4 minute read

Dedication

I dedicate this book to everyone who comes and asks me things and trusts me to tell stories. It takes a while for things to come back in my head, but it’s good memories when I get to talk about it. Thank you all for reading my stories.

Foreword

This book is about the personal experiences of Elder Nellie Winters at residential school in Nain, Labrador. Alongside these stories are memories of her childhood home of Okak Bay, on the north coast of Labrador, in what is today the selfgoverning Inuit region of Nunatsiavut.

Aunt Nellie was born in Okak Bay in 1938. Her parents were Hans and Jane Andersen, and they had eight children: Andrew, Samson, Jessie, Bonnie, Nellie, Harold, and sisters Maud and Mildred, who passed away before Aunt Nellie was born. Her family’s winter home was at Okak Bay. Each summer

Aunt Nellie and her family would move to Cut Throat Island, about 30 kilometres east of Okak Bay, to fish. Many other families from the town of Nutak joined them there for the

Reflections from Them Days

fishing season, before everyone returned to their own winter homes in the fall.

As Aunt Nellie describes in her memoir, children were traditionally educated by their families by living and working alongside them, actively developing knowledge and expertise. There were, however, accumulating pressures for families to send their children to residential schools. On the north coast of Labrador, Moravian missionaries wielded strong authority and influence through the church, and they operated two residential schools: one at Nain, and one at Makkovik. The provincial government increasingly viewed traditional harvesting economies as stuck in the past and pushed programs and services—including education—toward developing a centralized wage economy.

When the Dominion of Newfoundland (including Labrador) joined Confederation in 1949, the family allowance became available to residents of Canada’s newest province. Though the family allowance made a significant difference to the well-being of the whole family in regions where people were paid little, and often unfairly, for their work, it was also a tool to ensure full-time school attendance, because otherwise it would be withheld. Many families also genuinely hoped that an education at residential schools would benefit their children in future years.

There were no schools in Okak Bay, or Nutak, or in any of the small bays or islands where families lived all

Winters

along the Labrador coast. The closest residential school was the Nain Boarding School 400 kilometres to the south, run by Moravian missionaries in the community of Nain (in Labrador, residential schools are often referred to as “boarding schools”). In 1949, when she was 11 years old, Aunt Nellie left her home of Okak Bay to attend the Nain Boarding School. It was her first time away from her family, her neighbours, and her home.

Aunt Nellie attended the Nain Boarding School until the spring of 1951. After her time at residential school, she went home to live with her family in Okak Bay. She lived there until 1956, when the provincial government ordered the closure of the communities of Okak Bay and Nutak. All residents were forcibly relocated to communities farther south, and the same happened again to residents of Hebron in 1959. Aunt Nellie and her family were relocated to Makkovik, where they had relatives. She has lived in Makkovik ever since.

I first met Aunt Nellie in July 2012, when I visited Makkovik to begin work on my PhD. As well as being extremely knowledgeable about plants—my area of interest— Aunt Nellie is a highly respected artist. Aunt Nellie always has a pen and paper handy, and when we visit she often draws a picture as a way of explaining a story or idea in more detail.

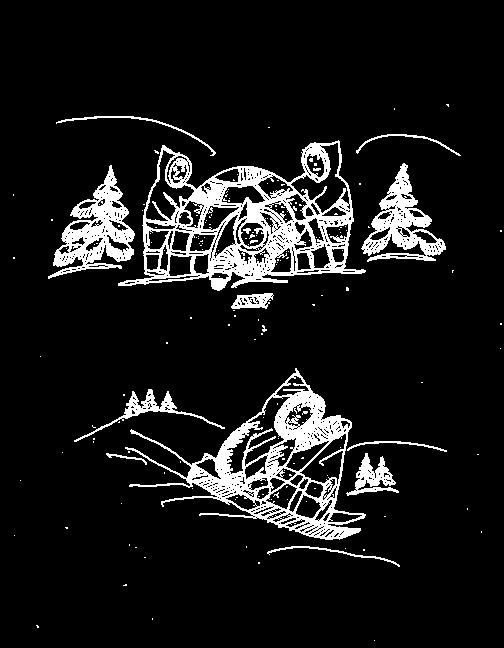

One day as we sat together, she opened her everpresent sewing box and pulled out a stack of papers filled with inukuluk drawings. Inukuluks (inukuluit), or “little people”

Reflections from Them Days in Inuttitut, are designs that are frequently embroidered on tablecloths and clothing, featuring everyday scenes such as people berrypicking or playing games. The scenes depicted in these drawings were different. Using inukuluks, Aunt Nellie had illustrated memories from her days at the boarding school in Nain.

That day, and over the following year, Aunt Nellie told the stories that lived in each of these drawings. We audiorecorded these stories, and I transcribed her words when I was back home in Goose Bay. During the next visit, we would go over the printed transcripts of the previous visit, and new details would emerge, as well as new stories. Aunt Nellie made more drawings and told more stories, I made more notes, and so we continued. And that is how this book came about.

I asked Aunt Nellie why she began drawing scenes from her time at boarding school, and why it was important to her to share her illustrations and stories with others. She replied:

I have eleven children—Pearl, Bella, Dinah, Sonny Boy, Polly, Dorothy, Doreen, Irene, Blanche, Randy, and Harold—fifty-six grandchildren and greatgrandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren. It’s good for children to learn the stories from long ago, how we lived back them days, when we had no TV, no phones, nothing. Back them days, work and learning was our pastime. In boarding school, it wasn’t always good, but

Nellie Winters

whatever we went through we learned a lot. Others had it worse than us. If I don’t share my memories, my own children won’t know the stories. This book will keep it in their memories too. Even for people who don’t know me, I hope my story is interesting to them. It’s like reading any other books about people in other places. I really get interested, even if I don’t know who they were or where they were. If people can learn anything from my stories, it’s that we’re put on Earth to do things, and to make the Earth more wonderful. We’re meant to help others, especially Elders, and help others to do things.

Aunt Nellie is the best kind of storyteller. In one sentence she makes you laugh, and in the very next sentence she makes you cry. It has taken a deep well of courage to relive some of these memories and to speak them aloud. That Aunt Nellie still finds a way to share these memories with humour and love says everything about her mighty spirit.

With love to Aunt Nellie for this gift to all readers,

Erica Oberndorfer Goose Bay, Labrador