Captivating the Audience

When Traditional Music Makes a Spectacle at Lake Toba

Accumulating Cultural Actions for Sustainable Living Sandeq Boat Knowledge Transmission and Character Education

VOLUME 9 772406 806005 ISSN 2406-8063 15 THE CHARMS OF INDONESIAN CULTURE

2022

Indonesia Bertutur

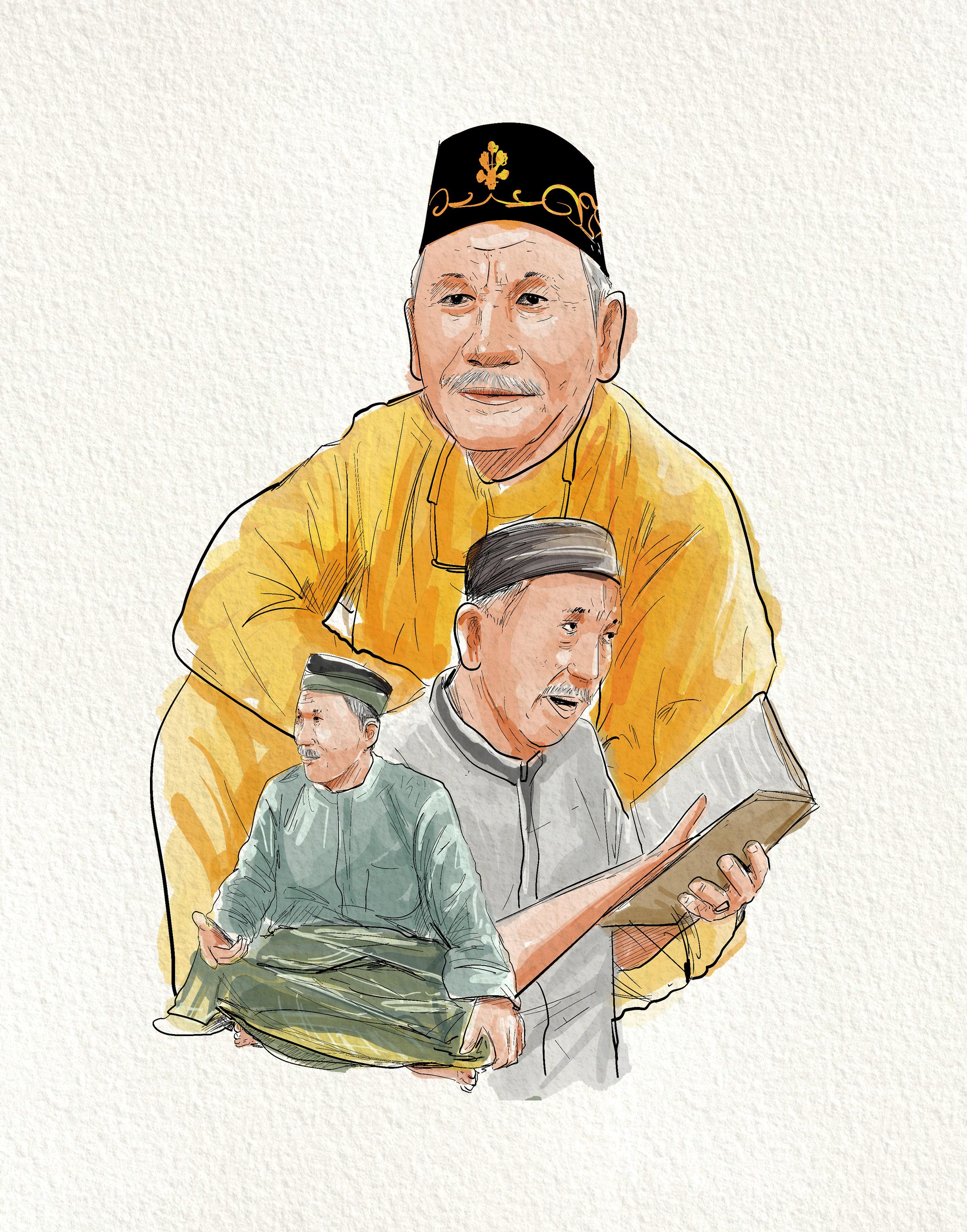

Muhammad Ali bin Achmad (Ali Pon)

courtesy of Zul Lubis Zul Lubis

RESTU GUNAWAN Director of Cultural Development and Utilization Directorate General of Culture

Muhammad Ali bin Achmad (Ali Pon)

courtesy of Zul Lubis Zul Lubis

RESTU GUNAWAN Director of Cultural Development and Utilization Directorate General of Culture

Praise be to God, the Almighty, who made it possible for us to present Volume 15 of the Indonesiana Magazine to our dear readers at the end of 2022. Motivated by the appreciation and enthusiasm of loyal readers of Indonesiana Magazine, the Editorial Team doubled-down their effort to deliver the best publication possible. This year, the Indonesiana Magazine is bilingual, in Indonesian and English. We hope that the Indonesiana Magazine will become a medium for cultural diplomacy that introduces and shares information on the rich culture of various regions in Indonesia.

This year has been a proud year for us, for Indonesia holds the G20 Presidency to host the event. Indonesia promoted the spirit of “Recover Together, Recover Stronger” by implementing relevant activities, one of which is a series of cultural activities by the Directorate General of Culture, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology. The Cultural Events section expresses the spirit of culture through articles on

Indonesia Bertutur/InTur (‘Indonesia Tells Stories’ Festival), Festival Musik Tradisi Indonesia-FMTI (Indonesia Traditional Music Festival), and Collective Culture

Actions for Sustainable Living. The section also tells cultural stories from various regions of Indonesia. It ranges from Sandeq boat, part of the Gerakan Bangga Buatan Indonesia—GBBI (Proud of Indonesian Products National Movement), Revitalizing the North Maluku Regional Language, Awaken the Dragon in Glodok Chinatown, to Cisitu Leuweung Hejo Customary Forest of Ngejo Community.

We organize cultural programs based on the Objects of Cultural Advancement, including traditions, rituals, traditional ceremonies, performing arts, knowledge, and cultural celebrations. Not only that they carry practical functions, but they also contain values related to the human life cycle. The appreciation we received from various countries on the artistic presentations and cultural performances during the G20 series of activities should motivate us to continue

to develop, utilize, protect, preserve, and promote our culture to everyone. As we bid welcome to 2023, we hope that the condition of the cultural sector in Indonesia will continue to improve so that we can promote and introduce more cultural values to the broader society at home and abroad.

Various culture stories of the Archipelago that are written and illustrated in Indonesiana Magazine Volume 15 are proof. They are proof of the commitment of the Directorate General of Culture, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, through a program managed by the Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization in carrying out cultural missions conforming to the Law on the Advancement of Culture Number 5 of 2017. We hope this publication will inspire our readers, especially Indonesians, to contribute to the continuous advancement of culture, appreciate the works of different regions in Indonesia, and keep on maintaining the flame of culture.

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 1 FOREWORD

THE CHARMS OF INDONESIAN CULTURE

KILAU BUDAYA INDONESIA

Advisor HILMAR FARID

Pengarah HILMAR FARID

Project Director

RESTU GUNAWAN

Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan

Managing Director

YAYUK SRI BUDI RAHAYU

Penanggung Jawab

RESTU GUNAWA N

Editor in Chief SUSI IVVATY

Direktur Pengembangan dan Pemanfaatan Kebudayaa n

Executive Editor

SINATRIYO DANUHADININGRAT

Content Editor

ALFIAN SIAGIAN

Koordinator Umum & Pemimpin Redaks i BINSAR SIMANULLANG

Language Editor

MARTIN SURYAJAYA

Greetings

Redaktur Pelaksan a SUSI IVVAT Y

Photo Editor SYEFRI LUWIS

Secretary

Redaktur Naska h MARTIN SURYAJAYA

JESSIKA NADYA OGESVELTRY

Design and Layout

ALFIAN S. SIAGIAN

ZUL LUBIS

Proofreaders

PRIMA ARDIANI

ANNISA MAYASARI

Redaktur Fot o SYEFRI LUWIS

Translator

DWI ANGGOROWATI INDRASARI

Tata Letak

WIESKE OCTAVIANI SAPARDAN

Contributors RENNY AMELIA SUSANTI

Fotografe r

PRITA WIKANTYASNING ANGGORO CAHYADI

JESSIKA NADYA OGESVELTRY

THAMRIN JUNAIDI NADAPDAP

YUDHI WISNU ARYAND I

Administration AHMAD ZUNITA

Sekretariat

As we near the end of 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic has not subsided; the nation and its citizens are again worried about the scourge of a reported new variant. However, after suffering and hardships, we are better prepared to face it, especially since vaccines are readily available. During the G20 Presidency, Indonesia raised the theme “Recover Together, Recover Stronger” and gathered the world leaders in Bali in September 2022. The culture ministers’ meeting in Borobudur themed “Culture for Sustainable Living” also brought great hope for culture. We witnessed the grassroots involvement in the declaration of the Borobudur Mandate (Amanat Borobudur). Discover more in Indonesiana Magazine Vol. 15.

POKJA PENGEMBANGAN DIREKTORAT PPK

E. CHRISTISIA MELATI PUTRI SORAYA AIDID

Distribution RACHMAT GUNAWAN

HERY MANURUNG

BAYU HARDIAN

YUDHI WISNU ARYANDI

Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology Republic of Indonesia

Kementerian Pendidikan, Kebudayaan, Riset, dan Teknologi Republik Indonesi a

Directorate General of Culture

Directorate of Culture Development and Ultilization

Direktorat Pengembangan dan Pemanfaatan Kebudayaan

The Indonesiana Magazine truly exists to ignite and promote cultural works in various fields and at different levels across all regions of the Archipelago. The Indonesiana Vol. 15 features sections of fascinating articles by writers and researchers who are experts in their fields. The Main Topic continues to feature the elements inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) lists and focuses on Saman dance, Pantun (joint nomination with Malaysia), and Keris. We have not covered the three elements in previous volumes.

Gedung E . Lt. 9 , Jl. Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 4-5 Senayan, Jakarta 10270

Building E. Lt. 9, Jl. Jenderal Sudirman Kav. 4-5 Senayan, Jakarta 10270

(021) 5725534

(021) 5725534

(021) 5725534

indonesiana.diversity@gmail.com

http://kebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.id

(021) 5725534 indonesiana.diversity@gmail.com http://kebudayaan.kemdikbud.go.i d

Indonesiana Magazine aims at promoting Indonesian Culture and is not for sale.

Majalah Indonesiana bertujuan untuk promosi budaya Indonesia, dan tidak diperjualbelikan. Komentar atas artikel, foto dan lain-lain ditujukan kepada: indonesiana.diversity@gmail.co m

Comments of articles, Photographs etc, can be send to: indonesiana.diversity@gmail.com

Front Cover:

Gaya bertenaga buruh pabrik genteng Jatisura (foto: Pandu Rahadian )

Storytelling through Body Movements –Irnie Wanda

Sampul belakang: Penari Caci dan kain Songke. (foto: Dodi Sandradi)

Back Cover:

A fisherman on Sandeq sailing the open sea –Muhammad Ridwan Alimuddin

The Cultural News section covers articles related to activities of the Directorate General of Culture, such as the Indonesia Traditional Music Festival (Festival Musik Tradisi Indonesia), Indonesia Tells Stories (Indonesia Bertutur), and the G20 Cultural Ministers Meeting. Objects of Advancement of Culture explained in Law Number 5 of 2017 are told from interesting perspectives, such as the traditional Sandeq boat of the Mandar of West Sulawesi, a traditional knowledge still preserved today. The Indonesian Textile features Ulap Doyo, beautiful hand-woven textiles of the Dayak Benuaq of East Kalimantan. What else? Want to know more? Flip through the pages of this magazine to discover.

Quoting Richard Schechner (2002), this world is no longer a book for us to read but a performance to involve in. That’s the delight of participating in culture as we are not (supposed to be) just spectators, but actors, as we define Indonesian culture. Wouldn’t the world be better off? Happy reading!

Editor in chief

2 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

2 INDONESIANA VOL. 10, 2021

VOLUME

Sampul depan:

2021 2 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15 2022 VOLUME

14

HILMAR FARID Director General of Culture Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology Repulic of Indonesia

Culture for Sustainable Living

Challenges facing our world today: pandemics, interstate and intrastate armed conflicts, the threat of terrorism and extremism, responsibility-sharing for refugees and displaced persons, and natural disasters. Resolving these serious challenges would require tremendous attention and energy. There is more than one way to solve all development problems. We often look for a silver bullet, a single solution for all issues, which only would create more problems than solve them. We should address development challenges in different geographical contexts by strengthening existing local potential instead of a panacea to implement anytime and anywhere. Addressing diverse issues would require the diversity of methods or, better yet, diversity as the method.

That way of thinking leads us to culture. Other cultures influence every culture in the world. Cultural diversity is not an obstacle to development; Cultural diversity forms the basis of sustainable development. Only by taking cultural diversity, culture, and context seriously can we establish regional harmony while maintaining national identity and simultaneously fostering a sense of togetherness that unites regional communities.

Culture knows no administrative boundaries because culture existed before the modern political structure and administrative boundary. The hybridization, borrowing, and adoption of cultural elements between groups across national borders is a historical fact. We also recognize the contemporary challenges and complexity of managing cultural diversity, such as climate change, migration, rapid population growth, food insecurity, land degradation, war, terror, conflict, and inequality. Culture and nature are complementary, inseparable, and interdependent, which are crucial to addressing those challenges. Creating an enabling environment is imperative to protect the diversity of cultural expressions. What we need today is the preservation of cultural heritage, conservation and sustainable use of natural resources, community participation, and the protection and promotion of cultural diversity and natural ecosystems that contribute to their well-being in both local and global contexts.

By utilizing the wealth of local potential in each country, there are examples of how endogenous resources stimulate sustainable development. The focus should be on strengthening the cultural ecosystem of society: safeguarding

traditional knowledge and practices and the surrounding natural environment that inspires them, creating democratic innovations with a touch of technology, and driving local economic growth through the development of utilization networks. To overcome social inequality, we need to strengthen the role of women and youths in initiatives to promote local cultures. Their pioneering work of local wisdom-based conservation and innovation will strengthen a healthy and fair knowledge production ecosystem and enhance equal access to local resources. In this respect, cultural diversity is our way of finding solutions to everyday problems.

I therefore warmly welcome the publication of Indonesiana Magazine Volume 15, published right after Indonesia successfully held the G20 Culture Ministers Meeting with the key message of “Culture for Sustainable Living.” I hope it will inspire the readers to cultivate the potential of local culture in seeking answers to today’s global challenges.

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 3 FOREWORD

TRADITIONAL

TRADITIONAL

4 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022 CONTENTS FOREWORD

WEAVEN

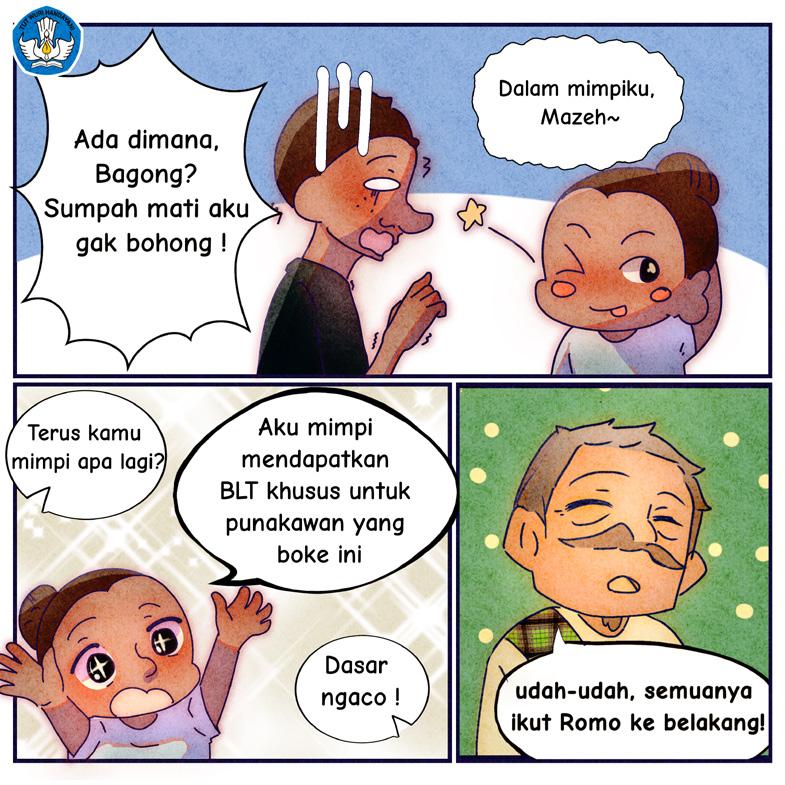

FEATURES CULTURAL EVENTS 1 Director for Culture Development and Ultilization, Directorate, General of Culture 2 Editors 48 Ulap Doyo Weaving The Wisdom of Dayak Benuaq Tribe 52 Sandeq Boat Knowledge Transmission and Character Education 56 NYOBENG The Thank Offering of Dayak Bidayuh 60 Revitalizing the North Maluku Local Language Ngom Ua Nage Ana Adi 6 Quo Vadis Acehnese Saman 12 One Pantun Two Nations 21 Indonesia Bertutur Captivating the Audience 16 The Culture of Kris, Simplified 26 Village-Based Cultural Advancement and Empowerment 30 Accumulating Cultural Actions for Sustainable Living 44 Komik Tradisi (Kepercayaan dan Masyarakat Adat) Dit. Kepercayaan terhadap Tuhan YME dan Masyarakat Adat COMICSTRIP INFOGRAPHIC 46 Nomenclature of Regional Offices for Cultural Preservation 3 Director General of Culture Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology Repulic of Indonesia 36 When Traditional Music Makes a Spectacle at Lake Toba 40 Promoting Objects of Advancement of Culture Collaboration between Local Government and Communities

KNOWLEDGE RITES LANGUAGES MAIN

WORLD HERITAGE

64 Updates from the Ombilin Coal Mining Heritage

VERNACULAR ARCHITETCURE

68 Rumah Tuo Kampai Nan Panjang Past Lessons for the Future

PERFORMING ART

72 Miss Tjitjih Approaching the 95 Anniversary of Sundanese Theatre th

TRADITIONAL CUISINE

76 A Sweet Taste of Kipo, a Bite of Memories

CULTURAL PROPERTY

80 Batanghari River The Veins of Civilization

CUSTOMARIES

84 Cisitu Customary Forest Sustainable Forest, Prosperous Community

HISTORY

88 Awaken the Dragon in Glodok Chinatown

MUSEUM

92 Using Wayang Beber to Spread Messages

PERSONAGE

96 Melati Suryodarmo: From Indonesia to the World

PORTRAITS GALLERY

102 Maluku Village Opening Ritual Celebrating Patriotism, Renewing Ourselves

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 5

ACEHNESE SAMAN Quo Vadis

6 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

MAIN FEATURES

The totality of dancers lift the spirits

Since the inscription of the Saman dance of Aceh on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) on 24 November 2011, the people of Indonesia and Acehnese have had high hopes. Around 400 participants from 137 countries attended the inscription announcement of the Saman dance of Aceh by the session of UNESCO in Nusa Dua, Bali. We consider the inscription a mandate, trust, and challenge.

When people see the live performance of the Saman dance, the dancers’ movement, harmony, accuracy, and speed amaze many. The people of Indonesia and Aceh, the birthplace of this “head-shaking” dance, highly valued the dance. Saman dance is everyone’s

favorite. People perform it from smallscale events at schools or villages to grand government ceremonies at the national level. The Saman dancers can dance on any occasion. They can perform at the opening of a formal or non-formal event, reception of guests, festivals, or even at the closing of any event. People favor Saman dance, which can perform regardless of time and place. However, the philosophical meaning of the dance has eroded.

When the Saman dance gained popularity at the national and international levels, especially after the Aceh peace process, fundamental problems unraveled. The origin of the Saman dance, the composition of the movements, and the lyrics of the poems (songs) in the dance remain unanswerable questions. Instead of speaking of its

development to date, people are debating the history of the Saman dance using their respective references to strengthen their arguments.

Questioning the Origin

We hear Sheikh Saman started and introduced the Saman dance, but the detailed biography of this figure is unknown. Several sources say—although there must be evidence from previous studies—that Syekh Saman came to Aceh and spread the teachings of his tariqa with poetry and zikr movements. However, various contemporary sources, both books and online media, only mention the name of Syekh Saman came from Medina to Aceh in the 18th century AD. That is it with no more information.

Snouck Hurgronje mentions in his book “De Atjehers” that Saman originates from outside traditions that permeate the dance traditions of the Acehnese people. We believe that the Samaniyah

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 7

Photo courtesy of Rizky Fadly

(sammaniyyah) tariqa, having roots in Madinah, adopted and developed the Saman dance. Indonesian Muslims subsequently favored the religious tradition. However, there is no information on how the Saman dance spread to remote areas and integrated with the highland culture from the Saman or Samaniyah tariqa place of origin in the coastal region of Aceh.

It is also worth noting that we regard the Samaniyah tariqa as the creator of the Saman dance. Sheikh Muhammad

bin Abdul Karim al-Samani al-Hasani al-Madani (1718-1775) was the initiator of the dance before it spread to several regions, including Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, and Indonesia. Then, the muktarabah tariqa, particularly the Samaniyah tariqa, flourished in Aceh.

Although there are no comprehensive research on how the tariqa spread in Aceh, we found out about prominent figures known as muridin (followers) and propagators of the Saman tariqa, such as Sheikh Muhammad Saman, a disciple of

Sheikh Marhaban and Muhammad Saleh. The prominent figures and Teungku Chik Di Tiro are all contemporaries during the war fights between the people of Aceh and the Dutch; Syekh Saman is also related to Commander Chik Di Tiro.

So, is it true that propagators of the Samaniyah tariqa are the creator of the Saman dance? Do Sheikh Saman and other tariqa propagators conceive the idea of the Saman dance, or is it one creation of the Samaniyah tariqa’s followers? We should add that these

8 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Saman is different from Ratoh Jaroe

figures lived and came from the northern coastal area of Aceh, not from the highlands and interior regions.

While we have not resolved the historical issues on the origin and spread of the Saman dance in Aceh, other problems arise, such as the right to claim and status of the Saman dance that is said to belong to a particular region in Aceh. Criticism emerged from other parties who thought they were more entitled to the ownership rights of the Saman dance. Problems arose when the Saman dance

spread across regions throughout Aceh, penetrating the ethnic groups and native tribes of Aceh. Saman dance eventually spread throughout Aceh, although each ethnic group wondered about the originality and authenticity of the dance. From the new variation, poetry, or lyric to the number of dancers becomes a “classic” issue when we talk about the Saman dance performance until today.

The debate on the Saman dance also extends to the innovative performances of Saman at the local, national, and

international stages. For example, we should limit the number of dancers, as it shouldn’t be a mass dance. Some artists consider the mass Saman dance a breakthrough, a contemporary innovation. However, the “conservative” group thinks this innovation has diverged from the rules and pillars of the Saman dance.

Female Saman Dancer

The “hot” and engaging issue about Saman dance is the subject of female dancers. This discussion interests artists,

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 9 Image source: https://www.shutterstock.com/ image-photo/aceh-indonesia-august-13-2017-10001-1658244697

10 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Saman mencari maestro -

observers, and scholars, which has become a topic of debate, especially when we juxtapose our discussions and writings with Islamic law on the code of behavior in man-woman interactions, except for girls who have not yet hit puberty.

The dance movements of the female dancers no longer follow the standard Saman. Therefore, some artists call it the ratoeh jaroe (hand movement) dance, a new term in Acehnese dance because of the dominance of women in dance performances. The goal is not to compete and argue but to strengthen the art of this dance of rapid movements. So far, the artists agree only men perform the Saman dance, so if women perform a similar dance, the names will be different, including the ratoeh jaroe

Searching for a Maestro

Another issue to solve concerns the “syekh” role or the maestro of the Saman dance and the transmission of the maestro’s knowledge through a sustainable heritage education program. Maestro is the narrator or storyteller of Saman who performs on national and international stages. The maestro must understand and tell the meaning and philosophical values of the Saman dance and its lyrics, which will affect the strengthening of Saman education in various regions. However, the maestro is almost non-existent nowadays.

Two peas in a pod, the Saman dance education, and its development program is the responsibility of the Aceh government, especially the district/ city offices in charge of education and culture, although in vain. There is no local content curriculum for the Saman dance in Aceh schools. It is strange and ironic. We must safeguard the Saman dance as an intangible cultural heritage for humanity from becoming extinct, which encourages other people to promote other forms of dance arts from dying and becoming obsolete.

Now, Saman dance belongs to the world. Therefore, let the people of Aceh safeguard the collective memories of the Saman. Every 24 November, following the inscription of the Saman dance on UNESCO’s Lists of ICH, we should continue celebrating. The government and people of Aceh need to revive the philosophical values of the Saman dance, such as speed, accuracy, cohesiveness, togetherness, respect, tolerance, and cooperation, which are the characteristics of the Acehnese.

(Hermansyah, UIN Ar-Raniry academic and Acehnese philologist)

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 11 Getting on and being in harmony

Photo courtesy of Rizky Fadly

Two Nations One Pantun

When we talk about global culture, we should tear down all primordial barriers. According to the United Nations, the world’s population has reached 8 billion, and in the 21st century there is almost no culture in a place that does not intertwine with other cultures. When we discuss Malay culture, for example, we will look at groups of people who inhabit the Malay Peninsula, eastern Sumatra, southern Thailand, the southern coast of Burma, and coastal Borneo including Brunei, West Kalimantan, Sarawak and Sabah.

The ancient Malays have migrated and spread to the archipelago since 2,500 BC and the Malay identity has transformed into Indonesian Malay, Malaysian Malay, and others, as stated by lecturer and researcher of Malay dance, Julianti Parani, in Indonesian Performing Arts: A Political Culture (2011). There is a cultural origin that once unified and then developed into the identity of each country. In the past, Malay had migrated and assimilated across the archipelago and Southeast Asia and as far as to Taiwan, Zanzibar and Australia.

12 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

MAIN FEATURES

When we discuss pantun, more specifically Malay pantun, it is not possible to associate this cultural heritage to Indonesia only. In fact, the Malayness in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei can be said to be more apparent since Malays are understood as a race with wide ethnicity variables (Islamic religion, customs and language), in contrast to Malays in Indonesia which only refers to one ethnicity. Therefore, the joint nomination by Indonesia and Malaysia for inscription of pantun onto the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) made sense.

Proposing pantun to UNESCO for its inscription on the Representative List of the ICH of Humanity on 17 December 2020 at the ICH Intergovernmental Committee sessions in France and Jamaica was quite long. Looking back, the Association of Oral Traditions (ATL) together with the Malay Traditional Institute (LAM) submitted pantun to the Ministry of Education and Culture through the Directorate General of Culture in 2016, and on 7-29 September 2016 a preliminary meeting was held to propose pantun as ICH to UNESCO. After the presentation of the academic text on 3 November 2016, feedback was received, among which there was no explanation to anticipate possible claims by Malaysia which also uses the Malay language. In response to this feedback, proposing pantun as a multinational nomination with other Malay countries was considered more appropriate. However, since Singapore,

Brunei Darussalam and Thailand were apparently not ready, the joint nomination for pantun was proposed only by Indonesia and Malaysia.

The decision to jointly nominate pantun was met with some rejection, because Indonesia felt it had more rights. However, the facts show pantun is still used by the Malay, the Bajau, the Ida’an, the Kedayan, and the Baba Nyonya communities in Malaysia. As for Indonesia, pantun is not only known in Riau Province and the Riau Islands, but has spread to Lampung through the kias tradition, also in Minangkabau society, on to Betawi through palang pintu and rancak performances and to South Kalimantan, Manado and Ambon.

In its development, the joint nomination for ICH has become a more convenient and reasonable choice, for its technical and ideological reasons. According to the Chairperson of ATL, Pudentia MPSS,

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 13

Reciprocating Pantun on the day of betrothal

Photo courtesy of Fatma Adnan

UNESCO also encourages multinational nomination by two or more countries that have intertwined cultural histories. Besides pantun, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Thailand recently nominated kebaya to UNESCO ICH lists.

The Allusions in Pantun

Pantun as we know today is an oral tradition passed down from generation to generation in Malay society. British linguist and orientalist, William Marsden, in his book The History of Sumatra (1783), states that the characteristic of Malay pantun is highly allusive, and the allusions are in fact the spirit of this oral tradition. Meanwhile, linguist Charles Adrian van Opuijsen said that pantun has the same position as the early poetry genre, because pantun was also present in the early life of the Indonesian people. According to Malay language expert, Richard James Wilkinson, pantun uses hidden words, which rhyme, or pattern of the sounds is suggestive to the listener.

Pantun was presented in religioussacred events in the past. Pantun was then developed and used in communal spaces such as in rituals and traditional ceremonies, which, together with gurindam and petatah-petitih, were able to enliven traditional events and became

the stage for mastery of the figurative language of the Malay people until now. Furthermore, pantun also entered the popular area, in the form of aesthetic expressions such as song lyrics, and expression of feelings in everyday interactions between individuals.

In the academic text of pantun, which was submitted to UNESCO, some examples on the use of pantun in daily life of the Riau community were included. For example, the traditional ceremony of babalian (from Rantau Kuantan), bulian (from Talang Mamak), belian (from Petalangan), bedewo or mambang dewo-dewo (from Bonai), tu-un jin or buang lancang (from Penipahan), buang talam (from Bengkalis), bedikei (from Sakai), dan upah-upah (from Rokan).

Pantun in communal events is used in economic activities such as menggetah kuaran (in the Kuantan and Kampar areas), batobo (in Kampar, Rantau Kuantan, and Tiga Lorong), menumbai, mengayun enau, timang padi, and catching fish. Pantun is also used in life cycle ceremonies and performing arts. We are familiar with zapin (from coastal and inland areas), gambus batandang (from Talang Mamak), kayat, randai (from Rantau Kuantan), koba (from Rokan), timang onduo (from Rokan/Bonai), nandung (from Indragiri), badondong and basiacuong (from Kampar), gaden (from Bengkalis), olang-olang (from Sakai), and many others.

Researcher of pantun, Rendra Setyadiharja quoting a pantun by Haji Ibrahim in his book Old Malay Pantuns (1877) which contains metaphors or symbolic meanings (Media Indonesia, 20/22/2022):

Buah berembang hanyut ke lubuk

Anak undan meniti batang

Kalbu abang terlalu mabuk

Menentang bulan di pagar Bintang

Berembang fruit drifting to the bottom

Undan bird walks through the trunk

Love bug struck my heart

Against the moon challenged by stars

14 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

The word moon represents a time or atmosphere and has meanings related to destiny and the future and can also symbolize a romantic atmosphere between two people. This pantun may tell about a young man who has romantic feelings but cannot show his feelings, marked by a love bug that struck my heart.

We can see that sampiran (foreshadowing verses) in pantun may not just be a decorative word to sweeten the rhymes, but also plays a role in conveying the meaning of the rhyme. Sampiran may be used to describe local wisdom, and from the sampiran alone we can find out

how events, history, culture, traditions or customs took place. In essence, pantun upholds various lifeways of the Malay people.

This is the reason why when we hear the type of “pantun for fruits” (pantun with the names of the fruits), it feels like the meaning of the pantun becomes distorted, for as long as it rhymes. For example, “Mango, pomegranate, if my sister is miserable, even my brother will suffer,” or “Pineapple, guava, my heart is boiled seeing her being seduced.” If you look at the positive side, “pantun with fruit names” can be a way of learning, yet it’s not easy to produce words with attractive diction.

When you think about it, it is not easy to create pantun, let alone do it spontaneously. It is hard. Therefore, a continuous learning process is needed, one of which is by safeguarding traditional ceremonies, life cycle celebrations, and other performing arts by practicing pantun. The inscription of pantun on UNESCO ICH list, jointly nominated by Indonesia and Malaysia, should be able to make the safeguarding of pantun easier, because it shall be done by “two parties”. One pantun belongs to two countries.

(Susi Ivvaty, Indonesiana).

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 15

Pantun buka pintu (welcoming remarks) from representatives of the groom and bride families

Photo courtesy of Fatma Adnan

Delivering the groom with Pantun

Delivering pantun at the handover ceremony of ICH-UNESCO certificate of Pantun

Photo courtesy of Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization

VOL. 15, 2022 I 15

MAIN FEATURES

Kris, The Culture Of Simplified 16 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

AKris (keris) is originally a dagger used as a thrusting or stabbing weapon, which comprises two main parts, the blade (bilah) and the blade base (ganja) that represent the lingga and the yoni, symbols associated with fertility, eternal life, and strength.

Kris has a beautiful, asymmetrical (straight or wavy (luk)) shape, forged out of two, three, or more metals, according to Bambang Hasrinuksmo in Ensiklopedi Keris (2008) and Haryono Guritno in Keris Jawa Antara Mistik dan Nalar (2006). But eventually, Kris transcends its mere technomical function as a weapon into emphasizing its philosophical values and life philosophy of Indonesian people. In Indonesian culture, Kris is present in all milestones in life, from birth to death.

Kris is a means to remind and keep us mindful of our creator (God Almighty). Therefore, Kris often becomes an essential component in religious rituals and ceremonies.

Kris, stemming from Indonesian culture and local genius, originated in Java in the 8th century and subsequently spread to nearly the entire archipelago, as mentioned by Mubirman in his book Keris Senjata Pusaka (1980) and by Hamzuri in Keris (1993). According to Kris experts, such as Bambang Hasrinukso, Haryono Guritno, and Darmosugito, Kris has even spread to Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei Darussalam, Thailand, Myanmar, and the Philippines. Kris spreads through trades,

wars, marriages, and political relations, giving birth to diverse forms, patterns, and styles that reflect the characteristics of the host community, enriching the Kris world’s repertoire.

Kris culture today

Kris is a cultural heritage under the domain of traditional craftsmanship. Not only about making the blade, but Kris-making is also about making the sheath, the hilt, pendok, selud, singep, blawong, and Kris’s other sculptured or chiseled features (perabot) as well. We can find Kris makers evenly spread over various regions in Indonesia. Some time ago, Madura, Surakarta, and Yogyakarta were the centers of Kris-making. Today, Kris-making in Java is also expanding to Surabaya, Malang, Tulungagung, Madiun, Magetan, Karanganyar, Kendal, Banyumas, Jepara, Kota Gede, Bantul, Gunung Kidul, Bandung, and Bogor. Kris making also spreads to Sopeng, Bone, and Mandar (Sulawesi), later to Tabanan, Klungkung, Karangasem, Gianyar, and Badung (Bali), as well as Central Lombok, West Lombok, and East Lombok (Lombok). In Kalimantan, we can find production centers mainly in East Kalimantan and West Kalimantan. Also, we can meet prominent artisans of Kris in West Sumatra, Riau, Palembang, and Jambi.

Kris-making affects the growth of traditional ceremonies in which Kris

continues to be present. Life cycle ceremonies such as seven months of pregnancy (mitoni), earth stepping (tedak siten), circumcision, marriage, village alms, communal feast, to cultural carnivals requiring a Kris. What’s interesting today, the use of Kris in traditional and modern clothing is becoming increasingly popular.

The government collaborates with the community and stakeholders proportionally to accomplish the various action plans in the Kris nomination proposal to UNESCO, referring to the strategic steps in Law no. 5 of 2017 on the Advancement of Culture.

These strategic steps include:

1. The government established the Indonesian National Kris Secretariat (SNKI) as a forum for Indonesia’s Kris enthusiasts through the MoEC’s Research and Development Center after the inscription of Kris on UNESCO’s List. Today, SNKI has grown into a sizeable organization with over 200 arts and culture studios/ associations as members in almost all parts of Indonesia. SNKI is engaged in various activities, such as research, advocacy, publication, and education. SNKI is also involved in reports on the conservation of Kris culture in international fora and promotes Kris abroad.

Image source: https://www.freepik.com/premium-photo/asian-blacksmith-forging-molten-metal-with-hammer-make-keris VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 17

Forged in fire

2. The government established a Kris study program at the Indonesian Institute of the Arts Surakarta (ISI Surakarta) as a strategic step towards “krisology” through formal education. The Kris study program is a government mandate and has been part of the Indonesian Institute of the Arts Surakarta since 2012 and has given birth to many qualified 4-year diploma graduates in Kris. The Kris Study Program Alumni have high expertise in the making, conserving, and curating of traditional Indonesian Kris and weapons.

3. The government’s MoECRT established the Museum Keris Nusantara in Surakarta. The government equips the museum with an extensive collection of Kris from various regions of Indonesia, an audiovisual room, a forging workshop, and a conservation room.

4. Since 2021, the Directorate of Cultural Human Resource and Cultural Institutions Empowerment and SNKI have been partners. The collaboration creates a standard for the Kris profession and meets the demand for skilled professionals. There are 29 schemes in the Kris field, which refer to aspects of Kris-making, curatorial, and conservation.

5. Exhibitions, exchanges, and workshops as educational and promotional media have a good impact on the growth of the creative economy in the Kris field because of the collaboration between academia, studios/associations, museums, and the government. ISI Surakarta, Jogjakarta International Heritage

Festival (JIHF) started the Kris Festival, Heritage Carnival in Ponorogo Regency, Kyai Tengoro Kris Carnival (Surakarta Keris Museum), and Tulungagung Kris Fest.

Challenges

Traditional cultural works are full of meaning and value, which require creative transformation to meet today’s challenges. However, we must attempt to preserve the essence and values so that the cultural heritage revives in cultural advancement. Increasingly advanced modern technology has put the world in our hands. All knowledge and information are in the gadget. The number one challenge is passing it on to the millennial generation. We have passed the Kris culture down from generation to generation for hundreds of years (from the 8th century). Because of the strong influence of foreign culture and changes in lifestyle and needs in the modern era, everything has become practical, fast, and instant. So, we need to transmit the wisdom of the Kris cultural heritage in a way the millennial generation understands. The second challenge is the rise of Kris as a medium of fraud. Limited education, lack of qualified curators, and many distortions to Kris’s wisdom often place Kris as a fraudulent medium. People rarely understand supernatural beliefs and practices involving mysticism, spirituality, and magic. It makes them victims of

fraud. Some people believe in spiritual things, but they need to be equipped with an in-depth understanding and position the knowledge proportionally. Apart from that, the rise of newly made Krises that give the impression of being oldfashioned has become part of the trading commodity, which makes people reluctant to own a Kris. The third challenge is managing the Kris market share as a creative economy. A market share that extends to foreign countries provides promising economic opportunities. Unfortunately, the management is not good, so there is often overlap. The proliferation of monopolies by several parties has further widened the gap among those actively involved in Kris culture. The fourth challenge is weak

curatorial.

Qualified curatorial is falling behind the growth of Kris’s culture. The impact is that it often triggers

18 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Photo courtesy of Basuki Teguh Yuwono

disputes and has the potential for biased understanding. Therefore, we urgently require curatorial certification to have competent curators.

The fifth challenge is the uneven distribution of the Kris ecosystem preservation. Based on observation, we noticed uneven distribution of Kris’s growth in its ecosystem. Because we have not managed various fields relevant to Kris properly, they will become a weak link and threaten Kris’s cultural sustainability. We also lack, for example, knowledge transmission on panjak or forging, wood materials for the hilt, makers of chiseled features on Kris,

conservators, and curators. Other than the customs and clothing where we present the significance of the Kris, we also need to preserve the spirit and values of Kris rather than treat it as a mere decorative object. The key to a favored cultural heritage is a well-preserved ecosystem, simplified core values, and creativity that stems from its roots. We urgently need a proportional divide of responsibilities among the government, community, and all stakeholders. Our heritage, our nation’s glory.

(Basuki Teguh Yuwono, Head of Surakarta Keris Museum and Lecturer at ISI Surakarta)

Purify to preserve Some of the museum Kris collections

(Basuki Teguh Yuwono, Head of Surakarta Keris Museum and Lecturer at ISI Surakarta)

Purify to preserve Some of the museum Kris collections

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 19

Photo courtesy of Syefri Luwis

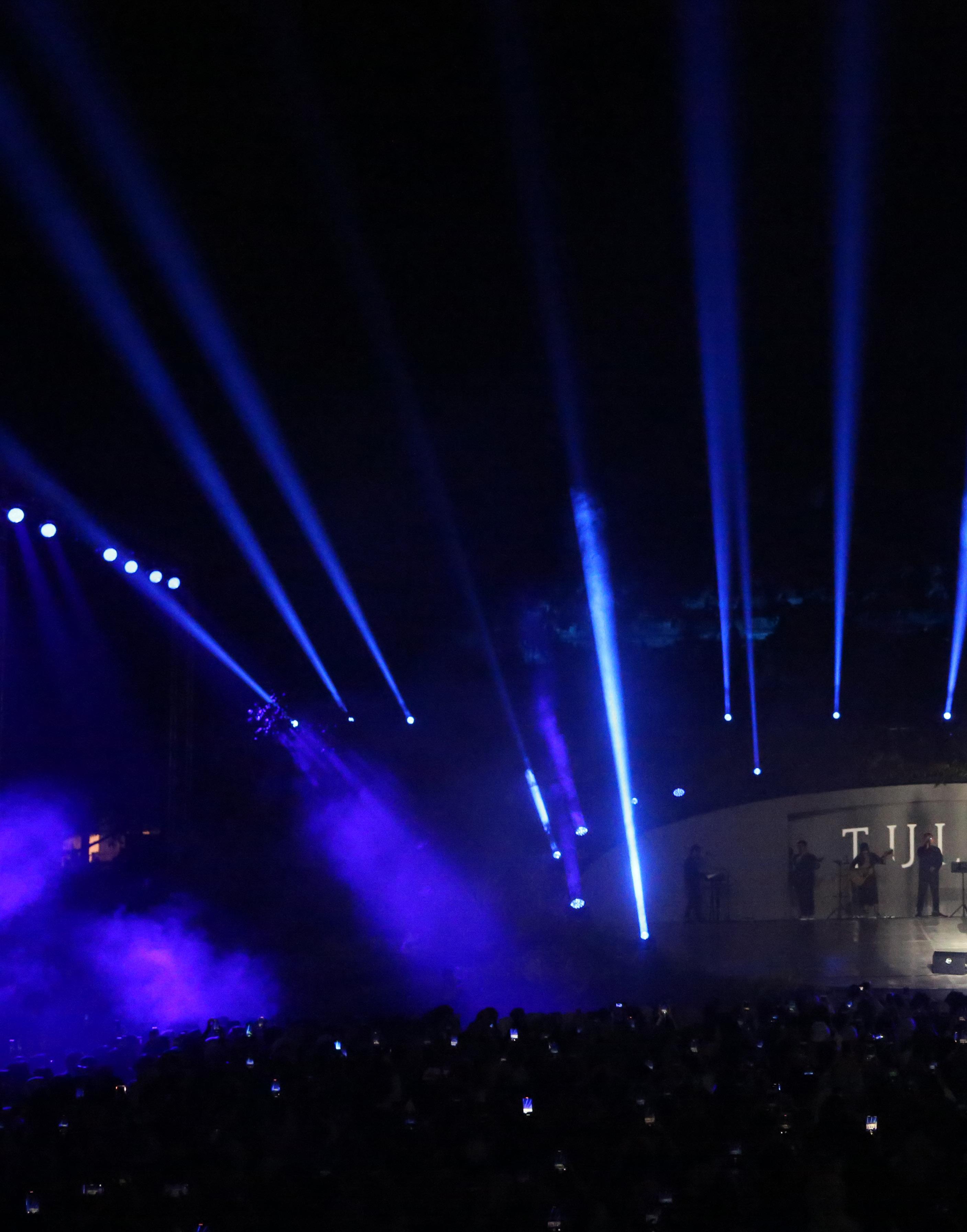

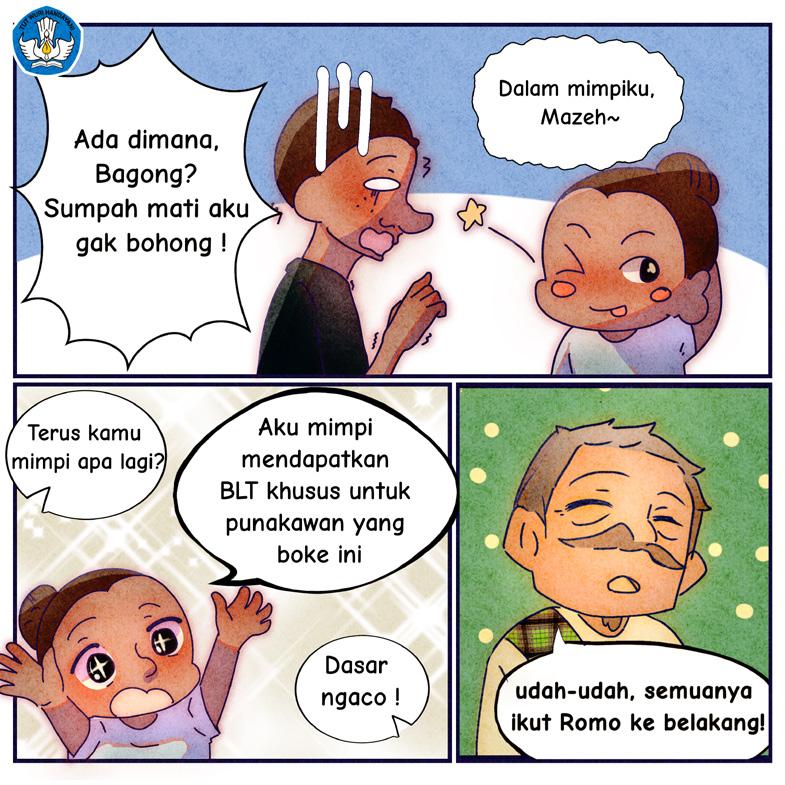

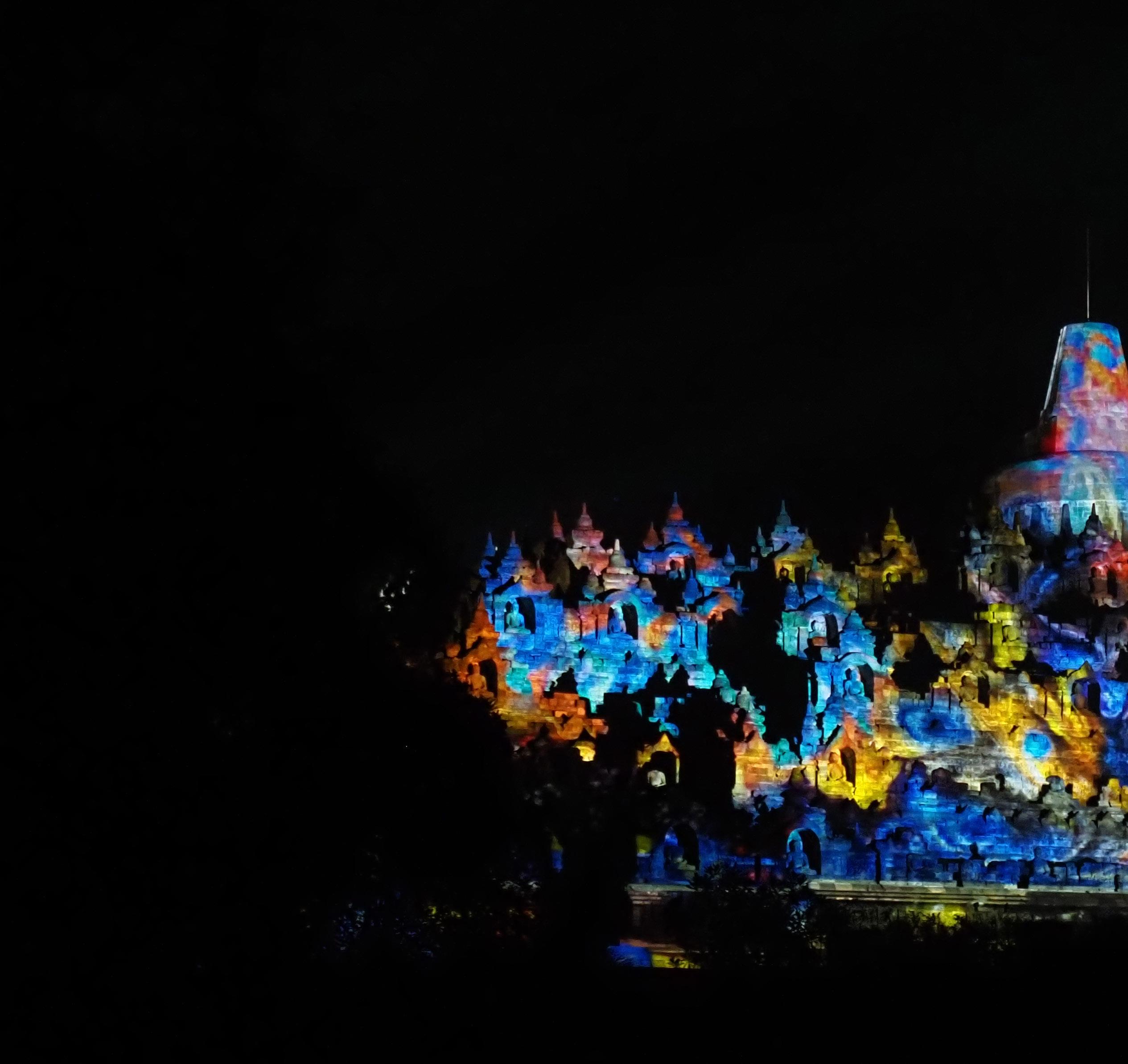

Indonesia Bertutur Captivating the Audience

The ‘Indonesia Bertutur-InTur’ (Indonesia Tells Stories) Festival is one of the side events of G20 Culture Ministers Meeting which was held on 7-11 September 2022 at the Borobudur Temple Compound in Magelang, Central Java. Indonesia Bertutur carried the theme “Experience the Past, Growing the Future”, with the hope that people could interpret past events or history in new ways that are relevant to the present. The main objective of Indonesia Bertutur Festival was to promote a sustainable culture through activities that are educational, inspirational and full of experiences. Many artists from Indonesia and abroad participated and presented their works through performing arts, films, and new media arts within the context of cultural heritage narratives that are adapted to the current context.

CULTURAL EVENTS

Beberapa koleksi

20 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

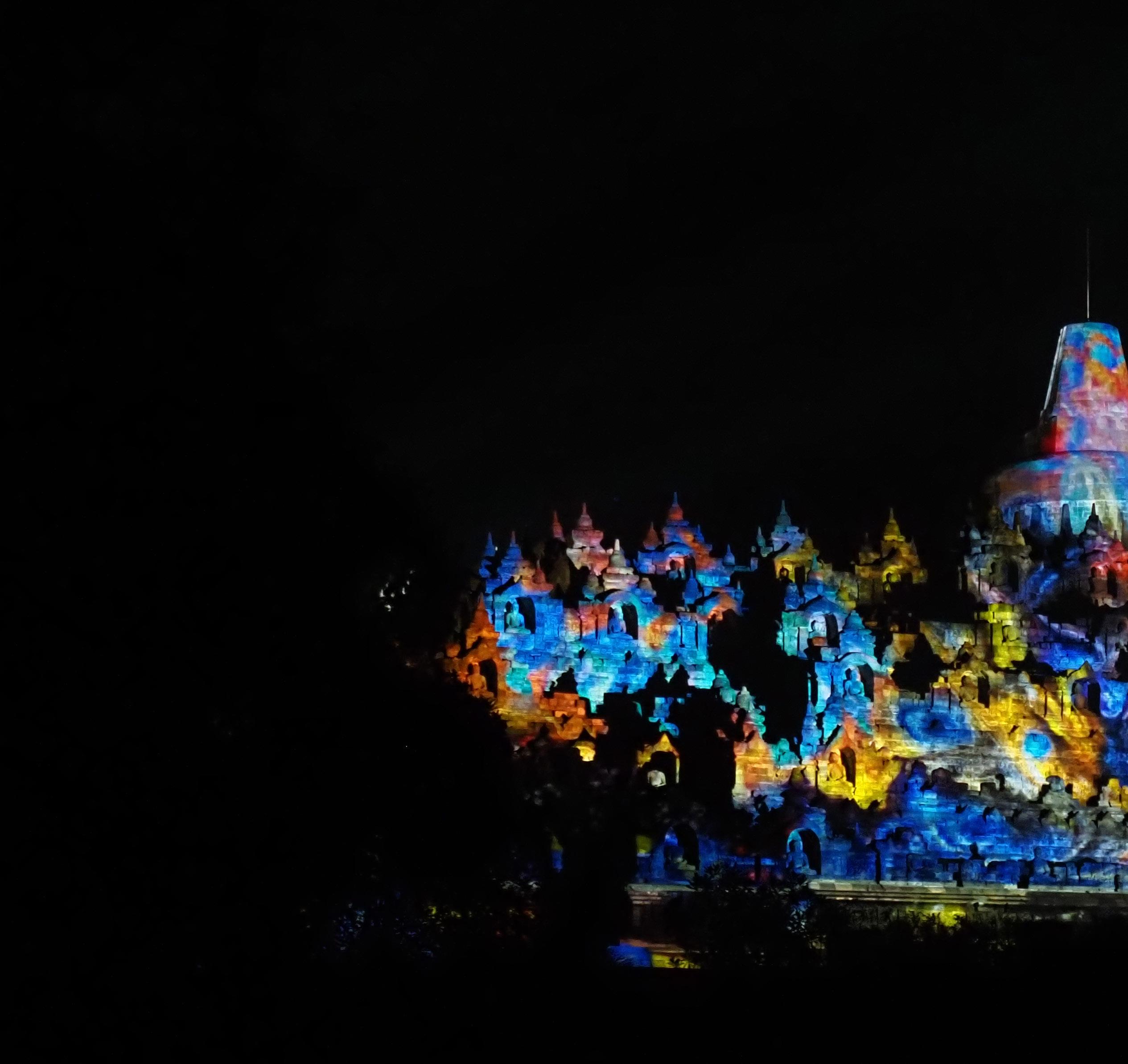

This festival was held across four art spaces around Borobudur Temple Compound, namely Virama, Anarta, Kiranamaya, and Visaraloka. At the Virama evening stage, music, dance, and storytelling were performed. There was also a culinary area at Virama that served a variety of traditional foods such as meatballs, dumplings, spring rolls, chicken noodles and herbs. The Anarta or the Lumbini stage featured a variety of contemporary music, dance and theater performances by groups that

have carried out a long experimental and collaborative process using modern technology in their work.

At Kiranamaya, there were video mapping and light installation works from various artists using interactive and architectural lighting technology. Visitors could get a special lighting experience at Borobudur at night similar to the light festival which can be enjoyed at the Aksobya stage. The Layarambha at Kiranamaya presented various kinds of dance-based feature

films and short films by artists from various countries, including Indonesia. Lastly, the Visaraloka stage featured an expanded media art exhibition.

The Art Festival

On the first day of Indonesia Bertutur, the atmosphere immediately became lively since the opening of the Visaraloka expanded media exhibition featuring epic works by expanded media and performing art artists, such as the painting exhibition at Eloprogo Art House

museum keris -

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 21

The dances performed at the Indonesia Bertutur Festival

by Sony Santosa and art installation by Gilang Anom. In addition to Visaraloka, there were four other locations for expanded media exhibitions, namely the Eloprogo Art House, Limanjawi Art House, H. Hidayat Museum, and Apel Watoe Art Gallery. One of the highlights of the exhibition was the work of Mella Jaarsma and Agus Ongge, which was exhibited at the H. Hidayat Museum, an installation of clothing made of bark cloth which was demonstrated by several models. It was as if we were transported to the time of ancient humans, especially since on the other side of this installation there was a video by Lisa Reihana entitled “In Pursuit

of Venus” which showcased how early humans lived at that time.

Indonesia Bertutur was inaugurated by the Director General of Culture of the Ministry of Education and Culture, Hilmar Farid, accompanied by the Director of Film, Music and Media, Ahmad Mahendra, and the Artistic Director of Indonesia Bertutur Melati Suryodarmo at the Lumbini Borobudur Temple stage area. The inauguration ceremony attracted the most attention. The Lumbini stage itself was already attractive with its white semi-circular shape decorated with plants on both sides of the stage and has

the majestic towering Borobudur Temple in the background. It was magnificent. Although it rained during the opening night, the audiences stayed to watch the art performance until the end.

The inauguration of Indonesia Bertutur started with a slametan ceremony with the participation of the community members from the Borobudur area and the cultural actors involved. This mass traditional slametan ceremony involved residents from 20 villages in the Borobudur District and included a mass mountain carnival and black mask dance performed at the Borobudur Temple courtyard. The

22 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

The projection mapping artwork on Borobudur Temple by the artists

inauguration ceremony at the Lumbini stage began with the performance of the soreng dance, a traditional dance of Magelang. The dancers were full of expression and energy, the movement of their feet and hands symbolizes tenacity as life fighters from the slopes of the mountains. The performance of the black mask dance performed by the Lima Gunung Community closed the inauguration event.

The number of visitors increased in the Borobudur Temple area on the second day. The shows and performances were very diverse. There were: fairy tales

storytelling with Kak Aio/Ariyo Zidni (Founder of Ayo Dongeng Indonesia), Kak BudiBaikBudi – a storyteller who is also a ventriloquist, and Kak Hendra Hensem who brought humor in his storytelling; various forms of dance from local cultural art groups; and the performance from singers Ardhito Pramono and Peni Candrarini who created an uproar in the evening stage area, making the audience immersed in the atmosphere of the selected songs. No less exciting, the Layarambha at Kiranamaya featured a film discussion with Garin Nugroho, Razan Wirjosandjojo, Iphul Ashyari, and Iin Ainar Lawide followed by the

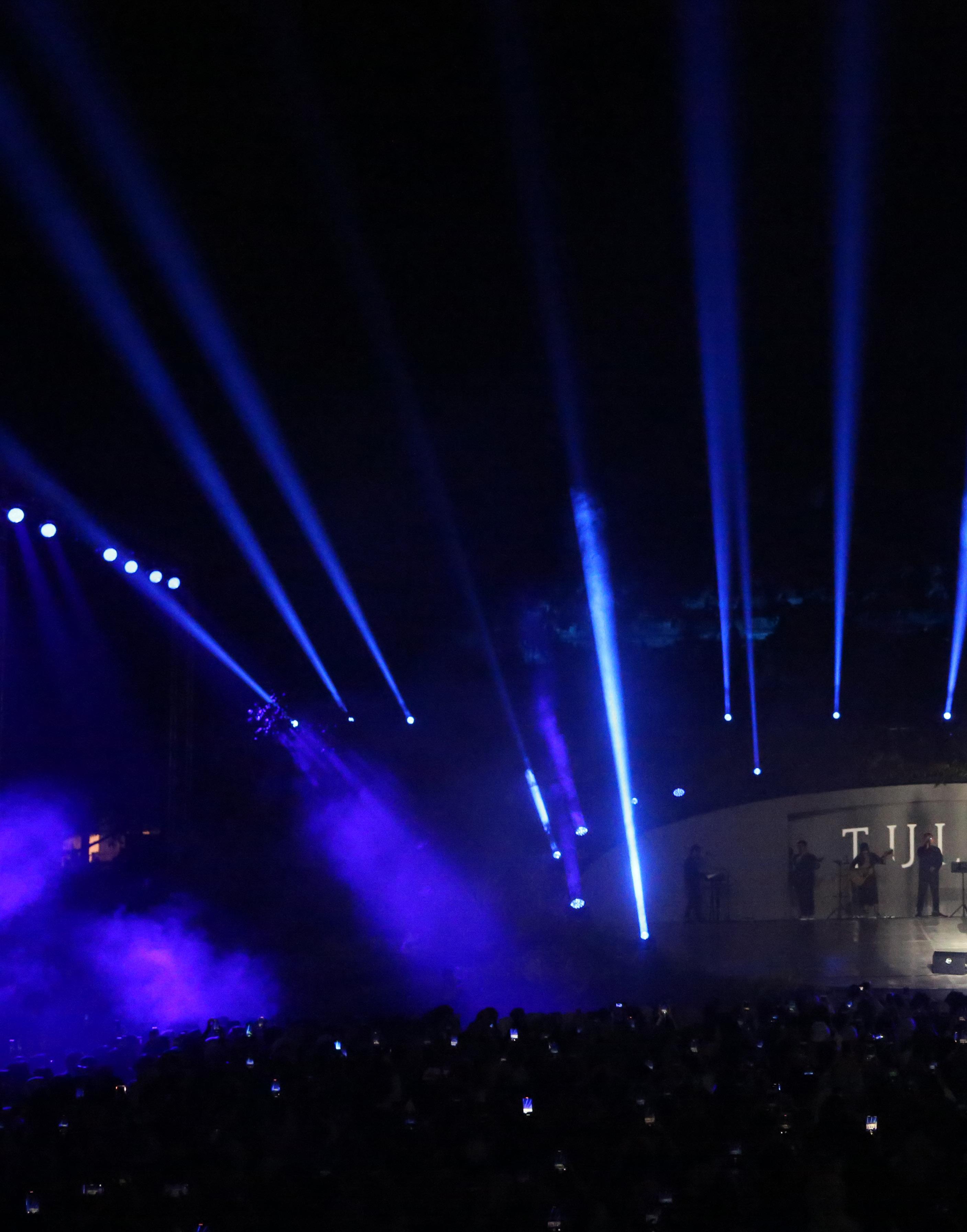

screening of the films “Anerca, Breath of Life”, “Lucy” and “Touching the Skin of Eeriness.” Various films were screened at Layarambha in the following days. The performance from singer Tulus was the most awaited performance which captivated some 7,000 audiences who waited patiently in the midst of a magical atmosphere in front of the stage which was adorned by colored lighting that made the atmosphere even more magnificent.

The Borobudur Temple in the background was highlighted with video mapping by artists, such as Rampages

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 23

Production x Toopfire which featured projected mapping based on Indonesian traditional cultural stories. The content of the story is based on ancient spirituality, traditional knowledge, and symbols of national identity, depicting a joyful world of light and shadow with bright colors and vivid images. It includes elements of Balinese dance, wayang puppet theater, batik, and other forms of living expression of Indonesian traditions and knowledge. The whole story ended with the climax of a flickering effect that was presented in a modern way to represent past culture and future heritage.

The Indonesia Bertutur Festival 2022 with the theme “Experiencing the Past, Growing the Future”, showcased video

mapping from Vulture Studio which tells a story about the magnificent civilization in Trowulan, East Java, of which development was not far from the influence of the Majapahit Kingdom. The theme of “experiencing the past” could also be felt in the performance by Studio Gambar Gerak who presented the cultural heritage of Gunung Kawi at Banjar Panaka, Tampaksiring Village, Gianyar Regency, Bali. Motionhouse Indonesia presented the legend of the Kutai Kingdom in East Kalimantan.

The Indonesia Bertutur Festival 2022 continued to be packed with visitors in the following days even though the weather was less friendly. Audiences would not want to miss the performances

from singer Letto with his romantic songs, as well as Om Wawes and Paksi Band with their keroncong-dangdut-campursari songs. Theatrical performances were also no less interesting. The Prehistoric Body Theater presented the play “A Song for Sangiran 17”. There were also theatrical performances by Fitri Setyaningsih, Mila Rosinta, Choy Ka Fai - Postcolonial Spirit, Senyawa, and Teater Garasi.

The five-day Indonesian Bertutur Festival 2022 has captivated audiences. Audience also got valuable experience and learned that past history can be displayed in modern format. This is a form of cultural education in a fun and contemporary format.

24 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

(Irnie Wanda, Directorate of Films, Music and Media).

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 25

Children eagerly watching InTur’s storytelling

Photo courtesy of Irnie Wanda

Vadvancement program is one of the priority programs of the Directorate General of Culture. The program aims to revive villages as the wellspring of livelihood, cultural commons, and the cradle of the cultural ecosystem. Village communities make up the subject of development rather than the object.

We designed the village-based cultural advancement program to respond to the challenges of globalization, which has turned rural villages into urban areas and caused rural communities to lose their identity.

Village-Based Cultural Advancement and Empowerment

Measures of development success that only focus on economic growth have eroded the network of mutual help among villagers and the local wisdom that grows from village community practices, creating new problems such as environmental degradation and social inequality.

To overcome this adverse impact, the government has started the villagebased cultural advancement program to develop the village based on village potential as the primary capital for a more comprehensive development than just economic development. In this way, we hope that there will be endogenous growth that comes from the village’s potential.

CULTURAL EVENTS

26 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Capturing People’s Imagination

Throughout history, the village has played a role as the melting pot of cultural interactions among the people of Indonesia and has kept the memory of the social life values. We have passed down the values for generations. The village is the smallest government unit and is the cradle of Indonesian cultural identity.

The village has enormous potential in terms of natural, human, tangible, and intangible culture, and even historical potential that can develop the rural community according to the imagination of its people about the village’s future.

Villagers’ imagination is a reliable guide for contextual development. Villagers have more right to talk about the future of their village as they directly experience the concrete struggles of rural life.

How do the villagers want their village to develop into what they envision? How can local businesses work together to make it happen? That is the starting point for endogenous development.

Through the villagers’ imagination, all cultural entities in the village are involved, from children to the elderly, both women and men from

various work backgrounds. Inclusive in it are people with disabilities and other vulnerable persons.

Based on the villagers’ imagination, we executed our village-based cultural advancement in 3 stages. The first stage is the identification of the culturalpotential stage, the second is the development stage, and the third is the utilization stage.

Implementing the whole process is based on recognizing the resources owned by the villagers. Thus, the three stages always uphold the principles of social inclusion, equality, independence, sustainability, practicality, and participation.

The Nation’s Cultural Commons

Sometimes we don’t realize that we have great potential. The same goes for villages. In the identification stage,

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 27

Photo courtesy of Radian B. Sena

we invite the community to rediscover and recognize their cultural heritage, the tangible and intangible, and the history of the rural village and the natural environment. The identification process also mapped community groups that support the sustainability of these various cultural practices.

We expect the participatory mapping concept to capture the village’s potential and existing problems. In addition, this stage also maps out the community’s expectations about the future of their rural community. Subsequently, we created a joint dialogue to plan the development of all potentials through an action plan.

The second stage of the program is the development stage. At this stage, we developed the culture potential map according to the Law on the Advancement of Culture, among others, an assessment of the possibility of cultural innovation. We then carried out diversity enrichment, efforts to encourage dialogue and interaction with people of other cultures.

The development of this potential aims to solve various problems in the village through cultural means, such as the solution to the problem of food security through using traditional, environmentally friendly agricultural methods and local rice as a genetic resource. Villagers with all elements in the village community work together through various activities. This effort aims to get social agreements in formulating an action plan for cultural development through village gatherings, village discussion forums, organizing joint cultural seminars, participatory maps’ alignment, and deepening understanding of the ecosystem of cultural potentials.

The third stage is the utilization stage, which aims to increase cultural resilience, intercultural collaboration, community welfare, and village character development. At this stage, villagers can identify and select the program’s strategic partners, plan program financing, and form a catalyst organization.

We then synchronized the final action plan with the results of the village-level Deliberation of Development Planning (MUSRENBANG) to get the right to use the village fund. The publication of

village potentials comes after this step, such as through films and books, as well as reintroducing village culture to children through local content education, activating art studios as a cultural space for villagers, and so on.

Villages of a Distinct Local Character

Village-based cultural advancement is not the same as turning all villages into “tourism villages.” Indonesia has recently widely practiced this type of village management. It is as if the cultural

28 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Government awards for those who have successfully mobilized the cultural ecosystem in the village and contributed to village-based cultural advancement

Village harmony in art

Photo courtesy of Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization

(Clockwise) Villagers participation in improving community welfare; Rural women empowered; Hanging out accompanied by music and songs

potential of a rural community is and can only be a tourism attraction. The reality shows that the more independent village is an agricultural village, not a commercial tourism village.

Therefore, in implementing villagebased cultural advancement programs, always remember that development is contextual. It does not use a single

formula or model applicable to all villages.

We designed the village-based cultural advancement to empower villages by developing using their potential and encouraging village collaboration. The work is networking, capitalizing on all the social networks that connect each rural community. The goal is not to turn rural

villages into urban areas but to build free associations that bring together cultural strengths from various rural villages for national cultural advancement.

(Maya Krishna, Senior Cultural Administrator, Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology)

(Maya Krishna, Senior Cultural Administrator, Directorate of Cultural Development and Utilization, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology)

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 29

Photo courtesy of Radian B. Sena

30 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022 CULTURAL EVENTS

Accumulating Cultural Actions for Sustainable Living

“G20 Culture Ministers Meeting” was held on 13 September 2022 in Borobudur with the theme Culture for Sustainable Living. The theme was selected based on the notion that the world is currently being hit by a crisis in very basic areas, such as clothing, food and shelter. The consumptive and instant

lifestyle has created heavy pressure on the carrying capacity of the environment. The meeting was conceived as a forum to roll out a new consensus in restoring human relations with nature by drawing inspiration from various local cultural practices that respect nature’s life cycle.

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 31

The ministerial level meeting was not a stand-alone event, but a culmination of a series of efforts in consolidating various local practices that took place in many regions and in many countries. In many regions in Indonesia there have been development of cultural management initiatives for the creation of a more sustainable way of life, which seeks to restore the harmonious relationship between humans and nature. These various initiatives were stimulated

from the academic level, youth to the grassroots movement.

Grassroots Movement

Within the grassroots movement, especially at the village level, various initiatives have emerged to identify local cultural potential and transform it to become the main capital for a more environmentally friendly development and to support a more human-centred socio-economic development. The Villagebased Cultural Advancement Program

is a manifestation of such initiatives. Representatives from all villages in the Borobudur area participated and held a series of Cultural Markets from July to September 2022, which showcased a variety of featured products that were selected through participatory mapping while participating in the Village-based Cultural Advancement Program. All of them are clear examples of how local culture can be a source of inspiration for creating a new, more sustainable lifestyle.

32 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

The minister chatting with a young carnival parade participant

A giant boar’s head at the culture carnival parade

(above) Ruwatan Bumi (Purging the Earth) ; (below) Inclusive spaces for interactions

The series of activities within the framework of Pekan Kebudayaan DaerahPKD (Regional Culture Week) which have been held at the district/city level across Indonesia also continue. These activities provide a forum for inclusive interaction of all public initiatives in advancing regional culture, as well as a forum for artists and cultural practitioners to showcase their cultural expressions through the organisation of regular festivals in various regions in Indonesia. From PKD, it is expected that

artists and cultural practitioners could find opportunities for development. Local culture can be an inspiration in organising brilliant strategies to overcome the obstacles of contemporary life.

Consolidation of Power

Various bottom-up initiatives that had been rolling since early 2022 have come together to become one gigantic force which laid the basis for the “G20 Culture Ministers Meeting”. All ideas

and practices were presented during a forum called the Pekan Konsolidasi Tenaga Budaya-PEKAT Budaya (Cultural Workforce Consolidation Week) which was held in early September 2022. This forum gathered representatives from culture for sustainable living initiatives, including academics, youth, as well as representatives from the Village-based Advancement of Culture Programme and the Regional Culture Week. Held in parallel in five villages in the Borobudur area (Wringin Putih, Karanganyar,

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 33

Karangrejo, Wanurejo, and Candirejo), the collective deliberation forum brought together cultural actors, academics and village representatives to consolidate key messages to be conveyed at the G20 Culture Ministers Meeting on 13 September 2022.

To convey the key messages, community members in the Borobudur area participated in the cultural parade which travelled from Pawon Temple to Borobudur Temple on 12 September 2022 and held a large gathering upon their arrival at the Lumbini Garden of Borobudur Temple Compound. The cultural parade was a manifestation of the community’s seriousness in creating lifestyle changes, an embodiment of

the collective energy of national cultural actors to create a new world that is fair and physically and spiritually prosperous. Through the 45-minute procession, there was a general will to restore cosmic harmony, to end the metabolic rift between humans and nature, through cultural means. The large gathering with participation of thousands of community members became the culmination of this procession. They held a ritual meal together at the Lumbini Garden as a symbol of solidarity with other creatures from different realms of nature and conveyed their aspirations through a series of performances which were artistic adaptations of the various issues they had discussed in the series of preceding activities.

New Commitment

This entire series of activities ultimately culminated in the “G20 Culture Ministers Meeting” at the Plataran Hotel on 13 September 2022. Representatives from the grassroots level movement conveyed the Borobudur Mandate, a manifesto that contains the stance of cultural actors from various regions and countries regarding what to do if life on earth will

34 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Enthusiastic crowd watching the carnival parade

continue. This mandate states, among other things, that “we must leave behind a universe with better conditions than today”. The reading of the Borobudur Mandate became one of the key considerations in formulating the results of the meeting of ministers from G20 member countries in the field of culture.

In line with the Borobudur Mandate, the G20 Culture Ministers Meeting concluded with a joint commitment to encourage an increase in the role of culture to

enable a transition towards a system that is more aligned with sustainable living. The Minister of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia stated in the Chair’s Summary of the G20 Culture Ministers Meeting that culture has intrinsic value beyond its social and economic benefits, and that it is important to encourage significant changes in society’s ways of life that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. “Equally important is the joint commitment to explore the creation of the Global Arts and Culture Recovery Fund that could be managed by UNESCO, on a voluntary basis, to restore the cultural economic sector and to promote sustainable living, which could be discussed in the Finance Track of the G20”.

To reinforce the message of culturebased global recovery, the Ruwatan Bumi (Earth Healing Ritual) was held at Borobudur. Hundreds of delegates along with thousands of participants witnessed a series of performative rituals featuring traditional vocal-based songs from various parts of the archipelago. Messages of sustainable living based on traditional culture were highlighted through the fabric of local narratives. The “G20 Culture Ministers Meeting” is undoubtedly part of the cultural actions from various regions and parts of the world which encourage transition toward a system that is more aligned with sustainable living

(Martin Suryajaya, Indonesiana)

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 35

Photo courtesy of MoECRT

When Traditional Music Makes a Spectacle at Lake Toba

“Sorry, Bro. It’s been two years since the last event. I even forgot how to attach the rigging. Hehe.”

Asnippet of conversation above is the answer of Bang Ucok, a stage rigging technician, when I asked why it took him so long to build a stage rigging for the Lake Toba Music Festival Road Show in Sidikalang, Dairi Regency, North Sumatra in May 2022.

We fully understand that the policy of Imposing Restrictions towards Community Activities (PPKM) in response to the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the loss of routinely held performing arts activities before the pandemic. According to the records of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (Kemendikbudristek) of August 2021, 65% of national cultural

actors lost their jobs which resulted in a decrease in income of up to 70%, and 70% of art spaces and cultural organizations are temporarily closed.

We are seeing the return of performing arts support workers like Bang Ucok in implementing cultural activities since the government eased the PPKM policy in the past year.

This article aims to share the experience gained from implementing the Lake Toba Music Festival 2.0 series of events in May-August 2022 in the Lake Toba Area, North Sumatra. It is one of the best practices in efforts to restore

CULTURAL EVENTS

36 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

the post-pandemic arts and culture ecosystems through local community involvement.

Community Roles

Rumah Karya Indonesia (RKI), based in North Sumatra, is one community that welcomes the easing of the PPKM policy. This community was born on the premise that Indonesia is rich in ethnic groups. In North Sumatra alone, there are at least dozens of ethnic community groups that have been living in harmony.

These community groups have a good deal of heritage of high-value traditional artworks. Unfortunately, these indigenous artworks are not well-developed. People even take it for granted. As a result, many indigenous art forms are in danger of becoming extinct, including the supporting instruments and the knowledge they have. RKI’s activities focus on the administration and management of traditional music performances, research, publications, and documentation.

Since 2021, RKI has started the implementation of a traditional music festival that aims to build a cultural ecosystem in advancing culture and

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 37

Harmonious inang ensemble Marsada

expediting the economy in the Lake Toba Area through an indigenous music festival. It is also in line with the theme of the G20 Presidency, ‘Recover Together, Recover Stronger.’

Lake Toba Music Festival 2.0 UNESCO has designated lake Toba, or the Toba Caldera, a UNESCO Global Geopark. This area has geological and high-value traditional heritage linkages with the local community, especially cultural heritage. Other regions of Indonesia and even Southeast Asia also have geoparks. Likewise, with Lake Toba, several areas that have geoparks must also have high-value traditional heritage, especially cultural heritage. Because

of this similarity, Lake Toba Traditional Music Festival 2.0 invites a network of traditional musicians in the geopark area, both local and national, as well as from abroad.

Lake Toba Music Traditional Festival 2.0 is the brainchild of Rumah Karya Indonesia, where artists from 4 ethnic groups in the Lake Toba Area create a collaborative work with other artists by involving the local community of Lake Toba through music. We organized this activity on the outskirts of Lake Toba, which has a cultural ecosystem potential. This kind of activity brings a positive impact on the community and visitors.

The year 2022 marks the 2nd year of the Lake Toba Traditional Music Festival organization. It is part of the Indonesian Traditional Music Festival themed ‘Suara Danau: Memaknai, Merawat dan Menghidupkan Musik Tradisi’ (The Sound of The Lake: Fathoming, Fostering, and Reviving Traditional Music). We presented these three elements as a festival. The festival encourages us to know the knowledge, learning, and development process, which we must look at as a whole.

Lake Toba Traditional Music Festival 2.0 is the culmination of the activity, a continuation of the previous Eta

38 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

Margondang event, which was held in four districts using different concepts. Lake Toba Traditional Music Festival 2.0 is also part of the program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology in collaboration with Rumah Karya Indonesia for advancing culture, especially for strengthening the Indonesian traditional music ecosystem as a manifestation of the mandate of Law no. 5 of 2017 on the Advancement of Culture.

The highlight of this show is Eta Margondang, presenting young

musicians from four ethnic groups around Lake Toba who have practiced and are creating new works they showcase to connoisseurs of traditional music. Eta Margondang also featured a collaboration of 500 flute players living around Lake Toba. Besides Eta Margondang’s performance, there was a performance by a well-known crossgeneration local band. They play a collaboration of traditional and modern music.

Referring to the theme of the G20 Presidency, “Recover Together, Recover Stronger,” efforts to speed up the recovery of the traditional music ecosystem require the support of the

community, whose role is to safeguard the socio-cultural conditions of their people.

RKI revives the art of traditional music, a form of cultural practice that ensures the continuity of a sustainable life. This performing arts activity advocated by RKI is also a cultural ritual where people gather, create, and carry out economic activities involving Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Traditional music is one of the concrete forms of culture that plays a role in a sustainable life.

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 39

(Denison Wicaksono, Directorate of Films, Music, and Media, MoECRT) Toba’s unifying harmony

Intergenerational transmission of sound

Photo courtesy of Directorate of Film, Music, and Media

Promoting Objects of Advancement of Culture

Collaboration between Local Government and Communities

CULTURAL EVENTS

40 I INDONESIANA

15, 2022

VOL.

Indonesia is a country rich in nature and culture. It is no wonder that the former UNESCO Assistant Director General for Culture

(ADG Culture)

Francesco Bandarin said to the then Minister of Education and Culture (Mendikbud) Muhadjir Effendy that Indonesia is a “superpower” country in terms of culture. This statement was conveyed during a meeting on the sidelines of the 39th UNESCO General Assembly which took place at the UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, in November 2017. This is based on the fact that Indonesia has so much natural and cultural diversity.

Indonesia has 17 thousand islands spread across 38 provinces (including 4 newly established provinces in Papua in 2022), 416 regencies, 98 cities, 7,094 sub-districts, 74,957 villages and 8,490 sub-districts (as of 2019). With this extraordinary potential, how is the governance of culture in Indonesia and what is the role of the local government in developing and utilizing cultural potential or objects of advancement of culture in their area? These are the challenges that have been addressed in the Law Number 5 of 2017 concerning the Advancement of Culture.

The Advancement of Culture, Our Shared Responsibility

Based on Law No. 5/2017, it is clear that the Advancement of Culture is under the coordination of the Minister of Education and Culture since this is part of the effort to improve cultural resilience and Indonesian cultural contribution to the development of world civilizations through cultural protection, development, utilization, and empowerment. The principles of the advancement of culture

are tolerance, diversity, locality, interterritorial, participation and benefits, sustainability, freedom of expression, integration, equality and mutual cooperation – as mandated in Law no. 5/2017 Article 3.

The aims of the advancement of culture are very noble namely to provide direction in the course of national development, including developing the nation’s virtue, enriching cultural diversity, strengthening the nation’s unity and integrity, educating the nation’s image, achieving a civil society, improving people’s welfare, preserving the nation’s cultural heritage, and contributing to the enrichment of the world’s civilization as stated in Law no. 5/2017 Article 4.

The technical implementation of the Advancement of Culture is a shared responsibility between the government and society, both individuals and communities. The local governments play an important role in the management of objects for the advancement of culture. This role is set in stages from the district, provincial and national levels. This is in line with the Law on the Advancement of Culture regarding the responsibility of regency/municipal government in identifying cultural potential in their regions by developing the Pokok Pikiran Kebudayaan Daerah-PPKD (Culture White Papers) as a reference for the advancement of culture.

PPKD (Culture White Papers)

The advancement of culture is guided by the Regency/municipal Culture White Papers, Provincial Culture White Papers, Cultural Strategy, and the Master Plan for the Advancement of Culture as stipulated in Law no. 5/2017 Article 8. Culture White

Papers are the basis for the advancement of culture that have been prepared in stages starting from the regency/ municipal level and then to the provincial and national levels as the core materials for developing Cultural Strategy which then will become the core materials for the Master Plan for the Advancement of Culture (UU No. 5/2017 Article 10).

Regency/municipal Culture White Papers describes the current condition of the objects of the advancement of culture, cultural human resources, cultural organizations, cultural institutions, infrastructure, potential problems for the advancement of culture, and analysis of and recommendations for implementing the advancement of culture in each regency/municipality (see Law No. 5/2017 Article 11 paragraph 2).

The latest data – compiled by the Center for Cultural Data and Information, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology – shows the dynamics in the preparation of Culture White Papers from 514 regencies/municipalities with the following details:

Year 2018 : 301

Year 2019 : 59

Year 2020 : 32

Year 2021 : 19

Year 2022 : 18

The data states that out of a total of 429 existing regencies/municipalities, 79 regencies/municipalities have not yet drafted their Culture White Paper, including DKI Jakarta Province which consists of 6 (six) municipalities. It should be noted that the Culture White Paper is a crucial matter that must be prepared

People take part in activities

VOL. 15, 2022 INDONESIANA I 41

Photo courtesy of Culture and Tourism Office of Semarang City

by districts/cities as part of commitment and seriousness in advancing culture. A commitment that must be renewed from time to time as a policy basis and priority setting in advancing culture in each regency/city.

Good Practices for the Advancement of Culture at Local Level

The advancement of culture at the local level requires a strong commitment both from the government and the community. Creativity, hard work, networking, and financing are required so that programs and activities could be implemented with broad and sustainable impact, while contributing to cultural preservation and improving the general welfare. In addition, there is a need for collective awareness to pass on the objects of advancement of culture especially to the younger generation.

Commitment to advancing culture stems from institutional governance as administrator of the cultural sector. Data collected up to November 2021 shows that out of 34 provinces, only 7 provinces have dedicated cultural offices, namely West Sumatra, DKI Jakarta, Riau, Bali, Riau Islands, North Sulawesi and Yogyakarta Special Region. This is in line with Law no. 23/2014 on Regional Government which states that governors and regents or mayors can establish a Regional Apparatus Organization to manage important regional affairs, including culture.

Meanwhile, regencies/cities that already have offices dedicated for culture are Sawahlunto City, Buton Regency, East Belitung Regency, East Kutai Regency, and Makassar City. These regency/municipal offices are focused on sustainably managing objects of advancement of culture and paying more attention to programmes and activities in the cultural sector which are supported by funding from the Regional Revenue and Expenditure Budget or other funds from various sources.

East Belitung Regency is committed to developing spices and maritime affairs, building a maritime museum as a support

for the revitalization of spice culture and organizing the ‘Jelajah Pesona Jalur Rempah-JPJR’ (Explore the Spice Routes) festival. Whereas, the ‘Pesta Kesenian Bali-PKB’ (Bali Arts Festival) has been organized by the government of Bali Province for decades. PKB is managed systemically with good programs, organizing mechanisms, networks and funding support. PKB has become one of the most awaited annual agenda which involves all components of Balinese society. The two local governments above are good examples of efforts for the advancement of culture which resulted from the collaboration between the local government and the community.

(left) Guest star performance with NDX

42 I INDONESIANA VOL. 15, 2022

(right) The Regent of Sragen and her staffs participate in SangiRUN Night Trail 2022

Photo courtesy of Culture and Tourism Office of Semarang City

Nonetheless, local governments that do not have their dedicated cultural office also have commitment for culture. Some of these local governments are enthusiastic in raising their cultural potential and wisdom in ways that are more creative and accepted by society. They also develop their network and create more fun and unique contemporary activities that could be of interest to the community.

Their commitment is demonstrated by organizing various cultural preservation activities, involving the community, networking with various stakeholders, and communicating with the central government in terms of program

advocacy and development. This is very positive, considering that networking with various parties will increase media exposure and result in broader impact than working in silo. Therefore, it is very important to build a strong working network between government agencies and the communities, both individuals and groups, to synergize the efforts for the advancement of culture at the local level.