HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND

Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication

Legal Category: Product subject to prescription which may be renewed (B).

Marketing Authorisation Number: EU/1/12/795/002; EU/1/12/795/007.

Marketing Authorisation Holder: AstraZeneca AB, SE-151 85 Södertälje, Sweden. Further product information available on request from: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals (Ireland) DAC, College Business and Technology Park, Blanchardstown Road North, Dublin 15. Tel: +353 1 609 71 00.

FORXIGA is a trademark of the AstraZeneca group of companies.

Veeva ID: IE-4697 Date of Prep: February 2023

IN THIS ISSUE:

NEWS: Ireland wins Medical World Cup Page 5

HOSPITAL

PHARMACY: Antimicrobial Resistance Position Paper Page 8

FEATURE: Vitamin D Intake and Status in Ireland

Page 14

MEDICINES: Opioid Prescribing Updates

Page 24

ONCOLOGY FOCUS: National Cancer Mission Hub Page 26

ONCOLOGY FOCUS: Prostate Cancer Page 36

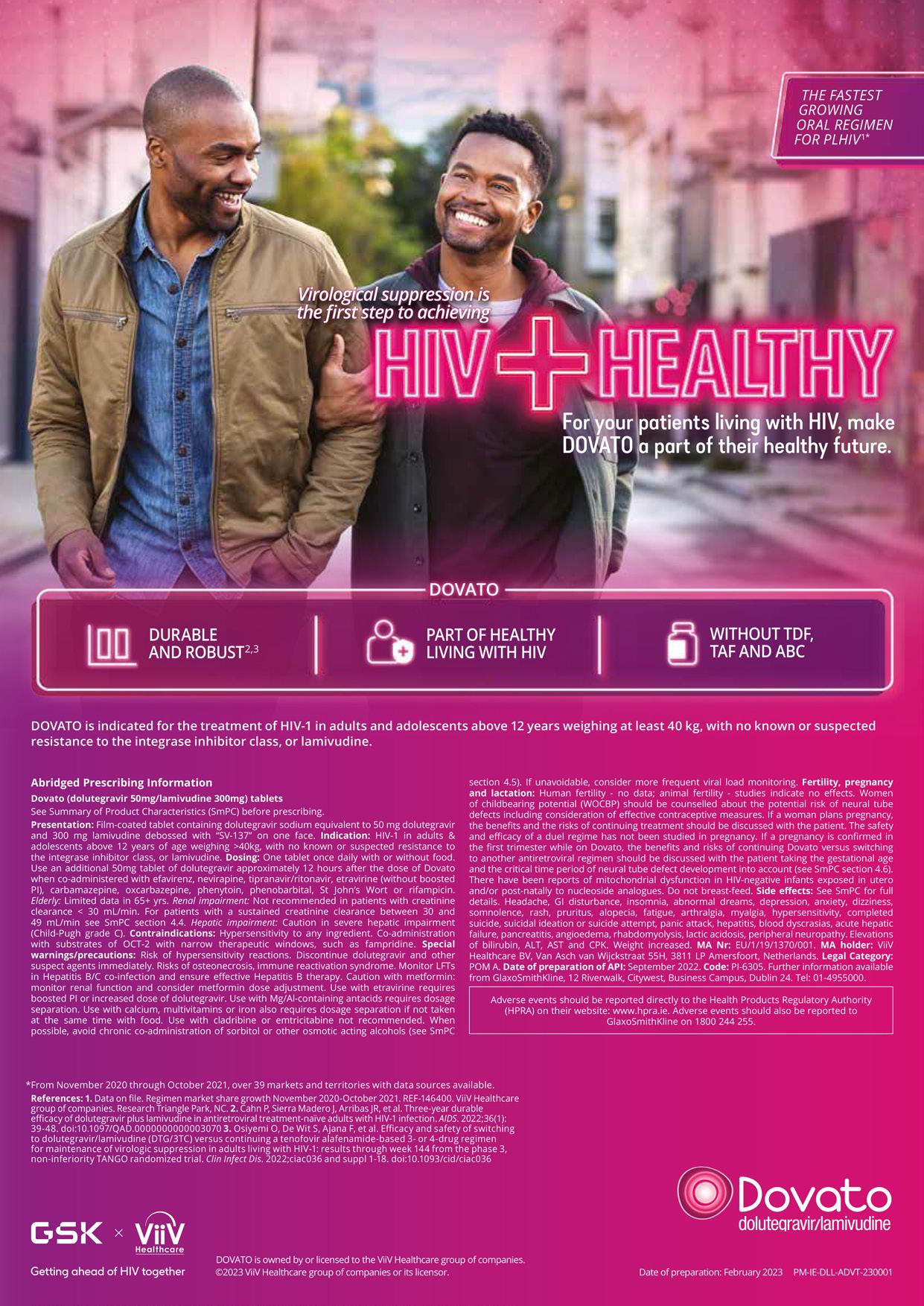

STUDY: HIV Viral Suppression Page 70

HPN September 2023 Issue 112 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE This Publication is for Healthcare Professionals Only

This is a promotional advertisement from LEO Pharma for IE healthcare professionals.

For the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult and adolescent patients 12 years and older who are candidates for systemic therapy1

TIME TO PRESS PLAY

Prescribing Information for Adtralza® (tralokinumab) 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe

Please refer to the full Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) (www.medicines.ie) before prescribing.

This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. This will allow quick identification of new safety information. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions. Indications: Treatment of moderate-tosevere atopic dermatitis in adult and adolescent patients 12 years and older who are candidates for systemic therapy. Active ingredients: Each pre-filled syringe contains 150 mg of tralokinumab in 1 mL solution (150 mg/mL). Dosage and administration: Posology: The recommended dose of tralokinumab for adult and adolescent patients 12 years and older is an initial dose of 600 mg (four 150 mg injections) followed by 300 mg (two 150 mg injections) administered every other week as subcutaneous injection. Every fourth week dosing may be considered for patients who achieve clear or almost clear skin after 16 weeks of treatment. Consideration should be given to discontinuing treatment in patients who have shown no response after 16 weeks of treatment. Some patients with initial partial response may subsequently improve further with continued treatment every other week beyond 16 weeks. Tralokinumab can be used with or without topical corticosteroids. The use of topical corticosteroids, when appropriate, may provide an additional effect to the overall efficacy of tralokinumab. Topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used, but should be reserved for problem areas only, such as the face, neck, intertriginous and genital areas. If a dose is missed, the dose should be administered as soon as possible and then dosing should be resumed at the regular scheduled time. No dose adjustment is recommended for elderly patients, patients with renal impairment or patients with hepatic impairment. For patients with high body weight (>100 kg), who achieve clear or almost clear skin after 16 weeks of treatment, reducing the dosage to every fourth week might not be appropriate. The safety and efficacy of tralokinumab in children below the age of 12 years have not yet been established. Method of administration: Subcutaneous use. The pre-filled syringe should not be shaken. After removing the pre-filled syringes from the refrigerator, they should be allowed to reach room temperature by waiting for 30 minutes before injecting. Tralokinumab is administered by subcutaneous injection into the thigh or abdomen, except the 5 cm around the navel. If somebody else administers the injection, the upper arm can also be used. For the initial 600 mg dose, four 150 mg tralokinumab injections should be administered consecutively in different injection

IL, interleukin.

sites within the same body area. It is recommended to rotate the injection site with each dose. Tralokinumab should not be injected into skin that is tender, damaged or has bruises or scars. A patient may self-inject tralokinumab or the patient’s caregiver may administer tralokinumab if their healthcare professional determines that this is appropriate. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients. Precautions and warnings: If a systemic hypersensitivity reaction (immediate or delayed) occurs, administration of tralokinumab should be discontinued and appropriate therapy initiated. Patients treated with tralokinumab who develop conjunctivitis that does not resolve following standard treatment should undergo ophthalmological examination. Patients with pre-existing helminth infections should be treated before initiating treatment with tralokinumab. If patients become infected while receiving tralokinumab and do not respond to antihelminth treatment, treatment with tralokinumab should be discontinued until infection resolves. Live and live attenuated vaccines should not be given concurrently with tralokinumab. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: There is limited data from the use of tralokinumab in pregnant women. Animal studies do not indicate direct or indirect harmful effects with respect to reproductive toxicity. As a precautionary measure, it is preferable to avoid the use of tralokinumab during pregnancy. It is unknown whether tralokinumab is excreted in human milk or absorbed systemically after ingestion. Animal studies did not show any effects on male and female reproductive organs and on sperm count, motility and morphology.

Side effects: Very common (≥1/10): Upper respiratory tract infections. Common (≥1/100 to <1/10): conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, eosinophilia, injection site reaction. Uncommon (≥1/1,000 to <1/100): keratitis. Precautions for storage: Store in a refrigerator (2°C-8°C). Do not freeze. Store in the original package in order to protect from light. Legal category: POM. Marketing authorisation number and holder: EU/1/21/1554/002. LEO Pharma A/S, Ballerup, Denmark. Last revised: October 2022

Reference number: REF-22407

Reporting of Suspected Adverse Reactions

Adverse events should be reported.

Reporting forms and information can be obtained from: HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Website: www.hpra.ie

Adverse events should also be reported to Drug Safety at LEO Pharma by calling +353 1 4908924 or e-mail medical-info.ie@leo-pharma.com

References: 1. Adtralza® SPC. 2. Duggan S. Drugs 2021;81(14):1657–1663. 3. Bieber T. Allergy 2020;75:54–62.

Date of preparation: December 2022

more at www.adtralza.ie Adtralza®

Learn

biologic

The first

licensed

that inhibits IL-13 alone, 1,2 a

key driver of atopic dermatitis signs and symptoms.3

IE/MAT-62263 Further information can be found in the Summary of Product Characteristics or from: LEO Pharma, Cashel Road, Dublin 12, Ireland. E-mail: medical-info.ie@leo-pharma.com

® Registered trademark

Not an actual patient. For illustrative purposes only. Individual results may vary.

Medical Drone delivery service starts in Ireland P4

Electronic Health Record System gains Investment P6

New discovery in Epilepsy Treatment P7

New Options for Prostate Surgery P12

Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis P18

HIV Viral Suppression P70

Smart Devices in Diabetes Management P72

REGULARS

Oncology Focus: Cervical Cancer P41

Oncology Focus: Bladder Cancer P47

Oncology Focus: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer P54

Feature: Osteoporosis P74

Editor

In one of our lead news stories, Bon Secours Health System (BSHS) has launched a groundbreaking clinical transformation project with healthtech firm MEDITECH which is to connect its entire hospital network using one electronic healthcare record (EHR).

The new 'BonsConnect' initiative, which will be the largest private hospital EHR system in Ireland, will improve patient safety, enhance clinical care, increase operational efficiency, and revolutionise the healthcare experience for the 300,000 patients Bon Secours treats annually.

Turn to page 6 to read the full story.

Meanwhile on page 8, we detail a recent Position Paper published by the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists on Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Resistance. Combating infectious diseases requires the implementation of a comprehensive intervention package comprised of measures including but not limited to prudent anti-infective use, vaccination and stewardship.

The Position Paper calls on national governments and health system managers to utilise the specialised background and knowledge of hospital pharmacists in multi-professional antimicrobial stewardship teams or other forms of antimicrobial governance in the hospital and in the community. It also underlines that hospital pharmacists are an integral part of the transfer of care to ensure that care could continue when patients leave the hospital.

Opioid analgesics are highly effective in the management of acute severe pain. Dr Cormac Mullins, Consultant in Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine at Cork University Hospital and South Infirmary Victoria University Hospital gives readers an overview of Opioid Prescribing from the recent updated CDC Prescribing Guidelines in this issue.

Hospital Professional News is a publication for Hospital Professionals and Professional educational bodies only. All rights reserved by Hospital Professional News. All material published in Hospital Professional News is copyright and no part of this magazine may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form without written permission. IPN Communications Ltd have taken every care in compiling the magazine to ensure that it is correct at the time of going to press, however the publishers assume no responsibility for any effects from omissions or errors.

PUBLISHER

IPN Communications Ireland Ltd

Clifton House, Lower Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2 (01) 669 0562

GROUP DIRECTOR

Natalie Maginnis n-maginnis@btconnect.com

EDITOR

Kelly Jo Eastwood

EDITORIAL

editorial@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

ACCOUNTS

Fiona Bothwell cs.ipn@btconnect.com

SALES EXECUTIVE

Avril Boyd avril@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

SALES & TRAINING MANAGER

Swan Mude s.mude@hospitalprofessionalnews.ie

CONTRIBUTORS

Helena Scully | Eamon Laird

Kevin McCarroll | Martin Healy

Paul Sweeney | Padraig Daly

Dr Jason McGrath | Dr Gordon Daly

Mr Luke Cox | Dr Damir Vareslija

Amy Nolan | Rebecca Gorman

Dr Roisin McAvera | Zekiye Altan

Dylan Harvey | Rory Johnson

Professor Ronan Cahill | Martina Phelan

Ciara O’Connor | Mr Faraz Khan

Therea Lowry-Lehnen | Dr Cormac Mullins

James Bernard Walsh

Professor Donal Brennan

Professor William Gallagher

Professor David Galvin

Professor Leonie Young

Professor Fergal Malone

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Ian Stoddart Design

‘Despite a lack of evidence for their benefit in chronic pain, their use has increased substantially in many developed countries, including in Ireland. Increased prescribing rates can lead to opioid-use disorder and opioid diversion, with many patients reporting not disposing of finished opioid prescriptions’ he notes. You can read the full article starting on page 24.

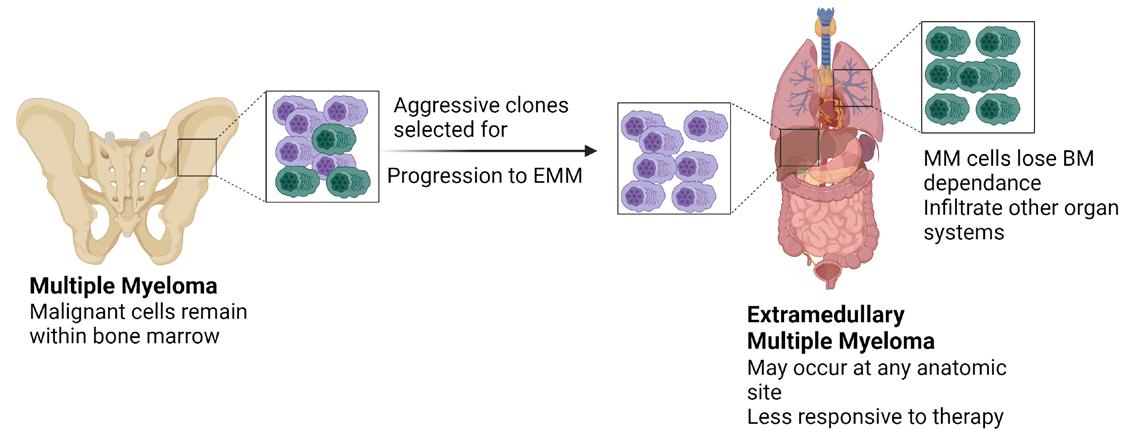

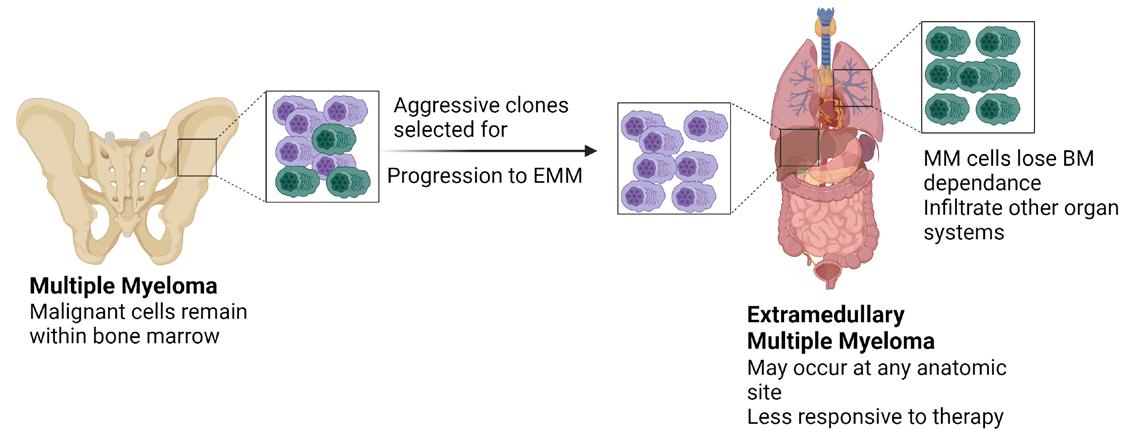

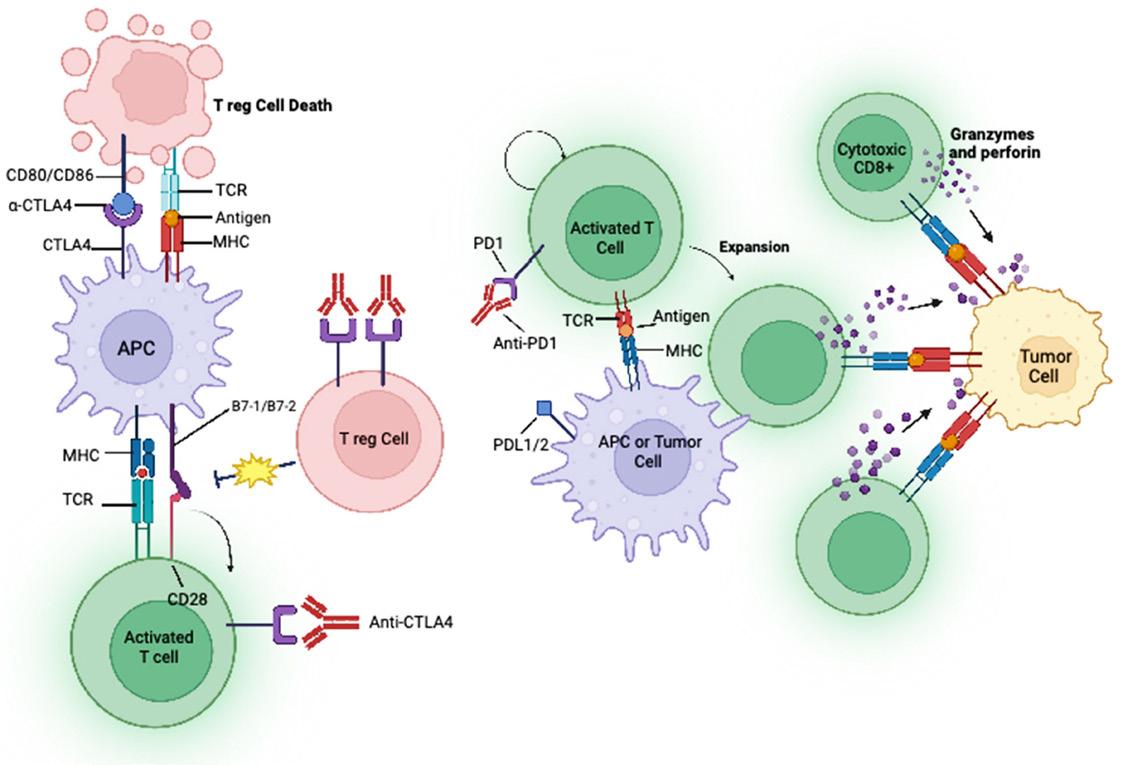

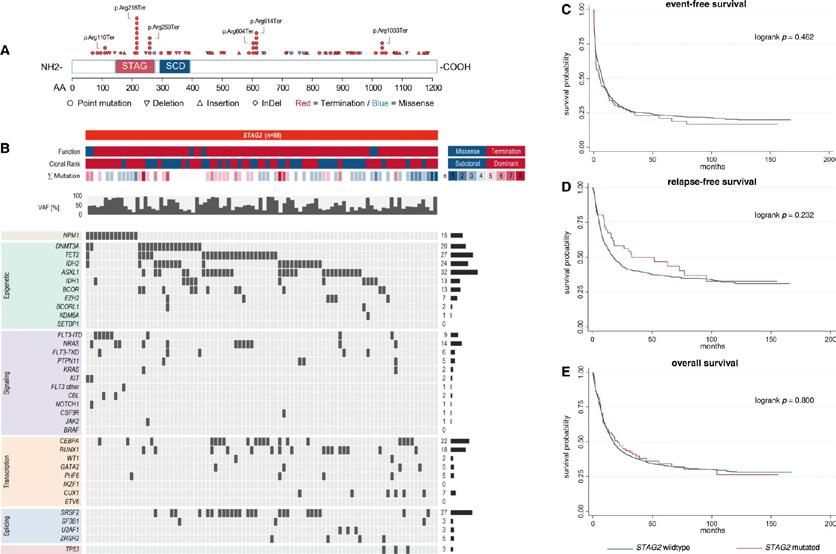

The Special Focus for September is on Oncology, with some excellent clinically contributed articles covering a wide area of cancers. These include Professor David Galvin, Paul Sweeney and Padraig Daly discussing ‘Life Limiting Prostate Cancer,’ Professor Ronan Cahill and Mr Faraz Khan, University College Dublin and the Mater Misericordiae University Hospital who write on ‘Handheld Robotic Systems for Minimally Invasive Surgery’ and Dr Roisin McAvera who authors an article on page 52 about ‘Extramedullary Multiple Myeloma.’

I hope you enjoy the issue.

3 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023 September Issue Issue 112 4

Contents Foreword

Clinical R&D: P80 12 7 72 HOSPITAL PROFESSIONAL NEWS IRELAND Ireland’s Dedicated Hospital Professional Publication HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE @HospitalProNews HospitalProfessionalNews

Medical Drone Delivery Service in Ireland

Speed and timeliness are crucial when delivering vital medical and pharmaceutical items to patients and hospitals. Wing and Apian, a United Kingdom-based company connecting healthcare providers with drone operators and services, have partnered to begin medical drone delivery services in Ireland and jointly explore opportunities in the UK. We expect to begin working with hospitals and other care providers in Dublin later this year.

Over the coming months, Wing and Apian will work with healthcare and pharmacy partners to create a rapid medical delivery network in South Dublin. This efficient network, leveraging Wing’s aircraft and automation, will serve to improve the patient experience while reducing traffic congestion and emissions in the community. We look forward to engaging with the local community and stakeholders as we develop the operations and begin flights.

Wing’s highly automated delivery drones are well-suited for a range of useful healthcare applications; our technology is designed to deliver pharmacy items, laboratory samples, and medical devices and supplies very quickly in urban and suburban environments.

Together, Wing and Apian believe that healthcare should benefit from on-demand delivery much like consumers do in their personal lives. Medical drone delivery can provide a faster, more reliable, lower-cost solution than ground-based alternatives. We aim to address speed, inefficiencies, and also environmental challenges by reducing vehicles on the road. Wing’s operations require very little infrastructure and can be set

up in a range of spaces, making them suitable for a wide variety of healthcare facilities.

Regulatory progress in the European Union and the UK continues to open doors toward safe and beneficial drone services at scale. This operation will be Wing’s second in Ireland, following the public demonstration services in Lusk, where thoughtful input and the collaborative approach from the community have provided

Bon Secours open New Wards

invaluable feedback on the future of drone delivery. At Wing, we also look forward to future opportunities in the UK after years of collaboration with regulators and contributions to numerous policy forums.

Drone delivery in healthcare has a tremendous opportunity for scale, both in operational service and in benefits delivered to patients and providers. We’re pleased to invest in these outcomes alongside Apian.

patient centric, technologically advanced care to patients from North Dublin and further afield.

The new wards represent a ¤14 million investment and are part of Bon Secours Health System's ambitious ¤300 million national investment, aligned with their 2025 Strategic Plan.

Bill Maher, BSHS Group Chief Executive, highlighted that this expansion is part of a larger plan to upgrade our services continuously. Bon Secours Health System has consistently strived to combine the latest medical technologies with compassionate and personalized care, ensuring our patients receive the exceptional care they deserve. We remain dedicated to meeting the evolving needs of our patients and communities sustainably.

Sharon Morrow, Chief Executive of Bon Secours Hospital Dublin, underlined the significance of this milestone, as it enables us to deliver technologically advanced surgical and oncology services to patients in the region. Our commitment to advanced medicine and exceptional care remains unwavering as we prioritize patient well-being within a world-class and modern environment.

4 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Bon Secours Hospital recently welcomed Minister Paschal Donohoe to officially open the brand-new surgical and oncology day wards at the Bon

Secours Hospital Dublin. These new state-of-the-art facilities mark a significant milestone for healthcare in Dublin and increases the hospital’s capacity to provide

Minister Paschal Donohoe, Sharon Morrow and Bill Maher, Bon Secours Hospital Dublin

Lessons not being Learned

The Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) has commented on the publication of the independent report by the Mental Health Commission into the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS).

The Association said, “The report published today by the Mental Health Commission, the scale and severity of the findings and recommendations must be taken as cause for serious action.

“Unfortunately, many of the findings are not surprising to those who are working within Ireland’s

mental health services on a day-to-day basis. We are trying to provide care in very complex and constrained conditions for young people who need care for urgent severe mental health crises – being able to ensure their timely assessment, care and follow-on monitoring is critical but incredibly challenging in the current environment.

“Time and time again, Consultants and others in the service have raised the serious concerns about staffing and capacity shortages and highlighted the impact this has

Hospital Pharmacy Congress

The next European Association of Hospital Pharmacists Congress will take place in Bordeaux, France, between 20 and 22 March 2024 and will focus on Sustainable healthcare – Opportunities & strategies.

The abstract submission is now open until 1 October 2023. All hospital pharmacists, other healthcare professionals, and scientists are strongly encouraged to submit their work for consideration by the EAHP Scientific Committee. If accepted, this could lead to the display at the annual EAHP Congress. The registrations for the Congress are also open and you can benefit from an Early Bird Rate.

on young people’s mental health and their ongoing care needs. Lessons are not being learned.

“Meanwhile, the growing deficits are stark. Currently CAMHS funding is approximately 0.63% of the overall Health Budget, at just ¤125.18m.

“This report confirms that the vast majority of CAMHS teams are significantly below the recommended staffing levels, some below 50% of recommended levels. Some of these services are missing a third of the required Psychiatry Consultants, as these

Ireland wins World Medical Cup

A team of medical doctors from Ireland have won the World Medical Football Championships.

The 11-strong Ireland team beat Britain 1-0 in Vienna to claim the crown after playing a gruelling six games in seven days.

They came out on top of 24 teams from around the world, with the winning goal scored by Dr Fergal Moran, nephew of Ireland football legend Kevin Moran.

Ireland’s team are a group of doctors of various specialities and grades who come together to compete under the Irish flag at the annual World Medical Football Championships. Their first venture into this long-running tournament (it began in Barcelona in 2004) came in Long Beach, USA in 2014. Since then they have competed in Barcelona, Leogang (Austria), Prague and Cancun.

The team also manage the longstanding annual Hospitals Cup competition, where teams from hospitals all over the country compete for the title. This tournament began as far back as 1948 and has been running consistently since. This year, teams from the Mater, St Vincent's,

the Federated Hospitals (St James & Tallaght), Cork, Waterford and Galway will compete for the title. The team says, “We seek to promote the value of team sport

permanent posts remain vacant or only filled on a temporary, agency, or locum basis.

“There are many strands that have to come together, involving all pillars of the health system –GPs, Consultants, Allied Health Professionals - to ensure these highly vulnerable patients are cared for as required.

“Our hope is that this report drives such a collaborative, whole-ofservice approach to ensuring an end-to-end care pathway under the oversight of dedicated clinical leadership for CAMHS.”

for physical & mental health to physicians, patients and the population at large, leading by example.”

The team of medical doctors from Ireland who won the World Medical Cup

5 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023

News

¤25m investment in Electronic Health Record System

“BonsConnect is the next step in our digital journey and will change how care is delivered at our five hospitals, including our new hospital in Limerick, due to open in 2025”

Bon Secours Health System (BSHS) has launched a groundbreaking ¤25 million clinical transformation project with healthtech firm MEDITECH which is to connect its entire hospital network using one electronic healthcare record (EHR).

The new 'BonsConnect' initiative, which will be the largest private hospital EHR system in Ireland, will improve patient safety, enhance clinical care, increase operational efficiency, and revolutionise the healthcare experience for the

300,000 patients Bon Secours treats annually.

The new EHR project is part of a significant investment in state-ofthe-art equipment and technology within a wider ¤300 million national commitment by Bon Secours Health System as part of its 2025 Strategic Plan.

The BonsConnect project will create 30 new jobs in BSHS now, with a further 30 positions to be created in September. It will cover the full Bon Secours hospital

network in Cork, Galway, Limerick, Tralee, and Dublin, and is to be completed by the summer of 2025. To facilitate the execution of this project, Bon Secours Health Systems is partnering with Nordic, a global consultancy that exclusively supports healthcare systems to deliver digitally-enabled transformation. Leveraging their clinical expertise, extensive technical knowledge and strategic advice, they will play a crucial role in ensuring the project's successful implementation.

Steps to Eliminate Hepatitis C

This World Hepatitis Day, the HSE urged people at risk of Hepatitis C to order a free Hepatitis C test. Thousands of people at risk are now able to order a test to their home, as the HSE steps up its bid to eliminate the deadly disease.

The HSE National Hepatitis C Treatment Programme estimates that up to 3,000 people in Ireland may currently have the bloodborne virus, which infects the liver and if left untreated can cause serious and potentially life-threatening damage, leading to cirrhosis, possible liver failure and cancer – as well as a risk of spreading the disease to others.

Over 4,000 at-home Hepatitis C tests have been ordered and delivered since the HSE home test service went live in early April this year. The discreet, at-home tests are free to order online from www. hse.ie/hepc as part of the HSE’s Hepatitis C Treatment Programme, which has already treated over 7,000 people, 95 percent of whom are now cured.

The test involves a finger prick test, with a tiny blood sample dropped into a test tube, which is posted in a pre-paid envelope to a lab for analysis. Those who require follow up treatment will then be contacted and referred to a participating clinic or hospital.

Treatment for Hepatitis C is free, tablets are effective and welltolerated, with over 95% of people cured in as little as 8 to 12 weeks. The new home tests could help people unknowingly living with Hepatitis C to get a life-saving diagnosis and treatment sooner. The new self-test aim to reach people who may not be engaged with other services such as drug and alcohol support, as well as people who may have potentially been exposed to virus in the past, through previous injecting drug use, or they could have come into contact with infected blood through medical procedures, blood transfusions and blood

Bon Secours Health System

Group Chief Executive, Bill Maher, said, "Bon Secours Health System continues to be unrivalled in the quality of our service, combining the latest medical technologies and approaches with compassionate and personalised medical care. BonsConnect is the next step in our digital journey and will change how care is delivered at our five hospitals, including our new hospital in Limerick, due to open in 2025. This will lead to improved clinical decision-making, more efficient and accurate clinical documentation, and an increased level of access to the right information by the right person at the right time."

Helen Waters, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, MEDITECH, added, “We are excited that Bon Secours Health System has selected MEDITECH Expanse as the EHR to lead its digital transformation journey, and we look forward to supporting them in their mission to improve the health and wellbeing of their communities. Our new partnership provides an extraordinary opportunity to work together and use the latest technology to drive patient-centred care, improve patient access, and enhance the clinician experience while ensuring equitable access to quality care across the communities they serve.”

products, or equipment used in cosmetic services.

Professor Aiden McCormick, HSE Clinical Lead for the Hepatitis C Programme, said: “One of our biggest challenges is that as patient numbers get smaller, remaining Hepatitis C cases are harder to find and treat. Therefore, it’s vital that we offer a free, easy to access home test – especially for those who have been exposed to the virus but are reluctant to come forward. This latest tool is critical to ensuring more people can receive the treatment they need, or peace of mind, at the earliest opportunity. The results of these tests will help contribute to understanding the prevalence of Hepatitis C.”

6 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Molecule that could help Epilepsy Seizures

In a discovery that could lead to new treatments for epilepsy, a study led by RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences and FutureNeuro has identified a previously unknown ‘master controller’ of electrical signals in brain cells.

The study showed that the molecule could be a useful target for future medicines to help control seizures in epilepsy, which is one of the most common chronic brain diseases, affecting around 65 million people worldwide. Around one in three people with epilepsy have uncontrolled seizures despite being treated with currently available anti-seizure medication. The study, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), took a broader look at what naturally controls how our brain cells communicate.

All of our brains need electrical signals to function. These signals begin with the entry of charged sodium ions into neurons through dedicated channels, which act like gates or doorways on the surface of the cells. In people with epilepsy these channels become overactive, leading to higher-frequency signals that generate seizures.

Calming effect

The ‘master controller’ molecule discovered by the team at RCSI and FutureNeuro, the SFI Research Centre for Chronic and Rare Neurological Disease, is called microRNA-335, a type of ribonucleic acid (RNA) that occurs naturally in our brain cells. By sticking to the messages that instruct how to assemble the channels, microRNA-335 lowers the amounts of sodium channels in brain cells.

In a series of experiments on human-derived cells growing in the lab, the study found that reducing the amount of microRNA-335 in neurons increased the amount of sodium ions that moved into the cells and caused the brain cells to become more excitable. This finding underscores the calming actions of microRNA-335.

The researchers also carried out early, pre-clinical tests in the lab using gene therapy that could deliver microRNA-335 specifically to neurons, and saw that it resulted in an encouraging reduction in seizures.

Finding this master-controller of sodium channels opens up opportunities to develop new treatments for controlling

Dr Mona Heiland, Postdoctoral Researcher, SFI FutureNeuro Centre and RCSI Department of Physiology and Medical Physics

seizures in epilepsy, according to researcher Dr Mona Heiland from FutureNeuro and RCSI Department of Physiology and Medical Physics.

“Overall, we think that microRNA-335 is acting as a regulator of brain excitability, and could be a potential new target for the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsies,” she said.

Seizure control

Professor David Henshall, Director of FutureNeuro and Professor of Molecular Physiology and Neuroscience at RCSI commented: “The discovery of this new potential treatment target opens up the possibility of long-lasting and improved seizure control for patients in the future.”

The highly collaborative international project involved

many partners, including the Interdisciplinary Nanoscience Centre at Aarhus University and Omiics, both in Denmark; the Epilepsy Center Frankfurt Rhine-Main at University Hospital Frankfurt in Germany; and the Department of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology at University College London. The research was funded by Science Foundation Ireland, Framework Programme 7 and the Welcome Trust.

Raising the Bar for Interventional Oncology

St. Vincent’s University Hospital (SVUH), a world-leading academic teaching hospital, is proud to announce its enrolment as an IASIOS Enrolled Centre, marking a significant milestone in its journey towards achieving IASIOS Accreditation in Interventional Oncology (IO).

IASIOS, the International Accreditation for Interventional Oncology Services, ensures the highest standards of quality and patient care in IO through its globally recognised accreditation programme. As a member of IASIOS, SVUH is committed to providing the highest quality care to its patients, aligning with internationally accepted standards.

IASIOS is based on the CIRSE Standards of Quality Assurance in Interventional Oncology, a document endorsed by the European Cancer Organisation (ECO) and 40 international societies. This enrolment demonstrates SVUH’s dedication

to delivering exceptional interventional oncology services.

Professor David Brophy, Consultant Diagnostic & Interventional Radiologist at St. Vincent’s University Hospital, said, “We are proud to join the IASIOS community as an Enrolled Centre. This is a significant milestone in our journey towards achieving IASIOS Accreditation. It reflects our unwavering dedication to providing the best possible care to our patients in the field of interventional oncology.”

SVUH extends its gratitude to Prof. David Brophy and the dedicated members of the Interventional Radiology Multidisciplinary Team for their invaluable contributions throughout the enrolment process. Their expertise and

commitment have played a pivotal role in this achievement.

As an IASIOS Enrolled Centre, SVUH becomes part of a global community of IO centres working collaboratively to develop and promote IO practice, while raising

awareness about its benefits among patients and medical providers. IASIOS community members have exclusive opportunities to learn from one another, network, and participate in various social events, seminars, and workshops.

7 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023

News

Professor David Brophy with members of the Interventional Radiology Multidisciplinary Team

Hospital Pharmacy

Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Resistance Hospital Pharmacists Association adopts

new Position Paper

prevent the further spread of antimicrobial resistance, the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) urges an interprofessional approach in the healthcare setting and during the transition of care. Hospital pharmacists in Europe are ready to champion infection prevention and contribute and promote the prudent use of antimicrobials through the enforcement of antimicrobial stewardship. To improve patient outcomes proactive steps need to be taken.

Stewardship

This year's General Assembly of the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) adopted a new Position Paper on Infectious Diseases and Antimicrobial Resistance. Combating infectious diseases requires the implementation of a comprehensive intervention package comprised of measures including but not limited to prudent anti-infective use, vaccination and stewardship. In order to maintain the efficacy of antimicrobial drugs and to prevent the further spread of antimicrobial resistance, it is essential to have an interprofessional approach in the healthcare setting and during the transition of care.

The Position Paper calls on national governments and health system managers to utilise the specialised background and knowledge of hospital pharmacists in multi-professional antimicrobial stewardship teams or other forms of antimicrobial governance in the hospital and in the community. It also underlines that hospital pharmacists are an integral part of the transfer of care to ensure that care could continue when patients leave the hospital.

Investing in prevention strategies, infection control and immunisation should be considered and further consolidating the role of hospital pharmacists in European vaccination strategies is paramount. In this sense, the universal application of prevention and control measures published by the European Centre for

Disease Prevention and Control

and the World Health Organisation among healthcare professionals and the public it is recommended in the fight against infectious diseases. Considering the One Health Approach, adequate regulatory oversight and proper implementation of measures in the veterinary sector and the environment on global, European, national and local levels need to be addressed.

Governments need to make arrangements so that essential antibiotics in dosage forms and strengths appropriate for both adults and children will

be maintained on the market with contingency stock level arrangements and alternative production by hospital pharmacists enabled where necessary.

Below is a brief overview of the paper.

Combatting infectious diseases requires the implementation of a comprehensive intervention package comprised of measures including but not limited to prudent anti-infective use, vaccination and stewardship

To maintain the efficacy of antimicrobial drugs and to

The emergence of antibiotic resistance is widely recognised as a major public health problem. According to the European Commission and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the number of patients in the EU that die each year as a result of infections caused by resistant bacteria increased from 25.000 in 2017 to 35.000 in 2020.

In the last decades, there has been dramatic growth in the ability of a microorganism to stop an antimicrobial from working against it. As a consequence, only a limited number of antibiotics are available for the treatment of infections caused by resistant bacteria. Other consequences for patients are that infections

EAHP calls on national governments and health system managers to utilise the specialised background and knowledge of the hospital pharmacist in multi-professional antimicrobial stewardship teams or other forms of antimicrobial governance in the hospital and in the community.

EAHP requires that hospital pharmacists are an integral part in the transfer of care to ensure that the patient care started in hospitals can be continued in the community.

EAHP asks for the inclusion of concrete measures, like the outcome measures provided by the Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance, in national action plans that increase the uptake of stewardship teams.

EAHP calls for further consolidating the role of hospital pharmacists in European vaccination strategies.

EAHP recommends the universal application of prevention and control measures by ECDC and WHO among healthcare professionals and the public in the fight against infectious diseases.

EAHP advocates for adequate regulatory oversight and proper implementation of measures in the veterinary sector and the environment on global, European, national and local levels.

EAHP demands increased investment to support the development of innovative proposals and the encouragement of research projects in new fields of infectious disease control such as immunotherapy and sustainability.

EAHP urges governments to make arrangements so that essential antibiotics in dosage forms and strengths appropriate for both adults and children will be maintained on the market with contingency stock level arrangements and alternative production by hospital pharmacists enabled where necessary.

8 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

persist, which results in longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and an increased risk of the infection spreading to others. Thus, significant interprofessional actions are needed to ensure standard treatments and prevention of serious diseases with effective and safe medicines that are quality-assured, used appropriately, and accessible to all who need them.

The escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance is a global public health concern and now seriously jeopardises the effectiveness of standard treatments, rendering some ineffective for their approved indications. Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) teams are an indispensable tool that promote the rational use of antimicrobial agents, selection of optimal drugs, dosing, duration of therapy, route of administration and the use of antibiotic susceptibility testing to reduce the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. In Sweden, AMS has formed an integral part of the strategic programme against antibiotic resistance for the past 20 years. The first European adoption of the IDSA (Infectious Disease Society of America)

Practice Guidelines based on a new evaluation of the literature including European publications was performed in 2013 and published by an interdisciplinary working group from Austria, Germany and Switzerland.

The primary goal of AMS is to optimise clinical outcomes while minimising unintended consequences of antimicrobial use. Consequently, EAHP calls on national governments and health system managers to utilise the specialised background and knowledge of the hospital pharmacist in multi-professional antimicrobial stewardship teams or other forms of antimicrobial governance in the hospital and in the community.

Seamless transitions between the interfaces of different health settings need to be considered during the implementation of multi-professional antimicrobial stewardship teams or other forms of antimicrobial governance in the hospital and in the community. EAHP requires that hospital pharmacists are an integral part in the transfer of care to ensure that the patient care started in hospitals can be continued in the community.

Need for further implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes

AMS is still a long way from being routine in European hospitals. This is despite the scientific results of efficient reduction of antibiotic overuse, positive contributions to resistance development and even cost savings through AMS.

ECDC also supports the strengthening of the fight against AMR i.e. through an AMS toolkit with a special section including hospital pharmacists’ involvement. The EU Commission strongly supports AMS as an important tool in their publications, e.g. EU Guidelines for the prudent use of antimicrobials in human health. Besides the positive effects on patient treatment and sustainability of antibiotic therapy, there is also a cost-benefit described in the literature. EAHP asks for the inclusion of concrete measures, like the outcome measures provided by the Transatlantic Taskforce on Antimicrobial Resistance, in national action plans that increase the uptake of stewardship teams.

One Health Approach

Public health interventions, preventive measures and changes in human behaviour have proven to be effective tools against infectious diseases over many decades. The COVID-19 pandemic has put the spotlight on vaccination strategies, vaccine development and other preventative measures. To curb the spread of infectious diseases, the efforts of prophylaxis like vaccination and hygiene are important and need to be further enhanced. Prevention of infectious diseases should be strengthened by integrating vaccination planning developed for the fight against them and providing all healthcare professionals with access to vaccine records.

Hospital pharmacists – as part of the vaccination team across healthcare sectors – are raising awareness about vaccine safety, supporting vaccine administration processes and sharing clear information with citizens that have questions. They play a significant role in providing information to their fellow healthcare professional colleagues on vaccines, their development, differences and administration patterns and by that influence the perception of vaccines and their importance for combating diseases.

Hospital pharmacists, because of their specialised training are able to guarantee the safe handling of vaccines and are in a position to support the traceability and vigilance of vaccines. In the context of national vaccination awareness programmes the involvement of the expertise of hospital pharmacists as trusted sources of information is important for adequately informing the public. They are also essential societal pillars that lead by example by being vaccinated themselves and that provide objective and trusted information to improve public health. EAHP calls for further consolidating the role of hospital pharmacists in European vaccination strategies. Similarly to vaccination, existing prevention toolkits and hand hygiene as the single most important prophylactic measure need to be boosted. The prevention toolkit for healthcare professionals in hospitals and other healthcare settings of ECDC, to which EAHP contributed from the perspective of the hospital pharmacist, is for example a measure that should be promoted. EAHP recommends the universal application of prevention and control measures published by ECDC and WHO among healthcare professionals and the public in the fight against infectious diseases.

Incentives

Increasing resistance, particularly of carbapenem resistance and vancomycin resistance in Europe, means that specific funding actions are necessary for the benefit of the patient. Despite the commitments of the European Commission and others in relation to the support of research and developments further incentives are needed.

It is crucial that the revision of the EU’s general pharmaceutical legislation addresses the increase of European production sites to lower dependency on international markets and the development of new antibiotics. It is however questionable if transferable exclusivity vouchers are the right incentive to increase development, especially since any option of such upfront nature has not been tested before. Unpredictable results, including costs and also the lack of tailored conditions ensuring access to the new antibiotics, could be the consequence.

At the same time, a prolonged exclusivity period for the medicines

to which the voucher is applied puts respective patients at a potential risk of diminished competition in the market both in terms of supply chain fragility (resulting in secondary shortages) and also higher costs. In addition, quality metrics to discourage the development of unnecessary or ineffective antibiotics would need to be put in place. EAHP demands increased investment to support the development of innovative proposals and the encouragement of research projects in new fields of infectious disease control such as immunotherapy and sustainability.

Keeping old and established but still essential antibiotics on the market

In addition to the development of new antibiotics, universal access to old and established antibiotics that are being utilised in new ways needs to be maintained. The growing and more frequent shortages of antimicrobials are an additional contributing factor to AMR affecting the effectiveness of antimicrobials worldwide.30 The shortage of amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid has severely impacted treatment options for patients across Europe. Medicines shortages of antimicrobial drugs compromise their prudent use and must be avoided. Surveys conducted by EAHP in 2019 and 2020 showed that antibiotic shortages ranked among the top three medicinal products in shortage. Measures need to be taken by countries, including national governments, pharmaceutical industry, healthcare professionals, patients as well as other stakeholders at the pan-European level, to lower the risk of antibiotic shortages, especially since substitution supported by the AMS team is not always possible. Sweden and the UK are already piloting subscription-based models that provide a sufficient antimicrobial product supply guarantee. Studies that gather further information on this, including those securing access to essential legacy/establish antibiotics, should be supported. EAHP urges governments to make arrangements so that essential antibiotics in dosage forms and strengths appropriate for both adults and children will be maintained on the market with contingency stock level arrangements and alternative production by hospital pharmacists enabled where necessary.

9 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023

News

Hospital Capacity Deficits hit Young People

The Irish Hospital Consultants Association (IHCA) has expressed its continuing concern at the excessive number of children waiting for an appointment to be treated or assessed in public hospitals.

The warning from Consultants comes as the latest National Treatment Purchase Fund (NTPF) figures released reveal that 895,700 people were on some form of hospital waiting list at the end of July, including almost 100,800 children and young people. While a recent report highlighted the extent of extreme capacity shortages in Ireland’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), the IHCA’s analysis shows that similar capacity deficits are resulting in lengthy waiting lists across a

number of paediatric specialties, including Ear, Nose & Throat (ENT), Dermatology, Orthopaedics and Cardiology – with some being forced to wait months or years for assessment or treatment.

The IHCA said that difficulty in filling permanent Consultant posts and growing hospital and mental health capacity deficits against increases in demand are the root causes of the unacceptably long child waiting lists. One in five (20,600) children are waiting longer than a year for treatment or assessment by a hospital Consultant. Latest HSE data reveals the number of unfilled permanent Consultant posts has risen to a record 933.2 This is the highest Consultant vacancy rate ever.

Hospital diagnostics are not included in NTPF data which

accounts for an additional 8,916 children awaiting CTs, MRIs or ultrasounds at the three Dublin paediatric hospitals alone, bringing the total number awaiting care to almost 110,000 – or 1 in 12 children in the country.3

In addition, a near record 4,421 children4 were on separate CAMHS waiting lists at the end of May 2023 – 128 (3%) additional children added so far this year.5 The CAMHS waiting list has increased by almost a quarter (+865 or 24%) since the start of 2022 and has almost doubled (+2,094 or +90%) since the start of 2020.6

Commenting on today’s waiting lists, IHCA President Professor Robert Landers, said, “The monthly NTPF figures have recorded over 100,000 children on waiting lists for hospital care for

Irish National Orthopaedic Register

Mr John Kelly, Orthopaedic Consultant Clinical Lead

the fifth consecutive month, with one in five of these children waiting longer than a year to be treated or assessed in public hospitals. This is resulting in thousands of children not getting the care they need in a timely way, and the real possibility that they will suffer serious and lasting health and developmental issues that could have been reversed or mitigated against if only they were seen in time.

“As Consultants, we need and want sustainable solutions to help alleviate this distress and provide the care these children so desperately need. However, we have unresolved hospital capacity deficits and Consultant vacancies that is not being addressed urgently enough. These twin deficits must be addressed by the Government in October’s Budget.”

The National Office of Clinical Audit (NOCA) is pleased to announce that Sligo University Hospital (SUH), which is part of the Saolta Hospital Group, has become the 18th hospital in Ireland to roll out the Irish National Orthopaedic Register (INOR). The aim of this initiative is to monitor and improve the quality of care for individuals receiving joint replacement surgery in Ireland.

INOR is a secure, web-based, real-time system which provides a national electronic register of patients receiving joint replacement surgery in Ireland. Elective orthopaedic hip and knee replacement records will now be available nationally in a central register for the first time. The register will collate information from Sligo and will support early detection of implant performance

and improve the efficiency of the recall and review process.

Mr John Kelly, Clinical Lead for the INOR Project in Sligo University Hospital said: “The INOR is a great development for SUH. Sligo is now at the forefront of Arthroplasty use in Ireland and this leverages emerging technology and infrastructure to enable better surgical outcomes for our patients.”

Following patient consent, the INOR will collect information electronically at pre-operative, surgical and post-operative assessment stages, from patients who are undergoing joint replacement surgery. This will in turn support early detection of implant performance and improve patient experience with their implant over a longer time.

Mr James Cashman, National Clinical Lead for INOR welcomed the introduction of INOR to Sligo

University Hospital. He highlighted the “important contribution INOR makes to audit and good clinical governance, as well as allowing us to expedite notifying patients in the unlikely event of an implant recall occurring.”

Over the past three months, much work was undertaken by the local SUH implementation team for INOR in conjunction with the INOR national team to ensure implementation readiness across all relevant areas of Sligo University Hospital.

Gráinne McCann, General Manager of Sligo University Hospital welcomed the implementation, saying “We are pleased to formally become part of this national register so that we can continuously monitor and improve services we provide to our patient, ensuring quality standards of care within our services.”

INOR went live in May 2016 and is managed by NOCA, in conjunction with the HSE Office of the Chief Information Officer and clinically supported by Irish Institute of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgeon (IITOS). Roll-out of INOR to the remaining public elective orthopaedic surgery sites is underway and will be completed by early 2023. Implementations of the private hospital are also under way.

10 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

From left: Micheál Bailey, Irish National Orthopaedic Register; Farnan Golden, IT; Aine Duffy, Arthroplasty Nurse Specialist; Caroline Quinn, CNM3 Perioperative Directorate; Ruth McManus, CNM 2, PAC; Michelle Gilroy, CNM2, TQIP; and

Viatris

Empowering people

worldwide to live healthier at every stage of life

With 1,600 people working across five sites in Ireland, Viatris provides access to medicines, develops innovative solutions and improves healthcare for patients.

Newenham Court, Malahide Road, Dublin 17, Dublin, Ireland.

Viatris.ie

Job Code: CC-2023-001

Date of Preparation: July 2023

www.viatris.ie

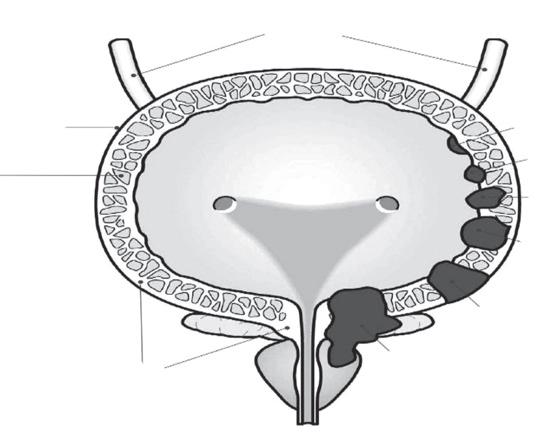

New Option for Prostate Surgery

A team led by Consultant Urologist Prof Rustom Manecksha recently carried out a new type of minimally invasive procedure treating BPH in the Reeves Day Surgery Centre at TUH

Our hospital and in particular the urology service has a long tradition of innovation, the introduction of this new therapy is a welcome addition to the number of ways we can treat an enlarged prostate, many of which are minimally invasive. This means our patients spend less time in hospital and have a shorter recovery time so they can get back to living their lives.”

prostate tissue. The treated tissue is then gradually reabsorbed by the body, reducing the size of the prostate and easing the symptoms for the patient. It is typically performed as a day procedure, using sedation or a short general anaesthetic.

One in four men over the age of 40 in Ireland will suffer from an enlarged prostate gland. In medical terms this is referred to as Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) and in simpler terms an enlarged prostate*.

Earlier last month, a team led by Consultant Urologist Professor Rustom Manecksha carried out

Safety Notice

a new type of minimally invasive procedure treating BPH in the Reeves Day Surgery Centre at Tallaght University Hospital.

Professor Rustom Manecksha, Consultant Urologist who carried out the procedures commented “This week we have provided an alternative treatment for what is a common medical problem.

The innovative treatment (Rezūm) uses water vapour therapy to target and shrink the excess prostate tissue. When the steam contacts the prostate tissue the stored energy is release into the tissue. In time the body absorbs the treated tissue, reducing the size of the prostate. This relieves the urinary obstruction and improves urinary flow.

During the procedure, a specialised device is directed to deliver small bursts of heated water vapor directly into the

It is a new and alternative treatment option, which adds to the options already offered, including UroLift, which the Urology team in TUH introduced in 2019. Plasma vaporisation and bipolar prostate resection, Rezūm is a new and effective alternative to traditional surgical treatments for BPH, providing patients with symptom relief with minimal side effects and a quicker recovery time.

*When the prostate becomes enlarged it places pressure on the bladder and urethra (the tube that urine passes through). This can cause dribbling at the end passing urine, often feeling like the bladder has not fully emptied, needing to go to the toilet often even during the night leaving you feeling tired. If it is ignored and not treated it can lead to bigger problems with the kidneys and the bladder.

The marketing authorization holder of Simponi, Janssen Biologics B.V., and the local representative, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ireland (Human Health) Limited, in agreement with the European Medicines Agency and the Health Products Regulatory Authority, would like to inform you of the following: Summary

• Accidental needle stick injuries, bent or hooked needles, and device actuation failure have been reported for the Simponi SmartJect pre-filled pen.

• Instructions for use have therefore been revised as follows:

o Do not put the cap of the pre-filled pen back if removed, to avoid bending the needle.

o Only inject in the thigh or abdomen.

o Use a two-hand approach to administer the injection (one hand to hold the pre-filled pen and the other hand to press the blue button to start the injection).

o Do not pinch the skin, when positioning the pre-filled pen and when administering the injection.

• The device must be pushed against the skin until the green safety sleeve slides completely into the transparent cover BEFORE the blue button is pressed. Only the wider portion of the green safety sleeve remains outside of the transparent cover.

• All patients/caregivers, including those previously trained on the SmartJect pre-filled pen, should be instructed on the proper use of the device in accordance with the revised instructions for use.

Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Annual Symposium - St Luke’s open for bookings

16 – 20 October 2023 | Hybrid event

The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Annual Symposium - St Luke’s is open for bookings. The symposium will take place online and in person from 16 to 20 October 2023 touching on the themes of clinical leadership, resilience, and climate and health. Throughout the symposium, these themes will be explored through a series of exciting events including a public art exhibition, our annual public meeting, the symposium day, and the ever-popular Heritage event. The Annual Stated Meeting will take place on 18 October 2023.

12 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE News

Upskilling with Online CPD

RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences has created a new suite of online CPD short courses for healthcare practitioners looking to upskill and advance their careers.

The short continuous professional development (CPD) courses are provided via RCSI’s digital learning platform, RCSI Online, and are available to those working in healthcare and allied healthcare roles anywhere in the world. Running over five-week terms, the courses are delivered by experts

and time-independent. We are developing a growing portfolio of topics relevant to the current and anticipated needs of healthcare professions, with content delivered by subject-matter experts with industry and sectoral experience and expertise.”

To learn more about the short courses available on RCSI Online, visit https://www.rcsi.com/online/ courses/short-courses

Future of Future of pharmacIE pharmacIE

13 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023

News

Connect with future pharmacists at APPEL's exclusive careers event. Book your ticket now! TICKETS Friday, 20th October 1pm - 4pm RCSI, 123 St Stephen

Vitamin D Intake

Vitamin D intake and status in Ireland: a narrative review part 1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 February 2023

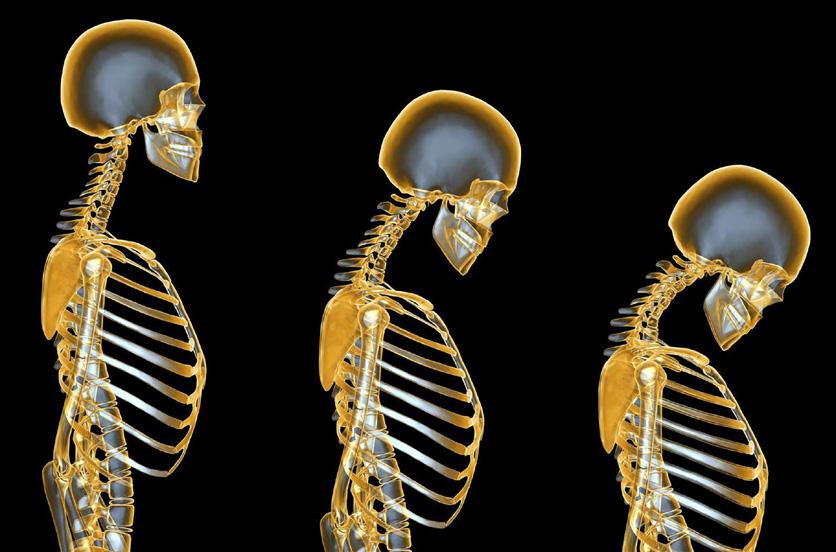

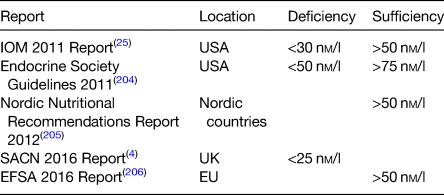

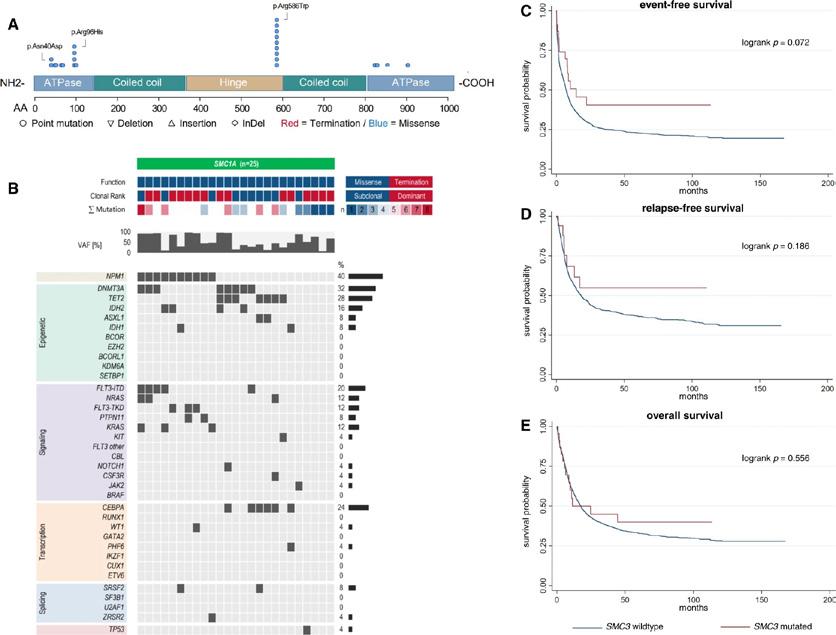

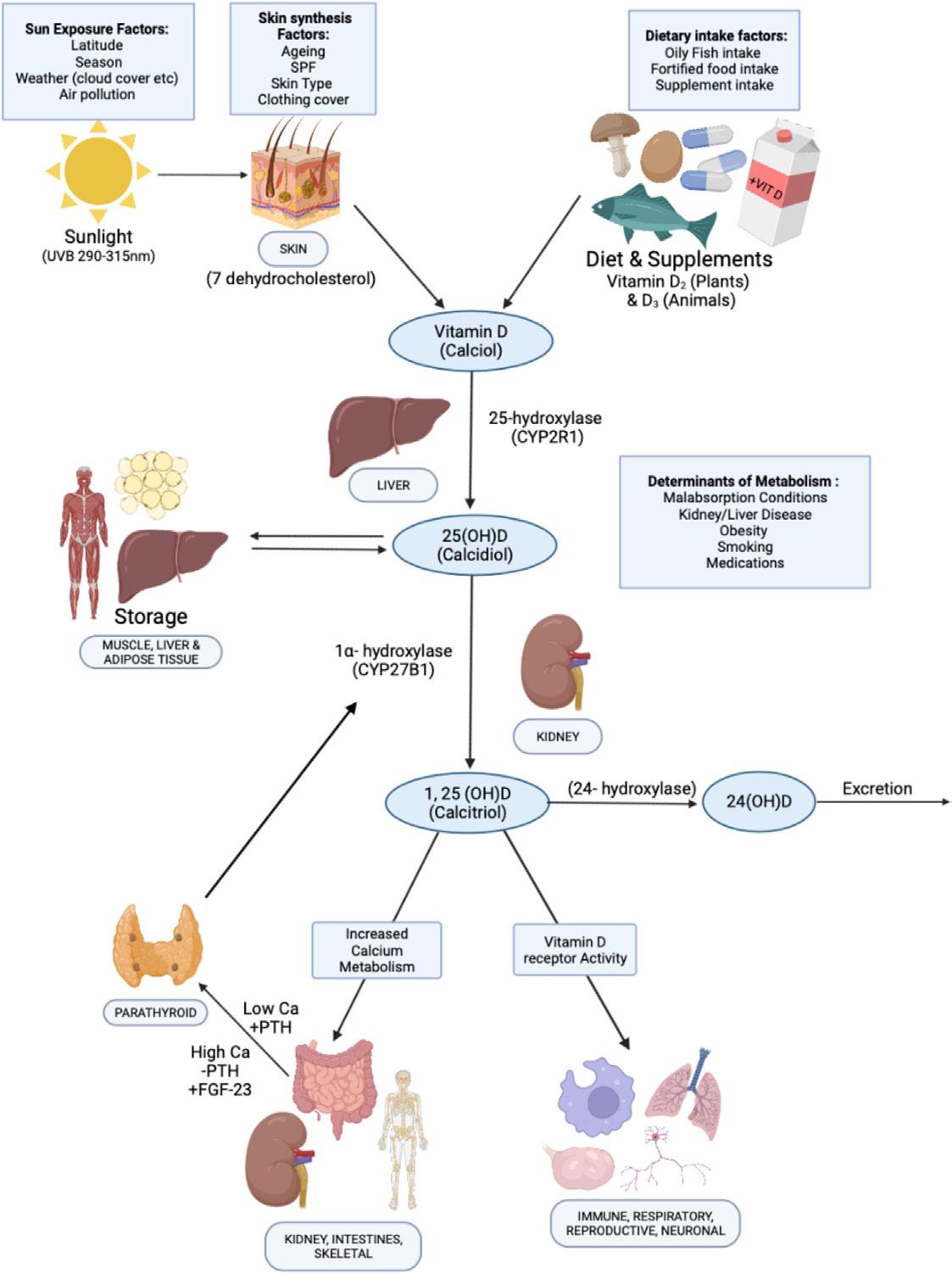

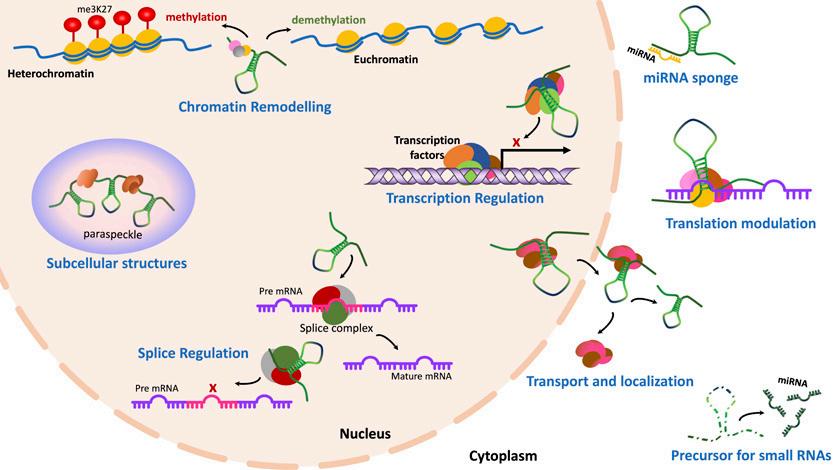

Vitamin D is crucial for musculoskeletal health, being required for the adequate absorption of calcium from the gastrointestinal tract. Vitamin D is a secosteroid synthesised via the action of UVB light on the skin, forming cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) (Figure 1).1 While this is the predominant physiological source of vitamin D, it can also be obtained from the diet in animal and plant foods (ergocalciferol or vitamin D2) and from fortified foods.2, 3 Its role in bone health is well established,4 with deficiency increasing the risk of rickets in childhood and osteomalacia in adults.1 Secondary hyperparathyroidism due to vitamin D deficiency can result in musculoskeletal pains and muscle weakness.5 Peak bone mass, which may determine up to 60 % of osteoporosis risk in later life can only be achieved with sufficient vitamin D and calcium intake.1 The role of vitamin D may also extend beyond bone health. For example, vitamin D receptors are found in numerous cells including immunological (T- and B-cells), osteoblasts, β cells and mononuclear cells, and in many organs such as the brain, heart, reproductive and the gut.6 Interaction of transcription factors [1,25-hydroxyvitamin D2 (1,25(OH)D2)] with the vitamin D receptors modulates gene expression, influencing numerous physiological functions including anti-cancer, immunological and

anti-inflammatory effects.7, 8 Thus, it may be involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension, stroke and CVD and may also play a role in immunity, autoimmune diseases, type I and II diabetes, multiple sclerosis, cancer, depression and dementia.6, 8, 12 While plausible physiological mechanisms exist for these potential extra-skeletal effects, evidence from robust randomised controlled trials is limited and causality has not been established.4, 6 However, maintaining adequate vitamin D status (>50 nM/l) has been associated with decrease in allcause mortality in a recent large prospective cohort study.13

Vitamin D status is determined by a number of intrinsic, environmental and lifestyle factors. Biosynthesis of vitamin D from UVB sunlight (290–315 nm) is dependent on the correct latitude, and for countries above 40°N such as Ireland (52–55°N) this is negligible between October and March.3, 14 Cloud cover, time of day, altitude and air pollution can also affect production and give rise to regional variations in status.15 Factors including age, skin type, sunscreen use and clothing cover also determines dermal synthesis.16 Finally, the absorption and bioavailability of vitamin D is affected by malabsorption conditions (e.g. Crohn's/coeliac disease), medication, smoking and obesity.3, 17

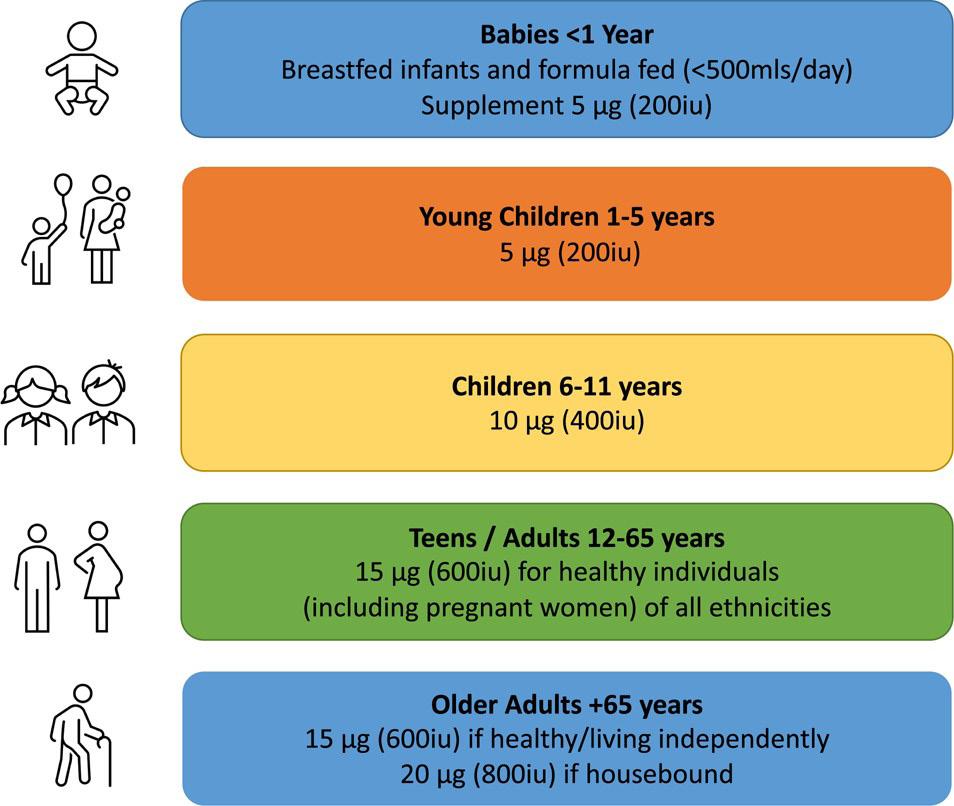

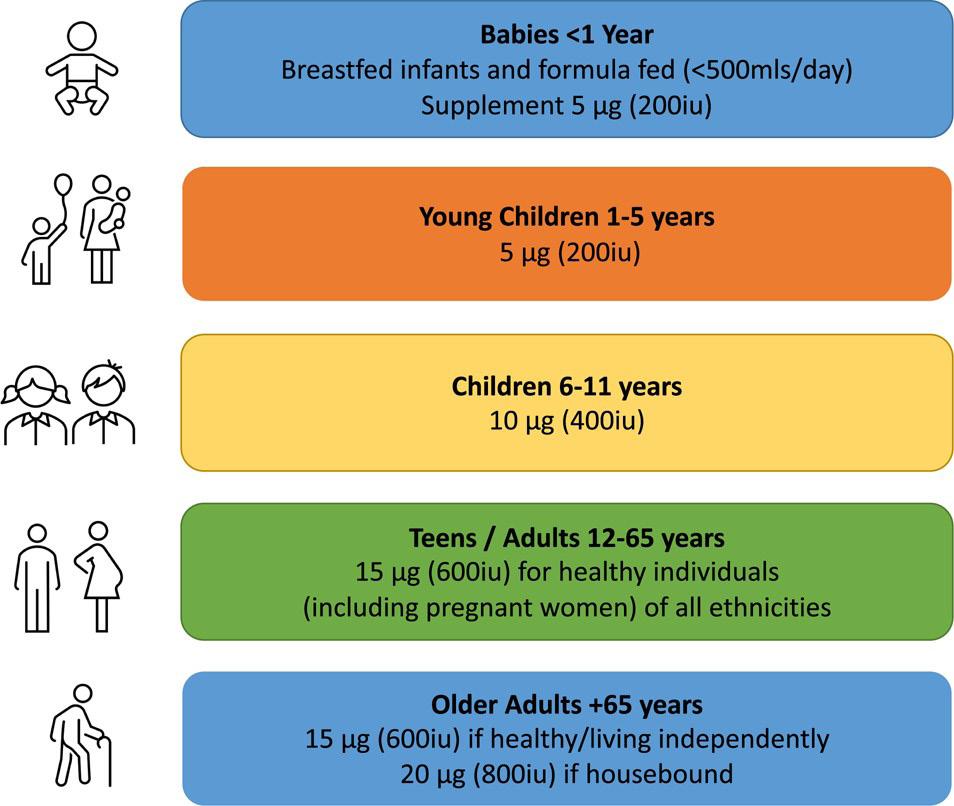

As a result of limited sun exposure, the Irish population is dependent on dietary sources of vitamin D, though intakes remain low, and most do not meet the RDA.18 The RDA as set by the Food Safety Authority of Ireland varies by age as shown in Figure 2.19–22 In addition, the proportion at risk of deficiency is rising due to demographic and

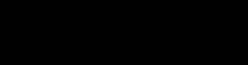

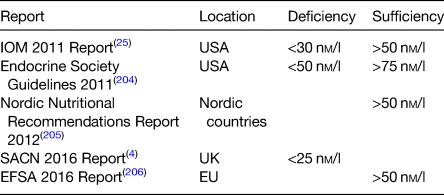

other changes.20 For example, the population is ageing, with the proportion over 65 years set to double by 205023 and there has also been an increase in those of ‘non-white’ ethnicity.24 Levels of overweight and obesity are also on the rise, increasing from 55 and 19 % in 2006 to 61 and 25 %, respectively, in 2016.23 While there are relatively few cases of rickets, the number reported has increased with twenty-three cases recently described in two Dublin hospitals.20 For these reasons, knowledge of both trends and current vitamin D status and intake is important in several subgroups of the population. There is no universal agreement on definitions of deficiency and sufficiency by professional bodies (Table 1). Vitamin D > 125 nM/l is suspected by the National Academy of Medicine as being harmful to health with potential negative effects on falls, depression and possibly other outcomes including cancer and all-cause mortality in some studies.25, 27 However, the National Academy of Medicine takes a precautionary approach that also factors in ethnic/genetic differences so as to maximise public health protection.27 Despite this, overt vitamin D toxicity causing hypercalcaemia is rare and usually occurs at levels above 375 nM/l.4, 28

Due to the limited half-life of the biologically active 1,25(OH)D (4–6 h) and its tight feedback control, vitamin D status is assessed by monitoring concentrations of

25(OH)D (half-life 3–4 weeks) which is under no feedback regulation.29 There are several types of vitamin D analytical techniques, with varying sensitivities and specifications.30 These include binding assays; RIA, chemiluminescence immunoassay, protein-binding assay, and bioanalytical assays such as HPLC and liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry (LC-MS/ MS). Binding assays are relatively quick and inexpensive but are subject to interference from other vitamin D metabolites and may overestimate 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentration.29 HPLC and LC-MS/MS allows for the quantification of a large number of samples, but require more technical skill.30 LC-MS/ MS is now considered the gold standard of vitamin D assessment and allows for the measurement of both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3.29 The vitamin D standardisation programme and vitamin D external quality assessment scheme were developed to improve the accuracy and repeatability of vitamin D assessments.31, 32 Vitamin D intake is typically assessed with FFQ that include 24-h re-calls and 3–7-d food diaries. Weighed food diaries are most commonly utilised in Irish national nutrition surveys and calculate vitamin D intake using nutrient composition databases.33

14 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

Helena Scully

To date, no study has comprehensively reviewed vitamin D research

Helena Scully, Kevin McCarroll, Martin Healy, James Bernard Walsh and Eamon Laird Mercers Institute for Research on Ageing, St James's Hospital, Dublin School of Medicine, Trinity College Dublin

Table 1. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D recommendations

15 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023 News

Figure 1. Vitamin D metabolism. 25(OH) D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; Ca, calcium; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; PTH, parathyroid hormone; SPF, sun protection factor

Vitamin D Intake

multivitamin containing vitamin D, 74 3 % were actually taking some form of supplementary vitamin D.61 Importantly, less supplement use in pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of low vitamin D status in Irish infants.49 Supplementation in Irish pregnant women was also the strongest predictor of 25(OH)D > 30 nM/l with Caucasian females more likely to supplement than those of other ethnicities.37

Children/adolescents

To date, no study has comprehensively reviewed vitamin D research with regards to vitamin D status and intakes on the island of Ireland. We aim to summarise the peer-reviewed studies and official reports published since 2010 or earlier for specific subgroups where no other data was available. For the purpose of this review, we defined deficiency as <30 nM/l and excess as >125 nM/l unless otherwise stated.25

Vitamin D status and intake by population categories

Pregnancy and fertility

The largest Irish study (n 1768) in pregnant women found a prevalence of deficiency of 17 %(Reference Kiely, Zhang and Kinsella34), which was similar to other large studies where it ranged between 15 and 17 %.35, 36 In other studies, it varied between 13 and 65 % but sample sizes were small and were not likely to be representative.37, 40 In general, deficiency was less prevalent in early pregnancy (13–29 %)34, 36, 38, 41, 47 with rates increasing with gestation in most studies.41, 42, 45,47 A high proportion of mothers (25–65 %) were also found to be deficient at

delivery.39, 40 As expected, a seasonal variation in vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy was found,34, 38, 43, 45, 48, 50 with the lowest prevalence of 3–7 % detected in summer/autumn.34, 38

The prevalence of levels <50 nM/l in the largest studies were between 42 and 44 %(Reference Kiely, Zhang and Kinsella34–Reference Hemmingway, Kenny and Malvisi36), while in smaller studies variance was pronounced (44–91 %)(Reference O'Callaghan, Hennessy and Hull38,Reference Onwuneme, Martin and McCarthy40) . A seasonal effect was also evident, with prevalence generally higher in winter v. summer(Reference Kiely, Zhang and Kinsella34,Reference O'Callaghan, Hennessy and Hull38,Reference

O'Brien, O'Sullivan and Kilbane45,Reference Holmes, Barnes and Alexander48) . Prevalence of levels below <50 nM/l is similar to some pregnancy studies in Northern Europe where it affected approximately 50 % in the UK(Reference Gale, Robinson and Harvey51) and Belgium(Reference Vandevijvere, Amsalkhir and Van Oyen52). Only one Irish study (n 138) looked at men and women

undergoing fertility treatments and found that one out of five was deficient(Reference Neville, Martyn and Kilbane53).

Dietary and supplement intakes in pregnancy

Dietary intakes in pregnant women ranged between 1 9 and 10 7 μg/d,46, 54 with 80–99 % not meeting the recommendations.54, 56 By comparison, in the UK, 98–100 % were found not to meeting the advised intake of 10 μg/d.57

In Ireland the RDA in pregnancy is no different from the general adult population at 15 μg/d.22 However, evidence suggests that pregnant women require 20 μg/d to meet sufficiency (>50 nM/l)58 with 10–15 μg/d advised by a European consortium.59 In Finland, the 2003 food fortification of liquid milk resulted in a significant increase in vitamin D intakes in pregnant women,60 and as such should be considered as a public health measure to improve vitamin D status in Ireland.

Nearly 40 % of pregnant Irish women reported taking a specific vitamin D supplement in a Dublin study (n 175) in 2016, though the sample was from a confined area.61 However, when including a

In the largest study to date (n 5524), 15 % of children (5–19 years) were deficient,62 while the second largest (n 1226) found a deficiency rate of 23 %,63 though both were conducted in the Dublin area. In most studies deficiency prevalence varied between 5 and 23 %.62, 68 The most recent nationally representative study that measured vitamin D levels in teenagers (aged 13-18 years) found that 21.7% were deficient though sample size was small (n=246).69 The highest prevalence of deficiency (63–68 %) was reported in adolescents (aged 12 or 15 years) in Northern Ireland.70 However, vitamin D was assessed over 20 years ago, was not checked in the months of July or August and the study population was derived after stratified sampling so may not be more broadly representative. Furthermore, the results are discordant with other studies. As expected, the prevalence of deficiency was lower in the summer66, 71, 72 and higher in winter when it affected 18–30 % of teens,71, 72 and 26 % of children aged 1–17.63 In general, female children also had lower vitamin D status,63, 65, 70, 73, 74 but not in all studies.64

Notably, there was a ‘U-shaped’ relationship between deficiency prevalence and age, being lower in younger children (1–12 years) and greatest in adolescents and older children (>12 years). 62, 63, 65 For example, a recent large study found a greater prevalence of deficiency in over v. under 12s (24 v. 16 %).63 Lower rates of deficiency (2 %) have been found in toddlers (aged 2 years) and children under 5 (13 %),64, 66 with higher 25(OH)D also reported in those under v. over 4 years (61 0 v. 46 1 nM/l, P < 0 001).65 Similarly, in a recent large study, deficiency was lower

16 SEPTEMBER 2023 • HPN | HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE

Figure 2. Irish vitamin D supplement recommendations by age group

(5 %) in toddlers (1–4 years) but much higher (15 4 %) in older children (5–19 years).62 Better vitamin D status in younger children (<5 years) may relate to Ireland's infant supplementation policy.75 Conversely, lower rates of supplements and fortified food consumption has also been found in Irish teens compared to younger children.76 One study also reported that older teens (15–18 years) had lower mean 25(OH)D and were more likely to be deficient than younger teens (13–15 years).69 Greater screen time/sedentary behaviour and increased obesity rates in this age group may be important factors.77, 79 Socioeconomic status may also explain some of this variation as it has been associated with a higher prevalence of deficiency in Irish children.63 Overall, reports are broadly consistent with findings in northern European countries (47–69°N).80, 83 and in the UK 19 % of 11–18-year-olds were deficient, compared to just 2 % of those aged 4–10.84

Despite in general, less deficiency in younger children, this was not apparent for those aged <1 year. For example, deficiency in new-borns was high ranging from

34 to 63 % (based on cord blood samples),35, 39, 42, 49 while in preterm infants 64 % were deficient at delivery.40

Overall, approximately half of children aged 1–17 years had levels <50 nM/l,62, 63, 65, 68, 69 with a seasonal variation identified,63, 66, 73 similar to findings in the European Union (EU).75, 80, 85 Similar to deficiency, prevalence was lower in younger children (1–5 years), at 21–39 %.62, 64, 66 and higher in teens at 36–89 % as in UK studies.81 The prevalence of 25(OH)D < 50 nM/l in new-born cord blood was particularly high (between 80 and 92 %),35, 39, 42, 49 and similar (79–92 %) in preterm and term infants.35, 40, 42, 44, 49

Dietary and supplement intakes in children

The first nationally representative dietary survey in 2010/2011 in Irish children aged 12–59 months found that 70–84 % had intakes <5 μg/d (mean of 3 2 μg/d).86 In a small study (n 97) of 5-year-olds in 2019, intake remained low with just 6 2 % having consuming above 5 μg/d.64 Recent nationally representative surveys of older children (5–12 years) and teens (13–17 years) found the majority (94 %) had intakes <10 μg/d,

with little improvement between 2003/2004 and 2017/2018.78, 87, 88 In fact, comparing surveys, intakes had improved only a little, from 2 7 to 3 7 μg/d for teens and from 2 3 to 4 2 μg/d for children.87,89–91 Similarly, in a recent nationally representative study of teenagers (aged 13-18).69

In Irish infants, milk/formula comprised of 29 % of total intakes,86 similar to that in UK children aged 12–18 months.92 Milk/products were also the greatest source of vitamin D in children <4 years in Ireland followed by meat and its products as found in the UK.86, 92 However, in Irish children aged 5–12 years, fortified cereals were the largest contributor, followed by meat and then milk products87 as also identified in Belgium and the UK.81, 93 Meat and its products also account for the primary source of vitamin D in Irish children over 13,78,94 despite its relatively low content. This is also reflected in the UK, where it comprised of 35 % of dietary vitamin D intake.4

Children aged 1–5 years in Ireland are recommended to receive 5 μg/d, supplementing if necessary, with older children (aged 6-11

years) advised to consume 10 μg/d.20, 22 Overall, supplements are an important contributor to vitamin D status in children and adolescents in Ireland,65, 95 as found elsewhere in Europe.96, 98 The most recent national dietary survey (2017/2018) of Irish children aged 5–12 years indicated that just 10 % consume a vitamin D supplement87 which compares to 17 % in a representative sample (aged 1–4 years).95 Supplement use has also been found to decrease with age, with 21 % of 5–8, 16 % of 9–12 and 15 % of 13–17-year-olds consuming a vitamin D containing supplement.65, 66, 76, 95 Similar findings have been reported in the UK, with higher supplementation rates in younger children (14–16 %) compared to teens (5–6 %.57 Indeed, since the introduction of an infant supplementation policy in Ireland, initiation of a 5 μg/d supplement from birth increased to 92 %, with 30 % of parents compliant during the first year.99 In one study, supplement use was reported in 23 % of Irish children (aged 1–17) attending hospital though this could be due to underlying medical reasons.65

References available on request

17 HOSPITALPROFESSIONALNEWS.IE | HPN • SEPTEMBER 2023

Dermatology

Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis

Written by Alan D. Irvine, Thishi Surendranathan, Liz Hennessy, Ivana Rajkovic, Annette

Dearbhla Coughlan, Sean Conlon, Richard Hudson

Alan Irvine

of care for paediatric AD in Europe. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no real-world evidence (RWE) study focusing on an Irish population of children and adolescents with moderateto-severe AD. The RWE study reported here is the first of its kind to systematically capture data on clinical characteristics, secondary care HCRU, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) associated with treatment of moderate-to-severe AD, in children and adolescents in a single centre in Ireland.

Patients and Methods

Study design

Durkan,

primary care in Dublin, Ireland and secondary care nationally. Data collection was from October 2020 to June 2021.

It is estimated that in the Ireland 14.3% of children 13–14 years of age ever experience the inflammatory skin disorder atopic dermatitis (AD).1 AD has a profound impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients and their relatives, affecting multiple aspects of psychological, social and physical functioning.2-7 Therapeutic guidelines recommend that firstline treatment aims to control flare with local anti-inflammatory agents, including topical corticosteroids (TCS).8 For more severe AD cases, ultraviolet light and systemic immunosuppressants are suggested.8

Recognition of immunological disease mechanisms in AD has led more recently to the identification of different therapeutic targets and development of novel therapies. Regulatory approval has been gained for several of these for moderate-to-severe AD, including biologic therapies targeting specific immune pathways.9 Some biologics are now licensed for use in adolescents and/or children. However, the treatment of childhood AD remains challenging since there can be inadequate response to available therapies, and the more advanced immunological therapies are limited to late line use and are costly. This means determining when to prescribe an advanced therapy and which therapy to use is not necessarily straightforward.10

AD presents a considerable socioeconomic burden. Healthcare resource utilisation (HCRU) increases with disease severity,11 and is significantly higher after systemic therapy initiation.12 While the Irish dermatology programme ensures patients are appropriately seen, assessed, and treated,13 limited data are available describing the HCRU associated with current standard

This was a retrospective, noninterventional, single-centre chart review of 31 patients with AD aged 6–17, conducted in the public healthcare service at Ireland's largest paediatric hospital, Children's Health Ireland, at Crumlin where around 90% of all Irish children treated with systemic therapies for AD are managed. Referrals are made from

Supplementary Figure 1 Study design schematic illustrating the retrospective observational period

Patients meeting the eligibility criteria were selected consecutively, starting with the most recently consulting patient, and working backwards until the patient target was reached (Supporting Information: Figure 1). Data were abstracted from medical records, starting from the first secondary care appointment post 1 January 2014 when patients were 6–17 years of age, up until the most recent date/ event available when patients were also under 18 years of age. A minimum of 12 months of data was abstracted for each patient from their first secondary care appointment after January 2014. Anonymised data were collected onto a standardised, purposedesigned electronic Case Report Form (eCRF) by hospital research staff.

Supplementary Figure 1 Study design schematic illustrating the retrospective observational period

Supplementary Figure 1 Study design schematic illustrating the retrospective observational period

BASELINE

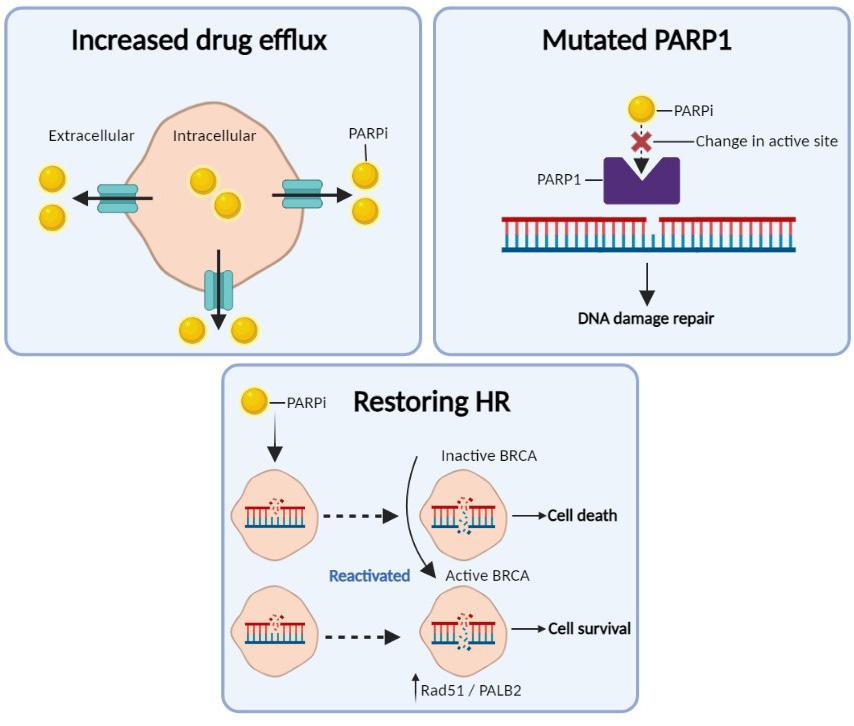

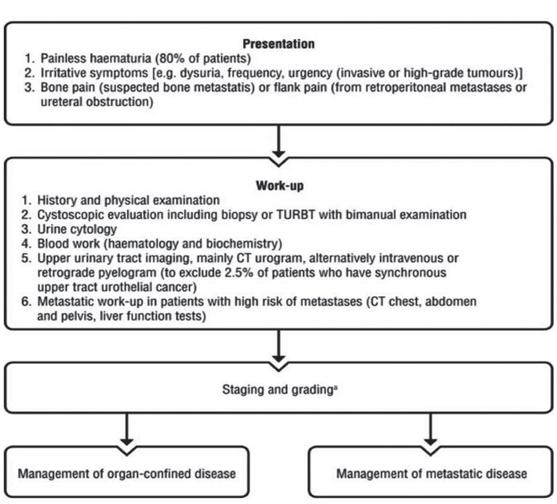

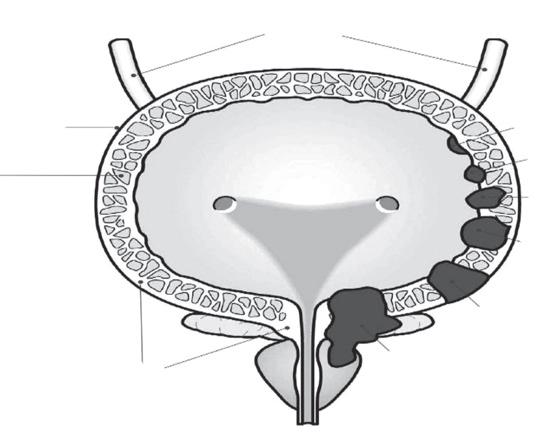

Date of pa�ent ’s first secondary care appointment occurring post January 1st 2014a