Wax Fusion

Regina B. Quinn President Grants Director

Lyn Belisle Vice President Editor, Wax Fusion

Isabelle Gaborit Social Media Director

S. Kay Burnett Executive Editor Wax Fusion

Front

Michele Randall Secretary

Rhonda Raulston Tech Director Treasurer

Mary Jo Reutter Membership & Chapters Director

Melissa Stephens Exhibitions Director

Amanda Pierce Editor Wax Fusion

Current trends in encaustic art reflect a vibrant transformation of the medium. Once celebrated mainly for its texture and luminous surface, encaustic is now being reimagined as a language for complex themes and experimental practices. Artists are increasingly incorporating environmental advocacy, sustainable materials, and interdisciplinary techniques that merge wax with sculpture, installation, digital media, and unconventional surfaces.

This evolution expands encaustic’s expressive potential and challenges traditional boundaries of form. From Matt Tommey’s wax-infused woven sculptures to Susan Russell Hall and Terry Rishel’s large-format digital work, and Margaret Byrd’s botanically printed fiber pieces, today’s encaustic artists are redefining what’s possible.

The sparkling originality of our When in Rome exhibition award winners reflect this expansion. Anne Feller, Jane Cornish Smith, and Regina Quinn embody the medium’s evolving potential. Feller explores memory and impermanence through wax’s fluid unpredictability. Smith turns found litter into urgent environmental commentary. Quinn reflects political and emotional unrest through shifts in palette and form.

Each artist in this issue pushes encaustic beyond technique, using it as a vehicle for reflection, response, and change.

We hope you enjoy this New Trends issue of Wax Fusion and feel inspired to push your work forward through bold experimentation. As always, we welcome your feedback at WaxFusion@International-Encaustic-Artists.org. This journal is created for IEA members but is also free to the public—feel free to share it widely.

S. Kay Burnett

Lyn Belisle

Amanda Pierce

For the Love of the Lake by Jane Cornish Smith

Styrofoam, plastic straws, partial bottle cap, encaustic, cold wax/oil, and mica powder

5 x 7 x 4 in

Margaret Byrd

Curiosity and experimentation form the foundation of any artistic practice, fueling the evolution of creative expression. Such is the core of my journey towards encaustic art.

My first experience with melted wax came from a tattered box of crumbled crayons in my art school studio. Inspired by Jasper Johns, I was captivated by the textured interplay of layered paper and textiles in his encaustic work. With few resources to explore this ancient art form, I improvised with simple materials, eager to experiment, embedding fiber within translucent layers and manipulating images through depth and opacity.

Though I later shifted toward an ephemeral practice—freezing organic matter and natural fibers in ice during my final years of study—I couldn’t ignore the parallels between encaustic medium and the fleeting, ethereal qualities I sought in my artwork.

Ash

Encaustic and botanically printed cotton on panel 12 x 12 x 1.5 in

Tara

Encaustic and botanically printed paper on panel 6 x 6 x 1 in each

Returning to the studio two decades later to expand my work with ice and site-specific installation, my artistic focus had deepened to include a commitment to sustainability and a dedication to working exclusively with organic materials. Due to the ephemeral nature of ice, I was determined to find ways to extract color from the earth so it could safely return to the soil as the installations melted. To do so, I immersed myself in learning the slow, meditative process of brewing colors from leaves, roots, and flowers, which inevitably led me to dyeing natural fibers with their pigments. While I found endless inspiration with every subtle hue in my dye pot, my initial curiosity of the unique ability of wax to preserve and enhance translucency kept calling me back to encaustic.

The shift from ice installations to encaustic art provided a way to encapsulate organic materials—fresh leaves, natural fibers, and botanical prints—within layers of beeswax. This transition allowed me to move beyond ephemeral, time-based works, creating more enduring pieces while still maintaining the sense of fluidity that had always been central to my practice.

As I sought to blend these materials, I explored various ways to create printed designs on fiber with traditional indigo dye resist processes such as shibori stitch and soy lime paste that resulted in a sumptuous palette of deep blues, warm neutrals and linen whites. During an immersive artist residency in the high Andes of Peru, I expanded the printed elements with experiments of tara and eucalyptus leaf monoprints on paper and iron-modified botanical prints on silk and cotton. With a rich inventory of fiber kissed by nature’s palette, I shifted my studio from simmering dye to molten wax.

Working with botanical pigments and fibers in encaustic painting can be challenging. Plant-based prints and colors are less predictable. They shift subtly depending on pH, exposure to light, or even the mineral content of the water used in the process, but I find this to be part of their magic.

My first attempts were experimental and unpredictable. I embedded pieces of botanically printed silk and cotton into layers of encaustic medium, watching how the wax altered the fabric’s color and texture.

Gumnut

Encaustic and botanically printed paper on panel 6 x 6 x 1 in each

Some results were stunning, the wax enhancing the depth of the prints natural variations. Others were frustrating with fibers curling in unexpected ways or colors dulling under too much heat. Rather than forcing control over the materials, I learned to embrace their natural variations.

As my technique evolved, I realized I was creating a bridge between two artistic languages that had defined my creative life. The encaustic process, with its heating, cooling, and layering, felt akin to the dyeing process I loved, where time and patience revealed the most unexpected hues.

Through this inaugural exploration into encaustic art, blending botanically printed fibers with beeswax, I created the “Leave It” series. This collection comprises 30 ethereal artworks, each featuring naturally printed leaves embedded within wax, reflecting a commitment to natural materials and sustainability. Leave It

Compilation

Encaustic and botanically printed fiber on panels

Encaustic and shibori stitch indigo on panel, 6 x 6 x 1 in

This method creates a translucent quality that enhances the depth and texture of each piece, showcasing the inherent beauty of natural elements and aligning with a dedication to an eco-friendly art practice. Every piece created becomes a reflection of the environment from which it came—a collaboration with the earth that I’m forever grateful to have.

While my art has always been deeply rooted in my love of the natural world, it wasn’t until I fully embraced nature’s colors, textures, and its ephemeral beauty, that I felt my work had found its true voice. Integrating natural fiber and botanical color into my encaustic art practice was not just an aesthetic choice; it was a way of honoring the earth through my creative process and cherishing its sacred gift of color.

It has been thrilling to experience the intersection of tradition and experimentation, weaving together past and present, fiber and wax, Earth and art.

Encaustic and soy lime resist printed indigo on cotton on panel, 8 x 8 x 2 in

Encaustic and soy lime resist printed indigo on cotton on panel, 8 x 8 x 2 in

Bud

Encaustic and botanically printed fiber on panel 8 x 8 x 2 in

The breathtaking Pacific Northwest surrounding Seattle is where Margaret Byrd calls home, but her artistic praxis spans the globe with a ‘studio’ built on mobility and designed for her nomadic soul. Graduating from the University of Montana with a BFA in Photography, she discovered her love of mixed media and installation along the way and continues to explore both artforms in her studio today. Wanderlust has kept Margaret traveling extensively where vast landscapes and naturally derived colors have inspired her artistic focus and visual aesthetic. Weaving her creativity into a daily practice, Margaret is currently working with organically dyed fibers and encaustic.

Margaret’s work has been selected for juried exhibitions in the Pacific Northwest, shown in gallery spaces in Mexico, Svalbard, New York and California and purchased for both public and private permanent collections. Returning to the lens in 2020 as a content creator, Margaret shares her creative journey on her YouTube channel, Margaret Byrd: Color Quest, building a community to celebrate organic color through hands-on tutorials and vlog-style film dedicated to nature's palette.

You can view Margaret’s work at www.margaretbyrd.com www.instagram.com/moonbyrdie www.youtube.com/@MargaretByrdColorQuest

Passage

Encaustic mixed media, 50 x 50 x 2 in

Susan Russell Hall & Terry Rishel

In December of 2018, we were introduced by a mutual friend who saw the potential of pairing our work: Susan’s encaustics and Terry’s photography. Our vision exploded into large format art with archival, vintage subjects that one might find on some ancient wall or forgotten painting. The subjects of our work include florals, parks, forests, and abstracts in nature: areas both us explored independently.

Our love of photography, encaustics, and paint blend to create these exquisite works. Merging Susan’s encaustic work with Terry’s photography, we focus on minute details of a scene, allowing natural light into space and the viewer to feel the creation.

Moving into our seventh year of collaboration, we continue to unite our artistic talents as we create magnified views of a dahlia in bloom, a meandering path to an unknown journey, or an antiqued vision of a garden rose.

Our work

We focus on images from everyday life portrayed subtly and diferently through light, angle, and perspective.

We are inspired by the simple things often overlooked in our busy lives and strive to capture the spirit of a scene, inviting your heart and imagination to wander into the painting.

We don’t need to go out and find big, giant grand scenes of huge mountains and oceans. These topics have already been done and done so well that you really can’t improve on these. So many of us take for granted what we walk by every day. Let’s take a moment to walk down a forest path, in a park or garden. There’s a wonderful world surrounding us.

Enchanted Gateway

Encaustic Mixed Media

35 x 44 x 2 in

Next page

Morning at Lakewold Gardens

Encaustic Mixed Media

42.5 x 52.5 x 2 in

From the moment we walk into Lotus Studio, we have developed the habit of stopping and studying yesterday’s work. From that moment, discussions and slight changes in direction seem to constantly emerge.

The word encaustic comes from the Greek word “to burn in.”

The surfaces of our artwork have a depth…one that resembles polished stone, cracked pottery, or ethereal space.

Through trial and error, we have perfected process steps to create our images. To be fair, there have been many failures and challenges to work through.

Our artwork starts with Terry’s original photography.

Whether it’s in a garden or a forest, wherever it is, there is always something there that inspires us to select it. Every piece created is one of a kind, so this step is critical.

We are very careful what image we select out of the thousands that we shoot. We really study them. Only if there is something in the photography that really takes us to another place will we use it. There has to be magic in there. Unless there’s magic, we won’t go forward.

Our process consists of using custom textured archival paper mounted on handmade custom panels. Each individual artwork is altered and manipulated with a variety of materials and techniques, then painted with oil paint as the vision we have for it continues to emerge. The final painting may have little resemblance to the original photograph.

We are continuing to search for the soul of the image. We listen to the image. It tells us what it wants to become.

We keep this process going…our aesthetics line up perfectly. We don’t question what the other does. That’s where the unlikely collaboration works. Two artists working this closely together is almost impossible to find.

For challenging pieces, we leave them in another room for a while. Then, we’ll look at it and often we’ll revisit the artwork. At some point we say our favorite words, “Stick a fork in it!’ It’s over, it’s done.

Each painting has four hands on it. We paint on it together. You don’t usually find somebody whom you trust that much that you will be able to create the same painting at the same time.

When we paint, there’s a realism that’s extending a hand to the viewer, so they’re comfortable entering the painting. We’re going beyond reality for the soul and the spirit.

When you look at our roses (or anything we’re doing), there is a depth and layering that lets you get lost in the shadows, the undulations, and the three-dimensionality of the work. We are always trying to go for that depth, so that it feels like our pieces are lit from behind.

When we study a forest or a park, perhaps 90% of them start in fog because fog adds drama to a piece. Then, as we burn the piece and as we paint, we manipulate the scene, often vignetting it.

Next page, Studio portraits of Susan Russell Hall and Terry Rishel

unique, unlikely approach

Our techniques create a three-dimensional feeling using shadowing, torch burning, dynamerging of images (2, 3 or more in a single piece), and shadow barking (cracking/ highlighting the image). We created these terms specifically for our work.

We strive to discover and uncover the soul, spirit, mystery, and magic of an image.

Portal Forest

Encaustic Mixed Media

42.5 x 52.5 x 2 in

Next page

Timeless

Encaustic Mixed Media

40 x 61 x 2 in

I started showing Susan a lot of these florals, not the front of the rose or dahlia but the backside. I find it as exciting as a front. So, I don’t know why more people don’t study the backside.

That’s one of the reasons that this collaboration is so important. It’s telling people “Don’t look at what’s on the surface.” Flip it over, look, and dig a little deeper. Look at things from a diferent perspective. Be open. Have that sense of wonder.

Now, as the world’s so divided, it’s important to say there’s another side. You may just be looking at one side, and there’s a huge amount of beauty on the other side. It’s opening up your mind and your heart and seeing things from a little diferent perspective. We all need to do this work and hold that place of compassion and curiosity.

In collaboration with Susan Russell Hall and Terry Rishel, we would like to thank the following people for their contribution:

Rock Hushka, Kristin Johnson, Maggie McGuire, and Erik Schultz. We are so grateful for you all.

Also featured on the Front Cover

Susan Russell Hall has worked in a number of mediums, her focus over the last twenty years being encaustics, the ancient art of layering wax and incorporating pigment.

She began in 1977 with her first solo show at the University of Washington Women’s Cultural Center. She started as a medical illustrator in 1979, and her work is widely published in numerous medical books and journals. Over the years, she has documented more than 6500 individual heart surgeries. These intricate works of art are created by using charcoal, graphite, and colored pencil. Susan also explored other mediums, such as acrylic and oil painting, and eventually pyrographs, the actual art of painting with fire.

Susan has been consistently drawn to the wax workings of encaustics which led to the collaboration with renowned photographer, Terry Rishel.

Terry Rishel’s professional photography career began in 1980, as an art and commercial photographer, shooting abstracts in nature and progressing to medium and large format cameras, winning numerous international photo awards. During these years Terry also pursued his love in acrylic abstract paintings.

From 1991-2009, Terry became American glass artist Dale Chihuly’s head photographer, as well as studio manager for Chihuly Studio One in Tacoma, working with his crew to install, mockup and light, large installations.

All works photographs are by Terry Rishel

Both Susan and Terry are civic-minded and actively support their community.

You can view Susan and Terry’s work at www.russellrishel.com www.friesensolo.com/susan-russell-hall-terry-rishel

You can view Susans work at www.susanrussellhall.com

You can view their Inside the Studio video at www.youtube.com/watch?v=KYxHlHrUAUs

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by the textures and rhythms of nature. As a contemporary basketry artist for the last 30 plus years, my work is all about exploring those natural elements—bark, vines, and other organic materials—and finding new ways to bring them to life within sculptural forms. When I discovered encaustic wax, it opened up a whole new world of possibilities, blending tradition with a sense of adventure and experimentation.

One of the things I love most about encaustic wax is that it connects the past with the present. Just like basketry, encaustic is both an ancient and contemporary art form—used by civilizations thousands of years ago and still thriving today. The fusion of these two time-honored techniques allows me to bring ancient techniques and forms into a modern context, standing on the shoulders of tradition and interpreting it in a way that is both accessible and engaging for contemporary viewers.

Also featured on the Back Cover

Sculptural Collection

Kudzu, poplar, mimosa and princess tree bark, mountain laurel, and encaustic 18 x 14 x 14 in

My introduction to encaustic wax happened thanks to my friend, encaustic artist Julia Fosson. I had admired her large encaustic paintings for some time and wondered if the medium might have some application in my work. She invited me to her studio, and I started experimenting with wax on my woven baskets, not really knowing what to expect.

At first, I made a bit of a mess—too much wax, too thick—but then something amazing happened. In an attempt to save one of my experimental pieces, I grabbed a pottery scraper to remove the excess wax. That’s when I saw it: layers of color and texture revealed beneath the surface in a way that felt completely fresh and exciting. That little accident turned into one of my favorite techniques, and I’ve been using it ever since to create depth and dimension in my work.

As I continued experimenting in my own studio, I found that encaustic wax could do more than just add visual interest—it could actually help preserve and strengthen my sculptural baskets.

Through trial and error, I arrived at a process I now call encaustic infusion, a method I later learned other artists were also exploring in various ways. This technique involves using a heat gun to melt clear encaustic medium into my finished baskets and sculptural elements. This not only seals the fibers, making them more durable, but also gives the surface a soft, glowing sheen that highlights the beauty of the natural materials. It feels like a perfect marriage of tradition and innovation—honoring the organic qualities of the fibers while using modern techniques to make them last.

Sculptural Collection

Kudzu, poplar bark, contorted filbert, willow, and encaustic, 6 x 24 x 9 in

Sculptural Collection in Driftwood

Kudzu, poplar bark, copper, driftwood, and encaustic, 8 x 10 x 9 in

Bottom left, Sculptural Vessel

Top left, Open Weave Vessel

Kudzu, poplar bark, black walnut dye, and encaustic, 14 x 18 x 18 in

Top right, Bark and Wire Vessel

Kudzu, mimosa bark, poplar bark, copper wire, encaustic, 12 x 10 x 10 in

Kudzu, poplar bark, sugar pine petals, mountain laurel, encaustic, 5 x 10 x 10 in

As I've shared this technique with other artists, I’ve been introduced to creatives who are using it in incredible ways, from traditional reed basketry to unique materials like palm sheaths, seaweed, bull kelp, paper, and a variety of natural fibers. Seeing encaustic infusion applied across such diverse materials has deepened my appreciation for its versatility and reinforced my excitement for ongoing experimentation.

Encaustic wax also plays a big role in the sculptural elements I add to my work. I love using the encaustic scrapings from my baskets to create small bird eggs for the fiber nests I weave into my pieces, turning what would otherwise be discarded into something meaningful.

This strengthens the pieces and gives them a rich, organic texture that visually ties everything together. Sometimes, I use wire armatures for extra support, but often, the wax alone is enough to give them stability.

Working with encaustic wax also awakened me to the power of color and texture in my artwork beyond what I could achieve with natural materials alone. This led me to further experimentation with another beeswax-based medium—cold wax. As a result, I developed a new body of work I call contemporary nature-inspired reliquaries. These are cradled panels designed for wall display, incorporating niches that house woven and sculptural elements, all infused with encaustic wax.

I paint the surfaces of these panels much like an abstract painter, using cold wax medium, pigments, and oil paint to build up rich textures. This unexpected convergence of materials has allowed me to explore beeswax in an entirely new way —both hot and cold.

Cold wax and oil, kudzu, poplar bark, paperclay, and encaustic

24 x 12 x 3 in

As with all creative mediums, encaustic art continues to evolve. Artists are pushing the boundaries with new materials, sculptural applications, and ecoconscious techniques, and I love being part of that conversation.

I hope my work reflects my love for nature, creative experimentation, and sustainability as I use natural materials that might otherwise be discarded. The encaustic process helps extend their life in a way that feels both meaningful and responsible.

Cold wax and oil, kudzu, poplar bark, paperclay, and encaustic 32 x 12 x 3 in

For me, encaustic wax has been more than just a medium—it’s been a doorway to exploring, experimenting, and constantly discovering something new. Whether it’s weaving, sculpting, or layering wax, I’m always looking for ways to push my work forward while staying true to the natural beauty that first inspired me. And that’s what makes this journey so exciting: there’s always something new to explore, another surprise waiting to be uncovered. I can only hope that one day, hundreds of years from now, someone will unearth one of my encaustic-infused baskets or reliquaries and draw inspiration from it—just as I have been inspired by the long history of basketry and encaustic art.

Cold wax and oil, kudzu, poplar bark, paperclay, and encaustic 24 x 12 x 3 in

Matt Tommey is an award-winning sculptural basketry and mixed media artist whose work seamlessly blends traditional weaving techniques with contemporary materials like encaustic wax, pigments, metal, and clay. With over 30 years of experience, Matt first began exploring basketry using invasive kudzu vines as a student at the University of Georgia. His deep connection to nature informs every aspect of his art, beginning with the selection of organic materials during meditative walks in the forest.

Matt’s innovative encaustic techniques, including encaustic infusion, enhance the durability and depth of his sculptural baskets and mixed-media works, bridging ancient craft traditions with modern artistic expression. Matt was recognized as an American Artist Under 40 by the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery in 2011 and his work has been featured in a variety of publications including Encaustic Arts Magazine, Garden & Gun, Our State, NC Living, and Martha Stewart’s American Made Awards. A longtime member of the prestigious Southern Highland Craft Guild, Matt’s creations find homes in luxury mountain and coastal residences, celebrating the beauty of the natural world through movement, texture, and storytelling.

You can view Matt’s work at www.matttommey.com

Anne Feller

As I dove into the world of encaustic, from the very beginning, I wanted to be able to merge my interest in drawing with my interest in wax. There was something so irresistible about the encaustic painting that engaged my senses. I loved the smell, the warmth, and the texture; it was love at first melt. Despite my immediate infatuation with encaustic, I knew early on that I could never fully depart from dry mediums—pencil, pen, and pastel—that I had built my portfolio around for years. I wanted to create pieces where the two methods, encaustic and drawing, were deeply intertwined and could both shine equally. With this in mind, I began my journey into encaustic.

The initial challenge was with the paper. As the binding factor between the two mediums, the paper needed to be both strong and textured enough to hold the dry medium while also being thin and smooth enough to embed into the wax in an even and almost transparent fashion. The search was on and in due time I discovered hanji, a traditional Korean paper made from mulberry tree bark. The paper was traditionally used for many purposes, such as lining doors and windows, as the paper had the ability to be durable enough to obstruct outside elements but thin enough to allow natural sunlight in. I found hanji was the best paper to absorb my mediums without altering any fundamental characteristics.

Where From Here? Encaustic, pastel, graphite, and paper, 36 x 24 in

Where From Here? Process drawings on hanji

After paper, the next challenge presented itself in the form of layering. I always wanted the ability to embed multiple drawings into one piece, layering in a way that was reflective of a timeline, but with more layers came more challenges. Each piece is built up by interchanging layers of thin wax and drawings. Only through patience could the layering process turn out even, and only with careful composition could the timeline be perceivable.

Birth Month

Flowers #1

Process images of drawings before wax

Next Page

Birth Month

Flowers #2

Process images of embedding drawings into wax

In order to embed a series of drawings, I first put down a layer of wax. The initial layer needed to be thicker to give the piece a solid base. Once the wax had solidified, I lined up my first layer, a singular piece of paper with a drawing.

Carefully I reheat the wax through the paper until the wax becomes porous enough to absorb the drawing. Importantly, the heating device should not linger on one spot too long as the paper is at risk of burning and the wax underneath can become liquid resulting in uneven surfaces.

When adding multiple layers, reheating from one side of the piece to the other to embed the drawings is the best method I have found for even layering. Going inch by inch, line by line, the paper has the best chance of entering the wax without crumpling and creating a distracting wrinkled efect.

Birth Month Flowers

Encaustic, pastel, graphite, and paper, 10 x 8 in

Our Uncertain Future, Thumbnail 8 x 10 in practice piece before sizing up

As I build up layers, there comes a point when bottom layers are lost into the wax. Creating a timeline is important in my work, so finding a balance between too many layers and not enough is crucial. I have found three or four layers of drawings to be the sweet spot for being able to tell a story without losing too much into the wax.

The only way to foresee how a piece is going to look is by creating a mini “thumbnail” version, usually less than 10 inches on any side. During this process, I have the ability to make mistakes, and play around with compositions and colors. Even the order in which the layers are embedded can have a profound impact on the final imagery. While time consuming to make, these little thumbnails are a great tool to help guide my decisions for a larger piece.

Our Uncertain Future Encaustic, pastel, graphite, and paper 30 x 40 in

With drawing as a core and wax as the filter, color then became the enhancer for me. I use color in two forms, pastel and pigmented encaustic. With these two forms, I have developed three styles of incorporating color within my pieces to guide or enhance the imagery. The diference between the three styles is both how I use the color and what focal points demand attention in return.

The first style is minimalistic in that I choose only a base color or color scheme that lives underneath all the layers of drawings. The base color(s) are intuitively chosen based on the mood of the memory, then I intersperse layers of non-pigmented wax and drawings overtop. Pieces with a strong sense of movement are best suited for this style. The wax acts as a binder, and the drawings take a central focus. With the drawings doing all the visual storytelling, there's a lot of trust I must put into the process of layering.

I could spend hours working on a series of drawings, but the final piece is really only revealed within the final steps of embedding the drawings into the wax. The piece could take form within a 30 minute window of layering, and I must allow whatever happens to happen, no alterations are made at this point.

As a result of a more minimalistic approach to color, this style creates a focal point around memory as a lived experience, something captured through drawn movement.

The second style incorporates color within the layers. This is executed with both colored pencils on the paper layers and pastels within the wax layers. Pausing after each layer to add color allows me more time to sit with the piece and to guide it in a more specific direction using color to pop or subdue certain areas. In contrast to the first style, the movement from the layered drawings is no longer the focal point, rather the overall mood of the memory or the experience of remembering takes hold. These pieces tend to be more disjointed and vague, as the colors abstract the drawings further with each layer being built. The push and pull between the drawings, the wax, and the colors create a dreamscape of memory.

The third style I have most recently been finding much enjoyment in takes on a more traditional painterly approach. The same practices of the previous style still apply— building up layers of wax, drawings, and colors; however, what sets this style apart is the focus on the final layer of encaustic.

After the initial drawings are embedded and the colors have been outlined, I go in with a smaller brush and add points of color using techniques inspired by pointillism. The collections of brushstrokes become the core of the final image rather than the drawings underneath. The colors and textures created through the brushstrokes guide the viewer's eyes through a created timeline, thus placing the focal point on the broader storytelling aspect of a piece.

Till I See You Again (Navigating the Space In-Between) Encaustic, pastel, graphite, and paper 36 x 36 in

Regardless of the number of layers I put into a piece or how I try to plan the final imagery through composition and materials, inevitably many details of my drawings will be buried within the wax. This sense of loss is something I have become familiar with in my practice. If each drawing is born out of desire to capture a memory with utmost certainty of the details of the space and the subject, then the wax becomes the factor that breaks it all down into something more abstract, fluid, and unfamiliar. In a way the wax is an entity; I give memories to the wax, and in return, the wax chooses how to filter, divide, and distort the memory into something entirely unpredictable. The wax allows me the space to accept the passage of time and the fogginess of memory. Every piece I create thus becomes an exercise of letting go. This cathartic act propels me as I continue in my practice of combining drawing and encaustic.

Throw And Encaustic, pastel, graphite, and paper, 12 x 18 in

Anne Feller is a figurative encaustic artist who works with themes of memory. She is based out of Boulder, Colorado. She is a 2021 recipient of the Emerging Artist Grant from International Encaustic Artists. Feller opened her first solo exhibition The Tip of the Tongue at Artworks Center for Contemporary Art in July, 2022. She published her essay Fossilization of Memories in the Fall 2022 edition of Wax Fusion. Feller’s second solo exhibition, LIMINAL, opened at the Tointon Gallery in May, 2024. She is currently preparing for her third solo exhibition, No Longer, Not Yet, to be shown at the Littleton Museum in Fall of 2025.

You can view Anne’s work at www.annefellerart.com www.instagram.com/anne.feller

Jane Cornish Smith

One of the most alluring characteristics of encaustic and cold wax medium are their incredible versatility. Yielding endless artistic possibilities through reductive and additive techniques, wax can be uniquely formed by tools, gravity, heat, excavation, brush, and more. It can be a medium, adhesive, or luminous sealant, providing both practicality and mysterious depth. Wax can showcase dimensional formal shapes and forms and make a statement. To me, one of its more compelling qualities is its ability to convey meaning when combined with nontraditional materials, melding throughout mixed media to expand its impact. Trash—in all its outsider-ness—is itself a versatile medium, and like wax, most often an enduring material. Together, they can tell a story through ancient beauty and contemporary ugliness.

In Dallas, Texas, where I live, the beautiful White Rock Lake has long served as a cherished gathering place for recreation and reflection. Unfortunately, its natural beauty is under constant threat from litter, making monthly organized cleanup eforts essential to protect the health of the lake and the wildlife that call it home. In an upcoming solo exhibition at the Bath House and Cultural Center, just steps from the lake’s beloved waters, I incorporate wax with trash—mostly collected from those storied shores—with the intention of bringing awareness to a growing environmental concern. It is titled Intertwined Detritus.

Detritus—rubbish left or deposited, provides an inconsiderate, harmful, abundant inventory of texture and color when mined for art making. In the exhibition, strata of stuf create tragic yet visually interesting layers.

For the Love of the Lake Styrofoam, plastic straws, partial bottle cap, encaustic, cold wax/oil, and mica powder 5 x 7 x 4 in Also featured on the Content page

Encaustic and cold wax intermix throughout non-compostable refuse, in a sense embalming in tandem. Like the intertwined art created for the Bath House walls, trash intertwines in our ecosystems, ensnaring the living beauty around it.

One of the pieces for the upcoming exhibition, For the Love of the Lake, is comprised of a heart-shaped piece of Styrofoam, cold wax medium/oil, straws, and partial bottle cap, finished with red and pink encaustic paint. Drips of wax ooze around the single-use plastic, a dusting of mica powder highlights the texture. Oddly heartfelt, the sculpture is a respectful nod to the volunteers that collect shoreline litter, come rain or shine.

Two Nests Connected is constructed with waxy crocheted paper strips beneath birds’ nests, supporting a startling non-egg array of discarded objects including a fishing bob, light bulb, child’s toy, and beer caps. Encaustic paint imparts color and enables the paper nests to take on and maintain the organic shape of the real thing. The two nests co-mingle, as if hanging onto each other for dear life.

Two Nests Connected

Encaustic, paper, bird’s nest, beer caps, plastic egg fragment, ring, toy, light bulb, and fishing bob 5 x 9 x 14 in

Ephemera and Permanence: A Weaving is a large wall hanging of stretches of interlocked mulberry paper and plastic bottles; a mixture of the more ephemeral and the permanent. Encaustic provides the paper with rich skin tones and leather-like heft. The most prevalent item pulled from the lake—plastic bottles— cue viewers to its dangers, as wildlife and humans navigate through microplastic-infused water.

Ephemera and Permanence: A Weaving Mulberry paper, encaustic, and plastic bottles

64 x 70 x 5 in

Caps and Scarf (detail)

Yarn, encaustic, fishing line, and bottle caps

33 x 7 x 4 in

Bottle caps, fishing line, encaustic, and soft yarn make up the artwork Caps and Scarf ofering difering textures in the form of a scarf. Caps are separated by malleable metallic wax, formed by the heat of my hands, emulating split shot fishing weights. It is my goal that viewers will almost feel the scratchy caps around their necks, made even more apparent by the stark contrast of yarn, like the incongruous existence of litter in a lovely lake.

Wreckage 3

Gauze, plaster, wood, glass, gravel, twine, dirt, silt, encaustic, and cold wax on panel 14 x 15 x 2 in

Wreckage 3 is a beat-up wreck of wood shards, shattered glass, cord, paper, dirt, silt, paint, encaustic, and cold wax medium. Versatile wax is formed in relief to emulate dirt and gritty texture, and to help adhere the actual soil itself.

Lady of the Lake with Shoes depicts the enchantress that infuses wisdom and courage, despite the polluted waters from which she came. Her white drapery is stained with cold wax, oil, and mineral spirits, along with sediment, as it pools on the floor, dredging up discarded shoes along the way. At 10 feet tall, wrapped in yards of woven gauze, she is hard to ignore.

Lady of the Lake with Shoes

Gauze, cold wax medium/oil, sediment, and shoes

10 x 2.75 x 1.5 ft

No Time to Play Ball has a broken paddle as substrate, replete with recreational balls. Cold wax medium and oil are painted onto a flat surface in a classic, representational manner to mirror the actual balls adhered to the paddle. Some of the versatility of cold wax medium includes its ability to provide body to oil paint, and to allow it to dry more quickly with a matte finish. The piece speaks to the idea of play turned into work—for someone else.

No Time to Play Ball

Paddles, cold wax medium/oil, balls 20 x 8 x 3 in

Mermaid’s World is a compilation of wax, silt, crocheted cord, paper, Styrofoam, plastic labels, and more. The etched wax is repeated in scraps of intaglio print, emphasizing the versatility of beeswax, and the scratchy nature of the work. A collage of jumbled strata echoes the chaos of outdoor littered spaces that obstruct water flow, causing shoreline erosion, and an overabundance of choking silt.

Mermaid’s World

Encaustic, crocheted cord, silt, Styrofoam cups, and plastic labels

36 x 30 x 2 in

Mermaid’s World, detail

Catch and Release was created with waxed gauze in net-like forms, filled with found objects and fishing-related cast-ofs. The wax emphasizes the delicate weave of the gauze and enables the nets to be molded and protrude efectively from the gallery walls, receptacles of flotsam and jetsam.

and Release

Gauze, encaustic, fishing bobs, hook, line, assorted trash

32 x 34 x 3 in

Ironically, it is the trash-strewn shores that provide recycled items for the making of Intertwined Detritus. But it is wax that binds the materials into art with a message—that brings litter inside for gallery visitors to see and understand. The integration of traditional and nontraditional media, an artist’s hand, and a cautionary vision underscore the fragility of our environment, emphasizing the need for broader sustainability and stewardship for our future.

Catch and Release, Detail

Originally from Canada, Dallas area-based artist Jane Cornish Smith’s nomadic childhood, along with her artist mother, fostered an appreciation for creativity from a young age. Jane produces paintings and sculpture with a diversity of materials and subject matter, with a focus on cold wax medium and encaustic. Usually figurative or environmental in nature, her work often reveals human vulnerabilities, with the goal of providing viewers with selfreflective opportunities.

She has attended artist residencies at the International School of Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture in Umbria, Italy; Vermont Studio Center; and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts; and earned BFA and MLA degrees from Southern Methodist University with a MFA from East Texas A&M University. An award-winning artist, her work hangs in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, Africa, as part of the Art in Embassies Program; University of Texas at Tyler; East Texas A&M University; Brookhaven College; the Museum of Encaustic Art, Cerillos, New Mexico; the Tenby Museum and Art Gallery in Wales, U.K.; the Cancer Support Community of North Texas; and others. She enjoys teaching and making art from her studio in rural Lone Oak, Texas.

You can view Jane’s work at

www.janecornishsmithart.com www.instagram.com/jcsart5555/

At this moment, when the world as we’ve known it in our lifetime appears to be unravelling, I find myself seeking ways to respond in my daily life, my artistic practice, and the many areas where the two intersect.

For more than a decade, my encaustic and oil paintings have returned again and again to the theme of finding light in the darkness—expressing the hope and optimism I find through my connection to the natural world, even in its darkest moments.

My works often explore liminal spaces between day and night, recollection and observation, realism and abstraction. Viewers who connect with my paintings mention that the works resonate with them emotionally, evoking experiences, memories, and connections to a sense of place.

During recent times of political turmoil, I find my work shifting in myriad ways—shifts in approach, materials, and subject matter…Shifts in the intensity of my palette, mark-making, and emotional content.

Approaching Storm, detail

Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor

A Morning Rife With Possibility Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor 16 x 20 in

Some of my paintings have become darker with higher contrast, more saturated hues, and a more intense and vigorous use of tools for scraping and scratching the surface as I build layers and then destroy areas, cathartically releasing some of the grief and rage I am experiencing as I read and respond to the news. I often leave these works less resolved than I might previously have done, resulting in an unsettling or even ominous mood. Yet, as I step back from these works that lack resolution, it seems they aford more opportunities for contemplation about the upheaval we are experiencing. Even the titles I choose, such as The Coyotes Howled Until Dawn, feel more reflective of my sense of the dangers of this moment.

The Coyotes Howled Until Dawn Encaustic, India ink, with oils and beeswax over watercolor on Encausticbord 40 x 30 in

Other new works also reflect turbulence, yet are marked with a sense of having passed through a storm. The upheaval is clearly evident, yet there is an element of harmony that infuses these works.

The Winds Across Clew Bay Encaustic, India ink, with oils and beeswax over watercolor 18 x 24 in

I find myself alternating between these two states of experiencing dread and finding moments of something akin to peace in my internal responses to the chaotic state of our world. Those dichotomous responses are finding their ways into my work, although not with conscious intent on my part as I start new works.

Through and beyond all the upheaval, I also hold onto my awareness of the transient nature of our very existence as I explore themes of ephemerality and fleeting moments gone by in a flash. This aspect of my work is, no doubt, not only a response to this precarious point in our history, but also a reflection of a heightened awareness of temporality as I age.

Many of the works I am creating, that spring from this sense of the transience of all things, incorporate experimental approaches and new content. A hummingbird hovers and merges with suggested vegetation and blossoms in And Then, In An Instant, He Was Gone.

And Then, In An Instant, He Was Gone

Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor on Encausticbord

8 x 8 in

In The Moment Flickered and Vanished, I experimented with a new photo transfer technique and used repeated images of my adult daughter as a young child, which I collaged with encaustic paints and medium, emulating a flickering movie from a bygone era of cinema when the film itself often melted.

The Moment Flickered and Vanished Encaustic and photo transfer, 3 x 10 in

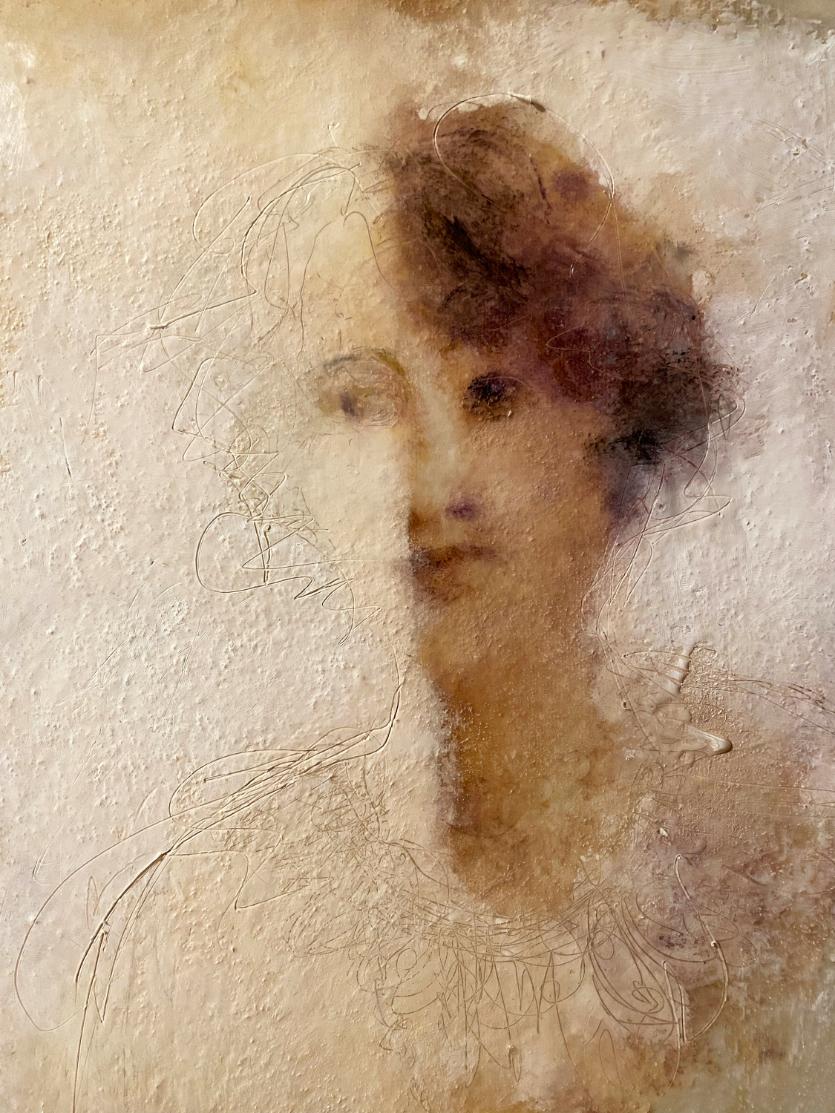

In Almost Recalling, I infused watercolor paper with encaustic medium and then painted the surface with a limited palette of oils and wax, hinting at the ways in which memories of a loved one’s face can be so difcult to fully recollect, even as traces of the features of each generation of family members are echoed in one another’s countenances and gestures, again and again.

Almost Recalling

Encaustic with oils and wax over watercolor paper 14 x 11 in

Connected to that theme of impermanence, I find myself rediscovering appreciation of beauty in the most mundane, unexpected places. Here where I live in the Northern Catskill Mountains of New York, the late winter landscape is quite dull and gray as the snow is nearly all melted and the earth is mucky and muddy. One might be hard-pressed to describe the landscape as beautiful; yet, there is a soft loveliness to the quality of light and a gentle feel to the air foretelling the coming spring in a world suspended, seemingly interminably, between decay and rebirth.

Late Winter Light

Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor 18 x 18 in

I’m drawn to the organic beauty of decaying matter as it sets the stage for the emergence of new life, as in fallen leaves and blossoms as they break down and enrich the earth. I’ve begun a new body of works that celebrate the poignance of natural detritus through heavily accreted encaustic paintings coated with oils, encaustic paintings on paper that incorporate India inks and translucent R&F Pigment Sticks, and gelatin monoprints which I coat with encaustics and oils.

These seemingly disparate directions to my current work feel connected in ways I sense but am not yet able to articulate; however, they seem to converge in my recent painting, Through A Train Window, selected for an award by Michelle Robinson, juror for the recent When in Rome: The Art of Travel exhibition (which is the reason I was invited to write this article).

In this work, I overlay an expression of my internal state of mind with a seemingly unrelated sense of gazing out the window of a rapidly moving train at dusk along the Hudson River while my focus was turned inward, processing the shock of the 2024 US presidential election results.

This abstracted juxtaposition of internal and external impressions feels like a natural synthesis of all that has come before in my encaustic painting, while simultaneously opening a portal to a new world of artistic expression—one I had hardly known existed.

Poised, with no map in hand and no known destination, the journey begins.

Oak Leaf

Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor 12 x 9 in

Through A Train Window

Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor 18 x 24 in

A Fallen Blossom Encaustic with oils and beeswax over watercolor 10 x 9 in

Regina B. Quinn serves as President of International Encaustic Artists and as ViceChair of the Woodstock Art Association & Museum. She lives in New York’s Catskill Mountains and teaches encaustics in person at the Woodstock School of Art and at Mulranny Arts in Ireland. Regina is represented by Carrie Haddad Gallery in Hudson, NY, and her encaustic artwork is held in several private and permanent collections, including the Williamsburg Art and Historical Center in Brooklyn, NY, and the Museum of Encaustic Art in Santa Fe, NM. She has received numerous awards including the Faber Birren National Color Award, the Cooperstown Art Association’s Grand Prize, IEA’s Inspiration Award, and the WAAM Yasuo Kuniyoshi Award.

You can view Regina’s work at www.reginabquinn.net www.instagram.com/ginabq/ www.facebook.com/reginabernadette.quinn.5/ bsky.app/profile/reginabquinn.bsky.social carriehaddadgallery.com/artist/regina-quinn#inventory

You can view Regina’s upcoming workshops at woodstockschoolofart.org/instructor/regina-quinn/

This issue marks a compelling moment in encaustic’s own journey, where tradition meets transformation and innovation points to an exciting and ever-evolving future for the medium.

IEA’s recent exhibition When in Rome: The Art of Travel highlighted current trends in encaustic art through diverse interpretations of travel—both literal and metaphorical. Travelling outside of convention, artists reveal how the medium continues to evolve through bold experimentation and boundary-pushing themes.