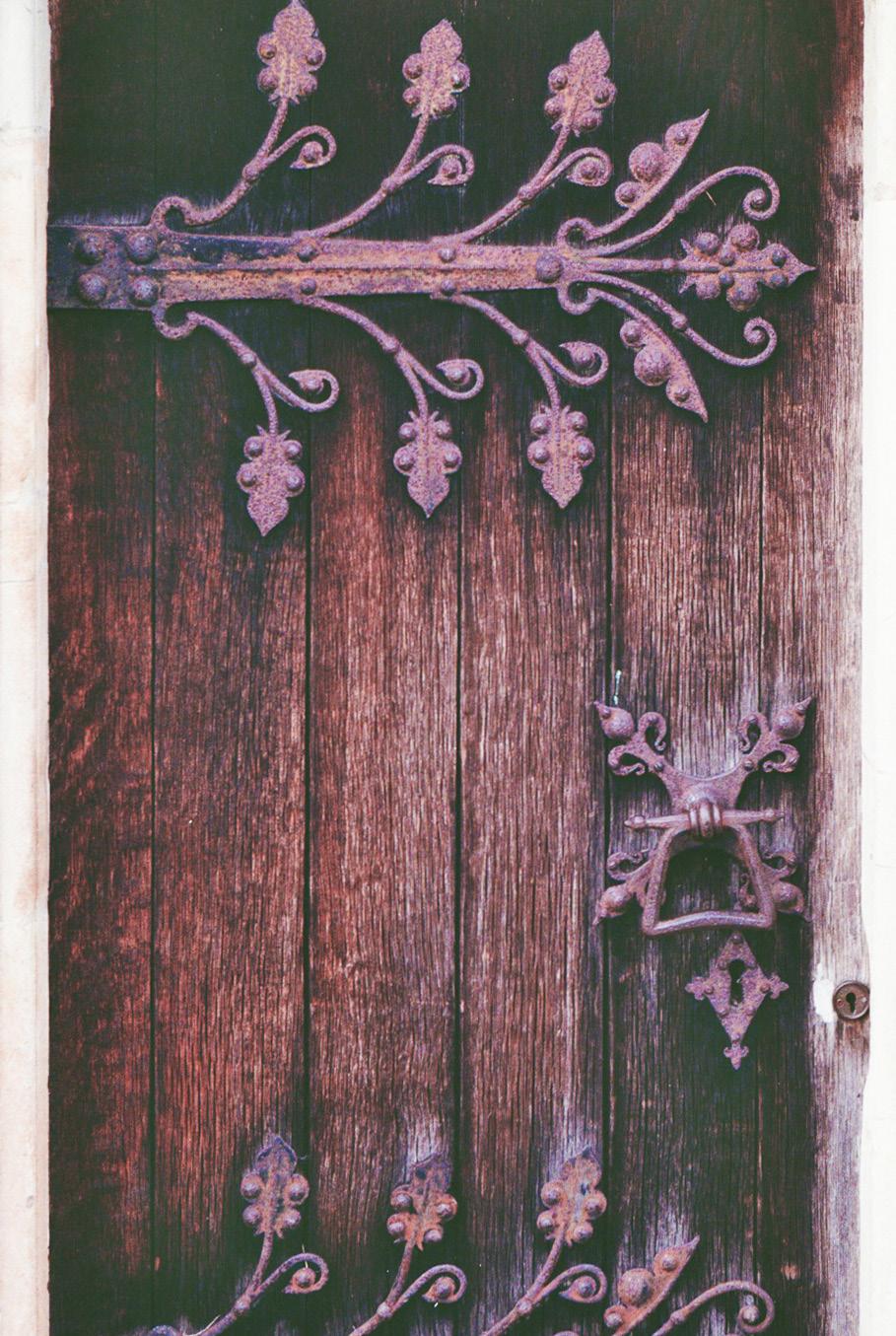

The material world around us is imbued with beauty and meaning. Yet today we are disconnected from our surroundings. Technological advancements have caused the life around us to speed up, making it increasingly hard to slow down and just be in the moment, with the materials that surround us. Complex manufacturing processes, mean we no longer know how the human-made materials around us were made. We have lost the ability to read meaning and personal connection into the tactile objects that we inhabit the world with. The term ‘material-culture’ has become tainted with an association to over-consumption. Here at Land Made, we believe that we should celebrate the tangible world around us and use it as a driver to become more grounded and connected to the physical objects that we feel personal connections to.

We believe that nature and craft go hand-inhand. The materials we construct our world from are in some-way or another taken from nature, and what we make and how we make it directly impacts the planet we live on. We are surrounded by organic matter, which continuously provides engaging, multi-sensory experiences that ground us in the moment. We have a responsibility to the earth to build our tangible world in a way that respects it and celebrates its beauty.

Land Made is a creative agency that explores and celebrates the intersection of craftsmanship and nature. We are dedicated to telling the stories

behind craft and honouring the hands and minds behind the making. We believe craftsmanship can be a powerful tool in connecting humankind to the natural world and driving positive change during a time of environmental crisis. Our mission is to re-enchant you with the charm of the natural world and considered craft.

Our first ever issue of Land Made is titled The Symbiotic Issue. ‘Symbiosis’ is a biological term that describes the relationship between two plants or animals where each provide the other with the necessary conditions to live. To us, this perfectly describes the relationship between craft and nature. Craft can’t exist without nature as it is the source of so much inspiration and materials. While nature can benefit from slow-craft movements, encouraging considered consumption and innovative environmental solutions. The two feed of each other, entangled in a deep history of transformation as humans work with nature to shape the world around them.

In this issue we follow the creative and handson process of four different artisans, whose practice strives to celebrate the natural world around us striving to find low-impact ways of making that do not take from the earth.

Whether you yourself are a maker, or someone who finds themselves at home with nature, we hope you find this a grounding space that will bring you a greater sense of connection to the world around you.

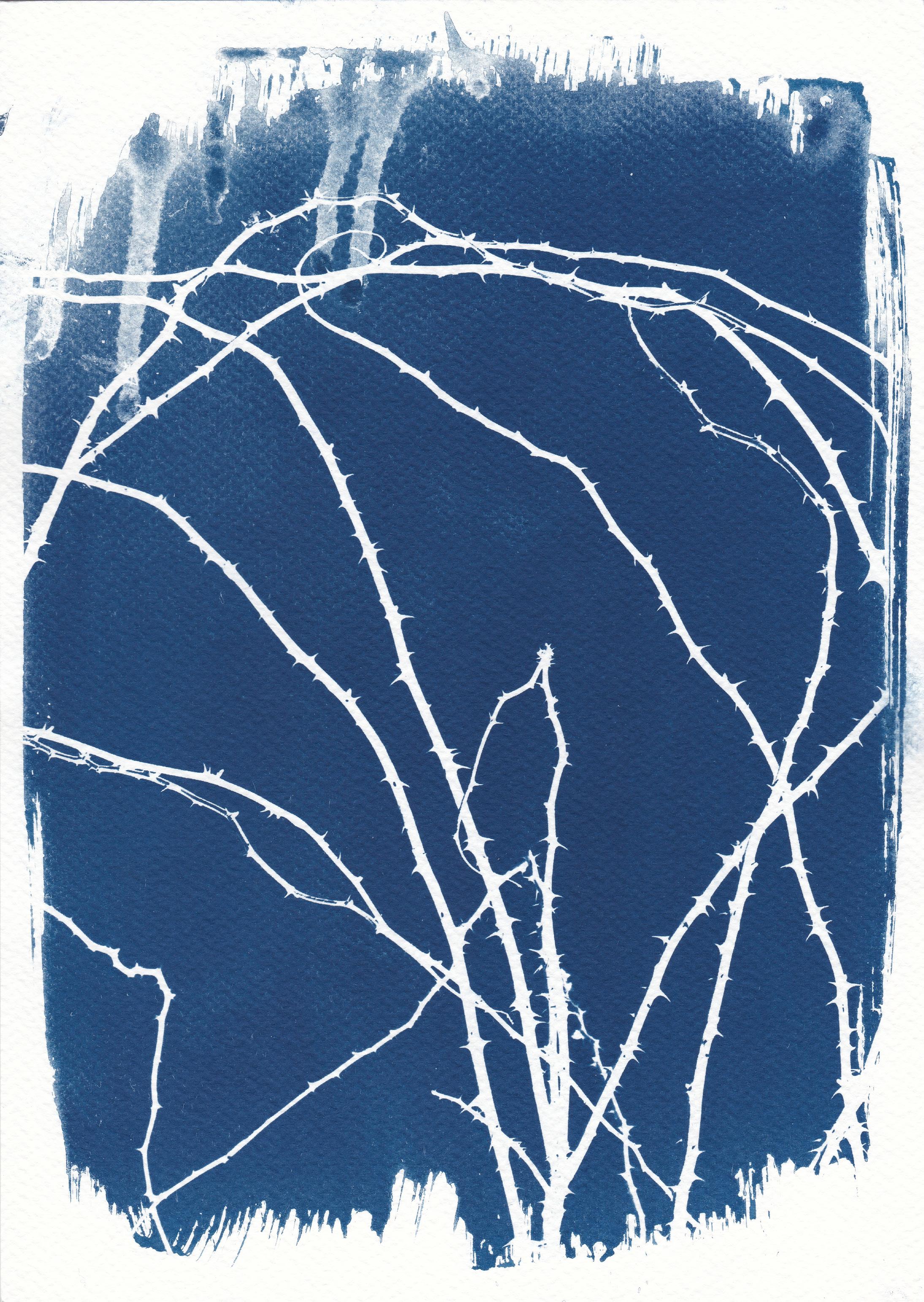

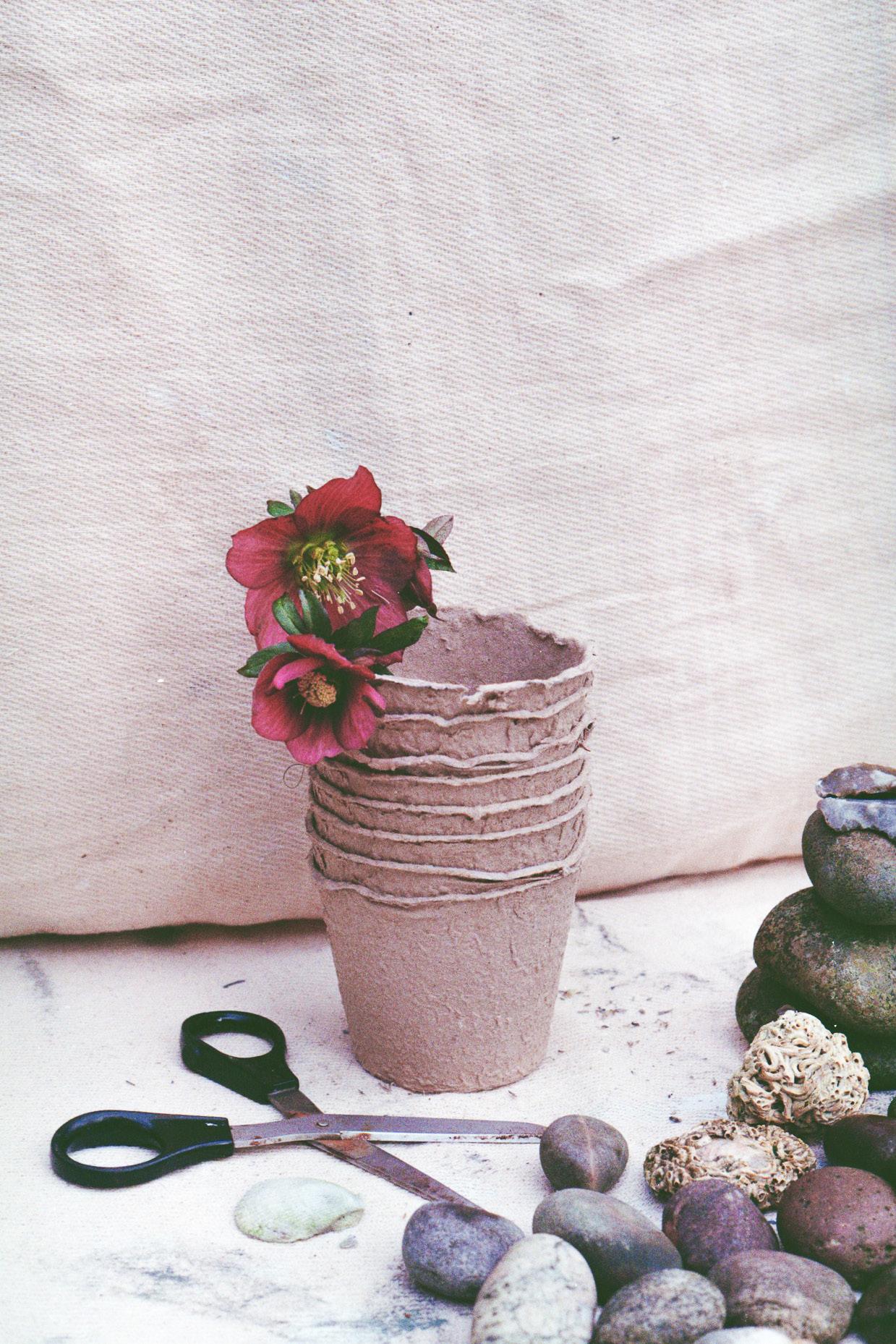

Illustrator and Printmaker, Emma Bond, has an eye for detail allowing her to collagraph prints that celebrate the magical mundanity of spending time outside.

Surrounded by a mix of real-life and twodimensional floral forms, Emma Bond, sits in her Walthamstow-based studio, that she shares with four other artists, while the sun beams through the windows on a fresh February morning. She invites us into her botanical world as she demonstrates her process of making a whimsical collagraph print, from start to finish.

This is a funny time of year for Emma. Christmas is very busy filled with lots of markets, so she spends the beginning of the year doing lots of planning. Recently she’s been preparing for some upcoming workshops she is running. Emma has always enjoyed teaching and even worked as an art technician in a secondary school. “There’s something really nice about showing people how to make something. Especially if they don’t think they’re creative.” She teaches her Tetra Pak technique in schools and finds that each child’s interest will lie in different areas. “Some kids will really love the designing part of it, and some kids will really enjoy the rolling of the ink and the colour mixing. There are lots of different ways they can enjoy themselves.”

She’s now starting to shift her focus to making some new big prints as well as some mini prints for Mother’s and Valentines Day, while also working on entries to printmaking prizes and open call exhibitions.

Emma started her journey into printmaking by studying ceramics at Falmouth University. It was here that she realised just how much she enjoyed the decorating process. She then went on to undertake some work in textile print design. “I feel like most people I know started off in one thing and then ended up in something completely different. I think it’s nice if you can use the parameters of your course to push it in the direction you want.”

Emma is a self-taught printmaker, who found time to learn the craft during maternity leave. She spent a year trying out lots of different printmaking techniques, like mono printing, and using YouTube she found there was no shortage of accessible knowledge out there. It was a process of trial and error, until Emma finally found what worked for her. “When I finally found Tetra Pak printing, was when I was like I’ve finally found my thing!”

Sitting behind her, mounted on the wall as she works, are mixing cards and cotton buds stained with ink from last year’s creations, that Emma has saved and framed. “I don’t know why I kept them, but I felt like I couldn’t get rid of them, it’s sort of like evidence of what happened.”

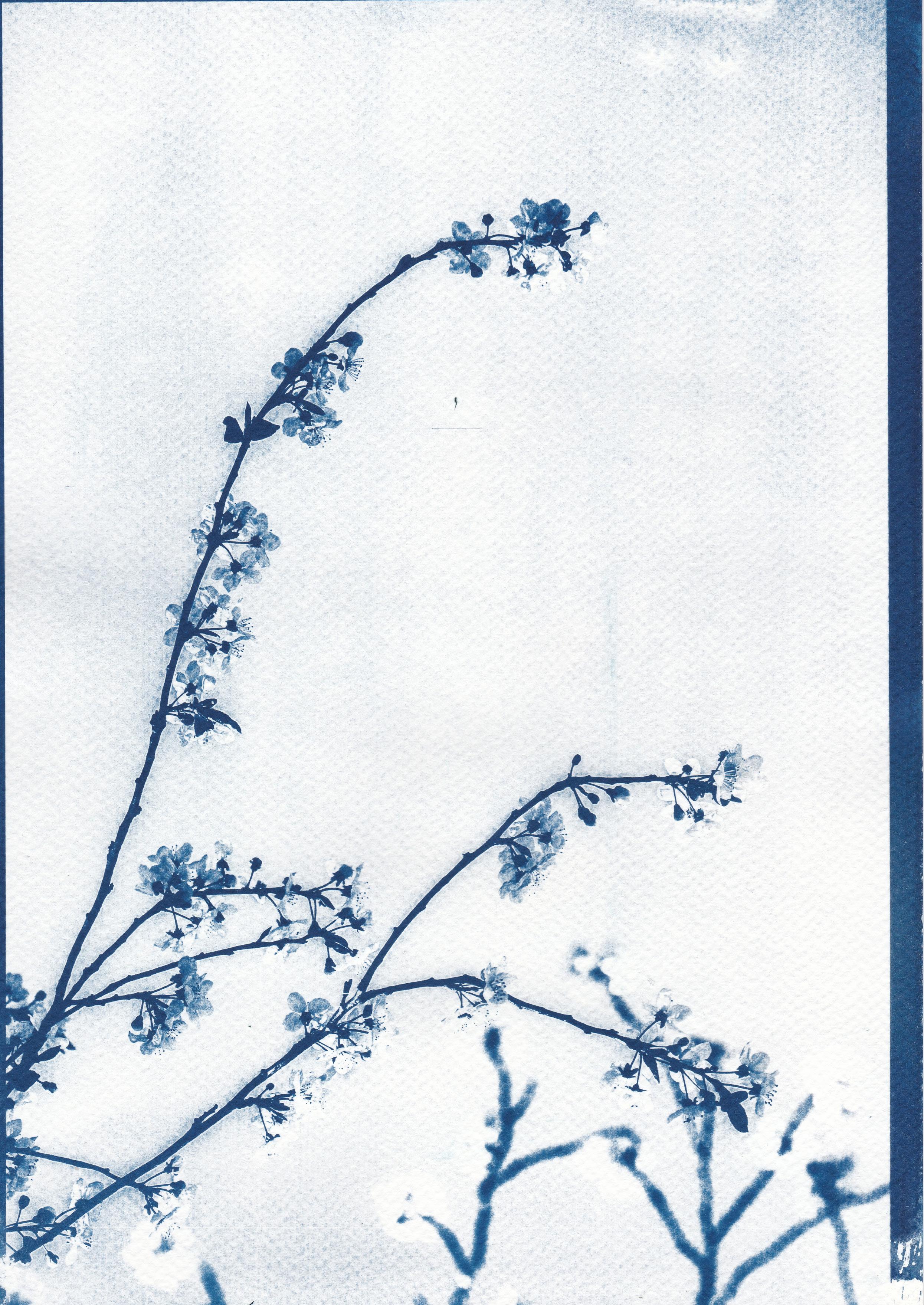

A lot of Emma’s work consists of large prints, with lots of complicated layers, resembling a whimsical and blossoming garden, which can prove a mental challenge. Recently however, Emma has been working on building a series of single stem prints of lots of different flowers, especially ones found in the local area. The rosy flower she’s making today is a musk mallow!

The process begins by finding inspiration. Emma prefers to draw inspiration directly from nature. Last week she was drawing from life while, evidenced by the couple of vases, filled with slightly wilted flowers, sitting on her desk. She often works with her local florist, who use local growers, and will send over flowers to inspire prints. While her phone is filled with hundreds of floral photos, inspiring colour combinations and compositions, working from life is integral to her practice. “I think it’s really important to actually look at what you’re drawing. When you do that from a photo you don’t necessarily get the full picture of how it comes together. A lot of my stuff is very realistic so I kind of need to see it. The way I construct my plates is kind of like deconstructing a flower, so I need to see them in real life to see what goes where.” She very rarely works from her imagination, which helps to keep that sense of realism within her work.

“I don’t really work in sketchbooks. I prefer to work in flat pieces of paper.”

“Theres something quite freeing about it. A sketch could disappear, and no one would know. There’s no commitment there.”

Emma will then draw out a quick sketch to find a composition before drawing out a much more detailed version of the image. When doing her more complicated pieces, with lots of layers she needs a good record of where things go, so that drawing becomes her master version. She then traces out a simple line drawing which becomes a template to create the shapes of her plates. To create her plates, she uses Tetra Pak cartons supplied by the local café. As well as being accessible, Tetra Pak is a very versatile material and can be easily cut, making it less intimidating to work with. She starts by tracing out the basic shapes onto the Tetra Pak, before cutting them out. She will then go in and etch out the details.

Next, Emma will mix the inks on clear pieces of lino. She starts by applying a base layer to the plates and then removing or adding to them to make sections lighter or darker. This method allows all the tones to mix together and complement one another. Emma finds that after hours of practice and experience, she can now predict what will happen when she makes certain decisions during the inking process. At this point she will stop looking so much at the reference and more at the plates themselves. She uses oil-based inks as they help to achieve crisp detail and stay wet for around three days, which is crucial when working on more complicated prints. A largescale print with lots of layers will take Emma about sixteen hours just to ink from start to finish. She’ll mix all the inks the day before, as that in itself can take a few hours. She’ll start work at six in the morning methodically

inking the plates and composing them on the printing press as she goes, starting with the back layers first. It’s usually around eleven in the evening by the time she’s finished the inking process. She keeps the colours used true to those of the actual flowers. She uses lots of different tools to apply the ink, including a roller or cotton buds prove useful for adding colour and detail evenly in smaller areas. There are lots of different techniques used to apply the inks, allowing for lots of creative decisions to be made. Emma will often spend time working the ink into the etched grooves and wiping it back, to make the details coloured rather than white. She uses an old sock to blend the ink out to the edges, creating a nice translucent gradient, that gets lighter out towards the edges.

Once a plate is inked, she’ll compose it on the printing press. Emma keeps most of the pieces loose because there many layers, so a bit of movement helps them to not crease. With the bigger piece she might use a bit of double-sided tape to fix down a few key elements. Once all the plates are laid out on the printing press, in the final composition, she fills a tray with water to soak the paper in. It’s usually around 1pm when Emma will start printing one of her bigger pieces.

Emma will remove the paper from the tray, blot it off with a towel and carefully place it over the plates of the press. She’ll then place some newsprint over the paper to absorb the water and increase the pressure and finally cover that with some felt, before rolling it through the press.

By soaking the paper, it becomes much more flexible, and when put through the press the many layers of plates emboss the paper adding lots of depth and texture creating a tactile quality. You get the idea that a stalk is behind a petal, for example, adding lots of extra dimensions.

After the original print, Emma will make a ghost print too. This is where you put the paper through for a second time on the same plates to get a ghostly version of the original. “Sometimes they are in their own right quite beautiful, so I think it’s always worth trying it and seeing what you get. Sometimes I actually prefer them.”

With these smaller, single stem prints, Emma will often run a small edition. So, she’ll clean the ink off the plates and do another. She can often repeat this process about five times before they start to fall apart. While the prints are made using the same plates, each one is still unique as the ink will be re-applied and the composition changed slightly. “It’s a nice way to give people original prints at a lower price point, while still getting something unique. Something that is important to me is trying to make things affordable and accessible. I think it’s important to make this kind of art, because I feel like everyone should be able to have nice things or things they enjoy. So I try to do things at different price points.”

Despite the long-hours, Emma finds once she’s in the grove of it, it’s a lot of fun. “Often, I’ll listen to an audio book while I’m doing it. I’ll find one that’s about 16 hours long and listen to the whole of it and I think that really helps to concentrate my time and energy.” She also leaves herself reminders throughout, to keep the process running smoothly.

Living and working in Walthamstow, Emma has found lots of local inspiration, in terms of colour and pattern, especially with William Morris’s connection to the area. Being a very detail-oriented person, colour, line and texture are always at the front of Emma’s mind when working, which comes from finding time to stop and really observe. This approach has proved successful in developing intricate patterns that capture the magic of the natural world.

Sustainability has become an increasingly important factor in Emma’s work. The plates are made from materials that would otherwise go to waste and the inks are non-toxic and can be cleaned up with soap and water instead of chemicals. All the paper used are FSC certified, so they’re sourced responsibly too! There’s a clear relationship between subject and medium in Emma’s work. She doesn’t take from the natural world she illustrates. “There’s something really nice about creating something like this from waste. It helps people to connect with the work.”

Emma’s work is a celebration of hand-printed techniques, and she enjoys the space it provides away from the digital world. “I think for me, the process of making by hand is something I really need as a person. I’ve always found it quite calming. In a world where AI is probably going to take over at some point, we probably come back to these kinds of traditional crafts at some point. When I say traditional, this isn’t very traditional I suppose, in that it’s a fairly new technique, but it builds on lots of old traditional skills. It’s sort of a reinvented version. I think people are starting to push back a little bit and slow down.” She also finds joy within the serendipitous quality of printmaking. “It’s so magical with printmaking or any kind of technique where you can only kind of control so much, and the rest is like a surprise! It takes the pressure off in lots of ways.”

With so many different stages involved in the process, Emma enjoys the variety that it offers. “I have the ability to focus for really long periods of time, but I also get bored quite easily. depending on what it is. This style of work does tick a lot of boxes for me. I love drawing so there’s the drawing stage, then there’s the cutting and then there’s the etching, and so on. There’s enough going on that once I get bored of one thing, I get to move onto another. So it kind of piques my interest.”

Finding time to play and experiment is an important aspect of Emma’s practice. “It feels like there’s always a bit of a pressure to make sure you’re moving forward. But experimentation is a really important part of it and it can feel quite self-indulgent, to be like today I’m just going to mess around and see what happens. But it is really important and if you don’t do it your work can suffer a bit because it gets a bit stagnant.”

Emma doesn’t spend all her days like this. As a small business owner, she can often be found working on her website, social media presence and mailing lists. “I think now it’s so much more than just doing your work, you have to be seen to be doing your work.” She has found these online spaces have been really great in supporting prize or open call exhibition applications. On the other hand, she has found the bulk of her work through the relationships she’s built outside of these online spaces and highlights just how far the act of kindness and honesty can get you in the creative industry. While it can be scary to enter a new industry where you don’t yet know anyone, Emma found support within free business monitoring programmes run by her local council. After making the prints, Emma will often frame them, becoming unique artworks in their own right.

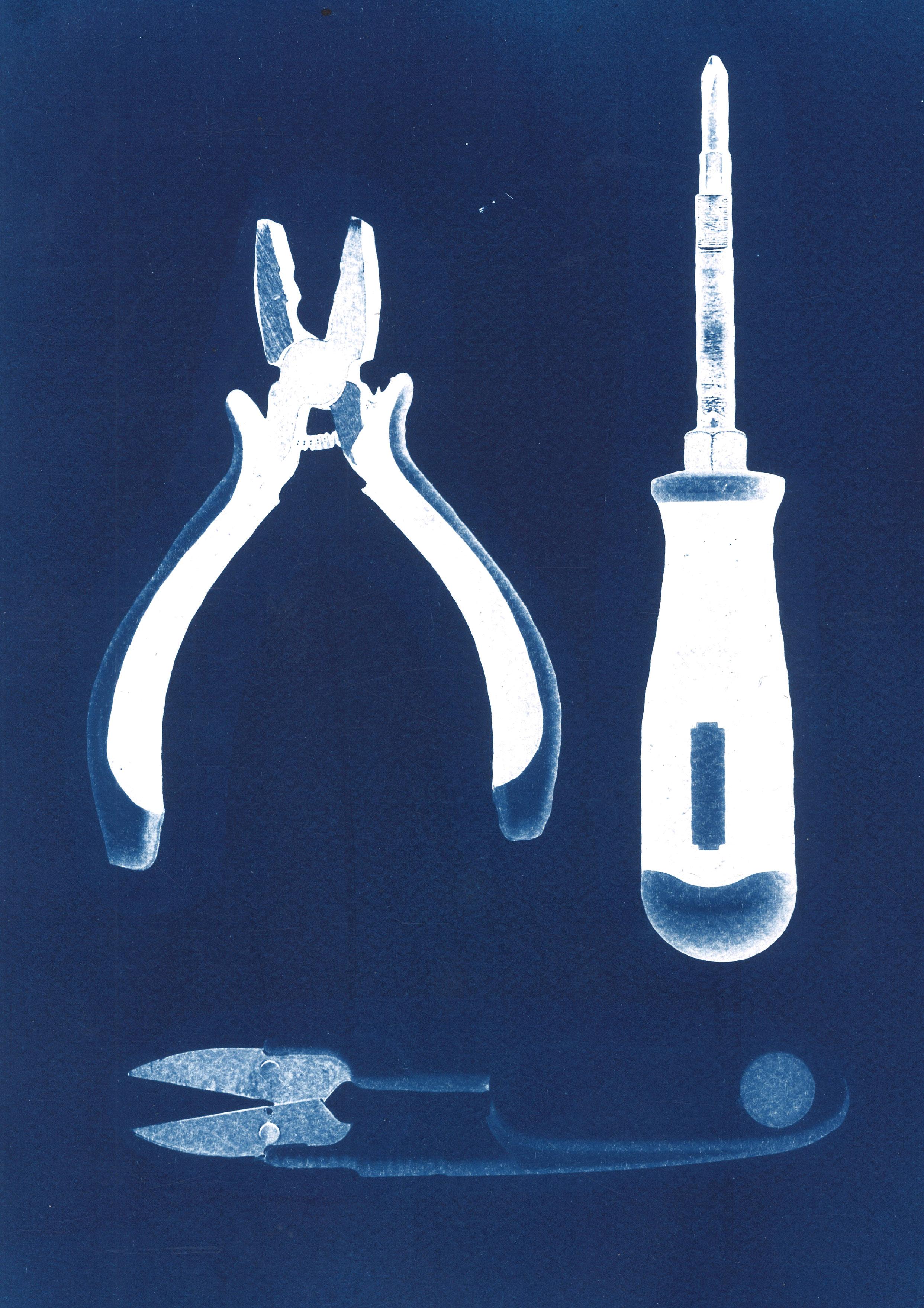

a v e y o u e v e r n o t i c e d t h e s h a p e o f t h e t o o l s t h a t f i t s s o w e l l i n y o u r h a n d

H o w it ’ s twig s weave am o n g s t eachothe r , intertw i n e d , e div ne c e fo h o w i t g r e w . . . H a v e y o u e v er noticedthe s hapes o f t he t r e e s ?

H o w t h e br anc hes endlessly rep

H a v e y o u e v e r n o t i c e d t h e s h a p e o f t h e s h a d o w s ? H ave y o u eve r n o t i c e d the sh ape of t he Groynes ? Have you ev e r noticed th e shape o f thebirds?

H a v e y o u e v e r n o t i c e d

t h e s h a p e o f t h e f l o w e r s ? H a veyou e v er noticed the

Rush weaver, Ella Merriman, is an artist, designer and craftswomen who works in tune with nature.

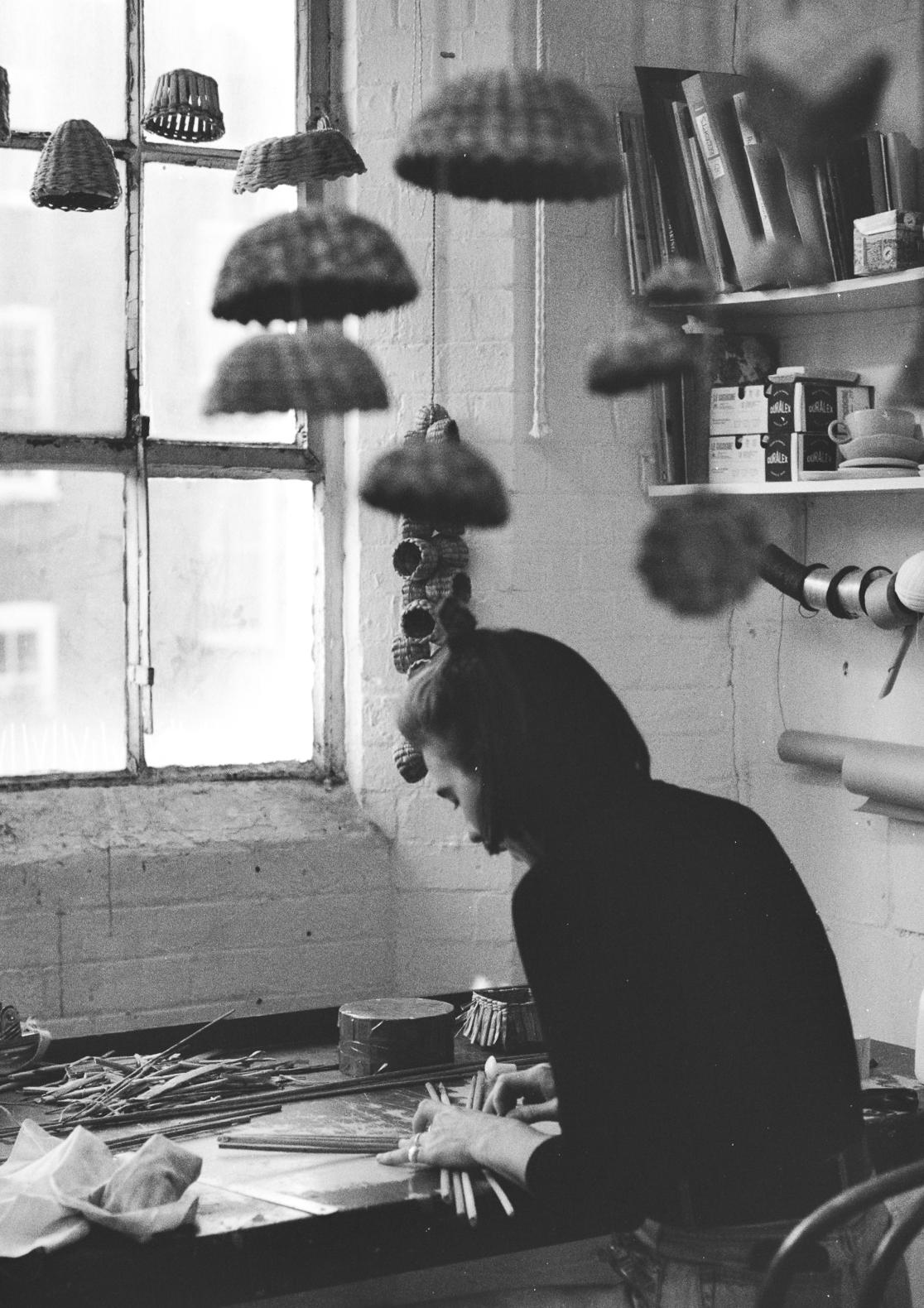

Ella Merriman is a craftswoman, working predominantly in rush, to create innovative basketry pieces, that explores the relationship between humans and plants. We visited Ella in her Holborn-based studio to find out more about how she works with the unique medium.

As you enter the studio you are immediately invited by an earthy smell. A mix of the flowers being dyed by one of the artisans she shares the space with, and the dried rush being weaved into the shape of square basket. Ella’s corner of the room is instantly recognisable, with woven mobiles hanging from the ceiling and bright green (Ella’s favourite colour) rush stems in the middle of the floor, half un-wrapped. Ella has found a second home in Cockpit Bloomsbury studios. “It’s like a proper craft community here.”

Ella’s journey into basketmaking started at Falmouth University in Cornwall where she undertook an art foundation. She then went to Newcastle University to study architecture before dropping out to complete a degree in furniture

making at London Metropolitan University. After university she did a bit of upholstery before owning an underwear company with friends. She’s now found her way back to natural materials. “I did a course at City Lit, which is a small college in central London, and they do short courses. It’s mostly retired people who do them and then there’s me! It was just lovely. It was every Friday with weaving all day. And I just fell in love with it.” It was there that Ella realised this is what she wants to do for the rest of her life. “I had never really been the kind of person who had a specific thing. I always kind of liked making with lots of different materials. And then I found this!”

The sustainable nature of working with rush really drew Ella in. “The fact that I can harvest it myself, it’s completely bio-degradable and doesn’t have a carbon footprint all makes me so happy! If I make something awful, and everyone makes bad things sometimes, it can just go in the compost. It’s so freeing! As opposed to having killed something, damaged something, and made something bad.”

Ella has her own compost at home, that she can take any waste home to. But she still tries her best to salvage what she can, instead of resorting to throwing things away. “I try to save things for something, I just don’t know what yet.”

The rush Ella weaves with, grows in slow flowing rivers. Ella harvests the rush herself with a small group of basket makers, every mid-summer, changing where they harvest from each year. “You have to harvest enough in one go, for the year, which is quite tricky.” Once it’s been harvested it has to dry, which can be awkward as it’s a lot bigger when its full of water. Ella dries it in her grandparents shed. Once its dry, she binds it up and keeps it in her studio. When she’s ready to start weaving, Ella will dampen it with water to soften it up and prevent it from snapping. Ella dampened a batch of rush an hour before we arrived to visit her, as different thicknesses of rush can take varying lengths of time to become malleable.

After Ella moved away from the clothing sector, due to the challenge of doing it sustainably, she found she was much happier making something where she has complete control over the entire process and can use just one material. “Rush has a really interesting history and it’s really interesting to research, and there’s a whole story behind it.”

Rush has been used in England for centuries, but today it is featured on the endangered list of heritage crafts in the UK. Despite being one of the few remaining English rush weavers, Ella is hopeful about the future of craft in general. “High end interior design is using more craft things, which is great. And I hope that is the beginning of a change. I think environmentally we are going to have to start valuing making things more because we can’t just keep importing everything. I don’t know if that’s just me being hopeful. I think the people that genuinely care about craft, really care and that gives me a lot of hope.”

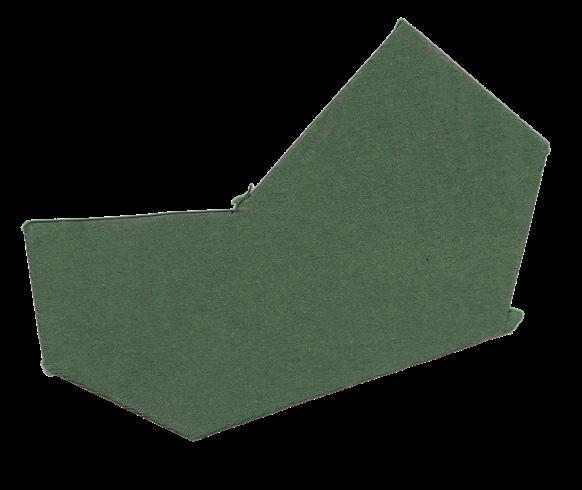

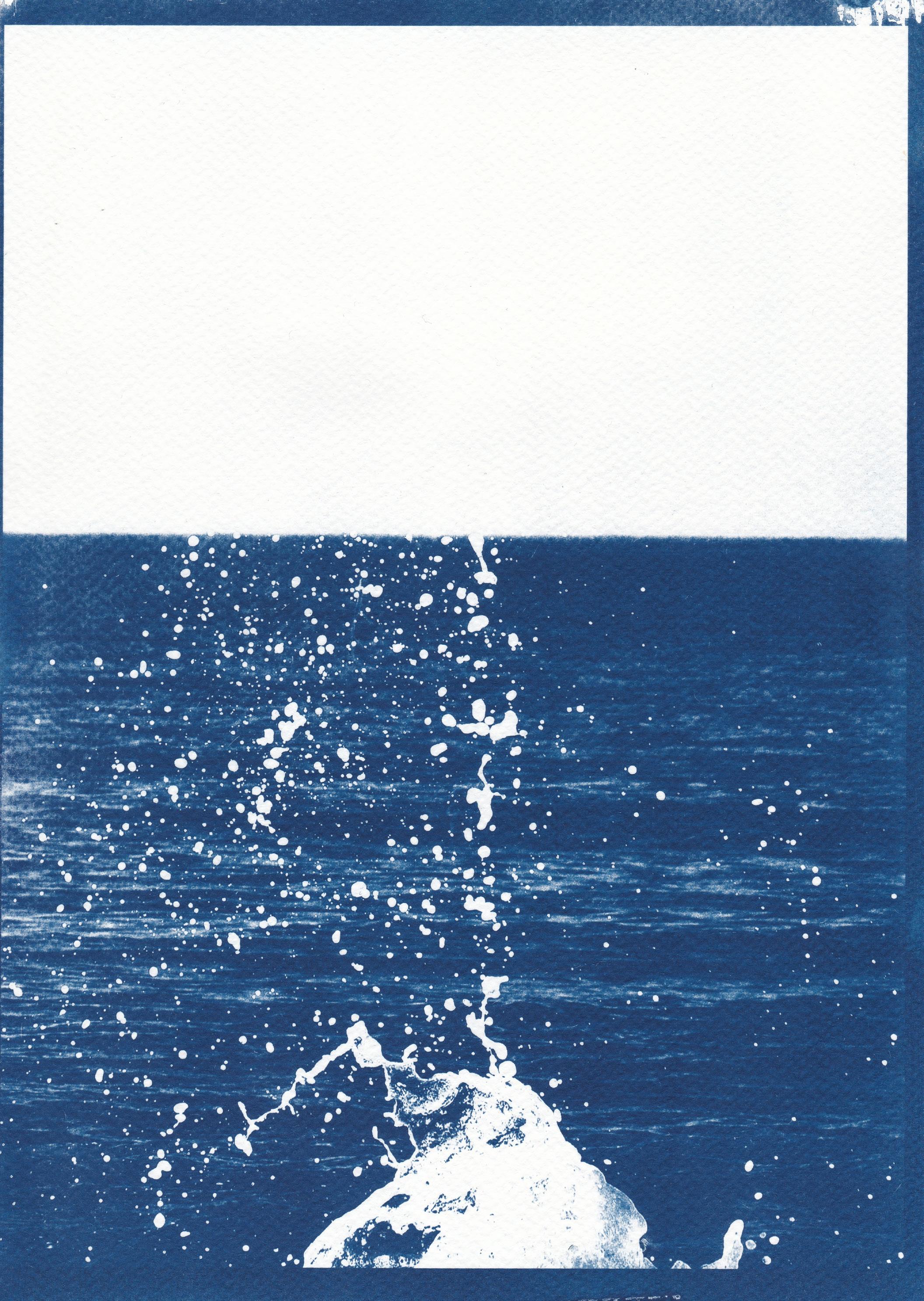

The collection of rush mobiles suspended from the ceiling, crafted from British Bulrush, completely set the tone for the studio. The intricate shapes, weaved by hand, move with the breeze as you walk around them, creating a connection between audience and artwork and bringing a sense of serenity to the space. Rush is a very magical material in craft, as it changes colour over time. Ella is drawn to this dynamic property of the material. “To me it feels like it’s alive.” She hopes that her customers feel the same way. “You buy something alive, and you look after it. The fact that it changes makes it more meaningful in a way.” This idea of the rush being alive and everchanging is what lends it so well to being made into a mobile. “There’s something quite nice about it being suspended, where it can kind of do its own thing.”

Ella finds that ideas for new creations come into her head as full ideas, already knowing what she wants the shape to be. “I think it’s a combination of the stuff you see around you and just picking things up.” Her way of working is a collaboration between the artist and the material, working symbiotically with the plant. “I try to use the rush to its full potential. Certain stems are really fine and certain ones are really thick, and I try to use each one to maximise what it can do.” Ella works in tune with the rush, listening to what shape it’s telling her it wants to be. “Because I’ve taken it from being in a river, and being alive, I feel as though I should have more respect for the material. I’ve seen it being something, growing, I’ve taken it out of that environment and now I’m using it for my own purposes. It makes me want to do it justice.”

Ella’s work explores the disassociation between so many of us and the natural world as well as

the relationship between humans and plants. Working with the rush she becomes aware of the similarities it shares with us humans. “It’s alive and every piece of it is different, in the same way that all of us are different. And in order to make something good you have to work in harmony with it. And I think that is like a metaphor for my work. It is like a symbolism for how we should go about life, in that we should respect all of the life around us.

Weaving is a time-consuming process, and our value of the practice has been brought down with the rise of mass production. It can be a challenge to charge the right prices when society has become disconnected from the understanding of how long it takes to make something. This is something that Ella is currently trying to balance. “You have to find people who care about it enough to spend the money on it, because you can now buy things that are way too cheap.” A set of placemats can take hours to weave, while a set of placemats made elsewhere in the world and imported to the UK can be cheaper than those made with homegrown materials, and crafted in the same country it’s being sold. To Ella this just highlights the sobering fact that someone, somewhere in the manufacturing line is being exploited. “I think doing this has made me way more aware of the value of things. I’ve always tried to shop consciously, but this makes it even more pressing.”

Reading value into woven objects has become increasingly challenging in today’s world. Ella explains how different weaves can take very different lengths of time depending on how close the weave is. A closer weave is stronger but takes a lot longer. A rule that is not always obvious to the untrained eye.

“I try to use the rush to its full potential.”

Ella’s basketry acts as a portal to connect us to nature. With a very tactile quality, visual appeal and earthy scent, they almost transport you to the river from which they were harvested. “We did an open studio here, and it was so nice. People always come in and pick something up. I think people also like the noise of when you touch it, like it’s so crunchy and also there’s the smell, although I can’t smell it anymore.” The sensory presence her work provides makes it well suited to the exhibition format, something Ella is hoping her work will begin to be featured in. She’s now starting to think about making some more lighting pieces, such as lampshades, where the light can peak through the slights gaps in the weave to create some truly magical atmospheres.

Storytelling through considered composition. The intersection of craft and nature.

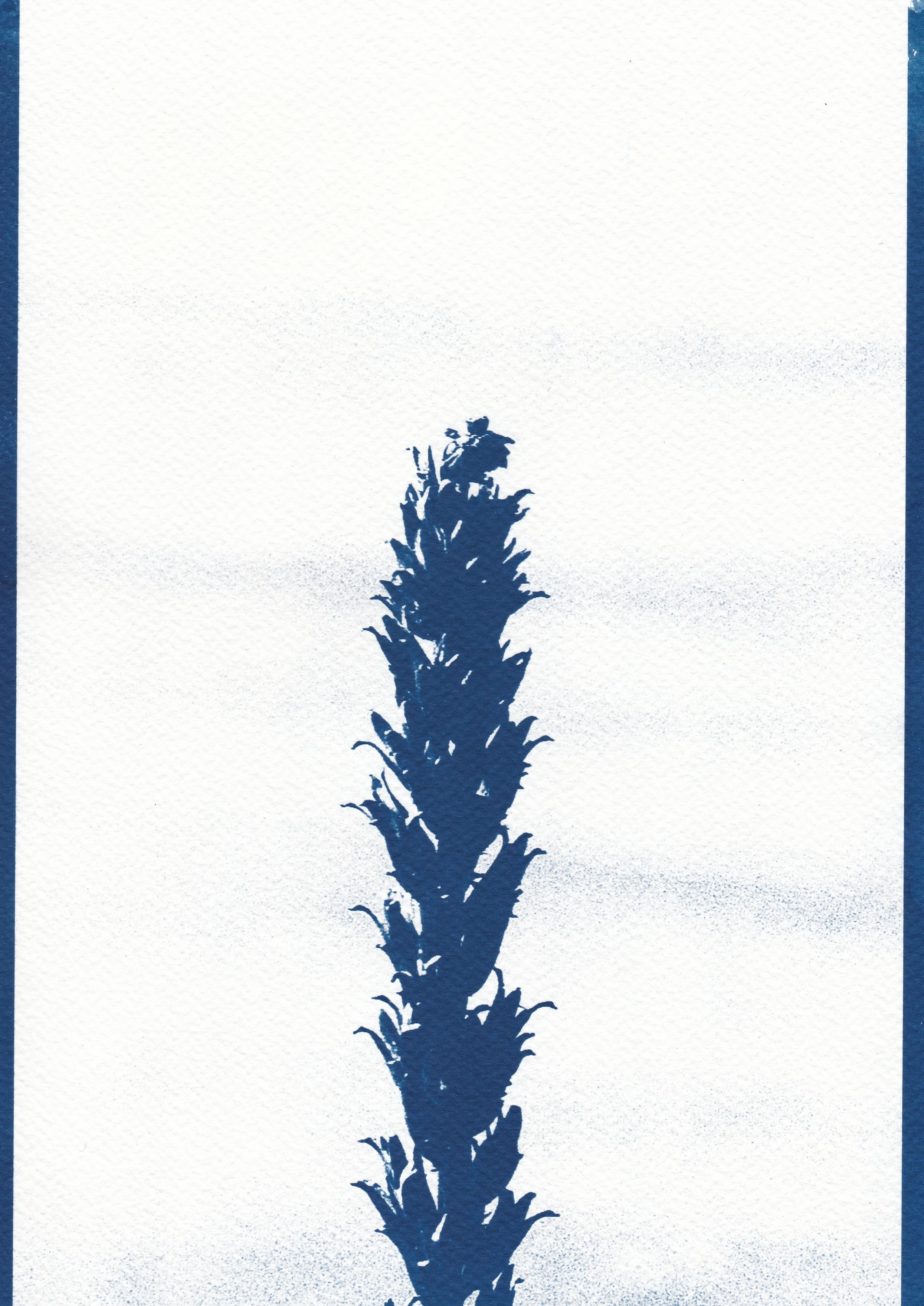

Inspired by the British coastlines, Julie Massie’s tactile pottery explores the pressing issue of coastline erosion.

Ceramics artist, Julie Massie, has developed an incredibly unique and eye-catching pottery process. We visited Julie and dog Rebel in their Dorset based studio to find out more about her creative process.

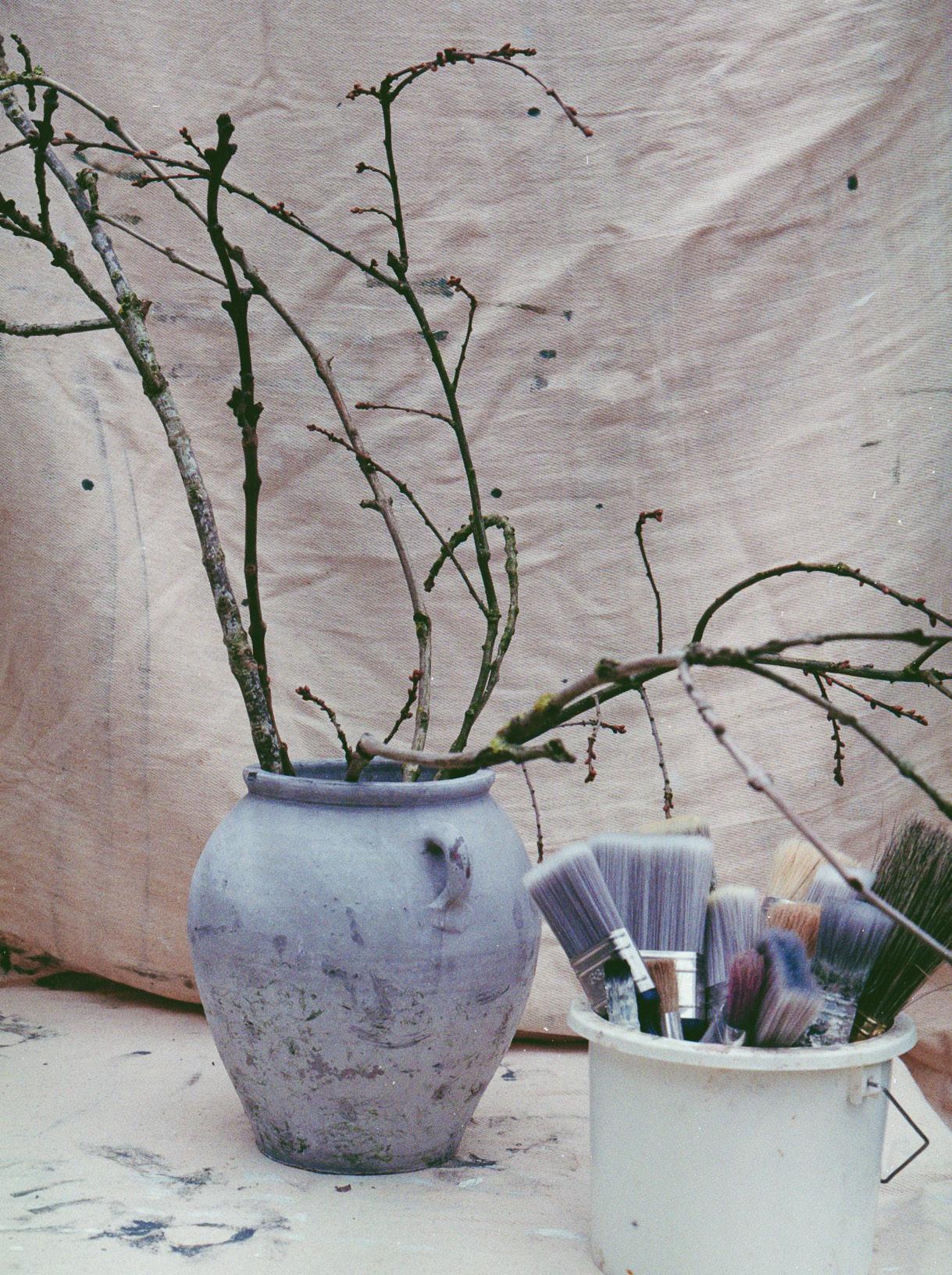

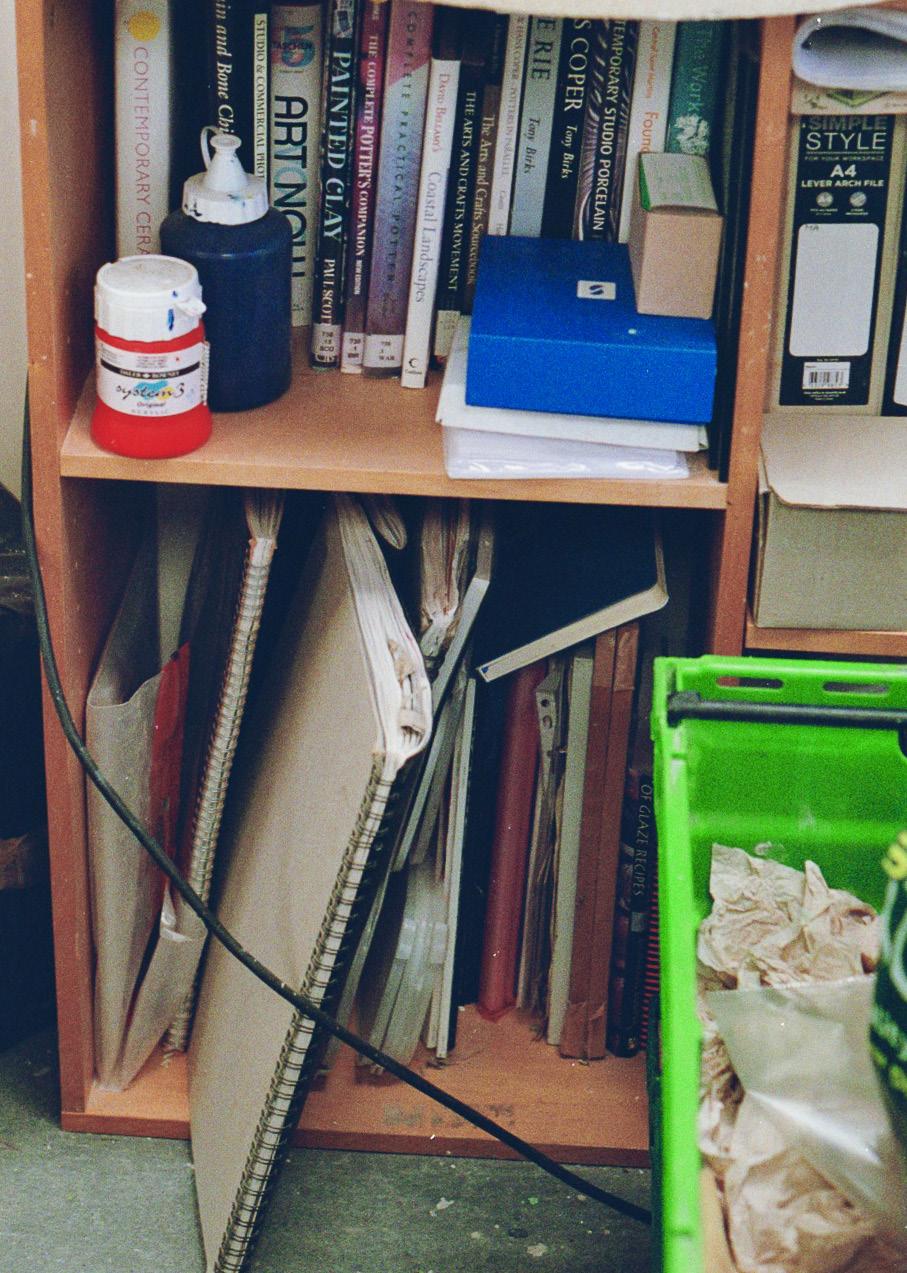

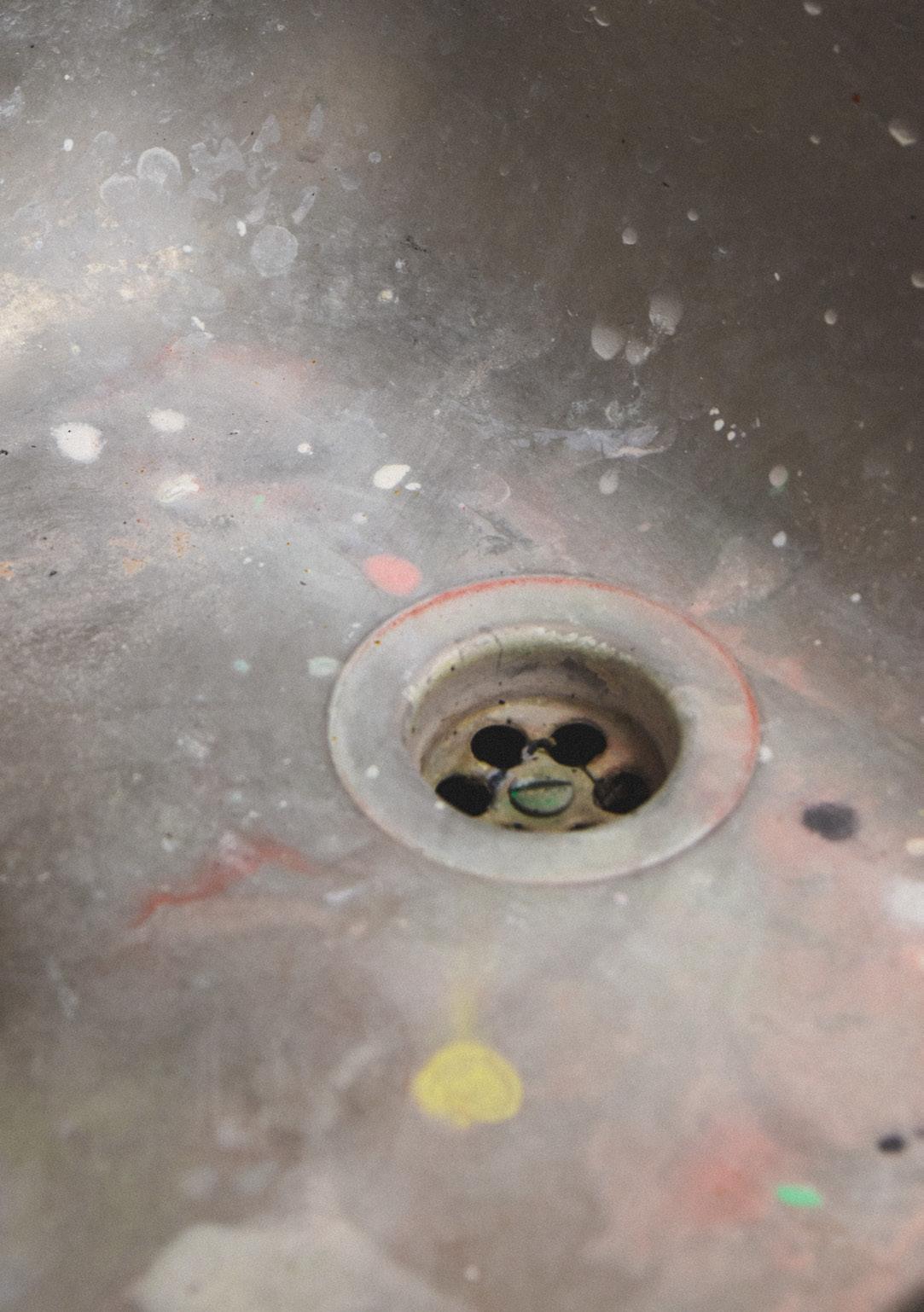

Formerly the garage, Julie’s pottery studio is tucked away from her family home. Fitted with open windows, natural light floods the room and bounces off the few glazed vessels. Filled with sketchbooks, brushes, clay, stains and splattered with paint marks, this atelier is the perfect space to engage with all thing’s porcelain.

Since graduating from UCA Farnham with a master’s degree in ceramics, Julie has developed a refined craft process that draws inspiration from fragility and dynamicity of Dorset coastlines. She looks at the sea at different times of the year, the day and in different weather conditions. The colours are composed to reflect the hues of the seaside during those differing times. The result is an abstract visual where a body of colour seamlessly blends throughout the artwork.

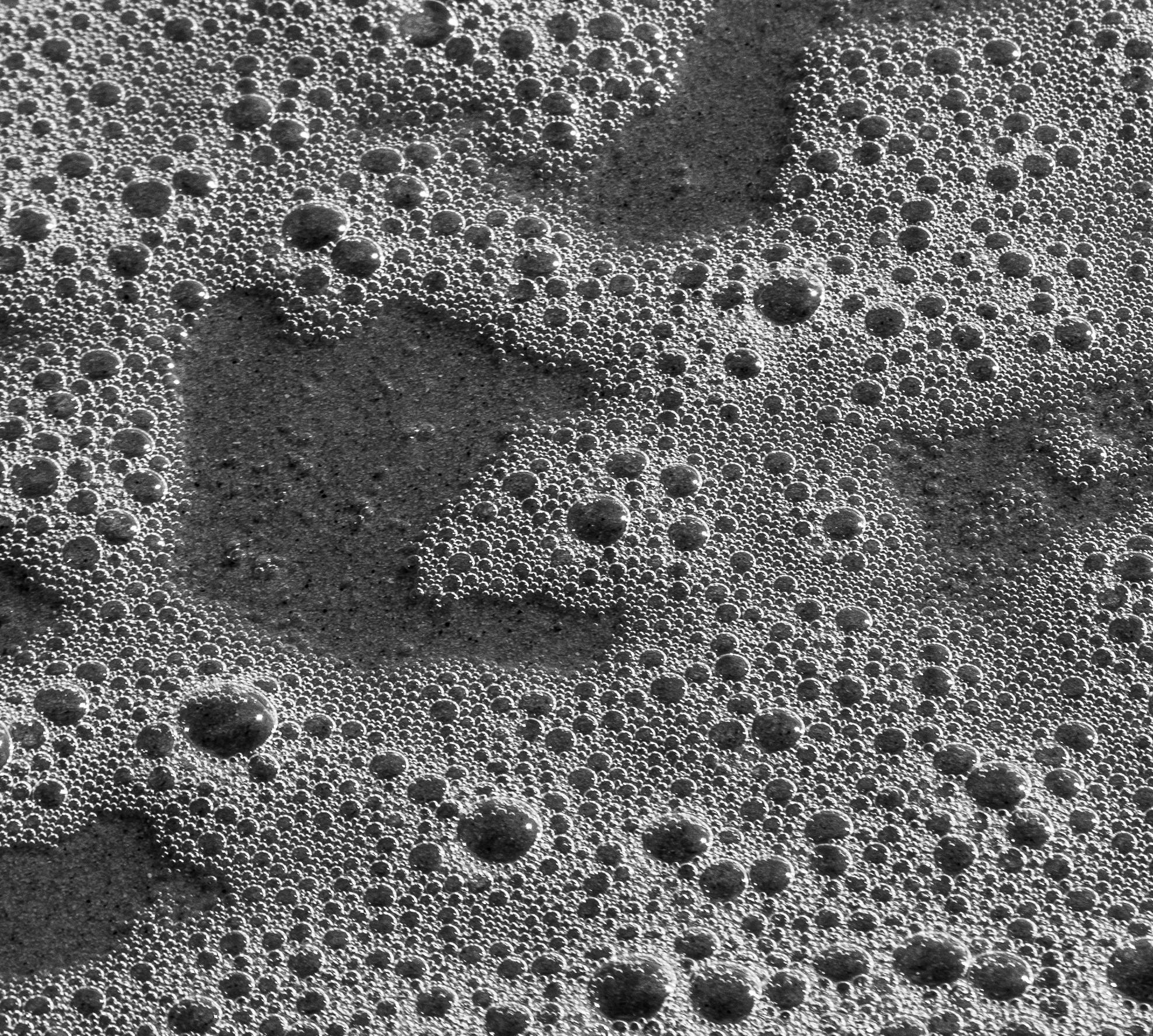

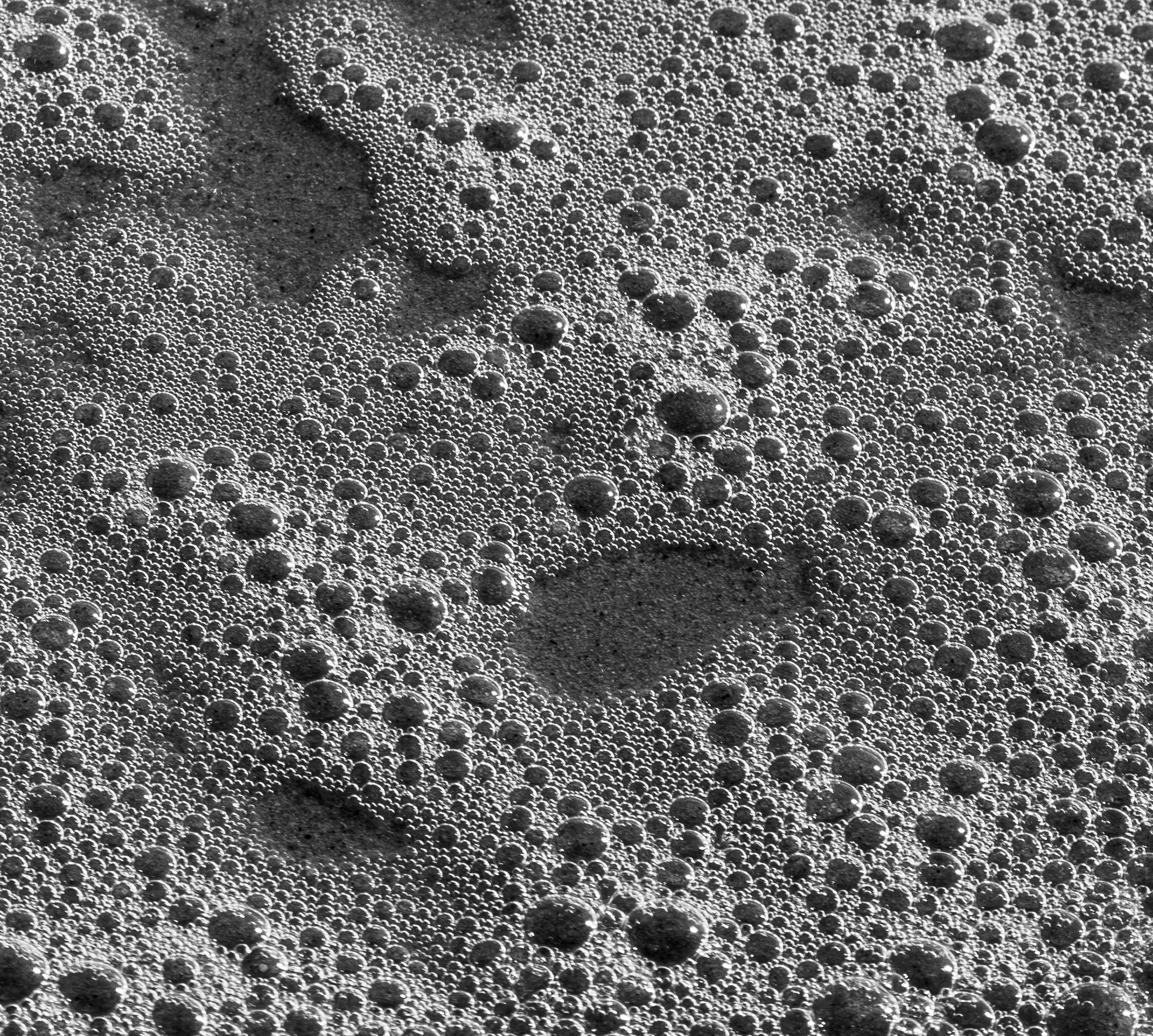

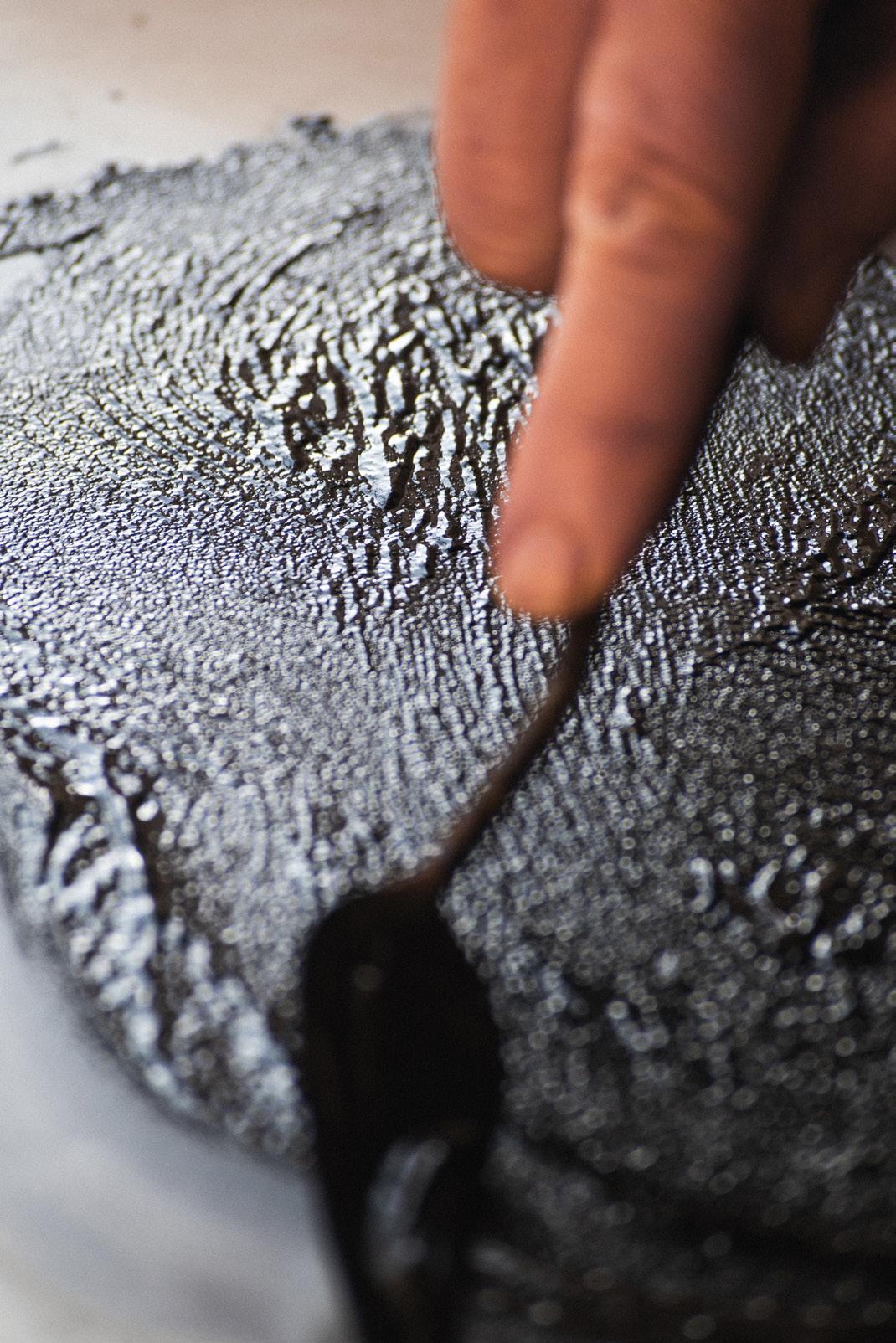

Julie’s process starts in a sketchbook. Photographing the coast, and then exploring colour, texture and pattern through watercolour illustrations. This then transpires into 3d ceramic artworks. Working primarily with porcelain clay, Julie begins the making process by staining the liquid body of clay, using precisely measured out stains to achieve a specific hue and tone. The clay is dried and rolled using a slab roller until it is unbelievably thin. It is then cut to size using a baton and knife before further thinning the edges by pressing down on them with her thumb. These fragile strips of clay are then fired in the kiln at 1260 degrees before revealing the vibrant results of the staining process. Finally, the strips are individually snapped apart and then mounted into a hand-built frame using tile adhesive and a pair of tweezers.

“A LOT OF PEOPLE, DON’T KNOW IT’S MADE FROM CLAY. THEY MIGHT THINK IT’S PAPER. I WANT TO MAKE SOMETHING THAT PEOPLE DESIRE TO TOUCH. THEY WANT TO KNOW WHAT THE SURFACE FEELS LIKE.”

Julie discovered this process through trial and error while making a pot for her masters. She started staining her work with cobalt carbonate which makes it very fragile and can cause it to start disintegrating. She grew frustrated when some strips she was making, to go around the pot, kept falling to bits. So, she got a piece of wood and set them in the round. Those pieces ended up getting selected for the Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition and placed in their catalogue. But Julie has always wanted to explore these intricate thin edges through her work.

There is a clear link between medium and message. The incredibly fragile nature of porcelain clay and the thin edges of Julie’s artwork speak to the erosion of our coastlines, a natural process proliferated by climate change and rising sea levels.

Julie’s work speaks out on our respect for the coastline. “When I was doing my MA, I went to Kimmeridge Bay and looked at people chipping away at the slate cliffs and not respecting the fragility of the coastline”.

T h e grey s k y , The blue s e a , The f r o th y wav e s , C oming o n to th e s a n d y shore

The tactile nature of the artwork is very intentional and considered. “A lot of people, unless I’m at a ceramics fair don’t know it’s made from clay, they might think it’s paper. I want to make something that people desire to touch. They want to know what the surface feels like.”

When exhibiting her work, Julie often asks for the work to be placed at eye level, encouraging touch and creating a greater connection between audience and artwork. Her work has always been interactive in nature. During her MA, Julie exhibited a ceramic pot with a hammer next to it, encouraging people to break it, and observing our fear to interact with art.

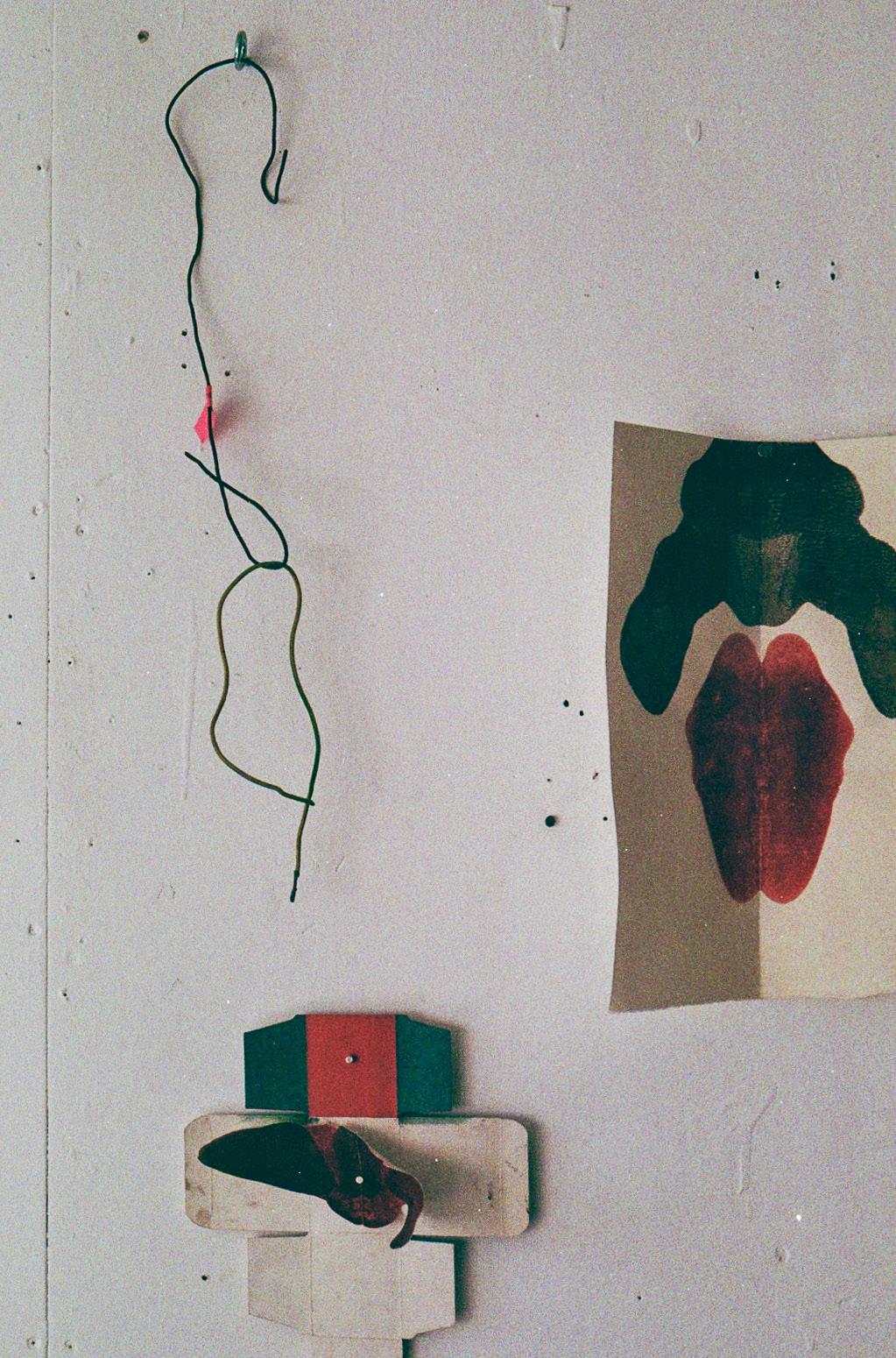

She is currently working on a new piece inspired by the coastline at night. A process that starts by painting the pages of the sketchbook black, before drawing and painting the coastline at night. She has now begun work on this piece, exploring the use of black porcelain which will be built into a frame alongside white porcelain pieces to create a striking monochromatic composition. We cannot wait to see the final outcome!

[Synaesthesia]

The production of any sense impression relating to one sense or part of the body by stimulation of another sense or part of the body

Can you feel texture of without touch? Can you feel with your eyes?

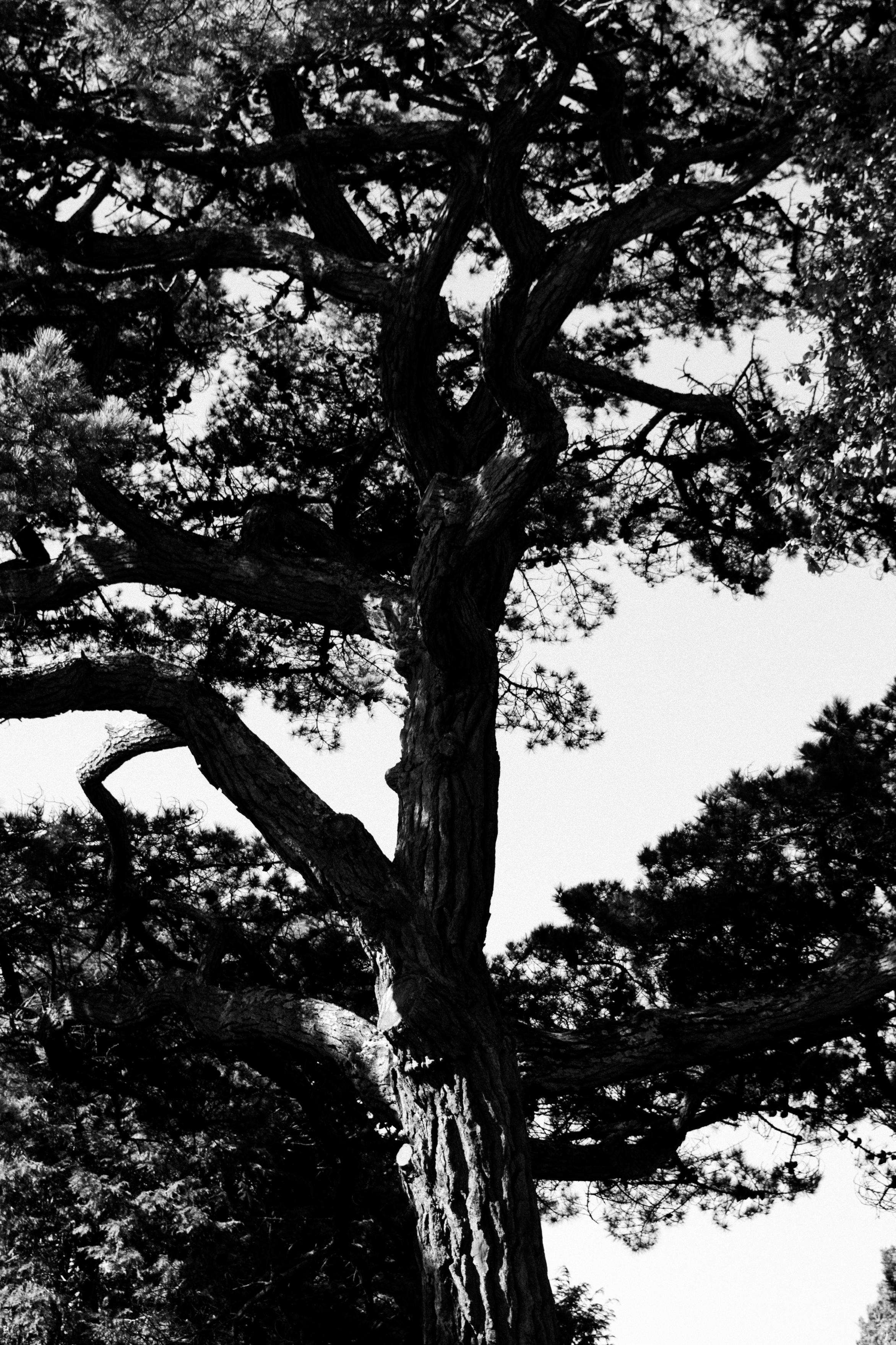

NATURE CHANGES OVER TIME, JUST LIKE PEOPLE. ALL TREES COME FROM A SEED,

YET EACH ONE GROWS TO BE UNIQUE. THEY ARE CHANGED BY THEIR ENVIRONMENTS AND BATTERED BY THE ELEMENTS, BUT THEY CONTINUE TO G R O W

TH E T ID E S

OUR SENSES ARE HOW WE ENGAGE WITH THE

Print and paint artist, Sam Hodge, works closely with matter to explore our entanglement with the material world.

Sam Hodge is an artist, working with print and paint, to tell stories that connect us directly to the materials she works with. We visited Sam on a sunny January morning, in her East London based studio, to find out more about her grounded practice. The sound of children playing in the local primary school and the kettle warming up sounds in the background as Sam makes a cup of coffee and tells me about her venture into print and paint.

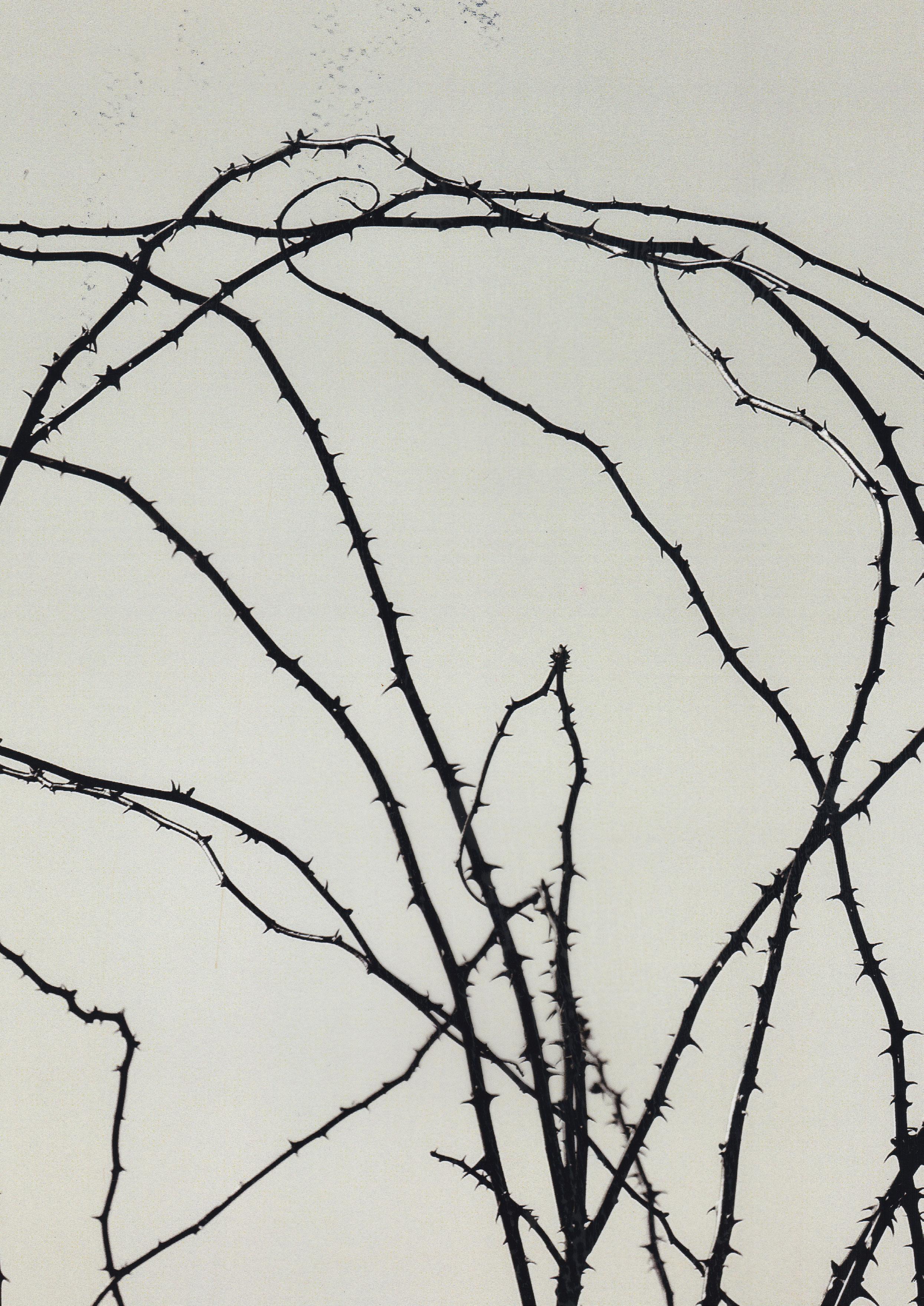

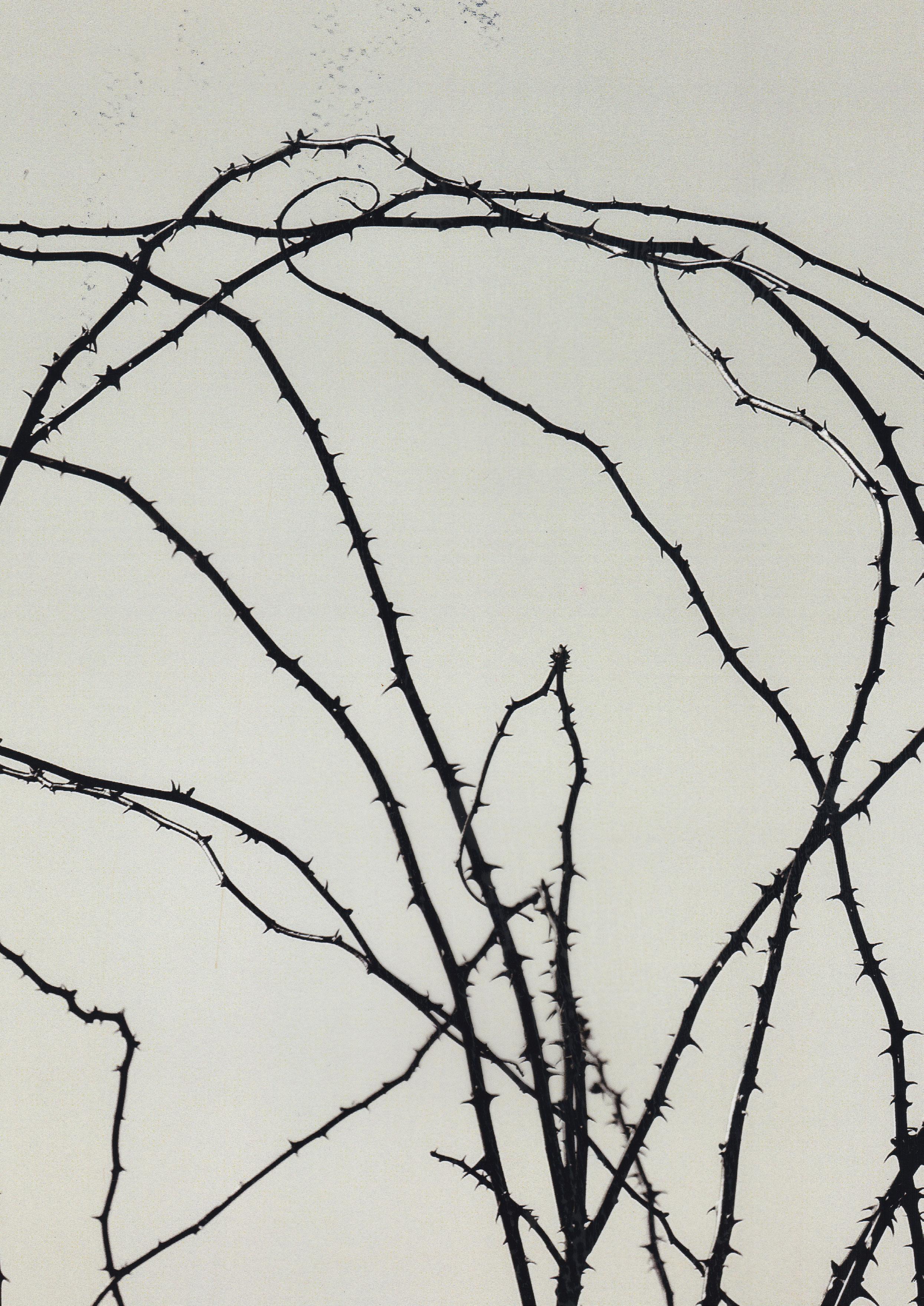

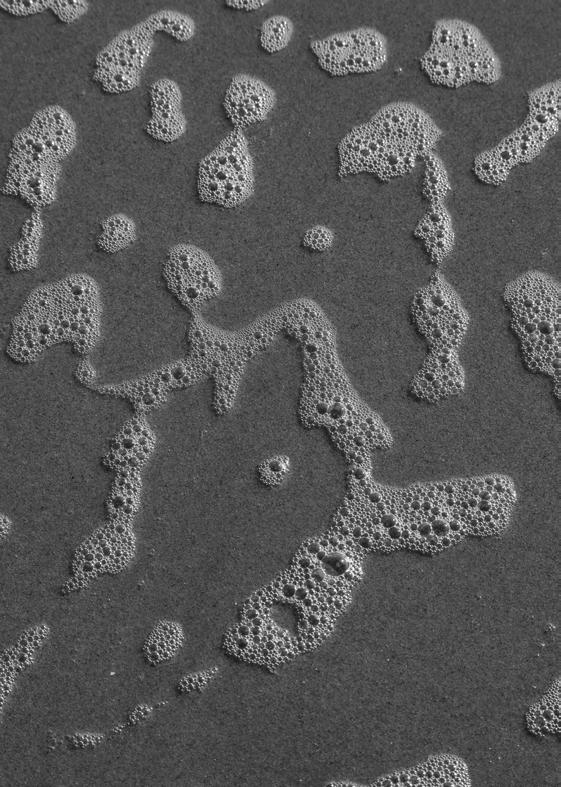

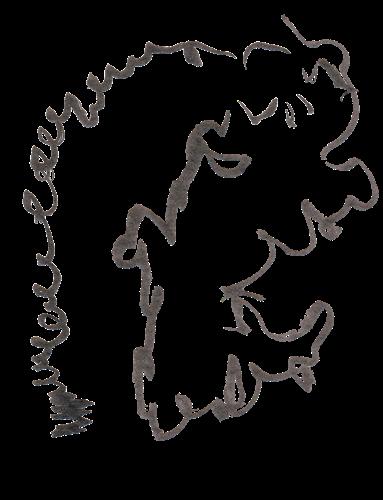

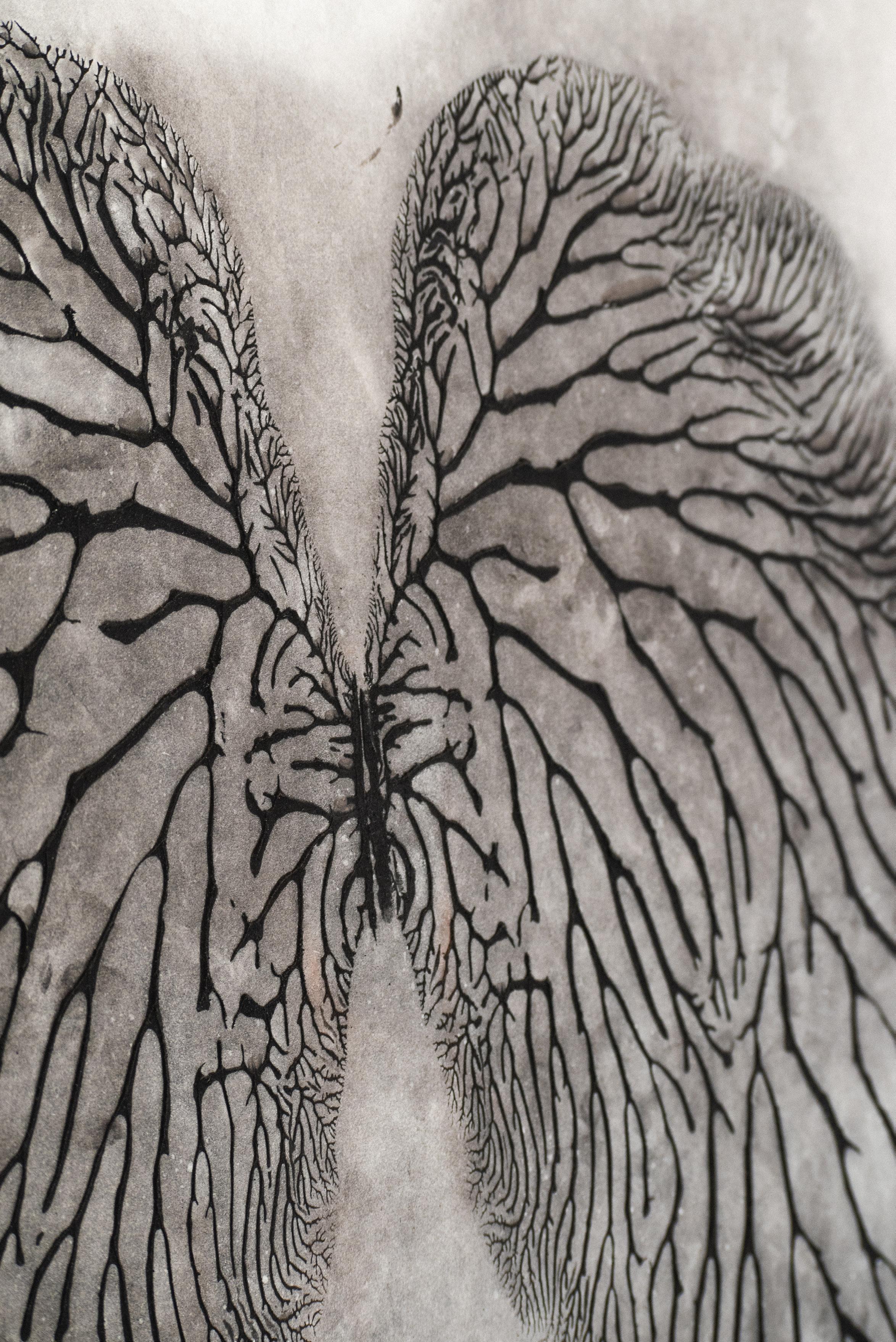

Sam studied a Natural Sciences degree at Cambridge University initially before becoming a painting conservator. She came to art slightly later in life but still carries those biological images from her degree in her head. These beginnings to her career have laid the foundation for her work today, which concerns materials and how they behave both in her studio in the longer term. The incredible branching patterns, which are a recurring theme in Sam’s work, come from a purely physical process of squashing and pulling apart. “I’m really interested in how that physical process can make something that looks so organic. And this makes you realise that all our bodies and all of biology is also physical and we emerge from material interactions in the same way these patterns do.”

“THESE

THAT ARE SO BIOLOGICAL,

Sam’s series titled ‘Dendritic Printing’, features those fractal, branching patterns, and bear resemblance to both human and plant anatomy, reminding us how the two are interconnected. They are created by squashing and pulling apart paint medium and taking a monotype from the pattern of ridges formed. “I discovered these patterns when I was a painting conservator. In conservation you grind your own pigments and make your own paint. I’d lift these tiny glass mullers, and there’d be this lovely pattern

on the bottom. I just thought ‘oh my god, that’s so incredible, that these detailed branching patterns, that are so biological, can happens so simply’. I think that these fractal patterns do draw the human eye, and there’s something about them that’s very intriguing.” If you take a moment to look for them, you might just find you see these patterns everywhere; , inside your own body, in the trees, in roots, in river systems, on all different scales, and within all different materials.

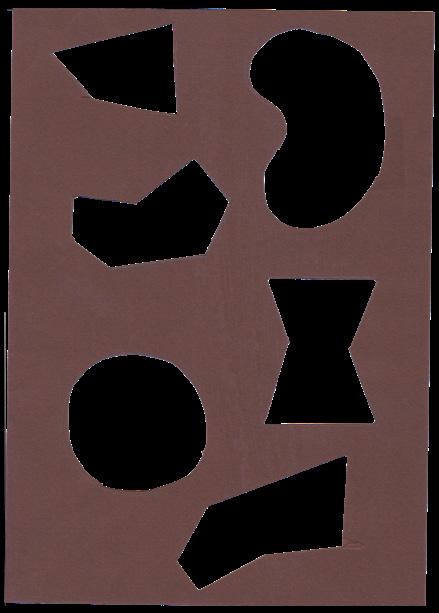

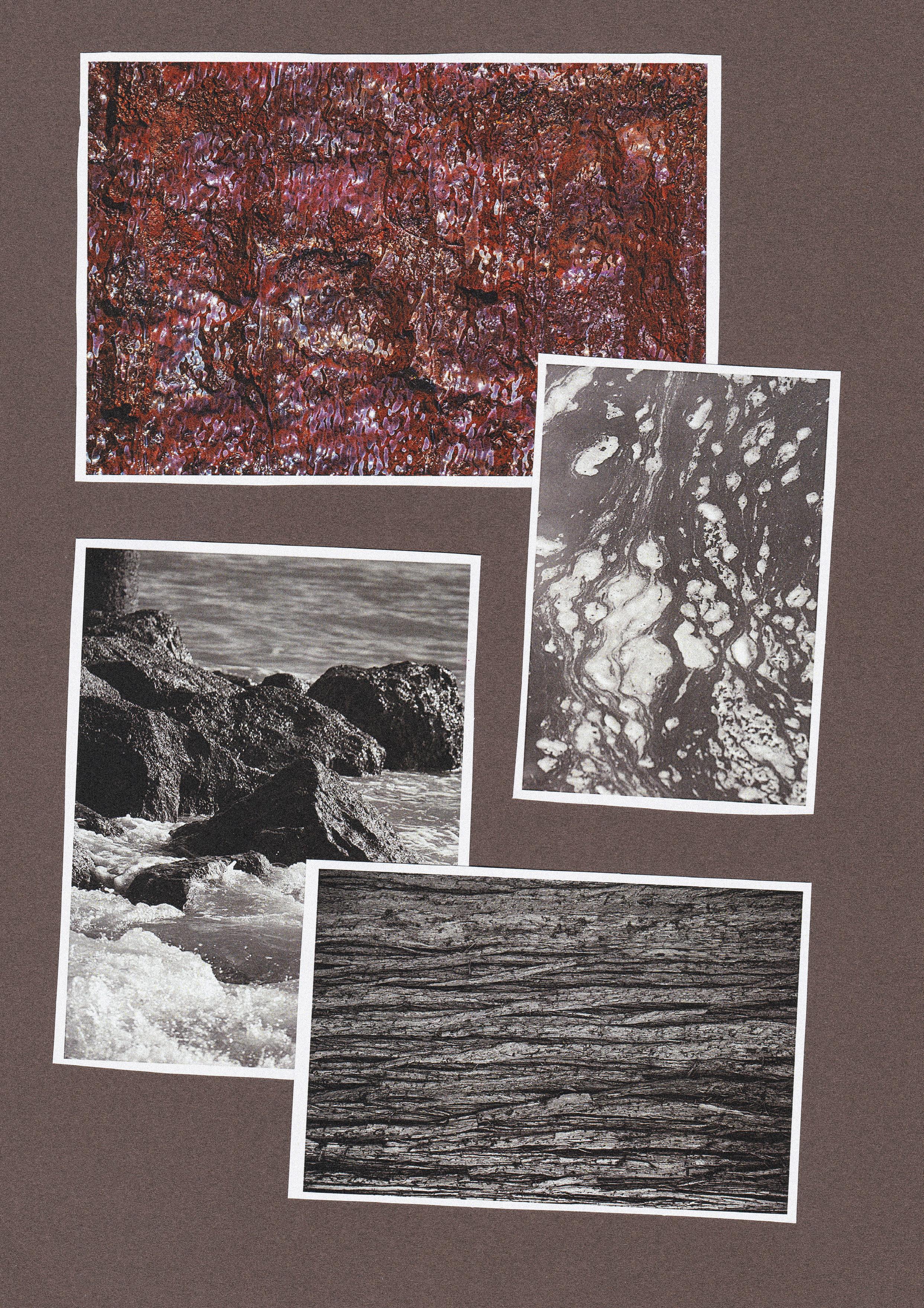

In the corner of Sam’s studio is a collection of various materials that Sam has foraged for. Including, stones, bones, seaweed, rusty metal and a cardboard model of a mammoth. “The mammoth is there because mammoth bones were recently found on the beach in West Runton, coming out of the cliff. I’m constantly thinking about all the things that come out of the cliffs, whether it’s human made things, or the flints, or the earths, and the mammoth bones. I’m currently thinking about what to do with it. It was from Muji originally, and I might deconstruct it and make something out of the shapes of a deconstructed mammoth.”

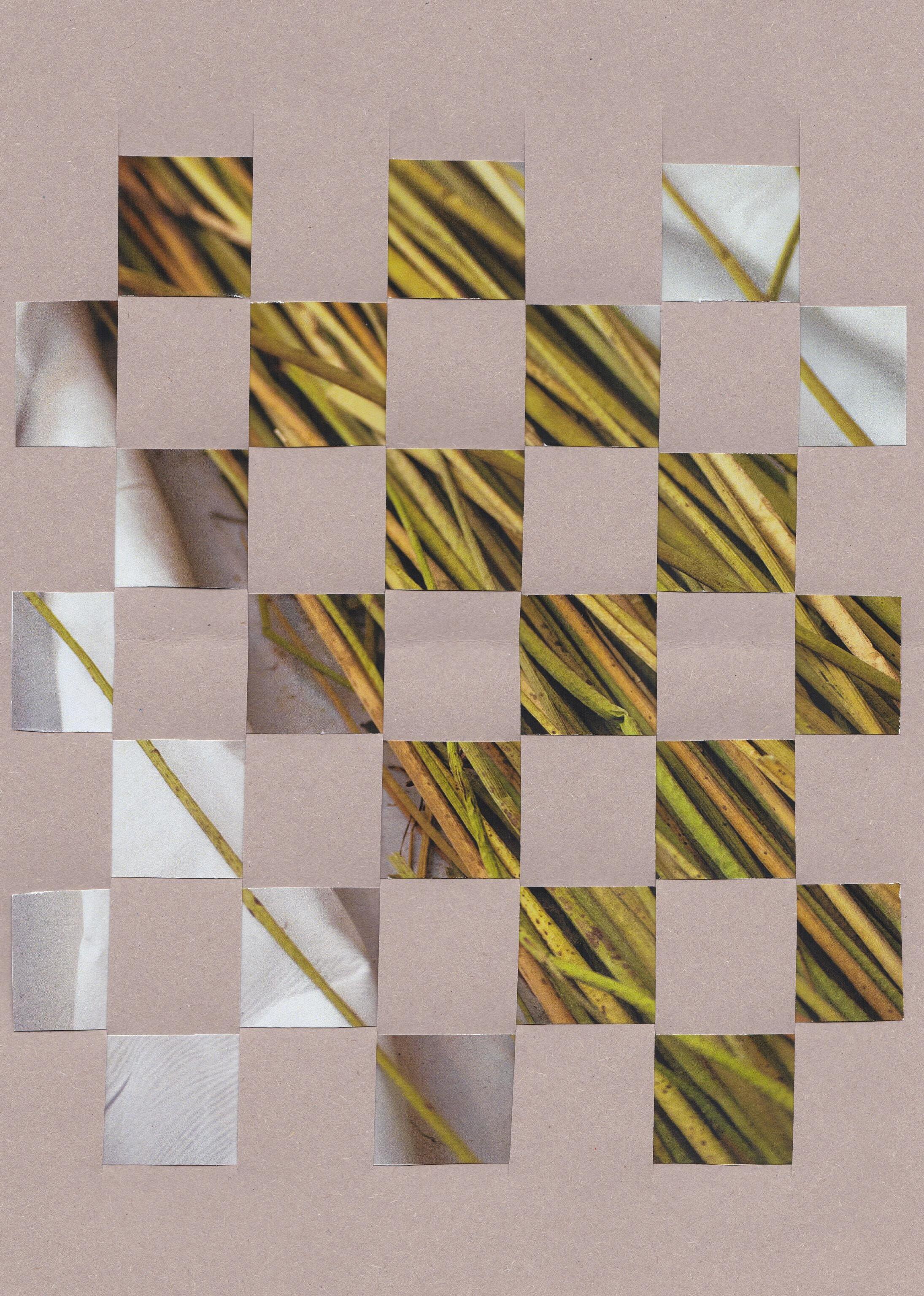

Sam’s inspiration comes from a deep interest in materials and our connection through materials to the environment. But she also draws inspiration from how materials change over time – how they transform. She often works with pieces of human-made rubbish or debris to make pigments or to directly print with. Her series Pelagic Plastic where photopolymer etchings of translucent scraps washed up on the beach and collected by Sam. Her series titled ‘Unfolding’ features a series of prints of unfolded packaging from Sam’s own recycling bin, printed with ink made from natural pigments, made using earth gathered on her walks around the British coast. Sam is interested in how human rubbish becomes part of the environment. Her pigments are often made from bits of houses that have fallen from cliffs as they erode or copper piping, for example.

Sam sources her materials for pigments from coastlines, the River Thames and even spaces like building sites. The collage (on the left) from Sam’s ‘Out of Aldgate’ series was made from materials foraged from a building site around Aldgate. Despite using found materials the results are striking and bold colours, that do embody natural tones but aren’t restricted to neutral and pastel palettes. As Sam describes them they are “as strong as any commercial paint, but slightly more subtle as well.”

“The blue comes from copper wiring, soaked in vinegar,” Sam explains as she holds up a fascinating looking jar. “Those blue crystals are formed from the reaction between the fumes from the vinegar and copper, so it’s making a copper acetate crystal that you can then make into a pigment, or you can directly use the water at the bottom to make an ink.” The collages incorporate ink from birch bark and brick dust too! “It’s interesting how you can make art from things you can just find in the street.” At the top of the collage a marbling effect has formed where the birch ink has mixed with the copper ink and begun to react and change colour. “I like that idea that they’re actually changing on the paper.”

Her work explores the interaction between human and nature made, and how the two come together. “I’m thinking about material history when making my work. “I’m thinking those bits of iron where originally a rock, and then they were made by humans into iron, and then they were made into a house, and then the cliff receded and the house fell into the cliff and now I’m making them into a pigment and mixing them up with other rocks from that area that are millions of years old and have their own histories and over a much deeper timescale.” Sam spends a lot of time thinking about different timescales and comparing deep time with human time. As she crushes a rock in her studio to turn it into a pigment, she is transforming them in her own timeframe. The materials will react on the paper as she works, and she responds to those reactions. “There’s a kind of human-material interaction going on, in the timescale of what’s happening in the studio.”

The process of making her own pigments has meant Sam has really slowed down and become much more conscious around the making process. She no longer buys any pigments and is beginning to think more and more about what she is buying and extracting from the earth. “I’m still extracting in a way, I’m still picking things up, but it’s just on a much smaller and more personal scale.” Making her own paint has made Sam slow down. Sam can spend a day making inks that can be used up by the end of the next one. “Instead of being able to just buy a tube and squeeze it all out and make as many prints as you want you are kind of slowed down, and you’re realising what it takes to make something. So, it puts you within a more physical relationship with materials.”

As well becoming more considered with how she uses materials, Sam has also become more in tune with the materials themselves. As she grinds her materials with pestle, she becomes aware of the hard properties of the rock. She then begins to think about how a miner in the Northeast of England likely mined this specific piece of coal. “They literally went down a hole and cut this out, and then somebody else put it into a boat and transported it to London, and then it helped fuel London’s growth. Then there’s another timescale, thinking back to when the coal was made by the forests, which were one of the first explosion of plant life on earth and made these coal seams. These coal seams changed the climate because they absorb so much carbon from the atmosphere and put deep underground. Then jumping forward, we changed it back by digging it up and putting it back into the air. So, you’re having all these thoughts when you’re dealing with the material, which you wouldn’t have if you just went and brought a tube of black ink.”

Sam’s images tell stories of the materials used and draws attention to the nature of these transforming things. “The history of the coal gets into these painting because you can’t help but think of the coal and what it did to people’s lungs; to the miners, and the people burning it in London, and the huge power stations like the Tate Modern belching out coal smoke everywhere. Something about the material history of the materials you’re using to make the work, end up being in the work somehow.”

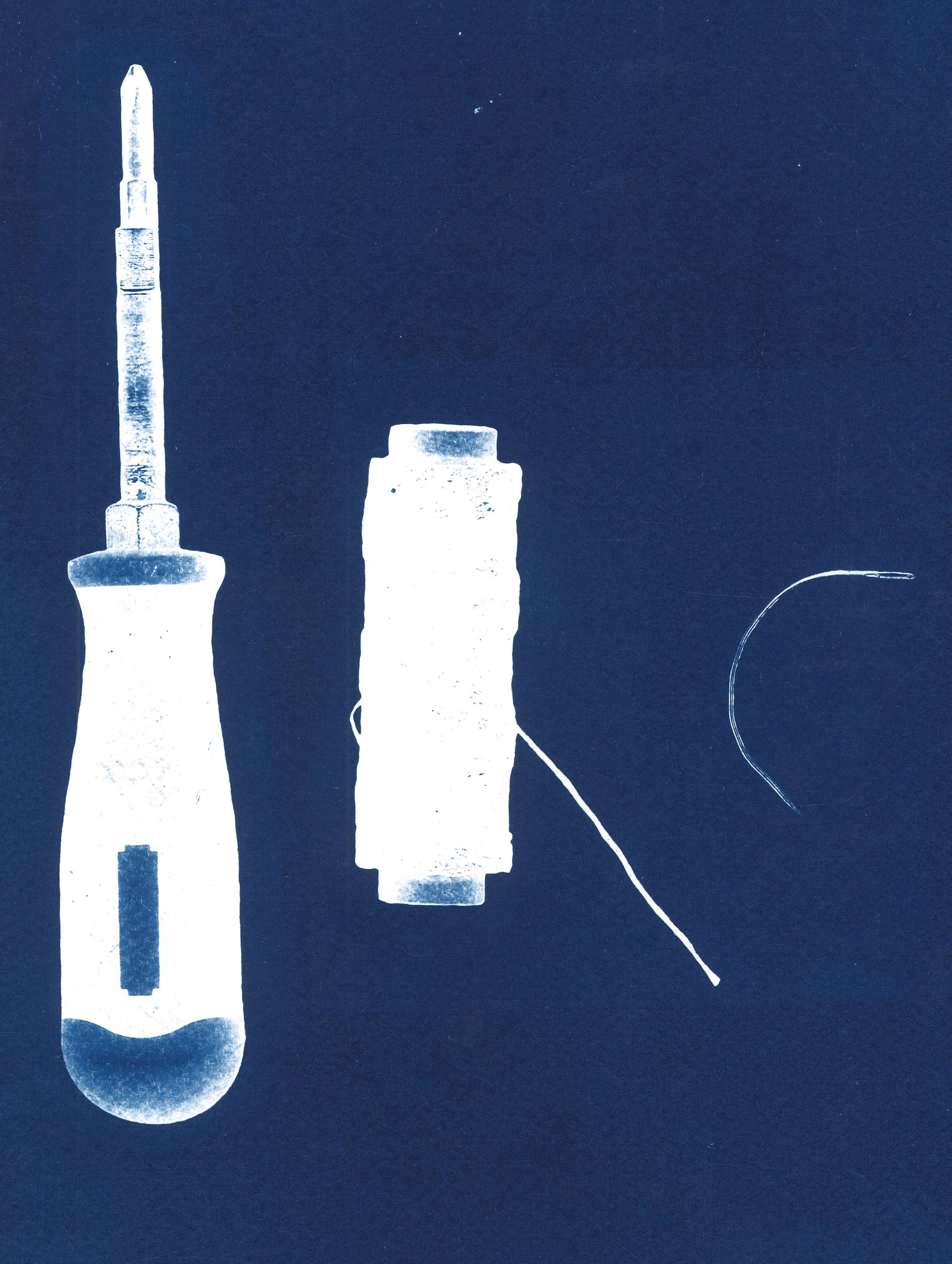

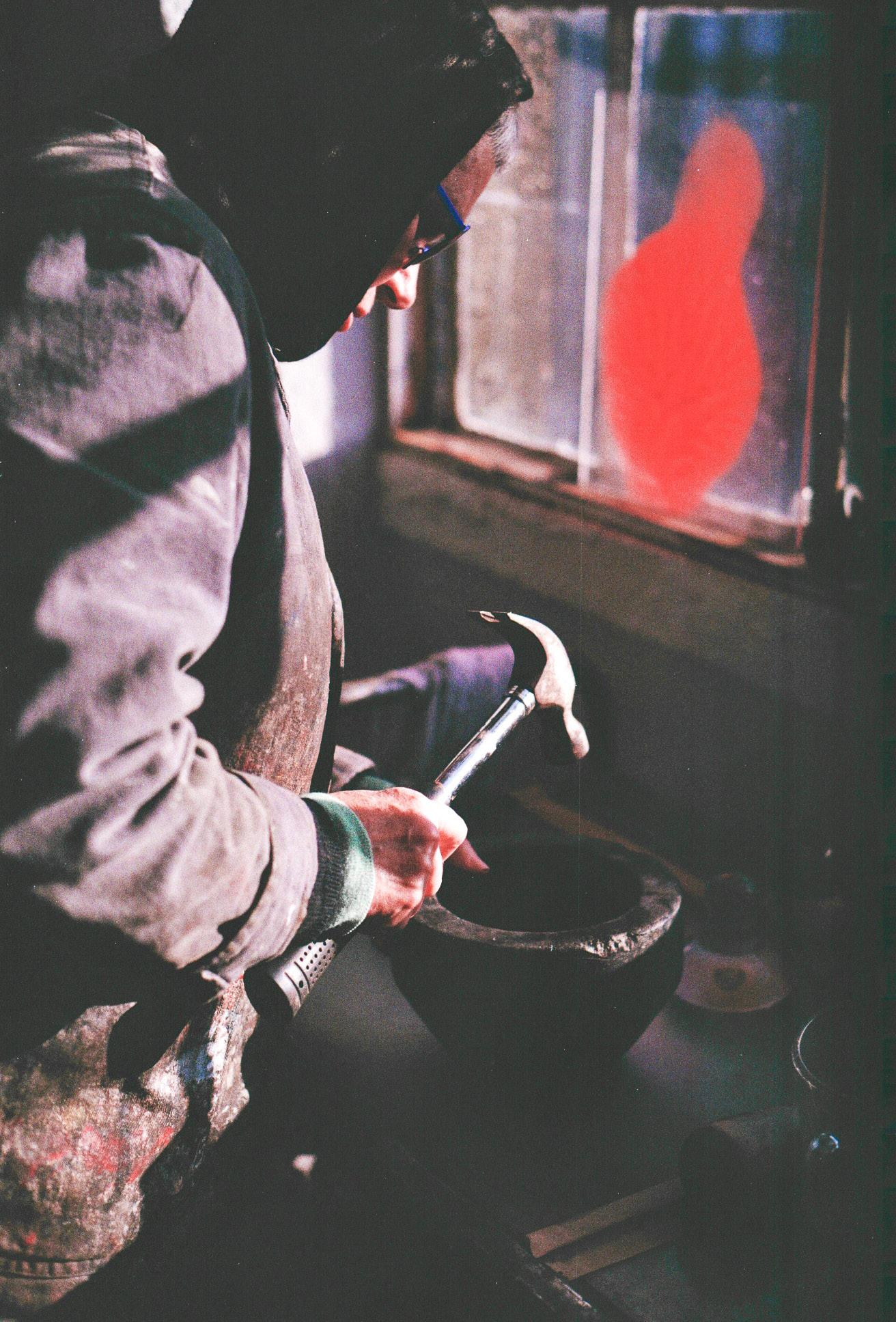

To make the pigments and paints she prints with, Sam starts by gathering and foraging for materials that can become sources of colour. This includes natural earth and plants, or human made matter, such as copper wiring, rusty metal and bricks. Sam also works with materials discarded by humans into the River Thames and washed up on its shoreline. Here Sam is working with coal sourced from the Bankside in London, next to the Tate Modern Gallery which previously was a coal-fired power station. There’s lots of coal in the Thames, so it’s easy to find and the river washes it up in long lines. The water accumulates things of the same weight and type, so its sorts them into different groups meaning all the coal comes together.

Different materials require different processes to be transformed into inks and pigments. Sam starts by crushing the coal with a hammer before grinding it into finer pieces using a pestle and mortar. “I love my stone mortar because it’s so much stronger than various ceramic ones I’ve had before. You can’t crush rock in the ceramic ones because they snap. I found this stone one in a second-hand market.”

She’ll then sieve the dust through a series of ceramic sieves, each finer than the previous, until the coal dust is fine enough to make paint out of. This stage is a repetitive process of working it through the sieves then going back to grinding with the pestle and mortar. She then transfers the dust into a pot, labelling it with the material and how fine it is.

She then mixes the dust with a binding agent, in this case caligo oil, using a muller and glass plate. As she mixes them together it transforms from a gritty substance to a silky and smooth paint. “This is where I first noticed these fractal patterns, as you squash and pull apart you create these amazing suction patterns. These oil-based paints don’t work as well though when making these patterns, water-based mediums are more suitable.”

Sam then meticulously transfers the paint into an aluminium tube to store. Once in the tube the end is rolled to seal it. When it needs topping up it can be unrolled and re-filled again. Sam finally labels the tube. “This little tube will then go on to develop 8 or 9 prints - it goes far. But you become so much more aware of what you are using, as so much effort has gone into making the materials themselves.” Sam made this paint for carborundum printmaking, which is a much more forgiving technique that doesn’t require paint to be overly smooth.

Although this process is slightly repetitive, Sam enjoys it and the hands-on nature of working. “I’m usually listening to podcasts and music. Sometimes it’s a pain because I think I just want to get on with printmaking, but I have to spend ages making ink first. But actually, I think it’s quite nice to be slowed down in some ways. It’s like cooking, the whole process is very satisfying.”

As Sam’s practise has evolved it has become increasingly process focused. “I sort of switched from doing quite representational drawings and paintings of landscape and things, to making much more use of the process of painting itself to make the image. And then moving onto making the paint aspect of the image. And so, the emphasis has gradually shifted much more to the process, and the materials and what they can do. The power of the materials has become more interesting to me. I’ve moved away from drawing, but I do still draw for fun. There is more of a mastery over materials involved in drawing rather than working with them.”

Sam’s background in painting conservation has meant that she has spent a lot of time being a workwoman behind the scenes. She has a lot of respect for those who, like her, make things with their hands and have a lifetime of expertise. She believes that there needs to be a shift away from throw-away culture and instead become conscious of what and how we buy, consuming things with personal meaning made to last a lifetime.

Find out more about out featured artisans

Instagram: @ emmabondillustration

Website: emmabondillustration.com

Website: ellamerriman.com

Instagram: @ juliemassieceramics

Website: juliemassie.co.uk

Instagram: @samhodgeart

Website: samhodge.co.uk