The Inya Institute Quarterly Newsletter

Summer 2023

Asif the on-going devastation inflicted by the troops of the State Administration Council (SAC) through the torching of villages and bombing of communities by fighter jets across the country was not devastating enough, powerful Cyclone Mocha hit most of Rakhine State and the southern part of Chin State on May 9, 2023. The material damage caused was catastrophic. Both damage assessment and delivery of humanitarian relief by international organizations have been deliberately hampered by SAC. Two months into the aftermath, recovery is proceeding at a very slow pace.

On our side, there are, fortunately, happy news! Join us in congratulating Dr. Kimberly Roberts, Christian Gilberti, and Peter Alexander on their fellowships! Kimberly, our Summer 2023 Research and Mentoring Fellow, is currently leading the workshop series on Myanmar’s borderlands with 23 participants located in various parts of Myanmar and neighboring countries. The participants are developing group research proposals on topics of their choosing under Kimberly’s guidance. The wide range of topics covering education, humanitarian relief, illegal/legal migration, and legal protection of refugees, promises to offer interesting insights into Myanmar’s borderlands at this crucial time in Myanmar’s multilayered crisis. For more information about Kimberly, our 23 participants, and the topics chosen, please read pp. 12–15!

www.inyainstitute.org

Our two 2023 CAORC-INYA Short-term Fellows, Christian and Peter will conduct fieldwork in India and the U.K. respectively. The former will focus on Burmese students travelling to India for education in the early colonial period, while the latter is currently in London to undertake archival research focusing on the role of the Shwedagon Pagoda in the rapidly changing social landscape of colonial Rangoon at the end of the 19th century. More details on their respective research topics on p. 11.

Here, in Yangon, our offer of online educational opportunities is in full swing. The first round of our Effective Learning Strategies training course is being offered online and free of charge by Pyae Phyoe Myint, our Education and Training Junior Manager, during the first week of July. Meanwhile, our 2023 Languages of Myanmar course series is being led by Hsaiwan Hleng, Mwe Seng Hleng, and Sai Aung Naing Oo for the Shan language course; by Seng Jar, Lamu Htu Nan, and Merry Nan Htoi for the Kachin language course; and by Saw Eddison Thein for the Karen language course. Altogether 25 language learners (14 Myanmar and 11 International participants) are joining the classes. We wish both teachers and learners all the best!

In this issue Ongoing Project 3 “Documenting Traditional Teak Farmhouses of Myanmar” by Jeff Allen Findings 5 ‘Barriers for Job-seeking Migrant Youth in Yangon” by Kyaw Tun Aung Collaborative Output 9 Shan Monastic Architecture: Marvelling at 3D Renderings of the Punlong Monastery Upcoming Opportunity at Inya 10 New Fellows at Inya 11 Ongoing Workshop Series at Inya 12 New Books on Myanmar 16

The Inya Institute team in Yangon

Address in Myanmar: 50 B-1 Thirimingala Street (2)

8th Ward

Kamayut Township

Yangon, Myanmar

+95(0)17537884

Address in the U.S.: c/o Center for Burma Studies

101 Pottenger House

520 College View Court

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115 USA +1 815-753-0512

Director of Publication: Dr. François Tainturier

Layout and Formatting: Aung Kyaw Phyo

Administrative Assistant: Chai Mana

U.S. Liaison Officer: Carmin Berchiolly

Contact us: contact@inyainstitute.org

Visit us on Facebook: facebook.com/inyainstitute.org

Library: It currently holds a little more than 900 titles and offers free access to scholarly works on Myanmar Studies published overseas that are not readily available in the country. It also has original works published on neighboring Southeast Asian countries and textbooks on various fields of social sciences and humanities. Optic fiber wifi connection is also provided without any charge.

Library digital catalog: Access here.

Working hours: 9am-5pm (Mon-Fri)

Digital archive: It features objects, manuscripts, books, paintings, and photographs identified, preserved, and digitized during research projects undertaken by the institute throughout Myanmar and its diverse states and regions. The collections featured here reflect the country’s religious, cultural, and ethnic diversity and the various time periods covered by the institute’s projects developed in collaboration with local partners.

Digital archive: Access here

The Inya Institute is a member center of the Council of American Research Centers (CAORC). It is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act (2020-2024).

Academic Board

Maxime Boutry, Centre Asie du Sud-Est, Paris

Jane Ferguson, Australian National University

Lilian Handlin, Harvard University

Bod Hudson, Sydney University

Mathias Jenny, Chiang Mai University

Ni Ni Khet, University Paris 1-Sorbonne

Alexey Kirichenko, Moscow State University

Christian Lammerts, Rutgers University

Mandy Sadan, University of Warwick

San San Hnin Tun, INALCO, Paris

Juliane Schober, Arizona State University

Nicola Tannebaum, Lehigh University (retd)

Alicia Turner, York University, Toronto

U Thaw Kaung, Yangon Universities’ Central Library (retd)

Board of Directors

President: Catherine Raymond (Northern Illinois University)

Treasurer: Alicia Turner (York University, Toronto)

Secretary: François Tainturier

Jane Ferguson (Australian National University)

Lilian Handlin (Harvard University)

Nicola Tannenbaum (Lehigh University)(retd)

Thamora Fishel (Cornell University)

Photo credits: ESA

Ongoing Project

Documenting Traditional Teak Farmhouses of Myanmar

Jeff Allen, Southeast Asia Program Director, World Monuments Fund, offers an overview of an ongoing preservation program focusing on the documentation of traditional teak farmhouses. The present situation in Sagaing Region has compelled the team to shift its focus to more accessible parts of the country. In collaboration with the Inya Institute and local colleagues, the project’s objective is to preserve age-old building techniques and structures at a time when village communities have, for good reason, other priorities and craft knowledge and built structures are under extremely severe threat.

Elevated above ground on a sturdy wood structure, with wood and split bamboo walls and a thatched or corrugated metal roof, the farmhouse building type embodies a centuries-long building culture in Myanmar. Such farmhouses once abounded in Burmese villages throughout the central plains of Myanmar and around the Irrawaddy River delta.

Under successive kingdoms, dwellings in Myanmar were subject to sumptuary laws ensuring that building height, materials, and construction techniques were consistent with a person’s status in society. The end of monarchy and the colonial period saw the end of sumptuary restrictions on building, allowing for grander houses to be built using teak, a material that had once been restricted to monastic architecture alone. Drawing on a tradition of wood joinery and carving, farmhouses were built on sturdy posts, supporting a broad platform and a sparsely furnished main level. A covered staircase gave access from below, while the space beneath the house provided shelter for livestock and a place to store agricultural tools. Roofs were built of thatch, which always represented a fire risk, and were increasingly replaced with corrugated zinc after the nineteenth century.

Today, even as agriculture continues to underpin Myanmar’s economy, many farmhouse owners are opting to replace their homes with modern buildings that allow for a higher level of convenience and comfort. Rural Burmese populations are abandoning wood for cement slabs, brick walls, and aluminumroofed dwellings.

An influx of new building technologies and cheap materials previously inaccessible to the masses, partly connected to reduced tariffs amongst more industrialized ASEAN members and the People’s Republic of China, is changing the built Burmese environment. Agro-teak restrictions have further restricted legal teak sales and exports and, at the same time, enriched a corrupt, illegal trade. Today, teak building materials for new construction, repair, and expansion are financially out of reach for farmhouse owners. In response, there is a growing interest in salvaging historic teak architecture for reuse. Dismantling for resale is an activity that is aggressively destroying not only farmhouses but also Myanmar’s multicultural identity through the erasure of its varied forms of ethnic expression and the disappearance of entire rural cultural landscapes. Finally, the COVID pandemic and the 2021 military coup have released other threats through a collapse of the rule of law, where in parts of the country, demolitions take place singularly without permission and whole villages are burned to counter an unrelenting insurgency.

The destruction of Myanmar’s wooden farmhouses is part of a more extensive rapid socio-economic transformation that undermines the survival of traditional architectural forms and building craft. But while these changes are plainly visible, more research needs to occur on the mechanisms that drive them. Also documentation of the disappearing farmhouses is very sparse in libraries and archives. It is crucial that this architectural typology, its ethnic variations, and its usage, often ignored and undervalued, be documented before it is too late.

3

Figure 1: Ma Shwe Yi Win and baby Aung Paung Kar outside her family home, In Bin Thar Village, Lewe;

Photo credits: Tim Webster for WMF (2017)

World Monuments Fund’s relationship with Myanmar began in 2012 in identifying project opportunities for cultural heritage preservation. With support from the U.S. Government’s Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation and other donors, WMF implemented conservation activities through an enriched capacity-building program at Shwe-nandaw Kyaung in Mandalay. Work continued for nearly six years until the military coup extinguished donor support and Myanmar Government cooperation. At the early twentieth-century First Baptist Church of Mawlamyine, WMF assembled a team of skilled specialists in Myanmar and from abroad to collaborate on documentation, condition assessments, conservation planning, and execution of remedial work. The project utilized the First Baptist Church’s asbestos roof replacement as an educational opportunity to introduce a cadre of local tradespeople, students, and officials to safety, cultural and architectural heritage conservation methods.

tation strategy through three survey field campaigns in Mandalay Division and Shan State by conducting inconspicuous inventories and avoiding intrusive documentation activities. To reduce anxieties and avoid attention, young women form our field survey teams, which stimulate close relationships with the female heads of houses. Contrary to some of our early concerns, thus far, communities have been not only welcoming to our interests but incredibly supportive and interested. Despite the complications of Myanmar’s current instability situation and the hardship it has brought, its people remain true to their rooted friendliness and hospitable nature. These initial contacts establish fundamental photo and drawing documentation and, notably, relationships for expanded and more comprehensive social and lifestyle documentation opportunities when circumstances permit. Based on a flexible methodology and emphasis on capacity building in young professionals, the EWAP grant

In 2020, World Monuments Fund placed Burmese Teak Farmhouses on its biannual WMF Watch list. Since the program’s inception, the Watch has been a proven tool for raising awareness about heritage places needing protection and galvanizing action and support for their preservation. Heritage sites can be nominated by any individual or organization, ensuring that the Watch remains a powerful platform for amplifying the voices of local community members and residents.

Watch-listing Burmese Teak Farmhouses brought attention to the plight of Myanmar’s unique domestic vernacular architecture and the support of the ‘Endangered Wooden Architecture Programme’ (EWAP). EWAP is a grant-giving program that offers small and large grants for documenting endangered wooden architecture. The program is hosted by Oxford Brookes University in the U.K. and was established in 2021 with funding from Arcadia, a charitable fund. Through EWAP, the Burmese Teak Farmhouses documentation project has been energized, not only through its funding but by the institution’s programmatic principles and organizational strengths that are shaping WMF’s work, not just during this EWAP grant cycle, but for our continuation in the years to come.

The state of emergency in parts of Myanmar has restricted access to some of our initial farmhouse priorities, so flexibility is critical. To date, WMF has established an effective implemen-

activities serve well as a platform for later developing 3D models and other rich documentation incorporating equipment and technologies that remain limited in Myanmar.

Our shared investment with EWAP is toward building the capacity of young Burmese and other Southeast Asia professionals. Training young architects, archaeologists, and engineers and involving young residents through a hands-on documentation process means recording vanishing architectural forms, building appreciation, and, hopefully, future advocacy for its preservation. Young Burmese have proven they are not indifferent to their surroundings and today inspire older generations acclimatized to accept situations as imposed upon them. Despite the challenges of the moment, there is a unique opportunity to build on this momentum with projects like this.

Ultimately, the documentation of the various typologies of teak farmhouses we have identified will contribute to the understanding of Myanmar’s rich vernacular architectural legacy and provide the foundation for future research on its evolution and regional and ethnic variations. This will immediately benefit researchers and architectural historians and, in some cases, can lay the groundwork for future cultural tourism opportunities that generate income and benefit local residents and farmhouse owners while encouraging and funding the maintenance and continued preservation of these architectural masterpieces.

4

Figure 2: U Kaung Aye outside his home; Kywe Chin Village, north of Nay Pyi Taw; Photo credits: Tim Webster for WMF (2017)

Figure 3: Rural teak farmhouse; Kywe Chin Village, north of Nay Pyi Taw; Photo credits: Tim Webster for WMF (2017)

Findings

Barriers for Job-Seeking Migrant Youth in Yangon

As part of his six-month internship program at the institute, Kyaw Tun Aung conducted a small-scale survey with the collaboration of Ni Ni Htwe and under the methodological guidance of Pyai Nyein Kyaw. The survey addresses the barriers that young migrants to Yangon face when seeking jobs. A native from Debayin, Sagaing Region, Ko Kyaw knows first-hand how difficult the situation has been for young economic migrants, especially since the military coup of February 2021. He offers us here the survey findings.

This research explores the challenges faced by young migrants from rural areas in Yangon, Myanmar, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and political upheaval. The study conducted in this report utilized both quantitative and qualitative methods, including a combination of a survey, interviews, and desk reviews. Results from the survey showed that the primary reasons for migration to Yangon were a lack of job opportunities and low wages in rural areas, as well as a search for better education. However, new findings suggest that the political instability in rural areas following the military coup is accelerating the process. During the pandemic, young people from urban areas lost their jobs due to the closure of most companies and industries to prevent the spread of the virus in Myanmar. After the pandemic, they came to Yangon to find a job. Over the past two years, many young people from rural areas moved to Yangon due to the political instability. The report highlights the determination and resilience of these young people in their

pursuit of better opportunities despite significant obstacles. It sheds light on important issues related to labor rights and migration in Myanmar and provides valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders addressing these issues.

The people of Myanmar have, for many decades, chosen to migrate to overseas countries in order to make a better living and flee armed conflicts in ethnic areas. According to the 2014 census in Myanmar, there were more than two million workers employed abroad that year. This research was primarily conducted to gain insight into the obstacles that young people encounter when seeking employment in Yangon and to identify strategies for overcoming these challenges. The report begins with an overview of the context in which youth migration occurs in Myanmar, highlighting the economic and political factors that drive migration from rural areas to urban centers like Yangon. It then provides a detailed description of the research methods used in the study, including information on sample size,

data collection techniques, and analysis procedures. The findings include an analysis of the primary reasons for migration among young people, an exploration of the barriers they face when seeking employment, and a discussion of their strategies for overcoming these obstacles. The report concludes with a set of recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders. These recommendations are designed to help address some of the key challenges identified in the study and to promote more inclusive policies and practices that support youth migrants’ access to decent work opportunities.

Methodology

The study utilized both quantitative and qualitative methods through a combination of surveys, interviews, and desk reviews. The survey was designed to collect data on the primary reasons for migration among young people, as well as the barriers they face when seeking employment in Yangon. The survey questions were mainly closedtype questions, with some open-ended questions included to gain more insight from respondents. A snowball sampling method was used to recruit 49 survey respondents. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 11 Key Informants who are members of Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) focusing on labor rights and migration. Follow-up questions were used to ask the interviewees about their experiences and perspectives on youth migration and employment in Yangon. Desk review included news coverage and reports by UN agencies and other organizations. It is important to note that this study has some limi-

5

Figure 1: Reasons for migrating to Yangon

tations. For example, the sample size for both surveys and interviews was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Additionally, due to COVID-19 restrictions at the time of data collection, all surveys were conducted online which may have excluded some potential participants who did not have access to technology or internet connectivity.

Findings and Results

The findings and results of this report reveal several key insights into the challenges faced by youth migrants in Yangon. The survey results confirm many commonly acknowledged reasons for explaining migration of youth to Yangon, including lack of job opportunities, low wages in rural areas, and a search for better education in Yangon (Fig. 1). Two-thirds of survey respondents reached Yangon before the COVID-19 pandemic; most migrants interviewed moved to Yangon more than two years before the pandemic. Over two-thirds of survey respondents moved to Yangon

in order to get a higher wage and also because of a lack of job opportunities in their native places and low wages there. The second reason for migrating to Yangon is for education purposes as there are many public and private universities in Yangon. However, the interviews also highlight that security issues due to the military takeover and the subsequent deteriorating political instability in rural areas are now playing a significant role in the migration.

From the survey results, income of young migrants’ families comes from agriculture, trading, and other sources such as family businesses, government staff, pensions, and company staff (Fig. 2). However, family income is usually not enough to meet the family’s basic needs. As a result, it is necessary for migrant workers in Yangon to support their families back home and transfer a portion of their salary. The study found that nearly two-thirds of migrant workers send money monthly to their family— this rate, however, may not be representative of all internal migrant workers.

When young migrants from rural areas seek a job in Yangon, Facebook is the main platform where to find a job as indicated by nearly half of the respondents. The second and third avenues for job-searching migrants are job portal websites and networks among friends and acquaintances (Fig. 3). One interviewee mentioned the following about job seeking,

“Seeking a job is inquiring [for myself] to get the information from the factory and apply to [the job].”

After the COVID-19 pandemic and in this post-coup period, job opportunities in Yangon are fewer and fewer. a situation caused by the political instability and subsequent economic crisis.

Youth migrants face significant barriers when seeking employment in Yangon. Discrimination based on ethnicity or place of origin is one such barrier. Many employers prefer candidates from urban areas or those with existing connections to the em-

6

Figure 2: Main income source of migrants’ family

Figure 3: Sources used by job-seeking migrants

ployers’ social networks. Lack of access to information about job opportunities is another significant barrier faced by youth migrants. They often rely on personal networks for job leads rather than formal channels such as online job boards or recruitment agencies.

Limited social networks also pose a challenge for youth migrants seeking employment in Yangon. Many young people who move from rural areas may not have established social networks in urban centers like Yangon, which can make it difficult for them to find work or access support services.

Despite these challenges, youth migrants demonstrate resilience and determination in their pursuit of better opportunities. They use a variety of strategies to overcome obstacles, including relying on personal networks for job leads and seeking out training programs or apprenticeships.

Many respondents look for jobs in companies and non-profit organizations in Yangon (Fig. 4). After the 2021 coup, many government of -

ficials, as well as students, teachers, and doctors in state hospitals, were involved in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). The political climate worsened and, as a result, most young people today are reluctant to apply for jobs in the government sector. Young migrants have no choice but to choose jobs in other sectors, concentrating on securing any type of job to survive and meet their basic needs in this current crisis.

Many young migrants also engage in informal work, such as street vending or day labor, to make ends meet while they search for more stable employment . Informal jobs can be risky and unstable, but they provide a source of income for many young people who may not have other options.

The survey found that nearly half of the respondents are not familiar with the environment and transportation system of Yangon. This proves to be the largest difficulty. The second largest difficulty is the job seekers’

lack of digital proficiency, which may be required for certain jobs. One of the survey respondents said that:

“I [do not have] a degree, job experience and [cannot] use mobile phones effectively to apply for jobs. Therefore, I could not apply for [any of them].”

The third largest difficulty is the difference between rural or urban lifestyles and the difference of the pace of life in the village as opposed to that of the city.

According to the results of the survey, the main credentials required from employers is work experience (82% of them shared this view). Other common requirements for job-seekers are a bachelor’s degree, skills in computer literacy, and language proficiency. It means that young migrants usually must complete a degree and have computer and language proficiency to apply for a job in Yangon. In the job application

7

Figure 4: Employment sector chosen by young migrants

process, employers ask workers about their job experience and education. One of the interviewees said:

“The factory gave me a job but I could not get much money because I did not pass the examination in high school compared to my friend who passed it and is more clever than me. Therefore, she got a better job as an accountant in the factory. I got a difficult job in the cutting position. And I work harder in this workplace than her. But the wage difference is about forty or fifty thousand kyats. It also varies between positions and depending on the education background.”

Therefore, policymakers and stakeholders can help address these challenges by suggesting investment in education and skills training programs for youth migrants. These programs can help young people develop the skills and knowledge needed to succeed on the job market and increase their chances of finding stable employment. Promoting inclusive hiring practices among employers is another important strategy for tackling these barriers.

Discussion and Conclusion

The study highlights the significant challenges faced by young migrants from rural areas when seeking employment in urban centers like Yangon.

Youth from rural areas struggle to apply for and secure a job: most lack computer literacy, work experience, and familiarity with the Internet.

In the job-seeking process, there are many discriminatory practices that exist among employers. These challenges include discrimination based on ethnicity or place of origin, limited access to information about job opportunities, and a lack of established social networks. Therefore, young migrants from rural areas have less opportunities when compared with young people who have lived all their life in cities.

A significant finding from the survey can be observed: zero percent of the total respondents answered that they would apply to government servant positions when asked what type of job they are looking for. Due to the impact of the military coup, there is a decrease in the public’s trust in the public sector now under the control of the military administration.

In the future, policymakers should place emphasis on local job opportunities in rural areas and promote youth participation in community development—as a result of these opportunities, young people will both acquire new skills through experiential learning and gain job opportunities. Policymakers need to consider both the impact of the current political upheaval on young migrants from rural areas

and the ways to support youth communities in the post-conflict period.

Another important recommendation is the need to promote inclusive hiring practices among employers. This could involve providing incentives for employers who hire young migrants or implementing policies that require companies to demonstrate their commitment to diversity and inclusion. Employers could also be encouraged to provide mentorship or apprenticeship opportunities for young people, which would help them build their professional networks and gain valuable work experience.

However, it is important to recognize the resilience and determination demonstrated by young migrants in pursuing better opportunities despite significant obstacles. By supporting these young people through targeted policies and programs that address their unique needs, we can help promote more inclusive economic growth that benefits all members of society.

In conclusion, this study provides insights into the challenges faced by young migrants from rural areas when seeking employment in urban centers like Yangon. By implementing policies and practices that support young migrants’ access to decent work opportunities, we can help build a more equitable and sustainable economy that benefits the community.

8

Figure 5: Major difficulties in searching for a job in Yangon

Collaborative Output

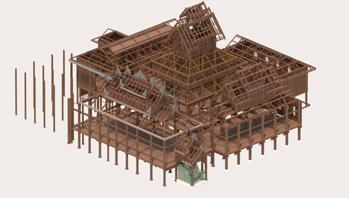

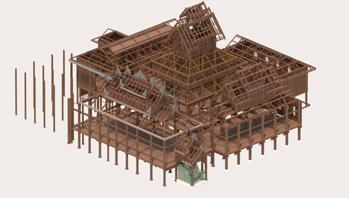

Shan Monastic Architecture: Marvelling at 3D Renderings of the Punlong Monastery

Thank you to Patcharapong Kulkanchanachewin, our

Based on sketches and measurements made in the field in 2018 by students of Technological University (Mandalay), Yadanapon University, and Silpakorn University under the guidance of their respective professors during a research developed by the institute, the 3D renderings are a very valuable addition to research on the village and monastery of Punlong.

Very recently, the area has seen armed conflict between troops from the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and those of the Restoration Council of the Shan State (RCSS). It is not currently known whether the armed struggle has had any impact on the village community and its built environment. But it is reasonable to assume that the monastery would have been spared in this armed struggle. Still, our documentation and Patcharapong’s 3D renderings are now available and will serve as a valuable record, should any fateful developments occur in Punlong.

9

3D renderings of the Ponlong Monastery in Kyaukme Township, Shan State.

colleague at the Department of Architecture, Silpakorn University, Bangkok, for producing these magnificent 3D renderings of the Punlong Monastery, Kyaukme Township, Shan State!

Upcoming Opportunity at Inya

CAORC - INYA & CKS Faculty Development Seminar

Between Political and Climate Change in Southeast Asia

To support community colleges and minority-serving institutions, CAORC offers fully-funded overseas seminars that help faculty and administrators gain the requisite first-hand experience needed to improve courses connecting international issues with domestic concerns, thereby underscoring global interconnections through the creation of new and innovative curricular and teaching materials.

The COVID-19 pandemic and current Myanmar’s political crisis have severely tested the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s credibility and legitimacy in projecting itself as a force for good for its people. In addition to these political challenges, the devastating effects of climate change across the region are impacting livelihoods, food security, migration, natural resources, and the environment. In this context, to what extent can Cambodia’s and Myanmar’s civil society mobilize against these challenges, and by what means? How do the outcomes resulting from these responses differ between Cambodia and Myanmar?

Featuring lectures, meetings with media professionals, civil society and environmental organizations, and site visits, this two-week faculty development seminar held in Cambodia will offer participants a unique opportunity to gain knowledge and experience about the two countries. It will also leave time to explore Cambodia’s history, culture, and natural habitats with visits to ancient temples and the city of Angkor, the Tonle Sap Lake, museums and sites in Cambodia’s capital city of Phnom Penh, and more. The FDS program is jointly organized by CAORC, the Center for Khmer Studies (Cambodia), and the Inya Institute (Myanmar).

Seminar Dates: May 15 - May 30, 2024

Eligibility

Location: Cambodia

The program is open to full-time or part-time faculty and administrators at U.S. community colleges or minority-serving institutions. The program is open to faculty in all fields, at all academic ranks, and from any academic or administrative department. Applicants must be U.S. citizens at the time of application and must hold a valid, current U.S. passport that does not expire within six months of the last date of the program.

Program Expectations

As an outcome of the Faculty Development Seminar program, participants are required to develop and implement a project to increase internationalization on their campus. Details and examples of these projects will be shared with awardees during pre-departure orientation. Projects should be implemented within one year of the conclusion of the program, at which time participants will be asked to submit a project report and share curriculum and/or documentation of the project for inclusion on CAORC’s Open Educational Resources site.

Participants are also required to contribute a short article for the CAORC blog Field Notes. This article should be submitted within three months of the program.

Application Process

Applications can be accessed via CAORC’s SM Apply application portal. You must sign up for an account to access the seminar application. This will allow you to save and return to your application before submitting. Please save your login/password information for future applications.

In addition to providing basic personal and professional information, applicants are required to respond to the following essay questions (up to 500 words each). In addition, applicants are required to:

• Upload a current cv/resume (less than 3 pages in length)

• Request a letter of support from a department chair, academic division head, or academic dean at your college or institution. You will be able to send a link to your recommender via the online grant portal, SM Apply, by entering their contact details, which will trigger the system into sending an automated email. Your recommender will then be able to upload their letter. Recommendation letters will be confidential in the system.

• It is advisable to enter your recommender’s contact details into the recommendation letter section of the application as soon as possible (and click ‘mark as complete’) so that they have sufficient time to complete and upload their letter. The applicant is responsible for checking in with their recommender to ensure the letter is submitted by the recommender deadline. CAORC is not able to reach out to recommenders on behalf of the applicant.

10

More information here

New Fellows at Inya

Christian Gilberti is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of California - Berkeley. His project focuses on “Burmese Students Traveling to Colonial India and Debates Surrounding “National Education” in Burma, 1870-1921.” He mentions that “[d]uring the British Raj, Burmese students chose to go abroad due to a lack of educational resources at home. As Burma was then a province of the British Indian Empire, many Burmese students traveled to India. There they made connections beyond their homeland and questioned what it meant to be “Burmese” within the British Empire. I explore how Burmese students’ dissatisfaction with Indian education led them to articulate a new ideal of Western-style “national education” for Burma. In the process, colonized students strategically defined how to be both a nationalist and an imperial subject through debates about colonial educational reform.” Christian will travel to India for field and archival research in Fall 2023.

Peter Alexander is a MA candidate in the Department of History at Northern Illinois University. His project titled “From Monarchy to Bourgeoisie: How Stewardship of the Shwedagon Pagoda Passed to Colonial Rangoon’s Burmese Elite”, places the Shwedagon Pagoda as a symbol of both Buddhist reverence and Burmese nationalism. Alexander considers that “[i]n the early colonial period, prior to 1900, questions of the proper stewardship and management of the site triggered the development of new social relations and forms of moral authority. Trustees of the pagoda were appointed by the colonial government, but soon found that they also answered to the Burmese community and other ethnic groups. This project will investigate how conflicts over corruption and democracy transformed the management of the Shwedagon Pagoda and set the stage for an anti-imperialist, pro-nationalist movement in Burma.” Peter’s field research will be conducted during Summer 2023 in the U.K.

11

This program is funded by CAORC through a grant from the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the U.S. State Department.

Ongoing Workshop Series at Inya

The ‘Myanmar’s Borderlands: Past, Present, and Future’ initiative is an 18-month project aimed at better understanding Myanmar’s borderlands and how they have historically shaped, continue to shape, and will contribute to shape Myanmar in the future. Here we introduce you to the workshop facilitator, Dr. Kimberly Roberts, our Summer 2023 Research and Mentoring Fellow, and, in the following pages, to the 23 junior researchers. After online morning sessions on research methodology held on June 26-30, the eight groups of junior researchers are currently working with Kimberly on refining their research topic and planning their research activities during the 10-month period of the project. The groups will present their findings at a conference in July 2024 in Bangkok.

Dr. Kimberly Roberts is a political ecologist with expertise in rural agrarian change and resource frontiers in the uplands of South and Southeast Asia. Roberts holds a Ph.D. in Human Geography, a M.Sc. in International Conservation and Development, and a B.Sc. in Environmental Studies. For the last 20 years Roberts has lived and worked in urban and rural spaces of mainland Southeast Asia and North America, collaborating with development practitioners, students, and researchers

from across the South and Southeast Asian diaspora on the socio-political intersections of environmental degradation and community development. Spanning the physical and social sciences, Roberts has presented as geography, Asian studies, borderlands, feminist geography, agricultural, engineering, and history conferences and published in Asian studies, geography, and geopolitics journals. Below, Kimberly explains her approach to the workshop.

The uplands of Southeast Asia are undergoing rapid environmental change. In research, teaching, and mentoring, I work across differences of identity and experiences to collaboratively explore nature and society debates regarding environmental degradation, conflict, and rural agrarian change in the borderlands of Myanmar. For my dissertation I drew on scholarship from political geography, political ecology, and resource conservation to investigate the uneven power relationships between states/non-state territories, social movements, and resource frontiers in conflict zones in the borderlands of Thailand and Myanmar. Through interactive classroom activities and assignments, I bring insights into the classroom, in ways that students can experience and connect to individual, community, regional, national, and transnational levels of practice. For example, as part of an intensive social empowerment leadership and advocacy

training program, I used theater forum to teach research methods to youth from Shan, Kayah, Mon, and Karen states in Myanmar. Additionally, in a ten-week study abroad program I co-directed through the University of Washington, I combined seminars with 26 site visits/ guest speakers to allow students to learn directly from ethnic minority community members and organizations about environmental, political, and socioeconomic contributions to human rights violations along the Thailand-Myanmar border.

Questions about environmental degradation and society led me to the borderlands of Thailand and Myanmar 16 years ago. For two years, I lived 17 km from the Myanmar border at a small farm agroforestry research center. There, I worked alongside Lahu, Dara’ang, Karen, Kachin and Akha colleagues in undocumented migrant communities. My ongoing and future research will

continue to advance this work exploring questions of resilience, resistance, equity and justice in environmental issues across Myanmar borderland communities, a topic expanded on in a special collection ‘Remaking Resource Frontiers in Myanmar’ published in Geopolitics that I co-edited. As a result of the coup in Myanmar, however, many of the local leaders and organizations are now in exile. As such, I will look at the impact of the coup on environmental and human rights through a project that asks about the political ecologies of conflict resolution in exile from Myanmar’s borderlands.To conclude, through collaborative transnational partnerships that emphasize ethical and safe research methods, I contribute to debates in, and questions surrounding, rural agrarian change and conflict in the face of climate change within the fields of geography, political ecology, and environmental studies from the borderlands of Myanmar.

12

The Summer 2023 ‘Myanmar’s Borderlands: Past, Present, & Future’ Workshop Series is funded by the U.S. Department of Education under Title VI of the Higher Education Act.

I am Abdu Rahman from Maungdaw, northern Rakhine State. I am a humanitarian and field researcher. I completed my high school in 2015. Furthermore, I attended TOEFL prepation course at Thabyay E-learning Platform and many other online courses on research methodology and journalism. I have been advocating for Rohingya education since 2018, and working as a field researcher and transcriber in IOM since 2019.

My name is Muhammed Shahid I am a community teacher and I have been working for IOM-CwC as a researcher and transcriber since 2019. I am originally from Maungdaw, northern Rakhine State. I graduated from Sittwe University with B.Sc (Hons) Physics in 2012.

I am Sawna Ullah from Maungdaw, Rakhine State. I completed my high school from Alay Than Kyaw High School in 2016. I attended English

I am Naw Seng, a junior researcher from Myitkyina, Kachin State. I have a strong background in community development and I am passionate about education and community empowerment. I started a degree in Chemistry at Myitkyina University in 2018 and have been actively involved in the Catholic Student Action Myitkyina (CSAM) as a student coordinator since 2019. I have gained valuable teaching experience as a guide teacher in church boarding houses from 2018 to 2020 and recently I furthered my education in community development through a research diploma program at Thabyay Education Foundation. During my studies there as a research fellow, I wrote a research paper related to environmental themes. Currently working as an assistant researcher at the National University of the Union of Myanmar (NUUM) on a theme related to education, I am also working as a manager in the Student Learning Resources Center (SLRC).

My name is Khaing Yamin Lwin . I obtained a B.A. in International Relations at Dagon University. In summer 2022, I was a student researcher at the Center for Research, Policy and Innovation in the U.S. I am passionate about politics and law but also about research that can contribute to policymaking and promotion of human rights. I am pursuing some continuing

literature course and computer courses in Chittagong, Bangladesh. I have been working for various projects as animator, peace builder, training of trainer, peace education trainer, researcher and facilitator.

We are very excited about this innovative Summer 2023 Research and Mentoring Workshop Series. We join the workshop from the world’s largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar and focus on humanitarian relief to refugees and public health in borderlands for our project. We hope to contribute findings that will support the health and safety of the people who have been displaced by violence and persecution.

The UN agencies and other national and international organisations are providing basic necessities to Rohingya

refugees. Yet, there are huge gaps in the provision of humanitarian relief because service providers typically don’t consult with beneficiaries before implementing new assistance programs.

In addition, public health measures must be implemented in order to prevent the spread of diseases among refugees and local populations in the borderlands. This may involve providing access to primary health care services, providing immunization, and establishing sanitation and hygiene facilities. Healthcare is the major issue for Rohingya refugees who reside in the borderlands and usually lack proper medication and treatment although there are many humanitarian health facilities in the camps.

Overall, humanitarian relief and public health measures are necessary in order to ensure the safety and well-being of the people affected by the violence and persecution in the borderlands.

I am Ngun Cer Hlei Iang, an aspiring educator and junior researcher from Hakha, Chin State. Despite the challenges people have faced since the 2021 coup, I have been pursuing an International Relations degree at Monywa University. I strongly believe in the importance of continuous research for gaining a better understanding of current affairs. My past research experience includes an investigation into the education freedom in 2018 as a research fellow and a study on mothertongue based education in 2021 with colleagues from Chin bridge Institute. Through research fellow programs, I have gained valuable experience in fieldwork, data collection, process improvement, coordination, and documentation handling. My internships at the Chin Human Rights Organization and position as a subject teacher have allowed me to engage

Khaing Yamin Lwin

Hnin Eaindra Lwin Eaindray Nyein Chan Pyae

learning about constitutional law at the Constitutional Federalism Institute.

I am Hnin Eaindra Lwin and I completed my BArch from West Yangon Technological University. I have been working at a graduate architect posi -

in statistical and financial data analysis related to freedom of religion. Driven by a lifelong dream, my ultimate goal is to become an educator and researcher so as to help students maximise their educational experience.

Our research topic is about language barriers in the education systems of Myanmar’s borderlands with a focus on enhancing access and quality in the multilingual communities of Kachin and Chin States. Language plays a crucial role in education: access to quality education may be difficult if students are not proficient in the language of instruction. We propose to identify challenges faced by students and effective strategies in order to mitigate the problems linked to language barriers and ensure equitable educational opportunities for all. We hope to contribute to the creation of an inclusive and equitable educational environment that support the diverse linguistic needs of students.

tion for over three years mainly focusing on the restoration and conservation of historic buildings. I am eager to learn new things and interested in taking part in projects that promote sustainability and development.

I am Eaindray Nyein Chan Pyae . I obtained my B.A. from Dagon University specializing in Law. I worked as a training and outreach intern at a social

13

Naw Seng Ngun Cer Hlei Iang

Abdu Rahman Muhammed Shahid Sawna Ullah

enterprise. I am passionate about community development works, ethnic affairs, constitution, migrant workers in developing countries, and the complex legacy of authoritarianism. I am now pursuing a political science, governance, and public administration course for further professional development.

We will work on labour migration and human trafficking, two major issues hindering the development of Myanmar and undermining regional security . Myanmar is currently suffering problems from brain drain,

I am Moris Zin Htet Aung. I hold a Bachelor degree, majoring in Computer Technology from the University of Computer Studies (Loikaw) in 2012. I gained some work experience at a government department and a youth organization before the coup in 2021. After the coup, I stepped down from these responsibilites. On May 21, 2021, armed clashes broke out in my hometown, Deemawso. Soon after, I volunteered in IDP camps. In 2022, I illegally moved to Thailand for security reasons. As an illegal migrant, I would like to participate in some research on cross-border migration from Myanmar to Thailand. I feel lucky to join Inya Institute and be part of the workshop series.

My name is Nan Myinzu Minn. I have a B.A. in English Literature from Mandalay’s University of Distance Education and a Master of Public Admin-

My name is David Naung Ding. I am a freelance data analyst at Defection Program and a former news and information officer of the current civilian administration. I graduated in 2017 from the Myanmar Aerospace Engineering University (MAEU) and worked as a sales engineer until the coup. I enjoy participating in networking, communication and capacity building workshops, seminars, and outdoor activities. My volunteering experience include the support to a religion and rule of law training hosted by a faithbased organization, Institute of Global Engagement (IGE), and my activities as executive member of MAEU Student’s Union (2013-2016).

I am Su Paul Lu. I am currently volunteering at a prominent Kachin organization. I worked as a project officer and trainer in Rakhine State for two years and delivered there peace building and media literacy training for hundreds of youths.

exploitation and human trafficking and the majority of young people from Myanmar are forced to work and deal with unjust working conditions and trafficking abroad, not only as citizens of a developing nation but also as undocumented migrants who lack legal protection from their home country. Along Myanmar’s borders, legal and illegal migrants face huge problems caused by armed conflicts and a lack of humanitarian aid from neighboring countries and the international community. We hope our research will

Moris Zin Htet Aung Nan Myinzu Minn

istration (Management) from Flinders University, Australia. I worked as an election officer from 2016 to 2020. I then stepped down from any official responsibilities after the coup. I had to leave the country to escape from being arrested by SAC. My research interests include migration, election and public policy.

I am Moe Yeh Phaw from Deemawso, Karenni (Kayah) State. I obtained a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery at Taungyi Medicine University but while I was in my third year in 2021, I dropped out. After armed fights broke out in Deemawso, I had to live in an IDP camp in Taungyi. There, I work as a volunteer teacher for IDP children at Self-supporting Fabre School, Taunggyi.

David Naung Ding Su Paul Lu

Jakan Naw Awng

Before that, I worked and volunteered at organizations that are working on Myanmar’s peace process and other development fields. I majored in Social Studies and graduated from the Liberal Arts Program, Myanmar Institute of Theology in 2017. I currently live on the ChinaMyanmar border where I work and observe the social and political changes happening within the Kachin Region and at the country’s level.

I am Jakan Naw Awng. I am a researcher and political analyst based in Kachin State. I earned my Masters’ degree in Chinese Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Relations at Tsinghua University. My research interests cover China-Myanmar relations and ethnic armed conflicts. I worked as a field

contribute to a better identification and understanding of the problems legal and illegal migrants face and lead to possible solutions that support migrant workers and, more generally, the country.

I teach Mathematics and Chemistry to Grade 10 students.

Our research topic is about the challenges of cross-border migration from Myanmar to Thailand following the 2021 coup. Myanmar’s overall situation has been deteriorating in every aspect including political, economic, security, social and education. The forceful and voluntary migration causes challenges for both the migrants and the host communities. We will seek to answer the following question: “What are the challenges both legal and illegal migrants face when leaving Myanmar for Thailand after the 2021 coup?” We will consider both legal and illegal migration routes leading to the host country. The results of the research will provide a better understanding of the cross-border migration and the consequences both legal and illegal migrants face in this context.

researcher at the Kachinland Research Centre for one and a half years. Prior to this research experience, I was an English teacher enthusiastic about community development and social change. Currently, I am volunteering at a local think tank group that acts as an advisor to various Kachin political stakeholders.

Our research will seek to answer the following question: “How does the military coup affect the existing governance mechanisms of KIO/KIAcontrolled areas at the China-Myanmar Border?” We will explore and investigate the changes and progress within KIO’s governance system, the positive and negative externalities of the collaboration between KIO and other national political stakeholders, the arrival of CDMers, the social changes that affect its governance mechanisms, and the relocation of human and intellectual resources after the military coup.

14

Moe Yeh Phaw

My name is Myo Myint Myat Thein I live in Yangon and work as a youth development instructor, specializing in enhancing consecutive learning. I am passionate about reading and researchbased learning. I consider that human rights and justice are not only dear values to me but also to each of our team members.

I am Sithu Aung, a former law student whose education was disrupted by the coup. I am passionate about human rights. With a Diploma in Human Rights from Spring University Myanmar, I seek to explore the workings of international organizations and enhance the enforcement of human rights globally. Additionally, I am interested in the connections between human rights and the environment.

I am Ahmmed Sukanu from Nga Sar Kyu Village, Maungdaw. I was not able to complete my graduate studies in Myanmar after the persecution of 2017. Therefore, I have completed a journalism workshop through PROI. I am a researcher, photographer, and poet. I have worked for NGOs agencies and did research for various universities and now I am facilitator at BRAC University’s Center for Peace and Justice (CPJ).

My name is Md Ahtaram. I was born in 1996 in Rakhine State. Due to the military policy of ethnic cleansing, I fled in Bangladesh as a refugee in 2017. I was unable to complete my graduation. However, in 2022, I studied political science through an online undergradu-

I am Zai Sam, a young social activist from Manhkring Internally Displaced People (IDP) camp, Myitkyina city, Kachin state. There I focus on reducing violence within the community and promoting and delivering educational opportunities to underserved young people. I have a strong interest in conducting research on environmental issues as well as on the challenges indigenous and marginalised people face in securing healthcare and education. I recently worked as a research assistant at the Centre for Research, Policy and Innovation, Burmese American Community Institute (BACI). I am also an alumnus of the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI) Academic fellowship program on Civic Engagement at Arizona State University (Spring 2022).

My name is Htawshe Dau Hkawng. I live in Kachin state. I graduated from the

My name is Myat Thiri. I am the youngest member in this group and live in Yangon. I studied one year at the Co-Operative University in 2019. Now, I study via online and do self-learning. I am especially interested in community development and research. I am also working as a volunteer in my community library and also pursue online research training.

Our project will focus on legal status and impediments to aid for Myanmar refugees in Mizoram. Despite supports from local communities and state government, refugees in Mizoram deal with irregular food supplies, limited job

opportunities, and lack of legal status and support from international organizations. Legal protection for refugees is crucial. India lacks a legislation addressing their status even though Mizoram government gives them temporary ID cards. Refugees are treated as illegal immigrants, which hinders access to safety, education, employment, and basic needs. Advocacy for asylum and the development of appropriate policies and international refugee programs are vital. Ensuring legal status and continuous aid for Myanmar refugees in Mizoram is crucial for upholding their dignity and protecting their basic rights. By establishing a secure legal framework and providing sustained support, refugees can make informed decisions about their future, including potential resettlement or seeking asylum in other countries.

NGOs and agencies as a researcher.

ate program at Yangon Cosmopolitan University. I also completed a Diploma in Critical Thinking and Analysis Skills at CPJ. I now work as a community-based researcher, social worker and freelance journalist.

I am Mohammed Mirza Nu, a researcher and teacher with over 6 years of experience in the field. I completed my matriculation in 2016; unfortunately I was not allowed to go to university. In Bangladesh, I joined courses such as sociology, critical thinking, and peace building and I have worked with various

Our research focuses on the crossborder trade and relationship between Rakhine and Bangladesh as well as the historical impact of militarization on the Rohingya population. We aim to explore Rohingya’s historical perspectives as well as commonly acknowledged claims that Rohingyas are, falsely, portrayed as Bengali. Our particular interest lies in the relationship between the Rohingya Muslim minority and the policy ramifications of the Myanmar government. Understanding the complex history of cross-border trade and relationships between the Rohingya and Bangladeshi communities is integral to our research.

Kachin Theological Seminary and I am in the process of obtaining a Master of Divinity Degree from the Myanmar Institute of Theology. I am currently working as a facilitator at a local feminist organization and as an in-charge oficer at the Community Learning Center in Waimaw which provides free, critical education program to children and young people in Kachin state. My research interests include religion and society, ethnic affairs, issues related to marginalized communities, identity, cultural studies and social justice.

I am Zaw Sar Zu, an energetic youth and social studies student currrently at the Liberal Arts Program, Myanmar Institute of Theology. For my major, I stud-

ied social suffering of industrial workers. Moreover, I am pursuing educational studies at the Naushawng Community school. I am a keen observer of my community when it comes to environmental and social issues. I also work as a teacher at a community learning center. My larger goal is to address access to education in relation to socioeconomic conditions, social suffering and promote justice and education in the Kachin borderlands.

Our research topic addresses the lack of access to education in northern Myanmar borderlands (Kachin State and China) due to geography and current socio-economic situation. Our team will investigate and conduct research on the Kachin State-China borderlands and will focus on young people’s and youths’ access to quality education as well as hinderances to this access.

15

Zai Sam Htawshe Dau Hkawng Zaw Sar Zu

Ahmmed Sukanu Ahraram Shine Md Mir Za Nu

Myo Myint Myat Thein Sithu Aung Myat Thiri

New Books On Myanmar

highlights the myriad facets of Myanmar by contemplating on its inherent strengths and visible weaknesses. It would be indispensable for scholars and researchers of Southeast Asian studies, Asian studies, area studies, Myanmar studies, political studies, cultural studies, and sociology.

Alexandra Kaloyanides

Columbia University Press, 2023

Wider Bagan

Elizabeth Moore (Editor)

ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2023

Wider Bagan: Ancient and Living Buddhist Traditions is the first book to define the area outside the renowned Buddhist capital where vestiges of Bagan era cultural traditions can be found. From nearly six hundred attributes inventoried in Wider Bagan, thematic and geographical analysis of the Wider Bagan data reveals a related but different trajectory from that of the capital. Much has been written about Bagan, but little attention on the ground has been devoted to areas beyond the capital. These places have stories to tell—ones of the past and of the present—that are narrated in this book.

Myanmar’s Changing Political Landscape: Old and New Struggles

Makiko Takeda, Chosein Yamahata (Eds.)

Springer Singapore, 2023

The coup d’état in 2021 terminated Myanmar’s limited and nascent democratization. This book brings an even mix of researchers both within and outside of Myanmar to critically discuss how different agents and their interactions, in the form of centerperiphery as well as state-non-state relations, continuously shape today’s political landscape. Its interdisciplinary composition also invites readers from various backgrounds to grasp with engaged research that identifies the various challenges and addresses ways in which to facilitate change from local and international perspectives.

Baptizing Burma explores the history of how the American Baptist mission to Burma failed to convert the country yet succeeded in transforming its religious landscape. Alexandra Kaloyanides examines how the Burmese majority positioned Buddhism to counter Christianity, how marginalized groups took on Baptist identities, and how Protestantism was reimagined as a Southeast Asian religion. She considers a series of holy objects to reveal the mechanics of religious practice in a period of entangled empires—British, Burmese, and American. By telling stories of four key things—the sacred book, the school house, the pagoda, and the portrait—this book illuminates the histories of Burma’s last kingdom and the unexpected consequences of America’s first overseas mission.

Reflections on Myanmar Identity, Heritage, Aspirations

Reshmi Banerjee, Routledge India, 2023

Myanmar is known for its engaging history, rich cultural heritage, and diverse ethnic communities. The author weaves these themes into a common narrative of discovering Myanmar through a holistic lens. The book aims to explore the country through its history, culture, communities, and challenges. A unique contribution, the book

Baptizing Burma: Religious Change in the Last Buddhist Kingdom

The Reconquest of Burma 1944–45: Operation Capital to the Sittang Bend

Robert Lyman

Osprey Publishing, 2023

Written by a foremost expert on the British Army in World War II, this superbly illustrated work details the Allied operations to retake Burma from Japanese control. Accounts of Operation Capital, the capture of Meiktila and Mandalay, the Allied advance in the Arakan, the race for Rangoon, Operation Dracula, the Battle of the Sittang Bend and Japanese breakout operations across the Pegu Yomas are supported by easy to follow 2D maps and 3D diagrams. Among the events brought to life in vivid battlescene artworks are an SOE-led ambush in Operation Character, and the famous Defence of Hill 170 in the Arakan.

16