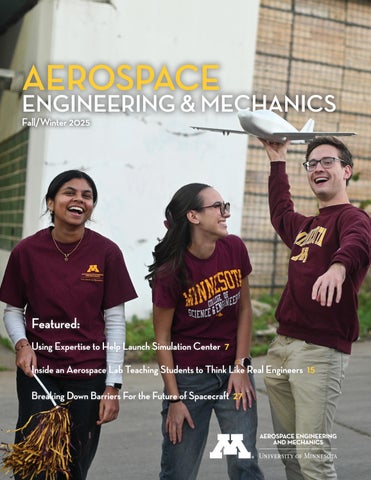

AEROSPACE

ENGINEERING & MECHANICS Fall/Winter 2025

Featured: Using Expertise to Help Launch Simulation Center 7 Inside an Aerospace Lab Teaching Students to Think Like Real Engineers 15 Breaking Down Barriers For the Future of Spacecraft 27

2

AEROSPACE

ENGINEERING & MECHANICS Fall/Winter 2025

Featured: Using Expertise to Help Launch Simulation Center 7 Inside an Aerospace Lab Teaching Students to Think Like Real Engineers 15 Breaking Down Barriers For the Future of Spacecraft 27

2