THE PROFESSIONAL VOICE OF SCHOOL LEADERS

STARTING as we mean to go on STARTING

STARTING as we mean to go on STARTING

McCabes Pharmacy are delighted to once again offer our on-site Flu vaccination service to primary schools this Autumn/Winter 2025.

Why choose McCabes Pharmacy?

Nationwide On-Site Flu Vaccination for Students & Staff

We bring our school vaccination clinics directly to you eliminating the need to travel and minimising disruption to the school day.

Our qualified pharmacists are highly trained and have years of experience in delivering school vaccination programmes across the country.

Easy, GDPR-Compliant Consent Process

Consent is managed securely via our digital platform.

To register your school’s interest, simply scan the QR code and complete the online form at at mccabespharmacy.com

Or Email services@mccabespharmacy.ie

ISSUE 139 | OCTOBER 2025

Carmel Lillis Coach, Former Primary Principal, Educational Researcher

Universal Design for Learning – an intervention framework to support inclusion?

John Brennan Principal of St. Fiacc’s NS, Graiguecullen, Carlow

Supporting, including and empowering SNAs

The Role of the Primary School Deputy Principal 4 15 20 12

Bliain ag Fás Dúinn Beirt In the Eye of the Storm: Leadership

Colmán Ó Drisceoil

Scoil Lorcáin, An Charraig Dhubh, Co. Bhaile Átha Cliath

Fiona Wickham Principal of St. Senan’s PS, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford

Magdalena Landziak SNA and Trainer

Summer Programme in Special Schools

Ray McInerney Programme Coordinator

Small Schools Project: Donegal Cluster: Ballymore NS, Creeslough NS, Holy Trinity NS, Killygordon NS

- Finbarr Hurley, Oide Primary Leadership Coordinator and Donegal Cluster Coordinator

Resource Pack for Primary School Leaders on Bereavement, Tragedy and Trauma

- Louise Tobin, IPPN President 2023-2025

A Tribute to Emer Byrden 1971-2025: Deputy Principal of Carlow Educate Together

- Simon Lewis, Principal of Carlow ETNS

Building on Céim: Supporting Newly Qualified Teachers to Engage in the Droichead Process

- Myriam Gately, Primary Senior Leader, Oide Droichead Induction Division

Legal Diary: Behaviours of Concern – Emerging Issues for Schools - David Ruddy BL

Lessons From The Badger: A Seminar For The Ages - Paul O’Donnell, Principal of St Patrick’s NS, Slane, Co. Meath

Homework That Speaks Every Language: Supporting Multilingual Learners at Home

- Dr Chelsea Whittaker, Assistant Professor, School of Education, Trinity College Dublin And much more…

Irish Primary Principals’ Network, Glounthaune, Co. Cork 1800 21 22 23 • www.ippn.ie

Editor: Geraldine D’Arcy

Editorial Team: Geraldine D’Arcy, Brian O’Doherty and Deirdre Kelly

Comments to: editor@ippn.ie n Advertising: Sinead O’Mahony adverts@ippn.ie ISSN: 1649-5888 n Design: Brosna Press

The opinions expressed in Leadership+ do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of IPPN

SIMON LEWIS PRINCIPAL OF CARLOW ETNS

The entire community of Carlow Educate Together are heartbroken after Emer Byrden, our much-loved Deputy Principal and friend, passed away after a very short illness in July 2025, less than a fortnight after finishing her 15th year in our school.

I’ve always thought I was the luckiest principal in the world because I got to meet one of my best friends every day that I went to work. From the minute Emer walked in for her interview in our fledgling school in 2010, we knew we had found someone special. Emer became Deputy Principal of our school a few years later, where we spent every day together trying our best to put the world to rights.

Emer was the most caring, understanding and supportive person I have ever worked with. She had a wicked sense of humour, and we laughed a lot in the refuge that was my office. She was my voice of reason. She was my ChatGPT before ChatGPT existed, checking over all the contentious emails, and offering ways to soften bad news gently.

Emer was also a mentor to me. She and I shared the same values, both in education and in life. When my wife and I had our baby, she was always there to reassure me that my consistent efforts to ruin his life were completely normal. My favourite advice from her was when she recounted her own parenting efforts: ‘You bring up your children to think for themselves, and then - damn itthey go and think for themselves.’ We laughed a lot.

Central to Emer’s philosophy was relationships. How people interact with each other was of such importance to her that she began her Ph.D in Relational Awareness in Maynooth University, where within a year she was already being hailed as one of Ireland’s most important voices in her field. She was about to embark on a career

break to focus on this research, complete her academic work, and – I say this without exaggeration – change the world. It feels like a terrible injustice that she did not get to complete it.

Emer had many loves – her family, her reading and her sea swimming. As a staff, while we remained helpless in knowing what to do, we took to the coast in August and waded our way into the waters to remember her. Emer will always be loved by all of us in Carlow Educate Together and we send our deepest sympathies to her husband Seán, her two boys Colm and Finbarr, and their extended family and friends.

simon@carloweducatetogether.ie

As the new school year unfolds, IPPN shares the fruits of our labours in launching an enhanced suite of supports and services, which Brian details in Supporting Your Leadership Practice on page 8. This includes the new website, an IPPN podcast, a specially commissioned digital resource on burnout prevention, as well as a reimagined Stepping into Leadership programme (formerly Headstart) for all new principals and deputy principals.

New IPPN president, Deirdre Kelly, sets out her stall in her article on page 10. In this issue, we also look at resources on tragedy in schools, behaviours of concern, the summer programme in special schools, working effectively with SNAs, and explore how the Donegal Cluster in the Small Schools project is progressing, what Universal Design for Learning is all about, what’s new in Droichead, the findings of research on the role of the deputy principal, how we can support multilingual learners, and much more.

IPPN has started the new school year as we mean to go on, with a new strategic plan to be launched in November, and work progressing on a new guide to the leadership of inclusion, bringing together a wealth of information and guidance on this significant aspect of leaders’ work in schools. This is to name just two pieces of work from across the team that are currently underway.

The Leadership Support Service and the wider team continue to respond to school leaders who find themselves in challenging situations, or who simply wish to talk through an issue in school. Our events team is working out the details of seminars, plenary sessions, Expo and all the other elements that make our annual conferences such a success. Staff who are focused on delivering our online services are working to ensure that everything runs smoothly and that enhancements are planned and implemented. Not to mention E-scéal, publications, research and other important member-related work.

IPPN’s advocacy work continues apace, including following up our Budget 2026 submission priorities, where IPPN called for:

• time for school leaders to lead teaching and learning

• adequate resourcing of Special Education Needs Provision

• enhanced supports for children experiencing disadvantage, and

• increased grant funding.

We thank everyone who has contributed to this issue, particularly the school leaders who have shared their practice, insights and research. As always, your feedback on Leadership+ and any other aspects of IPPN’s work, is appreciated and you can contact the editorial team by email to editor@ippn.ie

Geraldine D’Arcy Deirdre Kelly Brian O’Doherty Editor President Deputy CEO

JOHN BRENNAN PRINCIPAL OF ST. FIACC’S NS, GRAIGUECULLEN, CARLOW

How should we accommodate the needs of the children in our classrooms? How do we remove barriers to learning? What are the most effective interventions to allow learning for all?

Are you familiar with Universal Design for Learning (UDL)? There has been an emerging interest in UDL and its potential benefits in supporting inclusive practices, as referenced in NCSE Relate and Understanding Behaviours of Concern and Responding to Crisis Situations

The concept of Universal Design for Learning was considered by the Centre for Special Applied Technologies (CAST) in the 1980s as a means to create an education for everybody.

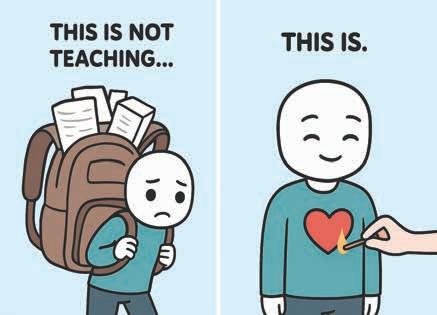

Universal Design has its origins in architecture from the 1980s; buildings were designed with physical access in mind. The concept of Universal Design for Learning was considered by the Centre for Special Applied Technologies (CAST) in the 1980s as a means to create an education for everybody. Drawing from neuroscience, a UDL approach supports the three interconnected neural networks of the brain, supporting recognition learning (the ‘what’), strategic learning (the ‘how’) and affective learning (the ‘why’). By providing multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation and multiple means of action or expression, UDL maximises learning opportunities for all students (Figure 1). The three principles are subdivided into nine guidelines, each of which has more detailed suggestions on how to apply them.

A plus one approach might be a starting point to UDL in your school. Is there one additional way I could engage my pupils? One additional way I could represent information, or that I could allow for action or expression of learning? Every day in many classrooms, teachers are embracing UDL methodologies by another name. Do you take pupils’ interests and suggestions into account before you begin teaching fractions? Do you offer choice to pupils on how the learning goals are reached? Are pupil interests, strengths and needs factored into lesson design? Are goals broken down into more explicit subgoals? These are all examples of engagement –designing learning experiences that pupils can connect with.

When you present a lesson, do you use visuals and concrete materials alongside words? Is there scope for text to speech software for some pupils? Do you make accommodations

Multiple Means of Engagement

Stimulate motivation and sustained enthusiasm for learning by promoting various ways of engaging with material.

Multiple Means of Representation

Present information and content in a variety of ways to support understanding by students with different learning styles/abilities.

Multiple Means of Action/Expression

Offer options for students to demonstrate their learning in various ways (e.g. allow choice of assessment type).

Do you take pupils’ interests and suggestions into account before you begin teaching fractions? Do you offer choice to pupils on how the learning goals are reached? Are pupil interests, strengths and needs factored into lesson design? Are goals broken down into more explicit subgoals?

for the child who has difficulty taking notes? Do you offer partner reading? These are examples of representation, which may be the best starting point for a teacher engaging in UDL, as this principle has a focus on teacher choice; engagement and assessment have more of a focus on student voice and agency.

flexibility in how learning is expressed or demonstrated? An oral presentation or a pictorial representation of learning can accommodate different learning styles. There are many options for multiple means of demonstration or expression of learning outside of the traditional pencil and paper format – providing checklists or templates to scaffold learning, creating opportunities for self-monitoring of progress through portfolios, before and after photographs, and use of multiple-media to express learning are some examples. Offering choice and flexibility personalises assessment - it is more inclusive than the traditional ‘one size fits all’ approach. ‘Plus One’ provides a simple starting point in utilising UDL principles without overwhelming teachers.

UDL and the Curriculum

The argument for a whole-school UDL approach to accommodate the needs of all pupils, in particular pupils with autism, is compelling. With the conversation, in the Irish context,

model of education, this is a timely opportunity to consider UDL as a framework to accommodate learner variability in classrooms. As the curriculum is outcome-focused rather than content objective-focused, the phasing in of the language and maths curricula and the redeveloped primary school curriculum are opportunities to introduce UDL. The revised curriculum allows teachers to adapt their instruction to the specific interests, needs and abilities of the children in their class – meeting children where they’re at developmentally –which is UDL and nurture combined. The primary curriculum framework values equity of opportunity and children’s agency to make choices about their learning. UDL might be worth exploring as schools begin to implement and embed aspects of the redeveloped curriculum.

If you would like to contact John in relation to this piece, you can send an email to mrbrennan@stfiaccs.com

Offering choice and flexibility personalises assessment - it is more inclusive than the traditional ‘one size fits all’ approach. ‘Plus One’ provides a simple starting point in utilising UDL principles without overwhelming teachers.

DAVID RUDDY BL

The DEY published the much-awaited guidance, ‘Understanding Behaviours of Concern and Responding to Crisis Situations’ at the end of 2024. This guidance is welcome and contains helpful contents to include a multi-tiered support response to behaviours, along with an examination of crisis situations. The guidelines acknowledge staff uncertainty on how to respond when facing a crisis situation where there are concerns regarding physical safety. The guidelines support the principle that all staff must take reasonable steps to ensure the safety of all students under their care at all times. The challenge for schools is balancing the rights of the student exhibiting the dangerous behaviour with the safety of other students and staff.

Physical restraint is defined as ‘Any procedure where one or more adults restrict a student’s physical movement or normal access to his or her own body. It is an intervention used in crisis situations when not to do so could result in serious physical harm or injury to the student or others’. Examples of crisis situations where there is an imminent risk to the student’s safety or to that of others include:

1 A student puts themselves in danger e.g. running into a road or towards explicit danger.

2 A student self-injures by banging his/ her head with force on a hard surface.

3 A student throws large items, such as computers or furniture, at peers or adults.

4 A student physically attacks another person.

Physical restraint should be timely, measured, appropriate, carried out if at all possible by appropriately-trained persons, and reviewed after the event. Staff are advised not to intervene alone if they are at risk of serious injury or are unable to apply intervention techniques.

Where a physical restraint has been used, the incident must be reported to the school principal and, subsequently, to the Board of

The challenge for schools is balancing the rights of the student exhibiting the dangerous behaviour with the safety of other students and staff.

Management/ETB. From September 2025, schools are also required to report to the NCSE. The purpose of reporting to NCSE is to allow for the collation of quarterly reports on the extent of the practice being deployed in schools. NCSE has no role in investigating the deployment of a physical restraint in schools. Reporting templates are provided in the ‘Resources’ section of the Guidelines.

Seclusion is defined as ‘placing a student involuntary in any environment in which they are alone and physically prevented from leaving.’ Blanket restrictions are not regarded as seclusion. The guidelines state ‘that seclusion should not be used under any circumstances in any school setting’ Examples of seclusion highlighted include physical prevention from leaving through the use of a locked door, a blocked door or an exit held closed by a staff member. Fire safety regulations would also support such an approach. Where a student has a weapon or is about to inflict violence on another student or member of staff, and the only possible avenue to protect health and safety is to hold said student until support staff/parents/An Garda arrives is by means of a locked door, a blocked door or an exit, what is the position? This scenario clearly would be contrary to the guidance. However, the guidelines say should rather than shall Is this a recognition that there may be exceptional crisis circumstances where isolation pending the support alluded to above is permissible to preserve health and safety? Alternatively, the use of the words should rather than shall may reflect that we are dealing with guidelines rather than procedures.

There is no legislation, national guidance, or policy in Ireland on the use of restraint or seclusion of students in schools. In crisis situations, schools have a duty of care to safeguard both students and staff from harm. School staff are ‘in loco parentis’ and are required to discharge a duty of care akin to that of what a ‘reasonably careful parent’ would do. The Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 and the school safety statement states that “Employees have a right to a safe working environment as far as is practical”. Equally, the code of behaviour (underpinned by the Education Welfare Act 2000) is a policy to deal with situations where students exhibit behaviours that constitute a health and safety risk.

The Children First Act 2025 places a statutory obligation on schools to keep students safe from harm. Tusla appears to have no child protection concerns if restraint is used in circumstances where there is an imminent risk to health and safety, if the guidelines are adhered to, and for as short a time as possible. However, some parents and advocacy groups do not agree.

The guidelines, whilst welcome, need to be road tested. Unlike procedures, guidelines are recommendations rather than being mandatory. They allow for flexibility and judgement, whilst procedures are to be followed exactly as written e.g. The Child Protection Procedures for Schools. National Guidance for Child Protection was published in 2011. The Children First Act in 2015 then was followed by Child Protection Procedures in 2017 which were updated in 2023 and again in 2025. It is likely that Behaviours of Concern will follow a similar pathway. Schools are advised to formulate a policy on Behaviours of Concern and embark on training for staff. This will empower staff to approach crisis scenarios with greater confidence.

If you would like to get in touch with David in relation to this article you can contact him at david.ruddybl@gmail.com

Make your budget go further with our flexible low cost payment options designed for schools.

iPad A16 128GB devices

Wheeled charge & storage trolley

Rugged Protective Cover

Device Management Licence with FREE Training!

Bespoke Device Configuration

Secure delivery to your school

Scan QR Code to Get a Quick Quote or visit bit.ly/WriggleGetaQuote

BRIAN O’DOHERTY IPPN DEPUTY CEO

Earlier this year, I shared with you details of the review of the suite of supports and services that IPPN offers to members. On foot of that review, the issues that members raised with us and the suggestions that were made, we undertook to reimagine, or to develop, particular services to support your leadership practice. Much of that work has now been completed and I am happy to share with you the fruits of our labours.

A significant focus of this work and a key priority for IPPN was the development of a new website. The E-Services committee of the National Council shaped the work on this project which was undertaken by staff in the Support Office and the new website went live on the 26th of August, just in time for the new school year. We are confident that you will find it straightforward to navigate, and

more importantly much easier to find what you are looking for.

To that end, we have re-organised the Sample Policies section into just two categories – mandatory and other –and we have stripped out the multiple versions and those policies that were past their sell-by date. In the Resources section, we have re-organised them into the four domains of the Quality Framework, with sub-folders in each for ease of access. All policies and resources on the website have been shared by fellow school leaders. If you have a policy or resource that either isn’t on the website or that is better than the one that is on the website, please share it with us and your colleagues by emailing it to info@ ippn.ie. It’s that professional generosity that benefits all in the network.

Speaking of professional generosity, we have created a new section on the website called Leaders Supporting

Leaders. It has three elements in it, two of which you will be familiar with –networking and group mentoring. The new element is Members’ Tips, where we are inviting you to share with us your experience of leading, managing or implementing a particular initiative or scheme in your school – an opportunity to share your top tips or your do’s and don’ts. All you have to do is to record a short audio or video clip and email it to us at info@ippn. ie. We’ll share these Tips via links on the website and build up a repository of expertise that you can listen to or view, whenever you choose to.

Stepping into Leadership

What used to be our Headstart programme has now become our Stepping into Leadership programme. It is designed to be a two-year bespoke programme of support for all newlyappointed school leaders, as well as those stepping into a leadership role

on a temporary basis. Those availing of the support will receive fortnightly emails with relevant planning prompts and leadership reflections throughout this induction phase of their leadership journey. These reflections and a full year’s planning prompts are available via the designated Stepping into Leadership section of the website. Also available in this section are links to relevant documents and information from all the key agencies and bodies.

One of the key learnings from the Sustainable Leadership project has been the negative impact leadership practice can have on the health and wellbeing of school leaders. It is what prompted the Advocacy &

Communications committee of the National Council to develop a position paper on school leader wellbeing and out of which emerged our Be Well, Lead Well campaign. The underlying premise is that you cannot possibly lead effectively if you are not well enough to do so.

As part of the campaign and to further promote your wellness, IPPN commissioned a psychotherapist to develop a digital series exclusively for IPPN members. The series –entitled Be Well, Lead Well: Burnout Prevention – will consist of 10 bitesized videos which can accessed and digested at your own pace, whenever it suits you to engage. The emphasis is on prevention by recognising the signs and symptoms of stress and burnout, with practical tips and downloadable resources. The series will be available to members from mid-October.

Another of the Advocacy and Communications committee’s suggestions was that IPPN would dip its toe into the world of podcasting in the context of trialling different ways of communicating

We invite you to register for the wonderful world of eTwinning – an innovative online platform connecting a community of teachers and their students across Europe.

Using ICT, eTwinning supports schools to partner with other countries and work on creative digital projects in any curricular area. You can build on projects or initiatives your students are already working on in class, discover and join what schools in other countries are working on or use one of our project kits to build an MFL or Bí Cineálta project.

with you to highlight the importance of school leadership. Accordingly, the new IPPN podcast – Leading for Impact will be coming your way at the beginning of October with episodes available on 25+ podcast platforms.

The series will include voices from within and outside education, exploring the experience of the practice of primary school leadership, the challenges that arise and the opportunities that present. If you have ideas or suggestions for the podcast, you can send them to advocacy@ippn.ie

We will keep you informed of all further developments to our supports and services through the usual channels, and we welcome your ongoing feedback to assist us in better meeting your needs as school leaders.

brian.odoherty@ippn.ie

Joining and participating in the eTwinning community is a unique and hands-on way to help your students engage in:

• Cross-curricular learning

• Digital literacy

• Multicultural communication

• Language exchange opportunities

• Global citizenship

Contact Léargas to find out more etwinning@leargas.ie | www.leargas.ie/etwinning school-education.ec.europa.eu/en/etwinning

Scan the QR Code to Learn More

DEIRDRE KELLY IPPN PRESIDENT 2025–2027

After 19 wonderful years as a teaching principal in St Michael’s National School, a four-teacher rural school in Cloonacool, Co. Sligo, I find myself at an exciting new crossroads. I’m stepping into a role that allows me to advocate for and support school leaders from all school contexts. It is a big change, but I carry with me deep gratitude for the people and experiences that have shaped my journey so far.

Being a school leader is far more than just a job. It’s a way of life. It means wearing many hats: teacher, leader, mentor, listener and community connector. The role is demanding but incredibly fulfilling. I’ve loved the daily rhythm of school life – the learning, the laughter and those quiet moments when you realise you’ve truly made a difference. Admittedly, I only fully appreciated this recently.

Leading a small, rural school means juggling many roles all at once. Of

To the children I’ve taught and laughed with, you have been my greatest teachers. To the families and staff I’ve worked alongside, thank you for trusting me and walking alongside me

I come to the IPPN President role with sleeves rolled up and heart wide open, ready to listen, advocate, and make sure your voices are heard.

course, there were tough days, but the closeness and community in rural schools soften those challenges. To the children I’ve taught and laughed with, you have been my greatest teachers. To the families and staff I’ve worked alongside, thank you for trusting me and walking alongside me.

Throughout my career, I’ve taught in classrooms, helped nurture young minds and supported families through both challenges and celebrations. Some days were long, and the juggling act sometimes felt endless. Now, as I take on this new role advocating for school leaders, I bring all these experiences with me. I know firsthand the pressures and the joys, the fatigue and the fulfilment, of leading a school while also managing the day-to-day realities of teaching.

This role gives me the privilege to be a voice for school leaders – to shine a light on the incredible work you do, the challenges you face, and the support you need to thrive. While I may no longer be greeting children

at the school gate each morning, I will continue to stand beside those who do.

I’ll always be a principal at heart – an identity woven deep into who I am. I step into this role with humility, purpose and a deep respect for every educator doing this important work. I look forward to the journey ahead and to continuing to serve those who serve our children every day.

Today’s leadership involves far more than running a school. It’s about navigating systems, advocating for resources and supporting a team through constantly changing educational and social landscapes. Yet, despite all the change, one thing remains constant: the children. Their joy, growth, resilience and curiosity are why we do this work—they are the heart of our schools.

I come to the IPPN President role with sleeves rolled up and heart wide open, ready to listen, advocate, and make sure your voices are heard.

I am committed to working with school leaders and advocating on your behalf to ensure that leadership is not only supported but truly sustainable –so that we can focus on what matters most: leading teaching and learning.

Deirdre.Kelly@ippn.ie

Deirdre qualified as a primary teacher from Froebel College, Blackrock, Dublin and then completed a Postgraduate Diploma in Trinity College Dublin. Her early career included many years teaching in a special education setting – an experience that inspired her to pursue a master’s degree in educational leadership.

Over the years, Deirdre has taught in a wide range of educational settings, both urban and rural, gaining a deep understanding of the diverse challenges and opportunities within the Irish primary education system. In 2004, she was appointed Teaching Principal of St Michael’s NS.

Deirdre is a longstanding and active member of IPPN. She represented Sligo for many years

at National Council, has served on the Board of Directors, and cochairs the Professional Development Committee on National Council. She is a trained mentor and has facilitated group mentoring to support school leaders across the country.

Her strong advocacy for small schools, her belief in their vital role in rural communities, and her commitment to supporting school leaders, are central to Deirdre’s work. These values underpin her contribution as a member of the IPPN Board of Directors.

Deirdre was elected IPPN Presidentelect in June 2023 and commenced her two-year term as IPPN President in September 2025.

Introduction

CARMEL LILLIS COACH, FORMER PRIMARY PRINCIPAL, EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER

The research team set out to explore how the position of deputy principal is perceived and enacted in Irish primary and post-primary schools, through the perspectives of deputies themselves. The work evolved from our individual experiences of teaching on various leadership courses in universities and facilitating support groups for deputies in diverse settings. We undertook formal research with deputies from primary and post-primary schools. In this instance we report on findings from our research within the primary sector: we gathered data from 49 questionnaire responses and held in-depth interviews with five deputies. The questionnaire sought to ascertain from deputies the main features, strengths, satisfaction and challenges in the role.

Findings

In our analysis of the data collected, we have established that the role of the deputy principal is both critical and evolving. The deputy is asked to fill many practical tasks in a school while at the same time being a vital link between senior leadership and staff. While much has been written in recent years, in Ireland and internationally, about shared/ collaborative/ distributed leadership within schools the role of the deputy within this structure is largely underdeveloped.

Our research emphasises how every school is unique. It is important to recognise the context and culture of each of the 3,300 primary schools in Ireland. No two schools have the same history, stories, or heroes/heroines. When led positively, each school will adopt and adapt to changing circumstances. Today’s world calls for shared responsibilities within each school. A positive outcome for

all students is the goal for everyone involved. Strong relationships based on a shared vision for the school are critically important. None is more important than that between principal and deputy.

In this article we reflect again on the lived experiences of deputies in order to clarify and support this vital role. We offer some possibilities, as presented by the deputies involved in the research, of support that can be given so that the vital role of deputy is acknowledged within the system.

“It’s only as you go through the job, you realise there’s more expected of you. There’s more than was traditionally associated with the role.”

Oliver, Deputy Principal, Primary, interview

The evidence suggests that an overview of how deputy principals see their work can be represented by three categories of activity: logistical maintenance; behavioural and pastoral support; curricular innovation and development. Importantly, participants in the research wish to emphasise that ‘how’ they perform these duties are also key to understanding the role. In particular, they highlight nurturing relationships and teamwork. This composite perspective can be represented as in Figure 2.

Deputies are asked to undertake a variety of tasks in schools, from coleading the organisation to organising

the Christmas Fair… And a full-time teacher!!!!!! (80P). There are long lists of duties and responsibilities submitted by respondents to the questionnaire. Deputies wrote about being in school early and about bringing their administrative work home. The dual role of deputy and class teacher is replete with constraints and tensions. Síle, a deputy in a large rural school, summed up the tension emerging from this situation:

“...feel if I could sum up my job in two words, it would be ‘unfinished conversations’”, then posing the question “and what can unfinished conversations achieve?” As she sees it, “Because you’re always on the hoof; you always have to be somewhere else, and you’re always trying to catch that thread about that conversation... of that initiative, I feel it impacts on my ability to mentor the younger teachers because I can never be fully present to them”. She expresses the view that “not having some level of administrative support for deputy principals – certainly in big schools – is counterproductive.”

Overall, responsibility for ensuring the smooth day-to-day operations of the school is regarded as key to a deputy’s work.

Beyond logistical maintenance, primary school deputies also see dealing with children’s behaviour and offering pastoral support to them and their parents as central. This is especially evident in the case of students with additional educational needs. Primary school deputies, in particular, tend to frame their relationships with children as in ‘loco parentis’, expressing strong commitment to values of care and nurturance. More broadly, respondents

highlighted the role of collegial relationships in fostering dynamic, positive cultures. There is an alignment between the strengths of the role and the satisfaction deputies derive from fulfilling their responsibilities:

‘When you see progress, and progress for me is that needs are identified and you can put something in place that helps to either alleviate, to address or to improve those needs. In the media there’s an awful lot of reporting of the justifiable anger in the system towards external services and waiting lists and so on. When you feel that you’ve helped a pupil and therefore a family along the road towards getting to a better place it’s very, very satisfying. This is wider than SEN.’ (Aaron at interview).

Curriculum development and innovation are dependent on strong relationships among staff, and especially between principal and deputy.

For some deputies, frustration arises when a commitment to support curriculum development and innovation – seen as an essential feature of the role - is superseded by the immediacy and

urgency of other tasks. This in turn can hinder the nurturing of relationships and teamwork which many see as contributing to the professional and personal development of deputies and the flourishing of children in school. Traditionally teaching has often been practiced as an individual pursuit. Our modern understanding puts much more emphasis on schools as places of collaborative practice. A deputy speaks about the way the role: ‘...has invigorated and reenergised my practice. It is my wish to lead and develop teaching and learning within my school… I enjoy leading projects, delegating to and motivating colleagues, pupils and parents.’. (8P).

‘Building professional relationships and developing leadership capacity among my colleagues is particularly satisfying.’ (57P).

While the report details the view of deputies, it also offers pointers to how practice might be improved.

• Regular dialogue, including formal, scheduled meetings between principal and deputy should become normal in every school

• Deputies need adequate time to perform administrative tasks. Some

recount how officially granted administrative time during the Covid-19 crisis opened their eyes to new possibilities

• Individual schools – in addition to the system generally – could do much to give greater visibility to a role that is crucial in the development and flourishing of the school and its students

• Before and following appointment as a deputy principal, professional development opportunities should address practical, immediate concerns as well as enriching understanding of meaningful education for children. How to be a good team member and how to lead a team are critical skills that might be developed

• Support groups where deputies can converse openly with other deputies are valued and could be facilitated and promoted.

LINK Full report available here.

Carmel works with leadership programmes at Maynooth University and at the University of Limerick and facilitates professional development courses in Education Centres for teachers and Special Needs Assistants.

If you would like to get in touch with Carmel Lillis in relation to this article, you can send an email to Carmel.Lillis@mu.ie

“You have a key position between home and school and parents and the parish. You actually are in a privileged position in terms of the amount of people that you meet through the school community and the relationships that you build and that you develop.” Ruth, Deputy Principal, Primary, interview

Primary School Teacher feedback

MAGDALENA LANDZIAK SNA AND TRAINER

In every inclusive school, the strength of the team lies not only in its vision but in how that vision is lived out, day to day. Principals play a crucial role in shaping the tone, values and direction of a school. From the perspective of a Special Needs Assistant (SNA), one of the most impactful aspects of leadership is how SNAs are supported, included and empowered.

The work of an SNA extends far beyond the official circulars. While our duties are clearly outlined by the Department of Education, our day-to-day practice is rich with nuance. We support emotional regulation, facilitate communication, adapt the environment and build trust with children who often face additional challenges.

Taking time to understand the depth of this role – and the passion behind it – strengthens mutual respect and enriches the school’s inclusive culture.

A reflective leader might ask: Do I fully understand what my SNAs do each day? Have I invited them to share their experiences, challenges or insights?

Inclusion begins at the Staffroom Door

Inclusion is not just something we deliver to students – it’s something we model as staff. Feeling a sense of belonging is essential for everyone in a school, including SNAs. When SNAs are included in team meetings, CPD opportunities, planning discussions, and informal staff events, it sends a powerful message: you are a valued member of the team

This inclusion may happen naturally or require intentional action. Either way, the outcome is a more connected staff – and better support for students.

A reflective leader might ask: Are my SNAs fully included in the professional and social life of this school?

Inclusive leadership values the voice of all team members. This can be reinforced through well-defined roles, structured systems, and genuine dialogue. It means asking, ‘What do you think?’ and truly listening to the response.

One of the most powerful things a principal can do is believe in the potential of their team. Many SNAs are eager to deepen their knowledge and develop their skills. When access to professional development is supported and celebrated, we feel seen and empowered. We also become better equipped to support our students – whether in areas such as sensory needs, emotional regulation or assistive technology.

A reflective leader might ask: Am I actively supporting the professional development of my SNAs – with time, funding and encouragement?

Clear, open communication is the glue that holds school teams together. SNAs often spend the most one-toone time with students. It can be disheartening to hear about policy changes second-hand, or to find out that key decisions were made without consultation.

Inclusive leadership values the voice of all team members. This can be reinforced through well-defined roles, structured systems and genuine dialogue. It means asking, ‘What do you think?’ and truly listening to the response. It also means creating a

culture where SNAs feel safe to speak up – not only about students, but about their own wellbeing.

A reflective leader might ask: Do my SNAs feel heard, respected and included in decision-making?

Leadership is influence. The way SNAs are spoken to, spoken about and included, sets the tone for the entire school community – students, staff and parents alike. When principals model inclusion, respect and appreciation, it fosters a culture where everyone is valued.

This has a ripple effect. Respected SNAs are more empowered in their roles. Students observing kind collaboration are more likely to emulate it. A school that nurtures all staff becomes an environment where everyone can thrive.

A reflective leader might ask: Am I modelling the respect, professionalism and inclusion I want to see in my school?

SNAs are committed to helping students access their education, regulate their emotions and feel a sense of belonging. With the right leadership support, we can do even more.

Principals have a unique opportunity to create a school culture where SNAs are not only included but empowered. When that happens, everyone benefits –the staff, the students and the inclusive spirit at the heart of the school. Let’s lead together.

You can contact Magdalena by email at magdalandziak@gmail.com, on LinkedIn via her full name, on Instagram @sna_zone and via her website www.amygdala.ie

BERNIE MCNALLY SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION & YOUTH

‘In ongoing engagement with the Department, the IPPN provides valuable insight into the challenges facing school leadership and the lived experience in Irish primary schools today. The IPPN’s work in this area, encapsulated in its sustainable leadership strategy, helps to provide a focus towards enhancing leadership capacity, effectiveness and sustainability. The Department’s Statement of Strategy sets out our strategic objectives and prioritises working together with our partners, providing strategic leadership and support for the delivery of the right systems and infrastructure for the sector. This priority and Programme for Government commitments will see the Department looking more widely at school leadership and governance, both at primary and post primary level, to better support all school leaders and school communities.’

JOHN BOYLE GENERAL SECRETARY OF THE INTO

‘The INTO has always been a strong advocate for improved terms and conditions for principals and deputy principals of Irish primary and special schools, and therefore our organisation has, over the last 25 years, found much common cause with the IPPN. Since the establishment of the Primary Education Forum in 2018 our two organisations have collaborated in a combined effort to influence the planning and sequencing of change in our sector, so that the implementation of various initiatives is streamlined. We also highlight the impact of these initiatives on workload for school leaders and their teaching colleagues and seek additional supports to help embed educational reform.’

SEAMUS MULCONRY

SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE CPSMA

‘Principals and Deputy Principals with the support of Boards of Management and Patrons have shown enthusiasm, courage and flexibility in delivering policy change to help deliver better learning outcomes and experiences for our children. IPPN has played a vital role in this process and have developed critical services and supports for principals, deputy principals and schools such as the Education Posts website which is an invaluable resource for schools. IPPN has also been a forceful (and thoughtful) advocate for both its members and primary education.’

YVONNE KEATING CHIEF INSPECTOR

‘Since its formal establishment twenty-five years ago, IPPN has played a pivotal role in shaping and supporting primary education in Ireland and brings valuable insight and leadership experience to the national education conversation. The IPPN has made significant strategic contributions to the work of the Department of Education and Youth and the Inspectorate over the years. These include its participation on national committees, policy working groups and curriculum development boards; and through membership of groups to address inclusion, special education, disadvantage and wellbeing. The Inspectorate values the pivotal role that the IPPN plays in supporting the development of school communities, where effective leadership and a commitment to children’s wellbeing and learning are at the heart of practice. We acknowledge the careful and constructive feedback that IPPN has provided, over many years, in response to the Inspectorate’s proposals for updated quality frameworks, revised inspection models and approaches, development of advisory visits to schools and new formats for reporting.’

All statements will be included in full in the 25 Years of IPPN Epublication ‘Looking Back, Looking Forward’, which will be launched at the principals’ conference in November.

Ceapadh mé mar phríomhoide ar Scoil Lorcáin – Gaelscoil/ scoil lán-Ghaelach ar an 2 Feabhra 1999, agus Bertie Ahern ina thaoiseach. Bunaíodh an IPPN an bhliain dar gcionn – 25 bliain ag fás dúinn beirt. Níor cuireadh fáilte uilíoch roimh an IPPN ná romham.

Ní raibh puinn tacaíochta ar fáil do phríomhoidí nuacheapaithe go dtí sin. Chabhraigh Cathaoireach na scoile go mór liom, agus bhí sé d’ádh orm gur chláraíos leis an IPPN ón tús. Bealtaine ina dhiaidh sin agus an teocht íseal go leor go fóill sa scoil, tháinig an t-am chun na múinteoirí a eagrú ina ranganna don bhliain ina dhiaidh sin. Cothrom an ama, tháinig teimpléad ón IPPN don ghnó seo, deis ag múinteoirí Rogha 1, 2,3 a chur in iúl agus struchtúr don aineolach seo tabhairt faoin dúshlán. Bád tarrthála ab ea an teimpléad sin domsa. Thosaigh an aimsir ag feabhsú ón am sin i leith. Réabhlóid ab ea an teimpléad sin in an-chuid scoileanna, déarfainn. Réabhlóid ab ea an IPPN.

Tháinig go leor comhairle ón IPPN maidir le haire a thabhairt do do shláinte féin, agus moltaí praiticiúla ar thugas neamhaird orthu, cuid mhaith, ach go ndeachaigh an bunteachaireacht i bhfeidhm orm, ainneoin mo dhícheall – is gá duit aire a thabhairt duit féin, ar mhaithe leat féin agus ar mhaithe le gach duine eile a mbíonn tú ag déileáil leo. Tá turas tugtha ag an íomhá atá agam díom féin ó laoch/ceannaire/ Cúchulainn (ní deirim go raibh an íomhá seo cruinn) go háisitheoir/ réiteoir/ glantóir. Gné den chomhairle a bhí ann ón tús ná an deighilt idir dualgaisí an Phríomhoide – cúrsaí oideachais –agus dualgaisí an Bhord Bainistíochta – gach gné eile den scoil – agus an

...is gá duit aire a thabhairt duit féin, ar mhaithe leat féin agus ar mhaithe le gach duine eile a mbíonn tú ag déileáil leo.

riachtanas go nglacfadh gach ball den Bhord Bainistíochta le freagracht éigin lasmuigh de thinreamh ar chruinnithe boird. Chabhraigh an chomhairle seo go mór liom. Ghlac baill na mbord éagsúil leis go sásta, fonn orthu, ar an iomlán, tacaíocht a thabhairt.

Tá tírdhreach an oideachais tar éis athrú le 25 bliana, agus is gá forbairt a dhéanamh ar fheidhmiú na mBord, go háirithe –sílim féin - i dtaca le cúrsaí airgeadais. Ní ceart a bheith ag súil go nglacfadh duine gan oiliúint cheart na dualgaisí sin orthu féin. Is trua nár glacadh leis an deis athstruchtúrú a dhéanamh ar an gcóras sular ceapadh na boird Reatha –meileann muilte na Roinne Oideachais go mall – ach mairimis agus b’fhéidir go bhfaighimis féar.

Is trua go dtógann sé chomh fada ar an Roinn Oideachais na moltaí a chuireann an IPPN chun tosaigh a chur i bhfeidhm. Tá druma na scoileanna beaga agus a bPríomhoidí á mbualadh le 25 bliain. Dul chun cinn an-suntasach ab ea na laethanta riaracháin a ceadaíodh ach tá feabhas le cur orthu seo mar a léirigh Garaldine D’Arcy i Leadership+ Bealtaine/Meitheamh 2025 agus go leor moltaí eile a bhféadfaí gníomhú orthu gan mhoill ach an toil a bheith ann. Ní ar mhaithe leis féin a bhíonn an IPPN ag crónán.

Níor chuireas aithne ar phríomhoidí na scoileanna eile mórthimpeall orainn, seachas príomhoide na ngaelscoileanna, ach go tánaisteach. D’oibrigh Cumann na mBunscol mar ghréasán dom agus chabhraigh liom ar bhealaí éagsúla. Níor ghlacas páirt i ngrúpaí príomhoidí, ag ceapadh b’fhéidir nár bhain siad liom ar bhealach éigin. Tá brón orm faoi sin anois. Dhá bhliain ó shin ghlacas páirt i ngrúpa Meitheal, cruinnithe do phríomhoidí áitiúla chun buanna agus dúshláin a phlé, faoi stiúir áisitheora thuisceanaigh. Thaitin sé go mór liom. Bhaineas tairbhe as. Is é an príomhbhuntáiste ná an léargas a fhaigheann tú go bhfuil na dúshláin chéanna ag príomhoidí eile is atá agat féin, go bhfuil smaointe moltaí maithe acu ar conas déileáil leis na deacrachtaí agus go bhfuil moltaí maithe agamsa a fhéadfadh a bheith ina gcabhair uaireanta, chomh maith. Is í seo an teachtaireacht ba thábhachtaí a thugas liom ó chomhdhálacha bliantúla IPPN, chomh maith.

Má bhí aon duine ag ceapadh go raibh sé in am ag an IPPN na maidí a ligean le sruth anois, chruthaigh an chumarsáid mhí-réasúnta ó Oide – ní don chéad uair – agus an t-alt seo á scríobh againn sa tseachtain deireanach den bhliain scoile, maidir le laethanta inseirbhíse 2025- 2026, an gá le guth láidir IPPN a bheith le cloisteáil go soiléir go dtí Comóradh an 50. Gura fada buan mé/ tú/sé/sí/sinn/sibh/siad.

Is iontaobhaí é Colmán ar Cuala CLG agus is ball é den Bhord Stiúrtha Gaeloideachas. colman.odrisceoil@scoillorcain.ie

BRYAN COLLINS PRINCIPAL OF SCOIL NAOMH FEICHÍN, TERMONFECKIN, CO. LOUTH

Over the last two decades, IPPN has played a central role in my professional life and as I approach the final few months of my career as school principal, I’ve taken this opportunity to reflect on the impact the organisation has had on the role of school leaders and on me personally.

Over the last 25 years, IPPN has grown to become an integral part of the educational landscape in Ireland. It plays a vital role in ensuring that principals and deputy principals are provided with the supports and services to enable them to carry out their duties to the highest level, in a constantly evolving educational environment.

A number of years ago, I was very fortunate to be selected as a county representative for my adopted county of Louth and served in this role until I was elected onto the Board of Directors of IPPN in 2021. The role of county representative was indeed a very rewarding one as it helped me to build relationships with my colleagues in Louth and to see, at first hand, the amazing work that was being done in schools all over the ‘Wee County’. I also developed a much deeper understanding of the daily challenges that many school leaders were experiencing.

Following my election to the IPPN Board, I witnessed the incredible work going on, much of it unseen, to help alleviate the pressure on principals and deputy principals and to highlight the very obvious problem relating to the unsustainability of the role of school

(IPPN) plays a vital role in ensuring that principals and deputy principals are provided with the supports and services to enable them to carry out their duties to the highest level, in a constantly evolving educational environment.

principal. My enduring memory of my time on the Board of Directors is the efficiency of the team in the support office and the impressive calibre of the people who served with me on the board and in the organisation as a whole.

In my opinion, IPPN came into its own during the years of the Covid-19 pandemic. The organisation realised very quickly that school leaders had suddenly and unexpectedly found themselves in the eye of the storm and that they needed as much guidance and support as possible to enable them to successfully navigate their schools through this unprecedented crisis. IPPN did not let them down and many people in the organisation went over and above to support school leaders during that very challenging period.

The true value of local support and networking groups also became obvious at this time. With the backing of IPPN, the number of support groups increased dramatically due to the urgent and immediate need for mutual support. Here, in the northeast of the country, we have had the most wonderful level of engagement, with almost all of the primary schools becoming involved in support and networking groups in recent years. This has changed fundamentally the level of cooperation and collegiality between school leaders. Principals now don’t have to worry about feeling isolated and unsupported when experienced colleagues are only a WhatsApp message away. Given the proven success of the principals’ networking and support groups, it’s great to now see similar groups for Deputy Prinicipals being established as there’s little doubt that a model of shared and distributed leadership in our schools is the shape of things to come.

I’ve been extremely fortunate to have had the most fulfilling and rewarding teaching career and am eternally grateful to have been granted the opportunity to lead two wonderful schools over the last 29 years. It’s been a privilege for me to be involved in the IPPN organisation at different levels for most of that time and I sincerely hope that the immense contribution that IPPN has made, and continues to make, is fully appreciated by everyone involved in education in our country.

principal@scoilnaomhfeichin.ie

FINBARR HURLEY

OIDE PRIMARY LEADERSHIP COORDINATOR AND DONEGAL CLUSTER COORDINATOR

When the four schools in the Donegal cluster joined Phase 1 of the Small Schools Project (SSP), what lay ahead was unknown. What unfolded was quietly transformative. One of the earliest and most valued supports was yard supervision. Just seven hours per term by vetted, non-teaching staff enabled teachers to take proper breaks – long overdue and much appreciated. This small intervention offered real relief, giving leaders and teachers space to connect, interact and regroup.

A more significant shift came with the flexibility to merge principal release days with Special Education Teaching (SET) hours. Having a full-time teacher in school brought continuity for pupils and a stronger rhythm for staff. In rural areas, recruiting for a single day was impractical – this change offered a workable, sustainable solution.

Collaboration also extended into procurement. The principals jointly sourced contractors for solar panels, fire safety and cleaning services, with each taking responsibility for different areas of procurement. These shared efforts didn’t cost the system more but resulted in tangible savings and improved efficiency.

Pupil wellbeing took centre stage. Joint activities such as concerts, chess competitions and wellbeing days helped to reduce isolation, nurtured friendships and supported pupil voice. These inter-school events made a lasting impact on school culture.

Shared training opportunities also emerged. Secretaries engaged in informal networks that continue to offer mutual support. Principals benefitted from Oide Coaching and structured reflection, helping align leadership

The Donegal Cluster’s journey is not marked by dramatic change. Instead, it has been shaped by thoughtful, strategic actions grounded in trust, context, and a commitment to shared improvement.

approaches. Deputy Principals, with three annual release days, began collaborating across schools –strengthening distributed leadership in a practical, collaborative way.

Joint planning, especially for DEIS, became more focused and aligned. The shared commitment to improvement drove better outcomes, particularly around the themes of attendance and pupil transitions.

The trust that was built proved vital during the Creeslough tragedy. In that crisis, the support from within the cluster – emotional and professional –was immediate and sincere. It reminded us that clustering is not simply logistical; it’s deeply relational.

In Phase 2, the appointment of an Executive Officer (EO) added a new layer of support. Well spent time beforehand shaped the role – and considered communication, workload, and what would truly help. There was both excitement and uncertainty as this was completely new, but a shared belief in the potential made it a reality.

Andrea, the EO, began by visiting each school, listening carefully, and understanding the realities. She mapped common tasks – schoolbooks, utility bills, summer works, health and safety audits

– and looked for ways to streamline them. Her approach was methodical, collaborative and grounded in what was manageable and useful.

A shared Google Doc is now used to log tasks. This is a live, evolving tool. Items are added, prioritised and followed up. Secretaries are actively involved and Andrea manages much of the follow-through. The result? Less duplication, more clarity and more time for learning and teaching.

Already, the mental load has shifted. With Andrea in her role, interruptions are fewer and responses quicker. One principal noted the impact on sleep, clarity and overall wellbeing – having that support brought genuine peace of mind.

While the role continues to evolve, its value is clear. Phase 2 is not simply about operational support; it’s about reclaiming time and energy to focus on pupils, staff and leading learning and teaching.

The Donegal Cluster’s journey is not marked by dramatic change. Instead, it has been shaped by thoughtful, strategic actions grounded in trust, context and a commitment to shared improvement. This phase is not only about logistics – it’s about creating space to lead, to teach and to breathe again. Ultimately, the learning from this and the other Small School Cluster Projects and phases will inform future DEY policy, which has the potential to dramatically change things for the better in all small schools.

If you would like to get in touch with Finbarr in relation to this piece, you can send him an email at finbarr.hurley@oide.ie

RAY McINERNEY NATIONAL COORDINATOR, SUMMER PROGRAMME FOR SPECIAL SCHOOLS

This article highlights the experiences, insights and outcomes of the Summer Programme in special schools across the country, whose reflections provide a rich picture of leadership, innovation and impact.

As National Coordinator of the Summer Programme for Special Schools, I have had the privilege of supporting Special Schools as they considered, planned and delivered their programmes. I expected challenges, but I have been genuinely in awe of the creativity, innovation and determination shown by the 82 Special Schools that delivered programmes this summer.

What has stood out most is the authentic school leadership that emerged, particularly from teachers and staff who do not hold formal leadership roles but stepped forward to organise and manage complex programmes. Many described the experience as transformational.

They led diverse staff teams of teachers, SNAs, newly-qualified teachers and bus escorts, while coordinating logistics, off-site trips, daily transport, activity scheduling and pupil groupings tailored to individual needs. They overcame challenges like recruiting and training unfamiliar staff, supporting transitions, incorporating parent feedback and responding to unexpected issues with OLCS and external providers. All of this was done while creating a programme that was joyful, safe and inclusive for pupils inkeeping with DEY’s core aim of ‘building confidence and connections’ for Summer Programme 2025.

As one organiser put it, ‘I never thought of myself as a school leader but after this, I’m thinking differently.’

Running a Summer Programme is a unique and authentic demonstration of school

The real success of the Summer Programmes was reflected in the joy, confidence and sense of belonging experienced by the pupils who participated. Pupils laughed in classrooms, were curious on outings and took part in multiple activities such as sensory play, drumming, art, yoga, kayaking, trips, discos, library visits, beach walks and science experiments.

leadership in action. It demands strategic thinking, collaboration, problem-solving and the ability to inspire and manage a team. Summer Programmes are excellent opportunities for developing future school leaders and that is something we should recognise and encourage.

The real success of the Summer Programmes was reflected in the joy, confidence and sense of belonging experienced by the pupils who participated. Pupils laughed in classrooms, were curious on outings and took part in multiple activities such as sensory play, drumming, art, yoga, kayaking, trips, discos, library visits, beach walks and science experiments. The list goes on but what matters most is the impact, clearly seen in the smiles, confidence and strong sense of connection and inclusion. Feedback from pupils, parents and staff alike speaks to the positive and lasting effect these programmes had on everyone involved.

‘For many of our pupils, this was their first summer camp style experience and they absolutely thrived.’

Some schools used the programme to support transitions to adult services. Others made strategic use of daily diaries and photos to help pupils reflect on what they had learned. One school embedded elements of pupils’ IEP targets into the programme and developed reflective notes to inform next year’s class teams.

A school with over 60 pupils in their programme noted that having a high ratio of known staff, 28 from their own school, made all the difference, providing continuity, trust and familiarity. The enhanced terms and conditions of the Summer Programme for Special Schools introduced by the DEY was very significant in enabling this.

What’s remarkable is not just what Special Schools achieved, but what they overcame to make it happen. One Special School, despite undergoing major Summer Works, relocated their entire programme to another venue to run an engaging two-week Summer Programme for their pupils. That kind of logistical leadership deserves recognition.

Another outstanding example was the innovative collaboration between a Special School and the Munster Technological University (MTU) with the Summer Programme being hosted in the MTU campus. This was a brave move that involved stepping into a new environment, with all the logistical challenges and initial anxieties that entailed, for staff and pupils. Yet the result was transformative: pupils experienced learning in a third-level setting, gaining exposure to new spaces,

people and possibilities. The aspiration is that this collaboration can serve as one model for future Summer Programmes on tertiary campuses across the country.

Another outstanding example of inclusion was the Special Schools that took the further step of offering places on their programmes to pupils from other schools who were unable to access Summer Provision locally. These acts of generosity underscore the deep commitment to equity and child wellbeing at the heart of special education. ‘We’re proud of how well the programme ran.’

A key theme that emerged this year was increased responsiveness to parent and pupil voice. Several schools made a deliberate effort to act on parent feedback from previous years. One school tailored their activities around parent input and delivered a varied programme with outings to a castle, horse riding centre, museum, wetland park and more. In-school sessions included baking, tie-dyeing and art. The result was a richer pupil experience and higher parent satisfaction.

‘The positivity from our pupils and parents has been overwhelming’, one Summer Programme Coordinator wrote.

The success of the programme would not have been possible without the targeted supports introduced by the DEY, including the shorter school day, enhanced grants and particularly the initiative allowing Special Schools to recruit two NQTs for June. These NQTs seamlessly continued working into the Summer Programme, already familiar with school routines and familiar to the pupils.

Successes bring learnings and there are items for improvement for 2026. Some schools reported frustrations with the OLCS/Esinet system. The retrospective payment model has been identified as a source of strain for some schools who had difficulty confirming bookings with activity providers who required upfront or same-day payments.

To every Special School, every Summer Programme Organiser and Manager, every staff member who worked on

a Summer Programme in a Special School – thank you. Your work has been exceptional.

To our partners: The Department of Education and Youth; the National Association of Boards of Management in Special Education (NABMSE); the Irish Primary Principals’ Network (IPPN); the National Association of Principals and Deputies (NAPD); the National Parents’ Council (NPC); teacher unions; OIDE; ESCI, NCSE, NEPS and Boards of Managementthank you for backing this initiative. But let this be a beginning, not an exception. Special Schools need the same system-wide support during the school year as they received this summer. The challenges they face including staffing, therapy access, recruitment, transport, staff burnout etc, do not disappear in September. ‘Special Schools are centres of excellence. Let us ensure their voices are heard all year long.’

The Summer Programme for Special Schools demonstrates what can be achieved through system-level collaboration, local leadership and a shared commitment to meeting the needs of pupils with complex special educational needs. From the promotion of authentic leadership through the roles of Summer Programme Organisers and Managers, to the innovative deployment of newlyqualified teachers and the alignment of enhanced resources with needs, the Summer Programme has shown that when the right supports are in place, Special Schools can deliver truly transformative experiences for their students. As we look to the future, we must build on this model, strengthening what we’ve learned and exploring new models for Summer Programmes that further expand access, inclusion and innovation. Most importantly, we must continue to support Special Schools all year round in meeting their well-identified and unique challenges.

If you would like to get in touch with Ray in relation to this piece, you can email him at ray.tulla@gmail.com

BRIAN O’DOHERTY IPPN DEPUTY CEO

As part of IPPN’s Sustainable Leadership project, we conducted an evidence-informed analysis of primary school leadership. That analysis identified: the extent to which the workload of school leaders was expanding year-on-year the disproportionate focus of that workload on administrative and bureaucratic tasks the impact of this on the effectiveness and sustainability of leadership roles the impact of this on the health

that divert their attention away from their core purpose as a school leader – the leadership of teaching and learning. A central focus of IPPN’s advocacy work has been on creating an awareness of this reality and proposing solutions that would enable a greater focus on core purpose.

As a direct result of that advocacy work, the DEY has initiated the piloting of an Administrative Executive role in a small number of primary and post-primary schools. Each school in the pilot will employ an administrator to undertake a

The pilot is being funded by the DEY, and an action research approach is being adopted. The process to recruit these Administrative Executives is nearing completion and a Project Group has been established to guide and oversee the implementation of the pilot/action research project and its evaluation. IPPN is represented on this Project Group.

We wish the participating schools well and trust the experience will have a profoundly positive impact on leadership capacity and school

Emma Coughlan, delves into the outcomes of notable school-related personal injury claims and the factors influencing their resolution. Through these cases, we aim to provide schools with insights into effective risk management and the importance of adhering to protocols.

Case 1:

A 12 year old pupil left the school building to go outside. They ran up the steps to the footpath and was then running on the footpath, within the school grounds, when she stumbled and fell which resulted in a fractured elbow. The students parents filed a claim for injuries following the incident. Initially, they claimed to have been tripped by another pupil, but later attributed the fall to a defective steel grating. We denied liability on behalf of the Board of Management, citing inconsistencies in the plaintiff’s account and evidence from an SNA and CCTV footage indicating the fall occurred away from the alleged defect. It was hugely significant that the CCTV was retained.

The judge dismissed the plaintiff’s claim, citing a lack of credible explanation for the change in their account and preferring the evidence of the SNA and CCTV footage, which showed the fall occurred near the steps, not the grating. The judgment concluded that the incident was part of ordinary schoolyard activity and did not establish liability on the part of the Board of Management.

Strengths to defending the claim: The principal examined the accident locus following the incident and identified no defect CCTV footage of the incident was retained, this is not always the case

The SNA willing to give evidence in court

A group of 5th and 6th Class students were playing football on the school football field. Twenty five students played on the field during lunch break with three supervisors in the field area. A student fell to the ground during a tackle, he was in bad pain and said he had banged his knee and his knee had ‘popped out’. The teachers carried the student to the staff room and rang the parents. The parents brought student to the doctor. The students parents filed a claim for injuries following the incident. We defended the claim against the Board of Management for over six years, we gathered our expert report from engineers, solicitors, barristers and doctors. The incident giving rise to this claim happened in a pleasant grassy area where there was plenty of room for the children to play. The yard was properly supervised. It is entirely conceivable that this incident could have happened without anybody being negligent and in particular without negligence on the part of the school. It is most unlikely that any other child was in anyway negligent. There was no suggestion of any violence or untoward activity. From obtaining medical records we identified that this was a recurring knee injury. We put the injured party and their parents on full proof of accident circumstances and alleged injuries. We believed this was a simple accident and unfortunate injury with no negligence on behalf of the Board of Management and as such were confident in defending the claim. We “served notice of trial” meaning Allianz instigated the process to get

the trial to court and as we prepared for hearing the students’ parents withdrew the claim against the Board of Management.

Strengths to defending the claim: Lunch time rota retained by principal Statements from supervising teachers and SNA gathered at time of incident

Teachers examined the accident locus at the time of the incident and confirmed no defect on pitch Parents called and notified of incident and medical treatment received

While some of the strengths in defending both claims can seem basic and straight forward, these can sometimes be overlooked by schools. Taking these actions like retaining CCTV footage and inspecting the accident locus can be key to defending claims.

If you are insured with Allianz directly and would like to discuss any potential liability issues in your school, then please contact your local Allianz CRE. If you are otherwise insured, then you should contact your intermediary.

TOM LONERGAN NATIONAL COORDINATOR FOR DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY INFRASTRUCTURE AT OIDE TECHNOLOGY IN EDUCATION

In today’s primary school educational context, ensuring your school technology infrastructure is fit for purpose is both a short-term operational matter, as well as a longer-term strategic priority. Oide Technology in Education (Oide-TiE) understands that school leadership and digital learning teams are experts in teaching and learning, though not in infrastructure, and need guidance and support on the more technical aspects of technology infrastructure. As such, we provide a range of guidance and supports for school leadership teams, written in non-technical language, that simplify infrastructure approaches for schools. In this article, we’ve highlighted some of these priority areas:

Firstly, school technology infrastructure needs to support a school’s teaching and learning goals. Oide-TiE’s Digital Technology Infrastructure (DTI) guidance helps school leaders understand how to align infrastructure, like computing devices and Wi-Fi, with pedagogical goals, without needing any technical expertise to do so. Oide’s ‘Digital Technology Infrastructure Guide for School Leaders’ is written specifically for leaders with this in mind.

Teachers and pupils need robust mobile devices, such as laptops, iPads or Chromebooks, with good battery life to support learning throughout the school day. Matching appropriate technologies with specific school contexts helps to ensure more effective use of technology in schools. Teachers need to be equipped with devices that allow them to carry out key activities to support teaching and learning outcomes. Devices for pupils also need to support a wide range of activities that allow students to engage effectively in learning activities.

we provide a range of guidance and supports for school leadership teams, written in nontechnical language, that simplify infrastructure approaches for schools.

To support schools in specifying and purchasing appropriate DTI, Oide-TiE provides a number of specific templates, specifications and supports to simplify the procurement process for schools.

Schools that have a high-quality technical support approach in place with suitable external IT providers benefit greatly from this model, as external providers can focus on the technical areas, such as having a high quality, robust and reliable DTI in place, and this enables schools to focus their energies and expertise on teaching and learning areas.

Learning platforms that align with learning goals and integrate smoothly into the school ecosystem have become essential educational tools for schools. Oide-TiE offers specific guidance to help schools evaluate and choose learning platforms that meet their needs to support teaching, learning and assessment.

Cybersecurity needs to be a high priority for the school leadership team in terms of protecting school systems and school data, to reduce the risk of a cyberattack or a data breach. Schools increasingly store sensitive data and rely on interconnected systems, making them attractive targets for a cyberattack.

Oide TiE has recently developed a range of cybersecurity guidance and supports in seven priority areas. These include a ‘School Cybersecurity Policy Template’ to guide schools in improving their cybersecurity policy and practice in this area.

Assessing School Infrastructure

To assist schools in assessing their own infrastructure, Oide-TiE has developed a ‘Digital Technology Infrastructure Audit Tool’ to ensure infrastructure is suitable, robust and meets recommended minimum technical specifications. DTI audits need to be carried out by a professional IT provider with the relevant technical expertise, and experience of working with schools.

Where can schools find further guidance and support?

The Oide-TiE DTI team has developed a number of important guides for school leadership and digital learning teams in the areas highlighted in this article, as well as in other areas. These guides and other supports are available on our website at:

LINK Link to Digital Technology Infrastructure

Schools can contact Oide TiE by email at ictadvice@oide.ie Follow on social media – Twitter/X

PAUL O’DONNELL PRINCIPAL OF ST PATRICK’S NS, SLANE, CO. MEATH

Beginning as a principal felt like an attempted ascent on Mont Blanc, in winter, scantily clad and with no compass. Early in my career, I had physical pains from constant new encounters and hard lessons that had to be learned every day. They were certainly real. I still ache just thinking about them.

I attended my first IPPN conference just after being appointed. Many say that the best lessons are learned incidentally at such events. I concur. Making a dart for the coffee dispenser, I bumped into a ‘Badger’ of a principal (his words, not mine) who had a mop of black hair with silvering sides. We struck up conversation, and I asked him for any advice that might make the job easier. Without drawing breath, he whistled through his top five tips, which are summarised below. For me, at the time, it was like gold dust.