Alchemy is defined as the process of taking something ordinary and turning it into something extraordinary, sometimes in a way that cannot be explained. Like alchemists, artists have for centuries altered forms of matter in an attempt to transform their artistic visions and make them reality. The encaustic arts, in particular, deal with the transformative process.

Beeswax, damar resin, and various oil paints and pigments (and whatever other found objects may be incorporated) are layered, mixed, and blended with the help of direct heat, usually a propane torch. And the results are often alchemical. What is created is original and unexpected, in fact something more than expected or intended.

The artists whose work appears in this issue of Wax Fusion transform the ordinary into the extraordinary, sometimes in unexpected and mysterious ways. As we reviewed their articles, certain words and phrases seemed to leap off the pages, resonating with the enigmatic power of transformation. The author-artists obviously felt this magic palpably and documented it in their own words, which sometimes gave us goosebumps. Read on… There was something about this medium that allowed me to express parts of myself that were so personal, private, and painful. The alchemy in expressing my thoughts and emotions with the medium enabled me to translate how I felt in a most profound way. — Kelcie Bryant-Duguid

My process and approach are sophisticated primitive, my studio, a lab of sorts. I usually work more in the outside environment, where some crazy ideas seem to brew. I set things on fire, pound things with rocks, rip and tear things apart to either weave or stitch them back together, paint, and mix unlikely items together. — Shannon Weber

The more layers there were in a piece, the less details of each layer came through clearly; thus, the more story I attempted to tell, the less the story was recognizable. As a result, the wax in each piece exists within a duality, both as a preservative and an obscuring element balancing both the desire to preserve a memory and the acceptance of the inevitability of forgetting. — Anne Feller

I disappear when I paint. I don't have conscious thought. I'm unaware of my body floating in a time warp. I exist and my painting exists; that’s it. All else is an intrusion….Most often when I find something distracting, mysteriously, answers come to me. There are many times when I wonder how I know what to do, or how to do it. It lies within me, unspoken. It’s transformation, magic, alchemy. — Karen Frey

Because (my father) did not use a scientific method for his studies, he couldn’t prove that his formula was the same used by ancient artists….If we would be able to prove this, it would be one of the most important discoveries in history — the recreation of the lost encaustic paint, lost for almost 2,000 years. — Pedro Cuní

His scalp, which reminds me of a distant view of Earth, is translucent from hot wax saturating the fibers, showing wonderful organic patterns. Like the Earth, his body has become a living host for the marine life sculpted from encaustic wax. — Deanne Row

As encaustic artists, we are all alchemists. We transform the ordinary materials of beeswax, tree resin, pigment, and more into art. We uncover ideas and inspiration around us every day. In making our mark we create something that can be seen, touched, and experienced as possibly profound or beautiful, perhaps disturbing or soothing; we transform and make manifest human experience into gold. — Shary Bartlett

We hope you enjoy reading this Alchemy issue of Wax Fusion as much as we loved editing it. And, as always, we appreciate your feedback. Please contact us at WaxFusion@International-Encaustic-Artists.org with comments, questions, ideas, and suggestions. While this journal exists to serve the needs of IEA members, it is also free and available to the public. You are welcome to share this journal with anyone interested or working in the visual arts, looking for information on encaustics, or beginning to explore the world of encaustics.

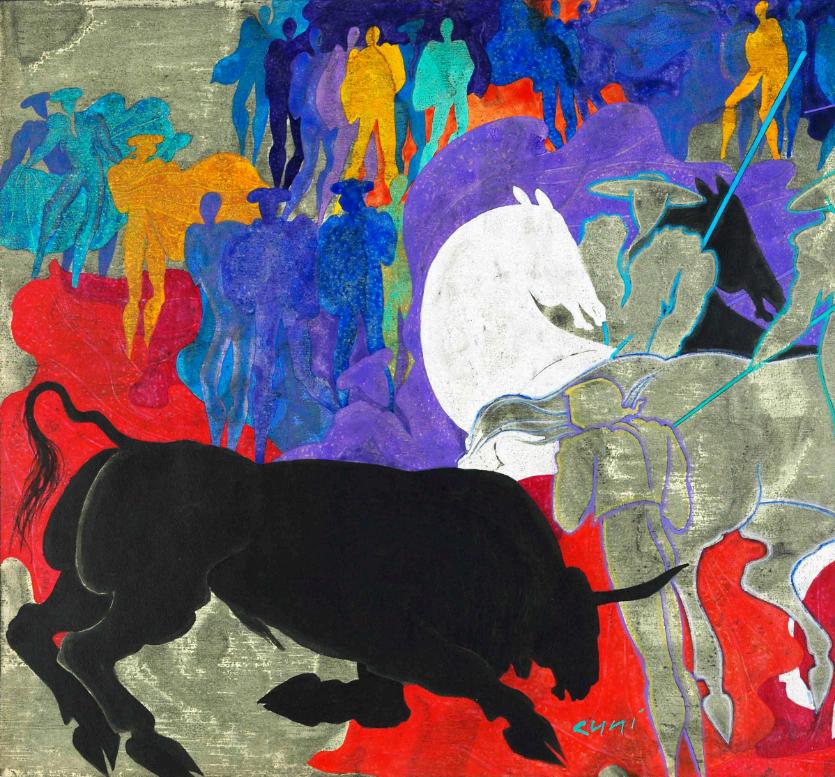

Lyn Belisle S. Kay Burnett Paul Kline Prelude of Bullfighting Festival by José Cuní Encaustic Cuní on paper

Prelude of Bullfighting Festival by José Cuní Encaustic Cuní on paper

When I envision an alchemist, I see a grey-haired, wizened old man hunched over beakers, mixing and heating liquids in his search for the magical transmutation of base metals into gold. Dressed in my messy apron and poised with my brush over a palette of melting beeswax, I don’t look like that man at all.

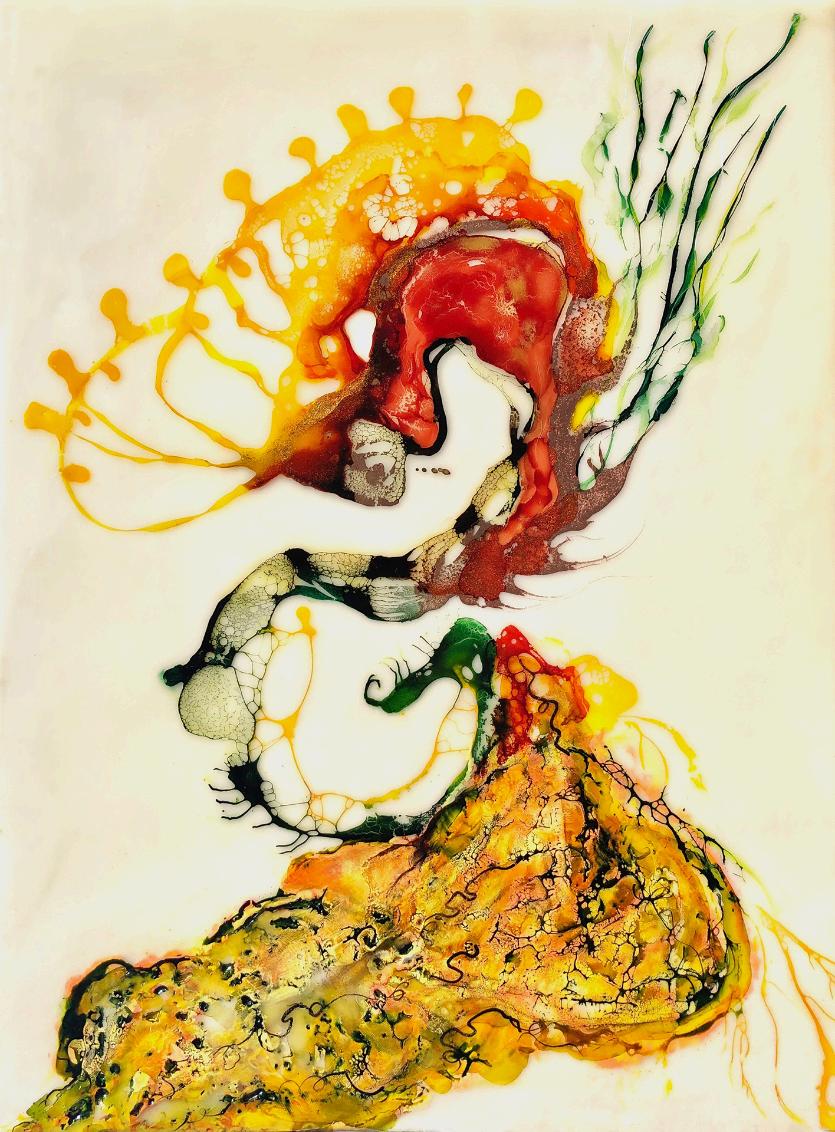

As encaustic artists though, we are all alchemists. We transform the ordinary materials of beeswax, tree resin, pigment, and more into art. We uncover ideas and inspiration around us every day. In making our mark we create something that can be seen, touched, and experienced as possibly profound or beautiful, perhaps disturbing or soothing; we transform and make manifest human experience into gold. This is the gift, honour, and responsibility of being creatives. Like you, no doubt, I’ve loved encaustic for a long time, and yet still find myself seeing other media and wondering with delight and curiosity: “Hmmm. I wonder how this might be partnered with wax?” This occurred when I discovered the flowing, illuminated magic of alcohol and India inks. Because of my curiosity, I became a scientist of sorts – exploring the alchemical magic of painting with alcohol and India inks on encaustic.

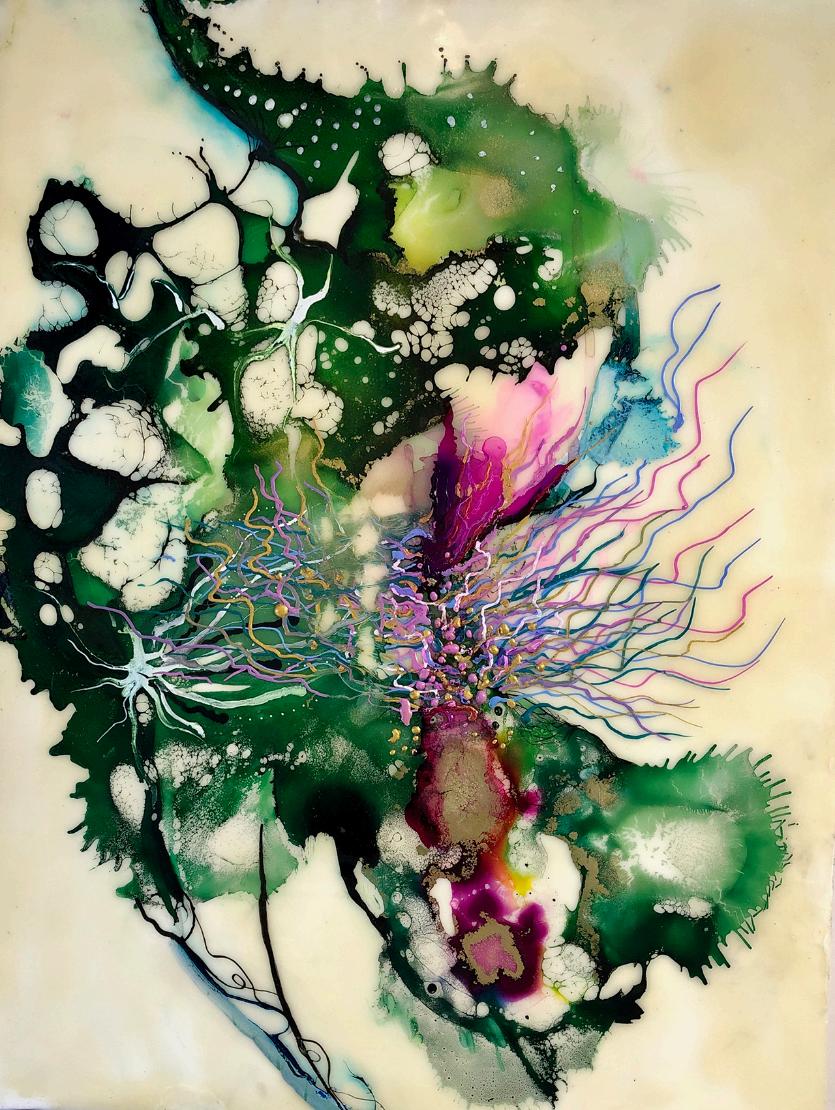

Rise, Like a Phoenix Ink on encaustic 16 x 12 in

My explorations resulted in the series, Inexorable Growth. These paintings depict earthly or undersea life such as insects, plants, flowers, fungi, and microscopic molecules of plant, human, and celestial life. As biomorphic forms, these emerged literally 2- and 3dimensionally from the painted, sculpted surface. Both in their creation and design, these surreal abstract paintings became a crossover of science and art –meditations and reflections on nature, life, humanity, environmental change, and genetic modification.

Bursting Forth Ink on encaustic 8 x 10 in

• Try using the inks on Yupo paper as you might use watercolour paints. You can thin the ink with 90-99% ethanol or isopropyl alcohol, or alcohol ink blending solution. Try dropping ink into a small pool of blending solution or alcohol and see what happens.

• Use a brush or eyedropper or simply apply directly from the ink bottle.

• Try blowing ink with a straw or compressed air for wave-like efects.

• Remove unwanted marks with clear alcohol and cotton swab.

• Add accents with metallic inks.

• Make notes about the diferences between alcohol and India inks and discover their distinctive qualities and applications.

• Use alcohol inks in well-ventilated areas.

• Alcohol inks are dye-based, fugitive, and can fade over time, especially if placed in sunny locations. Coloured and black India inks are archival and lightfast. Acrylic inks are not compatible with wax.

Once I felt confident and could (to some extent) control my marks, I applied my explorations to a smooth, prepared encaustic surface of white or clear medium on board. To my surprise, I found that the ink reacted remarkably diferently on wax, especially when fused. The molten surface was hard to manage; but in rendering the inks unstable, I was delighted to generate cell-like bursts, blossoming waves, tantalising cracks – most of these stunningly beautiful (yet not infrequently, horrendous messes!). And if I was not careful and over-fused, I burned the ink up altogether!

I persevered.

• Employ the mark-making techniques you have learned (on Yupo paper) on your wax.

• Experiment by applying varied heat and flame forces from diferent distances. I prefer fusing with a very light torch flame. A heat gun can be used, although this tends to blow the ink across the surface more. Fuse carefully and successively; let cool between fusing areas to preserve the mark.

• Alluring cell forms, lace-like patterns, and cracks appear if fused carefully. Wave patterns can be achieved using a heat gun.

• Be curious. Experiment, keep records and photos, and learn as much from your “failures“ as you do from your “successes”.

• Try carving into wax.

• Wet inks are flammable! Fuse only when ink is dry and use caution when fusing. Ensure good ventilation and fire precautions are in place when working with wax and ink.

• Wax cannot be sprayed with UV protective spray.

• Synthetic Yupo paper cannot be fused into wax.

Internal Takeover Ink on encaustic 10 x 8 in

Over time, I intuitively followed the growth taking place on the surface, building upon the shapes and natural designs that were emerging. By carefully fusing, layering inks, and carving into the wax, magic emerged somehow, between my hand and the materials. Brush, calligraphy tool, clay loop tool, India ink on encaustic

I was fascinated by the natural-looking images of cells, flowers, insects, and undersea creatures that materialized before me. These biomorphic forms looked fascinating, vaguely familiar, and yet also somewhat mutational and unsettling at times. I felt I was witnessing alchemy manifested through materials: beeswax, tree resin, and pigment. All energy-laden resources issuing from the living environment. All shape-shiftingly solid, yet aqueous in their molten/fluid forms. I found myself thinking about the cycle of life, organisms, the environment, and their fragile interrelationships. I was encouraged by the symbolism of beeswax as a preservative.

Briny Hyacinth Ink on encaustic 16 x 12 in

Jellyfish Spell Ink on encaustic 16 x 12 in

In the next stage of painting, “figures” sometimes began to emerge. As I saw shapes and images appear, I’d enhance them with gestural lines, using India ink and a dip pen. My painting became more abstract, and I began to further the depiction of growth or decay by adding a 3-Dtextured surface using a hot stylus. I delightedly, meditatively, lost track of time by adding myriad raised lines and tiny dots. These 3-D forms emerged like sculptural, topographical sea floors, mountains, and valleys.

• Enhance your imagery using black India ink with a dip pen.

• Ink does not need to be fused into the wax; however, I prefer to fuse, so the ink sinks somewhat into wax.

• Clear wax can be layered over ink, which will obscure the luminosity to some extent.

• Try using an electric stylus, Wax Writer, kitska, or tjanting tool to add 3-D encaustic lines and dots to the wax.

My studio became a science lab, where I compounded the four elements: Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. In their pollen-gathering flight between flowers, bees and their beeswax represent air and earth elements. In essence, pigments and the wood substrates I paint upon issue from the earth. When my pigments are mixed into inky-liquid form, or when beeswax is molten, these represent the qualities of water. And of course, as an encaustic painter, I light my torch with fire to melt and fuse my creations. In their creation and design, painting with these media summons a crossover between the alchemical realms of science, art, and creative magic.

Inexorable Growth — the body of work that emerged from this enchanted realm of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water — is a meditation and reflection on nature, life, environmental change, and interdependence. In this way, the works themselves are micro- and macroscopic metaphors for the dynamic and unstoppable character of growth, disease, evolution, and decay.

Adrift Ink on encaustic 16 x 12 in

Shary Bartlett is a Canadian artist living in Vancouver, Canada. Her mixed-media paintings and sculptures are held in public and private collections internationally. She teaches art workshops globally and nationally and has been a long-time fine arts instructor at Capilano University, Langara College, and Red Deer College. Shary’s encaustic mixed media work and techniques are published in the books, Encaustic Art in the 21st Century and Encaustic Revelation. Her personally-curated encaustic wax pigments sets, created with Enkaustikos Paints, are sold internationally.

Shary ofers a variety of inspiring instructional videos online, and she is an instructor with the year-long encaustic masterclass, Painting with Fire.

If you’d like to learn more about exploring alcohol and India inks on encaustic; or how to create a smooth encaustic surface suitable for alcohol and India inks; or adding 3-D surface lines using wax writing tools, please visit Shary’s website for online instructional videos at www.sharybartlett.com/workshops.

You can view Shary’s work at www.sharybartlett.com www.facebook.com/sharybartlett www.instagram.com/sharybartlett www.pinterest.com/sharybartlett www.youtube.com/sharybartlett

Water-soluble Encaustic Cuní comes from the studies of my father, José Cuní, a painter and expert in ancient Greek and Roman painting techniques. He was fascinated by encaustic paint and in particular by the possibility that the ancient artists had been using a variety of cold, water-soluble encaustic paint on murals.

He had done extensive work using fresco for murals, and he concluded that the Pompeian wall paintings, once assumed to be fresco, were not fresco. After receiving a scholarship to go to Pompeii to study the paintings on site and studying the paintings closely, he was able to reproduce the original formula used by the ancient artists, a water-soluble encaustic.

Because he did not use a scientific method for his studies, he couldn’t prove that his formula was the same used by ancient artists. After my brother and I grew up, we decided to try to prove that my father was using the same paint as the original artists. If we would be able to prove this, it would be one of the most important discoveries in history — the recreation of the lost encaustic paint, lost for almost 2,000 years.

Juchitlan de Zaragoza, Mexico Pedro Cuní Encaustic Cuní on canvas 17.5 x 40.5 in

We received samples of Roman paintings donated by diferent archaeological sites and museums in Spain and began to retranslate all remaining ancient texts using experts in Latin and ancient Greek, as well as doing chemical analyses of the original samples. After extensive historical and chemical research that I carried out at the chemistry department of Cooper Union in New York, the results of the research were published in the paper, "Characterization of the Binding Medium Used in Roman Encaustic Paintings on Wall and Wood" by the scientific journal Analytical Methods. The research finally proved that my father’s encaustic formula and the ancient one were exactly the same.

The discovery was presented at the Smithsonian Conservation Institute with a lecture and an exhibition of paintings by my father and me. This article is just a quick summary of the research that took over 20 years to complete. I am currently collaborating with The Egyptian Museum in Cairo studying their ancient paintings and painting materials.

We make Encaustic Cuní using the exact same formula the ancient Roman artists used. It is an unmatched, water-soluble paint medium, which lends its attributes to the beeswax, and allows you to paint as thick as oil paint or as diluted as watercolor with beautiful results.

2,000-year-old Roman samples of wall paintings used in our chemical analysis

Seville José Cuní Encaustic Cuní on wood

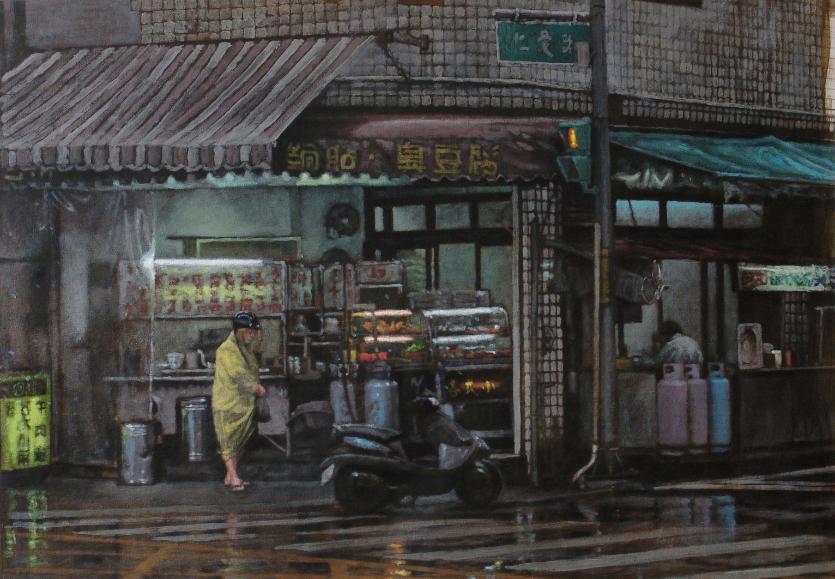

Next page, Taiwan temple Pedro Cuní Encaustic Cuní on canvas

Keelung Taiwan Pedro Cuní

Encaustic Cuní on canvas 21.7 x 31.9 in Cuní Water-Soluble Encaustic comes in 47 colors and offers the unique sheen and translucency of wax that requires no heat. Heat may be applied to accelerate curing of the paint, and clean up is solvent-free using soap and water. You can paint on various surfaces, including paper, canvas, and wood.

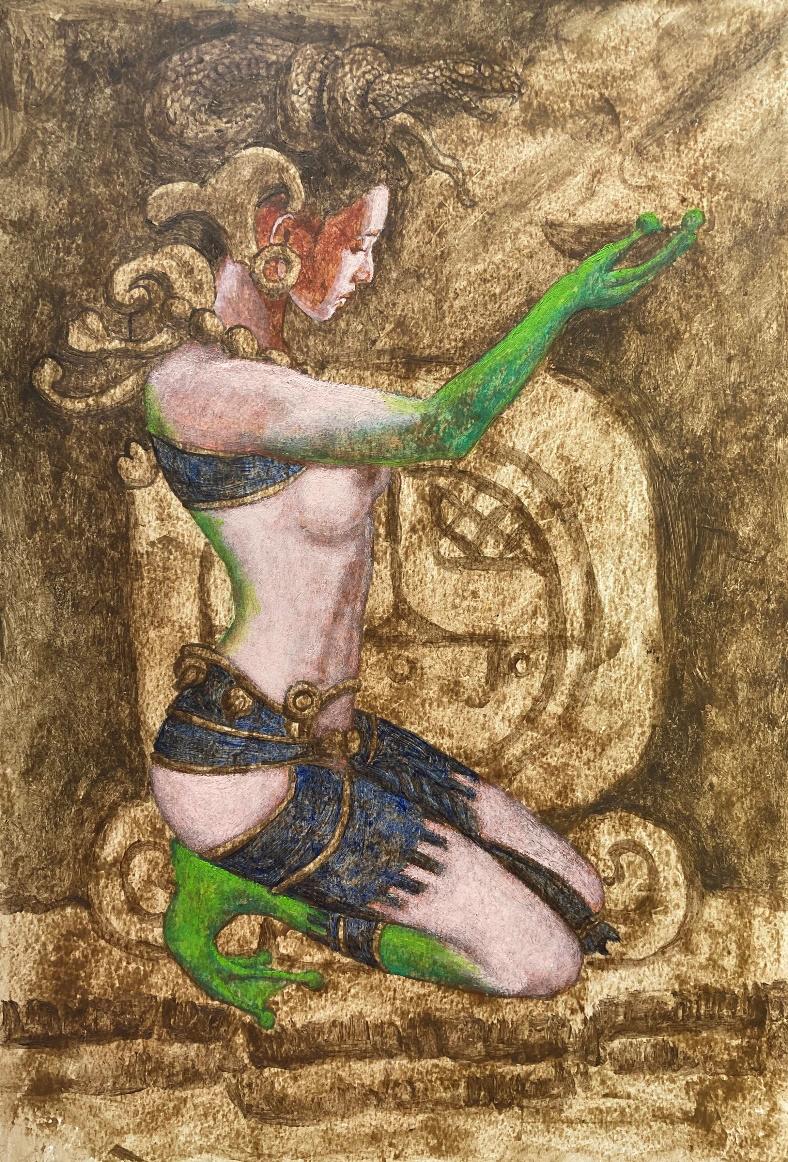

I was recently in Tulum, Mexico, and I became very interested in Mayan mythology, especially in the figure of the Mayan Goddess Ix Chel. I decided to paint on watercolor paper a version of Ix Chel because the texture the paper creates reminds me of stone, and I wanted to give it the feeling of an ancient wall painting.

For the background, I chose burnt umber. I mixed it with Encaustic Cuní medium to make the color more transparent. I could have diluted the color with water to make it more transparent; but in this instance, I wanted the paint to have more body giving innate depth to the color.

After the background dried, I proceeded to create a chiaroscuro efect by doing velaturas (additional thin layers of color) with brush and more raw umber mixed with medium to keep consistency and transparency.

Once this layer was dried, I started applying colors using glazes of cinnabar green, ultramarine blue, burnt sienna and burnt sienna mixed with white for the skin color.

In the background, I decided to change the texture by using the colors diluted with water applied with a watercolor brush to avoid brushstrokes being visible. By changing the texture and the way colors are applied, I enhanced the feeling of depth and space. I used ultramarine blue and carbon black for this stage.

While the carbon black was still wet, I splattered gold and silver to make the stars.

Azo yellow and titanium white. The head ornaments — silver. The earrings and necklace — phthalo green with titanium white and cobalt turquoise blue. The snake — yellow ochre, cadmium yellow medium and titanium white.

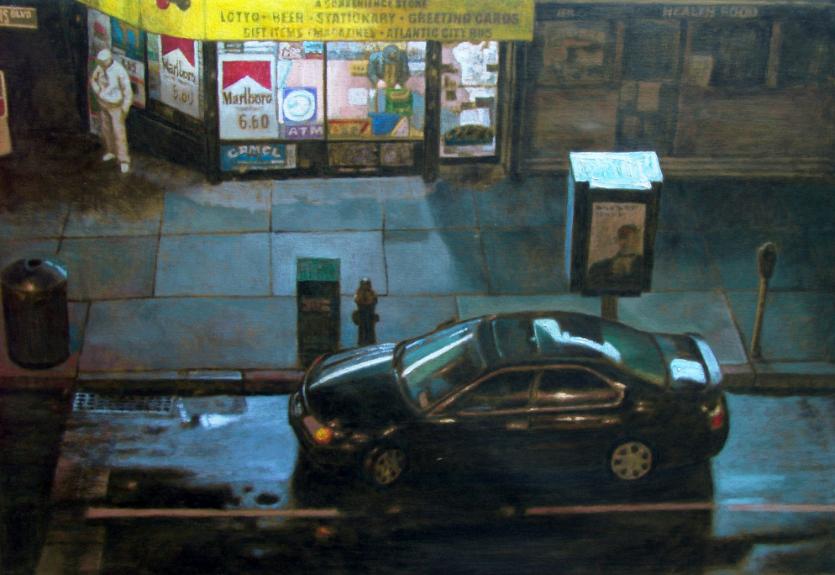

Queens Boulevard NYC Pedro Cuní Encaustic Cuní on canvas 20 x 30 in

Pedro Cuní is a visual artist, painter, and muralist with expertise in paint media technology, color theory, and pigments. Cuní has exhibited his art internationally and at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Spain. He is not only an expert in landscape painting, but also Cuní is known for his work with ancient painting materials, having conducted chemical research at Cooper Union on ancient Greek and Roman paintings. He currently collaborates with the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo, researching ancient Egyptian painting techniques.

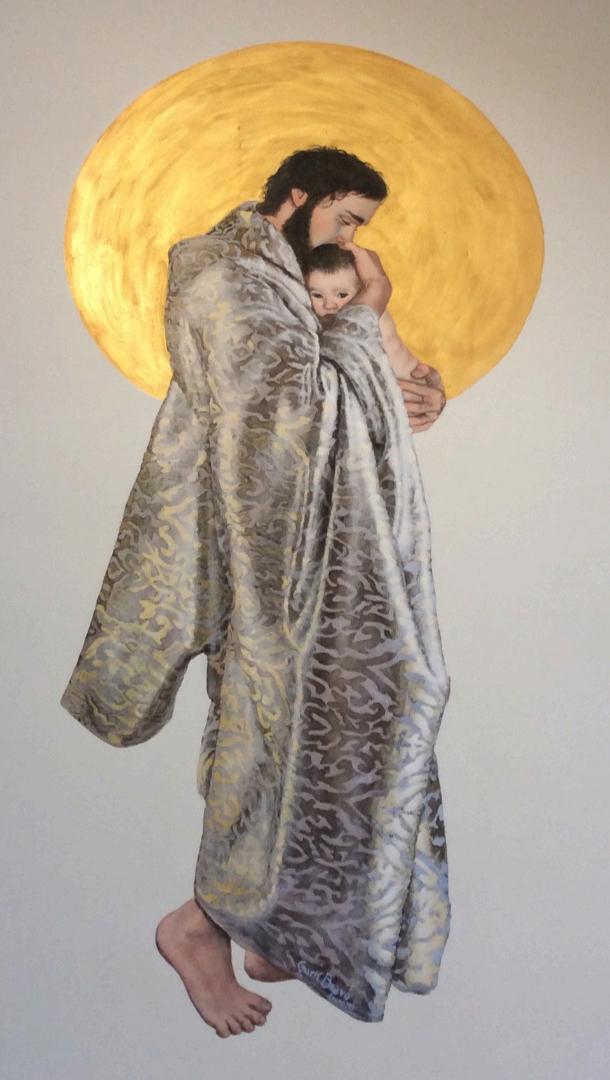

Mural painting by Pedro Cuní El Señor de la Misericordia Monterrey, Mexico, Encaustic Cuní on wall

the U.S.

My art by practice is multi-disciplinary with the primary focus lying in the territories of encaustic mixed media and textiles. I was introduced to encaustics in 2012. The first works I made were in a series of week-long encaustic masterclasses held annually with Patricia Baldwin Seggebruch in Australia. The works were made on small panels and were a response to personal and tragic happenings to my extended family. There was something about this medium that allowed me to express parts of myself that were so personal, private, and painful. The alchemy in expressing my thoughts and emotions with the medium enabled me to translate how I felt in a most profound way.

I have been described as an “encaustic artist working with purpose outside the conventional wax process.”

In my art practice I make work that gives voice to broader community and societal issues that are of importance to me. It is not so much that I choose to make a certain work; it is more that I am compelled to make the work. I am interested in language and how it is used to communicate and shape public sentiment. I think it is important to question and observe and think about what we are being told, how the message is communicated, and who benefits. The personal is political. Words matter. For these reasons, I make the work I do.

Queue Jumpers addresses the political language used in the public discourse surrounding refugees in Australia. Made in 2014, it is unfortunately as relevant today as it was then. This is one of the first artworks I made that featured text and the importance of language as a communication tool.

Using a pyrography burning tool to create the text and barbed wire imagery on the board, I sought to mimic the appearance of a branding-iron mark on livestock. An open flame was used to scorch and burn the board. A screen print of stacked boats on gauzy muslin fabric was embedded in encaustic wax.

I have always been sensitive to language. Language is often at the core of the political and social works I produce.

Environmental issues are explored in my practice and are also a feature of my textile-based works. The efect of coal mining and fracking on our water supply is a recurrent theme. This work was made in response to Australia’s largest gas producer being found guilty of lying six years ago about fugitive gas leaks in a local river system that feeds into the water catchment for Sydney. The power of mining companies has only increased during this time. The work looks at the contaminants in our water supply that are attributed to mining that make it unfit to drink and comments on the many billions of litres each year that mining drains from the water supply.

Bubbles in the Water began with text. It consists of wax layers, embedded with stitched teabags and other elements, color, and design detail that were added over the wax with Sumi ink and pan pastels. Sgrafto and accretion techniques are also employed in the work.

Bubbles in the Water Encaustic mixed media on board 32.3 x 25.2 x 1.4 in

Aesthetically pleasing, Abundance draws you in. A seemingly innocuous title, it is named in a manner that is at first inviting, but then under closer observation, is revealed to be descriptive of something more sinister.

The work is mixed media in nature — a flower garden of bright red geraniums, wildflowers, and blooms cover the large multipaneled work. Woodblock and lino prints on rice paper, illustrations on book pages, sketches on teabags, Batik techniques of text written with a tjanting tool, and illustrated Californian poppies on crimson-dyed silk are embedded in the work.

This painting was inspired by Rosie Batty, who was named Australian of the Year in 2015, and the significant conversation she started surrounding domestic violence.

Abundance began as a diptych and is now a triptych, but could easily be comprised of many more panels representing the unchanged statistic of one woman per week that is murdered at the hands of an intimate partner.

Abundance, Encaustic mixed media triptych on board, 25.2 x 96.9 x 1.4 in

Abundance, Encaustic mixed media triptych on board, 25.2 x 96.9 x 1.4 in

My work oscillates between that of witness to one of hope. There is a need for me to explore both aspects of my practice for my own wellbeing. Some of the subject matter that I explore in my work is very heavy and can be all-consuming. I have found that in order to be able to create these works, I must be outward looking and hopeful. I look to my immediate environment and celebrate those small, precious moments that bring a smile, are calming, and grounding. Finding Joy, a series of abstract colorful paintings, documents a personal journey of rediscovery.

The works seek to acknowledge the positive, the glimmers of hope, and the small victories each day brings. Joy is a state of mind and an orientation of the heart. It is what makes life beautiful. It is something deep within and it does not dissipate quickly. But sometimes in life when things are challenging, we must search very hard to find it once again. These works were painted at such a time in my life. This is the alchemy of working in encaustic. These themes were revisited during lockdown, and after the summer bushfires in Australia, with bird and bush imagery being adopted in more recent works.

Conversation I and II, Encaustic mixed media diptych on board, 32.3 x 48 x 1.4 in About the Author Kelcie Bryant-Duguid is an Australian multidisciplinary artist, who began working in encaustics after a week-long Introduction to Encaustics workshop with Patricia Baldwin Seggebruch in 2012. She was immediately hooked. She returned the following year for another week of encaustic masterclass and, later with some of the other artists in attendance, had a “playdate” exploring encaustic in sculpture. In 2014, she attended EncaustiCamp AU, where she expanded her encaustic repertoire to include book forms, textile applications, and monotype with U.S. tutors Michelle Belto, Sue Stover, and Judy Wise.

With a background in textiles, Kelcie embraces the scope that encaustic ofers to her art-making practice.

Kelcie has exhibited in solo exhibitions in local and interstate galleries and her work has been included in numerous group exhibitions. As an educator and facilitator, she has coordinated installations and public art projects with councils and schools in addition to teaching adult education classes.

A recent highlight was having her Finding Joy series of abstract works alongside her When I was a Bird series of encaustic paintings featured at Sydney Children’s Hospital in Randwick as part of their exhibition program.

Kelcie lives and works from her studio on the outskirts of Sydney. You can view Kelcie’s work at kelciebryantduguid.weebly.com www.instagram.com/kelciebryantduguid www.facebook.com/kelciebryantduguidartist

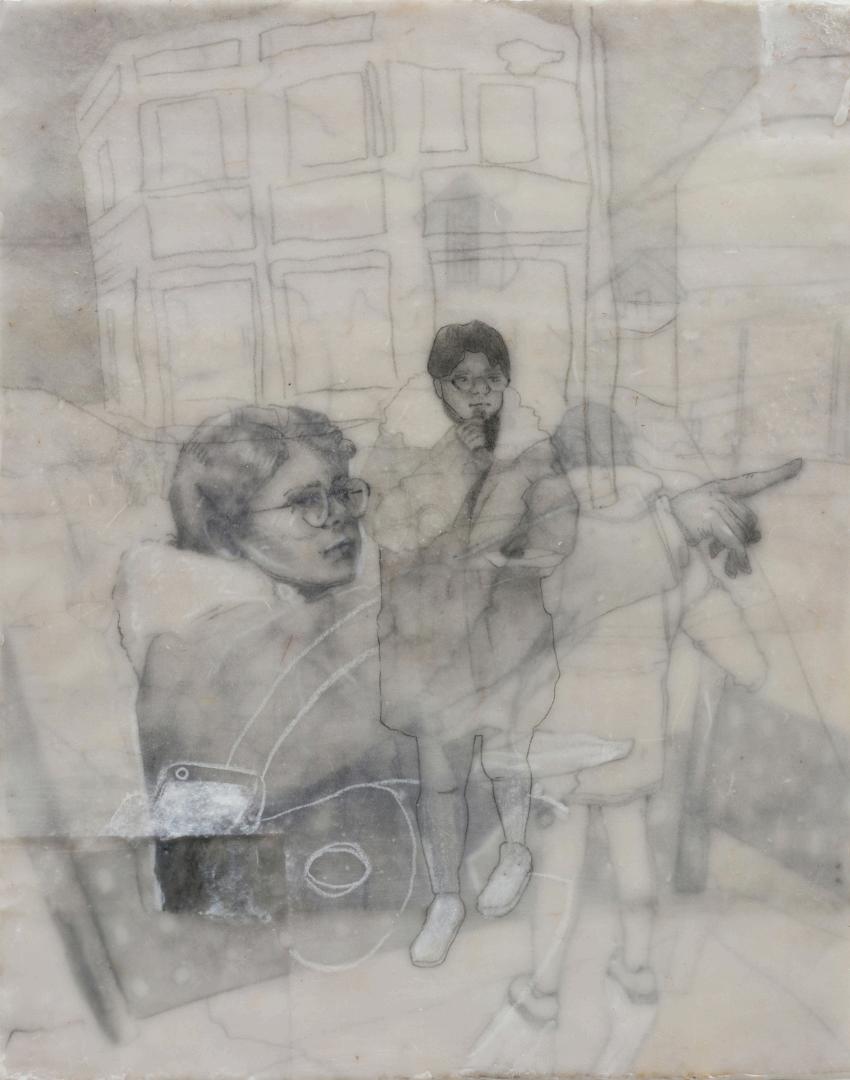

My process for encaustic begins not with the wax but with drawing. My passion for drawing predates my fondness for encaustic by nearly a decade; however, following my accidental discovery of encaustic, I began combining the two media early on in my experimentations with wax. The two media together in my work form intricately layered pieces full of surprises and unexpected moments of creation that I am endlessly fascinated by.

In recent years, I have focused my attention on topics of memory and intimate relations. Primarily depicting figures, I find myself drawn to imagery attached to personal recollections of people I know intimately.

Due to an inability to picture images in my mind, I have a poor memory. When I remember, I see lights and darks, vague shapes, and broad areas of color, but details often allude me. Out of frustration of constantly battling forgetfulness, my pieces aim to capture and preserve memories, no matter how significant or mundane, that would otherwise be easily forgotten. Each piece is thus a moment of permanence in a world of impermanence. This is reflective of my own concerns of memory, time, and ultimately the mortality of the people, the moment, and the memory depicted.

Walk

Encaustic, pastel, colored pencil, graphite, paper 24 x 18 in

My practice is akin to reverse archaeology as each piece is engaged in a process of fossilization. Instead of being a person to unearth memories from long ago in the present, I am preserving moments of the near past in the present to be seen in the future.

The term preservation is used intentionally as my process centers around the idea of embedding memories in the hardened and durable material of the wax in a similar manner as skeletal fossils are preserved over thousands of years in the unchanging material of bedrock. Much like the fossils in museums, each piece ofers a limited glimpse into a moment in time long gone.

My first solo exhibition took place in 2022. The title, The Tip of the Tongue, in reference to the common phrase one might use, “Oh, it’s on the tip of my tongue,” when attempting, but failing, to retrieve a thought or memory.

Encaustic, pastel, colored pencil, graphite, paper 11 x 11 in

The exhibition explored the space in which a thought exists somewhere between being remembered and being forgotten. Each piece was an attempt, although always lacking in some quality, to retrieve and preserve a personal memory.

My process for this body of work began with a chosen memory and relevant photographic references. In the early stages of each piece, I methodically translated photos into a series of drawings on paper, focusing only on details that were important to the recollection. Often beginning in black and white, I attempted to capture the essence of the memory. Once I considered the drawings finished, I embedded each paper one-by-one into the wax.

In between each layer of wax and drawing, I added pastel coloring. This is where I felt my true memory came into play. Since my true recollection of a memory is seen mostly as vague shapes and areas of color in my mind, the pastels acted as an added layer reflecting this experience. The palette choices of each piece were not meant to reflect the photographic references, but rather they were colors that felt true to my experience of the memory. Intuition guided me from this point as I combined both what I knew from the photographs and what I could abstractly piece together from my mind.

Downtown Reunion

Encaustic, pastel, pen on paper 18 x 14 in

Encaustic,

x

in

Despite my efort to permanently preserve these moments, memory is fickle and can not be easily contained in an entirety. As a result, the act of remembering and the involuntary manifestation of forgetting appeared side by side in this body of work. No matter how intentional I was while layering the drawings, the layers inevitably obscured one another. The more layers there were in a piece, the less details of each layer came through clearly; thus, the more story I attempted to tell, the less the story was recognizable. As a result, the wax in each piece exists within a duality, both as a preservative and an obscuring element balancing both the desire to preserve a memory and the acceptance of the inevitability of forgetting.

Desert Snow Encaustic, pastel, colored pencil, graphite, paper 24 x 30 in

Anne Feller is a figurative encaustic artist who works with themes of memory and intimate relations. She is based out of Boulder, CO, where she attained a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Colorado at Boulder in May 2021. She is a 2021 recipient of the Emerging Artist Grant from International Encaustic Artists and has been awarded several gallery prizes since 2019. In July 2022, Feller opened her first solo exhibition titled, The Tip of the Tongue, at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art in Loveland, CO. You can view Anne’s work at www.annefellerart.com www.instagram.com/anne.feller

I have never been able to figure out quite what occurs between the conception and the completion of a painting. I simply describe it as magic.

I’ve always wanted to be an artist and have followed my path with no regrets.

Most of my career was spent painting in watercolor, long before I ever saw an encaustic painting. While I believed for all that time watercolor was my medium of choice, I now think those years spent were my tutorial for painting in encaustic.

Painting in watercolor was definitely the platform of my process. With it I learned how to express my knowledge of seeing/looking/drawing, developing color, and orchestrating compositional elements in my own way. All the skills accrued have been transferred to my approach when painting with wax.

Both share transparency and fluidity, characteristics I understand and comfortably maneuver, even though the technicality used for each medium is specific.

Being a technique-oriented painter, when I become intrigued with a medium, I must explore its nature. How does it behave? How can I nudge it along to achieve a result that satisfies me, yet doesn’t interfere with its essence?

Rainy Dusk in SF II Encaustic on birch panel 24 x 18 in

Respecting the intrinsic qualities of a medium is of great importance to me. I want to be the alchemist, directing from my core the abundant potential of my materials.

I find it curious that my encaustic work puzzles some viewers. I’ve been asked how I paint realistically in encaustic and whether I incorporate photos into my paintings.

I do use photos for studio paintings as a reference only and often shoot specifically for this purpose.

As a practicing artist, I also make time to work from life as well: filling sketchbooks, working with models, and painting en plein air.

My studio work allows me to integrate all the elements that I determine to be crucial into my painting in a more thoughtful and deliberate way, rather than just my gut reaction approach to working from life.

I begin a painting by drawing with oil pastel onto a white gessoed birch panel; I suspect this is a connection to working on watercolor paper.

I then apply a thin layer of clear wax, fuse, and repeat. And so the painting begins….

I am an admitted control freak when working, although I’m not really drawn to hyperrealistic paintings. My goal is to achieve a more painterly result.

Sometimes I think that my devotion to painting what I see hinders the outcome, which is why working in encaustic has been so liberating.

I allow myself the luxury of fussing over the application of pigment to my hearts content. But when I fuse, I must accept the results, which are often extraordinarily diferent from what I have painted. The melting of wax transforms the painting in unusual ways.

I find it incredibly gratifying to torch all that hard work, knowing full well that the results may involve the good, the bad, and the ugly.

First Cup Encaustic on birch panel 9 x 12 in Also featured on the back cover

I feel obligated to say that fusing is an art of its own and can be finessed to honor the nature of both wax and fire, as well as my own sensibilities.

I believe that fusing is equally, if not more important, than painting with the wax. I find it quite physical, even dance like. I place my painting on a Lazy Susan type of platform. While slowly caressing it in a circular motion with my torch set on a low flame, I am also rotating the painting with my other hand. It is a task that cannot be rushed. If the wax is melted with excessive heat, it will completely liquefy, not my result of choice.

What takes place when I’m working is nearly impossible for me to describe. I disappear when I paint. I don't have conscious thought. I'm unaware of my body floating in a time warp. I exist and my painting exists; that’s it. All else is an intrusion. I evaluate my work only when I’m not actively painting. Most often when I find something distracting, mysteriously, answers come to me.

There are many times when I wonder how I know what to do, or how to do it. It lies within me, unspoken. It’s transformation, magic, alchemy.

Rain in London I Encaustic on birch panel

San Francisco Bay Area native Karen Frey paints in a representational manner, in both encaustic and watercolor. Her work is subtly narrative and technically adept, distinguishing it among realistic painting. Her paintings hold a finesse and polish that reflect her 50 years of experience and practice as an artist. Frey has a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the California College of the Arts. She lives and paints in Oakland, CA. Her work is inspired by all the things in life that speak to her in a visual sense, whether they be environmental or those around her who influence.

She believes that artists gravitate towards certain media in a way that reveals their logical path of problem solving. She spent many years practicing how to realize an image using wet-into-wet watercolor techniques, simply because it spoke and made sense to her. For the past 13 years, she has focused on expressing imagery with encaustic, a significantly more challenging medium. It shares many similarities relative to Frey’s methodology. You can view Karen’s work at karenfrey.com

My sculptural practice began as an outlet for stress and frustration, during a period when I had neither time nor space to paint. It was an accidental form of therapy, that soothed my mind and kept my hands busy tearing paper and diving elbow-deep into papier-mâché paste. To me it makes perfect sense that art born of stress would take an introspective turn. By the time I turned that first ball of paper into a figure, I was out of the stressful situation and ready to experiment with my encaustic paint.

Since that time, sculpture has taken on a life of its own, separate from my painting practice. It is more rooted in expressionism than realism, allowing me to explore nature, personal history, mental illness, culture, and injustice. Over time, I have found meaning in various types of paper based on physical properties such as strength, translucency, and its original use. The symbolism of the material is likely not relevant to anyone but me, but I can only hope that the finished work will spark the viewer’s imagination.

Papier-mâché, encaustic, cold wax, wire 40 x 10 x 10 in

For me, the muse can be the written text. When I am layering papier-mâché, I am not only manually “reading” or feeling the material to manipulate it, but also, quite literally, reading the material as I work. The text and images influence my artistic direction and emotional responses, which are visible in the finished work. As I continue to construct the form, I add found materials that resonate with the piece.

A good example of work influenced by the medium is Trespassing. It was sculpted from newspaper articles (surrounding the #MeToo movement) and packing paper. In my visual vocabulary, packing paper symbolizes protection and safety. After using my Dremel tool to carve the face, I coated the sculpture in cold wax rather than encaustic. This minimized translucency of the paper, which could have confused the eye by allowing text to show through from the other side. I added found metal objects and built a knothole in his side, in which a secret object could be hidden or displayed.

Trespassing (Boundary Lines)

Papier-mâché, cold wax, packing paper, found metal objects 20 x 14 x 8 in

The opposite is true on Pluto’s face: I used opaque white encaustic to coat his face and model parts of his ears, eyelids, and lips. The sculpture’s base has only clear medium to highlight the papier-mâché, and the planet’s coloring was achieved with scraped-back accretion.

Abundant Mother (detail)

Papier-mâché, encaustic, phone book pages, found stone, metal 23 x 8 x 8 in A Small Matter of Gravity (Pluto 2.0) Papier-mâché, encaustic 18 x 10 x 10 in

On Abundant Mother’s face, I used a heat gun to force the encaustic into the fibers until the excess ran of, in order to make the paper translucent. I intentionally left the paper in this raw, natural state and added no extra layers of clear medium for depth and shine. I love the way this emphasized the paper fibers instead of hiding them.

Like many artists, music inspires my creative mood in the studio, and sometimes it actually finds its way into my work. We Didn’t Start the Fire was inspired by the social commentary in the Billy Joel song.

I added a mix of burnt materials to further the idea of “fire” and used encaustic color to hint at flame on his wire beard and the top of his head. The sculpture’s matchstick shape was just a humorous after-thought.

We Didn’t Start the Fire Papier-mâché, encaustic, wood, metal, bark, wire, pebble 27 x 9 x 9 in

The Remembering Tree, Right Papier-mâché, encaustic, carnauba wax, packing paper, mulch, obituaries 66 x 14 x 15 in

The Remembering Tree began as a study of the nourishment provided by dying trees to birds and bugs and bacteria, which then fertilize the soil for the next generation. After some soul searching, I decided to adhere collected obituaries (normally deemed of limits to my papier-mâché) on the hollow of the tree, and it became more of a Celebration of Life than musings on the cycle of life.

Other than in the hollow, the newspaper ink is only distinguishable in the deeply carved wrinkles on her face, a testament to the joys and sorrows she experienced in life. (Isn’t that what we tell ourselves about our own wrinkles?)

“Horn of Plenty” mushrooms flourish on her head, and the paper “bark” was stained with dark brown furniture wax to give the feel of age and dampness.

To begin The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, I brushed layers of clear encaustic medium onto the papier-mâché, then blasted it with the heat gun fully to saturate the paper. I then applied thick layers on the dome of the head, allowing me to create a consistent depth of wax when I scraped it back.

The haunted look of the cursed mariner was achieved with a blow torch; I hollowed out and scorched the facial features before painting them. I hand formed the tubular coral structures and built-up accretion to create algae, moss, and seaweed. I added seashells and tree bark that I had collected. His scalp, which reminds me of a distant view of Earth, is translucent from hot wax saturating the fibers, showing wonderful organic patterns. Like the Earth, his body has become a living host for the marine life sculpted from encaustic wax.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Papier-mâché, encaustic, found seashells, bark 13 x 10 x 10 in

In Reforestation, I examined many ways that trees are processed into usable materials, and I then reassembled a “tree” from them. Is it still a tree if it has been pulped, processed, and reassembled from lumber, cardboard, paper, and resin?

This piece includes a variety of paper types and techniques: common papier-mâché strips, wadded and compressed paper, machine-shredded paper cast into “particle boards,” and a combination of these laminated into a “log.” The encaustic paint begins low on her trunk, mostly transparent, and grows more opaque as it reaches the tree’s crown of new growth. Incised lines in the green encaustic hint at leaves.

Deanne Row grew up near St. Louis, MO, in a family of artists and musicians, which influenced her interest in the arts from an early age. While in college, she worked as a traditional candle carver on the Savannah Riverfront; little did she know that wax would come back into her artistic life much later. To the horror of her parents, she dropped out of the Savannah College of Art and Design halfway through her B.F.A. program, with only one painting class under her belt.

Deanne now works from her studio in St Charles, MO. She has been concentrating on developing her sculpture practice, but still paints whenever she can. Recent solo shows include Myth or Memory (canceled due to Covid); The Ship of Theseus, at the St. Louis Artists’ Guild; and the combined works of these shows at the Quad Cities Airport, Moline, IL. She has received IEA’s Emerging Artist grant and an Artist Support grant from CERF+ to improve her studio. Deanne was humbled by an invitation to exhibit alongside many of her encaustic and cold wax heroes at the Texas A&M Wax Applications Invitational. You can view Deanne’s work at www.GalleryRow.com www.instagram.com/galleryrowfineart

I started my career in a very remote part of Oregon, along a river watching birds construct a nest. That led me to becoming a working Studio Artist and Instructor, which I have been for the past 37 years. Of those 37 years, I have been playing with wax for 21 years.

My work is known for its eccentric approaches both in design and the materials I choose to work with. My process and approach are sophisticated primitive, my studio, a lab of sorts. I usually work more in the outside environment, where some crazy ideas seem to brew. I set things on fire, pound things with rocks, rip and tear things apart to either weave or stitch them back together, paint, and mix unlikely items together.

There is always a couple of subjects going at the same time, which allows me to move around and ingest the dialog of the materials at hand.

At least 85 percent of the materials in my sculptures and objects are designed from items I collect, repurpose, or harvest from various locations. Items in nature, the ocean, and found objects are everywhere.

Woven reclaimed construction wire off job site, skinned with layers of paper and wax medium, oil, found objects 11 x 8 x 5 in

Wall hung personal talismans that the owner can whisper and hold secrets, dreams or prayers.

collected drilled objects off my beach, woven object of found objects 16 x 16 x 8 in

I currently make my own wax from local hives that I get from farmers, then mix in Damar, as it allows me to adjust the outcome of the hardness of the wax, and I like the extra debris from the wild wax. While I do strain junk out from time to time, I like the efect of the raw product.

Wax crossed my path in 2000. It was just by chance when I walked into a gallery to view an exhibit of paintings. The paintings were of wax, and they were amazing.

In my own work at this time, I was exhibiting in fine art & fine craft shows, invitational exhibits, and museums. I had not seen anyone use wax. I spent the next hour and a half talking with the gallery owner about the artist and his process.

Then I asked the big question. I asked the gallery owner, "Have you ever seen wax used in 3D?"

He was quick to say no, and then he questioned how that might be possible.

Rock the Boat

Woven boat form, skinned with layers of burned vintage Korean romance novel pages with encaustic, sea kelp, hand stitched details, stitched and drilled collected beach stones

9 x 22 x 10 in

I chased down where I could get wax, I ordered five 333 ml medium blocks from R&F, hair brushes, and a heating element. I already owned a torch. I did a fair amount of reading on the subject, and then it was time to jump in.

I had some trial and error moments, but used them as learning opportunities and marched ahead using panels and hand structured objects. I was quite comfortable layering a deep depth of wax on both of these types of substrates.

Handwoven of reclaimed construction wire off a job site, skinned with layers of burned paper and encaustic medium, bound with raw hemp cording, found objects and Hag stone collected off my beach 18 x 8 x 6 in

I was then on to scraping, carving back, and embedding objects. Finishes could include attaching various materials using methods like basic stitching, or using a fish-netmending technique. Rocks, metal, and various items from nature were employed as surface elements. Using wax allowed my surfaces to be marked up and dirty, which I find inspiring and exciting.

Handwoven cage, entrapped encaustic embedded object with bones and woven mouth, thread with collected and drilled beach stones 15 x 8 x 6 in

I do not direct the outcomes of my designs, and while a fair amount of my work leans towards "artifact" ambiance, it is truly the collected items that run the dialog of how things are going to go.

To be honest, there really isn't enough words to write about all of my methods.

Every item is changed in one form or another. Some people may find my processes obscure. I am curious, sometimes clever. In general, I keep in mind that humans are the makers of things, and we all carry this DNA. It's original and it's authentic.

Mixed materials woven and stitch form, filled with mixed media woven and stitched objects of paper and encaustic embedded with various found objects of bone, teeth, beach glass

20 x 7 x 6 in

Woven and stitched boat frame, skinned with layers of paper and wax medium, oil stick, filled with three-mixed media woven objects of collected materials and wax 28 x 14 x 12 in

Work in process details of a boat bottom and side

Shannon Weber is a working studio artist and educator working in 3D-fiber sculpture. Her attraction to working with fiber is in the options it presents in its ability to shape-shift when using a variety of reclaimed materials and found objects. By applying ancient techniques and transitioning to contemporary designs, she achieves her desired efects by using a mixture of repetitive layers, weaving, stitching, cold connections, painting, and encaustic. These multiple applications make it very easy to blend metal, wire, coastal debris, rubber, and organic materials of all kinds. Each layer of material mixed with diferent techniques begins to build structure that gives the objects and vessels their form and opens doors for detailed surface design embellishments.

Shannon's works have received numerous awards and are held both in public and private collections, along with being seen and featured in 38 publications worldwide. You can view Shannon’s work at www.shannonweber.com

Artists (IEA), IEA's European

Arts in Mulranny, Ireland, and Enkaustikos.

An Intimate Encaustic Retreat on the edge of Clew Bay Co. Mayo, Ireland

Imagine yourself at IEA's intimate retreat in Ireland with a small group of artists and a shared experience (demos, panels, and talks). Share meals and get to know your fellow artists at the Welcome dinner, continental breakfasts, and lunch bufets. Join us for a musical Pub evening with great food, songs, and “craic.”

Dancing is encouraged!

Attendees can also sign up for one of multiple workshops being ofered pre-retreat on Wednesday and Thursday, October 11-12, 2023, and post-retreat on Tuesday and Wednesday, October 17-18, 2023. And attendees who are new to encaustics can sign up for a pre-retreat beginners workshop. Pre-retreat workshop-only attendees are invited to join the retreat attendees at the Welcome Dinner. Post-retreat workshop-only attendees are invited to attend a fun social event on the last night of the retreat.

And everyone is welcome to attend the IEA Juried Exhibition and artists’ reception.

Mulranny is a small seaside village on Clew Bay in Co. Mayo. It is located at the dramatic western edge of Ireland, the end boundary of Europe.

Here, land and sea meet at the threshold of a powerful creative adventure. Croagh Patrick, Ireland’s holy mountain, rises majestically from the sea on the opposite side of the bay. It is here that the ancients as well as the modern day pilgrims have climbed the steep path to the summit. You can see the small chapel’s reflective glint on the top.

This is sheep country and below the village the sheep stand still as the tide comes in over their grazing patch on a salt marsh. They have learned to patiently stand and wait for the waters to recede so they can once again graze the salty grass. The rhythm of life is dominated by these tides, flowing over the white sand beaches and then leaving in hasty withdrawal to the vast Atlantic Ocean.

There will be an opportunity to do some sightseeing mid week with our fabulous Tour Guide Colum, who will regale you with stories (some of them, true!) about the area, OR you may wish to avail yourself of the open studios time at one of our gorgeous encaustic studios.

The retreat and exhibition will be held at Mulranny Arts Campus, the workshops will be at the EOM campus and the Mulranny Arts Campus, and all retreat accommodations will be close by. Transportation will be provided for meals out and our sightseeing days.

Studio at EOM

A Virtual Conference Package is included for free for Retreat and Workshop attendees. For Virtual only attendees, there is a minimal charge.

Virtual content will include product and technique videos, instructional material (digital books, handouts, and patterns), a short video walkthrough of the exhibition, and retreat videos (edited videos from a few of the demos, talks, and panels).

Registration for the retreat and workshops will open in mid January 2023. Be sure to check the International Encaustic Artists website for updates on when registration will open.

Retreat space is limited, and we will start a wait list once all retreat spaces are filled.

Creativity does not exist in a vacuum. With that being said, artists thrive as creators in their studios, but they also need interaction and engagement with other inspired people in the real world. International Encaustic Artists (IEA) is great at helping connect you with other artists in the broader sense so that local Wax Chapters can bridge the gap closer to home.

Chapters create immediate safe spaces for an intimate community and act as a collective support system. While individual Chapters remain under the wing of the IEA, they have their own mission and values that are created and maintained by members. No matter where you go, these groups may have similar origins, but they will look and operate diferently. Some Chapters focus on education or artistic support, while others collaborate their eforts to produce local art exhibitions or host critiques.

According to Chapter President, Shelly Jean, the Florida Wax Chapter “grew out of necessity.”

They started as a group of artists who were interested in learning more about encaustic painting. Since forming a Chapter in 2017, they continue to support one another, grow artistically, and share their encaustic painting passion with the public.

NorCAL Wax is a new IEA Chapter forming in Northern California. Inspired by the high energy and camaraderie felt at the 2022 IEA Convergence Retreat in Morro Bay, CA, Karen Buttwinick and I took the first steps in creating our own local Chapter. Our goal is to build connections while working collectively to create exhibition opportunities, educate ourselves through shared resources and field trips, and help each other grow artistically and professionally through speaking events, art critiques, and other experiences.

Lora Murphy and Bettina Egli Sennhauser are starting a European Encaustic Chapter. In addition to nurturing their new Chapter’s website, they are kicking-of their activities by cohosting the 2023 Encaustic Retreat, in collaboration with the IEA and the Mulranny Arts Center in Ireland. The Retreat is sure to be a success with artist talks, demonstrations, painting workshops, discussion groups, open studios, vendor rooms, and much more. Mark your calendars: the Retreat is scheduled for October 12 - 17, 2023.

While this may all seem like a lot, the best thing about starting a new Chapter is that you are not alone! As the Membership and Chapters Director, I am here to help you through the process and answer all of your questions. In addition, there are new pages on the IEA website to help you start your own local Chapter.

Imagine your encaustic or cold wax art experience with support on all sides. “Fullness” was the word that appeared when I looked up antonyms for the word “vacuum.” I think that a wax Chapter is the perfect way to fill a vacuum, don’t you?

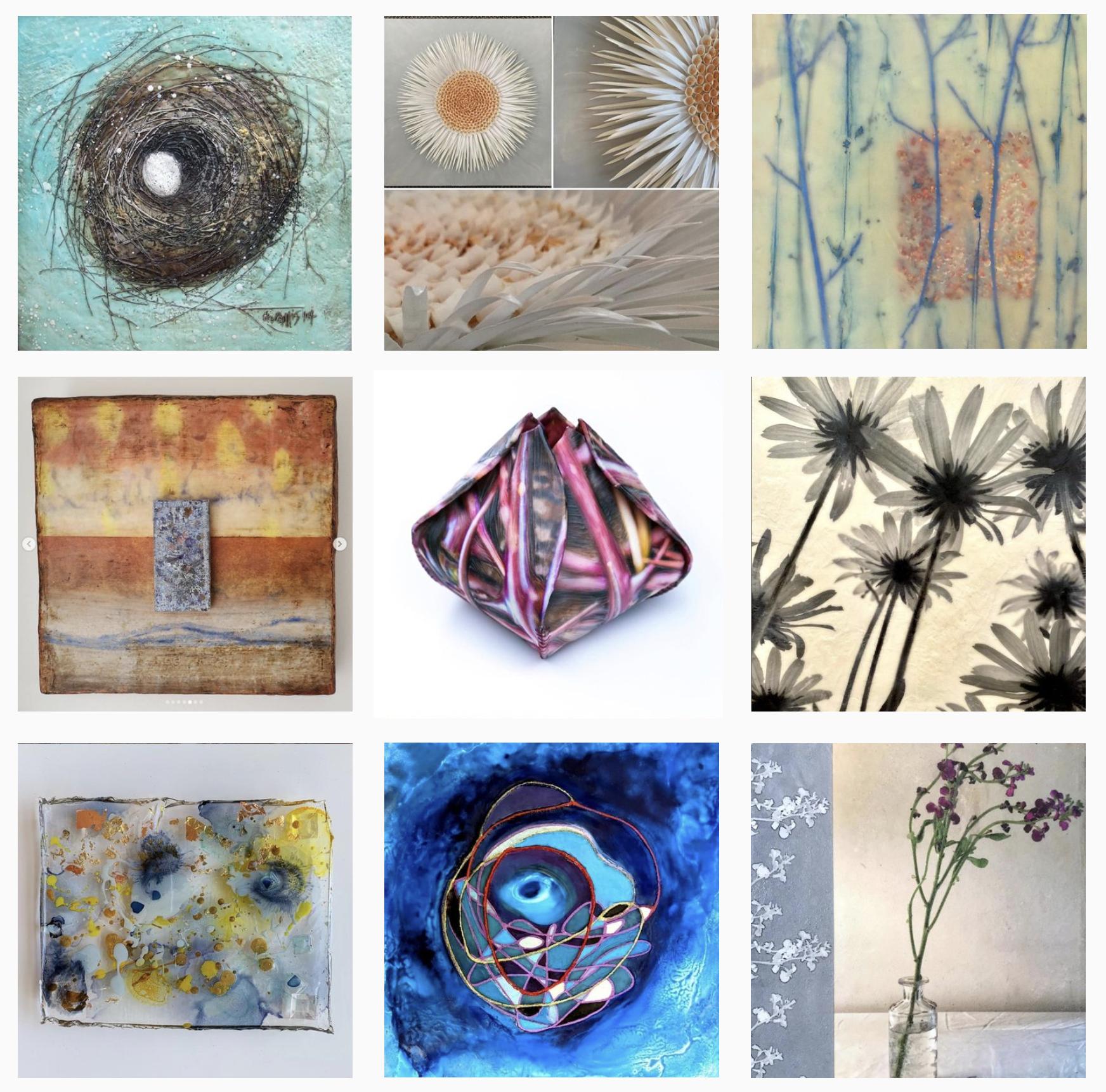

We take great joy in shining a spotlight on IEA members’ work through our active and vibrant presence on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest. Our goals are to:

• highlight and celebrate the work and accomplishments of IEA members;

• announce new opportunities;

• engage and educate people about encaustic arts; and

• foster a sense of community among encaustic artists.

Have you shared your current social media handles with us? We suggest that you log into your IEA profile to check that your social media information is up-to-date. We also ask members to grant us permission to share their work by signing a terms of usage permission form.

Through our @iea_encaustic account, we regularly share work of artists who have granted us their permission. With more than 3,500 followers, our posts receive lots of attention and interaction.

We also invite members to tag us in their posts. Use these two hashtags whenever you post:

can also follow these hashtags to see lots of inspirational posts by other artists working in wax.

As

We

Emma Ashby

Peter Blackmore

Joe Celli Cindy Clark

Alison Fullerton

Sally Hootnick

JuliAnne Jonker

Deni Karpowich

Director, Regina Quinn, with

Europe, and the United States,

Birgit Kentrat

Gina Louthian-Stanley

Ursi Lysser

Megan MacDonald

Judy Pickett

Caryl St. Ama

Melissa Stephens

Trudie Wolking

IEA