A Residential School Memoir from Nunatsiavut

As told by Nellie Winters

Transcribed and edited by Erica Oberndorfer Illustrated by

Qinuisaarniq (“resiliency”) is a program created to educate Nunavummiut and all Canadians about the history and impacts of residential schools, policies of assimilation, and other colonial acts that affected the Canadian Arctic.

Published in Canada by Inhabit Education Books Inc. | www.inhabiteducation.com

Inhabit Education Books Inc.

(Iqaluit) P.O. Box 2129, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 1H0

(Toronto) 191 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 301, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 1K1

Design and layout copyright © 2020 Inhabit Education Books Inc.

Text copyright © 2020 Nellie Winters

Illustrations © 2020 Nellie Winters

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law.

Printed in Canada.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Reflections from them days : a residential school memoir from Nunatsiavut / as told by Nellie Winters ; transcribed and edited by Erica Oberndorfer.

Names: Winters, Nellie, 1938- author.

Identifiers: Canadiana 20200159275 | ISBN 9781774502075 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Winters, Nellie, 1938-—Childhood and youth. | LCSH: Inuit—Newfoundland and Labrador— Labrador—Biography. | LCSH: Inuit children—Education—Newfoundland and Labrador— Labrador. | CSH: Inuit—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador—Residential schools. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC E96.65.N6 W56 2020 | DDC 371.829/971207182—dc23

ISBN: 978-1-77450-207-5

I dedicate this book to everyone who comes and asks me things and trusts me to tell stories. It takes a while for things to come back in my head, but it’s good memories when I get to talk about it. Thank you all for reading my stories.

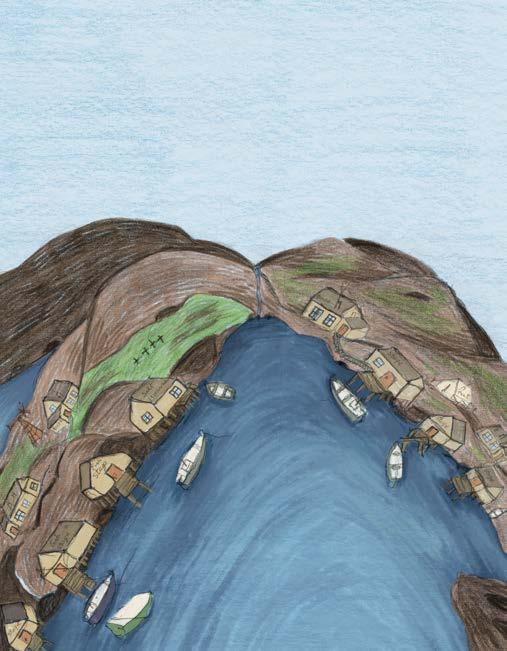

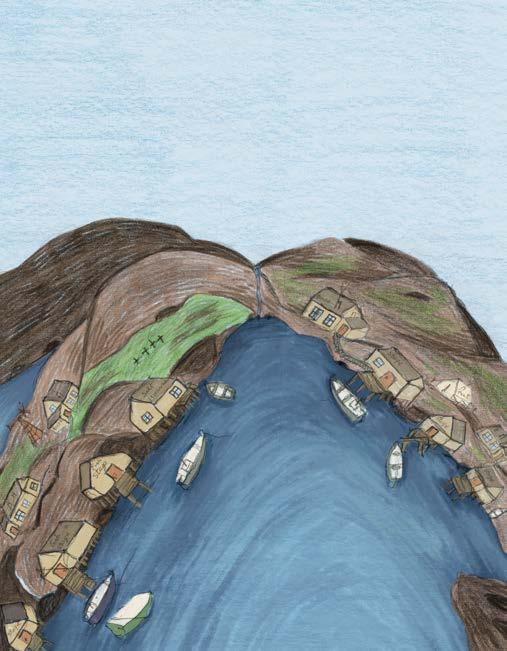

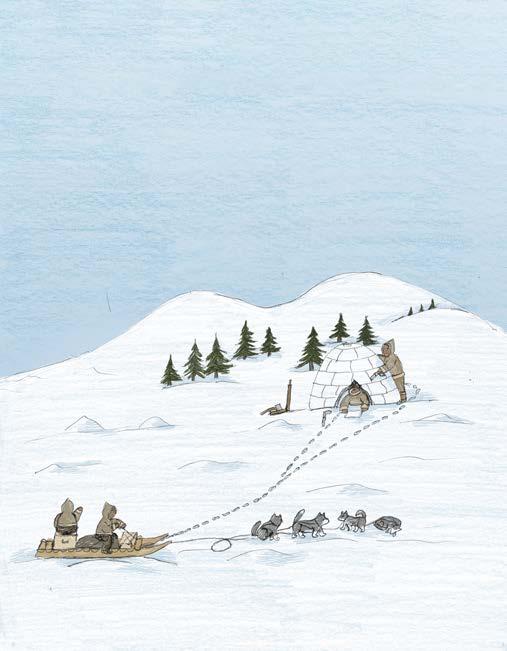

This book is about the personal experiences of Elder Nellie Winters at residential school in Nain, Labrador. Alongside these stories are memories of her childhood home of Okak Bay, on the north coast of Labrador, in what is today the selfgoverning Inuit region of Nunatsiavut.

Aunt Nellie was born in Okak Bay in 1938. Her parents were Hans and Jane Andersen, and they had eight children: Andrew, Samson, Jessie, Bonnie, Nellie, Harold, and sisters Maud and Mildred, who passed away before Aunt Nellie was born. Her family’s winter home was at Okak Bay. Each summer

Aunt Nellie and her family would move to Cut Throat Island, about 30 kilometres east of Okak Bay, to fish. Many other families from the town of Nutak joined them there for the

fishing season, before everyone returned to their own winter homes in the fall.

As Aunt Nellie describes in her memoir, children were traditionally educated by their families by living and working alongside them, actively developing knowledge and expertise. There were, however, accumulating pressures for families to send their children to residential schools. On the north coast of Labrador, Moravian missionaries wielded strong authority and influence through the church, and they operated two residential schools: one at Nain, and one at Makkovik. The provincial government increasingly viewed traditional harvesting economies as stuck in the past and pushed programs and services—including education—toward developing a centralized wage economy.

When the Dominion of Newfoundland (including Labrador) joined Confederation in 1949, the family allowance became available to residents of Canada’s newest province. Though the family allowance made a significant difference to the well-being of the whole family in regions where people were paid little, and often unfairly, for their work, it was also a tool to ensure full-time school attendance, because otherwise it would be withheld. Many families also genuinely hoped that an education at residential schools would benefit their children in future years.

There were no schools in Okak Bay, or Nutak, or in any of the small bays or islands where families lived all

along the Labrador coast. The closest residential school was the Nain Boarding School 400 kilometres to the south, run by Moravian missionaries in the community of Nain (in Labrador, residential schools are often referred to as “boarding schools”). In 1949, when she was 11 years old, Aunt Nellie left her home of Okak Bay to attend the Nain Boarding School. It was her first time away from her family, her neighbours, and her home.

Aunt Nellie attended the Nain Boarding School until the spring of 1951. After her time at residential school, she went home to live with her family in Okak Bay. She lived there until 1956, when the provincial government ordered the closure of the communities of Okak Bay and Nutak. All residents were forcibly relocated to communities farther south, and the same happened again to residents of Hebron in 1959. Aunt Nellie and her family were relocated to Makkovik, where they had relatives. She has lived in Makkovik ever since.

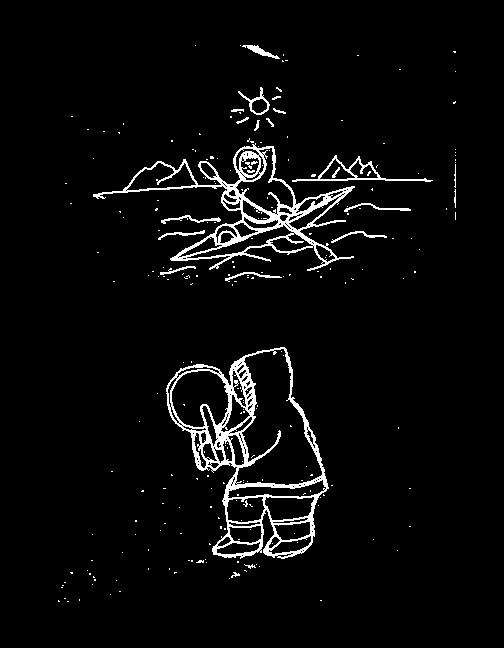

I first met Aunt Nellie in July 2012, when I visited Makkovik to begin work on my PhD. As well as being extremely knowledgeable about plants—my area of interest— Aunt Nellie is a highly respected artist. Aunt Nellie always has a pen and paper handy, and when we visit she often draws a picture as a way of explaining a story or idea in more detail.

One day as we sat together, she opened her everpresent sewing box and pulled out a stack of papers filled with inukuluk drawings. Inukuluks (inukuluit), or “little people”

Reflections from Them Days

in Inuttitut, are designs that are frequently embroidered on tablecloths and clothing, featuring everyday scenes such as people berrypicking or playing games. The scenes depicted in these drawings were different. Using inukuluks, Aunt Nellie had illustrated memories from her days at the boarding school in Nain.

That day, and over the following year, Aunt Nellie told the stories that lived in each of these drawings. We audiorecorded these stories, and I transcribed her words when I was back home in Goose Bay. During the next visit, we would go over the printed transcripts of the previous visit, and new details would emerge, as well as new stories. Aunt Nellie made more drawings and told more stories, I made more notes, and so we continued. And that is how this book came about.

I asked Aunt Nellie why she began drawing scenes from her time at boarding school, and why it was important to her to share her illustrations and stories with others. She replied:

I have eleven children—Pearl, Bella, Dinah, Sonny Boy, Polly, Dorothy, Doreen, Irene, Blanche, Randy, and Harold—fifty-six grandchildren and greatgrandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren. It’s good for children to learn the stories from long ago, how we lived back them days, when we had no TV, no phones, nothing. Back them days, work and learning was our pastime. In boarding school, it wasn’t always good, but

whatever we went through we learned a lot. Others had it worse than us. If I don’t share my memories, my own children won’t know the stories. This book will keep it in their memories too. Even for people who don’t know me, I hope my story is interesting to them. It’s like reading any other books about people in other places. I really get interested, even if I don’t know who they were or where they were. If people can learn anything from my stories, it’s that we’re put on Earth to do things, and to make the Earth more wonderful. We’re meant to help others, especially Elders, and help others to do things.

Aunt Nellie is the best kind of storyteller. In one sentence she makes you laugh, and in the very next sentence she makes you cry. It has taken a deep well of courage to relive some of these memories and to speak them aloud. That Aunt Nellie still finds a way to share these memories with humour and love says everything about her mighty spirit.

With love to Aunt Nellie for this gift to all readers,

Erica Oberndorfer Goose Bay, Labrador

My name is Nellie Winters. I was born in Okak Bay. From fall to spring we lived at our home in Okak Bay, and then in the summer we would go to our fishing place at Cut Throat. This is the story of my home, and when I had to leave home to go away to the boarding school at Nain.

In Okak Bay we was five families. But then down Pretty Point there was more, and up in the cove from us was more people—about another four families. The Onaliks stayed down below Pretty Point. They was like a second family to us. Aunt Lena Onalik was a midwife. She was special to us, because she’s the one who borned me and my brother Harold. We called her Inuatsuk. She called me Annaliak, and called brother Harold Angusiak. The Onaliks always came to our place for

Reflections from Them Days

Christmas. We spent a lot of good times with them, and also with the Lyalls.

Our house was the biggest one in Okak Bay. They built it from all the logs that my dad and his real good friend, old Aba Kojak, used to saw up with these old pitsaws and make houses from it. In our house, there was me and my brother Harold, my dad and my mum, and my sister before she left. My sister went away on a fishing schooner from Cut Throat. The big house with the garden was our house.

We used to have little old benches put out from in the house, and I could look right out to Pretty Point and down

Inuatsuk: A term of endearment.

Annaliak: A midwife’s name for a girl she delivered.

Angusiak: A midwife’s name for a boy she delivered.

around. We could walk across the river when the water fell, when the tide went out. We could look out to Dad’s Island where we’d put our nets. He’d row over there two or three times a day. We’d get a lot of whabbies too. We didn’t used to waste stuff. Even the whabbies: we’d skin them and salt all the wings and the legs, salt them in barrels and soak it in the winter, same as the trout. It’d be really good. And the bodies of the whabbies, they’d just dig a hole and bury it for the dogs. The ground was so cold that when we dug it up it’d be just the same as when we put it. Sandy, see? They’d have to wash off the sand.

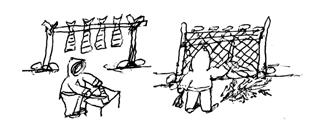

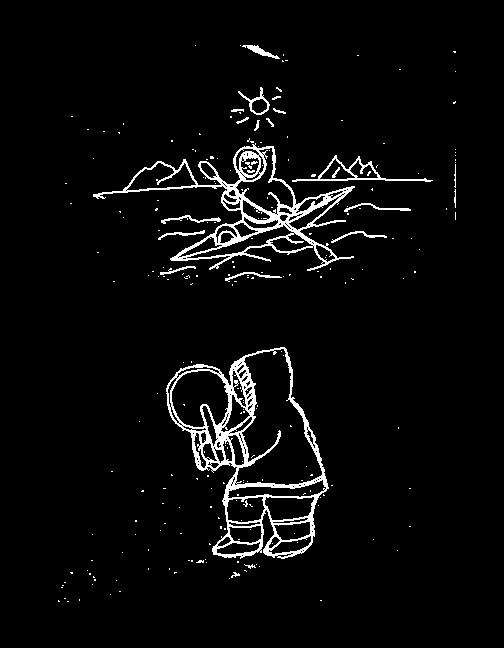

It was all kinds of stuff we used to do, them days. Seems like there was work to be done in the spring, and in the fall, in the summer, and in the winter. In the winter they would go deer hunting for weeks. You wouldn’t see them, they be gone so long travelling by dog team, and then we had all that deer meat to put away. Sometimes they’d make pants out of deerskin. A deer killed in the summertime is really pretty for making stuff out of it. The fur is right short. In the springtime there was so much to do because the capelin would be ashore and we’d be trying to dry some of that for the winter, and some for the dogs. And then we’d smoke trout and have a lot of that for the winter. And a lot of pipsis.

Whabbies: Red-throated loons. In Labrador, deer refers to caribou.

We used to do so much sealskins in the fall, make boots and stuff. We brought them to the government store, they bought everything like that to sell to other people. The store used to buy pipsis and bags of dried capelin too.

I really lived a lot just with my family. Whatever my parents done, whatever they worked at, we had to do it too, to learn things. If they’re working char, if they’re working with fish, if they’re drying stuff—we had to do it too. And we had to pick the berries, and help with the wood, paint the motorboat, and paint the flats. I loved doing that. Even when I was young in Okak Bay, I liked to be around Elders and help them. Dan Kora and his wife, Harriet, lived by us; they were Elders. Me and my friend Judy used to haul water for them and bring in their wood, and when they saw us they would say, “Our little angels is come!”

Pipsis (also called pissi, pitsik, piffi, piphi, pitsi, and other names): Dried trout or char.

My dad used to be a mailman. Dad used to travel from Nutak to Nain, pick up the mail, then go back to Nutak and down Hebron, and back again. He would have another fellow with him, Henoch Lampe. When Dad was delivering the mail, it used to be a month sometime before we’d see him. He’d go around the three places in a month. Sometimes he wouldn’t be able to go, see, when the weather was bad. He travelled only in the winter. I think he had eight dogs in his dog team. They had Kamutiks them days with bars. Now there’s no Kamutiks with bars on hardly, they just nail them up. They’d have a box on the Kamutik, but they still lashed it on. All lashed on with line, fishing line. Everybody that makes Kamutiks has a different way of making them.

Kamutik (also qamutiik): A sled for travelling or hauling wood, pulled by dogs or snowmobile.

When it was time for us to go out to Cut Throat, there was a lot to do. Mummy used to have a garden, and we’d make sure the kellup was around the edges to make the vegetables grow.

Kellup: Seaweed.

Reflections from Them Days

And then we’d have to take a motorboat-load of wood out to Cut Throat to have to burn in the summer. And then we’d come back in the summer once to check the place.

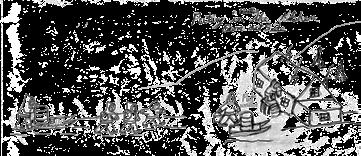

At Cut Throat Harbour every family had their own stage. It was families from around everywhere—Okak Bay, Udlik, Nutak. The Merkuratsuks had the biggest stage, and there was one big old stage that would hold salt and stuff.

There’d be a lot of schooners in Cut Throat. You’d get a lot of things brought down in the spring from the schooner people. MacMillan would travel down every summer and bring down second-hand clothes and rubbers and that.

Stage: A shoreline compound of wooden platforms, sheds, and tables where fish are processed.

MacMillan: Admiral Donald MacMillan commanded a schooner called the Bowdoin. His ship would periodically bring supplies to the North Coast of Labrador. In 1929, he donated and transported supplies used to build the Nain Boarding School.

Everybody’d be excited back them days. We’d have stuff all made up to trade with, you know. Beautiful carvings and beautiful tablecloths all worked with embroidery, all kinds of stuff. Basket work, everything. A lot of men done nice carvings, sometimes even from wood, like Kamutiks and dogs. And me and my brother Harold used to do pretty good-looking Kamutiks and dogs, just as a pastime in the evenings. The heads on the Kamutik bars had to be made really nice. We used to have a good old time out Cut Throat. Saturday night there’d always be a big dance, till twelve o’clock—had to stop because then it was Sunday. No one would even go out to haul the traps or fish on Sundays. Everything stopped on Sundays.

We used to go over to Ladybug Island, get all our bakeapples. That’s a beautiful place there, the sand. You go right ashore in the motorboat and not hit nothing, just the pretty sand, jump out. That was the time when the war was still on, around 1944. We didn’t hear much about the war them days, being where we were. One time we was berrypicking, picking blueberries and blackberries up on Cut Throat Hill, a lot of us young ones. And we seen these boats coming, strange boats like we never seen before. Every kind! And some of the kids throwed away their berries and ran, they were running down over the hill to tell our parents we think the war is coming! We thought they was war boats because we never seen those kinds of boats before—we only knowed the old schooners and freight boats, you know. What happened was that those strange boats were travelling to the radar station at Saglek, and there must have been a big sea on, so they were travelling close to shore. Gave us all some fright, we thought we were going to be blowed up!

When we’d come back in the fall after fishing all summer, we’d have to start getting ready for the winter. We’d travel around a lot in the motorboat for hunting and stuff. And in the fall when we left Cut Throat we’d always stay in Nutak for a while, us and the Onaliks, get all the bills paid up and do things out there, help to unload the boats that brought freight, help to build stuff that had to be built. We never used to be finished work till nine or ten in the night. We had a radio that worked from windchargers. Same as for the electric lights in Nutak—we didn’t need diesel for radio and lights, the windchargers did it all. We’d listen to the radio some nights. The radio was mostly made of wood, eh. That’s the same radio my parents listened to when we used to call home once a month, when we were in the boarding school in Nain.

I was in the boarding school in Nain in ’49 and ’50. There was no school there in Nutak, but they had school in Hebron.

We had to go to school because when Joey Smallwood was elected, children got what they called a family allowance. But it was only six dollars a month. If we didn’t go, our family wouldn’t get it. It wasn’t very much, but it was a help. I guess they thought it would be good for us to get some learning. I didn’t really find it too bad. Sometimes it used to get quite lonesome and stuff, but…

The two years we went to the boarding school, we went on the Winifred Lee. That’s the boat we used to go on. It would be in October. The first time I went on the boat I think I was 11. There were quite a few of us on the boat. I think there was

12 or 14 of us one fall from Nutak. That’s only the ones that didn’t have nobody to take care of them in Nain, who had to stay in the boarding school. A lot of boys and girls from the community used to go to school too, just daytime school. You knows, it was hard first going that fall, going away to boarding school. It wasn’t so bad for some of us, we were older, but the younger ones, like seven and eight years old.… Oh my, crying. Getting to Kiglapaits going to Nain, they’d still be crying. Skipper Joss Winsor was the captain and I suppose he only said it to quiet them down, I don’t know—he said he’s going to have his dinner and whoever’s left crying, he’s going to throw them overboard. Well, you should have heard them sobbing and trying not to cry.

When you get to school in Nain it was strange, you know. You had to start over.

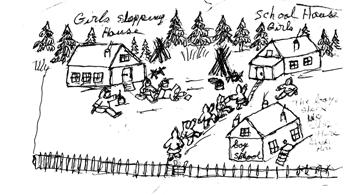

This is the school. That’s where they would teach us. That’s our schoolroom. Mrs. Peacock used to teach religion, and Katie Hettasch was the teacher for everything else, and Mrs. Ogletree was also a teacher.

Everyone had their little own wooden desks. A lot of children spent half their time in the corners with their hands behind their back. You wouldn’t have to do too much bad anyway for you to get put in the corner. Trying to whisper to one another, I suppose.

I used to like the books they had back then. We didn’t used to have Inuttitut classes then. Everyone was already talking it, just about. After I was going to school, must’ve been after, the kids wasn’t allowed to talk Inuttitut, only English. We usually spoke English and Eskimo, both of it. Auntie Katie could talk Eskimo, and Mr. Peacock could preach in Eskimo. They taught in English.

The girls sleeped in the old anatalak, what they used to call it. We used to sleep in the rooms. We had bunk beds, them old tin ones. Nothing upstairs, only what they had put up there. We used to light the fires every morning, the girls. This building, there was always something going on in there, ’cause that’s where we’d all eat. The boys used to sleep upstairs, and downstairs was the kitchen and the eating place for everybody. The boys only sleeped upstairs. They all had sealskin sleeping bags. Good job they wore pyjamas because the sleeping bag was just a skin, two skins sewed together. The fur was outside.

Inuttitut: The language of Inuit in Nunatsiavut.

When we be having meals, one of the ministers used to walk round and round the tables to make sure no one had their elbows on the tables. And sometimes, I suppose, we’d forget, and he’d grab them and bang them down on the table. Long ones, long old tables.

One morning we went over for breakfast. We always only had molasses and porridge, molasses all the time, never sugar or milk. Only Sunday morning we’d have tea and milk, and it tasted really bad because we got used to the molasses. And one morning we went over, and all the porridge were white. Oh, we were so glad! We must be going to have white porridge with milk. But when we took a spoonful....They had barrels with different things in: flour, oats, sugar, everything

else. Whoever was helping the cook—might have done it for badness, for all I know—they been put all salt in the porridge. And we had to eat it. We had to eat what we didn’t like. It was okay for us bigger ones, but the small ones was having a hard time.

That was bad enough, and then when you finish your breakfast you had to line up for cod oil. We had to line up every morning for a spoonful of cod oil. Hold our nose and down with it, and then next one, all with the same spoon. It’s a wonder I’m not healthy because of that cod oil I drinked. They say it’s healthy for you, they says. It doesn’t taste very good. Specially when they had the old buckets of frozen cod oil. In the winter it would freeze. Melt in your mouth! It wouldn’t be so bad when they come from the bottle.

Dinnertime we had dinner. Sometimes we’d have pea soup with a little chuck of beef in it, most all fat. We’d have no lunch between breakfast and dinner. They’d come in with the trays full of enamel mugs, full of cocoa and hard bread. We’d have a cake of hard bread. And the teacher, Aunt Katie, used to say, “Now yous got to chew your hard bread 60 times.” I used to be there, my hard bread gone, and I was still chewing,

make her believe I’m doing it 60 times! That was all we get then till six o’clock. We never used to have supper back then till six. Sometimes we’d only just have blackberries and a cup of molasses. All we had was hard bread, hard bread. Never must’ve had much bread. We never used to have much caribou meat or seal meat, like that. Partridges sometimes. Soup. I can’t hardly remember sometimes what we eat. Our families used to bring a lot of stuff to the school too from Nutak, them places. Like dried capelin and pipsis, good stuff like that. I don’t know where that food all went, but it didn’t go on our plates. If we did have a taste it might have been for supper. I can’t remember having vegetables. For Christmas we’d get an apple, ’cause we went to church to get it. The ministers had wonderful gardens, real good. They were for their own use. Auntie Katie and all them didn’t used to eat in the same room as we eat. They eat somewhere else.

Every Sunday we’d have to go to church twice. Nine o’clock in the morning, four in the evening. And then the girls would line up on the left side, and the boys would all line up on the right side. And children wouldn’t be able to walk in till everybody else was in church. If there was a funeral or anything at all going ahead, we always had to go. The service was in Inuttitut and English—sometimes they’d have it in English, a bit of it, you know. That’s how they always used to have service. And long ago they even used to have service Saturday evenings at seven. We had to go. The bell was up in the tower. Kiggak, church Elders, were in charge of ringing the bell. There was two ministers down there, Mr. Peacock and Mr. Grubb. Each Christmastime, every service, you’d have to

Reflections from Them Days

be there. We put on a play one time, the only Christmas play ever I was in, while I was in Nain school for one Christmas. I was Old Good King Wenceslas!

We wasn’t allowed outside of the fence, see, all the week. We wasn’t allowed to go in the village at all. We wouldn’t never go into the community. We could have one hour, Sunday after dinner, and go and visit somewhere with a friend. I used to always go to Mr. Martin’s, Sue Harris’s parents. Some children was going to only day school, and they’d be out in the community, see, they were okay. But we wasn’t allowed to leave the yard.

Only if some people do something wrong, they walk down to the Mission House and get the cat-o’-nine tails, or something. Some didn’t. I got in trouble once. I washed the

lamps and put oil in them, and when I was going back out with the lamps the boys came running in with wood and knocked one of the globes off the lamp. And I had to go down holding on to the lamp, all the way down to Mr. Peacock, the minister. But I never got pounded. It wasn’t my fault, and the boys didn’t know, I suppose, that I was right there. Oh, strict rules. We couldn’t even.…Every school morning, we had to have religion, back them days. Anybody didn’t have a good voice had to sit down. And my brother Harold had to sit down all the time.

We’d get to go to school in October. That’s when they’d take us berrypicking up through the woods there, up on the side of Nain. We went on Sundays sometimes, Sunday after dinner, before church-time. All the girls and boys go berrypicking. We had just them old steel buckets. There was no plastic buckets back them days, just steel ones. We never used to see any black bears them days; they were too wild. Now they wants to be amongst the people instead of staying in the firs.

We’d have to fill up a barrel with blackberries. We didn’t used to put redberries in the barrel, though, just the black ones. The barrel was the kind with the hoops around. Little half barrel we used to fill up, little tiny one about that high, half barrel. We had different kinds of barrels them days: the big

Reflections from Them Days

one was called a puncheon, then a tierce, then the barrel, then the half barrel.

The barrel of blackberries went in the cellar. They had a place under one of the rooms, to go right down in the frost. It would keep stuff from spoiling. Sometimes we’d have blackberries for supper. We didn’t used to get too much, you know. One half barrel for all the kids.

Katie Hettasch could do a lot of beautiful drawings. We used to have to do a lot of embroidery, with that kind of work. Only it was a different stitch to what I uses now. You used to have to work it all around with black thread first and then fill it in. She made us work a skirt right around once. It was broad

cause she had it full of pleats at the waist. We must’ve had about 150 inukuluks, I guess—that’s true, right around. She had this for a gift for the minister’s wife, Mrs. Peacock. I was 11, I think.

We had to do a lot of knitting too. The sweater I knitted was almost like if someone came out of jail, striped, eh. I knitted him so big he fitted the biggest boy in school! We used to do that every Wednesday, knit.

The boys would haul water on Saturdays. They’d fill a 45-gallon drum. They’d have a different lot of boys each Saturday to haul the water. About three or four small ones, but you’d always have one older boy with them there. They used to go up to Nain Brook. The small boys hauled the barrel on a sled. And the older boy do nothing, only just make sure they’re pulling the Kamutik. He’d be holding it in back and making sure it’s not slopping too much. The lines in front, that’s where they haul it. With the bucket they tips the water out of the brook, pull it up, and fill the drum. And the little boys used to wear skin trousers in the daytime. Good job they did,

because the older fellow used to pound the little ones with a bough when they’d get stuck.

On the outside of the boys’ boarding house, where it was also the kitchen downstairs, they’d go up the ladder, drip out the water and pour it into a pipe in there, and then it will go in another drum in the kitchen. In the summertime, they gets water from the well. There was no water and sewer back then. A lot of little boys though, eh. On Saturday one bunch, and then next Saturday another bunch.

Same way with wood. We had to do all that on Saturdays, lugging the wood. Some fellow from the community used to saw it up with the bucksaw—no chainsaw them days. When it wasn’t Saturday they’d ask someone else to haul the water. There were workers there too, see. The boys were seven and eight, like that. Brother Harold used to be one of them.

The girls had to scrub all the floors, porches and stuff, bathroom places, what was froze with ice. The schoolhouse porch used to be full of wood. When we were going to scrub up the porch, we had to move all the wood outdoors again, and then scrub the porch and put all the wood back in.

We had to work hard, I tell you. There’s things we had to do I wouldn’t even say. We had to clean up so much, do so much work, eh. We had to work hard, but I didn’t really find it too bad.

We’d go sliding some afternoons, some Saturdays, have a good time sliding. We used to slide a lot on Nain Point there where the planes land. You got to climb a lot to go up, but coming down be good fun. Some slide on sealskins, and some slide

Reflections from Them Days

on old Kamutiks. We used to make sleighs out of some of the bigger barrels. They’re in pieces, see, and then they’d nail three together and put water on it in the nighttime and it would freeze. You go down the hill fast, I tell you. Good for sliding on. Coming towards spring it was real good for sliding. The snow was stiffer for walking up and down. Sliding on the sealskins made them pretty. When you’re sliding it makes the fur right nice. Turn them around and you stop short, eh. That’s your brakes, the fur. Auntie Katie used to get a lot of sealskin from the communities, and she’d have us making them softer. We used to work all the evenings sometimes, softening them up after we’d been sliding on them. Put strings through the holes where they’d put them in the frame and then we’d stamp on them. They cuts a hole around the sealskin when they’re going to put them in the frame, but then when you’re going to soften them they put a bigger string around and draw it tight and then stamp on them, keep treading on them till they get soft. Exercise, I tell you. I think my bones were wore out long ago.

Sometimes we’d skip rope. Two would hold on the rope and one would skip in the middle. Sometimes you’d fall down. We used to sing songs sometimes. The seesaw was just a big junk of wood with a board put on it. You go up and down—one go up, one come down. Oh yeah, we’d take turns—fight over it too! They used to skate too. Mrs. Ogletree’s husband was a good old skier and skater, and he used to be trying to learn them how to skate. I put on my pair of skates and I went flat right away!

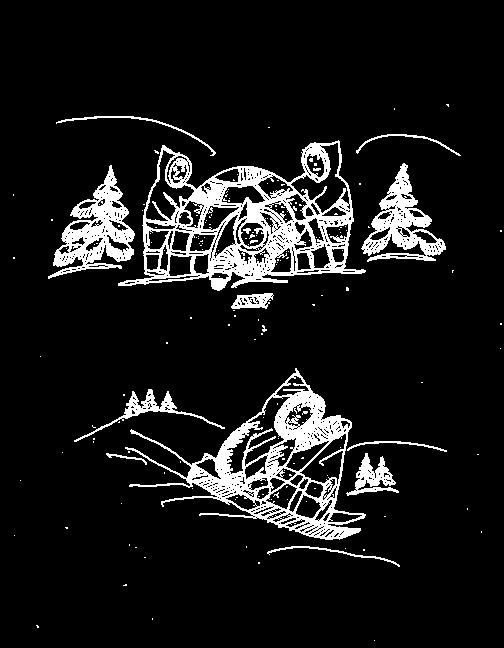

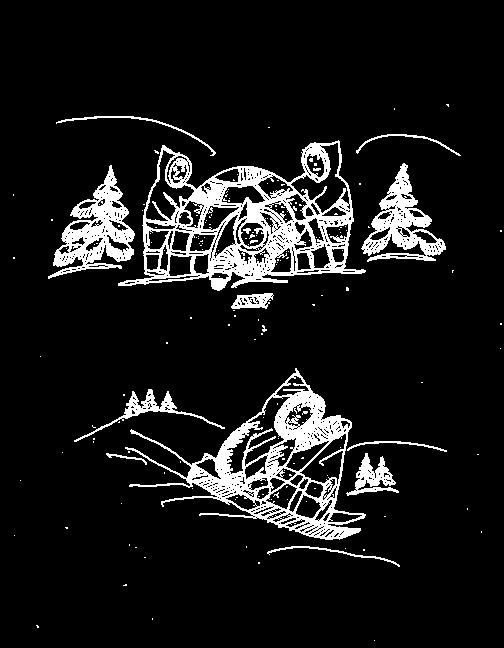

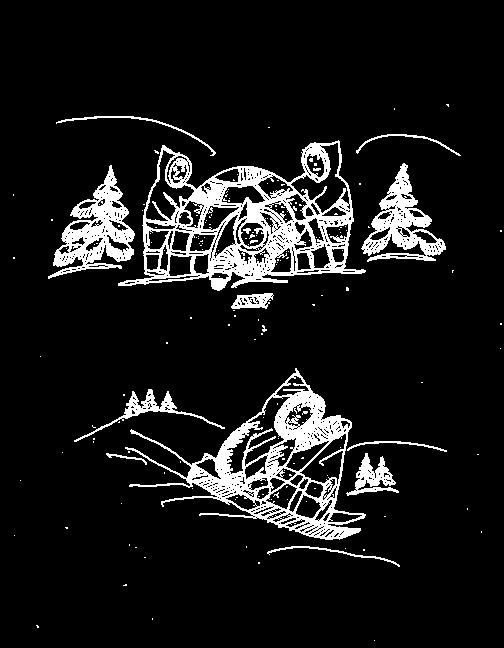

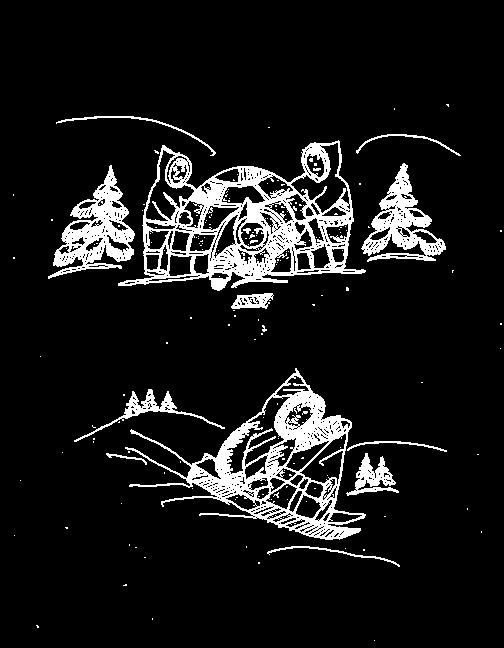

We’d make a snowman. Where it packs better in places, the snow is better for making igloos. We even had to make igloos one time at the boarding school. Someone was coming in, a visitor, and I had to be out sitting by the igloo trying to bottom a boot—and that perishing cold! Must have been for whoever they were to see us girls sewing outside the igloo. I suppose they couldn’t do it in the spring. It would melt on us!

Every Saturday we’d have to take someone small and go for walks, and I always used to take Abe Flowers. We used to have to stay outside from one to four. One time we runned away. It was in the winter. Must’ve been January, I guess, February or something. We went right over to Kauk. Mr. and Mrs. White had a little store over there, see? I don’t know how we thought we was going to get anything from his store with no money. We had no money. We went out walking, we keeped on walking, we went right up over that hill and almost crossed the pond when they found us. We got grounded, I tell you. The men went looking for us on dog team. But we didn’t separate from another. We just kept on going.

We used to walk a long ways them days. That stick is still in the rock on top of Nain Hill, up from the brook. I tied my yellow ribbon on there. I don’t know if it’s still on there or not. We climbed right to the top.

Every month, once a month, we’d walk down to the Mission House. They had some kind of an old radio. The radio was in the living room, downstairs. Our parents down Nutak and them places knew when we were going to be on—would be like seven o’clock in the evening, I think, on some channel. We’d talk home. We wouldn’t hear them, but they’d hear us, and we’d tell them what we wanted and all that. In between the talking, Sid Dicker used to sing a song. That’s the one who wrote “Labradorimiut” when he grew up, that’s a popular song now, all the bands today sing it. Some of the kids be crying on the radio, some of them be saying, “I wants another pair of boots, mine is holey.” Mary Metcalfe, she told her parents, “I want some more candies ’cause somebody stole mine!” We

Reflections from Them Days

didn’t care what we said! Our parents would send down what we needed. Even though we couldn’t hear our parents, it made us feel happy to be talking to them, and the singing was real good.

I only went home on dog team one year—1949, from Nain to Nutak, on dog team. That’s the only time I ever stayed in an igloo. We left around the 20th of April or something like that. It’d be too bad, see, if they waited till May, you know, the rivers be breaking out.

Mum and Dad and Henoch came to get us on dog team. I didn’t even know my parents were coming to get us. They had no way of communication them days. I can always remember, ’twas a Sunday evening. We were all over in the old anatalak where we used to sleep, and the boys from the village start knocking on the window and want to speak to me. And I said no, I’m not opening the window. And then they said okay, I’m not going to tell you the good news. So I had to

open it enough for David Harris, I think it was. And he said your mummy and them is come on dog team. I thought he was tricking me, you know. But it was true. We left the next day after they got everything ready for the trip.

It was two days travelling to Nutak. And then another day to go in to Okak Bay. Going from Nain to Nutak we had to work so hard. I don’t know if I looked around very much!

’Cause when we got on up, the brook was breaking out and we had to go up over the side of the hill and hoist the Kamutik down over. ’Twas awful. But there was a lot more people travelling. That was the year the Innu people moved from Davis Inlet north. So by the time we got to Udlik, all the Innu people were there too, a whole whack of us.

We stayed in a little small wooded place there in an igloo, just before we went up Kiglapaits. I been try to make igloos, me and Harold, but we never could get the top right. It’s the way you cut it—it turns, eh. And all we had inside the igloo was what they call a blow lamp. You puts the coal oil in it and then you pump it and the flame will come out, and you have a cup of tea, and then the igloo will get iced up inside. Oh my, I didn’t really like it at all. I think I was claustrophobic then, you know. I feel like I was going to smother when they put the door up. But they leaves a little hole, you know. The heat goes up through all right. It was all five of us in the igloo. It was like sardines lied down in there! We always had deerskins on the Kamutiks to sit on, to keep you warm, and

we brought them in the igloo. No blankets. They used to make igloos a lot, my brothers. I never even wanted to sleep in one, I don’t think. Some likes it. A lot of people don’t like it.

But the next year then when we had to go back, we were still in class in the morning and someone came in, and he said yous got to get ready, the DC-3 or something or other that was

flying to Saglek was going to take all the Nutak children home. Oh, we landed on some rough ice, I tell you, in Nutak. Bumpy, oh my! Just like that, just got us ready and go. We didn’t have much to take, I tell you. We all sat on each side of the plane, looking at one another. First time ever on an airplane! We didn’t seem to be afraid; we didn’t even seem to care if they took us to Saglek. We didn’t seem to care. When we landed there in Nutak, no one knew. Someone came out to the plane when she landed and took us ashore. And then someone had to take us by dog team up in the bay. Our parents didn’t know we were handy, me and my brother Harold. They were used to Kamutik and dogs coming round the point, going up the bay, sometimes they go deer hunting through there, see. But they never knew we were handy. The first thing I did when I got home was I went partridge hunting. I loved going partridge hunting. I used to climb that hill there. There wasn’t so much trees there then.

Helping Dad with the wood, we loved going in the woods. Helping them make nets for the spring. I got back to doing all the things I loved to do.

My memories of home in Okak Bay is a lot, really. How we used to do things, and how we always got along. Seems like we always managed to get along whatever we did.

Nellie (Andersen) Winters is an Elder from Okak Bay living in Makkovik, Nunatsiavut (Labrador). She was raised in Okak Bay, on the north coast of Labrador. Her family was relocated to Makkovik in 1956 when services to the area were cut off by the provincial government. Nellie Winters is a respected artist whose work is commissioned and exhibited by galleries, museums, and private collections both in Canada and internationally. Her artistic work includes sealskin boots, caribou tufting, embroidery, coats, caps, dresses, beading, jewellery, carvings, grasswork, wall hangings, dolls, purses, paintings, and even a sealskin lamp. In 1976, Nellie Winters was personally invited to demonstrate her artistic work at the Montreal Olympics. For many years, Nellie Winters has contributed to artistic life in Nunatsiavut as a skills instructor, as an original board member of the Makkovik Craft Council, and as an active member of the Makkovik Ladies’ Sewing Circle. In addition to her artistic contributions, Nellie Winters is widely respected as an Elder, knowledge holder, interpreter, author, and educator.

Erica Oberndorfer was born in Hudson, Quebec, to Carol (McKechnie) and Dieter Oberndorfer, and has one younger brother, Derek. She studied at McMaster University (Hons. BA & Sc), Saint Mary’s University (MSc), Carleton University (PhD), and completed a post-doctoral fellowship with the Labrador Institute. She is a cultural botanist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Goose Bay. Since 2012, Erica has been working with plant mentors in Makkovik, focusing on cultural plant knowledge and the plant ecology of cultural places. Erica lives in Goose Bay with her husband, Paul MacDonald.

When Nellie Winters was 11 years old, she was sent to attend the Nain Boarding School, a residential school 400 kilometres from her home. In this memoir, she recalls life before residential school, her experiences at the school, and what it was like to come home.

Accompanied by the author’s original illustrations, this moving, often funny memoir sheds light on the experiences of Inuit residential school survivors in Labrador.

Qinuisaarniq (“resiliency”) is a program created to educate Nunavummiut and all Canadians about the history and impacts of residential schools, policies of assimilation, and other colonial acts that affected the Canadian Arctic.

ISBN 978-1-77450-207-5 $12.95

51295

9 781774 502075