters, turning on the hose, doing cartwheels and playing in a mud and sandpit. Even when it rains heavily, we go out on the yard. We value fresh air and are not shrinking violets when it comes to supervising risk.

Today though, was on another level entirely.

I scanned the yard and play area. To my right, blows were about to be traded in a game of soccer over a free kick. I let them at it. On my left, half a dozen children were actually eating soil in the mud pit. ‘Hardly a ringing endorsement of our hot school meals,’ I thought. I graded it as one to watch.

At break times, our children engage in risky play (normal play in the 1980s and 90s) by climbing trees and walls, riding scooters, turning on the hose, doing cartwheels and playing in a mud and sandpit.

My biggest problem was in front of me. There, our most precious and sensitive junior infant was pinned on the ground by two others who were licking her arms and legs like a lollipop. ‘Oh no,’ I whimpered. ‘Not the Parental Biohazard Complaints Procedure again.’

Before breaking into a sprint, two older children appeared, accusing each other of being mean, bossing the game, and using the heinous word ‘stupid’. I thought of Michelle Stowe, emphasising the restoration of relationships through empathy and multi-perspectivity. There was no time for that today. I simply sided with the least guilty-looking child. The moon would have to wane before we had time for fluffy stuff.

It wasn’t just me. Everyone on duty was engaged with complaints, tantrums and allegations. Some pupils were crying and didn’t know why. A child asked me where the toilet was. He had been in the school for six years. Another told me his red Lamborghini had been stolen while he was fighting robots. I simply shook my head in sympathy, noted the details and said I’d get back to him.

Things were so bad that I wished that Covid-19 pods were back. The bell finally rang. Exhausted, we could only corral the children into a corner of the yard and count down the seconds until the class teachers saved us.

The break might have finished, but, as every leader knows, the real fun was just beginning. I still had to communicate the fallout with all class teachers and parents involved, resolve every lick, kick and muck dinner, and investigate the theft of an imaginary racing car. And, with the wind howling, we still had lunch break to go. They never teach the real hard stuff in college or on leadership courses, do they?

If you would like to get in touch with Paul in relation to this piece, he can be reached at donegalpaul@gmail.com

Everyone on duty was engaged with complaints, tantrums, and allegations. Some pupils were crying and didn’t know why. A child asked me where the toilet was. He had been in the school for six years. Another told me his red Lamborghini had been stolen while he was fighting robots. I simply shook my head in sympathy, noted the details and said I’d get back to him.

JACINTA BUDHLAEIR PRINCIPAL OF NANO NAGLE SCHOOL, LISTOWEL

In the summer of 2024, Nano Nagle School in Listowel embarked on an exciting and innovative journey, one that would go on to redefine what inclusion and community collaboration look like in special education. As part of the Department of Education’s Summer Programme Special School Scheme, we partnered with Munster Technological University (MTU), Tralee, to pilot a two-week programme for our students with moderate, severe and profound disabilities. This pilot programme was overseen by my predecessor Gabrielle Browne and the programme coordinator Jacqueline Halpin with the support of our school inspector Gerard Quirke and Ray McInerney as National Programme Coordinator.

This initiative was designed to offer students a unique learning experience in a third-level environment, an opportunity to learn, explore and engage beyond the traditional school setting. With the unwavering support of the Department, our dedicated staff, and the team at MTU, the pilot programme ran for two weeks in July 2024 and catered to 12 students.

From the outset, the programme was a resounding success. Students participated in a rich blend of activities, from creative arts and movement sessions to hydrotherapy and social skill development. Parents expressed immense satisfaction, teachers and SNAs saw students flourish in new settings, and the students themselves displayed enthusiasm and confidence as they adapted to life on a college campus.

Parents highlighted the boost in their children’s communication and independence skills, teachers noted increased confidence and, most importantly, the students spoke of their enjoyment and excitement being involved with the summer programme in MTU.

Following the summer programme, Gerard Quirke visited Nano Nagle School in the first term of the school year. He conducted interviews with students, parents, and staff to evaluate the pilot’s impact; what worked well, what could be improved, and what lessons might shape future iterations. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Parents highlighted the boost in their children’s communication and independence skills, teachers noted increased confidence and, most importantly, the students spoke of their enjoyment and excitement being involved with the summer programme in MTU. Additionally, the MTU staff remarked to me of the inspiring atmosphere and sense of fun and enjoyment the students brought to the campus and how proud the staff were to facilitate our students at MTU.

Based on the feedback gathered and further discussions with the Department, we were encouraged to expand the programme for summer 2025. In March, programme

coordinator Jacqueline Halpin and I met with Michael Hall from MTU Tralee to plan for this second phase. Together, we explored how best to accommodate a larger group of students while maintaining the high quality of the experience. With MTU’s continued enthusiasm, we agreed to increase the number of student places from 12 to 24. The school arranged to pay a nominal fee to cover MTU’s on-site costs, booked rooms across the campus, and secured access to the university’s hydrotherapy pool, all within the allocated summer programme funding.

To ensure safety and suitability, teachers across the school undertook comprehensive risk assessments for each student. Out of 96 enrolled students, 28 were identified as suitable participants who could thrive in the off-site summer programme environment.

To deliver the expanded programme, we assembled a dedicated team, one programme manager (Garrett Byrne), four teachers, and 14 Special Needs Assistants, supported by bus escorts on the various transport routes. We also assembled a sub-pool of teachers, SNAs and bus escorts for the two weeks. Students were drawn from seven of our 15 classes, representing a broad range of abilities and needs.

Behind the scenes, an enormous amount of logistical planning took place. Coordinating with the Department through ESINET, managing payroll systems, processing contracts for external teachers, and ensuring all required documentation was in place demanded substantial effort. We hired

specialists to deliver tailored sessions throughout the two-week period, including Zumba, PE, drumming and drama workshops, all of which encouraged creativity, movement and social interaction. We worked tirelessly with Bus Eireann to organise bus transport for the two-week period, which was not an easy task.

Equally important was our commitment to child safeguarding and compliance. Because the programme was held off-site at MTU, we revised our Child Safeguarding Statement to reflect the new context, appointed a Designated Liaison Person (DLP) and Deputy DLP for the duration, and conducted a thorough risk assessment of the entire operation. Permission slips and consent forms were issued to parents, and feedback templates were shared for future inspection and review.

The benefits of the collaboration have been remarkable. The students not only enjoyed a vibrant and structured summer experience but also developed confidence, communication and independence in a communitybased learning environment. Being welcomed into a third-level setting provided them with a tangible sense

of inclusion, a feeling that education, in all its forms, belongs to them too.