Designing a harmonious world Habitus Environment Issue Three of Six Collectables #62

Guest Editor Adam Goodrum

Keiji Ashizawa

Various Associates

Multiplicity

Pac Studio

Kristina Pickford

Enter Projects Asia

Vokes and Peters

Blok Modular

Blur Architecture

Neogenesis+Studi0261

Judith Neilson

The Duchess of Northumberland

Earthitects

Ishinomaki Laboratory

Arthur Seigneur

Martyn Thompson

Olive Gill-Hille

Alfred Lowe

Suna Fujita

Isama Noguchi

True to Nature:

Next Generation Woodgrains

Introducing the newest innovation in truly life-like Laminex Woodgrains that celebrate the brilliance of nature. Featuring our new premium AbsoluteGrain® finish for a more authentic look and feel, and TrueScale™ technology for no repeat designs, this extraordinary range includes six new Australian Native woodgrains, designed to complement the existing range of Laminex décors.

Bring the look and feel of nature to any project — with the durability of Laminex.

Eveneer® Prefinished meets the needs of today’s projects offering a convenient and consistent timber veneer, pre-polished and ready to use.

Eveneer Prefinished Fango by Elton Group Design Tom Mark Henry

Photo Cieran Murphy

The fi rst word

As a designer, it is such a privilege to step up for my fellow makers as Guest Editor and let the spotlight shine on some of our incredibly talented designers, artists, craftspeople and architects shaping our world. It’s impossible to include everyone so I have put together some of my favourites from the past and working now, plus some people who just really surprise me with work that continues to resonate (p. 55).

Judith Neilson is such an incredible person I had to include her with an article by another of my favourites, David Clark (p.76).

The theme, ‘living in the environment’ really threads its way through the whole issue, but Earthitects, building homes in coffee plantations (p.84) and the Duchess of Northumberland, creating a Poison Garden (p. 90) really kicks it off.

From building in cold climates (p.100) to bird watching in Arnhem Land (108), how we live in a changing climate has never been more prescient. But how we live in the world as a Pacific identity is also germane, with the Asia Pacific Triennial focusing on culture and our unique personality (p. 114).

The projects are amazing with my friend Keiji Ashizawa giving us a look at a very private garden house in Tokyo (p. 150). A multigenerational home in China is made of bricks using weeds and mud from the site (p. 130) while a vast multi-generational family home in India uses foliage to frame and cool the interior (p.196). Davis by Blur Architecture in Melbourne is completely cool, as is the article by Georgina Safe (p. 188). Beach houses are a particular interest for me with two incredible projects, one in NZ (p. 158) and one in Aireys Inlet Victoria (p. 140), really getting it right. In Thailand the fabulous Enter Projects Asia has used bricks in magical ways to make a remarkable home (p. 168), while back in Australia Brisbane practice Vokes and Peters has teamed up with Blok Modular for an inspiring take on prefab (p.178).

ADAM GOODRUM GUEST EDITOR

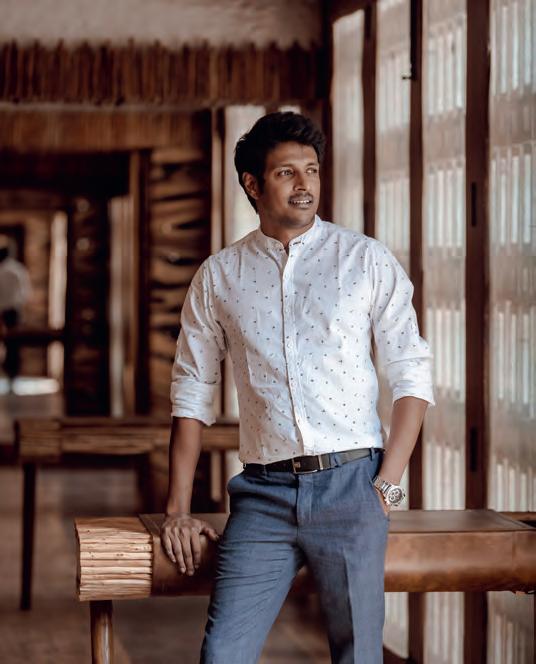

ABOVE Guest Editor Adam Goodrum.

lightbox #21

A gathering of the most beautiful, interesting and sometimes challenging designs shaping our world.

makers #55

Meeting the makers, some iconic, some emerging, but all creating amazing pieces to fall in love with.

portrait #75

O ne of the great philanthropists of this generation, Neilson is patron to the arts, across art, architecture, design, writing and music.

Reimagining how coffee plantations can be sustainable from an economic, environmental and cultural aspect.

Bucking English conventions for passive gardens, the Poison Garden of Alnwick Castle questions how we live with plants.

JUDITH NEILSON

TH E DUCHESS OF NORTHUMBERLAND

Living in the environment

Guiding us through the way design adapts and responds to the environment, Guest Editor Adam Goodrum puts his very particular lens on those shaping our world.

features #98

100 BUILDING IN THE COLD

Keeping the house warm but letting the view in, is just the start of this challenging space.

108 BAMURRU PLAINS

Once a hunting lodge, this East Arnhem eco-lodge is a twitchers paradise.

114 QAGOMA ASIA PACIFIC TRIENNIAL OF CONTEMPORARY ART

The environment has never been more important with artists from our region expressing their concerns in remarkable ways.

122 NAU IN OSAKA AND COPENHAGEN

Australian design is reaching greater audiences across the globe.

on location #129

130 G ONG’S HOUSE

In an environment of perpetual rain, bricks made of local herbs allow this multi-generational home to breathe.

140 AI REYS INLET HOUSE

Neighbours, the environment and the owner’s shell collection are all considered.

150 GA RDEN HOUSE

A small house at the end of the garden for contemplation and peace.

158 WAIMATARURU

Framing and framed, the beach house is perfectly aligned to the landscape.

168 T HE BRICKHOUSE

Rejecting traditional Thai materials in favour of brick, the house is perfect for living.

178 1 :1

A full sized model explores the benefits of prefab.

186 DAVIS

A private pavilion with architectural clout and some seriously gorgeous copper cladding.

196 R ETREAT HOME

Fringed in leaves the cool breez e flows through this extraordinary home.

Habitus takes the conversation to our contributors, discovering their inspiration and design hunter® journeys

ADAM GOODRUM

ALEESHA CALLAHAN

DAVID CLARK

Arguably the loveliest person in design, Adam i s a fi rm believer that every environment is defi ned by the objects within it. As such, he designs to the philosophy that an object must justify its existence – through its story and detailing. Celebrating process and craftsmanship, his designs accentuate components and joinery to create functional pieces with spirit and personality. Adam’s work has been awarded a host of design accolades including the NGV Rigg Prize, Vogue x Alessi Design Prize, and the INDE Luminary Award. His work has been commissioned by global luxury brands including Veuve Clicquot, Alessi and Cappellini. He is also an artist and with Arthur Seigneur is A&A, noted as one of the top 100 designers working today by Louis Vuitton.

ADAM GOODRUM #72

One of the most inspiring and thoughtful writers in the realm of architecture and design, Aleesha has written and commentated on every aspect of the creative world shaping our lives for the past ten years. As the previous Editor of Habitus she introduced Australia to a plethora of architects, interior designers, artist, artisans and the shifts in thinking behind these talented makers.

Having fi rst trained and practised as an interior designer, her passion for mid-century design and architecture began while living and working in Berlin. She continues to enrich our world as a contributing writer, with her extraordinary ability for getting to the heart of the issue always impressing.

1:1 #180

David has worked in the interior design industry for more than 30 years as a curator, consultant, creative director, and editor. His publishing career began as design editor for Belle magazine and as Editor-in-Chief of Vogue Living Australia (2003–2012) he elevated Australian designers globally. He was inducted into the Design Institute of Australia Hall of Fame, and made an Honouree of the Australian Design Centre. He is an advocate for the continuing elevation of an Australian design ecosystem and good design everywhere. Portrait photographyJenni Hare.

JUDITH NEILSON #76

Sam is a Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland-based photographer specialising in architecture and art documentation. His work features regularly in architecture, interiors, design an d fi ne art periodicals and publications. As a photographer he is rarely the subject of his own work, and like the architect without a new kitchen, he is a photographer with few photos. That said, his role as an artist comes to the fore with his abstract take on the selfportrait. More generally, as an artist his work focuses on the odd with a sharp eye for the poignancy of every day moments. He is represented by Anna Miles Gallery in Auckland.

WAIMATARURU HOUSE #162

SAM HARTNETT

In her role as Editor of Habitus Magazine, Gillian brings a twentyyear oeuvre of design writing to the publication. Focusing on architecture, design, art and interior design, her breadth of knowledge is expansive and generous with all genres and styles regarded for their own merit. For the highly collectable series of Six, Gillian is working with the best designers in the Indo-pacifi region to create content that is engaged and varied. Moreover, by creating each issue through the lens of her Guest Editors, their unique personality is allowed to shape each issue of Habitus. The result is always surprising.

GONG’S HOUSE # 130

George is one of Australia’s most beloved writers. With a twentyyear portfolio across fashion and design, her articles covering the Australian fashion industry and the international collections in Milan, Paris, New York and London have been a revelation of sparkling wit. Her work across design and architecture is similarly insightful, with a keen eye for what does and doesn’t work, plus a fearless approach to quizzing her subjects, as both their design and intent come under her gaze. In this issue she loses her heart to the extraordinary Davis by Blur Architects.

DAVIS # 188

Sarah is always on point as an art, architecture and design writer. A member of the International Art Critics Association (AICA), Sarah was most recently Director, Galleries at Sydney Contemporary – Australasia’s premier art fair. In this role she held the curatorial responsibility for Installation Contemporary featuring 13 largescale projects spanning the iconic, heritage-listed Carriageworks. With over two decades’ experience working in the art world, Sarah has previously held positions at the Biennale of Sydney, Liverpool Street Gallery and Ivan Dougherty Gallery, UNSW. Sarah was a Board Director of Art Month Sydney during its inaugural year and for many years has been an Asia Paci fi c Correspondent in the architecture and design media.

QAGOMA ASIA PACIFIC TRIENNIAL #114

One of the best writers in the industry, Jan is currently an Editor and Program Director of the INDE.Awards at Indesign Media Asia Paci fi c. Her previous roles have included Acting-editor of Indesign magazine, Associate Publisher at Architecture Media, Editor and Co-editor of inside magazine and Interiors Editor of Architel.tv. As Principal of Henderson Media Consultants she contributes to various architecture and design magazines, is a regular speaker at events and has participated as a juror for many industry awards. Jan is passionate about design and through her di ff erent roles supports and contributes to design in Australia.

THE BRICKHOUSE #168

JAN HENDERSON

SARAH HETHERINGTON

GILLIAN SERISIER

GEORGINA SAFE

CHAIRMAN

Raj Nandan raj@indesign.com.au

GUEST EDITOR

Adam Goodrum gillian@indesign.com.au

EDITOR

Gillian Serisier gillian@indesign.com.au

DIGITAL EDITOR

Timothy Alouani-Roby timothy@indesign.com.au

SUB EDITOR

Aleesha Callahan

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Sylvia Weimer sylvia@spacelabdesign.com

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Timothy Alouani-Roby, Aleesha Callahan, David Clark, Stephen Crafti, Jet Geaghan, Dr Prudence Gibson, Adam Goodrum, Jan Henderson, Sarah Hetherington, Georgina Safe, Gillian Serisier.

CONTRIBUTING

PHOTOGRAPHERS/ ARTISTS

Adisornr, Alexander Calder, Chloe Callistemon, Hayden Cattach, Suna Fujita, Olive Gill-Hille, Samuel Hartnett, Dylan James, Christopher Frederick Jones, Timothy Kaye, Jonathan Leijonhufvud, Alfred Lowe, Tadayuki Minamoto, Trevor Mein, Isama Noguchi, Josh Purnel, Ben Richards, David Roche, Dion Robson, Joe Ruckli, Ishita Sitwala, Martyn Thompson, Victoria Zschommler.

PRODUCT MANAGER

Radu Enache radu@indesign.com.au

COVER IMAGE

CEO Kavita Lala kavita@indesign.com.au

SENIOR BRAND MANAGER

Brunetta Stocco brunetta@indesign.com.au

PARTNERSHIPS AND MEDIA MANAGER

Katie Staver katie@indesign.com.au

MEDIA EXECUTIVE

Avaani Nandan avaani@indesign.com.au

GROUP OPERATIONS MANAGER

Sheree Bryant sheree@indesign.com.au

HEAD OF PRODUCTION

Anna Carmody anna@indesign.com.au

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Paul Ayoub print@indesign.com.au

FINANCE MANAGER

Vivia Felice vivia@indesign.com.au

MARKETING EXECUTIVE

Nicola Nolan nicola@indesign.com.au

EVENT MANAGER

Roisin Fagan roisin@indesign.com.au

Davis by Blur Architecture on Wurundjeri Country / Collingwood, Victoria. Photo, Dion Robeson. Page 186.

HEAD OFFICE 98 Holdsworth Street, Woollahra NSW 2025 (61 2) 9368 0150 | (61 2) 9368 0289 (fax) www.habitusliving.com

Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information in this publication, the publishers assume no responsibility for errors or omissions or any consequences of reliance on this publication. The opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the editor, the publisher or the publication. Contributions are submitted at the sender’s risk, and Indesign Media Asia Paci fic cannot accept any loss or damage. Please retain duplicates of text and images. Habitus magazine is a wholly owned Australian publication, which is designed and published in Australia. Habitus is published quarterly and is available through subscription, at major newsagencies and bookshops throughout Australia, New Zealand, South-East Asia and the United States of America. This issue of Habitus magazine may contain offers or surveys which may require you to provide information about yourself. If you provide such information to us we may use the information to provide you with products or services we have. We may also provide this information to parties who provide the products or services on our behalf (such as ful fi lment organisations). We do not sell your information to third parties under any circumstances, however, these parties may retain the information we provide for future activities of their own, including direct marketing. We may retain your information

THE TEAM AT HABITUS MAGAZINE THANKS OUR ADVERTISERS FOR THEIR SUPPORT. USE THE DIRECTORY TO SEE WHAT PAGE A SPECIFIC BRAND IS FEATURED ON, AND VISIT THEIR WEBSITE TO LEARN ABOUT THE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES THEY PROVIDE.

Apato 074 apato.com.au

Australian Design & Co. 03 4 australiandesignandco.au

Baya 128 bayaliving.com

CDK Stone 096-097 cdkstone.com.au

Cult 031 cultdesign.com.au

Domo 037 domo.com.au

Elton Group 006-007 eltongroup.com

Fhiaba 044 fhiaba.com.au

Fulgor Milano 03 3 fulgor-milano.com/int/en Gaggenau IFC-001 gaggenau.com.au

Harvey Norman 014 -015 harveynorman.com.au

John Eussen 126-127 instagram.com/johneussenoffiicia/ Kanebridge IBC kanebridgenews.com

Karndean 043 karndean.com/en-au/floors

Klaro Industrial Design 047 klarodesign.com.au Laminex

laminex.com.au

molmic.com.au Poliform 017 poliformaustralia.com.au

Siemens 025-026 winnings.com.au/brands/siemens

Habitus magazine is available at newsagents and bookstores across the Asia-Pacific egion. Habitus is published three times per year in March, June, October. To subscribe securely online visit habitusliving.com/magazine or email subscriptions@indesign.com.au to subscribe or request a full list of locations where Habitus magazine is available.

Designs for living lightbox #21

Design worth celebrating

The objects and furnishings, lighting and textures we surround ourselves with are defining of both the times and our own unique aesthetic sensibilities: these should always be celebrated.

“I found myself drawn to the silent, sculptural qualities of sand dunes, fascinated by their ability to off er shelter and protection from the winds,” says DANIEL BODDAM of his latest exploration of ‘the poetry of reduction’ realised as the wonderfully sculptural collection DUNE .

danielboddam.com

Fabulously tactile and decidedly Italian, the VENICE range from S’48 tells the story of the Satori family’s bold move into outdoor furniture in postwar Italy. Always evolving, but always on point, the powder-coated frames and rope detailing add panache to any setting.

obodo.com.au

Celebrating 60 years since the iconic UNIKKO print came into this world, the MARIMEKKO go-to design continues to reinvent itself and impress. Designed by Maija Isola to be an abstraction of a poppy rather than a photorealistic impression, it was instantly loved the world over. Now available in gorgeous rugs for indoor and out, Unikko is just one stream of the 17 new iterations.

myer.com.au

ECCENTRIC by ROGERSELLER pays homage to the quirky genius of some of history’s greatest minds. When engaged, the uniquely off-centered axis of the mixer embraces this quirky genius by progressively revealing an unexpected backplate featuring cold and hot indicators. Once the handle is returned to its closed position, the unconventional backplate is hidden once again. Genius!

rogerseller.com.au

Always at the forefront of design, SPACE FURNITURE has launched SPACE ARCHITECTURAL SOLUTIONS with the same rigour of curation that has set the store apart. The brands are the who’s who of interior delights with Listone Giordano, Moooi Carpets, Glas Italia, Poliform, Lee Broom, Bocci and Roll & Hill just to get them started.

spacefurniture.com.au

TONGUE & GROOVE makes speci fication effortless with GRADING. The naturally occurring beauty and characteristics of European oak reside in its knots, grain, and medullary rays. Grading is used to categorise the prevalence of these natural features, with high quality assured across all iterations. This gives designers unprecedented choice and the ability to create consistently beautiful interiors.

tongueandgroove.com.au

“The greatest joy was getting your hands on a sheet of Laminex t o fl y down the sandhills,” says ADAM GOODRUM of the incredible material that was once synonymous with dune sur fi ng and kitchen tables, which he has now reimagined as the ECHO TABLE , a flexible, and extraordinarily beautiful table (with a nod to the Art Deco envelope table) in celebration of LAMINEX ’s 90th Birthday.

laminex.com.au

Elemental living

T39EL

Is this the future of cooking?

A fusion of intelligence and design is here, and it’s harnessing the power of AI to change the cooking game.

The kitchen may be the heart of the home, but it is also the brain centre, where the latest in innovation and technology can help us cook, entertain, and connect. The newest release from Siemens is taking this to a whole new level, with the launch of the iQ700 studioLine range bringing cutting edge performance and an elegant new design profile to kitchens around the world.

Made for master chefs to novices, and everyone in between, the range empowers us to dream bigger in the kitchen. Enabling consistent, supported cooking that looks as good as it cooks, the black profile sits sleekly against stone, timber, stainless steel, and tiles. A visual statement in its own right, the smooth, polished look elevates the entire kitchen space. Moreover, the black handle sits as a wide, thin feature, blending seamlessly into the oven front for a modern interpretation of the appliance’s most functional element. Simple and intuitive touch-screen navigation reflects the oven’s design approach, by packing the impressive suite of features into a simple bar.

From a technological perspective, the iQ700 range offers AI powered automation and an unprecedented intelligence for home cooking. Like having a sous chef by your side, the new range is perfect for those that prefer to relax or entertain rather than watch over their oven.

With technology across the range including automatic food recognition (currently recognising up to 50 dishes), the oven will automatically select the right program for a perfect finish, while new bakingSensor Plus and RoastingSensor

LEFT AND ABOVE

The iQ700 studioLine range from Siemens.

Plus features can predict the remaining time by measuring the moisture levels and the meat temperatures respectively. A fully integrated camera will also adapt baking and roasting results to personal preference, harnessing artificial intelligence to produce the desired amount of browning from five different levels.

When a quick and easy cook is on the menu, the iQ700 range’s built-in microwave and/or steam cooking functions can allow for faster, healthier meals, without the fuss. The integrated microwave works alongside hot-air cooking, to speed up the preparation of dishes by up to 50 per cent, while a coolStart feature cuts out time consuming thawing, allowing you to put frozen dishes directly into the oven for a single-step cooking session.

When it comes to steaming, fullSteam Plus combines steam and heat at 120°C for a 20 per cent faster cooking time that preserves the vitamins and goodness of your vegetables. A plumbed water connection automates this process, ensuring the oven’s water tank is always full, while the adjacent pulseSteam feature uses hot-air to allow for crisp and moist finishes to raise the bar on traditional steaming. Additionally, the iQ700 comes with an AirFry option to create extra crisp finishes with hardly any oil.

Whether you’ve got a soufflé or frozen fries on the menu, the iQ700 range is ready to turn out a perfect dish, every time. The ultimate convergence of design, innovation and cutting-edge performance, the different options in the range can see baking, roasting, steaming, microwaving, and airfrying made easier than ever before, all just a touch away. What’s more, simple navigation and a sophisticated aesthetic mean performance and design go hand in hand, bringing Michelin-level cooking and magazine-worthy interiors into one, futuristic range.

The EPSON INTERNATIONAL PANO AWARDS ’ overall winner of the 2024 Open Photographer of the Year and the Nature/Landscape category is KELVIN YUEN from Hong Kong for his entries Power of Nature, Wilderness and Mountain of Divinity. “The primary goal of this trip was to capture the iconic mountains of Guilin, renowned for its karst formations,” says Yuen, whose initial plan was thwarted by a thunderstorm, only to reveal a new experience of illuminated layers. Power of Nature, Kelvin Yuen.

thepanoawards.com

House planting

TEXT JET GEAGHAN, ASSOCIATE, WOODS BAGOT

When looking for a house plant, my mind drifts to the understorey of dense bush, or the shaded gullies in the national parks, where light is filtered, and only the most competitive and spartan species survive. From these, a few beauties strike me as true stand-outs.

The leaves of this little pearl, Ligularia dentata reniformis (Ragwort), form a glossy colony of legumes, geometrically uniform but diverse in scale. AKA the Tractor Seat plant, the agricultural reference reminds me of the comfort of functional furniture. Congenially huddled, the foliage is so calmly balanced it begs to be reclined on, like a mound of glossy throw pillows.

Alocasia sanderiana has the tensile strength and tenacity to populate spaces at eye level where their poise captures and holds the gaze. Specimens with projectile shaped leaves and pure curves are like a complementary feature floor lamp – the unbelievable cantilever is best celebrated in varieties with dark, velveteen leaves, feline veins and a pseudo-translucency to the stem.

There are plenty of popular indoor fig species, but my heart cannot stray from the bruiser: Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay Fig). Buttressed trunk and aerial roots are like twisted gothic architecture, and appear in even the smallest of pots and make for a striking bonsai with giant waxy green leaves that hide an oxidised underbelly, and a trunk that could a tangle of Greco-Roman wrestler.

An Australian native fig is especially sentimental for me – several years ago, an overripe seed cluster fell into my open palm from a giant multi-centenarian park specimen, as if from the sky, a few days before my kid was born. From that dried fig I now have dozens of macho potted plants around my house, all celebrating their birthday with my son.

Streamlined and polished

Functional design now sits at that incredible nexus of ease-of-use and eye appeal, where everything works as it should, looks amazing and makes us wonder why we ever put up with less.

Driven by the three pillars of quality, health, and sustainability PARISI in partnership with Newform, has developed a water puri fication system that eliminates hexavalent chromium for better health, safety, and environmental protection. Thanks to the switch to trivalent chromium, PARISI has redefi ned standards of sustainability and quality in Italian-made excellence. parisi.com.au

Created in collaboration with industrial designer ZACHARY HANNA , the lamp collection from MUD AUSTRALIA was a year in the making and represents Mud Australia’s fi rst foray into collaborative design. Each of the three lamps merges traditional artisanal porcelain-making methods with the intricate demands of contemporary lighting. Photo, Sean Fennessy.

mudaustralia.com

@fulgormilano_au

www.fulgormilano.kitchen

L’eleganza italiana sulla scena mondiale.

Bringing the beauty of Italian design to your kitchen. Combining innovative technology with elegant craftsmanship, the Matteo range of induction cooktops and built-in ovens ensure high-performance cooking with a sleek aesthetic.

Transcend your space with Fulgor Milano.

Pictured: Fulgor Milano Matteo Series in Matt Black

JUN meaning ‘pure and sincere’ in Japanese is highl y fi tting for a collection that touches the heart. The eponymous creation designed by Compasso d’Oro winner MARCO ACERBIS for TALENTI, delivers an immediate and authentic design. Celebrating the interplay of voluminous cushions and the clean lines of teak, the collection is an aesthetic big bang combining great comfort and visual presence.

www.talentispa.com

An exploration of biomorphic shapes and structures, PIETRA by GREG NATALE is inspired by the contrast between organic forms and manmade geometry within modern and contemporary design and architecture. The interplay between form and void fosters an intricate design dialogue that is as dynamic as it is beautiful.

gregnatale.com

SIEMENS IQ700 built-in oven with added steam or microwave function uses AI in conjunction with an integrated camera to automatically produce the desired amount of browning fr om fi ve di ff erent levels. Moreover, currently recognising 50 dishes, simply place the dish inside, and the appliance will automatically select the right program.

winnings.com.au/siemens

The next generation in solar power is here. Designed to look like tiles, but now a solar power generating system. Genius. E ff ectively, VOLT SOLAR TILES integrate with Bristile Roofi ng’s roof tiles for a seamless integrated solar solution.

volt-tile.com

Domo Showrooms in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane & Adelaide

Robust whimsy

These seemingly contradictory aspects of design are brought together with magnificence by incredible designers who understand character, joy and the insouciance of excellent pieces that make our homes unique.

Gorgeous blocks of deep rich colour and the newly introduced surface options for outdoor use, make BREEZE by ROSS GARDAM one of the most engaging and versatile ways to bring a bright dash of colour to both indoor and outdoor spaces. Launched at Saturday Indesign with Stylecraft, the range includes a new marble option sourced from the Pilbara. stylecraft.com.au

Sydney-based design studio OBJECT DENSITY ri ff s on the philosophy of Ai Weiwei — “When a person attempts to determine his relationship to a space, he attempts to understand that which is outside his own body, he attempts to understand existence beyond the material” — to deliver the latest explorative collection PROPORTIONS OF SPACE .

objectdensity.com

Always at the forefront of the design movement, Ligne Roset’s new reedition of the emblematic KASHIMA seating collection designed by MICHEL DUCAROY, available through DOMO, continues to impress. Noted as the ‘comfortable Chester fi eld’ Kashima’s original mid-century design and generous proportions are gorgeously enhanced by a fully quilted cover with pinched seam details.

domo.com.au

making places inspiring

Play around with colours, shapes and dimensions and design your own furniture with our online configurator

Australia: Anibou – anibou.com.au

Sydney 726 Bourke St.Redfern NSW 2016, 02 9319 0655

Melbourne 3 Newton Street, Cremorne VIC 3121, 03 9416 3671 info@anibou.com.au

New Zealand: ECC – ecc.co.nz

Auckland 39 NugentSt Grafton 1023, 09 379 9680

Christchurch 145 Victoria Street, Christchurch Central 8013, 03 353 0586

Wellington 61 Thorndon Quay, Pipitea 6021, 04 473 3456 info@ecc.co.nz

Designed by Jesús Gasca and Jon Gasca for STUA , the PETAL TABLE is gorgeously elegant. Embodying modern craftsmanship, the design’s organic forms of gently curved, petal-shaped legs revere nature with sustainability and just a touch of playfulness.

stylecraft.com.au

TRENT JANSEN is a designer who absolutely never fails to turn design expectations on its head. New from the studio, SWAMP CREATURE LOUNGE , does this in spades, with the squishy curves and contours of this incredible design presenting the ubiquitous lounge chair as something altogether unique, inviting and completely sculptural. Love love love!

trentjansen.com

INSPIRED BY NATURE, BUILT FOR LIVING

Discover resilient designs that bring the beauty of natural materials, the practicality of advanced engineering, and the innovation to transform modern spaces. Perfect for creating luxurious, enduring interiors with ease.

Elevate every step and discover resilient LVT designs that bring luxury, practicality, and innovation to modern spaces.

karndeancommercial.com

@fhiaba_au

Redefining Refrigeration

Fhiaba, the epitome of luxury kitchen appliances, is the perfect choice for those who demand the highest quality and design standards. Made in Italy with meticulous attention to detail, Fhiaba products boast premium finishes and sophisticated style, elevating the look and feel of any kitchen.

Pictured: Fhiaba X-Pro Series 75cm Refrigerator in Satin Steel Made in Italy

Bringing together fi ne timbers, timeless European craftsmanship and a global design vision, Portugal-based furniture brand DE LA ESPADA draws its design ethos from in fluences including the Arts and Crafts movement, the minimalism of contemporary architecture, and 1950s Scandinavian elegance. Recently, De La Espada partnered with Italian designer LUCA NICHETTO to launch the AZORES COLLECTION, showcasing luxurious upholstery and solid wood. Magní fico.

winnnings.com.au

‘Exceptionally useful; occasionally functional’ the delicious inventions of DIEGO FAIVRE take on the traditional Australian milk bar with his exhibition for USEFUL OBJECTS, titled Diego Super Bonza Store. The gorgeously quirky pieces are each a delight, and en masse deliver a world unto themselves.

usefulobjects.com.au

Taking inspiration from the Amal fi coast, Amal fi , Miami is the latest body of work from Italian artist SAURO MELCHIORRI . Opening at STUDIOTWENTYSEVEN ’S Miami gallery for Miami Art Week, the solo exhibition celebrates Melchiorri’s passion for raw materiality and form. “His ability to translate the beauty of organic materials into timeless works of art and design is built on a rigorous respect for nature and deep knowledge of art and design” says Nacho Polo, founder and creative director at STUDIOTWENTYSEVEN. Photo, Kris Tamburello.

Studiotwentyseven.com

KELLY WEARSTLER just keeps getting better and better with some excellent collaborations shaping her work. The latest range NUDO 2.0 are phenomenally good, stools, chairs, benches to die for, a table that switches between ping-pong and dining, and some seriously great coffee and side tables are all carved form onyx by ARCA , yet continue the narrative of textiles established in the original NUDO series.

kellywearstler.com

A coffee table for conversations

A desk for your hustle

A dining table for memorable meals

A bar table for elevated evenings

Shop now, Elevate your space a table that moves with you

PETRINA HICKS, the recipient of the Korea-Australia Arts Foundation Prize (KAAFP) for her work Mnemosyne IV, presents this piece as the centrepiece of her new series and landmark solo exhibition at the Museum of Australian Photography (MoAP) in Melbourne. Her meticulously choreographed images are lensed with a heightened, hyperreal precision, subverting the coolly seductive visual language of advertising while drawing motifs from classical myths, folklore and art history to reframe the contemporary female experience.

michaelreid.com.au

Perfectly aligned

Celebrating the original, while bringing the whole into a contemporary aesthetic, is just the starting point for Winter Architecture’s approach to Cremorne Townhouse.

[The] minimal approach also allows the home to function in different ways.

As a collective, Winter Architecture is an everchanging entity that at one particular point was largely comprised of architects who had been taught by Richard Tucker during their studies. As such, it was true kismet when Tucker approached the practice during this period to rethink this townhouse. “It was an honour to be asked,” says Jean Graham, project lead and Director of Winter Architecture.

Built in 1995, the townhouse is one of a series of townhouses designed by architect Craig A. Rosetti, and the recipient of the Robin Boyd Sustainability Award for its use of cost-effective materials. The thinking behind these materials has been continued with Winter Architecture approaching the project from a position of reuse and cherish, rather than overhaul and deny. “We are trying to enhance what was there: we felt we should celebrate the existing. So, even though it’s old, doesn’t mean it’s bad,” says Graham. Adding, “The spotted gum floors are exquisite, but they were in the wrong varnish and had become orange with time. We sanded them back and now they look amazing. It’s a solid wood floor. You can’t get that anymore.”

THROUGHOUT

Cremorne Townhouse by Winter Architecture, photography by Anthony Richardson. ABOVE Reflective surfaces soften the dark palette.

This kind of intervention expands the narrative of the original to a new level of richness and can be wholly transformational. In fact, the built changes on this project, at around 11-square-metres, are minimal. “The footprint of intervention is so little, it is hardly anything, but the change is phenomenal and it makes such a big impact on how they are able to use the house,” shares Graham.

Introducing a dark palette with soft lighting, the aesthetic suits the owners’ lifestyle and negates the light-industrial feel of the original build. The staircase for example, is now dark with all structural elements quite quickly being covered in vines to eventually be a green wall seen from all three floors.

Winter Architecture and Graham’s forte however is a meticulous attention to aligned detailing. “When you can do that properly, that level of detail creates comfort for the user in a way that is subconscious, and you relax in the space,” says Graham of the perfectly aligned Besser blocks, cabinetry, shelving and mirrors that make the kitchen so extraordinary.

Within the dark palette, the V-ZUG Combi-Steamer oven and V-ZUG Cooktop seamlessly integrate and add to the aligned grid foundation. “When everything is aligned it becomes quieter and just makes sense” says Graham, who has noted that the clients use the cooktop as an extension of the working surface and often put things on it as you would a tray.

“It has become part of the benchtop at a seamless level, which is only demarked by the reflective surface,” she says.

With space at a premium, functionality that paired with lifestyle was a prerequisite for all utilities. As such, a beer tap, for example was selected over a hot tap. Likewise, the oven needed to “work hard and provide multiple options,” Graham shares. The V-ZUG CombiSteamer oven was selected for just that, with baking, steaming and a great range of cooking functions within a minimal presence.

This minimal approach also allows the home to function in different ways. “It’s considered minimalism in that it’s a platform for the user to be creative, so they can choose to add or subtract according to their personalities or their use of the space,” says Graham, who notes that the client presented an unusual request. “They came to us with a pool table with the idea of a dining table that is also a pool table. They got the table second hand, but they really loved the idea,” she says. Now very much the centrepiece of the kitchen, the cabinetry and benches are also aligned to accommodate the two different heights of the players. Yet nothing looks contrived. Rather it is spacious and exceedingly clever with specific cabinetry such as a slim cooking utensil drawer right where it is needed.

OPPOSITE

On the upper floors, this same attention to detail, mirror and, aligned volumes and grids, has had a transformative effect. A large services area for example, blocked much of the view, while a bathroom, though boasting a large bath, was unusable. Winter Architecture’s intervention here, while restrained is profound. “We created the space to be used by the clients in different ways. When alone or when guests are staying. If they are alone or feeling brave they can bathe with the door open,” she says. As such, the bathroom on the top floor for the primary bedroom is small with the basin tucked behind a mirror. On the middle floor however, the bathing is expansive, where the clients are more likely to bathe when alone.

Beautiful, rich, minimal and decidedly sustainable, Winter Architecture is proving itself a remarkable practice in making a space work for its owners and the environment.

V-ZUG Cooktop and CombiSteamer oven are seamlessly integrated into the design.

Coming to

Melbourne

Saturday Indesign is coming back to Melbourne in 2025. Bringing the design and architecture community together in a highly activated footprint, Saturday Indesign 2025 is set to ignite passion, inspiration and connection.

A better world makers

An unusual designer

TEXT JAN HENDERSON | PHOTOGRAPHY VARIOUS

The traditional craft of straw marquetry is re-interpreted for today with astounding results – and finding young followers on the journey.

LEFT

ABOVE

Arthur Seigneur is an unusual designer by anyone’s standards. He reinterprets the traditional making of straw marquetry in a contemporary style, and the results are singular objects of beauty. Born and raised in Paris, France, Seigneur’s pathway to product design and his particular focus of straw marquetry, came by a circuitous route.

At an early age he was fascinated by his father’s artistic prowess as an engraver but also energised by his love of music. In fact, at once stage, he wanted to become a musician but was persuaded by his parents to apply himself to a more stable career.

Next to becoming a musician, the best idea was to become a musical instrument maker and so Seigneur commenced study. After four years of an Ébénisterie or cabinetmaking course, he gained employment at a workshop retouching harpsichords, restoring marquetry on furniture and creating bespoke furniture pieces.

It was here that the designer realised he had found his career path, not in making furniture per se but in the intricacies of marquetry – a traditional 17th century French style of decorating furniture using inlays of wood veneers of different colours.

With a trade and experience under his belt, he and his Australian partner travelled to see the world, living and working in London and finally

arriving in New Orleans, USA. Here he found work through his expertise in wood veneer but when, by chance, he was introduced to straw marquetry, Seigneur knew he had found his true professional calling. Returning to France, Seigneur furthered his knowledge of straw marquetry at the renowned workshops of Lison de Caunes, which became the genesis for the future and his next global adventure.

In 2015 Seigneur and his partner arrived in Australia. With no contacts or friends, a serendipitous meeting with industrial designer of note, Adam Goodrum, changed everything. The pair recognised their design synergy and began creating together. In 2018 they founded their studio, A&A, collaborating and creating unique collectable objects that celebrate the delicacy and elegance of straw marquetry.

While Seigneur is certainly a remarkable craftsman, he is one of a small group of global artisans working today. He has learnt ‘on the job’, honing his craft, extending his knowledge and attempting more difficult interpretations for each project. Together Goodrum and Seigneur have forged a new style of object making that has received multiple accolades and awards.

While straw marquetry is uncommon, it is also a time-consuming process and intricate in its detail. It can take a seasoned maker seven or eight hours to split open 500 grams of material, as each straw is cut by hand, and this is all before making begins. However, it is interesting to know that the process of straw marquetry has been introduced to Australian schoolchildren and the future for the craft is finding new followers.

The connection with Australian school children began while Seigneur was presenting his work at a gallery. He was astounded to hear a six-year-old boy say that he knew of straw marquetry. Investigating, it was revealed that the child’s teacher had introduced the craft to her young students.

This provided food for thought, and speaking with the teacher at Princes Hill school, there was the opportunity for the maker to address the children and discuss their work. While this school is in Noth Carlton, Victoria another in Perth has also introduced straw marquetry and making to its students.

What was old is new again, and straw marquetry is enjoying a resurgence through the work of A&A and Australian school children. The profession is particular, the end result breathtaking and it is heartening to see that a traditional craft has found a re-energised life with followers for the future.

A&A | adamandarthur.com

Adam Goodrum and Arthur Seigneur together as A&A with cabinet from the Exquisite Corpse Collection

Photo Victoria Zschommler.

A&A Archant, console.

Photo Josh Purnel.

The tinkering mind: Isamu Noguchi

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY LIVING EDGE AND VITRA

“I love the way the lamps arrive flat packed and are just so absolutely perfect in form and light and the way they hold the space,” says Guest Editor Adam Goodrum of the Akari lamps designed by Isamu Noguchi from 1945 onwards.

In 1968 artist and designer Noguchi wrote: “Concepts appear and disappear. How easy it is to lose track of them in the myriad relationships, of depth to shallowness, of volume to plane, of density to clarity, small to large, palpable life to something dead.” He was writing about his stone sculpture Time Thinking, but the philosophy underpins all his work from the quintessential Noguchi Coffee Table to the breathtaking bubbles of sculptural light known as the Akari.

For Noguchi, “Everything is sculpture. Any material, any idea without hindrance born into space, I consider sculpture”. As such, all lines between art, architecture, design and landscape are blurred into the simple pronouncement of art. Granted, he trained as a sculptor under Gutzon Borglum, the artists who conceived and created Mount Rushmore, but the act of making art was without the contextual tethers of the day. Rather, Noguchi was inclined to work across all realms with form answering function only when it needed, and the result pleased him. There is an awareness to his work as “a vital force in our everyday life … as something which teaches human beings how to become more human” that is underpinned by his own social, environmental and spiritual consciousness.

“I think art is too much in the hands of the so-called tastemakers, dealers, critics and so forth you see, who have a prior lien on the product, whereas I like to think that art may be something that everyone should be able to enjoy and have access to. And, the Akari lamp was partly motivated by wanting to be able to have my art in everybody’s home,” Noguchi says in a video produced by Barbican Centre.

Working in a kind of tinkering method with scraps of wood, clay and paper which he arranged and let ideas formulate, he says: “Through the process of making you can find out how to do something and do it, or do something, and then find out what you did. You see, I seem to be of the second disposition. I just do it, and then maybe I’ll try to name it or find out what I did. You know, one generally starts out with pencil and paper, and one fishes around for ideas. One has an idea, perhaps, and one tries to give it a form. And then another way is to mess around with the pieces of clay and pieces of paper, pieces of wood, you know, and in that way, you get to sort of formalise an idea.”

TOP

Large Akari floor lamp. Akari black collection.

BOTTOM

Sculptural groupings of Akari lamps introduce a new dynamic

Martyn Thompson: Super Star

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY MARTYN THOMPSON

Extraordinarily multifarious, Martyn Thompson’s practice is an everevolving extravaganza of creativity.

Starting in fashion Martyn Thompson slipped into fashion photography before shifting first to lifestyle photography, then to personal photography and textile design, which remains an ongoing passion. “At some point, about eighteen years ago, I started moving more towards a personal photography practice. And that led back into a sort of design practice, which was mainly working with textile, Jacquard textile, which I work with still,” says Thompson.

In turn, his fabric designs led to ceramics, “Someone asked me, ‘Would you like to do what you do with the textiles? Would you like to make some ceramics with us?’ And I said ‘yes’, and that was 1882 Ltd in England. It’s been a very organic process for me,” says Thompson, whose collection for 1882 Ltd won Best Tableware 2020 from Elle Decoration UK.

Heading overseas was the right choice for Thompson who for the past 30 years has continued to paint, design interiors and collaborate with major designers, including a long relationship with Ilse Crawford. Moreover, he has developed the visual messaging of leading global brands such as Hermés, Jo Malone and Ralph Lauren, while also writing two books –Interiors and Working Space: An Insight into the Creative Heart.

Living in Paris, London and New York for much of his career, the move back to Sydney from New York just before the pandemic was pivotal. Selling up in America and embracing the Sydney

lifestyle, the change of location prompted yet another shift, this time to the world of glasswork.

Exhibiting at the Melbourne Design Fair in 2022 with Studio ALM, Thompson found himself between Canberra Glass Works and ceramics studio R L Foote Design Studio. “I chatted with both those people, and organised to start producing work with them,” says Thompson of the serendipity of the right people, right time.

Thompson’s method is creative with his paintings being realised as jacquard textiles by American weavers. Likewise both his ceramics and glass works are designed by him, but made by others. “My process with ceramic is to design a shape. I either have that shape, slip cast, handbuilt, or mould-built, which is not a process I personally do and then I decorate it and have it fired. With the glass, I’m even more hands-off. I again design, pick the colours, the patterns. I have my vision, and I work with Tom Rowney, who is an incredible glass blower,” says Thompson of the highly regarded glass artists and technical manager at Canberra Glassworks.

“I love being in a factory. Whenever we make glass, I’m always present, I love the process. It’s magical to watch. I just get to say things like, ‘That’s fantastic, stop now.’ I just get to be really excited, which is wonderful,” he says.

Martyn Thompson Studio | martynthompsonstudio.com

LEFT

Martyn Thompson in his Melbourne studio with large ceramic vessels and art work.

A force of nature –Olive Gill-Hille

Sumptuously tactile and of the body, the work of Perth-born multidisciplinary artist and designer, Olive Gill-Hille speaks to her interests in sculpture and furniture in equal measure.

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY OF THE ARTISTS AND GALLERY SALLY DAN-CUTHBERT

ABOVE

Olive Gill-Hille, Figures, side tables

Having relocated to Melbourne to complete a Bachelor of Fine Art specialising in sculpture at the Victorian College of the Arts, Gill-Hille became interested in the utilitarian element of furniture and began an ongoing experimentation with melding abstract and artistic concepts with practical objects. “To truly activate a space, furniture obviously has to be just as considered as any artwork. There’s such a relationship between art and furniture, I found it very easy to combine the two. Having these furniture pieces that are a type of artwork, really create value in a space, they make it more dynamic and more interesting. Furniture is something we live with every single day. So why wouldn’t we try and make it as special as we can?” Gill-Hille muses.

To enable her vision Gill-Hille undertook the Associate Degree of Furniture Design at RMIT, where she further developed her ability to transform timber, a traditionally static material, into involved and unconventional works of art. Working with ethically sourced West Australian hardwoods as well as imported timbers with proof of a low carbon footprint, each piece is considered from inception forward.

“I try to work as ethically as possible. There are times where I also use imported timbers, depending on what the exact shape and the exact purpose of the work is, or the idea behind it. At the moment, I’m working in Western Sheoak, which is a really beautiful timber. It has a very fine network of cells, and the grain is quite unique. I love working with it, it polishes up to such a beautiful, rich, consistent finish – gorgeous.”

Often referencing the human body, bodies supporting bodies, or adapting shapes and forms from the natural environment into manmade works, Gill-Hille has developed a narrative

surrounding the artworks. These stories extrapolate the material’s history, and the artist’s working environment as key aspects of her practice.

“There is a lot of consideration towards the body, the fact that the artworks are made with my body, usually through hectic, laborious work for weeks and months on end. They’re made by the body. And there is this sort of bodily element to the shapes that I do. There is a lot of referencing the human body. There’s also reflecting on my own body. I’ve often said that some of the pieces are almost like a form of self-portraiture: there’ll be little nooks or curves that I know are actually part of my own physique, a sort of mirror.”

Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert presented GillHille’s first solo exhibition Trunk in 2021. “There is a strength required in wrangling wood and using the requisite machinery and equipment that brings the artist’s own physical structure into acute focus. They are, as such, not only objects unto which the viewer might project, but extensions of the artist in the first instance; they embody her physical and emotional self,” says Gallery Director Sally Dan-Cuthbert.

Gill-Hille has been included in exhibitions at the NGV Design Fair (2022/2023), Sydney Contemporary (2022), New Australian Design at the Powerhouse, Melbourne Design Fair (2023). Her work is found in important private collections both in Australia and internationally, and a museum collection in the USA.

Gallery Sally Dan-Cuthbert | gallerysallydancuthbert.com

Olive Gill-Hille | olivegillhille.com

LEFT

Olive Gill-Hille in her studio working on Bones

Taking a stand –Alfred Lowe

As an Arrernte person from Akngwirrweltye (Snake Well) just north of Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in the central desert, Alfred Lowe’s keen interest in politics and racial justice is fuelled by Central Australia being a politically and racially charged region.

For artist and advocate Alfred Lowe, the way culture and identity are navigated and manifested in modern times underwrites the themes explored in his astounding sculptural work.

Using ceramics to explore themes of Country, Lowe investigates form and texture as a medium that responds to, and is informed by, his intimate knowledge of the central desert landscape. Hand-building the forms to create organic vessels, Lowe applies underglazes and a range of mark-making to the surface as well as fibre, often in extraordinarily vivid hues.

Having grown up in Mparntwe (Alice Springs), his interest in fine arts is heavily influenced and inspired by his upbringing with his neighbour. Clifford Possum in particular, is of paramount importance to the young artist. Lowe recalls standing on truck tyres to peer over the fence and watch Clifford paint for hours at a time. The influence of the community has similar strengths with Araluen Arts and Cultural Precinct just across the road, a place where Lowe spent a significant amount of time in his youth.

The recent winner of the MA Art Prize at Sydney Contemporary, his career has all the appearances of being on a sharp trajectory. That said, it should also be noted that Lowe has a quiet certainty to his work and continues to practice daily at the APY Studio in Tartanya (Adelaide). Moreover, and importantly, as an early career artist he is still examining how the influences and experiences of politics and culture are reflected in his artistic practice and will continue to develop his concerns as his work evolves.

Lowe has been a finalist in the 2023 Ramsay Art Prize exhibition, Art Gallery of South Australia, and in 2022 was a finalist in both the Shepparton Art Museum Ceramics Award & NATSIAA Awards. His work has been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Shepparton Art Museum and the Art Gallery of Ballarat, Victoria.

Sabbia Gallery | sabbiagallery.com

APY Studio | apygallery.com

LEFT

Alfred Lowe at Sabbia Gallery with his work, All Dressed Up

ABOVE

Installation view Alfred Lowe exhibition, The Gathering, Sabbia Gallery.

DIY doesn’t mean doing it alone

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER | PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY ISHINOMAKI LABORATORY

Making news the world over, the great earthquake and tsunami that hit southeast Japan in March of 2011 was the single most devastating event of Japan’s recent history with thousands of homes lost. Ishinomaki Laboratory was established in one of the coastal towns most affected by disaster, with the goal of creating simple furniture to help rebuild the community.

LEFT

ABOVE

Maker Pack Carry Stool in collaboration with Karimoku Furniture.

Led by Tokyo-based architect Keiji Ashizawa (the architect of Trunk, the hippest hotel in Tokyo) and former sushi chef (and Ishinomaki local) Takahiro Chiba, Ishinomaki Laboratory began as a common utility space ‘for the people’ where residents in the disaster area could freely access materials and tools – as provided by designers and volunteers – to conduct their own repair work. Donated Canadian red cedar was the crucial material at this early stage.

DIY workshops were the primary vehicle for residents affected by the disaster with simple designs being freely shared to make furniture-making as easy as possible.

“Utilitarian forms, functionality and durability merge with simple design. Our products have been created for ordinary people and everyday lives,” says Ashizawa.

During the crisis Ishinomaki Laboratory started restoring local shops and the appeal of artisanal craftsmanship started to resonate more profoundly with the group. This, in turn, led to the establishment of the Ishinomaki Laboratory label with the idea of marketing the DIY products beyond the local community.

“We didn’t start Ishinomaki Laboratory with a business strategy, branding, or marketing in mind, and in the last ten years, we’ve learned that ‘doing it yourself’ doesn’t mean doing it alone. As our project grows, so does our global community – and our furniture has come to symbolise so much more than great design,” says Ashizawa, who has tapped into a long tradition of Japanese woodworking to offer high-quality, modern furniture that is entirely maker made.

The laboratory is a shifting entity by nature and at present the group comprises a collection of young and talented designers from Japan and abroad who contribute to the planning and products behind the brand. This is realised through six staff members who work under the supervision of Chiba.

As the world’s first DIY label, expanding the world of DIY and its potential through the power of design is a driving force. As such, workshops continue to be a mainstay of the practice with DIY events in Japan and internationally, an ongoing part of the label’s commitment to providing a sustainable resource. Likewise, collaboration is a key element with partnerships fostered the world over. The collaboration with Karimoku Furniture, for example, has a great simpatico of ethos. “Through the spirit of making, we at Karimoku Furniture aim to restore the resilience of forests, which are a vital natural resource, and enhance the sustainability of the forestry industry responsible for the management of forests,” says Hiroshi Kato, Vice President of Karimoku Furniture.

Adapting the clean designs of Ishinomaki Laboratory’s furniture, Karimoku’s highly evolved manufacturing techniques and networks of resources has resulted in the Maker Pack line. Easily shipped around the world, the Maker Pack collection is based on the concept of Maker Made and continues the original idea of aesthetic furniture that is simple, yet functional and attractive, but also delivers the DIY spirit that remains at the core of Ishinomaki Laboratory.

Ishinomaki Laboratory | ishinomaki-lab.org

Maker Pack Kobo Table and Kobo Bench in collaboration with Karimoku Furniture.

Tokyo drift –Alexander Calder

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY TADAYUKI MINAMOTO © 2024 CALDER FOUNDATION NEW YORK / ARS NEW YORK

With 35 years between exhibitions in Tokyo –Alexander Calder still holds the attention and hearts of the art world.

ALEFT

Alexander Calder with Red Disc and Gong (1940) and Untitled (c. 1940) in his Roxbury studio, 1944. © 2024 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

ABOVE

Installation view of Calder: Un effet du japonais, Azabudai Hills Gallery, 2024. Photo: Tadayuki Minamoto, © 2024 Calder Foundation New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

s the story goes, according to Calder biographer, Jed Perl, in 1949, six years after his extraordinary retrospective at MoMA, Calder was commissioned to create a mobile for Dorothy Miller, an important curator at the Modern. Expecting a delivered artwork, she was more than a little surprised when Calder appeared at her Greenwich Village apartment with his pliers and a suitcase full of wires and various biomorphic shapes. As she tells it, Calder had gotten up on a stepladder and begun, on the spot, to fashion the mobile that hung for decades from an old chandelier mount.

This is just one of the stories around Calder, who also upgraded his 1943 MoMA Catalogue by offering to donate a horse sculpture, “Do you think we could bait that catalogue trap with horsemeat and offer them this in exchange for further expanding the catalogue[?],” Calder wrote. He was also keen for people to touch his sculptures, which flies in the face of most art exhibitions. In 1944, Mário Pedrosa, the Brazilian art critic was amazed that, “anyone could touch them, move them, sway them and even push them with their feet; in particular the large free moving mobiles,” and was “surprised” by an “overwhelming absence of taboos”.

In Japan, Calder’s work is held in particular reverence. In fact, Pace Gallery opened its

new Tokyo outpost in July 2024 with an accompanying exhibition Calder: Un Effet du Japonais at the adjacent Azabudai Hills Gallery. Comprising around one hundred works from the Calder Foundation, the exhibition explored the enduring resonance of the American modernist’s art with Japanese traditions and aesthetics.

Curated by Alexander S. C. Rower, President of the Calder Foundation, New York, and organised in collaboration with Pace Gallery, spanning the 1930s to the 1970s, the exhibition includes the artist’s signature mobiles, stabiles and standing mobiles, oil paintings and works on paper.

The alcove lined with thick sheets of blackened paper reinforced the dynamic interplay between Calder and the Japanese aesthetic and lent a contemporary edge to the exhibition. The large sculptures, however, were the primary attraction with huge mobiles including Untitled (1956), slowly rotating overhead and the stately floor pieces, such as The Pagoda (1963) and Black Beast (1940) having huge visual and physical presence.

Pace Gallery | pacegallery.com

Calder Foundation | calder.org

Suna Fujita: wit and whimsy on a chopstick rest

Suna Fujita, the Kyoto-based partners and ceramic artists, have exhibited extensively throughout Japan, China and Taiwan. They have also both continued as active ceramicists working independently, as well as together.

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY COURTESY SUNA FUJITA AND LOEWE

The dreamy utopian world of Suna Fujita plays on the quirky moments of everyday life, while providing respite from the harshness of the world. These are the thoughts behind the work of ceramic studio duo Shohei Fujita and Chisato Yamano, whose ceramic studio Suna Fujita is bringing delight and whimsy into homes all over the world.

“We are overloaded with unpleasant news in our daily lives,” Fujita says, who counters, “So I wanted the world we depict to be somewhere dreamy, almost utopian, where people can escape to.” Yamano is in accord with the memorable moments from her life (from feeding to chickens, to walking in the forest with their son and dog) fuelling her wonderfully peculiar drawings. “My drawings hide playful scenes among them, which I hope people will find and have a giggle,” she says.

The shared ethos of the artists, who have been working together since 2005 and officially became Suna Fujita in 2014, is underpinned by a love of nature and tradition. “A world where animals, nature and humans coexist as equals,” says Yamano. Moreover, it is the tradition of ceramics as a means to speak for the times in a profoundly personal way.

“I feel that familiar landscapes and sceneries are continuing to fade away. Pottery works can last for a long time. Even after being broken into pieces, the images drawn on the surface teach us the culture and ways of living at that time. I

feel pottery can be a medium to leave behind the stories of our life,” Fujita says.

The works themselves are beyond divine with children catching a ride on the fin of a giant flying fish, a benevolent octopus hosting a party, fabulous goop connected animals, shark surfboards, tea parties and the delightful joy of a whale boat puttering along. Full of humour and wit, such as an ocean of fantastical sea creatures looking into a bowl of playing children, the imagined worlds are hand-painted as miniature scenes onto ceramic plates, tea bowls, cups and chopstick rests. Touching on fantasy, memory and the wonders of the natural world, there is an abundance of happiness in every piece.

Introduced to Australia at the Melbourne Art Fair, the collaboration with Spanish fashion brand LOEWE has rocketed the duo to cult status. Shifting the images from ceramics to bags, clothing, lighting, books, animation (by Joseph Wallace) and packaging, the collectability of Suna Fujita has taken on exponential growth.

The launch in Tokyo in 2023 of their first collaboration, for example, was significant, but the latest collaboration for 2024 had lines around the block. Singapore has seen a similar attraction with the holiday collection 2024 selling out almost immediately.

LOEWE | Loewe.com

Suna Fujita |@suna_fu fita

LEFT AND ABOVE

The delightful images and ceramics of Suna Fujita.

A privilege in the making

TEXT GILLIAN SERISIER PHOTOGRAPHY VARIOUS

Growing up in Perth, Adam Goodrum feels fortunate to have been part of a culture deeply rooted in the art of making. “Everyone had a quarter-acre block, and almost everyone had a backyard shed to tinker,” he recalls. “You could always find someone to help, to build parts for a go-kart, turn an axle on a metal lathe, or laminate some ply to make a sandboard.”

Goodrum fondly remembers Todd Taylor’s dad, Mr. Taylor. “If we needed something turned on a lathe, we’d go to my friend’s father. And if it was something really intricate, we’d go to his father, a fitter and turner with a number of metal lathes in his back shed. He was incredibly skilled and always had a solution.”

This hands-on culture was perfectly aligned with Goodrum’s design sensibilities, further inspired by his mother’s hand-spinning at home. “The spinning wheel was such an honest object,” he reflects. “Its analogue nature was beautifully transparent in how it worked. The mechanics were so thoughtfully designed, with timber construction and lovely forms. And then there was the rhythmic sound it made –absolutely mesmerising.”

With craft and engineering and makers around him, Goodrum was a designer from the get go, plotting his projects as drawings before starting on a task. “I was one of those kids who was always drawing and loved Lego. I used to do drawings of what we were going to make. So, if we were going to make a cubby house or a go-kart or something, I’d do drawings beforehand.”

One of his first designs, complete with drawings, was for a surfboard leg rope, which were expensive to buy. “The plug in my design was a Coca Cola lid with a nail through it that was Araldited into the foamy board. The leg rope was part of mum’s clothesline, and one of her pantyhose was turned back on itself to make a donut that you could slip over your foot, it worked a treat,” says Goodrum, who still surfs.

Goodrum now designs furniture of exceptional quality for two icons of Australian design: Tait and NAU.

For Tait, his work focuses on outdoor pieces that embody a distinctly Australian aesthetic, marked by clean, linear detailing and a touch of playful charm. “Tait has developed its own unique language,” says Goodrum. “It’s robust, approachable and occasionally sprinkled with a bit of whimsy.”

He particularly values Tait’s manufacturing expertise, led by Gordon Tait, who brings a

deep understanding of metal fabrication to the process. “Working so closely with the client is incredibly rewarding,” Goodrum shares. “Visiting the Melbourne factory, working with the team on the floor, and collaborating with Gordon, who has such an incredible depth of metal knowledge is such a pleasure.” One standout feature of this collaboration is access to cutting-edge tools. “Right now, I’m loving the 3D tube bender – it’s a phenomenal piece of equipment. I’m pretty sure it’s the only one of its kind in Australia, and possibly in the AsiaPacific region,” Goodrum adds.

Early in his career, Goodrum created all his own prototypes. This has now shifted to others with NAU’s production, but the elation remains. “I feel incredibly privileged to work with such amazing makers,” Goodrum shares. “There’s nothing more exciting than visiting a factory to see a prototype for a new project, whether it’s an upholstered sofa or a timber chair.”

For NAU, the focus is on indoor furniture that doesn’t aim to compete with European brands but matches them in aesthetics and quality. What sets NAU apart is its emphasis on bespoke production rather than mass manufacturing, informing in a refined yet effortless design language. The timber pieces are crafted from solid wood, showcasing a strong handmade quality, while the upholstery patterns are cut by hand, reflecting the meticulous attention to detail.

“There’s an aesthetic in my NAU work that nods to European design while maintaining its own unique identity,” Goodrum explains. “That individuality is important – it allows interior designers to curate across brands for a cohesive result that feels authentically Australian without falling into cliché.”

Goodrum also highlights the collaboration with NAU’s founder, Richard Munao, as a key factor in the brand’s success. “It’s such a pleasure to work with someone with Richard’s expertise and vision. I’m incredibly lucky in that regard,” he adds.

Adam Goodrum | adamgoodrum.com

LEFT

Fat Tulip Sofa for NAU. ABOVE

Adam Goodrum in the Tait showroom.

Photo Timothy Kaye. Swing Chair for Tait. Photo Haydn Cattach.

Outside the box portrait #75

A collector in flux

Chippendale is a small pocket of a suburb adjacent to the Sydney city centre. Historically an industrial area with workers cottages and some of the poorest and most substandard housing in the city, over the last decade it has transformed into a vibrant cultural precinct. By 2024 Time Out named it the coolest neighbourhood in Australia (which also ranked it 7th in the world).

TEXT DAVID CLARK |

Activated by the development of Central Park on the old Carlton United Brewery (CUB) site opposite UTS, it has also become one of the richest architectural quarters of the city with a collection of buildings by excellent international and Australian architects.

A significant player in the transformation of the area is collector, philanthropist and patron, Judith Neilson.

White Rabbit Gallery came first, opened with her former husband Kerr Neilson in the heart of Chippendale in 2009. A significant survey collection of Chinese contemporary art, the gallery had an immediate impact on the Australian and international art scene. It was a prescient move for the Neilsons. Construction on the award-winning development of the nearby CUB site would not start until the year later. They were early players.

Neilson is a pragmatically elegant woman born in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) in 1946. She studied graphic design at art school in Natal, South Africa. In 1983 she came to Australia with Kerr. Initially, she worked at Grace Brothers designing catalogues, until her children (two daughters) were born. In the meantime, Kerr Neilson was building an asset management consultancy that, when it went public in 2007, made the Neilsons a fortune and made them philanthropists.

When she divorced her husband in 2015, Neilson had the financial independence and ability to devote her life to her own philanthropic and aesthetic pursuits. She funded the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas. She endowed a Chair of Architecture at the UNSW to focus on housing solutions for refugees. And she became a prominent patron of art, architecture and design.

Around the corner from White Rabbit Gallery, are three buildings commissioned by Neilson that, while private, contribute much to the streetscape. They are a necessary stop for any architectural tourist surveying the area.

PREVIOUS LEFT

Judith Neilson.

PREVIOUS RIGHT

Indigo

ABOVE

Inside Indigo Slam, design and artworks, including a credenza by Adam & Arthur, sit perfectly within their natural habitat.

Slam, Neilson’s private home by Smart Design Studio.

Along with other more personal pieces collected over a lifetime, the interior has become more layered and more eclectic than it might otherwise have been.

OPPOSITE

The upper balcony of Indigo Slam by Smart Design Studio is as much artwork as architecture.

ABOVE TOP

Pairing expansive settings and nooks within the same space, each room in Indigo Slam is designed to be lived in.

ABOVE BOTTOM

Dangrove, by Tzannes, currently houses Neilson’s significant collection of Chinese art.

Indigo Slam, with its machine-like sculptural façade, was designed by William Smart, who also remodelled the old warehouse that became White Rabbit Gallery. It is Neilson’s home for much of the year. The rest she spends in her private apartment on the vessel The World, cruising the high seas. Beside it is Phoenix, really a pair of buildings unified by the texture of long and shallow handmade bricks. It houses a private gallery by John Wardle that primarily holds her collections of African Art. Beside it, separated by a private courtyard, is a semi-private performance space designed by Neil Durbach.

A suburb away in Alexandria is Dangrove, Neilson’s spectacular, state-of-the-art storage facility designed by Alex Tzannes. “I never sell a thing,” says Neilson. “I have more than 800 artists, more than 4,000 artworks. So, I needed Dangrove.” The collection is in constant flux, moving between buildings as required.

As an art collector, Neilson likes a ‘pure collection’. White Rabbit Gallery, for instance, is only Chinese contemporary art post 2000. Nothing prior. Phoenix is currently devoted to African art collections. At other times it will be Australian Indigenous art.

When she commissioned Indigo Slam to Smart, she also commissioned Adelaide-based Khai Liew to design every piece of furniture for the interior – more than 160 pieces. For a designer like Liew, who died in 2024 and was surely one of Australia’s best, it was the brief of a lifetime.

Filling a house entirely with furniture from one designer is a bold act of patronage. But it doesn’t easily make a home. Rather, such an interior can feel more gallery-like. The owner’s own aesthetic expressions of domesticity are minimised. Over time, Neilson retired some of Liew’s pieces to Dangrove and replaced them with work by Adam Goodrum (guest editor of this issue), or by Goodrum with his collaborator Arthur Seigneur. Only these Australian designers are represented (currently), and Liew’s and Goodrum’s designs play beautifully off each other.

She says that from the moment she saw Goodrum’s work, she was “right there”. She commissioned a conference table for her offices nearby Indigo Slam. Then she began to buy, for the house, but also for her collection.

The first major piece was a large dining table on the first living level of the house. The entry level has a spectacularly long dining setting by Liew for monumental dinners. The other is of a more intimate scale, but still seats 16 at minimum and is 2.8 metres square. It needed to be carried upstairs in four parts by a team of movers and connected onsite. The square configuration was a

stipulation by Neilson to create a more convivial seating arrangement and to avoid not being able to connect with people at the other end of a long rectangular shape.

Other pieces followed – a mirror and storage cabinet for the private bedroom; stools covered in alligator skin from a friend’s farm in Africa; long credenzas for storage.

Some years ago, Goodrum started a collaboration with Arthur Seigneur, a French craftsman trained in the art of straw marquetry. As Adam + Arthur, their formal, kinetic, and wildly patterned straw marquetry pieces have become global collectors’ items. Neilson bought several pieces (from Tolarno Gallery), some for the house and some for the collection at Dangrove. Another piece is commissioned to sit beside Liew’s table downstairs.

These colourful, sculptural pieces add ‘oomph’ to an otherwise tonal interior. Along with other more personal pieces collected over a lifetime, the interior has become more layered and more eclectic than it might otherwise have been.

Goodrum says: “Judith is aesthetically driven and likes things that are ambitious. But she’s practical as well. The piece needs to work properly for her.” A drawer that is too low, for instance, is removed from a design. Apart from the functional requirements, Goodrum works with an open brief.

Like all great collectors, Neilson operates on intuition and gut feel. Her first piece of Australian design was not a chair nor a table or a light. It was a car. A Ford racing car, in fact, that had sped around racing tracks and been virtually hand built or had an artist of some sort involved in its making. “Even if that artist was an engineer,” says Neilson.

That purchase, like most, was serendipitous and instinctual. The day she was made aware of the car’s auction was her father’s birthday. Her father had been a manufacturer of car radiators. She felt it was kismet and bought the car straight away. Now it sits in Dangrove, and she says it’s the first piece that every visitor gravitates to, bypassing all the painting and sculpture.

Neilson shares she has been collecting since she was a child. Her first ‘piece’, nothing more than a child’s keepsake, was a small bell, fallen from a horse that had been pulling the flat-backed carriage she and her aunt were riding in Africa. “That bell never rusted, and brought me good luck,” she says. Now, as an act of faith in that continuing luck, perhaps, she puts a handful of small bells into every concrete pour for every new building she does.

Judith Neilson Projects | judithneilsonprojects.com.au

ABOVE TOP

ABOVE BOTTOM

Phoenix by Durbach

Block Jaggers and John Wardle Architects, includes a gallery, a central garden, and an intimate performance space.

OPPOSITE

The pool at Indigo Slam.