futurebuilding

futurebuilding

Minister’s address | The Hon. Gabrielle Williams

Demographer address | Infrastructure for tomorrow – planning for Australia’s demographic shift, Simon Kuestenmacher, The Demographics Group

Editor: Kirsty Timsans

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

E: contact@infrastructure.org.au

Future Building is published by: Executive Media Pty Ltd

ABN 30 007 224 204

PO Box 256

North Melbourne VIC 3051

Tel: +613 9274 4200

E: media@executivemedia.com.au

W: www.executivemedia.com.au

Advertising: Peter Anderson

E: peter.anderson@executivemedia.com.au

Tel: +613 9274 4200

Business Development Manager: David Haratsis

E: david.haratsis@executivemedia.com.au

Tel: +613 9274 4214

The images contained herein are courtesy of Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, Shutterstock, and iStock.com

Panel discussion | 20 years of reform

Keynote interview | Shemara Wikramanayake, Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer, Macquarie Group

Panel discussion | Delivering more with private investment in public infrastructure

Panel discussion | Energy: from ideas to electrons

Keynote interview | Greg Boorer, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, CDC

DISCLAIMER:

The editor, publisher, printer and their staff and agents are not responsible for the accuracy or correctness of the text of contributions contained in this publication, or for the consequences of any use made of the products and information referred to in this publication. The editor, publisher, printer and their staff and agents expressly disclaim all liability of whatsoever nature for any consequences arising from any errors or omissions contained within this publication, whether caused to a purchaser of this publication or otherwise. The views expressed in the articles and other material published herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor and publisher or their staff or agents. The responsibility for the accuracy of information is that of the individual contributors, and neither the publisher nor editors can accept responsibility for the accuracy of information that is supplied by others. It is impossible for the publisher and editors to ensure that the advertisements and other material herein comply with the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Readers should make their own inquiries in making any decisions, and, where necessary, seek professional advice.

© 2025 Executive Media Pty Ltd. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Chairman’s foreword

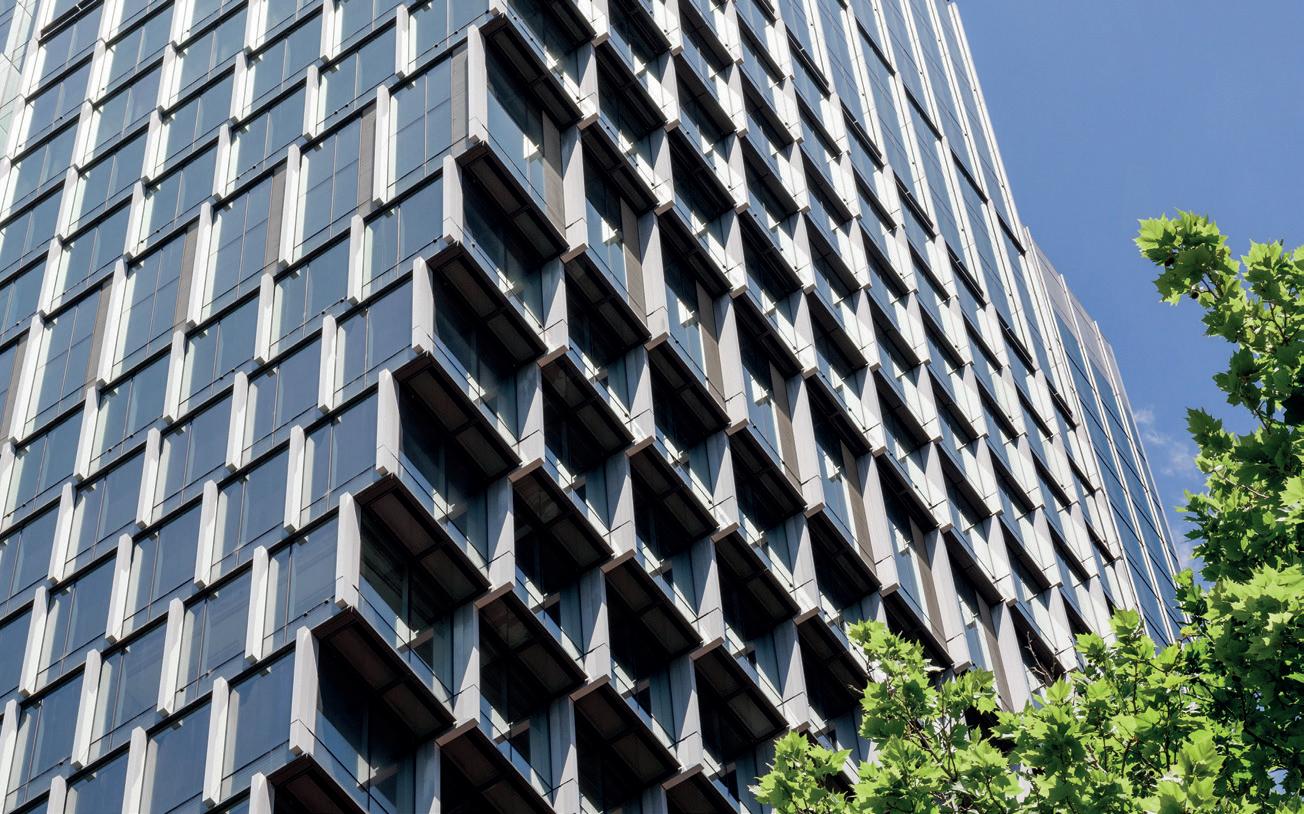

In September, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia’s flagship conference, Partnerships, returned to Melbourne.

As the premier infrastructure event in the nation, Partnerships 2025 once again brought together a host of infrastructure and business leaders to directly engage on the critical issues shaping our sector now and into the future.

I am delighted to present this year’s edition of Future Building, which captures these conversations for your reflection and insight.

Partnerships 2025 carried particular significance, coinciding with the broader milestone of 20 years since the establishment of Infrastructure Partnerships Australia. It marked two decades of advancing our mission – to shape public debate, connect the sector and drive reform towards good infrastructure policy. This mission underpins the purpose of Partnerships each year.

Opening the conference, the Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP, Victorian Minister for Transport Infrastructure, and Minister for Public and Active Transport, outlined a suite of major projects defining Victoria’s infrastructure program. She reaffirmed the importance of a strategic, long-term approach to meeting the needs of the State’s growing population.

Building on this theme, demographer Simon Kuestenmacher painted a compelling picture of Australia’s population trajectory over the next decade. He noted that continued growth will place increasing pressure on housing, transport networks and essential services, underscoring the need for coordinated, and enduring, infrastructure planning.

The day’s discussions were further enriched by insights from respected leaders across the sector. Among these was Macquarie Group Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer Shemara Wikramanayake, who explored the macro-economic forces shaping markets at home and abroad.

This year’s Partnerships also brought together senior leaders for a series of panel discussions exploring how organisations are addressing the sector’s most pressing challenges – from bridging the perception gap around private sector participation in public infrastructure, to accelerating Australia’s energy transition.

In recognition of our milestone year, a special panel reflected on the last two decades of policy reform, featuring some of the key figures who have been influential in driving this reform, as well as shaping the Infrastructure Partnerships Australia story.

Amid growing demand for digital infrastructure, Partnerships closed the event with a dedicated session on data centres, featuring Founder and Chief Executive Officer of CDC Greg Boorer. This discussion highlighted the pivotal role of data centres as critical infrastructure underpinning national security and economic prosperity, and reaffirmed Australia’s emerging potential as an artificial intelligence hub.

As we look to the year ahead, may these reflections spark new ideas, deepen understanding of the challenges before us, and inspire continued commitment to strengthening the future of our industry.

Sir Rod Eddington AO Chairman Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Transforming waste management for a sustainable future

Cleanaway is Australia’s leading waste management and resource recovery company, but to label it solely as a garbage collection company is rubbish.

Far from pivoting away from waste, Cleanaway’s transformation

aims to enhance efficiency in the way domestic and commercial waste is viewed. To Cleanaway, waste is a resource to be managed and benefited from, and through the adoption of this mindset and investment in cutting-edge technology

and infrastructure, it is transforming a sector that touches every Australian.

With a fleet of approximately 5,900 trucks, Cleanaway serves around 130 local councils, and more than 150,000 industrial and business customers around Australia.

‘A modern economy needs fit-for-purpose waste management. This shift is about building stronger and resilient infrastructure that delivers sustainable, low-carbon solutions for our customers, all while maintaining top-notch service and competitive prices,’ says Preet Brar, Executive General Manager – Energy From Waste, Cleanaway.

A commitment to decarbonisation is at the heart of Cleanaway’s mission. The company has set ambitious internal emissions targets, aiming for a 43 per cent reduction in carbon dioxide emissions and a 34 per cent reduction in methane emissions by 2030. These targets align with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 1.5 degrees Celsius scenario and the Global Methane Pledge.

‘We’re focused on reducing our own emissions, but also on decarbonising the waste industry as a whole. We are proud to be the only waste management company in Australia with such ambitious emissions targets,’ says Brar.

Changing perceptions of waste are behind Cleanaway’s refocused strategy. No longer viewed as having no value, waste is now recognised as a valuable resource that can be recovered, reused or recycled.

Consequently, Cleanaway is reimagining the waste hierarchy, which includes domestic recycling initiatives such as Circular Plastics Australia1 and partnerships for soft plastics recycling. The waste leader is also spearheading international recycling efforts that send materials like aluminium cans to overseas smelters for repurposing. Downcycling to transform waste into products like park benches and clothing is also a priority.

A critical component of Cleanaway’s strategy is its investment in energy from waste (EfW) facilities that convert non-recyclable waste into clean energy. Governments across Australia have adopted landfill diversion targets in an attempt to

dramatically reduce the amount of waste being landfilled – reducing greenhouse gases and protecting existing airspace. One EfW facility with a feedstock of 760,000 tonnes per annum has the capacity to power up to 140,000 homes and provide steam for heating 31,000 homes, or the equivalent industrial applications.

Valuable materials such as metals and aggregates can be recovered from the ash produced during combustion, further reducing the need for virgin materials and preventing waste from ending up in landfill. Additionally, EfW facilities require less land than traditional landfills, with a footprint of less than 10 hectares compared to the hundreds of hectares needed for landfill operations.

‘EfW facilities, as an example, reduce greenhouse gas emissions by diverting waste from landfill. The energy generated from these facilities offers a low-carbon-intensity electricity source, contributing to carbon savings over the asset’s life span,’ says Brar.

‘Closing the loop on waste creates cost and environmental efficiency. It is a win-win and there are myriad opportunities across the waste life cycle where we can do this.’

Cleanaway also plans to develop circular energy recovery precincts, where EfW will act as a catalyst for investment, providing opportunities for industries to co-locate, creating an ecosystem of symbiotic industries supporting local manufacturing, innovation and long-term job creation. The partners involved in the precinct will use the electricity, heat, steam and cooling produced by EfW facilities onsite and for neighbouring industries.

‘These precincts will be a place where solutions are provided for the most complex challenges, including the energy transition, onshore manufacturing, food and water security, recycling, circularity and waste management,’ says Brar.

An example is the Melbourne Energy and Resource Centre (MERC), which is being designed to

process residual waste that would otherwise be sent to landfill. In August 2025, Cleanaway received a cap licence from Recycling Victoria, allowing the MERC to process up to 760,000 tonnes of waste annually.

‘This enhances the project’s economic and operational viability, supporting environmental benefits, lower waste management costs and improved energy recovery at scale,’ says Brar.

The facility will process 760,000 tonnes of waste each year, diverting 13 per cent of Victoria’s waste from landfill. It is expected to produce enough energy to power 140,000 homes and businesses, while recovering 200,000 tonnes of ash and metal resources that would otherwise be discarded.

These projects also create jobs and broader economic uplift for local communities. The MERC, for example, is expected to create around 800 jobs during construction and employ up to 50 people during regular operations, including expert engineering roles, helping support the Victorian economy.

In addition to the MERC, Cleanaway also has plans to build the Bromelton Energy and Resource Centre in Queensland. Just like MERC, this facility will use internationally proven technology to convert waste into energy, similar to successful operations in cities across Europe, North America and Japan. Community consultation is underway.

‘Through these initiatives, we are transforming our business model and leading the way in sustainable waste management,’ says Brar. ‘Our focus on circularity, integrated infrastructure and decarbonisation sets a new standard for our industry, demonstrating that waste is a valuable resource.’ ♦

End note

1 Circular Plastics Australia (PET) is a joint venture between Cleanaway, Pact Group, Asahi Beverages and Coca Cola Europacific. Circular Plastics Australia (PE) is a joint venture between Cleanaway and Pact Group Home | Circular Plastics Australia | Remade in Australia

Welcome address Adrian Dwyer, Chief Executive Officer, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Good morning and welcome to Partnerships 2025, returning this year to Melbourne. I’m delighted you could join us for one of Infrastructure Partnerships Australia’s signature events.

Today, we bring together a host of senior business and public sector leaders to directly engage on the critical questions our sector must answer, and to debate the challenges and opportunities before us.

Each year, Partnerships offers a chance to reflect on where we have been, and to look ahead to where we

are going. For me and many others in this room, this pause for reflection feels especially significant as it coincides with the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of Infrastructure Partnerships Australia.

Our organisation was founded on the belief that the cause for good infrastructure could be advanced by stronger engagement between the public and private sectors.

In the last two decades, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia has transformed from a startup operation into the

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia Chief Executive Officer Adrian Dwyer welcomes attendees to Partnerships 2025

national voice for infrastructure policy and dialogue. And this would not have been possible without the guidance and mentorship of our early supporters.

I would like to acknowledge the presence of several of these individuals in the room – our Chairman, Sir Rod Eddington AO, and the broader Advisory Board; previous Chairs the Hon. Mark Birrell AM and Adrian Kloeden; and their fellow Patron Tony Shepherd AO – all of whom have played a pivotal role in our story.

I’d also like to welcome, from our host state, the Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP, Minister for Transport Infrastructure, and Minister for Public and Active Transport, who will open today’s proceedings. Many of our longstanding supporters are also among today’s event sponsors.

Macquarie Capital, which has sponsored Partnerships from its inception, deserves particular recognition as our Platinum Sponsor once again. Macquarie’s contributions over the years have helped this event go from strength to strength, and we are proud that this enduring partnership continues to deliver for the sector.

Macquarie Capital is joined by our Gold Sponsors, Transurban, Schneider Electric and Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer – all of which have generously supported this event and our broader program of work throughout the years.

And finally, thank you to our Silver Sponsors – The APP Group, the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance, Mizuho | Greenhill & Co., and Transgrid.

In many ways, the Infrastructure Partnerships Australia story reflects the broader reform journey of the sector itself. Both can be captured in this aphorism: much done, much to do. As a sector, we can stand tall on the work of recent years – from delivering global-scale transport projects and

unlocking innovative financing, to cultivating institutional strength and maturity, and leading the decarbonisation effort. But we must also acknowledge that we stand in the midst of a productivity challenge – one that has been steadily, and insidiously, tightening its grip since the mid 2000s.

At its core, this flagging productivity is driven by fragmented regulation, sticky approval processes, high input costs, labour skills gaps, unnecessary government intervention into otherwise functioning markets, and shifting demographics.

Spurred by a strong majority at the May Election, this has prompted the Federal Government to put productivity back onto the agenda, as reflected in August’s Economic Reform Roundtable. Following more than a decade of advocacy, we are finally seeing the green shoots of reform on an issue close to our hearts, with governments agreeing to work together to implement a road user charge.

Amid the productivity challenge, the sector finds itself at a crossroads. As the mega-transport pipeline recedes, the national pipeline enters a new era: one that is defined by energy and, increasingly, by digitalisation, fuelled by the rise of artificial intelligence and the data centres that power it.

Yet, this is a very different world from the one that delivered the transport boom. If anything, today’s challenges are even more formidable – shaped by increasing uncertainty at both economic and geopolitical levels.

And so, today’s agenda is designed to bring focus to that uncertainty, and to chart a pathway forward. Each year, we endeavour to set the bar high by bringing our members the discussions and insights they can’t get anywhere else. And today is no different.

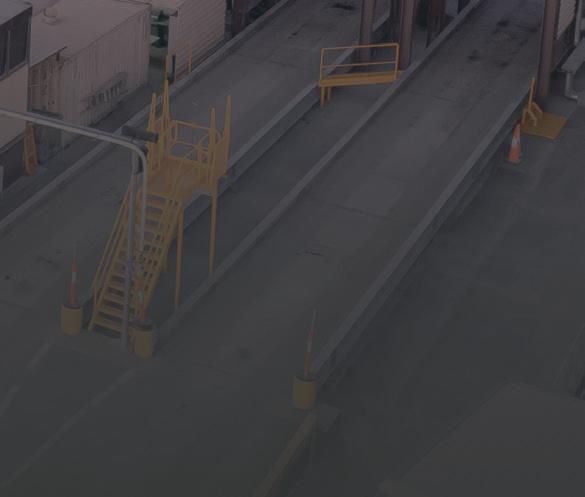

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia’s Partnerships 2025 conference

Next generation of sound protection

Traditional, high-rise noise barriers along train tracks are often an eyesore, obstructing views for both residents and passengers. The most effective way to reduce noise is to address it at its source, as close to the tracks as possible. STRAILastic has developed an optimal solution with its product line, offering a variety of sound protection systems that maintain clear views.

The STRAILastic systems are designed to be installed as close to the rails and the track clearance gauge as possible. By tackling noise at its point of origin, these systems can be much lower in height. The smallest sound protection wall is just 55 centimetres high, which allows it to be placed very close to the source of the noise.

Variants with heights of 73 centimetres and 125 centimetres have been developed and are in production. This low-profile design ensures that the noise barriers are far less visible than conventional ones, blending seamlessly into the landscape. This also allows passengers to enjoy the view from the train despite the presence of the sound protection.

In addition to their unique shape, the high effectiveness of these products comes from their material: high-quality, fibre-reinforced rubber with a highly absorbent acoustic surface. The systems are also extremely durable, shatterproof, and resistant to UV rays and ozone. They can easily withstand the pressure

and suction forces created by passing trains, which prevents material fatigue and ensures a long product life span.

For exposed sections of track like bridges or retaining walls, STRAILastic offers special sound protection elements. These elements, called infill panels, can be mounted directly onto existing, structurally suitable railings. This eliminates the need for an additional support structure and its corresponding building permit. These elements effectively shield the tracks from the surrounding area without being obtrusive. The infill panels are installed vertically and can be customised with printed panels to mimic, for example, the appearance of a hedge or a stone wall. ♦

STRAILastic mini sound protection wall

Ecological awareness has grown strongly in recent years. Green tracks contribute to the reduction of fine dust pollution and to improvement of the microclimate in inner-city areas.

STRAILastic protects the superstructure from stray current. In addition, noise emissions are considerably minimised.

¬ insulates stray current

¬ quick and easy installation possible, can be installed during on-going operation

¬ available for all superstructure types by encapsulating the rail, the primary airborne noise is considerably

¬ reduced compared to an open construction method

Fight sound before it is generated dampens the vibration using its weight

Camden Council’s strategic push for investment

As one of Australia’s fastest-growing local government areas, Camden in South Western Sydney is at a crossroads. Its population is projected to surge by 81 per cent to over 257,000 by 2046 – a growth rate that demands immediate action to ensure a liveable, connected, and sustainable future.

With the 2027 state elections approaching, Camden Council has ramped up advocacy through its campaign, ‘The Time Is Now’. The program outlines urgent calls to action across public transport, roads, education and health care – areas critical to Camden’s prosperity.

Transport remains a top priority. Council is pushing for the Sydney Metro Southern Extension (Macarthur Metro) – linking Campbelltown, Oran Park, Narellan and Bradfield – alongside the South West Rail Link Extension from Leppington to Bradfield, connecting directly to Western Sydney International Airport. Following advocacy ahead of the 2025 Federal Election, Council welcomed the Federal Government’s $1 billion commitment to secure land

corridors for a future rail link connecting Bradfield Aerotropolis, Leppington and Macarthur – a key priority of The Time Is Now.

Road infrastructure is equally critical. Projects like the Camden Bypass Extension, the second stage of the Spring Farm Parkway, and the Leppington Road Network are essential to unlock housing, reduce congestion, and improve safety. Camden Council is also calling for upgrades to Camden Valley Way, Raby Road and Rickard Road. Complementing these is the Western Sydney Rapid Bus project, which would deliver a fast, reliable service linking Camden with the new airport and major employment hubs.

Education and health care remain urgent priorities. With a significant shortage of schools, Council is advocating for new primary and secondary schools with adequate open space, expansion of early childhood services, and relief for overcrowded schools. The recently announced school at Emerald Hills addresses only a fraction of Camden’s need. In health

care, Council seeks redevelopment of Camden Hospital, a major new public hospital between Oran Park and the airport, and integrated health hubs in Oran Park and Leppington to bring care closer to home.

The Time Is Now delivers a clear message – without urgent investment, Camden risks being left behind. With the Western Sydney International Airport opening in 2026 and the population surging, every project must be delivered in a coordinated and timely way to create an integrated and resilient infrastructure network.

Although some progress has been made, such as the $12.3 million committed to planning the second stage of the Spring Farm Parkway, these efforts fall short of what’s needed. The entire project, which is vital to delivering a critical east–west transport link for the Macarthur region, is expected to cost almost $600 million. ♦

For more information on Camden Council’s The Time Is Now campaign, visit camden.nsw.gov.au/advocacy

THE TIME NOW

Camden Council is advocating for our growing community. In the lead-up to the Federal election—and in preparation for the next State election — ‘The Time Is Now’ calls for urgent government investment to support our region’s rapid growth.

ADVOCATING FOR CAMDEN

Our Advocacy Priorities include:

• Essential Rail Services

• Western Sydney Rapid Bus

• Critical Road Infrastructure

• Investment in schools and education

• Investment in new and existing healthcare

Learn more about our ongoing advocacy efforts and read ‘The Time Is Now’ publication in full at www.camden.nsw.gov.au/advocacy or scan the QR code.

Minister’s address

The Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP, Minister for Transport Infrastructure, and Minister for Public and Active Transport

Minister for Transport Infrastructure, and Minister for Public and Active Transport the Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP delivers the opening address at Partnerships 2025

Key points:

• Transport should no longer be planned in isolation, but strategically integrated with housing and land-use planning to manage urban sprawl, ensure cohesive service delivery, and create well-connected, liveable communities.

• Investments in other transport modes, alongside the opening of the Melbourne Metro Tunnel, will enable buses and active transport to better integrate into the rail system, and reshape the culture of public transport use in favour of an interchangebased network approach.

• All levels of government must take a forward-looking approach to deliver sustainable projects that can accommodate Victoria’s growth, while fostering social cohesion, enhancing productivity and strengthening the State’s long-term resilience.

This conference is a great opportunity for people to share their expertise and experience, and to have that important contest of ideas and debate, which always leads to better outcomes. We should never shy away from those difficult conversations and from challenging each other’s opinions on the best way to move forward. It’s a very healthy endeavour.

2025 is a big year in Victoria’s infrastructure calendar, and many of you are familiar with this as you have been our partners who have delivered some of the projects that have been a somewhat disruptive part of Victoria’s landscape for a very long time. Later this year, we’ll be switching on the West Gate Tunnel project and the Metro Tunnel project, which we have spent the last decade building, and so far has been largely conceptual to the public. These are transformational projects, which have effectively created a decade’s worth of disruption that our community has been weaving around without yet fully realising the benefits that will be delivered – not just in the here and now, but for generations to come.

Over the last decade, we have had a $100 billion infrastructure pipeline with 50,000 direct jobs attached to it, and we’ve embarked upon those projects knowing that we would be statistically unlikely as a government to be the ones cutting the ribbon on them.

We now find ourselves here and being able to do that, but it does beg the question in a world where governments and politicians are rightly criticised for thinking in short-term

political cycles: Why would we sign up to projects that we know, and knew when we signed up to them, had a life that most likely would’ve extended beyond the life of the government at the time?

The answer was simple: if we didn’t, we would go backwards and to stand still was also to go backwards. If we didn’t invest back then it would not only have got more expensive, but the economic and social costs of delay would have been massive.

Underpinning all that thinking was one major challenge, and it’s a challenge that is not unique to Victoria, or even Australia – it’s a challenge that all governments should be occupied with and from many different vantage points. That is the story of growth.

Melbourne will be the size of London by the 2050s. You have all probably heard that statistic bandied around quite a lot. It means when we look to how we prepare for that, we need to rethink the way we use land, our planning settings and, of course, what we need to invest in in terms of infrastructure to be able to support that level of growth.

Alongside that, there is now an elevated conversation about housing – confronting what can be a difficult truth, that endless urban sprawl just doesn’t make sense.

The cost of endless urban sprawl is that we need to continue to be able to deliver the infrastructure and services that preserve liveability to do that. That’s becoming increasingly harder.

Growth sets a key challenge for all governments, regardless of their political persuasion, and that is preserving our liveability. If you can’t guarantee to the community that you are delivering to that end, the conversation around growth turns very dark, and we are seeing that occur around the world, and in certain pockets in Australia.

As somebody who has served in social services portfolios for five years before getting into infrastructure, I believe that we should never lose sight of that social imperative to get this right, which goes to the heart of social cohesion.

The work that you all do, and your partnership with government, is really important. This is not only for building the infrastructure that we need to sustain the growth projections, ensuring a productive economy, and a strong social fabric in our State and nation, but also in order to foster a more cohesive community.

Part of the conversation we’re now having in Victoria around our transport infrastructure is to remind people that we only invest in projects like the Metro Tunnel, for example, because it enables us to add more services.

The end goal is adding more services and better reliability across our public transport network. The Government doesn’t build for the sake of it. Instead, the Government builds because it enables the delivery of something that’s

meaningful and tangible to the everyday lives of Victorians. That’s what these projects are all about.

Later this year, we’ll be in a position to deliver upon that vision, and be able to let people experience, in some very real terms, what that means in their daily commute. Whether that is travelling by road or around our rail network, Victorians will see how the Metro Tunnel project changes their journey and what it has enabled us to unlock across our rail network – not only in the Metro Tunnel corridor itself, but also along every other rail line in our network.

A population the size of London by the 2050s means that our transport network will need to support an extra 12 million trips a day by 2056 and an 80 per cent increase in private vehicle trips – that’s about 19 million trips a day. That’s a big challenge, and it is incumbent upon all governments to ensure that they are looking ahead at what we need to do across our networks to be able to sustain that. To dither will lead to significant delays and cost increases.

If we want to maintain the liveability of our State, and that which Melbourne is famed for and really prides itself on, then we have to have an honest conversation about how we grow and what that growth looks like. That conversation is happening right now and, interestingly, it’s not a conversation being driven by governments, but rather by the community.

We are now partnering with the community to work out what those best solutions are, and we’re drawing on industry expertise to help us problem solve to ensure the Victorian Government continues to invest in meeting the demands of that growth.

On that backdrop of growth, I would now like to talk about a few projects, starting with the Metro Tunnel – not only because it

happens to be a personal favourite, but because it is the single biggest transformation of our rail network in more than 40 years, since we built the City Loop.

It’s extraordinarily important for our ongoing ability to be able to add services across our network. So much of the attention so far on that project is focused on the brand-new, shiny stations under Melbourne, which are granting access by rail to parts of our city that have never had rail access before. That’s really exciting as it includes important zones like our health precinct and The University of Melbourne. For example, Anzac Station is significant, providing better connections to the Shrine of Remembrance and major events, including the Formula One Grand Prix. These are projects that have been in the minds of some of our biggest thinkers for decades, and we’re finally able to deliver them. Of course, they’ve had their challenges along the way and, sadly, they have been caught up in politics. In a perfect world, we’d rather not have key enabling infrastructure politicised when we recognise how important it is to our productivity and growth; on these occasions, governments need to just lock in and deliver.

The most important part of the Metro Tunnel project is really the capacity that it unlocks. It takes three of our busiest lines out of the existing City Loop, and doing so not only enables the delivery of turn-up-and-go services along the Cranbourne, Pakenham and Sunbury corridors, but also frees up capacity around the rest of the network.

What does that mean? We can add more services around the network – not just now, but for generations to come – and that’s really important. It also unlocks the potential for future projects because on every single rail line in our network,

The Hon. Gabrielle Williams MP provides an update on Victoria’s transport pipeline

similar to every single rail line around the world, there are things that you’d like to do that need to be done in sequence.

Until now, it didn’t necessarily make sense to do some of those things when the benefits could not be realised because of the choke point in the City Loop. By addressing that choke point, all of a sudden you open up a new wave of opportunities for continuous improvement, and I think that should be celebrated.

Later this year, we’ll be opening the West Gate Tunnel, a vital and alternative connection point, and a key freight corridor, across the Maribyrnong River from the west.

The west is not only one of Victoria’s fastest-growing regions, but it’s also one of the country’s. Therefore, having a single connection point over the river is just not going to cut it for much longer.

This tunnel will take 9,000 trucks off local roads, so it’s also a story of amenity for local communities in our west, and it will greatly improve the commute times for those coming in from the outer west, significantly cutting their commute in and out of the city by about 20 minutes. So again, it’s a project about meeting the needs that come with substantial growth.

Along the way, it’s allowed us to do some other exciting things, such as upgrading and adding 14 kilometres of cycling and walking paths. That’s also a parallel story to Victoria’s Big Build agenda more broadly – that for each project, we consider how we can also improve active transport connections in those areas. In this way, the Big Build agenda has allowed us to open new opportunities for people to walk and cycle to important transport hubs.

While we’re talking about enabling infrastructure, I will touch on the works occurring at Sunshine. This is an important project in that futureproofing story because it does three things.

Firstly, it’s the first stage of the Melbourne Airport Rail, as it requires track to be moved aside to create the spur line to the airport.

For similar reasons, it is also the first stage of the Melton line electrification, and it addresses probably the biggest single choke point and barrier to being able to add more services to Victoria’s western suburbs and region. It is untangling one of the biggest choke points or complex junctions in our network that exists right now and, by doing so, it will create dedicated pathways for suburban rail, regional rail, and freight access.

It’s incredibly important if we are going to be able to continue to add more services to that fast-growing part of our State. When it is complete, it will enable the running of up to around 40 trains an hour through that very important hub. For me, it is on the same plane as projects like the Metro Tunnel in terms of what it then enables us to do. These are forward-thinking projects, as they need to be.

As this work is being completed, we continue with our now long-running project of removing level crossings, and much of

that project has gone hand in glove with some of the other Big Build projects – in particular, the Metro Tunnel.

Shortly, the Sunbury to Cranbourne-Pakenham Corridor will be boom gate–free, and that’s important if we’re going to deliver those turn-up-and-go services down the line that we promised as a part of that project. We need to take out those intersection points – those relics of the past.

What we know from the 87 boom gates that have already been removed is that they are already paying dividends, and on many different fronts. This includes savings of about 55 hours of boom gate downtime in every morning peak, and reductions of 80 per cent of vehicle/train collisions or near misses that were sadly a feature of our network for far too long.

Therefore, from a safety, as well as an efficiency and productivity perspective, the boom gate removals are incredibly important, and our work on that program continues.

The North East Link is another project that captures the attention and hearts of those of us who love the project as much as I do. This is a 6.5-kilometre tunnel from Watsonia to Bulleen, which effectively fixes that missing link in our freeway network. Once completed, it’s going to take 15,000 trucks off local roads and reduce travel times by up to 35 minutes. Again, this is a very important project in our road network, and is a great contributor to boosting productivity not only through the movement of people, but also through the movement of freight.

There has been much discussion about the Suburban Rail Loop (SRL). It seems to me that every major project – in particular, rail project (and the Metro Tunnel is an example of this 10 years ago) – seems to have an infancy steeped in controversy and conjecture where everybody has an opinion, and there always needs to be somebody who outright opposes the project. Such is the case for the SRL. But much in the same way as we stood by the need for the Metro Tunnel, we stand by the need to make sure we have that wheel to the hub and spoke network of our rail network in Melbourne. The SRL is a transport project, but it is also the nation’s biggest housing project, with 70,000 homes planned across the corridor as part of a housing agenda that is focused on how we meet the needs of growth and how we deal with liveability. Ensuring that the homes we’re building are close to transport connections, education opportunities and job opportunities along these new rail corridors is at the heart of that vision.

The SRL will connect, for the very first time, to Monash University, which has been a long time coming and will be welcomed by the significant number of students that use that world-class educational facility. It will also connect Deakin University to rail.

There are currently 3,000 people working on that project, with work underway at all of the six station sites and tunnel boring due to commence next year. That’s just the first stage of

the SRL East, with the vision to deliver a full orbital link around the city.

For the first time, there is now a designated title in my portfolio for active transport connections, which aligns well with our broader housing agenda. There has been a lot of discussion led by my ministerial colleagues – including Minister Kilkenny and Minister Shing – around the creation of activity centres and precincts, and the planning of communities properly. This includes thinking about how people move and where we can add volumes of homes to deliver a good quality of living – and transport is at the heart of that.

This has allowed us to think of transport in a couple of different ways, and to bring life into areas of our transport network that have, up until now, probably not enjoyed the same level of sentimental attachment as others.

The first part of that is thinking about our active transport links, including how we encourage people to leave their cars at home for short trips, and understand how people move within their localised communities.

The second part is allowing our bus network to come into its own. Last year, we made the single biggest investment in buses in the State’s history: $180 million. This was backed up in our 2025–26 Budget with another $160 million, largely focused on our fast-growing communities in the north and the west. Alongside that is this opportunity to look at how we ensure our bus networks are doing more of the heavy lifting, both in those localised trips, and also in connecting people to other modes of transport, including heavy rail.

That touches on a very key part to round back to my point on the Metro Tunnel project, and that is transforming our transport networks, as well as the culture of our transport use, into one of interchange.

That is a feature of every major public transport network in the world. In Melbourne and Victoria, it is not something that we have been particularly well-versed in until recently. But Metro Tunnel and our population growth are changing this. Increasing density and demand means you can start to deliver a frequency and a service level that makes intermodal transition more effective – because there are great efficiencies to be had by changing modes or, indeed, just by being on the same mode but changing trains.

Of course, this works best when you don’t have to wait too long between services, and that’s what we are building; that’s the change that comes online with Metro Tunnel.

In terms of the Metro Tunnel project, we will always be compared to Sydney Metro or to Crossrail in London, but ours is quite a unique project because it is not a discrete rail line and it’s integrated with the rest of our network.

That means in turning on the Metro Tunnel, we have to re-timetable the entire public transport network. This is not just trains, but also involves a lot of re-timetabling of buses.

Again, this is about starting to introduce our community to a culture of interchange in a much greater way. This will be through better service levels and alignment between our bus and rail services to ensure that that interconnection piece is activated, and that we can genuinely deliver an integrated public transport network.

All of the aspects of our transport, particularly our public transport agenda, have been to deliver upon that vision, and ultimately to make it easier for people to get around and make our public transport more accessible. We want young people to become fluent in the use of our public transport network, and we want them to carry that into adulthood. This is about cultural change. It’s not just about the infrastructure – it’s also about how we encourage the use of that infrastructure for a long time to come.

In closing, never has it been more important to have governments that look ahead, that take the challenge of growth head-on, and invest to meet the demands, as well as to utilise the opportunities for job creation that comes with growth.

It wasn’t that long ago when the civil construction sector here in Victoria was on the decline, but that’s not been the story for the last 10 years. We’ve had a very healthy employment profile in government projects, and that’s how it should be.

It would’ve been really easy for a politician to stand and admire the challenge of growth, to point the finger at others for it, and to capitalise politically by making it other people’s problem. But that would not have been the right thing to do.

Whatever the political colour of the government, we must always prioritise policy over politics and delivery over delay. That’s how you bring down the costs and ensure we’re continuing to preserve the liveability that not only Melbourne, but our country, is famed for.

That’s also how we can continue to preserve the social cohesion that we have overwhelmingly enjoyed in this country and boost productivity, which we all know we have to do. It all takes investment and partnerships.

Governments can’t do it alone. We’re reliant on your expertise, and the contest of ideas to help us navigate the best option for the time.

As a policymaker in a government, I’m extraordinarily grateful for the level of investment, interest, and energy that we have in our development and transport sector broadly. To that end, we are put in very good stead as a consequence of your passion, knowledge and expertise, and I hope that is long the case.

I’ve spoken a lot about the projects that are underway, but there is still much more to do. There will always be more to do. That is the job of a good government – looking ahead and working out what that next frontier is, and the pathway to deliver upon a vision that ultimately keeps our community strong, and ensures that we can continue to enjoy the levels of prosperity that we do right now for generations to come.

M7-M12 Integration Project transforms transport to Western Sydney

NorthWestern Roads Group (NWR), whose shareholders include QIC, CIPPB and Transurban, is hard at work building and managing Sydney’s transport infrastructure of the future as part of its responsibilities operating and maintaining two of the city’s most significant motorway assets, Westlink M7 and NorthConnex.

Westlink M7 is a 40-kilometre electronically tolled motorway that forms part of Sydney’s orbital network, connecting the M5 South-West Motorway at Prestons with the M4 at Eastern Creek and the Hills M2 at Baulkham Hills. The M7 Motorway

facilitates efficient travel across Western Sydney, while driving social and economic growth along the corridor.

Meanwhile, NorthConnex is a state-of-the-art twin tunnel system that links the M1 Pacific Motorway at Wahroonga to the Hills M2 Motorway at West Pennant Hills. Spanning nine kilometres, it serves as a crucial bypass for heavy vehicles off Pennant Hills Road while improving overall network traffic flow.

Together, these motorways enhance connectivity across Greater Sydney and contribute

Ian Whitfield, Executive General Manager, NorthWestern Roads Group

to environmental sustainability by reducing vehicle emissions, and improving local air quality. They are also a linchpin in Sydney’s future development

‘The M7-M12 corridor is vital to Sydney’s vision to shift its city centre and heart to its west. This is supported by the incredible development happening across the western suburbs, underpinned by the soon-to-be-opened Western Sydney International Airport,’ says NWR’s Executive General Manager, Ian Whitfield.

‘We are proud to partner with Transport for NSW to build the roads that help facilitate this exciting new era for Australia’s greatest city,’ he says.

Closing the gaps

At the moment, NWR is fully focused on the M7 widening and M7-M12 Integration project, which is set to transform the transport landscape of Western Sydney. With an estimated cost of approximately $1.7 billion and an expected opening in 2026, this ambitious initiative will widen 41 bridges along the M7 Motorway, and significantly enhance access to key commercial centres and residential areas.

A notable project achievement has been the opening of a realigned Wallgrove Road to traffic. This is a

crucial step in linking the M7 to the future M12 corridor, paving the way for improved connectivity in the region. The project employed innovative construction techniques, such as the incremental launching method for two bridges over live traffic, allowing work to progress while maintaining access for motorists.

This year, the Stage 2 Design and Landscape Plan was published on the M7-M12 Integration project’s website.

This plan highlights the proposed shared user path upgrades to rest areas, and artistic installations along the project’s footprint. Everything has been thoughtfully designed to enhance the public’s experience and the infrastructure’s aesthetic appeal.

On completion, the integrated M7 widening and M7-M12 corridor is expected to reduce travel times by 30 per cent between Marsden Park and Liverpool. Right now, the Continuous Reinforced Concrete Pavement and bridge construction is complete. Work has started on the asphalt for the new third lane, and milling and resheeting of existing lanes began in September 2025.

Installation of Intelligent Transport System devices and tolling gantries is already underway.

In the broader context of NWR, the M7 widening and M7-M12 Integration complements the existing NorthConnex asset. Together, these projects represent a significant investment in the future of Sydney’s transport infrastructure, promising to deliver improved efficiency, connectivity, and accessibility for all road users.

Next-generation infrastructure

NorthConnex serves as a vital component of Sydney’s transport infrastructure, and game-changing connection between Greater Sydney and the Central Coast. This impressive project connects the M1 Motorway in Wahroonga to the Hills M2 Motorway through twin nine-kilometre tunnels, designed to the highest safety standards and equipped with next-generation technology.

The benefits of NorthConnex extend far beyond connectivity. By diverting more than 6,000 trucks per day off Pennant Hills Road, the project significantly improves local air quality and returns local streets for community use. Motorists can bypass up to 21 traffic lights, and experience travel time savings of up to nine minutes or 20 per cent faster travel, during peak hours. This enhances trip reliability for individuals and businesses while streamlining freight transport, contributing to regional logistics efficiency.

The nine-kilometre twin tunnels each accommodate two large 3.5-metre lanes, along with an additional breakdown lane for emergencies. The tunnel’s alignment generally follows that of Pennant Hills Road, but eliminates sharp

corners and steep hills, making journeys faster, safer, and more efficient. This reduces operational and maintenance costs for motorists, further enhancing the appeal of this critical infrastructure.

NorthConnex’s scale is remarkable. It is Australia’s deepest tunnel, reaching depths of 60 metres, and is one of the longest tunnels in the country. The project has seen an investment of around $3 billion and, over its lifetime, NorthConnex has created approximately 8,700 jobs for New South Wales, showcasing

its significant impact on the local economy.

Delivered in partnership with the New South Wales and Australian governments, and constructed by the Lendlease Bouygues joint venture, NorthConnex exemplifies a commitment to sustainabilty and community benefit.

As the M7 widening and M7-M12 Integration progresses, the synergy between these two major infrastructure projects promises to further enhance the transport network in Western Sydney, ultimately benefiting residents and businesses alike. ♦

Safety management systems help reduce incidents in the heavy vehicle industry

By Matthew Bolin, Manager of Fatigue and Human Factors, NHVR

People are the driving force behind success in the heavy vehicle industry.

As such, everyone in the heavy vehicle industry has a role to play in ensuring that their transport activities are conducted safely.

The most effective way to do this is by integrating safety management principles into everyday operations.

The NHVR defines safety management as the systematic approach to considering how human and organisational performance, technology, and the operational environment interact in effectively managing safety risks.

For any transport organisation, the key lies in adopting a systematic approach to safety management, one that is intentional and well considered opposed to purely ad hoc or reactive activities and processes. This is achieved through the implementation of a safety management system (SMS). Having an SMS in place can be one of the most effective ways to demonstrate that your business is meeting its safety obligations under the Heavy Vehicle National Law.

An SMS is a structured approach to managing safety that includes outlining the necessary organisational structures, accountabilities, policies and procedures, which is integrated throughout the business wherever possible. It also supports the continuous improvement in operational safety, and provides a safer environment for customers, contractors and the public.

The effectiveness of safety management activities is always strengthened when implemented in a formal, systematic manner. The NHVR SMS model provides a framework for this, built around four components that focus on:

► policy and documentation

► risk management

► assurance

► promotion and training.

While this may seem like a lot, an SMS should be proportionate to the level of risk within the business, taking into account its size, type, nature and operational complexity. Many businesses already have elements of an SMS in place (perhaps without knowing it) – a formalised SMS simply brings these components together in a structured manner to ensure that all safety-related elements of the business are considered.

While the safety of equipment, tools and technology has significantly advanced in modern times, the role of people within a system remains critically important and cannot be overstated.

Human performance in safety critical systems is shaped by a range of influences known as ‘human factors’. These include an individual’s capabilities and limitations, as well as the people, technology and environment in which they work. As a result, their interpretation of situations varies as they adapt to meet demands of their work environment, assessing risk and making decisions based on this assessment.

Consideration of the factors that influence performance can optimise the human contribution to safety across all levels of the system. A systematic approach to positively addressing human factors using the four components of an SMS ensures that these principles are integrated into all aspects of heavy vehicle operations.

The NHVR website provides guidance material, tools and templates to help you develop and implement an SMS in your business (www.nhvr.gov.au/sms). ♦

For more information, email info@nhvr.gov.au or phone 13 NHVR (13 64 87).

Demographer address: Infrastructure for tomorrow – planning for Australia’s demographic shift

Simon Kuestenmacher, The Demographics Group

Demographer

Demographer Simon Kuestenmacher provides demographic insights on population growth, skills shortages and infrastructure challenges

Key points:

• While the Australian economy will continue to grow, concurrent population growth –with forecasts of nearly four million more people by 2035 – will place sustained pressure on housing, transport networks and essential services.

• Infrastructure planning will need to account for rapid growth on the urban fringe of major cities, while also preparing for longer-term densification of middle suburbs.

• Persistent skills shortages and an ageing workforce will likely add to bottlenecks in delivering infrastructure.

Before we dive deeper into the Australian population, we need to figure out what we actually do. We are a rather simple economy, aren’t we? In fact, we only do four things that matter to the rest of the world. We export a bit of stuff that we dig out of the ground and we grow a couple of things on top of the ground – mining and agriculture are obviously our two biggest exports. Then, we entertain a few people (that is tourism), and we also educate a few folks (international students) – and that’s it. Those four things cover more than 80 per cent of our exports. This is what drives the wealth and prosperity of our nation.

And we can talk all we want about diversifying the economy, but how would we do it? For instance, we could value-add a manufacturing smelter in the country, and export steel rather than iron ore. But all this value-added manufacturing, of course, needs energy, as it is extremely energy-intensive. Unless we massively lower energy, none of this will happen. So, my forecast for the next 10 years is that Australia will continue to rely on exactly those four things. The economic diversification that we are dreaming about will not occur.

We have been falling in all these big international indexes about global economic complexity. According to the global Economic Complexity Index, Australia ranks 105th out of 130 countries in terms of how complex our economy is, behind Botswana and Uganda. So, it is simple what we do, and I think the idea that we can diversify the economy is a pipe dream at the moment. For now, this is the wealth that we rely on. None of those four things is under structural risk. Our economic business model in Australia continues to deliver wealth, and we can expect much more of the same moving forward.

So, now let’s dive deeper into the population forecasts for Australia. We can see quite a number of people in their 30s now moving into their 40s – that’s the millennial generation, our biggest generation by a long shot. But that’s the status quo.

We want to know what Australia looks like in, let’s say, 10 years’ time. Forecasting our population only a decade ahead is easy because we know how many babies are going to be born; and we also know who isn’t going to make it until the next decade. Lastly, as a country, we dictate migration intake. So, there’s only so much that could go wrong with our forecasts.

So, let’s have a look at Australia in 2035. The first observation is that we’ll be adding close to four million people. That is a lot of growth – these people will need to be housed and supported by a bucketload of infrastructure. So, the good news here is no-one working in the infrastructure sector will be bored over the next 10 years. But this population growth isn’t evenly distributed across the whole spectrum, with some segments seeing much more growth than others. We will see more babies in the next 10 years, despite record low birth rates, driven by the biggest generation ever – millennials – having children. Then, this will slow down because, ultimately, a smaller cohort will be charged with having children.

We will also see the power of migration really start to play out. In Australia, just over 70 per cent of our population growth is imported from overseas. We are well and truly a migration nation. Those who make up our migration intake are young – more than 90 per cent of migrants are under 40 years of age, but the biggest portion of migrants, about 80 per cent, fall into a narrow age band from 18 to 39 years. Just under half of all international migrants are international students, around the 18 to 23 age range. Of course, Australia wants the skilled migrants, and wants them as young as possible – we want them to be productive worker bees in the economy for as long as possible. That leads us to a situation that is extremely rare around the developed world. Despite the millennial cohort pushing from their 30s into their 40s, we still see population growth in the 30s age group. That is unheard of. It’s a privilege to have this because that ensures we have economic activity, and we have workers in the system.

The single year of age that will see most growth in the coming decade is 43. And that’s significant because at 43, statistically, people spend more money than at any other point in their lives. By this stage, they’ve had a couple of promotions, they’ve had all the children they’re going to have, and they still haven’t paid down their mortgage. This means that every penny they earn is going straight out the door back into the economy.

This is, of course, wonderful news for businesses – they love us pushing the biggest generation ever through the highest spending phase of the life cycle. Who isn’t a fan of that is the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). The RBA still looks at inflation with a bit of a warning look on its face and will consider curbing it by raising interest rates.

However, it turns out that this high-spending cohort of millennials spend every dollar they have regardless. So, that, of course, means that the RBA needs to keep the interest

rates elevated for longer. And who is suffering in the process? Well, the bottom third of society is being bled dry. So, there are important social equity issues to consider when we think about what the future might look like.

Of course, there might be good news as we push the big baby boomer cohort into retirement completely over the next decade. That should be welcome news for the RBA. Traditionally, once a person has stopped earning a wage, they instantly turn into a poor penny-pinching pensioner: a deflationary asset. However, it turns out that’s not actually the case with baby boomers – they’re a different breed. They’re the richest generation who’ve ever lived in Australia, and many are already retired. We have detailed spending data about them available. Baby boomers in retirement increase their spending in every category that we measure except for one: charitable giving, which is significantly down. But in all the other segments, baby boomers spend more money. So, how I read this is that interest rates, on average, must be higher in the next decade than they were in the last decade, just because we have the biggest and richest generation consuming like there’s no tomorrow. So, this will need to be counteracted in some way.

While there’s more that feeds into interest rates than just national consumption levels, it does probably mean that the money for all the wonderful projects that the infrastructure sector wants to build won’t be overly cheap. So, the dream of deliciously low interest rates probably won’t become true. I also want to draw your attention to those on the far side of the population – 85-year-olds. Eighty-five is another important statistical year because it’s called the median age of death. Half of 85-year-olds will need care on a daily basis and, in the next 15 years, we are doubling the 85-plus cohort from 590,000 people today, to 1.2 million people by 2040. Can we double the aged care system in 15 years? Absolutely not. Even if we were to massively increase the migration intake, this is a trainwreck in the making, and it can lead to catastrophe. This is the single most extreme skills shortage Australia is experiencing.

In fact, the skills shortages that many in the infrastructure sector are experiencing now is here to stay and it’s likely to worsen. A large cohort of baby boomers are retiring and, unlike in the past, when we added more people to the workforce, this is not happening this time around. Despite the popular narrative of international students coming to Australia to drive Ubers, the

Demographer Simon Kuestenmacher outlines the demographic trends shaping Australia’s future

million international students do not actually contribute to the workforce at scale, and will need to be discounted. Additionally, more than half of our year 12 graduates head straight into the university system, which means they ultimately only contribute to the workforce once they hit their mid to late 20s. When you consider this, that’s not very many people entering the workforce each year. And finally, of course, the big pile of millennials will add to these pressures, as they leave the world of work, at least for a little bit, to go on parental leave.

For those working in the sector, the skills shortage, and its impact on staffing pipelines and operations, will be the single biggest worry in the decade to come. And of course, that means that all those buzzwords being thrown around – artificial intelligence (AI), automation and robotics – will come to be our friends. While it remains to be seen how much these tools can help us, they will most certainly not lead to high unemployment in Australia. We will continue to operate on low rates of unemployment over the next decade. In periods of low unemployment, wages are higher, and the power balance shifts towards employees, and that’s something employers will need to work with. But wait, there’s more: the skills shortage has an evil twin called ‘the retirement cliff’. This measures what share of the workforce is already at retirement age – that is, five per cent of all workers in Australia are 65 and older – but more importantly, it measures what share of the workforce is nearing retirement, at the 55 to 64 age range. In 10 years’ time, those in this age bracket fall off the proverbial retirement cliff. Nationally speaking, that’s 15 per cent of the population.

Looking at a couple of jobs that well and truly keep the infrastructure system of Australia operating, civil engineers, air traffic controllers and regional planners are faring relatively well. While these roles are being impacted by the skills shortage, they are not further exacerbated by the additional pressure of losing people to retirement. This is more prominent in physically taxing jobs, including bricklayers and fitters resembling the national average, that can’t easily be undertaken by workers well into their 60s and 70s.

Every industry in Australia relies on truck drivers, and we currently have a shortage of 40,000 truckers. This is a significantly ageing workforce, with around 26 per cent of truck drivers aged between 55 and 64 years old. Remember that until a decade ago, we actively pushed truck drivers out of the workforce once they hit 55 when they became an expensive human resource. Now, we beg them to stay on because we don’t know how to solve this, and it is unlikely that we’ll have truck-sized self-driving vehicles on the roads anytime soon. We will still need humans to do this for a long time, and in the meantime, the demand for truck drivers only increases, creating a bottleneck to be dealt with.

Additionally, any job that has ‘machine operator’ in it will face severe shortages, and terrible bottlenecks. Where do

you get your crane operators from? That won’t be automated anytime soon. So, how do you deal with this? There is strong competition for those workers, and it slows the whole system down. The same can be said for jack-of-all tradespersons, which means employers will employ more qualified, more expensive tradies for these tasks, driving up operational costs.

Of the large professions in Australia, bus drivers by far are the oldest, with well over half of bus drivers more than 55 years old. Who is going to be impacted by this bottleneck? Well, it is likely to be the poorer regions of our cities because these are the areas that are more likely to rely on a bus network, rather than a tram network or private vehicles.

So, now that we know how many of us there will be, or how many workers there won’t be, where do we actually live? Where will we settle in the next 10 years? Interestingly, every city in Australia looks exactly the same. Every city in Australia looks like a fried egg, where all the employment opportunities are clustered in the CBD, in the egg yolk of the city, figuratively speaking. Those who want to avoid long commutes pay a premium to live closer to the egg yolk. This means that generally, higher-income households live closer to the egg yolk, compared to lower-income households, which live closer to the edge of the frying pan, so to speak. Then along came the COVID-19 pandemic, which really acted like a spatula, turning our fried egg city into scrambled egg.

During this time, the CBD remained the most dominant job centre, but ultimately, many jobs were spread more evenly across the frying pan – as we worked from our spare bedrooms and our kitchen benches – and we didn’t need to commute to work all that much. For a time, people – especially in Melbourne – realised they could move somewhere more affordable, and get better value for money in the outer suburbs. Once people started doing this, they quite quickly realised that remote work is only a reality for a very small number of people. Nowadays, most people work in a hybrid fashion, which means going into the office at least once or twice a week. So, everyone has stayed within a magical two-hour drive-time tomato sauce radius – and I’m really stretching the metaphor here – around our CBDs. So, anything within the two-hour drive-time radius of any of our major CBDs is absolute boom town for growth.

Outside of the two-hour drive-time radius, cities operate differently. In major centres, people bring their jobs with them – but in regional towns, people rely on the supply of local jobs, local housing, local health care, and a local school or child care. Those regional towns that can provide all four will see growth, and those where even one of the four is missing will struggle. That is the simplistic future of urban settlement in Australia. People will ask how I am so certain that this pattern will continue following the pandemic. This can be explained by the single biggest driver of our moving populations from the inner city to the urban fringe – which

would’ve occurred even without the pandemic. This is simple demographics at play.

By sheer demographic dumb luck, around the time the COVID-19 pandemic started, millennials started to grow their families. At this point, the millennials were already partnered up and living in inner-city apartments. Add your 1.5 babies to the mix, which means apartment living becomes cramped quite quickly, and a three-bedroom house is required. However, this housing stock isn’t as widely available in inner-city suburbs, and millennials can’t move to the middle suburbs like their baby boomer parents did when they were younger. This is because the baby boomers are hogging the three- and four-bedroom housing stock as empty nesters and, alongside this, were fantastic NIMBYs over the last few decades, blocking developments. This means millennials must move to the urban fringe where family-sized housing stock is available at scale. With 12 years’ worth of baby-making left in the millennium tank, this is how long we’ll continue to see the population shift to the urban fringe, and shrink in the middle rings as more people in their early 20s move out of the parental home, move to the inner city, and then move to the fringe.

Meanwhile, the downsizing narrative is exaggerated among baby boomers in Australia. For all intents and

purposes, the baby boomer generation is not downsizing less until they start dying at scale, which will happen when the millennials have finished having children in about 12 years’ time. This is when we will well and truly densify the middle suburbs. In the meantime, new overseas arrivals move into the inner city and millennials to the urban fringe. This is the general game of population settlement. In the next decade, we will start bulldozing the quarter-acre blocks in the middle suburbs at scale and build medium- to high-density housing stock wherever we can. Therefore, infrastructure needs to settle on the middle suburbs in a decade’s time – for now, it’s the urban fringe and inner city.

To summarise, this coming decade is going to be defined by strong population growth, our national business model guarantees Australia will continue to be wealthy, and the skills shortage will continue to be an ongoing area of concern. For businesses in the sector, this means you must be an employer of choice; retention is the name of the game. It also means you must embrace all those buzzwords, including AI, automation and robotics, to squeeze a bit more creativity out of your existing workforce. Unfortunately, we must do this while interest rates, in my humble suggestion, will be more expensive than you were secretly hoping for, but that is simply what you need to do.

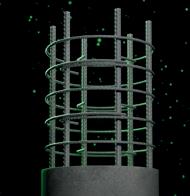

SENSE 600® Australian made sustainable steel

Building a better tomorrow, without changing how you build today.

Uses up to 16.7% less raw material than our standard 500N reinforcing steel and made from 100% scrap metal.

Driving progress to decarbonise the infrastructure industry doesn’t mean having to change the way you work. SENSE 600®, our new reinforcing bar innovation, brings you lower Scope 3 emissions without compromising on performance or qualityall while integrating seamlessly into your existing workflows. Together, we can create a construction industry where sustainability isn’t just an option - it’s the standard. It just makes SENSE

Delivering up to 39% lower embodied carbon when using in place of our equivalent load capacity standard 500N reinforcing steel.

www.InfraBuildSENSESolutions.com

Confidence from third-party certification from GECA (SSPv1.0i-2019) and meets Australian Standard AS/NZS 4671.

Unlocking growth, investment and a sustainable future through transport

Of the numerous challenges affecting Australia’s transport sector, two opposing problems come to mind. One is urban congestion: the traffic bottlenecks that blow out travel times, frustrate commuters and stymie productivity. The other is the ‘tyranny of distance’: the painful isolation of our communities, which, like congestion, impacts negatively on travel times and productivity.

The bulk of Australia’s transport infrastructure is concentrated along our east coast, where population density is highest. While there are widespread rail and road networks in each capital city, there are limited interstate connections.

Increasing traffic is a major issue in many cities. A 2024 transport opinion survey by The University of Sydney’s Business School found that people’s main issues for transport were road

congestion, and the increasing pressure on the road system linked to population change and a rising number of vehicles.1

Australia is crying out for an evolution of the transport infrastructure that shapes our cities and regions. Innovative transport planning has the potential to forge new economic, social and environmental progress. Better

Brisbane Metro. Image courtesy of Brisbane City Council

connections and faster commutes could change the way that Australians have long thought about public transport, and encourage passenger uptake, leading to reduced emissions and a more sustainable future.

To support the needs of a growing population, the Australian Government has outlined future goals around sustainability, economic competitiveness, social connectivity and regional development. This includes the recently announced climate change target of a 62 per cent to 70 per cent reduction on 2005 emissions by 20352, and the National Housing Accord target of 1.2 million new, well‑located homes built in the five years to 20293

There are further opportunities for decarbonised transport and sustainable growth in future focused mega projects, executed in tandem with revamping existing infrastructure and leveraging new transport oriented developments.

Transforming connections between Australia’s eastern major cities

A high speed rail network to connect Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne, as well as regional communities along the east coast, is a logical place to start in Australia, says Malcolm Smith, Australasian Cities Leader at built environment consultancy Arup.

‘The planned high speed rail connecting Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne has the potential to redistribute population densities across the east coast by supercharging accessibility. It may take generations to fully realise that change, but it starts with high speed rail and the communities growing from each of the cities that will deliver a build up of value and opportunity,’ Smith says.

An added benefit of high-speed rail is that it can lead to improved air quality and decreased road congestion, especially when powered by renewable energy. Improving mobility between urban centres provides more job opportunities and lifestyle choices, greater housing options and, ultimately, a more productive economy.

Australia stands to reap economic benefits, particularly in small towns where populations are declining, and there is limited access to infrastructure and services. The challenges will lie in the scale of investment, especially when considering recent increases in the cost of labour and construction equipment. Successful funding models for mega projects around the world utilise Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) and other contracts that manage the fiscal burden on the government. Effective PPPs require clear understanding of risk and shared governance, articulating wider economic benefits – like land value uplift and regional growth – beyond just fares.

Bus rapid transit: flexible, scalable urban mobility

Bus rapid tansit (BRT) is another major tool in transforming Australia’s transport networks. BRT leverages existing bus routes and adds service upgrades, including increased frequency of services, dedicated bus lanes, and electric vehicles.

While other forms of transport renewal require hefty investment, BRT offers a cost effective solution to improving connectivity at metropolitan scale. The system uses existing roads,

so it’s quick to implement – there’s no need to lay tracks, build tunnels or construct bridges. From a political perspective, the speed of realised benefits can be particularly appealing.

A BRT network also integrates easily with existing infrastructure such as pedestrian and bike paths, and train stations. For a growing, developing precinct, they offer flexibility since new services can be added and routes can be moved as demand develops over time. In addition to encouraging mode shift from cars to public transport, zero‑emission hydrogen and electric buses offer further sustainable benefits to the community.

Arup’s major transport infrastructure projects worldwide

High Speed 2, United Kingdom

Arup designed the net zero Interchange Station at Birmingham International that will form a major part of the High Speed 2 (HS2) railway line in the United Kingdom. Once operational, the HS2 will transport passengers from London to Birmingham in 49 minutes, which is 35 per cent faster than today’s train network.

Arup is also playing a civil and environmental consultancy role,

High Speed 2, United Kingdom

supporting the HS2 vision to be zero carbon, innovative, and on time.

Watching this development in action, Australia could leverage some valuable lessons – including from the 33,000 jobs created by the project and the more than 3,400 businesses involved in the build.

Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway, Hong Kong

Held up as one of the most efficient and safe urban rail networks, the Hong Kong Mass Transit Rail (MTR) carries more than four million passengers per day around Hong Kong Island to Kowloon and the New Territories. Arup played an essential engineering design role in the delivery of the Shatin-to-Central Link, including the Admiralty Station expansion to become a four-line interchange.

MTR’s business model integrates property development with railway expansion so it can develop land near stations and along railway routes. This means commercial and residential hubs are built near public transport to support local economies and urban regeneration.

TransMilenio, Bogotá, Colombia

TransMilenio’s BRT was set up in 2000 to reduce serious traffic congestion,

road fatalities and pollution. It covers 112 kilometres throughout the city, services more than 2.56 million passengers per day, and is credited with decreasing traffic deaths by 92 per cent and air pollution by 40 per cent.

In recent years, TransMilenio has added 296 new low- and zero-emission buses to its fleet. Despite this update, the TransMilenio has struggled to keep pace with population growth. The city is now planning a metro network to complement the BRT.